User login

Andrew N. Wilner, MD, FAAN, FACP

Angels Neurological Centers

Abington, MA

Clinical History

A 37-year-old pregnant African American woman with a history of epilepsy and polysubstance abuse was found unresponsive in a hotel room. She had four convulsions en route to the hospital. In transit, she received levetiracetam and phenytoin, resulting in the cessation of the clinical seizures.

According to her mother, seizures began at age 16 during her first pregnancy, which was complicated by hypertension. She was prescribed medications for hypertension and phenytoin for seizures. The patient provided a different history, claiming that her seizures began 2 years ago. She denied taking medication for seizures or other health problems.

The patient has two children, ages 22 and 11 years. Past medical history is otherwise unremarkable. She has no allergies. Social history includes cigarette smoking, and alcohol and substance abuse. She lives with her boyfriend and does not work. She is 25 weeks pregnant. Family history was notable only for migraine in her mother and grandmother.

Physical Examination

In the emergency department, blood pressure was 135/65, pulse 121 beats per minute, and oxygen saturation was 97%. She was oriented only to self and did not follow commands. Pupils were equal and reactive. There was no facial asymmetry. She moved all 4 extremities spontaneously. Reflexes were brisk. Oral mucosa was dry. She had no edema in the lower extremities.

Laboratories

Chest x-ray was normal. EKG revealed tachycardia and nonspecific ST changes. Hemoglobin was 11.1 g/dl, hematocrit 32%, white blood cell count 10,900, and platelets 181,000. Electrolytes were normal except for a low sodium of 132 mmol/l (135-145) and bicarbonate of 17 mmol/l (21-31). Glucose was initially 67 mg/dl and dropped to 46 mg/dl. Total protein was 6 g/dl (6.7-8.2) and albumin was 2.7 g/dl (3.2-5.5). Metabolic panel was otherwise normal. Urinalysis was positive for glucose, ketones, and a small amount of blood and protein. There were no bacteria. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Phenytoin level was undetectable. Urine drug screen was positive for cannabinoids and cocaine.

