User login

In November 2003, President Bush signed the Medicare prescription-drug bill, which will usher in the largest change in the Medicare program in terms of money and number of people affected since the program’s creation in 1965. The final version of the bill was controversial, passing by a small margin in both the House and Senate.

Conservatives criticized the bill for not giving a large enough role to the private sector as an alternative to the traditional Medicare program, for spending too much money, and for risking even larger budget deficits than already predicted.

Liberals criticized it for providing an inadequate drug benefit, for allowing the prescription program to be run by private industry, and for creating an experimental private-sector program that will compete with traditional Medicare.

In the end, passage was ensured with support from the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP), drug companies, private health insurers, and national medical groups—and with the usual political maneuvering.

Public support among seniors and other groups remains unclear. For example, the American Academy of Family Physicians supported the bill, but negative reaction by members led President Michael Fleming to write a letter explaining the reasons for the decision (www.aafp.org/medicareletter.xml). In addition, Republican concerns about the overall cost of the legislation seem borne out by the administration’s recent announcement projecting costs of $530 billion over 10 years, about one third more than the price tag used to convince Congress to pass the legislation about 2 months before.

This article reviews the bill and some of its health policy implications.

Not all details clear; more than drug benefits affected

Several generalizations about Federal legislation hold true with this bill.

First, while the bill establishes the intent of Congress, a number of details will not be made clear until it is implemented by the executive branch—the administration and the responsible cabinet departments such as the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The importance of these implementation details is most relevant to the prescription drug benefit section of the bill.

Second, the bill changes or adds programs in a number of health areas besides prescription drugs (see Supplementary changes with the Medicare prescription drug bill). These additions partly reflected the need of proponents to satisfy diverse special interests (private insurers, hospitals and physicians, rural areas) and thereby gain their support for other parts of the bill that were more controversial, principally the drug benefit and private competition for Medicare. Thus, there is funding to increase Medicare payments to physicians and rural hospitals and to hospitals serving large numbers of low-income patients.

- Medicare payments to rural hospitals and doctors increase by $25 billion over 10 years.

- Payments to hospitals serving large numbers of low-income patients would increase.

- Hospitals can avoid some future cuts in Medicare payments by submitting quality of care data to the government.

- Doctors would receive increases of 1.5% per year in Medicare payments for 2004 and 2005 rather than the cuts currently planned.

- Medicare would cover an initial physical for new beneficiaries and screening for diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

- Support for development of health savings accounts that allow people with high-deductible health insurance to shelter income from taxes and obtain tax deductions if the money is used for health expenses.

- Home health agencies would see cuts in payments, but patient co-pays would not be required.

- Medicare Part B premiums (for physician and outpatient services) would be greater for those with incomes over $80,000.

Third, the changes also reflect genuine goals of improving health by expanding Medicare coverage of preventive services and requiring participating hospitals to submit quality-of-care data.

Prescription drug coverage under the new bill

Although many seniors have drug coverage through retirement health plans or Medigap policies purchased privately, about one quarter of beneficiaries (some 10 million people) do not have such coverage. Even those with drug coverage may have difficulty affording recommended medications since the median income for a senior is little more than $23,000. Many physicians have seen the ill effects of seniors not filling their prescriptions or skipping doses of prescribed medications.

Until the benefit takes effect. The actual prescription drug benefit will not begin until 2006. Until then, Medicare recipients will be given the option of purchasing a drug-discount card for $30 per year starting this spring. It is estimated these cards may save 10% to 15% of prescription costs. In addition, low-income seniors will receive $600 per year toward drug purchases.

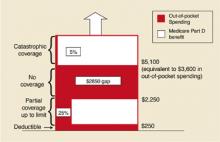

After it takes effect. The drug benefit starting in 2006 will be funded through a complex arrangement of patient and government payments (Figure).

- Premium: A premium estimated to begin at $35 per month.

- Deductible: An annual deductible starting at $250 and indexed to increase to $445 in 2013.

- Co-pay: After paying the deductible, enrollees will pay 25% of additional drug costs up to $2250, at which point a $2850 gap in cover-age—the so-called “doughut hole”—leaves the onus of payment with the patient until $5100 is reached.

- Catastrophic coverage: After $5100, patients will pay 5% of any additional annual drug costs.

