User login

A handful of papers published in the past few years have looked at different aspects of the current malpractice situation and have yielded some revelations (see page 775 in this issue) or data banks working on safety issues.

- Though it does a reasonable job at separating valid from invalid claims and compensating them accordingly, it often takes a tremendously long time to accomplish this and still has a 10% to 16% rate of false positive (payment with no error) and false negative (no payment with error) outcomes.

- The system is not overwhelmed with frivolous claims. Still, it costs a lot of money to manage, and less than half of this money goes to claimants.

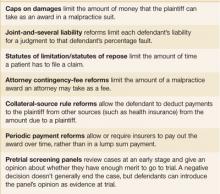

- Hard caps on total damages or noneconomic damages, unlike other state tort reforms (Figure), appear to reduce claims payments, physician premiums, and total health costs,7 while increasing physician supply.

- Defensive medicine exists, though putting a valid dollar amount on its costs is difficult.

- Anecdotal evidence suggests that physicians are leaving practice or limiting their practice (eg, family physicians discontinuing deliveries) as a result of malpractice costs.

FIGURE

Tort reforms commonly adopted by states

AMA’s proposal for change

Malpractice reform has been at or near the top of the AMA’s political agenda for the past 4 or 5 years, with strong lobbying efforts at the national level as well as support for state chapter efforts. The AMA’s proposal is based on California’s liability reform law known as MICRA that was passed over 30 years ago and has been associated with significantly lower premium growth since then compared with the rest of the US.8 Key provisions:

- Unlimited economic damages (medical expenses, future earnings)

- Limits on noneconomic damages (pain and suffering)

- Punitive damages, if available, up to $250,000 or 2 times economic damages, whichever is greater

- Allocation of damage awards in proportion to fault

- Sliding scale for attorney contingency fees.

Dubious premises. The AMA literature on malpractice includes valid information on the costs of the tort system, the rise in claims payouts, and effects on physician premiums. But it also suggests that meritless lawsuits are increasing. This is untrue. And its implication that physicians are increasingly leaving practice is anecdotal. There is no good research on the extent of this problem.8

Too narrow a focus. More important, the AMA plan is focused on physician premium costs while ignoring the unfairness of the system (eg, time to resolve claims, lack of payment for many patients with legitimate claims) and the vast number of medical errors for which claims are never filed.

The MEDIC proposal

Senators Hillary Clinton (D-NY) and Barack Obama (D-IL) have proposed federal legislation to address the malpractice crisis. Their bill would create an Office of Patient Safety in the Department of Health and Human Services, and would establish the National Medical Error Disclosure and Compensation (MEDIC) program within that office.9

Apologies would not be actionable in court. The MEDIC program would provide grants to physicians, hospitals, and health systems for the creation of programs to disclose medical errors to patients and negotiate fair compensation. The law would preserve confidentiality so that any apology offered by a health care provider as part of those negotiations would be kept confidential and could not be used in a trial. Any savings achieved from lower administrative and legal costs would be used to reduce physician malpractice premiums and toward patient safety initiatives.

Federal mandating of caps unlikely, however. At the federal level, Democrats have firmly opposed mandating caps on malpractice claims settlements. They argue that caps are unfair to patients who have been victims of medical errors. Others say this opposition reflects financial contributions from trial lawyers. It seems time to get past this conflict. Without dramatic changes in the composition of the Senate, which seems unlikely, there is little or no chance that caps will pass at the national level. At the same time, physician groups have been successful at achieving caps in a number of states (total of 26 at last count).

Signs this program could succeed. The MEDIC proposal is an attempt to find another way out of the malpractice impasse in the Senate by linking the patient safety and tort reform issues. It is primarily based on a growing movement to have physicians more directly acknowledge medical errors to patients,10 and in some cases, link these apologies to immediate financial negotiations to settle any potential claim of injury. The University of Michigan is the best known academic institution pursuing these strategies, and they report a significant decrease in the number of claims and annual litigation costs. The Lexington, Kentucky, VA Hospital has a similar program that has reduced liability costs compared with other VA hospitals.

The MEDIC proposal is attractive in its attempt to tie doctor-patient communication, patient safety, and liability together. And the anecdotal reports of success with isolated programs of its type are encouraging. It also moves the argument at a national level away from a fight about caps, which puts many physicians in the uncomfortable position of opposing Democrats who support many of their other positions—eg, Title VII funding, preservation of the traditional Medicare program, expansion of the Medicare Part D program, and better funding of public health programs. Nonetheless, there is a big row to hoe in making physicians more comfortable with acknowledging their errors, convincing them this would not be held against them in court, and assuring both physicians and hospitals that such efforts will actually lead to lower malpractice costs.

