User login

Joint mice or loose/rice bodies are infrequently encountered within joints. Usually, they are either fibrin or cartilaginous. The fibrin type, typically results from bleeding within a joint from synovitis, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), or tuberculosis, and the cartilaginous/osteocartilaginous type develop from trauma or osteoarthritis.1 A rare cause of osteocartilaginous joint mice is synovial chondromatosis(SC), which can produce multiple loose bodies that originate from the synovial membranes of joints, bursae, and tendon sheaths of large joints; the knee being the most common (50%-65 % of cases).1,2

A case of a male who had multiple years of left knee pain and swelling without a documented traumatic cause is presented

Case Presentation

A 34-year-old male veteran was evaluated and treated in a VA orthopedic outpatient clinic by a physician assistant for anterior left knee pain and swelling of insidious onset that had persisted for 1.5 years. The patient reported experiencing no trauma. His primary care provider already was treating the patient with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), icing, and bracing. He had full motion in his knee with extension/flexion 0° to 130°. Collateral and cruciate ligaments were stable. He had a positive McMurray test. The X-rays showed no pathology. Due to the positive meniscal tear signs, a magnetic resonance image (MRI) was ordered.

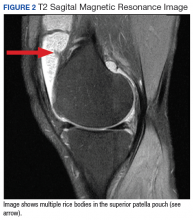

The patient was intermittently nonadherent with follow-up care. The MRI results were available at a subsequent appointment 3 months after the index evaluation, which revealed a large joint effusion with rice bodies, small erosion of the posterior tibialplateau, and synovial proliferation of the anterior knee joint. A steroid injection to his affected knee was given. Concerns for possible RA led to a workup. The laboratory results included rheumatoid factor (weakly positive), antinuclear-antibodies (negative), human immunodeficiency virus (positivewith western blot negative), C-reactive protein (< 0.02 mg/L), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (5 mm/h), white blood cell count (4.6 µL), hepatitis B surface antigen (reactive), hepatitis A antibody (IgG reactive), synovial fluid cultures, and Gram stain (negative).

The patient saw a rheumatologist 7 months after a RA referral was processed. The consulting rheumatologist was unconcerned by a weakly positive rheumatoid factor, which was later repeated and was negative. The rheumatologist excluded the possibility of RA, and the patient was diagnosed with oligoarthritis. The treatment rendered was to continue NSAIDs and to return to the orthopedic clinic for continued care.

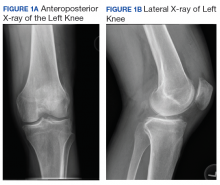

The patient had irregular follow-up visits where he received multiple methylprednisolone acetate intra-articular injections. His motion regressed until extension/flexion had decreased to 5°/85°. At this point the patient was forwarded to an operative orthopedic surgeon for evaluation for surgical intervention. Recent anteroposterior and lateral left knee X-rays showed faint intra-articular calcification, joint effusion, with mild arthritic changes of the patellofemoral joint (Figures 1A and 1B).

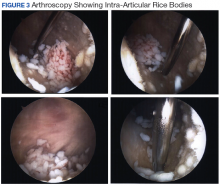

At surgery, on placing the infralateral portal, clear straw-colored fluid exited the cannula followed by copious small white rice bodies, which were sent to pathology for evaluation. The knee was surgically evaluated, and extensive rice bodies were encountered (Figure 3). These were extracted with a full radius shaver. The chondral surfaces were inspected. There were no arthritic changes, but the synovial lining of the joint was hypertrophied and reactive (Milgram phase 2). After all loose bodies were extracted, the patient’s incisions were closed with nylon suture, and he was placed in sterile dressings with a postoperative range of motion brace.

