User login

CASE Concerning finding on repeat CD

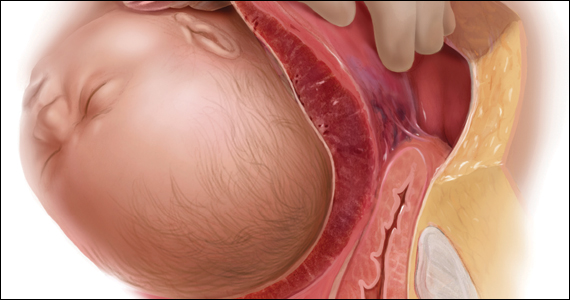

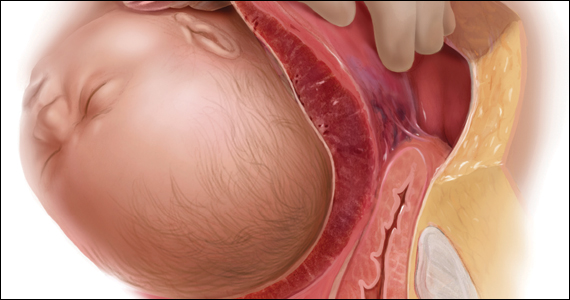

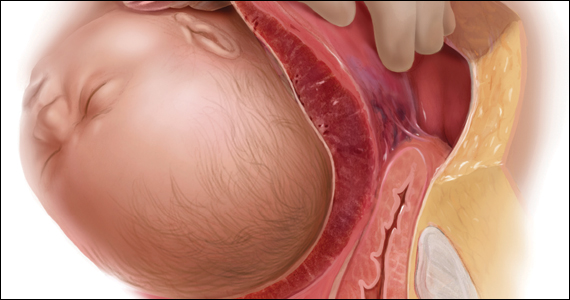

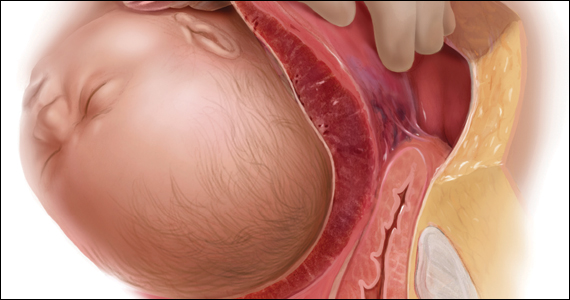

A 30-year-old woman with a history of 1 prior cesarean delivery (CD) presents to labor and delivery at 38 weeks of gestation with symptoms of mild cramping. Her prenatal care was uncomplicated. The covering team made a decision to proceed with a repeat CD. A Pfannenstiel incision is made to enter the abdomen, and inspection of the lower uterine segment is concerning for a placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) (FIGURE).

What would be your next steps?

Placenta accreta spectrum describes the range of disorders of placental implantation, including placenta accreta, increta, and percreta. PAS is a significant cause of severe maternal morbidity and mortality, primarily due to massive hemorrhage at the time of delivery. The incidence of PAS continues to rise along with the CD rate. The authors of a recent meta-analysis reported a pooled prevalence rate of 1 in 588 women.1 Notably, in women with PAS, the rate of hysterectomy is 52.2%, and the transfusion-dependent hemorrhage rate is 46.9%.1

Ideally, PAS should be diagnosed or at least suspected antenatally during prenatal ultrasonography, leading to delivery planning by a multidisciplinary team.2 The presence of a multidisciplinary team—in addition to the primary obstetric and surgical teams—composed of experienced anesthesiologists, a blood bank able to respond to massive transfusion needs, critical care specialists, and interventional radiologists is associated with improved outcomes.3-5

Occasionally, a patient is found to have an advanced PAS (increta or percreta) at the time of delivery. In these situations, it is paramount that the appropriate resources be assembled as expeditiously as possible to optimize maternal outcomes. Surgical management can be challenging even for experienced pelvic surgeons, and appropriate resuscitation cannot be provided by a single anesthesiologist working alone. A cavalier attitude of proceeding with the delivery “as usual” in the face of an unexpected PAS situation can lead to disastrous consequences, including maternal death.

In this article, we review the important steps to take when faced with the unexpected situation of a PAS at the time of CD.

Continue to: Stop and collect your multidisciplinary team...

Stop and collect your multidisciplinary team

Once the diagnosis of an advanced PAS is suspected, the first step is to stop and request the presence of your institution’s multidisciplinary surgical team. This team typically includes a maternal-fetal specialist or, if not available, an experienced obstetrician, and an expert pelvic surgeon, which varies by institution (gynecologic oncologist, trauma surgeon, urologist, urogynecologist, vascular surgeon). An interventional radiology team is an additional useful resource that can assist with the control of pelvic hemorrhage using embolization techniques.

