User login

Manic episodes, by definition, are associated with significant social or occupational impairment.1 Some manic patients are violent or engage in reckless behaviors that can harm themselves or others, such as speeding, disrupting traffic, or playing with fire. When these patients present to a psychiatrist’s outpatient practice, involuntary hospitalization might be justified.

However, some manic patients, in spite of their elevated, expansive, or irritable mood state, never behave dangerously and might not meet legal criteria for involuntary hospitalization, although these criteria differ from state to state. These patients might see a psychiatrist because manic symptoms such as irritability, talkativeness, and impulsivity are bothersome to their family members but pose no serious danger (Box). In this situation, the psychiatrist can strongly encourage the patient to seek voluntary hospitalization or attend a partial hospitalization program. If the patient declines, the psychiatrist is left with 2 choices: initiate treatment in the outpatient setting or refuse to treat the patient and refer to another provider.

Treating “non-dangerous” mania in the outpatient setting is fraught with challenges:

• the possibility that the patient’s condition will progress to dangerousness

• poor adherence to treatment because of the patient’s limited insight

• the large amount of time required from the psychiatrist and care team to adequately manage the manic episode (eg, time spent with family members, frequent patient visits, and managing communications from the patient).

There are no guidelines to assist the office-based practitioner in treating mania in the outpatient setting. When considering dosing and optimal medication combinations for treating mania, clinical trials may be of limited value because most of these studies only included hospitalized manic patients.

Because of this dearth of knowledge, we provide recommendations based on our review of the literature and from our experience working with manic patients who refuse voluntary hospitalization and could not be hospitalized against their will. These recommendations are organized into 3 sections: diagnostic approach, treatment strategy, and family involvement.

Diagnostic approach

Making a diagnosis of mania might seem straightforward for clinicians who work in inpatient settings; however, mania might not present with classic florid symptoms among outpatients. Patients might have a chief concern of irritability, dysphoria, anxiety, or “insomnia,” which may lead clinicians to focus initially on non-bipolar conditions.2

During the interview, it is important to assess for any current DSM-5 symptoms of a manic episode, while being careful not to accept a patient’s denial of symptoms. Patients with mania often have poor insight and are unaware of changes from their baseline state when manic.3 Alternatively, manic patients may want you to believe that they are well and could minimize or deny all symptoms. Therefore, it is important to pay attention to mental status examination findings, such as hyperverbal speech, elated affect, psychomotor agitation, a tangential thought process, or flight of ideas.

Countertransference feelings of diagnostic confusion or frustration after long patient monologues or multiple interruptions by the patient should be incorporated into the diagnostic assessment. Family members or friends often can provide objective observations of behavioral changes necessary to secure the diagnosis.

Treatment strategy

Decision points. When treating manic outpatients, assess the need for hospitalization at each visit. Advantages of the inpatient setting include:

• the possibility of rapid medication adjustments

• continuous observation to ensure the patient’s safety

• keeping the patient temporarily removed from his community to prevent irreversible social and economic harms.

However, a challenge with hospitalization is third-party payers’ influence on a patient’s length of stay, which may lead to rapid medication changes that may not be clinically ideal.

At each outpatient visit, explore with the patient and family emerging symptoms that could justify involuntary hospitalization. Document whether you recommended inpatient hospitalization, the patient’s response to the recommendation, that you are aware and have considered the risks associated with outpatient care, and that you have discussed these risks with the patient and family.

For patients well-known to the psychiatrist, a history of dangerous mania may lead him (her) to strongly recommend hospitalization, whereas a pre-existing therapeutic alliance and no current or distant history of dangerous mania may lead the clinician to look for alternatives to inpatient care. Concomitant drug or alcohol use may increase the likelihood of mania becoming dangerous, making outpatient treatment ill-advised and riskier for everyone involved.

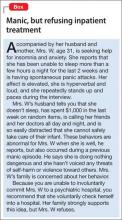

In exchange for agreeing to provide outpatient care for mania, it often is helpful to negotiate with the patient and family a threshold level of symptoms or behavior that will result in the patient agreeing to voluntary hospitalization (Table 1). Such an agreement can include stopping outpatient treatment if the patient does not improve significantly after 2 or 3 weeks or develops psychotic symptoms. The negotiation also can include partial hospitalization as an option, so long as the patient’s mania continues to be non-dangerous.

Obtaining pretreatment blood work can help a clinician determine whether a medication is safe to prescribe and establish causality if laboratory abnormalities arise after treatment begins. Ideally, the psychiatrist should follow consensus guidelines developed by the International Society for Bipolar Disorders4 or the American Psychiatric Association (APA)5 and order appropriate laboratory tests before prescribing anti-manic medications. Determine the pregnancy status of female patients of child-bearing age before prescribing a potentially teratogenic medication, especially because mania is associated with increased libido.6

Manic patients might be too disorganized to follow up with recommendations for laboratory testing, or could wait several days before completing blood work. Although not ideal, to avoid delaying treatment, a clinician might need to prescribe medication at the initial office visit, without pretreatment laboratory results. When the patient is more organized, complete the blood work. Keeping home pregnancy tests in the office can help rule out pregnancy before prescribing medication.

Medication. Meta-analyses have established the efficacy of mood stabilizers and antipsychotics for treating mania,7,8 and several consensus guidelines have incorporated these findings into treatment algorithms.9

For a patient already taking medications recommended by the guidelines, assess treatment adherence during the initial interview by questioning the patient and family. When the logistics of phlebotomy permit, obtaining the blood level of psychotropics can show the presence of any detectable drug concentration, which demonstrates that the patient has taken the medication recently.

If there is no evidence of nonadherence, an initial step might be to increase the dosage of the antipsychotic or mood stabilizer that the patient is already taking, ensuring that the dosage is optimized based on FDA indications and clinical trials data. The recommended rate of dosage adjustments differs among medications; however, optimal dosing should be reached quickly because a World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry task force recommends that a mania treatment trial not exceed 2 weeks.10

Dosage increases can be made at weekly visits or sooner, based on treatment response and tolerability. If there is no benefit after optimizing the dosage, the next step would be to add a mood stabilizer to a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA), or vice versa to promote additive or synergistic medication effects.11 Switching one medication for the other should be avoided unless there are tolerability concerns.

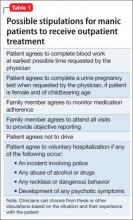

For a patient who is not taking any medications, select a treatment that balances rapid stabilization with long-term efficacy and tolerability. Table 2 lists FDA-approved treatments for mania. Lamotrigine provides prophylactic efficacy with few associated risks, but it has no anti-manic effects and would be a poor choice for most actively manic patients. Most studies indicate that antipsychotics work faster than lithium at the 1-week mark; however, this may be a function of the lithium titration schedule followed in the protocols, the severity of mania among enrolled patients, the inclusion of typically non-responsive manic patients (eg, mixed) in the analysis, and the antipsychotic’s sedative potential relative to lithium. Although the anti-manic and prophylactic potential of lithium and valproate might make them an ideal first-line option, antipsychotics could stabilize a manic patient faster, especially if agitation is present.12,13

Breaking mania quickly is important when treating patients in the outpatient setting. In these situations, a reasonable choice is to prescribe a SGA, because of their rapid onset of effect, low potential for switch to depression, and utility in treating classic, mixed, or psychotic mania.10 Oral loading of valproate (20 mg/kg) is another option. An inpatient study that used an oral-loading strategy demonstrated a similar time to response as olanzapine,14 in contrast to an inpatient15 and an outpatient study16 that employed a standard starting dosage for each patient and led to slower improvement compared with olanzapine.

