User login

Educating the next generation of health professionals is 1 of 4 congressionally mandated statutory missions of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).1 Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of veterans accessing VA health care was increasing, and those veterans are older and more medically complex than those who seek care outside the VA.2 Almost half of medical residents reported a decline in the quality of their clinical education since the institution of the 2011 duty hours regulations, and in the past decade, more attention has been paid to the need for structured faculty development programs that focus on clinicians’ roles as medical educators.3-6 Hospitalists in particular shoulder a large portion of inpatient medicine education.7 As a result, hospitalists have adapted known frameworks for medical education to their unique clinical setting and developed novel frameworks to meet the needs of their learners.8,9

Access to technology and social media have shaped the educational experience of young learners who are accustomed to quick answers and the rapidity of change.10 The clinical teaching landscape changed again with COVID-19, requiring at least temporary abandonment of traditional in-person teaching methods, which upended well-established educational norms.11,12 In this evolving field, even seasoned preceptors may feel ill-equipped to manage the nuances of modern clinical education and may struggle to recognize which teaching skills are most critical.13,14 Baseline core teaching competencies for medical educators have been previously described and are separate from clinical competencies; however, to our knowledge, no needs assessment has previously been performed specifically for VA hospitalist clinician educators.15

Between May and June of 2020, we distributed an online needs assessment to academic VA hospitalists to identify perceived barriers to effective clinical education and preferred strategies to overcome them. We received 71 responses from 140 hospitalists (50% response rate) on the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) academic hospitalist listserv. Of respondents, 59 (83%) reported teaching health professions trainees every year. VA hospitalists reported educating a diverse group of interprofessional learners, including medical residents and students, physician assistant students, nursing students, pharmacy residents and students, and podiatry students.

Only 14 respondents (20%) were aware of faculty development training available to them through their VA facility, while 53 (75%) were aware of similar resources through academic affiliates or other outside sources. More than 95% of respondents (n = 68) reported interest in receiving VA-specific faculty development to improve skills as clinician educators. The most preferred forms of delivery were in-person or virtual real-time workshops. VA hospitalists reported the least confidence in their ability to support struggling learners, balance supervision and autonomy, and develop individualized learning plans (Table 1).

With a better understanding of the needs of academic VA hospitalists, we sought to develop, implement, and measure the impact of a faculty development program that meets the specific needs of inpatient clinicians in the VA. Here we introduce the program, its content, and the experiences of initial participants.

Teaching the Teacher

Teaching the Teacher began at a single VA institution as a series of in-person, discussion-based faculty development workshops. The series met a local need for collaborative professional development in clinical education for hospitalists and specialists who round with health professions learners on the inpatient wards. Both novice and experienced clinicians participated in the series with positive feedback. Based on the results of the national needs assessment, the program has since expanded to other sites with support from the VHA Hospital Medicine Program Office. The project’s overarching goal was to facilitate sharing of best practices across VA sites and create a network of local and national VA educators that participants could continue to access even after course completion.

Teaching the Teacher is structured into 5 facilitated hour-long sessions that can be completed either daily for 1 week or weekly for 1 month at the discretion of each institution. Each session is dedicated to a subject identified on the needs assessment as being highest yield. The hospitalist needs assessment also identified the preference for targeted faculty development that is relevant specifically to VA clinicians. To meet this need, Teaching the Teacher delivers its content through the unique lens of VA medicine. The educational mission of the VA is threaded throughout all presentations, and tips to maximize teaching in the VA’s unique clinical environments are embedded into each hour. Examples include discussions on how to incorporate veteran patients into bedside teaching, handling challenging patient-practitioner interactions as they pertain to patients, and the use of VA resources to find and teach evidence-based medicine.Each session includes a set of learning objectives; within that framework, facilitators allow participants to guide the nuances of content based on their individual and institutional priorities. The pandemic continues to shape much of the course content, as both hospitalists and their trainees grapple with mental health challenges, decreased bedside teaching, and wide variations in baseline trainee competence due to different institutional responses to teaching during a pandemic.12,16 Content is regularly updated to incorporate new literature and feedback from participants and prioritize active participation. Continuing medical education/continuing educational units credit is available through the VA for course completion.

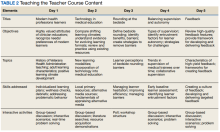

In the first session on modern learners, participants discuss the current generation of health professions trainees, including how personality characteristics and COVID-19 have impacted their learning experiences, and strategies to improve our ability to teach them successfully (Table 2).

The course was originally designed to be in person, but the COVID-19 pandemic forced a shift to online format. To achieve a high-quality learning environment, the course implemented best practices in virtual synchronous instruction, including setting expectations for participation and screen use at the beginning of the series and optimizing audiovisual technology.17 During each seminar, the use of breakout rooms, polling, and the chat function fostered and sustained engagement.17 After each seminar, participants received a recording of the session, a copy of the materials reviewed, and links to referenced readings.17 The course preserved the interactive aspect of the curriculum through both these previously described techniques and our novel approaches, such as facilitated live interactions with online VA resources.

The pandemic also had an impact on curriculum content, as facilitation of online learning was a new and necessary skill set for instructors and participants. To meet this evolving need, additions in content addressed best practices in synchronous and asynchronous online learning, and augmented discussions on navigating asynchronous learning modalities such as social media. A virtual format allowed for dissemination of this course across the country and for recruitment of new course facilitators from remote sites. The team of instructors included academic hospitalist faculty from 3 VA institutions.

