User login

› Turn first to metformin for pharmacologic treatment of type 2 diabetes. A

› Add a second oral agent (such as a sulfonylurea, thiazolidinedione, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor, or dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor), a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, or basal insulin if metformin at a maximum tolerated dose does not achieve the HbA1c target over 3 months. A

› Progress to bolus mealtime insulin or a GLP-1 agonist to cover postprandial glycemic excursions if HbA1c remains above goal despite an adequate trial of basal insulin. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

The "Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes" guidelines published in 2015 by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) state that metformin is the preferred initial pharmacotherapy for managing type 2 diabetes.1 Metformin, a biguanide, enhances insulin sensitivity in muscle and fat tissue and inhibits hepatic glucose production. Advantages of metformin include the longstanding research supporting its efficacy and safety, an expected decrease in the glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level of 1% to 1.5%, low cost, minimal hypoglycemic risk, and potential reductions in cardiovascular (CV) events due to decreased low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol.1,2

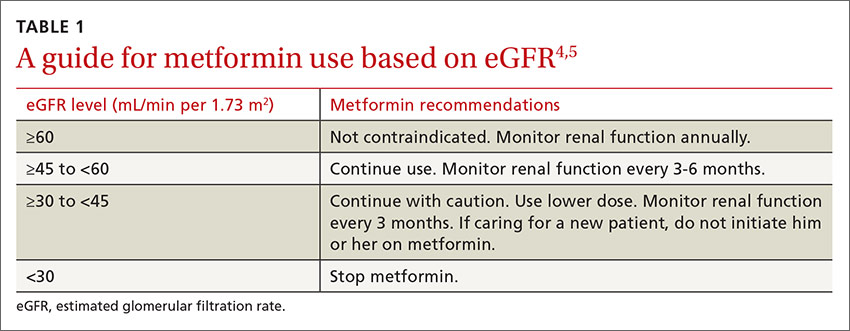

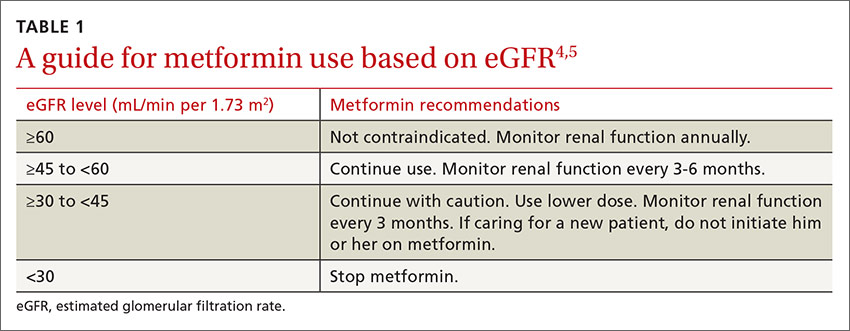

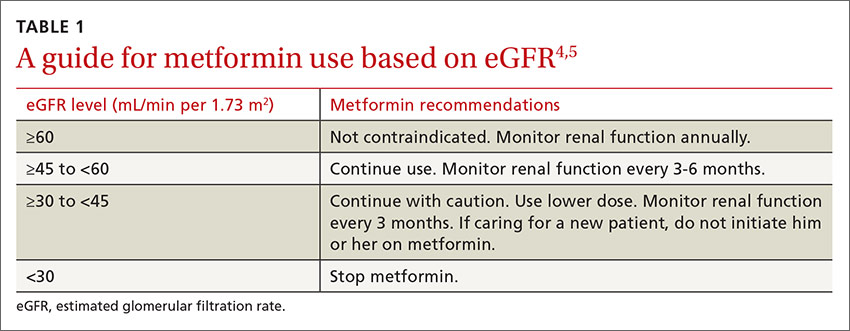

To minimize adverse gastrointestinal effects, start metformin at 500 mg once or twice a day and titrate upward every one to 2 weeks to the target dose.3 To help guide dosing decisions, use the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) instead of the serum creatinine (SCr) level, because the SCr can translate into a variable range of eGFRs (TABLE 1).4,5

What if metformin alone isn't enough?

CASE › Richard C, age 50, has type 2 diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and obesity. He takes metformin 1 g twice a day for his diabetes. After 3 months on this regimen, his HbA1c is 8.8%. How would you manage Mr. C's diabetes going forward?