Hospital Course

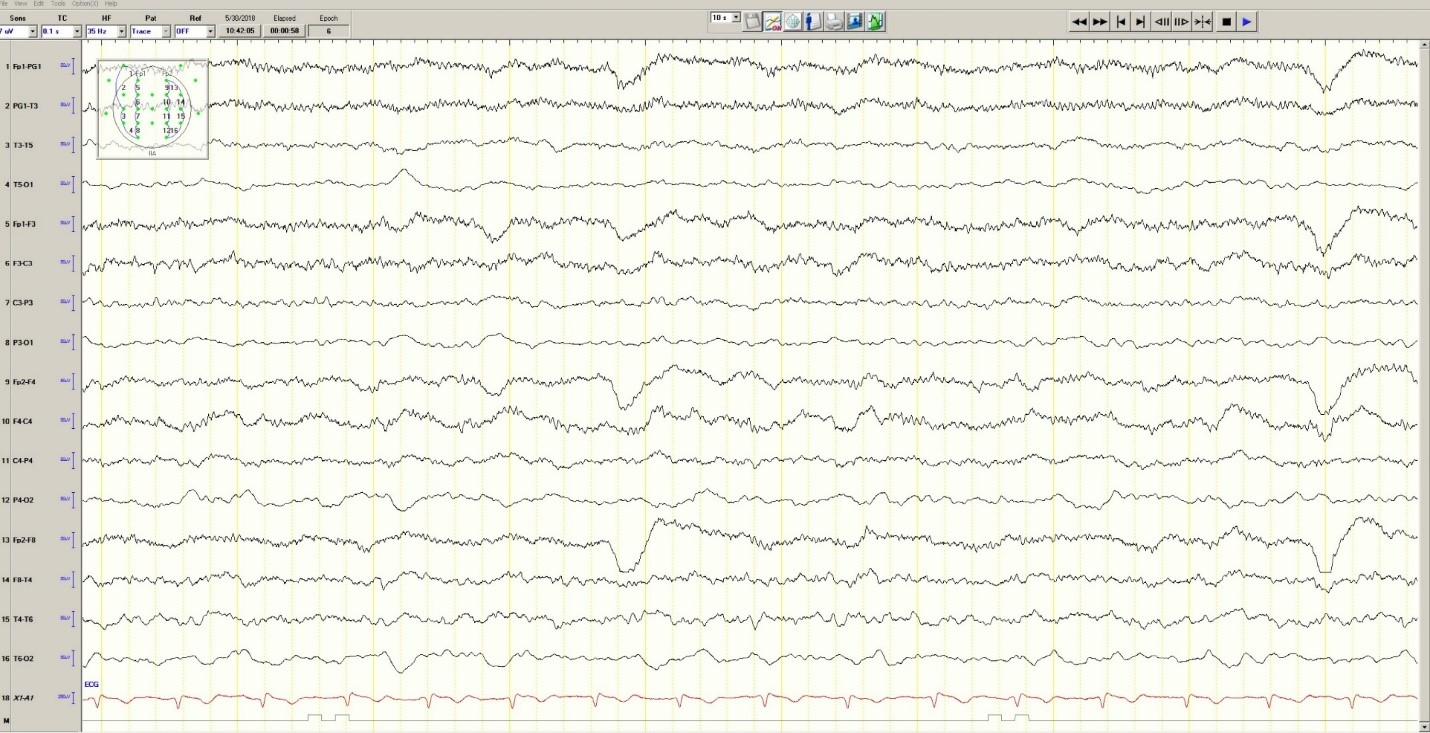

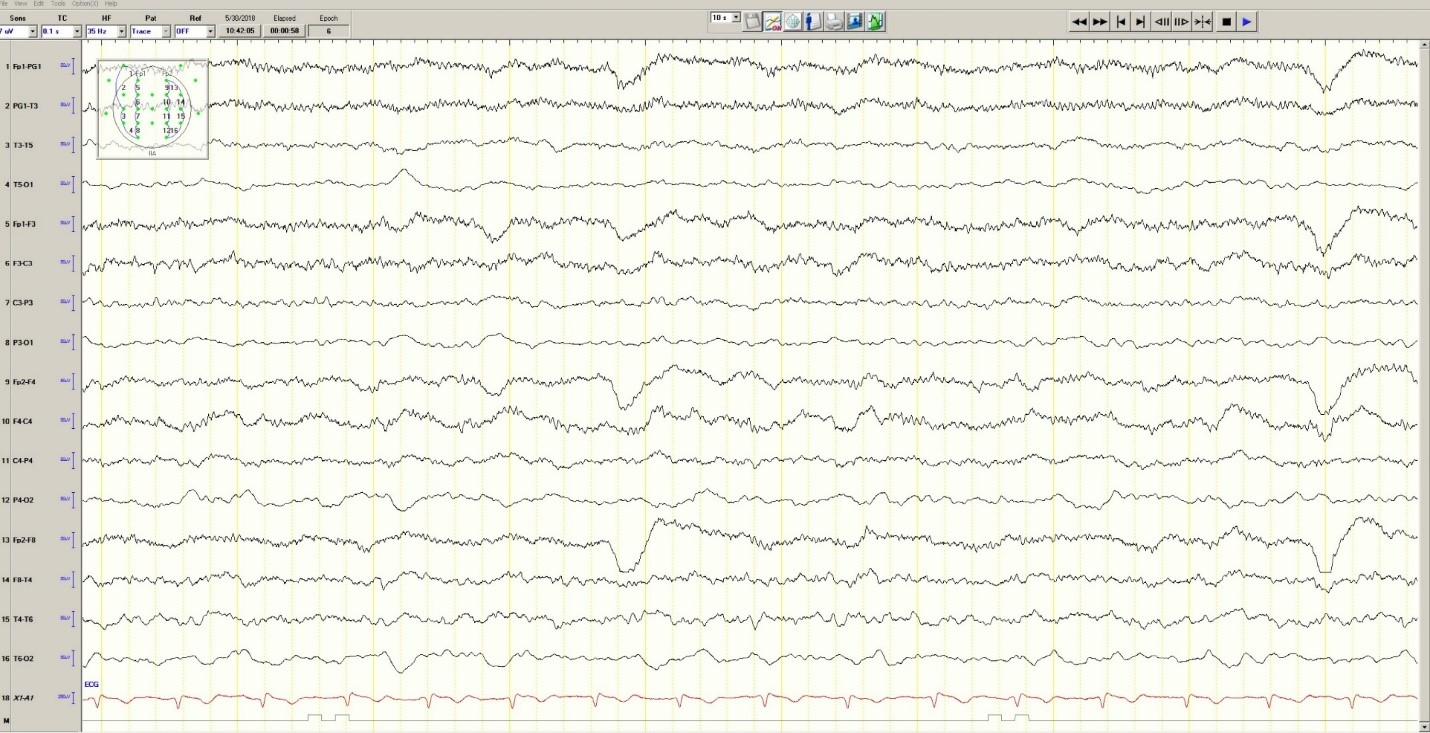

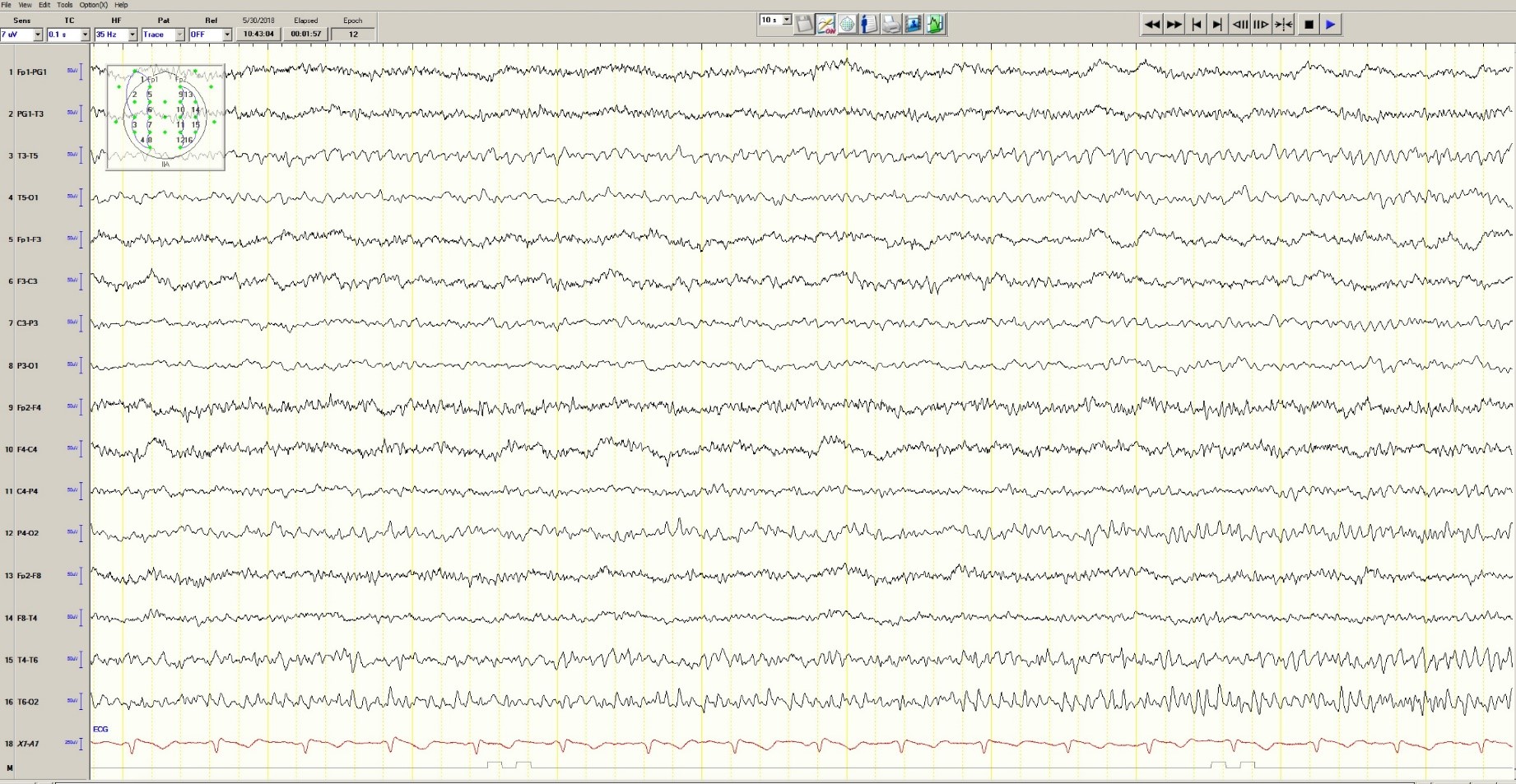

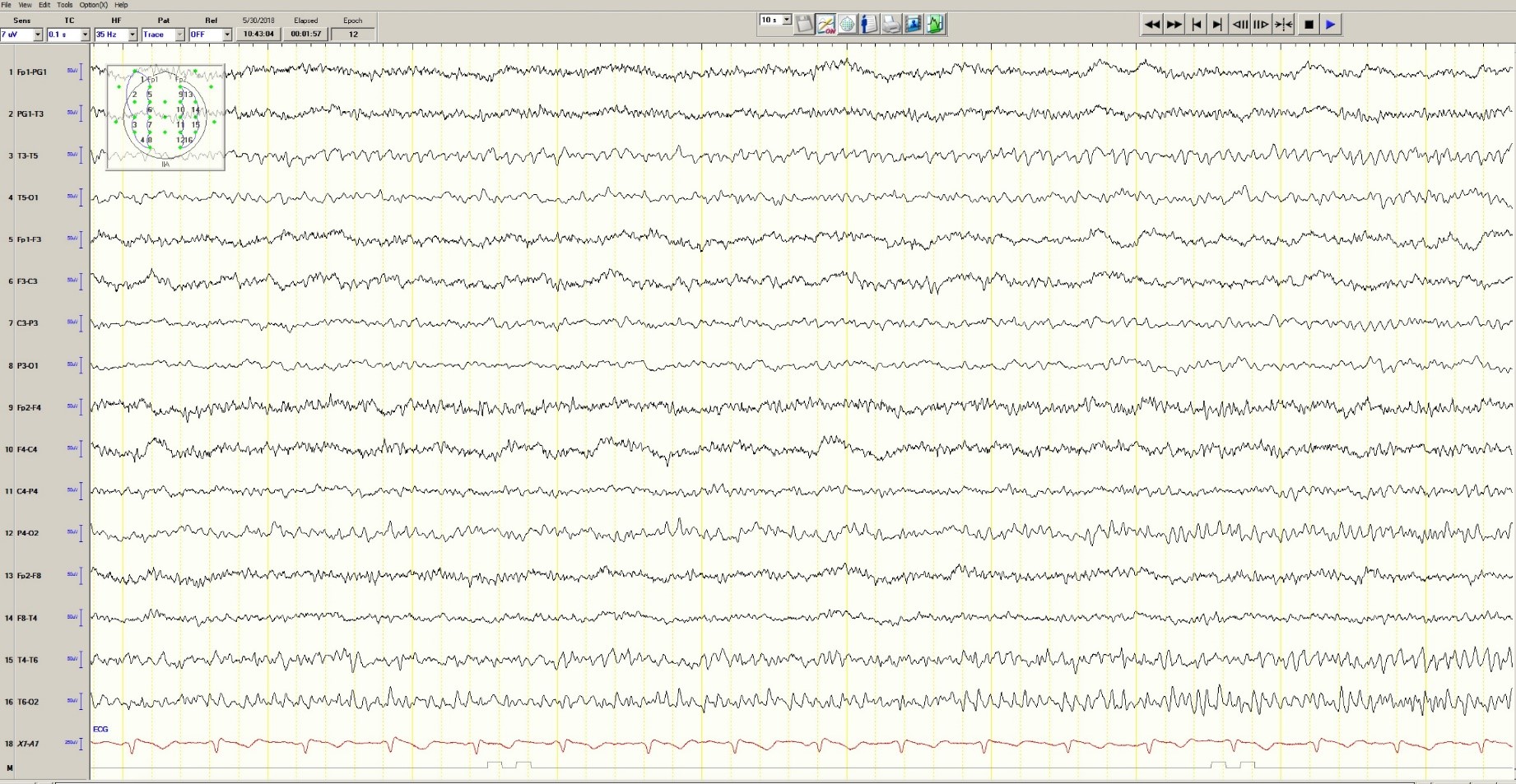

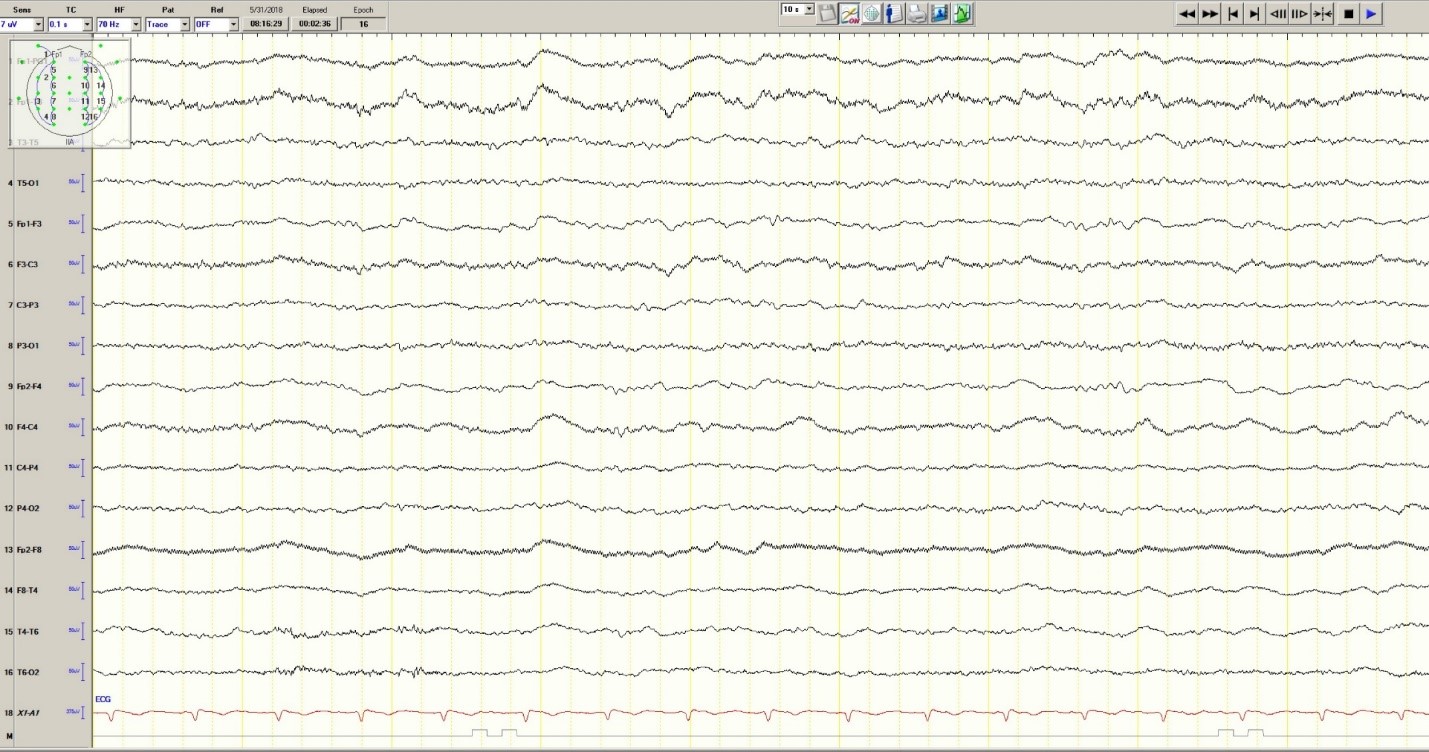

Hypoglycemia was treated with an ampule of D50 and intravenous fluids. On the obstetrics ward, nurses observed several episodes of head and eye deviation to the right accompanied by decreased responsiveness that lasted approximately 30 seconds. The patient was sent to the electrophysiology lab where an EEG revealed a diffusely slow background (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Generalized Slowing

