User login

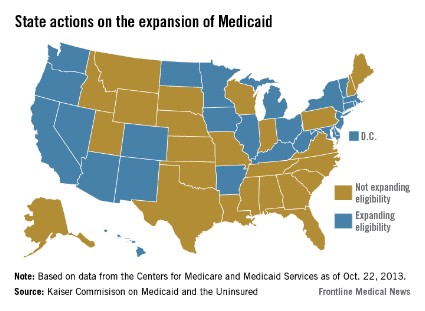

When the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Affordable Care Act in 2012, it also ruled that states could choose whether to substantially expand their Medicaid programs. That decision has created a split across the country, with about half of the states choosing to take federal dollars to expand their programs and the others opting out.

There’s no deadline on Medicaid expansion, so those states that have opted out so far can always choose to expand at a later date.

Here’s a look at two bellwether states: California, which has accepted federal money to expand its Medi-Cal program, and Texas, which has opted out of the expansion.

California Gov. Jerry Brown (D), a strong supporter of the ACA, announced that his state would expand Medicaid to include low-income individuals up to 138% of the federal poverty level starting on Jan. 1, 2014. All of the new enrollees – likely 1 million Californians – will be added to the state’s growing Medicaid managed care program.

Conversely, Texas Gov. Rick Perry (R) deemed Medicaid expansion "a misguided, and ultimately doomed, attempt to mask the shortcomings of Obamacare."

California: Pay cuts complicate expansion

Physicians in California are bracing for a significant Medicaid pay cut at the same time as about a million residents are set to join the program.

The pending cuts are just one part of a complex health care picture in California, where experts are far from certain about what the expansion of Medi-Cal will mean for physicians and patients.

"I think we’re going to have a real problem in California with all the new Medi-Cal patients," said Dr. Mark Dressner, who works at a federally qualified health center in Long Beach and is the president of the California Academy of Family Physicians. "Who is going to see them when there’s going to be so many other people in the system?"

The Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that between 990,000 and 1.4 million individuals, mostly single adults, will enter Medi-Cal by 2019 because of the ACA-permitted expansion. Currently, about 8.5 million residents are enrolled. Newly eligible individuals will be enrolled in the program’s managed care health plans.

These new patients could have a hard time finding a doctor. Medi-Cal is one of the lowest payers in the nation, paying between $18 and $24 for an office visit, according to the California Medical Association.

That’s about to be compounded by a pay cut approved by the state and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in 2011. Physicians tried unsuccessfully to fight the cut in court. Now the state is implementing it retroactively, which means that Medi-Cal payments could be cut 15%-20% over the next few years.

"It really undermines efforts to successfully implement the Affordable Care Act in California," said Lisa Folberg, vice president of medical and regulatory policy at the California Medical Association.

There are broad exceptions to the cut. It does not apply to most primary care services in either managed care plans or fee-for-service Medi-Cal, or to specialty services provided through managed care plans, Ms. Folberg said. And some managed care companies have announced that they will use their discretion in setting payment rates to shield their contracted physicians from the cuts.

"Unfortunately, that doesn’t help the cancer patient on Medi-Cal in Bakersfield who has fee-for-service Medi-Cal and can’t find an oncologist," Ms. Folberg said.

Dr. Darin Latimore, president of the California chapter of the American College of Physicians, said large health systems likely will be able to work around the cuts, using group visits and physician extenders. But small physician practices in rural areas aren’t equipped to make those changes, he said.

"They are not in a position to move work on to others in order to be more efficient and see more Medi-Cal patients," said Dr. Latimore, associate dean of medicine at the University of California Davis.

The result will be that physicians who work outside of the state’s safety net system will be less likely to participate in the Medi-Cal program or will strictly limit the number of patients they see. That will translate to longer waits to get an appointment and shorter visits for Medi-Cal patients.

Another concern: Patients entering Medi-Cal managed care plans might not have access to a broad network of physicians. While California has network adequacy laws, state oversight is inadequate, according to Ms. Folberg. For the most part, the plans are on an honor system.

There are some bright spots for the Medi-Cal expansion. The ACA includes an increase in Medicaid payments to physicians for 146 primary care services provided in 2013 and 2014. The provision temporarily raises payments up to Medicare rates, which for California physicians means a 136% hike on average, according to an analysis from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

But those payments were delayed, with the first checks going out to physicians in November 2013. That delay could cost the state in physician participation.

