User login

HCV Hub

AbbVie

acid

addicted

addiction

adolescent

adult sites

Advocacy

advocacy

agitated states

AJO, postsurgical analgesic, knee, replacement, surgery

alcohol

amphetamine

androgen

antibody

apple cider vinegar

assistance

Assistance

association

at home

attorney

audit

ayurvedic

baby

ban

baricitinib

bed bugs

best

bible

bisexual

black

bleach

blog

bulimia nervosa

buy

cannabis

certificate

certification

certified

cervical cancer, concurrent chemoradiotherapy, intravoxel incoherent motion magnetic resonance imaging, MRI, IVIM, diffusion-weighted MRI, DWI

charlie sheen

cheap

cheapest

child

childhood

childlike

children

chronic fatigue syndrome

Cladribine Tablets

cocaine

cock

combination therapies, synergistic antitumor efficacy, pertuzumab, trastuzumab, ipilimumab, nivolumab, palbociclib, letrozole, lapatinib, docetaxel, trametinib, dabrafenib, carflzomib, lenalidomide

contagious

Cortical Lesions

cream

creams

crime

criminal

cure

dangerous

dangers

dasabuvir

Dasabuvir

dead

deadly

death

dementia

dependence

dependent

depression

dermatillomania

die

diet

direct-acting antivirals

Disability

Discount

discount

dog

drink

drug abuse

drug-induced

dying

eastern medicine

eat

ect

eczema

electroconvulsive therapy

electromagnetic therapy

electrotherapy

epa

epilepsy

erectile dysfunction

explosive disorder

fake

Fake-ovir

fatal

fatalities

fatality

fibromyalgia

financial

Financial

fish oil

food

foods

foundation

free

Gabriel Pardo

gaston

general hospital

genetic

geriatric

Giancarlo Comi

gilead

Gilead

glaucoma

Glenn S. Williams

Glenn Williams

Gloria Dalla Costa

gonorrhea

Greedy

greedy

guns

hallucinations

harvoni

Harvoni

herbal

herbs

heroin

herpes

Hidradenitis Suppurativa,

holistic

home

home remedies

home remedy

homeopathic

homeopathy

hydrocortisone

ice

image

images

job

kid

kids

kill

killer

laser

lawsuit

lawyer

ledipasvir

Ledipasvir

lesbian

lesions

lights

liver

lupus

marijuana

melancholic

memory loss

menopausal

mental retardation

military

milk

moisturizers

monoamine oxidase inhibitor drugs

MRI

MS

murder

national

natural

natural cure

natural cures

natural medications

natural medicine

natural medicines

natural remedies

natural remedy

natural treatment

natural treatments

naturally

Needy

needy

Neurology Reviews

neuropathic

nightclub massacre

nightclub shooting

nude

nudity

nutraceuticals

OASIS

oasis

off label

ombitasvir

Ombitasvir

ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir with dasabuvir

orlando shooting

overactive thyroid gland

overdose

overdosed

Paolo Preziosa

paritaprevir

Paritaprevir

pediatric

pedophile

photo

photos

picture

post partum

postnatal

pregnancy

pregnant

prenatal

prepartum

prison

program

Program

Protest

protest

psychedelics

pulse nightclub

puppy

purchase

purchasing

rape

recall

recreational drug

Rehabilitation

Retinal Measurements

retrograde ejaculation

risperdal

ritonavir

Ritonavir

ritonavir with dasabuvir

robin williams

sales

sasquatch

schizophrenia

seizure

seizures

sex

sexual

sexy

shock treatment

silver

sleep disorders

smoking

sociopath

sofosbuvir

Sofosbuvir

sovaldi

ssri

store

sue

suicidal

suicide

supplements

support

Support

Support Path

teen

teenage

teenagers

Telerehabilitation

testosterone

Th17

Th17:FoxP3+Treg cell ratio

Th22

toxic

toxin

tragedy

treatment resistant

V Pak

vagina

velpatasvir

Viekira Pa

Viekira Pak

viekira pak

violence

virgin

vitamin

VPak

weight loss

withdrawal

wrinkles

xxx

young adult

young adults

zoloft

financial

sofosbuvir

ritonavir with dasabuvir

discount

support path

program

ritonavir

greedy

ledipasvir

assistance

viekira pak

vpak

advocacy

needy

protest

abbvie

paritaprevir

ombitasvir

direct-acting antivirals

dasabuvir

gilead

fake-ovir

support

v pak

oasis

harvoni

DDW: VIDEO: What we don’t know in the management of liver disease and coagulopathy

WASHINGTON – Your patient has cirrhosis, platelets 60,000 mm3, an INR of 2.0, serum creatinine of 1.2 mg/dL, and requires an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with sphincterotomy.

What do you do next?

Management of a patient such as this is challenging, but not just because of the long-perceived risk for bleeding, Dr. Patrick S. Kamath of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., said during a clinical symposium at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Several other factors must be considered, including the clotting risk in patients with liver disease and the fact that procedure-related bleeding risk cannot be adequately determined preprocedure. Transfusions also carry their own dangers in this patient population and should be approached with caution, he said.

To hear more from this world-renowned liver expert, check out our interview as we sat down with Dr. Kamath at this year’s DDW.

Dr. Kamath reported no relevant financial conflicts.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @pwendl

WASHINGTON – Your patient has cirrhosis, platelets 60,000 mm3, an INR of 2.0, serum creatinine of 1.2 mg/dL, and requires an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with sphincterotomy.

What do you do next?

Management of a patient such as this is challenging, but not just because of the long-perceived risk for bleeding, Dr. Patrick S. Kamath of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., said during a clinical symposium at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Several other factors must be considered, including the clotting risk in patients with liver disease and the fact that procedure-related bleeding risk cannot be adequately determined preprocedure. Transfusions also carry their own dangers in this patient population and should be approached with caution, he said.

To hear more from this world-renowned liver expert, check out our interview as we sat down with Dr. Kamath at this year’s DDW.

Dr. Kamath reported no relevant financial conflicts.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @pwendl

WASHINGTON – Your patient has cirrhosis, platelets 60,000 mm3, an INR of 2.0, serum creatinine of 1.2 mg/dL, and requires an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with sphincterotomy.

What do you do next?

Management of a patient such as this is challenging, but not just because of the long-perceived risk for bleeding, Dr. Patrick S. Kamath of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., said during a clinical symposium at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Several other factors must be considered, including the clotting risk in patients with liver disease and the fact that procedure-related bleeding risk cannot be adequately determined preprocedure. Transfusions also carry their own dangers in this patient population and should be approached with caution, he said.

To hear more from this world-renowned liver expert, check out our interview as we sat down with Dr. Kamath at this year’s DDW.

Dr. Kamath reported no relevant financial conflicts.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @pwendl

AT DDW 2015

DDW: Barrett’s ‘indefinite for dysplasia’ may be cancer harbinger

WASHINGTON – A diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus “indefinite for dysplasia” doesn’t mean that the patient is home free; it may, in fact, be an indicator of increased risk for progression to high-grade dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma, investigators suggest.

Among 87 patients who had follow-up endoscopies and biopsies within a year of a diagnosis of Barrett’s indefinite for dysplasia (IND), 7 had progression of disease, including 5 who developed high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma, and 2 who developed low-grade disease.

Of these seven patients, four had disease progression with 6 months of a diagnosis of Barrett’s IND, Dr, Michelle Ma reported at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

“Indefinite for dysplasia is an important diagnostic category that is associated with an increased risk for prevalent dysplasia, particularly within the first 6 months after diagnosis. After 12 months, the risk for progressing to advanced neoplasia is low, and similar to other studies,” said Dr. Ma of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Although there is fairly strong evidence to guide the management of patients with low-grade and high-grade dysplasia, it’s less clear whether Barrett’s IND is risk marker for progression. Dr. Ma said, citing a somewhat fuzzy definition of the term: “Epithelial abnormalities insufficient to diagnose dysplasia, or epithelial abnormalities unclear due to inflammation or sampling.”

Uncertainty about the natural history of IND is reflected in practice guidelines, which either don’t address it, call for repeat endoscopy in 6 months, or call for an expert gastrointestinal pathology review with repeat endoscopy to clarify dysplasia status if the evidence is of low quality, Dr. Ma said.

