User login

The word “endorse” often appears in the medical literature and is heard in oral presentations; psychiatrists use the term to mean that a person is reporting psychiatric symptoms or problems. However, such usage may be a stylistic catachresis—one that has the potential for misinterpretation or misunderstanding.

Finding ‘endorse’ in the psychiatric literature

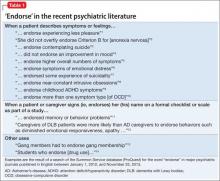

We conducted a literature search to identify instances of “endorse” in scholarly articles published in psychiatric journals between January 1, 2012, and November 25, 2013. Table 11-14 shows examples of typical uses of “endorse” in recent publications.

Even when “endorse” is used as a synonym for “report” or “describe,” use of the word in that context can seem out of place. We could not find any rationale in the medical literature for using “endorse” as a synonym for “report” or “describe.”

The definition of “endorse” in Merriam-Webster15 and Oxford Dictionaries16 includes:

• inscribing or signing a legal document, check, or bill

• approving or recommending an idea, product, or candidate.

We believe that using “endorse” in a psychiatric context could create confusion among medical trainees and professionals who are familiar with the correct meanings of the word.

Survey: Some residents use ‘endorse’ in oral presentations

We asked residents in the Department of Psychiatry at Drexel University College of Medicine to respond to a questionnaire regarding their understanding of the use of “endorse.” Their responses are summarized in Table 2.

What is wrong with using ‘endorse’? Except when “endorse” describes a patient formally affixing her (his) signature to a document for the purpose of (1) certification or (2) giving or showing one’s support for a cause, we think that use of the word in psychiatry is not in keeping with its formal, accepted definition. Furthermore, residents’ responses to our survey suggest that there is the danger of causing confusion in using the word“endorse” when “report” or “describe” is meant.

For example, if a patient “endorses” antisocial behavior, is she stating that she feels justified in exhibiting such behavior? Do students who “endorse” drug use approve of drug use? Another example: Youth who “endorse” gang membership have merely confirmed that they belonged to a gang at some time.

The intended meaning of “endorse” in these examples is probably closer to “admit” or “acknowledge.” The patient replies “yes” when the physician asks if she uses drugs or has had behavior problems; she is not necessarily recommending or approving these behaviors.

Usage is shifting. In the past, “complain” was common medical parlance for a patient’s report of symptoms or other health-related problems. In fact, medical, surgical, and psychiatric evaluations still begin with a “chief complaint” section. It’s possible that, because “complaint” might suggest that the patient is whining, the word fell out of favor in the medical lexicon and was replaced in the scholarly literature by the construction “the patient reports….”

Avoid jargon. Employ accurate terminology

We propose that “endorse,” like “complain,” is a cant of psychiatrists. We recommend that, when describing a patient’s statement or report of symptoms or experiences, practitioners should avoid “endorse” and write or say “report,” “express,” “exhibit,” or similar words. Using accurate terminology and avoiding imprecise or misleading jargon is not only linguistically appropriate but also can help avoid misunderstanding and improve patient care.

Acknowledgment

Diana Winters, Academic Publishing Services, Drexel University College of Medicine, provided editorial assistance in preparing the manuscript of this article and offered comment on the use of medical jargon.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Strauss GP, Gold JM. A new perspective on anhedonia in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(4):364-373.

2. Thomas JJ, Weigel TJ, Lawton RK, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of body image disturbance in a congenitally blind patient with anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(1):16-20.

3. Purcell B, Heisel MJ, Speice J, et al. Family connectedness moderates the association between living alone and suicide ideation in a clinical sample of adults 50 years and older. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(8):717-723.

4. Dakin EK, Areán P. Patient perspectives on the benefits of psychotherapy for late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(2):155-163.

5. Mezuk B, Lohman M, Dumenci, L, et al. Are depression and frailty overlapping syndromes in mid- and late-life? A latent variable analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):560-569.

6. Boindala NS, Tucker P, Trautman RP. “Culture and psychiatry”: a course for second-year psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(1):46-50.