"I think the longer it takes to implement that, the less likely it is that it will affect any decisions about whether to participate more fully in the program than you would have otherwise," said Christopher Perrone, deputy director of the health reform and public programs initiative at the California HealthCare Foundation.

And the temporary nature of the pay increase adds to the problem, Mr. Perrone said. "I don’t see California sustaining that increase on its own and I haven’t heard anyone suggest that the federal government would sustain it after the 2 years."

Mr. Perrone said it’s more likely that physicians who are already committed to participating in Medi-Cal will use the money to invest in electronic health records and other telemedicine features, and hire medical assistants.

But with so many small and solo physicians shying away from Medi-Cal because of low payments, community clinics and health centers will have to pick up the slack.

"All these issues together really point to the importance of the community health centers and the role we are going to be playing in ensuring access," said Carmela Castellano-Garcia, president and CEO of the California Primary Care Association.

Federally qualified health centers are in a better position financially because they are paid an enhanced Medicaid rate and won’t be subject to the coming Medi-Cal cuts, Ms. Castellano-Garcia said. And the ACA has directed an influx of cash to these centers as well – more than $500 million in California alone to establish new sites, expand services, and support major capital improvement projects, according to the Health and Human Services department.

Texas: No expansion means doctors will keep feeling pressure

Texas has the highest number of uninsured residents in the United States – a quarter of its 26 million residents lacking coverage – but Gov. Rick Perry (R) refused to expand Medicaid, which could cover as many as 500,000 to 1 million Texans.

The governor’s decision will stay in place at least until 2015, when the state legislature reconvenes.

Some physicians in Texas are not upset by the decision – they consider Medicaid to be low-paying program and full of bureaucratic hassles.

Others – including many of the primary care organizations – disagree.

The Texas Medical Association, the Texas Academy of Family Physicians, and the Texas chapter of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists all support the expansion of Medicaid allowed by the ACA.

In April, Gov. Perry reiterated his position. "Medicaid expansion is a misguided, and ultimately doomed, attempt to mask the shortcomings of Obamacare," he said in a statement. Instead of expansion, he favors flexibility for the state to manage its Medicaid program.

State Rep. John Zerwas (R-Simonton), an anesthesiologist, introduced H.B. 3791 that would give that flexibility, but it did not get consideration by the full House before the legislature adjourned in May.

The TMA supported Dr. Zerwas’ proposal, but also is in favor of expanding Medicaid, said Dr. Stephen L. Brotherton, TMA president. More people would have some type of insurance, but they might not necessarily have good access to care, he said.

That’s because Texas has a shortage of primary care physicians. The number of primary care physicians per capita is lower than the national average – at about 70/100,000 in 2011, compared with 80/100,000 nationally, according to the Texas Department of State Health Services, in the publication "Supply Trends Among Licensed Health Professions, Texas, 1980-2011. In rural areas, it’s even lower – about 50/100,000.

Then there’s the question of just how many physicians will take Medicaid. A 2012 TMA survey found that only 31% of doctors in the state were accepting new Medicaid patients.

Medicaid payment rates are so low that Dr. Brotherton, who practices in Ft. Worth, said that he treats Medicaid patients as charity care. "It’s much less expensive for me to do it for nothing as donated time," he said.

Dr. Moss Hampton, chairman of District XI of ACOG, added, "Medicaid doesn’t cover the cost of taking care of the patient."

For Medicaid expansion to eventually be successful, "there would have to be a better payment rate and less of a hassle factor," said Dr. Hampton, chairman of the obstetrics and gynecology department at Texas Tech Health Sciences Center at the Permian Basin in Odessa.

"It’s hard to get doctors to accept Medicaid because of the rates they pay," agreed Dr. Clare Hawkins, TAFP president, who added that Texas physicians also feel that it’s hard to comply with differing rules among various Medicaid managed care programs.

Even so, expansion will mean getting more patients into preventive care, and a reduction in emergency department visits and more expensive hospital care – costs that are being borne by all Texans, including physicians, said Dr. Hawkins, who is program director of the San Jacinto Methodist Hospital Family Medicine Residency Program in Baytown, Texas.

Although uninsured Texas residents are already receiving care – in emergency departments and at clinics – Medicaid expansion could bring a big uptick in office visits, especially to ob.gyn. practices, Dr. Hampton said. The need for those services is growing with a state law that went into effect on Oct. 29 that makes it prohibitive for most Planned Parenthood clinics and other community clinics that provide abortion services to stay open.

"What that’s done is cut out a very large group of providers, and now we’re trying to find providers to help take care of those folks," who normally use those clinics, she said.