In 2006, catastrophic coverage will begin after $3600 in out-of-pocket costs ($250 deductible + $500 in co-pays to $2250 + the $2850 doughnut gap), not counting the premium. Indexing provisions are projected to raise this out-of-pocket cost requirement to $6400 in 2013. These indexing features have received less attention in the media, but may become increasingly important to seniors. For lower-income individuals, as determined by specific yearly income and total assets guidelines, a small per-prescription fee will replace the premium, deductible, and doughnut hole gap payments.

Coverage will vary. As the yearly cost of drugs changes, so will the relative contributions made by the patient and the government (Table). The new bill provides substantial benefit to those with catastrophic drug costs and to very low-income seniors. The idea of linking payments to income (for the drug benefit and the Part B premium) is a change in the Medicare program, as it has traditionally provided the same benefit to all beneficiaries, regardless of income.

Expected effects of privatization. The manner in which the drug benefit will be administered was controversial in Congress. The legislation, written primarily by Republicans, provides that beneficiaries can obtain coverage by participating with an HMO or PPO or by purchasing standalone coverage through a private prescription drug insurance program. Patient enrollment is voluntary. Managed care plans would be encouraged to participate in the prescription benefit program through eligibility for government subsidies. In turn, more beneficiaries would be encouraged to choose managed care plans, thus decreasing the number of patients covered by traditional Medicare. Furthermore, current private Medigap supplemental plans will be barred from offering drug benefits.

With the HMO/PPO and stand-alone programs, it is likely that any reduction in drug costs will result from private pharmacy benefit managers negotiating discounts from drug companies as they do now for many employer-sponsored plans. Presumably, formularies will vary from plan to plan, and it may be difficult for patients to know ahead of time whether the plan they join will cover their current medications. The legislation prohibits the government from using its vast purchasing power to negotiate substantial discounts from drug companies as it does now for the Medicaid program. There are provisions to increase availability of generic drugs, but importation of drugs from Canada is prohibited unless FDA approval is given (so far, the FDA has opposed this). Many Democrats who opposed the bill argued that it allowed too large a role for the private sector and constrained the ability of the government to control drug costs.

A final controversial measure in the bill provided for conducting an experiment in 6 cities beginning in 2010, in which at least 1 private insurance plan would be funded to compete directly with the traditional Medicare program. Many Republicans believe this type of competition is necessary to decrease the rate of cost increases in the Medicare program, while many Democrats believe the private market is a big reason for increasing problems with the quality and cost of the entire health care system.

FIGURE

Out-of-pocket spending under new legislation

Out-of-pocket drug spending in 2006 for Medicare beneficiaries under new Medicare legislation. Note: Benefit levels are indexed to growth in per capita expenditures for covered Part D drugs. As a result, the Part D deductible in projected to increase from $250 in 2006 to $445 in 2013; the catastrophic threshold is projected to increase from $5100 in 2006 to $9066 in 2013. From the Kaiser Family Foundation website(www.kff.org/medicare/medicarebenefitataglance.ctm).

Looming questions

The new Medicare legislation is vast in scope, cost, and controversy. In the coming months, a number of organizations—AARP, the Department of Health and Human Services, and various foundations—will attempt to explain its provisions to the public, most likely in different ways.

TABLE

Deciphering the 2006 drug benefit

The chart above shows what portion of yearly drug costs would be paid by the Medicare recipient and what portion would be paid by Medicare beginning in 2006. It does not include the $420 yearly premium.Family physicians may be asked by patients to explain provisions of the program and to offer advice in making decisions about their participation.

In addition, preoccupation with explaining and implementing the Medicare bill may keep Congress and the President from addressing other pressing health issues such as the growing number of uninsured.

Corresponding author

Eric Henley, MD, MPH, Co-Editor, Practice Alert, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Pear R. Bush’s aides put higher price tag on Medicare law. New York Times, January 30, 2004.

2. Altman D. The new Medicare prescription-drug legislation. N Engl J Med 2004;350:9-10

3. American Academy of Family Physicians. Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act. Available at: www.aafp.org/x25558.xml. Accessed on April 2, 2004.

4. National Association of Chain Drug Stores. Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit and Discount Card Program Q & A. Available at: www.nacds.org/user-assets/PDF_files/MedicareRx_Q&A.pdf. Accessed on April 2, 2004.

