User login

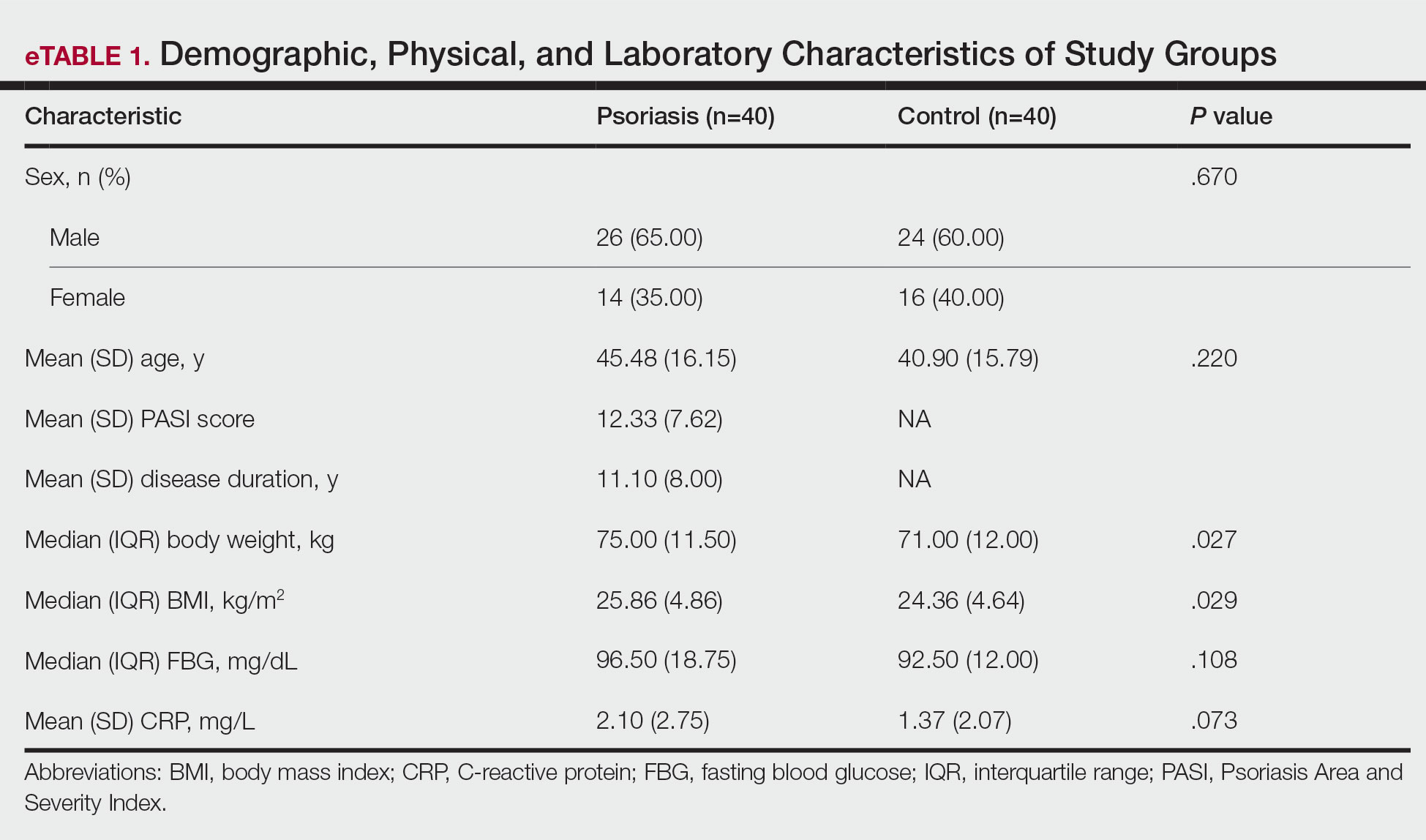

Impact of a Museum-Based Retreat on the Clinical Skills and Well-Being of Dermatology Residents and Faculty

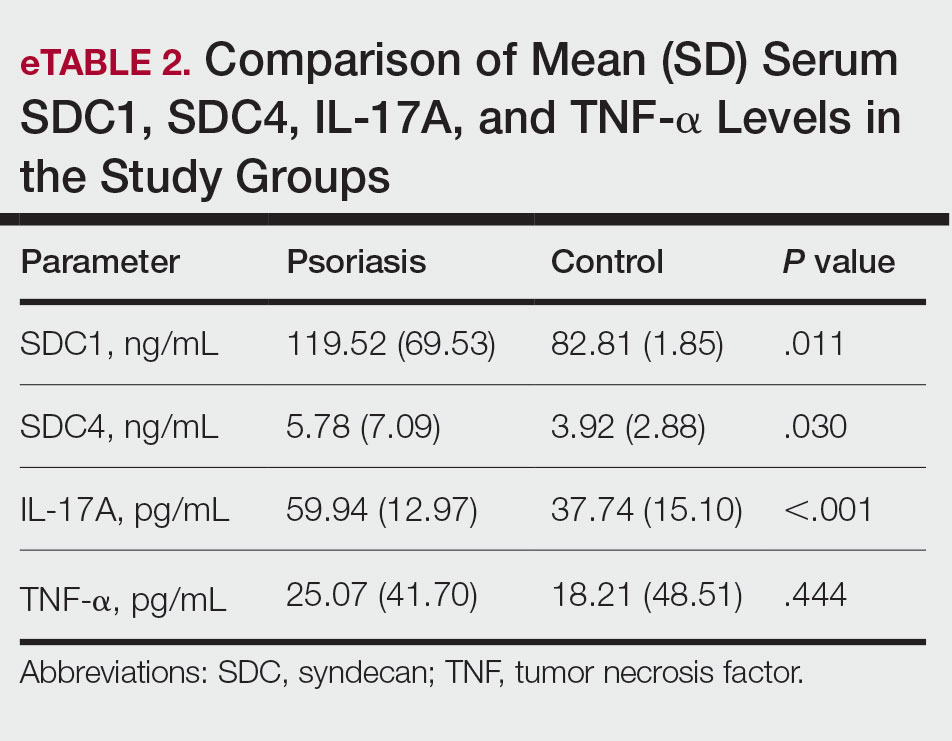

Impact of a Museum-Based Retreat on the Clinical Skills and Well-Being of Dermatology Residents and Faculty

Prior research has demonstrated that museum-based programming decreases resident burnout and depersonalization.1 A partnership between the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the Harvard Combined Dermatology Residency Program was well received by residents and resulted in improvement of their observational skills.2 The impact of museum-based programming on the clinical practice skills and well-being of Duke dermatology residents and faculty has not been previously assessed.

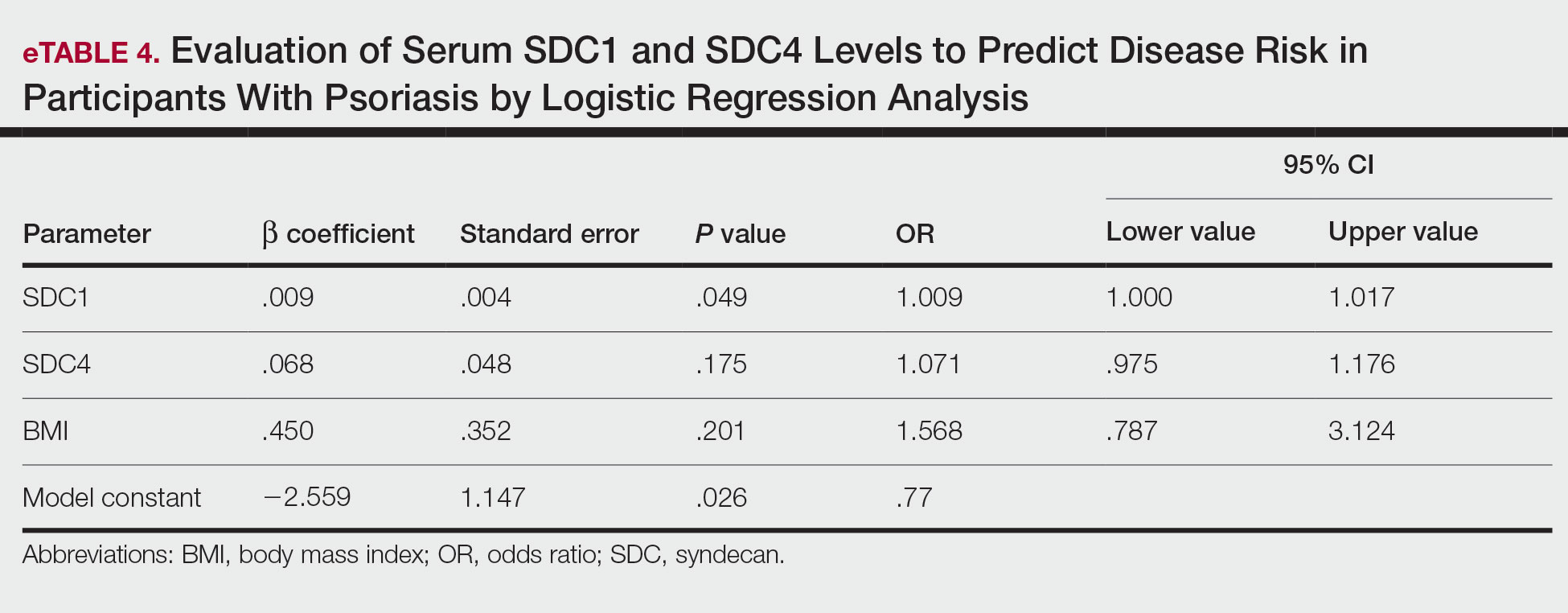

In this study, our objective was to evaluate the impact of a 3-part museum-based arts retreat on arts appreciation, clinical practice skills, and well-being among dermatology resident and faculty participants. Surveys administered before and after the retreat were used to assess the value that participants attributed to the arts in various areas of clinical practice.

Methods

A 3-part museum-based retreat held on February 7, 2024, was developed with a Nasher Museum of Art (Durham, North Carolina) curator (E.R.). Part 1 was a personal response tour in which 15 residents and 3 faculty members were given individualized prompts and asked to identify an art piece in the museum that encapsulated their response; they then were asked to explain to the group why they chose that particular piece. Participants were given 10 minutes to explore the museum galleries to choose their piece, followed by 15 minutes to share their selected work in groups of 3 to 4.

Part 2 encompassed visual-thinking strategies, a research-based method that uses art to teach visual literacy, thinking, and communication skills.2 Using this method, facilitators follow a specific protocol to guide participants in the exploration of an art piece through sharing observations and interpretations.4 Participants were divided into 2 groups led by trained museum educators (including E.R.) to analyze and ascribe meaning to a chosen art piece. Three questions were asked: What’s going on in this picture? What do you see that makes you say that? What else can we find?

Part 3 involved back-to-back drawing, in which participants were paired up and tasked with recreating an art piece in the museum based solely on their partner’s verbal description. In each pair, both participants took turns as the describer and the drawer.

After each part of the retreat, 5 to 10 minutes were dedicated to debriefing in small groups about how each activity may connect to the role of a clinician. A total of 15 participants completed pre- and post-retreat surveys to assess the value they attributed to the arts and identify in which aspects of clinical practice they believe the arts play a role.