In our opinion, it is not appropriate to have a surgical backup team available only as needed at a certain distance from the hospital or even in the building. Because of the acuity and magnitude of bleeding that can occur in a short time, the most appropriate approach is to have your surgical team scrubbed and ready to assist or take over the procedure immediately if indicated.

Additional support staff also may be required. A single circulating nurse may not be sufficient, and available nursing staff may need to be called. The surgical technician scrubbed on the case may be familiar only with uncomplicated CDs and can be overwhelmed during a PAS case. Having a more experienced surgical technologist can optimize the availability of the appropriate instruments for the surgical team.

If a multidisciplinary surgical team with PAS management expertise is not available at your institution and the patient is stable, it is appropriate to consider transferring her to the nearest center that can meet the high-risk needs of this situation.6

Prepare for resuscitation

While you are calling your multidisciplinary team members, implement plans for resuscitation by notifying the anesthesiologist about the PAS findings. This will allow the gathering of needed resources that may include calling on additional anesthesiologists with experience in high-risk obstetrics, trauma, or critical care.

Placing large-bore intravenous lines or a central line to allow rapid transfusion is essential. Strongly consider inserting an arterial line for hemodynamic monitoring and intraoperative blood draws to monitor blood loss, blood gases, electrolytes, and coagulation parameters, which can guide resuscitative efforts and replacement therapies.

Simultaneously, inform the blood bank to prepare blood and blood products for possible activation of a massive transfusion protocol. It is imperative to have the products available in the operating room (OR) prior to proceeding with the surgery. Our current practice is to have 10 units of packed red blood cells and fresh frozen plasma available in the OR for all our prenatally diagnosed electively planned PAS cases.

Optimize exposure of the surgical field

Appropriate exposure of the surgical field is essential and should include exposure of the uterine fundus and the pelvic sidewalls. The uterine incision should avoid the placenta; typically it is placed at the level of the uterine fundus. Exposure of the pelvic sidewalls is needed to open the retroperitoneum and identify the ureter and the iliac vessels.

Vertical extension of the fascial incision probably will be needed to achieve appropriate exposure. Although at times this can be done without a concomitant vertical skin incision, often an inverted T incision is required. Be mindful that PAS is a life-threatening condition and that aesthetics are not a priority. After extending the fascial incision, adequate exposure can be achieved with any of the commonly used retractors or wound protectors (depending on institutional availability and surgeon preference) or by the surgical assistants using body wall retractors.

We routinely place the patient in lithotomy position. This allows us to monitor for vaginal bleeding (often a site of unrecognized massive hemorrhage) during the surgery, facilitate retrograde bladder filling, and provide a vaginal access to the pelvis. In addition, the lithotomy position allows for cystoscopy and placement of ureteral stents, which can be performed before starting the surgery to help prevent urinary tract injuries or at the end of the procedure in case one is suspected.7

Continue to: Performing the hysterectomy...

Performing the hysterectomy

A complete review of all surgical techniques for managing PAS is beyond the scope of this article. However, we briefly cover important procedural steps and offer suggestions on how to minimize the risk of bleeding.

In our experience. The areas with the highest risk of massive bleeding that can be difficult to control include the pelvic sidewall when there is lateral extension of the PAS, the vesicouterine space, and placenta previa vaginally. Be mindful of these areas at risk and have a plan in place in case of bleeding.

Uterine incision

Avoid the placenta when making the uterine incision, which is typically done in the fundal part of the uterus. Cut and tie the cord and return it to the uterine cavity. Close the incision in a single layer. Use of a surgical stapler can be used for the hysterotomy and can decrease the amount of blood loss.8

Superior attachments of the uterus

The superior attachments of the uterus include the round ligament, the utero-ovarian ligament, and the fallopian tubes. With meticulous dissection, develop an avascular space underneath these structures and, in turn, individually divide and suture ligate; this is typically achieved with minimal blood loss.

In addition, isolate the engorged veins of the broad ligament and divide them in a similar fashion.

In our experience. Use of a vessel-sealing device can facilitate division of all the former structures. Simply excise the fallopian tubes with the vessel-sealing device either at this time or after the uterus is removed.

Pelvic sidewall

Once the superior attachments of the uterus have been divided, the next step involves exposing the pelvic sidewall structures, that is, the ureter and the pelvic vessels. Expose the ureter from the pelvic brim to the level of the uterine artery. The hypogastric artery is exposed as well in this process and the pararectal space developed.

When the PAS has extended laterally, perform stepwise division of the lateral attachments of the placenta to the pelvic sidewall using a combination of electrocautery, hemoclips, and the vessel-sealing device. In laterally extended PAS cases, it often is necessary to divide the uterine artery either at its origin or at the level of the ureter to allow for the completion of the separation of the placenta from the pelvic sidewall.

