User login

HCV Hub

AbbVie

acid

addicted

addiction

adolescent

adult sites

Advocacy

advocacy

agitated states

AJO, postsurgical analgesic, knee, replacement, surgery

alcohol

amphetamine

androgen

antibody

apple cider vinegar

assistance

Assistance

association

at home

attorney

audit

ayurvedic

baby

ban

baricitinib

bed bugs

best

bible

bisexual

black

bleach

blog

bulimia nervosa

buy

cannabis

certificate

certification

certified

cervical cancer, concurrent chemoradiotherapy, intravoxel incoherent motion magnetic resonance imaging, MRI, IVIM, diffusion-weighted MRI, DWI

charlie sheen

cheap

cheapest

child

childhood

childlike

children

chronic fatigue syndrome

Cladribine Tablets

cocaine

cock

combination therapies, synergistic antitumor efficacy, pertuzumab, trastuzumab, ipilimumab, nivolumab, palbociclib, letrozole, lapatinib, docetaxel, trametinib, dabrafenib, carflzomib, lenalidomide

contagious

Cortical Lesions

cream

creams

crime

criminal

cure

dangerous

dangers

dasabuvir

Dasabuvir

dead

deadly

death

dementia

dependence

dependent

depression

dermatillomania

die

diet

direct-acting antivirals

Disability

Discount

discount

dog

drink

drug abuse

drug-induced

dying

eastern medicine

eat

ect

eczema

electroconvulsive therapy

electromagnetic therapy

electrotherapy

epa

epilepsy

erectile dysfunction

explosive disorder

fake

Fake-ovir

fatal

fatalities

fatality

fibromyalgia

financial

Financial

fish oil

food

foods

foundation

free

Gabriel Pardo

gaston

general hospital

genetic

geriatric

Giancarlo Comi

gilead

Gilead

glaucoma

Glenn S. Williams

Glenn Williams

Gloria Dalla Costa

gonorrhea

Greedy

greedy

guns

hallucinations

harvoni

Harvoni

herbal

herbs

heroin

herpes

Hidradenitis Suppurativa,

holistic

home

home remedies

home remedy

homeopathic

homeopathy

hydrocortisone

ice

image

images

job

kid

kids

kill

killer

laser

lawsuit

lawyer

ledipasvir

Ledipasvir

lesbian

lesions

lights

liver

lupus

marijuana

melancholic

memory loss

menopausal

mental retardation

military

milk

moisturizers

monoamine oxidase inhibitor drugs

MRI

MS

murder

national

natural

natural cure

natural cures

natural medications

natural medicine

natural medicines

natural remedies

natural remedy

natural treatment

natural treatments

naturally

Needy

needy

Neurology Reviews

neuropathic

nightclub massacre

nightclub shooting

nude

nudity

nutraceuticals

OASIS

oasis

off label

ombitasvir

Ombitasvir

ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir with dasabuvir

orlando shooting

overactive thyroid gland

overdose

overdosed

Paolo Preziosa

paritaprevir

Paritaprevir

pediatric

pedophile

photo

photos

picture

post partum

postnatal

pregnancy

pregnant

prenatal

prepartum

prison

program

Program

Protest

protest

psychedelics

pulse nightclub

puppy

purchase

purchasing

rape

recall

recreational drug

Rehabilitation

Retinal Measurements

retrograde ejaculation

risperdal

ritonavir

Ritonavir

ritonavir with dasabuvir

robin williams

sales

sasquatch

schizophrenia

seizure

seizures

sex

sexual

sexy

shock treatment

silver

sleep disorders

smoking

sociopath

sofosbuvir

Sofosbuvir

sovaldi

ssri

store

sue

suicidal

suicide

supplements

support

Support

Support Path

teen

teenage

teenagers

Telerehabilitation

testosterone

Th17

Th17:FoxP3+Treg cell ratio

Th22

toxic

toxin

tragedy

treatment resistant

V Pak

vagina

velpatasvir

Viekira Pa

Viekira Pak

viekira pak

violence

virgin

vitamin

VPak

weight loss

withdrawal

wrinkles

xxx

young adult

young adults

zoloft

financial

sofosbuvir

ritonavir with dasabuvir

discount

support path

program

ritonavir

greedy

ledipasvir

assistance

viekira pak

vpak

advocacy

needy

protest

abbvie

paritaprevir

ombitasvir

direct-acting antivirals

dasabuvir

gilead

fake-ovir

support

v pak

oasis

harvoni

All-oral simeprevir-sofosbuvir beat interferon-based regimen for HCV with compensated cirrhosis

Patients with compensated cirrhosis and chronic genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infections were significantly more likely to clear their infections and had fewer adverse effects when treated with simeprevir and sofosbuvir instead of peginterferon, ribavirin, and sofosbuvir, investigators reported in the April issue of Gastroenterology. “Patients given the interferon-containing regimen had a significantly greater rate of virologic relapse than patients given simeprevir and sofosbuvir ... and reported worse outcomes and more side effects,” said Dr. Brian L. Pearlman and his associates of Atlanta Medical Center and Emory University, Atlanta.

Liver disease associated with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection causes at least 350,000 deaths per year worldwide. Genotype 1 (GT-1) HCV is the most common HCV strain and the hardest to treat, especially when patients have cirrhosis. Treatments for chronic GT-1 HCV infections historically included interferon, but achieved only moderate rates of sustained virologic response (SVR) and caused adverse somatic and psychiatric effects. All-oral, interferon-free regimens are now in widespread use, but many of the pivotal trials were industry sponsored and had strict enrollment criteria, potentially limiting their generalizability in community settings, the researchers reported (Gastroenterology 2015 April [doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.12.027]).Their open-label trial included 82 patients with HCV GT-1a infection and Child’s grade A cirrhosis recruited from two clinical practices in Atlanta. Thirty-two of the patients were treatment naive, while 50 had previously not responded to peginterferon and ribavirin treatment. Patients were randomized to either 12 weeks of all-oral simeprevir (150 mg/day) and sofosbuvir (400 mg/day), or peginterferon alfa 2b (1.5 mcg/kg per week), ribavirin (1000-1200 mg/day), and sofosbuvir (400 mg/day).Fully 54 of 58 (93%) patients given the simeprevir-sofosbuvir regimen had undetectable levels of HCV RNA at 12 weeks (SVR12), compared with 18 of 24 (75%) patients who received the interferon-containing regimen (P = .02), the researchers reported. Rates of SVR12 among prior nonresponders were 92% and 64%, and were 95% and 80% for treatment-naive patients, although P-values did not reach statistical significance. The interferon group also had a higher rate of virologic relapse than did patients given simeprevir and sofosbuvir (P = .009), and had worse self-reported outcomes and more side effects, the researchers said. Patients in both groups who achieved SVR12 had higher quality-of-life scores than those who did not. Notably, almost half of patients were African American, a group that has historically had lower cure rates compared with other racial groups, said the investigators.

“Given that several new regimens for genotype 1 infection, including the sofosbuvir-ledipasvir combination pill, already have been approved, we believe that this study is very timely,” Dr. Pearlman and his associates said. “Although these are not head-to-head comparisons, the 12-week simeprevir and sofosbuvir regimen in this trial may compare favorably with the SVR rates for 12 weeks of sofosbuvir/ledipasvir and 12 weeks of the regimen, paritaprevir/ritonavir, ombitasvir and dasabuvir plus ribavirin for patients with cirrhosis, particularly for prior nonresponders to older therapies, with the caveat that many more patients were studied in the registration trials.”While industry-sponsored trials have had psychiatric exclusion criteria, several patients in the open-label trial had serious psychiatric conditions, said the researchers. A patient with stable bipolar disorder received the interferon-containing regimen, and two patients with stable schizophrenia received the all-oral regimen. None reported worsening psychiatric symptoms on treatment.

Dr. Pearlman reported having contracted research for Johnson & Johnson, Gilead, Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Merck; and having served on speaker and advisory boards for Johnson & Johnson, Gilead, and Abbvie. He also was an investigator and author in the COSMOS trial of simeprevir and sofosbuvir in patients with HCV/HIV coinfection. The other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

At the time of sofosbuvir (SOF) and simeprevir (SMV) approval, efficacy results of the combinations assessed in this study were still limited, especially in patients with cirrhosis, GT-1a, and/or previous nonresponse. The recent study by Dr. Pearlman and his associates aims to give light to some of the questions

|

| Dr. Xavier Forns |

raised. In this open-label trial, 82 patients with GT-1a cirrhosis (61% null responders) were recruited. Patients were randomized 2:1 to either 12 weeks of all-oral SMV/SOF or to peginterferon (PEG)/ribavirin (RBV)/SOF. Fully 93% of patients given the all-oral regimen achieved SVR12, compared with 75% who received the interferon-containing regimen. SVR12 rates were higher in the SMV/SOF arm than in the PEG/RBV/SOF arm, independent of previous response (92% vs. 64% in null responders and 95% vs. 80% in naive patients). Moreover, virologic relapse was lower in the all-oral arm (12.5% vs. 8%; P = .009). These results, however, are based on a limited number of patients, particularly in the interferon-containing arm. In addition, the PEG used in this study was alfa-2b, which has not been studied in combination with SOF in clinical trials (its potential impact is thus unknown). One important point of the study is the lack of prognostic value of early viral kinetics: Rapid virologic response was not related to SVR12, which has been a hallmark in previous interferon-based regimens.