Results

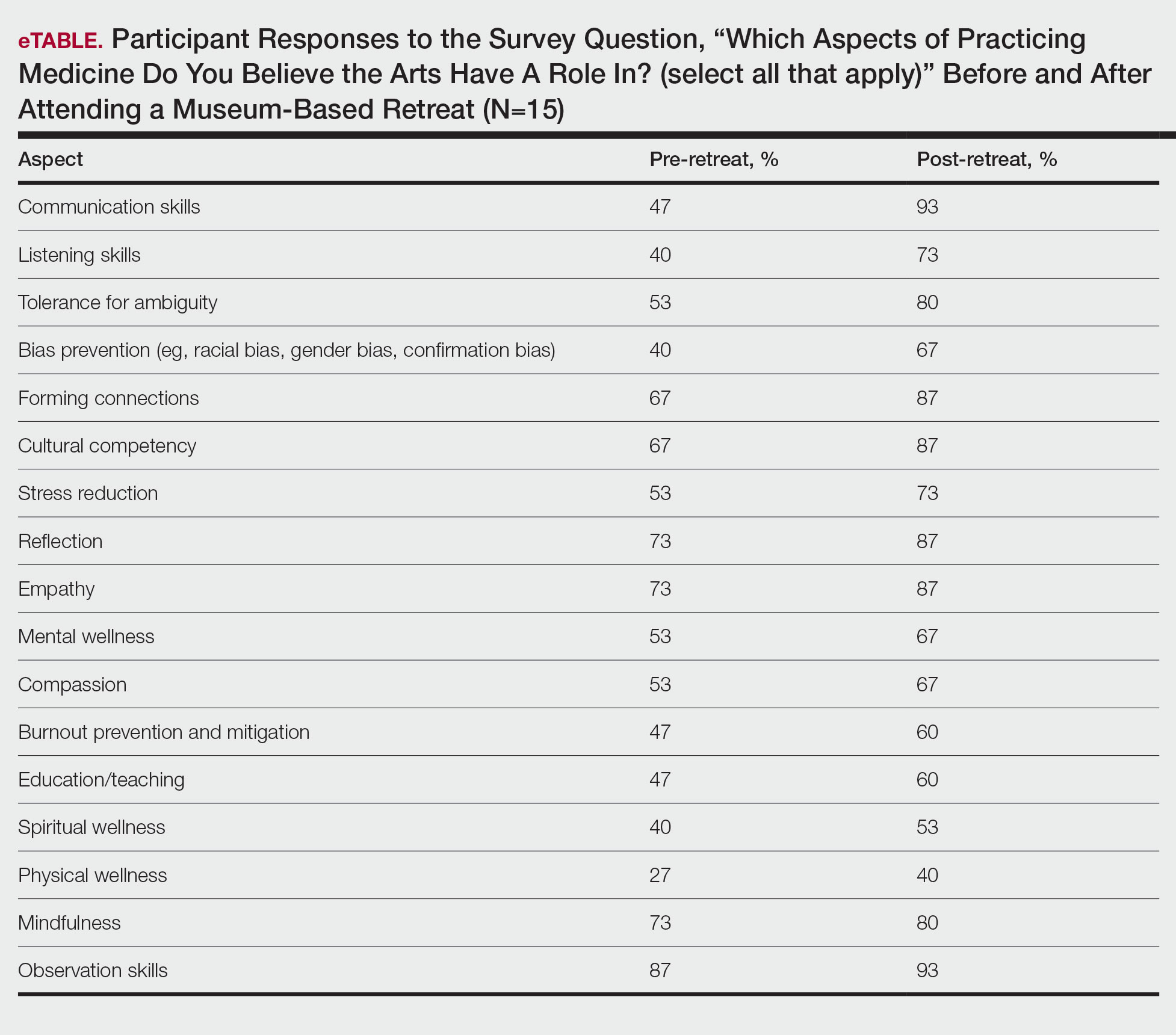

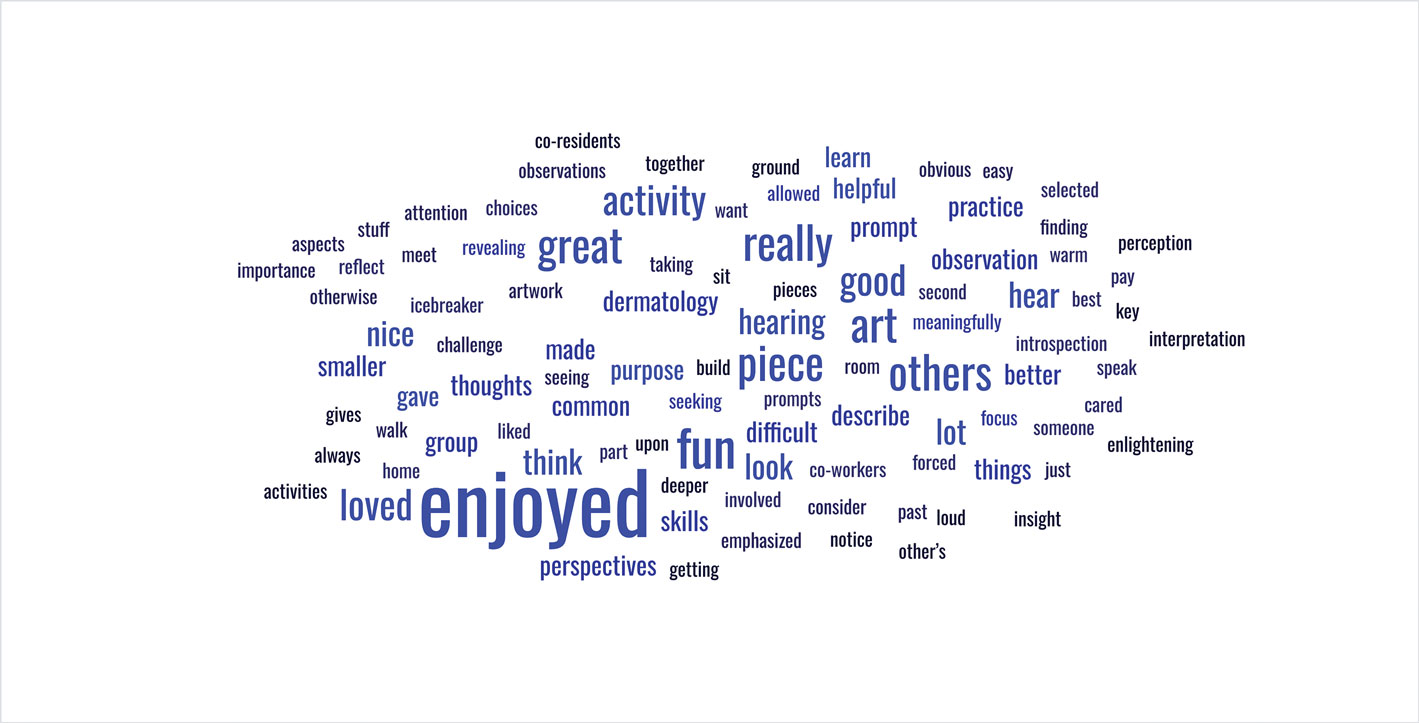

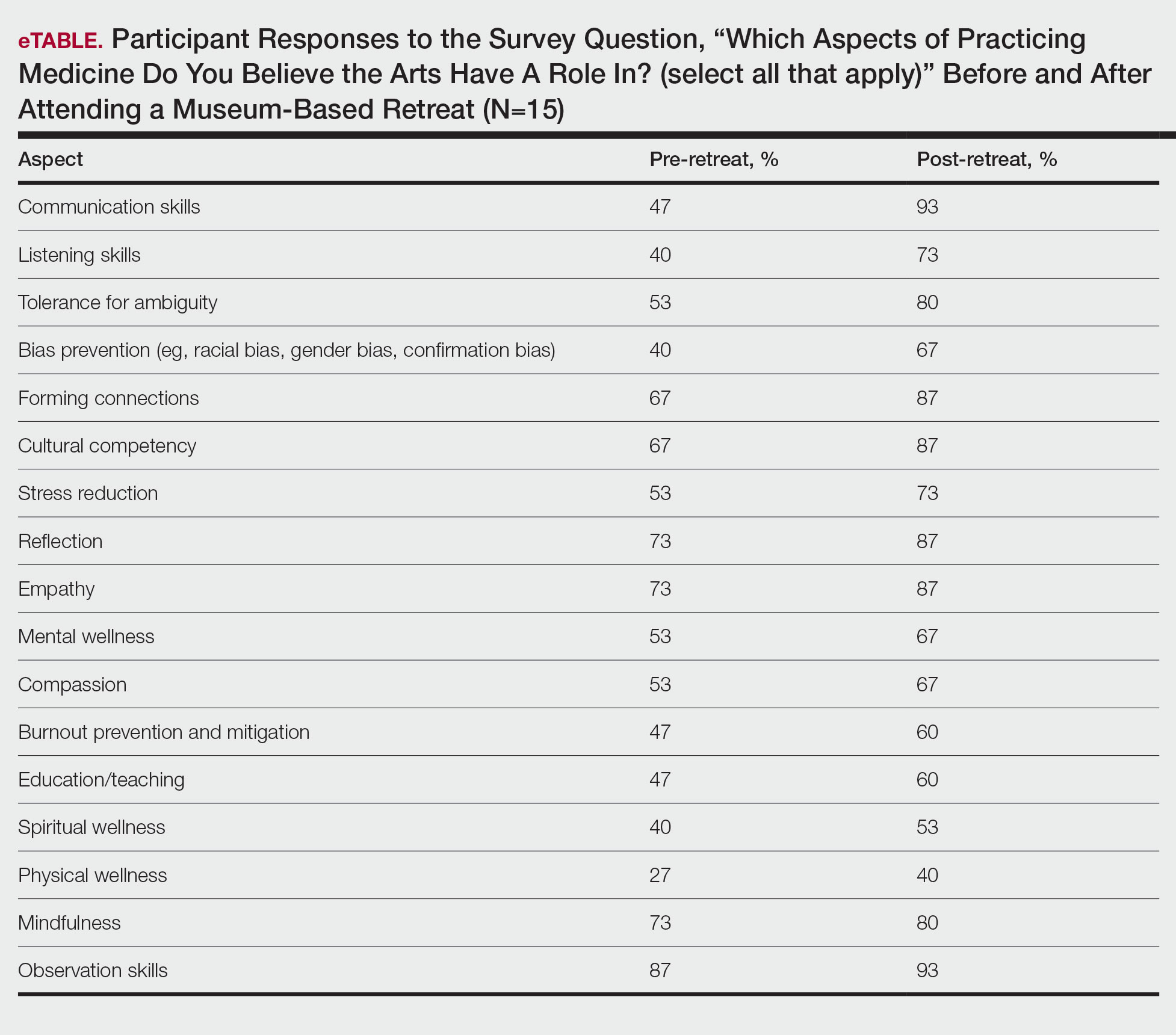

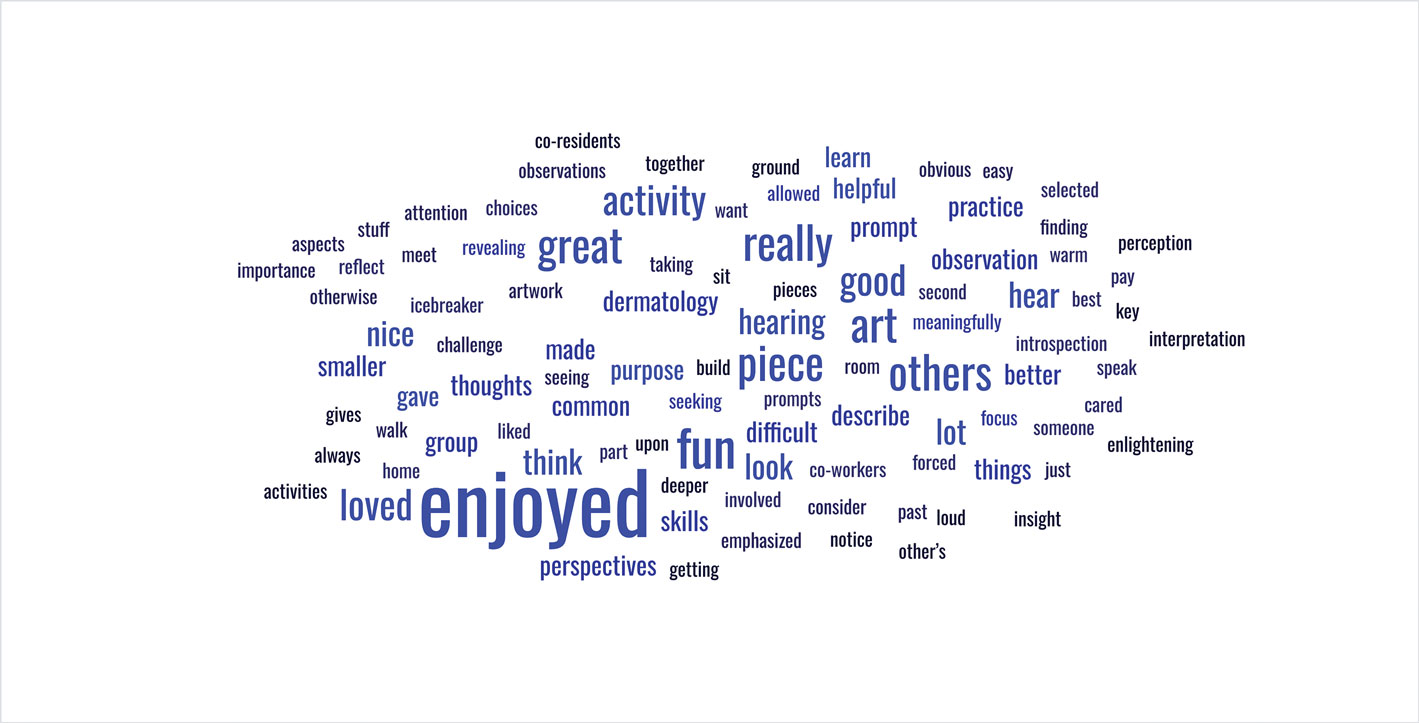

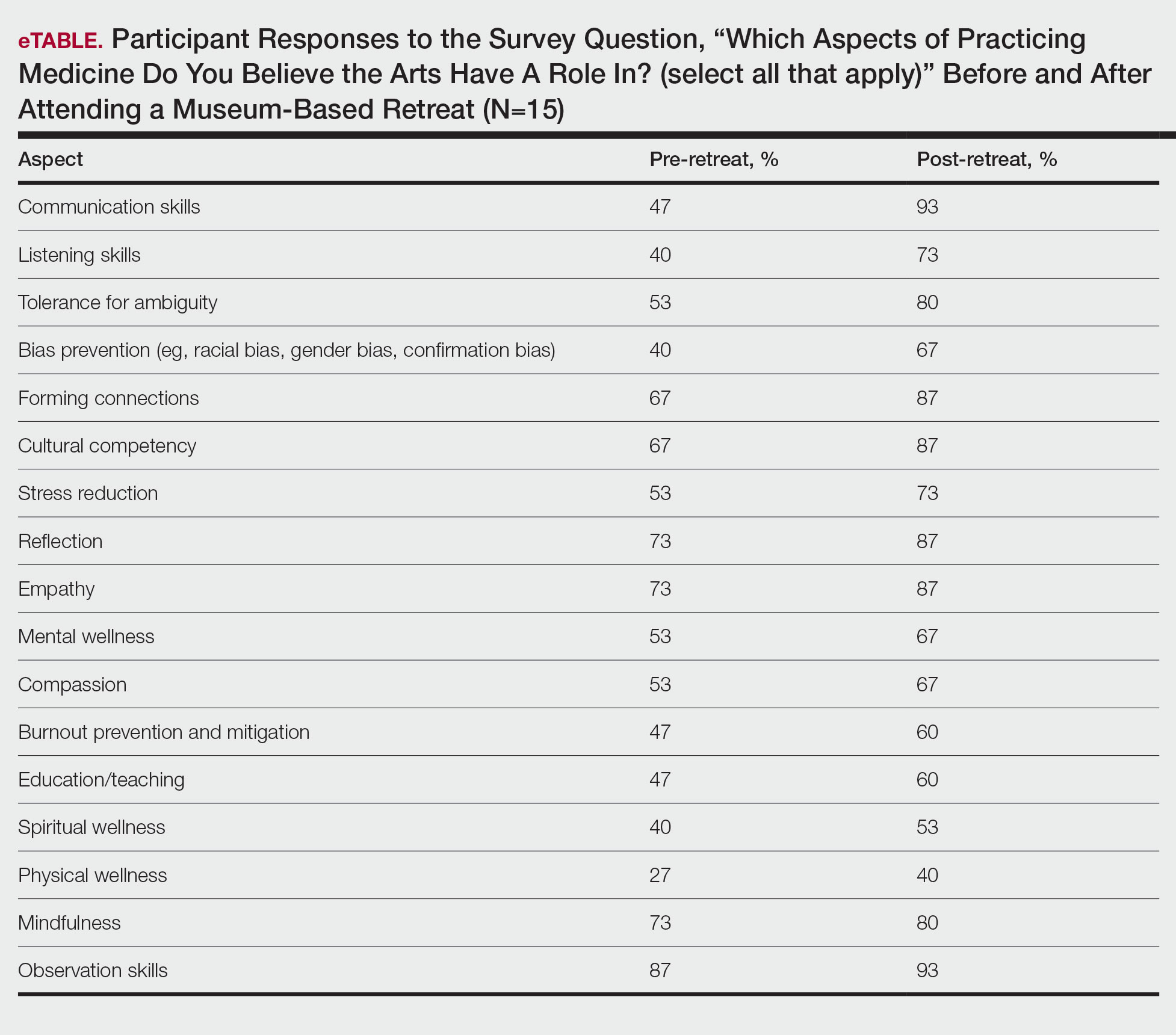

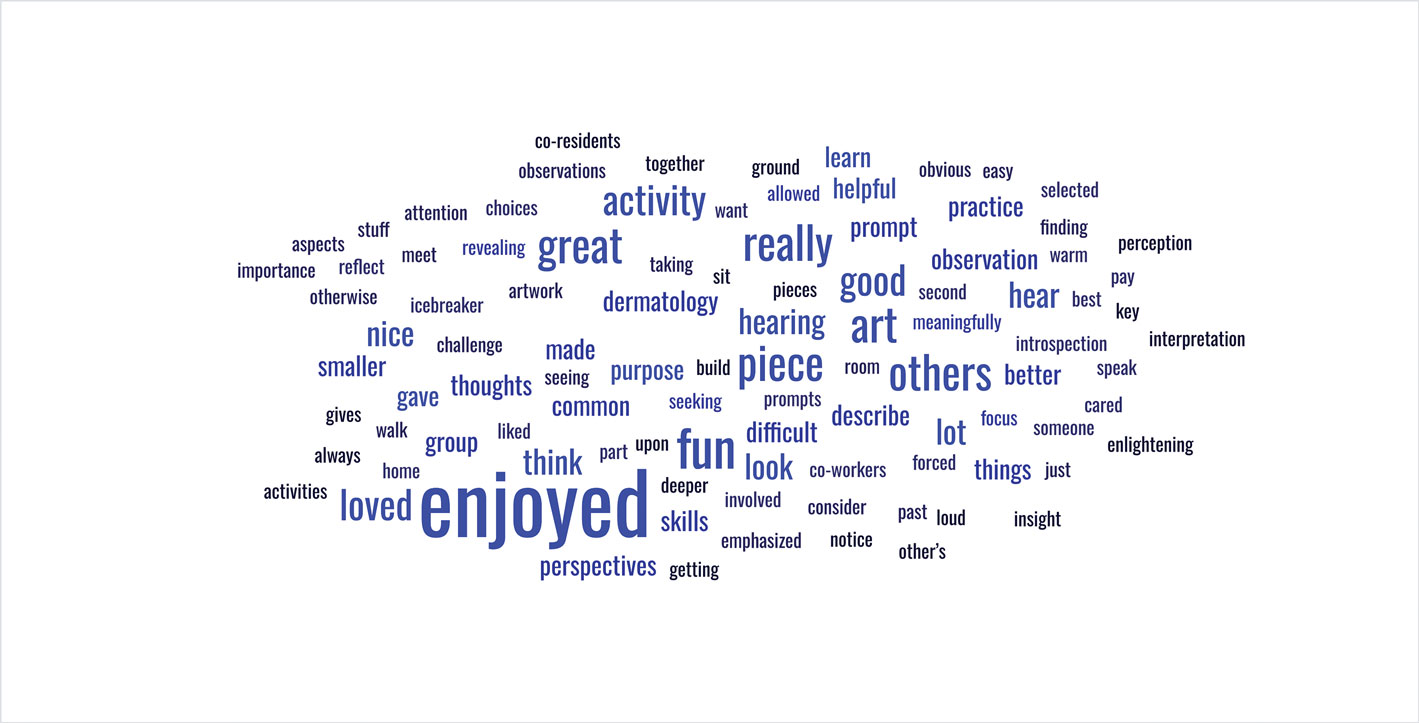

Seventy-three percent of participants (11/15) found the museum-based retreat “extremely useful” or “very useful.” There was a 20% increase in those who attributed at least moderate value to the arts as a clinician after compared to before the retreat (13/15 [87%] vs 8/15 [53%]), and 100% of the participants desired to participate in future arts-based programming. Following the retreat, a greater percentage of participants believed the arts have a role in the following aspects of clinical practice: education, observation, listening, communication, empathy, compassion, forming connections, cultural sensitivity, tolerance for ambiguity, reflection, mindfulness, stress reduction, preventing burnout, bias prevention, mental wellness, spiritual wellness, and physical wellness (eTable). Qualitative feedback compiled from the participants’ responses to survey questions following the retreat about their thoughts on each activity and overall feedback was used to create a word cloud (eFigure).

