User login

Dana, an adult nurse practitioner, has been working for two years at a large, suburban primary care practice owned by the regional hospital system. She sees too many patients per day, never has enough time to chart properly, and is concerned by the expanding role of the medical assistants. She sees salary postings on social media and feels she is underpaid. She fantasizes about owning her own practice but would settle for making more money. She’s heard that some NPs have profit-sharing, but she’s not exactly sure what that means.

Kelsey, a PA, is looking for his first job out of school. He’s been offered a full-time, salaried position with benefits at an urgent care center, but he doesn’t know if this is a good deal for him or not. The family physicians there make $85,000 more per year than the PAs, although the roles are quite similar.

DOWN TO BUSINESS

The US health care crisis is, fundamentally, a financial crisis; our system is comprised of both for-profit and not-for-profit (NFP) businesses. Every day, NPs and PAs are making decisions that affect their job satisfaction, performance, and retention. Many lack confidence in their ability to make good decisions about their salaries, because they don’t understand the business of health care.1 To survive and thrive, NPs and PAs must understand the basics of the business end.2

So, what qualifies as a business? Any commercial, retail, or professional entity that earns and spends money. It doesn’t matter if it is a for-profit or NFP organization; it can’t survive unless it makes more money than it spends. How that money is earned varies, from selling services and/or goods to receiving grants, income from interest or rentals, or government subsidies.

The major difference between a for-profit and a NFP organization is who controls the money.3 The owners of a for-profit company control the profits, which may be split among the owners or reinvested in the company. A NFP business may use its profits to provide charity care, offset losses of other programs, or invest in capital improvements (eg, new building, equipment). How the profits are to be used is outlined in the business goals or the mission statement of the entity. There are also federal and state regulations for both types of businesses; visit the Internal Revenue Service website for details (www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits; www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed).

HOW YOU GET PAID FOR SERVICES

As a PA or NP, you generate income for your employer regardless of whether you work for a for-profit or NFP business. Your patients are billed for services rendered.

If you work for a fee-for-service or NFP practice with insurance contracts, the bill gets coded and electronically submitted for payment. Each insurer, whether private or government (ie, Medicare or Medicaid), has established what they will reimburse you for that service. The reimbursement rate is part of your contract with that insurer. Rates are determined based on your profession, licensure, geographic locale, type of facility, and the market rate. An insurance representative would be able to tell you your reimbursement rate for the most common procedure codes you use. (Your employer has this information but may or may not share it with you.) Medicare rates can be found online at www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/.

If you work for a direct-pay practice, you collect what you bill directly from the patient, often at the time of the visit. A direct-pay practice does not have insurance contracts and does not bill insurers for patients who have insurance; rather, they provide a billing statement with procedure and diagnostic codes and NPI numbers to the patient, who can submit it directly to their insurer. If the insurer accepts out-of-network providers (those with whom they have no contract), they will reimburse the patient directly.

If you work in a fee-for-service or NFP practice, you may see patients who do not have insurance or who have very high deductibles and pay cash for their services. This does not make it a direct-pay practice. Also, by law, fee-for-service and NFP practices can only have one fee schedule for the entire practice. So, you can’t charge one patient $55 for a flu shot and another patient $25. These practices can offer discounts for cash payments at the time of service, to help reduce the set fees, if they choose.

TALKIN’ ’BOUT YOUR (REVENUE) GENERATION

To know how much you can negotiate for your salary and benefits—your total compensation package (of which benefits is often about 30%)—it is critical to know how much revenue you can generate for your employer.4 How can you figure this out?

If you are already working, you can ask your practice manager for some data. In some practices, this information is readily shared, perhaps as a means to boost productivity and even allow comparison between employees. If your practice manager is not forthcoming, you can collect the relevant information yourself. It may be challenging, but it is vital information to have. You need to know how many patients you see per day (keep a log for a month), what their payment source is (specific insurer or self-pay), and what the reimbursement rates are. Although reimbursement rates are deemed confidential per your insurance contract and therefore can’t be shared, you can find Medicare and Medicaid rates online. You can also call the provider representative from each insurer and ask for your reimbursement rates for your five or so most commonly used codes.

Another consideration is payment received (ie, not just what you charge). Do all patients pay everything they owe? Not always. Understand the difference between what you bill, what is allowed, and what you collect. The percentage of what is not collected is called the uncollectable rate. Factor that in.

Furthermore, how much do you contribute to the organization by testing? Dana works for a primary care clinic within a hospital system. Let’s assume her practice doesn’t offer colonoscopies or mammograms; how many referrals does she make to the hospital system for these tests? While she may not know the hospital’s profit margin on them, she can figure out how many she orders in a year. And what about the PA who works for a surgeon? Does he or she do the post-surgical checks? How much time does that save the surgeon, who can be providing higher revenue–producing services with the time saved? That contributes to the income of the practice, too! These are points you can make to justify your salary.