Program Impact

Ten academically affiliated VA hospital medicine sections across 6 states have participated in Teaching the Teacher and several more are scheduled at other sites. Of the 10, 5 completed the course in collaboration with another VA site. Ninety-seven clinicians completed < 1 session synchronously but given the asynchronous option, this number likely underestimates the total audience. Participants included physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants.

Surveys were conducted before and after the program, with 58 participants completing the presurvey, 32 the postsurvey, and 27 completing both. Of the 32 postsurvey respondents, 31 (97%) would recommend the seminar to colleagues. The live, discussion-based format was the most valued aspect of the course structure, with engaging facilitators and course content also ranking highly. Just over half (n = 17) indicated specific behavioral changes they plan to enact after completing the series, such as connecting with and better understanding learners, prioritizing high-quality feedback more deliberately, and bringing medicine to the bedside. The most common critiques of the course were requests for more time for feedback skills.

Discussion

Teaching the Teacher is a VA-specific faculty development seminar for hospitalists. Participants who responded to a survey reported that it met their needs as VA clinician educators. This is the first published needs assessment of academic VA hospitalists in their roles as clinician educators and the first faculty development initiative to address those specific needs using a collaborative, multisite approach. Although this program is a pilot, the positive response it has received has set a precedent for increased development and growth.

Teaching the Teacher presents a novel approach with a condensed curriculum that is more convenient and accessible to VA clinicians than previous programs with similar goals. Hospitalists have busy and variable work schedules, and it can be difficult to find time to participate in a traditional faculty development program. While these programs are becoming more commonplace, they are often longitudinal and require a significant time and/or financial commitment from participants.18 In contrast, Teaching the Teacher is only 5 hours long, can be viewed either synchronously or asynchronously, and is no cost to participants. In the future, other specialties may similarly value an efficient faculty development curriculum, and participation from clinicians outside of hospital medicine could augment the richness of content.

Teaching the Teacher’s curriculum is not meant to be exhaustive, but rather to spark conversation among colleagues. According to survey respondents, the most lauded aspect of this program was the facilitated, discussion-based structure, wherein participants are presented with common challenges and encouraged to share their experiences and solutions with colleagues. Of particular interest to the program’s mission of greater community building are the VA facilities that chose to complete the seminar with another hospitalist section from a different institution. Within this structure lies an opportunity for seasoned educators to informally mentor junior colleagues both within and across institutions, and foster connections among educators that continue beyond the completion of the series. We envision this program growing into an enduring professional development course that begins at onboarding and is revisited at regular intervals thereafter.

Another compelling aspect of this project is the interprofessional design, bringing physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants together. Health education, like clinical care, is shifting to a team approach.19 The curriculum addresses topics previously described as high priority for interprofessional faculty development, such as fostering healthy team leadership, motivating learners, and appraising evidence and online resources.20 A pilot project in VA primary care facilities found that deliberate interprofessional education improved collaboration among health care professionals.21 Prior to Teaching the Teacher, no similar faculty development program provided interprofessional learning and collaboration for VA hospitalists.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are several limitations to this preliminary study. Participation at each site was voluntary and did not always reach the full potential audience of hospitalist clinician educators. As one participant stated, future directions include doing “more to involve teachers who need to learn [these skills]. The ones who attended [from our institution] were already the best teachers.” In addition, despite the asynchronous option, lack of protected time for faculty development may be a limiting factor in participation. Support from institutional and national leadership would likely improve participation.

Measured endpoints to date consist primarily of participant satisfaction and do not yet capture objective changes in teaching. Data collection is ongoing to assess immediate and longitudinal changes in confidence and behaviors of attendees and how this might affect their health professions learners.

Last, our initial needs assessment only targeted academic hospitalists, and the needs of VA hospitalists in rural areas or at facilities without academic affiliation may be different. More research is needed to understand the diverse faculty that comprises both urban and rural VA sites, what their professional development needs are, and how those needs can be met.

Conclusions

Teaching the Teacher is a faculty development pilot, tailored to meet the needs of VA hospitalist clinician educators, that has been voluntarily adopted at multiple VA sites. The facilitated discussion format allows participants to guide the conversation and personalize content, thereby promoting a culture of discussing challenges and best practices among colleagues that we hope endures beyond the bounds of the curriculum. The program focuses on elevating the specific teaching mission of the VA and could be incorporated into onboarding and regular VA-sponsored faculty development updates. While Teaching the Teacher was originally developed for VA hospitalists, most of the content is applicable to clinicians outside hospital medicine. This project serves as a model for training clinical educators and has opportunities to expand across VA as a customizable didactic platform.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian Schneider, MD, for his tireless support of this program, as well as all the VA clinicians who have shared their time, talents, and wisdom with us since this program’s inception.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Academic Affiliations. Mission of the Office of Academic Affiliations. Updated September 24, 2019. Accessed November 29, 2022. https://www.va.gov/oaa/oaa_mission.asp

2. Eibner C, Krull H, Brown KM, et al. Current and projected characteristics and unique health care needs of the patient population served by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Rand Health Q. 2016;5(4):13. Published 2016 May 9.

