User login

Investigators studied 3-year incidence rates of psychiatric disorders in almost 3,000 patients experiencing an MDE. Results showed that having a history of difficulty falling asleep, early morning awakening, and hypersomnia increased risk for incident psychiatric disorders.

“The findings of this study suggest the potential value of including insomnia and hypersomnia in clinical assessments of all psychiatric disorders,” write the investigators, led by Bénédicte Barbotin, MD, Département de Psychiatrie et d’Addictologie, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, Hôpital Bichat-Claude Bernard, France.

“Insomnia and hypersomnia symptoms may be prodromal transdiagnostic biomarkers and easily modifiable therapeutic targets for the prevention of psychiatric disorders,” they add.

The findings were published online recently in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Bidirectional association

The researchers note that sleep disturbance is “one of the most common symptoms” associated with major depressive disorder (MDD) and may be “both a consequence and a cause.”

Moreover, improving sleep disturbances for patients with an MDE “tends to improve depressive symptom and outcomes,” they add.

Although the possibility of a bidirectional association between MDEs and sleep disturbances “offers a new perspective that sleep complaints might be a predictive prodromal symptom,” the association of sleep complaints with the subsequent development of other psychiatric disorders in MDEs “remains poorly documented,” the investigators write.

The observation that sleep complaints are associated with psychiatric complications and adverse outcomes, such as suicidality and substance overdose, suggests that longitudinal studies “may help to better understand these relationships.”

To investigate these issues, the researchers examined three sleep complaints among patients with MDE: trouble falling asleep, early morning awakening, and hypersomnia. They adjusted for an array of variables, including antisocial personality disorders, use of sedatives or tranquilizers, sociodemographic characteristics, MDE severity, poverty, obesity, educational level, and stressful life events.

They also used a “bifactor latent variable approach” to “disentangle” a number of effects, including those shared by all psychiatric disorders; those specific to dimensions of psychopathology, such as internalizing dimension; and those specific to individual psychiatric disorders, such as dysthymia.

“To our knowledge, this is the most extensive prospective assessment [ever conducted] of associations between sleep complaints and incident psychiatric disorders,” the investigators write.

They drew on data from Waves 1 and 2 of the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, a large nationally representative survey conducted in 2001-2002 (Wave 1) and 2004-2005 (Wave 2) by the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse.

The analysis included 2,864 participants who experienced MDE in the year prior to Wave 1 and who completed interviews at both waves.

Researchers assessed past-year DSM-IV Axis I disorders and baseline sleep complaints at Wave 1, as well as incident DSM-IV Axis I disorders between the two waves – including substance use, mood, and anxiety disorders.

Screening needed?

Results showed a wide range of incidence rates for psychiatric disorders between Wave 1 and Wave 2, ranging from 2.7% for cannabis use to 8.2% for generalized anxiety disorder.

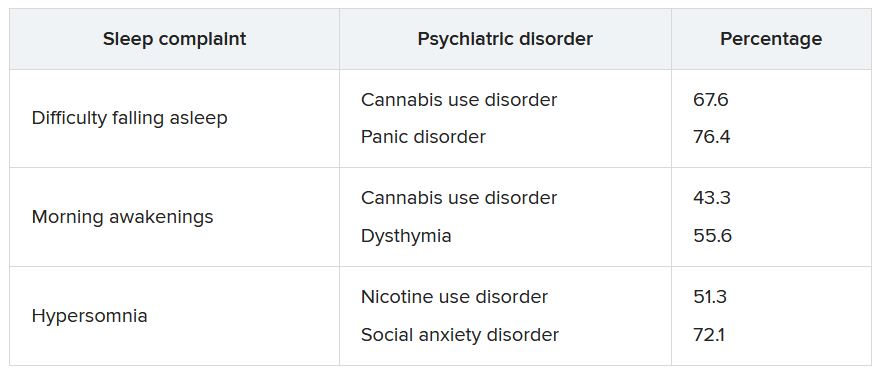

The lifetime prevalence of sleep complaints was higher among participants who developed a psychiatric disorder between the two waves than among those who did not have sleep complaints. The range (from lowest to highest percentage) is shown in the accompanying table.