The patient presented for his routine postoperative visit 14 days after surgery. Pathology results showed synociocytes, and inflammatory cells were negative for malignancy. The patient was forwarded to a local hospital for further evaluation and treatment by an orthopedic oncologist due to a reported 5% chance of malignant transformation.1-3

Discussion

Synovial chondromatosis or osteochondromatosis is a rare, benign, metaplastic, typically monoarticular disorder of the synovial lining of joints, bursae, and synovial sheaths, usually affecting large joints.1-5 Although any joint can be involved, such as metacarpalphalangeal joints, temporomandibular joints, distal radio-ulnar joints, and the hips, the knee is the most common with an occurrence rate 50% to 65%.3-5 Extra-articular proliferation can be seen in cases of osteochondromatosis.2 It is characterized by the formation of intra-articular nodules of the synovium that can detach and become loose bodies, which can secondarily become calcified/ossified.4,6 The differential diagnosis associated with SC should include synovial hemangioma, pigmented villonodular synovitis, synovial cyst, lipoma arborescence, and malignancies, such as synovial chondrosarcoma or synovial sarcoma.3

Men are affected twice as much as are women, usually in the fourth through sixth decades of life, and a mean age of 47.7 years.1,3-5,7,8 The SC occurrence rate in adults is 1:100,000.2 Patients typically present with insidious gradual mechanical symptoms, such as pain (> 85% of cases), swelling (42%-58%), and decreased motion (38%-55%) in the affected joint.2,3,6 Often there is crepitus with motion, diffuse tenderness, effusion, and occasionally nodules can be palpated.2,3 Histologically, the synovium exhibits condrocytic metaplasia of fibroblasts with influence from transforming growth factor-β and bone morphogenic proteins.1,4

Synovial chondromatosis can mimic osteoarthritis or meniscal pathology.3 Because of a chance of malignant transformation, any patient with rapid late deterioration of clinical features should be evaluated for chondrosarcoma or synovial sarcoma.1-4 Plain radiographs may help differentiate the cause showing calcific joint mice and peri-articular erosions. However, the intra-articular loose bodies are frequently radiolucent, and a MRI may be warranted to definitively differentiate the diagnosis.2,7,8

Loose bodies tend to exhibit a low signal on T1-weighted images and a high signal on T2-weighted images, although there may a be low signal on all images where there is extensive calcification of the loose bodies.2 Ultrasound also is a useful diagnostic tool that can show numerous echogenic bodies, effusion, and synovial hypertrophy.2

A classic article by Milgram discussed the phases of the proliferative changes associated with SC, where phase 1 shows active intrasynovial disease with no loose bodies.9 Phase 2 has transitional lesions with osteochondral nodules within the synovial membrane and free bodies within the joint cavity. Last, in phase 3, there are multiple osteochondral free bodies but quiescent intrasynovial disease. The patient in this case study exhibited intra-articular activity mimicking phase 2 with extensive intra-articular loose bodies and reactive synovial lining.3,9

In the early phase of the disease, conservative management may be trialed with NSAIDs, bracing, and injections, but typically surgical intervention is warranted after free bodies are found present, because they limit motion and cause recalcitrant swelling.2,8 There is a controversy whether arthroscopic removal of loose bodies or excision with synovectomy is the treatment of choice.6 Ogilvie-Harris and colleagues reviewed the results of both procedures and found that although removal of loose bodies alone may be sufficient, there is the potential for recurrence.9,10 In order to reduce potential recurrence, removal of loose bodies with anterior and posterior synovectomy is the treatment of choice.9

If arthroscopic removal of loose bodies without synovectomy is performed, then the patient should be followed closely for recurrence, which Jesalpura and colleagues reported to occur for 11.5% of patients.9,11 If there is a reappearance, then a synovectomy should be performed.10 A recommended treatment option for recalcitrant SC is radiation, but this carries the added risk of perpetuating malignant transformation.1,7

Unfortunately, osteoarthritis can be a significant long-term postoperative adverse effect.3,6-8 This typically is related to the amount of articular damage that is present at surgery. Many times, the arthritis becomes significant enough to require total joint arthroplasty.4 Close long-term follow-up is recommended, because although rare, there is a chance of malignant change.1-4

Conclusion

Synovial chondromatosis is an uncommon cause of knee pain and swelling and should be included in the differential diagnosis when evaluating any adult aged 30 years to 50 years with knee pain of insidious onset. Appropriate workup, intervention, and treatment will allow final diagnosis and correlating care to be administered to the patient.

