User login

CHICAGO – Five years of statin therapy for primary prevention provided an impressive lifetime benefit expressed as reduced risks of a range of cardiovascular disease outcomes in a 20-year follow-up of the landmark WOSCOPS trial.

“There is a rather remarkable persistence of benefit in terms of risk reduction over a long period. You’ve changed the natural history of the disease in some way by lowering LDL,” Dr. Chris J. Packard said in presenting the 20-year WOSCOPS (West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study) follow-up at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The primary prevention study randomized 6,595 middle-aged Scotsmen with an average baseline LDL cholesterol of 190 mg/dL to 4 years of pravastatin at 40 mg/day or placebo. This was one of the early large statin trials, and publication of the 5-year outcomes showing a 31% reduction in the relative risk of cardiovascular death or MI (N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;333:1301-8) caused a great stir.

At that point, WOSCOPS leaders advised study participants’ primary care physicians to seriously consider putting their patients on long-term statin therapy. However, only an identically low 31% of subjects in each of the two study arms did so.

Because the Scottish national health care system effectively captures all utilization of medical services, Dr. Packard and coinvestigators were able to analyze 20-year outcomes in the former study participants. No other major statin trial has come close in terms of length of reported follow-up.

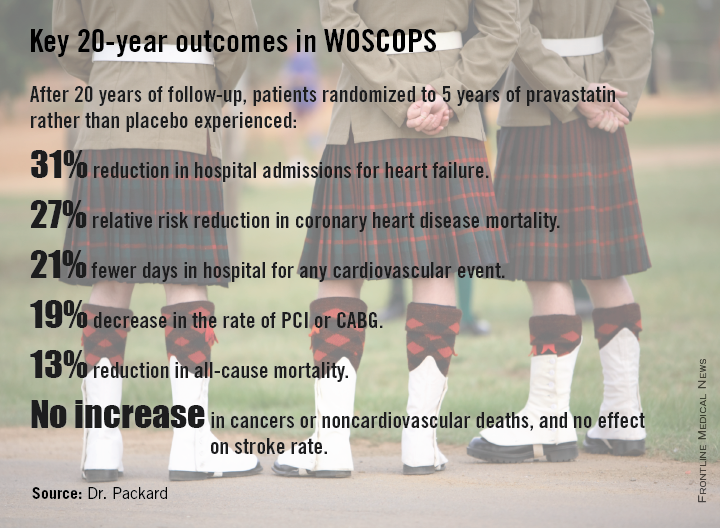

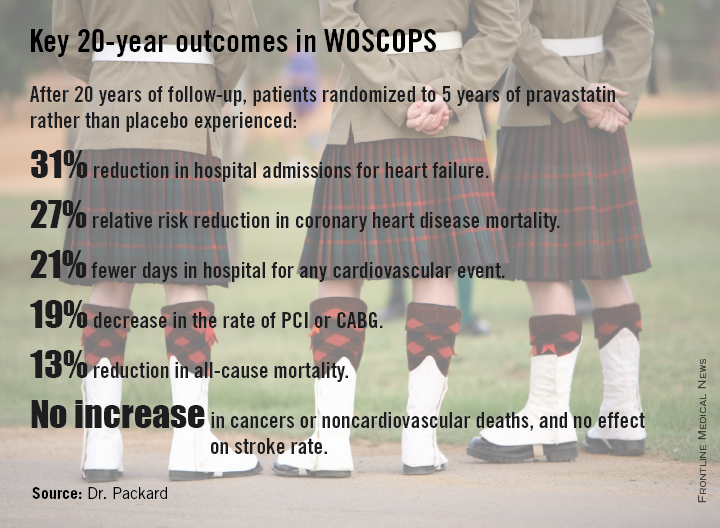

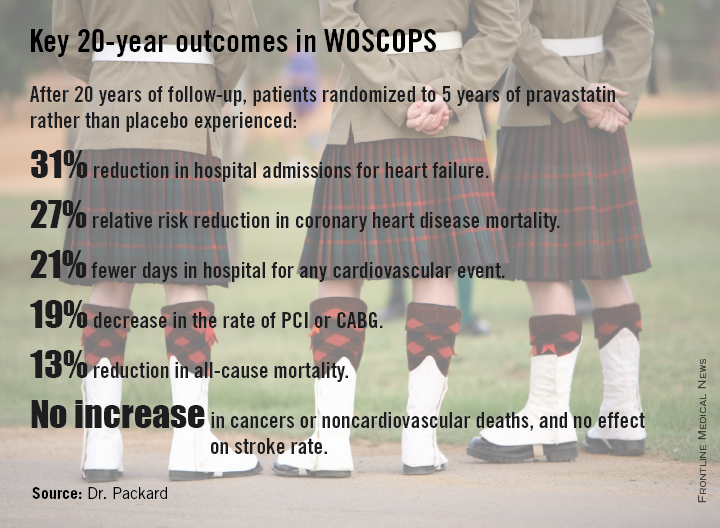

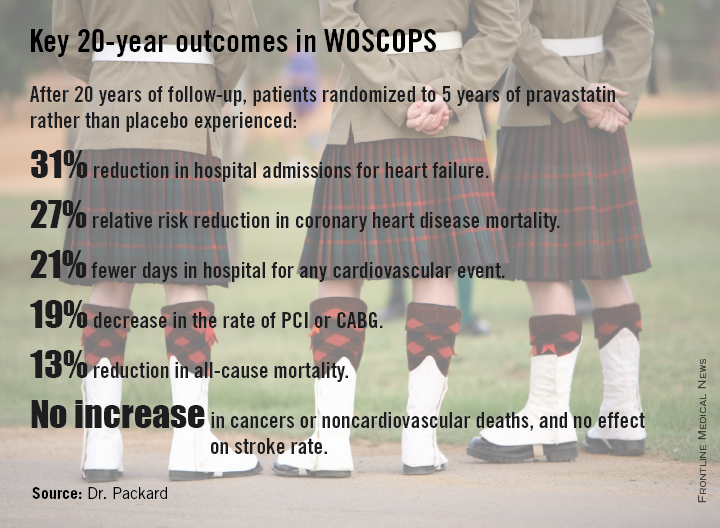