Thorpe analyzed data from 1995–2001 collected by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners to see the relationship between state tort reforms and premium levels. Premiums in states with caps on awards were 17% lower than states without caps. There was no association between premium levels and other reforms, such as caps on attorney fees or collateral offset rules (decreasing awards by the amount the plaintiff receives from other sources). Some association was noted between decreased competition among insurers and higher premiums.1

Rodwin et al used data from AMA surveys of self-employed physicians (physicians in groups or solo practice who are not employees) from 1970 to 2000. They found that while premiums increased from 1970 to 1986 and from 1996 to 2000, they had only a small effect on physician income. Premiums made up a small percentage of total practice costs and had a negligible effect on practice income, arguing against a malpractice crisis. However, this study lacked more recent data on premium increases and practice expenses and did not take into account differences among states that might be due to tort reforms such as the institution of caps on awards.2

Studdert et al reviewed 1452 closed claims in 4 categories (obstetrics, surgery, missed or delayed diagnosis, and medication) from 5 liability insurers representing 4 regions of the US, and used objective criteria and independent reviewers to classify the merits of the claims. They found that 3% of the claims had no verifiable medical injury and 37% did not involve errors. About 73% of the claims not associated with errors or injuries resulted in no compensation, while 73% of those with errors did result in compensation. Further payment for claims not involving errors were lower than those that did involve errors. Looked at another way, of the 1452 claims reviewed, about 10% received payment but had no identifiable error, while about 17% had an identifiable error but no payment was made.3

This study demonstrated that: 1) the cost of defending claims involving no error was substantial but still only amounted to about 13% of direct system costs, meaning that contesting and paying for claims caused by errors accounts for most of the costs of the liability system, and 2) the malpractice system works reasonably well at separating claims without merit from those with merit.

Nonetheless, the study also demonstrated the unfairness of a system in which 1 in 6 valid claims received no payment (this in addition to the vast number of negligent injuries that never even lead to a claim as discussed in the 1999 IOM report). Then there is the frustration with a system wherein the average time between injury and claim resolution is 5 years and 54% of the payments are absorbed by defense costs and contingency fees. That 80% of expenses were incurred in resolving claims with errors suggests that steps to decrease frivolous litigation (claims without merit) will not lead to substantial savings and that steps to streamlining the system of handling claims will be more useful.

Blake et al looked at state-specific data from the National Practitioner Data Bank, which collects reports of all malpractice payments in the US on behalf of physicians, dentists, and nurses. They looked at the relationship between payments, physician premiums, and various state tort reforms. They found that mean payments were 26% lower in states with total damage caps ($196,000 vs $265,000) and 22% less in states with noneconomic (pain and suffering) damage caps ($212,000 vs $279,000). In addition, total damage caps were associated with lower mean annual premiums and hard, but not soft (caps with exceptions) noneconomic caps were associated with premium reductions. No other state tort reforms measured showed a significant association with payments or premiums.4

Studdert et al surveyed Pennsylvania physicians in high-risk specialties (obstetrics/gynecology, ortho, ER, surgery, neurosurgery) to ascertain self-report of defensive medicine practice. Almost all respondents reported practicing defensive medicine, the most common form (92%) being unnecessary ordering of tests and imaging studies and referring for consultation. In addition, 42% said they had restricted their practice by either decreasing the performance of more risky procedures (eg, trauma surgery) or avoiding complex cases or patients perceived as more likely to sue. Defensive medicine was highly correlated with physicians’ lack of confidence in their liability insurance or its cost.5

Kessler et al looked at physician supply from 1985–2001 and its correlates to state tort reforms during that time. Three years after States that adopted direct reforms (mainly caps on damage awards) showed an average physician growth rate within 3 years that was 3.3% greater than states not adopting such reforms. The authors controlled for a variety of factors that can influence physician supply including population growth and other state-level characteristics.6

Common Good proposal

Another approach is advocated by Common Good, a bipartisan legal reform coalition. This organization has funding from the RWJ Foundation to work with researchers from the Harvard School of Public Health to investigate the creation of special health courts to hear malpractice cases.11 Their ideas are incorporated into the Fair and Reliable Medical Justice Act introduced as S.1337 by Senators Mike Enzi (R-WY) Max Baucus (D-MT).11

How it would work. Health courts would have full-time judges, neutral medical experts, faster proceedings with legal fees held to 20%, and rulings that could be appealed to a new Medical Appellate Court. Like other administrative courts that handle tax disputes, workmen’s comp, and vaccine injury, there would be no juries. Judges would issue written rulings and establish legal precedents. Once a mistake was verified, recovery would be automatic. Patients would be reimbursed for all their medical expenses and lost income plus a fixed sum that would be determined from an expert derived schedule addressing specific types of injuries.