In our experience. During this lateral dissection, significant bleeding may be encountered from the neovascular network that has developed in the pelvic sidewall. The bleeding may be diffuse and difficult to control with the methods described above. In this situation, we have found that placing hemostatic agents in this area and packing the sidewall with laparotomy pads can achieve hemostasis in most cases, thus allowing the surgery to proceed.

1. Stop and collect your multidisciplinary team. If required resources are not available at your institution and the patient is stable, consider transferring her to the nearest center of expertise

2. Prepare for resuscitation: Have blood products available in the operating room and optimize IV access and arterial line

3. Optimize exposure of the surgical field: place in lithotomy position, extend fascial incision, perform hysterotomy to avoid the placenta, and expose pelvic sidewall and ureters

4. Be mindful of likely sources of massive bleeding: pelvic sidewall, bladder/vesicouterine space, and/or placenta previa vaginally

5. Proceed with meticulous dissection to minimize the risk of hemorrhage, retrograde fill the bladder, be mindful of the utility of packing

6. Be prepared to move to an expeditious hysterectomy in case of massive bleeding

Continue to: Bladder dissection...

Bladder dissection

The next critical part of the surgery involves developing the vesicovaginal space to mobilize the bladder. Prior to initiating the bladder dissection, we routinely retrograde fill the bladder with 180 to 240 mL of saline mixed with methylene blue. This delineates the superior edge of the bladder and indicates the appropriate level to start the dissection. Then slowly develop the vesicouterine space using a combination of electrocautery and a vessel-sealing device until the bladder is mobilized to the level of the anterior vaginal wall. Many vascular connections are encountered at that level, and meticulous dissection and patience is required to systematically divide them all.

In our experience. This part of the surgery presents several challenges. The bladder wall may be invaded by the placenta, which will lead to an increased risk of bleeding and cystotomy during the dissection. In these cases, it might be preferable to create an intentional cystotomy to guide the dissection; at times, a limited excision of the involved bladder wall may be required. In other cases, even in the absence of bladder wall invasion, the bladder may be densely adherent to the uterine wall (usually due to a history of prior CDs), and bladder mobilization may be complicated by bleeding from the neovascular network that has developed between the placenta and bladder.

Uterine arteries and cervix

Once the placenta is separated from its lateral attachments and the bladder is mobilized, the next steps are similar to those in a standard abdominal hysterectomy. If the uterine arteries were not yet divided during the pelvic sidewall dissection, they are clamped, divided, and suture ligated at the level of the uterine isthmus. The decision whether to perform a supracervical or total hysterectomy depends on the level of cervical involvement by the placenta, surgeon preference, anatomic distortion, and bleeding from the cervix and anterior vaginal wall.

Responding to massive bleeding

Not uncommonly, and despite the best efforts to avoid it, massive bleeding may develop from the areas at risk as noted above. If the bleeding is significant and originates from multiple areas (including vaginal bleeding from placenta previa), we recommend proceeding with an expeditious hysterectomy to remove the specimen, and then reassess the pelvic field for hemostatic control and any organ damage that may have occurred.

The challenge of PAS

Surgical management of PAS is one the most challenging procedures in pelvic surgery. Successful outcomes require a multidisciplinary team approach and an experienced team dedicated to the management of this condition.9 By contrast, proceeding “as usual” in the face of an unexpected PAS situation can lead to disastrous consequences in terms of maternal morbidity and mortality. ●

- Jauniaux E, Bunce C, Gronbeck L, et al. Prevalence and main outcomes of placenta accreta spectrum: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:208-218.

- Society of Gynecologic Oncology, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, et al. Placenta accreta spectrum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:B2-B16.

- Eller AG, Bennett MA, Sharshiner M, et al. Maternal morbidity in cases of placenta accreta managed by a multidisciplinary care team compared with standard obstetric care. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(2 pt 1):331-337.

- Shamshirsaz AA, Fox KA, Salmanian B, et al. Maternal morbidity in patients with morbidly adherent placenta treated with and without a standardized multidisciplinary approach. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:218.e1-9.

- Collins SL, Alemdar B, van Beekhuizen HJ, et al; International Society for Abnormally Invasive Placenta. Evidence-based guidelines for the management of abnormally invasive placenta: recommendations from the International Society for Abnormally Invasive Placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:511-526.

- Silver RM, Fox KA, Barton JR, et al. Center of excellence for placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:561-568.

- Tam Tam KB, Dozier J, Martin JN Jr. Approaches to reduce urinary tract injury during management of placenta accreta, increta, and percreta: a systematic review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25:329-334.

- Belfort MA, Shamshiraz AA, Fox K. Minimizing blood loss at cesarean-hysterectomy for placenta previa percreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:78.e1-78.e2.

- Shamshirsaz AA, Fox KA, Erfani H, et al. Multidisciplinary team learning in the management of the morbidly adherent placenta: outcome improvements over time. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:612.e1-612.e5.