7. Henry A, Kisicki MD, Varley C. Efficacy and safety of antidepressant drug treatment in children and adolescents. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(12):1186-1193.

8. Rodriguez CI, Kegeles LS, Levinson A, et al. A randomized controlled crossover trial of ketamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder (abstract W7). Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;38:S317.

9. Whelan R, Garavan H. Fractionating the impulsivity construct in adolescence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(1):250-251.

10. Rück C, Larsson KJ, Mataix-Cols D. Predictors of medium and long-term outcome following capsulotomy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: one site may not fit all. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;22(6):406-414.

11. Mausbach BT, Chattillion EA, Roepke SK, et al. A comparison of psychosocial outcomes in elderly Alzheimer caregivers and noncaregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(1):5-13.

12. Peavy GM, Salmon DP, Edland SD, et al. Neuropsychiatric features of frontal lobe dysfunction in autopsy-confirmed patients with lewy bodies and “pure” Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):509-519.

13. Coid JW, Ullrich S, Keers R, et al. Gang membership, violence, and psychiatric morbidity. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):985-993.

14. Choi D, Tolova V, Socha E, et al. Substance use and attitudes on professional conduct among medical students: a single-institution study. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(3):191-195.

15. Endorse. Merriam-Webster. http://www.merriam-webster. com/dictionary/endorse. Accessed January 14, 2014.

16. Endorse. Oxford Dictionaries. http://www.oxforddictionaries. com/definition/english/endorse. Accessed January 14, 2014.

The word “endorse” often appears in the medical literature and is heard in oral presentations; psychiatrists use the term to mean that a person is reporting psychiatric symptoms or problems. However, such usage may be a stylistic catachresis—one that has the potential for misinterpretation or misunderstanding.

Finding ‘endorse’ in the psychiatric literature

We conducted a literature search to identify instances of “endorse” in scholarly articles published in psychiatric journals between January 1, 2012, and November 25, 2013. Table 11-14 shows examples of typical uses of “endorse” in recent publications.

Even when “endorse” is used as a synonym for “report” or “describe,” use of the word in that context can seem out of place. We could not find any rationale in the medical literature for using “endorse” as a synonym for “report” or “describe.”

The definition of “endorse” in Merriam-Webster15 and Oxford Dictionaries16 includes:

• inscribing or signing a legal document, check, or bill

• approving or recommending an idea, product, or candidate.

We believe that using “endorse” in a psychiatric context could create confusion among medical trainees and professionals who are familiar with the correct meanings of the word.

Survey: Some residents use ‘endorse’ in oral presentations

We asked residents in the Department of Psychiatry at Drexel University College of Medicine to respond to a questionnaire regarding their understanding of the use of “endorse.” Their responses are summarized in Table 2.

What is wrong with using ‘endorse’? Except when “endorse” describes a patient formally affixing her (his) signature to a document for the purpose of (1) certification or (2) giving or showing one’s support for a cause, we think that use of the word in psychiatry is not in keeping with its formal, accepted definition. Furthermore, residents’ responses to our survey suggest that there is the danger of causing confusion in using the word“endorse” when “report” or “describe” is meant.

For example, if a patient “endorses” antisocial behavior, is she stating that she feels justified in exhibiting such behavior? Do students who “endorse” drug use approve of drug use? Another example: Youth who “endorse” gang membership have merely confirmed that they belonged to a gang at some time.

The intended meaning of “endorse” in these examples is probably closer to “admit” or “acknowledge.” The patient replies “yes” when the physician asks if she uses drugs or has had behavior problems; she is not necessarily recommending or approving these behaviors.

Usage is shifting. In the past, “complain” was common medical parlance for a patient’s report of symptoms or other health-related problems. In fact, medical, surgical, and psychiatric evaluations still begin with a “chief complaint” section. It’s possible that, because “complaint” might suggest that the patient is whining, the word fell out of favor in the medical lexicon and was replaced in the scholarly literature by the construction “the patient reports….”

