User login

Home-Based Primary Care (HBPC) is a unique interdisciplinary program within the Veteran’s Health Administration (VHA) that specifically targets veterans with complex, chronic disabling diseases who have difficulty traveling to a VHA facility.1 Veterans are provided comprehensive longitudinal primary care in their homes, with the goal of maximizing the veteran’s independence. Clinical pharmacists are known as medication experts and have an essential role within interdisciplinary teams, including HBPC, improving medication safety, and decreasing inappropriate prescribing practices.2,3 Clinical pharmacy specialists (CPSs) within the VHA work collaboratively but autonomously as advanced practice providers assisting with the pharmacologic management of many diseases and chronic conditions. The remainder of this article will refer to the HBPC pharmacist as a CPS.

The CPS is actively involved in providing comprehensive medication management (CMM) services across VHA and has the expertise to effectively assist veterans in achieving targeted clinical outcomes. While the value and role of CPSs in the primary care setting are described extensively in the literature, data regarding the CPS in HBPC are limited.4-6 Therefore, the purpose of the assessment was to evaluate the status of the HBPC pharmacy workforce, identify current pharmacist activities and strong practices, and clarify national variations among programs. Future use of this analysis may assist with standardization of the HBPC CPS role and development of business rules in combination with a workload-based staffing model tool.

Background

The role of the pharmacist in the HBPC setting has evolved from providing basic medication therapy reviews to an advanced role providing CMM services under a VHA scope of practice (SOP), which outlines 8 functions that may be authorized, including medication prescriptive authority.7 The SOP may be disease specific (limited) but is increasingly transitioning to have a practice-area scope (global), which is consistent with other VHA advanced practice providers.7 Effective use of a CPS in this role allows for optimization of CMM and increasing veteran access to VHA care.

The VHA employed 7,285 pharmacists in 2014.8 Many were considered CPSs with prescriptive authority. These pharmacists were responsible for ordering more than 1.7 million distinct prescriptions across the VHA in fiscal year 2014, which represented 2.6% of the total prescriptions that year.7 A 2007 VHA study also demonstrated both an increase in appropriate prescribing practices and improved medication use when CPSs worked in collaboration with the HBPC team.9 With this evolution of VHA pharmacists, there has been an increase in the use of CPSs in HBPC and changes in staffing ratios to allow for additional clinical activities and comprehensive patient care provision.1

The HBPC model serves a complex population in which each veteran has about 8 chronic conditions.1,10 An interdisciplinary team consisting of various health care professionals, such as physicians, nurse practitioners, nurses, social workers, registered dietitians, psychologists, rehabilitation therapists, pharmacists, etc, work collaboratively to care for these veterans in the patient’s home. This team is a type of patient-centered medical home (PCMH) that focuses on providing primary care services to an at-risk veteran population who have difficulty leaving the home.1 Home-based primary care has been shown to be cost-effective, reducing average annual cost of health care by up to 24%.10 Another study showed that patients using HBPC had a 27% reduction in hospital admissions and 69% reduction in inpatient hospital days when compared with patients who were not using HBPC.11

The interdisciplinary team meets at least once weekly to discuss and design individualized care plans for veterans enrolled in the program. It is desirable for pharmacists on these teams to have special expertise and certification in geriatric pharmacotherapy and chronic disease management (eg, board-certified geriatric pharmacist [BCGP], board-certified pharmacotherapy specialist [BCPS], or board-certified ambulatory care pharmacist [BCACP]) due to the complexity of comorbidities of these veterans.12 Additional education such as postgraduate pharmacy residency training also is beneficial for CPSs in this setting.

The CPS proactively performs CMM that is often greater in scope than a targeted disease review due to multiple comorbid conditions that are often present within veteran patients.1 These comprehensive medication reviews are considered a core function and must be performed on enrollment in HBPC, quarterly, and when clinically indicated or requested by the team.13 Sufficient time must be allocated to the CPS in order to provide these high-quality medication reviews. Additional core functions of the CPS are outlined in the functional statement and/or SOP, but responsibilities include CMM and disease management. This typically consists of prescribing and/or adjusting medications, as well as providing patient and caregiver education, which can be performed either face-to-face or via telehealth visits (eg, telephone and video). A CPS also may make home visits to assess the veteran, either independently or with other disciplines of the HBPC team.

The HBPC Subject Matter Expert (SME) workgroup was chartered by the Veterans Affairs Central Office (VACO) Pharmacy Benefits Management Service (PBM) Clinical Pharmacy Practice Office (CPPO) to explore pharmacy practice changes in the HBPC setting. This workgroup serves as clinical practice leadership within the HBPC setting to provide expertise and lead initiatives supporting the advanced practice role of the HBPC CPS.

As HBPC programs expanded throughout VHA, it was paramount to determine the current state of HBPC pharmacy practice by collecting necessary data points to assess uniformity and better understand opportunities for practice standardization. The SME workgroup developed a voluntary yet comprehensive survey assessment that served to proactively assess the future of HBPC pharmacy.

Methods

The HBPC SME workgroup, in conjunction with CPPO, developed the assessment. Questions were designed and tested within a small group of CPSs and then distributed electronically. In August 2014, the assessment was e-mailed to all 21 VHA service areas with an active HBPC program, and responses were collected through a Microsoft SharePoint (Redmond, WA) survey. A response was requested from chiefs of pharmacy, clinical pharmacy leadership, or a representative.

