User login

Medicare update: What the latest changes will mean for you

Medicare Part D and the more recent changes in physician payments beginning in January will of course have a financial impact on your practice in the upcoming months. Knowing what you can expect will help you to navigate the road ahead.

A 5% increase in RVU valuation

Last year the Relative Value Update Committee, an American Medical Association (AMA) convened panel that advises CMS, recommended changes in work RVUs (relative value units) that increased the value of some evaluation and management (E&M) codes—particularly 99213 and 99214. Because Medicare needs to maintain budget neutrality, this change prompted a decrease in the value of a number of procedural work RVU codes.

The net effect for a typical family physician is an average increase of 5% in RVU valuation, although the exact amount will vary in individual practices based on the distribution of the codes. (To calculate the impact that these changes may have on your anticipated revenue, check out the handy tool provided by the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). On the first page, there is a spreadsheet showing the change in RVU values from 2006 to 2007 for a number of codes; on the second page there is a worksheet to calculate changes in your anticipated revenue.1) Because many private insurers base their physician reimbursement system on Medicare RVU values, your practice may get an added benefit from these changes in your private payer collections.

A conversion factor that was poised to drop

The good news on the RVU front could have been negated by the highly publicized scheduled decrease in the overall Medicare physician fee schedule. (Actual Medicare payments are determined by multiplying the total RVU value of a code by a conversion factor [$37.895 in 2006], with some further adjustments to reflect geographic differences in expenses and efforts to maintain budget neutrality.) The conversion factor was scheduled to decrease by 5% in January, and only a last-minute intervention by Congress prevented this, leaving the 2007 conversion rate unchanged from 2006.

While this legislation will be a help to family physicians’ bottom lines in 2007, it doesn’t put an end to the annual struggles of organized medicine to forestall future Medicare payment decreases. These decreases are a result of prior legislation mandating the use of the sustainable growth rate formula (SGR) which relies on the change in the national gross domestic product to establish a yearly target for growth in the volume of Medicare payments to providers. When those payments exceed the SGR target, as it has in recent years, payments must be cut in the following year to recoup the excess spending.

Furthermore, when Congress blocks these payment cuts (as it has in the past few years) without changing the underlying law, this SGR “debt” just grows larger. This is why physician payments are projected to decrease up to 5% a year for up to 9 years.

Change may be in the making, though. Fixing the SGR payment rule remains a high priority for the AAFP, American Medical Association, and other medical organizations.

Pay-for-performance program buys physicians some time

Health care legislation, as we know, is the product of many trade-offs. Case in point: part of the deal to enact legislation that saved physicians from the 5% cut in Medicare payments was the establishment, for the first time, of a formal pay-for-performance (or more accurately, a pay-for-reporting) program starting this summer. The specifics of the program have yet to be established, but the general thrust is that Medicare will pay physicians up to a 1.5% bonus if they report data on the quality of their care using measures specified by the government.

The AAFP is relatively happy with this measure because it will start by rewarding the reporting on a small number of measures, and it will use measures developed and endorsed by national organizations such as the Ambulatory Care Quality Alliance of which the AAFP is a cofounder. AAFP’s position, however, could change as program details emerge.2

Whether the work involved in providing this data will be worth the small increase in payments is unclear. Nevertheless, it’s likely that in time, it will become increasingly difficult for physicians to avoid addressing quality indicator reporting and, eventually, being judged on the achievement of certain outcomes.

Patient satisfaction climbs with Medicare Part D

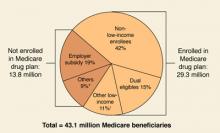

Back for its second year, the Medicare Part D program continues to feature stand-alone prescription drug plans (PDPs) for medications only and Medicare Advantage (MA) managed care plans offering drug benefits coupled with the full array of the usual Medicare benefits. Early last year, there was a great deal of concern that enrollment in the Part D program would lag, but by June, approximately 90% of the 43 million Medicare Part D eligible beneficiaries had direct drug coverage through either a Medicare PDP (16.5 million), an MA plan (6 million), or through a credible alternative plan, eg, a Medigap policy, retiree health plan, or VA plan (15.8 million).3 (For more on prescription drug coverage among Medicare beneficiaries, go to the Kaiser Family Foundation Medicare Fact Sheet.) By late 2006, 56% of seniors enrolled in a Medicare Part D plan were expressing satisfaction with the program.4

Fewer choices in the future?

Last year, 10 companies out of 266 accounted for 66% of the enrollment in Part D plans with United Healthcare and Humana dominating the marketplace.5 Companies with low numbers of enrollees may eventually lose the right to participate in the Part D program since they can’t spread the risk of medication usage across a large enough population. Also, it’s likely that about 75% of beneficiaries in a PDP will have higher premiums in 2007, although many by only a few dollars per month.5

Will the government begin direct negotiations?

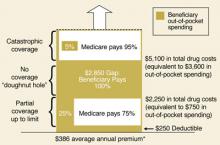

Democrats want the federal government to negotiate directly with drug companies on the price of Part D medications—something the Republicans didn’t allow in the original legislation. Now that Democrats are in control of the House and Senate, this issue will likely be revisited. In addition, because more beneficiaries will have coverage for all of 2007—as opposed to just part of 2006—it’s likely that more of them will reach the “doughnut hole” during the year. If that happens, Congress is likely to hear more complaints about the inadequacy of the program’s handling of drug costs.

The MA program may also become a political hot button. In the legislation authorizing the Part D program, the Republican-led Congress significantly increased payments to MA programs in an effort to attract more enrollees.

A Commonwealth Fund study released in November 2006, confirmed this by showing that payments for each of 5.6 million enrollees in an MA plan in 2005 averaged $922 or 12.4% more than costs for beneficiaries in the traditional Medicare fee-for-service program for a total of $5.2 billion. The Commonwealth study authors noted that these extra payments undermine the original intent of the legislation which was to have an MA program provide a more efficient alternative to the traditional Medicare program.6 This is another part of the original bill that Democrats argued against, and may be another area they choose to address in the new legislative session. With the shift in control over the House and Senate, only time will tell how Medicare Part D will evolve in the months ahead.

A poll taken done by the Kaiser Family Foundation and Harvard School of Public Health soon after the November elections showed that majorities of Democrats (92%), independents (85%), and Republicans (74%) supported the government negotiating prices for prescription drugs under Medicare and a majority of all polled (79%) supported allowing the purchase of drugs from Canada. Also, more than half supported federal funding of stem cell research.

The top health priorities were expanding coverage for the uninsured (35%) and reducing health care costs (30%). While health care and the economy were the leading domestic priorities for those polled (about 15% each), they both trailed far behind the war in Iraq (46%).

SOURCE: The Public’s Health Care Agenda for the New Congress and Presidential Campaign [Kaiser Family Foundation Web site]. December 2006. Available at: www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/pomr120806pkg.cfm. Accessed on March 20, 2007.

Correspondence

Eric Henley, University of Illinois College of Medicine at Rockford, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107. [email protected]

1. Common E/M code payment changes 2006–2007 Available at: www.aafp.org/online/etc/medialib/aafp_org/documents/prac_mgt/codingresources/emimpacttool.par.0001.File.tmp/EM%20Impact%20Tool.xls. Accessed on March 20, 2007.

2. Champlin L. Eleventh-hour vote avoids medicare cut. AAFP News Now, December 11, 2006. Available at: www.aafp.org/online/en/home/publications/news/news-now/government-medicine/20061211nomedicarecut.html. Accessed March 20, 2007.

3. The Medicare prescription Drug Benefit fact sheet [Kaiser Family Foundation Web site]. November 2006. Available at: www.kff.org/medicare/upload/7044-05.pdf. Accessed on March 20, 2007.

4. The Kaiser Family Foundation/Harvard School of Public Health Seniors and the Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit. Available at: www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/upload/7604.pdf. Accessed on March 26, 2007.