Strengths and weaknesses. This proposal has the support of a wide array of national medical and legal leaders but not any medical associations. It attempts to address some of the most egregious parts of the current system—the time it takes to get claims resolved, the many errors that go uncompensated, and the diversion of so many dollars to overhead and legal fees rather than to patients. On the other hand, the plan does not provide firm caps, which may make the AMA and other professional associations skeptical. And the proposed health courts would rely on select medical experts and judges, a system likely to be strongly opposed by trial lawyers and some consumer groups. It also does not directly address the prevention of patient errors.

Those who fail to learn from history…

The current malpractice crisis may be abating, leaving physicians with higher malpractice premiums but some state tort reforms. History, however, suggests that the insurance cycle will eventually lead to another crisis. There may be a window of opportunity now to come up with a completely different system to address the goals and problems with our current system, but it is likely to be a small window. Capitalizing on it will require a willingness for both sides in the current stand-off to get past their own self-interests in order to come up with something better for all.

CORRESPONDENCE

Eric A. Henley, MD, MPH, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Illinois College of Medicine at Rockford, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107-1897. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Thorpe K. The Medical malpractice “crisis”: Recent trends and the impact of state tort reforms. Health Affairs 2004 January 21;web-only.

2. Rodwin M, Chang H, Clausen J. Malpractice premiums and physicians’ income: Perceptions of a crisis conflict with empirical evidence. Health Affairs 2006;525:750-758.

3. Studdert D, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2024-2033.

4. Guirguis-Blake J, Fryer GE, Phillips RL, Jr, Szabat R, Green LA. The US medical liability system: Evidence for legislative reform. Ann Fam Med 2006;4:240-246.

5. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA 2005;293:2609-2617.

6. Kessler DP, Sage WM, Becker DJ, et al. Impact of malpractice reforms on the supply of physician services. JAMA 2005;293:2618-2625.

7. Hellinger F, Encinosa W. The impact of state laws limiting malpractice damage awards on health care expenditures. AJPH 2006;96:1375-1381.

8. American Medical Association. Medical liability talking points. Available at: www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/399/mlr_fastfacts.pdf. Accessed on August 15, 2006.

9. Clinton HR, Obama B. Making patient safety the centerpiece of medical liability reform. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2205-2208.

10. O’Reilly K. Harvard adopts a disclosure and apology policy. AMA News, June 12, 2006.

11. Common Good. What are health courts? Available at: cgood.org/f-healthcourtsinfo.html. Accessed on August 15, 2006.

A handful of papers published in the past few years have looked at different aspects of the current malpractice situation and have yielded some revelations (see page 775 in this issue) or data banks working on safety issues.

- Though it does a reasonable job at separating valid from invalid claims and compensating them accordingly, it often takes a tremendously long time to accomplish this and still has a 10% to 16% rate of false positive (payment with no error) and false negative (no payment with error) outcomes.

- The system is not overwhelmed with frivolous claims. Still, it costs a lot of money to manage, and less than half of this money goes to claimants.

- Hard caps on total damages or noneconomic damages, unlike other state tort reforms (Figure), appear to reduce claims payments, physician premiums, and total health costs,7 while increasing physician supply.

- Defensive medicine exists, though putting a valid dollar amount on its costs is difficult.

- Anecdotal evidence suggests that physicians are leaving practice or limiting their practice (eg, family physicians discontinuing deliveries) as a result of malpractice costs.

FIGURE

Tort reforms commonly adopted by states

AMA’s proposal for change

Malpractice reform has been at or near the top of the AMA’s political agenda for the past 4 or 5 years, with strong lobbying efforts at the national level as well as support for state chapter efforts. The AMA’s proposal is based on California’s liability reform law known as MICRA that was passed over 30 years ago and has been associated with significantly lower premium growth since then compared with the rest of the US.8 Key provisions:

- Unlimited economic damages (medical expenses, future earnings)

- Limits on noneconomic damages (pain and suffering)

- Punitive damages, if available, up to $250,000 or 2 times economic damages, whichever is greater

- Allocation of damage awards in proportion to fault

- Sliding scale for attorney contingency fees.

