User login

Mr. T, age 26, presents to the psychiatric emergency department with acutely worsening symptoms of schizophrenia. The treating team decides to admit him to the inpatient psychiatry unit. The patient agrees to admission bloodwork, but adamantly refuses a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) nasal swab, stating that he does not consent to “having COVID-19 injected into his nose.” His nurse pages the psychiatry resident on call, asking her for seclusion orders to be placed for the patient in order to quarantine him.

This case illustrates a quandary that has arisen during the COVID-19 era. Traditionally, the use of seclusion in inpatient psychiatry wards has been restricted to the management of violent or self-destructive behavior. Most guidelines advise that seclusion should be used only to ensure the immediate physical safety of a patient, staff members, or other patients.1 Using seclusion for other purposes, such as to quarantine patients suspected of having an infectious disease, raises ethical questions.

What is seclusion?

To best understand the questions that arise from the above scenario, a thorough understanding of the terminology used is needed. Although the terms “isolation,” “quarantine,” and “seclusion” are often used interchangeably, each has a distinct definition and unique history.

Isolation in a medical context refers to the practice of isolating people confirmed to have a disease from the general population. The earliest description of medical isolation dates back to the 7th century BC in the Book of Leviticus, which mentions a protocol for separating individuals infected with leprosy from those who are healthy.2

Quarantine hearkens back to the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, the Black Death. In 1377, on the advice of the city’s chief physician, the Mediterranean seaport of Ragusa passed a law establishing an isolation period for all visitors from plague-endemic lands.2 Initially a 30-day isolation period (a trentino), this was extended to 40 days (a quarantino). Distinct from isolation, quarantine is the practice of limiting movements of apparently healthy individuals who may have been exposed to a disease but do not have a confirmed diagnosis.

Seclusion, a term used most often in psychiatry, is defined as “the involuntary confinement of a patient alone in a room or area from which the patient is physically prevented from leaving.”3 The use of seclusion rooms in psychiatric facilities was originally championed by the 19th century British psychiatrist John Conolly.4 In The Treatment of the Insane without Mechanical Restraints, Conolly argued that a padded seclusion room was far more humane and effective in calming a violent patient than mechanical restraints. After exhausting less restrictive measures, seclusion is one of the most common means of restraining violent patients in inpatient psychiatric facilities.

Why consider seclusion?

The discussion of using seclusion as a means of quarantine has arisen recently due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This infectious disease was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, China.5 Since then, it has spread rapidly across the world. As of mid-October 2020, >39 million cases across 189 countries had been reported.6 The primary means by which the virus is spread is through respiratory droplets released from infected individuals through coughing, sneezing, or talking.7 These droplets can remain airborne or fall onto surfaces that become fomites. Transmission is possible before symptoms appear in an infected individual or even from individuals who are asymptomatic.8

Continue to: The typical layout and requirements...

The typical layout and requirements of an inpatient psychiatric ward intensify the risk of COVID-19 transmission.9 Unlike most medical specialty wards, psychiatric wards are set up with a therapeutic milieu where patients have the opportunity to mingle and interact with each other and staff members. Patients are allowed to walk around the unit, spend time in group therapy, eat meals with each other, and have visitation hours. The therapeutic benefit of such a milieu, however, must be weighed against the risks that patients pose to staff members and other patients. While many facilities have restricted some of these activities to limit COVID-19 exposure, the overall risk of transmission is still elevated. Early in course of the pandemic, the virus spread to an inpatient psychiatric ward in South Korea. Although health officials put the ward on lockdown, given the heightened risk of transmission, the virus quickly spread from patient to patient. Out of 103 inpatients, 101 contracted COVID-19.10

To mitigate this risk, many inpatient psychiatric facilities have mandated that all newly admitted patients be tested for COVID-19. By obtaining COVID-19 testing, facilities are better able to risk stratify their patient population and appropriately protect all patients. A dilemma arises, however, when a patient refuses to consent to COVID-19 testing. In such cases, the infectious risk of the patient remains unknown. Given the potentially disastrous consequences of an unchecked COVID-19 infection running rampant in an inpatient ward, some facilities have elected to use seclusion as a means of quarantining the patient.

Is seclusion justifiable?

There are legitimate objections to using seclusion as a means of quarantine. Most guidelines state that the only time seclusion is ethical is when it is used to prevent immediate physical danger, either to the patient or others.11 Involuntary confinement entails considerable restriction of a patient’s rights and thus should be used only after all other options have been exhausted. People opposed to the use of seclusion point out that outside of the hospital, people are not forcibly restrained in order to enforce social distancing,12 so by extension, those who are inside the hospital should not be forced to seclude.

Seclusion also comes with potentially harmful effects. For the 14 days that a patient is in quarantine, they are cut off from most social contact, which is the opposite of the intended purpose of the therapeutic milieu in inpatient psychiatric wards. Several quantitative studies have shown that individuals who are quarantined tend to report a high prevalence of symptoms of psychological distress, including low mood, irritability, depression, stress, anger, and posttraumatic stress disorder.13

Furthermore, there is considerable evidence that a negative test does not definitively rule out a COVID-19 infection. Nasal swabs for COVID-19 have a false-negative rate of 27%.14 In other words, patients on an inpatient psychiatry ward who are free to walk around the unit and interact with others are only probably COVID-19 free, not definitively. This fact throws into question the original justification for seclusion—to protect other patients from COVID-19.

Continue to: Support for using seclusion as quarantine

Support for using seclusion as quarantine

Despite these objections, there are clear arguments in favor of using seclusion as a means of quarantine. First, the danger posed by an unidentified COVID-19 infection to the inpatient psychiatric population is not small. As of mid-October 2020, >217,000 Americans had died of COVID-19.6 Psychiatric patients, especially those who are acutely decompensated and hospitalized, have a heightened risk.15 Those with underlying medical issues are more likely to be seriously affected by an infection. Patients with serious mental illness have higher rates of medical comorbidities16 and premature death.17 The risk of a patient contracting and then dying from COVID-19 is elevated in an inpatient psychiatric ward. Even if a test is not 100% sensitive or specific, the balance of probability it provides is sufficient to make an informed decision about transmission risk.