5. Hoadley J, Hargrave E, Merrell K, Cubanski J, Neuman T. Benefit design and formularies of Medicare drug plans [Kaiser Family Foundation Web site]. Available at: www.kff.org/medicare/upload/7589.pdf. Accessed on March 20, 2007.

6. Biles B, Nicholas LH, Cooper BS, Adrion E, Guterman S. The cost of privatization: extra payments to Medicare Advantage Plans—Updated and revised. [The Commonwealth Fund Web site]. November 2006. Available at: www.cmwf.org/usr_doc/Biles_costprivatizationextrapayMAplans_970_ib.pdf. Accessed March 26, 2007.

Medicare Part D and the more recent changes in physician payments beginning in January will of course have a financial impact on your practice in the upcoming months. Knowing what you can expect will help you to navigate the road ahead.

A 5% increase in RVU valuation

Last year the Relative Value Update Committee, an American Medical Association (AMA) convened panel that advises CMS, recommended changes in work RVUs (relative value units) that increased the value of some evaluation and management (E&M) codes—particularly 99213 and 99214. Because Medicare needs to maintain budget neutrality, this change prompted a decrease in the value of a number of procedural work RVU codes.

The net effect for a typical family physician is an average increase of 5% in RVU valuation, although the exact amount will vary in individual practices based on the distribution of the codes. (To calculate the impact that these changes may have on your anticipated revenue, check out the handy tool provided by the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). On the first page, there is a spreadsheet showing the change in RVU values from 2006 to 2007 for a number of codes; on the second page there is a worksheet to calculate changes in your anticipated revenue.1) Because many private insurers base their physician reimbursement system on Medicare RVU values, your practice may get an added benefit from these changes in your private payer collections.

A conversion factor that was poised to drop

The good news on the RVU front could have been negated by the highly publicized scheduled decrease in the overall Medicare physician fee schedule. (Actual Medicare payments are determined by multiplying the total RVU value of a code by a conversion factor [$37.895 in 2006], with some further adjustments to reflect geographic differences in expenses and efforts to maintain budget neutrality.) The conversion factor was scheduled to decrease by 5% in January, and only a last-minute intervention by Congress prevented this, leaving the 2007 conversion rate unchanged from 2006.

While this legislation will be a help to family physicians’ bottom lines in 2007, it doesn’t put an end to the annual struggles of organized medicine to forestall future Medicare payment decreases. These decreases are a result of prior legislation mandating the use of the sustainable growth rate formula (SGR) which relies on the change in the national gross domestic product to establish a yearly target for growth in the volume of Medicare payments to providers. When those payments exceed the SGR target, as it has in recent years, payments must be cut in the following year to recoup the excess spending.

Furthermore, when Congress blocks these payment cuts (as it has in the past few years) without changing the underlying law, this SGR “debt” just grows larger. This is why physician payments are projected to decrease up to 5% a year for up to 9 years.

Change may be in the making, though. Fixing the SGR payment rule remains a high priority for the AAFP, American Medical Association, and other medical organizations.

Pay-for-performance program buys physicians some time

Health care legislation, as we know, is the product of many trade-offs. Case in point: part of the deal to enact legislation that saved physicians from the 5% cut in Medicare payments was the establishment, for the first time, of a formal pay-for-performance (or more accurately, a pay-for-reporting) program starting this summer. The specifics of the program have yet to be established, but the general thrust is that Medicare will pay physicians up to a 1.5% bonus if they report data on the quality of their care using measures specified by the government.

The AAFP is relatively happy with this measure because it will start by rewarding the reporting on a small number of measures, and it will use measures developed and endorsed by national organizations such as the Ambulatory Care Quality Alliance of which the AAFP is a cofounder. AAFP’s position, however, could change as program details emerge.2

Whether the work involved in providing this data will be worth the small increase in payments is unclear. Nevertheless, it’s likely that in time, it will become increasingly difficult for physicians to avoid addressing quality indicator reporting and, eventually, being judged on the achievement of certain outcomes.

Patient satisfaction climbs with Medicare Part D

Back for its second year, the Medicare Part D program continues to feature stand-alone prescription drug plans (PDPs) for medications only and Medicare Advantage (MA) managed care plans offering drug benefits coupled with the full array of the usual Medicare benefits. Early last year, there was a great deal of concern that enrollment in the Part D program would lag, but by June, approximately 90% of the 43 million Medicare Part D eligible beneficiaries had direct drug coverage through either a Medicare PDP (16.5 million), an MA plan (6 million), or through a credible alternative plan, eg, a Medigap policy, retiree health plan, or VA plan (15.8 million).3 (For more on prescription drug coverage among Medicare beneficiaries, go to the Kaiser Family Foundation Medicare Fact Sheet.) By late 2006, 56% of seniors enrolled in a Medicare Part D plan were expressing satisfaction with the program.4

Fewer choices in the future?

Last year, 10 companies out of 266 accounted for 66% of the enrollment in Part D plans with United Healthcare and Humana dominating the marketplace.5 Companies with low numbers of enrollees may eventually lose the right to participate in the Part D program since they can’t spread the risk of medication usage across a large enough population. Also, it’s likely that about 75% of beneficiaries in a PDP will have higher premiums in 2007, although many by only a few dollars per month.5

Will the government begin direct negotiations?

Democrats want the federal government to negotiate directly with drug companies on the price of Part D medications—something the Republicans didn’t allow in the original legislation. Now that Democrats are in control of the House and Senate, this issue will likely be revisited. In addition, because more beneficiaries will have coverage for all of 2007—as opposed to just part of 2006—it’s likely that more of them will reach the “doughnut hole” during the year. If that happens, Congress is likely to hear more complaints about the inadequacy of the program’s handling of drug costs.

The MA program may also become a political hot button. In the legislation authorizing the Part D program, the Republican-led Congress significantly increased payments to MA programs in an effort to attract more enrollees.

A Commonwealth Fund study released in November 2006, confirmed this by showing that payments for each of 5.6 million enrollees in an MA plan in 2005 averaged $922 or 12.4% more than costs for beneficiaries in the traditional Medicare fee-for-service program for a total of $5.2 billion. The Commonwealth study authors noted that these extra payments undermine the original intent of the legislation which was to have an MA program provide a more efficient alternative to the traditional Medicare program.6 This is another part of the original bill that Democrats argued against, and may be another area they choose to address in the new legislative session. With the shift in control over the House and Senate, only time will tell how Medicare Part D will evolve in the months ahead.

A poll taken done by the Kaiser Family Foundation and Harvard School of Public Health soon after the November elections showed that majorities of Democrats (92%), independents (85%), and Republicans (74%) supported the government negotiating prices for prescription drugs under Medicare and a majority of all polled (79%) supported allowing the purchase of drugs from Canada. Also, more than half supported federal funding of stem cell research.

The top health priorities were expanding coverage for the uninsured (35%) and reducing health care costs (30%). While health care and the economy were the leading domestic priorities for those polled (about 15% each), they both trailed far behind the war in Iraq (46%).

SOURCE: The Public’s Health Care Agenda for the New Congress and Presidential Campaign [Kaiser Family Foundation Web site]. December 2006. Available at: www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/pomr120806pkg.cfm. Accessed on March 20, 2007.

Correspondence

Eric Henley, University of Illinois College of Medicine at Rockford, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107. [email protected]

Medicare Part D and the more recent changes in physician payments beginning in January will of course have a financial impact on your practice in the upcoming months. Knowing what you can expect will help you to navigate the road ahead.

A 5% increase in RVU valuation

Last year the Relative Value Update Committee, an American Medical Association (AMA) convened panel that advises CMS, recommended changes in work RVUs (relative value units) that increased the value of some evaluation and management (E&M) codes—particularly 99213 and 99214. Because Medicare needs to maintain budget neutrality, this change prompted a decrease in the value of a number of procedural work RVU codes.