Regarding safety and tolerance, there were poorer self-reported outcomes and more side effects in the interferon group. The latter seems obvious because of

|

| Dr. Sabela Lens |

the well-known interferon profile, but RBV has been associated with higher rates of anemia in patients with cirrhosis undergoing interferon-free regimens. The use of SMV/SOF without RBV is certainly a crucial point of the study.

With the inherent limitations of the small number of patients, the study by Dr. Pearlman and his associates supports a greater efficacy and a better tolerance for a regimen combining SMV/SOF as compared to PEG/RBV/SOF in patients with GT-1a cirrhosis.

Dr. Sabela Lens and Dr. Xavier Forns are in the Liver Unit, Hospital Clínic Barcelona, IDIBAPS and CIBERehd, University of Barcelona. Dr. Lens has acted as an adviser for Janssen, MSD, and Gilead, and Dr. Forns has acted as an adviser for Janssen, Abbvie, and Gilead and has received unrestricted grant support from Janssen and MSD.

At the time of sofosbuvir (SOF) and simeprevir (SMV) approval, efficacy results of the combinations assessed in this study were still limited, especially in patients with cirrhosis, GT-1a, and/or previous nonresponse. The recent study by Dr. Pearlman and his associates aims to give light to some of the questions

|

| Dr. Xavier Forns |

raised. In this open-label trial, 82 patients with GT-1a cirrhosis (61% null responders) were recruited. Patients were randomized 2:1 to either 12 weeks of all-oral SMV/SOF or to peginterferon (PEG)/ribavirin (RBV)/SOF. Fully 93% of patients given the all-oral regimen achieved SVR12, compared with 75% who received the interferon-containing regimen. SVR12 rates were higher in the SMV/SOF arm than in the PEG/RBV/SOF arm, independent of previous response (92% vs. 64% in null responders and 95% vs. 80% in naive patients). Moreover, virologic relapse was lower in the all-oral arm (12.5% vs. 8%; P = .009). These results, however, are based on a limited number of patients, particularly in the interferon-containing arm. In addition, the PEG used in this study was alfa-2b, which has not been studied in combination with SOF in clinical trials (its potential impact is thus unknown). One important point of the study is the lack of prognostic value of early viral kinetics: Rapid virologic response was not related to SVR12, which has been a hallmark in previous interferon-based regimens.

Regarding safety and tolerance, there were poorer self-reported outcomes and more side effects in the interferon group. The latter seems obvious because of

|

| Dr. Sabela Lens |

the well-known interferon profile, but RBV has been associated with higher rates of anemia in patients with cirrhosis undergoing interferon-free regimens. The use of SMV/SOF without RBV is certainly a crucial point of the study.

With the inherent limitations of the small number of patients, the study by Dr. Pearlman and his associates supports a greater efficacy and a better tolerance for a regimen combining SMV/SOF as compared to PEG/RBV/SOF in patients with GT-1a cirrhosis.

Dr. Sabela Lens and Dr. Xavier Forns are in the Liver Unit, Hospital Clínic Barcelona, IDIBAPS and CIBERehd, University of Barcelona. Dr. Lens has acted as an adviser for Janssen, MSD, and Gilead, and Dr. Forns has acted as an adviser for Janssen, Abbvie, and Gilead and has received unrestricted grant support from Janssen and MSD.

At the time of sofosbuvir (SOF) and simeprevir (SMV) approval, efficacy results of the combinations assessed in this study were still limited, especially in patients with cirrhosis, GT-1a, and/or previous nonresponse. The recent study by Dr. Pearlman and his associates aims to give light to some of the questions

|

| Dr. Xavier Forns |

raised. In this open-label trial, 82 patients with GT-1a cirrhosis (61% null responders) were recruited. Patients were randomized 2:1 to either 12 weeks of all-oral SMV/SOF or to peginterferon (PEG)/ribavirin (RBV)/SOF. Fully 93% of patients given the all-oral regimen achieved SVR12, compared with 75% who received the interferon-containing regimen. SVR12 rates were higher in the SMV/SOF arm than in the PEG/RBV/SOF arm, independent of previous response (92% vs. 64% in null responders and 95% vs. 80% in naive patients). Moreover, virologic relapse was lower in the all-oral arm (12.5% vs. 8%; P = .009). These results, however, are based on a limited number of patients, particularly in the interferon-containing arm. In addition, the PEG used in this study was alfa-2b, which has not been studied in combination with SOF in clinical trials (its potential impact is thus unknown). One important point of the study is the lack of prognostic value of early viral kinetics: Rapid virologic response was not related to SVR12, which has been a hallmark in previous interferon-based regimens.

Regarding safety and tolerance, there were poorer self-reported outcomes and more side effects in the interferon group. The latter seems obvious because of

|

| Dr. Sabela Lens |

the well-known interferon profile, but RBV has been associated with higher rates of anemia in patients with cirrhosis undergoing interferon-free regimens. The use of SMV/SOF without RBV is certainly a crucial point of the study.

With the inherent limitations of the small number of patients, the study by Dr. Pearlman and his associates supports a greater efficacy and a better tolerance for a regimen combining SMV/SOF as compared to PEG/RBV/SOF in patients with GT-1a cirrhosis.

Dr. Sabela Lens and Dr. Xavier Forns are in the Liver Unit, Hospital Clínic Barcelona, IDIBAPS and CIBERehd, University of Barcelona. Dr. Lens has acted as an adviser for Janssen, MSD, and Gilead, and Dr. Forns has acted as an adviser for Janssen, Abbvie, and Gilead and has received unrestricted grant support from Janssen and MSD.

Patients with compensated cirrhosis and chronic genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infections were significantly more likely to clear their infections and had fewer adverse effects when treated with simeprevir and sofosbuvir instead of peginterferon, ribavirin, and sofosbuvir, investigators reported in the April issue of Gastroenterology. “Patients given the interferon-containing regimen had a significantly greater rate of virologic relapse than patients given simeprevir and sofosbuvir ... and reported worse outcomes and more side effects,” said Dr. Brian L. Pearlman and his associates of Atlanta Medical Center and Emory University, Atlanta.

Liver disease associated with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection causes at least 350,000 deaths per year worldwide. Genotype 1 (GT-1) HCV is the most common HCV strain and the hardest to treat, especially when patients have cirrhosis. Treatments for chronic GT-1 HCV infections historically included interferon, but achieved only moderate rates of sustained virologic response (SVR) and caused adverse somatic and psychiatric effects. All-oral, interferon-free regimens are now in widespread use, but many of the pivotal trials were industry sponsored and had strict enrollment criteria, potentially limiting their generalizability in community settings, the researchers reported (Gastroenterology 2015 April [doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.12.027]).Their open-label trial included 82 patients with HCV GT-1a infection and Child’s grade A cirrhosis recruited from two clinical practices in Atlanta. Thirty-two of the patients were treatment naive, while 50 had previously not responded to peginterferon and ribavirin treatment. Patients were randomized to either 12 weeks of all-oral simeprevir (150 mg/day) and sofosbuvir (400 mg/day), or peginterferon alfa 2b (1.5 mcg/kg per week), ribavirin (1000-1200 mg/day), and sofosbuvir (400 mg/day).Fully 54 of 58 (93%) patients given the simeprevir-sofosbuvir regimen had undetectable levels of HCV RNA at 12 weeks (SVR12), compared with 18 of 24 (75%) patients who received the interferon-containing regimen (P = .02), the researchers reported. Rates of SVR12 among prior nonresponders were 92% and 64%, and were 95% and 80% for treatment-naive patients, although P-values did not reach statistical significance. The interferon group also had a higher rate of virologic relapse than did patients given simeprevir and sofosbuvir (P = .009), and had worse self-reported outcomes and more side effects, the researchers said. Patients in both groups who achieved SVR12 had higher quality-of-life scores than those who did not. Notably, almost half of patients were African American, a group that has historically had lower cure rates compared with other racial groups, said the investigators.