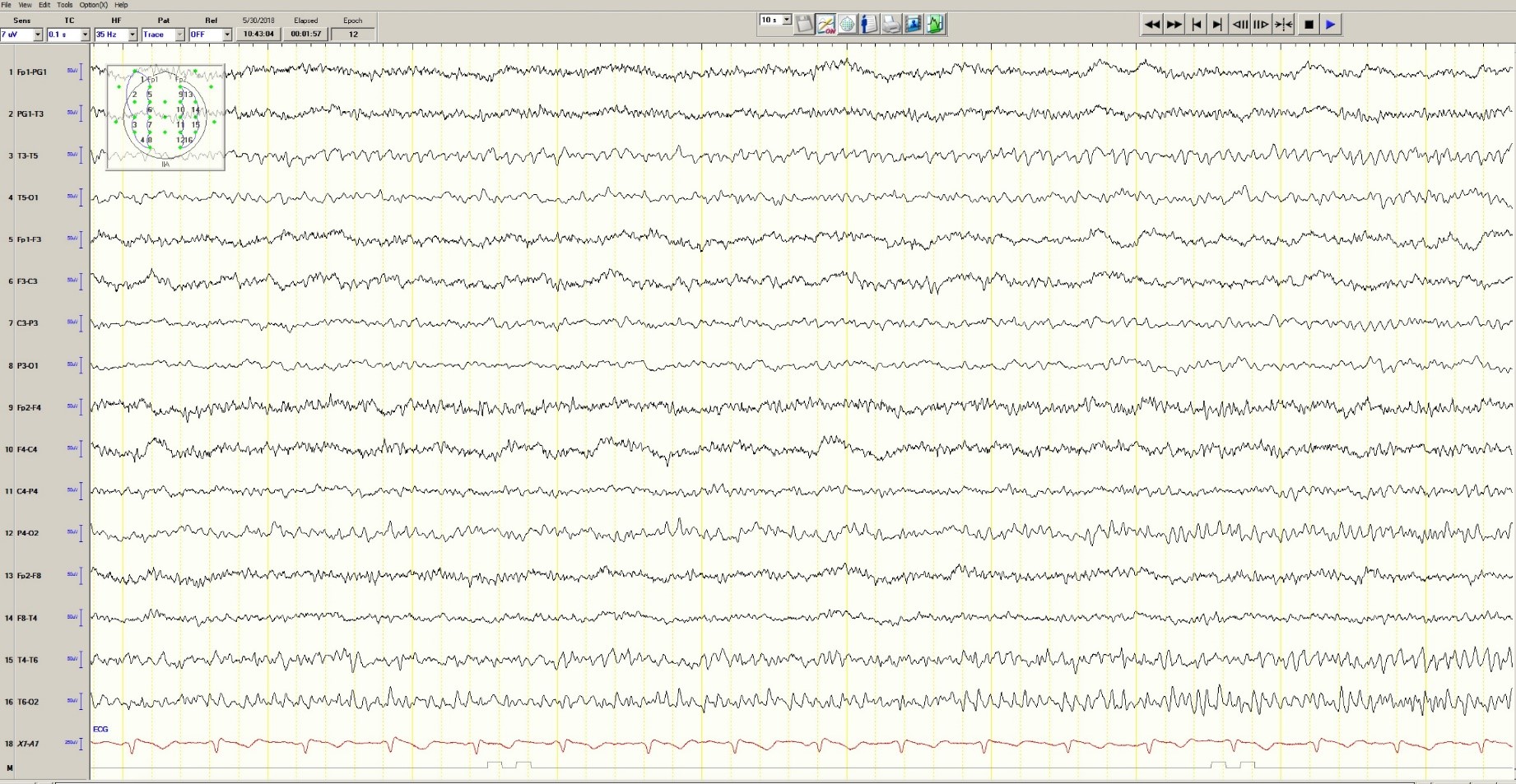

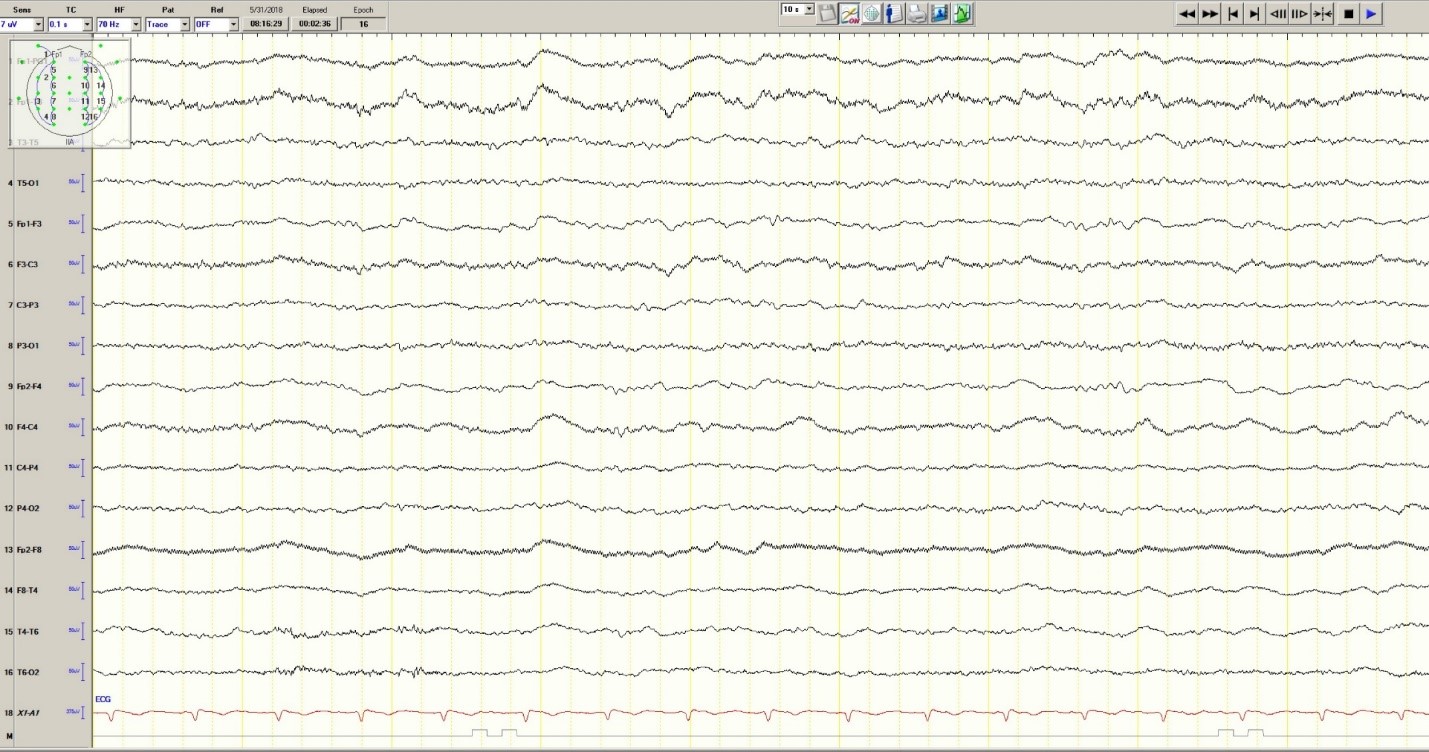

During the 20-minute EEG recording, the patient had six clinical seizures similar to those described by the nurses. These events correlated with an ictal pattern consisting of 11 HZ_sharp activity in the right occipital temporal region that spread to the right parietal and left occipital temporal regions (Figure 2). Head CT revealed mild generalized atrophy and an enlarged right occipital horn, but no acute lesions (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Partial seizure originating in right occipital temporal region