The net effect for a typical family physician is an average increase of 5% in RVU valuation, although the exact amount will vary in individual practices based on the distribution of the codes. (To calculate the impact that these changes may have on your anticipated revenue, check out the handy tool provided by the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). On the first page, there is a spreadsheet showing the change in RVU values from 2006 to 2007 for a number of codes; on the second page there is a worksheet to calculate changes in your anticipated revenue.1) Because many private insurers base their physician reimbursement system on Medicare RVU values, your practice may get an added benefit from these changes in your private payer collections.

A conversion factor that was poised to drop

The good news on the RVU front could have been negated by the highly publicized scheduled decrease in the overall Medicare physician fee schedule. (Actual Medicare payments are determined by multiplying the total RVU value of a code by a conversion factor [$37.895 in 2006], with some further adjustments to reflect geographic differences in expenses and efforts to maintain budget neutrality.) The conversion factor was scheduled to decrease by 5% in January, and only a last-minute intervention by Congress prevented this, leaving the 2007 conversion rate unchanged from 2006.

While this legislation will be a help to family physicians’ bottom lines in 2007, it doesn’t put an end to the annual struggles of organized medicine to forestall future Medicare payment decreases. These decreases are a result of prior legislation mandating the use of the sustainable growth rate formula (SGR) which relies on the change in the national gross domestic product to establish a yearly target for growth in the volume of Medicare payments to providers. When those payments exceed the SGR target, as it has in recent years, payments must be cut in the following year to recoup the excess spending.

Furthermore, when Congress blocks these payment cuts (as it has in the past few years) without changing the underlying law, this SGR “debt” just grows larger. This is why physician payments are projected to decrease up to 5% a year for up to 9 years.

Change may be in the making, though. Fixing the SGR payment rule remains a high priority for the AAFP, American Medical Association, and other medical organizations.

Pay-for-performance program buys physicians some time

Health care legislation, as we know, is the product of many trade-offs. Case in point: part of the deal to enact legislation that saved physicians from the 5% cut in Medicare payments was the establishment, for the first time, of a formal pay-for-performance (or more accurately, a pay-for-reporting) program starting this summer. The specifics of the program have yet to be established, but the general thrust is that Medicare will pay physicians up to a 1.5% bonus if they report data on the quality of their care using measures specified by the government.

The AAFP is relatively happy with this measure because it will start by rewarding the reporting on a small number of measures, and it will use measures developed and endorsed by national organizations such as the Ambulatory Care Quality Alliance of which the AAFP is a cofounder. AAFP’s position, however, could change as program details emerge.2

Whether the work involved in providing this data will be worth the small increase in payments is unclear. Nevertheless, it’s likely that in time, it will become increasingly difficult for physicians to avoid addressing quality indicator reporting and, eventually, being judged on the achievement of certain outcomes.

Patient satisfaction climbs with Medicare Part D

Back for its second year, the Medicare Part D program continues to feature stand-alone prescription drug plans (PDPs) for medications only and Medicare Advantage (MA) managed care plans offering drug benefits coupled with the full array of the usual Medicare benefits. Early last year, there was a great deal of concern that enrollment in the Part D program would lag, but by June, approximately 90% of the 43 million Medicare Part D eligible beneficiaries had direct drug coverage through either a Medicare PDP (16.5 million), an MA plan (6 million), or through a credible alternative plan, eg, a Medigap policy, retiree health plan, or VA plan (15.8 million).3 (For more on prescription drug coverage among Medicare beneficiaries, go to the Kaiser Family Foundation Medicare Fact Sheet.) By late 2006, 56% of seniors enrolled in a Medicare Part D plan were expressing satisfaction with the program.4

Fewer choices in the future?

Last year, 10 companies out of 266 accounted for 66% of the enrollment in Part D plans with United Healthcare and Humana dominating the marketplace.5 Companies with low numbers of enrollees may eventually lose the right to participate in the Part D program since they can’t spread the risk of medication usage across a large enough population. Also, it’s likely that about 75% of beneficiaries in a PDP will have higher premiums in 2007, although many by only a few dollars per month.5

Will the government begin direct negotiations?

Democrats want the federal government to negotiate directly with drug companies on the price of Part D medications—something the Republicans didn’t allow in the original legislation. Now that Democrats are in control of the House and Senate, this issue will likely be revisited. In addition, because more beneficiaries will have coverage for all of 2007—as opposed to just part of 2006—it’s likely that more of them will reach the “doughnut hole” during the year. If that happens, Congress is likely to hear more complaints about the inadequacy of the program’s handling of drug costs.

The MA program may also become a political hot button. In the legislation authorizing the Part D program, the Republican-led Congress significantly increased payments to MA programs in an effort to attract more enrollees.

A Commonwealth Fund study released in November 2006, confirmed this by showing that payments for each of 5.6 million enrollees in an MA plan in 2005 averaged $922 or 12.4% more than costs for beneficiaries in the traditional Medicare fee-for-service program for a total of $5.2 billion. The Commonwealth study authors noted that these extra payments undermine the original intent of the legislation which was to have an MA program provide a more efficient alternative to the traditional Medicare program.6 This is another part of the original bill that Democrats argued against, and may be another area they choose to address in the new legislative session. With the shift in control over the House and Senate, only time will tell how Medicare Part D will evolve in the months ahead.

A poll taken done by the Kaiser Family Foundation and Harvard School of Public Health soon after the November elections showed that majorities of Democrats (92%), independents (85%), and Republicans (74%) supported the government negotiating prices for prescription drugs under Medicare and a majority of all polled (79%) supported allowing the purchase of drugs from Canada. Also, more than half supported federal funding of stem cell research.

The top health priorities were expanding coverage for the uninsured (35%) and reducing health care costs (30%). While health care and the economy were the leading domestic priorities for those polled (about 15% each), they both trailed far behind the war in Iraq (46%).

SOURCE: The Public’s Health Care Agenda for the New Congress and Presidential Campaign [Kaiser Family Foundation Web site]. December 2006. Available at: www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/pomr120806pkg.cfm. Accessed on March 20, 2007.

Correspondence

Eric Henley, University of Illinois College of Medicine at Rockford, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107. [email protected]

1. Common E/M code payment changes 2006–2007 Available at: www.aafp.org/online/etc/medialib/aafp_org/documents/prac_mgt/codingresources/emimpacttool.par.0001.File.tmp/EM%20Impact%20Tool.xls. Accessed on March 20, 2007.

2. Champlin L. Eleventh-hour vote avoids medicare cut. AAFP News Now, December 11, 2006. Available at: www.aafp.org/online/en/home/publications/news/news-now/government-medicine/20061211nomedicarecut.html. Accessed March 20, 2007.

3. The Medicare prescription Drug Benefit fact sheet [Kaiser Family Foundation Web site]. November 2006. Available at: www.kff.org/medicare/upload/7044-05.pdf. Accessed on March 20, 2007.

4. The Kaiser Family Foundation/Harvard School of Public Health Seniors and the Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit. Available at: www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/upload/7604.pdf. Accessed on March 26, 2007.

5. Hoadley J, Hargrave E, Merrell K, Cubanski J, Neuman T. Benefit design and formularies of Medicare drug plans [Kaiser Family Foundation Web site]. Available at: www.kff.org/medicare/upload/7589.pdf. Accessed on March 20, 2007.

6. Biles B, Nicholas LH, Cooper BS, Adrion E, Guterman S. The cost of privatization: extra payments to Medicare Advantage Plans—Updated and revised. [The Commonwealth Fund Web site]. November 2006. Available at: www.cmwf.org/usr_doc/Biles_costprivatizationextrapayMAplans_970_ib.pdf. Accessed March 26, 2007.

1. Common E/M code payment changes 2006–2007 Available at: www.aafp.org/online/etc/medialib/aafp_org/documents/prac_mgt/codingresources/emimpacttool.par.0001.File.tmp/EM%20Impact%20Tool.xls. Accessed on March 20, 2007.