Comment

The importance of arts and humanities integration into medical education previously has been described.5 Our survey results suggest that museum-based programming increases dermatology resident and faculty appreciation for the arts and encourages participation in future arts-based programming. Our results also demonstrate that arts-based programming positively impacts important resident competencies in the practice of medicine including tolerance for ambiguity, bias prevention, and cultural competency, and that the incorporation of arts-based programming can enhance residents’ well-being (physical, mental, and spiritual) as well as their ability to be better clinicians by addressing skills in communication, listening, and observation. The structure of our 3-part museum-based retreat offers practical implementation strategies for integrating the humanities into dermatology residency curricula and easily can be modified to meet the needs of different dermatology residency programs.

Orr AR, Moghbeli N, Swain A, et al. The Fostering Resilience through Art in Medical Education (FRAME) workshop: a partnership with the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:361-369. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S194575

Zimmermann C, Huang JT, Buzney EA. Refining the eye: dermatology and visual literacy. J Museum Ed. 2016;41:116-122.

Yenawine P. Visual Thinking Strategies: Using Art to Deepen Learning Across School Disciplines. Harvard Education Press; 2013.

Hailey D, Miller A, Yenawine P. Understanding visual literacy: the visual thinking strategies approach. In: Baylen DM, D’Alba A. Essentials of Teaching and Integrating Visual and Media Literacy: Visualizing Learning. Springer Cham; 2015:49-73. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-05837-5

Howley L, Gaufberg E, King BE. The Fundamental Role of the Arts and Humanities in Medical Education. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2020. Accessed December 18, 2025. https://store.aamc.org/the-fundamental-role-of-the-arts-and-humanities-in-medical-education.html

Prior research has demonstrated that museum-based programming decreases resident burnout and depersonalization.1 A partnership between the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the Harvard Combined Dermatology Residency Program was well received by residents and resulted in improvement of their observational skills.2 The impact of museum-based programming on the clinical practice skills and well-being of Duke dermatology residents and faculty has not been previously assessed.

In this study, our objective was to evaluate the impact of a 3-part museum-based arts retreat on arts appreciation, clinical practice skills, and well-being among dermatology resident and faculty participants. Surveys administered before and after the retreat were used to assess the value that participants attributed to the arts in various areas of clinical practice.

Methods

A 3-part museum-based retreat held on February 7, 2024, was developed with a Nasher Museum of Art (Durham, North Carolina) curator (E.R.). Part 1 was a personal response tour in which 15 residents and 3 faculty members were given individualized prompts and asked to identify an art piece in the museum that encapsulated their response; they then were asked to explain to the group why they chose that particular piece. Participants were given 10 minutes to explore the museum galleries to choose their piece, followed by 15 minutes to share their selected work in groups of 3 to 4.

Part 2 encompassed visual-thinking strategies, a research-based method that uses art to teach visual literacy, thinking, and communication skills.2 Using this method, facilitators follow a specific protocol to guide participants in the exploration of an art piece through sharing observations and interpretations.4 Participants were divided into 2 groups led by trained museum educators (including E.R.) to analyze and ascribe meaning to a chosen art piece. Three questions were asked: What’s going on in this picture? What do you see that makes you say that? What else can we find?

Part 3 involved back-to-back drawing, in which participants were paired up and tasked with recreating an art piece in the museum based solely on their partner’s verbal description. In each pair, both participants took turns as the describer and the drawer.

After each part of the retreat, 5 to 10 minutes were dedicated to debriefing in small groups about how each activity may connect to the role of a clinician. A total of 15 participants completed pre- and post-retreat surveys to assess the value they attributed to the arts and identify in which aspects of clinical practice they believe the arts play a role.

Results

Seventy-three percent of participants (11/15) found the museum-based retreat “extremely useful” or “very useful.” There was a 20% increase in those who attributed at least moderate value to the arts as a clinician after compared to before the retreat (13/15 [87%] vs 8/15 [53%]), and 100% of the participants desired to participate in future arts-based programming. Following the retreat, a greater percentage of participants believed the arts have a role in the following aspects of clinical practice: education, observation, listening, communication, empathy, compassion, forming connections, cultural sensitivity, tolerance for ambiguity, reflection, mindfulness, stress reduction, preventing burnout, bias prevention, mental wellness, spiritual wellness, and physical wellness (eTable). Qualitative feedback compiled from the participants’ responses to survey questions following the retreat about their thoughts on each activity and overall feedback was used to create a word cloud (eFigure).

Comment

The importance of arts and humanities integration into medical education previously has been described.5 Our survey results suggest that museum-based programming increases dermatology resident and faculty appreciation for the arts and encourages participation in future arts-based programming. Our results also demonstrate that arts-based programming positively impacts important resident competencies in the practice of medicine including tolerance for ambiguity, bias prevention, and cultural competency, and that the incorporation of arts-based programming can enhance residents’ well-being (physical, mental, and spiritual) as well as their ability to be better clinicians by addressing skills in communication, listening, and observation. The structure of our 3-part museum-based retreat offers practical implementation strategies for integrating the humanities into dermatology residency curricula and easily can be modified to meet the needs of different dermatology residency programs.

Prior research has demonstrated that museum-based programming decreases resident burnout and depersonalization.1 A partnership between the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the Harvard Combined Dermatology Residency Program was well received by residents and resulted in improvement of their observational skills.2 The impact of museum-based programming on the clinical practice skills and well-being of Duke dermatology residents and faculty has not been previously assessed.

In this study, our objective was to evaluate the impact of a 3-part museum-based arts retreat on arts appreciation, clinical practice skills, and well-being among dermatology resident and faculty participants. Surveys administered before and after the retreat were used to assess the value that participants attributed to the arts in various areas of clinical practice.

Methods

A 3-part museum-based retreat held on February 7, 2024, was developed with a Nasher Museum of Art (Durham, North Carolina) curator (E.R.). Part 1 was a personal response tour in which 15 residents and 3 faculty members were given individualized prompts and asked to identify an art piece in the museum that encapsulated their response; they then were asked to explain to the group why they chose that particular piece. Participants were given 10 minutes to explore the museum galleries to choose their piece, followed by 15 minutes to share their selected work in groups of 3 to 4.

Part 2 encompassed visual-thinking strategies, a research-based method that uses art to teach visual literacy, thinking, and communication skills.2 Using this method, facilitators follow a specific protocol to guide participants in the exploration of an art piece through sharing observations and interpretations.4 Participants were divided into 2 groups led by trained museum educators (including E.R.) to analyze and ascribe meaning to a chosen art piece. Three questions were asked: What’s going on in this picture? What do you see that makes you say that? What else can we find?

Part 3 involved back-to-back drawing, in which participants were paired up and tasked with recreating an art piece in the museum based solely on their partner’s verbal description. In each pair, both participants took turns as the describer and the drawer.

After each part of the retreat, 5 to 10 minutes were dedicated to debriefing in small groups about how each activity may connect to the role of a clinician. A total of 15 participants completed pre- and post-retreat surveys to assess the value they attributed to the arts and identify in which aspects of clinical practice they believe the arts play a role.

Results

Seventy-three percent of participants (11/15) found the museum-based retreat “extremely useful” or “very useful.” There was a 20% increase in those who attributed at least moderate value to the arts as a clinician after compared to before the retreat (13/15 [87%] vs 8/15 [53%]), and 100% of the participants desired to participate in future arts-based programming. Following the retreat, a greater percentage of participants believed the arts have a role in the following aspects of clinical practice: education, observation, listening, communication, empathy, compassion, forming connections, cultural sensitivity, tolerance for ambiguity, reflection, mindfulness, stress reduction, preventing burnout, bias prevention, mental wellness, spiritual wellness, and physical wellness (eTable). Qualitative feedback compiled from the participants’ responses to survey questions following the retreat about their thoughts on each activity and overall feedback was used to create a word cloud (eFigure).

Comment

The importance of arts and humanities integration into medical education previously has been described.5 Our survey results suggest that museum-based programming increases dermatology resident and faculty appreciation for the arts and encourages participation in future arts-based programming. Our results also demonstrate that arts-based programming positively impacts important resident competencies in the practice of medicine including tolerance for ambiguity, bias prevention, and cultural competency, and that the incorporation of arts-based programming can enhance residents’ well-being (physical, mental, and spiritual) as well as their ability to be better clinicians by addressing skills in communication, listening, and observation. The structure of our 3-part museum-based retreat offers practical implementation strategies for integrating the humanities into dermatology residency curricula and easily can be modified to meet the needs of different dermatology residency programs.

Orr AR, Moghbeli N, Swain A, et al. The Fostering Resilience through Art in Medical Education (FRAME) workshop: a partnership with the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:361-369. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S194575

Zimmermann C, Huang JT, Buzney EA. Refining the eye: dermatology and visual literacy. J Museum Ed. 2016;41:116-122.

Yenawine P. Visual Thinking Strategies: Using Art to Deepen Learning Across School Disciplines. Harvard Education Press; 2013.

Hailey D, Miller A, Yenawine P. Understanding visual literacy: the visual thinking strategies approach. In: Baylen DM, D’Alba A. Essentials of Teaching and Integrating Visual and Media Literacy: Visualizing Learning. Springer Cham; 2015:49-73. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-05837-5

Howley L, Gaufberg E, King BE. The Fundamental Role of the Arts and Humanities in Medical Education. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2020. Accessed December 18, 2025. https://store.aamc.org/the-fundamental-role-of-the-arts-and-humanities-in-medical-education.html

Orr AR, Moghbeli N, Swain A, et al. The Fostering Resilience through Art in Medical Education (FRAME) workshop: a partnership with the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:361-369. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S194575

Zimmermann C, Huang JT, Buzney EA. Refining the eye: dermatology and visual literacy. J Museum Ed. 2016;41:116-122.

Yenawine P. Visual Thinking Strategies: Using Art to Deepen Learning Across School Disciplines. Harvard Education Press; 2013.

Hailey D, Miller A, Yenawine P. Understanding visual literacy: the visual thinking strategies approach. In: Baylen DM, D’Alba A. Essentials of Teaching and Integrating Visual and Media Literacy: Visualizing Learning. Springer Cham; 2015:49-73. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-05837-5

Howley L, Gaufberg E, King BE. The Fundamental Role of the Arts and Humanities in Medical Education. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2020. Accessed December 18, 2025. https://store.aamc.org/the-fundamental-role-of-the-arts-and-humanities-in-medical-education.html

Impact of a Museum-Based Retreat on the Clinical Skills and Well-Being of Dermatology Residents and Faculty

Impact of a Museum-Based Retreat on the Clinical Skills and Well-Being of Dermatology Residents and Faculty

Practice Points

- Arts-based programming positively impacts resident competencies that are important to the practice of medicine.

- Incorporating arts-based programming in the dermatology residency curriculum can enhance resident well-being and the ability to be better clinicians.

Interactive Approach to Teaching Mohs Micrographic Surgery to Dermatology Residents

Interactive Approach to Teaching Mohs Micrographic Surgery to Dermatology Residents

Practice Gap

Tissue processing and complete margin assessment in Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) are challenging concepts for residents, yet they are essential components of the dermatology residency curriculum. We propose a hands-on active teaching method using craft foam blocks to help residents master these techniques. Prior educational tools have included instructional videos1 as well as the peanut butter–cup and cantaloupe analogies.2,3 Specifically, our method utilizes inexpensive, readily available supplies that allow for repeated practice in a low-stakes environment without limitation of resources. This method provides an immersive, hands-on experience that allows residents to perform multiple practice excisions and simulate positive peripheral or deep margins, unlike tools that offer only fixed-depth or purely visual representations. Additionally, our learning model uniquely enables residents to flatten the simulated tissue, providing a clearer understanding of how a 3-dimensional specimen is transformed on a slide during histologic preparation. This step is particularly important, as tissue architecture can shift during processing, making it one of the most difficult concepts to grasp without hands-on experience. Having a multitude of teaching methods is crucial to accommodate various learning styles, and active learning has been shown to enhance retention for dermatology residents.4

