User login

Case

A 65-year-old male with a history of a motor vehicle accident that required emergency surgery in 1982 is hospitalized for acute renal failure. He reports a distant history of IV heroin use and a brief incarceration. He does not currently use illicit drugs. He has no signs or symptoms of liver disease. Should this patient be screened for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection?

Brief Overview

HCV is a major public health concern in the United States and worldwide. It is estimated that more than 4.1 million people in the U.S. (1.6% prevalence) and more than 180 million worldwide (2.8% prevalence) are HCV antibody-positive.1,2 The acute infection is most often asymptomatic, and 80% to 100% of patients will remain HCV RNA-positive, 60% to 80% will have persistently elevated liver enzymes, and 16% will develop evidence of cirrhosis at 20 years after initial infection.3

A number of organizations in the United States have released HCV screening guidelines, including the CDC, the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD), and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF); however, despite these established recommendations, an estimated 50% of individuals with chronic HCV infection are unscreened and unaware of their infection status.4 Furthermore, in a recent study of one managed care network, even when one or more risk factors were present, only 29% of individuals underwent screening for HCV antibodies detection.5 The importance of detecting chronic HCV infection will have greater significance as newer and better-tolerated treatment options become available.6

Multiple organizations recommend screening for chronic HCV infection. This screening is recommended for patients with known risk factors and those in populations with a high prevalence of HCV infection.

Risk Factors and High-Prevalence Populations

IV or intranasal drug use. IV drug use is the main identifiable source of HCV infection in the U.S. It is estimated that 60% of new HCV infections occur in people who have injected drugs in the past six months.7 The prevalence of HCV antibodies in current IV drug users is between 72% and 96%.8 Intranasal cocaine use is also associated with a higher prevalence of HCV antibodies than the general population.8

Blood transfusion prior to July 1992. Testing of donor blood was not routinely done until 1990, and more sensitive testing was not implemented until July 1992.8 The prevalence of HCV antibodies in people who received blood transfusions prior to 1990 is 6%.8 Prior to 1990, the risk for transfusion-associated HCV infection was one in 526 units transfused.9 Since implementation of highly sensitive screening techniques, the risk of infection has dropped to less than one in 1.9 million units transfused.10

Clotting factors prior to 1987 or transplanted tissue prior to 1992. Individuals who have received clotting factors, other blood product transfusions, or transplanted tissue prior to 1987 are at an increased risk for developing HCV infection. For instance, individuals with hemophilia treated with clotting factors prior to 1987 had chronic HCV infection rates of up to 90%.8 In 1987, widespread use of protocols to inactivate HCV in clotting factors and other blood products was adopted.8 In addition, widespread screening of potential tissue donors and the use of HCV antibody-negative donors became routine.8

Alanine aminotransferase elevation. This can be considered screening or part of the diagnostic work-up of transaminitis. Regardless of the classification, this is a cohort of people with a high prevalence of HCV antibody. For individuals with one isolated alanine aminotransferase elevation, the prevalence is 3.2%.4 With two or more elevated aminotransferase results, the prevalence rises to 8.2%.4

Hemodialysis. Two major studies have estimated the prevalence of HCV antibody-positive in end-stage renal disease individuals on hemodialysis to be 7.8% and 10.4%.11,12 This prevalence can reach 64% at some dialysis centers.11 The risk of HCV infection has been associated with blood transfusions, longer duration of hemodialysis, and higher rates of HCV infection in the dialysis unit.13 With implementation of infection control practices in dialysis units, the incidence and prevalence of HCV infection are declining.13

Born in the U.S. between 1945 and 1965. The CDC and USPSTF recommend a one-time screening for HCV infection for people born in the U.S. between 1945 and 1965, regardless of the presence or absence of risk factors.6,14 This age group has an increased prevalence of HCV antibodies, at 3.25%.6

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). HCV has a prevalence of 30% in people infected with HIV.15 The rate of co-infection is likely secondary to shared routes of transmission. For example, 72.7% of HIV-infected individuals who used IV drugs had HCV antibodies, but only 3.5% of “low-risk” HIV-infected individuals had HCV antibodies.16

Born in a high prevalence country. In the U.S., a significant number of immigrants are from areas with a high endemic rate of HCV infection. High prevalence areas (greater than 3.5%) include Central Asia and East Asia, North Africa, and the Middle East.7 Of note, Egypt is thought to have the highest prevalence of chronic HCV infection in the world, with well over 10% of the population being antibody-positive.17 Although major guidelines do not currently recommend it, the high prevalence of chronic HCV infection in this population may warrant screening.