“Given that several new regimens for genotype 1 infection, including the sofosbuvir-ledipasvir combination pill, already have been approved, we believe that this study is very timely,” Dr. Pearlman and his associates said. “Although these are not head-to-head comparisons, the 12-week simeprevir and sofosbuvir regimen in this trial may compare favorably with the SVR rates for 12 weeks of sofosbuvir/ledipasvir and 12 weeks of the regimen, paritaprevir/ritonavir, ombitasvir and dasabuvir plus ribavirin for patients with cirrhosis, particularly for prior nonresponders to older therapies, with the caveat that many more patients were studied in the registration trials.”While industry-sponsored trials have had psychiatric exclusion criteria, several patients in the open-label trial had serious psychiatric conditions, said the researchers. A patient with stable bipolar disorder received the interferon-containing regimen, and two patients with stable schizophrenia received the all-oral regimen. None reported worsening psychiatric symptoms on treatment.

Dr. Pearlman reported having contracted research for Johnson & Johnson, Gilead, Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Merck; and having served on speaker and advisory boards for Johnson & Johnson, Gilead, and Abbvie. He also was an investigator and author in the COSMOS trial of simeprevir and sofosbuvir in patients with HCV/HIV coinfection. The other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Patients with compensated cirrhosis and chronic genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infections were significantly more likely to clear their infections and had fewer adverse effects when treated with simeprevir and sofosbuvir instead of peginterferon, ribavirin, and sofosbuvir, investigators reported in the April issue of Gastroenterology. “Patients given the interferon-containing regimen had a significantly greater rate of virologic relapse than patients given simeprevir and sofosbuvir ... and reported worse outcomes and more side effects,” said Dr. Brian L. Pearlman and his associates of Atlanta Medical Center and Emory University, Atlanta.

Liver disease associated with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection causes at least 350,000 deaths per year worldwide. Genotype 1 (GT-1) HCV is the most common HCV strain and the hardest to treat, especially when patients have cirrhosis. Treatments for chronic GT-1 HCV infections historically included interferon, but achieved only moderate rates of sustained virologic response (SVR) and caused adverse somatic and psychiatric effects. All-oral, interferon-free regimens are now in widespread use, but many of the pivotal trials were industry sponsored and had strict enrollment criteria, potentially limiting their generalizability in community settings, the researchers reported (Gastroenterology 2015 April [doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.12.027]).Their open-label trial included 82 patients with HCV GT-1a infection and Child’s grade A cirrhosis recruited from two clinical practices in Atlanta. Thirty-two of the patients were treatment naive, while 50 had previously not responded to peginterferon and ribavirin treatment. Patients were randomized to either 12 weeks of all-oral simeprevir (150 mg/day) and sofosbuvir (400 mg/day), or peginterferon alfa 2b (1.5 mcg/kg per week), ribavirin (1000-1200 mg/day), and sofosbuvir (400 mg/day).Fully 54 of 58 (93%) patients given the simeprevir-sofosbuvir regimen had undetectable levels of HCV RNA at 12 weeks (SVR12), compared with 18 of 24 (75%) patients who received the interferon-containing regimen (P = .02), the researchers reported. Rates of SVR12 among prior nonresponders were 92% and 64%, and were 95% and 80% for treatment-naive patients, although P-values did not reach statistical significance. The interferon group also had a higher rate of virologic relapse than did patients given simeprevir and sofosbuvir (P = .009), and had worse self-reported outcomes and more side effects, the researchers said. Patients in both groups who achieved SVR12 had higher quality-of-life scores than those who did not. Notably, almost half of patients were African American, a group that has historically had lower cure rates compared with other racial groups, said the investigators.

“Given that several new regimens for genotype 1 infection, including the sofosbuvir-ledipasvir combination pill, already have been approved, we believe that this study is very timely,” Dr. Pearlman and his associates said. “Although these are not head-to-head comparisons, the 12-week simeprevir and sofosbuvir regimen in this trial may compare favorably with the SVR rates for 12 weeks of sofosbuvir/ledipasvir and 12 weeks of the regimen, paritaprevir/ritonavir, ombitasvir and dasabuvir plus ribavirin for patients with cirrhosis, particularly for prior nonresponders to older therapies, with the caveat that many more patients were studied in the registration trials.”While industry-sponsored trials have had psychiatric exclusion criteria, several patients in the open-label trial had serious psychiatric conditions, said the researchers. A patient with stable bipolar disorder received the interferon-containing regimen, and two patients with stable schizophrenia received the all-oral regimen. None reported worsening psychiatric symptoms on treatment.

Dr. Pearlman reported having contracted research for Johnson & Johnson, Gilead, Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Merck; and having served on speaker and advisory boards for Johnson & Johnson, Gilead, and Abbvie. He also was an investigator and author in the COSMOS trial of simeprevir and sofosbuvir in patients with HCV/HIV coinfection. The other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Key clinical point: An all-oral simeprevir-sofosbuvir combination outperformed peginterferon/ribavirin/sofosbuvir in patients with genotype 1a HCV infection and compensated cirrhosis.

Major finding: Rates of sustained virologic response at 12 weeks were 93% for the simeprevir-sofosbuvir regimen and 75% for the interferon-containing regimen (P = .02).

Data source: Prospective open-label study of 82 treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients with HCV infection and Child’s grade A cirrhosis.

Disclosures: Dr. Pearlman reported having contracted research for Johnson & Johnson, Gilead, Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Merck; and having served on speaker and advisory boards for Johnson & Johnson, Gilead, and Abbvie. Dr. Pearlman also reported having been an investigator and author in the COSMOS trial of sofosbuvir and simeprevir. The other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

New hepatitis treatment cost effective for some patient types

For individuals infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV), new regimens are highly effective, but also very expensive, at approximately $28,000 for 4 weeks of treatment. However, the treatment is cost effective for HCV patients with cirrhosis and for those without cirrhosis who have failed other treatments, according to a new study.

In an analysis of the cost effectiveness of sofosbuvir-based treatments for patients with HCV genotypes 2 and 3, Dr. Benjamin Linas of Boston Medical Center reported that when compared with pegylated interferon and ribavirin therapy, treatment regimens based on the new direct-acting antiviral are only cost effective for select groups (Ann. Intern Med, [doi:10.7326/M15-0674]).

Cure rates with sofosbuvir are higher than are rates with the previous standard of care, and sustained virologic response (SVR) “is associated with a greatly reduced lifetime risk for liver-related morbidity and mortality,” noted Dr. Linas and his colleagues.

Using sophisticated statistical modeling to compare HCV treatment with pegylated interferon and ribavirin – the previous standard of care – to the newly Food and Drug Administration–approved sofosbuvir-ribavirin regimen, Dr. Linas explored clinical outcomes and costs for several different patient groups, including treatment-naive and treatment-experienced HCV genotype 2 and 3 patients with and without cirrhosis.

Clinical outcomes, modeled from clinical trial and observational cohort data, were expressed as life expectancy in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and lifetime medical costs. Investigators then calculated the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for each treatment strategy, dividing any additional cost for a more expensive treatment by the QALYs gained from this regimen.

Using the commonly accepted ICER threshold of $100,000 per QALY, Dr. Linas and colleagues concluded that sofosbuvir-based HCV therapy for treatment-naive patients without cirrhosis was not cost effective, with ICERs of $238,000-$266,000. Interferon-based treatments, they noted, still achieve an approximately 80% rate of cure in this population.

In the constrained resources of the real world, Dr. Linas and his associates noted that this analysis is important. “Treatment strategies that do not use limited resources where they are likely to have the greatest impact may result in unequal access to interferon-free regimens, thereby limiting the population-level benefits of new HCV treatments,” they said.

In an editorial accompanying Dr. Linas’ study, Dr. Etzion and Dr. Ghany placed this analysis of the cost-effectiveness of sofosbuvir in the context of payer and clinician priorities. They noted that “from the patient and physician perspective, the benefits of new treatment are evident.” For payers, however, resources are constrained and tough decisions will have to be made.

This cost-effectiveness analysis is needed to inform resource allocation decisions, since the cost of using direct-acting antivirals to treat all those infected in the United States alone would exceed $300 billion. In that context, the editorial noted, quality-of-life assessments become important. HCV infection causes relatively little diminution of quality of life until the stage of cirrhosis is reached; in this analysis, therefore, interferon-based regimens are still a reasonable choice for treatment-naive HCV patients without cirrhosis.

Though Dr. Linas’ study also models incremental cost-effectiveness ratios for various lower price points for sofosbuvir, the editorial authors point out that the price point for the public’s willingness to eradicate HCV has not been established.