1. Libbey NP, Mirrer F. Synovial chondromatosis. Med Health R I. 2011;94(9):274-275.

2. Giancane G, Tanturri de Horatio L, Buonuomo PS, Barbuti D, Lais G, Cortis E. Swollen knee due to primary synovial chondromatosis in pediatrics: a rare and possibly misdiagnosed condition. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33(8):2183-2185.

3. Serbest S, Tiftikçi U, Karaaslan F, Tosun HB, Sevinç HF, Balci M. A neglected case of giant synovial chondromatosis in knee joint. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;22:5.

4. Hallam P, Ashwood N, Cobb J, Fazal A, Heatley W. Malignant transformation in synovial chondromatosis of the knee? Knee. 2001;8(3):239-242.

5. Pimentel Cde Q, Hoff LS, de Sousa LF, Cordeiro RA, Pereira RM. Primary synovial osteochondromatosis of the knee. Rheumatol (Oxford). 2015;54(10):1815.

6. Damron TA, Sim FH. Soft-tissue tumors about the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1997;5(3):141-152.

7. Krych A, Odland A, Rose P, et al. Onconlogic conditions that simulate common sports injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(4):223-234.

8. Adelani MA, Wupperman RM, Holt GE. Benign synovial disorders. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(5):268-275.

9. Migram JW. Synovial osteochondromatosis: a histopathological study of thirty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(6):792-801.

10. Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Saleh K. Generalized synovial chondromatosis of the knee: a comparison of removal of the loose bodies alone with arthroscopic synovectomy. Arthroscopy.1994;10(2):166-170.

11. Jesalpura JP, Chung HW, Patnaik S, Choi HW, Kim JI, Nha KW. Athroscopic treatment of localized synovial chondromatosis of the posterior knee joint. Orthopedics. 2010;33(1):49

Joint mice or loose/rice bodies are infrequently encountered within joints. Usually, they are either fibrin or cartilaginous. The fibrin type, typically results from bleeding within a joint from synovitis, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), or tuberculosis, and the cartilaginous/osteocartilaginous type develop from trauma or osteoarthritis.1 A rare cause of osteocartilaginous joint mice is synovial chondromatosis(SC), which can produce multiple loose bodies that originate from the synovial membranes of joints, bursae, and tendon sheaths of large joints; the knee being the most common (50%-65 % of cases).1,2

A case of a male who had multiple years of left knee pain and swelling without a documented traumatic cause is presented

Case Presentation

A 34-year-old male veteran was evaluated and treated in a VA orthopedic outpatient clinic by a physician assistant for anterior left knee pain and swelling of insidious onset that had persisted for 1.5 years. The patient reported experiencing no trauma. His primary care provider already was treating the patient with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), icing, and bracing. He had full motion in his knee with extension/flexion 0° to 130°. Collateral and cruciate ligaments were stable. He had a positive McMurray test. The X-rays showed no pathology. Due to the positive meniscal tear signs, a magnetic resonance image (MRI) was ordered.

The patient was intermittently nonadherent with follow-up care. The MRI results were available at a subsequent appointment 3 months after the index evaluation, which revealed a large joint effusion with rice bodies, small erosion of the posterior tibialplateau, and synovial proliferation of the anterior knee joint. A steroid injection to his affected knee was given. Concerns for possible RA led to a workup. The laboratory results included rheumatoid factor (weakly positive), antinuclear-antibodies (negative), human immunodeficiency virus (positivewith western blot negative), C-reactive protein (< 0.02 mg/L), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (5 mm/h), white blood cell count (4.6 µL), hepatitis B surface antigen (reactive), hepatitis A antibody (IgG reactive), synovial fluid cultures, and Gram stain (negative).

The patient saw a rheumatologist 7 months after a RA referral was processed. The consulting rheumatologist was unconcerned by a weakly positive rheumatoid factor, which was later repeated and was negative. The rheumatologist excluded the possibility of RA, and the patient was diagnosed with oligoarthritis. The treatment rendered was to continue NSAIDs and to return to the orthopedic clinic for continued care.

The patient had irregular follow-up visits where he received multiple methylprednisolone acetate intra-articular injections. His motion regressed until extension/flexion had decreased to 5°/85°. At this point the patient was forwarded to an operative orthopedic surgeon for evaluation for surgical intervention. Recent anteroposterior and lateral left knee X-rays showed faint intra-articular calcification, joint effusion, with mild arthritic changes of the patellofemoral joint (Figures 1A and 1B).