Other high-risk or high-prevalence populations. The prevalence of HCV infection in people who have had over 10 lifetime sexual partners (3% to 9%), those with a history of sexually transmitted disease (6%), men who have had sex with men (5%), and children born to HCV-infected mothers (5%) is increased compared with the general population.8 Incarcerated people in the U.S. have an HCV antibody prevalence of 16% to 41%.18 In addition, people who have sustained needle-stick injury or mucosal exposure, or those with potential exposures in unregulated tattoo or piercing salons, may also benefit from HCV antibody screening.14

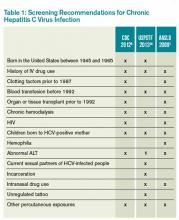

Table 1 reviews HCV screening recommendations for the CDC, AASLD, and USPSTF.1,6,8,14

CDC=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; USPSTF=U.S. Preventive Services Task Force; AASLD=American Association for the Study of Liver Disease; ALT=alanine aminotransferase; 1=considered diagnostic and not screening test

Screening Method

The most common initial screening test for the diagnosis of chronic HCV infection is the HCV antibody test. A positive antibody test should be followed by an HCV RNA test. In an individual with recent exposure, it takes between four and 10 weeks for the antibody to be detectable. HCV RNA testing can be positive as soon as two to three weeks after infection.8

Hospitalist Role in HCV Screening

None of the U.S.-based guidelines make recommendations on the preferred setting for HCV screening. According to the CDC, 60.4% of HCV screening was done in a physician office and 5.9% was done as a hospital inpatient.19 Traditionally, the PCP is responsible for screening for chronic diseases, including HCV infection; however, the current screening rate is insufficient, as 50% of people with chronic HCV infection remain unscreened.4

Given the insufficient rate of HCV screening at present, hospital medicine (HM) physicians have an opportunity to help improve this rate. Currently, there is no established standard of care for HCV screening in hospitalized patients. HM physicians could use the following strategies:

- Continue the current system and defer screening to outpatient providers;

- Offer screening to selected inpatients at high risk for chronic HCV infection; or

- Offer screening to all inpatients who meet screening criteria based on current guidelines.

Given the shortcomings of the current screening strategies, these authors would recommend widespread screening for chronic HCV infection in hospitalized people who meet screening criteria per current guidelines.

If HM physicians are to take an increased role in HCV screening, there are a number of important considerations. Because hospitalized patients have a limited length of stay, it would be unreasonable to expect HM physicians to test for HCV RNA viral load or genotype for all patients with a positive antibody test, because the duration of the inpatient stay may be shorter than the time it takes for these test results to return. These tests are often indicated after a positive HCV antibody test, however. Thus, communication of HCV antibody results to PCPs or other responsible providers is essential. If no follow-up is available or there are no responsible outpatient providers, HM physicians should continue with a limited screening strategy.

Back to the Case

This individual has multiple indications for chronic HCV infection screening. His risk factors include date of birth between 1945 and 1965, a history of IV drug use, and a history of incarceration. He also notes a history of emergency surgery, for which he may have received blood products prior to 1987. These factors significantly raise the likelihood of chronic HCV infection when compared with the general population. He was screened and found to be HCV antibody-positive. A follow-up HCV RNA viral load was also positive. He did not have any evidence of liver disease but did have a mild transaminitis. He has followed up as an outpatient with plans to start therapy.

Bottom Line

The current screening strategies for individuals with high prevalence of chronic HCV infection are insufficient. HM physicians have an opportunity to improve the rates of screening in this population.

Dr. Theisen-Toupal is an internist, Dr. Rosenthal is a clinical fellow in medicine, and Dr. Carbo is an assistant professor of medicine, all at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. Dr. Li is an internist and associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the hospital medicine division at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

References

- Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49(4):1335-1374.

- Mohd Hanafiah K, Groeger J, Flaxman AD, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: new estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology. 2013;57(4):1333-1342.

- Chopra S. Clinical manifestations and natural history of chronic hepatitis C virus infection. UpToDate. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-natural-history-of-chronic-hepatitis-c-virus-infection. Accessed March 5, 2014.