Dr. Ohad Etzion and Dr. Marc G. Ghany are at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md. Dr. Ghany reported nonfinancial support from Bristol Meyers Squibb.

In an editorial accompanying Dr. Linas’ study, Dr. Etzion and Dr. Ghany placed this analysis of the cost-effectiveness of sofosbuvir in the context of payer and clinician priorities. They noted that “from the patient and physician perspective, the benefits of new treatment are evident.” For payers, however, resources are constrained and tough decisions will have to be made.

This cost-effectiveness analysis is needed to inform resource allocation decisions, since the cost of using direct-acting antivirals to treat all those infected in the United States alone would exceed $300 billion. In that context, the editorial noted, quality-of-life assessments become important. HCV infection causes relatively little diminution of quality of life until the stage of cirrhosis is reached; in this analysis, therefore, interferon-based regimens are still a reasonable choice for treatment-naive HCV patients without cirrhosis.

Though Dr. Linas’ study also models incremental cost-effectiveness ratios for various lower price points for sofosbuvir, the editorial authors point out that the price point for the public’s willingness to eradicate HCV has not been established.

Dr. Ohad Etzion and Dr. Marc G. Ghany are at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md. Dr. Ghany reported nonfinancial support from Bristol Meyers Squibb.

In an editorial accompanying Dr. Linas’ study, Dr. Etzion and Dr. Ghany placed this analysis of the cost-effectiveness of sofosbuvir in the context of payer and clinician priorities. They noted that “from the patient and physician perspective, the benefits of new treatment are evident.” For payers, however, resources are constrained and tough decisions will have to be made.

This cost-effectiveness analysis is needed to inform resource allocation decisions, since the cost of using direct-acting antivirals to treat all those infected in the United States alone would exceed $300 billion. In that context, the editorial noted, quality-of-life assessments become important. HCV infection causes relatively little diminution of quality of life until the stage of cirrhosis is reached; in this analysis, therefore, interferon-based regimens are still a reasonable choice for treatment-naive HCV patients without cirrhosis.

Though Dr. Linas’ study also models incremental cost-effectiveness ratios for various lower price points for sofosbuvir, the editorial authors point out that the price point for the public’s willingness to eradicate HCV has not been established.

Dr. Ohad Etzion and Dr. Marc G. Ghany are at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md. Dr. Ghany reported nonfinancial support from Bristol Meyers Squibb.

For individuals infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV), new regimens are highly effective, but also very expensive, at approximately $28,000 for 4 weeks of treatment. However, the treatment is cost effective for HCV patients with cirrhosis and for those without cirrhosis who have failed other treatments, according to a new study.

In an analysis of the cost effectiveness of sofosbuvir-based treatments for patients with HCV genotypes 2 and 3, Dr. Benjamin Linas of Boston Medical Center reported that when compared with pegylated interferon and ribavirin therapy, treatment regimens based on the new direct-acting antiviral are only cost effective for select groups (Ann. Intern Med, [doi:10.7326/M15-0674]).

Cure rates with sofosbuvir are higher than are rates with the previous standard of care, and sustained virologic response (SVR) “is associated with a greatly reduced lifetime risk for liver-related morbidity and mortality,” noted Dr. Linas and his colleagues.

Using sophisticated statistical modeling to compare HCV treatment with pegylated interferon and ribavirin – the previous standard of care – to the newly Food and Drug Administration–approved sofosbuvir-ribavirin regimen, Dr. Linas explored clinical outcomes and costs for several different patient groups, including treatment-naive and treatment-experienced HCV genotype 2 and 3 patients with and without cirrhosis.

Clinical outcomes, modeled from clinical trial and observational cohort data, were expressed as life expectancy in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and lifetime medical costs. Investigators then calculated the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for each treatment strategy, dividing any additional cost for a more expensive treatment by the QALYs gained from this regimen.

Using the commonly accepted ICER threshold of $100,000 per QALY, Dr. Linas and colleagues concluded that sofosbuvir-based HCV therapy for treatment-naive patients without cirrhosis was not cost effective, with ICERs of $238,000-$266,000. Interferon-based treatments, they noted, still achieve an approximately 80% rate of cure in this population.

In the constrained resources of the real world, Dr. Linas and his associates noted that this analysis is important. “Treatment strategies that do not use limited resources where they are likely to have the greatest impact may result in unequal access to interferon-free regimens, thereby limiting the population-level benefits of new HCV treatments,” they said.

For individuals infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV), new regimens are highly effective, but also very expensive, at approximately $28,000 for 4 weeks of treatment. However, the treatment is cost effective for HCV patients with cirrhosis and for those without cirrhosis who have failed other treatments, according to a new study.

In an analysis of the cost effectiveness of sofosbuvir-based treatments for patients with HCV genotypes 2 and 3, Dr. Benjamin Linas of Boston Medical Center reported that when compared with pegylated interferon and ribavirin therapy, treatment regimens based on the new direct-acting antiviral are only cost effective for select groups (Ann. Intern Med, [doi:10.7326/M15-0674]).

Cure rates with sofosbuvir are higher than are rates with the previous standard of care, and sustained virologic response (SVR) “is associated with a greatly reduced lifetime risk for liver-related morbidity and mortality,” noted Dr. Linas and his colleagues.

Using sophisticated statistical modeling to compare HCV treatment with pegylated interferon and ribavirin – the previous standard of care – to the newly Food and Drug Administration–approved sofosbuvir-ribavirin regimen, Dr. Linas explored clinical outcomes and costs for several different patient groups, including treatment-naive and treatment-experienced HCV genotype 2 and 3 patients with and without cirrhosis.

Clinical outcomes, modeled from clinical trial and observational cohort data, were expressed as life expectancy in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and lifetime medical costs. Investigators then calculated the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for each treatment strategy, dividing any additional cost for a more expensive treatment by the QALYs gained from this regimen.

Using the commonly accepted ICER threshold of $100,000 per QALY, Dr. Linas and colleagues concluded that sofosbuvir-based HCV therapy for treatment-naive patients without cirrhosis was not cost effective, with ICERs of $238,000-$266,000. Interferon-based treatments, they noted, still achieve an approximately 80% rate of cure in this population.

In the constrained resources of the real world, Dr. Linas and his associates noted that this analysis is important. “Treatment strategies that do not use limited resources where they are likely to have the greatest impact may result in unequal access to interferon-free regimens, thereby limiting the population-level benefits of new HCV treatments,” they said.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: New treatment for hepatitis C virus (HCV) is cost effective for patients with cirrhosis and for those without cirrhosis who have failed other treatments.

Major finding: Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios for sofosbuvir-based HCV treatment ranged from $238,000 to $266,000 for treatment-naive noncirrhotic patients, exceeding the $100,000 per quality-adjusted life-year cost-effectiveness threshold.

Data source: Application of the Hepatitis C Cost-Effectiveness model to clinical trial and observational cohort data.

Disclosures: The National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease provided funding. Dr. Weinstein reported receiving personal compensation from OptumInsight; Dr. Kim reported receiving grants and personal compensation from Gilead Sciences, AbbVie Pharmaceuticals, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. The remaining authors reported no relevant disclosures.

FDA: Avoid using amiodarone with some hepatitis C antivirals

Taking the antiarrythmic drug amiodarone with the hepatitis C antiviral drugs ledipasvir and sofosbuvir, or with sofosbuvir plus another direct-acting antiviral drug, has been associated with cases of symptomatic bradycardia – including a fatal cardiac arrest – according to the Food and Drug Administration.

Because of the reports, the antiviral drugs’ labels now recommend against using amiodarone with those hepatitis C drugs.

An FDA statement issued March 24 described the bradycardia cases as “serious and life-threatening.” Gilead Sciences markets the ledipasvir and sofosbuvir combination as Harvoni and markets sofosbuvir as Sovaldi to treat chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.

Gilead issued a “Dear Health Care Provider” letter that provides further details of the cases. There have been nine postmarketing reports of symptomatic bradycardia in patients who were taking amiodarone with Harvoni; amiodarone with Sovaldi plus another hepatitis C antiviral drug, simeprevir (Olysio); or amiodarone with an investigational hepatitis C antiviral drug, daclatasvir.

Of those cases, six occurred with in the first 24 hours of starting treatment with the antivirals, and three cases occurred within the first 2-12 days after antiviral therapy was started. A pacemaker was needed in three cases, and one case was a fatal cardiac arrest.

In three cases, a “rechallenge with HCV treatment in the setting of continued amiodarone therapy resulted in recurrence of symptomatic bradycardia,” according to the Gilead letter.