Figure 3. Mild generalized arophy, greater in right hemisphere

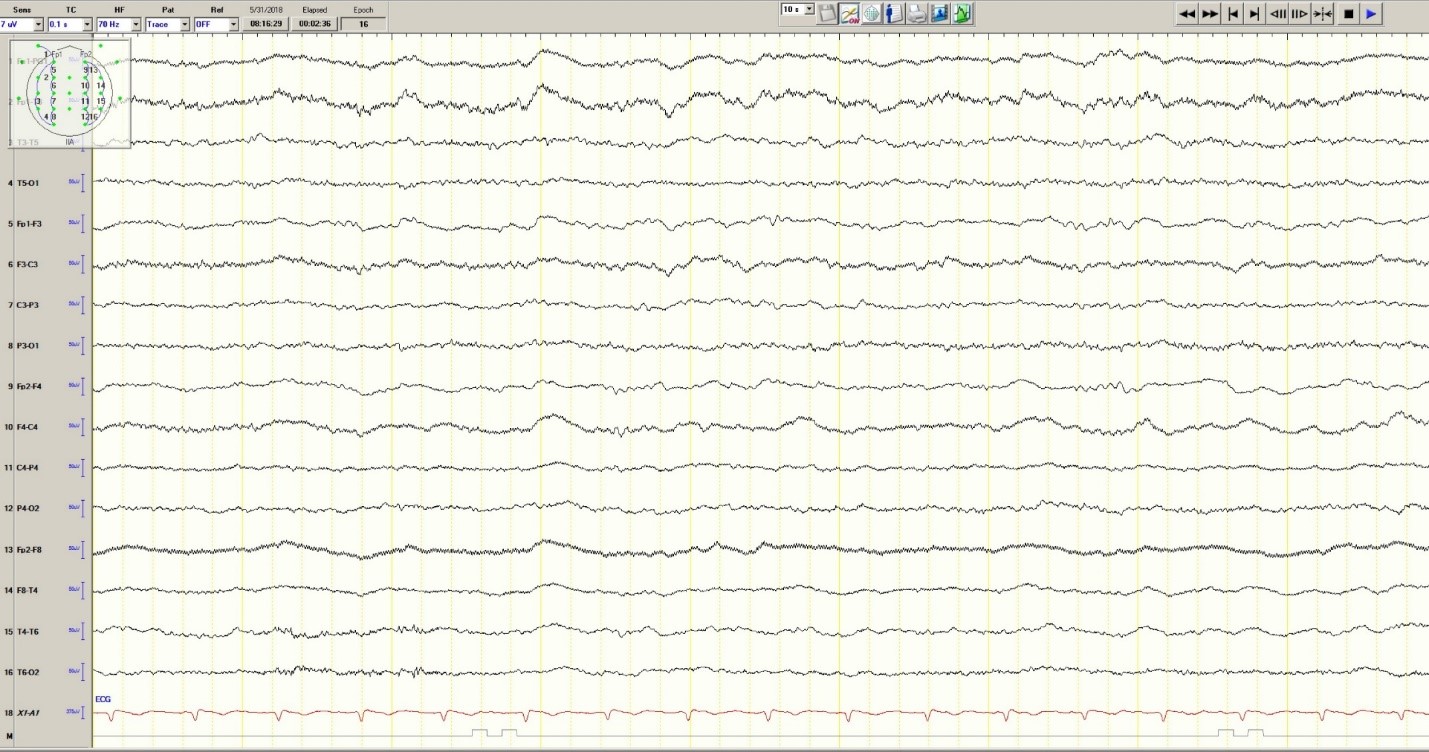

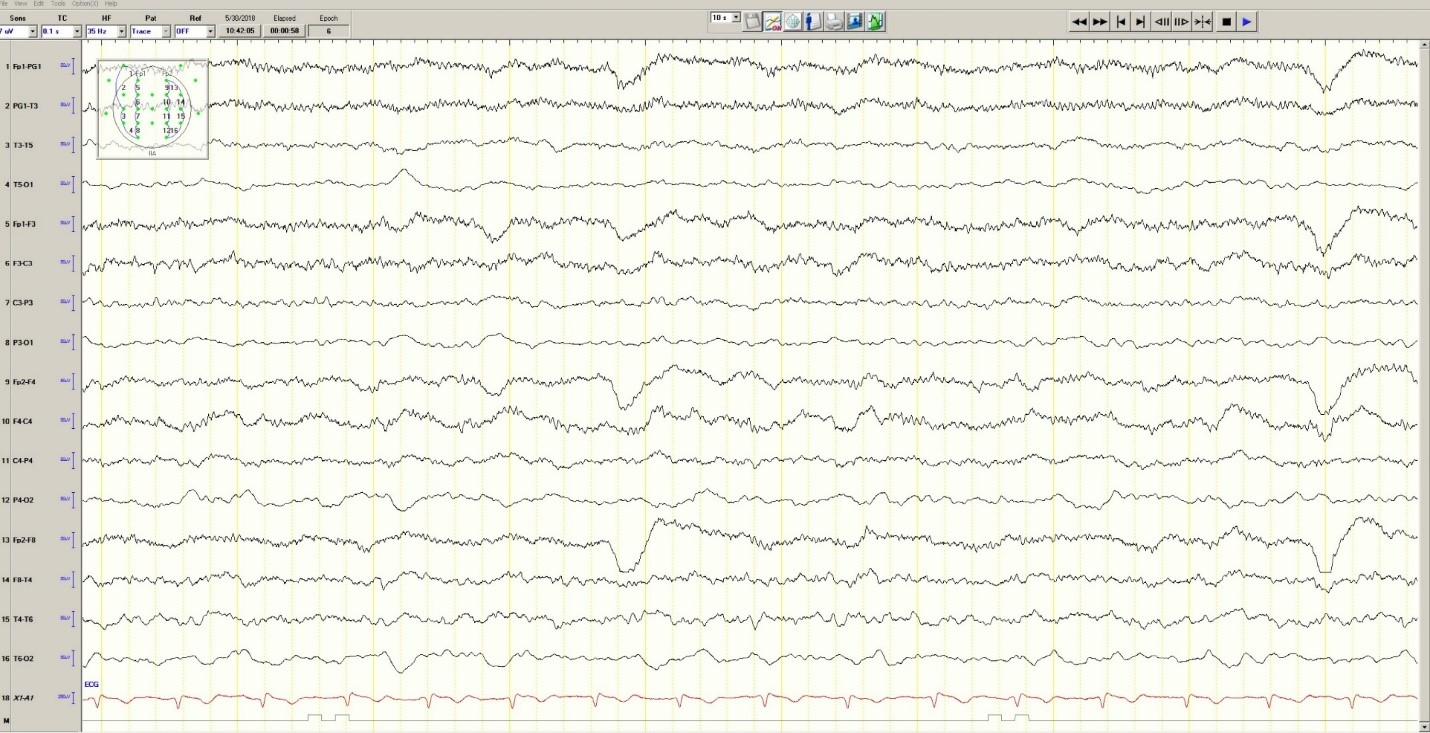

The patient was transferred to intensive care and received fosphenytoin. No further clinical and /or electrographic seizures were identified. The following day, an EEG revealed diffuse slowing without focal seizures (Figure 4). The patient gradually became more alert and cooperative over the next 24 hours. However, the next day no fetal heartbeat was detected. Labor was induced and a stillborn baby delivered. The pathology report indicated that the placenta was between the 5th and 10th percentile for gestational age.

Figure 4. Improved generalized slowing

Discussion

Status epilepticus is associated with significant morbidity and mortality (Claassen et al. 2002). This 37-year-old pregnant woman had an episode of focal status epilepticus with impaired awareness likely provoked by nonadherence to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). Cocaine may have contributed to the episode of status epilepticus (Majlesi et al. 2010). The obstetric service did not diagnose preeclampsia.

The patient’s seizures started in the right occipital region, which was abnormal on neuroimaging. An MRI might have revealed more subtle structural abnormalities such as cortical dysplasia as the etiology of her epilepsy, but she refused the scan.

Women with epilepsy are at increased risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preeclampsia, preterm labor, and stillbirth and should be considered high risk (MacDonald et al. 2015). Serum levels of AEDs such as lamotrigine, levetiracetam and phenytoin may decrease during pregnancy and contribute to breakthrough seizures. Accordingly, monthly measurements of serum levels of AEDs during the entire course of the pregnancy are strongly recommended. These measurements allow for a timely adjustment of AED doses to prevent significant drop in their serum concentrations and minimize the occurrence of breakthrough seizures. In the case of phenytoin, measurement of free and total serum concentrations are recommended. Supplementation with at least 0.4 mg/day to 1 mg /day of folic acid (and up to 4 mg /day) has been recommended (Harden et al. 2009a). Of note, there is no increase in the incidence of status epilepticus due to pregnancy per se (Harden et al. 2009b).

Although the patient survived this episode of status epilepticus, her fetus did not. Antiseizure drug nonadherence and polysubstance abuse probably contributed to fetal demise.