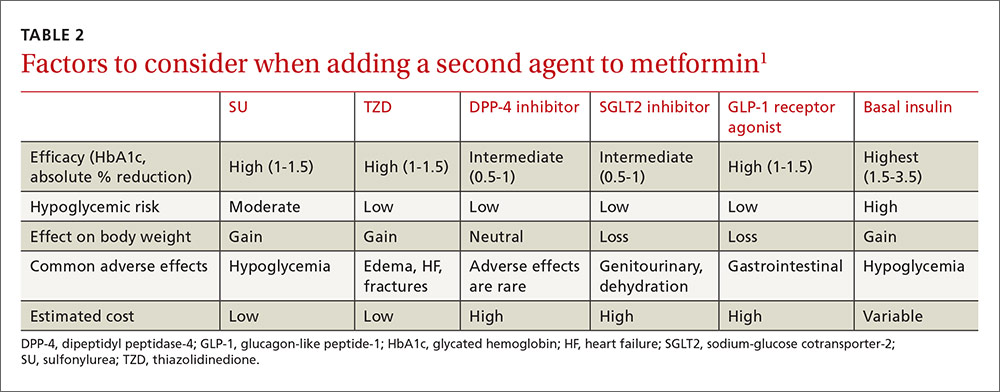

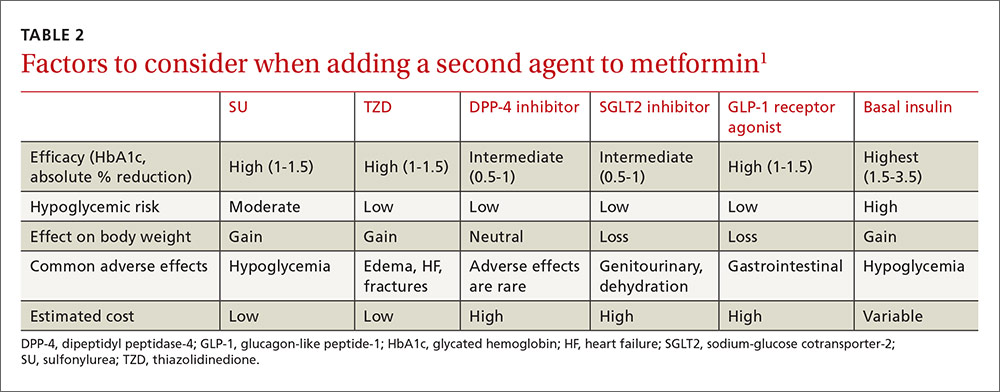

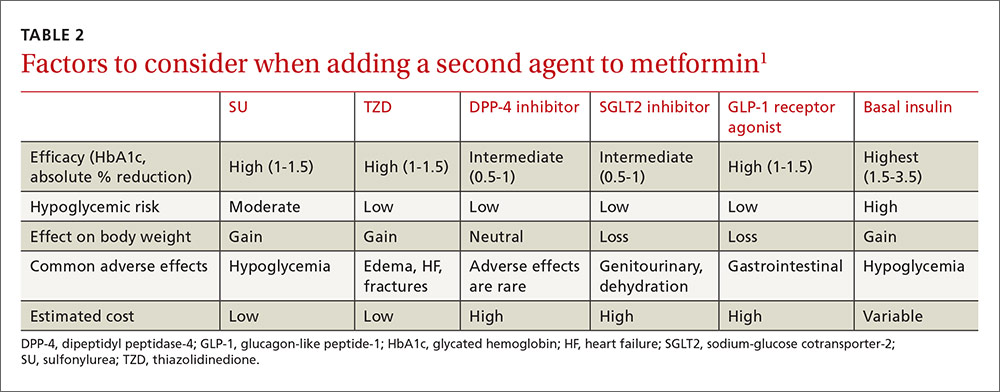

If metformin at a maximum tolerated dose does not achieve the HbA1c target after 3 months, add a second oral agent (a sulfonylurea [SU], thiazolidinedione [TZD], dipeptidyl peptidase 4 [DPP-4] inhibitor, or sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 [SGLT2] inhibitor), a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, or a basal insulin (TABLE 2).1

Factors that will affect the choice of the second agent include patient preference, cost, potential adverse effects, impact on weight, efficacy, and risk of hypoglycemia.

Based on cost, familiarity, and longstanding safety data, you decide to give Mr. C an SU, while cautioning him about hypoglycemia.

CASE › Mr. C has now been taking metformin and an SU at maximum doses for 2 years and continues with lifestyle modifications. Though his HbA1c level dropped after adding the SU, over 2 years it has crept up to 8.6% and his mean blood glucose is 186 mg/dL. What are your treatment options now?

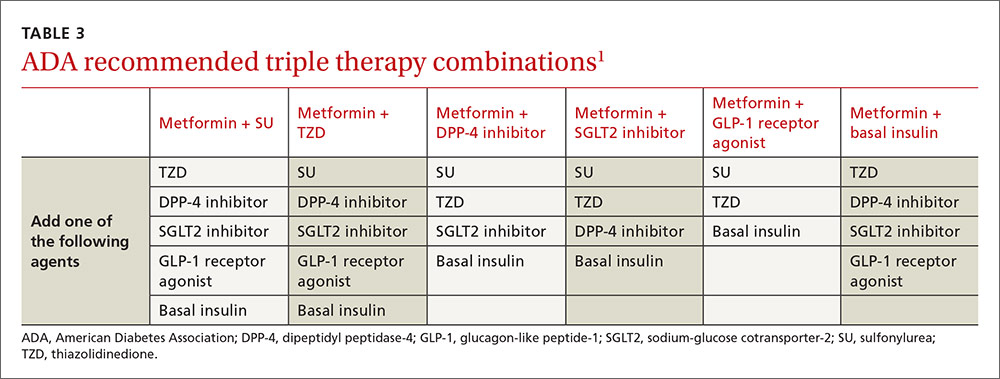

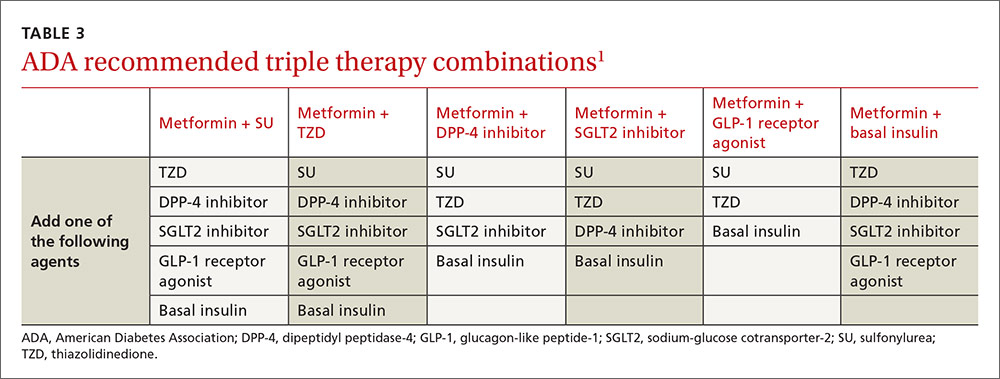

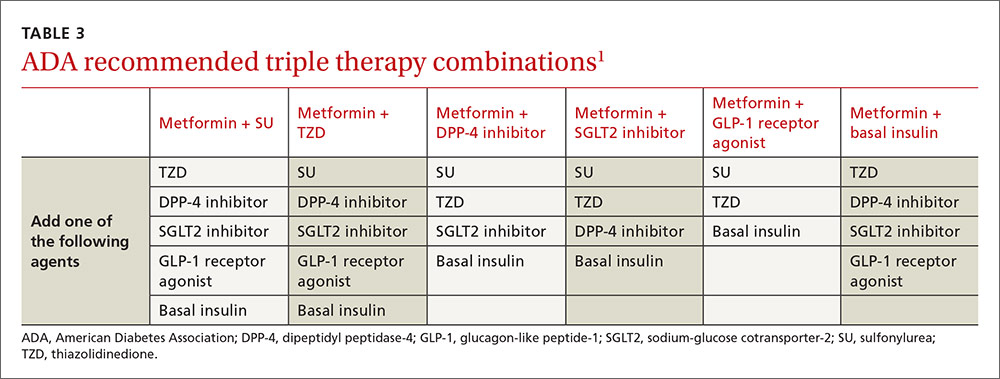

If the target HbA1c level is not achieved on dual therapy, consider triple therapy combinations (TABLE 3).1

In Mr. C's case, a third oral agent could be added, but DPP-4 and SGLT2 are unlikely to get his HbA1c below 7%. TZD may get his HbA1c into the desired range but is associated with adverse effects such as heart failure, edema, and weight gain. Mr. C agrees instead to start a basal insulin in conjunction with metformin. You could continue the SU, but you decide to stop it because the additive effect of these medications increases the risk of hypoglycemia.