A higher number of sleep complaints was also associated with higher percentages of psychiatric disorders.

Hypersomnia, in particular, significantly increased the odds of having another psychiatric disorder. For patients with MDD who reported hypersomnia, the mean number of sleep disorders was significantly higher than for patients without hypersomnia (2.08 vs. 1.32; P < .001).

“This explains why hypersomnia appears more strongly associated with the incidence of psychiatric disorders,” the investigators write.

After adjusting for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and antisocial personality disorder, the effects shared across all sleep complaints were “significantly associated with the incident general psychopathology factor, representing mechanisms that may lead to incidence of all psychiatric disorder in the model,” they add.

The researchers note that insomnia and hypersomnia can impair cognitive function, decision-making, problem-solving, and emotion processing networks, thereby increasing the onset of psychiatric disorders in vulnerable individuals.

Shared biological determinants, such as monoamine neurotransmitters that play a major role in depression, anxiety, substance use disorders, and the regulation of sleep stages, may also underlie both sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders, they speculate.

“These results suggest the importance of systematically assessing insomnia and hypersomnia when evaluating psychiatric disorders and considering these symptoms as nonspecific prodromal or at-risk symptoms, also shared with suicidal behaviors,” the investigators write.

“In addition, since most individuals who developed a psychiatric disorder had at least one sleep complaint, all psychiatric disorders should be carefully screened among individuals with sleep complaints,” they add.

Transdiagnostic phenomenon

In a comment, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Toronto, and head of the Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit, noted that the study replicates previous observations that a bidirectional relationship exists between sleep disturbances and mental disorders and that there “seems to be a relationship between sleep disturbance and suicidality that is bidirectional.”

He added that he appreciated the fact that the investigators “took this knowledge one step further; and what they are saying is that within the syndrome of depression, it is the sleep disturbance that is predicting future problems.”

Dr. McIntyre, who is also chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation in Toronto, was not involved with the study.

The data suggest that, “conceptually, sleep disturbance is a transdiagnostic phenomenon that may also be the nexus when multiple comorbid mental disorders occur,” he said.

“If this is the case, clinically, there is an opportunity here to prevent incident mental disorders in persons with depression and sleep disturbance, prioritizing sleep management in any patient with a mood disorder,” Dr. McIntyre added.

He noted that “the testable hypothesis” is how this is occurring mechanistically.

“I would conjecture that it could be inflammation and/or insulin resistance that is part of sleep disturbance that could predispose and portend other mental illnesses – and likely other medical conditions too, such as obesity and diabetes,” he said.

The study received no specific funding from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The investigators’ relevant financial relationships are listed in the original article. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Milken Institute; has received speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes,Neumora Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sage, Biogen, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, Viatris, AbbVie, and Atai Life Sciences; and is a CEO of Braxia Scientific Corp.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators studied 3-year incidence rates of psychiatric disorders in almost 3,000 patients experiencing an MDE. Results showed that having a history of difficulty falling asleep, early morning awakening, and hypersomnia increased risk for incident psychiatric disorders.

“The findings of this study suggest the potential value of including insomnia and hypersomnia in clinical assessments of all psychiatric disorders,” write the investigators, led by Bénédicte Barbotin, MD, Département de Psychiatrie et d’Addictologie, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, Hôpital Bichat-Claude Bernard, France.

“Insomnia and hypersomnia symptoms may be prodromal transdiagnostic biomarkers and easily modifiable therapeutic targets for the prevention of psychiatric disorders,” they add.

The findings were published online recently in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Bidirectional association

The researchers note that sleep disturbance is “one of the most common symptoms” associated with major depressive disorder (MDD) and may be “both a consequence and a cause.”

Moreover, improving sleep disturbances for patients with an MDE “tends to improve depressive symptom and outcomes,” they add.

Although the possibility of a bidirectional association between MDEs and sleep disturbances “offers a new perspective that sleep complaints might be a predictive prodromal symptom,” the association of sleep complaints with the subsequent development of other psychiatric disorders in MDEs “remains poorly documented,” the investigators write.

The observation that sleep complaints are associated with psychiatric complications and adverse outcomes, such as suicidality and substance overdose, suggests that longitudinal studies “may help to better understand these relationships.”

