User login

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – Policy makers are scrambling for ways to bring down health care spending, but what if it were as simple as telling physicians how much things cost?

A new study by investigators at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, which looks at the impact of displaying cost data on laboratory tests, shows that physicians' behavior is affected by seeing the price of the tests they order.

To see how having cost data at the time of order entry would affect behavior, researchers at Johns Hopkins compiled a list of both the most frequently ordered and the most expensive laboratory tests in their hospital, based on 2007 data.

Costly tests were only included in the study if they were ordered at least 50 times during the year. The researchers then randomized the tests to be either active tests or concurrent controls. For active tests, the researchers displayed the price, based on 2008 Medicare allowable cost figures, on the hospital's computerized provider order entry (CPOE) system. For example, a blood gas was listed at $28.25 and a heme-8 lab was $9.37.

Results

During the 6-month intervention period from November 2009 to May 2010, there was a mean decrease of about $15,692 per test for the lab tests in which cost data was displayed in the CPOE, compared with a baseline period exactly 1 year earlier.

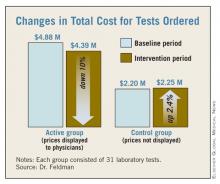

For all 31 of the active tests, there was a combined decrease of about $486,000, resulting in a 10% reduction among tests in which the costs were displayed. The active test costs dropped from $4,877,439 to $4,390,979. Among the group of 31 control tests, in which cost information was not listed on the CPOE, there was a mean increase of $1,718 per test. Overall, costs for the control group went up about $53,000 for all 31 tests.

The total number of tests ordered in the active group fell from 458,518 during the baseline period to 417,078 during the intervention. But in the control group, the number of tests rose from 142,196 to 149,455 during the study period.

Investigator Doesn't Find Results Surprising

Dr. Leonard Feldman, one of the study investigators and who is in the department of medicine at Johns Hopkins, said the results did not come as a surprise.

"I think many of us do recognize that a lot of these tests and imaging studies that are done are unnecessary," Dr. Feldman said during the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Physicians order unnecessary tests for a number of reasons, he said, ranging from defensive medicine to patient expectations. But another reason is a lack of awareness of how much the tests cost, he said. "We, as doctors, have a limited understanding of diagnostic and nondrug therapeutic costs," Dr. Feldman said. "We just have no idea, mostly, how much things cost when we go to order them."

Study Limitations

While the study appears to show a relatively simple and inexpensive way to reduce the ordering of tests, Dr. Feldman acknowledged that the study had some limitations. For example, the study looked at only costs and did not include data on how the change in orders might have affected patient outcomes. And the intervention period was only 6 months.

Dr. Feldman said more time would be needed to show whether physicians would begin to ignore the costs over time. Similarly, costs were only displayed for 31 tests during the study. It's unclear if displaying all laboratory test costs would have the same effect on behavior, Dr. Feldman said.

The authors reported no financial disclosures.

In invited commentary, Dr. Franklin A. Michota said

that “Dr. Leonard Feldman and his colleagues at Johns Hopkins

Hospital have recently

demonstrated that cost visibility for health care providers can decrease

resource utilization. They are cautious to limit their findings to several

specific laboratory tests; however, this simple approach has widespread

applicability beyond laboratory testing and has the potential for great cost

savings across the U.S.

health care system. But before we start putting visible price tags on all of

our hospital order sheets, products, and medications, we should review what we

really know about cost visibility and the risk for adverse consequences”

according to Dr. Michota, director of academic affairs in the department of

hospital medicine at the Cleveland Clinic.

“Dr. Feldman readily

admits that patient outcomes were not reviewed in their preliminary study. It

certainly seems plausible that cost visibility reduced the ordering of

redundant and unnecessary laboratory tests. It is also plausible that necessary

and appropriate testing was omitted because of concerns over cost. We cannot

and should not look at a reduction in resource utilization with a smile on our

face without confirming at least a neutral effect on patient outcome” said Dr.

Michota.

“To that end, we must

also consider the spectrum of patient outcome and how we as individual

providers factor cost into medical decision making. There are many outcomes in

patient care, including patient satisfaction and comfort. Which outcomes should

matter the most? From which perspective do we apply our cost thresholds?

“I have often said

that I have yet to meet an American who isn’t willing to have an infinite

amount of money spent on them for the smallest improvement in outcome. How

should physicians weigh the various outcomes in balance with the visible cost?

One particular danger is the effect of physician experience on the benefit/cost

equation. Cost visibility puts the cost data right in front of the physician in

real time, yet there is no ‘equal display’ regarding the benefits. It stands to

reason that if the physician is unaware of the benefits due to lack of

experience, the medical decision making will be inappropriately weighted toward

the cost,” Dr. Michota said.

“Finally, there is

also an inherent injustice to applying cost-based decisions at the individual

patient level which is the basis of the cost-visibility approach. Most patients

are randomly assigned to hospitalists. Despite identical presentations, one

patient could receive less ‘care’ (such as testing, therapies, resources) because

his or her physician weighted the visible cost of care differently than did the

physician caring for the patient in the next bed. To avoid this conflict,

bioethicists recommend that cost-based decisions be made at the population, not

the individual level. Hospital formularies are a good example of this

technique. Cost visibility applied to individual patients without standardized

approaches on how to use the information consistently across all patients could

otherwise be considered unethical,” he said.

“Ultimately,

hospitalists should strive for value (quality/cost) in health care. As patient

advocates, we need to make sure that the quality is just as visible as the

cost,” according to Dr. Michota.

Dr. Franklin A. Michota, director of academic affairs in the department of

hospital medicine at the Cleveland Clinic. He declared no relevant financial disclosures.

In invited commentary, Dr. Franklin A. Michota said

that “Dr. Leonard Feldman and his colleagues at Johns Hopkins

Hospital have recently

demonstrated that cost visibility for health care providers can decrease

resource utilization. They are cautious to limit their findings to several

specific laboratory tests; however, this simple approach has widespread

applicability beyond laboratory testing and has the potential for great cost

savings across the U.S.

health care system. But before we start putting visible price tags on all of

our hospital order sheets, products, and medications, we should review what we

really know about cost visibility and the risk for adverse consequences”

according to Dr. Michota, director of academic affairs in the department of

hospital medicine at the Cleveland Clinic.

“Dr. Feldman readily

admits that patient outcomes were not reviewed in their preliminary study. It

certainly seems plausible that cost visibility reduced the ordering of

redundant and unnecessary laboratory tests. It is also plausible that necessary

and appropriate testing was omitted because of concerns over cost. We cannot

and should not look at a reduction in resource utilization with a smile on our

face without confirming at least a neutral effect on patient outcome” said Dr.

Michota.

“To that end, we must

also consider the spectrum of patient outcome and how we as individual

providers factor cost into medical decision making. There are many outcomes in

patient care, including patient satisfaction and comfort. Which outcomes should

matter the most? From which perspective do we apply our cost thresholds?

“I have often said

that I have yet to meet an American who isn’t willing to have an infinite

amount of money spent on them for the smallest improvement in outcome. How

should physicians weigh the various outcomes in balance with the visible cost?

One particular danger is the effect of physician experience on the benefit/cost

equation. Cost visibility puts the cost data right in front of the physician in

real time, yet there is no ‘equal display’ regarding the benefits. It stands to

reason that if the physician is unaware of the benefits due to lack of

experience, the medical decision making will be inappropriately weighted toward

the cost,” Dr. Michota said.

“Finally, there is

also an inherent injustice to applying cost-based decisions at the individual

patient level which is the basis of the cost-visibility approach. Most patients

are randomly assigned to hospitalists. Despite identical presentations, one

patient could receive less ‘care’ (such as testing, therapies, resources) because

his or her physician weighted the visible cost of care differently than did the

physician caring for the patient in the next bed. To avoid this conflict,

bioethicists recommend that cost-based decisions be made at the population, not

the individual level. Hospital formularies are a good example of this

technique. Cost visibility applied to individual patients without standardized

approaches on how to use the information consistently across all patients could

otherwise be considered unethical,” he said.

“Ultimately,

hospitalists should strive for value (quality/cost) in health care. As patient

advocates, we need to make sure that the quality is just as visible as the

cost,” according to Dr. Michota.

Dr. Franklin A. Michota, director of academic affairs in the department of

hospital medicine at the Cleveland Clinic. He declared no relevant financial disclosures.

In invited commentary, Dr. Franklin A. Michota said

that “Dr. Leonard Feldman and his colleagues at Johns Hopkins

Hospital have recently

demonstrated that cost visibility for health care providers can decrease

resource utilization. They are cautious to limit their findings to several

specific laboratory tests; however, this simple approach has widespread

applicability beyond laboratory testing and has the potential for great cost

savings across the U.S.

health care system. But before we start putting visible price tags on all of

our hospital order sheets, products, and medications, we should review what we

really know about cost visibility and the risk for adverse consequences”

according to Dr. Michota, director of academic affairs in the department of

hospital medicine at the Cleveland Clinic.

“Dr. Feldman readily

admits that patient outcomes were not reviewed in their preliminary study. It

certainly seems plausible that cost visibility reduced the ordering of

redundant and unnecessary laboratory tests. It is also plausible that necessary

and appropriate testing was omitted because of concerns over cost. We cannot

and should not look at a reduction in resource utilization with a smile on our

face without confirming at least a neutral effect on patient outcome” said Dr.

Michota.

“To that end, we must

also consider the spectrum of patient outcome and how we as individual

providers factor cost into medical decision making. There are many outcomes in

patient care, including patient satisfaction and comfort. Which outcomes should

matter the most? From which perspective do we apply our cost thresholds?

“I have often said

that I have yet to meet an American who isn’t willing to have an infinite

amount of money spent on them for the smallest improvement in outcome. How

should physicians weigh the various outcomes in balance with the visible cost?

One particular danger is the effect of physician experience on the benefit/cost

equation. Cost visibility puts the cost data right in front of the physician in

real time, yet there is no ‘equal display’ regarding the benefits. It stands to

reason that if the physician is unaware of the benefits due to lack of

experience, the medical decision making will be inappropriately weighted toward

the cost,” Dr. Michota said.

“Finally, there is

also an inherent injustice to applying cost-based decisions at the individual

patient level which is the basis of the cost-visibility approach. Most patients

are randomly assigned to hospitalists. Despite identical presentations, one

patient could receive less ‘care’ (such as testing, therapies, resources) because

his or her physician weighted the visible cost of care differently than did the

physician caring for the patient in the next bed. To avoid this conflict,

bioethicists recommend that cost-based decisions be made at the population, not

the individual level. Hospital formularies are a good example of this

technique. Cost visibility applied to individual patients without standardized

approaches on how to use the information consistently across all patients could

otherwise be considered unethical,” he said.

“Ultimately,

hospitalists should strive for value (quality/cost) in health care. As patient

advocates, we need to make sure that the quality is just as visible as the

cost,” according to Dr. Michota.

Dr. Franklin A. Michota, director of academic affairs in the department of

hospital medicine at the Cleveland Clinic. He declared no relevant financial disclosures.

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – Policy makers are scrambling for ways to bring down health care spending, but what if it were as simple as telling physicians how much things cost?

A new study by investigators at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, which looks at the impact of displaying cost data on laboratory tests, shows that physicians' behavior is affected by seeing the price of the tests they order.

To see how having cost data at the time of order entry would affect behavior, researchers at Johns Hopkins compiled a list of both the most frequently ordered and the most expensive laboratory tests in their hospital, based on 2007 data.

Costly tests were only included in the study if they were ordered at least 50 times during the year. The researchers then randomized the tests to be either active tests or concurrent controls. For active tests, the researchers displayed the price, based on 2008 Medicare allowable cost figures, on the hospital's computerized provider order entry (CPOE) system. For example, a blood gas was listed at $28.25 and a heme-8 lab was $9.37.

Results

During the 6-month intervention period from November 2009 to May 2010, there was a mean decrease of about $15,692 per test for the lab tests in which cost data was displayed in the CPOE, compared with a baseline period exactly 1 year earlier.

For all 31 of the active tests, there was a combined decrease of about $486,000, resulting in a 10% reduction among tests in which the costs were displayed. The active test costs dropped from $4,877,439 to $4,390,979. Among the group of 31 control tests, in which cost information was not listed on the CPOE, there was a mean increase of $1,718 per test. Overall, costs for the control group went up about $53,000 for all 31 tests.

The total number of tests ordered in the active group fell from 458,518 during the baseline period to 417,078 during the intervention. But in the control group, the number of tests rose from 142,196 to 149,455 during the study period.

Investigator Doesn't Find Results Surprising

Dr. Leonard Feldman, one of the study investigators and who is in the department of medicine at Johns Hopkins, said the results did not come as a surprise.

"I think many of us do recognize that a lot of these tests and imaging studies that are done are unnecessary," Dr. Feldman said during the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Physicians order unnecessary tests for a number of reasons, he said, ranging from defensive medicine to patient expectations. But another reason is a lack of awareness of how much the tests cost, he said. "We, as doctors, have a limited understanding of diagnostic and nondrug therapeutic costs," Dr. Feldman said. "We just have no idea, mostly, how much things cost when we go to order them."

Study Limitations

While the study appears to show a relatively simple and inexpensive way to reduce the ordering of tests, Dr. Feldman acknowledged that the study had some limitations. For example, the study looked at only costs and did not include data on how the change in orders might have affected patient outcomes. And the intervention period was only 6 months.

Dr. Feldman said more time would be needed to show whether physicians would begin to ignore the costs over time. Similarly, costs were only displayed for 31 tests during the study. It's unclear if displaying all laboratory test costs would have the same effect on behavior, Dr. Feldman said.

The authors reported no financial disclosures.

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – Policy makers are scrambling for ways to bring down health care spending, but what if it were as simple as telling physicians how much things cost?

A new study by investigators at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, which looks at the impact of displaying cost data on laboratory tests, shows that physicians' behavior is affected by seeing the price of the tests they order.

To see how having cost data at the time of order entry would affect behavior, researchers at Johns Hopkins compiled a list of both the most frequently ordered and the most expensive laboratory tests in their hospital, based on 2007 data.

Costly tests were only included in the study if they were ordered at least 50 times during the year. The researchers then randomized the tests to be either active tests or concurrent controls. For active tests, the researchers displayed the price, based on 2008 Medicare allowable cost figures, on the hospital's computerized provider order entry (CPOE) system. For example, a blood gas was listed at $28.25 and a heme-8 lab was $9.37.

Results

During the 6-month intervention period from November 2009 to May 2010, there was a mean decrease of about $15,692 per test for the lab tests in which cost data was displayed in the CPOE, compared with a baseline period exactly 1 year earlier.

For all 31 of the active tests, there was a combined decrease of about $486,000, resulting in a 10% reduction among tests in which the costs were displayed. The active test costs dropped from $4,877,439 to $4,390,979. Among the group of 31 control tests, in which cost information was not listed on the CPOE, there was a mean increase of $1,718 per test. Overall, costs for the control group went up about $53,000 for all 31 tests.

The total number of tests ordered in the active group fell from 458,518 during the baseline period to 417,078 during the intervention. But in the control group, the number of tests rose from 142,196 to 149,455 during the study period.

Investigator Doesn't Find Results Surprising

Dr. Leonard Feldman, one of the study investigators and who is in the department of medicine at Johns Hopkins, said the results did not come as a surprise.

"I think many of us do recognize that a lot of these tests and imaging studies that are done are unnecessary," Dr. Feldman said during the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Physicians order unnecessary tests for a number of reasons, he said, ranging from defensive medicine to patient expectations. But another reason is a lack of awareness of how much the tests cost, he said. "We, as doctors, have a limited understanding of diagnostic and nondrug therapeutic costs," Dr. Feldman said. "We just have no idea, mostly, how much things cost when we go to order them."

Study Limitations

While the study appears to show a relatively simple and inexpensive way to reduce the ordering of tests, Dr. Feldman acknowledged that the study had some limitations. For example, the study looked at only costs and did not include data on how the change in orders might have affected patient outcomes. And the intervention period was only 6 months.

Dr. Feldman said more time would be needed to show whether physicians would begin to ignore the costs over time. Similarly, costs were only displayed for 31 tests during the study. It's unclear if displaying all laboratory test costs would have the same effect on behavior, Dr. Feldman said.

The authors reported no financial disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOCIETY OF HOSPITAL MEDICINE

Major Finding: Displaying laboratory cost data for 6 months resulted in a savings of $15,692 per test, a 10% reduction from baseline. Control tests increased by about $1,718 per test.

Data Source: Laboratory cost data from Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Md.

Disclosures: The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.