To determine the rate of, and risk factors for, neoplastic progression of IND, the authors took a retrospective look at patients in their center’s pathology database and Barrett’s esophagus register with a histopathologic diagnosis of IND from 2000 through 2014. They excluded patients with frank dysplasia or carcinoma on diagnosis, and those who did not have follow-up endoscopies.

The investigatoes factored demographic variables into their analysis, including age, gender, body-mass index, smoking history, use of proton-pump inhibitors (PPI), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and family history of Barrett’s or esophageal adenocarcinoma. They also considered endoscopic/pathologic characteristics such as hiatal hernia size, Barrett’s segment length, muscosal nodularity, and multifocal IND.

A total of 106 patients with IND were eligible for the analysis, 87 of whom had follow-up endoscopy and biopsy within a year of diagnosis. As noted before, 7 of these patients had prevalent disease, with prevalence rates of 2.3% for low-grade dysplasia, 4.6% for high-grade dysplasia, and 1.1% for esophageal adenocarcinoma.

To determine the incidence of dysplasia, the authors first excluded the 7 patients with prevealent dysplasia and 33 patients who did not have a surveillance endoscopy in the first year following a diagnosis of IND, leaving 66 patients for analysis. Of this group, 3 developed incident dysplasia or adenocarcinoma, yielding an incidence of 4.5% over a median of 32 months of follow-up.

An analysis of risk factors for prevalent dysplasia showed that none of the variables was significant, although Barrett’s segment length approached statistical significance. Looking at risk factors for incident dysplasia, both smoking status (P = .0207) and segment length (P = .0253) were significant predictors.

A pathologist who was not involved in the study pointed out that a diagnosis of IND can mean many things to many people.

“Indefinite for dysplasia is really not an entity, it’s about 5,000 things that we choose to put into that category. It’s a horribly non-reproducible diagnosis,” commented Dr. Henry D. Appelman, a professor of anatomic pathology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, during a aquestion-and-answer period.

He questioned whether the diagnoses of IND were subject to review at her center.

Dr. Ma noted that Barrett’s specimens at her institution are routinely reviewed by pathologists specializing in Barrett’s, who will also review slides of patients referred to the center from other institutions.

The study was internally funded. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

WASHINGTON – A diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus “indefinite for dysplasia” doesn’t mean that the patient is home free; it may, in fact, be an indicator of increased risk for progression to high-grade dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma, investigators suggest.

Among 87 patients who had follow-up endoscopies and biopsies within a year of a diagnosis of Barrett’s indefinite for dysplasia (IND), 7 had progression of disease, including 5 who developed high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma, and 2 who developed low-grade disease.

Of these seven patients, four had disease progression with 6 months of a diagnosis of Barrett’s IND, Dr, Michelle Ma reported at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

“Indefinite for dysplasia is an important diagnostic category that is associated with an increased risk for prevalent dysplasia, particularly within the first 6 months after diagnosis. After 12 months, the risk for progressing to advanced neoplasia is low, and similar to other studies,” said Dr. Ma of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Although there is fairly strong evidence to guide the management of patients with low-grade and high-grade dysplasia, it’s less clear whether Barrett’s IND is risk marker for progression. Dr. Ma said, citing a somewhat fuzzy definition of the term: “Epithelial abnormalities insufficient to diagnose dysplasia, or epithelial abnormalities unclear due to inflammation or sampling.”

Uncertainty about the natural history of IND is reflected in practice guidelines, which either don’t address it, call for repeat endoscopy in 6 months, or call for an expert gastrointestinal pathology review with repeat endoscopy to clarify dysplasia status if the evidence is of low quality, Dr. Ma said.

To determine the rate of, and risk factors for, neoplastic progression of IND, the authors took a retrospective look at patients in their center’s pathology database and Barrett’s esophagus register with a histopathologic diagnosis of IND from 2000 through 2014. They excluded patients with frank dysplasia or carcinoma on diagnosis, and those who did not have follow-up endoscopies.

The investigatoes factored demographic variables into their analysis, including age, gender, body-mass index, smoking history, use of proton-pump inhibitors (PPI), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and family history of Barrett’s or esophageal adenocarcinoma. They also considered endoscopic/pathologic characteristics such as hiatal hernia size, Barrett’s segment length, muscosal nodularity, and multifocal IND.

A total of 106 patients with IND were eligible for the analysis, 87 of whom had follow-up endoscopy and biopsy within a year of diagnosis. As noted before, 7 of these patients had prevalent disease, with prevalence rates of 2.3% for low-grade dysplasia, 4.6% for high-grade dysplasia, and 1.1% for esophageal adenocarcinoma.

To determine the incidence of dysplasia, the authors first excluded the 7 patients with prevealent dysplasia and 33 patients who did not have a surveillance endoscopy in the first year following a diagnosis of IND, leaving 66 patients for analysis. Of this group, 3 developed incident dysplasia or adenocarcinoma, yielding an incidence of 4.5% over a median of 32 months of follow-up.

An analysis of risk factors for prevalent dysplasia showed that none of the variables was significant, although Barrett’s segment length approached statistical significance. Looking at risk factors for incident dysplasia, both smoking status (P = .0207) and segment length (P = .0253) were significant predictors.

A pathologist who was not involved in the study pointed out that a diagnosis of IND can mean many things to many people.

“Indefinite for dysplasia is really not an entity, it’s about 5,000 things that we choose to put into that category. It’s a horribly non-reproducible diagnosis,” commented Dr. Henry D. Appelman, a professor of anatomic pathology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, during a aquestion-and-answer period.

He questioned whether the diagnoses of IND were subject to review at her center.

Dr. Ma noted that Barrett’s specimens at her institution are routinely reviewed by pathologists specializing in Barrett’s, who will also review slides of patients referred to the center from other institutions.

The study was internally funded. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

WASHINGTON – A diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus “indefinite for dysplasia” doesn’t mean that the patient is home free; it may, in fact, be an indicator of increased risk for progression to high-grade dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma, investigators suggest.

Among 87 patients who had follow-up endoscopies and biopsies within a year of a diagnosis of Barrett’s indefinite for dysplasia (IND), 7 had progression of disease, including 5 who developed high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma, and 2 who developed low-grade disease.

Of these seven patients, four had disease progression with 6 months of a diagnosis of Barrett’s IND, Dr, Michelle Ma reported at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

“Indefinite for dysplasia is an important diagnostic category that is associated with an increased risk for prevalent dysplasia, particularly within the first 6 months after diagnosis. After 12 months, the risk for progressing to advanced neoplasia is low, and similar to other studies,” said Dr. Ma of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Although there is fairly strong evidence to guide the management of patients with low-grade and high-grade dysplasia, it’s less clear whether Barrett’s IND is risk marker for progression. Dr. Ma said, citing a somewhat fuzzy definition of the term: “Epithelial abnormalities insufficient to diagnose dysplasia, or epithelial abnormalities unclear due to inflammation or sampling.”

Uncertainty about the natural history of IND is reflected in practice guidelines, which either don’t address it, call for repeat endoscopy in 6 months, or call for an expert gastrointestinal pathology review with repeat endoscopy to clarify dysplasia status if the evidence is of low quality, Dr. Ma said.

To determine the rate of, and risk factors for, neoplastic progression of IND, the authors took a retrospective look at patients in their center’s pathology database and Barrett’s esophagus register with a histopathologic diagnosis of IND from 2000 through 2014. They excluded patients with frank dysplasia or carcinoma on diagnosis, and those who did not have follow-up endoscopies.

The investigatoes factored demographic variables into their analysis, including age, gender, body-mass index, smoking history, use of proton-pump inhibitors (PPI), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and family history of Barrett’s or esophageal adenocarcinoma. They also considered endoscopic/pathologic characteristics such as hiatal hernia size, Barrett’s segment length, muscosal nodularity, and multifocal IND.

A total of 106 patients with IND were eligible for the analysis, 87 of whom had follow-up endoscopy and biopsy within a year of diagnosis. As noted before, 7 of these patients had prevalent disease, with prevalence rates of 2.3% for low-grade dysplasia, 4.6% for high-grade dysplasia, and 1.1% for esophageal adenocarcinoma.