5. New Medicare law/key provisions. Christian Science Monitor, December 4, 2003

In November 2003, President Bush signed the Medicare prescription-drug bill, which will usher in the largest change in the Medicare program in terms of money and number of people affected since the program’s creation in 1965. The final version of the bill was controversial, passing by a small margin in both the House and Senate.

Conservatives criticized the bill for not giving a large enough role to the private sector as an alternative to the traditional Medicare program, for spending too much money, and for risking even larger budget deficits than already predicted.

Liberals criticized it for providing an inadequate drug benefit, for allowing the prescription program to be run by private industry, and for creating an experimental private-sector program that will compete with traditional Medicare.

In the end, passage was ensured with support from the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP), drug companies, private health insurers, and national medical groups—and with the usual political maneuvering.

Public support among seniors and other groups remains unclear. For example, the American Academy of Family Physicians supported the bill, but negative reaction by members led President Michael Fleming to write a letter explaining the reasons for the decision (www.aafp.org/medicareletter.xml). In addition, Republican concerns about the overall cost of the legislation seem borne out by the administration’s recent announcement projecting costs of $530 billion over 10 years, about one third more than the price tag used to convince Congress to pass the legislation about 2 months before.

This article reviews the bill and some of its health policy implications.

Not all details clear; more than drug benefits affected

Several generalizations about Federal legislation hold true with this bill.

First, while the bill establishes the intent of Congress, a number of details will not be made clear until it is implemented by the executive branch—the administration and the responsible cabinet departments such as the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The importance of these implementation details is most relevant to the prescription drug benefit section of the bill.

Second, the bill changes or adds programs in a number of health areas besides prescription drugs (see Supplementary changes with the Medicare prescription drug bill). These additions partly reflected the need of proponents to satisfy diverse special interests (private insurers, hospitals and physicians, rural areas) and thereby gain their support for other parts of the bill that were more controversial, principally the drug benefit and private competition for Medicare. Thus, there is funding to increase Medicare payments to physicians and rural hospitals and to hospitals serving large numbers of low-income patients.

- Medicare payments to rural hospitals and doctors increase by $25 billion over 10 years.

- Payments to hospitals serving large numbers of low-income patients would increase.

- Hospitals can avoid some future cuts in Medicare payments by submitting quality of care data to the government.

- Doctors would receive increases of 1.5% per year in Medicare payments for 2004 and 2005 rather than the cuts currently planned.

- Medicare would cover an initial physical for new beneficiaries and screening for diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

- Support for development of health savings accounts that allow people with high-deductible health insurance to shelter income from taxes and obtain tax deductions if the money is used for health expenses.

- Home health agencies would see cuts in payments, but patient co-pays would not be required.

- Medicare Part B premiums (for physician and outpatient services) would be greater for those with incomes over $80,000.

Third, the changes also reflect genuine goals of improving health by expanding Medicare coverage of preventive services and requiring participating hospitals to submit quality-of-care data.

Prescription drug coverage under the new bill

Although many seniors have drug coverage through retirement health plans or Medigap policies purchased privately, about one quarter of beneficiaries (some 10 million people) do not have such coverage. Even those with drug coverage may have difficulty affording recommended medications since the median income for a senior is little more than $23,000. Many physicians have seen the ill effects of seniors not filling their prescriptions or skipping doses of prescribed medications.

Until the benefit takes effect. The actual prescription drug benefit will not begin until 2006. Until then, Medicare recipients will be given the option of purchasing a drug-discount card for $30 per year starting this spring. It is estimated these cards may save 10% to 15% of prescription costs. In addition, low-income seniors will receive $600 per year toward drug purchases.

After it takes effect. The drug benefit starting in 2006 will be funded through a complex arrangement of patient and government payments (Figure).

- Premium: A premium estimated to begin at $35 per month.

- Deductible: An annual deductible starting at $250 and indexed to increase to $445 in 2013.

- Co-pay: After paying the deductible, enrollees will pay 25% of additional drug costs up to $2250, at which point a $2850 gap in cover-age—the so-called “doughut hole”—leaves the onus of payment with the patient until $5100 is reached.

- Catastrophic coverage: After $5100, patients will pay 5% of any additional annual drug costs.