CASE Concerning finding on repeat CD

A 30-year-old woman with a history of 1 prior cesarean delivery (CD) presents to labor and delivery at 38 weeks of gestation with symptoms of mild cramping. Her prenatal care was uncomplicated. The covering team made a decision to proceed with a repeat CD. A Pfannenstiel incision is made to enter the abdomen, and inspection of the lower uterine segment is concerning for a placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) (FIGURE).

What would be your next steps?

Placenta accreta spectrum describes the range of disorders of placental implantation, including placenta accreta, increta, and percreta. PAS is a significant cause of severe maternal morbidity and mortality, primarily due to massive hemorrhage at the time of delivery. The incidence of PAS continues to rise along with the CD rate. The authors of a recent meta-analysis reported a pooled prevalence rate of 1 in 588 women.1 Notably, in women with PAS, the rate of hysterectomy is 52.2%, and the transfusion-dependent hemorrhage rate is 46.9%.1

Ideally, PAS should be diagnosed or at least suspected antenatally during prenatal ultrasonography, leading to delivery planning by a multidisciplinary team.2 The presence of a multidisciplinary team—in addition to the primary obstetric and surgical teams—composed of experienced anesthesiologists, a blood bank able to respond to massive transfusion needs, critical care specialists, and interventional radiologists is associated with improved outcomes.3-5

Occasionally, a patient is found to have an advanced PAS (increta or percreta) at the time of delivery. In these situations, it is paramount that the appropriate resources be assembled as expeditiously as possible to optimize maternal outcomes. Surgical management can be challenging even for experienced pelvic surgeons, and appropriate resuscitation cannot be provided by a single anesthesiologist working alone. A cavalier attitude of proceeding with the delivery “as usual” in the face of an unexpected PAS situation can lead to disastrous consequences, including maternal death.

In this article, we review the important steps to take when faced with the unexpected situation of a PAS at the time of CD.

Continue to: Stop and collect your multidisciplinary team...

Stop and collect your multidisciplinary team

Once the diagnosis of an advanced PAS is suspected, the first step is to stop and request the presence of your institution’s multidisciplinary surgical team. This team typically includes a maternal-fetal specialist or, if not available, an experienced obstetrician, and an expert pelvic surgeon, which varies by institution (gynecologic oncologist, trauma surgeon, urologist, urogynecologist, vascular surgeon). An interventional radiology team is an additional useful resource that can assist with the control of pelvic hemorrhage using embolization techniques.

In our opinion, it is not appropriate to have a surgical backup team available only as needed at a certain distance from the hospital or even in the building. Because of the acuity and magnitude of bleeding that can occur in a short time, the most appropriate approach is to have your surgical team scrubbed and ready to assist or take over the procedure immediately if indicated.

Additional support staff also may be required. A single circulating nurse may not be sufficient, and available nursing staff may need to be called. The surgical technician scrubbed on the case may be familiar only with uncomplicated CDs and can be overwhelmed during a PAS case. Having a more experienced surgical technologist can optimize the availability of the appropriate instruments for the surgical team.

If a multidisciplinary surgical team with PAS management expertise is not available at your institution and the patient is stable, it is appropriate to consider transferring her to the nearest center that can meet the high-risk needs of this situation.6

Prepare for resuscitation

While you are calling your multidisciplinary team members, implement plans for resuscitation by notifying the anesthesiologist about the PAS findings. This will allow the gathering of needed resources that may include calling on additional anesthesiologists with experience in high-risk obstetrics, trauma, or critical care.

Placing large-bore intravenous lines or a central line to allow rapid transfusion is essential. Strongly consider inserting an arterial line for hemodynamic monitoring and intraoperative blood draws to monitor blood loss, blood gases, electrolytes, and coagulation parameters, which can guide resuscitative efforts and replacement therapies.

Simultaneously, inform the blood bank to prepare blood and blood products for possible activation of a massive transfusion protocol. It is imperative to have the products available in the operating room (OR) prior to proceeding with the surgery. Our current practice is to have 10 units of packed red blood cells and fresh frozen plasma available in the OR for all our prenatally diagnosed electively planned PAS cases.

Optimize exposure of the surgical field

Appropriate exposure of the surgical field is essential and should include exposure of the uterine fundus and the pelvic sidewalls. The uterine incision should avoid the placenta; typically it is placed at the level of the uterine fundus. Exposure of the pelvic sidewalls is needed to open the retroperitoneum and identify the ureter and the iliac vessels.

Vertical extension of the fascial incision probably will be needed to achieve appropriate exposure. Although at times this can be done without a concomitant vertical skin incision, often an inverted T incision is required. Be mindful that PAS is a life-threatening condition and that aesthetics are not a priority. After extending the fascial incision, adequate exposure can be achieved with any of the commonly used retractors or wound protectors (depending on institutional availability and surgeon preference) or by the surgical assistants using body wall retractors.

