User login

SAN DIEGO – A surgical team was forced to perform a delicate oral procedure on a rocking yacht while making sure to preserve presidential whiskers. A domineering doctor ignored fellow physicians while a president spent months dying in agony. And, after helping to save the leader of the free world, the leader of the American College of Surgeons found himself viciously attacked by his own colleagues.

When a quartet of ill U.S. presidents developed major medical problems, an audience at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons learned, their treating physicians ended up with major headaches of their own.

President Grover Cleveland, for example, required his surgical team to remove an oral tumor in total secrecy in 1893, robbing him of a big chunk of his upper palate. “The president had a mustache, and the mustache had to be left alone, and there could be no scars,” said the Hospital for Special Surgery’s J. Patrick O’Leary, MD, FACS, who spoke in a session focused on the history of presidential medicine.

The only light came from a single incandescent bulb, and the procedure was performed at sea, on a yacht anchored off Long Island, N.Y.

“If you were presented with these parameters as a surgeon today, my guess is that you would have demurred on taking on this project,” Dr. O’Leary said. “It was a prescription for a disaster.”

President Cleveland survived for another 15 years. James Garfield, a fellow Civil War veteran, wasn’t so fortunate. In 1881, he was astonishingly unlucky, the unwitting victim of a fumbling physician who dominated his care after an assassin shot him in the chest.

That physician, Willard Bliss, MD, dismissed other doctors who knew the president well and isolated this gregarious man from friends and family. He also ignored emerging knowledge about germ control. And he fed Garfield a heavy diet that the digestively sensitive president probably couldn’t have tolerated in the best of times. The result: endless vomiting, the loss of almost 80 pounds, and an unsuccessful rectal feeding regimen.

Toward the end of the president’s gruesome summer-long decline, Dr. Bliss told all but two doctors to stay away, John B. Hanks, MD, of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, said in his presentation. Then the president died of a wound that Dr. Hanks said would have been survivable with proper care even in the 1880s.

History has been unkind to Dr. Bliss, in part because his patient died. But another presidential physician faced bizarre post surgery scorn from his ACS colleagues, even though his patient lived, according to Justin Barr, MD, PhD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C.