The Technique

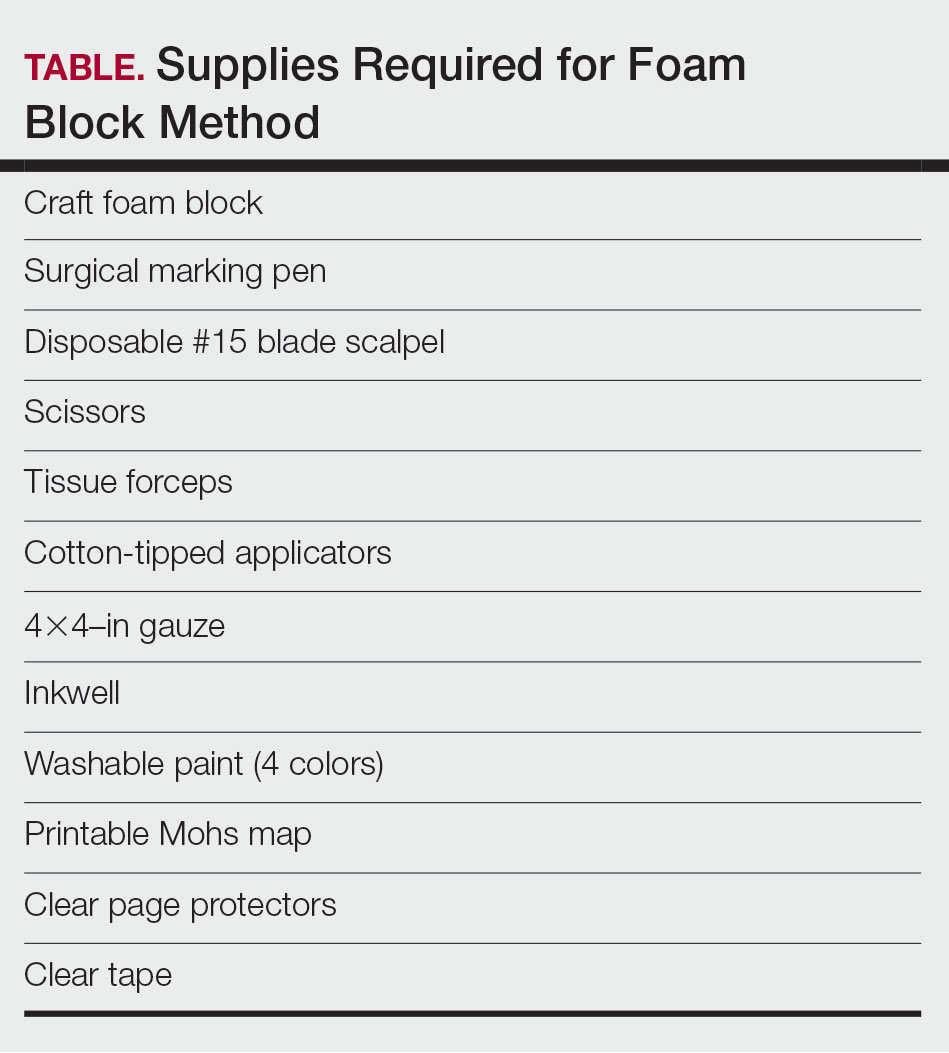

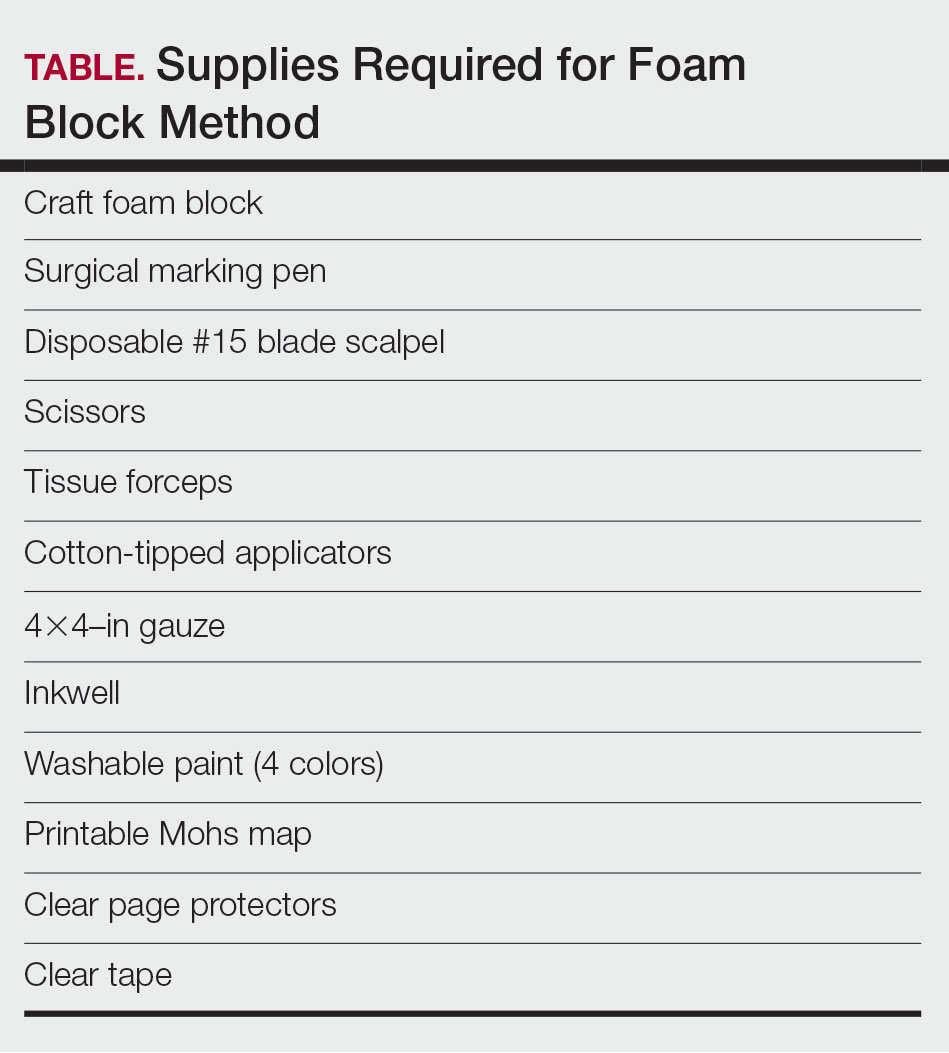

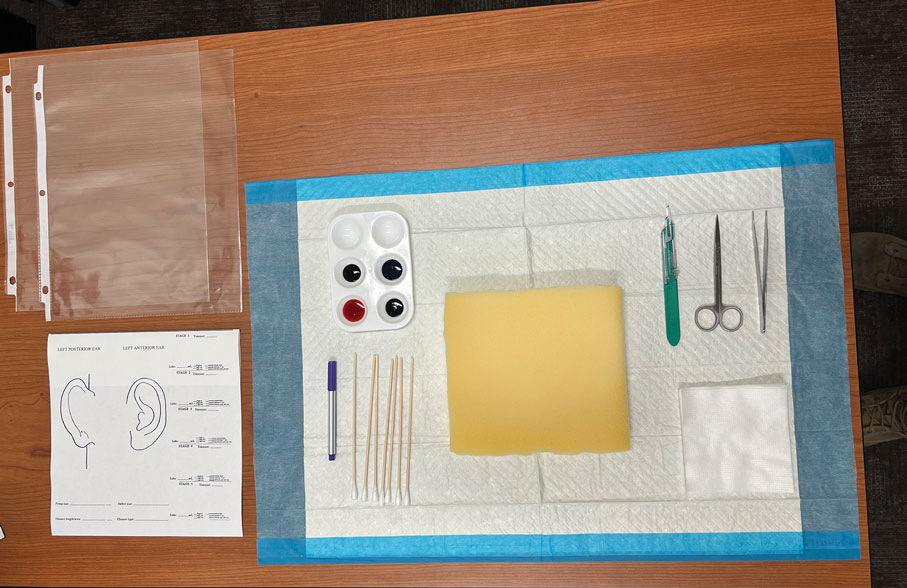

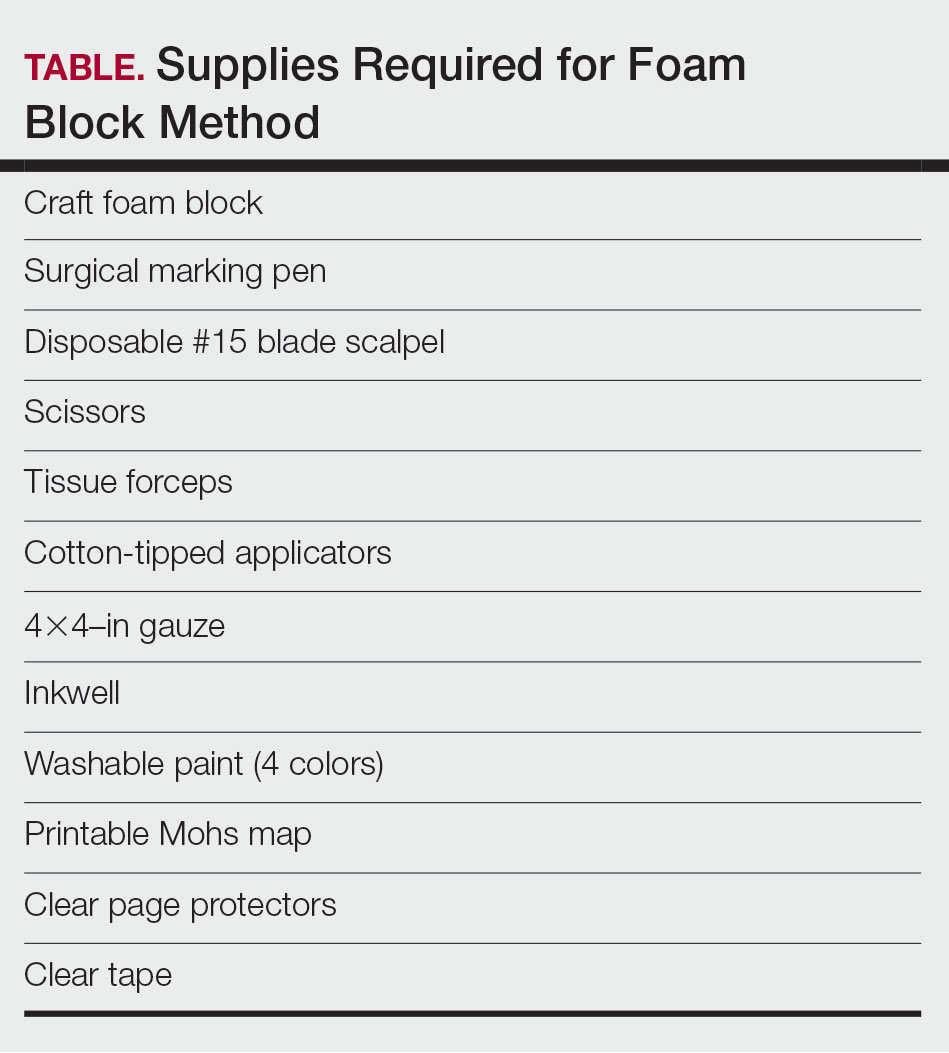

Residents use simple art supplies (including craft foam blocks and ink) and inexpensive, readily available surgical tools to simulate MMS (Table)(Figure 1). If desired, the resident can follow along with the comprehensive, stepwise textbook description of MMS, outlined by Benedetto et al5 to contextualize this hands-on exercise within a standardized didactic framework.

The foam block, which represents patient tissue, serves as the specimen. The resident begins by freehand drawing a simulated cutaneous tumor directly onto the foam using a surgical marking pen. At this point, the instructor discusses the advantages and limitations of tumor debulking with a sharp blade or curette. Residents then mark appropriate margins (1-3 mm) of normal-appearing “epidermis” on the foam block and add hash marks for orientation. This is another opportunity for the instructor to discuss common methods for marking tissue in vivo and to review situations when larger or smaller margins might be appropriate.

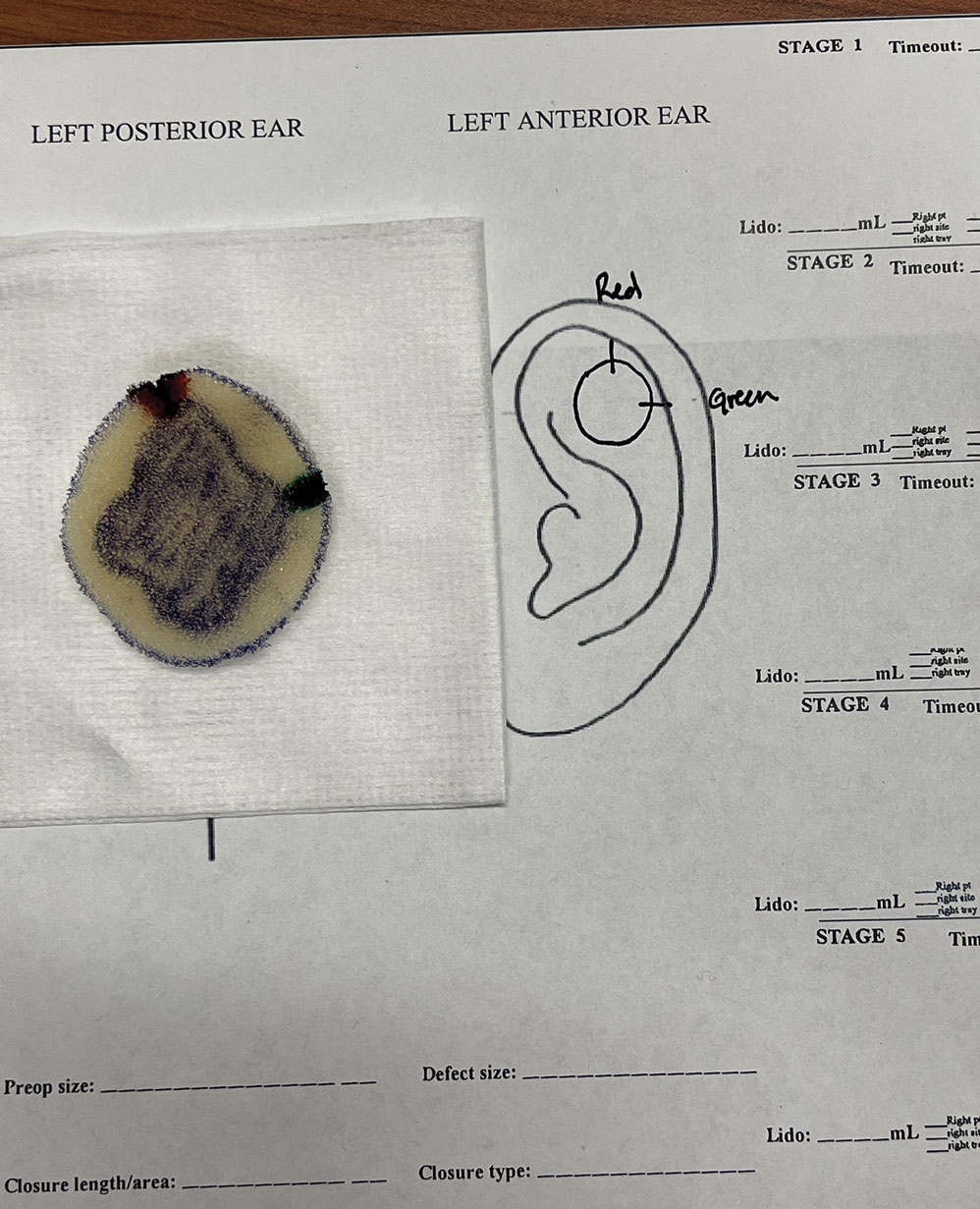

Next, the resident removes the first layer of simulated tissue using a disposable #15 blade scalpel at a 45° angle circumferentially and deep around the representative tumor. The resident also may use scissors and tissue forceps to remove the representative tumor. Next, the excised foam layer (the simulated “specimen”) is transferred to gauze. To demonstrate a positive margin, the resident or instructor marks the deep or peripheral foam block with a surgical marking pen, indicating residual tumor (Figure 2). This allows for multiple sequential layers of foam to be removed, demonstrating successive stages of MMS.

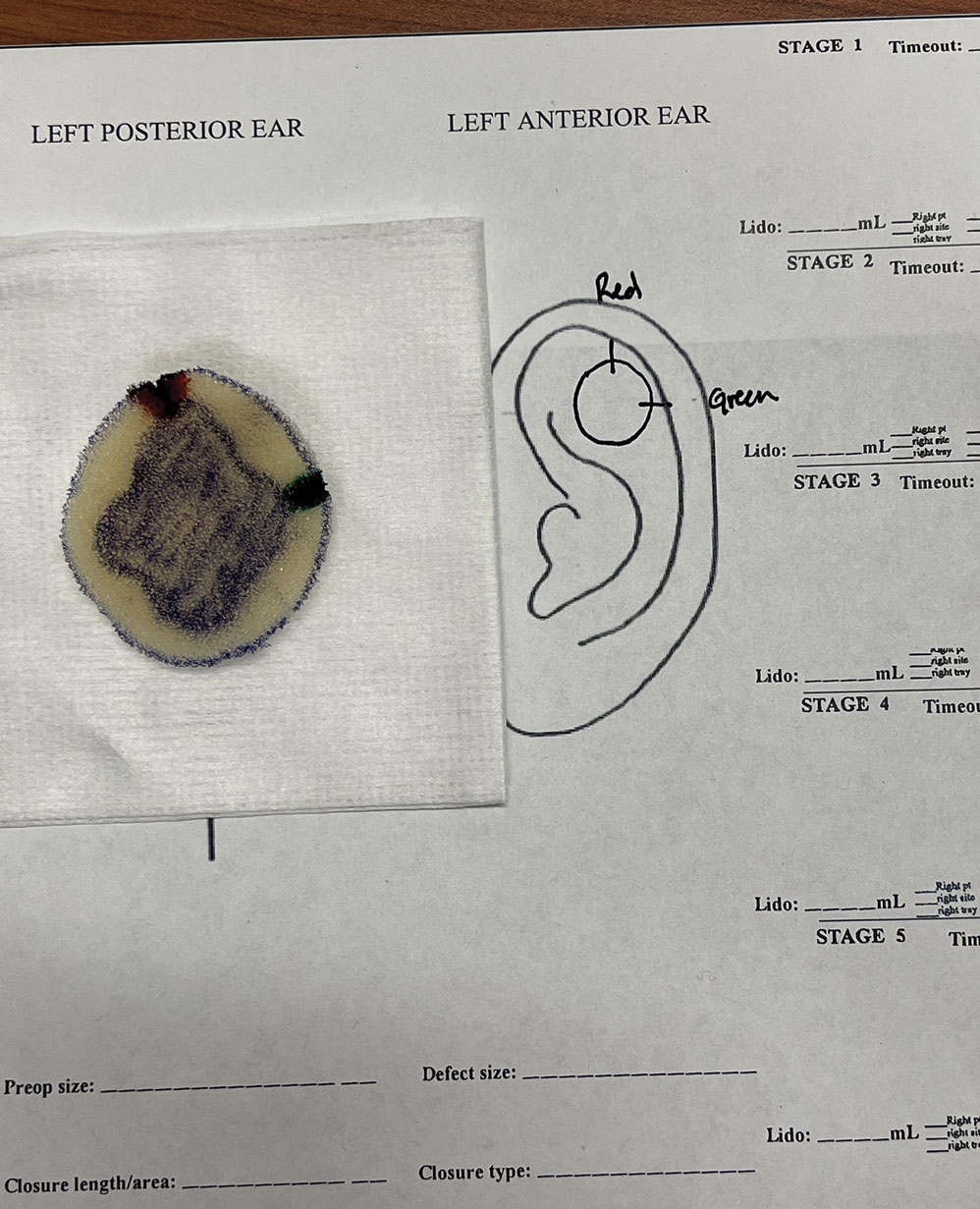

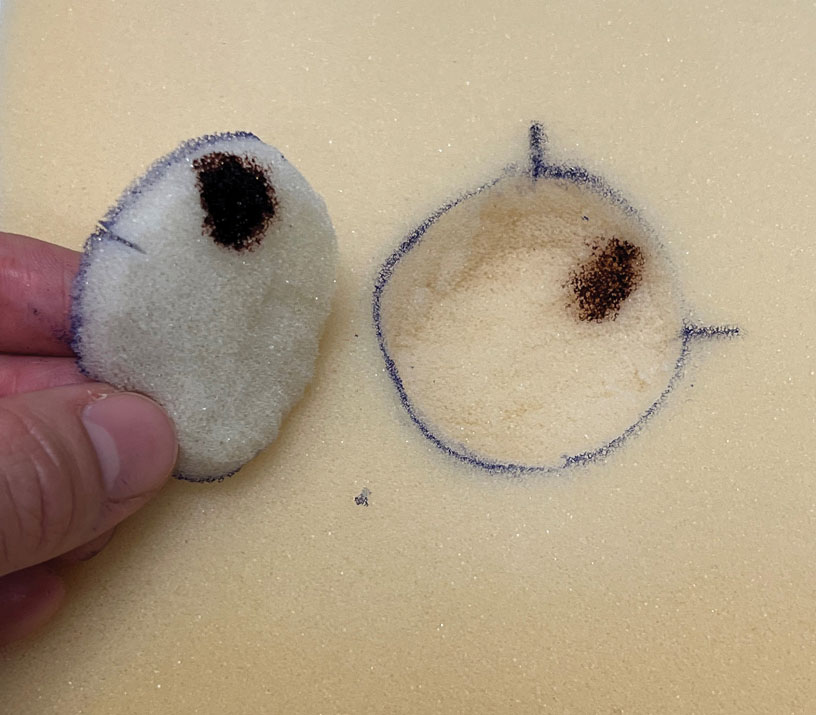

An inkwell holds different colors of washable paint to simulate tissue inking. After excision, the resident uses cotton-tipped applicators to apply different paint colors to the edges of the excised foam specimen at designated orientation points (eg, 3 o'clock and 12 o'clock). The resident then records the location of the excised sample by hand-drawing it on a printable Mohs map, labeling the corresponding paint colors to indicate orientation (Figure 3).