2. Champlin L. Eleventh-hour vote avoids medicare cut. AAFP News Now, December 11, 2006. Available at: www.aafp.org/online/en/home/publications/news/news-now/government-medicine/20061211nomedicarecut.html. Accessed March 20, 2007.

3. The Medicare prescription Drug Benefit fact sheet [Kaiser Family Foundation Web site]. November 2006. Available at: www.kff.org/medicare/upload/7044-05.pdf. Accessed on March 20, 2007.

4. The Kaiser Family Foundation/Harvard School of Public Health Seniors and the Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit. Available at: www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/upload/7604.pdf. Accessed on March 26, 2007.

5. Hoadley J, Hargrave E, Merrell K, Cubanski J, Neuman T. Benefit design and formularies of Medicare drug plans [Kaiser Family Foundation Web site]. Available at: www.kff.org/medicare/upload/7589.pdf. Accessed on March 20, 2007.

6. Biles B, Nicholas LH, Cooper BS, Adrion E, Guterman S. The cost of privatization: extra payments to Medicare Advantage Plans—Updated and revised. [The Commonwealth Fund Web site]. November 2006. Available at: www.cmwf.org/usr_doc/Biles_costprivatizationextrapayMAplans_970_ib.pdf. Accessed March 26, 2007.

What hope is there for meaningful tort reform to stop another malpractice crisis?

A handful of papers published in the past few years have looked at different aspects of the current malpractice situation and have yielded some revelations (see page 775 in this issue) or data banks working on safety issues.

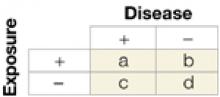

- Though it does a reasonable job at separating valid from invalid claims and compensating them accordingly, it often takes a tremendously long time to accomplish this and still has a 10% to 16% rate of false positive (payment with no error) and false negative (no payment with error) outcomes.

- The system is not overwhelmed with frivolous claims. Still, it costs a lot of money to manage, and less than half of this money goes to claimants.

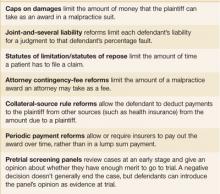

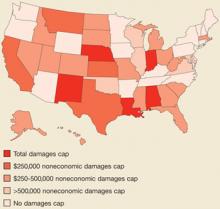

- Hard caps on total damages or noneconomic damages, unlike other state tort reforms (Figure), appear to reduce claims payments, physician premiums, and total health costs,7 while increasing physician supply.

- Defensive medicine exists, though putting a valid dollar amount on its costs is difficult.

- Anecdotal evidence suggests that physicians are leaving practice or limiting their practice (eg, family physicians discontinuing deliveries) as a result of malpractice costs.

FIGURE

Tort reforms commonly adopted by states

AMA’s proposal for change

Malpractice reform has been at or near the top of the AMA’s political agenda for the past 4 or 5 years, with strong lobbying efforts at the national level as well as support for state chapter efforts. The AMA’s proposal is based on California’s liability reform law known as MICRA that was passed over 30 years ago and has been associated with significantly lower premium growth since then compared with the rest of the US.8 Key provisions:

- Unlimited economic damages (medical expenses, future earnings)

- Limits on noneconomic damages (pain and suffering)

- Punitive damages, if available, up to $250,000 or 2 times economic damages, whichever is greater

- Allocation of damage awards in proportion to fault

- Sliding scale for attorney contingency fees.

Dubious premises. The AMA literature on malpractice includes valid information on the costs of the tort system, the rise in claims payouts, and effects on physician premiums. But it also suggests that meritless lawsuits are increasing. This is untrue. And its implication that physicians are increasingly leaving practice is anecdotal. There is no good research on the extent of this problem.8

Too narrow a focus. More important, the AMA plan is focused on physician premium costs while ignoring the unfairness of the system (eg, time to resolve claims, lack of payment for many patients with legitimate claims) and the vast number of medical errors for which claims are never filed.

The MEDIC proposal

Senators Hillary Clinton (D-NY) and Barack Obama (D-IL) have proposed federal legislation to address the malpractice crisis. Their bill would create an Office of Patient Safety in the Department of Health and Human Services, and would establish the National Medical Error Disclosure and Compensation (MEDIC) program within that office.9

Apologies would not be actionable in court. The MEDIC program would provide grants to physicians, hospitals, and health systems for the creation of programs to disclose medical errors to patients and negotiate fair compensation. The law would preserve confidentiality so that any apology offered by a health care provider as part of those negotiations would be kept confidential and could not be used in a trial. Any savings achieved from lower administrative and legal costs would be used to reduce physician malpractice premiums and toward patient safety initiatives.

Federal mandating of caps unlikely, however. At the federal level, Democrats have firmly opposed mandating caps on malpractice claims settlements. They argue that caps are unfair to patients who have been victims of medical errors. Others say this opposition reflects financial contributions from trial lawyers. It seems time to get past this conflict. Without dramatic changes in the composition of the Senate, which seems unlikely, there is little or no chance that caps will pass at the national level. At the same time, physician groups have been successful at achieving caps in a number of states (total of 26 at last count).

Signs this program could succeed. The MEDIC proposal is an attempt to find another way out of the malpractice impasse in the Senate by linking the patient safety and tort reform issues. It is primarily based on a growing movement to have physicians more directly acknowledge medical errors to patients,10 and in some cases, link these apologies to immediate financial negotiations to settle any potential claim of injury. The University of Michigan is the best known academic institution pursuing these strategies, and they report a significant decrease in the number of claims and annual litigation costs. The Lexington, Kentucky, VA Hospital has a similar program that has reduced liability costs compared with other VA hospitals.

The MEDIC proposal is attractive in its attempt to tie doctor-patient communication, patient safety, and liability together. And the anecdotal reports of success with isolated programs of its type are encouraging. It also moves the argument at a national level away from a fight about caps, which puts many physicians in the uncomfortable position of opposing Democrats who support many of their other positions—eg, Title VII funding, preservation of the traditional Medicare program, expansion of the Medicare Part D program, and better funding of public health programs. Nonetheless, there is a big row to hoe in making physicians more comfortable with acknowledging their errors, convincing them this would not be held against them in court, and assuring both physicians and hospitals that such efforts will actually lead to lower malpractice costs.

Thorpe analyzed data from 1995–2001 collected by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners to see the relationship between state tort reforms and premium levels. Premiums in states with caps on awards were 17% lower than states without caps. There was no association between premium levels and other reforms, such as caps on attorney fees or collateral offset rules (decreasing awards by the amount the plaintiff receives from other sources). Some association was noted between decreased competition among insurers and higher premiums.1

Rodwin et al used data from AMA surveys of self-employed physicians (physicians in groups or solo practice who are not employees) from 1970 to 2000. They found that while premiums increased from 1970 to 1986 and from 1996 to 2000, they had only a small effect on physician income. Premiums made up a small percentage of total practice costs and had a negligible effect on practice income, arguing against a malpractice crisis. However, this study lacked more recent data on premium increases and practice expenses and did not take into account differences among states that might be due to tort reforms such as the institution of caps on awards.2

Studdert et al reviewed 1452 closed claims in 4 categories (obstetrics, surgery, missed or delayed diagnosis, and medication) from 5 liability insurers representing 4 regions of the US, and used objective criteria and independent reviewers to classify the merits of the claims. They found that 3% of the claims had no verifiable medical injury and 37% did not involve errors. About 73% of the claims not associated with errors or injuries resulted in no compensation, while 73% of those with errors did result in compensation. Further payment for claims not involving errors were lower than those that did involve errors. Looked at another way, of the 1452 claims reviewed, about 10% received payment but had no identifiable error, while about 17% had an identifiable error but no payment was made.3

This study demonstrated that: 1) the cost of defending claims involving no error was substantial but still only amounted to about 13% of direct system costs, meaning that contesting and paying for claims caused by errors accounts for most of the costs of the liability system, and 2) the malpractice system works reasonably well at separating claims without merit from those with merit.