SGAs should be dosed moderately and lower than if the patient were hospitalized, to avoid alienating the patient from treatment by causing intolerable side effects. In particular, patients and their families should be warned about immediate risks, such as orthostasis or extrapyramidal symptoms. Although treatment guidelines recommend combination therapy as a possible first-line option,9 in the outpatient setting, monotherapy with an optimally dosed, rapid-acting agent is preferred to promote medication adherence and avoid potentially dangerous sedation. Manic patients experience increased distractibility and verbal memory and executive function impairments that can interfere with medication adherence.17 Therefore, patients are more likely to follow a simpler regimen. If SGA or valproate monotherapy does not control mania, begin combination treatment with a mood stabilizer and SGA. If the patient experiences remission with SGA monotherapy, the risks and benefits of maintaining the SGA vs switching to a mood stabilizer can be discussed.

Provide medication “as needed” for agitation—additional SGA dosing or a benzodiazepine—and explain to family members when their use is warranted. Benzodiazepines can provide short-term benefits for manic patients: anxiety relief, sedation, and anti-manic efficacy as monotherapy18-20 and in combination with other medications.21 Studies showing monotherapy efficacy employed high dosages of benzodiazepines (lorazepam mean dosage, 14 mg/d; clonazepam mean dosage, 13 mg/d)19 and high dosages of antipsychotics as needed,18,20 and often were associated with excessive sedation and ataxia.18,19 This makes benzodiazepine monotherapy a potentially dangerous approach for outpatient treatment of mania. IM lorazepam treated manic agitation less quickly than IM olanzapine, suggesting that SGAs are preferable in the outpatient setting because rapid control of agitation is crucial.22 If prescribed, a trusted family member should dispense benzodiazepines to the patient to minimize misuse because of impulsivity, distractibility, desperation to sleep, or pleasure seeking.

SGAs have the benefit of sedation but occasionally additional sleep medications are required. Benzodiazepine receptor agonists (BzRAs), such as zolpidem, eszopiclone, and zaleplon, should be used with caution. Although these medicines are effective in treating insomnia in individuals with primary insomnia23 and major depression,24 they have not been studied in manic patients. The decreased need for sleep in mania is phenomenologically25 and perhaps biologically different than insomnia in major depression.26 Therefore, mania-associated sleep disturbance might not respond to BZRAs. BzRAs also might induce somnambulism and other parasomnias,27 especially when used in combination with psychotropics, such as valproate28; it is unclear if the manic state itself increases this risk further. Sedating antihistamines with anticholinergic blockade, such as diphenhydramine and low dosages (<100 mg/d) of quetiapine, are best used only in combination with anti-manic medications because of putative link between anticholinergic blockade and manic induction.29 Less studied but safer options include novel anticonvulsants (gabapentin, pregabalin), melatonin, and melatonin receptor agonists. Sedating antidepressants, such as mirtazapine and trazodone, should be avoided.25

Important adjunctive treatment steps include discontinuing all pro-manic agents, including antidepressants, stimulants, and steroids, and discouraging use of caffeine, energy drinks, illicit drugs, and alcohol. The patient should return for office visits at least weekly, and possibly more frequently, depending on severity. Telephone check-in calls between scheduled visits may be necessary until the mania is broken.

Psychotherapy. Other than supportive therapy and psychoeducation, other forms of psychotherapy during mania are not indicated. Psychotherapy trials in bipolar disorder do not inform anti-manic efficacy because few have enrolled acutely manic patients and most report long-term benefits rather than short-term efficacy for the index manic episode.30 Educate patients about the importance of maintaining regular social rhythms and taking medication as prescribed. Manic patients might not be aware that they are acting differently during manic episodes, therefore efforts to improve the patient’s insight are unlikely to succeed. More time should be spent emphasizing the importance of adherence to treatment and taking anti-manic medications as prescribed. This discussion can be enhanced by focusing on the medication’s potential to reduce the unpleasant symptoms of mania, including irritability, insomnia, anxiety, and racing thoughts. At the first visit, discuss setting boundaries with the patient to reduce mania-driven, intrusive phone calls. A patient might develop insight after mania has resolved and he (she) can appreciate social or economic harm that occurred while manic. This discussion might foster adherence to maintenance treatment. Advise your patient to limit activities that may increase stimulation and perpetuate the mania, such as exercise, parties, concerts, or crowded shopping malls. Also, recommend that your patient stop working temporarily, to reduce stress and prevent any manic-driven interactions that could result in job loss.

If your patient has an established relationship with a psychotherapist, discuss with the therapist the plan to initiate mania treatment in the outpatient setting and work as a collaborative team, assuming that the patient has granted permission to share information. Encourage the therapist to increase the frequency of sessions with the patient to enable greater monitoring of changes in the patient’s manic symptoms.

Family involvement

Family support is crucial when treating mania in the outpatient setting. Lacking insight and organization, manic patients require the “auxiliary” judgment of trusted family members to ensure treatment success. The family should identify a single person to act as the liaison between the family and the psychiatrist. The psychiatrist should instruct this individual to accompany the patient to each clinic visit and provide regular updates on the patient’s adherence to treatment, changes in symptoms, and any new behaviors that would justify involuntary hospitalization. The treatment plan should be clearly communicated to this individual to ensure that it is implemented correctly. Ideally, this individual would be someone who understands that bipolar disorder is a mental illness, who can tolerate the patient’s potential resentment of them for taking on this role, and who can influence the patient and the other family members to adhere to the treatment plan.

This family member also should watch the patient take medication to rule out nonadherence if the patient’s condition does not improve.

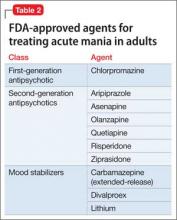

Provide extensive psychoeducation to the family (Table 3). Discuss these teaching points and their implications at length during the first visit and reinforce them at subsequent visits. Advise spouses that the acute manic period is not the time to make major decisions about their marriage or to engage in couple’s therapy. These options are better explored after the patient recovers from the manic episode.

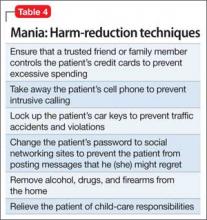

Encourage the family to engage in mania harm-reduction techniques to the extent that the patient will allow (Table 4). In particular, they should hold onto their loved one’s credit cards and checkbook, and discourage the patient from making any major financial decisions until the mania has resolved. Additionally, patients should be relieved of childcare responsibilities during this period. If there are any child welfare safety concerns, the clinician will need to report this to authorities as required by local laws.

Advise family members or roommates to call emergency services and request a crisis intervention team, or to take the patient to an emergency room if he (she) makes verbal threats to harm themselves or others, is violent, or demonstrates behaviors that indicate that he is no longer able to care for himself. The psychiatrist should assist with completing Family and Medical Leave Act paperwork for family members who will monitor the patient at home, a work-excuse letter for the patient so he does not lose his job, and short-term disability paperwork to ensure income for the patient during the manic period.

These interventions can be challenging for the entire family system because they place family members in a paternalistic role and reduce the patient’s autonomy within the family. This is problematic when these role changes occur between spouses or between a patient-parent and his (her) children. Such changes typically need to be reversed over time and may require the help of a family or couple’s therapist. To support the psychological health of the patient’s family, refer them to the National Alliance on Mental Illness for family support groups or to individual psychotherapists.

Outpatient management can be rewarding

For “non-dangerous” manic patients who cannot be hospitalized involuntarily and refuse full or partial hospitalization, a psychiatrist must choose between beginning treatment in the clinic and referring the patient to another provider. The latter option is consistent with the APA’s ethical guidelines,31 but must be done appropriately to avoid legal liability.32 This decision may disappoint a family desperate to see their loved one recover quickly and may leave them feeling betrayed by the mental health system. On the other hand, choosing to treat mania in the outpatient setting can be rewarding when resolution of mania restores the family’s homeostasis.