In 2006, catastrophic coverage will begin after $3600 in out-of-pocket costs ($250 deductible + $500 in co-pays to $2250 + the $2850 doughnut gap), not counting the premium. Indexing provisions are projected to raise this out-of-pocket cost requirement to $6400 in 2013. These indexing features have received less attention in the media, but may become increasingly important to seniors. For lower-income individuals, as determined by specific yearly income and total assets guidelines, a small per-prescription fee will replace the premium, deductible, and doughnut hole gap payments.

Coverage will vary. As the yearly cost of drugs changes, so will the relative contributions made by the patient and the government (Table). The new bill provides substantial benefit to those with catastrophic drug costs and to very low-income seniors. The idea of linking payments to income (for the drug benefit and the Part B premium) is a change in the Medicare program, as it has traditionally provided the same benefit to all beneficiaries, regardless of income.

Expected effects of privatization. The manner in which the drug benefit will be administered was controversial in Congress. The legislation, written primarily by Republicans, provides that beneficiaries can obtain coverage by participating with an HMO or PPO or by purchasing standalone coverage through a private prescription drug insurance program. Patient enrollment is voluntary. Managed care plans would be encouraged to participate in the prescription benefit program through eligibility for government subsidies. In turn, more beneficiaries would be encouraged to choose managed care plans, thus decreasing the number of patients covered by traditional Medicare. Furthermore, current private Medigap supplemental plans will be barred from offering drug benefits.

With the HMO/PPO and stand-alone programs, it is likely that any reduction in drug costs will result from private pharmacy benefit managers negotiating discounts from drug companies as they do now for many employer-sponsored plans. Presumably, formularies will vary from plan to plan, and it may be difficult for patients to know ahead of time whether the plan they join will cover their current medications. The legislation prohibits the government from using its vast purchasing power to negotiate substantial discounts from drug companies as it does now for the Medicaid program. There are provisions to increase availability of generic drugs, but importation of drugs from Canada is prohibited unless FDA approval is given (so far, the FDA has opposed this). Many Democrats who opposed the bill argued that it allowed too large a role for the private sector and constrained the ability of the government to control drug costs.

A final controversial measure in the bill provided for conducting an experiment in 6 cities beginning in 2010, in which at least 1 private insurance plan would be funded to compete directly with the traditional Medicare program. Many Republicans believe this type of competition is necessary to decrease the rate of cost increases in the Medicare program, while many Democrats believe the private market is a big reason for increasing problems with the quality and cost of the entire health care system.

FIGURE

Out-of-pocket spending under new legislation

Out-of-pocket drug spending in 2006 for Medicare beneficiaries under new Medicare legislation. Note: Benefit levels are indexed to growth in per capita expenditures for covered Part D drugs. As a result, the Part D deductible in projected to increase from $250 in 2006 to $445 in 2013; the catastrophic threshold is projected to increase from $5100 in 2006 to $9066 in 2013. From the Kaiser Family Foundation website(www.kff.org/medicare/medicarebenefitataglance.ctm).

Looming questions

The new Medicare legislation is vast in scope, cost, and controversy. In the coming months, a number of organizations—AARP, the Department of Health and Human Services, and various foundations—will attempt to explain its provisions to the public, most likely in different ways.

TABLE

Deciphering the 2006 drug benefit

The chart above shows what portion of yearly drug costs would be paid by the Medicare recipient and what portion would be paid by Medicare beginning in 2006. It does not include the $420 yearly premium.Family physicians may be asked by patients to explain provisions of the program and to offer advice in making decisions about their participation.

In addition, preoccupation with explaining and implementing the Medicare bill may keep Congress and the President from addressing other pressing health issues such as the growing number of uninsured.

Corresponding author

Eric Henley, MD, MPH, Co-Editor, Practice Alert, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107. E-mail: [email protected].

In November 2003, President Bush signed the Medicare prescription-drug bill, which will usher in the largest change in the Medicare program in terms of money and number of people affected since the program’s creation in 1965. The final version of the bill was controversial, passing by a small margin in both the House and Senate.

Conservatives criticized the bill for not giving a large enough role to the private sector as an alternative to the traditional Medicare program, for spending too much money, and for risking even larger budget deficits than already predicted.

Liberals criticized it for providing an inadequate drug benefit, for allowing the prescription program to be run by private industry, and for creating an experimental private-sector program that will compete with traditional Medicare.