In choosing to seclude a patient who refuses COVID-19 testing, the treating team must weigh one person’s autonomy against the safety of every other individual on the ward. From a purely utilitarian perspective, the lives of the many outweigh the discomfort of one. Addressing this balance, the American Medical Association (AMA) Code of Ethics states “Although physicians’ primary ethical obligation is to their individual patients, they also have a long-recognized public health responsibility. In the context of infectious disease, this may include the use of quarantine and isolation to reduce the transmission of disease and protect the health of the public. In such situations, physicians have a further responsibility to protect their own health to ensure that they remain able to provide care. These responsibilities potentially conflict with patients’ rights of self-determination and with physicians’ duty to advocate for the best interests of individual patients and to provide care in emergencies.”18

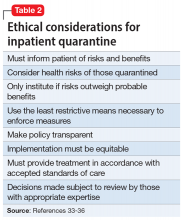

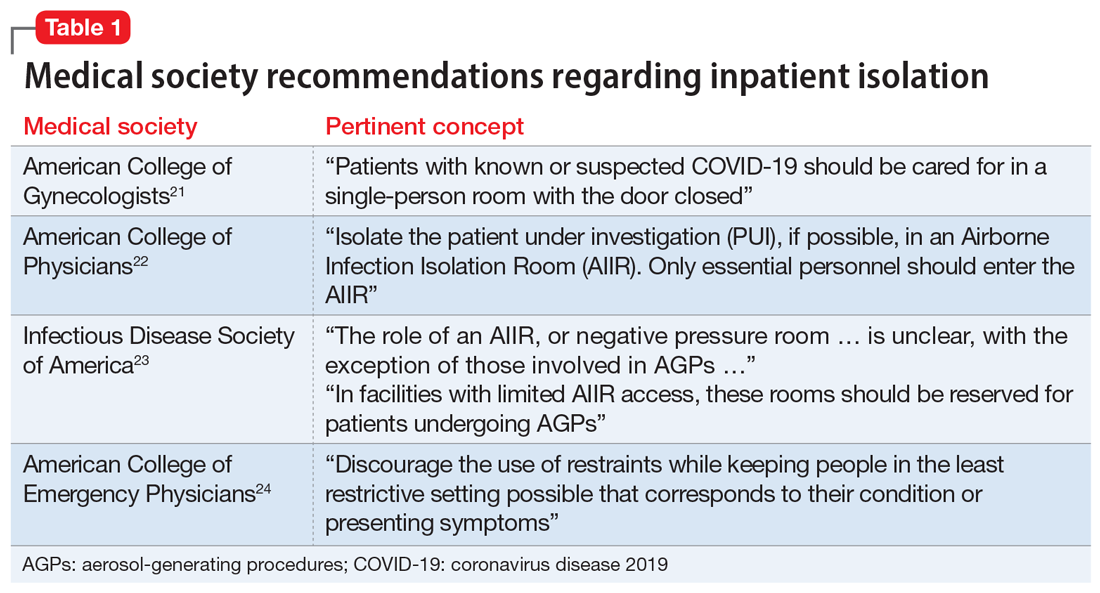

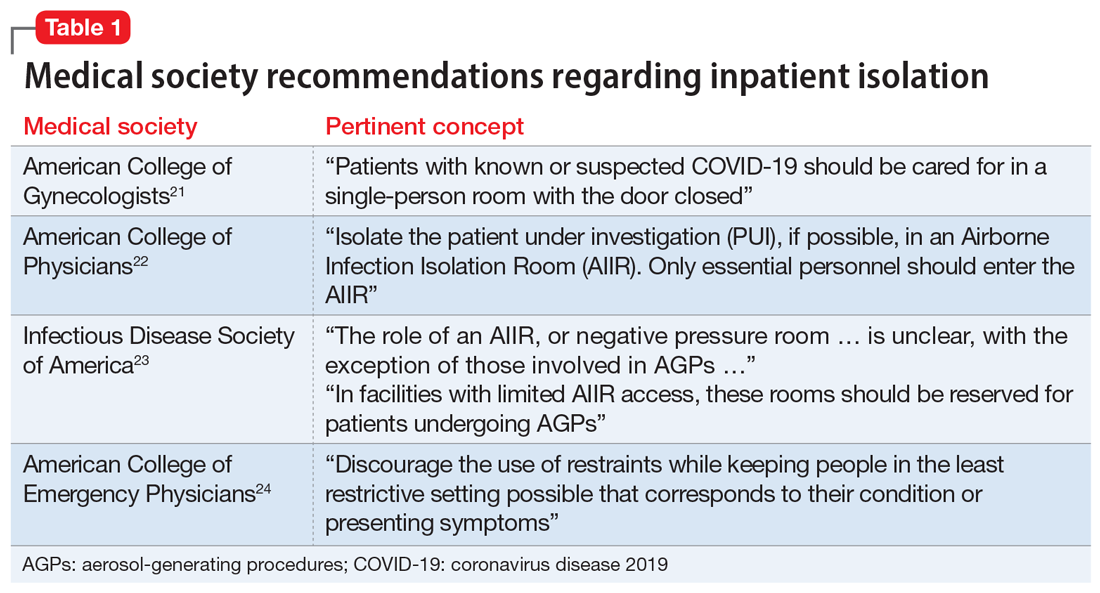

The AMA Code of Ethics further mentions that physicians should “support mandatory quarantine and isolation when a patient fails to adhere voluntarily.” Medical evidence supports both quarantine19 and enacting isolation measures for COVID-19–positive hospitalized patients.20 Table 121-24 summarizes the recommendations of major medical societies regarding isolation on hospital units.

Further, public health officials and law enforcement officials do in fact have the authority25 to enforce quarantine and restrict a citizen’s movement outside a hospital setting. Recent cases have illustrated how this has been enforced, particularly with the use of electronic monitoring units and even criminal sanctions.26,27

It is also important to consider that when used as quarantine, seclusion is not an indefinite action. Current recommendations suggest the longest period of time a patient would need to be in seclusion is 14 days. A patient could potentially reduce this period by agreeing to COVID-19 testing and obtaining a negative test result.

Continue to: Enacting inpatient quarantine

Enacting inpatient quarantine

In Mr. T’s case, the resident physician was asked to make a decision regarding seclusion on the spot. Prudent facilities will set policies and educate clinicians before they need to face this conundrum. The following practical considerations may guide implementation of seclusion as a measure of quarantine on an inpatient psychiatric unit:

- given the risk of asymptomatic carriers, all admitted patients should be tested for COVID-19

- patients who refuse a test should be evaluated by the psychiatrist on duty to determine if the patient has the capacity to make this decision

- if a patient demonstrates capacity to refuse and continues to refuse testing, seclusion orders should then be placed

- the facility should create a protocol to ensure consistent application of seclusion orders.

So that they can make an informed decision, patients should be educated about the risks of not undergoing testing. It is important to correctly frame a seclusion decision to the patient. Explain that seclusion is not a punitive measure, but rather a means of respecting the patient’s right to refuse testing while ensuring other patients’ right to be protected from COVID-19 transmission.