MIX IT UP

There is another major consideration for computing your financial contribution to the practice: understanding case mix. Let’s say your most common visit is billed as a 99213 and you charge $100 for this visit. You use this code 50 times in a week. Do you collect $100 x 50 or $5,000 per week? If you have a direct-pay practice and you collect all of it, yes, you will. If your practice accepts insurance, the number of patients you see with different insurers is called your case mix.

Let’s look at the impact of case mix on what you generate. Remember, it will take you about the same amount of time and effort to see these patients regardless of their insurer. Ask your practice manager what your case mix is. If he/she is not willing to share this information, you can get an estimate by looking at the demographics of your patient community. How many are older than 65? How many are on public assistance? Community needs assessments will provide you with this data; you can also check the patient’s chart or ask what insurance they have and add this to your log.

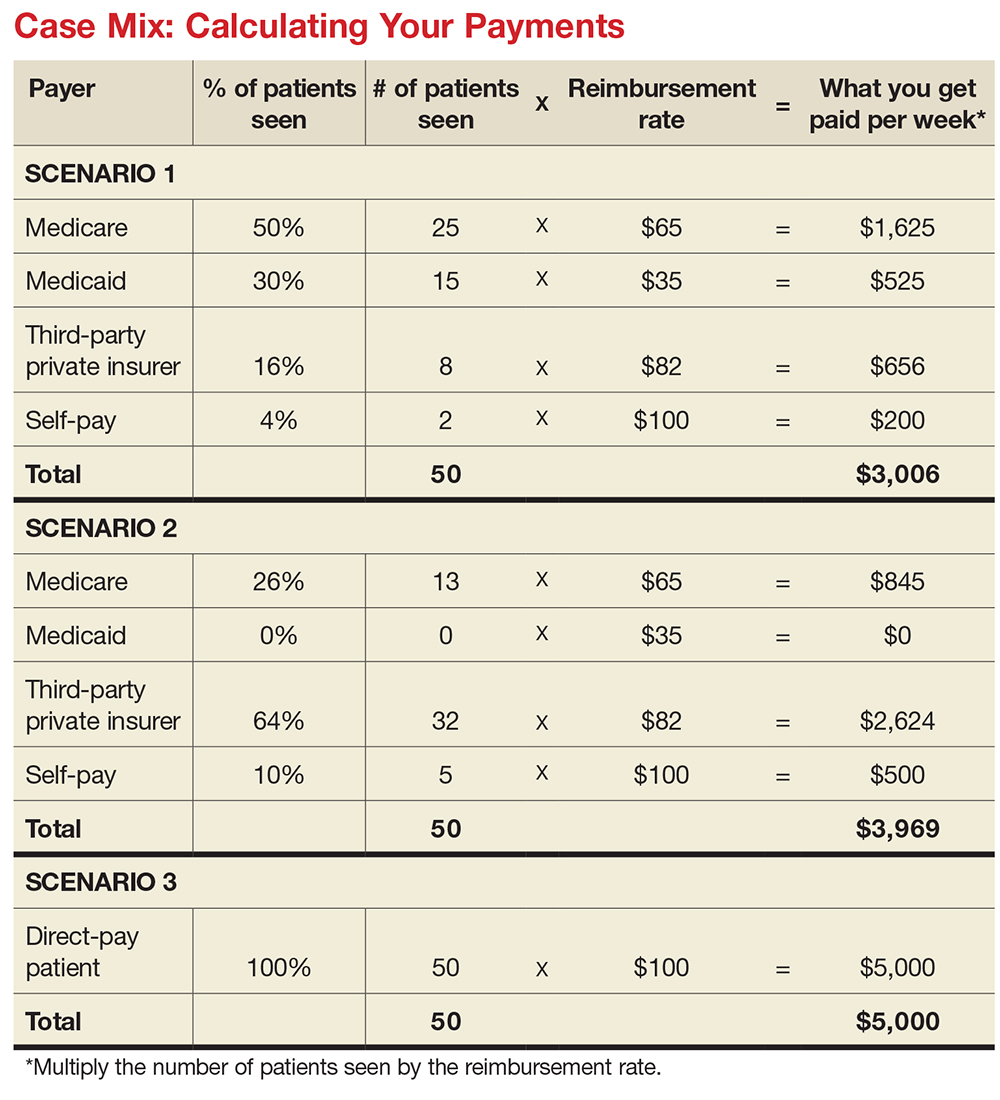

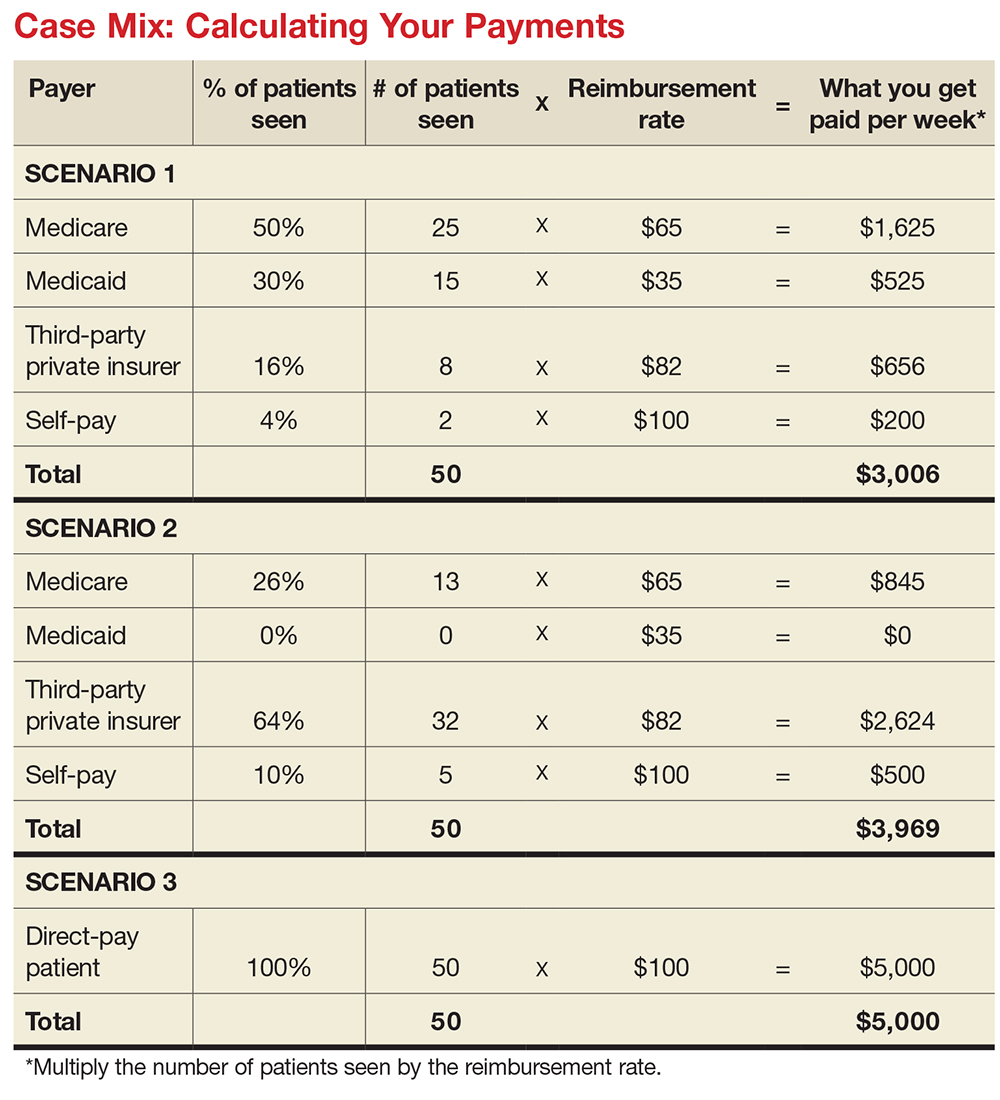

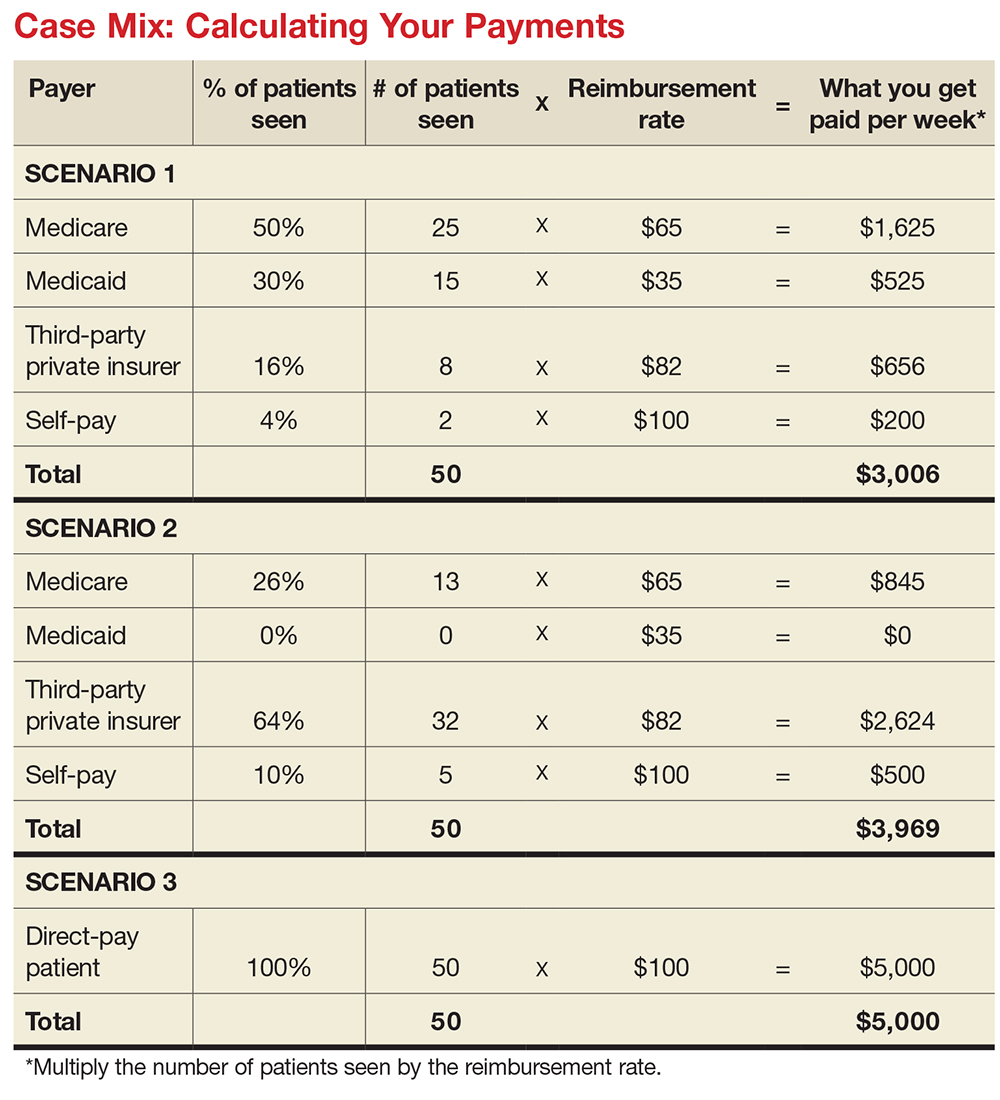

How much will you generate by seeing 50 patients in a week for a 99213 for which you charge $100? Let’s start with sample (not actual) base rates to illustrate the concept: $65 for Medicare, $35 for Medicaid, $82 for third-party private insurance, and $100 for self-pay.