This voluntary assessment contained 24 multipart questions related to background information of HBPC programs and clinical pharmacy services. Duplicate responses were consolidated and clarified with individual sites post hoc.

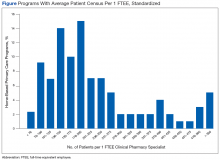

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze responses. To standardize the comparison across sites with a variety of full-time equivalent employees (FTEEs), the average patient census was divided by the CPS FTEE allocated to the programs at that site. For example, if a site reported 316 patients with 0.25 CPS FTEE, a standardized ratio for this site was 1,264 patients per FTEE. If a patient census range was reported, the median number would be used.

Results

The team received responses from 130 of 141 VHA facilities (92%), encompassing 270 CPSs. A total of 168.75 FTEEs were officially designated as HBPC CPSs. All 21 VHA service areas at the time were represented. The majority of responding programs (67%) had < 1 CPS FTEE allocated to HBPC; many of these CPSs were working in other pharmacy areas but were only dedicated to HBPC part-time.

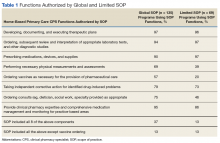

Nearly 90% of CPSs completed postgraduate year 1 residency training. Fifty-seven percent of CPSs held advanced certifications, such as BCGP, BCACP, or BCPS. Sixty-two percent of CPSs with these specialized board certifications had residency training. Use of a SOP was reported by 76% of CPSs, and 66% of these had a global practice-area scope. Table 1 outlines the functions authorized by a global or limited SOP.6

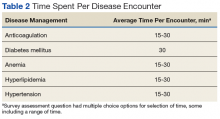

Overall, 52% of sites reported CPS involvement in CMM of primarily anticoagulation, diabetes mellitus (DM), anemia, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension. The reported average time spent for each disease encounter is delineated in Table 2.

Thirty-five percent of sites reported CPS participation in home visits, and the majority of those completed between 1 and 10 home visits per month. The types of interventions provided often included medication education, assessment of medication adherence, and CMM for DM, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, etc. Multiple interventions often were made during each home visit.

The workload of medication reviews was divided among multiple CPSs in 55% of the programs. The majority of programs completed fewer than 20 initial medication reviews per month and between 21 and 80 quarterly medication reviews per month (81% and 62%, respectively). The average time for a CPS to complete initial medication reviews was 78 minutes and 42 minutes for quarterly medication reviews.

Sites with CPSs that held a SOP (76%) took an average of 83 minutes to complete an initial medication review and 48 minutes to complete a quarterly review. Sites with CPSs without a SOP (24%) took an average of 72 minutes to complete an initial medication review and 36 minutes to complete a quarterly review. Many CPSs allocate ≤ 20 hours per month on routine pharmacy functions (eg, prescription verification, dispensing activities, nonformulary medication requests) and ≤ 20 hours per month on nonpatient care activities (eg, education, medication use evaluations, training, projects), 67% and 82%, respectively.

Ninety-seven percent of CPSs actively attended weekly HBPC program interdisciplinary team (IDT) meetings, with 67% attending 1 weekly IDT meeting and 30% attending 2 to 5 weekly IDT meetings. Time spent attending IDT and roundtable discussions averaged 3.5 hours per week. Multiple programs noted growth within the 12 months preceding the survey, as 37 sites were granted approval for a total of 29.75 additional CPS FTEEs, and an additional 10 sites had a total of 9.25 FTEEs pending approval.

Discussion

Analysis of this assessment allowed the HBPC CPS SME workgroup to identify strong practices and variations in individual HBPC pharmacy programs. The majority of CPSs (66%) are using global, practice area-based SOPs, which allows more autonomy via direct patient care to veterans through CMM and home visits. This trend suggests the focus of the HBPC CPS role has expanded beyond traditional pharmacist activities. These global SOPs result in a higher yield of CPS functions, such as developing, documenting, and executing therapeutic plans and prescribing medications (Table 1). A higher percentage of CPSs with a practice area-based SOP were authorized to perform all 8 functions. Therefore, increased use of practice area-based SOPs and the expansion of the HBPC CPS role can support the team and increase clinical services available to veterans.

Clinical pharmacy specialists using SOPs take longer to complete medication reviews compared with those not using SOPs. Although the assessment was not designed to evaluate the reasons for these time differences, post-hoc follow-up clarification with individual sites determined CPS use of a SOP can lend to a more time-intensive and comprehensive medication review. This may lead to more optimized and safe medication regimens and elimination of unnecessary and/or inappropriate medications for HBPC veterans.

While only 35% of pharmacists were participating in the home visits at the time of this assessment, this is another area to explore as an opportunity to expand CMM. Although the assessment showed the majority of these home visits addressed medication education and adherence, programs may find it advantageous to provide CPS home visits for veterans identified as high risk or requiring specialized CMM. Additional data are needed regarding the ideal population to target for CPS home visits, as well as the estimated benefits of conducting home visits, such as outcomes and efficiency.

With growth noted in multiple programs, HBPC leadership should continue to encourage expanded pharmacist roles at an advanced practice level with SOPs, to provide veteran-centered care. This practice allows the team to concentrate efforts on patient acuity while increasing veteran access to VHA care. Additional CPS FTEEs are necessary to allow for expansion of the HBPC CPS role. The data also demonstrate HBPC often uses a part-time workforce where pharmacists are assigned to HBPC < 40 hours per week, and multiple pharmacists may be used to fulfill 1 CPS FTEE position. Home-Based Primary Care programs are encouraged to consolidate the number of CPSs involved as core individuals to promote continuity and avoid fragmented care.