The resident then places the specimen between 2 plastic page protectors mimicking a glass slide and cover slip. Clear tape can be used to help flatten the specimen (Figure 4). The tissue is compressed between the page protector so that the simulated epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous fat are all in the same plane. At this stage, the instructor may discuss the use of relaxing incisions, especially for deeper tissue specimens or when excision at a 45° bevel is not achieved.5 The view from the underside of the page protector reveals 100% of the specimen’s margin and mimics the first cut off the tissue block. The resident can visualize the complete circumferential, peripheral, and deep margins and can easily identify any positive margins. At this point, the exercise can conclude, or the resident can explore further stages for positive margins, bisected specimens, or other tissue preparation variations.

Practice Implications

By individually designing and removing a representative tumor with margins, creating hash marks, and preparing a tissue specimen for histologic analysis, our interactive teaching method provides dermatology residents with a relatively simple, effective, and active learning experience for MMS outside the surgical setting. Using a piece of craft foam allows the representative tissue to be manipulated and flattened, similar to cutaneous tissue. This method was implemented and refined across 3 separate teaching sessions held by teaching faculty (E.I.P and E.B.W.) at the San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium Dermatology Residency Program (San Antonio, Texas). This method has consistently generated strong resident engagement and prompted insightful questions and discussions. Program directors at other residency programs can readily incorporate this method in their surgical curriculum by allocating a brief didactic period to the exercise and facilitating the discussion with a dermatologic surgeon. Its simplicity, low cost, and effectiveness make the foam block model an easily adoptable teaching tool for dermatology residency programs seeking to provide a comprehensive, hands-on understanding of MMS.

- McNeil E, Reich H, Hurliman E. Educational video improves dermatology residents’ understanding of Mohs micrographic surgery: a surveybased matched cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:926-927. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.01.013

- Lee E, Wolverton JE, Somani AK. A simple, effective analogy to elucidate the Mohs micrographic surgery procedure—the peanut butter cup. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:743-744. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2017.0614

- Vassantachart JM, Guccione J, Seeburger J. Clinical pearl: Mohs cantaloupe analogy for the dermatology resident. Cutis. 2018; 102:65-66.

- Stratman EJ, Vogel CA, Reck SJ, et al. Analysis of dermatology resident self-reported successful learning styles and implications for core competency curriculum development. Med Teach. 2008;30:420-425. doi:10.1080/01421590801946988

- Benedetto PX, Poblete-Lopez C. Mohs micrographic surgery technique. Dermatol Clinics. 2011;29:141-151. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.02.002

Practice Gap

Tissue processing and complete margin assessment in Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) are challenging concepts for residents, yet they are essential components of the dermatology residency curriculum. We propose a hands-on active teaching method using craft foam blocks to help residents master these techniques. Prior educational tools have included instructional videos1 as well as the peanut butter–cup and cantaloupe analogies.2,3 Specifically, our method utilizes inexpensive, readily available supplies that allow for repeated practice in a low-stakes environment without limitation of resources. This method provides an immersive, hands-on experience that allows residents to perform multiple practice excisions and simulate positive peripheral or deep margins, unlike tools that offer only fixed-depth or purely visual representations. Additionally, our learning model uniquely enables residents to flatten the simulated tissue, providing a clearer understanding of how a 3-dimensional specimen is transformed on a slide during histologic preparation. This step is particularly important, as tissue architecture can shift during processing, making it one of the most difficult concepts to grasp without hands-on experience. Having a multitude of teaching methods is crucial to accommodate various learning styles, and active learning has been shown to enhance retention for dermatology residents.4

The Technique

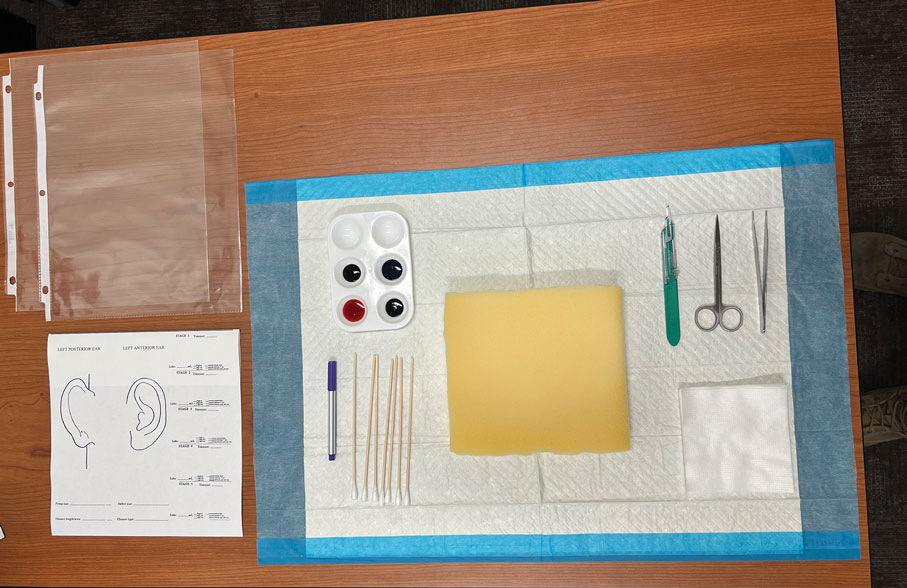

Residents use simple art supplies (including craft foam blocks and ink) and inexpensive, readily available surgical tools to simulate MMS (Table)(Figure 1). If desired, the resident can follow along with the comprehensive, stepwise textbook description of MMS, outlined by Benedetto et al5 to contextualize this hands-on exercise within a standardized didactic framework.

The foam block, which represents patient tissue, serves as the specimen. The resident begins by freehand drawing a simulated cutaneous tumor directly onto the foam using a surgical marking pen. At this point, the instructor discusses the advantages and limitations of tumor debulking with a sharp blade or curette. Residents then mark appropriate margins (1-3 mm) of normal-appearing “epidermis” on the foam block and add hash marks for orientation. This is another opportunity for the instructor to discuss common methods for marking tissue in vivo and to review situations when larger or smaller margins might be appropriate.

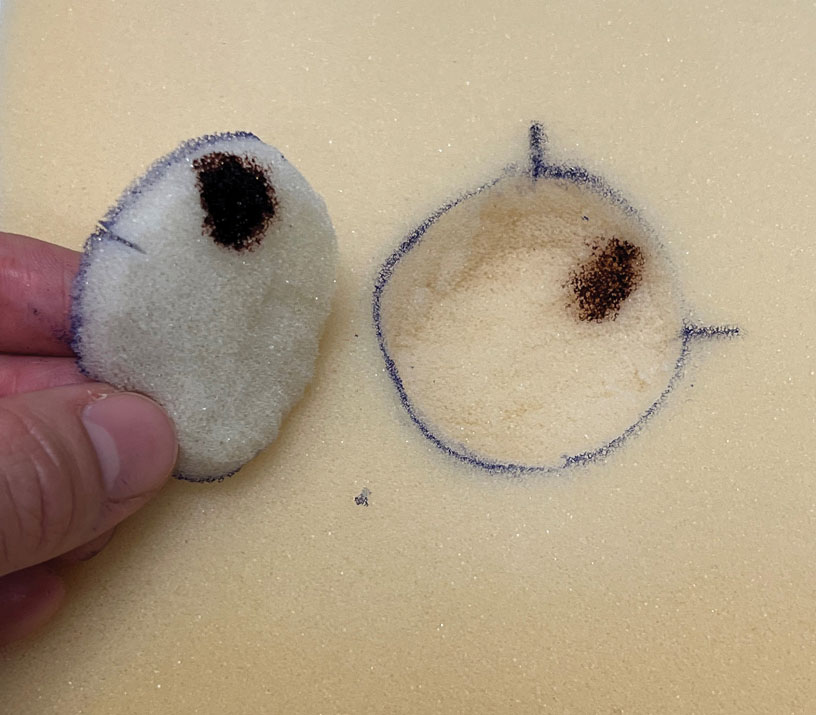

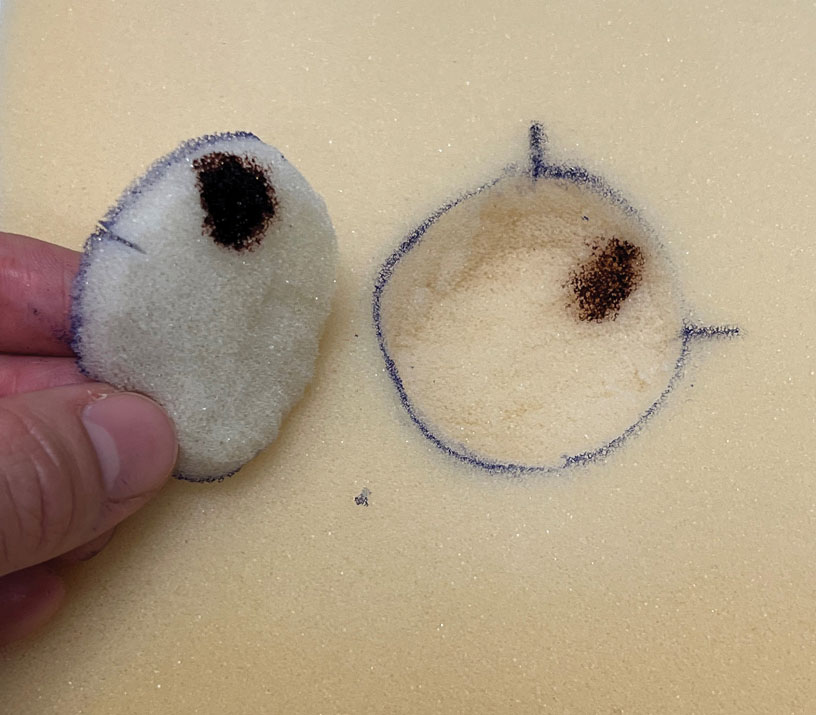

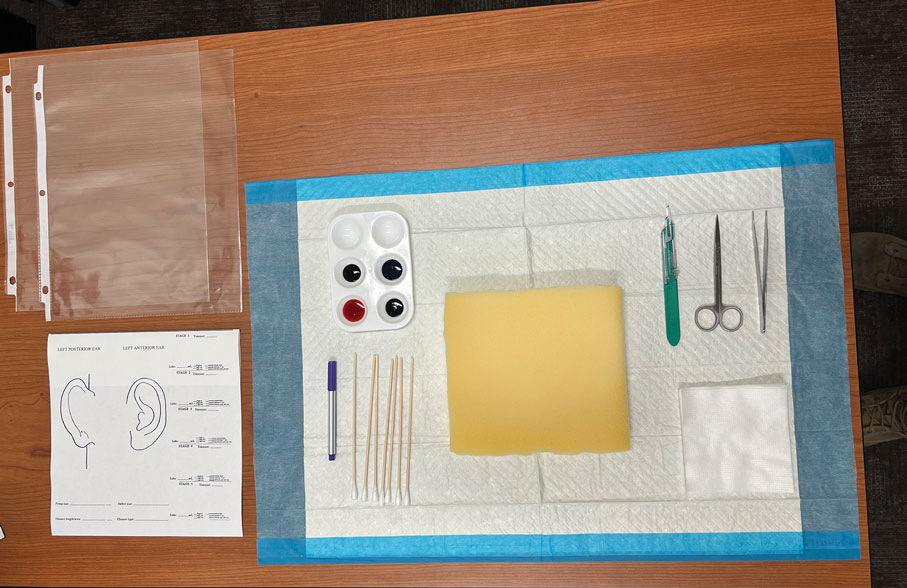

Next, the resident removes the first layer of simulated tissue using a disposable #15 blade scalpel at a 45° angle circumferentially and deep around the representative tumor. The resident also may use scissors and tissue forceps to remove the representative tumor. Next, the excised foam layer (the simulated “specimen”) is transferred to gauze. To demonstrate a positive margin, the resident or instructor marks the deep or peripheral foam block with a surgical marking pen, indicating residual tumor (Figure 2). This allows for multiple sequential layers of foam to be removed, demonstrating successive stages of MMS.

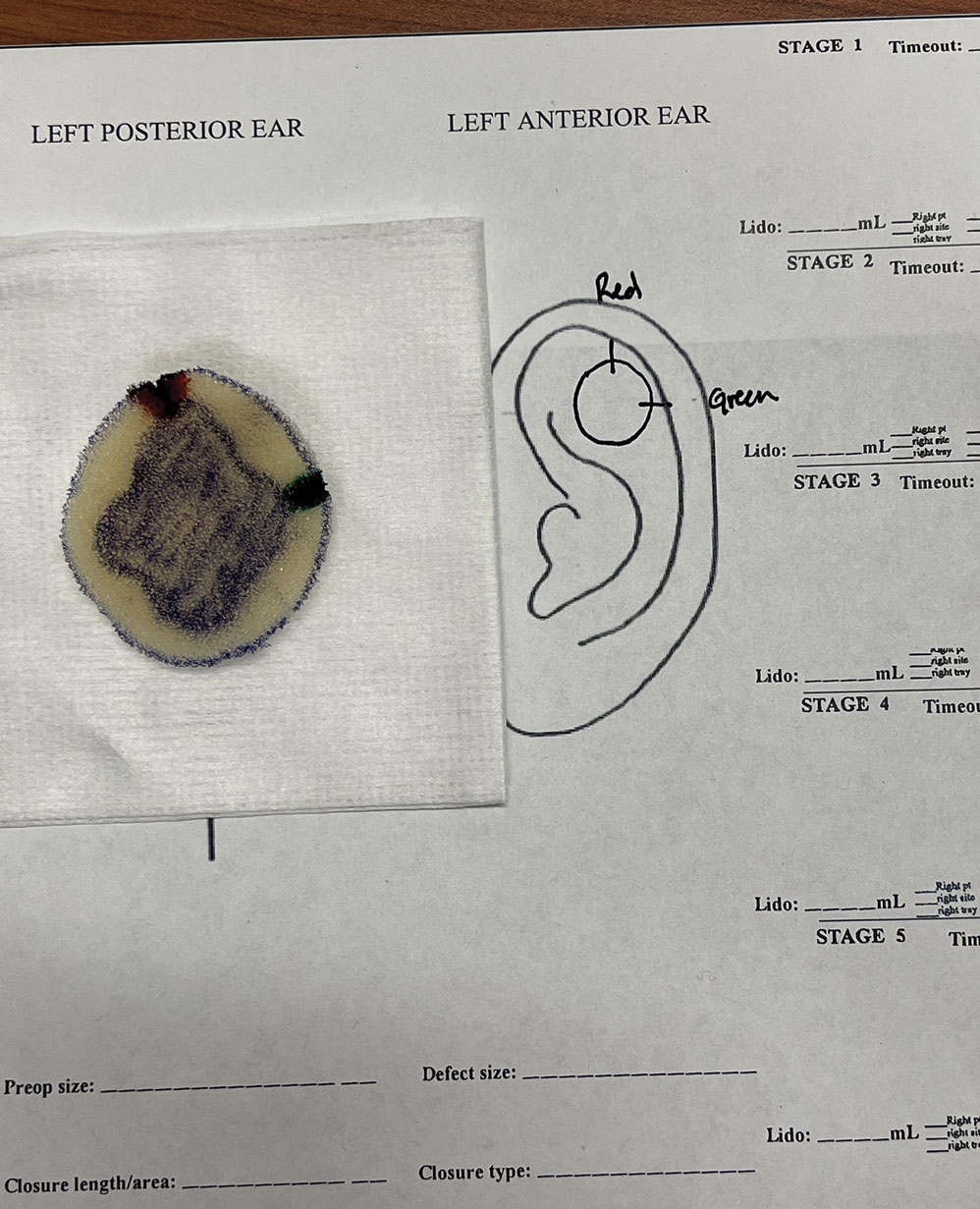

An inkwell holds different colors of washable paint to simulate tissue inking. After excision, the resident uses cotton-tipped applicators to apply different paint colors to the edges of the excised foam specimen at designated orientation points (eg, 3 o'clock and 12 o'clock). The resident then records the location of the excised sample by hand-drawing it on a printable Mohs map, labeling the corresponding paint colors to indicate orientation (Figure 3).