At 20 years, with the only treatment difference between the two original study arms being that the pravastatin group had been on statin therapy for an additional 5 years, the 20-year coronary heart disease mortality rate in the original statin group was reduced by 27%, compared with the original controls. All-cause mortality was reduced by 13%. And numerous other benefits were noted at 20 years with 5 years of statin therapy.

Indeed, patients treated with pravastatin for 5 years during the trial gained an average of 5 extra years free of nonfatal MI or cardiovascular death at the 20-year mark, he said.

“The average age of the men was 55 years during the trial and 20 years on they’re now 75 years old. This covers the entire period of premature cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. We would argue that this is a good picture of the lifetime benefit, which is different from lifetime risk. This is real events happening to real people, not predictions,” observed Dr. Packard, professor of cardiovascular and medical sciences at the University of Glasgow, Scotland.

The group given pravastatin for 5 years collectively spent 24,038 days in the hospital for any cardiovascular event, compared with 30,342 days for controls.

Particularly noteworthy was the divergence in the risk of heart failure, with 96 cases being diagnosed during 20 years in patients who received 5 years of pravastatin, compared with 128 in controls.

“Heart failure was our biggest surprise,” he said. “We got no result for heart failure at all at 5 years; these were middle-aged men with just high cholesterol, so we didn’t see much in the way of incident heart failure. But extrapolating 20 years, there is a 31% risk reduction in the incidence of hospitalization for heart failure in the statin-treated group, compared to the placebo-treated group. This is a remarkable finding.”

For WOSCOPS participants who got a 20% drop in LDL during 5 years of pravastatin from a baseline of 190 mg/dL, as was typical, the number of patients who needed to be treated (NNT) for 5 years to prevent one cardiovascular hospital admission over a 20-year period was six. Moreover, for every 10 patients on statin therapy for 5 years, an average of 19 hospital days were avoided over the course of 20 years. For patients with a baseline LDL of 120 mg/dL, the NNT was 10, and 12 hospital days were saved over a 20-year period for every 10 patients treated for 5 years.

“This is a real savings to the health service and the health care providers to offset the cost of drugs,” Dr. Packard continued.

He urged physicians to look beyond the initial reports of primary outcomes of the statin clinical trials and take a long-term view.

“If you take a lifetime approach to benefit so you’re looking not only at the first event, but the second event, the third, at heart failure, and at death, you can see tremendous benefits, whereas usually we only focus on the first event. And that’s not the full cost evaluation that you need to do,” according to Dr. Packard.

The overall incidence of cancer during 20 years of follow-up was 24.8% in the initial placebo arm and 24.5% in the pravastatin group, with no differences between the two groups in any type of cancer. Nor did the original pravastatin group show any increase in noncardiovascular mortality.

“This is a very important study – the first study to show a legacy effect, with reduced mortality and a gain of 5 event-free years over 20 years attributable to a 5-year treatment allocation,” said discussant Harvey White of Auckland (New Zealand) City Hospital.

This legacy effect, he added, can be viewed as an ongoing carryover effect related to statin-induced slowing and/or stabilization of existing coronary artery plaque. The mechanism is unknown, Dr. White said, but the key to why the legacy effect was seen in WOSCOPS despite the use of pravastatin – a less potent statin – but not to date in other statin trials may lie in the fact that WOSCOPS was a primary prevention study and its participants had the youngest mean age of all the major statin trials.

“Their plaques may not have been calcified yet and therefore were more able to be modified and stabilized. If you treat very early you might get a bigger effect,” said to Dr. White.

Undercutting that argument, however, was the WOSCOPS finding that the long-term benefits of 5 years of pravastatin were independent of age at treatment, Dr. Packard said.

He believes based upon other studies that statins’ coronary disease prevention benefits are expressed within the first 12 months after starting therapy.

“It suggests that whatever is happening to the pathobiology of atherosclerosis happens within a year, and somehow a statis is introduced into plaque. That’s my guess, that an unstable plaque is reduced to a stable one. People then form a new trajectory going forward and they never catch up. We should think of atherosclerosis as a rate effect rather than something that either happens or doesn’t happen. It’s a rate of happening,” Dr. Packard asserted.

Asked why in the aftermath of the strongly positive 5-year results of WOSCOPS only 31% of patients in each treatment arm were on long-term statin therapy, he replied that 20 years ago in Scotland there really was no push for primary prevention.

“The 4S trial had come out the year before [Lancet 1994;344:1383-9] and placed the focus on secondary prevention. Statins were relatively expensive and everybody was putting their money into secondary prevention. Our health care system, which is socialized, had not put any emphasis at all on primary prevention. We were actually amazed that even 31% got treated,” the physician explained.

Dr. Packard reported serving as a consultant to Merck, Roche, and AstraZeneca.

CHICAGO – Five years of statin therapy for primary prevention provided an impressive lifetime benefit expressed as reduced risks of a range of cardiovascular disease outcomes in a 20-year follow-up of the landmark WOSCOPS trial.

“There is a rather remarkable persistence of benefit in terms of risk reduction over a long period. You’ve changed the natural history of the disease in some way by lowering LDL,” Dr. Chris J. Packard said in presenting the 20-year WOSCOPS (West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study) follow-up at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The primary prevention study randomized 6,595 middle-aged Scotsmen with an average baseline LDL cholesterol of 190 mg/dL to 4 years of pravastatin at 40 mg/day or placebo. This was one of the early large statin trials, and publication of the 5-year outcomes showing a 31% reduction in the relative risk of cardiovascular death or MI (N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;333:1301-8) caused a great stir.

At that point, WOSCOPS leaders advised study participants’ primary care physicians to seriously consider putting their patients on long-term statin therapy. However, only an identically low 31% of subjects in each of the two study arms did so.

Because the Scottish national health care system effectively captures all utilization of medical services, Dr. Packard and coinvestigators were able to analyze 20-year outcomes in the former study participants. No other major statin trial has come close in terms of length of reported follow-up.

At 20 years, with the only treatment difference between the two original study arms being that the pravastatin group had been on statin therapy for an additional 5 years, the 20-year coronary heart disease mortality rate in the original statin group was reduced by 27%, compared with the original controls. All-cause mortality was reduced by 13%. And numerous other benefits were noted at 20 years with 5 years of statin therapy.

Indeed, patients treated with pravastatin for 5 years during the trial gained an average of 5 extra years free of nonfatal MI or cardiovascular death at the 20-year mark, he said.

“The average age of the men was 55 years during the trial and 20 years on they’re now 75 years old. This covers the entire period of premature cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. We would argue that this is a good picture of the lifetime benefit, which is different from lifetime risk. This is real events happening to real people, not predictions,” observed Dr. Packard, professor of cardiovascular and medical sciences at the University of Glasgow, Scotland.

The group given pravastatin for 5 years collectively spent 24,038 days in the hospital for any cardiovascular event, compared with 30,342 days for controls.

Particularly noteworthy was the divergence in the risk of heart failure, with 96 cases being diagnosed during 20 years in patients who received 5 years of pravastatin, compared with 128 in controls.

“Heart failure was our biggest surprise,” he said. “We got no result for heart failure at all at 5 years; these were middle-aged men with just high cholesterol, so we didn’t see much in the way of incident heart failure. But extrapolating 20 years, there is a 31% risk reduction in the incidence of hospitalization for heart failure in the statin-treated group, compared to the placebo-treated group. This is a remarkable finding.”

For WOSCOPS participants who got a 20% drop in LDL during 5 years of pravastatin from a baseline of 190 mg/dL, as was typical, the number of patients who needed to be treated (NNT) for 5 years to prevent one cardiovascular hospital admission over a 20-year period was six. Moreover, for every 10 patients on statin therapy for 5 years, an average of 19 hospital days were avoided over the course of 20 years. For patients with a baseline LDL of 120 mg/dL, the NNT was 10, and 12 hospital days were saved over a 20-year period for every 10 patients treated for 5 years.

“This is a real savings to the health service and the health care providers to offset the cost of drugs,” Dr. Packard continued.

He urged physicians to look beyond the initial reports of primary outcomes of the statin clinical trials and take a long-term view.

“If you take a lifetime approach to benefit so you’re looking not only at the first event, but the second event, the third, at heart failure, and at death, you can see tremendous benefits, whereas usually we only focus on the first event. And that’s not the full cost evaluation that you need to do,” according to Dr. Packard.

The overall incidence of cancer during 20 years of follow-up was 24.8% in the initial placebo arm and 24.5% in the pravastatin group, with no differences between the two groups in any type of cancer. Nor did the original pravastatin group show any increase in noncardiovascular mortality.

“This is a very important study – the first study to show a legacy effect, with reduced mortality and a gain of 5 event-free years over 20 years attributable to a 5-year treatment allocation,” said discussant Harvey White of Auckland (New Zealand) City Hospital.

This legacy effect, he added, can be viewed as an ongoing carryover effect related to statin-induced slowing and/or stabilization of existing coronary artery plaque. The mechanism is unknown, Dr. White said, but the key to why the legacy effect was seen in WOSCOPS despite the use of pravastatin – a less potent statin – but not to date in other statin trials may lie in the fact that WOSCOPS was a primary prevention study and its participants had the youngest mean age of all the major statin trials.

“Their plaques may not have been calcified yet and therefore were more able to be modified and stabilized. If you treat very early you might get a bigger effect,” said to Dr. White.

