User login

CLEVELAND – independently of baseline left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

The finding comes from a prespecified secondary analysis of the STEP-HFpEF trial of more than 500 nondiabetic patients with obesity and HF with an initial LVEF of 45% or greater.

They suggest that for patients with the obesity phenotype of HFpEF, semaglutide (Wegovy) could potentially join SGLT2 inhibitors on the short list of meds with consistent treatment effects whether LVEF is mildly reduced, preserved, or in the normal range.

That would distinguish the drug, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, from mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), sacubitril-valsartan (Entresto), and other renin-angiotensin-system inhibitors (RASi), whose benefits tend to taper off with rising LVEF.

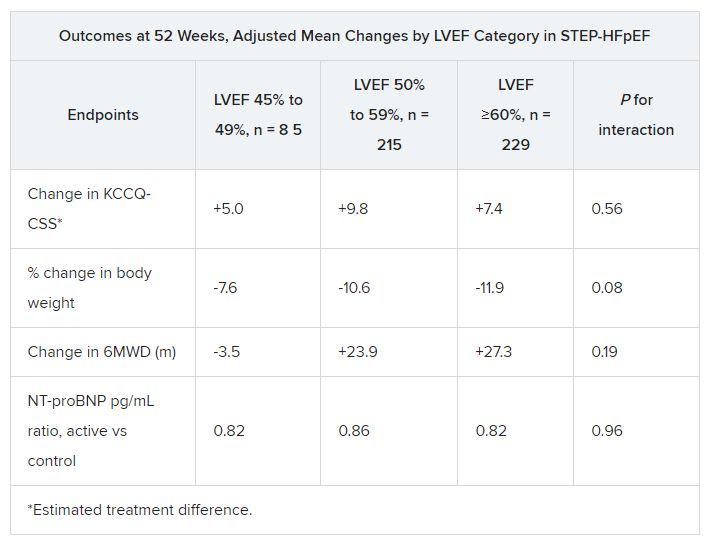

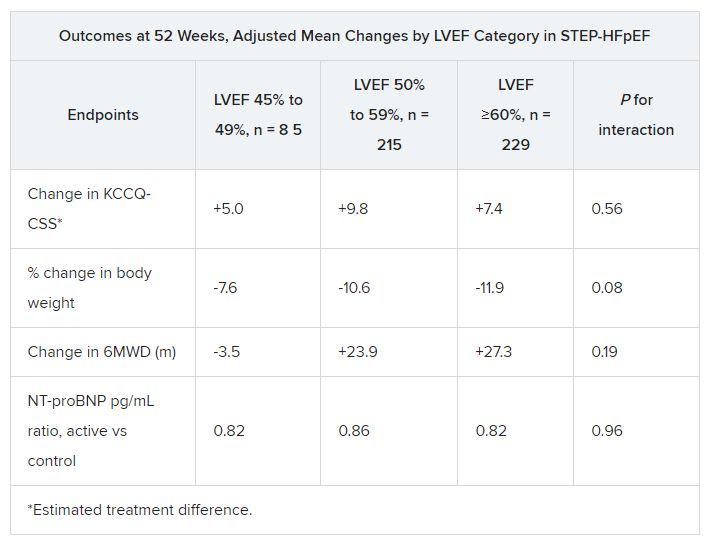

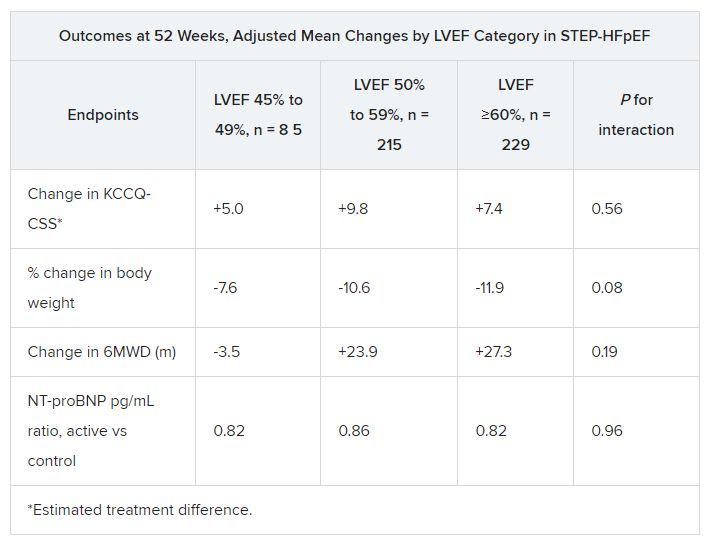

The patients assigned to semaglutide showed significant improvement in both primary endpoints – change in Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Clinical Summary Score (KCCQ-CSS) and change in body weight at 52 weeks – whether their baseline LVEF was 45%-49%, 50%-59%, or 60% or greater.