Now let’s explore how case mix impacts revenue, with three different scenarios (see charts). In Scenario 1, 50% of your patients have Medicare, 30% have Medicaid, 16% have third-party private insurance, and 4% pay cash (self-pay). In Scenario 2, 26% have Medicare, 0% have Medicaid, 64% have private insurance, and 10% self-pay. In Scenario 3, your practice is a direct-pay practice with 100% self-payers and a 0% uncollectable rate.

In Scenario 1, with a case mix of 80% of your patient payments from Medicare or Medicaid, you generate $3,006 per week. If you see patients 48 weeks per year, you generate $144,288. In Scenario 2, with a case mix of 74% of your patient payments from private insurance, you generate $3,969 per week. In a year, you generate $190,512. And in Scenario 3, with 100% direct-pay patients, you generate $5,000 per week or $240,000 per year.

This example illustrates how case mix influences health care business, based on the current US reimbursement system. If you work for a practice that serves mostly Medicare and Medicaid patients, you do not command the same salary as an NP or PA who works for a direct-pay practice or one with a majority of privately insured patients.

OVERHEAD, OR IN OVER YOUR HEAD?

Now you have a better understanding of what your worth is to a practice. But what does it cost a practice to employ you? What’s your practice’s overhead?

Overhead includes the cost of processing claims; salaries and benefits; physician collaboration, if needed; rent, utilities, insurance, and depreciation. Overhead rates can range from 20% to 50%—meaning, if you generate $225,000 in revenue, it costs $45,000 to $112,500 to employ you. That leaves $112,500 (with higher overhead) to $180,000 (with lower overhead) for your salary. This revenue generation is an average: Many clinicians generate more than $225,000, while new graduates often generate less.

But in addition to generating more revenue, it can be beneficial to examine what you can do to help decrease the practice overhead. Because the bulk of overhead costs is salary, consider how many full-time-equivalent employees are needed to support you. Some NPs and PAs work with a full-time medical assistant or nurse, while others function very efficiently without one.

While providers like Dana and Kelsey can’t control what their practices pay for rent, utilities, or staffing, they can suggest improvements. Suggestions about scheduling, decreasing no-show rates, and improving recalls, immunization rates, and follow-up visits can all help increase revenue by decreasing day-to-day operating costs.

CONCLUSION

Most NPs and PAs went into their profession to help people—but that altruistic goal doesn’t mean you have to undervalue your own worth. Understanding the basic business of health care can help you negotiate your salary, maximize your income, and create new revenue models for patient care. While this may seem daunting to anyone who went to nursing or medical school, there are great resources to help you educate yourself on the essentials of health care business (see box).