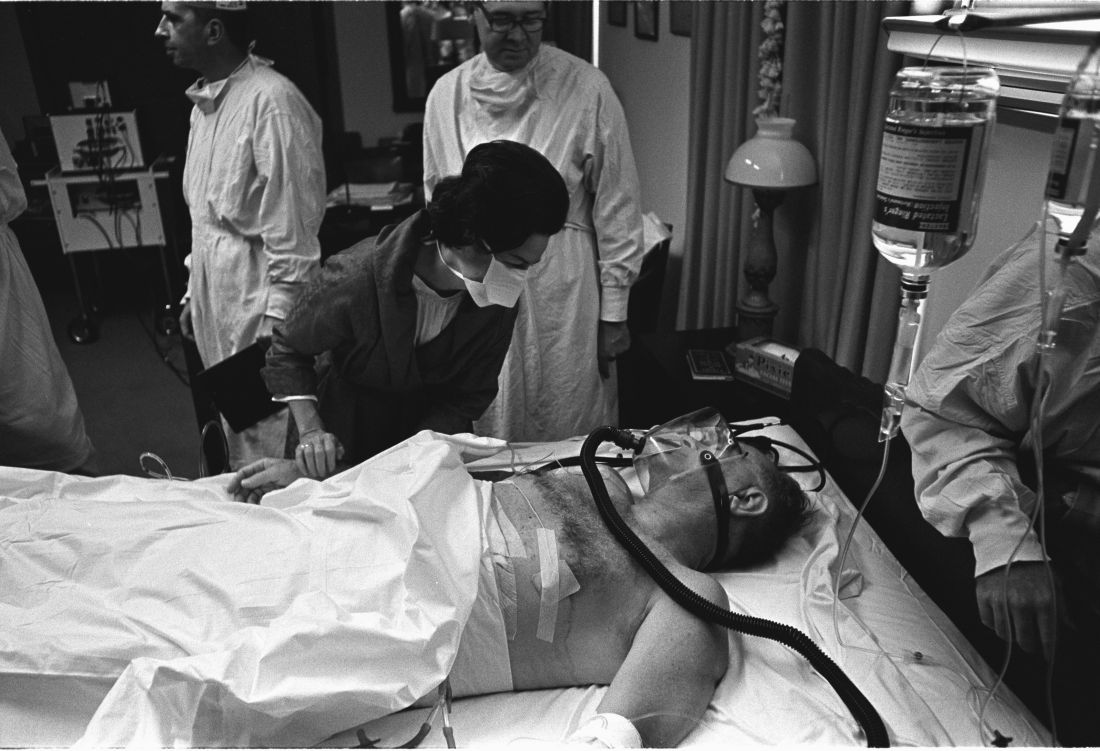

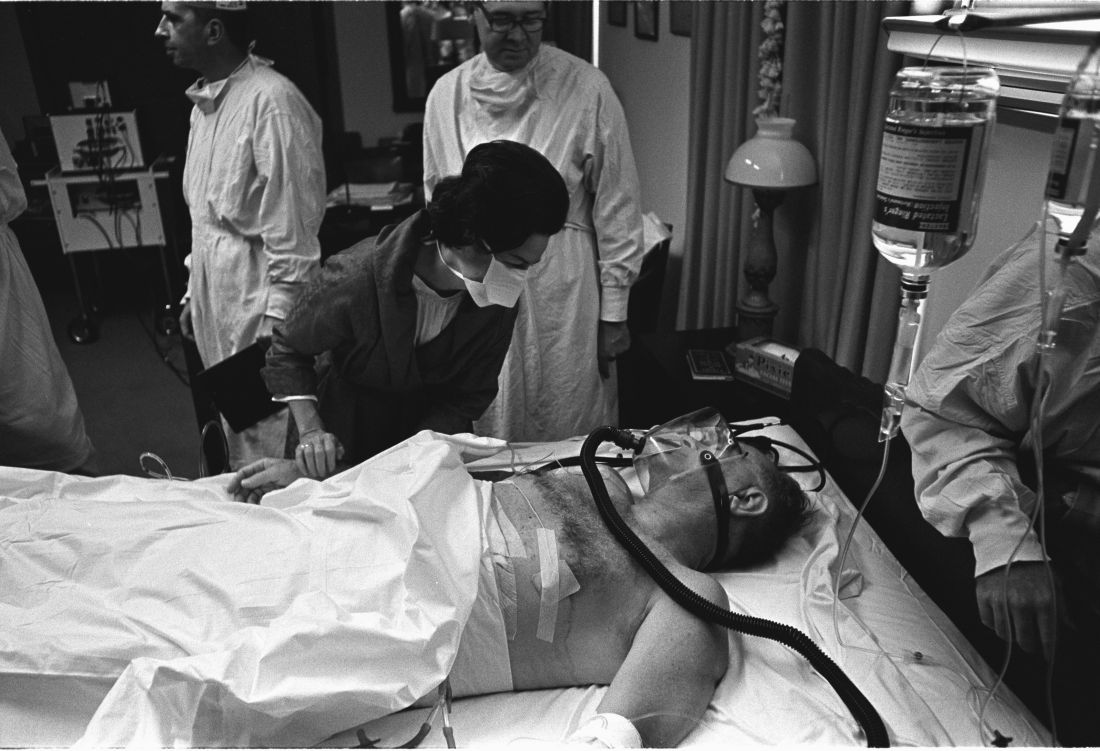

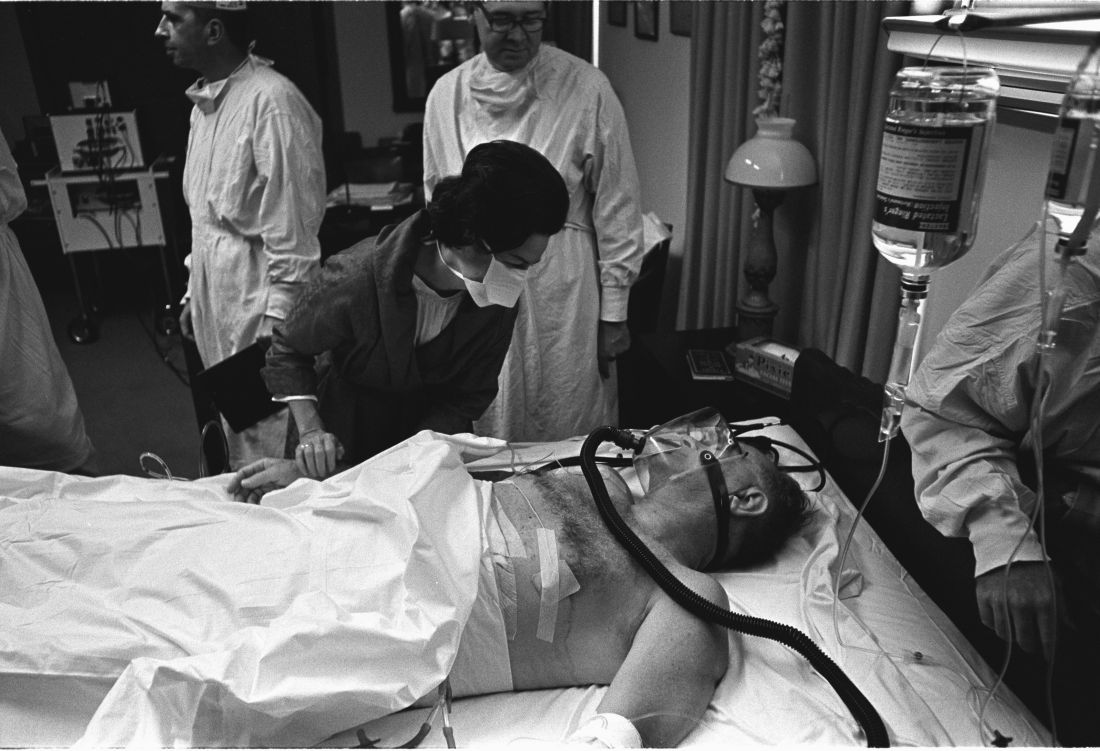

In 1956, surgeon Isidor Ravdin, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, was called in when President Dwight D. Eisenhower needed surgery to eliminate a bowel obstruction.

A team of physicians agreed that the president needed surgery. “They felt they were dealing with an elderly, sick patient who’d been in shock during his illness and had recently suffered a myocardial infarction,” Dr. Barr said. “They unanimously decided to proceed with a bypass over resection.”

It’s clear today that the physicians made the correct choice, Dr. Barr said. But his colleagues attacked Dr. Ravdin, who later complained that criticisms multiplied in direct ratio to distance from the operating room.

At the time, Dr. Ravdin was chair of the ACS Board of Regents. The entire board accused him of violating college policies regarding “ghost surgery” (performing procedures without the patient’s knowledge) and “itinerant surgery” (traveling to perform a procedure and then leaving).

Dr. Ravdin acknowledged that he had performed itinerant surgery to some extent, but he denied the ghost surgery charge. In fact, he and the president became friends.

His colleagues also attacked him over his decision to not perform a resection procedure. “They were accusing him of not only being an unethical surgeon, but also an incompetent one,” said Dr. Barr, who calls the letters about the allegations “truly bewildering.”

Also bewildering: Lyndon B. Johnson’s choice to display his gallbladder surgery scar to the press in 1965, spawning one of the most infamous photos of his presidency.

Few surgeons see their handiwork so prominently displayed. Fortunately for them, the operating theater was in a naval hospital, not on a boat. And, as far as we know, no one fretted over the fate of a single facial hair.

SAN DIEGO – A surgical team was forced to perform a delicate oral procedure on a rocking yacht while making sure to preserve presidential whiskers. A domineering doctor ignored fellow physicians while a president spent months dying in agony. And, after helping to save the leader of the free world, the leader of the American College of Surgeons found himself viciously attacked by his own colleagues.

When a quartet of ill U.S. presidents developed major medical problems, an audience at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons learned, their treating physicians ended up with major headaches of their own.