In the absence of Medicaid expansion, Texas physicians are hoping to start receiving higher Medicaid payments that were due to start in Jan. 2013. An estimated 25,000 Texas doctors are eligible for Medicaid pay that will be on par with Medicare. But Texas has not begun to distribute that money and will not likely do so until March, according to the TMA.

When the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Affordable Care Act in 2012, it also ruled that states could choose whether to substantially expand their Medicaid programs. That decision has created a split across the country, with about half of the states choosing to take federal dollars to expand their programs and the others opting out.

There’s no deadline on Medicaid expansion, so those states that have opted out so far can always choose to expand at a later date.

Here’s a look at two bellwether states: California, which has accepted federal money to expand its Medi-Cal program, and Texas, which has opted out of the expansion.

California Gov. Jerry Brown (D), a strong supporter of the ACA, announced that his state would expand Medicaid to include low-income individuals up to 138% of the federal poverty level starting on Jan. 1, 2014. All of the new enrollees – likely 1 million Californians – will be added to the state’s growing Medicaid managed care program.

Conversely, Texas Gov. Rick Perry (R) deemed Medicaid expansion "a misguided, and ultimately doomed, attempt to mask the shortcomings of Obamacare."

California: Pay cuts complicate expansion

Physicians in California are bracing for a significant Medicaid pay cut at the same time as about a million residents are set to join the program.

The pending cuts are just one part of a complex health care picture in California, where experts are far from certain about what the expansion of Medi-Cal will mean for physicians and patients.

"I think we’re going to have a real problem in California with all the new Medi-Cal patients," said Dr. Mark Dressner, who works at a federally qualified health center in Long Beach and is the president of the California Academy of Family Physicians. "Who is going to see them when there’s going to be so many other people in the system?"

The Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that between 990,000 and 1.4 million individuals, mostly single adults, will enter Medi-Cal by 2019 because of the ACA-permitted expansion. Currently, about 8.5 million residents are enrolled. Newly eligible individuals will be enrolled in the program’s managed care health plans.

These new patients could have a hard time finding a doctor. Medi-Cal is one of the lowest payers in the nation, paying between $18 and $24 for an office visit, according to the California Medical Association.

That’s about to be compounded by a pay cut approved by the state and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in 2011. Physicians tried unsuccessfully to fight the cut in court. Now the state is implementing it retroactively, which means that Medi-Cal payments could be cut 15%-20% over the next few years.

"It really undermines efforts to successfully implement the Affordable Care Act in California," said Lisa Folberg, vice president of medical and regulatory policy at the California Medical Association.

There are broad exceptions to the cut. It does not apply to most primary care services in either managed care plans or fee-for-service Medi-Cal, or to specialty services provided through managed care plans, Ms. Folberg said. And some managed care companies have announced that they will use their discretion in setting payment rates to shield their contracted physicians from the cuts.

"Unfortunately, that doesn’t help the cancer patient on Medi-Cal in Bakersfield who has fee-for-service Medi-Cal and can’t find an oncologist," Ms. Folberg said.

Dr. Darin Latimore, president of the California chapter of the American College of Physicians, said large health systems likely will be able to work around the cuts, using group visits and physician extenders. But small physician practices in rural areas aren’t equipped to make those changes, he said.

"They are not in a position to move work on to others in order to be more efficient and see more Medi-Cal patients," said Dr. Latimore, associate dean of medicine at the University of California Davis.

The result will be that physicians who work outside of the state’s safety net system will be less likely to participate in the Medi-Cal program or will strictly limit the number of patients they see. That will translate to longer waits to get an appointment and shorter visits for Medi-Cal patients.

Another concern: Patients entering Medi-Cal managed care plans might not have access to a broad network of physicians. While California has network adequacy laws, state oversight is inadequate, according to Ms. Folberg. For the most part, the plans are on an honor system.

There are some bright spots for the Medi-Cal expansion. The ACA includes an increase in Medicaid payments to physicians for 146 primary care services provided in 2013 and 2014. The provision temporarily raises payments up to Medicare rates, which for California physicians means a 136% hike on average, according to an analysis from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

But those payments were delayed, with the first checks going out to physicians in November 2013. That delay could cost the state in physician participation.

"I think the longer it takes to implement that, the less likely it is that it will affect any decisions about whether to participate more fully in the program than you would have otherwise," said Christopher Perrone, deputy director of the health reform and public programs initiative at the California HealthCare Foundation.