To investigate these issues, the researchers examined three sleep complaints among patients with MDE: trouble falling asleep, early morning awakening, and hypersomnia. They adjusted for an array of variables, including antisocial personality disorders, use of sedatives or tranquilizers, sociodemographic characteristics, MDE severity, poverty, obesity, educational level, and stressful life events.

They also used a “bifactor latent variable approach” to “disentangle” a number of effects, including those shared by all psychiatric disorders; those specific to dimensions of psychopathology, such as internalizing dimension; and those specific to individual psychiatric disorders, such as dysthymia.

“To our knowledge, this is the most extensive prospective assessment [ever conducted] of associations between sleep complaints and incident psychiatric disorders,” the investigators write.

They drew on data from Waves 1 and 2 of the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, a large nationally representative survey conducted in 2001-2002 (Wave 1) and 2004-2005 (Wave 2) by the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse.

The analysis included 2,864 participants who experienced MDE in the year prior to Wave 1 and who completed interviews at both waves.

Researchers assessed past-year DSM-IV Axis I disorders and baseline sleep complaints at Wave 1, as well as incident DSM-IV Axis I disorders between the two waves – including substance use, mood, and anxiety disorders.

Screening needed?

Results showed a wide range of incidence rates for psychiatric disorders between Wave 1 and Wave 2, ranging from 2.7% for cannabis use to 8.2% for generalized anxiety disorder.

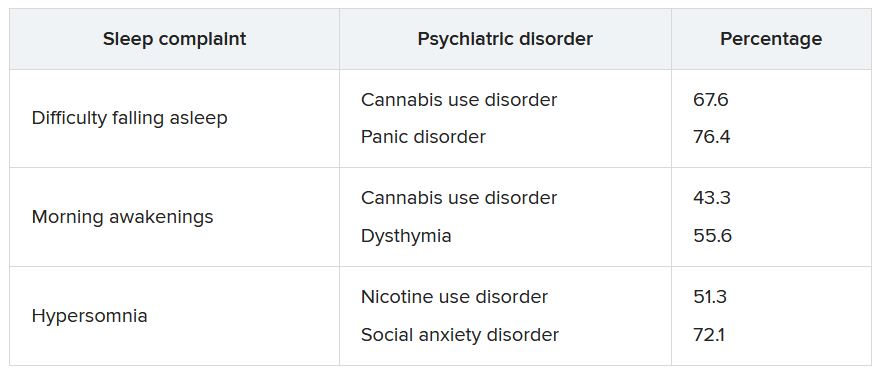

The lifetime prevalence of sleep complaints was higher among participants who developed a psychiatric disorder between the two waves than among those who did not have sleep complaints. The range (from lowest to highest percentage) is shown in the accompanying table.

A higher number of sleep complaints was also associated with higher percentages of psychiatric disorders.

Hypersomnia, in particular, significantly increased the odds of having another psychiatric disorder. For patients with MDD who reported hypersomnia, the mean number of sleep disorders was significantly higher than for patients without hypersomnia (2.08 vs. 1.32; P < .001).

“This explains why hypersomnia appears more strongly associated with the incidence of psychiatric disorders,” the investigators write.

After adjusting for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and antisocial personality disorder, the effects shared across all sleep complaints were “significantly associated with the incident general psychopathology factor, representing mechanisms that may lead to incidence of all psychiatric disorder in the model,” they add.

The researchers note that insomnia and hypersomnia can impair cognitive function, decision-making, problem-solving, and emotion processing networks, thereby increasing the onset of psychiatric disorders in vulnerable individuals.

Shared biological determinants, such as monoamine neurotransmitters that play a major role in depression, anxiety, substance use disorders, and the regulation of sleep stages, may also underlie both sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders, they speculate.

“These results suggest the importance of systematically assessing insomnia and hypersomnia when evaluating psychiatric disorders and considering these symptoms as nonspecific prodromal or at-risk symptoms, also shared with suicidal behaviors,” the investigators write.

“In addition, since most individuals who developed a psychiatric disorder had at least one sleep complaint, all psychiatric disorders should be carefully screened among individuals with sleep complaints,” they add.