Results were similar for improvements in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and levels of NT-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and C-reactive protein, observed Javed Butler, MD, when presenting the analysis at the annual meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America, Cleveland.

Dr. Butler, of Baylor Scott and White Research Institute, Dallas, and the University of Mississippi, Jackson, is also lead author of the study, which was published on the same day in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

In his presentation, Dr. Butler singled out the NT-proBNP finding as “very meaningful” with respect to understanding potential mechanisms of the drug effects observed in the trial.

For example, people with obesity tend to have lower than average natriuretic peptide levels that “actually go up a bit” when they lose weight, he observed. But in the trial, “we saw a reduction in NT-proBNP in spite of the weight loss,” regardless of LVEF category.

John McMurray, MD, University of Glasgow, the invited discussant for Dr. Butler’s presentation, agreed that it raises the question whether weight loss was the sole semaglutide effect responsible for the improvement in heart failure status and biomarkers. The accompanying NT-proBNP reductions – when the opposite might otherwise have been expected – may point to a possible mechanism of action that is “something more than just weight loss,” he said. “If that were the case, it becomes very important, because it means that this treatment might do good things in non-obese patients or might do good things in patients with other types of heart failure.”

‘Vital reassurance’

More definitive trials are needed “to clarify safety and efficacy of obesity-targeted therapeutics in HF across the ejection fraction spectrum,” according to an accompanying editorial).

Still, the STEP-HFpEF analysis “strengthens the role of GLP-1 [receptor agonists] to ameliorate health status” for patients with obesity and HF with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction, write Muthiah Vaduganathan, MD, MPH, and John W. Ostrominski, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

Its findings “provide vital reassurance” on semaglutide safety and efficacy in HF with below-normal LVEF and “tentatively support the existence of a more general, LVEF-independent, obesity-related HF phenotype capable of favorable modification with incretin-based therapies.”

The lack of heterogeneity in treatment effects across LVEF subgroups “is not surprising,” but “the findings reinforce that the benefits of this therapy in those meeting trial criteria do not vary by left ventricular ejection fraction,” Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center, said in an interview.

It remains unknown, however, “whether the improvement in health status, functional status, and reduced inflammation” will translate to reduced risk of cardiovascular death or HF hospitalization, said Dr. Fonarow, who isn’t connected to STEP-HFpEF.

It’s a question for future studies, he agreed, whether semaglutide would confer similar benefits for patients with obesity and HF with LVEF less than 45% or in non-obese HF patients.

Dr. McMurray proposed that future GLP-1 receptor agonist heart-failure trials should include non-obese patients to determine whether the effects seen in STEP-HFpEF were due to something more than weight loss. Trials in patients with obesity and HF with reduced LVEF would also be important.

“If it turns out just to be about weight loss, then we need to think about the alternatives,” including diet, exercise, and bariatric surgery but also, potentially, weight-loss drugs other than semaglutide, he said.

No heterogeneity by LVEF

STEP-HFpEF randomly assigned 529 patients free of diabetes with an LVEF greater than or equal to 45%, a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 kg/m2, and NYHA functional status of 2-4 to either a placebo injection or 2.4-mg semaglutide subcutaneously once a week (the dose used for weight reduction) atop standard care.

As previously reported, those assigned to semaglutide showed significant improvements at 1 year in symptoms and in physical limitation, per changes in KCCQ-CSS, and weight loss, compared with the control group. Their exercise capacity, as measured by 6MWD, also improved.

The more weight patients lost while taking semaglutide, the better their KCCQ-CSS and 6MWD outcomes, a prior secondary analysis suggested. But the STEP-HFpEF researchers said weight loss did not appear to explain all of their gains, compared with usual care.

For the current analysis, the 263 patients assigned to receive semaglutide and 266 control patients were divided into three groups by baseline LVEF and compared for the same outcomes.

The semaglutide group, compared with control patients, also showed a significantly increased hierarchical composite win ratio, 1.72 (95% CI, 1.37-2.15; P < .001), that was consistent across LVEF categories and that accounted for all-cause mortality, HF events, KCCQ-CSS and 6MWD changes, and change in CRP.

Limitations make it hard to generalize the results, the authors caution. Well over 90% of the participants were White patients, for example, and the overall trial was not powered to show subgroup differences.