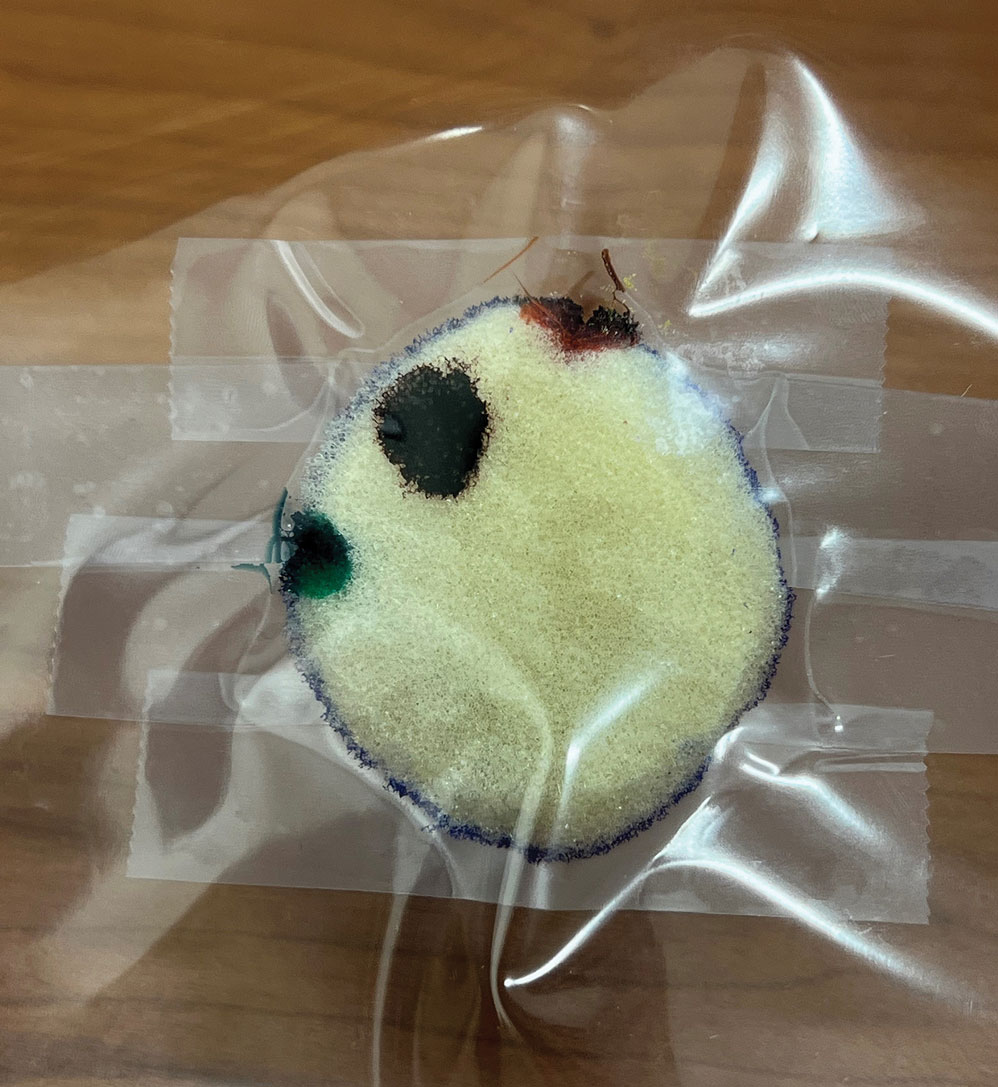

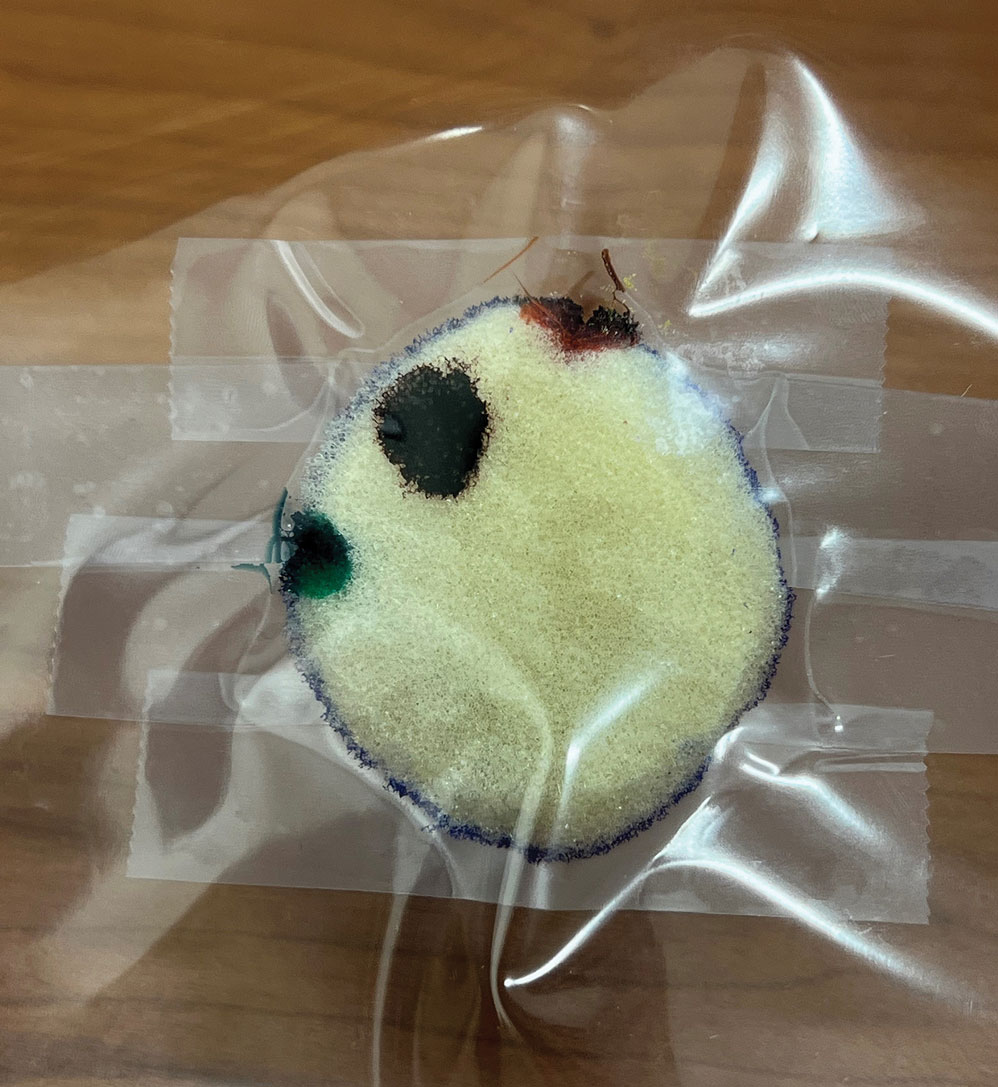

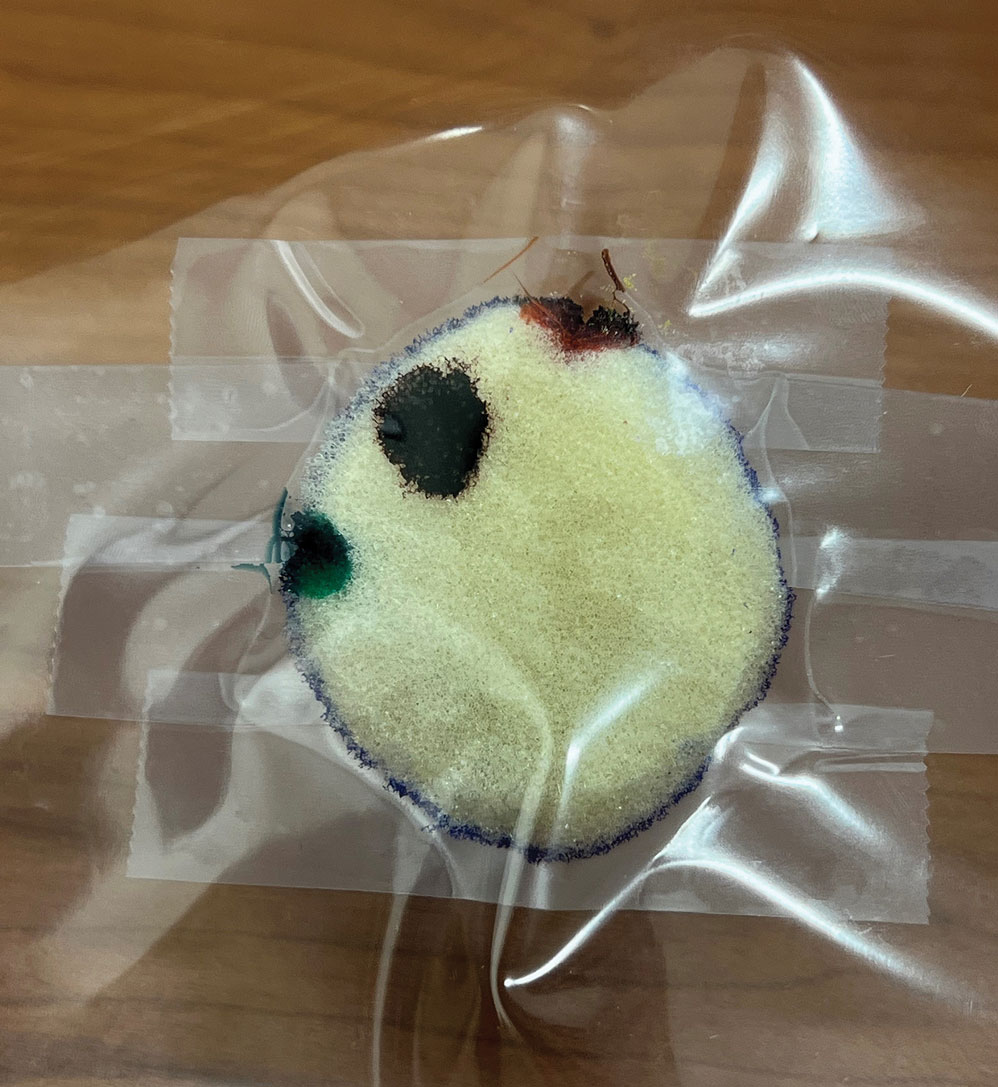

The resident then places the specimen between 2 plastic page protectors mimicking a glass slide and cover slip. Clear tape can be used to help flatten the specimen (Figure 4). The tissue is compressed between the page protector so that the simulated epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous fat are all in the same plane. At this stage, the instructor may discuss the use of relaxing incisions, especially for deeper tissue specimens or when excision at a 45° bevel is not achieved.5 The view from the underside of the page protector reveals 100% of the specimen’s margin and mimics the first cut off the tissue block. The resident can visualize the complete circumferential, peripheral, and deep margins and can easily identify any positive margins. At this point, the exercise can conclude, or the resident can explore further stages for positive margins, bisected specimens, or other tissue preparation variations.

Practice Implications

By individually designing and removing a representative tumor with margins, creating hash marks, and preparing a tissue specimen for histologic analysis, our interactive teaching method provides dermatology residents with a relatively simple, effective, and active learning experience for MMS outside the surgical setting. Using a piece of craft foam allows the representative tissue to be manipulated and flattened, similar to cutaneous tissue. This method was implemented and refined across 3 separate teaching sessions held by teaching faculty (E.I.P and E.B.W.) at the San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium Dermatology Residency Program (San Antonio, Texas). This method has consistently generated strong resident engagement and prompted insightful questions and discussions. Program directors at other residency programs can readily incorporate this method in their surgical curriculum by allocating a brief didactic period to the exercise and facilitating the discussion with a dermatologic surgeon. Its simplicity, low cost, and effectiveness make the foam block model an easily adoptable teaching tool for dermatology residency programs seeking to provide a comprehensive, hands-on understanding of MMS.

Practice Gap

Tissue processing and complete margin assessment in Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) are challenging concepts for residents, yet they are essential components of the dermatology residency curriculum. We propose a hands-on active teaching method using craft foam blocks to help residents master these techniques. Prior educational tools have included instructional videos1 as well as the peanut butter–cup and cantaloupe analogies.2,3 Specifically, our method utilizes inexpensive, readily available supplies that allow for repeated practice in a low-stakes environment without limitation of resources. This method provides an immersive, hands-on experience that allows residents to perform multiple practice excisions and simulate positive peripheral or deep margins, unlike tools that offer only fixed-depth or purely visual representations. Additionally, our learning model uniquely enables residents to flatten the simulated tissue, providing a clearer understanding of how a 3-dimensional specimen is transformed on a slide during histologic preparation. This step is particularly important, as tissue architecture can shift during processing, making it one of the most difficult concepts to grasp without hands-on experience. Having a multitude of teaching methods is crucial to accommodate various learning styles, and active learning has been shown to enhance retention for dermatology residents.4

The Technique

Residents use simple art supplies (including craft foam blocks and ink) and inexpensive, readily available surgical tools to simulate MMS (Table)(Figure 1). If desired, the resident can follow along with the comprehensive, stepwise textbook description of MMS, outlined by Benedetto et al5 to contextualize this hands-on exercise within a standardized didactic framework.

The foam block, which represents patient tissue, serves as the specimen. The resident begins by freehand drawing a simulated cutaneous tumor directly onto the foam using a surgical marking pen. At this point, the instructor discusses the advantages and limitations of tumor debulking with a sharp blade or curette. Residents then mark appropriate margins (1-3 mm) of normal-appearing “epidermis” on the foam block and add hash marks for orientation. This is another opportunity for the instructor to discuss common methods for marking tissue in vivo and to review situations when larger or smaller margins might be appropriate.

Next, the resident removes the first layer of simulated tissue using a disposable #15 blade scalpel at a 45° angle circumferentially and deep around the representative tumor. The resident also may use scissors and tissue forceps to remove the representative tumor. Next, the excised foam layer (the simulated “specimen”) is transferred to gauze. To demonstrate a positive margin, the resident or instructor marks the deep or peripheral foam block with a surgical marking pen, indicating residual tumor (Figure 2). This allows for multiple sequential layers of foam to be removed, demonstrating successive stages of MMS.

An inkwell holds different colors of washable paint to simulate tissue inking. After excision, the resident uses cotton-tipped applicators to apply different paint colors to the edges of the excised foam specimen at designated orientation points (eg, 3 o'clock and 12 o'clock). The resident then records the location of the excised sample by hand-drawing it on a printable Mohs map, labeling the corresponding paint colors to indicate orientation (Figure 3).

