User login

Though common, sexual pain disorders in women are often difficult to identify and treat because of the complexity of potential underlying causes. This article will define and describe these conditions in an effort to provide evaluation and treatment strategies for the primary care provider.

SEXUAL PAIN DISORDERS

Dyspareunia is defined as genital pain that may occur before, during, or after vaginal penetration, thus interfering with sexual intercourse and causing marked personal distress and/or interpersonal difficulty.1 Categorization of the condition as lifelong (primary) or acquired (secondary), generalized or situational, may indicate possible underlying causes. Physiological, psychological, or combined factors may be at play. It should be noted that, according to the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DMS-IV-TR),1 painful penetration is not diagnosed as dyspareunia if it is solely the result of lack of lubrication, the physiological effect of a medication, or attributable to the patient’s general medical condition.

Painful intercourse is a prevalent symptom among sexually active women. Between 8% and 21% of women in the general population and 10% of those ages 57 to 85 have been estimated to experience significant dyspareunia.2,3 For some women, sexual pain leads to avoidance of sexual intercourse or contact. Other women remain sexually active despite persistently painful intercourse.

Transient pain during intercourse is predictable in certain situations, such as times of stress, with frequent intercourse (eg, in attempts to conceive), intercourse after a prolonged hiatus from it, or hymenal rupture at coitarche. Dyspareunia, particularly deep dyspareunia, may occur with midcycle intercourse due to normal local inflammation that occurs with ovulation (mittelschmerz).

A second sexual pain disorder experienced by women is vaginismus, which is defined as recurrent or persistent involuntary contraction or spasm of the musculature of the outer third of the vagina (the perineal and levator muscles) that interferes with vaginal penetration, whether associated with sexual intercourse, speculum insertion, or tampon use.1,4-6 Vaginismus may be a cause or a consequence of dyspareunia. This condition is perhaps best described as pelvic floor motor or muscular instability,7 because it can be characterized by:

1) Hypertonicity (reduced ability to relax)

2) Hypocontractility (reduced ability to contract) or

3) Resting muscular instability (as measured by electromyelography [EMG]).8

According to DSM-IV-TR criteria,1 vaginismus also causes marked personal distress or interpersonal difficulty and is not due exclusively to the direct physiological effects of a general medical condition. Vaginismus may occur as a result of psychological factors, such as fear of penetration, or as a conditioned response to pain.

Dyspareunia and Vaginismus: A Clinical Case

Anna is a 30-year-old woman who has been married for three years. She reports that initially, intercourse with her husband was satisfying and pleasurable. She desired sex and was easily aroused and orgasmic. However, when she began to experience a burning pain during intercourse, she tried at first to ignore it, hoping that it would go away on its own. Anticipating pain, she started to avoid sex. When she finally saw her clinician, she was given a diagnosis of candidiasis and responded well to medication.

Although the physical cause of Anna’s dyspareunia was resolved, she continued to be tense when she anticipated an opportunity for sex, associating it with the prior painful experiences. When the couple did attempt vaginal intercourse, penetration was difficult and painful in a different way; it seemed as if the opening to her vagina was closing up, that it was becoming too tight. Anna felt frustrated with herself and her body and worried that her husband would give up on her.

She returned to her clinician, who referred her to a sex therapist. Anna was anxious and skeptical at first but also highly motivated to resolve the pain and resume her previously satisfying sex life. The therapist explained the connection between Anna’s original experience of dyspareunia and the anxiety/avoidance pattern that had developed, causing her pelvic floor muscles to overcontract involuntarily and to make penetration both difficult and uncomfortable. Even though the original physical source of painful intercourse was resolved, Anna had gone on to develop anticipatory anxiety, triggering secondary vaginismus—an automatic, protective response against anticipated pain.

A brief course of cognitive behavioral sex therapy helped Anna to resolve her anxiety, relax her pelvic floor muscles, and gradually return to satisfying sex.

CAUSES OF DYSPAREUNIA

There is a wide and confusing spectrum of causes of primary and secondary dyspareunia. Primary dyspareunia, the less common condition, is associated with imperforate or microperforate hymen, congenital vulvovaginal abnormalities, and acquired vulvovaginal abnormalities resulting from genital surgery, modification, or infundibulation.9

Secondary dyspareunia, or painful intercourse that occurs after a history of pain-free sex, is most often caused by either vaginal atrophy or vulvodynia. Vaginal atrophy, resulting from low circulating estrogen, may cause symptoms of itching, dryness, and irritation; it is experienced by about 40% of postmenopausal women,10 as well as many premenopausal women who take low-dose estrogen oral contraceptives.11-13

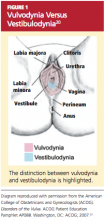

Vulvodynia, which affects 16% of women, refers to vulvar pain, usually described as a burning or cutting sensation, with no significant physical changes seen on examination.7,8,14 Vulvodynia may be localized or generalized to the entire vulva and provoked or unprovoked. Vestibulodynia, which is a subtype of vulvodynia, refers to unexplained pain in the vestibule of the vaginal introitus; the only physical finding may be erythema. Provoked vestibulodynia is the most common form of introital pain, affecting 3% to 15% of women.15-17

Both vulvodynia and vestibulodynia have been explained as neurosensory disorders that are triggered by stimuli such as repeated vaginal infections or long-term use of low-dose estrogen oral contraceptives.12 Other less common vulvar conditions that cause dyspareunia include noninfectious skin conditions, such as dermatitis and lichenoid conditions.18 Many women also experience painful vulvar or vaginal irritation due to sensitivity to spermicide on condoms; latex allergy; and/or ingredients in some lubricants, soaps, body perfumes, detergents, or douches.18,19 Less common vulvovaginal conditions associated with dyspareunia include anomalies, infection, radiation effects, and scarring injuries (see Figure 120).

In some cases, dyspareunia is caused by conditions involving the uterus, ovaries, bladder, or rectum. Uterine conditions include myomas, adenomyosis, endometriosis, retroversion, or retroflexion.21,22 In the case of prolapsed uterus, contact with the cervix or uterus may result in what is described by the patient as “an electric shock” or “stabbing” or “shooting” pain.23

Ovarian cysts, intermittent ovarian torsion, and hydrosalpinx can each cause painful intercourse. Associated bladder and urinary tract conditions include urinary tract infection; urethral caruncle or diverticulum; urethral atrophy resulting from low circulating estrogen in women of any age; and interstitial cystitis, which is usually associated with pain after intercourse and/or during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle.22,24 Anorectal inflammatory conditions, such as lichen sclerosis, Crohn’s disease, and severe constipation with or without hemorrhoids, may be causes of dyspareunia. In rare instances, dyspareunia may be a sign of a tumor in the urogenital or lower GI tract.25,26

Dyspareunia may be indicative of pelvic adhesions resulting from surgery or inflammatory conditions, such as current or past pelvic inflammatory disease.22 The majority (50% to 80%) of women with endometriosis complain of pain with deep thrusting during coitus,27 which is most severe before menstruation and in sexual positions in which the woman has less control over the depth and force of penetration.

Musculoskeletal conditions associated with dyspareunia include scoliosis, levator ani muscle myalgia, and levator ani/pelvic floor musculature spasm.28,29 These may be primary or secondary to another condition that causes deep dyspareunia and may involve pain in the lower back, sacroiliac joint, piriformis, or obturator internus.28

Neurologic conditions, such as pudendal neuralgia and sciatica, can also be associated with pelvic floor injuries during childbirth, nerve entrapment, or straddle injuries.12 Genital piercing and cutting can lead to painful neuromas, neurofibromas, and neuralgia.30

Finally, whether or not identifiable physical causes exist, the experience of pain can be triggered or exacerbated by psychosocial factors. When vaginal penetration has been painful, a pattern of anticipatory anxiety and fear is common. Certain cognitive styles are also associated with dyspareunia. Examples include hypervigilance (“I’m just waiting for it to start hurting”) and catastrophizing (“This hurts so much that I’m going to have to give up having sex altogether”).31,32

Generalized anxiety and somatization, defined as the tendency to experience a variety of physical symptoms without physical origin in reaction to stress, may predispose a woman to experience dyspareunia.1,31 Relationship distress is another related psychosocial factor.33 Even in relationships that are for the most part positive, a woman’s reluctance to communicate her sexual needs may result in foreplay and stimulation that are inadequate to achieve arousal and lubrication.