3. Drolet BC, Christopher DA, Fischer SA. Residents’ response to duty-hour regulations--a follow-up national survey. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(24):e35. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1202848

4. Hatem CJ, Lown BA, Newman LR. The academic health center coming of age: helping faculty become better teachers and agents of educational change. Acad Med. 2006;81(11):941-944. doi:10.1097/01.ACM.0000242490.56586.64

5. Harvey MM, Berkley HH, O’Malley PG, Durning SJ. Preparing future medical educators: development and pilot evaluation of a student-led medical education elective. Mil Med. 2020;185(1-2):e131-e137. doi:10.1093/milmed/usz175

6. Jason H. Future medical education: Preparing, priorities, possibilities. Med Teach. 2018;40(10):996-1003. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2018.1503412

7. Natarajan P, Ranji SR, Auerbach AD, Hauer KE. Effect of hospitalist attending physicians on trainee educational experiences: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(8):490-498. doi:10.1002/jhm.537

8. Pascoe JM, Nixon J, Lang VJ. Maximizing teaching on the wards: review and application of the One-Minute Preceptor and SNAPPS models. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(2):125-130. doi:10.1002/jhm.2302

9. Martin SK, Farnan JM, Arora VM. Future: new strategies for hospitalists to overcome challenges in teaching on today’s wards. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(7):409-413. doi:10.1002/jhm.2057

10. Waljee JF, Chopra V, Saint S. Mentoring Millennials. JAMA. 2020;323(17):1716-1717. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.3085

11. Papapanou M, Routsi E, Tsamakis K, et al. Medical education challenges and innovations during COVID-19 pandemic. Postgrad Med J. 2022;98(1159):321-327. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2021-140032

12. Hilburg R, Patel N, Ambruso S, Biewald MA, Farouk SS. Medical education during the Coronavirus Disease-2019 pandemic: learning from a distance. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2020;27(5):412-417. doi:10.1053/j.ackd.2020.05.017

13. Simpson D, Marcdante K, Souza KH, Anderson A, Holmboe E. Job roles of the 2025 medical educator. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(3):243-246. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-18-00253.1

14. Armstrong EG, Mackey M, Spear SJ. Medical education as a process management problem. Acad Med. 2004;79(8):721-728. doi:10.1097/00001888-200408000-00002

15. Srinivasan M, Li ST, Meyers FJ, et al. “Teaching as a Competency”: competencies for medical educators. Acad Med. 2011;86(10):1211-1220. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822c5b9a

16. Clark E, Freytag J, Hysong SJ, Dang B, Giordano TP, Kulkarni PA. 964. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on bedside medical education: a mixed-methods study. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(Suppl 1):S574. Published 2021 Dec 4. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofab466.1159

17. Ohnigian S, Richards JB, Monette DL, Roberts DH. optimizing remote learning: leveraging zoom to develop and implement successful education sessions. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2021;8:23821205211020760. Published 2021 Jun 28. doi:10.1177/23821205211020760

18. Burgess A, Matar E, Neuen B, Fox GJ. A longitudinal faculty development program: supporting a culture of teaching. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):400. Published 2019 Nov 1. doi:10.1186/s12909-019-1832-3

19. Stoddard HA, Brownfield ED. Clinician-educators as dual professionals: a contemporary reappraisal. Acad Med. 2016;91(7):921-924. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001210

20. Schönwetter DJ, Hamilton J, Sawatzky JA. Exploring professional development needs of educators in the health sciences professions. J Dent Educ. 2015;79(2):113-123.

21. Meyer EM, Zapatka S, Brienza RS. The development of professional identity and the formation of teams in the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System’s Center of Excellence in Primary Care Education Program (CoEPCE). Acad Med. 2015;90(6):802-809. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000594

Educating the next generation of health professionals is 1 of 4 congressionally mandated statutory missions of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).1 Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of veterans accessing VA health care was increasing, and those veterans are older and more medically complex than those who seek care outside the VA.2 Almost half of medical residents reported a decline in the quality of their clinical education since the institution of the 2011 duty hours regulations, and in the past decade, more attention has been paid to the need for structured faculty development programs that focus on clinicians’ roles as medical educators.3-6 Hospitalists in particular shoulder a large portion of inpatient medicine education.7 As a result, hospitalists have adapted known frameworks for medical education to their unique clinical setting and developed novel frameworks to meet the needs of their learners.8,9

Access to technology and social media have shaped the educational experience of young learners who are accustomed to quick answers and the rapidity of change.10 The clinical teaching landscape changed again with COVID-19, requiring at least temporary abandonment of traditional in-person teaching methods, which upended well-established educational norms.11,12 In this evolving field, even seasoned preceptors may feel ill-equipped to manage the nuances of modern clinical education and may struggle to recognize which teaching skills are most critical.13,14 Baseline core teaching competencies for medical educators have been previously described and are separate from clinical competencies; however, to our knowledge, no needs assessment has previously been performed specifically for VA hospitalist clinician educators.15

Between May and June of 2020, we distributed an online needs assessment to academic VA hospitalists to identify perceived barriers to effective clinical education and preferred strategies to overcome them. We received 71 responses from 140 hospitalists (50% response rate) on the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) academic hospitalist listserv. Of respondents, 59 (83%) reported teaching health professions trainees every year. VA hospitalists reported educating a diverse group of interprofessional learners, including medical residents and students, physician assistant students, nursing students, pharmacy residents and students, and podiatry students.