Avoid jargon. Employ accurate terminology

We propose that “endorse,” like “complain,” is a cant of psychiatrists. We recommend that, when describing a patient’s statement or report of symptoms or experiences, practitioners should avoid “endorse” and write or say “report,” “express,” “exhibit,” or similar words. Using accurate terminology and avoiding imprecise or misleading jargon is not only linguistically appropriate but also can help avoid misunderstanding and improve patient care.

Acknowledgment

Diana Winters, Academic Publishing Services, Drexel University College of Medicine, provided editorial assistance in preparing the manuscript of this article and offered comment on the use of medical jargon.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

The word “endorse” often appears in the medical literature and is heard in oral presentations; psychiatrists use the term to mean that a person is reporting psychiatric symptoms or problems. However, such usage may be a stylistic catachresis—one that has the potential for misinterpretation or misunderstanding.

Finding ‘endorse’ in the psychiatric literature

We conducted a literature search to identify instances of “endorse” in scholarly articles published in psychiatric journals between January 1, 2012, and November 25, 2013. Table 11-14 shows examples of typical uses of “endorse” in recent publications.

Even when “endorse” is used as a synonym for “report” or “describe,” use of the word in that context can seem out of place. We could not find any rationale in the medical literature for using “endorse” as a synonym for “report” or “describe.”

The definition of “endorse” in Merriam-Webster15 and Oxford Dictionaries16 includes:

• inscribing or signing a legal document, check, or bill

• approving or recommending an idea, product, or candidate.

We believe that using “endorse” in a psychiatric context could create confusion among medical trainees and professionals who are familiar with the correct meanings of the word.

Survey: Some residents use ‘endorse’ in oral presentations

We asked residents in the Department of Psychiatry at Drexel University College of Medicine to respond to a questionnaire regarding their understanding of the use of “endorse.” Their responses are summarized in Table 2.

What is wrong with using ‘endorse’? Except when “endorse” describes a patient formally affixing her (his) signature to a document for the purpose of (1) certification or (2) giving or showing one’s support for a cause, we think that use of the word in psychiatry is not in keeping with its formal, accepted definition. Furthermore, residents’ responses to our survey suggest that there is the danger of causing confusion in using the word“endorse” when “report” or “describe” is meant.

For example, if a patient “endorses” antisocial behavior, is she stating that she feels justified in exhibiting such behavior? Do students who “endorse” drug use approve of drug use? Another example: Youth who “endorse” gang membership have merely confirmed that they belonged to a gang at some time.

The intended meaning of “endorse” in these examples is probably closer to “admit” or “acknowledge.” The patient replies “yes” when the physician asks if she uses drugs or has had behavior problems; she is not necessarily recommending or approving these behaviors.

Usage is shifting. In the past, “complain” was common medical parlance for a patient’s report of symptoms or other health-related problems. In fact, medical, surgical, and psychiatric evaluations still begin with a “chief complaint” section. It’s possible that, because “complaint” might suggest that the patient is whining, the word fell out of favor in the medical lexicon and was replaced in the scholarly literature by the construction “the patient reports….”

Avoid jargon. Employ accurate terminology

We propose that “endorse,” like “complain,” is a cant of psychiatrists. We recommend that, when describing a patient’s statement or report of symptoms or experiences, practitioners should avoid “endorse” and write or say “report,” “express,” “exhibit,” or similar words. Using accurate terminology and avoiding imprecise or misleading jargon is not only linguistically appropriate but also can help avoid misunderstanding and improve patient care.

Acknowledgment

Diana Winters, Academic Publishing Services, Drexel University College of Medicine, provided editorial assistance in preparing the manuscript of this article and offered comment on the use of medical jargon.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Strauss GP, Gold JM. A new perspective on anhedonia in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(4):364-373.

2. Thomas JJ, Weigel TJ, Lawton RK, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of body image disturbance in a congenitally blind patient with anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(1):16-20.

3. Purcell B, Heisel MJ, Speice J, et al. Family connectedness moderates the association between living alone and suicide ideation in a clinical sample of adults 50 years and older. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(8):717-723.

4. Dakin EK, Areán P. Patient perspectives on the benefits of psychotherapy for late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(2):155-163.