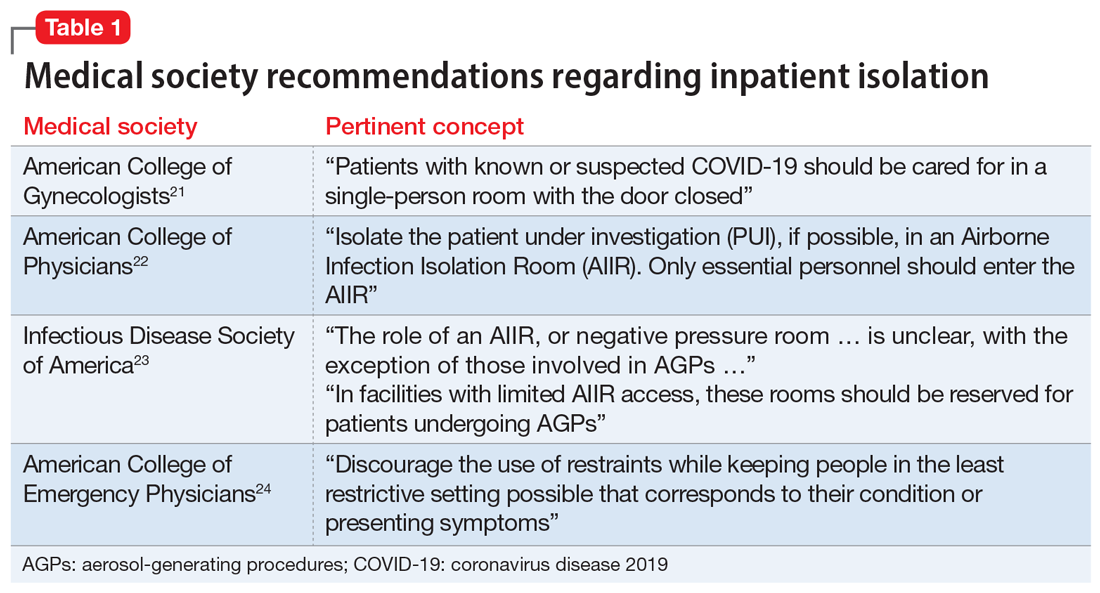

It is crucial to not allow psychiatric care to be diminished because a patient is isolated due to COVID-19. Psychiatrists have legal duties to provide care when a patient is admitted to their unit,28-30 and state laws generally outline patients’ rights while they are hospitalized.31 The use of technology can ensure these duties are fulfilled. Patient rounds and group treatment can be conducted through telehealth.10,32 When in-person interaction is required, caretakers should don proper personal protective equipment and interact with the patient as often as they would if the patient were not in seclusion. Table 233-36 summarizes further ethical considerations when implementing quarantine measures on a psychiatry unit.

The contemporary inpatient unit

The ideal design to optimize care and safety is to create designated COVID-19 psychiatric units. Indeed, the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration recommends segregating floors based on infection status where possible.37 This minimizes the risk of transmission to other patients while maintaining the same standards of psychiatric treatment, including milieu and group therapy (which may also require adjustments). Such a unit already has precedent.38 Although designated COVID-19 psychiatric units present clinical and administrative hurdles,39 they may become more commonplace as the number of COVID-19–positive inpatients continues to rise.

Bottom Line

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has created challenges for inpatient psychiatric facilities. Although seclusion is a serious decision and should not be undertaken lightly, there are clear ethical and practical justifications for using it as a means of quarantine for patients who are COVID-19–positive or refuse testing.

Related Resources

- Askew L, Fisher P, Beazley P. What are adult psychiatric inpatients’ experience of seclusion: a systematic review of qualitative studies. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2019; 26(7-8):274-285.

- Komrad MS. Medical ethics in the time of COVID-19. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(7):29-32,46.

1. Knox DK, Holloman GH Jr. Use and avoidance of seclusion and restraint: consensus statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry Project BETA Seclusion and Restraint Workgroup. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13(1):35-40.

2. Sehdev PS. The origin of quarantine. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35(9):1071-1072.

3. 42 CFR § 482.13. Condition of participation: patient’s rights.

4. Colaizzi J. Seclusion & restraint: a historical perspective. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2005;43(2):31-37.

5. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497-506.

6. COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). ArcGIS. Johns Hopkins University. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Accessed October 16, 2020.

7. Guo YR, Cao QD, Hong ZS, et al. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak - an update on the status. Mil Med Res. 2020;7(1):11.

8. Bai Y, Yao L, Wei T, et al. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(14):1406-1407.

9. Li L. Challenges and priorities in responding to COVID-19 in inpatient psychiatry. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(6):624-626.

10. Kim MJ. ‘It was a medical disaster’: the psychiatric ward that saw 100 patients diagnosed with new coronavirus. Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/coronavirus-south-korea-outbreak-hospital-patients-lockdown-a9367486.html. Published March 1, 2020. Accessed July 12, 2020.

11. Petrini C. Ethical considerations for evaluating the issue of physical restraint in psychiatry. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2013;49(3):281-285.

12. Gessen M. Why psychiatric wards are uniquely vulnerable to the coronavirus. https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/why-psychiatric-wards-are-uniquely-vulnerable-to-the-coronavirus. Published April 21, 2020. Accessed July 12, 2020.

13. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith, LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912-920.

14. Woloshin S, Patel N, Kesselheim AS. False negative tests for SARS-CoV-2 infection—challenges and implications. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):e38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2015897.

15. Druss BG. Addressing the COVID-19 pandemic in populations with serious mental illness. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(9):891-892.

16. Rao S, Raney L, Xiong GL. Reducing medical comorbidity and mortality in severe mental illness. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(7):14-20.

17. Plana-Ripoll O, Pedersen CB, Agerbo E, et al. A comprehensive analysis of mortality-related health metrics associated with mental disorders: a nationwide, register-based cohort study. Lancet. 2019;394(10211):1827-1835.

18. American Medical Association. Ethical use of quarantine and isolation. Code of Ethics Opinion 8.4. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/ethical-use-quarantine-isolation. Published November 14, 2016. Accessed July 12, 2020.

19. Nussbaumer-Streit B, Mayr V, Dobrescu AI, et al. Quarantine alone or in combination with other public health measures to control COVID-19: a rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;4(4):CD013574.

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Duration of isolation & precautions for adults. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/duration-isolation.html. Updated August 16, 2020. Accessed August 21, 2020.

21. American College of Gynecologists. Novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2020/03/novel-coronavirus-2019. Updated August 12, 2020. Accessed August 26, 2020.

22. American College of Physicians. COVID-19: an ACP physician’s guide + resources. Chapter 14 of 31. Infection control: advice for physicians. https://assets.acponline.org/coronavirus/scormcontent/#/. Updated September 3, 2020. Accessed September 9, 2020.

23. Infectious Disease Society of America. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines on Infection Prevention in Patients with Suspected or Known COVID-19. https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/covid-19-guideline-infection-prevention/#toc-9-9. Updated April 20, 2020. Accessed August 26, 2020.

24. American College of Emergency Physicians. Joint Statement for Care of Patients with Behavioral Health Emergencies and Suspected or Confirmed COVID-19. https://www.acep.org/corona/covid-19-field-guide/special-populations/behavioral-health-patients/. Updated June 17, 2020. Accessed August 26, 2020.

25. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Quarantine and isolation. Legal authorities. https://www.cdc.gov/quarantine/aboutlawsregulationsquarantineisolation.html. Updated February 24, 2020. Accessed August 31, 2020.