To achieve this outcome, the outpatient psychiatrist must engage the patient’s family to ensure that the patient adheres to the treatment plan and monitor for potentially dangerous behavior. The psychiatrist also must use his knowledge of mood symptoms, cognitive impairments, and the psychological experience of manic patients to create a safe and effective treatment strategy that the patient and family can implement.

Because of mania’s unpredictability and destructive potential, psychiatrists who agree to treat manic patients as outpatients should be familiar with their state’s statutes and case law that pertain to the refusal to accept a new patient, patient abandonment, involuntary hospitalization, confidentiality, and mandatory reporting. They also should seek clinical or legal consultation if they feel overwhelmed or uncertain about the safest and most legally sound approach.

Bottom Line

Treating mania in the outpatient setting is risky but can be accomplished in select patients with the help of the patient’s family and a strategy that integrates evidence-based pharmacotherapeutic and psychotherapeutic strategies. Because manic patients could display dangerous behavior, be familiar with your state’s laws regarding involuntary commitment, patient abandonment, and mandatory reporting.

Related Resources

• National Alliance on Mental Illness. www.NAMI.org.

• Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance. www.DBSAlliance.org.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Mirtazapine • Remeron

Asenapine • Saphris Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Carbamazepine • Equetro, Tegretol Pregabalin • Lyrica

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine Quetiapine • Seroquel

Clonazepam • Klonopin Risperidone • Risperdal

Diphrenhydramine • Benadryl Trazodone • Desyrel

Eszopiclone • Lunesta Valproate • Divalproex

Gabapentin • Neurontin Zaleplon • Sonata

Lamotrigine • Lamictal Ziprasidone • Geodon

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid Zolpidem • Ambien

Lorazepam • Ativan

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Peter Ash, MD, for carefully reviewing this manuscript and providing feedback.

Disclosures

Dr. Rakofsky receives research or grant support from Takeda. Dr. Dunlop receives research or grant support from Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, and Otsuka.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Cassidy F, Murry E, Forest K, et al. Signs and symptoms of mania in pure and mixed episodes. J Affect Disord. 1998;50(2-3):187-201.

3. Yen CF, Chen CS, Ko CH, et al. Changes in insight among patients with bipolar I disorder: a 2-year prospective study. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(3):238-242.

4. Ng F, Mammen OK, Wilting I, et al. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) consensus guidelines for the safety monitoring of bipolar disorder treatments. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(6):559-595.

5. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(suppl 4):1-50.

6. Allison JB, Wilson WP. Sexual behavior of manic patients: a preliminary report. South Med J. 1960;53:870-874.

7. Cipriani A, Barbui C, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antimanic drugs in acute mania: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011; 378(9799):1306-1315.

8. Yildiz A, Vieta E, Leucht S, et al. Efficacy of antimanic treatments: meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36(2):375-389.

9. Nivoli AM, Murru A, Goikolea JM, et al. New treatment guidelines for acute bipolar mania: a critical review. J Affect Disord. 2012;140(2):125-141.

10. Grunze H, Vieta E, Goodwin GM, et al. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of bipolar disorders: update 2009 on the treatment of acute mania. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2009;10(2):85-116.

11. Tohen M, Chengappa KN, Suppes T, et al. Efficacy of olanzapine in combination with valproate or lithium in the treatment of mania in patients partially nonresponsive to valproate or lithium monotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(1):62-69.

12. Tohen M, Jacobs TG, Feldman PD. Onset of action of antipsychotics in the treatment of mania. Bipolar Disord. 2000;2(3 pt 2):261-268.

13. Goikolea JM, Colom F, Capapey J, et al. Faster onset of antimanic action with haloperidol compared to second-generation antipsychotics. A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials in acute mania. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23(4):305-316.

14. Zajecka JM, Weisler R, Sachs G, et al. A comparison of the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of divalproex sodium and olanzapine in the treatment of bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(12):1148-1155.

15. Tohen M, Baker RW, Altshuler LL, et al. Olanzapine versus divalproex in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(6):1011-1017.

16. Tohen M, Vieta E, Goodwin GM, et al. Olanzapine versus divalproex versus placebo in the treatment of mild to moderate mania: a randomized, 12-week, double-blind study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(11):1776-1789.

17. Martínez-Arán A, Vieta E, Reinares M, et al. Cognitive function across manic or hypomanic, depressed, and euthymic states in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004; 161(2):262-270.

18. Edwards R, Stephenson U, Flewett T. Clonazepam in acute mania: a double blind trial. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1991;25(2):238-242.

19. Bradwejn J, Shriqui C, Koszycki D, et al. Double-blind comparison of the effects of clonazepam and lorazepam in acute mania. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1990;10(6):403-408.

20. Clark HM, Berk M, Brook S. A randomized controlled single blind study of the efficacy of clonazepam and lithium in the treatment of acute mania. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 1997;12(4):325-328.

21. Lenox RH, Newhouse PA, Creelman WL, et al. Adjunctive treatment of manic agitation with lorazepam versus haloperidol: a double-blind study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1992;53(2):47-52.

22. Meehan K, Zhang F, David S, et al. A double-blind, randomized comparison of the efficacy and safety of intramuscular injections of olanzapine, lorazepam, or placebo in treating acutely agitated patients diagnosed with bipolar mania. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;21(4):389-397.

23. Huedo-Medina TB, Kirsch I, Middlemass J, et al. Effectiveness of non-benzodiazepine hypnotics in treatment of adult insomnia: meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration. BMJ. 2012;345:e8343. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e8343.

24. Fava M, Asnis GM, Shrivastava RK, et al. Improved insomnia symptoms and sleep-related next-day functioning in patients with comorbid major depressive disorder and insomnia following concomitant zolpidem extended-release 12.5 mg and escitalopram treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(7):914-928.

25. Plante DT, Winkelman JW. Sleep disturbance in bipolar disorder: therapeutic implications. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(7):830-843.

26. Linkowski P, Kerkhofs M, Rielaert C, et al. Sleep during mania in manic-depressive males. Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 1986;235(6):339-341.

27. Poceta JS. Zolpidem ingestion, automatisms, and sleep driving: a clinical and legal case series. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7(6):632-638.

28. Sattar SP, Ramaswamy S, Bhatia SC, et al. Somnambulism due to probable interaction of valproic acid and zolpidem. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37(10):1429-1433.

29. Rybakowski JK, Koszewska I, Puzynski S. Anticholinergic mechanisms: a forgotten cause of the switch process in bipolar disorder [Comment on: The neurolobiology of the switch process in bipolar disorder: a review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010]. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(12):1698-1699; author reply 1699-1700.

30. Miklowitz DJ. Adjunctive psychotherapy for bipolar disorder: state of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(11):1408-1419.

31. American Psychiatric Association. The principles of medical ethics with annotations especially applicable to psychiatry. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

32. Simon RI, Shuman DW. Clinical manual of psychiatry and law. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2007:17-36.

Manic episodes, by definition, are associated with significant social or occupational impairment.1 Some manic patients are violent or engage in reckless behaviors that can harm themselves or others, such as speeding, disrupting traffic, or playing with fire. When these patients present to a psychiatrist’s outpatient practice, involuntary hospitalization might be justified.

However, some manic patients, in spite of their elevated, expansive, or irritable mood state, never behave dangerously and might not meet legal criteria for involuntary hospitalization, although these criteria differ from state to state. These patients might see a psychiatrist because manic symptoms such as irritability, talkativeness, and impulsivity are bothersome to their family members but pose no serious danger (Box). In this situation, the psychiatrist can strongly encourage the patient to seek voluntary hospitalization or attend a partial hospitalization program. If the patient declines, the psychiatrist is left with 2 choices: initiate treatment in the outpatient setting or refuse to treat the patient and refer to another provider.