Dubious premises. The AMA literature on malpractice includes valid information on the costs of the tort system, the rise in claims payouts, and effects on physician premiums. But it also suggests that meritless lawsuits are increasing. This is untrue. And its implication that physicians are increasingly leaving practice is anecdotal. There is no good research on the extent of this problem.8

Too narrow a focus. More important, the AMA plan is focused on physician premium costs while ignoring the unfairness of the system (eg, time to resolve claims, lack of payment for many patients with legitimate claims) and the vast number of medical errors for which claims are never filed.

The MEDIC proposal

Senators Hillary Clinton (D-NY) and Barack Obama (D-IL) have proposed federal legislation to address the malpractice crisis. Their bill would create an Office of Patient Safety in the Department of Health and Human Services, and would establish the National Medical Error Disclosure and Compensation (MEDIC) program within that office.9

Apologies would not be actionable in court. The MEDIC program would provide grants to physicians, hospitals, and health systems for the creation of programs to disclose medical errors to patients and negotiate fair compensation. The law would preserve confidentiality so that any apology offered by a health care provider as part of those negotiations would be kept confidential and could not be used in a trial. Any savings achieved from lower administrative and legal costs would be used to reduce physician malpractice premiums and toward patient safety initiatives.

Federal mandating of caps unlikely, however. At the federal level, Democrats have firmly opposed mandating caps on malpractice claims settlements. They argue that caps are unfair to patients who have been victims of medical errors. Others say this opposition reflects financial contributions from trial lawyers. It seems time to get past this conflict. Without dramatic changes in the composition of the Senate, which seems unlikely, there is little or no chance that caps will pass at the national level. At the same time, physician groups have been successful at achieving caps in a number of states (total of 26 at last count).

Signs this program could succeed. The MEDIC proposal is an attempt to find another way out of the malpractice impasse in the Senate by linking the patient safety and tort reform issues. It is primarily based on a growing movement to have physicians more directly acknowledge medical errors to patients,10 and in some cases, link these apologies to immediate financial negotiations to settle any potential claim of injury. The University of Michigan is the best known academic institution pursuing these strategies, and they report a significant decrease in the number of claims and annual litigation costs. The Lexington, Kentucky, VA Hospital has a similar program that has reduced liability costs compared with other VA hospitals.

The MEDIC proposal is attractive in its attempt to tie doctor-patient communication, patient safety, and liability together. And the anecdotal reports of success with isolated programs of its type are encouraging. It also moves the argument at a national level away from a fight about caps, which puts many physicians in the uncomfortable position of opposing Democrats who support many of their other positions—eg, Title VII funding, preservation of the traditional Medicare program, expansion of the Medicare Part D program, and better funding of public health programs. Nonetheless, there is a big row to hoe in making physicians more comfortable with acknowledging their errors, convincing them this would not be held against them in court, and assuring both physicians and hospitals that such efforts will actually lead to lower malpractice costs.

Thorpe analyzed data from 1995–2001 collected by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners to see the relationship between state tort reforms and premium levels. Premiums in states with caps on awards were 17% lower than states without caps. There was no association between premium levels and other reforms, such as caps on attorney fees or collateral offset rules (decreasing awards by the amount the plaintiff receives from other sources). Some association was noted between decreased competition among insurers and higher premiums.1

Rodwin et al used data from AMA surveys of self-employed physicians (physicians in groups or solo practice who are not employees) from 1970 to 2000. They found that while premiums increased from 1970 to 1986 and from 1996 to 2000, they had only a small effect on physician income. Premiums made up a small percentage of total practice costs and had a negligible effect on practice income, arguing against a malpractice crisis. However, this study lacked more recent data on premium increases and practice expenses and did not take into account differences among states that might be due to tort reforms such as the institution of caps on awards.2

Studdert et al reviewed 1452 closed claims in 4 categories (obstetrics, surgery, missed or delayed diagnosis, and medication) from 5 liability insurers representing 4 regions of the US, and used objective criteria and independent reviewers to classify the merits of the claims. They found that 3% of the claims had no verifiable medical injury and 37% did not involve errors. About 73% of the claims not associated with errors or injuries resulted in no compensation, while 73% of those with errors did result in compensation. Further payment for claims not involving errors were lower than those that did involve errors. Looked at another way, of the 1452 claims reviewed, about 10% received payment but had no identifiable error, while about 17% had an identifiable error but no payment was made.3

This study demonstrated that: 1) the cost of defending claims involving no error was substantial but still only amounted to about 13% of direct system costs, meaning that contesting and paying for claims caused by errors accounts for most of the costs of the liability system, and 2) the malpractice system works reasonably well at separating claims without merit from those with merit.