The effect of coadministration on the blood levels of the antiviral drugs is not known, nor is the mechanism behind the cardiac effect.

The labeling of the fixed-dose combination of ledipasvir and sofosbuvir (Harvoni) now includes a section on “serious symptomatic bradycardia” when coadministered with amiodarone, and says that coadministration is not recommended. The label adds that if a patient on amiodarone or Harvoni has no other alternative than to take that combination, patients should be counseled about the bradycardia risk.

Cardiac monitoring is recommended for inpatients during the first 48 hours the patient is taking the drugs, “after which outpatient or self-monitoring of the heart rate should occur on a daily basis through at least the first 2 weeks of treatment.”

The label notes that amiodarone has a long half-life, so cardiac monitoring is still necessary if the patient discontinues amiodarone just before starting treatment with Harvoni. Similar labeling changes have been made to the Sovaldi label.

Adverse events associated with Harvoni or Sovaldi should be reported to the FDA’s MedWatch program at 800-332-1088 or www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/.

Taking the antiarrythmic drug amiodarone with the hepatitis C antiviral drugs ledipasvir and sofosbuvir, or with sofosbuvir plus another direct-acting antiviral drug, has been associated with cases of symptomatic bradycardia – including a fatal cardiac arrest – according to the Food and Drug Administration.

Because of the reports, the antiviral drugs’ labels now recommend against using amiodarone with those hepatitis C drugs.

An FDA statement issued March 24 described the bradycardia cases as “serious and life-threatening.” Gilead Sciences markets the ledipasvir and sofosbuvir combination as Harvoni and markets sofosbuvir as Sovaldi to treat chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.

Gilead issued a “Dear Health Care Provider” letter that provides further details of the cases. There have been nine postmarketing reports of symptomatic bradycardia in patients who were taking amiodarone with Harvoni; amiodarone with Sovaldi plus another hepatitis C antiviral drug, simeprevir (Olysio); or amiodarone with an investigational hepatitis C antiviral drug, daclatasvir.

Of those cases, six occurred with in the first 24 hours of starting treatment with the antivirals, and three cases occurred within the first 2-12 days after antiviral therapy was started. A pacemaker was needed in three cases, and one case was a fatal cardiac arrest.

In three cases, a “rechallenge with HCV treatment in the setting of continued amiodarone therapy resulted in recurrence of symptomatic bradycardia,” according to the Gilead letter.

The effect of coadministration on the blood levels of the antiviral drugs is not known, nor is the mechanism behind the cardiac effect.

The labeling of the fixed-dose combination of ledipasvir and sofosbuvir (Harvoni) now includes a section on “serious symptomatic bradycardia” when coadministered with amiodarone, and says that coadministration is not recommended. The label adds that if a patient on amiodarone or Harvoni has no other alternative than to take that combination, patients should be counseled about the bradycardia risk.

Cardiac monitoring is recommended for inpatients during the first 48 hours the patient is taking the drugs, “after which outpatient or self-monitoring of the heart rate should occur on a daily basis through at least the first 2 weeks of treatment.”

The label notes that amiodarone has a long half-life, so cardiac monitoring is still necessary if the patient discontinues amiodarone just before starting treatment with Harvoni. Similar labeling changes have been made to the Sovaldi label.

Adverse events associated with Harvoni or Sovaldi should be reported to the FDA’s MedWatch program at 800-332-1088 or www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/.

Taking the antiarrythmic drug amiodarone with the hepatitis C antiviral drugs ledipasvir and sofosbuvir, or with sofosbuvir plus another direct-acting antiviral drug, has been associated with cases of symptomatic bradycardia – including a fatal cardiac arrest – according to the Food and Drug Administration.

Because of the reports, the antiviral drugs’ labels now recommend against using amiodarone with those hepatitis C drugs.

An FDA statement issued March 24 described the bradycardia cases as “serious and life-threatening.” Gilead Sciences markets the ledipasvir and sofosbuvir combination as Harvoni and markets sofosbuvir as Sovaldi to treat chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.

Gilead issued a “Dear Health Care Provider” letter that provides further details of the cases. There have been nine postmarketing reports of symptomatic bradycardia in patients who were taking amiodarone with Harvoni; amiodarone with Sovaldi plus another hepatitis C antiviral drug, simeprevir (Olysio); or amiodarone with an investigational hepatitis C antiviral drug, daclatasvir.

Of those cases, six occurred with in the first 24 hours of starting treatment with the antivirals, and three cases occurred within the first 2-12 days after antiviral therapy was started. A pacemaker was needed in three cases, and one case was a fatal cardiac arrest.

In three cases, a “rechallenge with HCV treatment in the setting of continued amiodarone therapy resulted in recurrence of symptomatic bradycardia,” according to the Gilead letter.

The effect of coadministration on the blood levels of the antiviral drugs is not known, nor is the mechanism behind the cardiac effect.

The labeling of the fixed-dose combination of ledipasvir and sofosbuvir (Harvoni) now includes a section on “serious symptomatic bradycardia” when coadministered with amiodarone, and says that coadministration is not recommended. The label adds that if a patient on amiodarone or Harvoni has no other alternative than to take that combination, patients should be counseled about the bradycardia risk.

Cardiac monitoring is recommended for inpatients during the first 48 hours the patient is taking the drugs, “after which outpatient or self-monitoring of the heart rate should occur on a daily basis through at least the first 2 weeks of treatment.”

The label notes that amiodarone has a long half-life, so cardiac monitoring is still necessary if the patient discontinues amiodarone just before starting treatment with Harvoni. Similar labeling changes have been made to the Sovaldi label.

Adverse events associated with Harvoni or Sovaldi should be reported to the FDA’s MedWatch program at 800-332-1088 or www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/.

Novel HCV therapies found cost effective, with caveats

Two different statistical models found that novel therapies for chronic HCV infection, particularly the combination of sofosbuvir and ledipasvir, are cost effective in most patients, according to separate reports published online March 17 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

However, both groups of researchers cautioned that if these expensive agents are made available to the millions of eligible patients across the country, it would have an immense impact on health care costs for both public and private payers.

The novel therapies, which typically contain sofosbuvir in combination with ledipasvir, simeprevir, or daclatasvir, substantially reduce the length of treatment, achieve much higher rates of sustained viral response (SVR), and offer interferon-free alternatives for patients who can’t tolerate or don’t respond to standard interferon-based treatments. But it is unclear whether these benefits justify their profound expense, compared with current care. Both statistical models were developed to examine this issue, but from different perspectives.

In one study, funded primarily by the National Institutes of Health, investigators constructed a model that simulated 120 possible clinical courses of HCV-infected adults based on different ages and sexes, treatment histories, HCV genotypes, fibrosis scores, and interferon tolerances. For each of these patient profiles, they ran simulations in which patients received either “the old standard of care” (peginterferon and ribavirin, either with or without boceprevir and telaprevir) or sofosbuvir plus ledipasvir.

The average per-patient cost of standard care ranged from $15,000 to $71,000, depending on the patient profile, while that of sofosbuvir-ledipasvir ranged from $66,000 to $154,000, said Jagpreet Chhatwal, Ph.D., of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and his associates.

Compared with standard care, treating 10,000 patients with sofosbuvir-ledipasvir was projected to prevent 600 cases of decompensated cirrhosis, 310 cases of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), 60 liver transplantations, and 550 liver-related deaths, which would result in substantial cost savings. Also, compared with standard care, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of sofosbuvir-ledipasvir was $55,400 per additional quality-of-life-year (QALY) gained, which falls well within the accepted range for therapies for other medical conditions. Thus, the new therapy proved to be cost-effective for most HCV patients (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 March 17 [doi:10.7326/M14-1336]). But there was an important caveat: Many more patients would be eligible for the novel therapies than for the standard care, because the novel therapies are much more easily tolerated. With the addition of so many eligible patients, the resources needed to treat them “could be immense and unsustainable.” Compared with standard care, giving these novel HCV therapies to all eligible patients “would cost an additional $65 billion in the next 5 years,” which would not be counterbalanced by the estimated $16 billion saved by preventing cirrhosis, HCC, and transplantations.

Therefore, “despite the cost-effectiveness of [novel] HCV treatments, our analysis shows that it is unaffordable at the current price,” Dr. Chhatwal and his associates said.

In the other study, funded primarily by CVS Health, researchers developed a discrete-event simulation model of the natural history and progression of liver disease in treatment-naive patients, categorized by whether they were infected with HCV genotype 1, 2, or 3. Several possible treatment regimens were considered for each genotype, and the SVR rates they were projected to attain were derived from those reported in clinical trials, said Mehdi Najafzadeh, Ph.D., of the division of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his associates.

