User login

DENVER – Obstructive sleep apnea diagnosed later in life is associated with an increased likelihood of subsequent Alzheimer’s disease, Dr. Omonigho Bubu reported at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

He presented a retrospective cohort study in which a dose-reponse relationship was apparent. The more severe an individual’s obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) as reflected in a higher apnea-hypopnea index on polysomnography, the greater the risk of later being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, compared with matched controls during up to 13 years of follow-up.

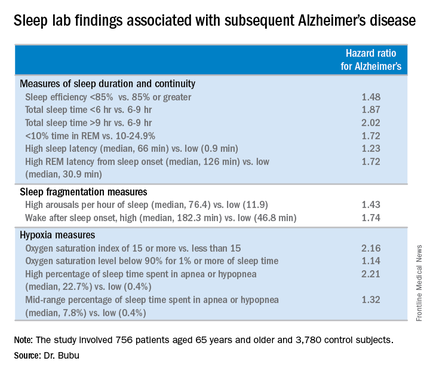

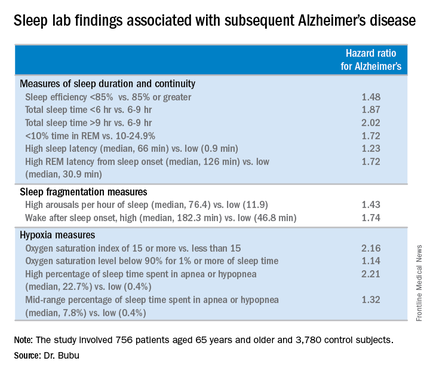

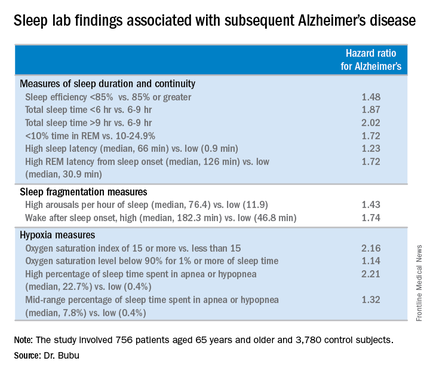

The study also identified several possible contributing factors for the observed OSA/Alzheimer’s relationship. Those OSA patients with more severe sleep fragmentation, nocturnal hypoxia, and abnormal sleep duration were significantly more likely to subsequently develop Alzheimer’s disease than were OSA patients with less severely disrupted sleep measures, added Dr. Bubu of the University of South Florida, Tampa.

The study included 756 patients aged 65 years and older with no history of cognitive decline when diagnosed with OSA by polysomnography at Tampa General Hospital during 2001-2005. They were matched by age, race, sex, body mass index, and zip code to two control groups totaling 3,780 subjects. The controls, drawn from outpatient medical clinics at the hospital, had a variety of medical problems but no sleep disorders or cognitive impairment.

During a mean 10.5-year follow-up period, 513 subjects were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, according to Medicare data. In a Cox proportional hazards analysis adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, and education level, OSA was independently associated with a 2.2-fold increased risk. Further adjustment for alcohol intake, smoking, use of sleep medications, and chronic medical conditions didn’t substantially change the results.

However, the investigators were not able to control for apolipoprotein E (APOE)–epsilon 4 allele status, which is a known risk factor for both OSA and Alzheimer’s disease, so it makes one wonder whether the association is “all related to APOE,” said Dr. Richard J. Caselli, professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., when asked to comment on the study.

Time to onset of Alzheimer’s disease was shorter in the OSA patients: The mean time to diagnosis was 60.8 months after diagnosis of OSA, compared with 73 and 78 months in members of the two control groups who developed the dementia.

When the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease was stratified according to baseline OSA severity, a dose-response effect was seen. Mild OSA, defined as 5-14 apnea-hypopnea events per hour of sleep, was associated with a 1.67-fold greater risk than in controls. The moderate OSA group, who had 15-29 events per hour, had a 1.81-fold increased risk. Patients with severe OSA, with 30 or more events per hour, had a 2.63-fold increased risk.

Gender, race, and education modified the relationship between OSA and Alzheimer’s disease, Dr. Bubu said. Women with OSA had a 2.28-fold greater risk of later developing the disease, compared with controls; men had a 1.42-fold increased risk. African-Americans with OSA were at 2.56-fold greater risk than were controls, while Hispanics with OSA were at 1.8-fold increased risk and non-Hispanic whites were at 1.87-fold increased risk. OSA patients with a high school education or less were at 2.73 times greater risk of Alzheimer’s disease than were controls, those with at least some college or technical school were at 1.82-fold risk, and OSA patients who’d been to graduate school had a 1.31-fold increased risk.