Only 14 respondents (20%) were aware of faculty development training available to them through their VA facility, while 53 (75%) were aware of similar resources through academic affiliates or other outside sources. More than 95% of respondents (n = 68) reported interest in receiving VA-specific faculty development to improve skills as clinician educators. The most preferred forms of delivery were in-person or virtual real-time workshops. VA hospitalists reported the least confidence in their ability to support struggling learners, balance supervision and autonomy, and develop individualized learning plans (Table 1).

With a better understanding of the needs of academic VA hospitalists, we sought to develop, implement, and measure the impact of a faculty development program that meets the specific needs of inpatient clinicians in the VA. Here we introduce the program, its content, and the experiences of initial participants.

Teaching the Teacher

Teaching the Teacher began at a single VA institution as a series of in-person, discussion-based faculty development workshops. The series met a local need for collaborative professional development in clinical education for hospitalists and specialists who round with health professions learners on the inpatient wards. Both novice and experienced clinicians participated in the series with positive feedback. Based on the results of the national needs assessment, the program has since expanded to other sites with support from the VHA Hospital Medicine Program Office. The project’s overarching goal was to facilitate sharing of best practices across VA sites and create a network of local and national VA educators that participants could continue to access even after course completion.

Teaching the Teacher is structured into 5 facilitated hour-long sessions that can be completed either daily for 1 week or weekly for 1 month at the discretion of each institution. Each session is dedicated to a subject identified on the needs assessment as being highest yield. The hospitalist needs assessment also identified the preference for targeted faculty development that is relevant specifically to VA clinicians. To meet this need, Teaching the Teacher delivers its content through the unique lens of VA medicine. The educational mission of the VA is threaded throughout all presentations, and tips to maximize teaching in the VA’s unique clinical environments are embedded into each hour. Examples include discussions on how to incorporate veteran patients into bedside teaching, handling challenging patient-practitioner interactions as they pertain to patients, and the use of VA resources to find and teach evidence-based medicine.Each session includes a set of learning objectives; within that framework, facilitators allow participants to guide the nuances of content based on their individual and institutional priorities. The pandemic continues to shape much of the course content, as both hospitalists and their trainees grapple with mental health challenges, decreased bedside teaching, and wide variations in baseline trainee competence due to different institutional responses to teaching during a pandemic.12,16 Content is regularly updated to incorporate new literature and feedback from participants and prioritize active participation. Continuing medical education/continuing educational units credit is available through the VA for course completion.

In the first session on modern learners, participants discuss the current generation of health professions trainees, including how personality characteristics and COVID-19 have impacted their learning experiences, and strategies to improve our ability to teach them successfully (Table 2).

The course was originally designed to be in person, but the COVID-19 pandemic forced a shift to online format. To achieve a high-quality learning environment, the course implemented best practices in virtual synchronous instruction, including setting expectations for participation and screen use at the beginning of the series and optimizing audiovisual technology.17 During each seminar, the use of breakout rooms, polling, and the chat function fostered and sustained engagement.17 After each seminar, participants received a recording of the session, a copy of the materials reviewed, and links to referenced readings.17 The course preserved the interactive aspect of the curriculum through both these previously described techniques and our novel approaches, such as facilitated live interactions with online VA resources.

The pandemic also had an impact on curriculum content, as facilitation of online learning was a new and necessary skill set for instructors and participants. To meet this evolving need, additions in content addressed best practices in synchronous and asynchronous online learning, and augmented discussions on navigating asynchronous learning modalities such as social media. A virtual format allowed for dissemination of this course across the country and for recruitment of new course facilitators from remote sites. The team of instructors included academic hospitalist faculty from 3 VA institutions.

Program Impact

Ten academically affiliated VA hospital medicine sections across 6 states have participated in Teaching the Teacher and several more are scheduled at other sites. Of the 10, 5 completed the course in collaboration with another VA site. Ninety-seven clinicians completed < 1 session synchronously but given the asynchronous option, this number likely underestimates the total audience. Participants included physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants.

Surveys were conducted before and after the program, with 58 participants completing the presurvey, 32 the postsurvey, and 27 completing both. Of the 32 postsurvey respondents, 31 (97%) would recommend the seminar to colleagues. The live, discussion-based format was the most valued aspect of the course structure, with engaging facilitators and course content also ranking highly. Just over half (n = 17) indicated specific behavioral changes they plan to enact after completing the series, such as connecting with and better understanding learners, prioritizing high-quality feedback more deliberately, and bringing medicine to the bedside. The most common critiques of the course were requests for more time for feedback skills.

Discussion

Teaching the Teacher is a VA-specific faculty development seminar for hospitalists. Participants who responded to a survey reported that it met their needs as VA clinician educators. This is the first published needs assessment of academic VA hospitalists in their roles as clinician educators and the first faculty development initiative to address those specific needs using a collaborative, multisite approach. Although this program is a pilot, the positive response it has received has set a precedent for increased development and growth.

Teaching the Teacher presents a novel approach with a condensed curriculum that is more convenient and accessible to VA clinicians than previous programs with similar goals. Hospitalists have busy and variable work schedules, and it can be difficult to find time to participate in a traditional faculty development program. While these programs are becoming more commonplace, they are often longitudinal and require a significant time and/or financial commitment from participants.18 In contrast, Teaching the Teacher is only 5 hours long, can be viewed either synchronously or asynchronously, and is no cost to participants. In the future, other specialties may similarly value an efficient faculty development curriculum, and participation from clinicians outside of hospital medicine could augment the richness of content.