In the end, passage was ensured with support from the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP), drug companies, private health insurers, and national medical groups—and with the usual political maneuvering.

Public support among seniors and other groups remains unclear. For example, the American Academy of Family Physicians supported the bill, but negative reaction by members led President Michael Fleming to write a letter explaining the reasons for the decision (www.aafp.org/medicareletter.xml). In addition, Republican concerns about the overall cost of the legislation seem borne out by the administration’s recent announcement projecting costs of $530 billion over 10 years, about one third more than the price tag used to convince Congress to pass the legislation about 2 months before.

This article reviews the bill and some of its health policy implications.

Not all details clear; more than drug benefits affected

Several generalizations about Federal legislation hold true with this bill.

First, while the bill establishes the intent of Congress, a number of details will not be made clear until it is implemented by the executive branch—the administration and the responsible cabinet departments such as the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The importance of these implementation details is most relevant to the prescription drug benefit section of the bill.

Second, the bill changes or adds programs in a number of health areas besides prescription drugs (see Supplementary changes with the Medicare prescription drug bill). These additions partly reflected the need of proponents to satisfy diverse special interests (private insurers, hospitals and physicians, rural areas) and thereby gain their support for other parts of the bill that were more controversial, principally the drug benefit and private competition for Medicare. Thus, there is funding to increase Medicare payments to physicians and rural hospitals and to hospitals serving large numbers of low-income patients.

- Medicare payments to rural hospitals and doctors increase by $25 billion over 10 years.

- Payments to hospitals serving large numbers of low-income patients would increase.

- Hospitals can avoid some future cuts in Medicare payments by submitting quality of care data to the government.

- Doctors would receive increases of 1.5% per year in Medicare payments for 2004 and 2005 rather than the cuts currently planned.

- Medicare would cover an initial physical for new beneficiaries and screening for diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

- Support for development of health savings accounts that allow people with high-deductible health insurance to shelter income from taxes and obtain tax deductions if the money is used for health expenses.

- Home health agencies would see cuts in payments, but patient co-pays would not be required.

- Medicare Part B premiums (for physician and outpatient services) would be greater for those with incomes over $80,000.

Third, the changes also reflect genuine goals of improving health by expanding Medicare coverage of preventive services and requiring participating hospitals to submit quality-of-care data.

Prescription drug coverage under the new bill

Although many seniors have drug coverage through retirement health plans or Medigap policies purchased privately, about one quarter of beneficiaries (some 10 million people) do not have such coverage. Even those with drug coverage may have difficulty affording recommended medications since the median income for a senior is little more than $23,000. Many physicians have seen the ill effects of seniors not filling their prescriptions or skipping doses of prescribed medications.

Until the benefit takes effect. The actual prescription drug benefit will not begin until 2006. Until then, Medicare recipients will be given the option of purchasing a drug-discount card for $30 per year starting this spring. It is estimated these cards may save 10% to 15% of prescription costs. In addition, low-income seniors will receive $600 per year toward drug purchases.

After it takes effect. The drug benefit starting in 2006 will be funded through a complex arrangement of patient and government payments (Figure).

- Premium: A premium estimated to begin at $35 per month.

- Deductible: An annual deductible starting at $250 and indexed to increase to $445 in 2013.

- Co-pay: After paying the deductible, enrollees will pay 25% of additional drug costs up to $2250, at which point a $2850 gap in cover-age—the so-called “doughut hole”—leaves the onus of payment with the patient until $5100 is reached.

- Catastrophic coverage: After $5100, patients will pay 5% of any additional annual drug costs.

In 2006, catastrophic coverage will begin after $3600 in out-of-pocket costs ($250 deductible + $500 in co-pays to $2250 + the $2850 doughnut gap), not counting the premium. Indexing provisions are projected to raise this out-of-pocket cost requirement to $6400 in 2013. These indexing features have received less attention in the media, but may become increasingly important to seniors. For lower-income individuals, as determined by specific yearly income and total assets guidelines, a small per-prescription fee will replace the premium, deductible, and doughnut hole gap payments.

Coverage will vary. As the yearly cost of drugs changes, so will the relative contributions made by the patient and the government (Table). The new bill provides substantial benefit to those with catastrophic drug costs and to very low-income seniors. The idea of linking payments to income (for the drug benefit and the Part B premium) is a change in the Medicare program, as it has traditionally provided the same benefit to all beneficiaries, regardless of income.