Understanding the infrastructure of the health care system will help NPs and PAs become leaders who can impact health care change. These basic business skills are necessary to ensure fair and full compensation for the roles they play.

1. LaFevers D, Ward-Smith P, Wright W. Essential nurse practitioner business knowledge: an interprofessional perspective. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2015;4:181-184.

2. Buppert C. Nurse Practitioner’s Business and Legal Guide. 6th ed. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning; 2018: 311-324.

3. Fritz J. How is a nonprofit different from a for-profit business? Getting beyond the myths. The Balance. April 3, 2017. www.thebalance.com/how-is-a-nonprofit-different-from-for-profit-business-2502472. Accessed November 20, 2017.

4. Dillon D, Hoyson P. Beginning employment: a guide for the new nurse practitioner. J Nurse Pract. 2014;1:55-59.

Dana, an adult nurse practitioner, has been working for two years at a large, suburban primary care practice owned by the regional hospital system. She sees too many patients per day, never has enough time to chart properly, and is concerned by the expanding role of the medical assistants. She sees salary postings on social media and feels she is underpaid. She fantasizes about owning her own practice but would settle for making more money. She’s heard that some NPs have profit-sharing, but she’s not exactly sure what that means.

Kelsey, a PA, is looking for his first job out of school. He’s been offered a full-time, salaried position with benefits at an urgent care center, but he doesn’t know if this is a good deal for him or not. The family physicians there make $85,000 more per year than the PAs, although the roles are quite similar.

DOWN TO BUSINESS

The US health care crisis is, fundamentally, a financial crisis; our system is comprised of both for-profit and not-for-profit (NFP) businesses. Every day, NPs and PAs are making decisions that affect their job satisfaction, performance, and retention. Many lack confidence in their ability to make good decisions about their salaries, because they don’t understand the business of health care.1 To survive and thrive, NPs and PAs must understand the basics of the business end.2

So, what qualifies as a business? Any commercial, retail, or professional entity that earns and spends money. It doesn’t matter if it is a for-profit or NFP organization; it can’t survive unless it makes more money than it spends. How that money is earned varies, from selling services and/or goods to receiving grants, income from interest or rentals, or government subsidies.

The major difference between a for-profit and a NFP organization is who controls the money.3 The owners of a for-profit company control the profits, which may be split among the owners or reinvested in the company. A NFP business may use its profits to provide charity care, offset losses of other programs, or invest in capital improvements (eg, new building, equipment). How the profits are to be used is outlined in the business goals or the mission statement of the entity. There are also federal and state regulations for both types of businesses; visit the Internal Revenue Service website for details (www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits; www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed).

HOW YOU GET PAID FOR SERVICES

As a PA or NP, you generate income for your employer regardless of whether you work for a for-profit or NFP business. Your patients are billed for services rendered.

If you work for a fee-for-service or NFP practice with insurance contracts, the bill gets coded and electronically submitted for payment. Each insurer, whether private or government (ie, Medicare or Medicaid), has established what they will reimburse you for that service. The reimbursement rate is part of your contract with that insurer. Rates are determined based on your profession, licensure, geographic locale, type of facility, and the market rate. An insurance representative would be able to tell you your reimbursement rate for the most common procedure codes you use. (Your employer has this information but may or may not share it with you.) Medicare rates can be found online at www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/.

If you work for a direct-pay practice, you collect what you bill directly from the patient, often at the time of the visit. A direct-pay practice does not have insurance contracts and does not bill insurers for patients who have insurance; rather, they provide a billing statement with procedure and diagnostic codes and NPI numbers to the patient, who can submit it directly to their insurer. If the insurer accepts out-of-network providers (those with whom they have no contract), they will reimburse the patient directly.

If you work in a fee-for-service or NFP practice, you may see patients who do not have insurance or who have very high deductibles and pay cash for their services. This does not make it a direct-pay practice. Also, by law, fee-for-service and NFP practices can only have one fee schedule for the entire practice. So, you can’t charge one patient $55 for a flu shot and another patient $25. These practices can offer discounts for cash payments at the time of service, to help reduce the set fees, if they choose.

TALKIN’ ’BOUT YOUR (REVENUE) GENERATION

To know how much you can negotiate for your salary and benefits—your total compensation package (of which benefits is often about 30%)—it is critical to know how much revenue you can generate for your employer.4 How can you figure this out?

If you are already working, you can ask your practice manager for some data. In some practices, this information is readily shared, perhaps as a means to boost productivity and even allow comparison between employees. If your practice manager is not forthcoming, you can collect the relevant information yourself. It may be challenging, but it is vital information to have. You need to know how many patients you see per day (keep a log for a month), what their payment source is (specific insurer or self-pay), and what the reimbursement rates are. Although reimbursement rates are deemed confidential per your insurance contract and therefore can’t be shared, you can find Medicare and Medicaid rates online. You can also call the provider representative from each insurer and ask for your reimbursement rates for your five or so most commonly used codes.