CASE › Six months later Mr. C is taking metformin and insulin glargine, a basal insulin, adjusted to a fasting blood glucose of 80 to 130 mg/dL. His HbA1c is still above target at 8.4%, and the mean postprandial blood glucose is 232 mg/dL.

Mr. C is still above target for HbA1c and for postprandial blood glucose (goal: <180 mg/dL), so he needs pharmacotherapy that targets postprandial glucose elevations.1 His fasting blood glucose readings are at goal, so increasing his insulin glargine is not recommended because it could cause hypoglycemia. An oral agent other than SU could be added, but none is potent enough to lower the HbA1c to goal (TABLE 2).1 There are 3 other options:

- add a mealtime bolus of insulin

- add a GLP-1 receptor agonist

- switch to premixed (biphasic) insulin.

What to do when basal insulin isn’t enough—with or without oral medsFor type 2 diabetes poorly controlled on basal insulin with or without oral agents, the 2015 ADA treatment guidelines recommend adding a GLP-1 receptor agonist or mealtime insulin.1 A less desirable alternative is to switch from basal insulin to a twice-daily premixed (biphasic) insulin analog (70/30 aspart mix or 75/25 or 50/50 lispro mix). The human NPH-Regular premixed formulations (70/30) are less costly alternatives. The disadvantage with all premixed insulins is they only cover 2 postprandial glucose elevations a day.1,6,7

Insulin requires multiple daily injections, can lead to weight gain, and carries the risk of hypoglycemia, which causes significant morbidity.8,9 Daily or weekly administration of a GLP-1 receptor agonist combined with basal insulin can offer a more convenient alternative to mealtime boluses of insulin.

What are GLP-1 receptor agonists?

GLP-1 receptor agonists exert their maximum influence on blood glucose levels during the postprandial period by mimicking the body’s natural incretin hormonal response to oral glucose ingestion.10 They delay gastric emptying, promote satiety, decrease glucagon secretion, and increase insulin secretion.10,11 This mechanism blunts the spiking of postprandial blood glucose after a meal and improves blood glucose control and weight reduction.1,6,7

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Eng and colleagues compared the safety and efficacy of combined GLP-1 agonist and basal insulin with other treatment regimens.7 Fifteen randomized controlled trials were included involving 4348 participants with a mean trial duration of 25 weeks.

Compared with all other treatment regimens, the GLP-1 receptor agonist and basal insulin combination not only significantly reduced HbA1c by 0.44% (95% confidence interval [CI], -0.60 to -0.29) and increased the likelihood of attaining an HbA1c of <7.0% (relative risk [RR]=1.92; 95% CI, 1.43 to 2.56) but also reduced weight by 3.22 kg (-4.90 to -1.54) with no increased risk of hypoglycemia (RR=0.99; 0.76 to 1.29).7

GLP-1 agonist vs bolus insulin

Compared with basal-bolus insulin regimens, the combination of a GLP-1 receptor agonist with basal insulin has led to a significantly lowered risk of hypoglycemia (RR=0.67; 95% CI, 0.56 to 0.80), greater weight loss (-5.66 kg; 95% CI, -9.8 to -1.51) and an average reduction in HbA1c of 0.1% (95% CI, -0.17 to -0.02).7