“Our results definitely show that OSA precedes the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. But we cannot say that’s causation. That will be left to future research examining the potential mechanisms we’ve identified,” Dr. Bubu said in an interview.

A key missing link in establishing a causal relationship is the lack of data on how many of the older patients diagnosed with OSA accepted treatment for the condition, and what their response rates were. In other words, it remains to be seen whether OSA occurring later in life is a modifiable risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease as opposed to an early expression of the dementing disease process whereby treatment of the sleep disorder doesn’t affect the progressive cognitive decline.

Both short sleep duration of less than 6 hours as well as a mean total sleep time greater than 9 hours in patients with OSA were associated with significantly increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease, compared with a sleep time of 6-9 hours. Patients with a high sleep-onset latency in the sleep lab, a high REM latency from sleep onset, a low percentage of time spent in REM, an oxygen saturation level of less than 90% for at least 1% of sleep time, and/or a high number of arousals per hour of sleep were also at increased risk of subsequent Alzheimer’s disease.

The study was supported by the Byrd Alzheimer’s Institute. Dr. Bubu reported having no financial conflicts.

DENVER – Obstructive sleep apnea diagnosed later in life is associated with an increased likelihood of subsequent Alzheimer’s disease, Dr. Omonigho Bubu reported at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

He presented a retrospective cohort study in which a dose-reponse relationship was apparent. The more severe an individual’s obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) as reflected in a higher apnea-hypopnea index on polysomnography, the greater the risk of later being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, compared with matched controls during up to 13 years of follow-up.

The study also identified several possible contributing factors for the observed OSA/Alzheimer’s relationship. Those OSA patients with more severe sleep fragmentation, nocturnal hypoxia, and abnormal sleep duration were significantly more likely to subsequently develop Alzheimer’s disease than were OSA patients with less severely disrupted sleep measures, added Dr. Bubu of the University of South Florida, Tampa.

The study included 756 patients aged 65 years and older with no history of cognitive decline when diagnosed with OSA by polysomnography at Tampa General Hospital during 2001-2005. They were matched by age, race, sex, body mass index, and zip code to two control groups totaling 3,780 subjects. The controls, drawn from outpatient medical clinics at the hospital, had a variety of medical problems but no sleep disorders or cognitive impairment.

During a mean 10.5-year follow-up period, 513 subjects were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, according to Medicare data. In a Cox proportional hazards analysis adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, and education level, OSA was independently associated with a 2.2-fold increased risk. Further adjustment for alcohol intake, smoking, use of sleep medications, and chronic medical conditions didn’t substantially change the results.

However, the investigators were not able to control for apolipoprotein E (APOE)–epsilon 4 allele status, which is a known risk factor for both OSA and Alzheimer’s disease, so it makes one wonder whether the association is “all related to APOE,” said Dr. Richard J. Caselli, professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., when asked to comment on the study.

Time to onset of Alzheimer’s disease was shorter in the OSA patients: The mean time to diagnosis was 60.8 months after diagnosis of OSA, compared with 73 and 78 months in members of the two control groups who developed the dementia.

When the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease was stratified according to baseline OSA severity, a dose-response effect was seen. Mild OSA, defined as 5-14 apnea-hypopnea events per hour of sleep, was associated with a 1.67-fold greater risk than in controls. The moderate OSA group, who had 15-29 events per hour, had a 1.81-fold increased risk. Patients with severe OSA, with 30 or more events per hour, had a 2.63-fold increased risk.

Gender, race, and education modified the relationship between OSA and Alzheimer’s disease, Dr. Bubu said. Women with OSA had a 2.28-fold greater risk of later developing the disease, compared with controls; men had a 1.42-fold increased risk. African-Americans with OSA were at 2.56-fold greater risk than were controls, while Hispanics with OSA were at 1.8-fold increased risk and non-Hispanic whites were at 1.87-fold increased risk. OSA patients with a high school education or less were at 2.73 times greater risk of Alzheimer’s disease than were controls, those with at least some college or technical school were at 1.82-fold risk, and OSA patients who’d been to graduate school had a 1.31-fold increased risk.

“Our results definitely show that OSA precedes the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. But we cannot say that’s causation. That will be left to future research examining the potential mechanisms we’ve identified,” Dr. Bubu said in an interview.

A key missing link in establishing a causal relationship is the lack of data on how many of the older patients diagnosed with OSA accepted treatment for the condition, and what their response rates were. In other words, it remains to be seen whether OSA occurring later in life is a modifiable risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease as opposed to an early expression of the dementing disease process whereby treatment of the sleep disorder doesn’t affect the progressive cognitive decline.