EVALUATION OF THE PATIENT

Any woman who reports pain during intercourse should undergo a careful history and physical exam directed toward detection of signs of vaginal atrophy (especially women who are menopausal or taking oral estrogen-containing hormonal contraceptives), vulvodynia, vestibulodynia, and other physical and psychological conditions that can cause sexual pain.

A sexual pain history should be taken, focusing on pain experienced with intercourse and/or with tampon or speculum insertion. Pain assessment includes location, intensity, quality (burning, shooting, or dull pain), and duration of the pain. The clinician should ask whether penetrative sex has ever been pain-free to assess for a lifelong or situational condition. Pain frequency, kinds of associated activities, and factors that exacerbate or alleviate the symptom of pain should be clarified. Assessment should include questions about relationship distress; sexual pain can exert negative impact on the relationship, which can then exacerbate sexual pain by impairing arousal. It is important to ascertain whether pain occurs or has occurred with all of the patient’s sexual partners.

The patient should be asked what she identifies as the source of her pain. What treatments have been tried, whether they have been helpful, and what treatments the patient thinks might be effective should all be addressed. The International Pelvic Pain Society34 offers a comprehensive pelvic pain assessment form (see box, “Resources for Clinicians and Patients,” below), which includes the short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire35 for describing and documenting characteristics of pain.

A detailed sexual function history begins with an assessment of sexual function in each domain (desire, arousal, orgasm).36 Other sexual problems, such as vaginal dryness, lack of desire or arousal, inability to experience orgasm, and forced or coerced sex should be identified. The clinician ascertains distress related to the patient’s sexual symptoms (eg, “How bothered are you by the pain you experience with intercourse?”). Information about her partner’s sexual functioning can be relevant, since delayed ejaculation may involve prolonged, ultimately painful intercourse.37 Commonly used objective assessment instruments for female sexual function include the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI),38 the Sexual Function Questionnaire,39 and the Female Sexual Distress Scale (FSDS).40

A complete evaluation includes relevant medical, surgical, obstetric, and social history, along with a review of systems (see Table 1,34,38-40).

Medication History

A thorough assessment identifies OTC and prescription medications, including contraceptive methods. Long-term use of oral combined contraceptives has been associated with vaginal atrophy and vulvodynia.12 Clarifying whether the patient is using condoms with nonoxynol 9 is important, since this spermicide can cause painful irritation in some women.19 An allergy or sensitivity to latex in condoms or to chemicals in some lubricants can also cause irritation.

Physical Examination

The vulva should be inspected for signs of pallor, loss or thinning of hair, and clitoral shrinkage or shrinkage of the labia minora or majora. These can be signs of atrophy due to low estrogen. The vulva is also examined for skin changes, including inflammation, excoriation, scarring, fissuring, laceration, inability to retract the clitoral hood or complete loss of the clitoris by overlying tissue, and trauma.18 Additional assessment is needed for women with infundibulation in cases of female circumcision (also referred to as genital mutilation), as practiced in parts of the Middle East and Africa.30,41 A water-based lubricant, ideally warmed, can be used at the introitus and on the outer speculum blades to minimize discomfort during the exam without interfering with cytology, if a Pap smear is also being performed.42

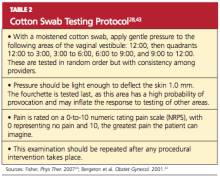

For women with introital pain, a “cotton swab test” is performed to quantify, localize, and map the pain (see Table 2,28,43).

The hymen is inspected and its morphology documented, particularly in the woman or girl with recent coitarche. The vagina is inspected for presence of a septum.14 Signs of atrophy include lack of lubrication, easy bleeding, fissures, discomfort even with use of a small speculum, and petechiae.18 Atrophic mucosa will appear flat and pale, with no evidence of normal rugae. The tissue’s elasticity will have decreased.

If there is suspicion of pelvic organ prolapse, vaginitis, or sexually transmitted infection, further assessments are made. Using one intravaginal finger if two fingers are painful, the clinician systematically palpates the urethra, bladder, bilateral fornices, posterior fornix, cervix, adnexa, and uterus in an attempt to reproduce the pain experienced during intercourse.29 Uterine size, contour, mobility, and any nodularity or irregularity are all noted.

During the pelvic examination, the clinician uses a hand mirror to show the patient the depth of penetration with the examining finger, a speculum, or a vaginal dilator—demonstrating the diameter of the introitus and vaginal canal, if possible. This is a valuable opportunity to educate the patient regarding her genital anatomy in addition to any physical findings that might explain her pain.

A rectovaginal examination is important for identifying constipation, hemorrhoids, or nodules along the rectovaginal septum or uterosacral ligaments, possibly indicating endometriosis.21,22 In patients with anal fissures, tensing of the anal sphincter and pelvic floor muscles to slow defecation (or to restrict the diameter of the feces) can result in a paradoxical contraction of the puborectalis portion of the levator ani muscles.28 This creates a vicious cycle of pelvic floor muscle spasm.

Pelvic floor function and strength are systematically evaluated using the Modified Oxford Scale44 or the Brink Scoring System.45 Scoliosis and hip height are assessed by asking the patient to bend over and touch her toes. Curvature of the spine or unequal hip height may indicate musculoskeletal problems that can cause or contribute to pelvic pain during intercourse.

Laboratory Workup

The vaginal maturation index18,46 may be assessed by taking a specimen for wet prep in the office setting or by sending a fixed smear on a slide or in a liquid cytologic preparation to a cytopathology laboratory. Vaginal pH, in combination with a wet prep, can be obtained to help assess for bacterial vaginosis or vaginal candidiasis. Laboratory tests are not regularly required, however, to diagnose and treat dyspareunia. Nevertheless, dyspareunia of musculoskeletal origin may require diagnostic neuromuscular evaluation, including EMG, ultrasonography, and manual assessment.28 These are commonly performed by a physical therapist with expertise in pelvic physical therapy and women’s health.

TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT

Treatment begins with psychosexual education and counseling, in which underlying causes are addressed. The clinician educates the patient about the prevalence and common causes of painful intercourse, assessing what the patient has already done to alleviate the pain and reinforcing constructive and positive behaviors. It is therapeutic to validate the patient’s experience of pain and to explain that both pain and sexuality are mind and body processes. Even if the pain is due to a physical cause, it can have psychologic aspects or sequelae. The clinician normalizes the fact that pain associated with sex can cause anxiety and fear about participating in intercourse and that these are natural, instinctive reactions to pain.47

The patient is given an explanation of any physical and psychologic findings that might be contributing to her pain. This approach gives the patient hope for improvement with education and treatment. The emphasis is on the aspects of her sexual functioning that are still intact and positive features in her sexual history or relationship. A central goal is to minimize self-blame, hopelessness, and anxiety.

The patient is counseled about the need for adequate foreplay and stimulation to promote arousal and lubrication. Masturbation (alone and/or in conjunction with partnered sex) can be discussed as a way to increase vaginal lubrication, blood flow, and comfort with genital touch.

Another helpful strategy is to give the patient permission to take a hiatus from sexual intercourse.47 Women experiencing genital pain often avoid nonsexual affection and other sexual activities with their partners, fearing that they will lead to painful intercourse. In such cases, the woman is encouraged to form an explicit agreement with her partner that they will not have intercourse until she has made progress at managing her pain. The goal is to create greater openness to nonsexual affection and nonpenetrative sexual activity.

The clinician may suggest sensate focus exercises48,49 (see Table 3,4,48,49). In cases of vaginal atrophy and/or dryness, vaginal moisturizers and lubricants can help. Products containing perfumes, warming or tingling agents, parabens, and other chemicals can be irritating in some women.18

For the premenopausal patient using a low-dose oral contraceptive, the clinician’s instinct may be to provide a higher-dose estrogen pill. This may actually be counterproductive, however, because oral estrogen promotes synthesis in the liver of sex hormone–binding globulin, which then reduces circulating estrogen and can exacerbate the problem.50 Although the vast majority of women who use estrogen-containing oral contraceptives do not appear to develop symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy, women who do experience bothersome atrophic symptoms may benefit from switching to an alternative contraceptive method (eg, an intrauterine device). Menopausal women may benefit from a topical estrogen product in the form of a vaginal ring, cream, or tablet.18,51,52

For vulvodynia, medical therapies such as topical anesthetics and centrally acting medications are under investigation. For cases of provoked vestibulodynia that do not respond to first-line treatment, patients may benefit from pelvic floor physical therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy aimed at pain reduction combined with sex therapy, or vestibulectomy.53,54

Addressing Bowel and Bladder Concerns

The patient with chronic constipation must be educated about the importance of adequate hydration and nutrition for bowel regularity. She is counseled about avoidance of straining or prolonged sitting during defecation and is offered primary treatment for hemorrhoids. A history of rectal bleeding, particularly in the absence of hemorrhoids, may be indicative of an anorectal or a colon malignancy, and the patient with such a history should be referred for further evaluation. The International Foundation for Functional Gastric Disorders (see “Resources” box) provides useful information for patients regarding constipation and associated pelvic floor disorders.