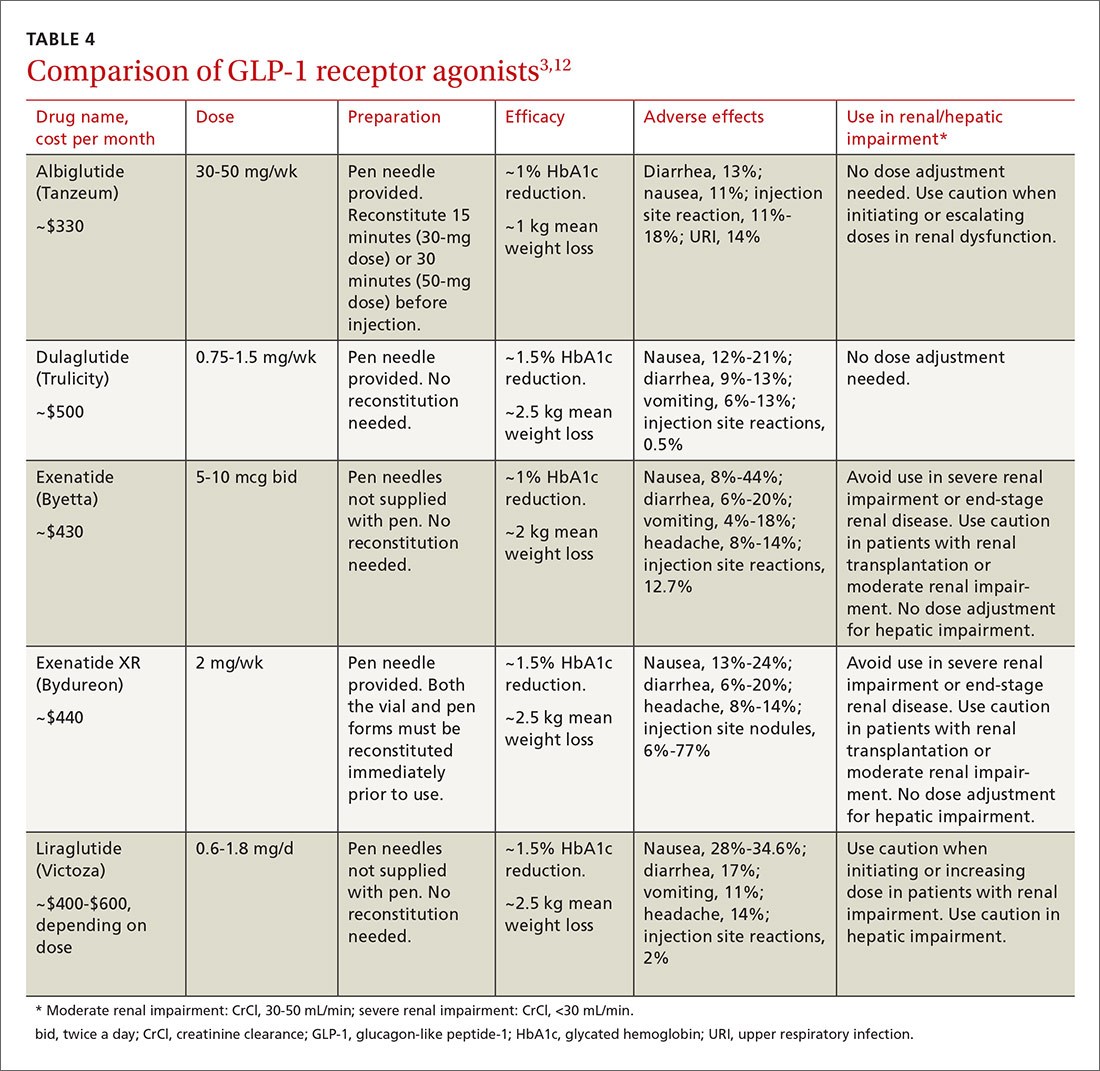

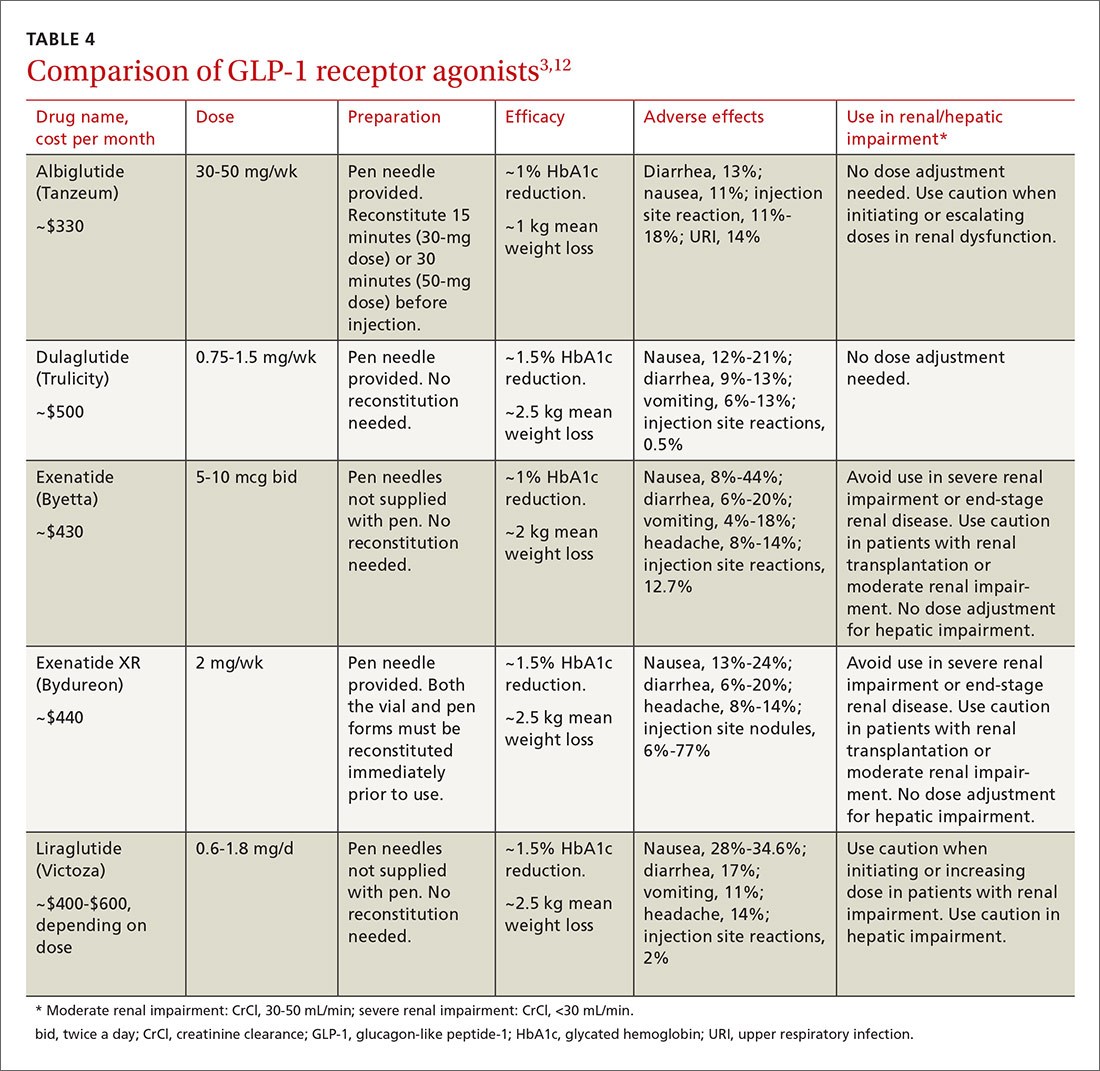

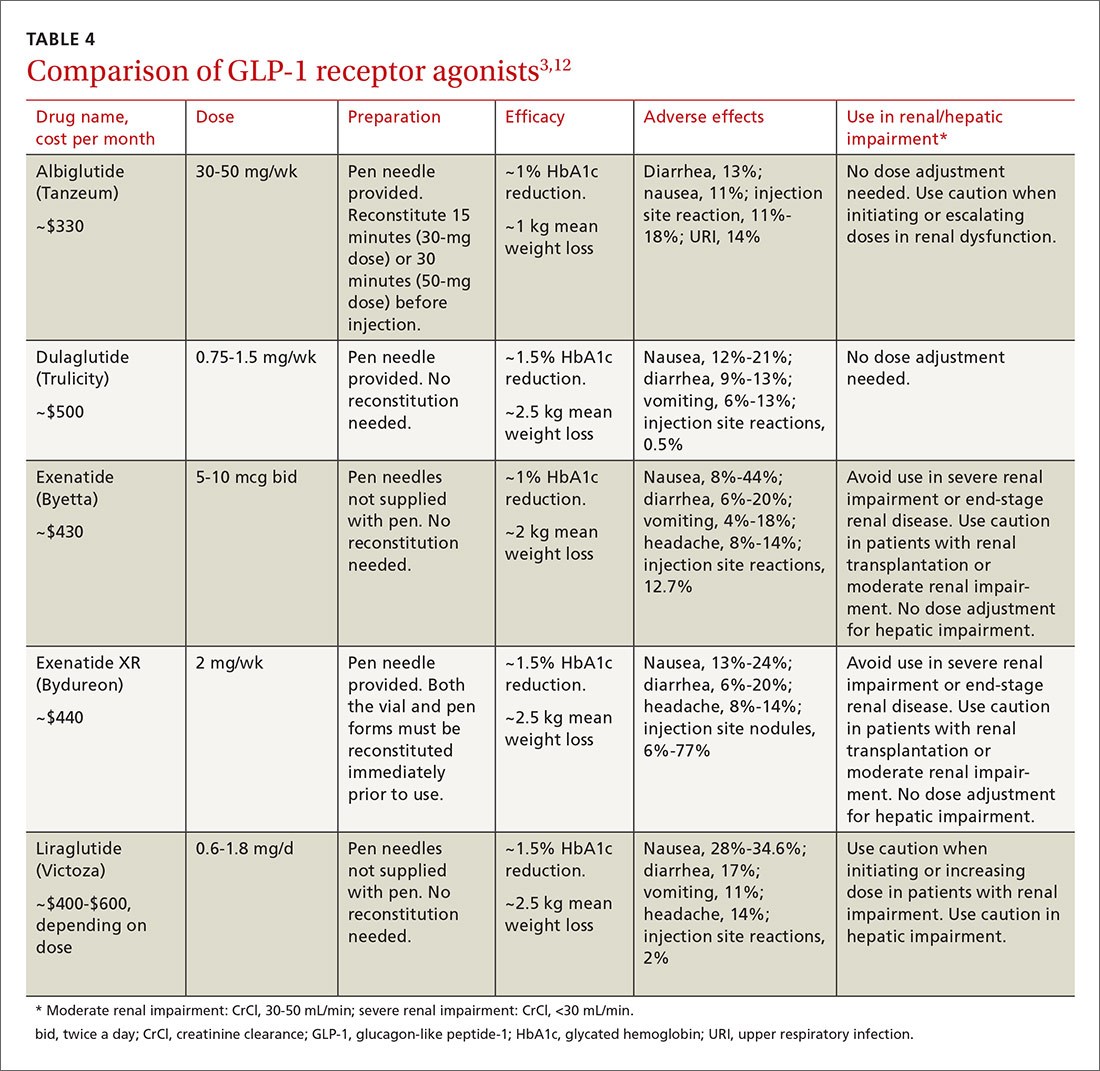

There are 5 GLP-1 receptor agonists that have US Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: albiglutide, dulaglutide, exenatide, exenatide XR, and liraglutide (TABLE 4).3,12

All 5 agents are administered subcutaneously and packaged in pen-injector form. Adverse effects include nausea, which is transient and diminishes within the first few weeks of therapy, and less commonly, pancreatitis.3,12

All of the GLP-1 receptor agonists, except short-acting exenatide, carry a warning about the risk of worsening renal function and a possible association with medullary thyroid carcinomas, which were identified in rats, but have not been observed in humans.3,12 Medications in this drug class have a low risk for precipitating hypoglycemia.11 Cost is their chief disadvantage, although copay reduction cards are available online for most of the products. Evaluate efficacy, ease of use, tolerability, and cost when selecting a GLP-1 receptor agonist.3,12

CASE › Mr. C prefers a more convenient option than adding another daily injection. Given his obesity, a GLP-1 receptor agonist can help with weight loss and lower his risk for hypoglycemia. To further increase the convenience in dosing, you lean toward either weekly exenatide XR or dulaglutide over basal-bolus combination insulin. Weekly albiglutide is less potent than exenatide XR and dulaglutide in decreasing HbA1c.12 Mr. C’s insurance plan provides preferred coverage for exenatide XR and he is eligible for a copay savings card, meaning he will pay no more than $25 per month for this new prescription. You prescribe exenatide XR and ask him to record his postprandial blood glucose levels. You follow up in one month to assess his response.

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Mounsey, MD, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine, 590 Manning Drive, Campus Box 7595, Chapel Hill, NC 27599; [email protected].

1. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes - 2015. Diabetes Care. 2015;38 (Suppl):S1-S94.