Treating “non-dangerous” mania in the outpatient setting is fraught with challenges:

• the possibility that the patient’s condition will progress to dangerousness

• poor adherence to treatment because of the patient’s limited insight

• the large amount of time required from the psychiatrist and care team to adequately manage the manic episode (eg, time spent with family members, frequent patient visits, and managing communications from the patient).

There are no guidelines to assist the office-based practitioner in treating mania in the outpatient setting. When considering dosing and optimal medication combinations for treating mania, clinical trials may be of limited value because most of these studies only included hospitalized manic patients.

Because of this dearth of knowledge, we provide recommendations based on our review of the literature and from our experience working with manic patients who refuse voluntary hospitalization and could not be hospitalized against their will. These recommendations are organized into 3 sections: diagnostic approach, treatment strategy, and family involvement.

Diagnostic approach

Making a diagnosis of mania might seem straightforward for clinicians who work in inpatient settings; however, mania might not present with classic florid symptoms among outpatients. Patients might have a chief concern of irritability, dysphoria, anxiety, or “insomnia,” which may lead clinicians to focus initially on non-bipolar conditions.2

During the interview, it is important to assess for any current DSM-5 symptoms of a manic episode, while being careful not to accept a patient’s denial of symptoms. Patients with mania often have poor insight and are unaware of changes from their baseline state when manic.3 Alternatively, manic patients may want you to believe that they are well and could minimize or deny all symptoms. Therefore, it is important to pay attention to mental status examination findings, such as hyperverbal speech, elated affect, psychomotor agitation, a tangential thought process, or flight of ideas.

Countertransference feelings of diagnostic confusion or frustration after long patient monologues or multiple interruptions by the patient should be incorporated into the diagnostic assessment. Family members or friends often can provide objective observations of behavioral changes necessary to secure the diagnosis.

Treatment strategy

Decision points. When treating manic outpatients, assess the need for hospitalization at each visit. Advantages of the inpatient setting include:

• the possibility of rapid medication adjustments

• continuous observation to ensure the patient’s safety

• keeping the patient temporarily removed from his community to prevent irreversible social and economic harms.

However, a challenge with hospitalization is third-party payers’ influence on a patient’s length of stay, which may lead to rapid medication changes that may not be clinically ideal.

At each outpatient visit, explore with the patient and family emerging symptoms that could justify involuntary hospitalization. Document whether you recommended inpatient hospitalization, the patient’s response to the recommendation, that you are aware and have considered the risks associated with outpatient care, and that you have discussed these risks with the patient and family.

For patients well-known to the psychiatrist, a history of dangerous mania may lead him (her) to strongly recommend hospitalization, whereas a pre-existing therapeutic alliance and no current or distant history of dangerous mania may lead the clinician to look for alternatives to inpatient care. Concomitant drug or alcohol use may increase the likelihood of mania becoming dangerous, making outpatient treatment ill-advised and riskier for everyone involved.

In exchange for agreeing to provide outpatient care for mania, it often is helpful to negotiate with the patient and family a threshold level of symptoms or behavior that will result in the patient agreeing to voluntary hospitalization (Table 1). Such an agreement can include stopping outpatient treatment if the patient does not improve significantly after 2 or 3 weeks or develops psychotic symptoms. The negotiation also can include partial hospitalization as an option, so long as the patient’s mania continues to be non-dangerous.

Obtaining pretreatment blood work can help a clinician determine whether a medication is safe to prescribe and establish causality if laboratory abnormalities arise after treatment begins. Ideally, the psychiatrist should follow consensus guidelines developed by the International Society for Bipolar Disorders4 or the American Psychiatric Association (APA)5 and order appropriate laboratory tests before prescribing anti-manic medications. Determine the pregnancy status of female patients of child-bearing age before prescribing a potentially teratogenic medication, especially because mania is associated with increased libido.6

Manic patients might be too disorganized to follow up with recommendations for laboratory testing, or could wait several days before completing blood work. Although not ideal, to avoid delaying treatment, a clinician might need to prescribe medication at the initial office visit, without pretreatment laboratory results. When the patient is more organized, complete the blood work. Keeping home pregnancy tests in the office can help rule out pregnancy before prescribing medication.

Medication. Meta-analyses have established the efficacy of mood stabilizers and antipsychotics for treating mania,7,8 and several consensus guidelines have incorporated these findings into treatment algorithms.9

For a patient already taking medications recommended by the guidelines, assess treatment adherence during the initial interview by questioning the patient and family. When the logistics of phlebotomy permit, obtaining the blood level of psychotropics can show the presence of any detectable drug concentration, which demonstrates that the patient has taken the medication recently.

If there is no evidence of nonadherence, an initial step might be to increase the dosage of the antipsychotic or mood stabilizer that the patient is already taking, ensuring that the dosage is optimized based on FDA indications and clinical trials data. The recommended rate of dosage adjustments differs among medications; however, optimal dosing should be reached quickly because a World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry task force recommends that a mania treatment trial not exceed 2 weeks.10

Dosage increases can be made at weekly visits or sooner, based on treatment response and tolerability. If there is no benefit after optimizing the dosage, the next step would be to add a mood stabilizer to a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA), or vice versa to promote additive or synergistic medication effects.11 Switching one medication for the other should be avoided unless there are tolerability concerns.

For a patient who is not taking any medications, select a treatment that balances rapid stabilization with long-term efficacy and tolerability. Table 2 lists FDA-approved treatments for mania. Lamotrigine provides prophylactic efficacy with few associated risks, but it has no anti-manic effects and would be a poor choice for most actively manic patients. Most studies indicate that antipsychotics work faster than lithium at the 1-week mark; however, this may be a function of the lithium titration schedule followed in the protocols, the severity of mania among enrolled patients, the inclusion of typically non-responsive manic patients (eg, mixed) in the analysis, and the antipsychotic’s sedative potential relative to lithium. Although the anti-manic and prophylactic potential of lithium and valproate might make them an ideal first-line option, antipsychotics could stabilize a manic patient faster, especially if agitation is present.12,13

Breaking mania quickly is important when treating patients in the outpatient setting. In these situations, a reasonable choice is to prescribe a SGA, because of their rapid onset of effect, low potential for switch to depression, and utility in treating classic, mixed, or psychotic mania.10 Oral loading of valproate (20 mg/kg) is another option. An inpatient study that used an oral-loading strategy demonstrated a similar time to response as olanzapine,14 in contrast to an inpatient15 and an outpatient study16 that employed a standard starting dosage for each patient and led to slower improvement compared with olanzapine.

SGAs should be dosed moderately and lower than if the patient were hospitalized, to avoid alienating the patient from treatment by causing intolerable side effects. In particular, patients and their families should be warned about immediate risks, such as orthostasis or extrapyramidal symptoms. Although treatment guidelines recommend combination therapy as a possible first-line option,9 in the outpatient setting, monotherapy with an optimally dosed, rapid-acting agent is preferred to promote medication adherence and avoid potentially dangerous sedation. Manic patients experience increased distractibility and verbal memory and executive function impairments that can interfere with medication adherence.17 Therefore, patients are more likely to follow a simpler regimen. If SGA or valproate monotherapy does not control mania, begin combination treatment with a mood stabilizer and SGA. If the patient experiences remission with SGA monotherapy, the risks and benefits of maintaining the SGA vs switching to a mood stabilizer can be discussed.

Provide medication “as needed” for agitation—additional SGA dosing or a benzodiazepine—and explain to family members when their use is warranted. Benzodiazepines can provide short-term benefits for manic patients: anxiety relief, sedation, and anti-manic efficacy as monotherapy18-20 and in combination with other medications.21 Studies showing monotherapy efficacy employed high dosages of benzodiazepines (lorazepam mean dosage, 14 mg/d; clonazepam mean dosage, 13 mg/d)19 and high dosages of antipsychotics as needed,18,20 and often were associated with excessive sedation and ataxia.18,19 This makes benzodiazepine monotherapy a potentially dangerous approach for outpatient treatment of mania. IM lorazepam treated manic agitation less quickly than IM olanzapine, suggesting that SGAs are preferable in the outpatient setting because rapid control of agitation is crucial.22 If prescribed, a trusted family member should dispense benzodiazepines to the patient to minimize misuse because of impulsivity, distractibility, desperation to sleep, or pleasure seeking.