Nonetheless, the study also demonstrated the unfairness of a system in which 1 in 6 valid claims received no payment (this in addition to the vast number of negligent injuries that never even lead to a claim as discussed in the 1999 IOM report). Then there is the frustration with a system wherein the average time between injury and claim resolution is 5 years and 54% of the payments are absorbed by defense costs and contingency fees. That 80% of expenses were incurred in resolving claims with errors suggests that steps to decrease frivolous litigation (claims without merit) will not lead to substantial savings and that steps to streamlining the system of handling claims will be more useful.

Blake et al looked at state-specific data from the National Practitioner Data Bank, which collects reports of all malpractice payments in the US on behalf of physicians, dentists, and nurses. They looked at the relationship between payments, physician premiums, and various state tort reforms. They found that mean payments were 26% lower in states with total damage caps ($196,000 vs $265,000) and 22% less in states with noneconomic (pain and suffering) damage caps ($212,000 vs $279,000). In addition, total damage caps were associated with lower mean annual premiums and hard, but not soft (caps with exceptions) noneconomic caps were associated with premium reductions. No other state tort reforms measured showed a significant association with payments or premiums.4

Studdert et al surveyed Pennsylvania physicians in high-risk specialties (obstetrics/gynecology, ortho, ER, surgery, neurosurgery) to ascertain self-report of defensive medicine practice. Almost all respondents reported practicing defensive medicine, the most common form (92%) being unnecessary ordering of tests and imaging studies and referring for consultation. In addition, 42% said they had restricted their practice by either decreasing the performance of more risky procedures (eg, trauma surgery) or avoiding complex cases or patients perceived as more likely to sue. Defensive medicine was highly correlated with physicians’ lack of confidence in their liability insurance or its cost.5

Kessler et al looked at physician supply from 1985–2001 and its correlates to state tort reforms during that time. Three years after States that adopted direct reforms (mainly caps on damage awards) showed an average physician growth rate within 3 years that was 3.3% greater than states not adopting such reforms. The authors controlled for a variety of factors that can influence physician supply including population growth and other state-level characteristics.6

Common Good proposal

Another approach is advocated by Common Good, a bipartisan legal reform coalition. This organization has funding from the RWJ Foundation to work with researchers from the Harvard School of Public Health to investigate the creation of special health courts to hear malpractice cases.11 Their ideas are incorporated into the Fair and Reliable Medical Justice Act introduced as S.1337 by Senators Mike Enzi (R-WY) Max Baucus (D-MT).11

How it would work. Health courts would have full-time judges, neutral medical experts, faster proceedings with legal fees held to 20%, and rulings that could be appealed to a new Medical Appellate Court. Like other administrative courts that handle tax disputes, workmen’s comp, and vaccine injury, there would be no juries. Judges would issue written rulings and establish legal precedents. Once a mistake was verified, recovery would be automatic. Patients would be reimbursed for all their medical expenses and lost income plus a fixed sum that would be determined from an expert derived schedule addressing specific types of injuries.

Strengths and weaknesses. This proposal has the support of a wide array of national medical and legal leaders but not any medical associations. It attempts to address some of the most egregious parts of the current system—the time it takes to get claims resolved, the many errors that go uncompensated, and the diversion of so many dollars to overhead and legal fees rather than to patients. On the other hand, the plan does not provide firm caps, which may make the AMA and other professional associations skeptical. And the proposed health courts would rely on select medical experts and judges, a system likely to be strongly opposed by trial lawyers and some consumer groups. It also does not directly address the prevention of patient errors.

Those who fail to learn from history…

The current malpractice crisis may be abating, leaving physicians with higher malpractice premiums but some state tort reforms. History, however, suggests that the insurance cycle will eventually lead to another crisis. There may be a window of opportunity now to come up with a completely different system to address the goals and problems with our current system, but it is likely to be a small window. Capitalizing on it will require a willingness for both sides in the current stand-off to get past their own self-interests in order to come up with something better for all.

CORRESPONDENCE

Eric A. Henley, MD, MPH, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Illinois College of Medicine at Rockford, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107-1897. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Thorpe K. The Medical malpractice “crisis”: Recent trends and the impact of state tort reforms. Health Affairs 2004 January 21;web-only.

2. Rodwin M, Chang H, Clausen J. Malpractice premiums and physicians’ income: Perceptions of a crisis conflict with empirical evidence. Health Affairs 2006;525:750-758.

3. Studdert D, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2024-2033.

4. Guirguis-Blake J, Fryer GE, Phillips RL, Jr, Szabat R, Green LA. The US medical liability system: Evidence for legislative reform. Ann Fam Med 2006;4:240-246.

5. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA 2005;293:2609-2617.

6. Kessler DP, Sage WM, Becker DJ, et al. Impact of malpractice reforms on the supply of physician services. JAMA 2005;293:2618-2625.

7. Hellinger F, Encinosa W. The impact of state laws limiting malpractice damage awards on health care expenditures. AJPH 2006;96:1375-1381.

8. American Medical Association. Medical liability talking points. Available at: www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/399/mlr_fastfacts.pdf. Accessed on August 15, 2006.

9. Clinton HR, Obama B. Making patient safety the centerpiece of medical liability reform. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2205-2208.

10. O’Reilly K. Harvard adopts a disclosure and apology policy. AMA News, June 12, 2006.

11. Common Good. What are health courts? Available at: cgood.org/f-healthcourtsinfo.html. Accessed on August 15, 2006.

A handful of papers published in the past few years have looked at different aspects of the current malpractice situation and have yielded some revelations (see page 775 in this issue) or data banks working on safety issues.

- Though it does a reasonable job at separating valid from invalid claims and compensating them accordingly, it often takes a tremendously long time to accomplish this and still has a 10% to 16% rate of false positive (payment with no error) and false negative (no payment with error) outcomes.

- The system is not overwhelmed with frivolous claims. Still, it costs a lot of money to manage, and less than half of this money goes to claimants.

- Hard caps on total damages or noneconomic damages, unlike other state tort reforms (Figure), appear to reduce claims payments, physician premiums, and total health costs,7 while increasing physician supply.

- Defensive medicine exists, though putting a valid dollar amount on its costs is difficult.

- Anecdotal evidence suggests that physicians are leaving practice or limiting their practice (eg, family physicians discontinuing deliveries) as a result of malpractice costs.

FIGURE

Tort reforms commonly adopted by states

AMA’s proposal for change

Malpractice reform has been at or near the top of the AMA’s political agenda for the past 4 or 5 years, with strong lobbying efforts at the national level as well as support for state chapter efforts. The AMA’s proposal is based on California’s liability reform law known as MICRA that was passed over 30 years ago and has been associated with significantly lower premium growth since then compared with the rest of the US.8 Key provisions:

- Unlimited economic damages (medical expenses, future earnings)

- Limits on noneconomic damages (pain and suffering)

- Punitive damages, if available, up to $250,000 or 2 times economic damages, whichever is greater

- Allocation of damage awards in proportion to fault

- Sliding scale for attorney contingency fees.

Dubious premises. The AMA literature on malpractice includes valid information on the costs of the tort system, the rise in claims payouts, and effects on physician premiums. But it also suggests that meritless lawsuits are increasing. This is untrue. And its implication that physicians are increasingly leaving practice is anecdotal. There is no good research on the extent of this problem.8

Too narrow a focus. More important, the AMA plan is focused on physician premium costs while ignoring the unfairness of the system (eg, time to resolve claims, lack of payment for many patients with legitimate claims) and the vast number of medical errors for which claims are never filed.