Nonetheless, the study also demonstrated the unfairness of a system in which 1 in 6 valid claims received no payment (this in addition to the vast number of negligent injuries that never even lead to a claim as discussed in the 1999 IOM report). Then there is the frustration with a system wherein the average time between injury and claim resolution is 5 years and 54% of the payments are absorbed by defense costs and contingency fees. That 80% of expenses were incurred in resolving claims with errors suggests that steps to decrease frivolous litigation (claims without merit) will not lead to substantial savings and that steps to streamlining the system of handling claims will be more useful.

Blake et al looked at state-specific data from the National Practitioner Data Bank, which collects reports of all malpractice payments in the US on behalf of physicians, dentists, and nurses. They looked at the relationship between payments, physician premiums, and various state tort reforms. They found that mean payments were 26% lower in states with total damage caps ($196,000 vs $265,000) and 22% less in states with noneconomic (pain and suffering) damage caps ($212,000 vs $279,000). In addition, total damage caps were associated with lower mean annual premiums and hard, but not soft (caps with exceptions) noneconomic caps were associated with premium reductions. No other state tort reforms measured showed a significant association with payments or premiums.4

Studdert et al surveyed Pennsylvania physicians in high-risk specialties (obstetrics/gynecology, ortho, ER, surgery, neurosurgery) to ascertain self-report of defensive medicine practice. Almost all respondents reported practicing defensive medicine, the most common form (92%) being unnecessary ordering of tests and imaging studies and referring for consultation. In addition, 42% said they had restricted their practice by either decreasing the performance of more risky procedures (eg, trauma surgery) or avoiding complex cases or patients perceived as more likely to sue. Defensive medicine was highly correlated with physicians’ lack of confidence in their liability insurance or its cost.5

Kessler et al looked at physician supply from 1985–2001 and its correlates to state tort reforms during that time. Three years after States that adopted direct reforms (mainly caps on damage awards) showed an average physician growth rate within 3 years that was 3.3% greater than states not adopting such reforms. The authors controlled for a variety of factors that can influence physician supply including population growth and other state-level characteristics.6

Common Good proposal

Another approach is advocated by Common Good, a bipartisan legal reform coalition. This organization has funding from the RWJ Foundation to work with researchers from the Harvard School of Public Health to investigate the creation of special health courts to hear malpractice cases.11 Their ideas are incorporated into the Fair and Reliable Medical Justice Act introduced as S.1337 by Senators Mike Enzi (R-WY) Max Baucus (D-MT).11

How it would work. Health courts would have full-time judges, neutral medical experts, faster proceedings with legal fees held to 20%, and rulings that could be appealed to a new Medical Appellate Court. Like other administrative courts that handle tax disputes, workmen’s comp, and vaccine injury, there would be no juries. Judges would issue written rulings and establish legal precedents. Once a mistake was verified, recovery would be automatic. Patients would be reimbursed for all their medical expenses and lost income plus a fixed sum that would be determined from an expert derived schedule addressing specific types of injuries.

Strengths and weaknesses. This proposal has the support of a wide array of national medical and legal leaders but not any medical associations. It attempts to address some of the most egregious parts of the current system—the time it takes to get claims resolved, the many errors that go uncompensated, and the diversion of so many dollars to overhead and legal fees rather than to patients. On the other hand, the plan does not provide firm caps, which may make the AMA and other professional associations skeptical. And the proposed health courts would rely on select medical experts and judges, a system likely to be strongly opposed by trial lawyers and some consumer groups. It also does not directly address the prevention of patient errors.

Those who fail to learn from history…

The current malpractice crisis may be abating, leaving physicians with higher malpractice premiums but some state tort reforms. History, however, suggests that the insurance cycle will eventually lead to another crisis. There may be a window of opportunity now to come up with a completely different system to address the goals and problems with our current system, but it is likely to be a small window. Capitalizing on it will require a willingness for both sides in the current stand-off to get past their own self-interests in order to come up with something better for all.

