User login

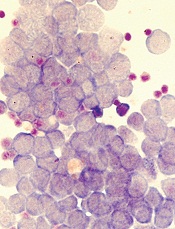

Image by Robert Paulson

New research suggests leukemia stem cells (LSCs) can “hide” in gonadal adipose tissue (GAT) and transform the tissue so they can survive treatment.

Experiments in a mouse model of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) showed that LSCs are enriched in GAT.

While there, the LSCs create a microenvironment that supports leukemic growth and resistance to treatment, and expression of the fatty acid transporter CD36 makes LSCs particularly resistant.

Craig Jordan, PhD, of University of Colorado in Aurora, and his colleagues conducted this research and detailed their findings in Cell Stem Cell.

The researchers began by examining cancer cells found in GAT from mice with blast crisis CML. Rather than containing the expected mix of regular leukemia cells and LSCs, the tissue was enriched for LSCs.

And these GAT-resident LSCs used a different energy source than LSCs in the bone marrow microenvironment. The GAT-resident LSCs powered their survival and growth with fatty acids, manufacturing energy by the process of fatty acid oxidization.

In fact, the GAT-resident LSCs actively signaled fat to undergo lipolysis, which released fatty acids into the microenvironment.

“The basic biology was fascinating,” Dr Jordan said. “The tumor adapted the local environment to suit itself.”

Dr Jordan and his colleagues also found that CD36 played a role. CD36+ LSCs were enriched in GAT, were more likely to migrate to GAT than to bone marrow, and were protected from treatment by GAT.

The researchers tested the effects of several drugs (cytarabine, doxorubicin, etoposide, SN-38, irinotecan, and dasatinib) on CD36+ LSCs, CD36- LSCs, and bulk leukemia cells ex vivo.

Both CD36+ and CD36- LSCs were more resistant to treatment than bulk leukemia cells, but CD36+ LSCs were preferentially drug-resistant.

The researchers observed similar results in leukemic mice and found evidence to suggest that CD36 plays a similar role in patients with blast crisis CML and those with acute myeloid leukemia. ![]()

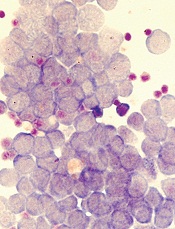

Image by Robert Paulson

New research suggests leukemia stem cells (LSCs) can “hide” in gonadal adipose tissue (GAT) and transform the tissue so they can survive treatment.

Experiments in a mouse model of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) showed that LSCs are enriched in GAT.

While there, the LSCs create a microenvironment that supports leukemic growth and resistance to treatment, and expression of the fatty acid transporter CD36 makes LSCs particularly resistant.

Craig Jordan, PhD, of University of Colorado in Aurora, and his colleagues conducted this research and detailed their findings in Cell Stem Cell.

The researchers began by examining cancer cells found in GAT from mice with blast crisis CML. Rather than containing the expected mix of regular leukemia cells and LSCs, the tissue was enriched for LSCs.

And these GAT-resident LSCs used a different energy source than LSCs in the bone marrow microenvironment. The GAT-resident LSCs powered their survival and growth with fatty acids, manufacturing energy by the process of fatty acid oxidization.

In fact, the GAT-resident LSCs actively signaled fat to undergo lipolysis, which released fatty acids into the microenvironment.

“The basic biology was fascinating,” Dr Jordan said. “The tumor adapted the local environment to suit itself.”

Dr Jordan and his colleagues also found that CD36 played a role. CD36+ LSCs were enriched in GAT, were more likely to migrate to GAT than to bone marrow, and were protected from treatment by GAT.

The researchers tested the effects of several drugs (cytarabine, doxorubicin, etoposide, SN-38, irinotecan, and dasatinib) on CD36+ LSCs, CD36- LSCs, and bulk leukemia cells ex vivo.

Both CD36+ and CD36- LSCs were more resistant to treatment than bulk leukemia cells, but CD36+ LSCs were preferentially drug-resistant.

The researchers observed similar results in leukemic mice and found evidence to suggest that CD36 plays a similar role in patients with blast crisis CML and those with acute myeloid leukemia. ![]()

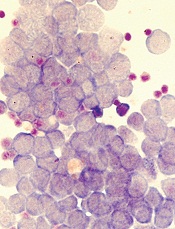

Image by Robert Paulson

New research suggests leukemia stem cells (LSCs) can “hide” in gonadal adipose tissue (GAT) and transform the tissue so they can survive treatment.

Experiments in a mouse model of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) showed that LSCs are enriched in GAT.

While there, the LSCs create a microenvironment that supports leukemic growth and resistance to treatment, and expression of the fatty acid transporter CD36 makes LSCs particularly resistant.

Craig Jordan, PhD, of University of Colorado in Aurora, and his colleagues conducted this research and detailed their findings in Cell Stem Cell.

The researchers began by examining cancer cells found in GAT from mice with blast crisis CML. Rather than containing the expected mix of regular leukemia cells and LSCs, the tissue was enriched for LSCs.

And these GAT-resident LSCs used a different energy source than LSCs in the bone marrow microenvironment. The GAT-resident LSCs powered their survival and growth with fatty acids, manufacturing energy by the process of fatty acid oxidization.

In fact, the GAT-resident LSCs actively signaled fat to undergo lipolysis, which released fatty acids into the microenvironment.

“The basic biology was fascinating,” Dr Jordan said. “The tumor adapted the local environment to suit itself.”

Dr Jordan and his colleagues also found that CD36 played a role. CD36+ LSCs were enriched in GAT, were more likely to migrate to GAT than to bone marrow, and were protected from treatment by GAT.

The researchers tested the effects of several drugs (cytarabine, doxorubicin, etoposide, SN-38, irinotecan, and dasatinib) on CD36+ LSCs, CD36- LSCs, and bulk leukemia cells ex vivo.

Both CD36+ and CD36- LSCs were more resistant to treatment than bulk leukemia cells, but CD36+ LSCs were preferentially drug-resistant.

The researchers observed similar results in leukemic mice and found evidence to suggest that CD36 plays a similar role in patients with blast crisis CML and those with acute myeloid leukemia. ![]()