2. Bennett WL, Maruthur NM, Singh S, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of medications for type 2 diabetes: an update including new drugs and 2-drug combinations. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:602-613.

3. Merck Manual. Metformin. Available at: http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/appendixes/brand-names-of-some-commonly-used-drugs. Accessed April 18, 2015.

4. Lipska KJ, Bailey CJ, Inzucchi SE. Use of metformin in the setting of mild-to-moderate renal insufficiency. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1431-1437.

5. Philbrick AM, Ernst ME, McDanel DL, et al. Metformin use in renal dysfunction: is a serum creatinine threshold appropriate? Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009;66:2017-2023.

6. Pharmacist’s Letter. Drugs for Type 2 Diabetes [detail document]. September 2015. Available at: http://pharmacistsletter.therapeuticresearch.com/pl/ArticleDD.aspx?nidchk=1&cs=&s=PL&pt=2&segment=4407&dd=280601. Accessed December 28, 2015.

7. Eng C, Kramer CK, Zinman B, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist and basal insulin combination treatment for the management of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2014;384:2228-2234.

8. Inzucchi SE, Burgenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1364-1379.

9. Bonds DE, Miller ME, Bergenstal RM, et al. The association between symptomatic, severe hypoglycaemia and mortality in type 2 diabetes: retrospective epidemiological analysis of the ACCORD study. BMJ. 2010:340:b4909.

10. Garber AJ. Long-acting glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists: a review of their efficacy and tolerability. Diabetes Care. 2011;34 (Suppl 2):S279-S284.

11. Young LA, Buse JB. GLP-1 receptor agonists and basal insulin in type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2014;384:2180-2181.

12. Pharmacist’s Letter. Comparison of GLP-1 Agonists [detail document]. December 2014. Available at: http://pharmacistsletter.therapeuticresearch.com/pl/Browse.aspx?cs=&s=PL&pt=6&fpt=31&dd=300804&pb=PL&cat=5718#dd. Accessed December 28, 2015.