To determine the incidence of dysplasia, the authors first excluded the 7 patients with prevealent dysplasia and 33 patients who did not have a surveillance endoscopy in the first year following a diagnosis of IND, leaving 66 patients for analysis. Of this group, 3 developed incident dysplasia or adenocarcinoma, yielding an incidence of 4.5% over a median of 32 months of follow-up.

An analysis of risk factors for prevalent dysplasia showed that none of the variables was significant, although Barrett’s segment length approached statistical significance. Looking at risk factors for incident dysplasia, both smoking status (P = .0207) and segment length (P = .0253) were significant predictors.

A pathologist who was not involved in the study pointed out that a diagnosis of IND can mean many things to many people.

“Indefinite for dysplasia is really not an entity, it’s about 5,000 things that we choose to put into that category. It’s a horribly non-reproducible diagnosis,” commented Dr. Henry D. Appelman, a professor of anatomic pathology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, during a aquestion-and-answer period.

He questioned whether the diagnoses of IND were subject to review at her center.

Dr. Ma noted that Barrett’s specimens at her institution are routinely reviewed by pathologists specializing in Barrett’s, who will also review slides of patients referred to the center from other institutions.

The study was internally funded. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

AT DDW 2015

Key clinical point: Barrett’s esophagus indefinite for dysplasia may progress to dysplasia or adenocarcinoma within a year of diagnosis.

Major finding: Seven of 87 patients with a diagnosis of Barrett’s indefinite for dysplasia (IND) had disease progression within 1 year.

Data source: Retrospective case series of 87 patients who had follow-up endoscopies and biopsies within a year of a diagnosis of Barrett’s IND.

Disclosures: The study was internally funded. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

DDW: Significant worker productivity gains with newer hepatitis C drugs

Achieving a cure in hepatitis C infection could result in significant economic gains, with a study estimating that the beneficial effects in terms of improved worker productivity could total around $3.23 billion per year for the United States alone.

Researchers used data on work productivity and activity scores from patients enrolled in clinical trials of the all-oral sofosbuvir and lepidasvir combo to estimate the impact of achieving sustained virologic response at 12 weeks (SVR-12) on workers’ productivity.

They calculated an average work productivity loss of $4,954 for each employed patient with chronic hepatitis C infection per year in the United States and $1,129 per year for the five European Union countries included in the mix.

“These new all-oral combinations such as lepidasvir and sofosbuvir have cure rates between 95% and 99% with minimum side effects, [so] treating patients with these combinations results in improved work productivity, improved quality of life, and patient-reported outcomes that can translate into economic benefit,” Dr. Zobair M. Younossi of the Inova Fairfax Medical Campus, Falls Church, Va., said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

No conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Achieving a cure in hepatitis C infection could result in significant economic gains, with a study estimating that the beneficial effects in terms of improved worker productivity could total around $3.23 billion per year for the United States alone.

Researchers used data on work productivity and activity scores from patients enrolled in clinical trials of the all-oral sofosbuvir and lepidasvir combo to estimate the impact of achieving sustained virologic response at 12 weeks (SVR-12) on workers’ productivity.

They calculated an average work productivity loss of $4,954 for each employed patient with chronic hepatitis C infection per year in the United States and $1,129 per year for the five European Union countries included in the mix.

“These new all-oral combinations such as lepidasvir and sofosbuvir have cure rates between 95% and 99% with minimum side effects, [so] treating patients with these combinations results in improved work productivity, improved quality of life, and patient-reported outcomes that can translate into economic benefit,” Dr. Zobair M. Younossi of the Inova Fairfax Medical Campus, Falls Church, Va., said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

No conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Achieving a cure in hepatitis C infection could result in significant economic gains, with a study estimating that the beneficial effects in terms of improved worker productivity could total around $3.23 billion per year for the United States alone.

Researchers used data on work productivity and activity scores from patients enrolled in clinical trials of the all-oral sofosbuvir and lepidasvir combo to estimate the impact of achieving sustained virologic response at 12 weeks (SVR-12) on workers’ productivity.

They calculated an average work productivity loss of $4,954 for each employed patient with chronic hepatitis C infection per year in the United States and $1,129 per year for the five European Union countries included in the mix.

“These new all-oral combinations such as lepidasvir and sofosbuvir have cure rates between 95% and 99% with minimum side effects, [so] treating patients with these combinations results in improved work productivity, improved quality of life, and patient-reported outcomes that can translate into economic benefit,” Dr. Zobair M. Younossi of the Inova Fairfax Medical Campus, Falls Church, Va., said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

No conflicts of interest were disclosed.

FROM DDW 2015

Key clinical point: Achieving a cure in hepatitis C infection could result in significant economic gains from improved worker productivity.

Major finding: The beneficial effects in terms of improved worker productivity could total around $3.23 billion per year for the United States alone.

Data source: Economic model using data from hepatitis C clinical trials in the United States and Europe.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were disclosed.

DDW: Biologic agents improve Crohn’s disease picture

WASHINGTON – The course of Crohn’s disease has changed for the better since the introduction of biological therapies and other treatments in the late 1990s.

“In an era of novel treatment options and strategies for Crohn’s disease, we are seeing that the hospitalization and surgery rates have declined, but progression to a complicated phenotype is unfortunately still common nowadays,” said Dr. Steven Jeuring from Maastricht (the Netherlands) University Medical Center.

A community-based study comparing outcomes for patients with Crohn’s Disease (CD) before and after the introduction of infliximab (Remicade) in the Netherlands in 1999 showed the risk of hospitalization was 55% lower for patients treated after 1999, and the risk for hospitalization during the course of the disease was 35% lower. Similarly, the risk for requiring surgery was 77% lower for patients treated in the modern era, and the risk for surgery at any time in the disease course was 54% lower, Dr. Jeuring said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

The prevalence of a complicated CD phenotype, marked by the presence of bowel stricturing and/or penetration, was also 48% lower at the time of diagnosis among patients treated within the last two decades, but the rate of progression from an inflammatory to complicated phenotype remained unchanged from the pre-biologics era, Dr. Jeuring said.

He and his colleagues conducted a retrospective study with a population-based cohort of adults with incident inflammatory bowel disease diagnosed from 1991 through 1998 (342 patients) and from 1999 through 2011 (820 patients). The cohort represented 93% of all patients in the IBD registry of the South Limburg region of the Netherlands.

They found that the distribution of disease phenotypes was significantly different between the two time periods, with 45% of patients having complicated disease in the pre-biologics era, compared with 37% during the biologics era, translating into a 23% reduction over time. However, in both cohorts, a fairly large proportion of patients already had complicated disease at the time of diagnosis, Dr. Jeuring noted.

When the investigators looked at the risk of developing stricturing or penetrating disease during 8 years of follow-up, however, they found that there was no difference between the groups, with 30% of patients in the earlier cohort having disease progression, compared with 28% of patients in the later cohort, translating into a non-significant hazard ratio (HR) of 0.95.

Dr. Jeuring said that this finding was “very, very disappointing.”

More encouraging, however was the finding that hospitalization rates in the modern era were significantly lower than in the pre-biologics period. For example, the likelihood of being hospitalized at any time during 8 years of follow-up was 72% in the earlier cohort, compared with 52% in the later cohort.

The HR for being hospitalized at the time of diagnosis among the later vs. earlier cohorts was 0.45, and was statistically significant. Similarly, the HR for being hospitalized at any time over 8 years was 0.65 for patients in the modern era (also significant, with a 95% confidence interval that did not cross 1).

Even more dramatically, more modern therapies were associated with a significant reduction in the risk of being rehospitalized, with a significant HR of 0.29.

The risk for surgical resection either at diagnosis or during the 8-year follow-up period was 52% among patients diagnosed and started on treatment in the 1990s, compared with 25% for patients treated in the new millennium. For the latter cohort, the HRs for surgery at the time of diagnosis and for surgery during follow-up were 0.23 and 0.46, respectively. Both were statistically significant.

The lower risk for surgery for patients in the modern era is primarily driven by decreased risk for surgery for inflammatory disease, Dr, Jeuring said.

The study was supported by Maastricht University Medical Center. Dr. Jeuring reported having no conflicts of interest.

WASHINGTON – The course of Crohn’s disease has changed for the better since the introduction of biological therapies and other treatments in the late 1990s.