At surgery, on placing the infralateral portal, clear straw-colored fluid exited the cannula followed by copious small white rice bodies, which were sent to pathology for evaluation. The knee was surgically evaluated, and extensive rice bodies were encountered (Figure 3). These were extracted with a full radius shaver. The chondral surfaces were inspected. There were no arthritic changes, but the synovial lining of the joint was hypertrophied and reactive (Milgram phase 2). After all loose bodies were extracted, the patient’s incisions were closed with nylon suture, and he was placed in sterile dressings with a postoperative range of motion brace.

The patient presented for his routine postoperative visit 14 days after surgery. Pathology results showed synociocytes, and inflammatory cells were negative for malignancy. The patient was forwarded to a local hospital for further evaluation and treatment by an orthopedic oncologist due to a reported 5% chance of malignant transformation.1-3

Discussion

Synovial chondromatosis or osteochondromatosis is a rare, benign, metaplastic, typically monoarticular disorder of the synovial lining of joints, bursae, and synovial sheaths, usually affecting large joints.1-5 Although any joint can be involved, such as metacarpalphalangeal joints, temporomandibular joints, distal radio-ulnar joints, and the hips, the knee is the most common with an occurrence rate 50% to 65%.3-5 Extra-articular proliferation can be seen in cases of osteochondromatosis.2 It is characterized by the formation of intra-articular nodules of the synovium that can detach and become loose bodies, which can secondarily become calcified/ossified.4,6 The differential diagnosis associated with SC should include synovial hemangioma, pigmented villonodular synovitis, synovial cyst, lipoma arborescence, and malignancies, such as synovial chondrosarcoma or synovial sarcoma.3

Men are affected twice as much as are women, usually in the fourth through sixth decades of life, and a mean age of 47.7 years.1,3-5,7,8 The SC occurrence rate in adults is 1:100,000.2 Patients typically present with insidious gradual mechanical symptoms, such as pain (> 85% of cases), swelling (42%-58%), and decreased motion (38%-55%) in the affected joint.2,3,6 Often there is crepitus with motion, diffuse tenderness, effusion, and occasionally nodules can be palpated.2,3 Histologically, the synovium exhibits condrocytic metaplasia of fibroblasts with influence from transforming growth factor-β and bone morphogenic proteins.1,4

Synovial chondromatosis can mimic osteoarthritis or meniscal pathology.3 Because of a chance of malignant transformation, any patient with rapid late deterioration of clinical features should be evaluated for chondrosarcoma or synovial sarcoma.1-4 Plain radiographs may help differentiate the cause showing calcific joint mice and peri-articular erosions. However, the intra-articular loose bodies are frequently radiolucent, and a MRI may be warranted to definitively differentiate the diagnosis.2,7,8

Loose bodies tend to exhibit a low signal on T1-weighted images and a high signal on T2-weighted images, although there may a be low signal on all images where there is extensive calcification of the loose bodies.2 Ultrasound also is a useful diagnostic tool that can show numerous echogenic bodies, effusion, and synovial hypertrophy.2

A classic article by Milgram discussed the phases of the proliferative changes associated with SC, where phase 1 shows active intrasynovial disease with no loose bodies.9 Phase 2 has transitional lesions with osteochondral nodules within the synovial membrane and free bodies within the joint cavity. Last, in phase 3, there are multiple osteochondral free bodies but quiescent intrasynovial disease. The patient in this case study exhibited intra-articular activity mimicking phase 2 with extensive intra-articular loose bodies and reactive synovial lining.3,9

In the early phase of the disease, conservative management may be trialed with NSAIDs, bracing, and injections, but typically surgical intervention is warranted after free bodies are found present, because they limit motion and cause recalcitrant swelling.2,8 There is a controversy whether arthroscopic removal of loose bodies or excision with synovectomy is the treatment of choice.6 Ogilvie-Harris and colleagues reviewed the results of both procedures and found that although removal of loose bodies alone may be sufficient, there is the potential for recurrence.9,10 In order to reduce potential recurrence, removal of loose bodies with anterior and posterior synovectomy is the treatment of choice.9