- Spradling PR, Rupp L, Moorman AC, et al. Hepatitis B and C virus infection among 1.2 million people with access to care: factors associated with testing and infection prevalence. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(8):1047-1055.

- Roblin DW, Smith BD, Weinbaum CM, Sabin ME. HCV screening practices and prevalence in an MCO, 2000-2007. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(8):548-555.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among people born during 1945-1965. MMWR. August 17, 2012. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6104a1.htm. Accessed March 5, 2014.

- Chopra S. Epidemiology and transmission of hepatitis C virus infection. UpToDate. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-and-transmission-of-hepatitis-c-virus-infection?source=search_result&search=%22Epidemiology+and+transmission+of+hepatitis+C+virus+infection%22&selectedTitle=1~150. Accessed March 5, 2014.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV-related chronic disease. MMWR. October 16, 1998. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00055154.htm. Accessed March 5, 2014.

- Donahue JG, Muñoz A, Ness PM, et al. The declining risk of post-transfusion hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(6):369-373.

- Pomper GJ, Wu Y, Snyder EL. Risks of transfusion-transmitted infections: 2003. Curr Opin Hematol. 2003;10(6):412-418.

- Tokars JI, Miller ER, Alter MJ, Arduino MJ. National surveillance of dialysis associated diseases in the United States, 1995. ASAIO J. 1998;44(1):98-107.

- Finelli L, Miller JT, Tokars JI, Alter MJ, Arduino MJ. National surveillance of dialysis-associated diseases in the United States, 2002. Semin Dial. 2005;18(1):52-61.

- Natov S, Pereira BJG. Hepatitis C virus infection in patients on maintenance dialysis. UpToDate. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/hepatitis-c-virus-infection-in-patients-on-maintenance-dialysis?source=search_result&search=Hepatitis+C+virus+infection+in+patients+on+maintenance+dialysis.&selectedTitle=1~150. Accessed March 5, 2014.

- Moyer VA, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(5):349-357.

- Staples CT II, Rimland D, Dudas D. Hepatitis C in the HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) Atlanta V.A. (Veterans Affairs Medical Center) Cohort Study (HAVACS): the effect of coinfection on survival. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29(1):150-154.

- Sherman KE, Rouster SD, Chung RT, Rajicic N. Hepatitis C virus prevalence among patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus: a cross-sectional analysis of the U.S. adult AIDS clinical trials group. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(6):831-837.

- Averhoff FM, Glass N, Holtzman D. Global burden of hepatitis C: considerations for healthcare providers in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55 Suppl 1:S10-15.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and control of infections with hepatitis viruses in correctional settings. MMWR. January 24, 2003. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5201a1.htm. Accessed March 5, 2014.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Locations and reasons for initial testing for hepatitis C infection—chronic hepatitis cohort study, United States, 2006-2010. MMWR. August 16, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6232a3.htm?s_cid=mm6232a3_w. Accessed March 5, 2014.

Case

A 65-year-old male with a history of a motor vehicle accident that required emergency surgery in 1982 is hospitalized for acute renal failure. He reports a distant history of IV heroin use and a brief incarceration. He does not currently use illicit drugs. He has no signs or symptoms of liver disease. Should this patient be screened for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection?

Brief Overview

HCV is a major public health concern in the United States and worldwide. It is estimated that more than 4.1 million people in the U.S. (1.6% prevalence) and more than 180 million worldwide (2.8% prevalence) are HCV antibody-positive.1,2 The acute infection is most often asymptomatic, and 80% to 100% of patients will remain HCV RNA-positive, 60% to 80% will have persistently elevated liver enzymes, and 16% will develop evidence of cirrhosis at 20 years after initial infection.3

A number of organizations in the United States have released HCV screening guidelines, including the CDC, the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD), and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF); however, despite these established recommendations, an estimated 50% of individuals with chronic HCV infection are unscreened and unaware of their infection status.4 Furthermore, in a recent study of one managed care network, even when one or more risk factors were present, only 29% of individuals underwent screening for HCV antibodies detection.5 The importance of detecting chronic HCV infection will have greater significance as newer and better-tolerated treatment options become available.6

Multiple organizations recommend screening for chronic HCV infection. This screening is recommended for patients with known risk factors and those in populations with a high prevalence of HCV infection.