“From a societal perspective, the newly approved PEG-free regimen of sofosbuvir-ledipasvir for 12 weeks could be very cost-effective relative to usual care (costing $12,825/QALY gained) for patients with HCV genotype 1.” This treatment proved to be the optimal strategy in the greatest number of simulations involving genotype 1.

Similarly, for genotype 3 the combination of sofosbuvir plus ledipasvir plus ribavirin for 12 weeks cost $73,000/QALY gained, compared with usual care. This also represents “relatively good value.” However, for genotype 2 the most cost-effective novel therapy, sofosbuvir-ribavirin, was $110,168/QALY gained, which is not considered cost-effective, Dr. Najafzadeh and his associates said (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 March 17 [doi:10.7326;M14-1152]). Again, an important caveat to these findings was that, at their current prices, the cost of these drugs were not outweighed by the savings that accrued from preventing the complications of HCV. And “regardless of the cost-effectiveness of novel HCV treatments, there is considerable concern that their very high prices could substantially increase short-term overall drug spending for many public and private payers,” the investigators noted.

However, the fact that these regimens don’t reduce health care costs “is an exceptionally high bar” to hold them to – one that “is generally not expected when evaluating whether a new strategy represents good value for the money,” they added.

The recent development and widespread use of well-tolerated and highly efficacious direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) represent a paradigm shift in which the retail cost of treatment is now the most significant barrier to hepatitis C virus (HCV) eradication. While we have begun to learn the medical value of curing HCV in the context of the staggering burden of chronic liver disease, much less is known about the economic value of the cost of therapy. There has been swift public outcry over the $1,000 per pill price tag of sofosbuvir, and demand for the medications remains high as nearly all HCV-infected patients are now treatment eligible. Despite the high cost, these two studies collectively demonstrate a favorable incremental cost-effectiveness ratio per adjusted life-year relative to interferon-containing regimens in most patients with HCV: genotype 1, treatment-experienced, and cirrhotics.

These studies illustrate the paradox at the crux of the issue: How can the novel HCV therapies be both cost effective for most HCV patients but simultaneously unaffordable for payers? Although the price of achieving a sustained virologic response (SVR) is reduced with the DAA regimens, the cost of treating all infected patients in the United States could exceed $300 billion, which greatly outweighs the short-term cost of the annual HCV-related burden (approximately $6.5 billion [Hepatology 2013;57:2164-70]).

Treatment of other chronic illness such as HIV may incur greater costs but are distributed over a lifetime. Additionally, the current payers may not be the recipients of the downstream financial benefits of prevented liver-related outcomes. Ultimately, value depends on perspective; payers may balk at the price for the same cure that our patients consider invaluable.

Dr. J.P. Norvell is assistant professor of medicine, Emory University, Atlanta. He has been a consultant to Gilead Sciences.

The recent development and widespread use of well-tolerated and highly efficacious direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) represent a paradigm shift in which the retail cost of treatment is now the most significant barrier to hepatitis C virus (HCV) eradication. While we have begun to learn the medical value of curing HCV in the context of the staggering burden of chronic liver disease, much less is known about the economic value of the cost of therapy. There has been swift public outcry over the $1,000 per pill price tag of sofosbuvir, and demand for the medications remains high as nearly all HCV-infected patients are now treatment eligible. Despite the high cost, these two studies collectively demonstrate a favorable incremental cost-effectiveness ratio per adjusted life-year relative to interferon-containing regimens in most patients with HCV: genotype 1, treatment-experienced, and cirrhotics.

These studies illustrate the paradox at the crux of the issue: How can the novel HCV therapies be both cost effective for most HCV patients but simultaneously unaffordable for payers? Although the price of achieving a sustained virologic response (SVR) is reduced with the DAA regimens, the cost of treating all infected patients in the United States could exceed $300 billion, which greatly outweighs the short-term cost of the annual HCV-related burden (approximately $6.5 billion [Hepatology 2013;57:2164-70]).

Treatment of other chronic illness such as HIV may incur greater costs but are distributed over a lifetime. Additionally, the current payers may not be the recipients of the downstream financial benefits of prevented liver-related outcomes. Ultimately, value depends on perspective; payers may balk at the price for the same cure that our patients consider invaluable.

Dr. J.P. Norvell is assistant professor of medicine, Emory University, Atlanta. He has been a consultant to Gilead Sciences.

The recent development and widespread use of well-tolerated and highly efficacious direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) represent a paradigm shift in which the retail cost of treatment is now the most significant barrier to hepatitis C virus (HCV) eradication. While we have begun to learn the medical value of curing HCV in the context of the staggering burden of chronic liver disease, much less is known about the economic value of the cost of therapy. There has been swift public outcry over the $1,000 per pill price tag of sofosbuvir, and demand for the medications remains high as nearly all HCV-infected patients are now treatment eligible. Despite the high cost, these two studies collectively demonstrate a favorable incremental cost-effectiveness ratio per adjusted life-year relative to interferon-containing regimens in most patients with HCV: genotype 1, treatment-experienced, and cirrhotics.

These studies illustrate the paradox at the crux of the issue: How can the novel HCV therapies be both cost effective for most HCV patients but simultaneously unaffordable for payers? Although the price of achieving a sustained virologic response (SVR) is reduced with the DAA regimens, the cost of treating all infected patients in the United States could exceed $300 billion, which greatly outweighs the short-term cost of the annual HCV-related burden (approximately $6.5 billion [Hepatology 2013;57:2164-70]).

Treatment of other chronic illness such as HIV may incur greater costs but are distributed over a lifetime. Additionally, the current payers may not be the recipients of the downstream financial benefits of prevented liver-related outcomes. Ultimately, value depends on perspective; payers may balk at the price for the same cure that our patients consider invaluable.

Dr. J.P. Norvell is assistant professor of medicine, Emory University, Atlanta. He has been a consultant to Gilead Sciences.

Two different statistical models found that novel therapies for chronic HCV infection, particularly the combination of sofosbuvir and ledipasvir, are cost effective in most patients, according to separate reports published online March 17 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

However, both groups of researchers cautioned that if these expensive agents are made available to the millions of eligible patients across the country, it would have an immense impact on health care costs for both public and private payers.

The novel therapies, which typically contain sofosbuvir in combination with ledipasvir, simeprevir, or daclatasvir, substantially reduce the length of treatment, achieve much higher rates of sustained viral response (SVR), and offer interferon-free alternatives for patients who can’t tolerate or don’t respond to standard interferon-based treatments. But it is unclear whether these benefits justify their profound expense, compared with current care. Both statistical models were developed to examine this issue, but from different perspectives.

In one study, funded primarily by the National Institutes of Health, investigators constructed a model that simulated 120 possible clinical courses of HCV-infected adults based on different ages and sexes, treatment histories, HCV genotypes, fibrosis scores, and interferon tolerances. For each of these patient profiles, they ran simulations in which patients received either “the old standard of care” (peginterferon and ribavirin, either with or without boceprevir and telaprevir) or sofosbuvir plus ledipasvir.

The average per-patient cost of standard care ranged from $15,000 to $71,000, depending on the patient profile, while that of sofosbuvir-ledipasvir ranged from $66,000 to $154,000, said Jagpreet Chhatwal, Ph.D., of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and his associates.

Compared with standard care, treating 10,000 patients with sofosbuvir-ledipasvir was projected to prevent 600 cases of decompensated cirrhosis, 310 cases of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), 60 liver transplantations, and 550 liver-related deaths, which would result in substantial cost savings. Also, compared with standard care, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of sofosbuvir-ledipasvir was $55,400 per additional quality-of-life-year (QALY) gained, which falls well within the accepted range for therapies for other medical conditions. Thus, the new therapy proved to be cost-effective for most HCV patients (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 March 17 [doi:10.7326/M14-1336]). But there was an important caveat: Many more patients would be eligible for the novel therapies than for the standard care, because the novel therapies are much more easily tolerated. With the addition of so many eligible patients, the resources needed to treat them “could be immense and unsustainable.” Compared with standard care, giving these novel HCV therapies to all eligible patients “would cost an additional $65 billion in the next 5 years,” which would not be counterbalanced by the estimated $16 billion saved by preventing cirrhosis, HCC, and transplantations.

Therefore, “despite the cost-effectiveness of [novel] HCV treatments, our analysis shows that it is unaffordable at the current price,” Dr. Chhatwal and his associates said.

In the other study, funded primarily by CVS Health, researchers developed a discrete-event simulation model of the natural history and progression of liver disease in treatment-naive patients, categorized by whether they were infected with HCV genotype 1, 2, or 3. Several possible treatment regimens were considered for each genotype, and the SVR rates they were projected to attain were derived from those reported in clinical trials, said Mehdi Najafzadeh, Ph.D., of the division of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his associates.