If arthroscopic removal of loose bodies without synovectomy is performed, then the patient should be followed closely for recurrence, which Jesalpura and colleagues reported to occur for 11.5% of patients.9,11 If there is a reappearance, then a synovectomy should be performed.10 A recommended treatment option for recalcitrant SC is radiation, but this carries the added risk of perpetuating malignant transformation.1,7

Unfortunately, osteoarthritis can be a significant long-term postoperative adverse effect.3,6-8 This typically is related to the amount of articular damage that is present at surgery. Many times, the arthritis becomes significant enough to require total joint arthroplasty.4 Close long-term follow-up is recommended, because although rare, there is a chance of malignant change.1-4

Conclusion

Synovial chondromatosis is an uncommon cause of knee pain and swelling and should be included in the differential diagnosis when evaluating any adult aged 30 years to 50 years with knee pain of insidious onset. Appropriate workup, intervention, and treatment will allow final diagnosis and correlating care to be administered to the patient.

Joint mice or loose/rice bodies are infrequently encountered within joints. Usually, they are either fibrin or cartilaginous. The fibrin type, typically results from bleeding within a joint from synovitis, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), or tuberculosis, and the cartilaginous/osteocartilaginous type develop from trauma or osteoarthritis.1 A rare cause of osteocartilaginous joint mice is synovial chondromatosis(SC), which can produce multiple loose bodies that originate from the synovial membranes of joints, bursae, and tendon sheaths of large joints; the knee being the most common (50%-65 % of cases).1,2

A case of a male who had multiple years of left knee pain and swelling without a documented traumatic cause is presented

Case Presentation

A 34-year-old male veteran was evaluated and treated in a VA orthopedic outpatient clinic by a physician assistant for anterior left knee pain and swelling of insidious onset that had persisted for 1.5 years. The patient reported experiencing no trauma. His primary care provider already was treating the patient with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), icing, and bracing. He had full motion in his knee with extension/flexion 0° to 130°. Collateral and cruciate ligaments were stable. He had a positive McMurray test. The X-rays showed no pathology. Due to the positive meniscal tear signs, a magnetic resonance image (MRI) was ordered.

The patient was intermittently nonadherent with follow-up care. The MRI results were available at a subsequent appointment 3 months after the index evaluation, which revealed a large joint effusion with rice bodies, small erosion of the posterior tibialplateau, and synovial proliferation of the anterior knee joint. A steroid injection to his affected knee was given. Concerns for possible RA led to a workup. The laboratory results included rheumatoid factor (weakly positive), antinuclear-antibodies (negative), human immunodeficiency virus (positivewith western blot negative), C-reactive protein (< 0.02 mg/L), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (5 mm/h), white blood cell count (4.6 µL), hepatitis B surface antigen (reactive), hepatitis A antibody (IgG reactive), synovial fluid cultures, and Gram stain (negative).

The patient saw a rheumatologist 7 months after a RA referral was processed. The consulting rheumatologist was unconcerned by a weakly positive rheumatoid factor, which was later repeated and was negative. The rheumatologist excluded the possibility of RA, and the patient was diagnosed with oligoarthritis. The treatment rendered was to continue NSAIDs and to return to the orthopedic clinic for continued care.

The patient had irregular follow-up visits where he received multiple methylprednisolone acetate intra-articular injections. His motion regressed until extension/flexion had decreased to 5°/85°. At this point the patient was forwarded to an operative orthopedic surgeon for evaluation for surgical intervention. Recent anteroposterior and lateral left knee X-rays showed faint intra-articular calcification, joint effusion, with mild arthritic changes of the patellofemoral joint (Figures 1A and 1B).

At surgery, on placing the infralateral portal, clear straw-colored fluid exited the cannula followed by copious small white rice bodies, which were sent to pathology for evaluation. The knee was surgically evaluated, and extensive rice bodies were encountered (Figure 3). These were extracted with a full radius shaver. The chondral surfaces were inspected. There were no arthritic changes, but the synovial lining of the joint was hypertrophied and reactive (Milgram phase 2). After all loose bodies were extracted, the patient’s incisions were closed with nylon suture, and he was placed in sterile dressings with a postoperative range of motion brace.