President Grover Cleveland, for example, required his surgical team to remove an oral tumor in total secrecy in 1893, robbing him of a big chunk of his upper palate. “The president had a mustache, and the mustache had to be left alone, and there could be no scars,” said the Hospital for Special Surgery’s J. Patrick O’Leary, MD, FACS, who spoke in a session focused on the history of presidential medicine.

The only light came from a single incandescent bulb, and the procedure was performed at sea, on a yacht anchored off Long Island, N.Y.

“If you were presented with these parameters as a surgeon today, my guess is that you would have demurred on taking on this project,” Dr. O’Leary said. “It was a prescription for a disaster.”

President Cleveland survived for another 15 years. James Garfield, a fellow Civil War veteran, wasn’t so fortunate. In 1881, he was astonishingly unlucky, the unwitting victim of a fumbling physician who dominated his care after an assassin shot him in the chest.

That physician, Willard Bliss, MD, dismissed other doctors who knew the president well and isolated this gregarious man from friends and family. He also ignored emerging knowledge about germ control. And he fed Garfield a heavy diet that the digestively sensitive president probably couldn’t have tolerated in the best of times. The result: endless vomiting, the loss of almost 80 pounds, and an unsuccessful rectal feeding regimen.

Toward the end of the president’s gruesome summer-long decline, Dr. Bliss told all but two doctors to stay away, John B. Hanks, MD, of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, said in his presentation. Then the president died of a wound that Dr. Hanks said would have been survivable with proper care even in the 1880s.

History has been unkind to Dr. Bliss, in part because his patient died. But another presidential physician faced bizarre post surgery scorn from his ACS colleagues, even though his patient lived, according to Justin Barr, MD, PhD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C.

In 1956, surgeon Isidor Ravdin, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, was called in when President Dwight D. Eisenhower needed surgery to eliminate a bowel obstruction.

A team of physicians agreed that the president needed surgery. “They felt they were dealing with an elderly, sick patient who’d been in shock during his illness and had recently suffered a myocardial infarction,” Dr. Barr said. “They unanimously decided to proceed with a bypass over resection.”