“In an era of novel treatment options and strategies for Crohn’s disease, we are seeing that the hospitalization and surgery rates have declined, but progression to a complicated phenotype is unfortunately still common nowadays,” said Dr. Steven Jeuring from Maastricht (the Netherlands) University Medical Center.

A community-based study comparing outcomes for patients with Crohn’s Disease (CD) before and after the introduction of infliximab (Remicade) in the Netherlands in 1999 showed the risk of hospitalization was 55% lower for patients treated after 1999, and the risk for hospitalization during the course of the disease was 35% lower. Similarly, the risk for requiring surgery was 77% lower for patients treated in the modern era, and the risk for surgery at any time in the disease course was 54% lower, Dr. Jeuring said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

The prevalence of a complicated CD phenotype, marked by the presence of bowel stricturing and/or penetration, was also 48% lower at the time of diagnosis among patients treated within the last two decades, but the rate of progression from an inflammatory to complicated phenotype remained unchanged from the pre-biologics era, Dr. Jeuring said.

He and his colleagues conducted a retrospective study with a population-based cohort of adults with incident inflammatory bowel disease diagnosed from 1991 through 1998 (342 patients) and from 1999 through 2011 (820 patients). The cohort represented 93% of all patients in the IBD registry of the South Limburg region of the Netherlands.

They found that the distribution of disease phenotypes was significantly different between the two time periods, with 45% of patients having complicated disease in the pre-biologics era, compared with 37% during the biologics era, translating into a 23% reduction over time. However, in both cohorts, a fairly large proportion of patients already had complicated disease at the time of diagnosis, Dr. Jeuring noted.

When the investigators looked at the risk of developing stricturing or penetrating disease during 8 years of follow-up, however, they found that there was no difference between the groups, with 30% of patients in the earlier cohort having disease progression, compared with 28% of patients in the later cohort, translating into a non-significant hazard ratio (HR) of 0.95.

Dr. Jeuring said that this finding was “very, very disappointing.”

More encouraging, however was the finding that hospitalization rates in the modern era were significantly lower than in the pre-biologics period. For example, the likelihood of being hospitalized at any time during 8 years of follow-up was 72% in the earlier cohort, compared with 52% in the later cohort.

The HR for being hospitalized at the time of diagnosis among the later vs. earlier cohorts was 0.45, and was statistically significant. Similarly, the HR for being hospitalized at any time over 8 years was 0.65 for patients in the modern era (also significant, with a 95% confidence interval that did not cross 1).

Even more dramatically, more modern therapies were associated with a significant reduction in the risk of being rehospitalized, with a significant HR of 0.29.

The risk for surgical resection either at diagnosis or during the 8-year follow-up period was 52% among patients diagnosed and started on treatment in the 1990s, compared with 25% for patients treated in the new millennium. For the latter cohort, the HRs for surgery at the time of diagnosis and for surgery during follow-up were 0.23 and 0.46, respectively. Both were statistically significant.

The lower risk for surgery for patients in the modern era is primarily driven by decreased risk for surgery for inflammatory disease, Dr, Jeuring said.

The study was supported by Maastricht University Medical Center. Dr. Jeuring reported having no conflicts of interest.

WASHINGTON – The course of Crohn’s disease has changed for the better since the introduction of biological therapies and other treatments in the late 1990s.

“In an era of novel treatment options and strategies for Crohn’s disease, we are seeing that the hospitalization and surgery rates have declined, but progression to a complicated phenotype is unfortunately still common nowadays,” said Dr. Steven Jeuring from Maastricht (the Netherlands) University Medical Center.

A community-based study comparing outcomes for patients with Crohn’s Disease (CD) before and after the introduction of infliximab (Remicade) in the Netherlands in 1999 showed the risk of hospitalization was 55% lower for patients treated after 1999, and the risk for hospitalization during the course of the disease was 35% lower. Similarly, the risk for requiring surgery was 77% lower for patients treated in the modern era, and the risk for surgery at any time in the disease course was 54% lower, Dr. Jeuring said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

The prevalence of a complicated CD phenotype, marked by the presence of bowel stricturing and/or penetration, was also 48% lower at the time of diagnosis among patients treated within the last two decades, but the rate of progression from an inflammatory to complicated phenotype remained unchanged from the pre-biologics era, Dr. Jeuring said.

He and his colleagues conducted a retrospective study with a population-based cohort of adults with incident inflammatory bowel disease diagnosed from 1991 through 1998 (342 patients) and from 1999 through 2011 (820 patients). The cohort represented 93% of all patients in the IBD registry of the South Limburg region of the Netherlands.

They found that the distribution of disease phenotypes was significantly different between the two time periods, with 45% of patients having complicated disease in the pre-biologics era, compared with 37% during the biologics era, translating into a 23% reduction over time. However, in both cohorts, a fairly large proportion of patients already had complicated disease at the time of diagnosis, Dr. Jeuring noted.

When the investigators looked at the risk of developing stricturing or penetrating disease during 8 years of follow-up, however, they found that there was no difference between the groups, with 30% of patients in the earlier cohort having disease progression, compared with 28% of patients in the later cohort, translating into a non-significant hazard ratio (HR) of 0.95.

Dr. Jeuring said that this finding was “very, very disappointing.”

More encouraging, however was the finding that hospitalization rates in the modern era were significantly lower than in the pre-biologics period. For example, the likelihood of being hospitalized at any time during 8 years of follow-up was 72% in the earlier cohort, compared with 52% in the later cohort.

The HR for being hospitalized at the time of diagnosis among the later vs. earlier cohorts was 0.45, and was statistically significant. Similarly, the HR for being hospitalized at any time over 8 years was 0.65 for patients in the modern era (also significant, with a 95% confidence interval that did not cross 1).

Even more dramatically, more modern therapies were associated with a significant reduction in the risk of being rehospitalized, with a significant HR of 0.29.

The risk for surgical resection either at diagnosis or during the 8-year follow-up period was 52% among patients diagnosed and started on treatment in the 1990s, compared with 25% for patients treated in the new millennium. For the latter cohort, the HRs for surgery at the time of diagnosis and for surgery during follow-up were 0.23 and 0.46, respectively. Both were statistically significant.

The lower risk for surgery for patients in the modern era is primarily driven by decreased risk for surgery for inflammatory disease, Dr, Jeuring said.

The study was supported by Maastricht University Medical Center. Dr. Jeuring reported having no conflicts of interest.

AT DDW 2015

Key clinical point: The advent of biologic agents has improved hospitalization and surgery rates for patients with Crohn’s disease.

Major finding: The risk of hospitalization for patients treated after 1999 or for hospitalization during the course of the disease was 55% and 35% lower, respectively. and the risks for requiring surgery in the modern era or at any time in the disease course was 77% and 54% lower.

Data source: Population-based cohort study of 1,162 patients with inflammatory bowel disease in the South Limburg region of the Netherlands.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Maastricht University Medical Center. Dr. Jeuring reported having no conflicts of interest.

DDW: Statin use associated with significantly lower risk of new-onset IBD

WASHINGTON – A prescription for a statin was associated with about a 40% lower risk of new-onset inflammatory bowel disease in a study that evaluated data from a large U.S. health claims database over a 5-year period, Dr. Ryan Ungaro said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

The protective effect was seen with different statins and was not associated with the intensity of statin treatment, said Dr. Ungaro, a gastroenterologist at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

He and his associates conducted a case-control study by using a national medical claims and pharmacy database, identifying 87,579 patients aged 18 and older with an ICD-9 code for a diagnosis of ulcerative colitis (UC) or Crohn’s disease (CD) from January 2008 through December 2012, and 189,526 controls (each case was matched with up to 10 controls, matched for age, gender, race, and state of residence). The median age of cases and controls was about 51 years, and about 41% were male. About 47% were diagnosed with CD, and about 44% were diagnosed with UC. A smaller group of patients who were new-onset cases were included who had at least 1 year with no IBD-related diagnostic code or prescription before the index diagnosis.

Statin use was associated with about a 40% reduced risk of new-onset IBD (odds ratio, 0.59), with similar trends for UC and CD, Dr. Ungaro reported. Separately, the risks of new-onset CD (OR, 0.55) and new-onset UC (OR, 0.62) associated with having a prescription for a statin were also significantly lower.