Both short sleep duration of less than 6 hours as well as a mean total sleep time greater than 9 hours in patients with OSA were associated with significantly increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease, compared with a sleep time of 6-9 hours. Patients with a high sleep-onset latency in the sleep lab, a high REM latency from sleep onset, a low percentage of time spent in REM, an oxygen saturation level of less than 90% for at least 1% of sleep time, and/or a high number of arousals per hour of sleep were also at increased risk of subsequent Alzheimer’s disease.

The study was supported by the Byrd Alzheimer’s Institute. Dr. Bubu reported having no financial conflicts.

DENVER – Obstructive sleep apnea diagnosed later in life is associated with an increased likelihood of subsequent Alzheimer’s disease, Dr. Omonigho Bubu reported at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

He presented a retrospective cohort study in which a dose-reponse relationship was apparent. The more severe an individual’s obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) as reflected in a higher apnea-hypopnea index on polysomnography, the greater the risk of later being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, compared with matched controls during up to 13 years of follow-up.

The study also identified several possible contributing factors for the observed OSA/Alzheimer’s relationship. Those OSA patients with more severe sleep fragmentation, nocturnal hypoxia, and abnormal sleep duration were significantly more likely to subsequently develop Alzheimer’s disease than were OSA patients with less severely disrupted sleep measures, added Dr. Bubu of the University of South Florida, Tampa.

The study included 756 patients aged 65 years and older with no history of cognitive decline when diagnosed with OSA by polysomnography at Tampa General Hospital during 2001-2005. They were matched by age, race, sex, body mass index, and zip code to two control groups totaling 3,780 subjects. The controls, drawn from outpatient medical clinics at the hospital, had a variety of medical problems but no sleep disorders or cognitive impairment.

During a mean 10.5-year follow-up period, 513 subjects were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, according to Medicare data. In a Cox proportional hazards analysis adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, and education level, OSA was independently associated with a 2.2-fold increased risk. Further adjustment for alcohol intake, smoking, use of sleep medications, and chronic medical conditions didn’t substantially change the results.

However, the investigators were not able to control for apolipoprotein E (APOE)–epsilon 4 allele status, which is a known risk factor for both OSA and Alzheimer’s disease, so it makes one wonder whether the association is “all related to APOE,” said Dr. Richard J. Caselli, professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., when asked to comment on the study.

Time to onset of Alzheimer’s disease was shorter in the OSA patients: The mean time to diagnosis was 60.8 months after diagnosis of OSA, compared with 73 and 78 months in members of the two control groups who developed the dementia.

When the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease was stratified according to baseline OSA severity, a dose-response effect was seen. Mild OSA, defined as 5-14 apnea-hypopnea events per hour of sleep, was associated with a 1.67-fold greater risk than in controls. The moderate OSA group, who had 15-29 events per hour, had a 1.81-fold increased risk. Patients with severe OSA, with 30 or more events per hour, had a 2.63-fold increased risk.

Gender, race, and education modified the relationship between OSA and Alzheimer’s disease, Dr. Bubu said. Women with OSA had a 2.28-fold greater risk of later developing the disease, compared with controls; men had a 1.42-fold increased risk. African-Americans with OSA were at 2.56-fold greater risk than were controls, while Hispanics with OSA were at 1.8-fold increased risk and non-Hispanic whites were at 1.87-fold increased risk. OSA patients with a high school education or less were at 2.73 times greater risk of Alzheimer’s disease than were controls, those with at least some college or technical school were at 1.82-fold risk, and OSA patients who’d been to graduate school had a 1.31-fold increased risk.

“Our results definitely show that OSA precedes the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. But we cannot say that’s causation. That will be left to future research examining the potential mechanisms we’ve identified,” Dr. Bubu said in an interview.

A key missing link in establishing a causal relationship is the lack of data on how many of the older patients diagnosed with OSA accepted treatment for the condition, and what their response rates were. In other words, it remains to be seen whether OSA occurring later in life is a modifiable risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease as opposed to an early expression of the dementing disease process whereby treatment of the sleep disorder doesn’t affect the progressive cognitive decline.

Both short sleep duration of less than 6 hours as well as a mean total sleep time greater than 9 hours in patients with OSA were associated with significantly increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease, compared with a sleep time of 6-9 hours. Patients with a high sleep-onset latency in the sleep lab, a high REM latency from sleep onset, a low percentage of time spent in REM, an oxygen saturation level of less than 90% for at least 1% of sleep time, and/or a high number of arousals per hour of sleep were also at increased risk of subsequent Alzheimer’s disease.

The study was supported by the Byrd Alzheimer’s Institute. Dr. Bubu reported having no financial conflicts.

AT SLEEP 2016