Given the many patients with HFpEF who have a cardiometabolic phenotype and are with overweight or obesity, write Dr. Butler and colleagues, their treatment approach “may ultimately include combination therapy with SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists, given their non-overlapping and complementary mechanisms of action.”

Dr. Fonarow noted that both MRAs and sacubitril-valsartan offer clinical benefits for patients with HF and LVEF “in the 41%-60% range” that are evident “across BMI categories.”

So it’s likely, he said, that those medications as well as SGLT2 inhibitors will be used along with GLP-1 receptor agonists for patients with HFpEF and obesity.

STEP-HFpEF was funded by Novo Nordisk. Dr. Butler and the other authors disclose consulting for many companies, a list of which can be found in the report. Dr. Fonarow reports consulting for multiple companies. Dr. McMurray discloses consulting for AstraZeneca. Dr. Ostrominski reports no relevant disclosures. Dr. Vaduganathan discloses receiving grant support, serving on advisory boards, or speaking for multiple companies and serving on committees for studies sponsored by AstraZeneca, Galmed, Novartis, Bayer AG, Occlutech, and Impulse Dynamics.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

CLEVELAND – independently of baseline left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

The finding comes from a prespecified secondary analysis of the STEP-HFpEF trial of more than 500 nondiabetic patients with obesity and HF with an initial LVEF of 45% or greater.

They suggest that for patients with the obesity phenotype of HFpEF, semaglutide (Wegovy) could potentially join SGLT2 inhibitors on the short list of meds with consistent treatment effects whether LVEF is mildly reduced, preserved, or in the normal range.

That would distinguish the drug, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, from mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), sacubitril-valsartan (Entresto), and other renin-angiotensin-system inhibitors (RASi), whose benefits tend to taper off with rising LVEF.

The patients assigned to semaglutide showed significant improvement in both primary endpoints – change in Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Clinical Summary Score (KCCQ-CSS) and change in body weight at 52 weeks – whether their baseline LVEF was 45%-49%, 50%-59%, or 60% or greater.

Results were similar for improvements in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and levels of NT-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and C-reactive protein, observed Javed Butler, MD, when presenting the analysis at the annual meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America, Cleveland.

Dr. Butler, of Baylor Scott and White Research Institute, Dallas, and the University of Mississippi, Jackson, is also lead author of the study, which was published on the same day in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

In his presentation, Dr. Butler singled out the NT-proBNP finding as “very meaningful” with respect to understanding potential mechanisms of the drug effects observed in the trial.

For example, people with obesity tend to have lower than average natriuretic peptide levels that “actually go up a bit” when they lose weight, he observed. But in the trial, “we saw a reduction in NT-proBNP in spite of the weight loss,” regardless of LVEF category.

John McMurray, MD, University of Glasgow, the invited discussant for Dr. Butler’s presentation, agreed that it raises the question whether weight loss was the sole semaglutide effect responsible for the improvement in heart failure status and biomarkers. The accompanying NT-proBNP reductions – when the opposite might otherwise have been expected – may point to a possible mechanism of action that is “something more than just weight loss,” he said. “If that were the case, it becomes very important, because it means that this treatment might do good things in non-obese patients or might do good things in patients with other types of heart failure.”

‘Vital reassurance’

More definitive trials are needed “to clarify safety and efficacy of obesity-targeted therapeutics in HF across the ejection fraction spectrum,” according to an accompanying editorial).

Still, the STEP-HFpEF analysis “strengthens the role of GLP-1 [receptor agonists] to ameliorate health status” for patients with obesity and HF with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction, write Muthiah Vaduganathan, MD, MPH, and John W. Ostrominski, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

Its findings “provide vital reassurance” on semaglutide safety and efficacy in HF with below-normal LVEF and “tentatively support the existence of a more general, LVEF-independent, obesity-related HF phenotype capable of favorable modification with incretin-based therapies.”

The lack of heterogeneity in treatment effects across LVEF subgroups “is not surprising,” but “the findings reinforce that the benefits of this therapy in those meeting trial criteria do not vary by left ventricular ejection fraction,” Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center, said in an interview.

It remains unknown, however, “whether the improvement in health status, functional status, and reduced inflammation” will translate to reduced risk of cardiovascular death or HF hospitalization, said Dr. Fonarow, who isn’t connected to STEP-HFpEF.

It’s a question for future studies, he agreed, whether semaglutide would confer similar benefits for patients with obesity and HF with LVEF less than 45% or in non-obese HF patients.