Urinary voiding prior to and following coitus or oral sex may reduce bladder discomfort and infection. Use of a dental dam for oral sex and good oral hygiene with regular dental care may also reduce the incidence of irritation and infection. Educational resources to address bladder function and incontinence can be found in the “Resources” box.

Treatment for Vaginismus

Vaginismus can be treated with desensitization techniques, including relaxation training, dilator therapy, pelvic floor therapy, and cognitive behavioral sex therapy, which teaches the patient to relax the introital muscles and give her the experience of controlled, pain-free penetration.55,56 A fundamental technique of relaxation training is deep breathing. Understanding the mechanics of breathing is important for physiologic quieting of the autonomic nervous system and facilitating relaxation of the pelvic floor.57

Dilator therapy can be used for treatment of vaginismus and vaginal stenosis, although in the presence of adhesions or a septum, lysis may be required first. A vaginal dilator can be inserted for approximately 15 minutes daily. Once the dilator passes easily with no painful stretching sensation, the patient should move to the next size larger dilator. The dilator can also be moved slowly and gently in and out and from side to side.

Topical lidocaine (5%) gel or ointment can facilitate use of the dilator. The patient applies a small amount to the site of vulvar pain (commonly the posterior fourchette of the introitus) with the tip of a cotton swab 15 to 30 minutes before inserting the dilator.

Some vaginal dilators may be obtained directly by the patient (see “Resources” box below), while others require a prescription. Graduated or vibrating dildos can be obtained at retail outlets selling sexual products. A clean finger can also be used for dilation.

Pelvic Floor Therapy

Several modalities offered by specialized physical therapists are used to improve pelvic and vulvovaginal blood flow and control over the pelvic musculature. This may help to alleviate pain with intercourse, particularly in patients with signs of pelvic floor weakness, poor muscle control, or instability. Modalities include pelvic floor exercises and manual therapy techniques (eg, transvaginal trigger point therapy, transvaginal and/or transrectal massage, dry needling of a trigger point).4,58 Surface electrical stimulation of the pelvic floor musculature is also used to decrease pain and muscle spasm.59

Kegel exercises60 (ie, tensing and relaxing the pelvic floor muscles) may help a patient gain control over both contraction and relaxation of the pelvic muscles.60,61 However, if palpation of the pelvic floor reveals tight, inelastic, and dense tissue, assessment and grading of muscle strength may be misleading. For example, the pelvic floor may demonstrate a state of constant contraction (hypertonicity or a “short pelvic floor”).62 Attempts at voluntary contraction of a muscle in this state may be perceived and graded incorrectly as weak.

Traditional Kegel exercises are contraindicated in women with muscle hypertonicity and an inability to relax these muscles. Some practitioners use the term “reverse Kegel” to describe active, bearing-down exercises that increase pelvic floor relaxation. Biofeedback training (surface EMG and/or rehabilitative ultrasound imaging) can be useful to reeducate resting muscle tone of the pelvic floor. Breathing, tactile, verbal, and imagery cues are essential.61,62

Cognitive Behavioral Sex Therapy

This specialized form of psychotherapy helps patients identify cognitive, emotional, and relationship factors that contribute to their pain. Patients learn coping strategies, including relaxation techniques and modification of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors to reduce anxiety, tension, and pain. As pain management improves, the focus shifts to enhancing sexual functioning, including restarting the sexual relationship if sex has been avoided because of pain.63

WHEN AND WHERE TO REFER

Referral is appropriate if the patient’s condition worsens, is unresponsive to therapy, or requires specialized evaluation and treatment. Sex therapy, psychotherapy, or couples counseling may be indicated in more complex cases in which a sexual disorder and significant psychologic and/or relationship problems coexist. Examples may include an unresolved history of sexual abuse, clinical anxiety or depression, sexual phobia or aversion, and general relationship distress. To locate qualified sex therapists, see the “Resources” box.

Physical therapy may be prescribed if the patient demonstrates or reports persistent pain or lack of improvement with initial pelvic floor therapy, an inability to use a dilator on her own, or increased pain or perceived tightness while using a dilator; or if she develops pelvic or perineal pain at rest. To locate specially trained physical therapists, see the “Resources” box.

CONCLUSION

Though commonly seen in primary care, sexual pain disorders in women are often difficult to diagnose and treat because of the confusing array of possible contributory factors. This article presents an overview of possible presentations, causes, diagnostic strategies, and treatment options, integrating evidence-based approaches from the fields of medicine, psychology, and physical therapy.

REFERENCES

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DMS-IV-TR). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000:554-558.

2. Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, et al. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(8): 762-774.

3. Latthe P, Latthe M, Say L, et al. WHO systematic review of prevalence of chronic pelvic pain: a neglected reproductive health morbidity. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:177-183.

4. Simons DG, Travell JG, Simons LS, Cummings BD. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:vol 2, chap 6:110-131.

5. Perry CP. Vulvodynia. In: Howard FM, Perry CP, Carter JE, El-Minawi AM, eds. Pelvic Pain: Diagnosis and Management. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000:204-211.

6. Glazer HI, Jantos M, Hartmann EH, Swencioniswom C. Electromyographic comparisons of the pelvic floor in women with dysesthetic vulvodynia and asymptomatic women. J Reprod Med. 1998;43(11):959-962.

7. Binik YM. The DSM diagnostic criteria for vaginismus. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39(2):278-291.

8. Haefner HK. Report of the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease terminology and classification of vulvodynia. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2007;11(1):48-49.

9. Huffman JW. Dyspareunia of vulvo-vaginal origin: causes and management. Postgrad Med. 1983;73(2):287-296.

10. Krychman ML. Vaginal estrogens for treatment of dyspareunia. J Sex Med. 2010 Nov 22;8:666-674. [Epub ahead of print]

11. Kao A, Binik YM, Kapuscinski A, Khalifé S. Dyspareunia in postmenopausal women: a critical review. Pain Res Manag. 2008;13(3):243-254.

12. Steege JF, Zolnoun DA. Evaluation and treatment of dyspareunia. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113 (5):1124-1136.

13. Lüdicke F, Johannisson E, Helmerhorst FM, et al. Effect of a combined oral contraceptive containing 3 mg of drospirenone and 30 microg of ethinyl estradiol on the human endometrium. Fertil Steril. 2001;76(1):102-107.

14. Strauhal MJ, Frahm J, Morrison P, et al. Vulvar pain: a comprehensive review. J Womens Health Phys Ther. 2007;31(3):6-22.

15. Harlow BL, Stewart EG. A population-based assessment of chronic unexplained vulvar pain: have we underestimated the prevalence of vulvodynia? J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2003;58(2): 82-88.

16. Goetsch MF. Vulvar vestibulitis: prevalence and historic features in a general gynecologic practice population. Am J Obstetr Gynecol. 1991; 164(6 pt 1):1609-1616.

17. Danielsson I, Sjöberg I, Stenlund H, Wikman M. Prevalence and incidence of prolonged and severe dyspareunia in women: results from a population study. Scand J Public Health. 2003;31 (2):113-118.

18. Mac Bride MB, Rhodes DJ, Shuster LT. Vulvovaginal atrophy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(1): 87-94.

19. Barditch-Crovo P, Witter F, Hamzeh F, et al. Quantitation of vaginally administered nonoxynol-9 in premenopausal women. Contraception. 1997;55(4):261-263.

20. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Disorders of the Vulva. ACOG Patient Education Pamphlet AP088. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2007.

21. Ferrero S, Abbamonte LH, Giordano M, et al. Uterine myomas, dyspareunia, and sexual function. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(5):1504-1510.

22. Walid MS, Heaton RL. Dyspareunia: a complex problem requiring a selective approach. Sex Health. 2009;6(3):250-253.

23. Sobghol SS, Alizadeli Charndabee SM. Rate and related factors of dyspareunia in reproductive age women: a cross-sectional study. Int J Impot Res. 2007;19(1):88-94.