Transdiagnostic phenomenon

In a comment, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Toronto, and head of the Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit, noted that the study replicates previous observations that a bidirectional relationship exists between sleep disturbances and mental disorders and that there “seems to be a relationship between sleep disturbance and suicidality that is bidirectional.”

He added that he appreciated the fact that the investigators “took this knowledge one step further; and what they are saying is that within the syndrome of depression, it is the sleep disturbance that is predicting future problems.”

Dr. McIntyre, who is also chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation in Toronto, was not involved with the study.

The data suggest that, “conceptually, sleep disturbance is a transdiagnostic phenomenon that may also be the nexus when multiple comorbid mental disorders occur,” he said.

“If this is the case, clinically, there is an opportunity here to prevent incident mental disorders in persons with depression and sleep disturbance, prioritizing sleep management in any patient with a mood disorder,” Dr. McIntyre added.

He noted that “the testable hypothesis” is how this is occurring mechanistically.

“I would conjecture that it could be inflammation and/or insulin resistance that is part of sleep disturbance that could predispose and portend other mental illnesses – and likely other medical conditions too, such as obesity and diabetes,” he said.

The study received no specific funding from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The investigators’ relevant financial relationships are listed in the original article. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Milken Institute; has received speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes,Neumora Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sage, Biogen, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, Viatris, AbbVie, and Atai Life Sciences; and is a CEO of Braxia Scientific Corp.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators studied 3-year incidence rates of psychiatric disorders in almost 3,000 patients experiencing an MDE. Results showed that having a history of difficulty falling asleep, early morning awakening, and hypersomnia increased risk for incident psychiatric disorders.

“The findings of this study suggest the potential value of including insomnia and hypersomnia in clinical assessments of all psychiatric disorders,” write the investigators, led by Bénédicte Barbotin, MD, Département de Psychiatrie et d’Addictologie, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, Hôpital Bichat-Claude Bernard, France.

“Insomnia and hypersomnia symptoms may be prodromal transdiagnostic biomarkers and easily modifiable therapeutic targets for the prevention of psychiatric disorders,” they add.

The findings were published online recently in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Bidirectional association

The researchers note that sleep disturbance is “one of the most common symptoms” associated with major depressive disorder (MDD) and may be “both a consequence and a cause.”

Moreover, improving sleep disturbances for patients with an MDE “tends to improve depressive symptom and outcomes,” they add.

Although the possibility of a bidirectional association between MDEs and sleep disturbances “offers a new perspective that sleep complaints might be a predictive prodromal symptom,” the association of sleep complaints with the subsequent development of other psychiatric disorders in MDEs “remains poorly documented,” the investigators write.

The observation that sleep complaints are associated with psychiatric complications and adverse outcomes, such as suicidality and substance overdose, suggests that longitudinal studies “may help to better understand these relationships.”

To investigate these issues, the researchers examined three sleep complaints among patients with MDE: trouble falling asleep, early morning awakening, and hypersomnia. They adjusted for an array of variables, including antisocial personality disorders, use of sedatives or tranquilizers, sociodemographic characteristics, MDE severity, poverty, obesity, educational level, and stressful life events.

They also used a “bifactor latent variable approach” to “disentangle” a number of effects, including those shared by all psychiatric disorders; those specific to dimensions of psychopathology, such as internalizing dimension; and those specific to individual psychiatric disorders, such as dysthymia.

“To our knowledge, this is the most extensive prospective assessment [ever conducted] of associations between sleep complaints and incident psychiatric disorders,” the investigators write.

They drew on data from Waves 1 and 2 of the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, a large nationally representative survey conducted in 2001-2002 (Wave 1) and 2004-2005 (Wave 2) by the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse.

The analysis included 2,864 participants who experienced MDE in the year prior to Wave 1 and who completed interviews at both waves.

Researchers assessed past-year DSM-IV Axis I disorders and baseline sleep complaints at Wave 1, as well as incident DSM-IV Axis I disorders between the two waves – including substance use, mood, and anxiety disorders.

Screening needed?

Results showed a wide range of incidence rates for psychiatric disorders between Wave 1 and Wave 2, ranging from 2.7% for cannabis use to 8.2% for generalized anxiety disorder.