We routinely place the patient in lithotomy position. This allows us to monitor for vaginal bleeding (often a site of unrecognized massive hemorrhage) during the surgery, facilitate retrograde bladder filling, and provide a vaginal access to the pelvis. In addition, the lithotomy position allows for cystoscopy and placement of ureteral stents, which can be performed before starting the surgery to help prevent urinary tract injuries or at the end of the procedure in case one is suspected.7

Continue to: Performing the hysterectomy...

Performing the hysterectomy

A complete review of all surgical techniques for managing PAS is beyond the scope of this article. However, we briefly cover important procedural steps and offer suggestions on how to minimize the risk of bleeding.

In our experience. The areas with the highest risk of massive bleeding that can be difficult to control include the pelvic sidewall when there is lateral extension of the PAS, the vesicouterine space, and placenta previa vaginally. Be mindful of these areas at risk and have a plan in place in case of bleeding.

Uterine incision

Avoid the placenta when making the uterine incision, which is typically done in the fundal part of the uterus. Cut and tie the cord and return it to the uterine cavity. Close the incision in a single layer. Use of a surgical stapler can be used for the hysterotomy and can decrease the amount of blood loss.8

Superior attachments of the uterus

The superior attachments of the uterus include the round ligament, the utero-ovarian ligament, and the fallopian tubes. With meticulous dissection, develop an avascular space underneath these structures and, in turn, individually divide and suture ligate; this is typically achieved with minimal blood loss.

In addition, isolate the engorged veins of the broad ligament and divide them in a similar fashion.

In our experience. Use of a vessel-sealing device can facilitate division of all the former structures. Simply excise the fallopian tubes with the vessel-sealing device either at this time or after the uterus is removed.

Pelvic sidewall

Once the superior attachments of the uterus have been divided, the next step involves exposing the pelvic sidewall structures, that is, the ureter and the pelvic vessels. Expose the ureter from the pelvic brim to the level of the uterine artery. The hypogastric artery is exposed as well in this process and the pararectal space developed.

When the PAS has extended laterally, perform stepwise division of the lateral attachments of the placenta to the pelvic sidewall using a combination of electrocautery, hemoclips, and the vessel-sealing device. In laterally extended PAS cases, it often is necessary to divide the uterine artery either at its origin or at the level of the ureter to allow for the completion of the separation of the placenta from the pelvic sidewall.

In our experience. During this lateral dissection, significant bleeding may be encountered from the neovascular network that has developed in the pelvic sidewall. The bleeding may be diffuse and difficult to control with the methods described above. In this situation, we have found that placing hemostatic agents in this area and packing the sidewall with laparotomy pads can achieve hemostasis in most cases, thus allowing the surgery to proceed.

1. Stop and collect your multidisciplinary team. If required resources are not available at your institution and the patient is stable, consider transferring her to the nearest center of expertise

2. Prepare for resuscitation: Have blood products available in the operating room and optimize IV access and arterial line

3. Optimize exposure of the surgical field: place in lithotomy position, extend fascial incision, perform hysterotomy to avoid the placenta, and expose pelvic sidewall and ureters

4. Be mindful of likely sources of massive bleeding: pelvic sidewall, bladder/vesicouterine space, and/or placenta previa vaginally

5. Proceed with meticulous dissection to minimize the risk of hemorrhage, retrograde fill the bladder, be mindful of the utility of packing

6. Be prepared to move to an expeditious hysterectomy in case of massive bleeding

Continue to: Bladder dissection...

Bladder dissection

The next critical part of the surgery involves developing the vesicovaginal space to mobilize the bladder. Prior to initiating the bladder dissection, we routinely retrograde fill the bladder with 180 to 240 mL of saline mixed with methylene blue. This delineates the superior edge of the bladder and indicates the appropriate level to start the dissection. Then slowly develop the vesicouterine space using a combination of electrocautery and a vessel-sealing device until the bladder is mobilized to the level of the anterior vaginal wall. Many vascular connections are encountered at that level, and meticulous dissection and patience is required to systematically divide them all.

In our experience. This part of the surgery presents several challenges. The bladder wall may be invaded by the placenta, which will lead to an increased risk of bleeding and cystotomy during the dissection. In these cases, it might be preferable to create an intentional cystotomy to guide the dissection; at times, a limited excision of the involved bladder wall may be required. In other cases, even in the absence of bladder wall invasion, the bladder may be densely adherent to the uterine wall (usually due to a history of prior CDs), and bladder mobilization may be complicated by bleeding from the neovascular network that has developed between the placenta and bladder.

Uterine arteries and cervix

Once the placenta is separated from its lateral attachments and the bladder is mobilized, the next steps are similar to those in a standard abdominal hysterectomy. If the uterine arteries were not yet divided during the pelvic sidewall dissection, they are clamped, divided, and suture ligated at the level of the uterine isthmus. The decision whether to perform a supracervical or total hysterectomy depends on the level of cervical involvement by the placenta, surgeon preference, anatomic distortion, and bleeding from the cervix and anterior vaginal wall.