Another consideration is payment received (ie, not just what you charge). Do all patients pay everything they owe? Not always. Understand the difference between what you bill, what is allowed, and what you collect. The percentage of what is not collected is called the uncollectable rate. Factor that in.

Furthermore, how much do you contribute to the organization by testing? Dana works for a primary care clinic within a hospital system. Let’s assume her practice doesn’t offer colonoscopies or mammograms; how many referrals does she make to the hospital system for these tests? While she may not know the hospital’s profit margin on them, she can figure out how many she orders in a year. And what about the PA who works for a surgeon? Does he or she do the post-surgical checks? How much time does that save the surgeon, who can be providing higher revenue–producing services with the time saved? That contributes to the income of the practice, too! These are points you can make to justify your salary.

MIX IT UP

There is another major consideration for computing your financial contribution to the practice: understanding case mix. Let’s say your most common visit is billed as a 99213 and you charge $100 for this visit. You use this code 50 times in a week. Do you collect $100 x 50 or $5,000 per week? If you have a direct-pay practice and you collect all of it, yes, you will. If your practice accepts insurance, the number of patients you see with different insurers is called your case mix.

Let’s look at the impact of case mix on what you generate. Remember, it will take you about the same amount of time and effort to see these patients regardless of their insurer. Ask your practice manager what your case mix is. If he/she is not willing to share this information, you can get an estimate by looking at the demographics of your patient community. How many are older than 65? How many are on public assistance? Community needs assessments will provide you with this data; you can also check the patient’s chart or ask what insurance they have and add this to your log.

How much will you generate by seeing 50 patients in a week for a 99213 for which you charge $100? Let’s start with sample (not actual) base rates to illustrate the concept: $65 for Medicare, $35 for Medicaid, $82 for third-party private insurance, and $100 for self-pay.

Now let’s explore how case mix impacts revenue, with three different scenarios (see charts). In Scenario 1, 50% of your patients have Medicare, 30% have Medicaid, 16% have third-party private insurance, and 4% pay cash (self-pay). In Scenario 2, 26% have Medicare, 0% have Medicaid, 64% have private insurance, and 10% self-pay. In Scenario 3, your practice is a direct-pay practice with 100% self-payers and a 0% uncollectable rate.

In Scenario 1, with a case mix of 80% of your patient payments from Medicare or Medicaid, you generate $3,006 per week. If you see patients 48 weeks per year, you generate $144,288. In Scenario 2, with a case mix of 74% of your patient payments from private insurance, you generate $3,969 per week. In a year, you generate $190,512. And in Scenario 3, with 100% direct-pay patients, you generate $5,000 per week or $240,000 per year.

This example illustrates how case mix influences health care business, based on the current US reimbursement system. If you work for a practice that serves mostly Medicare and Medicaid patients, you do not command the same salary as an NP or PA who works for a direct-pay practice or one with a majority of privately insured patients.

OVERHEAD, OR IN OVER YOUR HEAD?

Now you have a better understanding of what your worth is to a practice. But what does it cost a practice to employ you? What’s your practice’s overhead?

Overhead includes the cost of processing claims; salaries and benefits; physician collaboration, if needed; rent, utilities, insurance, and depreciation. Overhead rates can range from 20% to 50%—meaning, if you generate $225,000 in revenue, it costs $45,000 to $112,500 to employ you. That leaves $112,500 (with higher overhead) to $180,000 (with lower overhead) for your salary. This revenue generation is an average: Many clinicians generate more than $225,000, while new graduates often generate less.

But in addition to generating more revenue, it can be beneficial to examine what you can do to help decrease the practice overhead. Because the bulk of overhead costs is salary, consider how many full-time-equivalent employees are needed to support you. Some NPs and PAs work with a full-time medical assistant or nurse, while others function very efficiently without one.

While providers like Dana and Kelsey can’t control what their practices pay for rent, utilities, or staffing, they can suggest improvements. Suggestions about scheduling, decreasing no-show rates, and improving recalls, immunization rates, and follow-up visits can all help increase revenue by decreasing day-to-day operating costs.

CONCLUSION

Most NPs and PAs went into their profession to help people—but that altruistic goal doesn’t mean you have to undervalue your own worth. Understanding the basic business of health care can help you negotiate your salary, maximize your income, and create new revenue models for patient care. While this may seem daunting to anyone who went to nursing or medical school, there are great resources to help you educate yourself on the essentials of health care business (see box).

Understanding the infrastructure of the health care system will help NPs and PAs become leaders who can impact health care change. These basic business skills are necessary to ensure fair and full compensation for the roles they play.

Dana, an adult nurse practitioner, has been working for two years at a large, suburban primary care practice owned by the regional hospital system. She sees too many patients per day, never has enough time to chart properly, and is concerned by the expanding role of the medical assistants. She sees salary postings on social media and feels she is underpaid. She fantasizes about owning her own practice but would settle for making more money. She’s heard that some NPs have profit-sharing, but she’s not exactly sure what that means.