And the temporary nature of the pay increase adds to the problem, Mr. Perrone said. "I don’t see California sustaining that increase on its own and I haven’t heard anyone suggest that the federal government would sustain it after the 2 years."

Mr. Perrone said it’s more likely that physicians who are already committed to participating in Medi-Cal will use the money to invest in electronic health records and other telemedicine features, and hire medical assistants.

But with so many small and solo physicians shying away from Medi-Cal because of low payments, community clinics and health centers will have to pick up the slack.

"All these issues together really point to the importance of the community health centers and the role we are going to be playing in ensuring access," said Carmela Castellano-Garcia, president and CEO of the California Primary Care Association.

Federally qualified health centers are in a better position financially because they are paid an enhanced Medicaid rate and won’t be subject to the coming Medi-Cal cuts, Ms. Castellano-Garcia said. And the ACA has directed an influx of cash to these centers as well – more than $500 million in California alone to establish new sites, expand services, and support major capital improvement projects, according to the Health and Human Services department.

Texas: No expansion means doctors will keep feeling pressure

Texas has the highest number of uninsured residents in the United States – a quarter of its 26 million residents lacking coverage – but Gov. Rick Perry (R) refused to expand Medicaid, which could cover as many as 500,000 to 1 million Texans.

The governor’s decision will stay in place at least until 2015, when the state legislature reconvenes.

Some physicians in Texas are not upset by the decision – they consider Medicaid to be low-paying program and full of bureaucratic hassles.

Others – including many of the primary care organizations – disagree.

The Texas Medical Association, the Texas Academy of Family Physicians, and the Texas chapter of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists all support the expansion of Medicaid allowed by the ACA.

In April, Gov. Perry reiterated his position. "Medicaid expansion is a misguided, and ultimately doomed, attempt to mask the shortcomings of Obamacare," he said in a statement. Instead of expansion, he favors flexibility for the state to manage its Medicaid program.

State Rep. John Zerwas (R-Simonton), an anesthesiologist, introduced H.B. 3791 that would give that flexibility, but it did not get consideration by the full House before the legislature adjourned in May.

The TMA supported Dr. Zerwas’ proposal, but also is in favor of expanding Medicaid, said Dr. Stephen L. Brotherton, TMA president. More people would have some type of insurance, but they might not necessarily have good access to care, he said.

That’s because Texas has a shortage of primary care physicians. The number of primary care physicians per capita is lower than the national average – at about 70/100,000 in 2011, compared with 80/100,000 nationally, according to the Texas Department of State Health Services, in the publication "Supply Trends Among Licensed Health Professions, Texas, 1980-2011. In rural areas, it’s even lower – about 50/100,000.

Then there’s the question of just how many physicians will take Medicaid. A 2012 TMA survey found that only 31% of doctors in the state were accepting new Medicaid patients.

Medicaid payment rates are so low that Dr. Brotherton, who practices in Ft. Worth, said that he treats Medicaid patients as charity care. "It’s much less expensive for me to do it for nothing as donated time," he said.

Dr. Moss Hampton, chairman of District XI of ACOG, added, "Medicaid doesn’t cover the cost of taking care of the patient."

For Medicaid expansion to eventually be successful, "there would have to be a better payment rate and less of a hassle factor," said Dr. Hampton, chairman of the obstetrics and gynecology department at Texas Tech Health Sciences Center at the Permian Basin in Odessa.

"It’s hard to get doctors to accept Medicaid because of the rates they pay," agreed Dr. Clare Hawkins, TAFP president, who added that Texas physicians also feel that it’s hard to comply with differing rules among various Medicaid managed care programs.

Even so, expansion will mean getting more patients into preventive care, and a reduction in emergency department visits and more expensive hospital care – costs that are being borne by all Texans, including physicians, said Dr. Hawkins, who is program director of the San Jacinto Methodist Hospital Family Medicine Residency Program in Baytown, Texas.

Although uninsured Texas residents are already receiving care – in emergency departments and at clinics – Medicaid expansion could bring a big uptick in office visits, especially to ob.gyn. practices, Dr. Hampton said. The need for those services is growing with a state law that went into effect on Oct. 29 that makes it prohibitive for most Planned Parenthood clinics and other community clinics that provide abortion services to stay open.

"What that’s done is cut out a very large group of providers, and now we’re trying to find providers to help take care of those folks," who normally use those clinics, she said.