26. Roberts A. Kentucky couple under house arrest after refusing to sign self-quarantine agreement. https://abcnews.go.com/US/kentucky-couple-house-arrest-refusing-sign-quarantine-agreement/story?id=71886479. Published July 20, 2020. Accessed July 24, 2020.

27. Satter R. To keep COVID-19 patients home, some U.S. states weigh house arrest tech. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-quarantine-tech/to-keep-covid-19-patients-home-some-us-states-weigh-house-arrest-tech-idUSKBN22J1U8. Published May 7, 2020. Accessed July 24, 2020.

28. Rouse v Cameron, 373, F2d 451 (DC Cir 1966).

29. Wyatt v Stickney, 325 F Supp 781 (MD Ala 1971).

30. Donaldson v O’Connor, 519, F2d 59 (5th Cir 1975).

31. Ohio Revised Code § 5122.290.

32. Shore JH. Telepsychiatry: videoconferencing in the delivery of psychiatric care. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(3):256-262.

33. Bostick NA, Levine MA, Sade RM. Ethical obligations of physicians participating in public health quarantine and isolation measures. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(1):3-8.

34. Upshur RE. Principles for the justification of public health intervention. Can J Public Health. 2002;93(2):101-103.

35. Barbera J, Macintyre A, Gostin L, et al. Large-scale quarantine following biological terrorism in the United States: scientific examination, logistic and legal limits, and possible consequences. JAMA. 2001;286(21):2711-2717.

36. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Doctrine of double effect. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/double-effect/. Revised December 24, 2018. Accessed July 12, 2020.

37. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Covid19: interim considerations for state psychiatric hospitals. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/covid19-interim-considerations-for-state-psychiatric-hospitals.pdf. Updated May 8, 2020. Accessed July 24, 2020.

38. Augenstein TM, Pigeon WR, DiGiovanni SK, et al. Creating a novel inpatient psychiatric unit with integrated medical support for patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med Catalyst. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0249. Published June 22, 2020. Accessed July 12, 2020.

39. Bojdani E, Rajagopalan A, Chen A, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: impact on psychiatric care in the United States. Psychiatry Research. 2020;289:113069. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113069.

Mr. T, age 26, presents to the psychiatric emergency department with acutely worsening symptoms of schizophrenia. The treating team decides to admit him to the inpatient psychiatry unit. The patient agrees to admission bloodwork, but adamantly refuses a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) nasal swab, stating that he does not consent to “having COVID-19 injected into his nose.” His nurse pages the psychiatry resident on call, asking her for seclusion orders to be placed for the patient in order to quarantine him.

This case illustrates a quandary that has arisen during the COVID-19 era. Traditionally, the use of seclusion in inpatient psychiatry wards has been restricted to the management of violent or self-destructive behavior. Most guidelines advise that seclusion should be used only to ensure the immediate physical safety of a patient, staff members, or other patients.1 Using seclusion for other purposes, such as to quarantine patients suspected of having an infectious disease, raises ethical questions.

What is seclusion?

To best understand the questions that arise from the above scenario, a thorough understanding of the terminology used is needed. Although the terms “isolation,” “quarantine,” and “seclusion” are often used interchangeably, each has a distinct definition and unique history.

Isolation in a medical context refers to the practice of isolating people confirmed to have a disease from the general population. The earliest description of medical isolation dates back to the 7th century BC in the Book of Leviticus, which mentions a protocol for separating individuals infected with leprosy from those who are healthy.2

Quarantine hearkens back to the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, the Black Death. In 1377, on the advice of the city’s chief physician, the Mediterranean seaport of Ragusa passed a law establishing an isolation period for all visitors from plague-endemic lands.2 Initially a 30-day isolation period (a trentino), this was extended to 40 days (a quarantino). Distinct from isolation, quarantine is the practice of limiting movements of apparently healthy individuals who may have been exposed to a disease but do not have a confirmed diagnosis.

Seclusion, a term used most often in psychiatry, is defined as “the involuntary confinement of a patient alone in a room or area from which the patient is physically prevented from leaving.”3 The use of seclusion rooms in psychiatric facilities was originally championed by the 19th century British psychiatrist John Conolly.4 In The Treatment of the Insane without Mechanical Restraints, Conolly argued that a padded seclusion room was far more humane and effective in calming a violent patient than mechanical restraints. After exhausting less restrictive measures, seclusion is one of the most common means of restraining violent patients in inpatient psychiatric facilities.

Why consider seclusion?

The discussion of using seclusion as a means of quarantine has arisen recently due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This infectious disease was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, China.5 Since then, it has spread rapidly across the world. As of mid-October 2020, >39 million cases across 189 countries had been reported.6 The primary means by which the virus is spread is through respiratory droplets released from infected individuals through coughing, sneezing, or talking.7 These droplets can remain airborne or fall onto surfaces that become fomites. Transmission is possible before symptoms appear in an infected individual or even from individuals who are asymptomatic.8

Continue to: The typical layout and requirements...

The typical layout and requirements of an inpatient psychiatric ward intensify the risk of COVID-19 transmission.9 Unlike most medical specialty wards, psychiatric wards are set up with a therapeutic milieu where patients have the opportunity to mingle and interact with each other and staff members. Patients are allowed to walk around the unit, spend time in group therapy, eat meals with each other, and have visitation hours. The therapeutic benefit of such a milieu, however, must be weighed against the risks that patients pose to staff members and other patients. While many facilities have restricted some of these activities to limit COVID-19 exposure, the overall risk of transmission is still elevated. Early in course of the pandemic, the virus spread to an inpatient psychiatric ward in South Korea. Although health officials put the ward on lockdown, given the heightened risk of transmission, the virus quickly spread from patient to patient. Out of 103 inpatients, 101 contracted COVID-19.10

To mitigate this risk, many inpatient psychiatric facilities have mandated that all newly admitted patients be tested for COVID-19. By obtaining COVID-19 testing, facilities are better able to risk stratify their patient population and appropriately protect all patients. A dilemma arises, however, when a patient refuses to consent to COVID-19 testing. In such cases, the infectious risk of the patient remains unknown. Given the potentially disastrous consequences of an unchecked COVID-19 infection running rampant in an inpatient ward, some facilities have elected to use seclusion as a means of quarantining the patient.

Is seclusion justifiable?

There are legitimate objections to using seclusion as a means of quarantine. Most guidelines state that the only time seclusion is ethical is when it is used to prevent immediate physical danger, either to the patient or others.11 Involuntary confinement entails considerable restriction of a patient’s rights and thus should be used only after all other options have been exhausted. People opposed to the use of seclusion point out that outside of the hospital, people are not forcibly restrained in order to enforce social distancing,12 so by extension, those who are inside the hospital should not be forced to seclude.