Dr. McMurray proposed that future GLP-1 receptor agonist heart-failure trials should include non-obese patients to determine whether the effects seen in STEP-HFpEF were due to something more than weight loss. Trials in patients with obesity and HF with reduced LVEF would also be important.

“If it turns out just to be about weight loss, then we need to think about the alternatives,” including diet, exercise, and bariatric surgery but also, potentially, weight-loss drugs other than semaglutide, he said.

No heterogeneity by LVEF

STEP-HFpEF randomly assigned 529 patients free of diabetes with an LVEF greater than or equal to 45%, a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 kg/m2, and NYHA functional status of 2-4 to either a placebo injection or 2.4-mg semaglutide subcutaneously once a week (the dose used for weight reduction) atop standard care.

As previously reported, those assigned to semaglutide showed significant improvements at 1 year in symptoms and in physical limitation, per changes in KCCQ-CSS, and weight loss, compared with the control group. Their exercise capacity, as measured by 6MWD, also improved.

The more weight patients lost while taking semaglutide, the better their KCCQ-CSS and 6MWD outcomes, a prior secondary analysis suggested. But the STEP-HFpEF researchers said weight loss did not appear to explain all of their gains, compared with usual care.

For the current analysis, the 263 patients assigned to receive semaglutide and 266 control patients were divided into three groups by baseline LVEF and compared for the same outcomes.

The semaglutide group, compared with control patients, also showed a significantly increased hierarchical composite win ratio, 1.72 (95% CI, 1.37-2.15; P < .001), that was consistent across LVEF categories and that accounted for all-cause mortality, HF events, KCCQ-CSS and 6MWD changes, and change in CRP.

Limitations make it hard to generalize the results, the authors caution. Well over 90% of the participants were White patients, for example, and the overall trial was not powered to show subgroup differences.

Given the many patients with HFpEF who have a cardiometabolic phenotype and are with overweight or obesity, write Dr. Butler and colleagues, their treatment approach “may ultimately include combination therapy with SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists, given their non-overlapping and complementary mechanisms of action.”

Dr. Fonarow noted that both MRAs and sacubitril-valsartan offer clinical benefits for patients with HF and LVEF “in the 41%-60% range” that are evident “across BMI categories.”

So it’s likely, he said, that those medications as well as SGLT2 inhibitors will be used along with GLP-1 receptor agonists for patients with HFpEF and obesity.

STEP-HFpEF was funded by Novo Nordisk. Dr. Butler and the other authors disclose consulting for many companies, a list of which can be found in the report. Dr. Fonarow reports consulting for multiple companies. Dr. McMurray discloses consulting for AstraZeneca. Dr. Ostrominski reports no relevant disclosures. Dr. Vaduganathan discloses receiving grant support, serving on advisory boards, or speaking for multiple companies and serving on committees for studies sponsored by AstraZeneca, Galmed, Novartis, Bayer AG, Occlutech, and Impulse Dynamics.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

CLEVELAND – independently of baseline left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

The finding comes from a prespecified secondary analysis of the STEP-HFpEF trial of more than 500 nondiabetic patients with obesity and HF with an initial LVEF of 45% or greater.

They suggest that for patients with the obesity phenotype of HFpEF, semaglutide (Wegovy) could potentially join SGLT2 inhibitors on the short list of meds with consistent treatment effects whether LVEF is mildly reduced, preserved, or in the normal range.

That would distinguish the drug, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, from mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), sacubitril-valsartan (Entresto), and other renin-angiotensin-system inhibitors (RASi), whose benefits tend to taper off with rising LVEF.

The patients assigned to semaglutide showed significant improvement in both primary endpoints – change in Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Clinical Summary Score (KCCQ-CSS) and change in body weight at 52 weeks – whether their baseline LVEF was 45%-49%, 50%-59%, or 60% or greater.

Results were similar for improvements in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and levels of NT-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and C-reactive protein, observed Javed Butler, MD, when presenting the analysis at the annual meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America, Cleveland.

Dr. Butler, of Baylor Scott and White Research Institute, Dallas, and the University of Mississippi, Jackson, is also lead author of the study, which was published on the same day in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

In his presentation, Dr. Butler singled out the NT-proBNP finding as “very meaningful” with respect to understanding potential mechanisms of the drug effects observed in the trial.

For example, people with obesity tend to have lower than average natriuretic peptide levels that “actually go up a bit” when they lose weight, he observed. But in the trial, “we saw a reduction in NT-proBNP in spite of the weight loss,” regardless of LVEF category.