The MEDIC proposal

Senators Hillary Clinton (D-NY) and Barack Obama (D-IL) have proposed federal legislation to address the malpractice crisis. Their bill would create an Office of Patient Safety in the Department of Health and Human Services, and would establish the National Medical Error Disclosure and Compensation (MEDIC) program within that office.9

Apologies would not be actionable in court. The MEDIC program would provide grants to physicians, hospitals, and health systems for the creation of programs to disclose medical errors to patients and negotiate fair compensation. The law would preserve confidentiality so that any apology offered by a health care provider as part of those negotiations would be kept confidential and could not be used in a trial. Any savings achieved from lower administrative and legal costs would be used to reduce physician malpractice premiums and toward patient safety initiatives.

Federal mandating of caps unlikely, however. At the federal level, Democrats have firmly opposed mandating caps on malpractice claims settlements. They argue that caps are unfair to patients who have been victims of medical errors. Others say this opposition reflects financial contributions from trial lawyers. It seems time to get past this conflict. Without dramatic changes in the composition of the Senate, which seems unlikely, there is little or no chance that caps will pass at the national level. At the same time, physician groups have been successful at achieving caps in a number of states (total of 26 at last count).

Signs this program could succeed. The MEDIC proposal is an attempt to find another way out of the malpractice impasse in the Senate by linking the patient safety and tort reform issues. It is primarily based on a growing movement to have physicians more directly acknowledge medical errors to patients,10 and in some cases, link these apologies to immediate financial negotiations to settle any potential claim of injury. The University of Michigan is the best known academic institution pursuing these strategies, and they report a significant decrease in the number of claims and annual litigation costs. The Lexington, Kentucky, VA Hospital has a similar program that has reduced liability costs compared with other VA hospitals.

The MEDIC proposal is attractive in its attempt to tie doctor-patient communication, patient safety, and liability together. And the anecdotal reports of success with isolated programs of its type are encouraging. It also moves the argument at a national level away from a fight about caps, which puts many physicians in the uncomfortable position of opposing Democrats who support many of their other positions—eg, Title VII funding, preservation of the traditional Medicare program, expansion of the Medicare Part D program, and better funding of public health programs. Nonetheless, there is a big row to hoe in making physicians more comfortable with acknowledging their errors, convincing them this would not be held against them in court, and assuring both physicians and hospitals that such efforts will actually lead to lower malpractice costs.

Thorpe analyzed data from 1995–2001 collected by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners to see the relationship between state tort reforms and premium levels. Premiums in states with caps on awards were 17% lower than states without caps. There was no association between premium levels and other reforms, such as caps on attorney fees or collateral offset rules (decreasing awards by the amount the plaintiff receives from other sources). Some association was noted between decreased competition among insurers and higher premiums.1

Rodwin et al used data from AMA surveys of self-employed physicians (physicians in groups or solo practice who are not employees) from 1970 to 2000. They found that while premiums increased from 1970 to 1986 and from 1996 to 2000, they had only a small effect on physician income. Premiums made up a small percentage of total practice costs and had a negligible effect on practice income, arguing against a malpractice crisis. However, this study lacked more recent data on premium increases and practice expenses and did not take into account differences among states that might be due to tort reforms such as the institution of caps on awards.2

Studdert et al reviewed 1452 closed claims in 4 categories (obstetrics, surgery, missed or delayed diagnosis, and medication) from 5 liability insurers representing 4 regions of the US, and used objective criteria and independent reviewers to classify the merits of the claims. They found that 3% of the claims had no verifiable medical injury and 37% did not involve errors. About 73% of the claims not associated with errors or injuries resulted in no compensation, while 73% of those with errors did result in compensation. Further payment for claims not involving errors were lower than those that did involve errors. Looked at another way, of the 1452 claims reviewed, about 10% received payment but had no identifiable error, while about 17% had an identifiable error but no payment was made.3

This study demonstrated that: 1) the cost of defending claims involving no error was substantial but still only amounted to about 13% of direct system costs, meaning that contesting and paying for claims caused by errors accounts for most of the costs of the liability system, and 2) the malpractice system works reasonably well at separating claims without merit from those with merit.

Nonetheless, the study also demonstrated the unfairness of a system in which 1 in 6 valid claims received no payment (this in addition to the vast number of negligent injuries that never even lead to a claim as discussed in the 1999 IOM report). Then there is the frustration with a system wherein the average time between injury and claim resolution is 5 years and 54% of the payments are absorbed by defense costs and contingency fees. That 80% of expenses were incurred in resolving claims with errors suggests that steps to decrease frivolous litigation (claims without merit) will not lead to substantial savings and that steps to streamlining the system of handling claims will be more useful.

Blake et al looked at state-specific data from the National Practitioner Data Bank, which collects reports of all malpractice payments in the US on behalf of physicians, dentists, and nurses. They looked at the relationship between payments, physician premiums, and various state tort reforms. They found that mean payments were 26% lower in states with total damage caps ($196,000 vs $265,000) and 22% less in states with noneconomic (pain and suffering) damage caps ($212,000 vs $279,000). In addition, total damage caps were associated with lower mean annual premiums and hard, but not soft (caps with exceptions) noneconomic caps were associated with premium reductions. No other state tort reforms measured showed a significant association with payments or premiums.4

Studdert et al surveyed Pennsylvania physicians in high-risk specialties (obstetrics/gynecology, ortho, ER, surgery, neurosurgery) to ascertain self-report of defensive medicine practice. Almost all respondents reported practicing defensive medicine, the most common form (92%) being unnecessary ordering of tests and imaging studies and referring for consultation. In addition, 42% said they had restricted their practice by either decreasing the performance of more risky procedures (eg, trauma surgery) or avoiding complex cases or patients perceived as more likely to sue. Defensive medicine was highly correlated with physicians’ lack of confidence in their liability insurance or its cost.5

Kessler et al looked at physician supply from 1985–2001 and its correlates to state tort reforms during that time. Three years after States that adopted direct reforms (mainly caps on damage awards) showed an average physician growth rate within 3 years that was 3.3% greater than states not adopting such reforms. The authors controlled for a variety of factors that can influence physician supply including population growth and other state-level characteristics.6

Common Good proposal

Another approach is advocated by Common Good, a bipartisan legal reform coalition. This organization has funding from the RWJ Foundation to work with researchers from the Harvard School of Public Health to investigate the creation of special health courts to hear malpractice cases.11 Their ideas are incorporated into the Fair and Reliable Medical Justice Act introduced as S.1337 by Senators Mike Enzi (R-WY) Max Baucus (D-MT).11

How it would work. Health courts would have full-time judges, neutral medical experts, faster proceedings with legal fees held to 20%, and rulings that could be appealed to a new Medical Appellate Court. Like other administrative courts that handle tax disputes, workmen’s comp, and vaccine injury, there would be no juries. Judges would issue written rulings and establish legal precedents. Once a mistake was verified, recovery would be automatic. Patients would be reimbursed for all their medical expenses and lost income plus a fixed sum that would be determined from an expert derived schedule addressing specific types of injuries.

Strengths and weaknesses. This proposal has the support of a wide array of national medical and legal leaders but not any medical associations. It attempts to address some of the most egregious parts of the current system—the time it takes to get claims resolved, the many errors that go uncompensated, and the diversion of so many dollars to overhead and legal fees rather than to patients. On the other hand, the plan does not provide firm caps, which may make the AMA and other professional associations skeptical. And the proposed health courts would rely on select medical experts and judges, a system likely to be strongly opposed by trial lawyers and some consumer groups. It also does not directly address the prevention of patient errors.

Those who fail to learn from history…

The current malpractice crisis may be abating, leaving physicians with higher malpractice premiums but some state tort reforms. History, however, suggests that the insurance cycle will eventually lead to another crisis. There may be a window of opportunity now to come up with a completely different system to address the goals and problems with our current system, but it is likely to be a small window. Capitalizing on it will require a willingness for both sides in the current stand-off to get past their own self-interests in order to come up with something better for all.