The patient presented for his routine postoperative visit 14 days after surgery. Pathology results showed synociocytes, and inflammatory cells were negative for malignancy. The patient was forwarded to a local hospital for further evaluation and treatment by an orthopedic oncologist due to a reported 5% chance of malignant transformation.1-3

Discussion

Synovial chondromatosis or osteochondromatosis is a rare, benign, metaplastic, typically monoarticular disorder of the synovial lining of joints, bursae, and synovial sheaths, usually affecting large joints.1-5 Although any joint can be involved, such as metacarpalphalangeal joints, temporomandibular joints, distal radio-ulnar joints, and the hips, the knee is the most common with an occurrence rate 50% to 65%.3-5 Extra-articular proliferation can be seen in cases of osteochondromatosis.2 It is characterized by the formation of intra-articular nodules of the synovium that can detach and become loose bodies, which can secondarily become calcified/ossified.4,6 The differential diagnosis associated with SC should include synovial hemangioma, pigmented villonodular synovitis, synovial cyst, lipoma arborescence, and malignancies, such as synovial chondrosarcoma or synovial sarcoma.3

Men are affected twice as much as are women, usually in the fourth through sixth decades of life, and a mean age of 47.7 years.1,3-5,7,8 The SC occurrence rate in adults is 1:100,000.2 Patients typically present with insidious gradual mechanical symptoms, such as pain (> 85% of cases), swelling (42%-58%), and decreased motion (38%-55%) in the affected joint.2,3,6 Often there is crepitus with motion, diffuse tenderness, effusion, and occasionally nodules can be palpated.2,3 Histologically, the synovium exhibits condrocytic metaplasia of fibroblasts with influence from transforming growth factor-β and bone morphogenic proteins.1,4

Synovial chondromatosis can mimic osteoarthritis or meniscal pathology.3 Because of a chance of malignant transformation, any patient with rapid late deterioration of clinical features should be evaluated for chondrosarcoma or synovial sarcoma.1-4 Plain radiographs may help differentiate the cause showing calcific joint mice and peri-articular erosions. However, the intra-articular loose bodies are frequently radiolucent, and a MRI may be warranted to definitively differentiate the diagnosis.2,7,8

Loose bodies tend to exhibit a low signal on T1-weighted images and a high signal on T2-weighted images, although there may a be low signal on all images where there is extensive calcification of the loose bodies.2 Ultrasound also is a useful diagnostic tool that can show numerous echogenic bodies, effusion, and synovial hypertrophy.2

A classic article by Milgram discussed the phases of the proliferative changes associated with SC, where phase 1 shows active intrasynovial disease with no loose bodies.9 Phase 2 has transitional lesions with osteochondral nodules within the synovial membrane and free bodies within the joint cavity. Last, in phase 3, there are multiple osteochondral free bodies but quiescent intrasynovial disease. The patient in this case study exhibited intra-articular activity mimicking phase 2 with extensive intra-articular loose bodies and reactive synovial lining.3,9

In the early phase of the disease, conservative management may be trialed with NSAIDs, bracing, and injections, but typically surgical intervention is warranted after free bodies are found present, because they limit motion and cause recalcitrant swelling.2,8 There is a controversy whether arthroscopic removal of loose bodies or excision with synovectomy is the treatment of choice.6 Ogilvie-Harris and colleagues reviewed the results of both procedures and found that although removal of loose bodies alone may be sufficient, there is the potential for recurrence.9,10 In order to reduce potential recurrence, removal of loose bodies with anterior and posterior synovectomy is the treatment of choice.9

If arthroscopic removal of loose bodies without synovectomy is performed, then the patient should be followed closely for recurrence, which Jesalpura and colleagues reported to occur for 11.5% of patients.9,11 If there is a reappearance, then a synovectomy should be performed.10 A recommended treatment option for recalcitrant SC is radiation, but this carries the added risk of perpetuating malignant transformation.1,7

Unfortunately, osteoarthritis can be a significant long-term postoperative adverse effect.3,6-8 This typically is related to the amount of articular damage that is present at surgery. Many times, the arthritis becomes significant enough to require total joint arthroplasty.4 Close long-term follow-up is recommended, because although rare, there is a chance of malignant change.1-4

Conclusion

Synovial chondromatosis is an uncommon cause of knee pain and swelling and should be included in the differential diagnosis when evaluating any adult aged 30 years to 50 years with knee pain of insidious onset. Appropriate workup, intervention, and treatment will allow final diagnosis and correlating care to be administered to the patient.