24. Ferrero S, Ragni N, Remorgida V. Deep dyspareunia: causes, treatments, and results. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;20(4):394-399.

25. Kim IY, Sadeghi F, Slawin KM. Dyspareunia: an unusual presentation of leiomyoma of the bladder. Rev Urol. 2001;3(3):152-154.

26. Akbulut S, Cakabay B, Sezgin A, Ozmen C. A rare cause of severe dyspareunia: a case report and literature review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009 Apr 26. [Epub ahead of print.]

27. Ferrero S, Esposito F, Abbamonte LH, et al. Quality of sex life in women with endometriosis and deep dyspareunia. Fertil Steril. 2005;83(3): 573-579.

28. Fisher KA. Management of dyspareunia and associated levator ani muscle overactivity. Phys Ther. 2007;87(7):935-941.

29. Bø K, Sherburn M. Evaluation of female pelvic-floor muscle function and strength. Phys Ther. 2005;85(3):269-282.

30. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Female Genital Mutilation and its Management. Green-top Guideline No 53 (May 2009). www.rcog.org.uk/files/rcog-corp/Green Top53FemaleGenitalMutilation.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2011.

31. Payne KA, Binik YM, Amsel R, Khalifé S. When sex hurts, anxiety and fear orient attention towards pain. Eur J Pain. 2005;9(4):427-436.

32. Pukall CF, Binik YM, Khalifé S, et al. Vestibular tactile and pain thresholds in women with vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Pain. 2002;96(1-2):163-175.

33. Meana M, Binik YM, Khalifé S, Cohen D. Psychosocial correlates of pain attributions in women with dyspareunia. Psychosomatics. 1999:40(6): 497-502.

34. Pelvic Pain Assessment Form (2008). International Pelvic Pain Society. www.pelvicpain.org/pdf/History_and_Physical_Form/IPPS-H&PformR-MSW.pdf. Accessed April 11, 2011.

35. Melzack R. The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pain. 1987;30(2):191-197.

36. Basson R. Sexuality and sexual disorders in women. In: Clinical Updates in Women’s Health Care Monograph. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2003;2(2):1-94.

37. Oberg K, Sjögren Fugl-Meyer K. On Swedish women’s distressing sexual dysfunctions: some concomitant conditions and life satisfaction. J Sex Med. 2005;2(2):169-180.

38. Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(2):191-208.

39. Quirk FH, Heiman JR, Rosen RC, et al. Development of a sexual function questionnaire for clinical trials of female sexual dysfunction. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2002;11(3): 277-289.

40. Derogatis LR, Rosen R, Leiblum S, et al. The Female Sexual Distress Scale (FSDS): Initial validation of a standardized scale for assessment of sexually related personal distress in women. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28(4):317-330.

41. van Lankveld JJ, Granot M, Weijmar Schultz WC, et al. Women’s sexual pain disorders. J Sex Med. 2010;7(1 pt 2):615-631.

42. Hathaway JK, Pathak PK, Maney R. Is liquid-based Pap testing affected by water-based lubricant? Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(1):66-70.

43. Bergeron S, Binik YM, Khalifé S, et al. Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: reliability of diagnosis and evaluation of current diagnostic criteria. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(1):45-51.

44. Laycock J, Holmes DM. The place of physiotherapy in the management of pelvic floor dysfunction. Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;5:194-199.

45. Brink CA, Sampselle CM, Wells TJ, et al. A digital test for pelvic muscle strength in older women with urinary incontinence. Nurs Res. 1989;38(4):196-199.

46. Hess R, Austin RM, Dillon S, et al. Vaginal maturation index self-sample collection in mid-life women: acceptability and correlation with physician-collected samples. Menopause. 2008; 15(4 pt 1):726-729.

47. Haefner HK, Collins ME, Davis GD, et al. The vulvodynia guideline. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2005; 9(1):40-51.

48. Albaugh JA, Kellogg-Spadt S. Sensate focus and its role in treating sexual dysfunction. Urol Nurs. 2002;22(6):402-403.

49. Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human Sexual Inadequacy. New York, NY: Ishi Press; 2010: 67-75.

50. Panzer C, Wise S, Fantini G, et al. Impact of oral contraceptives on sex hormone–binding globulin and androgen levels: a retrospective study in women with sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2006;3(1):104-113.

51. Suckling J, Kennedy R, Lethaby A. Local oestrogen for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006; (4):CD001500.

52. Johnston SL, Farrell SA, Bouchard C, et al; SOGC joint Committee–Clinical Practice Gynaecology and Urogynaecology. The detection and management of vaginal atrophy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2004;26(5):503-515.

53. Bergeron S, Khalifé S, Glazer HI, Binik YM. Surgical and behavioral treatments for vestibulodynia: two-and-one-half year follow-up and predictors of outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(1): 159-166.

54. Pukall CF, Smith KB, Chamberlain SM. Provoked vestibulodynia. Womens Health (Lond Engl). 2007;3(5):583-592.

55. van Lankveld JJ, ter Kuile MM, de Groot HE, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for women with lifelong vaginismus: a randomized waiting-list controlled trial of efficacy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(1):168-178.

56. McGuire H, Hawton K. Interventions for vaginismus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(1): CD001760.

57. Calais-Germain B. Analysis of the principal types of breathing. In: Calais-Germain B. Anatomy of Breathing. New York, NY: Eastland Press; 2006:133-158.

58. Carter J. Abdominal wall and pelvic myofascial trigger points. In: Howard FM, Perry P, Carter J, El-Minawi AM. Pelvic Pain: Diagnosis and Management. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000:315-358.

59. Gentilcore-Saulnier E, McLean L, Goldfinger C, et al. Pelvic floor muscle assessment outcomes in women with and without provoked vestibulodynia and the impact of a physical therapy program. J Sex Med. 2010;7(2 pt 2):1003-1022.

60. Kegel AH. Physiologic therapy for urinary stress incontinence. JAMA. 1951;146(10):915-917.

61. Marques A, Stothers L, Macnab A. The status of pelvic floor muscle training for women. Can Urol Assoc J. 2010;4(6):419-424.

62. FitzGerald MP, Kotarinos R. Rehabilitation of the short pelvic floor. I: Background and patient evaluation. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2003;14(4):261-268.

63. Binik Y, Bergeron S, Khalifé S. Dyspareunia and vaginismus: So-called pain disorders. In: Leiblum S, ed. Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2007: 124-156.

Though common, sexual pain disorders in women are often difficult to identify and treat because of the complexity of potential underlying causes. This article will define and describe these conditions in an effort to provide evaluation and treatment strategies for the primary care provider.

SEXUAL PAIN DISORDERS

Dyspareunia is defined as genital pain that may occur before, during, or after vaginal penetration, thus interfering with sexual intercourse and causing marked personal distress and/or interpersonal difficulty.1 Categorization of the condition as lifelong (primary) or acquired (secondary), generalized or situational, may indicate possible underlying causes. Physiological, psychological, or combined factors may be at play. It should be noted that, according to the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DMS-IV-TR),1 painful penetration is not diagnosed as dyspareunia if it is solely the result of lack of lubrication, the physiological effect of a medication, or attributable to the patient’s general medical condition.

Painful intercourse is a prevalent symptom among sexually active women. Between 8% and 21% of women in the general population and 10% of those ages 57 to 85 have been estimated to experience significant dyspareunia.2,3 For some women, sexual pain leads to avoidance of sexual intercourse or contact. Other women remain sexually active despite persistently painful intercourse.

Transient pain during intercourse is predictable in certain situations, such as times of stress, with frequent intercourse (eg, in attempts to conceive), intercourse after a prolonged hiatus from it, or hymenal rupture at coitarche. Dyspareunia, particularly deep dyspareunia, may occur with midcycle intercourse due to normal local inflammation that occurs with ovulation (mittelschmerz).

A second sexual pain disorder experienced by women is vaginismus, which is defined as recurrent or persistent involuntary contraction or spasm of the musculature of the outer third of the vagina (the perineal and levator muscles) that interferes with vaginal penetration, whether associated with sexual intercourse, speculum insertion, or tampon use.1,4-6 Vaginismus may be a cause or a consequence of dyspareunia. This condition is perhaps best described as pelvic floor motor or muscular instability,7 because it can be characterized by:

1) Hypertonicity (reduced ability to relax)

2) Hypocontractility (reduced ability to contract) or

3) Resting muscular instability (as measured by electromyelography [EMG]).8

According to DSM-IV-TR criteria,1 vaginismus also causes marked personal distress or interpersonal difficulty and is not due exclusively to the direct physiological effects of a general medical condition. Vaginismus may occur as a result of psychological factors, such as fear of penetration, or as a conditioned response to pain.