Seclusion also comes with potentially harmful effects. For the 14 days that a patient is in quarantine, they are cut off from most social contact, which is the opposite of the intended purpose of the therapeutic milieu in inpatient psychiatric wards. Several quantitative studies have shown that individuals who are quarantined tend to report a high prevalence of symptoms of psychological distress, including low mood, irritability, depression, stress, anger, and posttraumatic stress disorder.13

Furthermore, there is considerable evidence that a negative test does not definitively rule out a COVID-19 infection. Nasal swabs for COVID-19 have a false-negative rate of 27%.14 In other words, patients on an inpatient psychiatry ward who are free to walk around the unit and interact with others are only probably COVID-19 free, not definitively. This fact throws into question the original justification for seclusion—to protect other patients from COVID-19.

Continue to: Support for using seclusion as quarantine

Support for using seclusion as quarantine

Despite these objections, there are clear arguments in favor of using seclusion as a means of quarantine. First, the danger posed by an unidentified COVID-19 infection to the inpatient psychiatric population is not small. As of mid-October 2020, >217,000 Americans had died of COVID-19.6 Psychiatric patients, especially those who are acutely decompensated and hospitalized, have a heightened risk.15 Those with underlying medical issues are more likely to be seriously affected by an infection. Patients with serious mental illness have higher rates of medical comorbidities16 and premature death.17 The risk of a patient contracting and then dying from COVID-19 is elevated in an inpatient psychiatric ward. Even if a test is not 100% sensitive or specific, the balance of probability it provides is sufficient to make an informed decision about transmission risk.

In choosing to seclude a patient who refuses COVID-19 testing, the treating team must weigh one person’s autonomy against the safety of every other individual on the ward. From a purely utilitarian perspective, the lives of the many outweigh the discomfort of one. Addressing this balance, the American Medical Association (AMA) Code of Ethics states “Although physicians’ primary ethical obligation is to their individual patients, they also have a long-recognized public health responsibility. In the context of infectious disease, this may include the use of quarantine and isolation to reduce the transmission of disease and protect the health of the public. In such situations, physicians have a further responsibility to protect their own health to ensure that they remain able to provide care. These responsibilities potentially conflict with patients’ rights of self-determination and with physicians’ duty to advocate for the best interests of individual patients and to provide care in emergencies.”18

The AMA Code of Ethics further mentions that physicians should “support mandatory quarantine and isolation when a patient fails to adhere voluntarily.” Medical evidence supports both quarantine19 and enacting isolation measures for COVID-19–positive hospitalized patients.20 Table 121-24 summarizes the recommendations of major medical societies regarding isolation on hospital units.

Further, public health officials and law enforcement officials do in fact have the authority25 to enforce quarantine and restrict a citizen’s movement outside a hospital setting. Recent cases have illustrated how this has been enforced, particularly with the use of electronic monitoring units and even criminal sanctions.26,27

It is also important to consider that when used as quarantine, seclusion is not an indefinite action. Current recommendations suggest the longest period of time a patient would need to be in seclusion is 14 days. A patient could potentially reduce this period by agreeing to COVID-19 testing and obtaining a negative test result.

Continue to: Enacting inpatient quarantine

Enacting inpatient quarantine

In Mr. T’s case, the resident physician was asked to make a decision regarding seclusion on the spot. Prudent facilities will set policies and educate clinicians before they need to face this conundrum. The following practical considerations may guide implementation of seclusion as a measure of quarantine on an inpatient psychiatric unit:

- given the risk of asymptomatic carriers, all admitted patients should be tested for COVID-19

- patients who refuse a test should be evaluated by the psychiatrist on duty to determine if the patient has the capacity to make this decision

- if a patient demonstrates capacity to refuse and continues to refuse testing, seclusion orders should then be placed

- the facility should create a protocol to ensure consistent application of seclusion orders.

So that they can make an informed decision, patients should be educated about the risks of not undergoing testing. It is important to correctly frame a seclusion decision to the patient. Explain that seclusion is not a punitive measure, but rather a means of respecting the patient’s right to refuse testing while ensuring other patients’ right to be protected from COVID-19 transmission.

It is crucial to not allow psychiatric care to be diminished because a patient is isolated due to COVID-19. Psychiatrists have legal duties to provide care when a patient is admitted to their unit,28-30 and state laws generally outline patients’ rights while they are hospitalized.31 The use of technology can ensure these duties are fulfilled. Patient rounds and group treatment can be conducted through telehealth.10,32 When in-person interaction is required, caretakers should don proper personal protective equipment and interact with the patient as often as they would if the patient were not in seclusion. Table 233-36 summarizes further ethical considerations when implementing quarantine measures on a psychiatry unit.

The contemporary inpatient unit

The ideal design to optimize care and safety is to create designated COVID-19 psychiatric units. Indeed, the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration recommends segregating floors based on infection status where possible.37 This minimizes the risk of transmission to other patients while maintaining the same standards of psychiatric treatment, including milieu and group therapy (which may also require adjustments). Such a unit already has precedent.38 Although designated COVID-19 psychiatric units present clinical and administrative hurdles,39 they may become more commonplace as the number of COVID-19–positive inpatients continues to rise.

Bottom Line

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has created challenges for inpatient psychiatric facilities. Although seclusion is a serious decision and should not be undertaken lightly, there are clear ethical and practical justifications for using it as a means of quarantine for patients who are COVID-19–positive or refuse testing.

Related Resources

- Askew L, Fisher P, Beazley P. What are adult psychiatric inpatients’ experience of seclusion: a systematic review of qualitative studies. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2019; 26(7-8):274-285.

- Komrad MS. Medical ethics in the time of COVID-19. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(7):29-32,46.

Mr. T, age 26, presents to the psychiatric emergency department with acutely worsening symptoms of schizophrenia. The treating team decides to admit him to the inpatient psychiatry unit. The patient agrees to admission bloodwork, but adamantly refuses a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) nasal swab, stating that he does not consent to “having COVID-19 injected into his nose.” His nurse pages the psychiatry resident on call, asking her for seclusion orders to be placed for the patient in order to quarantine him.

This case illustrates a quandary that has arisen during the COVID-19 era. Traditionally, the use of seclusion in inpatient psychiatry wards has been restricted to the management of violent or self-destructive behavior. Most guidelines advise that seclusion should be used only to ensure the immediate physical safety of a patient, staff members, or other patients.1 Using seclusion for other purposes, such as to quarantine patients suspected of having an infectious disease, raises ethical questions.

What is seclusion?

To best understand the questions that arise from the above scenario, a thorough understanding of the terminology used is needed. Although the terms “isolation,” “quarantine,” and “seclusion” are often used interchangeably, each has a distinct definition and unique history.