Expected effects of privatization. The manner in which the drug benefit will be administered was controversial in Congress. The legislation, written primarily by Republicans, provides that beneficiaries can obtain coverage by participating with an HMO or PPO or by purchasing standalone coverage through a private prescription drug insurance program. Patient enrollment is voluntary. Managed care plans would be encouraged to participate in the prescription benefit program through eligibility for government subsidies. In turn, more beneficiaries would be encouraged to choose managed care plans, thus decreasing the number of patients covered by traditional Medicare. Furthermore, current private Medigap supplemental plans will be barred from offering drug benefits.

With the HMO/PPO and stand-alone programs, it is likely that any reduction in drug costs will result from private pharmacy benefit managers negotiating discounts from drug companies as they do now for many employer-sponsored plans. Presumably, formularies will vary from plan to plan, and it may be difficult for patients to know ahead of time whether the plan they join will cover their current medications. The legislation prohibits the government from using its vast purchasing power to negotiate substantial discounts from drug companies as it does now for the Medicaid program. There are provisions to increase availability of generic drugs, but importation of drugs from Canada is prohibited unless FDA approval is given (so far, the FDA has opposed this). Many Democrats who opposed the bill argued that it allowed too large a role for the private sector and constrained the ability of the government to control drug costs.

A final controversial measure in the bill provided for conducting an experiment in 6 cities beginning in 2010, in which at least 1 private insurance plan would be funded to compete directly with the traditional Medicare program. Many Republicans believe this type of competition is necessary to decrease the rate of cost increases in the Medicare program, while many Democrats believe the private market is a big reason for increasing problems with the quality and cost of the entire health care system.

FIGURE

Out-of-pocket spending under new legislation

Out-of-pocket drug spending in 2006 for Medicare beneficiaries under new Medicare legislation. Note: Benefit levels are indexed to growth in per capita expenditures for covered Part D drugs. As a result, the Part D deductible in projected to increase from $250 in 2006 to $445 in 2013; the catastrophic threshold is projected to increase from $5100 in 2006 to $9066 in 2013. From the Kaiser Family Foundation website(www.kff.org/medicare/medicarebenefitataglance.ctm).

Looming questions

The new Medicare legislation is vast in scope, cost, and controversy. In the coming months, a number of organizations—AARP, the Department of Health and Human Services, and various foundations—will attempt to explain its provisions to the public, most likely in different ways.

TABLE

Deciphering the 2006 drug benefit

The chart above shows what portion of yearly drug costs would be paid by the Medicare recipient and what portion would be paid by Medicare beginning in 2006. It does not include the $420 yearly premium.Family physicians may be asked by patients to explain provisions of the program and to offer advice in making decisions about their participation.

In addition, preoccupation with explaining and implementing the Medicare bill may keep Congress and the President from addressing other pressing health issues such as the growing number of uninsured.

Corresponding author

Eric Henley, MD, MPH, Co-Editor, Practice Alert, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Pear R. Bush’s aides put higher price tag on Medicare law. New York Times, January 30, 2004.

2. Altman D. The new Medicare prescription-drug legislation. N Engl J Med 2004;350:9-10

3. American Academy of Family Physicians. Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act. Available at: www.aafp.org/x25558.xml. Accessed on April 2, 2004.

4. National Association of Chain Drug Stores. Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit and Discount Card Program Q & A. Available at: www.nacds.org/user-assets/PDF_files/MedicareRx_Q&A.pdf. Accessed on April 2, 2004.

5. New Medicare law/key provisions. Christian Science Monitor, December 4, 2003

1. Pear R. Bush’s aides put higher price tag on Medicare law. New York Times, January 30, 2004.

2. Altman D. The new Medicare prescription-drug legislation. N Engl J Med 2004;350:9-10

3. American Academy of Family Physicians. Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act. Available at: www.aafp.org/x25558.xml. Accessed on April 2, 2004.

4. National Association of Chain Drug Stores. Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit and Discount Card Program Q & A. Available at: www.nacds.org/user-assets/PDF_files/MedicareRx_Q&A.pdf. Accessed on April 2, 2004.

5. New Medicare law/key provisions. Christian Science Monitor, December 4, 2003