In the absence of Medicaid expansion, Texas physicians are hoping to start receiving higher Medicaid payments that were due to start in Jan. 2013. An estimated 25,000 Texas doctors are eligible for Medicaid pay that will be on par with Medicare. But Texas has not begun to distribute that money and will not likely do so until March, according to the TMA.

When the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Affordable Care Act in 2012, it also ruled that states could choose whether to substantially expand their Medicaid programs. That decision has created a split across the country, with about half of the states choosing to take federal dollars to expand their programs and the others opting out.

There’s no deadline on Medicaid expansion, so those states that have opted out so far can always choose to expand at a later date.

Here’s a look at two bellwether states: California, which has accepted federal money to expand its Medi-Cal program, and Texas, which has opted out of the expansion.

California Gov. Jerry Brown (D), a strong supporter of the ACA, announced that his state would expand Medicaid to include low-income individuals up to 138% of the federal poverty level starting on Jan. 1, 2014. All of the new enrollees – likely 1 million Californians – will be added to the state’s growing Medicaid managed care program.

Conversely, Texas Gov. Rick Perry (R) deemed Medicaid expansion "a misguided, and ultimately doomed, attempt to mask the shortcomings of Obamacare."

California: Pay cuts complicate expansion

Physicians in California are bracing for a significant Medicaid pay cut at the same time as about a million residents are set to join the program.

The pending cuts are just one part of a complex health care picture in California, where experts are far from certain about what the expansion of Medi-Cal will mean for physicians and patients.

"I think we’re going to have a real problem in California with all the new Medi-Cal patients," said Dr. Mark Dressner, who works at a federally qualified health center in Long Beach and is the president of the California Academy of Family Physicians. "Who is going to see them when there’s going to be so many other people in the system?"

The Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that between 990,000 and 1.4 million individuals, mostly single adults, will enter Medi-Cal by 2019 because of the ACA-permitted expansion. Currently, about 8.5 million residents are enrolled. Newly eligible individuals will be enrolled in the program’s managed care health plans.

These new patients could have a hard time finding a doctor. Medi-Cal is one of the lowest payers in the nation, paying between $18 and $24 for an office visit, according to the California Medical Association.

That’s about to be compounded by a pay cut approved by the state and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in 2011. Physicians tried unsuccessfully to fight the cut in court. Now the state is implementing it retroactively, which means that Medi-Cal payments could be cut 15%-20% over the next few years.

"It really undermines efforts to successfully implement the Affordable Care Act in California," said Lisa Folberg, vice president of medical and regulatory policy at the California Medical Association.

There are broad exceptions to the cut. It does not apply to most primary care services in either managed care plans or fee-for-service Medi-Cal, or to specialty services provided through managed care plans, Ms. Folberg said. And some managed care companies have announced that they will use their discretion in setting payment rates to shield their contracted physicians from the cuts.

"Unfortunately, that doesn’t help the cancer patient on Medi-Cal in Bakersfield who has fee-for-service Medi-Cal and can’t find an oncologist," Ms. Folberg said.

Dr. Darin Latimore, president of the California chapter of the American College of Physicians, said large health systems likely will be able to work around the cuts, using group visits and physician extenders. But small physician practices in rural areas aren’t equipped to make those changes, he said.

"They are not in a position to move work on to others in order to be more efficient and see more Medi-Cal patients," said Dr. Latimore, associate dean of medicine at the University of California Davis.

The result will be that physicians who work outside of the state’s safety net system will be less likely to participate in the Medi-Cal program or will strictly limit the number of patients they see. That will translate to longer waits to get an appointment and shorter visits for Medi-Cal patients.

Another concern: Patients entering Medi-Cal managed care plans might not have access to a broad network of physicians. While California has network adequacy laws, state oversight is inadequate, according to Ms. Folberg. For the most part, the plans are on an honor system.

There are some bright spots for the Medi-Cal expansion. The ACA includes an increase in Medicaid payments to physicians for 146 primary care services provided in 2013 and 2014. The provision temporarily raises payments up to Medicare rates, which for California physicians means a 136% hike on average, according to an analysis from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

But those payments were delayed, with the first checks going out to physicians in November 2013. That delay could cost the state in physician participation.

"I think the longer it takes to implement that, the less likely it is that it will affect any decisions about whether to participate more fully in the program than you would have otherwise," said Christopher Perrone, deputy director of the health reform and public programs initiative at the California HealthCare Foundation.

And the temporary nature of the pay increase adds to the problem, Mr. Perrone said. "I don’t see California sustaining that increase on its own and I haven’t heard anyone suggest that the federal government would sustain it after the 2 years."