Risk Factors and High-Prevalence Populations

IV or intranasal drug use. IV drug use is the main identifiable source of HCV infection in the U.S. It is estimated that 60% of new HCV infections occur in people who have injected drugs in the past six months.7 The prevalence of HCV antibodies in current IV drug users is between 72% and 96%.8 Intranasal cocaine use is also associated with a higher prevalence of HCV antibodies than the general population.8

Blood transfusion prior to July 1992. Testing of donor blood was not routinely done until 1990, and more sensitive testing was not implemented until July 1992.8 The prevalence of HCV antibodies in people who received blood transfusions prior to 1990 is 6%.8 Prior to 1990, the risk for transfusion-associated HCV infection was one in 526 units transfused.9 Since implementation of highly sensitive screening techniques, the risk of infection has dropped to less than one in 1.9 million units transfused.10

Clotting factors prior to 1987 or transplanted tissue prior to 1992. Individuals who have received clotting factors, other blood product transfusions, or transplanted tissue prior to 1987 are at an increased risk for developing HCV infection. For instance, individuals with hemophilia treated with clotting factors prior to 1987 had chronic HCV infection rates of up to 90%.8 In 1987, widespread use of protocols to inactivate HCV in clotting factors and other blood products was adopted.8 In addition, widespread screening of potential tissue donors and the use of HCV antibody-negative donors became routine.8

Alanine aminotransferase elevation. This can be considered screening or part of the diagnostic work-up of transaminitis. Regardless of the classification, this is a cohort of people with a high prevalence of HCV antibody. For individuals with one isolated alanine aminotransferase elevation, the prevalence is 3.2%.4 With two or more elevated aminotransferase results, the prevalence rises to 8.2%.4

Hemodialysis. Two major studies have estimated the prevalence of HCV antibody-positive in end-stage renal disease individuals on hemodialysis to be 7.8% and 10.4%.11,12 This prevalence can reach 64% at some dialysis centers.11 The risk of HCV infection has been associated with blood transfusions, longer duration of hemodialysis, and higher rates of HCV infection in the dialysis unit.13 With implementation of infection control practices in dialysis units, the incidence and prevalence of HCV infection are declining.13

Born in the U.S. between 1945 and 1965. The CDC and USPSTF recommend a one-time screening for HCV infection for people born in the U.S. between 1945 and 1965, regardless of the presence or absence of risk factors.6,14 This age group has an increased prevalence of HCV antibodies, at 3.25%.6

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). HCV has a prevalence of 30% in people infected with HIV.15 The rate of co-infection is likely secondary to shared routes of transmission. For example, 72.7% of HIV-infected individuals who used IV drugs had HCV antibodies, but only 3.5% of “low-risk” HIV-infected individuals had HCV antibodies.16

Born in a high prevalence country. In the U.S., a significant number of immigrants are from areas with a high endemic rate of HCV infection. High prevalence areas (greater than 3.5%) include Central Asia and East Asia, North Africa, and the Middle East.7 Of note, Egypt is thought to have the highest prevalence of chronic HCV infection in the world, with well over 10% of the population being antibody-positive.17 Although major guidelines do not currently recommend it, the high prevalence of chronic HCV infection in this population may warrant screening.

Other high-risk or high-prevalence populations. The prevalence of HCV infection in people who have had over 10 lifetime sexual partners (3% to 9%), those with a history of sexually transmitted disease (6%), men who have had sex with men (5%), and children born to HCV-infected mothers (5%) is increased compared with the general population.8 Incarcerated people in the U.S. have an HCV antibody prevalence of 16% to 41%.18 In addition, people who have sustained needle-stick injury or mucosal exposure, or those with potential exposures in unregulated tattoo or piercing salons, may also benefit from HCV antibody screening.14

Table 1 reviews HCV screening recommendations for the CDC, AASLD, and USPSTF.1,6,8,14

CDC=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; USPSTF=U.S. Preventive Services Task Force; AASLD=American Association for the Study of Liver Disease; ALT=alanine aminotransferase; 1=considered diagnostic and not screening test

Screening Method

The most common initial screening test for the diagnosis of chronic HCV infection is the HCV antibody test. A positive antibody test should be followed by an HCV RNA test. In an individual with recent exposure, it takes between four and 10 weeks for the antibody to be detectable. HCV RNA testing can be positive as soon as two to three weeks after infection.8