“From a societal perspective, the newly approved PEG-free regimen of sofosbuvir-ledipasvir for 12 weeks could be very cost-effective relative to usual care (costing $12,825/QALY gained) for patients with HCV genotype 1.” This treatment proved to be the optimal strategy in the greatest number of simulations involving genotype 1.

Similarly, for genotype 3 the combination of sofosbuvir plus ledipasvir plus ribavirin for 12 weeks cost $73,000/QALY gained, compared with usual care. This also represents “relatively good value.” However, for genotype 2 the most cost-effective novel therapy, sofosbuvir-ribavirin, was $110,168/QALY gained, which is not considered cost-effective, Dr. Najafzadeh and his associates said (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 March 17 [doi:10.7326;M14-1152]). Again, an important caveat to these findings was that, at their current prices, the cost of these drugs were not outweighed by the savings that accrued from preventing the complications of HCV. And “regardless of the cost-effectiveness of novel HCV treatments, there is considerable concern that their very high prices could substantially increase short-term overall drug spending for many public and private payers,” the investigators noted.

However, the fact that these regimens don’t reduce health care costs “is an exceptionally high bar” to hold them to – one that “is generally not expected when evaluating whether a new strategy represents good value for the money,” they added.

Two different statistical models found that novel therapies for chronic HCV infection, particularly the combination of sofosbuvir and ledipasvir, are cost effective in most patients, according to separate reports published online March 17 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

However, both groups of researchers cautioned that if these expensive agents are made available to the millions of eligible patients across the country, it would have an immense impact on health care costs for both public and private payers.

The novel therapies, which typically contain sofosbuvir in combination with ledipasvir, simeprevir, or daclatasvir, substantially reduce the length of treatment, achieve much higher rates of sustained viral response (SVR), and offer interferon-free alternatives for patients who can’t tolerate or don’t respond to standard interferon-based treatments. But it is unclear whether these benefits justify their profound expense, compared with current care. Both statistical models were developed to examine this issue, but from different perspectives.

In one study, funded primarily by the National Institutes of Health, investigators constructed a model that simulated 120 possible clinical courses of HCV-infected adults based on different ages and sexes, treatment histories, HCV genotypes, fibrosis scores, and interferon tolerances. For each of these patient profiles, they ran simulations in which patients received either “the old standard of care” (peginterferon and ribavirin, either with or without boceprevir and telaprevir) or sofosbuvir plus ledipasvir.

The average per-patient cost of standard care ranged from $15,000 to $71,000, depending on the patient profile, while that of sofosbuvir-ledipasvir ranged from $66,000 to $154,000, said Jagpreet Chhatwal, Ph.D., of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and his associates.

Compared with standard care, treating 10,000 patients with sofosbuvir-ledipasvir was projected to prevent 600 cases of decompensated cirrhosis, 310 cases of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), 60 liver transplantations, and 550 liver-related deaths, which would result in substantial cost savings. Also, compared with standard care, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of sofosbuvir-ledipasvir was $55,400 per additional quality-of-life-year (QALY) gained, which falls well within the accepted range for therapies for other medical conditions. Thus, the new therapy proved to be cost-effective for most HCV patients (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 March 17 [doi:10.7326/M14-1336]). But there was an important caveat: Many more patients would be eligible for the novel therapies than for the standard care, because the novel therapies are much more easily tolerated. With the addition of so many eligible patients, the resources needed to treat them “could be immense and unsustainable.” Compared with standard care, giving these novel HCV therapies to all eligible patients “would cost an additional $65 billion in the next 5 years,” which would not be counterbalanced by the estimated $16 billion saved by preventing cirrhosis, HCC, and transplantations.

Therefore, “despite the cost-effectiveness of [novel] HCV treatments, our analysis shows that it is unaffordable at the current price,” Dr. Chhatwal and his associates said.

In the other study, funded primarily by CVS Health, researchers developed a discrete-event simulation model of the natural history and progression of liver disease in treatment-naive patients, categorized by whether they were infected with HCV genotype 1, 2, or 3. Several possible treatment regimens were considered for each genotype, and the SVR rates they were projected to attain were derived from those reported in clinical trials, said Mehdi Najafzadeh, Ph.D., of the division of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his associates.

“From a societal perspective, the newly approved PEG-free regimen of sofosbuvir-ledipasvir for 12 weeks could be very cost-effective relative to usual care (costing $12,825/QALY gained) for patients with HCV genotype 1.” This treatment proved to be the optimal strategy in the greatest number of simulations involving genotype 1.

Similarly, for genotype 3 the combination of sofosbuvir plus ledipasvir plus ribavirin for 12 weeks cost $73,000/QALY gained, compared with usual care. This also represents “relatively good value.” However, for genotype 2 the most cost-effective novel therapy, sofosbuvir-ribavirin, was $110,168/QALY gained, which is not considered cost-effective, Dr. Najafzadeh and his associates said (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 March 17 [doi:10.7326;M14-1152]). Again, an important caveat to these findings was that, at their current prices, the cost of these drugs were not outweighed by the savings that accrued from preventing the complications of HCV. And “regardless of the cost-effectiveness of novel HCV treatments, there is considerable concern that their very high prices could substantially increase short-term overall drug spending for many public and private payers,” the investigators noted.

However, the fact that these regimens don’t reduce health care costs “is an exceptionally high bar” to hold them to – one that “is generally not expected when evaluating whether a new strategy represents good value for the money,” they added.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Two separate computerized statistical models found that new HCV therapies are cost effective in most cases, with important caveats.

Major finding: Compared with standard care, treating 10,000 patients with sofosbuvir-ledipasvir was projected to prevent 600 cases of decompensated cirrhosis, 310 cases of hepatocellular carcinoma, 60 liver transplantations, and 550 liver-related deaths.

Data source: A microsimulation model of the cost-effectiveness of various HCV therapies, and a discrete-event simulation model of cost-effectiveness from a societal standpoint.

Disclosures: Dr. Chhatwal’s study was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety. Dr. Najafzadeh’s study was supported by an unrestricted grant from CVS Health to Brigham and Women’s Hospital and by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research fellowship. Both research groups’ financial disclosures are available at www.annals.org.

ASCEND trial to test HCV treatment in primary care setting

The new ASCEND trial will examine whether primary care physicians can use a new antiviral therapy to treat hepatitis C virus as effectively as specialists do, according to a press release from the National Institutes of Health.

While past treatments for HCV were long-term, complex, and generally required a specialist physician, new drug developments may not require such in-depth treatment and could be handled by a primary care physician. The ASCEND study will involve 600 patients in the Washington, D.C. area, with 350 patients continuing their normal treatment with a specialist, and 250 patients receiving their treatment at a primary care location. Both groups will receive the same medication.

“The recent advent of direct-acting antiviral medications has offered promising new treatment options for people who are chronically infected with hepatitis C,” Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, said. “The ASCEND study will help determine whether these medications are similarly effective when administered in an urban, community-based setting.”

Find the full press release on the NIH website.

The new ASCEND trial will examine whether primary care physicians can use a new antiviral therapy to treat hepatitis C virus as effectively as specialists do, according to a press release from the National Institutes of Health.

While past treatments for HCV were long-term, complex, and generally required a specialist physician, new drug developments may not require such in-depth treatment and could be handled by a primary care physician. The ASCEND study will involve 600 patients in the Washington, D.C. area, with 350 patients continuing their normal treatment with a specialist, and 250 patients receiving their treatment at a primary care location. Both groups will receive the same medication.

“The recent advent of direct-acting antiviral medications has offered promising new treatment options for people who are chronically infected with hepatitis C,” Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, said. “The ASCEND study will help determine whether these medications are similarly effective when administered in an urban, community-based setting.”

Find the full press release on the NIH website.

The new ASCEND trial will examine whether primary care physicians can use a new antiviral therapy to treat hepatitis C virus as effectively as specialists do, according to a press release from the National Institutes of Health.

While past treatments for HCV were long-term, complex, and generally required a specialist physician, new drug developments may not require such in-depth treatment and could be handled by a primary care physician. The ASCEND study will involve 600 patients in the Washington, D.C. area, with 350 patients continuing their normal treatment with a specialist, and 250 patients receiving their treatment at a primary care location. Both groups will receive the same medication.

“The recent advent of direct-acting antiviral medications has offered promising new treatment options for people who are chronically infected with hepatitis C,” Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, said. “The ASCEND study will help determine whether these medications are similarly effective when administered in an urban, community-based setting.”

Find the full press release on the NIH website.