Isolation in a medical context refers to the practice of isolating people confirmed to have a disease from the general population. The earliest description of medical isolation dates back to the 7th century BC in the Book of Leviticus, which mentions a protocol for separating individuals infected with leprosy from those who are healthy.2

Quarantine hearkens back to the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, the Black Death. In 1377, on the advice of the city’s chief physician, the Mediterranean seaport of Ragusa passed a law establishing an isolation period for all visitors from plague-endemic lands.2 Initially a 30-day isolation period (a trentino), this was extended to 40 days (a quarantino). Distinct from isolation, quarantine is the practice of limiting movements of apparently healthy individuals who may have been exposed to a disease but do not have a confirmed diagnosis.

Seclusion, a term used most often in psychiatry, is defined as “the involuntary confinement of a patient alone in a room or area from which the patient is physically prevented from leaving.”3 The use of seclusion rooms in psychiatric facilities was originally championed by the 19th century British psychiatrist John Conolly.4 In The Treatment of the Insane without Mechanical Restraints, Conolly argued that a padded seclusion room was far more humane and effective in calming a violent patient than mechanical restraints. After exhausting less restrictive measures, seclusion is one of the most common means of restraining violent patients in inpatient psychiatric facilities.

Why consider seclusion?

The discussion of using seclusion as a means of quarantine has arisen recently due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This infectious disease was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, China.5 Since then, it has spread rapidly across the world. As of mid-October 2020, >39 million cases across 189 countries had been reported.6 The primary means by which the virus is spread is through respiratory droplets released from infected individuals through coughing, sneezing, or talking.7 These droplets can remain airborne or fall onto surfaces that become fomites. Transmission is possible before symptoms appear in an infected individual or even from individuals who are asymptomatic.8

Continue to: The typical layout and requirements...

The typical layout and requirements of an inpatient psychiatric ward intensify the risk of COVID-19 transmission.9 Unlike most medical specialty wards, psychiatric wards are set up with a therapeutic milieu where patients have the opportunity to mingle and interact with each other and staff members. Patients are allowed to walk around the unit, spend time in group therapy, eat meals with each other, and have visitation hours. The therapeutic benefit of such a milieu, however, must be weighed against the risks that patients pose to staff members and other patients. While many facilities have restricted some of these activities to limit COVID-19 exposure, the overall risk of transmission is still elevated. Early in course of the pandemic, the virus spread to an inpatient psychiatric ward in South Korea. Although health officials put the ward on lockdown, given the heightened risk of transmission, the virus quickly spread from patient to patient. Out of 103 inpatients, 101 contracted COVID-19.10

To mitigate this risk, many inpatient psychiatric facilities have mandated that all newly admitted patients be tested for COVID-19. By obtaining COVID-19 testing, facilities are better able to risk stratify their patient population and appropriately protect all patients. A dilemma arises, however, when a patient refuses to consent to COVID-19 testing. In such cases, the infectious risk of the patient remains unknown. Given the potentially disastrous consequences of an unchecked COVID-19 infection running rampant in an inpatient ward, some facilities have elected to use seclusion as a means of quarantining the patient.

Is seclusion justifiable?

There are legitimate objections to using seclusion as a means of quarantine. Most guidelines state that the only time seclusion is ethical is when it is used to prevent immediate physical danger, either to the patient or others.11 Involuntary confinement entails considerable restriction of a patient’s rights and thus should be used only after all other options have been exhausted. People opposed to the use of seclusion point out that outside of the hospital, people are not forcibly restrained in order to enforce social distancing,12 so by extension, those who are inside the hospital should not be forced to seclude.

Seclusion also comes with potentially harmful effects. For the 14 days that a patient is in quarantine, they are cut off from most social contact, which is the opposite of the intended purpose of the therapeutic milieu in inpatient psychiatric wards. Several quantitative studies have shown that individuals who are quarantined tend to report a high prevalence of symptoms of psychological distress, including low mood, irritability, depression, stress, anger, and posttraumatic stress disorder.13

Furthermore, there is considerable evidence that a negative test does not definitively rule out a COVID-19 infection. Nasal swabs for COVID-19 have a false-negative rate of 27%.14 In other words, patients on an inpatient psychiatry ward who are free to walk around the unit and interact with others are only probably COVID-19 free, not definitively. This fact throws into question the original justification for seclusion—to protect other patients from COVID-19.

Continue to: Support for using seclusion as quarantine

Support for using seclusion as quarantine

Despite these objections, there are clear arguments in favor of using seclusion as a means of quarantine. First, the danger posed by an unidentified COVID-19 infection to the inpatient psychiatric population is not small. As of mid-October 2020, >217,000 Americans had died of COVID-19.6 Psychiatric patients, especially those who are acutely decompensated and hospitalized, have a heightened risk.15 Those with underlying medical issues are more likely to be seriously affected by an infection. Patients with serious mental illness have higher rates of medical comorbidities16 and premature death.17 The risk of a patient contracting and then dying from COVID-19 is elevated in an inpatient psychiatric ward. Even if a test is not 100% sensitive or specific, the balance of probability it provides is sufficient to make an informed decision about transmission risk.

In choosing to seclude a patient who refuses COVID-19 testing, the treating team must weigh one person’s autonomy against the safety of every other individual on the ward. From a purely utilitarian perspective, the lives of the many outweigh the discomfort of one. Addressing this balance, the American Medical Association (AMA) Code of Ethics states “Although physicians’ primary ethical obligation is to their individual patients, they also have a long-recognized public health responsibility. In the context of infectious disease, this may include the use of quarantine and isolation to reduce the transmission of disease and protect the health of the public. In such situations, physicians have a further responsibility to protect their own health to ensure that they remain able to provide care. These responsibilities potentially conflict with patients’ rights of self-determination and with physicians’ duty to advocate for the best interests of individual patients and to provide care in emergencies.”18

The AMA Code of Ethics further mentions that physicians should “support mandatory quarantine and isolation when a patient fails to adhere voluntarily.” Medical evidence supports both quarantine19 and enacting isolation measures for COVID-19–positive hospitalized patients.20 Table 121-24 summarizes the recommendations of major medical societies regarding isolation on hospital units.

Further, public health officials and law enforcement officials do in fact have the authority25 to enforce quarantine and restrict a citizen’s movement outside a hospital setting. Recent cases have illustrated how this has been enforced, particularly with the use of electronic monitoring units and even criminal sanctions.26,27

It is also important to consider that when used as quarantine, seclusion is not an indefinite action. Current recommendations suggest the longest period of time a patient would need to be in seclusion is 14 days. A patient could potentially reduce this period by agreeing to COVID-19 testing and obtaining a negative test result.

Continue to: Enacting inpatient quarantine

Enacting inpatient quarantine

In Mr. T’s case, the resident physician was asked to make a decision regarding seclusion on the spot. Prudent facilities will set policies and educate clinicians before they need to face this conundrum. The following practical considerations may guide implementation of seclusion as a measure of quarantine on an inpatient psychiatric unit:

- given the risk of asymptomatic carriers, all admitted patients should be tested for COVID-19

- patients who refuse a test should be evaluated by the psychiatrist on duty to determine if the patient has the capacity to make this decision

- if a patient demonstrates capacity to refuse and continues to refuse testing, seclusion orders should then be placed

- the facility should create a protocol to ensure consistent application of seclusion orders.