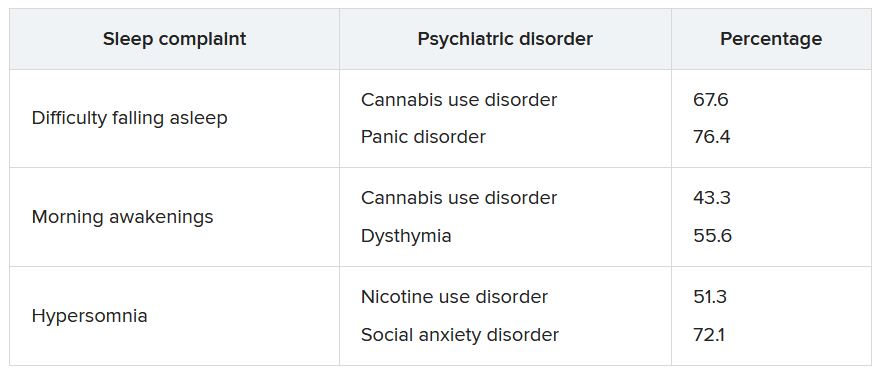

The lifetime prevalence of sleep complaints was higher among participants who developed a psychiatric disorder between the two waves than among those who did not have sleep complaints. The range (from lowest to highest percentage) is shown in the accompanying table.

A higher number of sleep complaints was also associated with higher percentages of psychiatric disorders.

Hypersomnia, in particular, significantly increased the odds of having another psychiatric disorder. For patients with MDD who reported hypersomnia, the mean number of sleep disorders was significantly higher than for patients without hypersomnia (2.08 vs. 1.32; P < .001).

“This explains why hypersomnia appears more strongly associated with the incidence of psychiatric disorders,” the investigators write.

After adjusting for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and antisocial personality disorder, the effects shared across all sleep complaints were “significantly associated with the incident general psychopathology factor, representing mechanisms that may lead to incidence of all psychiatric disorder in the model,” they add.

The researchers note that insomnia and hypersomnia can impair cognitive function, decision-making, problem-solving, and emotion processing networks, thereby increasing the onset of psychiatric disorders in vulnerable individuals.

Shared biological determinants, such as monoamine neurotransmitters that play a major role in depression, anxiety, substance use disorders, and the regulation of sleep stages, may also underlie both sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders, they speculate.

“These results suggest the importance of systematically assessing insomnia and hypersomnia when evaluating psychiatric disorders and considering these symptoms as nonspecific prodromal or at-risk symptoms, also shared with suicidal behaviors,” the investigators write.

“In addition, since most individuals who developed a psychiatric disorder had at least one sleep complaint, all psychiatric disorders should be carefully screened among individuals with sleep complaints,” they add.

Transdiagnostic phenomenon

In a comment, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Toronto, and head of the Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit, noted that the study replicates previous observations that a bidirectional relationship exists between sleep disturbances and mental disorders and that there “seems to be a relationship between sleep disturbance and suicidality that is bidirectional.”

He added that he appreciated the fact that the investigators “took this knowledge one step further; and what they are saying is that within the syndrome of depression, it is the sleep disturbance that is predicting future problems.”

Dr. McIntyre, who is also chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation in Toronto, was not involved with the study.

The data suggest that, “conceptually, sleep disturbance is a transdiagnostic phenomenon that may also be the nexus when multiple comorbid mental disorders occur,” he said.

“If this is the case, clinically, there is an opportunity here to prevent incident mental disorders in persons with depression and sleep disturbance, prioritizing sleep management in any patient with a mood disorder,” Dr. McIntyre added.

He noted that “the testable hypothesis” is how this is occurring mechanistically.

“I would conjecture that it could be inflammation and/or insulin resistance that is part of sleep disturbance that could predispose and portend other mental illnesses – and likely other medical conditions too, such as obesity and diabetes,” he said.

The study received no specific funding from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The investigators’ relevant financial relationships are listed in the original article. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Milken Institute; has received speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes,Neumora Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sage, Biogen, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, Viatris, AbbVie, and Atai Life Sciences; and is a CEO of Braxia Scientific Corp.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY