User login

Type 1 neurofibromatosis (NF1), or von Recklinghausen disease, is a multisystem disorder affecting approximately 1 in 3500 people in South East Wales.1 Type 1 neurofibromatosis has been described in the literature since the 13th century but was not recognized as a distinct disorder until 1882 in Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen’s landmark publication “On Multiple Fibromas of the Skin and Their Relationship to Multiple Neuromas.”2

Genetics

Type 1 neurofibromatosis is an autosomal-dominant disorder with a nearly even split between spontaneous and inherited mutations. It is characterized by neurofibromas, which are complex tumors composed of axonal processes, Schwann cells, fibroblasts, perineural cells, and mast cells. The NF1 gene (neurofibromin 1), discovered in 1990,3 is located on chromosome 17q11.2 and encodes for the protein neurofibromin. This large gene (60 exons and >300 kilobases of genomic DNA) has one of the highest rates of spontaneous mutations in the entire human genome.4,5 Mutations exhibited by the gene are complete deletions, insertions, and nonsense and splicing mutations. Ultimately, these mutations may result in a loss of heterozygosity of the NF1 gene (a somatic loss of the second NF1 allele). Segmental, generalized, or gonadal forms of NF1 demonstrate mosaicism.6

Pathogenesis

Neurofibromin, the NF1 gene product, is a tumor suppressor expressed in many cells, primarily in neurons, glial cells, and Schwann cells, and is seen early in melanocyte development.7 The MAPK/ERK signaling pathway is a complex series of signals and interactions involved in cell growth and proliferation.5 Under normal conditions, neurofibromin, an RAS GTPase–activating protein promotes the conversion of the active RAS-GTP bound form to an inactive RAS-GDP bound form, thereby suppressing cell growth8,9; however, other possible effects are being investigated.10 Mast cells have been implicated in contributing to inflammation in the plexiform neurofibroma microenvironment of NF1.11,12 In addition, haploinsufficiency of NF1 (NF1+/−) and c-kit signaling in the hematopoietic system have been implicated in tumor progression. Accumulation of additional mutations of multiple genes, including INK4A/ARF and the protein p53, may be responsible for malignant transformation. These revelations of molecular and cellular mechanisms involved with NF1 tumorigenesis have led to trials of targeted therapies including the mammalian target of rapamycin and tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib mesylate, which is demonstrating promising preclinical results for treatment of peripheral nerve sheath tumors.13,14

Diagnosis

Seven cardinal diagnostic criteria have been delineated for NF1, at least 2 of which must be met to diagnose an individual with the condition.15 These criteria include (1) six or more café au lait macules (5 mm in diameter in prepubertal patients, 15 mm in postpubertal patients); (2) axillary or inguinal freckles (>2 freckles); (3) two or more typical neurofibromas or 1 plexiform neurofibroma, (4) optic nerve glioma, (5) two or more iris hamartomas (Lisch nodules), often only identified through slit-lamp examination by an ophthalmologist; (6) sphenoid dysplasia or typical long bone abnormalities such as pseudoarthritis; and (7) first-degree relative with NF1. Diagnosis may be difficult in patients who exhibit some dermatologic features of interest but who do not fully meet the diagnostic criteria.

Skin manifestations of NF1 may present in restricted segments of the body. It has been reported that half of those with NF1 are the first in their family to have the disease.16 Children with 6 or more café au lait macules alone and no family history of neurofibromatosis should be followed up, as their chances of developing NF1 are high.17 Occasionally, Lisch nodules may be the only clinical feature. Type 1 neurofibromatosis mutation analysis may be used to confirm the diagnosis in uncertain cases as well as prenatal diagnosis. However, genetic testing is not routinely advocated, and expert consultation is advised before it is undertaken. Furthermore, biopsy of asymptomatic cutaneous neurofibromas should not be undertaken for diagnostic purposes in individuals with confirmed NF1.18

Hyperintense lesions on T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain (formerly known as unidentified bright objects) probably are caused by aberrant myelination or gliosis and are pathognomonic of NF1.19The presence of these lesions can assist in the diagnosis of NF1, but MRI under anesthesia is not warranted for this purpose in children, who may not be able to stay still during the test.20

Physicians should not only be able to identify the cardinal skin features of NF1 but also the less common cutaneous and extracutaneous findings, which may indicate the need for referral to a dermatologist and/or neurologist.1 Café au lait macules (CALMs) are among the salient features of NF1. Classically, these lesions are well demarcated with smooth, regular, “coast of California” borders (unlike irregular “coast of Maine” borders) and a homogeneous appearance. Although the resemblance to the color of coffee in milk has earned these lesions their name, their color can range from tan to dark brown. The presence of multiple CALMs is highly suggestive of NF1.21 The prevalence of CALMs in the general population has varied from 3% to 36% depending on the study groups selected, but the presence of multiple CALMs in the general population typically is less than 1%.22 Frequently, CALMs are the first sign of NF1, occurring in 99% of NF1 patients within the first year of life. Patients continue to develop lesions throughout childhood, but they often fade in adulthood.23

Freckling of the skin folds is the most common of the cardinal criteria for NF1. Other sites include under the neck and breasts, around the lips, and trunk. Their size ranges from 1 to 3 mm, distinguishing them from CALMs. Considered nearly pathognomonic, NF1 generally occurs in children aged 3 to 5 years in the axillae or groin.15,24

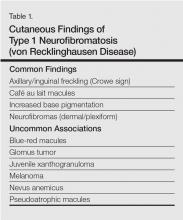

Cutaneous neurofibromas generally are cutaneous/dermal tumors that are dome shaped, soft, fleshy, and flesh colored to slightly hyperpigmented. Subcutaneous tumors are firm and nodular. Neurofibromas usually do not become apparent until puberty and may continue to increase in size and number throughout adulthood. Pregnancy also is associated with increased tumor growth.25 The tumors are comprised of Schwann cells, fibroblasts, mast cells, and perineural cells. There also is an admixture of collagen and extracellular matrix.26 The cutaneous and extracutaneous manifestations of NF1 are outlined in Table 1 and Table 2.27-31

Management

Type 1 neurofibromatosis needs to be differentiated from other conditions based on careful clinical examination. Additionally, histopathologic examination of the lesions, imaging studies (eg, MRI), echocardiography, regular skeletal roentgenogram, and detailed ophthalmologic examination are important to look for any visceral involvement. Painful and bleeding tumors and cosmetic enhancement warrant surgical intervention, including various surgical techniques and lasers.32,33 Application of sunscreen may make pigmentary alterations less noticeable over time. Although not often located on the face, CALMs also may be amenable to various makeup products. Various studies have demonstrated improvement of freckling and CALMs with topical vitamin D3 analogues and lovastatin (β-hydroxy-β-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitors)34-36; however, this needs further exploration. Rapamycin has demonstrated efficacy in reducing tumor volume in animal studies by inhibiting the mammalian target of rapamycin cellular pathway.37 Imatinib mesylate has demonstrated efficacy both in vivo and in vitro in mouse models by targeting the platelet-derived growth-factor receptors α and β.38

1. Boyd KP, Korf BR, Theos A. Neurofibromatosis type 1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1-14.

2. von Recklinghausen FV. Ueber die multiplen Fibrome der Haut und ihre Beziehung zu den Multiplen Neuromen. Berlin, Germany: August Hirschwald; 1882.

3. Viskochil D, Buchberg AM, Xu G, et al. Deletions and a translocation interrupt a cloned gene at the neurofibromatosis type 1 locus. Cell. 1990;62:187-192.

4. Theos A, Korf BR; American College of Physicians; American Physiological Society. Pathophysiology of neurofibromatosis type 1. Ann lntern Med. 2006;144:842-849.

5. Messiaen LM, Callens T, Mortier G, et al. Exhaustive mutation analysis of the NF1 gene allows identification of 95% of mutations and reveals a high frequency of unusual splicing defects. Hum Mutat. 2000;15:541-555.

6. Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

7. Stocker KM, Baizer L, Coston T, et al. Regulated expression of neurofibromin in migrating neural crest cells of avian embryos. J Neurobiol. 1995;27:535-552.

8. Maertens O, De Schepper S, Vandesompele J, et al. Molecular dissection of isolated disease features in mosaic neurofibromatosis type 1. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:243-251.

9. De Schepper S, Maertens O, Callens T, et al. Somatic mutation analysis in NF1 café au lait spots reveals two NF1 hits in the melanocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1050-1053.

10. Patrakitkomjorn S, Kobayahi D, Morikawa T, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) tumor suppressor, neurofibromin, regulates the neuronal differentiation of PC12 cells via its associating protein, CRMP-2 [published online ahead of print. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:9399-9413.

11. Yang FC, Ingram DA, Chen S, et al. Nf1-dependent tumors require a microenvironment containing Nf1+/− and c-kit-dependent bone marrow. Cell. 2008;135:437-448.

12. Yang FC, Chen S, Clegg T, et al. Nf1+/- mast cells induce neurofibroma like phenotypes through secreted TGF-β signaling. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2421-2437.

13. Gottfried ON, Viskochil DH, Couldwell WT. Neurofibromatosis type 1 and tumorigenesis: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;28:E8.

14. Le LQ, Parada LF. Tumor microenvironment and neurofibromatosis type I: connecting the GAPs. Oncogene. 2007;26:4609-4616.

15. Gutmann DH, Aylsworth A, Carey JC, et al. The diagnostic evaluation and multidisciplinary management of neurofibromatosis 1 and neurofibromatosis 2. JAMA. 1997;278:51-57.

16. Huson SM, Harper PS, Compston DA. Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. a clinical and population study in south-east Wales. Brain. 1988;111(pt 6):1355-1381.

17. Korf BR. Diagnostic outcome in children with multiple café au lait spots. Pediatrics. 1992;90:924-927.

18. Ferner RE, Huson SM, Thomas N, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of individuals with neurofibromatosis 1. J Med Genet. 2007;44:81-88.

19. DiPaolo DP, Zimmerman RA, Rorke LB, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 1: pathologic substrate of high-signal-intensity foci in the brain. Radiology. 1995;195:721-724.

20. DeBella K, Poskitt K, Szudek J, et al. Use of “unidentified bright objects” on MRI for diagnosis of neurofibromatosis 1 in children. Neurology. 2000;54:1646-1651.

21. Whitehouse D. Diagnostic value of the café-au-lait spot in children. Arch Dis Child. 1966;41:316-319.

22. Landau M, Krafchik BR. The diagnostic value of café-au-lait macules. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(6, pt 1):877-890.

23. DeBella K, Szudek J, Friedman JM. Use of the National Institutes of Health criteria for diagnosis of neurofibromatosis 1 in children. Pediatrics. 2000;105(3, pt 1):608-614.

24. Obringer AC, Meadows AT, Zackai EH. The diagnosis of neurofibromatosis-l in the child under the age of 6 years. Am J Dis Child. 1989;143:717-719.

25. Page PZ, Page GP, Ecosse E, et al. Impact of neurofibromatosis 1 on quality of life: a cross-sectional study of 176 American cases. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:1893-1898.

26. Maertens O, Brems H. Vandesompele J, et al. Comprehensive NF1 screening on cultured Schwann cells from neurofibromas. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:1030-1040.

27. Huson S, Jones D, Beck L. Ophthalmic manifestations of neurofibromatosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1987;71:235-238.

28. Listernick R, Ferner RE, Liu GT, et al. Optic pathway gliomas in neurofibromatosis-1: controversies and recommendations. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:189-198.

29. Levine TM, Materek A, Abel J, et al. Cognitive profile of neurofibromatosis type 1. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2006;13:8-20.

30. Lammert M, Kappler M, Mautner VF, et al. Decreased bone mineral density in patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:1161-1166.

31. Schindeler A, Little DG. Recent insights into bone development, homeostasis, and repair in type 1 neurofibromatosis (NFl). Bone. 2008;42:616-622.

32. Yoo KH, Kim BJ, Rho YK, et al. A case of diffuse neurofibroma of the scalp. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:46-48.

33. Onesti MG, Carella S, Spinelli G, et al. A study of 17 patients affected with plexiform neurofibromas in upper and lower extremities: comparison between different surgical techniques. Acta Chir Plast. 2009;51:35-40.

34. Yoshida Y, Sato N, Furumura M, et al. Treatment of pigmented lesions of neurofibromatosis 1 with intense pulsed-radio frequency in combination with topical application of vitamin D3 ointment. J Dermatol. 2007;34:227-230.

35. Nakayama J, Kiryu H, Urabe K, et al. Vitamin D3 analogues improve café au lait spots in patients with von Recklinghausen’s disease: experimental and clinical studies. Eur J Dermatol. 1999;9:202-206.

36. Lammert M, Friedman JM, Roth HJ, et al. Vitamin D deficiency associated with number of neurofibromas in neurofibromatosis 1. J Med Genet. 2006;43:810-813.

37. Hegedus B, Banerjee D, Yeh TH, et al. Preclinical cancer therapy in a mouse model of neurofibromatosis-1 optic glioma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1520-1528.

38. Demestre M, Herzberg J, Holtkamp N, et al. Imatinib mesylate (Glivec) inhibits Schwann cell viability and reduces the size of human plexiform neurofibroma in a xenograft model. J Neurooncol. 2010;98:11-19.

Type 1 neurofibromatosis (NF1), or von Recklinghausen disease, is a multisystem disorder affecting approximately 1 in 3500 people in South East Wales.1 Type 1 neurofibromatosis has been described in the literature since the 13th century but was not recognized as a distinct disorder until 1882 in Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen’s landmark publication “On Multiple Fibromas of the Skin and Their Relationship to Multiple Neuromas.”2

Genetics

Type 1 neurofibromatosis is an autosomal-dominant disorder with a nearly even split between spontaneous and inherited mutations. It is characterized by neurofibromas, which are complex tumors composed of axonal processes, Schwann cells, fibroblasts, perineural cells, and mast cells. The NF1 gene (neurofibromin 1), discovered in 1990,3 is located on chromosome 17q11.2 and encodes for the protein neurofibromin. This large gene (60 exons and >300 kilobases of genomic DNA) has one of the highest rates of spontaneous mutations in the entire human genome.4,5 Mutations exhibited by the gene are complete deletions, insertions, and nonsense and splicing mutations. Ultimately, these mutations may result in a loss of heterozygosity of the NF1 gene (a somatic loss of the second NF1 allele). Segmental, generalized, or gonadal forms of NF1 demonstrate mosaicism.6

Pathogenesis

Neurofibromin, the NF1 gene product, is a tumor suppressor expressed in many cells, primarily in neurons, glial cells, and Schwann cells, and is seen early in melanocyte development.7 The MAPK/ERK signaling pathway is a complex series of signals and interactions involved in cell growth and proliferation.5 Under normal conditions, neurofibromin, an RAS GTPase–activating protein promotes the conversion of the active RAS-GTP bound form to an inactive RAS-GDP bound form, thereby suppressing cell growth8,9; however, other possible effects are being investigated.10 Mast cells have been implicated in contributing to inflammation in the plexiform neurofibroma microenvironment of NF1.11,12 In addition, haploinsufficiency of NF1 (NF1+/−) and c-kit signaling in the hematopoietic system have been implicated in tumor progression. Accumulation of additional mutations of multiple genes, including INK4A/ARF and the protein p53, may be responsible for malignant transformation. These revelations of molecular and cellular mechanisms involved with NF1 tumorigenesis have led to trials of targeted therapies including the mammalian target of rapamycin and tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib mesylate, which is demonstrating promising preclinical results for treatment of peripheral nerve sheath tumors.13,14

Diagnosis

Seven cardinal diagnostic criteria have been delineated for NF1, at least 2 of which must be met to diagnose an individual with the condition.15 These criteria include (1) six or more café au lait macules (5 mm in diameter in prepubertal patients, 15 mm in postpubertal patients); (2) axillary or inguinal freckles (>2 freckles); (3) two or more typical neurofibromas or 1 plexiform neurofibroma, (4) optic nerve glioma, (5) two or more iris hamartomas (Lisch nodules), often only identified through slit-lamp examination by an ophthalmologist; (6) sphenoid dysplasia or typical long bone abnormalities such as pseudoarthritis; and (7) first-degree relative with NF1. Diagnosis may be difficult in patients who exhibit some dermatologic features of interest but who do not fully meet the diagnostic criteria.

Skin manifestations of NF1 may present in restricted segments of the body. It has been reported that half of those with NF1 are the first in their family to have the disease.16 Children with 6 or more café au lait macules alone and no family history of neurofibromatosis should be followed up, as their chances of developing NF1 are high.17 Occasionally, Lisch nodules may be the only clinical feature. Type 1 neurofibromatosis mutation analysis may be used to confirm the diagnosis in uncertain cases as well as prenatal diagnosis. However, genetic testing is not routinely advocated, and expert consultation is advised before it is undertaken. Furthermore, biopsy of asymptomatic cutaneous neurofibromas should not be undertaken for diagnostic purposes in individuals with confirmed NF1.18

Hyperintense lesions on T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain (formerly known as unidentified bright objects) probably are caused by aberrant myelination or gliosis and are pathognomonic of NF1.19The presence of these lesions can assist in the diagnosis of NF1, but MRI under anesthesia is not warranted for this purpose in children, who may not be able to stay still during the test.20

Physicians should not only be able to identify the cardinal skin features of NF1 but also the less common cutaneous and extracutaneous findings, which may indicate the need for referral to a dermatologist and/or neurologist.1 Café au lait macules (CALMs) are among the salient features of NF1. Classically, these lesions are well demarcated with smooth, regular, “coast of California” borders (unlike irregular “coast of Maine” borders) and a homogeneous appearance. Although the resemblance to the color of coffee in milk has earned these lesions their name, their color can range from tan to dark brown. The presence of multiple CALMs is highly suggestive of NF1.21 The prevalence of CALMs in the general population has varied from 3% to 36% depending on the study groups selected, but the presence of multiple CALMs in the general population typically is less than 1%.22 Frequently, CALMs are the first sign of NF1, occurring in 99% of NF1 patients within the first year of life. Patients continue to develop lesions throughout childhood, but they often fade in adulthood.23

Freckling of the skin folds is the most common of the cardinal criteria for NF1. Other sites include under the neck and breasts, around the lips, and trunk. Their size ranges from 1 to 3 mm, distinguishing them from CALMs. Considered nearly pathognomonic, NF1 generally occurs in children aged 3 to 5 years in the axillae or groin.15,24

Cutaneous neurofibromas generally are cutaneous/dermal tumors that are dome shaped, soft, fleshy, and flesh colored to slightly hyperpigmented. Subcutaneous tumors are firm and nodular. Neurofibromas usually do not become apparent until puberty and may continue to increase in size and number throughout adulthood. Pregnancy also is associated with increased tumor growth.25 The tumors are comprised of Schwann cells, fibroblasts, mast cells, and perineural cells. There also is an admixture of collagen and extracellular matrix.26 The cutaneous and extracutaneous manifestations of NF1 are outlined in Table 1 and Table 2.27-31

Management

Type 1 neurofibromatosis needs to be differentiated from other conditions based on careful clinical examination. Additionally, histopathologic examination of the lesions, imaging studies (eg, MRI), echocardiography, regular skeletal roentgenogram, and detailed ophthalmologic examination are important to look for any visceral involvement. Painful and bleeding tumors and cosmetic enhancement warrant surgical intervention, including various surgical techniques and lasers.32,33 Application of sunscreen may make pigmentary alterations less noticeable over time. Although not often located on the face, CALMs also may be amenable to various makeup products. Various studies have demonstrated improvement of freckling and CALMs with topical vitamin D3 analogues and lovastatin (β-hydroxy-β-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitors)34-36; however, this needs further exploration. Rapamycin has demonstrated efficacy in reducing tumor volume in animal studies by inhibiting the mammalian target of rapamycin cellular pathway.37 Imatinib mesylate has demonstrated efficacy both in vivo and in vitro in mouse models by targeting the platelet-derived growth-factor receptors α and β.38

Type 1 neurofibromatosis (NF1), or von Recklinghausen disease, is a multisystem disorder affecting approximately 1 in 3500 people in South East Wales.1 Type 1 neurofibromatosis has been described in the literature since the 13th century but was not recognized as a distinct disorder until 1882 in Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen’s landmark publication “On Multiple Fibromas of the Skin and Their Relationship to Multiple Neuromas.”2

Genetics

Type 1 neurofibromatosis is an autosomal-dominant disorder with a nearly even split between spontaneous and inherited mutations. It is characterized by neurofibromas, which are complex tumors composed of axonal processes, Schwann cells, fibroblasts, perineural cells, and mast cells. The NF1 gene (neurofibromin 1), discovered in 1990,3 is located on chromosome 17q11.2 and encodes for the protein neurofibromin. This large gene (60 exons and >300 kilobases of genomic DNA) has one of the highest rates of spontaneous mutations in the entire human genome.4,5 Mutations exhibited by the gene are complete deletions, insertions, and nonsense and splicing mutations. Ultimately, these mutations may result in a loss of heterozygosity of the NF1 gene (a somatic loss of the second NF1 allele). Segmental, generalized, or gonadal forms of NF1 demonstrate mosaicism.6

Pathogenesis

Neurofibromin, the NF1 gene product, is a tumor suppressor expressed in many cells, primarily in neurons, glial cells, and Schwann cells, and is seen early in melanocyte development.7 The MAPK/ERK signaling pathway is a complex series of signals and interactions involved in cell growth and proliferation.5 Under normal conditions, neurofibromin, an RAS GTPase–activating protein promotes the conversion of the active RAS-GTP bound form to an inactive RAS-GDP bound form, thereby suppressing cell growth8,9; however, other possible effects are being investigated.10 Mast cells have been implicated in contributing to inflammation in the plexiform neurofibroma microenvironment of NF1.11,12 In addition, haploinsufficiency of NF1 (NF1+/−) and c-kit signaling in the hematopoietic system have been implicated in tumor progression. Accumulation of additional mutations of multiple genes, including INK4A/ARF and the protein p53, may be responsible for malignant transformation. These revelations of molecular and cellular mechanisms involved with NF1 tumorigenesis have led to trials of targeted therapies including the mammalian target of rapamycin and tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib mesylate, which is demonstrating promising preclinical results for treatment of peripheral nerve sheath tumors.13,14

Diagnosis

Seven cardinal diagnostic criteria have been delineated for NF1, at least 2 of which must be met to diagnose an individual with the condition.15 These criteria include (1) six or more café au lait macules (5 mm in diameter in prepubertal patients, 15 mm in postpubertal patients); (2) axillary or inguinal freckles (>2 freckles); (3) two or more typical neurofibromas or 1 plexiform neurofibroma, (4) optic nerve glioma, (5) two or more iris hamartomas (Lisch nodules), often only identified through slit-lamp examination by an ophthalmologist; (6) sphenoid dysplasia or typical long bone abnormalities such as pseudoarthritis; and (7) first-degree relative with NF1. Diagnosis may be difficult in patients who exhibit some dermatologic features of interest but who do not fully meet the diagnostic criteria.

Skin manifestations of NF1 may present in restricted segments of the body. It has been reported that half of those with NF1 are the first in their family to have the disease.16 Children with 6 or more café au lait macules alone and no family history of neurofibromatosis should be followed up, as their chances of developing NF1 are high.17 Occasionally, Lisch nodules may be the only clinical feature. Type 1 neurofibromatosis mutation analysis may be used to confirm the diagnosis in uncertain cases as well as prenatal diagnosis. However, genetic testing is not routinely advocated, and expert consultation is advised before it is undertaken. Furthermore, biopsy of asymptomatic cutaneous neurofibromas should not be undertaken for diagnostic purposes in individuals with confirmed NF1.18

Hyperintense lesions on T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain (formerly known as unidentified bright objects) probably are caused by aberrant myelination or gliosis and are pathognomonic of NF1.19The presence of these lesions can assist in the diagnosis of NF1, but MRI under anesthesia is not warranted for this purpose in children, who may not be able to stay still during the test.20

Physicians should not only be able to identify the cardinal skin features of NF1 but also the less common cutaneous and extracutaneous findings, which may indicate the need for referral to a dermatologist and/or neurologist.1 Café au lait macules (CALMs) are among the salient features of NF1. Classically, these lesions are well demarcated with smooth, regular, “coast of California” borders (unlike irregular “coast of Maine” borders) and a homogeneous appearance. Although the resemblance to the color of coffee in milk has earned these lesions their name, their color can range from tan to dark brown. The presence of multiple CALMs is highly suggestive of NF1.21 The prevalence of CALMs in the general population has varied from 3% to 36% depending on the study groups selected, but the presence of multiple CALMs in the general population typically is less than 1%.22 Frequently, CALMs are the first sign of NF1, occurring in 99% of NF1 patients within the first year of life. Patients continue to develop lesions throughout childhood, but they often fade in adulthood.23

Freckling of the skin folds is the most common of the cardinal criteria for NF1. Other sites include under the neck and breasts, around the lips, and trunk. Their size ranges from 1 to 3 mm, distinguishing them from CALMs. Considered nearly pathognomonic, NF1 generally occurs in children aged 3 to 5 years in the axillae or groin.15,24

Cutaneous neurofibromas generally are cutaneous/dermal tumors that are dome shaped, soft, fleshy, and flesh colored to slightly hyperpigmented. Subcutaneous tumors are firm and nodular. Neurofibromas usually do not become apparent until puberty and may continue to increase in size and number throughout adulthood. Pregnancy also is associated with increased tumor growth.25 The tumors are comprised of Schwann cells, fibroblasts, mast cells, and perineural cells. There also is an admixture of collagen and extracellular matrix.26 The cutaneous and extracutaneous manifestations of NF1 are outlined in Table 1 and Table 2.27-31

Management

Type 1 neurofibromatosis needs to be differentiated from other conditions based on careful clinical examination. Additionally, histopathologic examination of the lesions, imaging studies (eg, MRI), echocardiography, regular skeletal roentgenogram, and detailed ophthalmologic examination are important to look for any visceral involvement. Painful and bleeding tumors and cosmetic enhancement warrant surgical intervention, including various surgical techniques and lasers.32,33 Application of sunscreen may make pigmentary alterations less noticeable over time. Although not often located on the face, CALMs also may be amenable to various makeup products. Various studies have demonstrated improvement of freckling and CALMs with topical vitamin D3 analogues and lovastatin (β-hydroxy-β-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitors)34-36; however, this needs further exploration. Rapamycin has demonstrated efficacy in reducing tumor volume in animal studies by inhibiting the mammalian target of rapamycin cellular pathway.37 Imatinib mesylate has demonstrated efficacy both in vivo and in vitro in mouse models by targeting the platelet-derived growth-factor receptors α and β.38

1. Boyd KP, Korf BR, Theos A. Neurofibromatosis type 1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1-14.

2. von Recklinghausen FV. Ueber die multiplen Fibrome der Haut und ihre Beziehung zu den Multiplen Neuromen. Berlin, Germany: August Hirschwald; 1882.

3. Viskochil D, Buchberg AM, Xu G, et al. Deletions and a translocation interrupt a cloned gene at the neurofibromatosis type 1 locus. Cell. 1990;62:187-192.

4. Theos A, Korf BR; American College of Physicians; American Physiological Society. Pathophysiology of neurofibromatosis type 1. Ann lntern Med. 2006;144:842-849.

5. Messiaen LM, Callens T, Mortier G, et al. Exhaustive mutation analysis of the NF1 gene allows identification of 95% of mutations and reveals a high frequency of unusual splicing defects. Hum Mutat. 2000;15:541-555.

6. Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

7. Stocker KM, Baizer L, Coston T, et al. Regulated expression of neurofibromin in migrating neural crest cells of avian embryos. J Neurobiol. 1995;27:535-552.

8. Maertens O, De Schepper S, Vandesompele J, et al. Molecular dissection of isolated disease features in mosaic neurofibromatosis type 1. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:243-251.

9. De Schepper S, Maertens O, Callens T, et al. Somatic mutation analysis in NF1 café au lait spots reveals two NF1 hits in the melanocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1050-1053.

10. Patrakitkomjorn S, Kobayahi D, Morikawa T, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) tumor suppressor, neurofibromin, regulates the neuronal differentiation of PC12 cells via its associating protein, CRMP-2 [published online ahead of print. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:9399-9413.

11. Yang FC, Ingram DA, Chen S, et al. Nf1-dependent tumors require a microenvironment containing Nf1+/− and c-kit-dependent bone marrow. Cell. 2008;135:437-448.

12. Yang FC, Chen S, Clegg T, et al. Nf1+/- mast cells induce neurofibroma like phenotypes through secreted TGF-β signaling. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2421-2437.

13. Gottfried ON, Viskochil DH, Couldwell WT. Neurofibromatosis type 1 and tumorigenesis: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;28:E8.

14. Le LQ, Parada LF. Tumor microenvironment and neurofibromatosis type I: connecting the GAPs. Oncogene. 2007;26:4609-4616.

15. Gutmann DH, Aylsworth A, Carey JC, et al. The diagnostic evaluation and multidisciplinary management of neurofibromatosis 1 and neurofibromatosis 2. JAMA. 1997;278:51-57.

16. Huson SM, Harper PS, Compston DA. Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. a clinical and population study in south-east Wales. Brain. 1988;111(pt 6):1355-1381.

17. Korf BR. Diagnostic outcome in children with multiple café au lait spots. Pediatrics. 1992;90:924-927.

18. Ferner RE, Huson SM, Thomas N, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of individuals with neurofibromatosis 1. J Med Genet. 2007;44:81-88.