Limitations

One limitation of the assessment is that the questions were designed and tested by a small group of CPSs, which may have led to response bias and potential misinterpretation of some questions. Time spent on medication reviews may have been underestimated, as some sites reported the maximum allowable workload credit time rather than actual time spent. Recall bias also is a limitation because the assessment relied on the recollection of the CPS or chief of pharmacy. Additionally, while the assessment focused on quantity and time spent on medication reviews, it was not designed to evaluate quality. Examination of what constitutes a high-quality medication review would be helpful to provide guidance and standardize care across the VHA.

Conclusion

Clinical pharmacy specialists practicing in the VHA HBPC setting are highly trained clinicians. A significant percentage of CPSs practice with a SOP that includes prescriptive privileges. However, variations in practice and function exist in the system. This presents an excellent opportunity for future standardization and promotion of the highest and best use of the CPS to improve quality of care for HBPC. With the expansion of the CPS role, there is potential for pharmacists to increase clinical activities and improve care for home-based veterans. The CPPO HBPC SME workgroup will continue to examine and explore the CPS role in this practice setting, develop staffing and practice guidance documents, and assess the benefit of CPS home visits.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA Directive 1141.01: home-based primary care special population aligned care team program. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=5417. Updated September 20, 2017. Accessed April 3, 2018.

2. Brahmbhatt M, Palla K, Kossifologos A, Mitchell D, Lee T. Appropriateness of medication prescribing using the STOPP/START criteria in veterans receiving home-based primary care. Consult Pharm. 2013;28(6):361-369.

3. Hanlon JT, Weinberger M, Samsa GP, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a clinical pharmacist intervention to improve inappropriate prescribing in elderly outpatients with polypharmacy. Am J Med. 1996;100(4):428-437.

4. Rose AJ, McCullough MB, Carter BL, Rudin RS. The clinical pharmacy specialist: part of the solution. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(4):375–377.

5. Giberson S, Yoder S, Lee MP. Improving patient and health system outcomes through advanced pharmacy practice: a report to the U.S. Surgeon General 2011. https://www.accp.com/docs/positions/misc/Improving_Patient_and_Health_System_Outcomes.pdf. Published December 2011. Accessed April 3, 2018.

6. Lee AJ, Boro MS, Knapp KK, Meier JL, Korman NE. Clinical and economic outcomes of pharmacist recommendations in a Veterans Affairs medical center. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002;59(21):2070–2077.

7. Ourth H, Groppi J, Morreale AP, Quicci-Roberts K. Clinical pharmacist prescribing activities in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(18):1406-1415.

8. US Department of Veteran Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Healthcare Talent Management Workforce Management & Consulting Office. VHA workforce planning report 2015.https://www.vacareers.va.gov/assets/common/print/2015_VHA_Workforce_Succession_Strategic_Plan.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed April 3, 2018.

9. Davis RG, Hepfinger CA, Sauer KA, Wilhardt MS. Retrospective evaluation of medication appropriateness and clinical pharmacist drug therapy recommendations for home-based primary care veterans. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;5(1):40-47.

10. Beales JL, Edes T. Veteran’s Affairs home based primary care. Clin Geriatr Med. 2009;25(1):149-154.

11. Cooper DF, Granadillo OR, Stacey CM. Home-based primary care: the care of the veteran at home. Home Healthc Nurse. 2007;25(5):315-322.

12. Pradel FG, Palumbo FB, Flowers L, et al. White paper: value of specialty certification in pharmacy. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2004;44(5):612-620.

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Handbook 1108.11(1). Clinical pharmacy services. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=3120. Updated June 29, 2017. Accessed April 3, 2018

Home-Based Primary Care (HBPC) is a unique interdisciplinary program within the Veteran’s Health Administration (VHA) that specifically targets veterans with complex, chronic disabling diseases who have difficulty traveling to a VHA facility.1 Veterans are provided comprehensive longitudinal primary care in their homes, with the goal of maximizing the veteran’s independence. Clinical pharmacists are known as medication experts and have an essential role within interdisciplinary teams, including HBPC, improving medication safety, and decreasing inappropriate prescribing practices.2,3 Clinical pharmacy specialists (CPSs) within the VHA work collaboratively but autonomously as advanced practice providers assisting with the pharmacologic management of many diseases and chronic conditions. The remainder of this article will refer to the HBPC pharmacist as a CPS.

The CPS is actively involved in providing comprehensive medication management (CMM) services across VHA and has the expertise to effectively assist veterans in achieving targeted clinical outcomes. While the value and role of CPSs in the primary care setting are described extensively in the literature, data regarding the CPS in HBPC are limited.4-6 Therefore, the purpose of the assessment was to evaluate the status of the HBPC pharmacy workforce, identify current pharmacist activities and strong practices, and clarify national variations among programs. Future use of this analysis may assist with standardization of the HBPC CPS role and development of business rules in combination with a workload-based staffing model tool.

Background

The role of the pharmacist in the HBPC setting has evolved from providing basic medication therapy reviews to an advanced role providing CMM services under a VHA scope of practice (SOP), which outlines 8 functions that may be authorized, including medication prescriptive authority.7 The SOP may be disease specific (limited) but is increasingly transitioning to have a practice-area scope (global), which is consistent with other VHA advanced practice providers.7 Effective use of a CPS in this role allows for optimization of CMM and increasing veteran access to VHA care.

The VHA employed 7,285 pharmacists in 2014.8 Many were considered CPSs with prescriptive authority. These pharmacists were responsible for ordering more than 1.7 million distinct prescriptions across the VHA in fiscal year 2014, which represented 2.6% of the total prescriptions that year.7 A 2007 VHA study also demonstrated both an increase in appropriate prescribing practices and improved medication use when CPSs worked in collaboration with the HBPC team.9 With this evolution of VHA pharmacists, there has been an increase in the use of CPSs in HBPC and changes in staffing ratios to allow for additional clinical activities and comprehensive patient care provision.1

The HBPC model serves a complex population in which each veteran has about 8 chronic conditions.1,10 An interdisciplinary team consisting of various health care professionals, such as physicians, nurse practitioners, nurses, social workers, registered dietitians, psychologists, rehabilitation therapists, pharmacists, etc, work collaboratively to care for these veterans in the patient’s home. This team is a type of patient-centered medical home (PCMH) that focuses on providing primary care services to an at-risk veteran population who have difficulty leaving the home.1 Home-based primary care has been shown to be cost-effective, reducing average annual cost of health care by up to 24%.10 Another study showed that patients using HBPC had a 27% reduction in hospital admissions and 69% reduction in inpatient hospital days when compared with patients who were not using HBPC.11

The interdisciplinary team meets at least once weekly to discuss and design individualized care plans for veterans enrolled in the program. It is desirable for pharmacists on these teams to have special expertise and certification in geriatric pharmacotherapy and chronic disease management (eg, board-certified geriatric pharmacist [BCGP], board-certified pharmacotherapy specialist [BCPS], or board-certified ambulatory care pharmacist [BCACP]) due to the complexity of comorbidities of these veterans.12 Additional education such as postgraduate pharmacy residency training also is beneficial for CPSs in this setting.

The CPS proactively performs CMM that is often greater in scope than a targeted disease review due to multiple comorbid conditions that are often present within veteran patients.1 These comprehensive medication reviews are considered a core function and must be performed on enrollment in HBPC, quarterly, and when clinically indicated or requested by the team.13 Sufficient time must be allocated to the CPS in order to provide these high-quality medication reviews. Additional core functions of the CPS are outlined in the functional statement and/or SOP, but responsibilities include CMM and disease management. This typically consists of prescribing and/or adjusting medications, as well as providing patient and caregiver education, which can be performed either face-to-face or via telehealth visits (eg, telephone and video). A CPS also may make home visits to assess the veteran, either independently or with other disciplines of the HBPC team.

The HBPC Subject Matter Expert (SME) workgroup was chartered by the Veterans Affairs Central Office (VACO) Pharmacy Benefits Management Service (PBM) Clinical Pharmacy Practice Office (CPPO) to explore pharmacy practice changes in the HBPC setting. This workgroup serves as clinical practice leadership within the HBPC setting to provide expertise and lead initiatives supporting the advanced practice role of the HBPC CPS.

As HBPC programs expanded throughout VHA, it was paramount to determine the current state of HBPC pharmacy practice by collecting necessary data points to assess uniformity and better understand opportunities for practice standardization. The SME workgroup developed a voluntary yet comprehensive survey assessment that served to proactively assess the future of HBPC pharmacy.

Methods

The HBPC SME workgroup, in conjunction with CPPO, developed the assessment. Questions were designed and tested within a small group of CPSs and then distributed electronically. In August 2014, the assessment was e-mailed to all 21 VHA service areas with an active HBPC program, and responses were collected through a Microsoft SharePoint (Redmond, WA) survey. A response was requested from chiefs of pharmacy, clinical pharmacy leadership, or a representative.

This voluntary assessment contained 24 multipart questions related to background information of HBPC programs and clinical pharmacy services. Duplicate responses were consolidated and clarified with individual sites post hoc.

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze responses. To standardize the comparison across sites with a variety of full-time equivalent employees (FTEEs), the average patient census was divided by the CPS FTEE allocated to the programs at that site. For example, if a site reported 316 patients with 0.25 CPS FTEE, a standardized ratio for this site was 1,264 patients per FTEE. If a patient census range was reported, the median number would be used.

Results

The team received responses from 130 of 141 VHA facilities (92%), encompassing 270 CPSs. A total of 168.75 FTEEs were officially designated as HBPC CPSs. All 21 VHA service areas at the time were represented. The majority of responding programs (67%) had < 1 CPS FTEE allocated to HBPC; many of these CPSs were working in other pharmacy areas but were only dedicated to HBPC part-time.

Nearly 90% of CPSs completed postgraduate year 1 residency training. Fifty-seven percent of CPSs held advanced certifications, such as BCGP, BCACP, or BCPS. Sixty-two percent of CPSs with these specialized board certifications had residency training. Use of a SOP was reported by 76% of CPSs, and 66% of these had a global practice-area scope. Table 1 outlines the functions authorized by a global or limited SOP.6

Overall, 52% of sites reported CPS involvement in CMM of primarily anticoagulation, diabetes mellitus (DM), anemia, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension. The reported average time spent for each disease encounter is delineated in Table 2.

Thirty-five percent of sites reported CPS participation in home visits, and the majority of those completed between 1 and 10 home visits per month. The types of interventions provided often included medication education, assessment of medication adherence, and CMM for DM, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, etc. Multiple interventions often were made during each home visit.

The workload of medication reviews was divided among multiple CPSs in 55% of the programs. The majority of programs completed fewer than 20 initial medication reviews per month and between 21 and 80 quarterly medication reviews per month (81% and 62%, respectively). The average time for a CPS to complete initial medication reviews was 78 minutes and 42 minutes for quarterly medication reviews.

Sites with CPSs that held a SOP (76%) took an average of 83 minutes to complete an initial medication review and 48 minutes to complete a quarterly review. Sites with CPSs without a SOP (24%) took an average of 72 minutes to complete an initial medication review and 36 minutes to complete a quarterly review. Many CPSs allocate ≤ 20 hours per month on routine pharmacy functions (eg, prescription verification, dispensing activities, nonformulary medication requests) and ≤ 20 hours per month on nonpatient care activities (eg, education, medication use evaluations, training, projects), 67% and 82%, respectively.

Ninety-seven percent of CPSs actively attended weekly HBPC program interdisciplinary team (IDT) meetings, with 67% attending 1 weekly IDT meeting and 30% attending 2 to 5 weekly IDT meetings. Time spent attending IDT and roundtable discussions averaged 3.5 hours per week. Multiple programs noted growth within the 12 months preceding the survey, as 37 sites were granted approval for a total of 29.75 additional CPS FTEEs, and an additional 10 sites had a total of 9.25 FTEEs pending approval.

Discussion

Analysis of this assessment allowed the HBPC CPS SME workgroup to identify strong practices and variations in individual HBPC pharmacy programs. The majority of CPSs (66%) are using global, practice area-based SOPs, which allows more autonomy via direct patient care to veterans through CMM and home visits. This trend suggests the focus of the HBPC CPS role has expanded beyond traditional pharmacist activities. These global SOPs result in a higher yield of CPS functions, such as developing, documenting, and executing therapeutic plans and prescribing medications (Table 1). A higher percentage of CPSs with a practice area-based SOP were authorized to perform all 8 functions. Therefore, increased use of practice area-based SOPs and the expansion of the HBPC CPS role can support the team and increase clinical services available to veterans.

Clinical pharmacy specialists using SOPs take longer to complete medication reviews compared with those not using SOPs. Although the assessment was not designed to evaluate the reasons for these time differences, post-hoc follow-up clarification with individual sites determined CPS use of a SOP can lend to a more time-intensive and comprehensive medication review. This may lead to more optimized and safe medication regimens and elimination of unnecessary and/or inappropriate medications for HBPC veterans.

While only 35% of pharmacists were participating in the home visits at the time of this assessment, this is another area to explore as an opportunity to expand CMM. Although the assessment showed the majority of these home visits addressed medication education and adherence, programs may find it advantageous to provide CPS home visits for veterans identified as high risk or requiring specialized CMM. Additional data are needed regarding the ideal population to target for CPS home visits, as well as the estimated benefits of conducting home visits, such as outcomes and efficiency.

With growth noted in multiple programs, HBPC leadership should continue to encourage expanded pharmacist roles at an advanced practice level with SOPs, to provide veteran-centered care. This practice allows the team to concentrate efforts on patient acuity while increasing veteran access to VHA care. Additional CPS FTEEs are necessary to allow for expansion of the HBPC CPS role. The data also demonstrate HBPC often uses a part-time workforce where pharmacists are assigned to HBPC < 40 hours per week, and multiple pharmacists may be used to fulfill 1 CPS FTEE position. Home-Based Primary Care programs are encouraged to consolidate the number of CPSs involved as core individuals to promote continuity and avoid fragmented care.

Limitations

One limitation of the assessment is that the questions were designed and tested by a small group of CPSs, which may have led to response bias and potential misinterpretation of some questions. Time spent on medication reviews may have been underestimated, as some sites reported the maximum allowable workload credit time rather than actual time spent. Recall bias also is a limitation because the assessment relied on the recollection of the CPS or chief of pharmacy. Additionally, while the assessment focused on quantity and time spent on medication reviews, it was not designed to evaluate quality. Examination of what constitutes a high-quality medication review would be helpful to provide guidance and standardize care across the VHA.

Conclusion

Clinical pharmacy specialists practicing in the VHA HBPC setting are highly trained clinicians. A significant percentage of CPSs practice with a SOP that includes prescriptive privileges. However, variations in practice and function exist in the system. This presents an excellent opportunity for future standardization and promotion of the highest and best use of the CPS to improve quality of care for HBPC. With the expansion of the CPS role, there is potential for pharmacists to increase clinical activities and improve care for home-based veterans. The CPPO HBPC SME workgroup will continue to examine and explore the CPS role in this practice setting, develop staffing and practice guidance documents, and assess the benefit of CPS home visits.

Home-Based Primary Care (HBPC) is a unique interdisciplinary program within the Veteran’s Health Administration (VHA) that specifically targets veterans with complex, chronic disabling diseases who have difficulty traveling to a VHA facility.1 Veterans are provided comprehensive longitudinal primary care in their homes, with the goal of maximizing the veteran’s independence. Clinical pharmacists are known as medication experts and have an essential role within interdisciplinary teams, including HBPC, improving medication safety, and decreasing inappropriate prescribing practices.2,3 Clinical pharmacy specialists (CPSs) within the VHA work collaboratively but autonomously as advanced practice providers assisting with the pharmacologic management of many diseases and chronic conditions. The remainder of this article will refer to the HBPC pharmacist as a CPS.

The CPS is actively involved in providing comprehensive medication management (CMM) services across VHA and has the expertise to effectively assist veterans in achieving targeted clinical outcomes. While the value and role of CPSs in the primary care setting are described extensively in the literature, data regarding the CPS in HBPC are limited.4-6 Therefore, the purpose of the assessment was to evaluate the status of the HBPC pharmacy workforce, identify current pharmacist activities and strong practices, and clarify national variations among programs. Future use of this analysis may assist with standardization of the HBPC CPS role and development of business rules in combination with a workload-based staffing model tool.

Background

The role of the pharmacist in the HBPC setting has evolved from providing basic medication therapy reviews to an advanced role providing CMM services under a VHA scope of practice (SOP), which outlines 8 functions that may be authorized, including medication prescriptive authority.7 The SOP may be disease specific (limited) but is increasingly transitioning to have a practice-area scope (global), which is consistent with other VHA advanced practice providers.7 Effective use of a CPS in this role allows for optimization of CMM and increasing veteran access to VHA care.

The VHA employed 7,285 pharmacists in 2014.8 Many were considered CPSs with prescriptive authority. These pharmacists were responsible for ordering more than 1.7 million distinct prescriptions across the VHA in fiscal year 2014, which represented 2.6% of the total prescriptions that year.7 A 2007 VHA study also demonstrated both an increase in appropriate prescribing practices and improved medication use when CPSs worked in collaboration with the HBPC team.9 With this evolution of VHA pharmacists, there has been an increase in the use of CPSs in HBPC and changes in staffing ratios to allow for additional clinical activities and comprehensive patient care provision.1

The HBPC model serves a complex population in which each veteran has about 8 chronic conditions.1,10 An interdisciplinary team consisting of various health care professionals, such as physicians, nurse practitioners, nurses, social workers, registered dietitians, psychologists, rehabilitation therapists, pharmacists, etc, work collaboratively to care for these veterans in the patient’s home. This team is a type of patient-centered medical home (PCMH) that focuses on providing primary care services to an at-risk veteran population who have difficulty leaving the home.1 Home-based primary care has been shown to be cost-effective, reducing average annual cost of health care by up to 24%.10 Another study showed that patients using HBPC had a 27% reduction in hospital admissions and 69% reduction in inpatient hospital days when compared with patients who were not using HBPC.11

The interdisciplinary team meets at least once weekly to discuss and design individualized care plans for veterans enrolled in the program. It is desirable for pharmacists on these teams to have special expertise and certification in geriatric pharmacotherapy and chronic disease management (eg, board-certified geriatric pharmacist [BCGP], board-certified pharmacotherapy specialist [BCPS], or board-certified ambulatory care pharmacist [BCACP]) due to the complexity of comorbidities of these veterans.12 Additional education such as postgraduate pharmacy residency training also is beneficial for CPSs in this setting.

The CPS proactively performs CMM that is often greater in scope than a targeted disease review due to multiple comorbid conditions that are often present within veteran patients.1 These comprehensive medication reviews are considered a core function and must be performed on enrollment in HBPC, quarterly, and when clinically indicated or requested by the team.13 Sufficient time must be allocated to the CPS in order to provide these high-quality medication reviews. Additional core functions of the CPS are outlined in the functional statement and/or SOP, but responsibilities include CMM and disease management. This typically consists of prescribing and/or adjusting medications, as well as providing patient and caregiver education, which can be performed either face-to-face or via telehealth visits (eg, telephone and video). A CPS also may make home visits to assess the veteran, either independently or with other disciplines of the HBPC team.

The HBPC Subject Matter Expert (SME) workgroup was chartered by the Veterans Affairs Central Office (VACO) Pharmacy Benefits Management Service (PBM) Clinical Pharmacy Practice Office (CPPO) to explore pharmacy practice changes in the HBPC setting. This workgroup serves as clinical practice leadership within the HBPC setting to provide expertise and lead initiatives supporting the advanced practice role of the HBPC CPS.

As HBPC programs expanded throughout VHA, it was paramount to determine the current state of HBPC pharmacy practice by collecting necessary data points to assess uniformity and better understand opportunities for practice standardization. The SME workgroup developed a voluntary yet comprehensive survey assessment that served to proactively assess the future of HBPC pharmacy.

Methods

The HBPC SME workgroup, in conjunction with CPPO, developed the assessment. Questions were designed and tested within a small group of CPSs and then distributed electronically. In August 2014, the assessment was e-mailed to all 21 VHA service areas with an active HBPC program, and responses were collected through a Microsoft SharePoint (Redmond, WA) survey. A response was requested from chiefs of pharmacy, clinical pharmacy leadership, or a representative.

This voluntary assessment contained 24 multipart questions related to background information of HBPC programs and clinical pharmacy services. Duplicate responses were consolidated and clarified with individual sites post hoc.

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze responses. To standardize the comparison across sites with a variety of full-time equivalent employees (FTEEs), the average patient census was divided by the CPS FTEE allocated to the programs at that site. For example, if a site reported 316 patients with 0.25 CPS FTEE, a standardized ratio for this site was 1,264 patients per FTEE. If a patient census range was reported, the median number would be used.