References

Claassen J, Lokin JK, Fitzsimons BFM et al. Predictors of functional disability and mortality after status epilepticus. Neurology. 2002;58:139-142.

Harden CL, Pennell PB, Koppel BS et al. Practice Parameter update: Management issues for women with epilepsy Focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): Vitamin K, folic acid, blood levels, and breastfeeding: Neurology 2009a;73:142-149.

Harden CL, Hopp J, Ting TY et al. Practice Parameter update: Management issues for women with epilepsy-focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): Obstetrical complications and change in seizure frequency. Neurology 2009b;50(5):1229-36.

MacDonald SC, Bateman BT, McElrath TF, Hernandez-Diaz S. Mortality and morbidity during delivery hospitalization among pregnant women with epilepsy in the United States. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(9):981-988.

Majlesi N, Shih R, Fiesseler FW et al. Cocaine-associated seizures and incidence of status epilepticus. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2010;XI(2):157-160.

Andrew N. Wilner, MD, FAAN, FACP

Angels Neurological Centers

Abington, MA

Clinical History

A 37-year-old pregnant African American woman with a history of epilepsy and polysubstance abuse was found unresponsive in a hotel room. She had four convulsions en route to the hospital. In transit, she received levetiracetam and phenytoin, resulting in the cessation of the clinical seizures.

According to her mother, seizures began at age 16 during her first pregnancy, which was complicated by hypertension. She was prescribed medications for hypertension and phenytoin for seizures. The patient provided a different history, claiming that her seizures began 2 years ago. She denied taking medication for seizures or other health problems.

The patient has two children, ages 22 and 11 years. Past medical history is otherwise unremarkable. She has no allergies. Social history includes cigarette smoking, and alcohol and substance abuse. She lives with her boyfriend and does not work. She is 25 weeks pregnant. Family history was notable only for migraine in her mother and grandmother.

Physical Examination

In the emergency department, blood pressure was 135/65, pulse 121 beats per minute, and oxygen saturation was 97%. She was oriented only to self and did not follow commands. Pupils were equal and reactive. There was no facial asymmetry. She moved all 4 extremities spontaneously. Reflexes were brisk. Oral mucosa was dry. She had no edema in the lower extremities.

Laboratories

Chest x-ray was normal. EKG revealed tachycardia and nonspecific ST changes. Hemoglobin was 11.1 g/dl, hematocrit 32%, white blood cell count 10,900, and platelets 181,000. Electrolytes were normal except for a low sodium of 132 mmol/l (135-145) and bicarbonate of 17 mmol/l (21-31). Glucose was initially 67 mg/dl and dropped to 46 mg/dl. Total protein was 6 g/dl (6.7-8.2) and albumin was 2.7 g/dl (3.2-5.5). Metabolic panel was otherwise normal. Urinalysis was positive for glucose, ketones, and a small amount of blood and protein. There were no bacteria. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Phenytoin level was undetectable. Urine drug screen was positive for cannabinoids and cocaine.

Hospital Course

Hypoglycemia was treated with an ampule of D50 and intravenous fluids. On the obstetrics ward, nurses observed several episodes of head and eye deviation to the right accompanied by decreased responsiveness that lasted approximately 30 seconds. The patient was sent to the electrophysiology lab where an EEG revealed a diffusely slow background (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Generalized Slowing

During the 20-minute EEG recording, the patient had six clinical seizures similar to those described by the nurses. These events correlated with an ictal pattern consisting of 11 HZ_sharp activity in the right occipital temporal region that spread to the right parietal and left occipital temporal regions (Figure 2). Head CT revealed mild generalized atrophy and an enlarged right occipital horn, but no acute lesions (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Partial seizure originating in right occipital temporal region

Figure 3. Mild generalized arophy, greater in right hemisphere

The patient was transferred to intensive care and received fosphenytoin. No further clinical and /or electrographic seizures were identified. The following day, an EEG revealed diffuse slowing without focal seizures (Figure 4). The patient gradually became more alert and cooperative over the next 24 hours. However, the next day no fetal heartbeat was detected. Labor was induced and a stillborn baby delivered. The pathology report indicated that the placenta was between the 5th and 10th percentile for gestational age.

Figure 4. Improved generalized slowing

Discussion

Status epilepticus is associated with significant morbidity and mortality (Claassen et al. 2002). This 37-year-old pregnant woman had an episode of focal status epilepticus with impaired awareness likely provoked by nonadherence to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). Cocaine may have contributed to the episode of status epilepticus (Majlesi et al. 2010). The obstetric service did not diagnose preeclampsia.

The patient’s seizures started in the right occipital region, which was abnormal on neuroimaging. An MRI might have revealed more subtle structural abnormalities such as cortical dysplasia as the etiology of her epilepsy, but she refused the scan.

Women with epilepsy are at increased risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preeclampsia, preterm labor, and stillbirth and should be considered high risk (MacDonald et al. 2015). Serum levels of AEDs such as lamotrigine, levetiracetam and phenytoin may decrease during pregnancy and contribute to breakthrough seizures. Accordingly, monthly measurements of serum levels of AEDs during the entire course of the pregnancy are strongly recommended. These measurements allow for a timely adjustment of AED doses to prevent significant drop in their serum concentrations and minimize the occurrence of breakthrough seizures. In the case of phenytoin, measurement of free and total serum concentrations are recommended. Supplementation with at least 0.4 mg/day to 1 mg /day of folic acid (and up to 4 mg /day) has been recommended (Harden et al. 2009a). Of note, there is no increase in the incidence of status epilepticus due to pregnancy per se (Harden et al. 2009b).

Although the patient survived this episode of status epilepticus, her fetus did not. Antiseizure drug nonadherence and polysubstance abuse probably contributed to fetal demise.

References

Claassen J, Lokin JK, Fitzsimons BFM et al. Predictors of functional disability and mortality after status epilepticus. Neurology. 2002;58:139-142.

Harden CL, Pennell PB, Koppel BS et al. Practice Parameter update: Management issues for women with epilepsy Focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): Vitamin K, folic acid, blood levels, and breastfeeding: Neurology 2009a;73:142-149.