SGAs have the benefit of sedation but occasionally additional sleep medications are required. Benzodiazepine receptor agonists (BzRAs), such as zolpidem, eszopiclone, and zaleplon, should be used with caution. Although these medicines are effective in treating insomnia in individuals with primary insomnia23 and major depression,24 they have not been studied in manic patients. The decreased need for sleep in mania is phenomenologically25 and perhaps biologically different than insomnia in major depression.26 Therefore, mania-associated sleep disturbance might not respond to BZRAs. BzRAs also might induce somnambulism and other parasomnias,27 especially when used in combination with psychotropics, such as valproate28; it is unclear if the manic state itself increases this risk further. Sedating antihistamines with anticholinergic blockade, such as diphenhydramine and low dosages (<100 mg/d) of quetiapine, are best used only in combination with anti-manic medications because of putative link between anticholinergic blockade and manic induction.29 Less studied but safer options include novel anticonvulsants (gabapentin, pregabalin), melatonin, and melatonin receptor agonists. Sedating antidepressants, such as mirtazapine and trazodone, should be avoided.25

Important adjunctive treatment steps include discontinuing all pro-manic agents, including antidepressants, stimulants, and steroids, and discouraging use of caffeine, energy drinks, illicit drugs, and alcohol. The patient should return for office visits at least weekly, and possibly more frequently, depending on severity. Telephone check-in calls between scheduled visits may be necessary until the mania is broken.

Psychotherapy. Other than supportive therapy and psychoeducation, other forms of psychotherapy during mania are not indicated. Psychotherapy trials in bipolar disorder do not inform anti-manic efficacy because few have enrolled acutely manic patients and most report long-term benefits rather than short-term efficacy for the index manic episode.30 Educate patients about the importance of maintaining regular social rhythms and taking medication as prescribed. Manic patients might not be aware that they are acting differently during manic episodes, therefore efforts to improve the patient’s insight are unlikely to succeed. More time should be spent emphasizing the importance of adherence to treatment and taking anti-manic medications as prescribed. This discussion can be enhanced by focusing on the medication’s potential to reduce the unpleasant symptoms of mania, including irritability, insomnia, anxiety, and racing thoughts. At the first visit, discuss setting boundaries with the patient to reduce mania-driven, intrusive phone calls. A patient might develop insight after mania has resolved and he (she) can appreciate social or economic harm that occurred while manic. This discussion might foster adherence to maintenance treatment. Advise your patient to limit activities that may increase stimulation and perpetuate the mania, such as exercise, parties, concerts, or crowded shopping malls. Also, recommend that your patient stop working temporarily, to reduce stress and prevent any manic-driven interactions that could result in job loss.

If your patient has an established relationship with a psychotherapist, discuss with the therapist the plan to initiate mania treatment in the outpatient setting and work as a collaborative team, assuming that the patient has granted permission to share information. Encourage the therapist to increase the frequency of sessions with the patient to enable greater monitoring of changes in the patient’s manic symptoms.

Family involvement

Family support is crucial when treating mania in the outpatient setting. Lacking insight and organization, manic patients require the “auxiliary” judgment of trusted family members to ensure treatment success. The family should identify a single person to act as the liaison between the family and the psychiatrist. The psychiatrist should instruct this individual to accompany the patient to each clinic visit and provide regular updates on the patient’s adherence to treatment, changes in symptoms, and any new behaviors that would justify involuntary hospitalization. The treatment plan should be clearly communicated to this individual to ensure that it is implemented correctly. Ideally, this individual would be someone who understands that bipolar disorder is a mental illness, who can tolerate the patient’s potential resentment of them for taking on this role, and who can influence the patient and the other family members to adhere to the treatment plan.

This family member also should watch the patient take medication to rule out nonadherence if the patient’s condition does not improve.

Provide extensive psychoeducation to the family (Table 3). Discuss these teaching points and their implications at length during the first visit and reinforce them at subsequent visits. Advise spouses that the acute manic period is not the time to make major decisions about their marriage or to engage in couple’s therapy. These options are better explored after the patient recovers from the manic episode.

Encourage the family to engage in mania harm-reduction techniques to the extent that the patient will allow (Table 4). In particular, they should hold onto their loved one’s credit cards and checkbook, and discourage the patient from making any major financial decisions until the mania has resolved. Additionally, patients should be relieved of childcare responsibilities during this period. If there are any child welfare safety concerns, the clinician will need to report this to authorities as required by local laws.

Advise family members or roommates to call emergency services and request a crisis intervention team, or to take the patient to an emergency room if he (she) makes verbal threats to harm themselves or others, is violent, or demonstrates behaviors that indicate that he is no longer able to care for himself. The psychiatrist should assist with completing Family and Medical Leave Act paperwork for family members who will monitor the patient at home, a work-excuse letter for the patient so he does not lose his job, and short-term disability paperwork to ensure income for the patient during the manic period.

These interventions can be challenging for the entire family system because they place family members in a paternalistic role and reduce the patient’s autonomy within the family. This is problematic when these role changes occur between spouses or between a patient-parent and his (her) children. Such changes typically need to be reversed over time and may require the help of a family or couple’s therapist. To support the psychological health of the patient’s family, refer them to the National Alliance on Mental Illness for family support groups or to individual psychotherapists.

Outpatient management can be rewarding

For “non-dangerous” manic patients who cannot be hospitalized involuntarily and refuse full or partial hospitalization, a psychiatrist must choose between beginning treatment in the clinic and referring the patient to another provider. The latter option is consistent with the APA’s ethical guidelines,31 but must be done appropriately to avoid legal liability.32 This decision may disappoint a family desperate to see their loved one recover quickly and may leave them feeling betrayed by the mental health system. On the other hand, choosing to treat mania in the outpatient setting can be rewarding when resolution of mania restores the family’s homeostasis.

To achieve this outcome, the outpatient psychiatrist must engage the patient’s family to ensure that the patient adheres to the treatment plan and monitor for potentially dangerous behavior. The psychiatrist also must use his knowledge of mood symptoms, cognitive impairments, and the psychological experience of manic patients to create a safe and effective treatment strategy that the patient and family can implement.

Because of mania’s unpredictability and destructive potential, psychiatrists who agree to treat manic patients as outpatients should be familiar with their state’s statutes and case law that pertain to the refusal to accept a new patient, patient abandonment, involuntary hospitalization, confidentiality, and mandatory reporting. They also should seek clinical or legal consultation if they feel overwhelmed or uncertain about the safest and most legally sound approach.

Bottom Line

Treating mania in the outpatient setting is risky but can be accomplished in select patients with the help of the patient’s family and a strategy that integrates evidence-based pharmacotherapeutic and psychotherapeutic strategies. Because manic patients could display dangerous behavior, be familiar with your state’s laws regarding involuntary commitment, patient abandonment, and mandatory reporting.

Related Resources

• National Alliance on Mental Illness. www.NAMI.org.

• Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance. www.DBSAlliance.org.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Mirtazapine • Remeron

Asenapine • Saphris Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Carbamazepine • Equetro, Tegretol Pregabalin • Lyrica

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine Quetiapine • Seroquel

Clonazepam • Klonopin Risperidone • Risperdal

Diphrenhydramine • Benadryl Trazodone • Desyrel

Eszopiclone • Lunesta Valproate • Divalproex

Gabapentin • Neurontin Zaleplon • Sonata

Lamotrigine • Lamictal Ziprasidone • Geodon

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid Zolpidem • Ambien

Lorazepam • Ativan

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Peter Ash, MD, for carefully reviewing this manuscript and providing feedback.