This association was maintained “regardless of which specific statin a patient was exposed to,” he noted. There was no significant difference in risk of IBD based on the intensity of statin treatment, according to American Heart Association guidelines for low-, moderate-, and high-intensity treatment.

Another finding was that the strongest protective effect was seen in older people, with an OR of 0.55 among those aged 60 years and older. There was no significant effect among those aged 18-30 years, but there were a limited number of statin prescriptions for younger patients, Dr. Ungaro noted.

Limitations of the study include the retrospective design, the inability to directly validate cases, and the reliance on a prescription as a surrogate for the patient actually taking the medication, he said.

Based on the results, “we think that future studies should confirm this protective effect, as well as continue to investigate statins in established IBD,” he concluded.

He referred to recent research demonstrating that statins have immunomodulatory effects “and may actually potentially be beneficial in established IBD.” In addition, a few clinical studies that have looked at the effects of statins in people with established IBD have found that statins are associated with a decreased need for oral steroids and may be associated with improvements in clinical indices and disease and inflammatory markers. Basic science studies indicate that statins are associated with amelioration of disease in mouse models of IBD, may decrease mediators of inflammation, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and may also suppress antigen presentation and T-cell proliferation, he noted.

Dr. Ungaro and his coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – A prescription for a statin was associated with about a 40% lower risk of new-onset inflammatory bowel disease in a study that evaluated data from a large U.S. health claims database over a 5-year period, Dr. Ryan Ungaro said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

The protective effect was seen with different statins and was not associated with the intensity of statin treatment, said Dr. Ungaro, a gastroenterologist at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

He and his associates conducted a case-control study by using a national medical claims and pharmacy database, identifying 87,579 patients aged 18 and older with an ICD-9 code for a diagnosis of ulcerative colitis (UC) or Crohn’s disease (CD) from January 2008 through December 2012, and 189,526 controls (each case was matched with up to 10 controls, matched for age, gender, race, and state of residence). The median age of cases and controls was about 51 years, and about 41% were male. About 47% were diagnosed with CD, and about 44% were diagnosed with UC. A smaller group of patients who were new-onset cases were included who had at least 1 year with no IBD-related diagnostic code or prescription before the index diagnosis.

Statin use was associated with about a 40% reduced risk of new-onset IBD (odds ratio, 0.59), with similar trends for UC and CD, Dr. Ungaro reported. Separately, the risks of new-onset CD (OR, 0.55) and new-onset UC (OR, 0.62) associated with having a prescription for a statin were also significantly lower.

This association was maintained “regardless of which specific statin a patient was exposed to,” he noted. There was no significant difference in risk of IBD based on the intensity of statin treatment, according to American Heart Association guidelines for low-, moderate-, and high-intensity treatment.

Another finding was that the strongest protective effect was seen in older people, with an OR of 0.55 among those aged 60 years and older. There was no significant effect among those aged 18-30 years, but there were a limited number of statin prescriptions for younger patients, Dr. Ungaro noted.

Limitations of the study include the retrospective design, the inability to directly validate cases, and the reliance on a prescription as a surrogate for the patient actually taking the medication, he said.

Based on the results, “we think that future studies should confirm this protective effect, as well as continue to investigate statins in established IBD,” he concluded.

He referred to recent research demonstrating that statins have immunomodulatory effects “and may actually potentially be beneficial in established IBD.” In addition, a few clinical studies that have looked at the effects of statins in people with established IBD have found that statins are associated with a decreased need for oral steroids and may be associated with improvements in clinical indices and disease and inflammatory markers. Basic science studies indicate that statins are associated with amelioration of disease in mouse models of IBD, may decrease mediators of inflammation, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and may also suppress antigen presentation and T-cell proliferation, he noted.

Dr. Ungaro and his coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – A prescription for a statin was associated with about a 40% lower risk of new-onset inflammatory bowel disease in a study that evaluated data from a large U.S. health claims database over a 5-year period, Dr. Ryan Ungaro said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

The protective effect was seen with different statins and was not associated with the intensity of statin treatment, said Dr. Ungaro, a gastroenterologist at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

He and his associates conducted a case-control study by using a national medical claims and pharmacy database, identifying 87,579 patients aged 18 and older with an ICD-9 code for a diagnosis of ulcerative colitis (UC) or Crohn’s disease (CD) from January 2008 through December 2012, and 189,526 controls (each case was matched with up to 10 controls, matched for age, gender, race, and state of residence). The median age of cases and controls was about 51 years, and about 41% were male. About 47% were diagnosed with CD, and about 44% were diagnosed with UC. A smaller group of patients who were new-onset cases were included who had at least 1 year with no IBD-related diagnostic code or prescription before the index diagnosis.

Statin use was associated with about a 40% reduced risk of new-onset IBD (odds ratio, 0.59), with similar trends for UC and CD, Dr. Ungaro reported. Separately, the risks of new-onset CD (OR, 0.55) and new-onset UC (OR, 0.62) associated with having a prescription for a statin were also significantly lower.

This association was maintained “regardless of which specific statin a patient was exposed to,” he noted. There was no significant difference in risk of IBD based on the intensity of statin treatment, according to American Heart Association guidelines for low-, moderate-, and high-intensity treatment.

Another finding was that the strongest protective effect was seen in older people, with an OR of 0.55 among those aged 60 years and older. There was no significant effect among those aged 18-30 years, but there were a limited number of statin prescriptions for younger patients, Dr. Ungaro noted.

Limitations of the study include the retrospective design, the inability to directly validate cases, and the reliance on a prescription as a surrogate for the patient actually taking the medication, he said.

Based on the results, “we think that future studies should confirm this protective effect, as well as continue to investigate statins in established IBD,” he concluded.

He referred to recent research demonstrating that statins have immunomodulatory effects “and may actually potentially be beneficial in established IBD.” In addition, a few clinical studies that have looked at the effects of statins in people with established IBD have found that statins are associated with a decreased need for oral steroids and may be associated with improvements in clinical indices and disease and inflammatory markers. Basic science studies indicate that statins are associated with amelioration of disease in mouse models of IBD, may decrease mediators of inflammation, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and may also suppress antigen presentation and T-cell proliferation, he noted.

Dr. Ungaro and his coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT DDW 2015

Key clinical point: A reduced risk of new onset inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) may be another benefit of statin therapy.

Major finding: A prescription for a statin was associated with about a 40% lower risk of new-onset IBD, an effect that was seen with different statins and only in older people, in a large case-control study.

Data source: The retrospective study evaluated the risk of new-onset Crohn’s disease (CD) and new-onset ulcerative colitis (UC), in about 87,500 patients with a diagnostic code for UC or CD, and controls using a US national medical claims and pharmacy database from 2008-2012.

Disclosures: Dr. Ungaro and his coauthors had no relevant disclosures.

Shortening all-oral HCV therapy feasible

VIENNA – All-oral HCV therapy with grazoprevir and elbasvir plus sofosbuvir achieved high, sustained virologic response (SVR) rates at 12 weeks after only 6-8 weeks of therapy in a proof-of-concept phase II study.

“HCV therapy is evolving toward a once-daily, short duration, pan-genotypic, highly effective and safe regimen,” said Dr. Fred Poordad of the Texas Liver Institute, San Antonio, who reported the findings of the C-SWIFT study at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

“The aim of this study was to combine three highly potent direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) grazoprevir, elbasvir and sofosbuvir, each with a different mechanisms of action, to see if we could shorten therapy in two of the most difficult-to-cure populations, genotype 1 [GT1] and genotype 3 [GT3] with and without cirrhosis,” he said.

For inclusion, patients had to be treatment naive and older than 18 years of age. Cirrhosis had to be present, assessed either by liver biopsy or via noninvasive testing, and the minimum hemoglobin at enrollment needed to be 9.5 g/dL. Patients also had to be negative for HIV and the hepatitis B virus, and have liver enzyme below 350 IU/L.

Treatment consisted of a fixed-dose, once daily combination of grazoprevir 100 mg and elbasvir 50 mg plus additional sofosbuvir 400 mg, once daily. The duration of therapy depended on genotype and the presence or absence of cirrhosis.