Results

The team received responses from 130 of 141 VHA facilities (92%), encompassing 270 CPSs. A total of 168.75 FTEEs were officially designated as HBPC CPSs. All 21 VHA service areas at the time were represented. The majority of responding programs (67%) had < 1 CPS FTEE allocated to HBPC; many of these CPSs were working in other pharmacy areas but were only dedicated to HBPC part-time.

Nearly 90% of CPSs completed postgraduate year 1 residency training. Fifty-seven percent of CPSs held advanced certifications, such as BCGP, BCACP, or BCPS. Sixty-two percent of CPSs with these specialized board certifications had residency training. Use of a SOP was reported by 76% of CPSs, and 66% of these had a global practice-area scope. Table 1 outlines the functions authorized by a global or limited SOP.6

Overall, 52% of sites reported CPS involvement in CMM of primarily anticoagulation, diabetes mellitus (DM), anemia, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension. The reported average time spent for each disease encounter is delineated in Table 2.

Thirty-five percent of sites reported CPS participation in home visits, and the majority of those completed between 1 and 10 home visits per month. The types of interventions provided often included medication education, assessment of medication adherence, and CMM for DM, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, etc. Multiple interventions often were made during each home visit.

The workload of medication reviews was divided among multiple CPSs in 55% of the programs. The majority of programs completed fewer than 20 initial medication reviews per month and between 21 and 80 quarterly medication reviews per month (81% and 62%, respectively). The average time for a CPS to complete initial medication reviews was 78 minutes and 42 minutes for quarterly medication reviews.

Sites with CPSs that held a SOP (76%) took an average of 83 minutes to complete an initial medication review and 48 minutes to complete a quarterly review. Sites with CPSs without a SOP (24%) took an average of 72 minutes to complete an initial medication review and 36 minutes to complete a quarterly review. Many CPSs allocate ≤ 20 hours per month on routine pharmacy functions (eg, prescription verification, dispensing activities, nonformulary medication requests) and ≤ 20 hours per month on nonpatient care activities (eg, education, medication use evaluations, training, projects), 67% and 82%, respectively.

Ninety-seven percent of CPSs actively attended weekly HBPC program interdisciplinary team (IDT) meetings, with 67% attending 1 weekly IDT meeting and 30% attending 2 to 5 weekly IDT meetings. Time spent attending IDT and roundtable discussions averaged 3.5 hours per week. Multiple programs noted growth within the 12 months preceding the survey, as 37 sites were granted approval for a total of 29.75 additional CPS FTEEs, and an additional 10 sites had a total of 9.25 FTEEs pending approval.

Discussion

Analysis of this assessment allowed the HBPC CPS SME workgroup to identify strong practices and variations in individual HBPC pharmacy programs. The majority of CPSs (66%) are using global, practice area-based SOPs, which allows more autonomy via direct patient care to veterans through CMM and home visits. This trend suggests the focus of the HBPC CPS role has expanded beyond traditional pharmacist activities. These global SOPs result in a higher yield of CPS functions, such as developing, documenting, and executing therapeutic plans and prescribing medications (Table 1). A higher percentage of CPSs with a practice area-based SOP were authorized to perform all 8 functions. Therefore, increased use of practice area-based SOPs and the expansion of the HBPC CPS role can support the team and increase clinical services available to veterans.

Clinical pharmacy specialists using SOPs take longer to complete medication reviews compared with those not using SOPs. Although the assessment was not designed to evaluate the reasons for these time differences, post-hoc follow-up clarification with individual sites determined CPS use of a SOP can lend to a more time-intensive and comprehensive medication review. This may lead to more optimized and safe medication regimens and elimination of unnecessary and/or inappropriate medications for HBPC veterans.

While only 35% of pharmacists were participating in the home visits at the time of this assessment, this is another area to explore as an opportunity to expand CMM. Although the assessment showed the majority of these home visits addressed medication education and adherence, programs may find it advantageous to provide CPS home visits for veterans identified as high risk or requiring specialized CMM. Additional data are needed regarding the ideal population to target for CPS home visits, as well as the estimated benefits of conducting home visits, such as outcomes and efficiency.

With growth noted in multiple programs, HBPC leadership should continue to encourage expanded pharmacist roles at an advanced practice level with SOPs, to provide veteran-centered care. This practice allows the team to concentrate efforts on patient acuity while increasing veteran access to VHA care. Additional CPS FTEEs are necessary to allow for expansion of the HBPC CPS role. The data also demonstrate HBPC often uses a part-time workforce where pharmacists are assigned to HBPC < 40 hours per week, and multiple pharmacists may be used to fulfill 1 CPS FTEE position. Home-Based Primary Care programs are encouraged to consolidate the number of CPSs involved as core individuals to promote continuity and avoid fragmented care.

Limitations

One limitation of the assessment is that the questions were designed and tested by a small group of CPSs, which may have led to response bias and potential misinterpretation of some questions. Time spent on medication reviews may have been underestimated, as some sites reported the maximum allowable workload credit time rather than actual time spent. Recall bias also is a limitation because the assessment relied on the recollection of the CPS or chief of pharmacy. Additionally, while the assessment focused on quantity and time spent on medication reviews, it was not designed to evaluate quality. Examination of what constitutes a high-quality medication review would be helpful to provide guidance and standardize care across the VHA.