Disclosures

Dr. Rakofsky receives research or grant support from Takeda. Dr. Dunlop receives research or grant support from Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, and Otsuka.

Manic episodes, by definition, are associated with significant social or occupational impairment.1 Some manic patients are violent or engage in reckless behaviors that can harm themselves or others, such as speeding, disrupting traffic, or playing with fire. When these patients present to a psychiatrist’s outpatient practice, involuntary hospitalization might be justified.

However, some manic patients, in spite of their elevated, expansive, or irritable mood state, never behave dangerously and might not meet legal criteria for involuntary hospitalization, although these criteria differ from state to state. These patients might see a psychiatrist because manic symptoms such as irritability, talkativeness, and impulsivity are bothersome to their family members but pose no serious danger (Box). In this situation, the psychiatrist can strongly encourage the patient to seek voluntary hospitalization or attend a partial hospitalization program. If the patient declines, the psychiatrist is left with 2 choices: initiate treatment in the outpatient setting or refuse to treat the patient and refer to another provider.

Treating “non-dangerous” mania in the outpatient setting is fraught with challenges:

• the possibility that the patient’s condition will progress to dangerousness

• poor adherence to treatment because of the patient’s limited insight

• the large amount of time required from the psychiatrist and care team to adequately manage the manic episode (eg, time spent with family members, frequent patient visits, and managing communications from the patient).

There are no guidelines to assist the office-based practitioner in treating mania in the outpatient setting. When considering dosing and optimal medication combinations for treating mania, clinical trials may be of limited value because most of these studies only included hospitalized manic patients.

Because of this dearth of knowledge, we provide recommendations based on our review of the literature and from our experience working with manic patients who refuse voluntary hospitalization and could not be hospitalized against their will. These recommendations are organized into 3 sections: diagnostic approach, treatment strategy, and family involvement.

Diagnostic approach

Making a diagnosis of mania might seem straightforward for clinicians who work in inpatient settings; however, mania might not present with classic florid symptoms among outpatients. Patients might have a chief concern of irritability, dysphoria, anxiety, or “insomnia,” which may lead clinicians to focus initially on non-bipolar conditions.2

During the interview, it is important to assess for any current DSM-5 symptoms of a manic episode, while being careful not to accept a patient’s denial of symptoms. Patients with mania often have poor insight and are unaware of changes from their baseline state when manic.3 Alternatively, manic patients may want you to believe that they are well and could minimize or deny all symptoms. Therefore, it is important to pay attention to mental status examination findings, such as hyperverbal speech, elated affect, psychomotor agitation, a tangential thought process, or flight of ideas.

Countertransference feelings of diagnostic confusion or frustration after long patient monologues or multiple interruptions by the patient should be incorporated into the diagnostic assessment. Family members or friends often can provide objective observations of behavioral changes necessary to secure the diagnosis.

Treatment strategy

Decision points. When treating manic outpatients, assess the need for hospitalization at each visit. Advantages of the inpatient setting include:

• the possibility of rapid medication adjustments

• continuous observation to ensure the patient’s safety

• keeping the patient temporarily removed from his community to prevent irreversible social and economic harms.

However, a challenge with hospitalization is third-party payers’ influence on a patient’s length of stay, which may lead to rapid medication changes that may not be clinically ideal.

At each outpatient visit, explore with the patient and family emerging symptoms that could justify involuntary hospitalization. Document whether you recommended inpatient hospitalization, the patient’s response to the recommendation, that you are aware and have considered the risks associated with outpatient care, and that you have discussed these risks with the patient and family.

For patients well-known to the psychiatrist, a history of dangerous mania may lead him (her) to strongly recommend hospitalization, whereas a pre-existing therapeutic alliance and no current or distant history of dangerous mania may lead the clinician to look for alternatives to inpatient care. Concomitant drug or alcohol use may increase the likelihood of mania becoming dangerous, making outpatient treatment ill-advised and riskier for everyone involved.

In exchange for agreeing to provide outpatient care for mania, it often is helpful to negotiate with the patient and family a threshold level of symptoms or behavior that will result in the patient agreeing to voluntary hospitalization (Table 1). Such an agreement can include stopping outpatient treatment if the patient does not improve significantly after 2 or 3 weeks or develops psychotic symptoms. The negotiation also can include partial hospitalization as an option, so long as the patient’s mania continues to be non-dangerous.

Obtaining pretreatment blood work can help a clinician determine whether a medication is safe to prescribe and establish causality if laboratory abnormalities arise after treatment begins. Ideally, the psychiatrist should follow consensus guidelines developed by the International Society for Bipolar Disorders4 or the American Psychiatric Association (APA)5 and order appropriate laboratory tests before prescribing anti-manic medications. Determine the pregnancy status of female patients of child-bearing age before prescribing a potentially teratogenic medication, especially because mania is associated with increased libido.6

Manic patients might be too disorganized to follow up with recommendations for laboratory testing, or could wait several days before completing blood work. Although not ideal, to avoid delaying treatment, a clinician might need to prescribe medication at the initial office visit, without pretreatment laboratory results. When the patient is more organized, complete the blood work. Keeping home pregnancy tests in the office can help rule out pregnancy before prescribing medication.

Medication. Meta-analyses have established the efficacy of mood stabilizers and antipsychotics for treating mania,7,8 and several consensus guidelines have incorporated these findings into treatment algorithms.9

For a patient already taking medications recommended by the guidelines, assess treatment adherence during the initial interview by questioning the patient and family. When the logistics of phlebotomy permit, obtaining the blood level of psychotropics can show the presence of any detectable drug concentration, which demonstrates that the patient has taken the medication recently.

If there is no evidence of nonadherence, an initial step might be to increase the dosage of the antipsychotic or mood stabilizer that the patient is already taking, ensuring that the dosage is optimized based on FDA indications and clinical trials data. The recommended rate of dosage adjustments differs among medications; however, optimal dosing should be reached quickly because a World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry task force recommends that a mania treatment trial not exceed 2 weeks.10

Dosage increases can be made at weekly visits or sooner, based on treatment response and tolerability. If there is no benefit after optimizing the dosage, the next step would be to add a mood stabilizer to a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA), or vice versa to promote additive or synergistic medication effects.11 Switching one medication for the other should be avoided unless there are tolerability concerns.

For a patient who is not taking any medications, select a treatment that balances rapid stabilization with long-term efficacy and tolerability. Table 2 lists FDA-approved treatments for mania. Lamotrigine provides prophylactic efficacy with few associated risks, but it has no anti-manic effects and would be a poor choice for most actively manic patients. Most studies indicate that antipsychotics work faster than lithium at the 1-week mark; however, this may be a function of the lithium titration schedule followed in the protocols, the severity of mania among enrolled patients, the inclusion of typically non-responsive manic patients (eg, mixed) in the analysis, and the antipsychotic’s sedative potential relative to lithium. Although the anti-manic and prophylactic potential of lithium and valproate might make them an ideal first-line option, antipsychotics could stabilize a manic patient faster, especially if agitation is present.12,13

Breaking mania quickly is important when treating patients in the outpatient setting. In these situations, a reasonable choice is to prescribe a SGA, because of their rapid onset of effect, low potential for switch to depression, and utility in treating classic, mixed, or psychotic mania.10 Oral loading of valproate (20 mg/kg) is another option. An inpatient study that used an oral-loading strategy demonstrated a similar time to response as olanzapine,14 in contrast to an inpatient15 and an outpatient study16 that employed a standard starting dosage for each patient and led to slower improvement compared with olanzapine.