Dyspareunia and Vaginismus: A Clinical Case

Anna is a 30-year-old woman who has been married for three years. She reports that initially, intercourse with her husband was satisfying and pleasurable. She desired sex and was easily aroused and orgasmic. However, when she began to experience a burning pain during intercourse, she tried at first to ignore it, hoping that it would go away on its own. Anticipating pain, she started to avoid sex. When she finally saw her clinician, she was given a diagnosis of candidiasis and responded well to medication.

Although the physical cause of Anna’s dyspareunia was resolved, she continued to be tense when she anticipated an opportunity for sex, associating it with the prior painful experiences. When the couple did attempt vaginal intercourse, penetration was difficult and painful in a different way; it seemed as if the opening to her vagina was closing up, that it was becoming too tight. Anna felt frustrated with herself and her body and worried that her husband would give up on her.

She returned to her clinician, who referred her to a sex therapist. Anna was anxious and skeptical at first but also highly motivated to resolve the pain and resume her previously satisfying sex life. The therapist explained the connection between Anna’s original experience of dyspareunia and the anxiety/avoidance pattern that had developed, causing her pelvic floor muscles to overcontract involuntarily and to make penetration both difficult and uncomfortable. Even though the original physical source of painful intercourse was resolved, Anna had gone on to develop anticipatory anxiety, triggering secondary vaginismus—an automatic, protective response against anticipated pain.

A brief course of cognitive behavioral sex therapy helped Anna to resolve her anxiety, relax her pelvic floor muscles, and gradually return to satisfying sex.

CAUSES OF DYSPAREUNIA

There is a wide and confusing spectrum of causes of primary and secondary dyspareunia. Primary dyspareunia, the less common condition, is associated with imperforate or microperforate hymen, congenital vulvovaginal abnormalities, and acquired vulvovaginal abnormalities resulting from genital surgery, modification, or infundibulation.9

Secondary dyspareunia, or painful intercourse that occurs after a history of pain-free sex, is most often caused by either vaginal atrophy or vulvodynia. Vaginal atrophy, resulting from low circulating estrogen, may cause symptoms of itching, dryness, and irritation; it is experienced by about 40% of postmenopausal women,10 as well as many premenopausal women who take low-dose estrogen oral contraceptives.11-13

Vulvodynia, which affects 16% of women, refers to vulvar pain, usually described as a burning or cutting sensation, with no significant physical changes seen on examination.7,8,14 Vulvodynia may be localized or generalized to the entire vulva and provoked or unprovoked. Vestibulodynia, which is a subtype of vulvodynia, refers to unexplained pain in the vestibule of the vaginal introitus; the only physical finding may be erythema. Provoked vestibulodynia is the most common form of introital pain, affecting 3% to 15% of women.15-17

Both vulvodynia and vestibulodynia have been explained as neurosensory disorders that are triggered by stimuli such as repeated vaginal infections or long-term use of low-dose estrogen oral contraceptives.12 Other less common vulvar conditions that cause dyspareunia include noninfectious skin conditions, such as dermatitis and lichenoid conditions.18 Many women also experience painful vulvar or vaginal irritation due to sensitivity to spermicide on condoms; latex allergy; and/or ingredients in some lubricants, soaps, body perfumes, detergents, or douches.18,19 Less common vulvovaginal conditions associated with dyspareunia include anomalies, infection, radiation effects, and scarring injuries (see Figure 120).

In some cases, dyspareunia is caused by conditions involving the uterus, ovaries, bladder, or rectum. Uterine conditions include myomas, adenomyosis, endometriosis, retroversion, or retroflexion.21,22 In the case of prolapsed uterus, contact with the cervix or uterus may result in what is described by the patient as “an electric shock” or “stabbing” or “shooting” pain.23

Ovarian cysts, intermittent ovarian torsion, and hydrosalpinx can each cause painful intercourse. Associated bladder and urinary tract conditions include urinary tract infection; urethral caruncle or diverticulum; urethral atrophy resulting from low circulating estrogen in women of any age; and interstitial cystitis, which is usually associated with pain after intercourse and/or during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle.22,24 Anorectal inflammatory conditions, such as lichen sclerosis, Crohn’s disease, and severe constipation with or without hemorrhoids, may be causes of dyspareunia. In rare instances, dyspareunia may be a sign of a tumor in the urogenital or lower GI tract.25,26

Dyspareunia may be indicative of pelvic adhesions resulting from surgery or inflammatory conditions, such as current or past pelvic inflammatory disease.22 The majority (50% to 80%) of women with endometriosis complain of pain with deep thrusting during coitus,27 which is most severe before menstruation and in sexual positions in which the woman has less control over the depth and force of penetration.

Musculoskeletal conditions associated with dyspareunia include scoliosis, levator ani muscle myalgia, and levator ani/pelvic floor musculature spasm.28,29 These may be primary or secondary to another condition that causes deep dyspareunia and may involve pain in the lower back, sacroiliac joint, piriformis, or obturator internus.28

Neurologic conditions, such as pudendal neuralgia and sciatica, can also be associated with pelvic floor injuries during childbirth, nerve entrapment, or straddle injuries.12 Genital piercing and cutting can lead to painful neuromas, neurofibromas, and neuralgia.30

Finally, whether or not identifiable physical causes exist, the experience of pain can be triggered or exacerbated by psychosocial factors. When vaginal penetration has been painful, a pattern of anticipatory anxiety and fear is common. Certain cognitive styles are also associated with dyspareunia. Examples include hypervigilance (“I’m just waiting for it to start hurting”) and catastrophizing (“This hurts so much that I’m going to have to give up having sex altogether”).31,32

Generalized anxiety and somatization, defined as the tendency to experience a variety of physical symptoms without physical origin in reaction to stress, may predispose a woman to experience dyspareunia.1,31 Relationship distress is another related psychosocial factor.33 Even in relationships that are for the most part positive, a woman’s reluctance to communicate her sexual needs may result in foreplay and stimulation that are inadequate to achieve arousal and lubrication.

EVALUATION OF THE PATIENT

Any woman who reports pain during intercourse should undergo a careful history and physical exam directed toward detection of signs of vaginal atrophy (especially women who are menopausal or taking oral estrogen-containing hormonal contraceptives), vulvodynia, vestibulodynia, and other physical and psychological conditions that can cause sexual pain.

A sexual pain history should be taken, focusing on pain experienced with intercourse and/or with tampon or speculum insertion. Pain assessment includes location, intensity, quality (burning, shooting, or dull pain), and duration of the pain. The clinician should ask whether penetrative sex has ever been pain-free to assess for a lifelong or situational condition. Pain frequency, kinds of associated activities, and factors that exacerbate or alleviate the symptom of pain should be clarified. Assessment should include questions about relationship distress; sexual pain can exert negative impact on the relationship, which can then exacerbate sexual pain by impairing arousal. It is important to ascertain whether pain occurs or has occurred with all of the patient’s sexual partners.

The patient should be asked what she identifies as the source of her pain. What treatments have been tried, whether they have been helpful, and what treatments the patient thinks might be effective should all be addressed. The International Pelvic Pain Society34 offers a comprehensive pelvic pain assessment form (see box, “Resources for Clinicians and Patients,” below), which includes the short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire35 for describing and documenting characteristics of pain.

A detailed sexual function history begins with an assessment of sexual function in each domain (desire, arousal, orgasm).36 Other sexual problems, such as vaginal dryness, lack of desire or arousal, inability to experience orgasm, and forced or coerced sex should be identified. The clinician ascertains distress related to the patient’s sexual symptoms (eg, “How bothered are you by the pain you experience with intercourse?”). Information about her partner’s sexual functioning can be relevant, since delayed ejaculation may involve prolonged, ultimately painful intercourse.37 Commonly used objective assessment instruments for female sexual function include the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI),38 the Sexual Function Questionnaire,39 and the Female Sexual Distress Scale (FSDS).40

A complete evaluation includes relevant medical, surgical, obstetric, and social history, along with a review of systems (see Table 1,34,38-40).

Medication History

A thorough assessment identifies OTC and prescription medications, including contraceptive methods. Long-term use of oral combined contraceptives has been associated with vaginal atrophy and vulvodynia.12 Clarifying whether the patient is using condoms with nonoxynol 9 is important, since this spermicide can cause painful irritation in some women.19 An allergy or sensitivity to latex in condoms or to chemicals in some lubricants can also cause irritation.