Conclusion

Clinical pharmacy specialists practicing in the VHA HBPC setting are highly trained clinicians. A significant percentage of CPSs practice with a SOP that includes prescriptive privileges. However, variations in practice and function exist in the system. This presents an excellent opportunity for future standardization and promotion of the highest and best use of the CPS to improve quality of care for HBPC. With the expansion of the CPS role, there is potential for pharmacists to increase clinical activities and improve care for home-based veterans. The CPPO HBPC SME workgroup will continue to examine and explore the CPS role in this practice setting, develop staffing and practice guidance documents, and assess the benefit of CPS home visits.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA Directive 1141.01: home-based primary care special population aligned care team program. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=5417. Updated September 20, 2017. Accessed April 3, 2018.

2. Brahmbhatt M, Palla K, Kossifologos A, Mitchell D, Lee T. Appropriateness of medication prescribing using the STOPP/START criteria in veterans receiving home-based primary care. Consult Pharm. 2013;28(6):361-369.

3. Hanlon JT, Weinberger M, Samsa GP, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a clinical pharmacist intervention to improve inappropriate prescribing in elderly outpatients with polypharmacy. Am J Med. 1996;100(4):428-437.

4. Rose AJ, McCullough MB, Carter BL, Rudin RS. The clinical pharmacy specialist: part of the solution. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(4):375–377.

5. Giberson S, Yoder S, Lee MP. Improving patient and health system outcomes through advanced pharmacy practice: a report to the U.S. Surgeon General 2011. https://www.accp.com/docs/positions/misc/Improving_Patient_and_Health_System_Outcomes.pdf. Published December 2011. Accessed April 3, 2018.

6. Lee AJ, Boro MS, Knapp KK, Meier JL, Korman NE. Clinical and economic outcomes of pharmacist recommendations in a Veterans Affairs medical center. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002;59(21):2070–2077.

7. Ourth H, Groppi J, Morreale AP, Quicci-Roberts K. Clinical pharmacist prescribing activities in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(18):1406-1415.

8. US Department of Veteran Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Healthcare Talent Management Workforce Management & Consulting Office. VHA workforce planning report 2015.https://www.vacareers.va.gov/assets/common/print/2015_VHA_Workforce_Succession_Strategic_Plan.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed April 3, 2018.

9. Davis RG, Hepfinger CA, Sauer KA, Wilhardt MS. Retrospective evaluation of medication appropriateness and clinical pharmacist drug therapy recommendations for home-based primary care veterans. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;5(1):40-47.

10. Beales JL, Edes T. Veteran’s Affairs home based primary care. Clin Geriatr Med. 2009;25(1):149-154.

11. Cooper DF, Granadillo OR, Stacey CM. Home-based primary care: the care of the veteran at home. Home Healthc Nurse. 2007;25(5):315-322.

12. Pradel FG, Palumbo FB, Flowers L, et al. White paper: value of specialty certification in pharmacy. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2004;44(5):612-620.

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Handbook 1108.11(1). Clinical pharmacy services. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=3120. Updated June 29, 2017. Accessed April 3, 2018

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA Directive 1141.01: home-based primary care special population aligned care team program. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=5417. Updated September 20, 2017. Accessed April 3, 2018.

2. Brahmbhatt M, Palla K, Kossifologos A, Mitchell D, Lee T. Appropriateness of medication prescribing using the STOPP/START criteria in veterans receiving home-based primary care. Consult Pharm. 2013;28(6):361-369.

3. Hanlon JT, Weinberger M, Samsa GP, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a clinical pharmacist intervention to improve inappropriate prescribing in elderly outpatients with polypharmacy. Am J Med. 1996;100(4):428-437.

4. Rose AJ, McCullough MB, Carter BL, Rudin RS. The clinical pharmacy specialist: part of the solution. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(4):375–377.

5. Giberson S, Yoder S, Lee MP. Improving patient and health system outcomes through advanced pharmacy practice: a report to the U.S. Surgeon General 2011. https://www.accp.com/docs/positions/misc/Improving_Patient_and_Health_System_Outcomes.pdf. Published December 2011. Accessed April 3, 2018.

6. Lee AJ, Boro MS, Knapp KK, Meier JL, Korman NE. Clinical and economic outcomes of pharmacist recommendations in a Veterans Affairs medical center. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002;59(21):2070–2077.

7. Ourth H, Groppi J, Morreale AP, Quicci-Roberts K. Clinical pharmacist prescribing activities in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(18):1406-1415.

8. US Department of Veteran Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Healthcare Talent Management Workforce Management & Consulting Office. VHA workforce planning report 2015.https://www.vacareers.va.gov/assets/common/print/2015_VHA_Workforce_Succession_Strategic_Plan.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed April 3, 2018.

9. Davis RG, Hepfinger CA, Sauer KA, Wilhardt MS. Retrospective evaluation of medication appropriateness and clinical pharmacist drug therapy recommendations for home-based primary care veterans. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;5(1):40-47.

10. Beales JL, Edes T. Veteran’s Affairs home based primary care. Clin Geriatr Med. 2009;25(1):149-154.

11. Cooper DF, Granadillo OR, Stacey CM. Home-based primary care: the care of the veteran at home. Home Healthc Nurse. 2007;25(5):315-322.

12. Pradel FG, Palumbo FB, Flowers L, et al. White paper: value of specialty certification in pharmacy. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2004;44(5):612-620.

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Handbook 1108.11(1). Clinical pharmacy services. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=3120. Updated June 29, 2017. Accessed April 3, 2018