John McMurray, MD, University of Glasgow, the invited discussant for Dr. Butler’s presentation, agreed that it raises the question whether weight loss was the sole semaglutide effect responsible for the improvement in heart failure status and biomarkers. The accompanying NT-proBNP reductions – when the opposite might otherwise have been expected – may point to a possible mechanism of action that is “something more than just weight loss,” he said. “If that were the case, it becomes very important, because it means that this treatment might do good things in non-obese patients or might do good things in patients with other types of heart failure.”

‘Vital reassurance’

More definitive trials are needed “to clarify safety and efficacy of obesity-targeted therapeutics in HF across the ejection fraction spectrum,” according to an accompanying editorial).

Still, the STEP-HFpEF analysis “strengthens the role of GLP-1 [receptor agonists] to ameliorate health status” for patients with obesity and HF with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction, write Muthiah Vaduganathan, MD, MPH, and John W. Ostrominski, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

Its findings “provide vital reassurance” on semaglutide safety and efficacy in HF with below-normal LVEF and “tentatively support the existence of a more general, LVEF-independent, obesity-related HF phenotype capable of favorable modification with incretin-based therapies.”

The lack of heterogeneity in treatment effects across LVEF subgroups “is not surprising,” but “the findings reinforce that the benefits of this therapy in those meeting trial criteria do not vary by left ventricular ejection fraction,” Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center, said in an interview.

It remains unknown, however, “whether the improvement in health status, functional status, and reduced inflammation” will translate to reduced risk of cardiovascular death or HF hospitalization, said Dr. Fonarow, who isn’t connected to STEP-HFpEF.

It’s a question for future studies, he agreed, whether semaglutide would confer similar benefits for patients with obesity and HF with LVEF less than 45% or in non-obese HF patients.

Dr. McMurray proposed that future GLP-1 receptor agonist heart-failure trials should include non-obese patients to determine whether the effects seen in STEP-HFpEF were due to something more than weight loss. Trials in patients with obesity and HF with reduced LVEF would also be important.

“If it turns out just to be about weight loss, then we need to think about the alternatives,” including diet, exercise, and bariatric surgery but also, potentially, weight-loss drugs other than semaglutide, he said.

No heterogeneity by LVEF

STEP-HFpEF randomly assigned 529 patients free of diabetes with an LVEF greater than or equal to 45%, a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 kg/m2, and NYHA functional status of 2-4 to either a placebo injection or 2.4-mg semaglutide subcutaneously once a week (the dose used for weight reduction) atop standard care.

As previously reported, those assigned to semaglutide showed significant improvements at 1 year in symptoms and in physical limitation, per changes in KCCQ-CSS, and weight loss, compared with the control group. Their exercise capacity, as measured by 6MWD, also improved.

The more weight patients lost while taking semaglutide, the better their KCCQ-CSS and 6MWD outcomes, a prior secondary analysis suggested. But the STEP-HFpEF researchers said weight loss did not appear to explain all of their gains, compared with usual care.

For the current analysis, the 263 patients assigned to receive semaglutide and 266 control patients were divided into three groups by baseline LVEF and compared for the same outcomes.

The semaglutide group, compared with control patients, also showed a significantly increased hierarchical composite win ratio, 1.72 (95% CI, 1.37-2.15; P < .001), that was consistent across LVEF categories and that accounted for all-cause mortality, HF events, KCCQ-CSS and 6MWD changes, and change in CRP.

Limitations make it hard to generalize the results, the authors caution. Well over 90% of the participants were White patients, for example, and the overall trial was not powered to show subgroup differences.

Given the many patients with HFpEF who have a cardiometabolic phenotype and are with overweight or obesity, write Dr. Butler and colleagues, their treatment approach “may ultimately include combination therapy with SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists, given their non-overlapping and complementary mechanisms of action.”

Dr. Fonarow noted that both MRAs and sacubitril-valsartan offer clinical benefits for patients with HF and LVEF “in the 41%-60% range” that are evident “across BMI categories.”

So it’s likely, he said, that those medications as well as SGLT2 inhibitors will be used along with GLP-1 receptor agonists for patients with HFpEF and obesity.

STEP-HFpEF was funded by Novo Nordisk. Dr. Butler and the other authors disclose consulting for many companies, a list of which can be found in the report. Dr. Fonarow reports consulting for multiple companies. Dr. McMurray discloses consulting for AstraZeneca. Dr. Ostrominski reports no relevant disclosures. Dr. Vaduganathan discloses receiving grant support, serving on advisory boards, or speaking for multiple companies and serving on committees for studies sponsored by AstraZeneca, Galmed, Novartis, Bayer AG, Occlutech, and Impulse Dynamics.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

AT HFSA 2023