Teaching the Teacher’s curriculum is not meant to be exhaustive, but rather to spark conversation among colleagues. According to survey respondents, the most lauded aspect of this program was the facilitated, discussion-based structure, wherein participants are presented with common challenges and encouraged to share their experiences and solutions with colleagues. Of particular interest to the program’s mission of greater community building are the VA facilities that chose to complete the seminar with another hospitalist section from a different institution. Within this structure lies an opportunity for seasoned educators to informally mentor junior colleagues both within and across institutions, and foster connections among educators that continue beyond the completion of the series. We envision this program growing into an enduring professional development course that begins at onboarding and is revisited at regular intervals thereafter.

Another compelling aspect of this project is the interprofessional design, bringing physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants together. Health education, like clinical care, is shifting to a team approach.19 The curriculum addresses topics previously described as high priority for interprofessional faculty development, such as fostering healthy team leadership, motivating learners, and appraising evidence and online resources.20 A pilot project in VA primary care facilities found that deliberate interprofessional education improved collaboration among health care professionals.21 Prior to Teaching the Teacher, no similar faculty development program provided interprofessional learning and collaboration for VA hospitalists.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are several limitations to this preliminary study. Participation at each site was voluntary and did not always reach the full potential audience of hospitalist clinician educators. As one participant stated, future directions include doing “more to involve teachers who need to learn [these skills]. The ones who attended [from our institution] were already the best teachers.” In addition, despite the asynchronous option, lack of protected time for faculty development may be a limiting factor in participation. Support from institutional and national leadership would likely improve participation.

Measured endpoints to date consist primarily of participant satisfaction and do not yet capture objective changes in teaching. Data collection is ongoing to assess immediate and longitudinal changes in confidence and behaviors of attendees and how this might affect their health professions learners.

Last, our initial needs assessment only targeted academic hospitalists, and the needs of VA hospitalists in rural areas or at facilities without academic affiliation may be different. More research is needed to understand the diverse faculty that comprises both urban and rural VA sites, what their professional development needs are, and how those needs can be met.

Conclusions

Teaching the Teacher is a faculty development pilot, tailored to meet the needs of VA hospitalist clinician educators, that has been voluntarily adopted at multiple VA sites. The facilitated discussion format allows participants to guide the conversation and personalize content, thereby promoting a culture of discussing challenges and best practices among colleagues that we hope endures beyond the bounds of the curriculum. The program focuses on elevating the specific teaching mission of the VA and could be incorporated into onboarding and regular VA-sponsored faculty development updates. While Teaching the Teacher was originally developed for VA hospitalists, most of the content is applicable to clinicians outside hospital medicine. This project serves as a model for training clinical educators and has opportunities to expand across VA as a customizable didactic platform.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian Schneider, MD, for his tireless support of this program, as well as all the VA clinicians who have shared their time, talents, and wisdom with us since this program’s inception.

Educating the next generation of health professionals is 1 of 4 congressionally mandated statutory missions of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).1 Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of veterans accessing VA health care was increasing, and those veterans are older and more medically complex than those who seek care outside the VA.2 Almost half of medical residents reported a decline in the quality of their clinical education since the institution of the 2011 duty hours regulations, and in the past decade, more attention has been paid to the need for structured faculty development programs that focus on clinicians’ roles as medical educators.3-6 Hospitalists in particular shoulder a large portion of inpatient medicine education.7 As a result, hospitalists have adapted known frameworks for medical education to their unique clinical setting and developed novel frameworks to meet the needs of their learners.8,9

Access to technology and social media have shaped the educational experience of young learners who are accustomed to quick answers and the rapidity of change.10 The clinical teaching landscape changed again with COVID-19, requiring at least temporary abandonment of traditional in-person teaching methods, which upended well-established educational norms.11,12 In this evolving field, even seasoned preceptors may feel ill-equipped to manage the nuances of modern clinical education and may struggle to recognize which teaching skills are most critical.13,14 Baseline core teaching competencies for medical educators have been previously described and are separate from clinical competencies; however, to our knowledge, no needs assessment has previously been performed specifically for VA hospitalist clinician educators.15

Between May and June of 2020, we distributed an online needs assessment to academic VA hospitalists to identify perceived barriers to effective clinical education and preferred strategies to overcome them. We received 71 responses from 140 hospitalists (50% response rate) on the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) academic hospitalist listserv. Of respondents, 59 (83%) reported teaching health professions trainees every year. VA hospitalists reported educating a diverse group of interprofessional learners, including medical residents and students, physician assistant students, nursing students, pharmacy residents and students, and podiatry students.

Only 14 respondents (20%) were aware of faculty development training available to them through their VA facility, while 53 (75%) were aware of similar resources through academic affiliates or other outside sources. More than 95% of respondents (n = 68) reported interest in receiving VA-specific faculty development to improve skills as clinician educators. The most preferred forms of delivery were in-person or virtual real-time workshops. VA hospitalists reported the least confidence in their ability to support struggling learners, balance supervision and autonomy, and develop individualized learning plans (Table 1).