A total of 102 patients with GT1 were enrolled, of whom 61 had no cirrhosis and were treated with the three-drug combination for a total of 4 (n = 31) or 6 (n = 30) weeks. Patients with GT1 and cirrhosis were treated with the regimen for 6 (n = 20) or 8 (n = 21) weeks.

There were 41 GT3 patients enrolled, of whom 29 had no cirrhosis and were treated for 8 (n = 15) or 12 weeks (n = 14). The 12 GT3 cirrhotic patients received 12 weeks of the regimen.

Dr. Poordad noted that the majority of patients studied were male, in their mid-50s, and of white ethnicity. The majority of the GT1 patients were subtype 1a.

Results showed that 33% of GT1 patients without cirrhosis achieved SVR12 with 4 weeks of treatment, and 87% with 6 weeks therapy. SVR12 was achieved in 80% and 94% of patients with GT1 and cirrhosis after 6 and 8 weeks of therapy, respectively.

No patient experienced breakthrough. Twenty of the noncirrhotic GT1 patients treated for 4 weeks relapsed, as did four who were treated for 6 weeks. Four relapses also occurred in cirrhotic GT1 patients treated for 6 weeks and one patient with cirrhosis relapsed after 8 weeks of treatment.

Dr. Poordad noted that patients relapsed most commonly if they had either wild-type virus or resistant-associated variants (RAV) already present at baseline.

In the GT3 arms, SVR12 was achieved by 93% and 100% of the noncirrhotic patients treated for 8 weeks and 12 weeks, respectively, and by 91% of those with cirrhosis who had 12 weeks of treatment. One patient discontinued treatment early for a reason other than virologic failure and two patients relapsed – one patient without cirrhosis in the 8-week treatment group and one in the cirrhotic group.

“All of the patients became ‘target not detected’ at the end of treatment,” Dr. Poordad observed. “The patient in the 8-week arm relapsed somewhere between SVR4 and SVR12, while the cirrhotic patient relapsed in the first 4 weeks of follow-up” he said.

Of the two GT3 patients with biologic failures, one did not have baseline RAVS and also had wild-type virus at relapse. The other patient had RAVs at baseline in NS3 and in NS5A at relapse.

There were “very few adverse events,” Dr. Poordad said, noting that there were no significant declines in hemoglobin or elevations in liver enzymes or bilirubin. The most common adverse events were headache, fatigue, and nausea, all of which occurred in fairly low numbers.

“This novel regimen of grazoprevir/elbasvir with sofosbuvir was able to shorten therapy duration to 8 weeks or less among patients who were cirrhotic and noncirrhotic with genotype 1,” Dr. Poordad said in summary.

Even GT3 patients were able to achieve high SVR12 rates with 8-12 weeks of therapy, including those who had cirrhosis.

“The concept of shortening therapy, even in the cirrhotic patients, has been demonstrated by this study,” he concluded.

He noted that retreatment of virologic failures was ongoing.

The study was sponsored by Merck & Co. Dr. Poordad has received grant/research support from Merck & Co. and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

VIENNA – All-oral HCV therapy with grazoprevir and elbasvir plus sofosbuvir achieved high, sustained virologic response (SVR) rates at 12 weeks after only 6-8 weeks of therapy in a proof-of-concept phase II study.

“HCV therapy is evolving toward a once-daily, short duration, pan-genotypic, highly effective and safe regimen,” said Dr. Fred Poordad of the Texas Liver Institute, San Antonio, who reported the findings of the C-SWIFT study at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

“The aim of this study was to combine three highly potent direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) grazoprevir, elbasvir and sofosbuvir, each with a different mechanisms of action, to see if we could shorten therapy in two of the most difficult-to-cure populations, genotype 1 [GT1] and genotype 3 [GT3] with and without cirrhosis,” he said.

For inclusion, patients had to be treatment naive and older than 18 years of age. Cirrhosis had to be present, assessed either by liver biopsy or via noninvasive testing, and the minimum hemoglobin at enrollment needed to be 9.5 g/dL. Patients also had to be negative for HIV and the hepatitis B virus, and have liver enzyme below 350 IU/L.

Treatment consisted of a fixed-dose, once daily combination of grazoprevir 100 mg and elbasvir 50 mg plus additional sofosbuvir 400 mg, once daily. The duration of therapy depended on genotype and the presence or absence of cirrhosis.

A total of 102 patients with GT1 were enrolled, of whom 61 had no cirrhosis and were treated with the three-drug combination for a total of 4 (n = 31) or 6 (n = 30) weeks. Patients with GT1 and cirrhosis were treated with the regimen for 6 (n = 20) or 8 (n = 21) weeks.

There were 41 GT3 patients enrolled, of whom 29 had no cirrhosis and were treated for 8 (n = 15) or 12 weeks (n = 14). The 12 GT3 cirrhotic patients received 12 weeks of the regimen.

Dr. Poordad noted that the majority of patients studied were male, in their mid-50s, and of white ethnicity. The majority of the GT1 patients were subtype 1a.

Results showed that 33% of GT1 patients without cirrhosis achieved SVR12 with 4 weeks of treatment, and 87% with 6 weeks therapy. SVR12 was achieved in 80% and 94% of patients with GT1 and cirrhosis after 6 and 8 weeks of therapy, respectively.

No patient experienced breakthrough. Twenty of the noncirrhotic GT1 patients treated for 4 weeks relapsed, as did four who were treated for 6 weeks. Four relapses also occurred in cirrhotic GT1 patients treated for 6 weeks and one patient with cirrhosis relapsed after 8 weeks of treatment.

Dr. Poordad noted that patients relapsed most commonly if they had either wild-type virus or resistant-associated variants (RAV) already present at baseline.

In the GT3 arms, SVR12 was achieved by 93% and 100% of the noncirrhotic patients treated for 8 weeks and 12 weeks, respectively, and by 91% of those with cirrhosis who had 12 weeks of treatment. One patient discontinued treatment early for a reason other than virologic failure and two patients relapsed – one patient without cirrhosis in the 8-week treatment group and one in the cirrhotic group.

“All of the patients became ‘target not detected’ at the end of treatment,” Dr. Poordad observed. “The patient in the 8-week arm relapsed somewhere between SVR4 and SVR12, while the cirrhotic patient relapsed in the first 4 weeks of follow-up” he said.

Of the two GT3 patients with biologic failures, one did not have baseline RAVS and also had wild-type virus at relapse. The other patient had RAVs at baseline in NS3 and in NS5A at relapse.

There were “very few adverse events,” Dr. Poordad said, noting that there were no significant declines in hemoglobin or elevations in liver enzymes or bilirubin. The most common adverse events were headache, fatigue, and nausea, all of which occurred in fairly low numbers.

“This novel regimen of grazoprevir/elbasvir with sofosbuvir was able to shorten therapy duration to 8 weeks or less among patients who were cirrhotic and noncirrhotic with genotype 1,” Dr. Poordad said in summary.

Even GT3 patients were able to achieve high SVR12 rates with 8-12 weeks of therapy, including those who had cirrhosis.

“The concept of shortening therapy, even in the cirrhotic patients, has been demonstrated by this study,” he concluded.

He noted that retreatment of virologic failures was ongoing.

The study was sponsored by Merck & Co. Dr. Poordad has received grant/research support from Merck & Co. and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

VIENNA – All-oral HCV therapy with grazoprevir and elbasvir plus sofosbuvir achieved high, sustained virologic response (SVR) rates at 12 weeks after only 6-8 weeks of therapy in a proof-of-concept phase II study.

“HCV therapy is evolving toward a once-daily, short duration, pan-genotypic, highly effective and safe regimen,” said Dr. Fred Poordad of the Texas Liver Institute, San Antonio, who reported the findings of the C-SWIFT study at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

“The aim of this study was to combine three highly potent direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) grazoprevir, elbasvir and sofosbuvir, each with a different mechanisms of action, to see if we could shorten therapy in two of the most difficult-to-cure populations, genotype 1 [GT1] and genotype 3 [GT3] with and without cirrhosis,” he said.

For inclusion, patients had to be treatment naive and older than 18 years of age. Cirrhosis had to be present, assessed either by liver biopsy or via noninvasive testing, and the minimum hemoglobin at enrollment needed to be 9.5 g/dL. Patients also had to be negative for HIV and the hepatitis B virus, and have liver enzyme below 350 IU/L.