Physical Examination

The vulva should be inspected for signs of pallor, loss or thinning of hair, and clitoral shrinkage or shrinkage of the labia minora or majora. These can be signs of atrophy due to low estrogen. The vulva is also examined for skin changes, including inflammation, excoriation, scarring, fissuring, laceration, inability to retract the clitoral hood or complete loss of the clitoris by overlying tissue, and trauma.18 Additional assessment is needed for women with infundibulation in cases of female circumcision (also referred to as genital mutilation), as practiced in parts of the Middle East and Africa.30,41 A water-based lubricant, ideally warmed, can be used at the introitus and on the outer speculum blades to minimize discomfort during the exam without interfering with cytology, if a Pap smear is also being performed.42

For women with introital pain, a “cotton swab test” is performed to quantify, localize, and map the pain (see Table 2,28,43).

The hymen is inspected and its morphology documented, particularly in the woman or girl with recent coitarche. The vagina is inspected for presence of a septum.14 Signs of atrophy include lack of lubrication, easy bleeding, fissures, discomfort even with use of a small speculum, and petechiae.18 Atrophic mucosa will appear flat and pale, with no evidence of normal rugae. The tissue’s elasticity will have decreased.

If there is suspicion of pelvic organ prolapse, vaginitis, or sexually transmitted infection, further assessments are made. Using one intravaginal finger if two fingers are painful, the clinician systematically palpates the urethra, bladder, bilateral fornices, posterior fornix, cervix, adnexa, and uterus in an attempt to reproduce the pain experienced during intercourse.29 Uterine size, contour, mobility, and any nodularity or irregularity are all noted.

During the pelvic examination, the clinician uses a hand mirror to show the patient the depth of penetration with the examining finger, a speculum, or a vaginal dilator—demonstrating the diameter of the introitus and vaginal canal, if possible. This is a valuable opportunity to educate the patient regarding her genital anatomy in addition to any physical findings that might explain her pain.

A rectovaginal examination is important for identifying constipation, hemorrhoids, or nodules along the rectovaginal septum or uterosacral ligaments, possibly indicating endometriosis.21,22 In patients with anal fissures, tensing of the anal sphincter and pelvic floor muscles to slow defecation (or to restrict the diameter of the feces) can result in a paradoxical contraction of the puborectalis portion of the levator ani muscles.28 This creates a vicious cycle of pelvic floor muscle spasm.

Pelvic floor function and strength are systematically evaluated using the Modified Oxford Scale44 or the Brink Scoring System.45 Scoliosis and hip height are assessed by asking the patient to bend over and touch her toes. Curvature of the spine or unequal hip height may indicate musculoskeletal problems that can cause or contribute to pelvic pain during intercourse.

Laboratory Workup

The vaginal maturation index18,46 may be assessed by taking a specimen for wet prep in the office setting or by sending a fixed smear on a slide or in a liquid cytologic preparation to a cytopathology laboratory. Vaginal pH, in combination with a wet prep, can be obtained to help assess for bacterial vaginosis or vaginal candidiasis. Laboratory tests are not regularly required, however, to diagnose and treat dyspareunia. Nevertheless, dyspareunia of musculoskeletal origin may require diagnostic neuromuscular evaluation, including EMG, ultrasonography, and manual assessment.28 These are commonly performed by a physical therapist with expertise in pelvic physical therapy and women’s health.

TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT

Treatment begins with psychosexual education and counseling, in which underlying causes are addressed. The clinician educates the patient about the prevalence and common causes of painful intercourse, assessing what the patient has already done to alleviate the pain and reinforcing constructive and positive behaviors. It is therapeutic to validate the patient’s experience of pain and to explain that both pain and sexuality are mind and body processes. Even if the pain is due to a physical cause, it can have psychologic aspects or sequelae. The clinician normalizes the fact that pain associated with sex can cause anxiety and fear about participating in intercourse and that these are natural, instinctive reactions to pain.47

The patient is given an explanation of any physical and psychologic findings that might be contributing to her pain. This approach gives the patient hope for improvement with education and treatment. The emphasis is on the aspects of her sexual functioning that are still intact and positive features in her sexual history or relationship. A central goal is to minimize self-blame, hopelessness, and anxiety.

The patient is counseled about the need for adequate foreplay and stimulation to promote arousal and lubrication. Masturbation (alone and/or in conjunction with partnered sex) can be discussed as a way to increase vaginal lubrication, blood flow, and comfort with genital touch.

Another helpful strategy is to give the patient permission to take a hiatus from sexual intercourse.47 Women experiencing genital pain often avoid nonsexual affection and other sexual activities with their partners, fearing that they will lead to painful intercourse. In such cases, the woman is encouraged to form an explicit agreement with her partner that they will not have intercourse until she has made progress at managing her pain. The goal is to create greater openness to nonsexual affection and nonpenetrative sexual activity.

The clinician may suggest sensate focus exercises48,49 (see Table 3,4,48,49). In cases of vaginal atrophy and/or dryness, vaginal moisturizers and lubricants can help. Products containing perfumes, warming or tingling agents, parabens, and other chemicals can be irritating in some women.18

For the premenopausal patient using a low-dose oral contraceptive, the clinician’s instinct may be to provide a higher-dose estrogen pill. This may actually be counterproductive, however, because oral estrogen promotes synthesis in the liver of sex hormone–binding globulin, which then reduces circulating estrogen and can exacerbate the problem.50 Although the vast majority of women who use estrogen-containing oral contraceptives do not appear to develop symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy, women who do experience bothersome atrophic symptoms may benefit from switching to an alternative contraceptive method (eg, an intrauterine device). Menopausal women may benefit from a topical estrogen product in the form of a vaginal ring, cream, or tablet.18,51,52

For vulvodynia, medical therapies such as topical anesthetics and centrally acting medications are under investigation. For cases of provoked vestibulodynia that do not respond to first-line treatment, patients may benefit from pelvic floor physical therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy aimed at pain reduction combined with sex therapy, or vestibulectomy.53,54

Addressing Bowel and Bladder Concerns

The patient with chronic constipation must be educated about the importance of adequate hydration and nutrition for bowel regularity. She is counseled about avoidance of straining or prolonged sitting during defecation and is offered primary treatment for hemorrhoids. A history of rectal bleeding, particularly in the absence of hemorrhoids, may be indicative of an anorectal or a colon malignancy, and the patient with such a history should be referred for further evaluation. The International Foundation for Functional Gastric Disorders (see “Resources” box) provides useful information for patients regarding constipation and associated pelvic floor disorders.

Urinary voiding prior to and following coitus or oral sex may reduce bladder discomfort and infection. Use of a dental dam for oral sex and good oral hygiene with regular dental care may also reduce the incidence of irritation and infection. Educational resources to address bladder function and incontinence can be found in the “Resources” box.

Treatment for Vaginismus

Vaginismus can be treated with desensitization techniques, including relaxation training, dilator therapy, pelvic floor therapy, and cognitive behavioral sex therapy, which teaches the patient to relax the introital muscles and give her the experience of controlled, pain-free penetration.55,56 A fundamental technique of relaxation training is deep breathing. Understanding the mechanics of breathing is important for physiologic quieting of the autonomic nervous system and facilitating relaxation of the pelvic floor.57

Dilator therapy can be used for treatment of vaginismus and vaginal stenosis, although in the presence of adhesions or a septum, lysis may be required first. A vaginal dilator can be inserted for approximately 15 minutes daily. Once the dilator passes easily with no painful stretching sensation, the patient should move to the next size larger dilator. The dilator can also be moved slowly and gently in and out and from side to side.

Topical lidocaine (5%) gel or ointment can facilitate use of the dilator. The patient applies a small amount to the site of vulvar pain (commonly the posterior fourchette of the introitus) with the tip of a cotton swab 15 to 30 minutes before inserting the dilator.

Some vaginal dilators may be obtained directly by the patient (see “Resources” box below), while others require a prescription. Graduated or vibrating dildos can be obtained at retail outlets selling sexual products. A clean finger can also be used for dilation.