Hospitalist Role in HCV Screening

None of the U.S.-based guidelines make recommendations on the preferred setting for HCV screening. According to the CDC, 60.4% of HCV screening was done in a physician office and 5.9% was done as a hospital inpatient.19 Traditionally, the PCP is responsible for screening for chronic diseases, including HCV infection; however, the current screening rate is insufficient, as 50% of people with chronic HCV infection remain unscreened.4

Given the insufficient rate of HCV screening at present, hospital medicine (HM) physicians have an opportunity to help improve this rate. Currently, there is no established standard of care for HCV screening in hospitalized patients. HM physicians could use the following strategies:

- Continue the current system and defer screening to outpatient providers;

- Offer screening to selected inpatients at high risk for chronic HCV infection; or

- Offer screening to all inpatients who meet screening criteria based on current guidelines.

Given the shortcomings of the current screening strategies, these authors would recommend widespread screening for chronic HCV infection in hospitalized people who meet screening criteria per current guidelines.

If HM physicians are to take an increased role in HCV screening, there are a number of important considerations. Because hospitalized patients have a limited length of stay, it would be unreasonable to expect HM physicians to test for HCV RNA viral load or genotype for all patients with a positive antibody test, because the duration of the inpatient stay may be shorter than the time it takes for these test results to return. These tests are often indicated after a positive HCV antibody test, however. Thus, communication of HCV antibody results to PCPs or other responsible providers is essential. If no follow-up is available or there are no responsible outpatient providers, HM physicians should continue with a limited screening strategy.

Back to the Case

This individual has multiple indications for chronic HCV infection screening. His risk factors include date of birth between 1945 and 1965, a history of IV drug use, and a history of incarceration. He also notes a history of emergency surgery, for which he may have received blood products prior to 1987. These factors significantly raise the likelihood of chronic HCV infection when compared with the general population. He was screened and found to be HCV antibody-positive. A follow-up HCV RNA viral load was also positive. He did not have any evidence of liver disease but did have a mild transaminitis. He has followed up as an outpatient with plans to start therapy.

Bottom Line

The current screening strategies for individuals with high prevalence of chronic HCV infection are insufficient. HM physicians have an opportunity to improve the rates of screening in this population.

Dr. Theisen-Toupal is an internist, Dr. Rosenthal is a clinical fellow in medicine, and Dr. Carbo is an assistant professor of medicine, all at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. Dr. Li is an internist and associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the hospital medicine division at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

References

- Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49(4):1335-1374.

- Mohd Hanafiah K, Groeger J, Flaxman AD, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: new estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology. 2013;57(4):1333-1342.

- Chopra S. Clinical manifestations and natural history of chronic hepatitis C virus infection. UpToDate. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-natural-history-of-chronic-hepatitis-c-virus-infection. Accessed March 5, 2014.

- Spradling PR, Rupp L, Moorman AC, et al. Hepatitis B and C virus infection among 1.2 million people with access to care: factors associated with testing and infection prevalence. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(8):1047-1055.

- Roblin DW, Smith BD, Weinbaum CM, Sabin ME. HCV screening practices and prevalence in an MCO, 2000-2007. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(8):548-555.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among people born during 1945-1965. MMWR. August 17, 2012. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6104a1.htm. Accessed March 5, 2014.

- Chopra S. Epidemiology and transmission of hepatitis C virus infection. UpToDate. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-and-transmission-of-hepatitis-c-virus-infection?source=search_result&search=%22Epidemiology+and+transmission+of+hepatitis+C+virus+infection%22&selectedTitle=1~150. Accessed March 5, 2014.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV-related chronic disease. MMWR. October 16, 1998. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00055154.htm. Accessed March 5, 2014.

- Donahue JG, Muñoz A, Ness PM, et al. The declining risk of post-transfusion hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(6):369-373.

- Pomper GJ, Wu Y, Snyder EL. Risks of transfusion-transmitted infections: 2003. Curr Opin Hematol. 2003;10(6):412-418.

- Tokars JI, Miller ER, Alter MJ, Arduino MJ. National surveillance of dialysis associated diseases in the United States, 1995. ASAIO J. 1998;44(1):98-107.