With a better understanding of the needs of academic VA hospitalists, we sought to develop, implement, and measure the impact of a faculty development program that meets the specific needs of inpatient clinicians in the VA. Here we introduce the program, its content, and the experiences of initial participants.

Teaching the Teacher

Teaching the Teacher began at a single VA institution as a series of in-person, discussion-based faculty development workshops. The series met a local need for collaborative professional development in clinical education for hospitalists and specialists who round with health professions learners on the inpatient wards. Both novice and experienced clinicians participated in the series with positive feedback. Based on the results of the national needs assessment, the program has since expanded to other sites with support from the VHA Hospital Medicine Program Office. The project’s overarching goal was to facilitate sharing of best practices across VA sites and create a network of local and national VA educators that participants could continue to access even after course completion.

Teaching the Teacher is structured into 5 facilitated hour-long sessions that can be completed either daily for 1 week or weekly for 1 month at the discretion of each institution. Each session is dedicated to a subject identified on the needs assessment as being highest yield. The hospitalist needs assessment also identified the preference for targeted faculty development that is relevant specifically to VA clinicians. To meet this need, Teaching the Teacher delivers its content through the unique lens of VA medicine. The educational mission of the VA is threaded throughout all presentations, and tips to maximize teaching in the VA’s unique clinical environments are embedded into each hour. Examples include discussions on how to incorporate veteran patients into bedside teaching, handling challenging patient-practitioner interactions as they pertain to patients, and the use of VA resources to find and teach evidence-based medicine.Each session includes a set of learning objectives; within that framework, facilitators allow participants to guide the nuances of content based on their individual and institutional priorities. The pandemic continues to shape much of the course content, as both hospitalists and their trainees grapple with mental health challenges, decreased bedside teaching, and wide variations in baseline trainee competence due to different institutional responses to teaching during a pandemic.12,16 Content is regularly updated to incorporate new literature and feedback from participants and prioritize active participation. Continuing medical education/continuing educational units credit is available through the VA for course completion.

In the first session on modern learners, participants discuss the current generation of health professions trainees, including how personality characteristics and COVID-19 have impacted their learning experiences, and strategies to improve our ability to teach them successfully (Table 2).

The course was originally designed to be in person, but the COVID-19 pandemic forced a shift to online format. To achieve a high-quality learning environment, the course implemented best practices in virtual synchronous instruction, including setting expectations for participation and screen use at the beginning of the series and optimizing audiovisual technology.17 During each seminar, the use of breakout rooms, polling, and the chat function fostered and sustained engagement.17 After each seminar, participants received a recording of the session, a copy of the materials reviewed, and links to referenced readings.17 The course preserved the interactive aspect of the curriculum through both these previously described techniques and our novel approaches, such as facilitated live interactions with online VA resources.

The pandemic also had an impact on curriculum content, as facilitation of online learning was a new and necessary skill set for instructors and participants. To meet this evolving need, additions in content addressed best practices in synchronous and asynchronous online learning, and augmented discussions on navigating asynchronous learning modalities such as social media. A virtual format allowed for dissemination of this course across the country and for recruitment of new course facilitators from remote sites. The team of instructors included academic hospitalist faculty from 3 VA institutions.

Program Impact

Ten academically affiliated VA hospital medicine sections across 6 states have participated in Teaching the Teacher and several more are scheduled at other sites. Of the 10, 5 completed the course in collaboration with another VA site. Ninety-seven clinicians completed < 1 session synchronously but given the asynchronous option, this number likely underestimates the total audience. Participants included physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants.

Surveys were conducted before and after the program, with 58 participants completing the presurvey, 32 the postsurvey, and 27 completing both. Of the 32 postsurvey respondents, 31 (97%) would recommend the seminar to colleagues. The live, discussion-based format was the most valued aspect of the course structure, with engaging facilitators and course content also ranking highly. Just over half (n = 17) indicated specific behavioral changes they plan to enact after completing the series, such as connecting with and better understanding learners, prioritizing high-quality feedback more deliberately, and bringing medicine to the bedside. The most common critiques of the course were requests for more time for feedback skills.

Discussion

Teaching the Teacher is a VA-specific faculty development seminar for hospitalists. Participants who responded to a survey reported that it met their needs as VA clinician educators. This is the first published needs assessment of academic VA hospitalists in their roles as clinician educators and the first faculty development initiative to address those specific needs using a collaborative, multisite approach. Although this program is a pilot, the positive response it has received has set a precedent for increased development and growth.

Teaching the Teacher presents a novel approach with a condensed curriculum that is more convenient and accessible to VA clinicians than previous programs with similar goals. Hospitalists have busy and variable work schedules, and it can be difficult to find time to participate in a traditional faculty development program. While these programs are becoming more commonplace, they are often longitudinal and require a significant time and/or financial commitment from participants.18 In contrast, Teaching the Teacher is only 5 hours long, can be viewed either synchronously or asynchronously, and is no cost to participants. In the future, other specialties may similarly value an efficient faculty development curriculum, and participation from clinicians outside of hospital medicine could augment the richness of content.

Teaching the Teacher’s curriculum is not meant to be exhaustive, but rather to spark conversation among colleagues. According to survey respondents, the most lauded aspect of this program was the facilitated, discussion-based structure, wherein participants are presented with common challenges and encouraged to share their experiences and solutions with colleagues. Of particular interest to the program’s mission of greater community building are the VA facilities that chose to complete the seminar with another hospitalist section from a different institution. Within this structure lies an opportunity for seasoned educators to informally mentor junior colleagues both within and across institutions, and foster connections among educators that continue beyond the completion of the series. We envision this program growing into an enduring professional development course that begins at onboarding and is revisited at regular intervals thereafter.