SGAs should be dosed moderately and lower than if the patient were hospitalized, to avoid alienating the patient from treatment by causing intolerable side effects. In particular, patients and their families should be warned about immediate risks, such as orthostasis or extrapyramidal symptoms. Although treatment guidelines recommend combination therapy as a possible first-line option,9 in the outpatient setting, monotherapy with an optimally dosed, rapid-acting agent is preferred to promote medication adherence and avoid potentially dangerous sedation. Manic patients experience increased distractibility and verbal memory and executive function impairments that can interfere with medication adherence.17 Therefore, patients are more likely to follow a simpler regimen. If SGA or valproate monotherapy does not control mania, begin combination treatment with a mood stabilizer and SGA. If the patient experiences remission with SGA monotherapy, the risks and benefits of maintaining the SGA vs switching to a mood stabilizer can be discussed.

Provide medication “as needed” for agitation—additional SGA dosing or a benzodiazepine—and explain to family members when their use is warranted. Benzodiazepines can provide short-term benefits for manic patients: anxiety relief, sedation, and anti-manic efficacy as monotherapy18-20 and in combination with other medications.21 Studies showing monotherapy efficacy employed high dosages of benzodiazepines (lorazepam mean dosage, 14 mg/d; clonazepam mean dosage, 13 mg/d)19 and high dosages of antipsychotics as needed,18,20 and often were associated with excessive sedation and ataxia.18,19 This makes benzodiazepine monotherapy a potentially dangerous approach for outpatient treatment of mania. IM lorazepam treated manic agitation less quickly than IM olanzapine, suggesting that SGAs are preferable in the outpatient setting because rapid control of agitation is crucial.22 If prescribed, a trusted family member should dispense benzodiazepines to the patient to minimize misuse because of impulsivity, distractibility, desperation to sleep, or pleasure seeking.

SGAs have the benefit of sedation but occasionally additional sleep medications are required. Benzodiazepine receptor agonists (BzRAs), such as zolpidem, eszopiclone, and zaleplon, should be used with caution. Although these medicines are effective in treating insomnia in individuals with primary insomnia23 and major depression,24 they have not been studied in manic patients. The decreased need for sleep in mania is phenomenologically25 and perhaps biologically different than insomnia in major depression.26 Therefore, mania-associated sleep disturbance might not respond to BZRAs. BzRAs also might induce somnambulism and other parasomnias,27 especially when used in combination with psychotropics, such as valproate28; it is unclear if the manic state itself increases this risk further. Sedating antihistamines with anticholinergic blockade, such as diphenhydramine and low dosages (<100 mg/d) of quetiapine, are best used only in combination with anti-manic medications because of putative link between anticholinergic blockade and manic induction.29 Less studied but safer options include novel anticonvulsants (gabapentin, pregabalin), melatonin, and melatonin receptor agonists. Sedating antidepressants, such as mirtazapine and trazodone, should be avoided.25

Important adjunctive treatment steps include discontinuing all pro-manic agents, including antidepressants, stimulants, and steroids, and discouraging use of caffeine, energy drinks, illicit drugs, and alcohol. The patient should return for office visits at least weekly, and possibly more frequently, depending on severity. Telephone check-in calls between scheduled visits may be necessary until the mania is broken.

Psychotherapy. Other than supportive therapy and psychoeducation, other forms of psychotherapy during mania are not indicated. Psychotherapy trials in bipolar disorder do not inform anti-manic efficacy because few have enrolled acutely manic patients and most report long-term benefits rather than short-term efficacy for the index manic episode.30 Educate patients about the importance of maintaining regular social rhythms and taking medication as prescribed. Manic patients might not be aware that they are acting differently during manic episodes, therefore efforts to improve the patient’s insight are unlikely to succeed. More time should be spent emphasizing the importance of adherence to treatment and taking anti-manic medications as prescribed. This discussion can be enhanced by focusing on the medication’s potential to reduce the unpleasant symptoms of mania, including irritability, insomnia, anxiety, and racing thoughts. At the first visit, discuss setting boundaries with the patient to reduce mania-driven, intrusive phone calls. A patient might develop insight after mania has resolved and he (she) can appreciate social or economic harm that occurred while manic. This discussion might foster adherence to maintenance treatment. Advise your patient to limit activities that may increase stimulation and perpetuate the mania, such as exercise, parties, concerts, or crowded shopping malls. Also, recommend that your patient stop working temporarily, to reduce stress and prevent any manic-driven interactions that could result in job loss.

If your patient has an established relationship with a psychotherapist, discuss with the therapist the plan to initiate mania treatment in the outpatient setting and work as a collaborative team, assuming that the patient has granted permission to share information. Encourage the therapist to increase the frequency of sessions with the patient to enable greater monitoring of changes in the patient’s manic symptoms.

Family involvement

Family support is crucial when treating mania in the outpatient setting. Lacking insight and organization, manic patients require the “auxiliary” judgment of trusted family members to ensure treatment success. The family should identify a single person to act as the liaison between the family and the psychiatrist. The psychiatrist should instruct this individual to accompany the patient to each clinic visit and provide regular updates on the patient’s adherence to treatment, changes in symptoms, and any new behaviors that would justify involuntary hospitalization. The treatment plan should be clearly communicated to this individual to ensure that it is implemented correctly. Ideally, this individual would be someone who understands that bipolar disorder is a mental illness, who can tolerate the patient’s potential resentment of them for taking on this role, and who can influence the patient and the other family members to adhere to the treatment plan.

This family member also should watch the patient take medication to rule out nonadherence if the patient’s condition does not improve.

Provide extensive psychoeducation to the family (Table 3). Discuss these teaching points and their implications at length during the first visit and reinforce them at subsequent visits. Advise spouses that the acute manic period is not the time to make major decisions about their marriage or to engage in couple’s therapy. These options are better explored after the patient recovers from the manic episode.

Encourage the family to engage in mania harm-reduction techniques to the extent that the patient will allow (Table 4). In particular, they should hold onto their loved one’s credit cards and checkbook, and discourage the patient from making any major financial decisions until the mania has resolved. Additionally, patients should be relieved of childcare responsibilities during this period. If there are any child welfare safety concerns, the clinician will need to report this to authorities as required by local laws.

Advise family members or roommates to call emergency services and request a crisis intervention team, or to take the patient to an emergency room if he (she) makes verbal threats to harm themselves or others, is violent, or demonstrates behaviors that indicate that he is no longer able to care for himself. The psychiatrist should assist with completing Family and Medical Leave Act paperwork for family members who will monitor the patient at home, a work-excuse letter for the patient so he does not lose his job, and short-term disability paperwork to ensure income for the patient during the manic period.

These interventions can be challenging for the entire family system because they place family members in a paternalistic role and reduce the patient’s autonomy within the family. This is problematic when these role changes occur between spouses or between a patient-parent and his (her) children. Such changes typically need to be reversed over time and may require the help of a family or couple’s therapist. To support the psychological health of the patient’s family, refer them to the National Alliance on Mental Illness for family support groups or to individual psychotherapists.

Outpatient management can be rewarding

For “non-dangerous” manic patients who cannot be hospitalized involuntarily and refuse full or partial hospitalization, a psychiatrist must choose between beginning treatment in the clinic and referring the patient to another provider. The latter option is consistent with the APA’s ethical guidelines,31 but must be done appropriately to avoid legal liability.32 This decision may disappoint a family desperate to see their loved one recover quickly and may leave them feeling betrayed by the mental health system. On the other hand, choosing to treat mania in the outpatient setting can be rewarding when resolution of mania restores the family’s homeostasis.

To achieve this outcome, the outpatient psychiatrist must engage the patient’s family to ensure that the patient adheres to the treatment plan and monitor for potentially dangerous behavior. The psychiatrist also must use his knowledge of mood symptoms, cognitive impairments, and the psychological experience of manic patients to create a safe and effective treatment strategy that the patient and family can implement.