Case studies highlight HCV health care transmission risk

Hospitals should carefully monitor equipment for hepatitis C virus contamination and the possibility of health care transmission, according to a Feb. 27 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC report focuses on two specific cases of health care–transmitted HCV. In 2010, a patient without HCV in a New Jersey hospital was treated by an anesthesiologist who had immediately beforehand treated someone with HCV. Despite the single commonality between the two patients, patient A contracted HCV.

In 2011, a patient in Wisconsin with a history of diabetes and chronic renal disease was diagnosed with HCV-4, a subtype of the disease that is rare in that part of the world. The infection occurred in 2009, when this patient had a kidney transplant at the same time as a patient with HCV-4 also was having a kidney transplant. The two transplants shared a surgeon, but the source of infection was likely a perfusion machine where an HCV-positive kidney and an HCV-negative kidney were both stored without cleaning the machine.

“These cases illustrate the importance of partnerships and communication between public health and health care professionals to ensure that basic infection control and injection safety practices are optimized wherever health care is delivered,” the CDC investigators concluded.

Read the full report in the MMWR (2015;64:165-70).

Hospitals should carefully monitor equipment for hepatitis C virus contamination and the possibility of health care transmission, according to a Feb. 27 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC report focuses on two specific cases of health care–transmitted HCV. In 2010, a patient without HCV in a New Jersey hospital was treated by an anesthesiologist who had immediately beforehand treated someone with HCV. Despite the single commonality between the two patients, patient A contracted HCV.

In 2011, a patient in Wisconsin with a history of diabetes and chronic renal disease was diagnosed with HCV-4, a subtype of the disease that is rare in that part of the world. The infection occurred in 2009, when this patient had a kidney transplant at the same time as a patient with HCV-4 also was having a kidney transplant. The two transplants shared a surgeon, but the source of infection was likely a perfusion machine where an HCV-positive kidney and an HCV-negative kidney were both stored without cleaning the machine.

“These cases illustrate the importance of partnerships and communication between public health and health care professionals to ensure that basic infection control and injection safety practices are optimized wherever health care is delivered,” the CDC investigators concluded.

Read the full report in the MMWR (2015;64:165-70).

Hospitals should carefully monitor equipment for hepatitis C virus contamination and the possibility of health care transmission, according to a Feb. 27 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC report focuses on two specific cases of health care–transmitted HCV. In 2010, a patient without HCV in a New Jersey hospital was treated by an anesthesiologist who had immediately beforehand treated someone with HCV. Despite the single commonality between the two patients, patient A contracted HCV.

In 2011, a patient in Wisconsin with a history of diabetes and chronic renal disease was diagnosed with HCV-4, a subtype of the disease that is rare in that part of the world. The infection occurred in 2009, when this patient had a kidney transplant at the same time as a patient with HCV-4 also was having a kidney transplant. The two transplants shared a surgeon, but the source of infection was likely a perfusion machine where an HCV-positive kidney and an HCV-negative kidney were both stored without cleaning the machine.

“These cases illustrate the importance of partnerships and communication between public health and health care professionals to ensure that basic infection control and injection safety practices are optimized wherever health care is delivered,” the CDC investigators concluded.

Read the full report in the MMWR (2015;64:165-70).

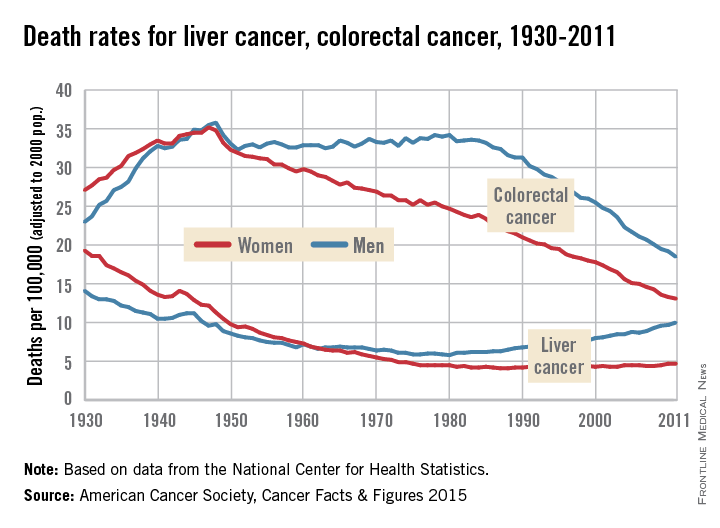

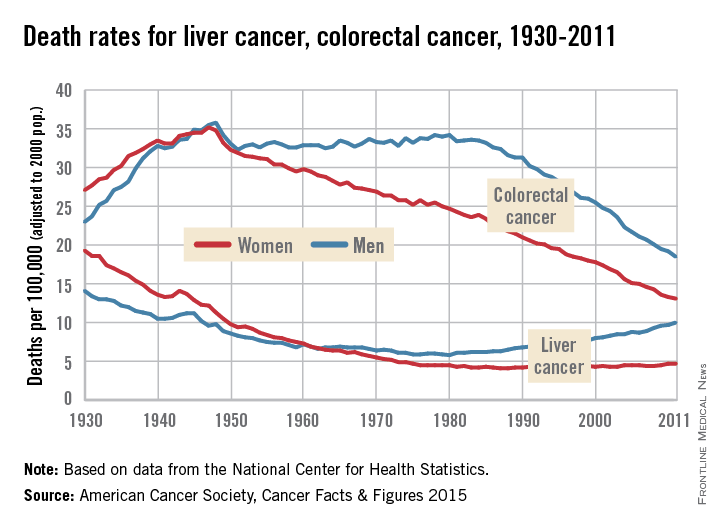

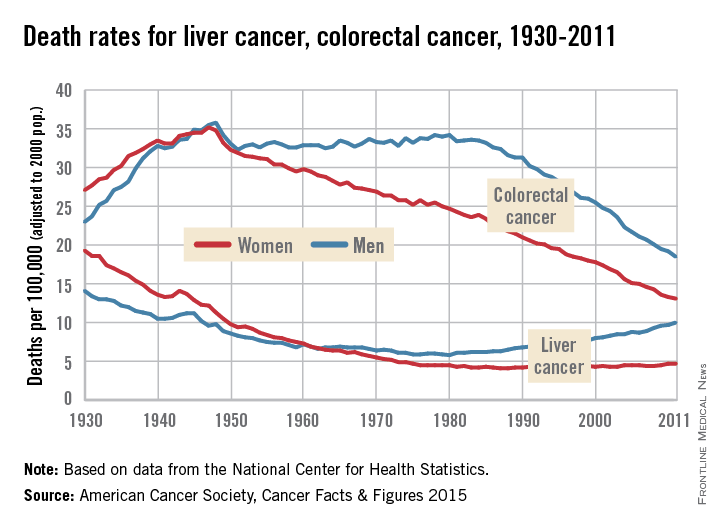

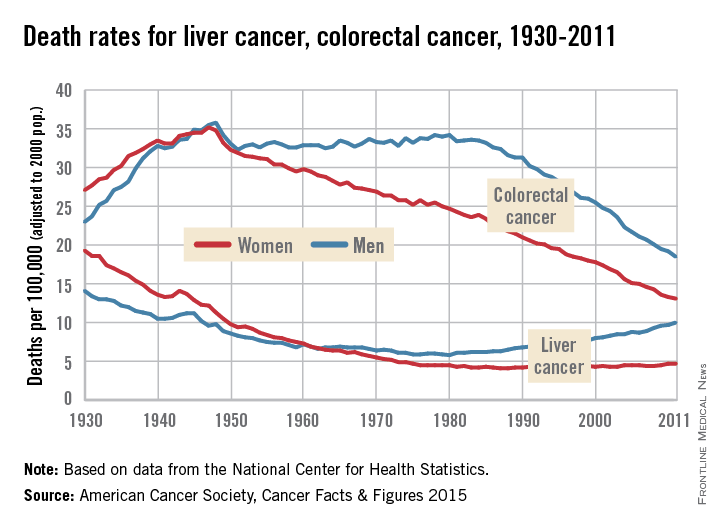

Death rates rising for liver cancer, falling for colorectal cancer

Death rates for liver cancer have been rising for some time among both men and women, while rates of colon and rectal cancer continue to decline from historic highs in the 1940s, the American Cancer Society reported.

In 2011, the death rate for liver cancer was 10/100,000 population (age-adjusted to the 2000 U.S. standard population) for men and 4.7/100,000 for women. The death rate for men reached its all-time low in 1980, when it was 5.8; for women, the low was 4.1 in 1987-1988. From 2007 to 2011, the overall death rate rose by 2.5% per year, according to the ACS.