Another compelling aspect of this project is the interprofessional design, bringing physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants together. Health education, like clinical care, is shifting to a team approach.19 The curriculum addresses topics previously described as high priority for interprofessional faculty development, such as fostering healthy team leadership, motivating learners, and appraising evidence and online resources.20 A pilot project in VA primary care facilities found that deliberate interprofessional education improved collaboration among health care professionals.21 Prior to Teaching the Teacher, no similar faculty development program provided interprofessional learning and collaboration for VA hospitalists.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are several limitations to this preliminary study. Participation at each site was voluntary and did not always reach the full potential audience of hospitalist clinician educators. As one participant stated, future directions include doing “more to involve teachers who need to learn [these skills]. The ones who attended [from our institution] were already the best teachers.” In addition, despite the asynchronous option, lack of protected time for faculty development may be a limiting factor in participation. Support from institutional and national leadership would likely improve participation.

Measured endpoints to date consist primarily of participant satisfaction and do not yet capture objective changes in teaching. Data collection is ongoing to assess immediate and longitudinal changes in confidence and behaviors of attendees and how this might affect their health professions learners.

Last, our initial needs assessment only targeted academic hospitalists, and the needs of VA hospitalists in rural areas or at facilities without academic affiliation may be different. More research is needed to understand the diverse faculty that comprises both urban and rural VA sites, what their professional development needs are, and how those needs can be met.

Conclusions

Teaching the Teacher is a faculty development pilot, tailored to meet the needs of VA hospitalist clinician educators, that has been voluntarily adopted at multiple VA sites. The facilitated discussion format allows participants to guide the conversation and personalize content, thereby promoting a culture of discussing challenges and best practices among colleagues that we hope endures beyond the bounds of the curriculum. The program focuses on elevating the specific teaching mission of the VA and could be incorporated into onboarding and regular VA-sponsored faculty development updates. While Teaching the Teacher was originally developed for VA hospitalists, most of the content is applicable to clinicians outside hospital medicine. This project serves as a model for training clinical educators and has opportunities to expand across VA as a customizable didactic platform.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian Schneider, MD, for his tireless support of this program, as well as all the VA clinicians who have shared their time, talents, and wisdom with us since this program’s inception.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Academic Affiliations. Mission of the Office of Academic Affiliations. Updated September 24, 2019. Accessed November 29, 2022. https://www.va.gov/oaa/oaa_mission.asp

2. Eibner C, Krull H, Brown KM, et al. Current and projected characteristics and unique health care needs of the patient population served by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Rand Health Q. 2016;5(4):13. Published 2016 May 9.

3. Drolet BC, Christopher DA, Fischer SA. Residents’ response to duty-hour regulations--a follow-up national survey. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(24):e35. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1202848

4. Hatem CJ, Lown BA, Newman LR. The academic health center coming of age: helping faculty become better teachers and agents of educational change. Acad Med. 2006;81(11):941-944. doi:10.1097/01.ACM.0000242490.56586.64

5. Harvey MM, Berkley HH, O’Malley PG, Durning SJ. Preparing future medical educators: development and pilot evaluation of a student-led medical education elective. Mil Med. 2020;185(1-2):e131-e137. doi:10.1093/milmed/usz175

6. Jason H. Future medical education: Preparing, priorities, possibilities. Med Teach. 2018;40(10):996-1003. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2018.1503412

7. Natarajan P, Ranji SR, Auerbach AD, Hauer KE. Effect of hospitalist attending physicians on trainee educational experiences: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(8):490-498. doi:10.1002/jhm.537

8. Pascoe JM, Nixon J, Lang VJ. Maximizing teaching on the wards: review and application of the One-Minute Preceptor and SNAPPS models. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(2):125-130. doi:10.1002/jhm.2302

9. Martin SK, Farnan JM, Arora VM. Future: new strategies for hospitalists to overcome challenges in teaching on today’s wards. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(7):409-413. doi:10.1002/jhm.2057

10. Waljee JF, Chopra V, Saint S. Mentoring Millennials. JAMA. 2020;323(17):1716-1717. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.3085

11. Papapanou M, Routsi E, Tsamakis K, et al. Medical education challenges and innovations during COVID-19 pandemic. Postgrad Med J. 2022;98(1159):321-327. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2021-140032

12. Hilburg R, Patel N, Ambruso S, Biewald MA, Farouk SS. Medical education during the Coronavirus Disease-2019 pandemic: learning from a distance. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2020;27(5):412-417. doi:10.1053/j.ackd.2020.05.017

13. Simpson D, Marcdante K, Souza KH, Anderson A, Holmboe E. Job roles of the 2025 medical educator. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(3):243-246. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-18-00253.1

14. Armstrong EG, Mackey M, Spear SJ. Medical education as a process management problem. Acad Med. 2004;79(8):721-728. doi:10.1097/00001888-200408000-00002

15. Srinivasan M, Li ST, Meyers FJ, et al. “Teaching as a Competency”: competencies for medical educators. Acad Med. 2011;86(10):1211-1220. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822c5b9a