Responding to massive bleeding

Not uncommonly, and despite the best efforts to avoid it, massive bleeding may develop from the areas at risk as noted above. If the bleeding is significant and originates from multiple areas (including vaginal bleeding from placenta previa), we recommend proceeding with an expeditious hysterectomy to remove the specimen, and then reassess the pelvic field for hemostatic control and any organ damage that may have occurred.

The challenge of PAS

Surgical management of PAS is one the most challenging procedures in pelvic surgery. Successful outcomes require a multidisciplinary team approach and an experienced team dedicated to the management of this condition.9 By contrast, proceeding “as usual” in the face of an unexpected PAS situation can lead to disastrous consequences in terms of maternal morbidity and mortality. ●

CASE Concerning finding on repeat CD

A 30-year-old woman with a history of 1 prior cesarean delivery (CD) presents to labor and delivery at 38 weeks of gestation with symptoms of mild cramping. Her prenatal care was uncomplicated. The covering team made a decision to proceed with a repeat CD. A Pfannenstiel incision is made to enter the abdomen, and inspection of the lower uterine segment is concerning for a placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) (FIGURE).

What would be your next steps?

Placenta accreta spectrum describes the range of disorders of placental implantation, including placenta accreta, increta, and percreta. PAS is a significant cause of severe maternal morbidity and mortality, primarily due to massive hemorrhage at the time of delivery. The incidence of PAS continues to rise along with the CD rate. The authors of a recent meta-analysis reported a pooled prevalence rate of 1 in 588 women.1 Notably, in women with PAS, the rate of hysterectomy is 52.2%, and the transfusion-dependent hemorrhage rate is 46.9%.1

Ideally, PAS should be diagnosed or at least suspected antenatally during prenatal ultrasonography, leading to delivery planning by a multidisciplinary team.2 The presence of a multidisciplinary team—in addition to the primary obstetric and surgical teams—composed of experienced anesthesiologists, a blood bank able to respond to massive transfusion needs, critical care specialists, and interventional radiologists is associated with improved outcomes.3-5

Occasionally, a patient is found to have an advanced PAS (increta or percreta) at the time of delivery. In these situations, it is paramount that the appropriate resources be assembled as expeditiously as possible to optimize maternal outcomes. Surgical management can be challenging even for experienced pelvic surgeons, and appropriate resuscitation cannot be provided by a single anesthesiologist working alone. A cavalier attitude of proceeding with the delivery “as usual” in the face of an unexpected PAS situation can lead to disastrous consequences, including maternal death.

In this article, we review the important steps to take when faced with the unexpected situation of a PAS at the time of CD.

Continue to: Stop and collect your multidisciplinary team...

Stop and collect your multidisciplinary team

Once the diagnosis of an advanced PAS is suspected, the first step is to stop and request the presence of your institution’s multidisciplinary surgical team. This team typically includes a maternal-fetal specialist or, if not available, an experienced obstetrician, and an expert pelvic surgeon, which varies by institution (gynecologic oncologist, trauma surgeon, urologist, urogynecologist, vascular surgeon). An interventional radiology team is an additional useful resource that can assist with the control of pelvic hemorrhage using embolization techniques.

In our opinion, it is not appropriate to have a surgical backup team available only as needed at a certain distance from the hospital or even in the building. Because of the acuity and magnitude of bleeding that can occur in a short time, the most appropriate approach is to have your surgical team scrubbed and ready to assist or take over the procedure immediately if indicated.

Additional support staff also may be required. A single circulating nurse may not be sufficient, and available nursing staff may need to be called. The surgical technician scrubbed on the case may be familiar only with uncomplicated CDs and can be overwhelmed during a PAS case. Having a more experienced surgical technologist can optimize the availability of the appropriate instruments for the surgical team.

If a multidisciplinary surgical team with PAS management expertise is not available at your institution and the patient is stable, it is appropriate to consider transferring her to the nearest center that can meet the high-risk needs of this situation.6

Prepare for resuscitation

While you are calling your multidisciplinary team members, implement plans for resuscitation by notifying the anesthesiologist about the PAS findings. This will allow the gathering of needed resources that may include calling on additional anesthesiologists with experience in high-risk obstetrics, trauma, or critical care.

Placing large-bore intravenous lines or a central line to allow rapid transfusion is essential. Strongly consider inserting an arterial line for hemodynamic monitoring and intraoperative blood draws to monitor blood loss, blood gases, electrolytes, and coagulation parameters, which can guide resuscitative efforts and replacement therapies.

Simultaneously, inform the blood bank to prepare blood and blood products for possible activation of a massive transfusion protocol. It is imperative to have the products available in the operating room (OR) prior to proceeding with the surgery. Our current practice is to have 10 units of packed red blood cells and fresh frozen plasma available in the OR for all our prenatally diagnosed electively planned PAS cases.