Mr. Perrone said it’s more likely that physicians who are already committed to participating in Medi-Cal will use the money to invest in electronic health records and other telemedicine features, and hire medical assistants.

But with so many small and solo physicians shying away from Medi-Cal because of low payments, community clinics and health centers will have to pick up the slack.

"All these issues together really point to the importance of the community health centers and the role we are going to be playing in ensuring access," said Carmela Castellano-Garcia, president and CEO of the California Primary Care Association.

Federally qualified health centers are in a better position financially because they are paid an enhanced Medicaid rate and won’t be subject to the coming Medi-Cal cuts, Ms. Castellano-Garcia said. And the ACA has directed an influx of cash to these centers as well – more than $500 million in California alone to establish new sites, expand services, and support major capital improvement projects, according to the Health and Human Services department.

Texas: No expansion means doctors will keep feeling pressure

Texas has the highest number of uninsured residents in the United States – a quarter of its 26 million residents lacking coverage – but Gov. Rick Perry (R) refused to expand Medicaid, which could cover as many as 500,000 to 1 million Texans.

The governor’s decision will stay in place at least until 2015, when the state legislature reconvenes.

Some physicians in Texas are not upset by the decision – they consider Medicaid to be low-paying program and full of bureaucratic hassles.

Others – including many of the primary care organizations – disagree.

The Texas Medical Association, the Texas Academy of Family Physicians, and the Texas chapter of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists all support the expansion of Medicaid allowed by the ACA.

In April, Gov. Perry reiterated his position. "Medicaid expansion is a misguided, and ultimately doomed, attempt to mask the shortcomings of Obamacare," he said in a statement. Instead of expansion, he favors flexibility for the state to manage its Medicaid program.

State Rep. John Zerwas (R-Simonton), an anesthesiologist, introduced H.B. 3791 that would give that flexibility, but it did not get consideration by the full House before the legislature adjourned in May.

The TMA supported Dr. Zerwas’ proposal, but also is in favor of expanding Medicaid, said Dr. Stephen L. Brotherton, TMA president. More people would have some type of insurance, but they might not necessarily have good access to care, he said.

That’s because Texas has a shortage of primary care physicians. The number of primary care physicians per capita is lower than the national average – at about 70/100,000 in 2011, compared with 80/100,000 nationally, according to the Texas Department of State Health Services, in the publication "Supply Trends Among Licensed Health Professions, Texas, 1980-2011. In rural areas, it’s even lower – about 50/100,000.

Then there’s the question of just how many physicians will take Medicaid. A 2012 TMA survey found that only 31% of doctors in the state were accepting new Medicaid patients.

Medicaid payment rates are so low that Dr. Brotherton, who practices in Ft. Worth, said that he treats Medicaid patients as charity care. "It’s much less expensive for me to do it for nothing as donated time," he said.

Dr. Moss Hampton, chairman of District XI of ACOG, added, "Medicaid doesn’t cover the cost of taking care of the patient."

For Medicaid expansion to eventually be successful, "there would have to be a better payment rate and less of a hassle factor," said Dr. Hampton, chairman of the obstetrics and gynecology department at Texas Tech Health Sciences Center at the Permian Basin in Odessa.

"It’s hard to get doctors to accept Medicaid because of the rates they pay," agreed Dr. Clare Hawkins, TAFP president, who added that Texas physicians also feel that it’s hard to comply with differing rules among various Medicaid managed care programs.

Even so, expansion will mean getting more patients into preventive care, and a reduction in emergency department visits and more expensive hospital care – costs that are being borne by all Texans, including physicians, said Dr. Hawkins, who is program director of the San Jacinto Methodist Hospital Family Medicine Residency Program in Baytown, Texas.

Although uninsured Texas residents are already receiving care – in emergency departments and at clinics – Medicaid expansion could bring a big uptick in office visits, especially to ob.gyn. practices, Dr. Hampton said. The need for those services is growing with a state law that went into effect on Oct. 29 that makes it prohibitive for most Planned Parenthood clinics and other community clinics that provide abortion services to stay open.

"What that’s done is cut out a very large group of providers, and now we’re trying to find providers to help take care of those folks," who normally use those clinics, she said.

In the absence of Medicaid expansion, Texas physicians are hoping to start receiving higher Medicaid payments that were due to start in Jan. 2013. An estimated 25,000 Texas doctors are eligible for Medicaid pay that will be on par with Medicare. But Texas has not begun to distribute that money and will not likely do so until March, according to the TMA.