› Turn first to metformin for pharmacologic treatment of type 2 diabetes. A

› Add a second oral agent (such as a sulfonylurea, thiazolidinedione, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor, or dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor), a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, or basal insulin if metformin at a maximum tolerated dose does not achieve the HbA1c target over 3 months. A

› Progress to bolus mealtime insulin or a GLP-1 agonist to cover postprandial glycemic excursions if HbA1c remains above goal despite an adequate trial of basal insulin. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

The "Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes" guidelines published in 2015 by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) state that metformin is the preferred initial pharmacotherapy for managing type 2 diabetes.1 Metformin, a biguanide, enhances insulin sensitivity in muscle and fat tissue and inhibits hepatic glucose production. Advantages of metformin include the longstanding research supporting its efficacy and safety, an expected decrease in the glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level of 1% to 1.5%, low cost, minimal hypoglycemic risk, and potential reductions in cardiovascular (CV) events due to decreased low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol.1,2

To minimize adverse gastrointestinal effects, start metformin at 500 mg once or twice a day and titrate upward every one to 2 weeks to the target dose.3 To help guide dosing decisions, use the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) instead of the serum creatinine (SCr) level, because the SCr can translate into a variable range of eGFRs (TABLE 1).4,5

What if metformin alone isn't enough?

CASE › Richard C, age 50, has type 2 diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and obesity. He takes metformin 1 g twice a day for his diabetes. After 3 months on this regimen, his HbA1c is 8.8%. How would you manage Mr. C's diabetes going forward?

If metformin at a maximum tolerated dose does not achieve the HbA1c target after 3 months, add a second oral agent (a sulfonylurea [SU], thiazolidinedione [TZD], dipeptidyl peptidase 4 [DPP-4] inhibitor, or sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 [SGLT2] inhibitor), a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, or a basal insulin (TABLE 2).1

Factors that will affect the choice of the second agent include patient preference, cost, potential adverse effects, impact on weight, efficacy, and risk of hypoglycemia.

Based on cost, familiarity, and longstanding safety data, you decide to give Mr. C an SU, while cautioning him about hypoglycemia.

CASE › Mr. C has now been taking metformin and an SU at maximum doses for 2 years and continues with lifestyle modifications. Though his HbA1c level dropped after adding the SU, over 2 years it has crept up to 8.6% and his mean blood glucose is 186 mg/dL. What are your treatment options now?

If the target HbA1c level is not achieved on dual therapy, consider triple therapy combinations (TABLE 3).1

In Mr. C's case, a third oral agent could be added, but DPP-4 and SGLT2 are unlikely to get his HbA1c below 7%. TZD may get his HbA1c into the desired range but is associated with adverse effects such as heart failure, edema, and weight gain. Mr. C agrees instead to start a basal insulin in conjunction with metformin. You could continue the SU, but you decide to stop it because the additive effect of these medications increases the risk of hypoglycemia.

CASE › Six months later Mr. C is taking metformin and insulin glargine, a basal insulin, adjusted to a fasting blood glucose of 80 to 130 mg/dL. His HbA1c is still above target at 8.4%, and the mean postprandial blood glucose is 232 mg/dL.

Mr. C is still above target for HbA1c and for postprandial blood glucose (goal: <180 mg/dL), so he needs pharmacotherapy that targets postprandial glucose elevations.1 His fasting blood glucose readings are at goal, so increasing his insulin glargine is not recommended because it could cause hypoglycemia. An oral agent other than SU could be added, but none is potent enough to lower the HbA1c to goal (TABLE 2).1 There are 3 other options:

- add a mealtime bolus of insulin

- add a GLP-1 receptor agonist

- switch to premixed (biphasic) insulin.

What to do when basal insulin isn’t enough—with or without oral medsFor type 2 diabetes poorly controlled on basal insulin with or without oral agents, the 2015 ADA treatment guidelines recommend adding a GLP-1 receptor agonist or mealtime insulin.1 A less desirable alternative is to switch from basal insulin to a twice-daily premixed (biphasic) insulin analog (70/30 aspart mix or 75/25 or 50/50 lispro mix). The human NPH-Regular premixed formulations (70/30) are less costly alternatives. The disadvantage with all premixed insulins is they only cover 2 postprandial glucose elevations a day.1,6,7

Insulin requires multiple daily injections, can lead to weight gain, and carries the risk of hypoglycemia, which causes significant morbidity.8,9 Daily or weekly administration of a GLP-1 receptor agonist combined with basal insulin can offer a more convenient alternative to mealtime boluses of insulin.

What are GLP-1 receptor agonists?

GLP-1 receptor agonists exert their maximum influence on blood glucose levels during the postprandial period by mimicking the body’s natural incretin hormonal response to oral glucose ingestion.10 They delay gastric emptying, promote satiety, decrease glucagon secretion, and increase insulin secretion.10,11 This mechanism blunts the spiking of postprandial blood glucose after a meal and improves blood glucose control and weight reduction.1,6,7

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Eng and colleagues compared the safety and efficacy of combined GLP-1 agonist and basal insulin with other treatment regimens.7 Fifteen randomized controlled trials were included involving 4348 participants with a mean trial duration of 25 weeks.

Compared with all other treatment regimens, the GLP-1 receptor agonist and basal insulin combination not only significantly reduced HbA1c by 0.44% (95% confidence interval [CI], -0.60 to -0.29) and increased the likelihood of attaining an HbA1c of <7.0% (relative risk [RR]=1.92; 95% CI, 1.43 to 2.56) but also reduced weight by 3.22 kg (-4.90 to -1.54) with no increased risk of hypoglycemia (RR=0.99; 0.76 to 1.29).7

GLP-1 agonist vs bolus insulin

Compared with basal-bolus insulin regimens, the combination of a GLP-1 receptor agonist with basal insulin has led to a significantly lowered risk of hypoglycemia (RR=0.67; 95% CI, 0.56 to 0.80), greater weight loss (-5.66 kg; 95% CI, -9.8 to -1.51) and an average reduction in HbA1c of 0.1% (95% CI, -0.17 to -0.02).7

There are 5 GLP-1 receptor agonists that have US Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: albiglutide, dulaglutide, exenatide, exenatide XR, and liraglutide (TABLE 4).3,12

All 5 agents are administered subcutaneously and packaged in pen-injector form. Adverse effects include nausea, which is transient and diminishes within the first few weeks of therapy, and less commonly, pancreatitis.3,12

All of the GLP-1 receptor agonists, except short-acting exenatide, carry a warning about the risk of worsening renal function and a possible association with medullary thyroid carcinomas, which were identified in rats, but have not been observed in humans.3,12 Medications in this drug class have a low risk for precipitating hypoglycemia.11 Cost is their chief disadvantage, although copay reduction cards are available online for most of the products. Evaluate efficacy, ease of use, tolerability, and cost when selecting a GLP-1 receptor agonist.3,12

CASE › Mr. C prefers a more convenient option than adding another daily injection. Given his obesity, a GLP-1 receptor agonist can help with weight loss and lower his risk for hypoglycemia. To further increase the convenience in dosing, you lean toward either weekly exenatide XR or dulaglutide over basal-bolus combination insulin. Weekly albiglutide is less potent than exenatide XR and dulaglutide in decreasing HbA1c.12 Mr. C’s insurance plan provides preferred coverage for exenatide XR and he is eligible for a copay savings card, meaning he will pay no more than $25 per month for this new prescription. You prescribe exenatide XR and ask him to record his postprandial blood glucose levels. You follow up in one month to assess his response.