Undercutting that argument, however, was the WOSCOPS finding that the long-term benefits of 5 years of pravastatin were independent of age at treatment, Dr. Packard said.

He believes based upon other studies that statins’ coronary disease prevention benefits are expressed within the first 12 months after starting therapy.

“It suggests that whatever is happening to the pathobiology of atherosclerosis happens within a year, and somehow a statis is introduced into plaque. That’s my guess, that an unstable plaque is reduced to a stable one. People then form a new trajectory going forward and they never catch up. We should think of atherosclerosis as a rate effect rather than something that either happens or doesn’t happen. It’s a rate of happening,” Dr. Packard asserted.

Asked why in the aftermath of the strongly positive 5-year results of WOSCOPS only 31% of patients in each treatment arm were on long-term statin therapy, he replied that 20 years ago in Scotland there really was no push for primary prevention.

“The 4S trial had come out the year before [Lancet 1994;344:1383-9] and placed the focus on secondary prevention. Statins were relatively expensive and everybody was putting their money into secondary prevention. Our health care system, which is socialized, had not put any emphasis at all on primary prevention. We were actually amazed that even 31% got treated,” the physician explained.

Dr. Packard reported serving as a consultant to Merck, Roche, and AstraZeneca.

CHICAGO – Five years of statin therapy for primary prevention provided an impressive lifetime benefit expressed as reduced risks of a range of cardiovascular disease outcomes in a 20-year follow-up of the landmark WOSCOPS trial.

“There is a rather remarkable persistence of benefit in terms of risk reduction over a long period. You’ve changed the natural history of the disease in some way by lowering LDL,” Dr. Chris J. Packard said in presenting the 20-year WOSCOPS (West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study) follow-up at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The primary prevention study randomized 6,595 middle-aged Scotsmen with an average baseline LDL cholesterol of 190 mg/dL to 4 years of pravastatin at 40 mg/day or placebo. This was one of the early large statin trials, and publication of the 5-year outcomes showing a 31% reduction in the relative risk of cardiovascular death or MI (N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;333:1301-8) caused a great stir.

At that point, WOSCOPS leaders advised study participants’ primary care physicians to seriously consider putting their patients on long-term statin therapy. However, only an identically low 31% of subjects in each of the two study arms did so.

Because the Scottish national health care system effectively captures all utilization of medical services, Dr. Packard and coinvestigators were able to analyze 20-year outcomes in the former study participants. No other major statin trial has come close in terms of length of reported follow-up.

At 20 years, with the only treatment difference between the two original study arms being that the pravastatin group had been on statin therapy for an additional 5 years, the 20-year coronary heart disease mortality rate in the original statin group was reduced by 27%, compared with the original controls. All-cause mortality was reduced by 13%. And numerous other benefits were noted at 20 years with 5 years of statin therapy.

Indeed, patients treated with pravastatin for 5 years during the trial gained an average of 5 extra years free of nonfatal MI or cardiovascular death at the 20-year mark, he said.

“The average age of the men was 55 years during the trial and 20 years on they’re now 75 years old. This covers the entire period of premature cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. We would argue that this is a good picture of the lifetime benefit, which is different from lifetime risk. This is real events happening to real people, not predictions,” observed Dr. Packard, professor of cardiovascular and medical sciences at the University of Glasgow, Scotland.

The group given pravastatin for 5 years collectively spent 24,038 days in the hospital for any cardiovascular event, compared with 30,342 days for controls.

Particularly noteworthy was the divergence in the risk of heart failure, with 96 cases being diagnosed during 20 years in patients who received 5 years of pravastatin, compared with 128 in controls.

“Heart failure was our biggest surprise,” he said. “We got no result for heart failure at all at 5 years; these were middle-aged men with just high cholesterol, so we didn’t see much in the way of incident heart failure. But extrapolating 20 years, there is a 31% risk reduction in the incidence of hospitalization for heart failure in the statin-treated group, compared to the placebo-treated group. This is a remarkable finding.”