- Finelli L, Miller JT, Tokars JI, Alter MJ, Arduino MJ. National surveillance of dialysis-associated diseases in the United States, 2002. Semin Dial. 2005;18(1):52-61.

- Natov S, Pereira BJG. Hepatitis C virus infection in patients on maintenance dialysis. UpToDate. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/hepatitis-c-virus-infection-in-patients-on-maintenance-dialysis?source=search_result&search=Hepatitis+C+virus+infection+in+patients+on+maintenance+dialysis.&selectedTitle=1~150. Accessed March 5, 2014.

- Moyer VA, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(5):349-357.

- Staples CT II, Rimland D, Dudas D. Hepatitis C in the HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) Atlanta V.A. (Veterans Affairs Medical Center) Cohort Study (HAVACS): the effect of coinfection on survival. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29(1):150-154.

- Sherman KE, Rouster SD, Chung RT, Rajicic N. Hepatitis C virus prevalence among patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus: a cross-sectional analysis of the U.S. adult AIDS clinical trials group. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(6):831-837.

- Averhoff FM, Glass N, Holtzman D. Global burden of hepatitis C: considerations for healthcare providers in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55 Suppl 1:S10-15.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and control of infections with hepatitis viruses in correctional settings. MMWR. January 24, 2003. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5201a1.htm. Accessed March 5, 2014.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Locations and reasons for initial testing for hepatitis C infection—chronic hepatitis cohort study, United States, 2006-2010. MMWR. August 16, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6232a3.htm?s_cid=mm6232a3_w. Accessed March 5, 2014.

Case

A 65-year-old male with a history of a motor vehicle accident that required emergency surgery in 1982 is hospitalized for acute renal failure. He reports a distant history of IV heroin use and a brief incarceration. He does not currently use illicit drugs. He has no signs or symptoms of liver disease. Should this patient be screened for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection?

Brief Overview

HCV is a major public health concern in the United States and worldwide. It is estimated that more than 4.1 million people in the U.S. (1.6% prevalence) and more than 180 million worldwide (2.8% prevalence) are HCV antibody-positive.1,2 The acute infection is most often asymptomatic, and 80% to 100% of patients will remain HCV RNA-positive, 60% to 80% will have persistently elevated liver enzymes, and 16% will develop evidence of cirrhosis at 20 years after initial infection.3

A number of organizations in the United States have released HCV screening guidelines, including the CDC, the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD), and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF); however, despite these established recommendations, an estimated 50% of individuals with chronic HCV infection are unscreened and unaware of their infection status.4 Furthermore, in a recent study of one managed care network, even when one or more risk factors were present, only 29% of individuals underwent screening for HCV antibodies detection.5 The importance of detecting chronic HCV infection will have greater significance as newer and better-tolerated treatment options become available.6

Multiple organizations recommend screening for chronic HCV infection. This screening is recommended for patients with known risk factors and those in populations with a high prevalence of HCV infection.

Risk Factors and High-Prevalence Populations

IV or intranasal drug use. IV drug use is the main identifiable source of HCV infection in the U.S. It is estimated that 60% of new HCV infections occur in people who have injected drugs in the past six months.7 The prevalence of HCV antibodies in current IV drug users is between 72% and 96%.8 Intranasal cocaine use is also associated with a higher prevalence of HCV antibodies than the general population.8

Blood transfusion prior to July 1992. Testing of donor blood was not routinely done until 1990, and more sensitive testing was not implemented until July 1992.8 The prevalence of HCV antibodies in people who received blood transfusions prior to 1990 is 6%.8 Prior to 1990, the risk for transfusion-associated HCV infection was one in 526 units transfused.9 Since implementation of highly sensitive screening techniques, the risk of infection has dropped to less than one in 1.9 million units transfused.10

Clotting factors prior to 1987 or transplanted tissue prior to 1992. Individuals who have received clotting factors, other blood product transfusions, or transplanted tissue prior to 1987 are at an increased risk for developing HCV infection. For instance, individuals with hemophilia treated with clotting factors prior to 1987 had chronic HCV infection rates of up to 90%.8 In 1987, widespread use of protocols to inactivate HCV in clotting factors and other blood products was adopted.8 In addition, widespread screening of potential tissue donors and the use of HCV antibody-negative donors became routine.8