Treatment consisted of a fixed-dose, once daily combination of grazoprevir 100 mg and elbasvir 50 mg plus additional sofosbuvir 400 mg, once daily. The duration of therapy depended on genotype and the presence or absence of cirrhosis.

A total of 102 patients with GT1 were enrolled, of whom 61 had no cirrhosis and were treated with the three-drug combination for a total of 4 (n = 31) or 6 (n = 30) weeks. Patients with GT1 and cirrhosis were treated with the regimen for 6 (n = 20) or 8 (n = 21) weeks.

There were 41 GT3 patients enrolled, of whom 29 had no cirrhosis and were treated for 8 (n = 15) or 12 weeks (n = 14). The 12 GT3 cirrhotic patients received 12 weeks of the regimen.

Dr. Poordad noted that the majority of patients studied were male, in their mid-50s, and of white ethnicity. The majority of the GT1 patients were subtype 1a.

Results showed that 33% of GT1 patients without cirrhosis achieved SVR12 with 4 weeks of treatment, and 87% with 6 weeks therapy. SVR12 was achieved in 80% and 94% of patients with GT1 and cirrhosis after 6 and 8 weeks of therapy, respectively.

No patient experienced breakthrough. Twenty of the noncirrhotic GT1 patients treated for 4 weeks relapsed, as did four who were treated for 6 weeks. Four relapses also occurred in cirrhotic GT1 patients treated for 6 weeks and one patient with cirrhosis relapsed after 8 weeks of treatment.

Dr. Poordad noted that patients relapsed most commonly if they had either wild-type virus or resistant-associated variants (RAV) already present at baseline.

In the GT3 arms, SVR12 was achieved by 93% and 100% of the noncirrhotic patients treated for 8 weeks and 12 weeks, respectively, and by 91% of those with cirrhosis who had 12 weeks of treatment. One patient discontinued treatment early for a reason other than virologic failure and two patients relapsed – one patient without cirrhosis in the 8-week treatment group and one in the cirrhotic group.

“All of the patients became ‘target not detected’ at the end of treatment,” Dr. Poordad observed. “The patient in the 8-week arm relapsed somewhere between SVR4 and SVR12, while the cirrhotic patient relapsed in the first 4 weeks of follow-up” he said.

Of the two GT3 patients with biologic failures, one did not have baseline RAVS and also had wild-type virus at relapse. The other patient had RAVs at baseline in NS3 and in NS5A at relapse.

There were “very few adverse events,” Dr. Poordad said, noting that there were no significant declines in hemoglobin or elevations in liver enzymes or bilirubin. The most common adverse events were headache, fatigue, and nausea, all of which occurred in fairly low numbers.

“This novel regimen of grazoprevir/elbasvir with sofosbuvir was able to shorten therapy duration to 8 weeks or less among patients who were cirrhotic and noncirrhotic with genotype 1,” Dr. Poordad said in summary.

Even GT3 patients were able to achieve high SVR12 rates with 8-12 weeks of therapy, including those who had cirrhosis.

“The concept of shortening therapy, even in the cirrhotic patients, has been demonstrated by this study,” he concluded.

He noted that retreatment of virologic failures was ongoing.

The study was sponsored by Merck & Co. Dr. Poordad has received grant/research support from Merck & Co. and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

AT THE INTERNATIONAL LIVER CONGRESS 2015

Key clinical point: Shortening HCV therapy to 6-8 weeks is possible, even in cirrhotic patients.

Major finding: SVR12 was achieved by 87%-94% of GT1 patients treated for 6-8 weeks and by 91%-100% of GT3 patients treated for 8-12 weeks.

Data source: Phase II, open-label study of 143 treatment-naive patients with HCV genotype 1 or 3 with or without cirrhosis treated with a fixed-dose combination of grazoprevir (100 mg) and elbasvir (50 mg) plus sofosbuvir (400 mg) for 4, 6, 8, or 12 weeks.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Merck & Co. Dr. Poordad has received grant/research support from Merck & Co. and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

ILC: Direct antivirals safely clear HCV despite ESRD

VIENNA – A 12-week, fixed-dose regimen safely and effectively eradicated chronic hepatitis C infection from the first 10 patients with advanced chronic kidney disease in a multicenter U.S. series.

The regimen of three direct antiviral agents is already on the U.S. market. So far, 20 HCV patients with advanced chronic kidney disease have been treated and there have been no cases of virologic failure. All 10 patients who have been followed for at least 4 weeks after completing treatment sustained their virologic response, Dr. Paul J. Pockros said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

The series has exclusively enrolled patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. The seven enrolled patients infected with genotype 1b HCV received the three direct antiviral agents only, the combination of ombitasvir, paritaprevir boosted with ritonavir, and dasabuvir, which together are marketed as Viekira Pak. The 13 patients with a genotype 1a infection received treatment with both the three-drug regimen plus ribavirin, which was effective but resulted in significant hemoglobin reduction in eight patients that required dosage interruptions. All patients were then able to restart and continue treatment, said Dr. Pockros, a gastroenterologist at the Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, Calif.

The efficacy and safety of these three direct antivirals in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease – an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of no greater than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 – contrasts with the caution that exists for another major, direct antiviral agent for hepatitis C eradication, sofosbuvir, which is marketed as Sovaldi as an individual drug and as Harvoni when formulated with ledipavir. The labels for both forms of sofosbuvir say that the drug’s safety and efficacy “has not been established in patients with severe renal impairment (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2) or end stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring hemodialysis. No dose recommendation can be given for patients with severe renal impairment or ESRD.”

A new phase of the trial starting soon will test whether patients infected with genotype 1a HCV can be effectively treated with the three direct antiviral agents alone without ribavirin, Dr. Pockros said. Another soon-to-start aspect of the trial will test the regimen in patients with cirrhosis. The current series has so far enrolled only treatment naive patients without cirrhosis.

The RUBY-1 trial has been run at nine U.S. centers, where researchers enrolled seven patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease (an eGFR of 15-29 ml/min/ 1.73m2), and 13 patients on hemodialysis and with stage 5 chronic kidney disease, defined as an eGFR of less than 15 mL/min/1.73m2. Fourteen of the 20 enrolled patients (70%) were African American, and 15% were Hispanic, a demographic pattern that is “a fair representation” of U.S. patients with both hepatitis C infection and end-stage renal disease, Dr. Prockros said.

The three direct antivirals tested in the current study are all metabolized in the liver and require no dose modification when used in patients with renal dysfunction. Pharmacokinetic studies done as part of the study showed no differences in blood levels of these drugs in the patients with advanced chronic kidney disease compared with historical patients with better renal function. Several reports published in 2014 documented the efficacy of ombitasvir, paritaprevir plus ritonavir, and dasabuvir for eradicating chronic HCV infection in patients with more normal renal function (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:1594-1603, 1604-14, 1973-82, 1983-92).

RUBY-1 was sponsored by AbbVie, which markets Viekira Pak. Dr. Pockros disclosed ties with AbbVie, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Merck, Conatus, and Roche Molecular.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

VIENNA – A 12-week, fixed-dose regimen safely and effectively eradicated chronic hepatitis C infection from the first 10 patients with advanced chronic kidney disease in a multicenter U.S. series.

The regimen of three direct antiviral agents is already on the U.S. market. So far, 20 HCV patients with advanced chronic kidney disease have been treated and there have been no cases of virologic failure. All 10 patients who have been followed for at least 4 weeks after completing treatment sustained their virologic response, Dr. Paul J. Pockros said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

The series has exclusively enrolled patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. The seven enrolled patients infected with genotype 1b HCV received the three direct antiviral agents only, the combination of ombitasvir, paritaprevir boosted with ritonavir, and dasabuvir, which together are marketed as Viekira Pak. The 13 patients with a genotype 1a infection received treatment with both the three-drug regimen plus ribavirin, which was effective but resulted in significant hemoglobin reduction in eight patients that required dosage interruptions. All patients were then able to restart and continue treatment, said Dr. Pockros, a gastroenterologist at the Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, Calif.