Optimize exposure of the surgical field

Appropriate exposure of the surgical field is essential and should include exposure of the uterine fundus and the pelvic sidewalls. The uterine incision should avoid the placenta; typically it is placed at the level of the uterine fundus. Exposure of the pelvic sidewalls is needed to open the retroperitoneum and identify the ureter and the iliac vessels.

Vertical extension of the fascial incision probably will be needed to achieve appropriate exposure. Although at times this can be done without a concomitant vertical skin incision, often an inverted T incision is required. Be mindful that PAS is a life-threatening condition and that aesthetics are not a priority. After extending the fascial incision, adequate exposure can be achieved with any of the commonly used retractors or wound protectors (depending on institutional availability and surgeon preference) or by the surgical assistants using body wall retractors.

We routinely place the patient in lithotomy position. This allows us to monitor for vaginal bleeding (often a site of unrecognized massive hemorrhage) during the surgery, facilitate retrograde bladder filling, and provide a vaginal access to the pelvis. In addition, the lithotomy position allows for cystoscopy and placement of ureteral stents, which can be performed before starting the surgery to help prevent urinary tract injuries or at the end of the procedure in case one is suspected.7

Continue to: Performing the hysterectomy...

Performing the hysterectomy

A complete review of all surgical techniques for managing PAS is beyond the scope of this article. However, we briefly cover important procedural steps and offer suggestions on how to minimize the risk of bleeding.

In our experience. The areas with the highest risk of massive bleeding that can be difficult to control include the pelvic sidewall when there is lateral extension of the PAS, the vesicouterine space, and placenta previa vaginally. Be mindful of these areas at risk and have a plan in place in case of bleeding.

Uterine incision

Avoid the placenta when making the uterine incision, which is typically done in the fundal part of the uterus. Cut and tie the cord and return it to the uterine cavity. Close the incision in a single layer. Use of a surgical stapler can be used for the hysterotomy and can decrease the amount of blood loss.8

Superior attachments of the uterus

The superior attachments of the uterus include the round ligament, the utero-ovarian ligament, and the fallopian tubes. With meticulous dissection, develop an avascular space underneath these structures and, in turn, individually divide and suture ligate; this is typically achieved with minimal blood loss.

In addition, isolate the engorged veins of the broad ligament and divide them in a similar fashion.

In our experience. Use of a vessel-sealing device can facilitate division of all the former structures. Simply excise the fallopian tubes with the vessel-sealing device either at this time or after the uterus is removed.

Pelvic sidewall

Once the superior attachments of the uterus have been divided, the next step involves exposing the pelvic sidewall structures, that is, the ureter and the pelvic vessels. Expose the ureter from the pelvic brim to the level of the uterine artery. The hypogastric artery is exposed as well in this process and the pararectal space developed.

When the PAS has extended laterally, perform stepwise division of the lateral attachments of the placenta to the pelvic sidewall using a combination of electrocautery, hemoclips, and the vessel-sealing device. In laterally extended PAS cases, it often is necessary to divide the uterine artery either at its origin or at the level of the ureter to allow for the completion of the separation of the placenta from the pelvic sidewall.

In our experience. During this lateral dissection, significant bleeding may be encountered from the neovascular network that has developed in the pelvic sidewall. The bleeding may be diffuse and difficult to control with the methods described above. In this situation, we have found that placing hemostatic agents in this area and packing the sidewall with laparotomy pads can achieve hemostasis in most cases, thus allowing the surgery to proceed.

1. Stop and collect your multidisciplinary team. If required resources are not available at your institution and the patient is stable, consider transferring her to the nearest center of expertise

2. Prepare for resuscitation: Have blood products available in the operating room and optimize IV access and arterial line

3. Optimize exposure of the surgical field: place in lithotomy position, extend fascial incision, perform hysterotomy to avoid the placenta, and expose pelvic sidewall and ureters

4. Be mindful of likely sources of massive bleeding: pelvic sidewall, bladder/vesicouterine space, and/or placenta previa vaginally

5. Proceed with meticulous dissection to minimize the risk of hemorrhage, retrograde fill the bladder, be mindful of the utility of packing

6. Be prepared to move to an expeditious hysterectomy in case of massive bleeding

Continue to: Bladder dissection...

Bladder dissection

The next critical part of the surgery involves developing the vesicovaginal space to mobilize the bladder. Prior to initiating the bladder dissection, we routinely retrograde fill the bladder with 180 to 240 mL of saline mixed with methylene blue. This delineates the superior edge of the bladder and indicates the appropriate level to start the dissection. Then slowly develop the vesicouterine space using a combination of electrocautery and a vessel-sealing device until the bladder is mobilized to the level of the anterior vaginal wall. Many vascular connections are encountered at that level, and meticulous dissection and patience is required to systematically divide them all.