CORRESPONDENCE

Eric A. Henley, MD, MPH, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Illinois College of Medicine at Rockford, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107-1897. E-mail: [email protected]

A handful of papers published in the past few years have looked at different aspects of the current malpractice situation and have yielded some revelations (see page 775 in this issue) or data banks working on safety issues.

- Though it does a reasonable job at separating valid from invalid claims and compensating them accordingly, it often takes a tremendously long time to accomplish this and still has a 10% to 16% rate of false positive (payment with no error) and false negative (no payment with error) outcomes.

- The system is not overwhelmed with frivolous claims. Still, it costs a lot of money to manage, and less than half of this money goes to claimants.

- Hard caps on total damages or noneconomic damages, unlike other state tort reforms (Figure), appear to reduce claims payments, physician premiums, and total health costs,7 while increasing physician supply.

- Defensive medicine exists, though putting a valid dollar amount on its costs is difficult.

- Anecdotal evidence suggests that physicians are leaving practice or limiting their practice (eg, family physicians discontinuing deliveries) as a result of malpractice costs.

FIGURE

Tort reforms commonly adopted by states

AMA’s proposal for change

Malpractice reform has been at or near the top of the AMA’s political agenda for the past 4 or 5 years, with strong lobbying efforts at the national level as well as support for state chapter efforts. The AMA’s proposal is based on California’s liability reform law known as MICRA that was passed over 30 years ago and has been associated with significantly lower premium growth since then compared with the rest of the US.8 Key provisions:

- Unlimited economic damages (medical expenses, future earnings)

- Limits on noneconomic damages (pain and suffering)

- Punitive damages, if available, up to $250,000 or 2 times economic damages, whichever is greater

- Allocation of damage awards in proportion to fault

- Sliding scale for attorney contingency fees.

Dubious premises. The AMA literature on malpractice includes valid information on the costs of the tort system, the rise in claims payouts, and effects on physician premiums. But it also suggests that meritless lawsuits are increasing. This is untrue. And its implication that physicians are increasingly leaving practice is anecdotal. There is no good research on the extent of this problem.8

Too narrow a focus. More important, the AMA plan is focused on physician premium costs while ignoring the unfairness of the system (eg, time to resolve claims, lack of payment for many patients with legitimate claims) and the vast number of medical errors for which claims are never filed.

The MEDIC proposal

Senators Hillary Clinton (D-NY) and Barack Obama (D-IL) have proposed federal legislation to address the malpractice crisis. Their bill would create an Office of Patient Safety in the Department of Health and Human Services, and would establish the National Medical Error Disclosure and Compensation (MEDIC) program within that office.9

Apologies would not be actionable in court. The MEDIC program would provide grants to physicians, hospitals, and health systems for the creation of programs to disclose medical errors to patients and negotiate fair compensation. The law would preserve confidentiality so that any apology offered by a health care provider as part of those negotiations would be kept confidential and could not be used in a trial. Any savings achieved from lower administrative and legal costs would be used to reduce physician malpractice premiums and toward patient safety initiatives.

Federal mandating of caps unlikely, however. At the federal level, Democrats have firmly opposed mandating caps on malpractice claims settlements. They argue that caps are unfair to patients who have been victims of medical errors. Others say this opposition reflects financial contributions from trial lawyers. It seems time to get past this conflict. Without dramatic changes in the composition of the Senate, which seems unlikely, there is little or no chance that caps will pass at the national level. At the same time, physician groups have been successful at achieving caps in a number of states (total of 26 at last count).

Signs this program could succeed. The MEDIC proposal is an attempt to find another way out of the malpractice impasse in the Senate by linking the patient safety and tort reform issues. It is primarily based on a growing movement to have physicians more directly acknowledge medical errors to patients,10 and in some cases, link these apologies to immediate financial negotiations to settle any potential claim of injury. The University of Michigan is the best known academic institution pursuing these strategies, and they report a significant decrease in the number of claims and annual litigation costs. The Lexington, Kentucky, VA Hospital has a similar program that has reduced liability costs compared with other VA hospitals.

The MEDIC proposal is attractive in its attempt to tie doctor-patient communication, patient safety, and liability together. And the anecdotal reports of success with isolated programs of its type are encouraging. It also moves the argument at a national level away from a fight about caps, which puts many physicians in the uncomfortable position of opposing Democrats who support many of their other positions—eg, Title VII funding, preservation of the traditional Medicare program, expansion of the Medicare Part D program, and better funding of public health programs. Nonetheless, there is a big row to hoe in making physicians more comfortable with acknowledging their errors, convincing them this would not be held against them in court, and assuring both physicians and hospitals that such efforts will actually lead to lower malpractice costs.