CORRESPONDENCE

Eric A. Henley, MD, MPH, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Illinois College of Medicine at Rockford, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107-1897. E-mail: [email protected]

A handful of papers published in the past few years have looked at different aspects of the current malpractice situation and have yielded some revelations (see page 775 in this issue) or data banks working on safety issues.

- Though it does a reasonable job at separating valid from invalid claims and compensating them accordingly, it often takes a tremendously long time to accomplish this and still has a 10% to 16% rate of false positive (payment with no error) and false negative (no payment with error) outcomes.

- The system is not overwhelmed with frivolous claims. Still, it costs a lot of money to manage, and less than half of this money goes to claimants.

- Hard caps on total damages or noneconomic damages, unlike other state tort reforms (Figure), appear to reduce claims payments, physician premiums, and total health costs,7 while increasing physician supply.

- Defensive medicine exists, though putting a valid dollar amount on its costs is difficult.

- Anecdotal evidence suggests that physicians are leaving practice or limiting their practice (eg, family physicians discontinuing deliveries) as a result of malpractice costs.

FIGURE

Tort reforms commonly adopted by states

AMA’s proposal for change

Malpractice reform has been at or near the top of the AMA’s political agenda for the past 4 or 5 years, with strong lobbying efforts at the national level as well as support for state chapter efforts. The AMA’s proposal is based on California’s liability reform law known as MICRA that was passed over 30 years ago and has been associated with significantly lower premium growth since then compared with the rest of the US.8 Key provisions:

- Unlimited economic damages (medical expenses, future earnings)

- Limits on noneconomic damages (pain and suffering)

- Punitive damages, if available, up to $250,000 or 2 times economic damages, whichever is greater

- Allocation of damage awards in proportion to fault

- Sliding scale for attorney contingency fees.

Dubious premises. The AMA literature on malpractice includes valid information on the costs of the tort system, the rise in claims payouts, and effects on physician premiums. But it also suggests that meritless lawsuits are increasing. This is untrue. And its implication that physicians are increasingly leaving practice is anecdotal. There is no good research on the extent of this problem.8

Too narrow a focus. More important, the AMA plan is focused on physician premium costs while ignoring the unfairness of the system (eg, time to resolve claims, lack of payment for many patients with legitimate claims) and the vast number of medical errors for which claims are never filed.

The MEDIC proposal

Senators Hillary Clinton (D-NY) and Barack Obama (D-IL) have proposed federal legislation to address the malpractice crisis. Their bill would create an Office of Patient Safety in the Department of Health and Human Services, and would establish the National Medical Error Disclosure and Compensation (MEDIC) program within that office.9

Apologies would not be actionable in court. The MEDIC program would provide grants to physicians, hospitals, and health systems for the creation of programs to disclose medical errors to patients and negotiate fair compensation. The law would preserve confidentiality so that any apology offered by a health care provider as part of those negotiations would be kept confidential and could not be used in a trial. Any savings achieved from lower administrative and legal costs would be used to reduce physician malpractice premiums and toward patient safety initiatives.

Federal mandating of caps unlikely, however. At the federal level, Democrats have firmly opposed mandating caps on malpractice claims settlements. They argue that caps are unfair to patients who have been victims of medical errors. Others say this opposition reflects financial contributions from trial lawyers. It seems time to get past this conflict. Without dramatic changes in the composition of the Senate, which seems unlikely, there is little or no chance that caps will pass at the national level. At the same time, physician groups have been successful at achieving caps in a number of states (total of 26 at last count).

Signs this program could succeed. The MEDIC proposal is an attempt to find another way out of the malpractice impasse in the Senate by linking the patient safety and tort reform issues. It is primarily based on a growing movement to have physicians more directly acknowledge medical errors to patients,10 and in some cases, link these apologies to immediate financial negotiations to settle any potential claim of injury. The University of Michigan is the best known academic institution pursuing these strategies, and they report a significant decrease in the number of claims and annual litigation costs. The Lexington, Kentucky, VA Hospital has a similar program that has reduced liability costs compared with other VA hospitals.

The MEDIC proposal is attractive in its attempt to tie doctor-patient communication, patient safety, and liability together. And the anecdotal reports of success with isolated programs of its type are encouraging. It also moves the argument at a national level away from a fight about caps, which puts many physicians in the uncomfortable position of opposing Democrats who support many of their other positions—eg, Title VII funding, preservation of the traditional Medicare program, expansion of the Medicare Part D program, and better funding of public health programs. Nonetheless, there is a big row to hoe in making physicians more comfortable with acknowledging their errors, convincing them this would not be held against them in court, and assuring both physicians and hospitals that such efforts will actually lead to lower malpractice costs.

Thorpe analyzed data from 1995–2001 collected by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners to see the relationship between state tort reforms and premium levels. Premiums in states with caps on awards were 17% lower than states without caps. There was no association between premium levels and other reforms, such as caps on attorney fees or collateral offset rules (decreasing awards by the amount the plaintiff receives from other sources). Some association was noted between decreased competition among insurers and higher premiums.1

Rodwin et al used data from AMA surveys of self-employed physicians (physicians in groups or solo practice who are not employees) from 1970 to 2000. They found that while premiums increased from 1970 to 1986 and from 1996 to 2000, they had only a small effect on physician income. Premiums made up a small percentage of total practice costs and had a negligible effect on practice income, arguing against a malpractice crisis. However, this study lacked more recent data on premium increases and practice expenses and did not take into account differences among states that might be due to tort reforms such as the institution of caps on awards.2

Studdert et al reviewed 1452 closed claims in 4 categories (obstetrics, surgery, missed or delayed diagnosis, and medication) from 5 liability insurers representing 4 regions of the US, and used objective criteria and independent reviewers to classify the merits of the claims. They found that 3% of the claims had no verifiable medical injury and 37% did not involve errors. About 73% of the claims not associated with errors or injuries resulted in no compensation, while 73% of those with errors did result in compensation. Further payment for claims not involving errors were lower than those that did involve errors. Looked at another way, of the 1452 claims reviewed, about 10% received payment but had no identifiable error, while about 17% had an identifiable error but no payment was made.3

This study demonstrated that: 1) the cost of defending claims involving no error was substantial but still only amounted to about 13% of direct system costs, meaning that contesting and paying for claims caused by errors accounts for most of the costs of the liability system, and 2) the malpractice system works reasonably well at separating claims without merit from those with merit.

Nonetheless, the study also demonstrated the unfairness of a system in which 1 in 6 valid claims received no payment (this in addition to the vast number of negligent injuries that never even lead to a claim as discussed in the 1999 IOM report). Then there is the frustration with a system wherein the average time between injury and claim resolution is 5 years and 54% of the payments are absorbed by defense costs and contingency fees. That 80% of expenses were incurred in resolving claims with errors suggests that steps to decrease frivolous litigation (claims without merit) will not lead to substantial savings and that steps to streamlining the system of handling claims will be more useful.