The resident then places the specimen between 2 plastic page protectors mimicking a glass slide and cover slip. Clear tape can be used to help flatten the specimen (Figure 4). The tissue is compressed between the page protector so that the simulated epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous fat are all in the same plane. At this stage, the instructor may discuss the use of relaxing incisions, especially for deeper tissue specimens or when excision at a 45° bevel is not achieved.5 The view from the underside of the page protector reveals 100% of the specimen’s margin and mimics the first cut off the tissue block. The resident can visualize the complete circumferential, peripheral, and deep margins and can easily identify any positive margins. At this point, the exercise can conclude, or the resident can explore further stages for positive margins, bisected specimens, or other tissue preparation variations.

Practice Implications

By individually designing and removing a representative tumor with margins, creating hash marks, and preparing a tissue specimen for histologic analysis, our interactive teaching method provides dermatology residents with a relatively simple, effective, and active learning experience for MMS outside the surgical setting. Using a piece of craft foam allows the representative tissue to be manipulated and flattened, similar to cutaneous tissue. This method was implemented and refined across 3 separate teaching sessions held by teaching faculty (E.I.P and E.B.W.) at the San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium Dermatology Residency Program (San Antonio, Texas). This method has consistently generated strong resident engagement and prompted insightful questions and discussions. Program directors at other residency programs can readily incorporate this method in their surgical curriculum by allocating a brief didactic period to the exercise and facilitating the discussion with a dermatologic surgeon. Its simplicity, low cost, and effectiveness make the foam block model an easily adoptable teaching tool for dermatology residency programs seeking to provide a comprehensive, hands-on understanding of MMS.

- McNeil E, Reich H, Hurliman E. Educational video improves dermatology residents’ understanding of Mohs micrographic surgery: a surveybased matched cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:926-927. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.01.013

- Lee E, Wolverton JE, Somani AK. A simple, effective analogy to elucidate the Mohs micrographic surgery procedure—the peanut butter cup. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:743-744. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2017.0614

- Vassantachart JM, Guccione J, Seeburger J. Clinical pearl: Mohs cantaloupe analogy for the dermatology resident. Cutis. 2018; 102:65-66.

- Stratman EJ, Vogel CA, Reck SJ, et al. Analysis of dermatology resident self-reported successful learning styles and implications for core competency curriculum development. Med Teach. 2008;30:420-425. doi:10.1080/01421590801946988

- Benedetto PX, Poblete-Lopez C. Mohs micrographic surgery technique. Dermatol Clinics. 2011;29:141-151. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.02.002

- McNeil E, Reich H, Hurliman E. Educational video improves dermatology residents’ understanding of Mohs micrographic surgery: a surveybased matched cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:926-927. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.01.013

- Lee E, Wolverton JE, Somani AK. A simple, effective analogy to elucidate the Mohs micrographic surgery procedure—the peanut butter cup. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:743-744. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2017.0614

- Vassantachart JM, Guccione J, Seeburger J. Clinical pearl: Mohs cantaloupe analogy for the dermatology resident. Cutis. 2018; 102:65-66.

- Stratman EJ, Vogel CA, Reck SJ, et al. Analysis of dermatology resident self-reported successful learning styles and implications for core competency curriculum development. Med Teach. 2008;30:420-425. doi:10.1080/01421590801946988

- Benedetto PX, Poblete-Lopez C. Mohs micrographic surgery technique. Dermatol Clinics. 2011;29:141-151. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.02.002

Interactive Approach to Teaching Mohs Micrographic Surgery to Dermatology Residents

Interactive Approach to Teaching Mohs Micrographic Surgery to Dermatology Residents

Mobile Tender Papule on the Scalp

Mobile Tender Papule on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Spiradenocylindroma