Harden CL, Hopp J, Ting TY et al. Practice Parameter update: Management issues for women with epilepsy-focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): Obstetrical complications and change in seizure frequency. Neurology 2009b;50(5):1229-36.

MacDonald SC, Bateman BT, McElrath TF, Hernandez-Diaz S. Mortality and morbidity during delivery hospitalization among pregnant women with epilepsy in the United States. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(9):981-988.

Majlesi N, Shih R, Fiesseler FW et al. Cocaine-associated seizures and incidence of status epilepticus. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2010;XI(2):157-160.

Andrew N. Wilner, MD, FAAN, FACP

Angels Neurological Centers

Abington, MA

Clinical History

A 37-year-old pregnant African American woman with a history of epilepsy and polysubstance abuse was found unresponsive in a hotel room. She had four convulsions en route to the hospital. In transit, she received levetiracetam and phenytoin, resulting in the cessation of the clinical seizures.

According to her mother, seizures began at age 16 during her first pregnancy, which was complicated by hypertension. She was prescribed medications for hypertension and phenytoin for seizures. The patient provided a different history, claiming that her seizures began 2 years ago. She denied taking medication for seizures or other health problems.

The patient has two children, ages 22 and 11 years. Past medical history is otherwise unremarkable. She has no allergies. Social history includes cigarette smoking, and alcohol and substance abuse. She lives with her boyfriend and does not work. She is 25 weeks pregnant. Family history was notable only for migraine in her mother and grandmother.

Physical Examination

In the emergency department, blood pressure was 135/65, pulse 121 beats per minute, and oxygen saturation was 97%. She was oriented only to self and did not follow commands. Pupils were equal and reactive. There was no facial asymmetry. She moved all 4 extremities spontaneously. Reflexes were brisk. Oral mucosa was dry. She had no edema in the lower extremities.

Laboratories

Chest x-ray was normal. EKG revealed tachycardia and nonspecific ST changes. Hemoglobin was 11.1 g/dl, hematocrit 32%, white blood cell count 10,900, and platelets 181,000. Electrolytes were normal except for a low sodium of 132 mmol/l (135-145) and bicarbonate of 17 mmol/l (21-31). Glucose was initially 67 mg/dl and dropped to 46 mg/dl. Total protein was 6 g/dl (6.7-8.2) and albumin was 2.7 g/dl (3.2-5.5). Metabolic panel was otherwise normal. Urinalysis was positive for glucose, ketones, and a small amount of blood and protein. There were no bacteria. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Phenytoin level was undetectable. Urine drug screen was positive for cannabinoids and cocaine.

Hospital Course

Hypoglycemia was treated with an ampule of D50 and intravenous fluids. On the obstetrics ward, nurses observed several episodes of head and eye deviation to the right accompanied by decreased responsiveness that lasted approximately 30 seconds. The patient was sent to the electrophysiology lab where an EEG revealed a diffusely slow background (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Generalized Slowing

During the 20-minute EEG recording, the patient had six clinical seizures similar to those described by the nurses. These events correlated with an ictal pattern consisting of 11 HZ_sharp activity in the right occipital temporal region that spread to the right parietal and left occipital temporal regions (Figure 2). Head CT revealed mild generalized atrophy and an enlarged right occipital horn, but no acute lesions (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Partial seizure originating in right occipital temporal region

Figure 3. Mild generalized arophy, greater in right hemisphere

The patient was transferred to intensive care and received fosphenytoin. No further clinical and /or electrographic seizures were identified. The following day, an EEG revealed diffuse slowing without focal seizures (Figure 4). The patient gradually became more alert and cooperative over the next 24 hours. However, the next day no fetal heartbeat was detected. Labor was induced and a stillborn baby delivered. The pathology report indicated that the placenta was between the 5th and 10th percentile for gestational age.

Figure 4. Improved generalized slowing

Discussion

Status epilepticus is associated with significant morbidity and mortality (Claassen et al. 2002). This 37-year-old pregnant woman had an episode of focal status epilepticus with impaired awareness likely provoked by nonadherence to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). Cocaine may have contributed to the episode of status epilepticus (Majlesi et al. 2010). The obstetric service did not diagnose preeclampsia.

The patient’s seizures started in the right occipital region, which was abnormal on neuroimaging. An MRI might have revealed more subtle structural abnormalities such as cortical dysplasia as the etiology of her epilepsy, but she refused the scan.

Women with epilepsy are at increased risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preeclampsia, preterm labor, and stillbirth and should be considered high risk (MacDonald et al. 2015). Serum levels of AEDs such as lamotrigine, levetiracetam and phenytoin may decrease during pregnancy and contribute to breakthrough seizures. Accordingly, monthly measurements of serum levels of AEDs during the entire course of the pregnancy are strongly recommended. These measurements allow for a timely adjustment of AED doses to prevent significant drop in their serum concentrations and minimize the occurrence of breakthrough seizures. In the case of phenytoin, measurement of free and total serum concentrations are recommended. Supplementation with at least 0.4 mg/day to 1 mg /day of folic acid (and up to 4 mg /day) has been recommended (Harden et al. 2009a). Of note, there is no increase in the incidence of status epilepticus due to pregnancy per se (Harden et al. 2009b).

Although the patient survived this episode of status epilepticus, her fetus did not. Antiseizure drug nonadherence and polysubstance abuse probably contributed to fetal demise.

References

Claassen J, Lokin JK, Fitzsimons BFM et al. Predictors of functional disability and mortality after status epilepticus. Neurology. 2002;58:139-142.

Harden CL, Pennell PB, Koppel BS et al. Practice Parameter update: Management issues for women with epilepsy Focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): Vitamin K, folic acid, blood levels, and breastfeeding: Neurology 2009a;73:142-149.

Harden CL, Hopp J, Ting TY et al. Practice Parameter update: Management issues for women with epilepsy-focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): Obstetrical complications and change in seizure frequency. Neurology 2009b;50(5):1229-36.

MacDonald SC, Bateman BT, McElrath TF, Hernandez-Diaz S. Mortality and morbidity during delivery hospitalization among pregnant women with epilepsy in the United States. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(9):981-988.

Majlesi N, Shih R, Fiesseler FW et al. Cocaine-associated seizures and incidence of status epilepticus. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2010;XI(2):157-160.