For WOSCOPS participants who got a 20% drop in LDL during 5 years of pravastatin from a baseline of 190 mg/dL, as was typical, the number of patients who needed to be treated (NNT) for 5 years to prevent one cardiovascular hospital admission over a 20-year period was six. Moreover, for every 10 patients on statin therapy for 5 years, an average of 19 hospital days were avoided over the course of 20 years. For patients with a baseline LDL of 120 mg/dL, the NNT was 10, and 12 hospital days were saved over a 20-year period for every 10 patients treated for 5 years.

“This is a real savings to the health service and the health care providers to offset the cost of drugs,” Dr. Packard continued.

He urged physicians to look beyond the initial reports of primary outcomes of the statin clinical trials and take a long-term view.

“If you take a lifetime approach to benefit so you’re looking not only at the first event, but the second event, the third, at heart failure, and at death, you can see tremendous benefits, whereas usually we only focus on the first event. And that’s not the full cost evaluation that you need to do,” according to Dr. Packard.

The overall incidence of cancer during 20 years of follow-up was 24.8% in the initial placebo arm and 24.5% in the pravastatin group, with no differences between the two groups in any type of cancer. Nor did the original pravastatin group show any increase in noncardiovascular mortality.

“This is a very important study – the first study to show a legacy effect, with reduced mortality and a gain of 5 event-free years over 20 years attributable to a 5-year treatment allocation,” said discussant Harvey White of Auckland (New Zealand) City Hospital.

This legacy effect, he added, can be viewed as an ongoing carryover effect related to statin-induced slowing and/or stabilization of existing coronary artery plaque. The mechanism is unknown, Dr. White said, but the key to why the legacy effect was seen in WOSCOPS despite the use of pravastatin – a less potent statin – but not to date in other statin trials may lie in the fact that WOSCOPS was a primary prevention study and its participants had the youngest mean age of all the major statin trials.

“Their plaques may not have been calcified yet and therefore were more able to be modified and stabilized. If you treat very early you might get a bigger effect,” said to Dr. White.

Undercutting that argument, however, was the WOSCOPS finding that the long-term benefits of 5 years of pravastatin were independent of age at treatment, Dr. Packard said.

He believes based upon other studies that statins’ coronary disease prevention benefits are expressed within the first 12 months after starting therapy.

“It suggests that whatever is happening to the pathobiology of atherosclerosis happens within a year, and somehow a statis is introduced into plaque. That’s my guess, that an unstable plaque is reduced to a stable one. People then form a new trajectory going forward and they never catch up. We should think of atherosclerosis as a rate effect rather than something that either happens or doesn’t happen. It’s a rate of happening,” Dr. Packard asserted.

Asked why in the aftermath of the strongly positive 5-year results of WOSCOPS only 31% of patients in each treatment arm were on long-term statin therapy, he replied that 20 years ago in Scotland there really was no push for primary prevention.

“The 4S trial had come out the year before [Lancet 1994;344:1383-9] and placed the focus on secondary prevention. Statins were relatively expensive and everybody was putting their money into secondary prevention. Our health care system, which is socialized, had not put any emphasis at all on primary prevention. We were actually amazed that even 31% got treated,” the physician explained.

Dr. Packard reported serving as a consultant to Merck, Roche, and AstraZeneca.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Five years of statin therapy during midlife for primary prevention may reset the clock for atherosclerotic progression, providing persistently lower cardiovascular event rates 20 years later.

Major finding: The number of patients who needed to be treated with pravastatin for 5 years to prevent one cardiovascular hospitalization over a 20-year period was six.

Data source: A 20-year follow-up of the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study, in which 6,595 middle-aged men with high cholesterol were randomized to 5 years of pravastatin or placebo.

Disclosures: WOSCOPS was sponsored by Bristol-Myers Squibb. The presenter reported serving as a consultant to Merck, Roche, and AstraZeneca.