16. Clark E, Freytag J, Hysong SJ, Dang B, Giordano TP, Kulkarni PA. 964. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on bedside medical education: a mixed-methods study. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(Suppl 1):S574. Published 2021 Dec 4. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofab466.1159

17. Ohnigian S, Richards JB, Monette DL, Roberts DH. optimizing remote learning: leveraging zoom to develop and implement successful education sessions. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2021;8:23821205211020760. Published 2021 Jun 28. doi:10.1177/23821205211020760

18. Burgess A, Matar E, Neuen B, Fox GJ. A longitudinal faculty development program: supporting a culture of teaching. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):400. Published 2019 Nov 1. doi:10.1186/s12909-019-1832-3

19. Stoddard HA, Brownfield ED. Clinician-educators as dual professionals: a contemporary reappraisal. Acad Med. 2016;91(7):921-924. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001210

20. Schönwetter DJ, Hamilton J, Sawatzky JA. Exploring professional development needs of educators in the health sciences professions. J Dent Educ. 2015;79(2):113-123.

21. Meyer EM, Zapatka S, Brienza RS. The development of professional identity and the formation of teams in the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System’s Center of Excellence in Primary Care Education Program (CoEPCE). Acad Med. 2015;90(6):802-809. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000594

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Academic Affiliations. Mission of the Office of Academic Affiliations. Updated September 24, 2019. Accessed November 29, 2022. https://www.va.gov/oaa/oaa_mission.asp

2. Eibner C, Krull H, Brown KM, et al. Current and projected characteristics and unique health care needs of the patient population served by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Rand Health Q. 2016;5(4):13. Published 2016 May 9.

3. Drolet BC, Christopher DA, Fischer SA. Residents’ response to duty-hour regulations--a follow-up national survey. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(24):e35. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1202848

4. Hatem CJ, Lown BA, Newman LR. The academic health center coming of age: helping faculty become better teachers and agents of educational change. Acad Med. 2006;81(11):941-944. doi:10.1097/01.ACM.0000242490.56586.64

5. Harvey MM, Berkley HH, O’Malley PG, Durning SJ. Preparing future medical educators: development and pilot evaluation of a student-led medical education elective. Mil Med. 2020;185(1-2):e131-e137. doi:10.1093/milmed/usz175

6. Jason H. Future medical education: Preparing, priorities, possibilities. Med Teach. 2018;40(10):996-1003. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2018.1503412

7. Natarajan P, Ranji SR, Auerbach AD, Hauer KE. Effect of hospitalist attending physicians on trainee educational experiences: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(8):490-498. doi:10.1002/jhm.537

8. Pascoe JM, Nixon J, Lang VJ. Maximizing teaching on the wards: review and application of the One-Minute Preceptor and SNAPPS models. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(2):125-130. doi:10.1002/jhm.2302

9. Martin SK, Farnan JM, Arora VM. Future: new strategies for hospitalists to overcome challenges in teaching on today’s wards. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(7):409-413. doi:10.1002/jhm.2057

10. Waljee JF, Chopra V, Saint S. Mentoring Millennials. JAMA. 2020;323(17):1716-1717. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.3085

11. Papapanou M, Routsi E, Tsamakis K, et al. Medical education challenges and innovations during COVID-19 pandemic. Postgrad Med J. 2022;98(1159):321-327. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2021-140032

12. Hilburg R, Patel N, Ambruso S, Biewald MA, Farouk SS. Medical education during the Coronavirus Disease-2019 pandemic: learning from a distance. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2020;27(5):412-417. doi:10.1053/j.ackd.2020.05.017

13. Simpson D, Marcdante K, Souza KH, Anderson A, Holmboe E. Job roles of the 2025 medical educator. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(3):243-246. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-18-00253.1

14. Armstrong EG, Mackey M, Spear SJ. Medical education as a process management problem. Acad Med. 2004;79(8):721-728. doi:10.1097/00001888-200408000-00002

15. Srinivasan M, Li ST, Meyers FJ, et al. “Teaching as a Competency”: competencies for medical educators. Acad Med. 2011;86(10):1211-1220. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822c5b9a

16. Clark E, Freytag J, Hysong SJ, Dang B, Giordano TP, Kulkarni PA. 964. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on bedside medical education: a mixed-methods study. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(Suppl 1):S574. Published 2021 Dec 4. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofab466.1159

17. Ohnigian S, Richards JB, Monette DL, Roberts DH. optimizing remote learning: leveraging zoom to develop and implement successful education sessions. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2021;8:23821205211020760. Published 2021 Jun 28. doi:10.1177/23821205211020760

18. Burgess A, Matar E, Neuen B, Fox GJ. A longitudinal faculty development program: supporting a culture of teaching. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):400. Published 2019 Nov 1. doi:10.1186/s12909-019-1832-3

19. Stoddard HA, Brownfield ED. Clinician-educators as dual professionals: a contemporary reappraisal. Acad Med. 2016;91(7):921-924. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001210

20. Schönwetter DJ, Hamilton J, Sawatzky JA. Exploring professional development needs of educators in the health sciences professions. J Dent Educ. 2015;79(2):113-123.

21. Meyer EM, Zapatka S, Brienza RS. The development of professional identity and the formation of teams in the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System’s Center of Excellence in Primary Care Education Program (CoEPCE). Acad Med. 2015;90(6):802-809. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000594