Thorpe analyzed data from 1995–2001 collected by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners to see the relationship between state tort reforms and premium levels. Premiums in states with caps on awards were 17% lower than states without caps. There was no association between premium levels and other reforms, such as caps on attorney fees or collateral offset rules (decreasing awards by the amount the plaintiff receives from other sources). Some association was noted between decreased competition among insurers and higher premiums.1

Rodwin et al used data from AMA surveys of self-employed physicians (physicians in groups or solo practice who are not employees) from 1970 to 2000. They found that while premiums increased from 1970 to 1986 and from 1996 to 2000, they had only a small effect on physician income. Premiums made up a small percentage of total practice costs and had a negligible effect on practice income, arguing against a malpractice crisis. However, this study lacked more recent data on premium increases and practice expenses and did not take into account differences among states that might be due to tort reforms such as the institution of caps on awards.2

Studdert et al reviewed 1452 closed claims in 4 categories (obstetrics, surgery, missed or delayed diagnosis, and medication) from 5 liability insurers representing 4 regions of the US, and used objective criteria and independent reviewers to classify the merits of the claims. They found that 3% of the claims had no verifiable medical injury and 37% did not involve errors. About 73% of the claims not associated with errors or injuries resulted in no compensation, while 73% of those with errors did result in compensation. Further payment for claims not involving errors were lower than those that did involve errors. Looked at another way, of the 1452 claims reviewed, about 10% received payment but had no identifiable error, while about 17% had an identifiable error but no payment was made.3

This study demonstrated that: 1) the cost of defending claims involving no error was substantial but still only amounted to about 13% of direct system costs, meaning that contesting and paying for claims caused by errors accounts for most of the costs of the liability system, and 2) the malpractice system works reasonably well at separating claims without merit from those with merit.

Nonetheless, the study also demonstrated the unfairness of a system in which 1 in 6 valid claims received no payment (this in addition to the vast number of negligent injuries that never even lead to a claim as discussed in the 1999 IOM report). Then there is the frustration with a system wherein the average time between injury and claim resolution is 5 years and 54% of the payments are absorbed by defense costs and contingency fees. That 80% of expenses were incurred in resolving claims with errors suggests that steps to decrease frivolous litigation (claims without merit) will not lead to substantial savings and that steps to streamlining the system of handling claims will be more useful.

Blake et al looked at state-specific data from the National Practitioner Data Bank, which collects reports of all malpractice payments in the US on behalf of physicians, dentists, and nurses. They looked at the relationship between payments, physician premiums, and various state tort reforms. They found that mean payments were 26% lower in states with total damage caps ($196,000 vs $265,000) and 22% less in states with noneconomic (pain and suffering) damage caps ($212,000 vs $279,000). In addition, total damage caps were associated with lower mean annual premiums and hard, but not soft (caps with exceptions) noneconomic caps were associated with premium reductions. No other state tort reforms measured showed a significant association with payments or premiums.4

Studdert et al surveyed Pennsylvania physicians in high-risk specialties (obstetrics/gynecology, ortho, ER, surgery, neurosurgery) to ascertain self-report of defensive medicine practice. Almost all respondents reported practicing defensive medicine, the most common form (92%) being unnecessary ordering of tests and imaging studies and referring for consultation. In addition, 42% said they had restricted their practice by either decreasing the performance of more risky procedures (eg, trauma surgery) or avoiding complex cases or patients perceived as more likely to sue. Defensive medicine was highly correlated with physicians’ lack of confidence in their liability insurance or its cost.5

Kessler et al looked at physician supply from 1985–2001 and its correlates to state tort reforms during that time. Three years after States that adopted direct reforms (mainly caps on damage awards) showed an average physician growth rate within 3 years that was 3.3% greater than states not adopting such reforms. The authors controlled for a variety of factors that can influence physician supply including population growth and other state-level characteristics.6

Common Good proposal

Another approach is advocated by Common Good, a bipartisan legal reform coalition. This organization has funding from the RWJ Foundation to work with researchers from the Harvard School of Public Health to investigate the creation of special health courts to hear malpractice cases.11 Their ideas are incorporated into the Fair and Reliable Medical Justice Act introduced as S.1337 by Senators Mike Enzi (R-WY) Max Baucus (D-MT).11

How it would work. Health courts would have full-time judges, neutral medical experts, faster proceedings with legal fees held to 20%, and rulings that could be appealed to a new Medical Appellate Court. Like other administrative courts that handle tax disputes, workmen’s comp, and vaccine injury, there would be no juries. Judges would issue written rulings and establish legal precedents. Once a mistake was verified, recovery would be automatic. Patients would be reimbursed for all their medical expenses and lost income plus a fixed sum that would be determined from an expert derived schedule addressing specific types of injuries.