Pelvic Floor Therapy

Several modalities offered by specialized physical therapists are used to improve pelvic and vulvovaginal blood flow and control over the pelvic musculature. This may help to alleviate pain with intercourse, particularly in patients with signs of pelvic floor weakness, poor muscle control, or instability. Modalities include pelvic floor exercises and manual therapy techniques (eg, transvaginal trigger point therapy, transvaginal and/or transrectal massage, dry needling of a trigger point).4,58 Surface electrical stimulation of the pelvic floor musculature is also used to decrease pain and muscle spasm.59

Kegel exercises60 (ie, tensing and relaxing the pelvic floor muscles) may help a patient gain control over both contraction and relaxation of the pelvic muscles.60,61 However, if palpation of the pelvic floor reveals tight, inelastic, and dense tissue, assessment and grading of muscle strength may be misleading. For example, the pelvic floor may demonstrate a state of constant contraction (hypertonicity or a “short pelvic floor”).62 Attempts at voluntary contraction of a muscle in this state may be perceived and graded incorrectly as weak.

Traditional Kegel exercises are contraindicated in women with muscle hypertonicity and an inability to relax these muscles. Some practitioners use the term “reverse Kegel” to describe active, bearing-down exercises that increase pelvic floor relaxation. Biofeedback training (surface EMG and/or rehabilitative ultrasound imaging) can be useful to reeducate resting muscle tone of the pelvic floor. Breathing, tactile, verbal, and imagery cues are essential.61,62

Cognitive Behavioral Sex Therapy

This specialized form of psychotherapy helps patients identify cognitive, emotional, and relationship factors that contribute to their pain. Patients learn coping strategies, including relaxation techniques and modification of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors to reduce anxiety, tension, and pain. As pain management improves, the focus shifts to enhancing sexual functioning, including restarting the sexual relationship if sex has been avoided because of pain.63

WHEN AND WHERE TO REFER

Referral is appropriate if the patient’s condition worsens, is unresponsive to therapy, or requires specialized evaluation and treatment. Sex therapy, psychotherapy, or couples counseling may be indicated in more complex cases in which a sexual disorder and significant psychologic and/or relationship problems coexist. Examples may include an unresolved history of sexual abuse, clinical anxiety or depression, sexual phobia or aversion, and general relationship distress. To locate qualified sex therapists, see the “Resources” box.

Physical therapy may be prescribed if the patient demonstrates or reports persistent pain or lack of improvement with initial pelvic floor therapy, an inability to use a dilator on her own, or increased pain or perceived tightness while using a dilator; or if she develops pelvic or perineal pain at rest. To locate specially trained physical therapists, see the “Resources” box.

CONCLUSION

Though commonly seen in primary care, sexual pain disorders in women are often difficult to diagnose and treat because of the confusing array of possible contributory factors. This article presents an overview of possible presentations, causes, diagnostic strategies, and treatment options, integrating evidence-based approaches from the fields of medicine, psychology, and physical therapy.

REFERENCES

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DMS-IV-TR). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000:554-558.

2. Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, et al. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(8): 762-774.

3. Latthe P, Latthe M, Say L, et al. WHO systematic review of prevalence of chronic pelvic pain: a neglected reproductive health morbidity. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:177-183.

4. Simons DG, Travell JG, Simons LS, Cummings BD. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:vol 2, chap 6:110-131.

5. Perry CP. Vulvodynia. In: Howard FM, Perry CP, Carter JE, El-Minawi AM, eds. Pelvic Pain: Diagnosis and Management. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000:204-211.

6. Glazer HI, Jantos M, Hartmann EH, Swencioniswom C. Electromyographic comparisons of the pelvic floor in women with dysesthetic vulvodynia and asymptomatic women. J Reprod Med. 1998;43(11):959-962.

7. Binik YM. The DSM diagnostic criteria for vaginismus. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39(2):278-291.

8. Haefner HK. Report of the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease terminology and classification of vulvodynia. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2007;11(1):48-49.

9. Huffman JW. Dyspareunia of vulvo-vaginal origin: causes and management. Postgrad Med. 1983;73(2):287-296.

10. Krychman ML. Vaginal estrogens for treatment of dyspareunia. J Sex Med. 2010 Nov 22;8:666-674. [Epub ahead of print]

11. Kao A, Binik YM, Kapuscinski A, Khalifé S. Dyspareunia in postmenopausal women: a critical review. Pain Res Manag. 2008;13(3):243-254.

12. Steege JF, Zolnoun DA. Evaluation and treatment of dyspareunia. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113 (5):1124-1136.

13. Lüdicke F, Johannisson E, Helmerhorst FM, et al. Effect of a combined oral contraceptive containing 3 mg of drospirenone and 30 microg of ethinyl estradiol on the human endometrium. Fertil Steril. 2001;76(1):102-107.

14. Strauhal MJ, Frahm J, Morrison P, et al. Vulvar pain: a comprehensive review. J Womens Health Phys Ther. 2007;31(3):6-22.

15. Harlow BL, Stewart EG. A population-based assessment of chronic unexplained vulvar pain: have we underestimated the prevalence of vulvodynia? J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2003;58(2): 82-88.

16. Goetsch MF. Vulvar vestibulitis: prevalence and historic features in a general gynecologic practice population. Am J Obstetr Gynecol. 1991; 164(6 pt 1):1609-1616.

17. Danielsson I, Sjöberg I, Stenlund H, Wikman M. Prevalence and incidence of prolonged and severe dyspareunia in women: results from a population study. Scand J Public Health. 2003;31 (2):113-118.

18. Mac Bride MB, Rhodes DJ, Shuster LT. Vulvovaginal atrophy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(1): 87-94.

19. Barditch-Crovo P, Witter F, Hamzeh F, et al. Quantitation of vaginally administered nonoxynol-9 in premenopausal women. Contraception. 1997;55(4):261-263.

20. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Disorders of the Vulva. ACOG Patient Education Pamphlet AP088. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2007.

21. Ferrero S, Abbamonte LH, Giordano M, et al. Uterine myomas, dyspareunia, and sexual function. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(5):1504-1510.

22. Walid MS, Heaton RL. Dyspareunia: a complex problem requiring a selective approach. Sex Health. 2009;6(3):250-253.

23. Sobghol SS, Alizadeli Charndabee SM. Rate and related factors of dyspareunia in reproductive age women: a cross-sectional study. Int J Impot Res. 2007;19(1):88-94.

24. Ferrero S, Ragni N, Remorgida V. Deep dyspareunia: causes, treatments, and results. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;20(4):394-399.

25. Kim IY, Sadeghi F, Slawin KM. Dyspareunia: an unusual presentation of leiomyoma of the bladder. Rev Urol. 2001;3(3):152-154.

26. Akbulut S, Cakabay B, Sezgin A, Ozmen C. A rare cause of severe dyspareunia: a case report and literature review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009 Apr 26. [Epub ahead of print.]

27. Ferrero S, Esposito F, Abbamonte LH, et al. Quality of sex life in women with endometriosis and deep dyspareunia. Fertil Steril. 2005;83(3): 573-579.

28. Fisher KA. Management of dyspareunia and associated levator ani muscle overactivity. Phys Ther. 2007;87(7):935-941.

29. Bø K, Sherburn M. Evaluation of female pelvic-floor muscle function and strength. Phys Ther. 2005;85(3):269-282.

30. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Female Genital Mutilation and its Management. Green-top Guideline No 53 (May 2009). www.rcog.org.uk/files/rcog-corp/Green Top53FemaleGenitalMutilation.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2011.

31. Payne KA, Binik YM, Amsel R, Khalifé S. When sex hurts, anxiety and fear orient attention towards pain. Eur J Pain. 2005;9(4):427-436.

32. Pukall CF, Binik YM, Khalifé S, et al. Vestibular tactile and pain thresholds in women with vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Pain. 2002;96(1-2):163-175.

33. Meana M, Binik YM, Khalifé S, Cohen D. Psychosocial correlates of pain attributions in women with dyspareunia. Psychosomatics. 1999:40(6): 497-502.

34. Pelvic Pain Assessment Form (2008). International Pelvic Pain Society. www.pelvicpain.org/pdf/History_and_Physical_Form/IPPS-H&PformR-MSW.pdf. Accessed April 11, 2011.

35. Melzack R. The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pain. 1987;30(2):191-197.

36. Basson R. Sexuality and sexual disorders in women. In: Clinical Updates in Women’s Health Care Monograph. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2003;2(2):1-94.

37. Oberg K, Sjögren Fugl-Meyer K. On Swedish women’s distressing sexual dysfunctions: some concomitant conditions and life satisfaction. J Sex Med. 2005;2(2):169-180.

38. Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(2):191-208.

39. Quirk FH, Heiman JR, Rosen RC, et al. Development of a sexual function questionnaire for clinical trials of female sexual dysfunction. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2002;11(3): 277-289.