It’s clear today that the physicians made the correct choice, Dr. Barr said. But his colleagues attacked Dr. Ravdin, who later complained that criticisms multiplied in direct ratio to distance from the operating room.

At the time, Dr. Ravdin was chair of the ACS Board of Regents. The entire board accused him of violating college policies regarding “ghost surgery” (performing procedures without the patient’s knowledge) and “itinerant surgery” (traveling to perform a procedure and then leaving).

Dr. Ravdin acknowledged that he had performed itinerant surgery to some extent, but he denied the ghost surgery charge. In fact, he and the president became friends.

His colleagues also attacked him over his decision to not perform a resection procedure. “They were accusing him of not only being an unethical surgeon, but also an incompetent one,” said Dr. Barr, who calls the letters about the allegations “truly bewildering.”

Also bewildering: Lyndon B. Johnson’s choice to display his gallbladder surgery scar to the press in 1965, spawning one of the most infamous photos of his presidency.

Few surgeons see their handiwork so prominently displayed. Fortunately for them, the operating theater was in a naval hospital, not on a boat. And, as far as we know, no one fretted over the fate of a single facial hair.

SAN DIEGO – A surgical team was forced to perform a delicate oral procedure on a rocking yacht while making sure to preserve presidential whiskers. A domineering doctor ignored fellow physicians while a president spent months dying in agony. And, after helping to save the leader of the free world, the leader of the American College of Surgeons found himself viciously attacked by his own colleagues.

When a quartet of ill U.S. presidents developed major medical problems, an audience at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons learned, their treating physicians ended up with major headaches of their own.

President Grover Cleveland, for example, required his surgical team to remove an oral tumor in total secrecy in 1893, robbing him of a big chunk of his upper palate. “The president had a mustache, and the mustache had to be left alone, and there could be no scars,” said the Hospital for Special Surgery’s J. Patrick O’Leary, MD, FACS, who spoke in a session focused on the history of presidential medicine.

The only light came from a single incandescent bulb, and the procedure was performed at sea, on a yacht anchored off Long Island, N.Y.

“If you were presented with these parameters as a surgeon today, my guess is that you would have demurred on taking on this project,” Dr. O’Leary said. “It was a prescription for a disaster.”

President Cleveland survived for another 15 years. James Garfield, a fellow Civil War veteran, wasn’t so fortunate. In 1881, he was astonishingly unlucky, the unwitting victim of a fumbling physician who dominated his care after an assassin shot him in the chest.

That physician, Willard Bliss, MD, dismissed other doctors who knew the president well and isolated this gregarious man from friends and family. He also ignored emerging knowledge about germ control. And he fed Garfield a heavy diet that the digestively sensitive president probably couldn’t have tolerated in the best of times. The result: endless vomiting, the loss of almost 80 pounds, and an unsuccessful rectal feeding regimen.

Toward the end of the president’s gruesome summer-long decline, Dr. Bliss told all but two doctors to stay away, John B. Hanks, MD, of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, said in his presentation. Then the president died of a wound that Dr. Hanks said would have been survivable with proper care even in the 1880s.

History has been unkind to Dr. Bliss, in part because his patient died. But another presidential physician faced bizarre post surgery scorn from his ACS colleagues, even though his patient lived, according to Justin Barr, MD, PhD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C.

In 1956, surgeon Isidor Ravdin, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, was called in when President Dwight D. Eisenhower needed surgery to eliminate a bowel obstruction.

A team of physicians agreed that the president needed surgery. “They felt they were dealing with an elderly, sick patient who’d been in shock during his illness and had recently suffered a myocardial infarction,” Dr. Barr said. “They unanimously decided to proceed with a bypass over resection.”

It’s clear today that the physicians made the correct choice, Dr. Barr said. But his colleagues attacked Dr. Ravdin, who later complained that criticisms multiplied in direct ratio to distance from the operating room.

At the time, Dr. Ravdin was chair of the ACS Board of Regents. The entire board accused him of violating college policies regarding “ghost surgery” (performing procedures without the patient’s knowledge) and “itinerant surgery” (traveling to perform a procedure and then leaving).

Dr. Ravdin acknowledged that he had performed itinerant surgery to some extent, but he denied the ghost surgery charge. In fact, he and the president became friends.

His colleagues also attacked him over his decision to not perform a resection procedure. “They were accusing him of not only being an unethical surgeon, but also an incompetent one,” said Dr. Barr, who calls the letters about the allegations “truly bewildering.”

Also bewildering: Lyndon B. Johnson’s choice to display his gallbladder surgery scar to the press in 1965, spawning one of the most infamous photos of his presidency.

Few surgeons see their handiwork so prominently displayed. Fortunately for them, the operating theater was in a naval hospital, not on a boat. And, as far as we know, no one fretted over the fate of a single facial hair.

AT THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS