User login

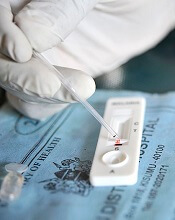

A large study suggests the use of rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) for malaria can reduce overuse of artemisinin combination therapies (ACTs), but malaria may also go untreated.

Researchers analyzed data from more than 500,000 patient visits across malaria-endemic regions of Africa and Afghanistan.

They found that, in most settings, the introduction of RDTs improved antimalarial targeting.

However, a substantial number of patients who tested positive for malaria appeared to go untreated, and negative test results prompted a shift to antibiotic prescriptions.

Katia Bruxvoort, PhD, of London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine in the UK, and her colleagues reported these results in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.

The researchers analyzed drug prescriptions written from 2007 to 2013 in 562,368 patient encounters documented in 10 related studies. Eight studies were conducted in sub-Saharan Africa (Cameroon, Ghana, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Uganda), and 2 were conducted in Afghanistan.

Overall, RDTs appeared to limit—though not eliminate—routine prescription of ACTs to patients presenting with fever but not malaria.

In most cases, fewer than 30% of patients who tested negative for malaria still received ACTs. However, in Cameroon and Ghana, 39% to 49% of patients who tested negative for malaria received ACTs.

“[I]n many places, a reduction in the use of ACTs was accompanied by an increase in the use of antibiotics, which may drive up the risk of antibiotic-resistant infections,” Dr Bruxvoort noted.

Overall, 75% of patients studied left the clinic with either an antibiotic or an ACT.

In most areas studied, antibiotics were given to 40% to 80% of patients who had tested negative for malaria.

The researchers believe the shift to antibiotic use after ruling out malaria may indicate that many patients and providers are not comfortable treating a fever using only supportive care (taking a fever-reducing drug and drinking plenty of fluids).

“A key challenge is that we don’t currently have a reliable way to determine which fevers are evidence of a bacterial infection that requires a specific antibiotic treatment and which fevers will resolve with supportive care only,” Dr Bruxvoort said.

In addition, Dr Bruxvoort and her colleagues were surprised to find that, in 5 of the 8 African studies, more than 20% of patients who tested positive for malaria were not prescribed ACTs.

“Drug supply issues did not seem to be a problem in most of the areas where these patients sought treatment,” Dr Bruxvoort said. “There might be other reasons either patients or providers are not using ACTs in these contexts, but the issue of undertreating malaria, even when there is clear evidence of the disease, is troubling and deserves further study.” ![]()

A large study suggests the use of rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) for malaria can reduce overuse of artemisinin combination therapies (ACTs), but malaria may also go untreated.

Researchers analyzed data from more than 500,000 patient visits across malaria-endemic regions of Africa and Afghanistan.

They found that, in most settings, the introduction of RDTs improved antimalarial targeting.

However, a substantial number of patients who tested positive for malaria appeared to go untreated, and negative test results prompted a shift to antibiotic prescriptions.

Katia Bruxvoort, PhD, of London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine in the UK, and her colleagues reported these results in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.

The researchers analyzed drug prescriptions written from 2007 to 2013 in 562,368 patient encounters documented in 10 related studies. Eight studies were conducted in sub-Saharan Africa (Cameroon, Ghana, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Uganda), and 2 were conducted in Afghanistan.

Overall, RDTs appeared to limit—though not eliminate—routine prescription of ACTs to patients presenting with fever but not malaria.

In most cases, fewer than 30% of patients who tested negative for malaria still received ACTs. However, in Cameroon and Ghana, 39% to 49% of patients who tested negative for malaria received ACTs.

“[I]n many places, a reduction in the use of ACTs was accompanied by an increase in the use of antibiotics, which may drive up the risk of antibiotic-resistant infections,” Dr Bruxvoort noted.

Overall, 75% of patients studied left the clinic with either an antibiotic or an ACT.

In most areas studied, antibiotics were given to 40% to 80% of patients who had tested negative for malaria.

The researchers believe the shift to antibiotic use after ruling out malaria may indicate that many patients and providers are not comfortable treating a fever using only supportive care (taking a fever-reducing drug and drinking plenty of fluids).

“A key challenge is that we don’t currently have a reliable way to determine which fevers are evidence of a bacterial infection that requires a specific antibiotic treatment and which fevers will resolve with supportive care only,” Dr Bruxvoort said.

In addition, Dr Bruxvoort and her colleagues were surprised to find that, in 5 of the 8 African studies, more than 20% of patients who tested positive for malaria were not prescribed ACTs.

“Drug supply issues did not seem to be a problem in most of the areas where these patients sought treatment,” Dr Bruxvoort said. “There might be other reasons either patients or providers are not using ACTs in these contexts, but the issue of undertreating malaria, even when there is clear evidence of the disease, is troubling and deserves further study.” ![]()

A large study suggests the use of rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) for malaria can reduce overuse of artemisinin combination therapies (ACTs), but malaria may also go untreated.

Researchers analyzed data from more than 500,000 patient visits across malaria-endemic regions of Africa and Afghanistan.

They found that, in most settings, the introduction of RDTs improved antimalarial targeting.

However, a substantial number of patients who tested positive for malaria appeared to go untreated, and negative test results prompted a shift to antibiotic prescriptions.

Katia Bruxvoort, PhD, of London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine in the UK, and her colleagues reported these results in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.

The researchers analyzed drug prescriptions written from 2007 to 2013 in 562,368 patient encounters documented in 10 related studies. Eight studies were conducted in sub-Saharan Africa (Cameroon, Ghana, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Uganda), and 2 were conducted in Afghanistan.

Overall, RDTs appeared to limit—though not eliminate—routine prescription of ACTs to patients presenting with fever but not malaria.

In most cases, fewer than 30% of patients who tested negative for malaria still received ACTs. However, in Cameroon and Ghana, 39% to 49% of patients who tested negative for malaria received ACTs.

“[I]n many places, a reduction in the use of ACTs was accompanied by an increase in the use of antibiotics, which may drive up the risk of antibiotic-resistant infections,” Dr Bruxvoort noted.

Overall, 75% of patients studied left the clinic with either an antibiotic or an ACT.

In most areas studied, antibiotics were given to 40% to 80% of patients who had tested negative for malaria.

The researchers believe the shift to antibiotic use after ruling out malaria may indicate that many patients and providers are not comfortable treating a fever using only supportive care (taking a fever-reducing drug and drinking plenty of fluids).

“A key challenge is that we don’t currently have a reliable way to determine which fevers are evidence of a bacterial infection that requires a specific antibiotic treatment and which fevers will resolve with supportive care only,” Dr Bruxvoort said.

In addition, Dr Bruxvoort and her colleagues were surprised to find that, in 5 of the 8 African studies, more than 20% of patients who tested positive for malaria were not prescribed ACTs.

“Drug supply issues did not seem to be a problem in most of the areas where these patients sought treatment,” Dr Bruxvoort said. “There might be other reasons either patients or providers are not using ACTs in these contexts, but the issue of undertreating malaria, even when there is clear evidence of the disease, is troubling and deserves further study.” ![]()