Blake et al looked at state-specific data from the National Practitioner Data Bank, which collects reports of all malpractice payments in the US on behalf of physicians, dentists, and nurses. They looked at the relationship between payments, physician premiums, and various state tort reforms. They found that mean payments were 26% lower in states with total damage caps ($196,000 vs $265,000) and 22% less in states with noneconomic (pain and suffering) damage caps ($212,000 vs $279,000). In addition, total damage caps were associated with lower mean annual premiums and hard, but not soft (caps with exceptions) noneconomic caps were associated with premium reductions. No other state tort reforms measured showed a significant association with payments or premiums.4

Studdert et al surveyed Pennsylvania physicians in high-risk specialties (obstetrics/gynecology, ortho, ER, surgery, neurosurgery) to ascertain self-report of defensive medicine practice. Almost all respondents reported practicing defensive medicine, the most common form (92%) being unnecessary ordering of tests and imaging studies and referring for consultation. In addition, 42% said they had restricted their practice by either decreasing the performance of more risky procedures (eg, trauma surgery) or avoiding complex cases or patients perceived as more likely to sue. Defensive medicine was highly correlated with physicians’ lack of confidence in their liability insurance or its cost.5

Kessler et al looked at physician supply from 1985–2001 and its correlates to state tort reforms during that time. Three years after States that adopted direct reforms (mainly caps on damage awards) showed an average physician growth rate within 3 years that was 3.3% greater than states not adopting such reforms. The authors controlled for a variety of factors that can influence physician supply including population growth and other state-level characteristics.6

Common Good proposal

Another approach is advocated by Common Good, a bipartisan legal reform coalition. This organization has funding from the RWJ Foundation to work with researchers from the Harvard School of Public Health to investigate the creation of special health courts to hear malpractice cases.11 Their ideas are incorporated into the Fair and Reliable Medical Justice Act introduced as S.1337 by Senators Mike Enzi (R-WY) Max Baucus (D-MT).11

How it would work. Health courts would have full-time judges, neutral medical experts, faster proceedings with legal fees held to 20%, and rulings that could be appealed to a new Medical Appellate Court. Like other administrative courts that handle tax disputes, workmen’s comp, and vaccine injury, there would be no juries. Judges would issue written rulings and establish legal precedents. Once a mistake was verified, recovery would be automatic. Patients would be reimbursed for all their medical expenses and lost income plus a fixed sum that would be determined from an expert derived schedule addressing specific types of injuries.

Strengths and weaknesses. This proposal has the support of a wide array of national medical and legal leaders but not any medical associations. It attempts to address some of the most egregious parts of the current system—the time it takes to get claims resolved, the many errors that go uncompensated, and the diversion of so many dollars to overhead and legal fees rather than to patients. On the other hand, the plan does not provide firm caps, which may make the AMA and other professional associations skeptical. And the proposed health courts would rely on select medical experts and judges, a system likely to be strongly opposed by trial lawyers and some consumer groups. It also does not directly address the prevention of patient errors.

Those who fail to learn from history…

The current malpractice crisis may be abating, leaving physicians with higher malpractice premiums but some state tort reforms. History, however, suggests that the insurance cycle will eventually lead to another crisis. There may be a window of opportunity now to come up with a completely different system to address the goals and problems with our current system, but it is likely to be a small window. Capitalizing on it will require a willingness for both sides in the current stand-off to get past their own self-interests in order to come up with something better for all.

CORRESPONDENCE

Eric A. Henley, MD, MPH, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Illinois College of Medicine at Rockford, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107-1897. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Thorpe K. The Medical malpractice “crisis”: Recent trends and the impact of state tort reforms. Health Affairs 2004 January 21;web-only.

2. Rodwin M, Chang H, Clausen J. Malpractice premiums and physicians’ income: Perceptions of a crisis conflict with empirical evidence. Health Affairs 2006;525:750-758.

3. Studdert D, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2024-2033.

4. Guirguis-Blake J, Fryer GE, Phillips RL, Jr, Szabat R, Green LA. The US medical liability system: Evidence for legislative reform. Ann Fam Med 2006;4:240-246.

5. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA 2005;293:2609-2617.

6. Kessler DP, Sage WM, Becker DJ, et al. Impact of malpractice reforms on the supply of physician services. JAMA 2005;293:2618-2625.

7. Hellinger F, Encinosa W. The impact of state laws limiting malpractice damage awards on health care expenditures. AJPH 2006;96:1375-1381.

8. American Medical Association. Medical liability talking points. Available at: www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/399/mlr_fastfacts.pdf. Accessed on August 15, 2006.

9. Clinton HR, Obama B. Making patient safety the centerpiece of medical liability reform. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2205-2208.

10. O’Reilly K. Harvard adopts a disclosure and apology policy. AMA News, June 12, 2006.

11. Common Good. What are health courts? Available at: cgood.org/f-healthcourtsinfo.html. Accessed on August 15, 2006.

1. Thorpe K. The Medical malpractice “crisis”: Recent trends and the impact of state tort reforms. Health Affairs 2004 January 21;web-only.

2. Rodwin M, Chang H, Clausen J. Malpractice premiums and physicians’ income: Perceptions of a crisis conflict with empirical evidence. Health Affairs 2006;525:750-758.

3. Studdert D, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2024-2033.

4. Guirguis-Blake J, Fryer GE, Phillips RL, Jr, Szabat R, Green LA. The US medical liability system: Evidence for legislative reform. Ann Fam Med 2006;4:240-246.

5. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA 2005;293:2609-2617.

6. Kessler DP, Sage WM, Becker DJ, et al. Impact of malpractice reforms on the supply of physician services. JAMA 2005;293:2618-2625.

7. Hellinger F, Encinosa W. The impact of state laws limiting malpractice damage awards on health care expenditures. AJPH 2006;96:1375-1381.

8. American Medical Association. Medical liability talking points. Available at: www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/399/mlr_fastfacts.pdf. Accessed on August 15, 2006.

9. Clinton HR, Obama B. Making patient safety the centerpiece of medical liability reform. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2205-2208.

10. O’Reilly K. Harvard adopts a disclosure and apology policy. AMA News, June 12, 2006.

11. Common Good. What are health courts? Available at: cgood.org/f-healthcourtsinfo.html. Accessed on August 15, 2006.

The Journal of Family Practice ©2006 Dowden Health Media

Malpractice crisis: Causes of escalating insurance premiums, and implications for you

What has led to the current malpractice crisis? There are 2 main theories.

Physicians, insurers, and hospitals generally blame lawyers and the litigation system for increasing the number of claims filed (claim frequency) and the average payout on claims (claims severity).

Attorneys and consumer groups argue that malpractice insurance goes through natural cycles in costs and charges. For the rise in premiums in the current crisis, they particularly blame decreased investment returns and poor pricing decisions by insurers.

Who’s right?

Research suggests that neither argument alone is persuasive. For instance, a study of the National Practitioner Data Bank, which collects results of all malpractice claims payments, found that claims severity did increase since 1991, but not during the current malpractice crisis period when adjusted for inflation: 52% from 1991 to 2003 but only 6% from 2000 to 2003.1 The highest growth rate has been in medium-sized awards, not the large ones you often read about. And, as always, claims severity growth varies among states (FIGURE 1).1

In contrast, when adjusted for population changes, Data Bank studies showed no significant nationwide increase in the number of paid claims from 1991 to 2003. Data from individual states also bear this out.1

Furthermore, studies of the relationship between claims’ payments and premiums have shown only a weakly positive relationship, suggesting other factors are involved. The argument that decreased investment returns have led to large price increases probably has some merit but does not explain the magnitude of the changes or the variation across states.

FIGURE 1

Amount of average paid claim, 1991-2003

So, what’s the answer for physicians?

Most likely, a combination of several changes has led to the recent crisis—increased claims’ costs, poor pricing decisions or cost projections by insurers, and decreased investment income. Rather than seeing these issues as distinct, it may be more useful to see their intrinsic relationships in leading to rapid premium increases and a malpractice crisis.

In this article, the first of 2, I discuss recent events influencing insurance premiums, which may also suggest to you avenues to explore in optimizing your own coverage. In part 2, I will address our current tort system and concrete proposals for change being pursued.

How premiums are determined

Almost all physicians carry professional liability (malpractice) insurance, either by choice or legal requirement. Coverage is usually purchased individually or by group from a commercial company or a physician-owned mutual company. Hospitals may purchase insurance or be self-insured, and their physician employees may be covered through those policies.

In theory, a tort system to resolve malpractice claims is supposed to serve as a negative incentive to physicians to practice high quality medicine. But the 1999 Institute of Medicine report on the occurrence and ramifications of medical errors, To Err is Human,2 provided evidence that the malpractice system has failed to accomplish this goal.