So that they can make an informed decision, patients should be educated about the risks of not undergoing testing. It is important to correctly frame a seclusion decision to the patient. Explain that seclusion is not a punitive measure, but rather a means of respecting the patient’s right to refuse testing while ensuring other patients’ right to be protected from COVID-19 transmission.

It is crucial to not allow psychiatric care to be diminished because a patient is isolated due to COVID-19. Psychiatrists have legal duties to provide care when a patient is admitted to their unit,28-30 and state laws generally outline patients’ rights while they are hospitalized.31 The use of technology can ensure these duties are fulfilled. Patient rounds and group treatment can be conducted through telehealth.10,32 When in-person interaction is required, caretakers should don proper personal protective equipment and interact with the patient as often as they would if the patient were not in seclusion. Table 233-36 summarizes further ethical considerations when implementing quarantine measures on a psychiatry unit.

The contemporary inpatient unit

The ideal design to optimize care and safety is to create designated COVID-19 psychiatric units. Indeed, the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration recommends segregating floors based on infection status where possible.37 This minimizes the risk of transmission to other patients while maintaining the same standards of psychiatric treatment, including milieu and group therapy (which may also require adjustments). Such a unit already has precedent.38 Although designated COVID-19 psychiatric units present clinical and administrative hurdles,39 they may become more commonplace as the number of COVID-19–positive inpatients continues to rise.

Bottom Line

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has created challenges for inpatient psychiatric facilities. Although seclusion is a serious decision and should not be undertaken lightly, there are clear ethical and practical justifications for using it as a means of quarantine for patients who are COVID-19–positive or refuse testing.

Related Resources

- Askew L, Fisher P, Beazley P. What are adult psychiatric inpatients’ experience of seclusion: a systematic review of qualitative studies. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2019; 26(7-8):274-285.

- Komrad MS. Medical ethics in the time of COVID-19. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(7):29-32,46.

1. Knox DK, Holloman GH Jr. Use and avoidance of seclusion and restraint: consensus statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry Project BETA Seclusion and Restraint Workgroup. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13(1):35-40.

2. Sehdev PS. The origin of quarantine. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35(9):1071-1072.

3. 42 CFR § 482.13. Condition of participation: patient’s rights.

4. Colaizzi J. Seclusion & restraint: a historical perspective. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2005;43(2):31-37.

5. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497-506.

6. COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). ArcGIS. Johns Hopkins University. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Accessed October 16, 2020.

7. Guo YR, Cao QD, Hong ZS, et al. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak - an update on the status. Mil Med Res. 2020;7(1):11.

8. Bai Y, Yao L, Wei T, et al. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(14):1406-1407.

9. Li L. Challenges and priorities in responding to COVID-19 in inpatient psychiatry. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(6):624-626.

10. Kim MJ. ‘It was a medical disaster’: the psychiatric ward that saw 100 patients diagnosed with new coronavirus. Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/coronavirus-south-korea-outbreak-hospital-patients-lockdown-a9367486.html. Published March 1, 2020. Accessed July 12, 2020.

11. Petrini C. Ethical considerations for evaluating the issue of physical restraint in psychiatry. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2013;49(3):281-285.

12. Gessen M. Why psychiatric wards are uniquely vulnerable to the coronavirus. https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/why-psychiatric-wards-are-uniquely-vulnerable-to-the-coronavirus. Published April 21, 2020. Accessed July 12, 2020.

13. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith, LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912-920.

14. Woloshin S, Patel N, Kesselheim AS. False negative tests for SARS-CoV-2 infection—challenges and implications. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):e38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2015897.

15. Druss BG. Addressing the COVID-19 pandemic in populations with serious mental illness. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(9):891-892.

16. Rao S, Raney L, Xiong GL. Reducing medical comorbidity and mortality in severe mental illness. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(7):14-20.

17. Plana-Ripoll O, Pedersen CB, Agerbo E, et al. A comprehensive analysis of mortality-related health metrics associated with mental disorders: a nationwide, register-based cohort study. Lancet. 2019;394(10211):1827-1835.

18. American Medical Association. Ethical use of quarantine and isolation. Code of Ethics Opinion 8.4. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/ethical-use-quarantine-isolation. Published November 14, 2016. Accessed July 12, 2020.

19. Nussbaumer-Streit B, Mayr V, Dobrescu AI, et al. Quarantine alone or in combination with other public health measures to control COVID-19: a rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;4(4):CD013574.

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Duration of isolation & precautions for adults. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/duration-isolation.html. Updated August 16, 2020. Accessed August 21, 2020.

21. American College of Gynecologists. Novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2020/03/novel-coronavirus-2019. Updated August 12, 2020. Accessed August 26, 2020.

22. American College of Physicians. COVID-19: an ACP physician’s guide + resources. Chapter 14 of 31. Infection control: advice for physicians. https://assets.acponline.org/coronavirus/scormcontent/#/. Updated September 3, 2020. Accessed September 9, 2020.

23. Infectious Disease Society of America. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines on Infection Prevention in Patients with Suspected or Known COVID-19. https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/covid-19-guideline-infection-prevention/#toc-9-9. Updated April 20, 2020. Accessed August 26, 2020.

24. American College of Emergency Physicians. Joint Statement for Care of Patients with Behavioral Health Emergencies and Suspected or Confirmed COVID-19. https://www.acep.org/corona/covid-19-field-guide/special-populations/behavioral-health-patients/. Updated June 17, 2020. Accessed August 26, 2020.

25. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Quarantine and isolation. Legal authorities. https://www.cdc.gov/quarantine/aboutlawsregulationsquarantineisolation.html. Updated February 24, 2020. Accessed August 31, 2020.

26. Roberts A. Kentucky couple under house arrest after refusing to sign self-quarantine agreement. https://abcnews.go.com/US/kentucky-couple-house-arrest-refusing-sign-quarantine-agreement/story?id=71886479. Published July 20, 2020. Accessed July 24, 2020.

27. Satter R. To keep COVID-19 patients home, some U.S. states weigh house arrest tech. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-quarantine-tech/to-keep-covid-19-patients-home-some-us-states-weigh-house-arrest-tech-idUSKBN22J1U8. Published May 7, 2020. Accessed July 24, 2020.

28. Rouse v Cameron, 373, F2d 451 (DC Cir 1966).

29. Wyatt v Stickney, 325 F Supp 781 (MD Ala 1971).

30. Donaldson v O’Connor, 519, F2d 59 (5th Cir 1975).

31. Ohio Revised Code § 5122.290.

32. Shore JH. Telepsychiatry: videoconferencing in the delivery of psychiatric care. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(3):256-262.

33. Bostick NA, Levine MA, Sade RM. Ethical obligations of physicians participating in public health quarantine and isolation measures. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(1):3-8.