1. Libbey NP, Mirrer F. Synovial chondromatosis. Med Health R I. 2011;94(9):274-275.

2. Giancane G, Tanturri de Horatio L, Buonuomo PS, Barbuti D, Lais G, Cortis E. Swollen knee due to primary synovial chondromatosis in pediatrics: a rare and possibly misdiagnosed condition. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33(8):2183-2185.

3. Serbest S, Tiftikçi U, Karaaslan F, Tosun HB, Sevinç HF, Balci M. A neglected case of giant synovial chondromatosis in knee joint. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;22:5.

4. Hallam P, Ashwood N, Cobb J, Fazal A, Heatley W. Malignant transformation in synovial chondromatosis of the knee? Knee. 2001;8(3):239-242.

5. Pimentel Cde Q, Hoff LS, de Sousa LF, Cordeiro RA, Pereira RM. Primary synovial osteochondromatosis of the knee. Rheumatol (Oxford). 2015;54(10):1815.

6. Damron TA, Sim FH. Soft-tissue tumors about the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1997;5(3):141-152.

7. Krych A, Odland A, Rose P, et al. Onconlogic conditions that simulate common sports injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(4):223-234.

8. Adelani MA, Wupperman RM, Holt GE. Benign synovial disorders. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(5):268-275.

9. Migram JW. Synovial osteochondromatosis: a histopathological study of thirty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(6):792-801.

10. Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Saleh K. Generalized synovial chondromatosis of the knee: a comparison of removal of the loose bodies alone with arthroscopic synovectomy. Arthroscopy.1994;10(2):166-170.

11. Jesalpura JP, Chung HW, Patnaik S, Choi HW, Kim JI, Nha KW. Athroscopic treatment of localized synovial chondromatosis of the posterior knee joint. Orthopedics. 2010;33(1):49

1. Libbey NP, Mirrer F. Synovial chondromatosis. Med Health R I. 2011;94(9):274-275.

2. Giancane G, Tanturri de Horatio L, Buonuomo PS, Barbuti D, Lais G, Cortis E. Swollen knee due to primary synovial chondromatosis in pediatrics: a rare and possibly misdiagnosed condition. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33(8):2183-2185.

3. Serbest S, Tiftikçi U, Karaaslan F, Tosun HB, Sevinç HF, Balci M. A neglected case of giant synovial chondromatosis in knee joint. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;22:5.

4. Hallam P, Ashwood N, Cobb J, Fazal A, Heatley W. Malignant transformation in synovial chondromatosis of the knee? Knee. 2001;8(3):239-242.

5. Pimentel Cde Q, Hoff LS, de Sousa LF, Cordeiro RA, Pereira RM. Primary synovial osteochondromatosis of the knee. Rheumatol (Oxford). 2015;54(10):1815.

6. Damron TA, Sim FH. Soft-tissue tumors about the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1997;5(3):141-152.

7. Krych A, Odland A, Rose P, et al. Onconlogic conditions that simulate common sports injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(4):223-234.

8. Adelani MA, Wupperman RM, Holt GE. Benign synovial disorders. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(5):268-275.

9. Migram JW. Synovial osteochondromatosis: a histopathological study of thirty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(6):792-801.

10. Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Saleh K. Generalized synovial chondromatosis of the knee: a comparison of removal of the loose bodies alone with arthroscopic synovectomy. Arthroscopy.1994;10(2):166-170.

11. Jesalpura JP, Chung HW, Patnaik S, Choi HW, Kim JI, Nha KW. Athroscopic treatment of localized synovial chondromatosis of the posterior knee joint. Orthopedics. 2010;33(1):49