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Mounsey, MD, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine, 590 Manning Drive, Campus Box 7595, Chapel Hill, NC 27599; [email protected].

› Turn first to metformin for pharmacologic treatment of type 2 diabetes. A

› Add a second oral agent (such as a sulfonylurea, thiazolidinedione, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor, or dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor), a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, or basal insulin if metformin at a maximum tolerated dose does not achieve the HbA1c target over 3 months. A

› Progress to bolus mealtime insulin or a GLP-1 agonist to cover postprandial glycemic excursions if HbA1c remains above goal despite an adequate trial of basal insulin. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

The "Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes" guidelines published in 2015 by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) state that metformin is the preferred initial pharmacotherapy for managing type 2 diabetes.1 Metformin, a biguanide, enhances insulin sensitivity in muscle and fat tissue and inhibits hepatic glucose production. Advantages of metformin include the longstanding research supporting its efficacy and safety, an expected decrease in the glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level of 1% to 1.5%, low cost, minimal hypoglycemic risk, and potential reductions in cardiovascular (CV) events due to decreased low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol.1,2

To minimize adverse gastrointestinal effects, start metformin at 500 mg once or twice a day and titrate upward every one to 2 weeks to the target dose.3 To help guide dosing decisions, use the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) instead of the serum creatinine (SCr) level, because the SCr can translate into a variable range of eGFRs (TABLE 1).4,5

What if metformin alone isn't enough?

CASE › Richard C, age 50, has type 2 diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and obesity. He takes metformin 1 g twice a day for his diabetes. After 3 months on this regimen, his HbA1c is 8.8%. How would you manage Mr. C's diabetes going forward?

If metformin at a maximum tolerated dose does not achieve the HbA1c target after 3 months, add a second oral agent (a sulfonylurea [SU], thiazolidinedione [TZD], dipeptidyl peptidase 4 [DPP-4] inhibitor, or sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 [SGLT2] inhibitor), a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, or a basal insulin (TABLE 2).1

Factors that will affect the choice of the second agent include patient preference, cost, potential adverse effects, impact on weight, efficacy, and risk of hypoglycemia.

Based on cost, familiarity, and longstanding safety data, you decide to give Mr. C an SU, while cautioning him about hypoglycemia.

CASE › Mr. C has now been taking metformin and an SU at maximum doses for 2 years and continues with lifestyle modifications. Though his HbA1c level dropped after adding the SU, over 2 years it has crept up to 8.6% and his mean blood glucose is 186 mg/dL. What are your treatment options now?

If the target HbA1c level is not achieved on dual therapy, consider triple therapy combinations (TABLE 3).1

In Mr. C's case, a third oral agent could be added, but DPP-4 and SGLT2 are unlikely to get his HbA1c below 7%. TZD may get his HbA1c into the desired range but is associated with adverse effects such as heart failure, edema, and weight gain. Mr. C agrees instead to start a basal insulin in conjunction with metformin. You could continue the SU, but you decide to stop it because the additive effect of these medications increases the risk of hypoglycemia.

CASE › Six months later Mr. C is taking metformin and insulin glargine, a basal insulin, adjusted to a fasting blood glucose of 80 to 130 mg/dL. His HbA1c is still above target at 8.4%, and the mean postprandial blood glucose is 232 mg/dL.

Mr. C is still above target for HbA1c and for postprandial blood glucose (goal: <180 mg/dL), so he needs pharmacotherapy that targets postprandial glucose elevations.1 His fasting blood glucose readings are at goal, so increasing his insulin glargine is not recommended because it could cause hypoglycemia. An oral agent other than SU could be added, but none is potent enough to lower the HbA1c to goal (TABLE 2).1 There are 3 other options:

- add a mealtime bolus of insulin

- add a GLP-1 receptor agonist

- switch to premixed (biphasic) insulin.

What to do when basal insulin isn’t enough—with or without oral medsFor type 2 diabetes poorly controlled on basal insulin with or without oral agents, the 2015 ADA treatment guidelines recommend adding a GLP-1 receptor agonist or mealtime insulin.1 A less desirable alternative is to switch from basal insulin to a twice-daily premixed (biphasic) insulin analog (70/30 aspart mix or 75/25 or 50/50 lispro mix). The human NPH-Regular premixed formulations (70/30) are less costly alternatives. The disadvantage with all premixed insulins is they only cover 2 postprandial glucose elevations a day.1,6,7

Insulin requires multiple daily injections, can lead to weight gain, and carries the risk of hypoglycemia, which causes significant morbidity.8,9 Daily or weekly administration of a GLP-1 receptor agonist combined with basal insulin can offer a more convenient alternative to mealtime boluses of insulin.

What are GLP-1 receptor agonists?

GLP-1 receptor agonists exert their maximum influence on blood glucose levels during the postprandial period by mimicking the body’s natural incretin hormonal response to oral glucose ingestion.10 They delay gastric emptying, promote satiety, decrease glucagon secretion, and increase insulin secretion.10,11 This mechanism blunts the spiking of postprandial blood glucose after a meal and improves blood glucose control and weight reduction.1,6,7

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Eng and colleagues compared the safety and efficacy of combined GLP-1 agonist and basal insulin with other treatment regimens.7 Fifteen randomized controlled trials were included involving 4348 participants with a mean trial duration of 25 weeks.