Alanine aminotransferase elevation. This can be considered screening or part of the diagnostic work-up of transaminitis. Regardless of the classification, this is a cohort of people with a high prevalence of HCV antibody. For individuals with one isolated alanine aminotransferase elevation, the prevalence is 3.2%.4 With two or more elevated aminotransferase results, the prevalence rises to 8.2%.4

Hemodialysis. Two major studies have estimated the prevalence of HCV antibody-positive in end-stage renal disease individuals on hemodialysis to be 7.8% and 10.4%.11,12 This prevalence can reach 64% at some dialysis centers.11 The risk of HCV infection has been associated with blood transfusions, longer duration of hemodialysis, and higher rates of HCV infection in the dialysis unit.13 With implementation of infection control practices in dialysis units, the incidence and prevalence of HCV infection are declining.13

Born in the U.S. between 1945 and 1965. The CDC and USPSTF recommend a one-time screening for HCV infection for people born in the U.S. between 1945 and 1965, regardless of the presence or absence of risk factors.6,14 This age group has an increased prevalence of HCV antibodies, at 3.25%.6

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). HCV has a prevalence of 30% in people infected with HIV.15 The rate of co-infection is likely secondary to shared routes of transmission. For example, 72.7% of HIV-infected individuals who used IV drugs had HCV antibodies, but only 3.5% of “low-risk” HIV-infected individuals had HCV antibodies.16

Born in a high prevalence country. In the U.S., a significant number of immigrants are from areas with a high endemic rate of HCV infection. High prevalence areas (greater than 3.5%) include Central Asia and East Asia, North Africa, and the Middle East.7 Of note, Egypt is thought to have the highest prevalence of chronic HCV infection in the world, with well over 10% of the population being antibody-positive.17 Although major guidelines do not currently recommend it, the high prevalence of chronic HCV infection in this population may warrant screening.

Other high-risk or high-prevalence populations. The prevalence of HCV infection in people who have had over 10 lifetime sexual partners (3% to 9%), those with a history of sexually transmitted disease (6%), men who have had sex with men (5%), and children born to HCV-infected mothers (5%) is increased compared with the general population.8 Incarcerated people in the U.S. have an HCV antibody prevalence of 16% to 41%.18 In addition, people who have sustained needle-stick injury or mucosal exposure, or those with potential exposures in unregulated tattoo or piercing salons, may also benefit from HCV antibody screening.14

Table 1 reviews HCV screening recommendations for the CDC, AASLD, and USPSTF.1,6,8,14

CDC=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; USPSTF=U.S. Preventive Services Task Force; AASLD=American Association for the Study of Liver Disease; ALT=alanine aminotransferase; 1=considered diagnostic and not screening test

Screening Method

The most common initial screening test for the diagnosis of chronic HCV infection is the HCV antibody test. A positive antibody test should be followed by an HCV RNA test. In an individual with recent exposure, it takes between four and 10 weeks for the antibody to be detectable. HCV RNA testing can be positive as soon as two to three weeks after infection.8

Hospitalist Role in HCV Screening

None of the U.S.-based guidelines make recommendations on the preferred setting for HCV screening. According to the CDC, 60.4% of HCV screening was done in a physician office and 5.9% was done as a hospital inpatient.19 Traditionally, the PCP is responsible for screening for chronic diseases, including HCV infection; however, the current screening rate is insufficient, as 50% of people with chronic HCV infection remain unscreened.4

Given the insufficient rate of HCV screening at present, hospital medicine (HM) physicians have an opportunity to help improve this rate. Currently, there is no established standard of care for HCV screening in hospitalized patients. HM physicians could use the following strategies:

- Continue the current system and defer screening to outpatient providers;

- Offer screening to selected inpatients at high risk for chronic HCV infection; or

- Offer screening to all inpatients who meet screening criteria based on current guidelines.

Given the shortcomings of the current screening strategies, these authors would recommend widespread screening for chronic HCV infection in hospitalized people who meet screening criteria per current guidelines.

If HM physicians are to take an increased role in HCV screening, there are a number of important considerations. Because hospitalized patients have a limited length of stay, it would be unreasonable to expect HM physicians to test for HCV RNA viral load or genotype for all patients with a positive antibody test, because the duration of the inpatient stay may be shorter than the time it takes for these test results to return. These tests are often indicated after a positive HCV antibody test, however. Thus, communication of HCV antibody results to PCPs or other responsible providers is essential. If no follow-up is available or there are no responsible outpatient providers, HM physicians should continue with a limited screening strategy.