19. DiPaolo DP, Zimmerman RA, Rorke LB, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 1: pathologic substrate of high-signal-intensity foci in the brain. Radiology. 1995;195:721-724.

20. DeBella K, Poskitt K, Szudek J, et al. Use of “unidentified bright objects” on MRI for diagnosis of neurofibromatosis 1 in children. Neurology. 2000;54:1646-1651.

21. Whitehouse D. Diagnostic value of the café-au-lait spot in children. Arch Dis Child. 1966;41:316-319.

22. Landau M, Krafchik BR. The diagnostic value of café-au-lait macules. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(6, pt 1):877-890.

23. DeBella K, Szudek J, Friedman JM. Use of the National Institutes of Health criteria for diagnosis of neurofibromatosis 1 in children. Pediatrics. 2000;105(3, pt 1):608-614.

24. Obringer AC, Meadows AT, Zackai EH. The diagnosis of neurofibromatosis-l in the child under the age of 6 years. Am J Dis Child. 1989;143:717-719.

25. Page PZ, Page GP, Ecosse E, et al. Impact of neurofibromatosis 1 on quality of life: a cross-sectional study of 176 American cases. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:1893-1898.

26. Maertens O, Brems H. Vandesompele J, et al. Comprehensive NF1 screening on cultured Schwann cells from neurofibromas. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:1030-1040.

27. Huson S, Jones D, Beck L. Ophthalmic manifestations of neurofibromatosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1987;71:235-238.

28. Listernick R, Ferner RE, Liu GT, et al. Optic pathway gliomas in neurofibromatosis-1: controversies and recommendations. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:189-198.

29. Levine TM, Materek A, Abel J, et al. Cognitive profile of neurofibromatosis type 1. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2006;13:8-20.

30. Lammert M, Kappler M, Mautner VF, et al. Decreased bone mineral density in patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:1161-1166.

31. Schindeler A, Little DG. Recent insights into bone development, homeostasis, and repair in type 1 neurofibromatosis (NFl). Bone. 2008;42:616-622.

32. Yoo KH, Kim BJ, Rho YK, et al. A case of diffuse neurofibroma of the scalp. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:46-48.

33. Onesti MG, Carella S, Spinelli G, et al. A study of 17 patients affected with plexiform neurofibromas in upper and lower extremities: comparison between different surgical techniques. Acta Chir Plast. 2009;51:35-40.

34. Yoshida Y, Sato N, Furumura M, et al. Treatment of pigmented lesions of neurofibromatosis 1 with intense pulsed-radio frequency in combination with topical application of vitamin D3 ointment. J Dermatol. 2007;34:227-230.

35. Nakayama J, Kiryu H, Urabe K, et al. Vitamin D3 analogues improve café au lait spots in patients with von Recklinghausen’s disease: experimental and clinical studies. Eur J Dermatol. 1999;9:202-206.

36. Lammert M, Friedman JM, Roth HJ, et al. Vitamin D deficiency associated with number of neurofibromas in neurofibromatosis 1. J Med Genet. 2006;43:810-813.

37. Hegedus B, Banerjee D, Yeh TH, et al. Preclinical cancer therapy in a mouse model of neurofibromatosis-1 optic glioma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1520-1528.

38. Demestre M, Herzberg J, Holtkamp N, et al. Imatinib mesylate (Glivec) inhibits Schwann cell viability and reduces the size of human plexiform neurofibroma in a xenograft model. J Neurooncol. 2010;98:11-19.

1. Boyd KP, Korf BR, Theos A. Neurofibromatosis type 1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1-14.

2. von Recklinghausen FV. Ueber die multiplen Fibrome der Haut und ihre Beziehung zu den Multiplen Neuromen. Berlin, Germany: August Hirschwald; 1882.

3. Viskochil D, Buchberg AM, Xu G, et al. Deletions and a translocation interrupt a cloned gene at the neurofibromatosis type 1 locus. Cell. 1990;62:187-192.

4. Theos A, Korf BR; American College of Physicians; American Physiological Society. Pathophysiology of neurofibromatosis type 1. Ann lntern Med. 2006;144:842-849.

5. Messiaen LM, Callens T, Mortier G, et al. Exhaustive mutation analysis of the NF1 gene allows identification of 95% of mutations and reveals a high frequency of unusual splicing defects. Hum Mutat. 2000;15:541-555.

6. Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

7. Stocker KM, Baizer L, Coston T, et al. Regulated expression of neurofibromin in migrating neural crest cells of avian embryos. J Neurobiol. 1995;27:535-552.

8. Maertens O, De Schepper S, Vandesompele J, et al. Molecular dissection of isolated disease features in mosaic neurofibromatosis type 1. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:243-251.

9. De Schepper S, Maertens O, Callens T, et al. Somatic mutation analysis in NF1 café au lait spots reveals two NF1 hits in the melanocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1050-1053.

10. Patrakitkomjorn S, Kobayahi D, Morikawa T, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) tumor suppressor, neurofibromin, regulates the neuronal differentiation of PC12 cells via its associating protein, CRMP-2 [published online ahead of print. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:9399-9413.