The efficacy and safety of these three direct antivirals in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease – an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of no greater than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 – contrasts with the caution that exists for another major, direct antiviral agent for hepatitis C eradication, sofosbuvir, which is marketed as Sovaldi as an individual drug and as Harvoni when formulated with ledipavir. The labels for both forms of sofosbuvir say that the drug’s safety and efficacy “has not been established in patients with severe renal impairment (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2) or end stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring hemodialysis. No dose recommendation can be given for patients with severe renal impairment or ESRD.”

A new phase of the trial starting soon will test whether patients infected with genotype 1a HCV can be effectively treated with the three direct antiviral agents alone without ribavirin, Dr. Pockros said. Another soon-to-start aspect of the trial will test the regimen in patients with cirrhosis. The current series has so far enrolled only treatment naive patients without cirrhosis.

The RUBY-1 trial has been run at nine U.S. centers, where researchers enrolled seven patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease (an eGFR of 15-29 ml/min/ 1.73m2), and 13 patients on hemodialysis and with stage 5 chronic kidney disease, defined as an eGFR of less than 15 mL/min/1.73m2. Fourteen of the 20 enrolled patients (70%) were African American, and 15% were Hispanic, a demographic pattern that is “a fair representation” of U.S. patients with both hepatitis C infection and end-stage renal disease, Dr. Prockros said.

The three direct antivirals tested in the current study are all metabolized in the liver and require no dose modification when used in patients with renal dysfunction. Pharmacokinetic studies done as part of the study showed no differences in blood levels of these drugs in the patients with advanced chronic kidney disease compared with historical patients with better renal function. Several reports published in 2014 documented the efficacy of ombitasvir, paritaprevir plus ritonavir, and dasabuvir for eradicating chronic HCV infection in patients with more normal renal function (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:1594-1603, 1604-14, 1973-82, 1983-92).

RUBY-1 was sponsored by AbbVie, which markets Viekira Pak. Dr. Pockros disclosed ties with AbbVie, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Merck, Conatus, and Roche Molecular.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

VIENNA – A 12-week, fixed-dose regimen safely and effectively eradicated chronic hepatitis C infection from the first 10 patients with advanced chronic kidney disease in a multicenter U.S. series.

The regimen of three direct antiviral agents is already on the U.S. market. So far, 20 HCV patients with advanced chronic kidney disease have been treated and there have been no cases of virologic failure. All 10 patients who have been followed for at least 4 weeks after completing treatment sustained their virologic response, Dr. Paul J. Pockros said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

The series has exclusively enrolled patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. The seven enrolled patients infected with genotype 1b HCV received the three direct antiviral agents only, the combination of ombitasvir, paritaprevir boosted with ritonavir, and dasabuvir, which together are marketed as Viekira Pak. The 13 patients with a genotype 1a infection received treatment with both the three-drug regimen plus ribavirin, which was effective but resulted in significant hemoglobin reduction in eight patients that required dosage interruptions. All patients were then able to restart and continue treatment, said Dr. Pockros, a gastroenterologist at the Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, Calif.

The efficacy and safety of these three direct antivirals in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease – an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of no greater than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 – contrasts with the caution that exists for another major, direct antiviral agent for hepatitis C eradication, sofosbuvir, which is marketed as Sovaldi as an individual drug and as Harvoni when formulated with ledipavir. The labels for both forms of sofosbuvir say that the drug’s safety and efficacy “has not been established in patients with severe renal impairment (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2) or end stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring hemodialysis. No dose recommendation can be given for patients with severe renal impairment or ESRD.”

A new phase of the trial starting soon will test whether patients infected with genotype 1a HCV can be effectively treated with the three direct antiviral agents alone without ribavirin, Dr. Pockros said. Another soon-to-start aspect of the trial will test the regimen in patients with cirrhosis. The current series has so far enrolled only treatment naive patients without cirrhosis.

The RUBY-1 trial has been run at nine U.S. centers, where researchers enrolled seven patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease (an eGFR of 15-29 ml/min/ 1.73m2), and 13 patients on hemodialysis and with stage 5 chronic kidney disease, defined as an eGFR of less than 15 mL/min/1.73m2. Fourteen of the 20 enrolled patients (70%) were African American, and 15% were Hispanic, a demographic pattern that is “a fair representation” of U.S. patients with both hepatitis C infection and end-stage renal disease, Dr. Prockros said.

The three direct antivirals tested in the current study are all metabolized in the liver and require no dose modification when used in patients with renal dysfunction. Pharmacokinetic studies done as part of the study showed no differences in blood levels of these drugs in the patients with advanced chronic kidney disease compared with historical patients with better renal function. Several reports published in 2014 documented the efficacy of ombitasvir, paritaprevir plus ritonavir, and dasabuvir for eradicating chronic HCV infection in patients with more normal renal function (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:1594-1603, 1604-14, 1973-82, 1983-92).

RUBY-1 was sponsored by AbbVie, which markets Viekira Pak. Dr. Pockros disclosed ties with AbbVie, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Merck, Conatus, and Roche Molecular.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE INTERNATIONAL LIVER CONGRESS 2015

Key clinical point: The trio of direct antiviral agents marketed as Viekira Pak safely eradicated chronic genotype 1 hepatitis C infection in patients with chronic kidney disease.

Major finding: All 10 patients followed so far to at least 4 weeks after completing treatment maintained a sustained virologic response.

Data source: RUBY-1, an open-label series of 20 patients with chronic HCV and advanced chronic kidney disease.

Disclosures: RUBY-1 was sponsored by AbbVie, which markets Viekira Pak. Dr. Pockros disclosed ties with AbbVie, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Merck, Conatus, and Roche Molecular.

ILC: Europe issues hepatitis C treatment priority list

VIENNA – The new European recommendations for diagnosing and treating hepatitis C infection highlight the paradox gripping the field: Safe and potent antiviral drugs are available to cure most patients after 12 weeks of treatment, but cure is not broadly available because the agents are prohibitively expensive.

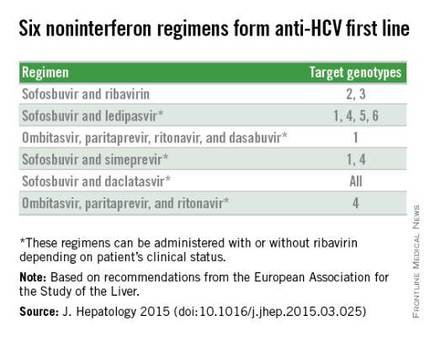

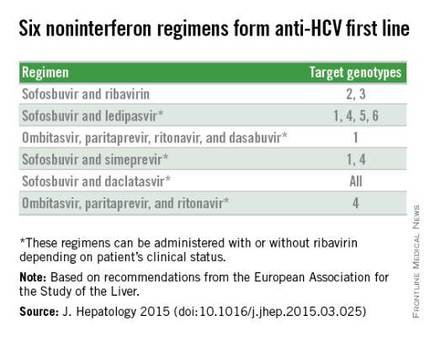

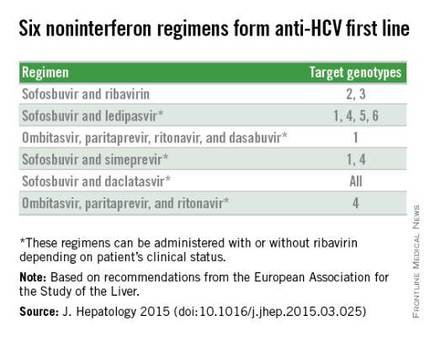

“Virtually everyone infected by hepatitis C virus [HCV] has the right to be treated,“ Dr. Jean-Michel Pawlotsky said during a session at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) that introduced the association’s new hepatitis C treatment recommendations.

The recommendations, released online around the time of the meeting, say: “Because of the approval of highly efficacious new HCV treatment regimens, access to therapy must be broadened.” In addition, they call for expanded screening to find more of the many unidentified cases of chronic hepatitis C infection (J. Hepatology 2015 [doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2015.03.025]). “However, we also have to acknowledge the reality that these drugs are currently too expensive, and the huge number of patients with HCV infection makes it impossible that we could treat all infected patients over the next couple of years,” said Dr. Pawlotsky, head of the department of virology at the Henri Mondor University Hospital in Créteil, France.