40. Derogatis LR, Rosen R, Leiblum S, et al. The Female Sexual Distress Scale (FSDS): Initial validation of a standardized scale for assessment of sexually related personal distress in women. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28(4):317-330.

41. van Lankveld JJ, Granot M, Weijmar Schultz WC, et al. Women’s sexual pain disorders. J Sex Med. 2010;7(1 pt 2):615-631.

42. Hathaway JK, Pathak PK, Maney R. Is liquid-based Pap testing affected by water-based lubricant? Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(1):66-70.

43. Bergeron S, Binik YM, Khalifé S, et al. Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: reliability of diagnosis and evaluation of current diagnostic criteria. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(1):45-51.

44. Laycock J, Holmes DM. The place of physiotherapy in the management of pelvic floor dysfunction. Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;5:194-199.

45. Brink CA, Sampselle CM, Wells TJ, et al. A digital test for pelvic muscle strength in older women with urinary incontinence. Nurs Res. 1989;38(4):196-199.

46. Hess R, Austin RM, Dillon S, et al. Vaginal maturation index self-sample collection in mid-life women: acceptability and correlation with physician-collected samples. Menopause. 2008; 15(4 pt 1):726-729.

47. Haefner HK, Collins ME, Davis GD, et al. The vulvodynia guideline. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2005; 9(1):40-51.

48. Albaugh JA, Kellogg-Spadt S. Sensate focus and its role in treating sexual dysfunction. Urol Nurs. 2002;22(6):402-403.

49. Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human Sexual Inadequacy. New York, NY: Ishi Press; 2010: 67-75.

50. Panzer C, Wise S, Fantini G, et al. Impact of oral contraceptives on sex hormone–binding globulin and androgen levels: a retrospective study in women with sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2006;3(1):104-113.

51. Suckling J, Kennedy R, Lethaby A. Local oestrogen for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006; (4):CD001500.

52. Johnston SL, Farrell SA, Bouchard C, et al; SOGC joint Committee–Clinical Practice Gynaecology and Urogynaecology. The detection and management of vaginal atrophy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2004;26(5):503-515.

53. Bergeron S, Khalifé S, Glazer HI, Binik YM. Surgical and behavioral treatments for vestibulodynia: two-and-one-half year follow-up and predictors of outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(1): 159-166.

54. Pukall CF, Smith KB, Chamberlain SM. Provoked vestibulodynia. Womens Health (Lond Engl). 2007;3(5):583-592.

55. van Lankveld JJ, ter Kuile MM, de Groot HE, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for women with lifelong vaginismus: a randomized waiting-list controlled trial of efficacy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(1):168-178.

56. McGuire H, Hawton K. Interventions for vaginismus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(1): CD001760.

57. Calais-Germain B. Analysis of the principal types of breathing. In: Calais-Germain B. Anatomy of Breathing. New York, NY: Eastland Press; 2006:133-158.

58. Carter J. Abdominal wall and pelvic myofascial trigger points. In: Howard FM, Perry P, Carter J, El-Minawi AM. Pelvic Pain: Diagnosis and Management. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000:315-358.

59. Gentilcore-Saulnier E, McLean L, Goldfinger C, et al. Pelvic floor muscle assessment outcomes in women with and without provoked vestibulodynia and the impact of a physical therapy program. J Sex Med. 2010;7(2 pt 2):1003-1022.

60. Kegel AH. Physiologic therapy for urinary stress incontinence. JAMA. 1951;146(10):915-917.

61. Marques A, Stothers L, Macnab A. The status of pelvic floor muscle training for women. Can Urol Assoc J. 2010;4(6):419-424.

62. FitzGerald MP, Kotarinos R. Rehabilitation of the short pelvic floor. I: Background and patient evaluation. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2003;14(4):261-268.

63. Binik Y, Bergeron S, Khalifé S. Dyspareunia and vaginismus: So-called pain disorders. In: Leiblum S, ed. Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2007: 124-156.

Though common, sexual pain disorders in women are often difficult to identify and treat because of the complexity of potential underlying causes. This article will define and describe these conditions in an effort to provide evaluation and treatment strategies for the primary care provider.

SEXUAL PAIN DISORDERS

Dyspareunia is defined as genital pain that may occur before, during, or after vaginal penetration, thus interfering with sexual intercourse and causing marked personal distress and/or interpersonal difficulty.1 Categorization of the condition as lifelong (primary) or acquired (secondary), generalized or situational, may indicate possible underlying causes. Physiological, psychological, or combined factors may be at play. It should be noted that, according to the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DMS-IV-TR),1 painful penetration is not diagnosed as dyspareunia if it is solely the result of lack of lubrication, the physiological effect of a medication, or attributable to the patient’s general medical condition.

Painful intercourse is a prevalent symptom among sexually active women. Between 8% and 21% of women in the general population and 10% of those ages 57 to 85 have been estimated to experience significant dyspareunia.2,3 For some women, sexual pain leads to avoidance of sexual intercourse or contact. Other women remain sexually active despite persistently painful intercourse.

Transient pain during intercourse is predictable in certain situations, such as times of stress, with frequent intercourse (eg, in attempts to conceive), intercourse after a prolonged hiatus from it, or hymenal rupture at coitarche. Dyspareunia, particularly deep dyspareunia, may occur with midcycle intercourse due to normal local inflammation that occurs with ovulation (mittelschmerz).

A second sexual pain disorder experienced by women is vaginismus, which is defined as recurrent or persistent involuntary contraction or spasm of the musculature of the outer third of the vagina (the perineal and levator muscles) that interferes with vaginal penetration, whether associated with sexual intercourse, speculum insertion, or tampon use.1,4-6 Vaginismus may be a cause or a consequence of dyspareunia. This condition is perhaps best described as pelvic floor motor or muscular instability,7 because it can be characterized by:

1) Hypertonicity (reduced ability to relax)

2) Hypocontractility (reduced ability to contract) or

3) Resting muscular instability (as measured by electromyelography [EMG]).8

According to DSM-IV-TR criteria,1 vaginismus also causes marked personal distress or interpersonal difficulty and is not due exclusively to the direct physiological effects of a general medical condition. Vaginismus may occur as a result of psychological factors, such as fear of penetration, or as a conditioned response to pain.

Dyspareunia and Vaginismus: A Clinical Case

Anna is a 30-year-old woman who has been married for three years. She reports that initially, intercourse with her husband was satisfying and pleasurable. She desired sex and was easily aroused and orgasmic. However, when she began to experience a burning pain during intercourse, she tried at first to ignore it, hoping that it would go away on its own. Anticipating pain, she started to avoid sex. When she finally saw her clinician, she was given a diagnosis of candidiasis and responded well to medication.

Although the physical cause of Anna’s dyspareunia was resolved, she continued to be tense when she anticipated an opportunity for sex, associating it with the prior painful experiences. When the couple did attempt vaginal intercourse, penetration was difficult and painful in a different way; it seemed as if the opening to her vagina was closing up, that it was becoming too tight. Anna felt frustrated with herself and her body and worried that her husband would give up on her.

She returned to her clinician, who referred her to a sex therapist. Anna was anxious and skeptical at first but also highly motivated to resolve the pain and resume her previously satisfying sex life. The therapist explained the connection between Anna’s original experience of dyspareunia and the anxiety/avoidance pattern that had developed, causing her pelvic floor muscles to overcontract involuntarily and to make penetration both difficult and uncomfortable. Even though the original physical source of painful intercourse was resolved, Anna had gone on to develop anticipatory anxiety, triggering secondary vaginismus—an automatic, protective response against anticipated pain.

A brief course of cognitive behavioral sex therapy helped Anna to resolve her anxiety, relax her pelvic floor muscles, and gradually return to satisfying sex.

CAUSES OF DYSPAREUNIA

There is a wide and confusing spectrum of causes of primary and secondary dyspareunia. Primary dyspareunia, the less common condition, is associated with imperforate or microperforate hymen, congenital vulvovaginal abnormalities, and acquired vulvovaginal abnormalities resulting from genital surgery, modification, or infundibulation.9

Secondary dyspareunia, or painful intercourse that occurs after a history of pain-free sex, is most often caused by either vaginal atrophy or vulvodynia. Vaginal atrophy, resulting from low circulating estrogen, may cause symptoms of itching, dryness, and irritation; it is experienced by about 40% of postmenopausal women,10 as well as many premenopausal women who take low-dose estrogen oral contraceptives.11-13