5. Mezuk B, Lohman M, Dumenci, L, et al. Are depression and frailty overlapping syndromes in mid- and late-life? A latent variable analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):560-569.

6. Boindala NS, Tucker P, Trautman RP. “Culture and psychiatry”: a course for second-year psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(1):46-50.

7. Henry A, Kisicki MD, Varley C. Efficacy and safety of antidepressant drug treatment in children and adolescents. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(12):1186-1193.

8. Rodriguez CI, Kegeles LS, Levinson A, et al. A randomized controlled crossover trial of ketamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder (abstract W7). Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;38:S317.

9. Whelan R, Garavan H. Fractionating the impulsivity construct in adolescence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(1):250-251.

10. Rück C, Larsson KJ, Mataix-Cols D. Predictors of medium and long-term outcome following capsulotomy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: one site may not fit all. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;22(6):406-414.

11. Mausbach BT, Chattillion EA, Roepke SK, et al. A comparison of psychosocial outcomes in elderly Alzheimer caregivers and noncaregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(1):5-13.

12. Peavy GM, Salmon DP, Edland SD, et al. Neuropsychiatric features of frontal lobe dysfunction in autopsy-confirmed patients with lewy bodies and “pure” Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):509-519.

13. Coid JW, Ullrich S, Keers R, et al. Gang membership, violence, and psychiatric morbidity. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):985-993.

14. Choi D, Tolova V, Socha E, et al. Substance use and attitudes on professional conduct among medical students: a single-institution study. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(3):191-195.

15. Endorse. Merriam-Webster. http://www.merriam-webster. com/dictionary/endorse. Accessed January 14, 2014.

16. Endorse. Oxford Dictionaries. http://www.oxforddictionaries. com/definition/english/endorse. Accessed January 14, 2014.

1. Strauss GP, Gold JM. A new perspective on anhedonia in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(4):364-373.

2. Thomas JJ, Weigel TJ, Lawton RK, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of body image disturbance in a congenitally blind patient with anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(1):16-20.

3. Purcell B, Heisel MJ, Speice J, et al. Family connectedness moderates the association between living alone and suicide ideation in a clinical sample of adults 50 years and older. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(8):717-723.

4. Dakin EK, Areán P. Patient perspectives on the benefits of psychotherapy for late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(2):155-163.

5. Mezuk B, Lohman M, Dumenci, L, et al. Are depression and frailty overlapping syndromes in mid- and late-life? A latent variable analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):560-569.

6. Boindala NS, Tucker P, Trautman RP. “Culture and psychiatry”: a course for second-year psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(1):46-50.

7. Henry A, Kisicki MD, Varley C. Efficacy and safety of antidepressant drug treatment in children and adolescents. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(12):1186-1193.

8. Rodriguez CI, Kegeles LS, Levinson A, et al. A randomized controlled crossover trial of ketamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder (abstract W7). Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;38:S317.

9. Whelan R, Garavan H. Fractionating the impulsivity construct in adolescence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(1):250-251.

10. Rück C, Larsson KJ, Mataix-Cols D. Predictors of medium and long-term outcome following capsulotomy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: one site may not fit all. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;22(6):406-414.

11. Mausbach BT, Chattillion EA, Roepke SK, et al. A comparison of psychosocial outcomes in elderly Alzheimer caregivers and noncaregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(1):5-13.

12. Peavy GM, Salmon DP, Edland SD, et al. Neuropsychiatric features of frontal lobe dysfunction in autopsy-confirmed patients with lewy bodies and “pure” Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):509-519.

13. Coid JW, Ullrich S, Keers R, et al. Gang membership, violence, and psychiatric morbidity. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):985-993.

14. Choi D, Tolova V, Socha E, et al. Substance use and attitudes on professional conduct among medical students: a single-institution study. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(3):191-195.

15. Endorse. Merriam-Webster. http://www.merriam-webster. com/dictionary/endorse. Accessed January 14, 2014.

16. Endorse. Oxford Dictionaries. http://www.oxforddictionaries. com/definition/english/endorse. Accessed January 14, 2014.