11. Yang FC, Ingram DA, Chen S, et al. Nf1-dependent tumors require a microenvironment containing Nf1+/− and c-kit-dependent bone marrow. Cell. 2008;135:437-448.

12. Yang FC, Chen S, Clegg T, et al. Nf1+/- mast cells induce neurofibroma like phenotypes through secreted TGF-β signaling. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2421-2437.

13. Gottfried ON, Viskochil DH, Couldwell WT. Neurofibromatosis type 1 and tumorigenesis: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;28:E8.

14. Le LQ, Parada LF. Tumor microenvironment and neurofibromatosis type I: connecting the GAPs. Oncogene. 2007;26:4609-4616.

15. Gutmann DH, Aylsworth A, Carey JC, et al. The diagnostic evaluation and multidisciplinary management of neurofibromatosis 1 and neurofibromatosis 2. JAMA. 1997;278:51-57.

16. Huson SM, Harper PS, Compston DA. Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. a clinical and population study in south-east Wales. Brain. 1988;111(pt 6):1355-1381.

17. Korf BR. Diagnostic outcome in children with multiple café au lait spots. Pediatrics. 1992;90:924-927.

18. Ferner RE, Huson SM, Thomas N, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of individuals with neurofibromatosis 1. J Med Genet. 2007;44:81-88.

19. DiPaolo DP, Zimmerman RA, Rorke LB, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 1: pathologic substrate of high-signal-intensity foci in the brain. Radiology. 1995;195:721-724.

20. DeBella K, Poskitt K, Szudek J, et al. Use of “unidentified bright objects” on MRI for diagnosis of neurofibromatosis 1 in children. Neurology. 2000;54:1646-1651.

21. Whitehouse D. Diagnostic value of the café-au-lait spot in children. Arch Dis Child. 1966;41:316-319.

22. Landau M, Krafchik BR. The diagnostic value of café-au-lait macules. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(6, pt 1):877-890.

23. DeBella K, Szudek J, Friedman JM. Use of the National Institutes of Health criteria for diagnosis of neurofibromatosis 1 in children. Pediatrics. 2000;105(3, pt 1):608-614.

24. Obringer AC, Meadows AT, Zackai EH. The diagnosis of neurofibromatosis-l in the child under the age of 6 years. Am J Dis Child. 1989;143:717-719.

25. Page PZ, Page GP, Ecosse E, et al. Impact of neurofibromatosis 1 on quality of life: a cross-sectional study of 176 American cases. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:1893-1898.

26. Maertens O, Brems H. Vandesompele J, et al. Comprehensive NF1 screening on cultured Schwann cells from neurofibromas. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:1030-1040.

27. Huson S, Jones D, Beck L. Ophthalmic manifestations of neurofibromatosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1987;71:235-238.

28. Listernick R, Ferner RE, Liu GT, et al. Optic pathway gliomas in neurofibromatosis-1: controversies and recommendations. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:189-198.

29. Levine TM, Materek A, Abel J, et al. Cognitive profile of neurofibromatosis type 1. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2006;13:8-20.

30. Lammert M, Kappler M, Mautner VF, et al. Decreased bone mineral density in patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:1161-1166.

31. Schindeler A, Little DG. Recent insights into bone development, homeostasis, and repair in type 1 neurofibromatosis (NFl). Bone. 2008;42:616-622.

32. Yoo KH, Kim BJ, Rho YK, et al. A case of diffuse neurofibroma of the scalp. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:46-48.

33. Onesti MG, Carella S, Spinelli G, et al. A study of 17 patients affected with plexiform neurofibromas in upper and lower extremities: comparison between different surgical techniques. Acta Chir Plast. 2009;51:35-40.

34. Yoshida Y, Sato N, Furumura M, et al. Treatment of pigmented lesions of neurofibromatosis 1 with intense pulsed-radio frequency in combination with topical application of vitamin D3 ointment. J Dermatol. 2007;34:227-230.

35. Nakayama J, Kiryu H, Urabe K, et al. Vitamin D3 analogues improve café au lait spots in patients with von Recklinghausen’s disease: experimental and clinical studies. Eur J Dermatol. 1999;9:202-206.

36. Lammert M, Friedman JM, Roth HJ, et al. Vitamin D deficiency associated with number of neurofibromas in neurofibromatosis 1. J Med Genet. 2006;43:810-813.

37. Hegedus B, Banerjee D, Yeh TH, et al. Preclinical cancer therapy in a mouse model of neurofibromatosis-1 optic glioma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1520-1528.

38. Demestre M, Herzberg J, Holtkamp N, et al. Imatinib mesylate (Glivec) inhibits Schwann cell viability and reduces the size of human plexiform neurofibroma in a xenograft model. J Neurooncol. 2010;98:11-19.

Practice Points

- Histopathology and magnetic resonance imaging are useful in diagnosing type 1 neurofibromatosis (NF1).

- Newer treatments like statins and tyrosine kinase inhibitors are worth exploring in NF1.