Kelsey, a PA, is looking for his first job out of school. He’s been offered a full-time, salaried position with benefits at an urgent care center, but he doesn’t know if this is a good deal for him or not. The family physicians there make $85,000 more per year than the PAs, although the roles are quite similar.

DOWN TO BUSINESS

The US health care crisis is, fundamentally, a financial crisis; our system is comprised of both for-profit and not-for-profit (NFP) businesses. Every day, NPs and PAs are making decisions that affect their job satisfaction, performance, and retention. Many lack confidence in their ability to make good decisions about their salaries, because they don’t understand the business of health care.1 To survive and thrive, NPs and PAs must understand the basics of the business end.2

So, what qualifies as a business? Any commercial, retail, or professional entity that earns and spends money. It doesn’t matter if it is a for-profit or NFP organization; it can’t survive unless it makes more money than it spends. How that money is earned varies, from selling services and/or goods to receiving grants, income from interest or rentals, or government subsidies.

The major difference between a for-profit and a NFP organization is who controls the money.3 The owners of a for-profit company control the profits, which may be split among the owners or reinvested in the company. A NFP business may use its profits to provide charity care, offset losses of other programs, or invest in capital improvements (eg, new building, equipment). How the profits are to be used is outlined in the business goals or the mission statement of the entity. There are also federal and state regulations for both types of businesses; visit the Internal Revenue Service website for details (www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits; www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed).

HOW YOU GET PAID FOR SERVICES

As a PA or NP, you generate income for your employer regardless of whether you work for a for-profit or NFP business. Your patients are billed for services rendered.

If you work for a fee-for-service or NFP practice with insurance contracts, the bill gets coded and electronically submitted for payment. Each insurer, whether private or government (ie, Medicare or Medicaid), has established what they will reimburse you for that service. The reimbursement rate is part of your contract with that insurer. Rates are determined based on your profession, licensure, geographic locale, type of facility, and the market rate. An insurance representative would be able to tell you your reimbursement rate for the most common procedure codes you use. (Your employer has this information but may or may not share it with you.) Medicare rates can be found online at www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/.

If you work for a direct-pay practice, you collect what you bill directly from the patient, often at the time of the visit. A direct-pay practice does not have insurance contracts and does not bill insurers for patients who have insurance; rather, they provide a billing statement with procedure and diagnostic codes and NPI numbers to the patient, who can submit it directly to their insurer. If the insurer accepts out-of-network providers (those with whom they have no contract), they will reimburse the patient directly.

If you work in a fee-for-service or NFP practice, you may see patients who do not have insurance or who have very high deductibles and pay cash for their services. This does not make it a direct-pay practice. Also, by law, fee-for-service and NFP practices can only have one fee schedule for the entire practice. So, you can’t charge one patient $55 for a flu shot and another patient $25. These practices can offer discounts for cash payments at the time of service, to help reduce the set fees, if they choose.

TALKIN’ ’BOUT YOUR (REVENUE) GENERATION

To know how much you can negotiate for your salary and benefits—your total compensation package (of which benefits is often about 30%)—it is critical to know how much revenue you can generate for your employer.4 How can you figure this out?

If you are already working, you can ask your practice manager for some data. In some practices, this information is readily shared, perhaps as a means to boost productivity and even allow comparison between employees. If your practice manager is not forthcoming, you can collect the relevant information yourself. It may be challenging, but it is vital information to have. You need to know how many patients you see per day (keep a log for a month), what their payment source is (specific insurer or self-pay), and what the reimbursement rates are. Although reimbursement rates are deemed confidential per your insurance contract and therefore can’t be shared, you can find Medicare and Medicaid rates online. You can also call the provider representative from each insurer and ask for your reimbursement rates for your five or so most commonly used codes.

Another consideration is payment received (ie, not just what you charge). Do all patients pay everything they owe? Not always. Understand the difference between what you bill, what is allowed, and what you collect. The percentage of what is not collected is called the uncollectable rate. Factor that in.

Furthermore, how much do you contribute to the organization by testing? Dana works for a primary care clinic within a hospital system. Let’s assume her practice doesn’t offer colonoscopies or mammograms; how many referrals does she make to the hospital system for these tests? While she may not know the hospital’s profit margin on them, she can figure out how many she orders in a year. And what about the PA who works for a surgeon? Does he or she do the post-surgical checks? How much time does that save the surgeon, who can be providing higher revenue–producing services with the time saved? That contributes to the income of the practice, too! These are points you can make to justify your salary.

MIX IT UP

There is another major consideration for computing your financial contribution to the practice: understanding case mix. Let’s say your most common visit is billed as a 99213 and you charge $100 for this visit. You use this code 50 times in a week. Do you collect $100 x 50 or $5,000 per week? If you have a direct-pay practice and you collect all of it, yes, you will. If your practice accepts insurance, the number of patients you see with different insurers is called your case mix.