Strengths and weaknesses. This proposal has the support of a wide array of national medical and legal leaders but not any medical associations. It attempts to address some of the most egregious parts of the current system—the time it takes to get claims resolved, the many errors that go uncompensated, and the diversion of so many dollars to overhead and legal fees rather than to patients. On the other hand, the plan does not provide firm caps, which may make the AMA and other professional associations skeptical. And the proposed health courts would rely on select medical experts and judges, a system likely to be strongly opposed by trial lawyers and some consumer groups. It also does not directly address the prevention of patient errors.

Those who fail to learn from history…

The current malpractice crisis may be abating, leaving physicians with higher malpractice premiums but some state tort reforms. History, however, suggests that the insurance cycle will eventually lead to another crisis. There may be a window of opportunity now to come up with a completely different system to address the goals and problems with our current system, but it is likely to be a small window. Capitalizing on it will require a willingness for both sides in the current stand-off to get past their own self-interests in order to come up with something better for all.

CORRESPONDENCE

Eric A. Henley, MD, MPH, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Illinois College of Medicine at Rockford, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107-1897. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Thorpe K. The Medical malpractice “crisis”: Recent trends and the impact of state tort reforms. Health Affairs 2004 January 21;web-only.

2. Rodwin M, Chang H, Clausen J. Malpractice premiums and physicians’ income: Perceptions of a crisis conflict with empirical evidence. Health Affairs 2006;525:750-758.

3. Studdert D, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2024-2033.

4. Guirguis-Blake J, Fryer GE, Phillips RL, Jr, Szabat R, Green LA. The US medical liability system: Evidence for legislative reform. Ann Fam Med 2006;4:240-246.

5. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA 2005;293:2609-2617.

6. Kessler DP, Sage WM, Becker DJ, et al. Impact of malpractice reforms on the supply of physician services. JAMA 2005;293:2618-2625.

7. Hellinger F, Encinosa W. The impact of state laws limiting malpractice damage awards on health care expenditures. AJPH 2006;96:1375-1381.

8. American Medical Association. Medical liability talking points. Available at: www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/399/mlr_fastfacts.pdf. Accessed on August 15, 2006.

9. Clinton HR, Obama B. Making patient safety the centerpiece of medical liability reform. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2205-2208.

10. O’Reilly K. Harvard adopts a disclosure and apology policy. AMA News, June 12, 2006.

11. Common Good. What are health courts? Available at: cgood.org/f-healthcourtsinfo.html. Accessed on August 15, 2006.

1. Thorpe K. The Medical malpractice “crisis”: Recent trends and the impact of state tort reforms. Health Affairs 2004 January 21;web-only.

2. Rodwin M, Chang H, Clausen J. Malpractice premiums and physicians’ income: Perceptions of a crisis conflict with empirical evidence. Health Affairs 2006;525:750-758.

3. Studdert D, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2024-2033.

4. Guirguis-Blake J, Fryer GE, Phillips RL, Jr, Szabat R, Green LA. The US medical liability system: Evidence for legislative reform. Ann Fam Med 2006;4:240-246.

5. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA 2005;293:2609-2617.

6. Kessler DP, Sage WM, Becker DJ, et al. Impact of malpractice reforms on the supply of physician services. JAMA 2005;293:2618-2625.

7. Hellinger F, Encinosa W. The impact of state laws limiting malpractice damage awards on health care expenditures. AJPH 2006;96:1375-1381.

8. American Medical Association. Medical liability talking points. Available at: www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/399/mlr_fastfacts.pdf. Accessed on August 15, 2006.

9. Clinton HR, Obama B. Making patient safety the centerpiece of medical liability reform. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2205-2208.

10. O’Reilly K. Harvard adopts a disclosure and apology policy. AMA News, June 12, 2006.

11. Common Good. What are health courts? Available at: cgood.org/f-healthcourtsinfo.html. Accessed on August 15, 2006.

The Journal of Family Practice ©2006 Dowden Health Media