Back to the Case

This individual has multiple indications for chronic HCV infection screening. His risk factors include date of birth between 1945 and 1965, a history of IV drug use, and a history of incarceration. He also notes a history of emergency surgery, for which he may have received blood products prior to 1987. These factors significantly raise the likelihood of chronic HCV infection when compared with the general population. He was screened and found to be HCV antibody-positive. A follow-up HCV RNA viral load was also positive. He did not have any evidence of liver disease but did have a mild transaminitis. He has followed up as an outpatient with plans to start therapy.

Bottom Line

The current screening strategies for individuals with high prevalence of chronic HCV infection are insufficient. HM physicians have an opportunity to improve the rates of screening in this population.

Dr. Theisen-Toupal is an internist, Dr. Rosenthal is a clinical fellow in medicine, and Dr. Carbo is an assistant professor of medicine, all at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. Dr. Li is an internist and associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the hospital medicine division at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

References

- Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49(4):1335-1374.

- Mohd Hanafiah K, Groeger J, Flaxman AD, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: new estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology. 2013;57(4):1333-1342.

- Chopra S. Clinical manifestations and natural history of chronic hepatitis C virus infection. UpToDate. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-natural-history-of-chronic-hepatitis-c-virus-infection. Accessed March 5, 2014.

- Spradling PR, Rupp L, Moorman AC, et al. Hepatitis B and C virus infection among 1.2 million people with access to care: factors associated with testing and infection prevalence. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(8):1047-1055.

- Roblin DW, Smith BD, Weinbaum CM, Sabin ME. HCV screening practices and prevalence in an MCO, 2000-2007. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(8):548-555.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among people born during 1945-1965. MMWR. August 17, 2012. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6104a1.htm. Accessed March 5, 2014.

- Chopra S. Epidemiology and transmission of hepatitis C virus infection. UpToDate. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-and-transmission-of-hepatitis-c-virus-infection?source=search_result&search=%22Epidemiology+and+transmission+of+hepatitis+C+virus+infection%22&selectedTitle=1~150. Accessed March 5, 2014.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV-related chronic disease. MMWR. October 16, 1998. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00055154.htm. Accessed March 5, 2014.

- Donahue JG, Muñoz A, Ness PM, et al. The declining risk of post-transfusion hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(6):369-373.

- Pomper GJ, Wu Y, Snyder EL. Risks of transfusion-transmitted infections: 2003. Curr Opin Hematol. 2003;10(6):412-418.

- Tokars JI, Miller ER, Alter MJ, Arduino MJ. National surveillance of dialysis associated diseases in the United States, 1995. ASAIO J. 1998;44(1):98-107.

- Finelli L, Miller JT, Tokars JI, Alter MJ, Arduino MJ. National surveillance of dialysis-associated diseases in the United States, 2002. Semin Dial. 2005;18(1):52-61.

- Natov S, Pereira BJG. Hepatitis C virus infection in patients on maintenance dialysis. UpToDate. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/hepatitis-c-virus-infection-in-patients-on-maintenance-dialysis?source=search_result&search=Hepatitis+C+virus+infection+in+patients+on+maintenance+dialysis.&selectedTitle=1~150. Accessed March 5, 2014.

- Moyer VA, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(5):349-357.

- Staples CT II, Rimland D, Dudas D. Hepatitis C in the HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) Atlanta V.A. (Veterans Affairs Medical Center) Cohort Study (HAVACS): the effect of coinfection on survival. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29(1):150-154.

- Sherman KE, Rouster SD, Chung RT, Rajicic N. Hepatitis C virus prevalence among patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus: a cross-sectional analysis of the U.S. adult AIDS clinical trials group. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(6):831-837.

- Averhoff FM, Glass N, Holtzman D. Global burden of hepatitis C: considerations for healthcare providers in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55 Suppl 1:S10-15.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and control of infections with hepatitis viruses in correctional settings. MMWR. January 24, 2003. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5201a1.htm. Accessed March 5, 2014.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Locations and reasons for initial testing for hepatitis C infection—chronic hepatitis cohort study, United States, 2006-2010. MMWR. August 16, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6232a3.htm?s_cid=mm6232a3_w. Accessed March 5, 2014.