34. Upshur RE. Principles for the justification of public health intervention. Can J Public Health. 2002;93(2):101-103.

35. Barbera J, Macintyre A, Gostin L, et al. Large-scale quarantine following biological terrorism in the United States: scientific examination, logistic and legal limits, and possible consequences. JAMA. 2001;286(21):2711-2717.

36. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Doctrine of double effect. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/double-effect/. Revised December 24, 2018. Accessed July 12, 2020.

37. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Covid19: interim considerations for state psychiatric hospitals. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/covid19-interim-considerations-for-state-psychiatric-hospitals.pdf. Updated May 8, 2020. Accessed July 24, 2020.

38. Augenstein TM, Pigeon WR, DiGiovanni SK, et al. Creating a novel inpatient psychiatric unit with integrated medical support for patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med Catalyst. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0249. Published June 22, 2020. Accessed July 12, 2020.

39. Bojdani E, Rajagopalan A, Chen A, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: impact on psychiatric care in the United States. Psychiatry Research. 2020;289:113069. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113069.

1. Knox DK, Holloman GH Jr. Use and avoidance of seclusion and restraint: consensus statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry Project BETA Seclusion and Restraint Workgroup. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13(1):35-40.

2. Sehdev PS. The origin of quarantine. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35(9):1071-1072.

3. 42 CFR § 482.13. Condition of participation: patient’s rights.

4. Colaizzi J. Seclusion & restraint: a historical perspective. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2005;43(2):31-37.

5. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497-506.

6. COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). ArcGIS. Johns Hopkins University. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Accessed October 16, 2020.

7. Guo YR, Cao QD, Hong ZS, et al. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak - an update on the status. Mil Med Res. 2020;7(1):11.

8. Bai Y, Yao L, Wei T, et al. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(14):1406-1407.

9. Li L. Challenges and priorities in responding to COVID-19 in inpatient psychiatry. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(6):624-626.

10. Kim MJ. ‘It was a medical disaster’: the psychiatric ward that saw 100 patients diagnosed with new coronavirus. Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/coronavirus-south-korea-outbreak-hospital-patients-lockdown-a9367486.html. Published March 1, 2020. Accessed July 12, 2020.

11. Petrini C. Ethical considerations for evaluating the issue of physical restraint in psychiatry. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2013;49(3):281-285.

12. Gessen M. Why psychiatric wards are uniquely vulnerable to the coronavirus. https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/why-psychiatric-wards-are-uniquely-vulnerable-to-the-coronavirus. Published April 21, 2020. Accessed July 12, 2020.

13. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith, LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912-920.

14. Woloshin S, Patel N, Kesselheim AS. False negative tests for SARS-CoV-2 infection—challenges and implications. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):e38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2015897.

15. Druss BG. Addressing the COVID-19 pandemic in populations with serious mental illness. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(9):891-892.

16. Rao S, Raney L, Xiong GL. Reducing medical comorbidity and mortality in severe mental illness. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(7):14-20.

17. Plana-Ripoll O, Pedersen CB, Agerbo E, et al. A comprehensive analysis of mortality-related health metrics associated with mental disorders: a nationwide, register-based cohort study. Lancet. 2019;394(10211):1827-1835.

18. American Medical Association. Ethical use of quarantine and isolation. Code of Ethics Opinion 8.4. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/ethical-use-quarantine-isolation. Published November 14, 2016. Accessed July 12, 2020.

19. Nussbaumer-Streit B, Mayr V, Dobrescu AI, et al. Quarantine alone or in combination with other public health measures to control COVID-19: a rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;4(4):CD013574.

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Duration of isolation & precautions for adults. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/duration-isolation.html. Updated August 16, 2020. Accessed August 21, 2020.

21. American College of Gynecologists. Novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2020/03/novel-coronavirus-2019. Updated August 12, 2020. Accessed August 26, 2020.

22. American College of Physicians. COVID-19: an ACP physician’s guide + resources. Chapter 14 of 31. Infection control: advice for physicians. https://assets.acponline.org/coronavirus/scormcontent/#/. Updated September 3, 2020. Accessed September 9, 2020.

23. Infectious Disease Society of America. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines on Infection Prevention in Patients with Suspected or Known COVID-19. https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/covid-19-guideline-infection-prevention/#toc-9-9. Updated April 20, 2020. Accessed August 26, 2020.

24. American College of Emergency Physicians. Joint Statement for Care of Patients with Behavioral Health Emergencies and Suspected or Confirmed COVID-19. https://www.acep.org/corona/covid-19-field-guide/special-populations/behavioral-health-patients/. Updated June 17, 2020. Accessed August 26, 2020.

25. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Quarantine and isolation. Legal authorities. https://www.cdc.gov/quarantine/aboutlawsregulationsquarantineisolation.html. Updated February 24, 2020. Accessed August 31, 2020.

26. Roberts A. Kentucky couple under house arrest after refusing to sign self-quarantine agreement. https://abcnews.go.com/US/kentucky-couple-house-arrest-refusing-sign-quarantine-agreement/story?id=71886479. Published July 20, 2020. Accessed July 24, 2020.

27. Satter R. To keep COVID-19 patients home, some U.S. states weigh house arrest tech. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-quarantine-tech/to-keep-covid-19-patients-home-some-us-states-weigh-house-arrest-tech-idUSKBN22J1U8. Published May 7, 2020. Accessed July 24, 2020.

28. Rouse v Cameron, 373, F2d 451 (DC Cir 1966).

29. Wyatt v Stickney, 325 F Supp 781 (MD Ala 1971).

30. Donaldson v O’Connor, 519, F2d 59 (5th Cir 1975).

31. Ohio Revised Code § 5122.290.

32. Shore JH. Telepsychiatry: videoconferencing in the delivery of psychiatric care. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(3):256-262.

33. Bostick NA, Levine MA, Sade RM. Ethical obligations of physicians participating in public health quarantine and isolation measures. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(1):3-8.

34. Upshur RE. Principles for the justification of public health intervention. Can J Public Health. 2002;93(2):101-103.

35. Barbera J, Macintyre A, Gostin L, et al. Large-scale quarantine following biological terrorism in the United States: scientific examination, logistic and legal limits, and possible consequences. JAMA. 2001;286(21):2711-2717.

36. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Doctrine of double effect. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/double-effect/. Revised December 24, 2018. Accessed July 12, 2020.

37. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Covid19: interim considerations for state psychiatric hospitals. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/covid19-interim-considerations-for-state-psychiatric-hospitals.pdf. Updated May 8, 2020. Accessed July 24, 2020.

38. Augenstein TM, Pigeon WR, DiGiovanni SK, et al. Creating a novel inpatient psychiatric unit with integrated medical support for patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med Catalyst. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0249. Published June 22, 2020. Accessed July 12, 2020.

39. Bojdani E, Rajagopalan A, Chen A, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: impact on psychiatric care in the United States. Psychiatry Research. 2020;289:113069. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113069.