Because of mania’s unpredictability and destructive potential, psychiatrists who agree to treat manic patients as outpatients should be familiar with their state’s statutes and case law that pertain to the refusal to accept a new patient, patient abandonment, involuntary hospitalization, confidentiality, and mandatory reporting. They also should seek clinical or legal consultation if they feel overwhelmed or uncertain about the safest and most legally sound approach.

Bottom Line

Treating mania in the outpatient setting is risky but can be accomplished in select patients with the help of the patient’s family and a strategy that integrates evidence-based pharmacotherapeutic and psychotherapeutic strategies. Because manic patients could display dangerous behavior, be familiar with your state’s laws regarding involuntary commitment, patient abandonment, and mandatory reporting.

Related Resources

• National Alliance on Mental Illness. www.NAMI.org.

• Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance. www.DBSAlliance.org.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Mirtazapine • Remeron

Asenapine • Saphris Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Carbamazepine • Equetro, Tegretol Pregabalin • Lyrica

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine Quetiapine • Seroquel

Clonazepam • Klonopin Risperidone • Risperdal

Diphrenhydramine • Benadryl Trazodone • Desyrel

Eszopiclone • Lunesta Valproate • Divalproex

Gabapentin • Neurontin Zaleplon • Sonata

Lamotrigine • Lamictal Ziprasidone • Geodon

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid Zolpidem • Ambien

Lorazepam • Ativan

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Peter Ash, MD, for carefully reviewing this manuscript and providing feedback.

Disclosures

Dr. Rakofsky receives research or grant support from Takeda. Dr. Dunlop receives research or grant support from Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, and Otsuka.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Cassidy F, Murry E, Forest K, et al. Signs and symptoms of mania in pure and mixed episodes. J Affect Disord. 1998;50(2-3):187-201.

3. Yen CF, Chen CS, Ko CH, et al. Changes in insight among patients with bipolar I disorder: a 2-year prospective study. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(3):238-242.

4. Ng F, Mammen OK, Wilting I, et al. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) consensus guidelines for the safety monitoring of bipolar disorder treatments. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(6):559-595.

5. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(suppl 4):1-50.

6. Allison JB, Wilson WP. Sexual behavior of manic patients: a preliminary report. South Med J. 1960;53:870-874.

7. Cipriani A, Barbui C, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antimanic drugs in acute mania: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011; 378(9799):1306-1315.

8. Yildiz A, Vieta E, Leucht S, et al. Efficacy of antimanic treatments: meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36(2):375-389.

9. Nivoli AM, Murru A, Goikolea JM, et al. New treatment guidelines for acute bipolar mania: a critical review. J Affect Disord. 2012;140(2):125-141.

10. Grunze H, Vieta E, Goodwin GM, et al. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of bipolar disorders: update 2009 on the treatment of acute mania. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2009;10(2):85-116.

11. Tohen M, Chengappa KN, Suppes T, et al. Efficacy of olanzapine in combination with valproate or lithium in the treatment of mania in patients partially nonresponsive to valproate or lithium monotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(1):62-69.

12. Tohen M, Jacobs TG, Feldman PD. Onset of action of antipsychotics in the treatment of mania. Bipolar Disord. 2000;2(3 pt 2):261-268.

13. Goikolea JM, Colom F, Capapey J, et al. Faster onset of antimanic action with haloperidol compared to second-generation antipsychotics. A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials in acute mania. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23(4):305-316.

14. Zajecka JM, Weisler R, Sachs G, et al. A comparison of the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of divalproex sodium and olanzapine in the treatment of bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(12):1148-1155.

15. Tohen M, Baker RW, Altshuler LL, et al. Olanzapine versus divalproex in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(6):1011-1017.

16. Tohen M, Vieta E, Goodwin GM, et al. Olanzapine versus divalproex versus placebo in the treatment of mild to moderate mania: a randomized, 12-week, double-blind study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(11):1776-1789.

17. Martínez-Arán A, Vieta E, Reinares M, et al. Cognitive function across manic or hypomanic, depressed, and euthymic states in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004; 161(2):262-270.

18. Edwards R, Stephenson U, Flewett T. Clonazepam in acute mania: a double blind trial. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1991;25(2):238-242.

19. Bradwejn J, Shriqui C, Koszycki D, et al. Double-blind comparison of the effects of clonazepam and lorazepam in acute mania. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1990;10(6):403-408.

20. Clark HM, Berk M, Brook S. A randomized controlled single blind study of the efficacy of clonazepam and lithium in the treatment of acute mania. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 1997;12(4):325-328.

21. Lenox RH, Newhouse PA, Creelman WL, et al. Adjunctive treatment of manic agitation with lorazepam versus haloperidol: a double-blind study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1992;53(2):47-52.

22. Meehan K, Zhang F, David S, et al. A double-blind, randomized comparison of the efficacy and safety of intramuscular injections of olanzapine, lorazepam, or placebo in treating acutely agitated patients diagnosed with bipolar mania. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;21(4):389-397.

23. Huedo-Medina TB, Kirsch I, Middlemass J, et al. Effectiveness of non-benzodiazepine hypnotics in treatment of adult insomnia: meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration. BMJ. 2012;345:e8343. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e8343.

24. Fava M, Asnis GM, Shrivastava RK, et al. Improved insomnia symptoms and sleep-related next-day functioning in patients with comorbid major depressive disorder and insomnia following concomitant zolpidem extended-release 12.5 mg and escitalopram treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(7):914-928.

25. Plante DT, Winkelman JW. Sleep disturbance in bipolar disorder: therapeutic implications. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(7):830-843.

26. Linkowski P, Kerkhofs M, Rielaert C, et al. Sleep during mania in manic-depressive males. Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 1986;235(6):339-341.

27. Poceta JS. Zolpidem ingestion, automatisms, and sleep driving: a clinical and legal case series. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7(6):632-638.

28. Sattar SP, Ramaswamy S, Bhatia SC, et al. Somnambulism due to probable interaction of valproic acid and zolpidem. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37(10):1429-1433.

29. Rybakowski JK, Koszewska I, Puzynski S. Anticholinergic mechanisms: a forgotten cause of the switch process in bipolar disorder [Comment on: The neurolobiology of the switch process in bipolar disorder: a review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010]. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(12):1698-1699; author reply 1699-1700.

30. Miklowitz DJ. Adjunctive psychotherapy for bipolar disorder: state of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(11):1408-1419.

31. American Psychiatric Association. The principles of medical ethics with annotations especially applicable to psychiatry. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

32. Simon RI, Shuman DW. Clinical manual of psychiatry and law. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2007:17-36.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Cassidy F, Murry E, Forest K, et al. Signs and symptoms of mania in pure and mixed episodes. J Affect Disord. 1998;50(2-3):187-201.

3. Yen CF, Chen CS, Ko CH, et al. Changes in insight among patients with bipolar I disorder: a 2-year prospective study. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(3):238-242.

4. Ng F, Mammen OK, Wilting I, et al. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) consensus guidelines for the safety monitoring of bipolar disorder treatments. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(6):559-595.

5. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(suppl 4):1-50.

6. Allison JB, Wilson WP. Sexual behavior of manic patients: a preliminary report. South Med J. 1960;53:870-874.

7. Cipriani A, Barbui C, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antimanic drugs in acute mania: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011; 378(9799):1306-1315.

8. Yildiz A, Vieta E, Leucht S, et al. Efficacy of antimanic treatments: meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36(2):375-389.

9. Nivoli AM, Murru A, Goikolea JM, et al. New treatment guidelines for acute bipolar mania: a critical review. J Affect Disord. 2012;140(2):125-141.

10. Grunze H, Vieta E, Goodwin GM, et al. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of bipolar disorders: update 2009 on the treatment of acute mania. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2009;10(2):85-116.