Let’s look at the impact of case mix on what you generate. Remember, it will take you about the same amount of time and effort to see these patients regardless of their insurer. Ask your practice manager what your case mix is. If he/she is not willing to share this information, you can get an estimate by looking at the demographics of your patient community. How many are older than 65? How many are on public assistance? Community needs assessments will provide you with this data; you can also check the patient’s chart or ask what insurance they have and add this to your log.

How much will you generate by seeing 50 patients in a week for a 99213 for which you charge $100? Let’s start with sample (not actual) base rates to illustrate the concept: $65 for Medicare, $35 for Medicaid, $82 for third-party private insurance, and $100 for self-pay.

Now let’s explore how case mix impacts revenue, with three different scenarios (see charts). In Scenario 1, 50% of your patients have Medicare, 30% have Medicaid, 16% have third-party private insurance, and 4% pay cash (self-pay). In Scenario 2, 26% have Medicare, 0% have Medicaid, 64% have private insurance, and 10% self-pay. In Scenario 3, your practice is a direct-pay practice with 100% self-payers and a 0% uncollectable rate.

In Scenario 1, with a case mix of 80% of your patient payments from Medicare or Medicaid, you generate $3,006 per week. If you see patients 48 weeks per year, you generate $144,288. In Scenario 2, with a case mix of 74% of your patient payments from private insurance, you generate $3,969 per week. In a year, you generate $190,512. And in Scenario 3, with 100% direct-pay patients, you generate $5,000 per week or $240,000 per year.

This example illustrates how case mix influences health care business, based on the current US reimbursement system. If you work for a practice that serves mostly Medicare and Medicaid patients, you do not command the same salary as an NP or PA who works for a direct-pay practice or one with a majority of privately insured patients.

OVERHEAD, OR IN OVER YOUR HEAD?

Now you have a better understanding of what your worth is to a practice. But what does it cost a practice to employ you? What’s your practice’s overhead?

Overhead includes the cost of processing claims; salaries and benefits; physician collaboration, if needed; rent, utilities, insurance, and depreciation. Overhead rates can range from 20% to 50%—meaning, if you generate $225,000 in revenue, it costs $45,000 to $112,500 to employ you. That leaves $112,500 (with higher overhead) to $180,000 (with lower overhead) for your salary. This revenue generation is an average: Many clinicians generate more than $225,000, while new graduates often generate less.

But in addition to generating more revenue, it can be beneficial to examine what you can do to help decrease the practice overhead. Because the bulk of overhead costs is salary, consider how many full-time-equivalent employees are needed to support you. Some NPs and PAs work with a full-time medical assistant or nurse, while others function very efficiently without one.

While providers like Dana and Kelsey can’t control what their practices pay for rent, utilities, or staffing, they can suggest improvements. Suggestions about scheduling, decreasing no-show rates, and improving recalls, immunization rates, and follow-up visits can all help increase revenue by decreasing day-to-day operating costs.

CONCLUSION

Most NPs and PAs went into their profession to help people—but that altruistic goal doesn’t mean you have to undervalue your own worth. Understanding the basic business of health care can help you negotiate your salary, maximize your income, and create new revenue models for patient care. While this may seem daunting to anyone who went to nursing or medical school, there are great resources to help you educate yourself on the essentials of health care business (see box).

Understanding the infrastructure of the health care system will help NPs and PAs become leaders who can impact health care change. These basic business skills are necessary to ensure fair and full compensation for the roles they play.

1. LaFevers D, Ward-Smith P, Wright W. Essential nurse practitioner business knowledge: an interprofessional perspective. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2015;4:181-184.

2. Buppert C. Nurse Practitioner’s Business and Legal Guide. 6th ed. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning; 2018: 311-324.

3. Fritz J. How is a nonprofit different from a for-profit business? Getting beyond the myths. The Balance. April 3, 2017. www.thebalance.com/how-is-a-nonprofit-different-from-for-profit-business-2502472. Accessed November 20, 2017.

4. Dillon D, Hoyson P. Beginning employment: a guide for the new nurse practitioner. J Nurse Pract. 2014;1:55-59.

1. LaFevers D, Ward-Smith P, Wright W. Essential nurse practitioner business knowledge: an interprofessional perspective. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2015;4:181-184.

2. Buppert C. Nurse Practitioner’s Business and Legal Guide. 6th ed. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning; 2018: 311-324.

3. Fritz J. How is a nonprofit different from a for-profit business? Getting beyond the myths. The Balance. April 3, 2017. www.thebalance.com/how-is-a-nonprofit-different-from-for-profit-business-2502472. Accessed November 20, 2017.

4. Dillon D, Hoyson P. Beginning employment: a guide for the new nurse practitioner. J Nurse Pract. 2014;1:55-59.