Compared with all other treatment regimens, the GLP-1 receptor agonist and basal insulin combination not only significantly reduced HbA1c by 0.44% (95% confidence interval [CI], -0.60 to -0.29) and increased the likelihood of attaining an HbA1c of <7.0% (relative risk [RR]=1.92; 95% CI, 1.43 to 2.56) but also reduced weight by 3.22 kg (-4.90 to -1.54) with no increased risk of hypoglycemia (RR=0.99; 0.76 to 1.29).7

GLP-1 agonist vs bolus insulin

Compared with basal-bolus insulin regimens, the combination of a GLP-1 receptor agonist with basal insulin has led to a significantly lowered risk of hypoglycemia (RR=0.67; 95% CI, 0.56 to 0.80), greater weight loss (-5.66 kg; 95% CI, -9.8 to -1.51) and an average reduction in HbA1c of 0.1% (95% CI, -0.17 to -0.02).7

There are 5 GLP-1 receptor agonists that have US Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: albiglutide, dulaglutide, exenatide, exenatide XR, and liraglutide (TABLE 4).3,12

All 5 agents are administered subcutaneously and packaged in pen-injector form. Adverse effects include nausea, which is transient and diminishes within the first few weeks of therapy, and less commonly, pancreatitis.3,12

All of the GLP-1 receptor agonists, except short-acting exenatide, carry a warning about the risk of worsening renal function and a possible association with medullary thyroid carcinomas, which were identified in rats, but have not been observed in humans.3,12 Medications in this drug class have a low risk for precipitating hypoglycemia.11 Cost is their chief disadvantage, although copay reduction cards are available online for most of the products. Evaluate efficacy, ease of use, tolerability, and cost when selecting a GLP-1 receptor agonist.3,12

CASE › Mr. C prefers a more convenient option than adding another daily injection. Given his obesity, a GLP-1 receptor agonist can help with weight loss and lower his risk for hypoglycemia. To further increase the convenience in dosing, you lean toward either weekly exenatide XR or dulaglutide over basal-bolus combination insulin. Weekly albiglutide is less potent than exenatide XR and dulaglutide in decreasing HbA1c.12 Mr. C’s insurance plan provides preferred coverage for exenatide XR and he is eligible for a copay savings card, meaning he will pay no more than $25 per month for this new prescription. You prescribe exenatide XR and ask him to record his postprandial blood glucose levels. You follow up in one month to assess his response.

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Mounsey, MD, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine, 590 Manning Drive, Campus Box 7595, Chapel Hill, NC 27599; [email protected].

1. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes - 2015. Diabetes Care. 2015;38 (Suppl):S1-S94.

2. Bennett WL, Maruthur NM, Singh S, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of medications for type 2 diabetes: an update including new drugs and 2-drug combinations. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:602-613.

3. Merck Manual. Metformin. Available at: http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/appendixes/brand-names-of-some-commonly-used-drugs. Accessed April 18, 2015.

4. Lipska KJ, Bailey CJ, Inzucchi SE. Use of metformin in the setting of mild-to-moderate renal insufficiency. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1431-1437.

5. Philbrick AM, Ernst ME, McDanel DL, et al. Metformin use in renal dysfunction: is a serum creatinine threshold appropriate? Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009;66:2017-2023.

6. Pharmacist’s Letter. Drugs for Type 2 Diabetes [detail document]. September 2015. Available at: http://pharmacistsletter.therapeuticresearch.com/pl/ArticleDD.aspx?nidchk=1&cs=&s=PL&pt=2&segment=4407&dd=280601. Accessed December 28, 2015.

7. Eng C, Kramer CK, Zinman B, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist and basal insulin combination treatment for the management of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2014;384:2228-2234.

8. Inzucchi SE, Burgenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1364-1379.

9. Bonds DE, Miller ME, Bergenstal RM, et al. The association between symptomatic, severe hypoglycaemia and mortality in type 2 diabetes: retrospective epidemiological analysis of the ACCORD study. BMJ. 2010:340:b4909.

10. Garber AJ. Long-acting glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists: a review of their efficacy and tolerability. Diabetes Care. 2011;34 (Suppl 2):S279-S284.

11. Young LA, Buse JB. GLP-1 receptor agonists and basal insulin in type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2014;384:2180-2181.

12. Pharmacist’s Letter. Comparison of GLP-1 Agonists [detail document]. December 2014. Available at: http://pharmacistsletter.therapeuticresearch.com/pl/Browse.aspx?cs=&s=PL&pt=6&fpt=31&dd=300804&pb=PL&cat=5718#dd. Accessed December 28, 2015.

1. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes - 2015. Diabetes Care. 2015;38 (Suppl):S1-S94.

2. Bennett WL, Maruthur NM, Singh S, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of medications for type 2 diabetes: an update including new drugs and 2-drug combinations. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:602-613.

3. Merck Manual. Metformin. Available at: http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/appendixes/brand-names-of-some-commonly-used-drugs. Accessed April 18, 2015.

4. Lipska KJ, Bailey CJ, Inzucchi SE. Use of metformin in the setting of mild-to-moderate renal insufficiency. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1431-1437.

5. Philbrick AM, Ernst ME, McDanel DL, et al. Metformin use in renal dysfunction: is a serum creatinine threshold appropriate? Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009;66:2017-2023.

6. Pharmacist’s Letter. Drugs for Type 2 Diabetes [detail document]. September 2015. Available at: http://pharmacistsletter.therapeuticresearch.com/pl/ArticleDD.aspx?nidchk=1&cs=&s=PL&pt=2&segment=4407&dd=280601. Accessed December 28, 2015.

7. Eng C, Kramer CK, Zinman B, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist and basal insulin combination treatment for the management of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2014;384:2228-2234.

8. Inzucchi SE, Burgenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1364-1379.

9. Bonds DE, Miller ME, Bergenstal RM, et al. The association between symptomatic, severe hypoglycaemia and mortality in type 2 diabetes: retrospective epidemiological analysis of the ACCORD study. BMJ. 2010:340:b4909.

10. Garber AJ. Long-acting glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists: a review of their efficacy and tolerability. Diabetes Care. 2011;34 (Suppl 2):S279-S284.

11. Young LA, Buse JB. GLP-1 receptor agonists and basal insulin in type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2014;384:2180-2181.

12. Pharmacist’s Letter. Comparison of GLP-1 Agonists [detail document]. December 2014. Available at: http://pharmacistsletter.therapeuticresearch.com/pl/Browse.aspx?cs=&s=PL&pt=6&fpt=31&dd=300804&pb=PL&cat=5718#dd. Accessed December 28, 2015.