In our experience. This part of the surgery presents several challenges. The bladder wall may be invaded by the placenta, which will lead to an increased risk of bleeding and cystotomy during the dissection. In these cases, it might be preferable to create an intentional cystotomy to guide the dissection; at times, a limited excision of the involved bladder wall may be required. In other cases, even in the absence of bladder wall invasion, the bladder may be densely adherent to the uterine wall (usually due to a history of prior CDs), and bladder mobilization may be complicated by bleeding from the neovascular network that has developed between the placenta and bladder.

Uterine arteries and cervix

Once the placenta is separated from its lateral attachments and the bladder is mobilized, the next steps are similar to those in a standard abdominal hysterectomy. If the uterine arteries were not yet divided during the pelvic sidewall dissection, they are clamped, divided, and suture ligated at the level of the uterine isthmus. The decision whether to perform a supracervical or total hysterectomy depends on the level of cervical involvement by the placenta, surgeon preference, anatomic distortion, and bleeding from the cervix and anterior vaginal wall.

Responding to massive bleeding

Not uncommonly, and despite the best efforts to avoid it, massive bleeding may develop from the areas at risk as noted above. If the bleeding is significant and originates from multiple areas (including vaginal bleeding from placenta previa), we recommend proceeding with an expeditious hysterectomy to remove the specimen, and then reassess the pelvic field for hemostatic control and any organ damage that may have occurred.

The challenge of PAS

Surgical management of PAS is one the most challenging procedures in pelvic surgery. Successful outcomes require a multidisciplinary team approach and an experienced team dedicated to the management of this condition.9 By contrast, proceeding “as usual” in the face of an unexpected PAS situation can lead to disastrous consequences in terms of maternal morbidity and mortality. ●

- Jauniaux E, Bunce C, Gronbeck L, et al. Prevalence and main outcomes of placenta accreta spectrum: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:208-218.

- Society of Gynecologic Oncology, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, et al. Placenta accreta spectrum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:B2-B16.

- Eller AG, Bennett MA, Sharshiner M, et al. Maternal morbidity in cases of placenta accreta managed by a multidisciplinary care team compared with standard obstetric care. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(2 pt 1):331-337.

- Shamshirsaz AA, Fox KA, Salmanian B, et al. Maternal morbidity in patients with morbidly adherent placenta treated with and without a standardized multidisciplinary approach. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:218.e1-9.

- Collins SL, Alemdar B, van Beekhuizen HJ, et al; International Society for Abnormally Invasive Placenta. Evidence-based guidelines for the management of abnormally invasive placenta: recommendations from the International Society for Abnormally Invasive Placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:511-526.

- Silver RM, Fox KA, Barton JR, et al. Center of excellence for placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:561-568.

- Tam Tam KB, Dozier J, Martin JN Jr. Approaches to reduce urinary tract injury during management of placenta accreta, increta, and percreta: a systematic review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25:329-334.

- Belfort MA, Shamshiraz AA, Fox K. Minimizing blood loss at cesarean-hysterectomy for placenta previa percreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:78.e1-78.e2.

- Shamshirsaz AA, Fox KA, Erfani H, et al. Multidisciplinary team learning in the management of the morbidly adherent placenta: outcome improvements over time. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:612.e1-612.e5.

- Jauniaux E, Bunce C, Gronbeck L, et al. Prevalence and main outcomes of placenta accreta spectrum: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:208-218.

- Society of Gynecologic Oncology, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, et al. Placenta accreta spectrum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:B2-B16.

- Eller AG, Bennett MA, Sharshiner M, et al. Maternal morbidity in cases of placenta accreta managed by a multidisciplinary care team compared with standard obstetric care. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(2 pt 1):331-337.

- Shamshirsaz AA, Fox KA, Salmanian B, et al. Maternal morbidity in patients with morbidly adherent placenta treated with and without a standardized multidisciplinary approach. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:218.e1-9.

- Collins SL, Alemdar B, van Beekhuizen HJ, et al; International Society for Abnormally Invasive Placenta. Evidence-based guidelines for the management of abnormally invasive placenta: recommendations from the International Society for Abnormally Invasive Placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:511-526.

- Silver RM, Fox KA, Barton JR, et al. Center of excellence for placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:561-568.

- Tam Tam KB, Dozier J, Martin JN Jr. Approaches to reduce urinary tract injury during management of placenta accreta, increta, and percreta: a systematic review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25:329-334.

- Belfort MA, Shamshiraz AA, Fox K. Minimizing blood loss at cesarean-hysterectomy for placenta previa percreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:78.e1-78.e2.

- Shamshirsaz AA, Fox KA, Erfani H, et al. Multidisciplinary team learning in the management of the morbidly adherent placenta: outcome improvements over time. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:612.e1-612.e5.