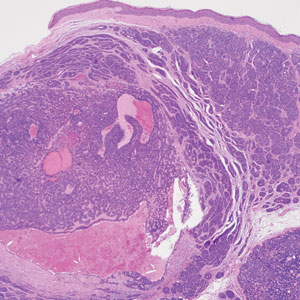

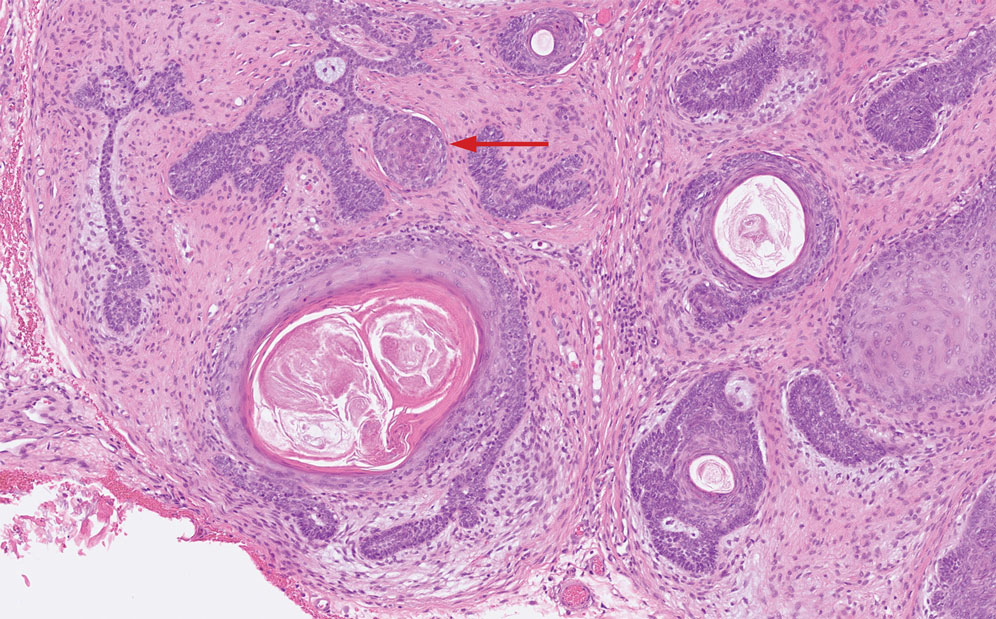

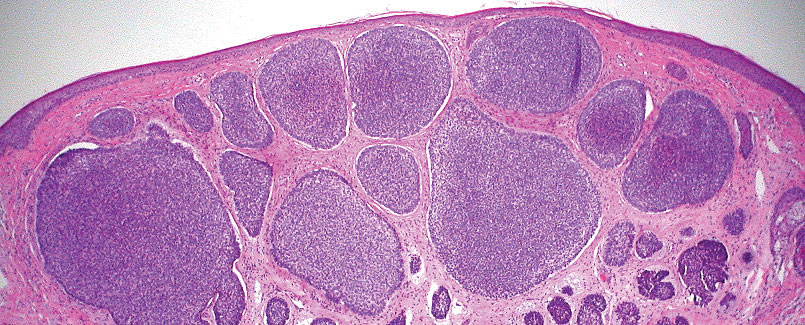

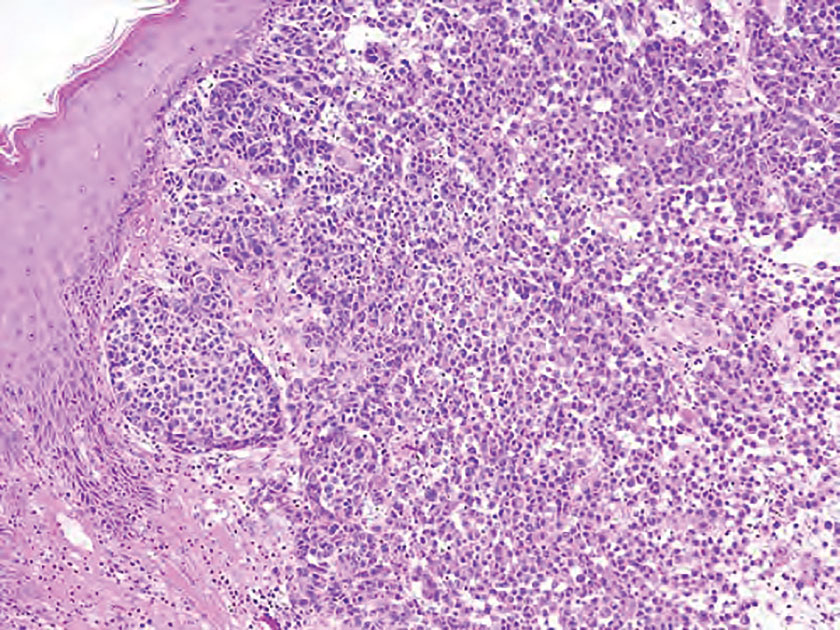

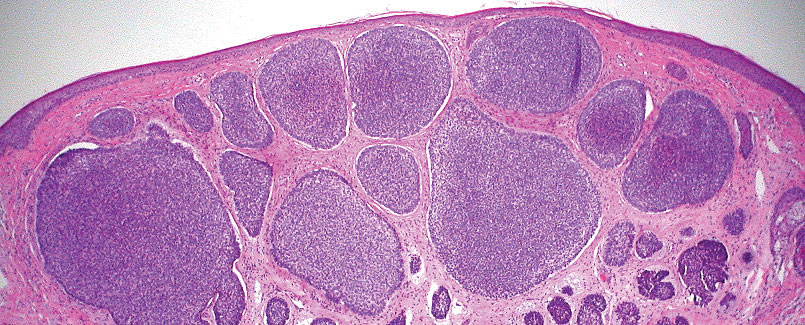

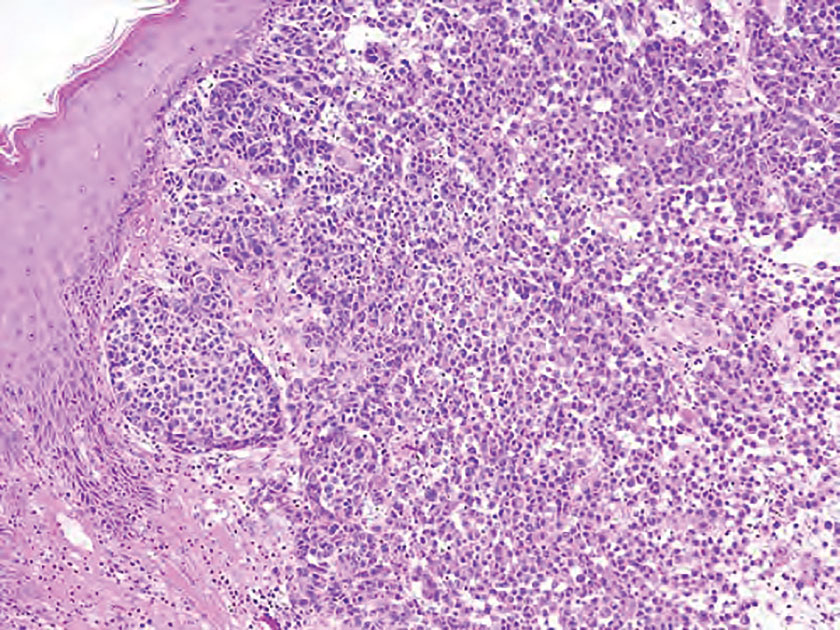

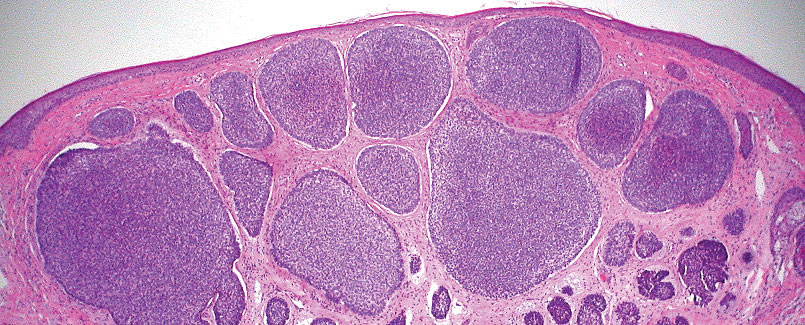

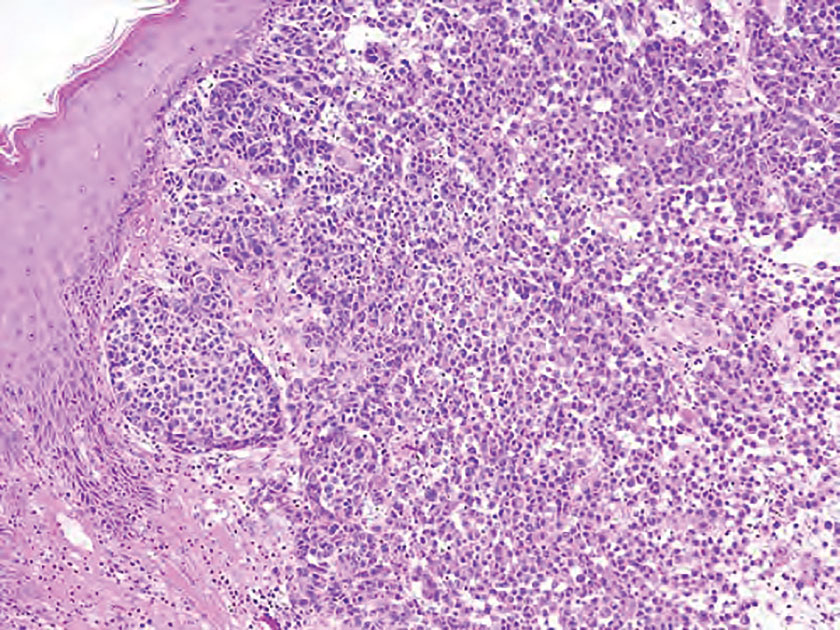

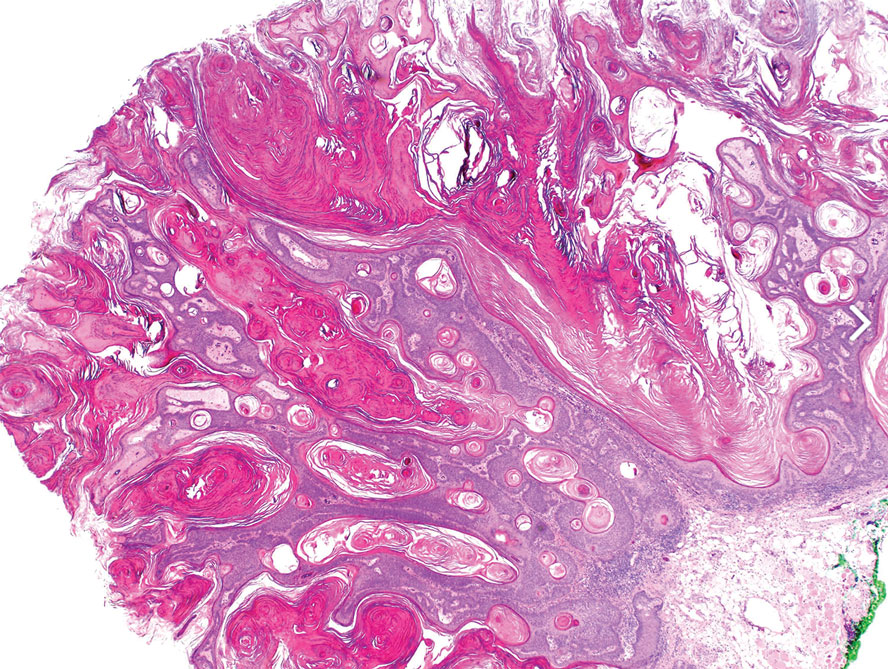

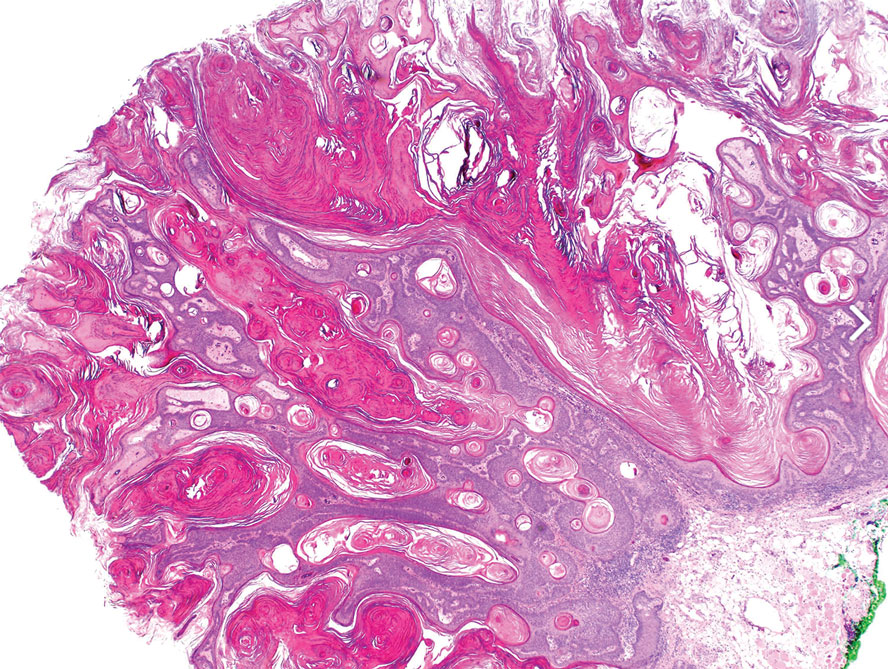

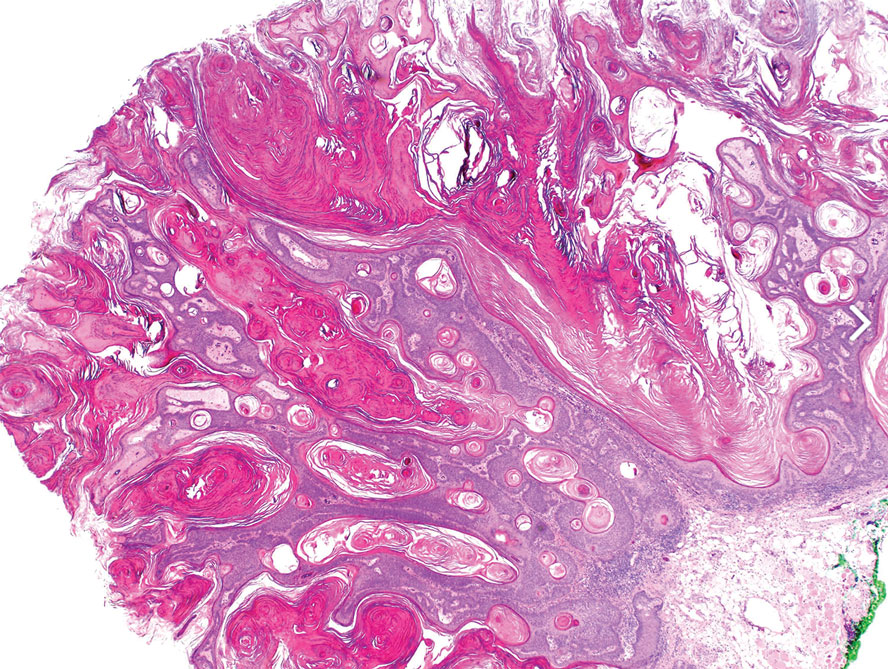

T he biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of spiradenocylindroma with negative margins. At 6-week follow-up, the patient had no signs of recurrence. Spiradenocylindroma is a benign hybrid neoplasm consisting of histologically intermixed areas representing the spectrum of morphology between spiradenoma and cylindromas.1,2 Both spiradenoma and cylindroma comprise 2 distinct populations of dark and pale basaloid cells.2,3 The spiradenomatous areas of the spiradenocylindroma are arranged in large, well-circumscribed collections of small, darkly staining cells with interspersed lymphocytes and a thin basement membrane surrounding spiradenocylindroma component.2,3 The spiradenocylindroma regions also may contain tubular structures dilated by hemorrhage.2 In contrast, the cylindromatous regions have a jigsaw-puzzle configuration of polygonal tumor nests containing peripherally palisading dark cells and central pale cells, surrounded by a thick basement membrane (top quiz image).2,3

Clinically, sporadic spiradenocylindromas may resemble other lesions, manifesting as a papule or nodule with coloration ranging from gray-blue to salmon pink along with arborizing telangiectasias.4,5 Although spiradenocylindromas typically are found on the head, neck, and trunk, they also have been reported in the kidney, vulva, anus, and rectum.2,6,7 Not only are spiradenocylindromas clinically indistinct from other adnexal growths, but they also share some features with basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) and amelanotic melanomas.8 Features of arborizing telangiectasias on a papule may resemble BCC, requiring histopathology for a definitive diagnosis.

Spiradenocylindromas classically are associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, a rare, autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by a germline mutation in the cylindromatosis lysine 63 deubiquitinase tumor-suppressor gene.5 Patients develop adnexal neoplasms of the folliculosebaceous-apocrine unit, including spiradenomas, cylindromas, and trichoepitheliomas.5 Rarely, malignant transformation to spiradenocylindrocarcinoma has been reported.9 Features of malignant transformation include loss of the 2-cell population, cytologic atypia, increased mitotic activity, and loss of intratumoral lymphocytes.10

Trichoepitheliomas are benign, firm, flesh-colored papules to nodules that commonly are found on the mid face but may appear on the scalp, neck, and upper trunk.5-11 Trichoepitheliomas are closely related to spiradenomas and cylindromas; the familial form, multiple familial trichoepitheliomas, exists on a spectrum with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.3,11 Multiple familial trichoepithelioma is characterized by multiple trichoepitheliomas without accompanying spiradenomas, cylindromas, or spiradenocylindromas.3 On histopathology, trichoepitheliomas are distinguished by cribriform clusters or nests of basaloid follicular germinative cells with bulbar differentiation, known as papillary mesenchymal bodies, surrounded by an adherent stroma (eFigure 1).3,5,11 In addition to follicular bulbar differentiation, trichoepitheliomas are surrounded by an adherent cellular stroma without the retraction artifact around tumor islands seen in BCC, although artifactual clefts may occur within the stroma.11 In contrast, spiradenocylindromas do not demonstrate keratin cysts or artifactual clefts within the stroma.

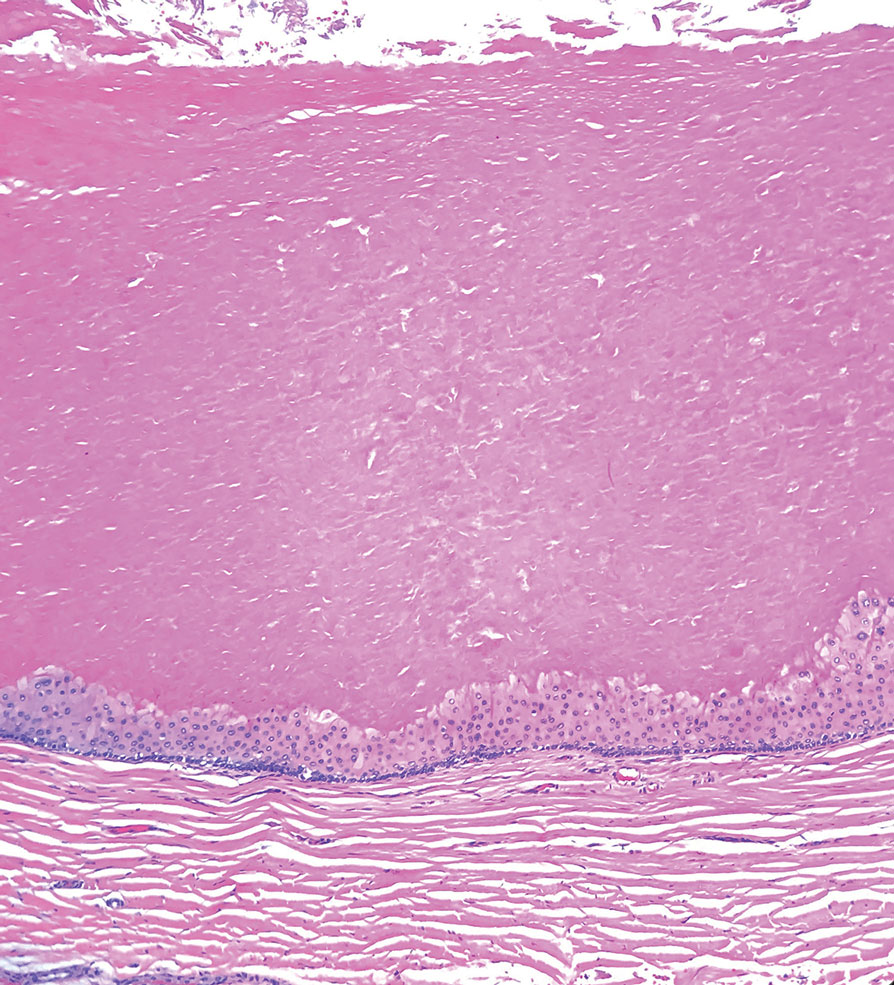

Trichilemmal cysts, or pilar cysts, are benign adnexal neoplasms derived from the outer root sheath at the isthmus.12-14 Approximately 90% of pilar cysts are found on the scalp and 2% of trichilemmal cysts may progress to a proliferating trichilemmal cyst, which is locally aggressive and contains an expanding buckled epithelium within the cyst space.12,14 Clinically, trichilemmal cysts are slow-growing, smooth, round, mobile nodules without a central punctum.12,13 On histopathology, the cyst wall contains peripherally palisading basal cells and maturing cells showing no intercellular bridging (eFigure 2). As the cells mature, they swell with pale cytoplasm and abruptly keratinize without a granular layer, a process known as trichilemmal keratinization.12-14 Additionally, cholesterol clefts are common in the keratinous lumen, and about 25% of cysts contain calcifications.13,14 The broadly basophilic spiradenocylindromas sharply contrast the abundant eosinophilic keratin of trichilemmal cysts.

Basal cell carcinoma is a slow-growing, locally destructive neoplasm that develops due to chronic sun exposure; thus, BCCs commonly arise on exposed areas of the face, head, neck, arms, and legs.15 Nodular BCC is the most common subtype and typically manifests as a shiny pearly papule or nodule with a smooth surface, rolled borders, and arborizing telangiectasias.16 On histopathology, nodular BCCs demonstrate nests or nodules of basaloid keratinocytes with peripheral palisading and retraction artifact between the tumor and stroma (eFigure 3).15,16 A lack of retraction artifact, cystic dilation of tubular structures, jigsaw molding of nests, and a distinct 2-cell population distinguish spiradenocylindroma from BCC. Of note, in rare instances BCCs also may display a thick fibrous stroma, similar to the stroma of cylindromas.15

Amelanotic melanoma is a variant of melanoma characterized by little to no pigment. Any of the 4 classic subtypes of melanoma (nodular, superficial spreading, lentigo maligna, acral lentiginous) can be amelanotic.17 Clinically, amelanotic melanomas can vary greatly, manifesting as erythematous macules, dermal plaques, or papulonodular lesions, often with scaling.18 On histopathology, findings common to all melanomas include cellular atypia, mitoses, pagetoid spread, and pleomorphism (eFigure 4).18,19 Immunohistochemistry is an important method to distinguish melanoma from other melanocytic proliferations and to aid in the assessment of Breslow depth. Markers include SOX10 (sex-determining region Y-box transcription factor 10), S100, and MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1/melan-A).19,20 Expression of PRAME (preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma) often is positive but is not necessary for diagnosis.21 Histologically, the atypical pleomorphic cells of melanoma are markedly distinct from both spiradenomas and cylindromas.

- Soyer HP, Kerl H, Ott A. Spiradenocylindroma—more than a coincidence? Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20:315-317.

- Michal M, Lamovec J, Mukenˇ snabl P, et al. Spiradenocylindromas of the skin: tumors with morphological features of spiradenoma and cylindroma in the same lesion: report of 12 cases. Pathol Int. 1999;49:419-425.

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-130.

- Bostan E, Boynuyogun E, Gokoz O, et al. Hybrid tumor “spiradenocylindroma” with unusual dermoscopic features. An Bras Dermatol. 2023;98:382-384.

- Pinho AC, Gouveia MJ, Gameiro AR, et al. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome—an underrecognized cause of multiple familial scalp tumors: report of a new germline mutation. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2015;9:67-70.

- Ströbel P, Zettl A, Ren Z, et al. Spiradenocylindroma of the kidney: clinical and genetic findings suggesting a role of somatic mutation of the CYLD1 gene in the oncogenesis of an unusual renal neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:119-124.

- Kacerovska D, Szepe P, Vanecek T, et al. Spiradenocylindroma-like basaloid carcinoma of the anus and rectum: case report, including HPV studies and analysis of the CYLD gene mutations. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:472-476.

- Silvestri F, Maida P, Venturi F, et al. Scalp spiradenocylindroma: a challenging dermoscopic diagnosis. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E14307.

- Held L, Ruetten A, Saggini A, et al. Metaplastic spiradenocarcinoma: report of two cases with sarcomatous differentiation. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:384-389.

- Płachta I, Kleibert M, Czarnecka AM, et al. Current diagnosis and treatment options for cutaneous adnexal neoplasms with apocrine and eccrine differentiation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:5077.

- Johnson H, Robles M, Kamino H, et al. Trichoepithelioma. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:5.

- He P, Cui LG, Wang JR, et al. Trichilemmal cyst: clinical and sonographic feature. J Ultrasound Med. 2019;38:91-96.

- Liu M, Han H, Zheng Y, et al. Pilar cyst on the dorsum of hand: a case report and review of literature. Medicine (United States). 2020;99:E21519.

- Ramaswamy AS, Manjunatha HK, Sunilkumar B, et al. Morphological spectrum of pilar cysts. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:124-128.

- Stanoszek LM, Wang GY, Harms PW. Histologic mimics of basal cell carcinoma. In: Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. Vol 141. College of American Pathologists; 2017:1490-1502.

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:303-317.

- Kaizer-Salk KA, Herten RJ, Ragsdale BD, et al. Amelanotic melanoma: a unique case study and review of the literature. BMJ Case Rep. 2018:bcr2017222751.

- Silva TS, de Araujo LR, Faro GB de A, et al. Nodular amelanotic melanoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:497-498.

- Bobos M. Histopathologic classification and prognostic factors of melanoma: a 2021 update. Ital J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;156:300-321.

- Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, et al. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:433-444.

- Lezcano C, Jungbluth AA, Nehal KS, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1456-1465.

The Diagnosis: Spiradenocylindroma

T he biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of spiradenocylindroma with negative margins. At 6-week follow-up, the patient had no signs of recurrence. Spiradenocylindroma is a benign hybrid neoplasm consisting of histologically intermixed areas representing the spectrum of morphology between spiradenoma and cylindromas.1,2 Both spiradenoma and cylindroma comprise 2 distinct populations of dark and pale basaloid cells.2,3 The spiradenomatous areas of the spiradenocylindroma are arranged in large, well-circumscribed collections of small, darkly staining cells with interspersed lymphocytes and a thin basement membrane surrounding spiradenocylindroma component.2,3 The spiradenocylindroma regions also may contain tubular structures dilated by hemorrhage.2 In contrast, the cylindromatous regions have a jigsaw-puzzle configuration of polygonal tumor nests containing peripherally palisading dark cells and central pale cells, surrounded by a thick basement membrane (top quiz image).2,3

Clinically, sporadic spiradenocylindromas may resemble other lesions, manifesting as a papule or nodule with coloration ranging from gray-blue to salmon pink along with arborizing telangiectasias.4,5 Although spiradenocylindromas typically are found on the head, neck, and trunk, they also have been reported in the kidney, vulva, anus, and rectum.2,6,7 Not only are spiradenocylindromas clinically indistinct from other adnexal growths, but they also share some features with basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) and amelanotic melanomas.8 Features of arborizing telangiectasias on a papule may resemble BCC, requiring histopathology for a definitive diagnosis.

Spiradenocylindromas classically are associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, a rare, autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by a germline mutation in the cylindromatosis lysine 63 deubiquitinase tumor-suppressor gene.5 Patients develop adnexal neoplasms of the folliculosebaceous-apocrine unit, including spiradenomas, cylindromas, and trichoepitheliomas.5 Rarely, malignant transformation to spiradenocylindrocarcinoma has been reported.9 Features of malignant transformation include loss of the 2-cell population, cytologic atypia, increased mitotic activity, and loss of intratumoral lymphocytes.10

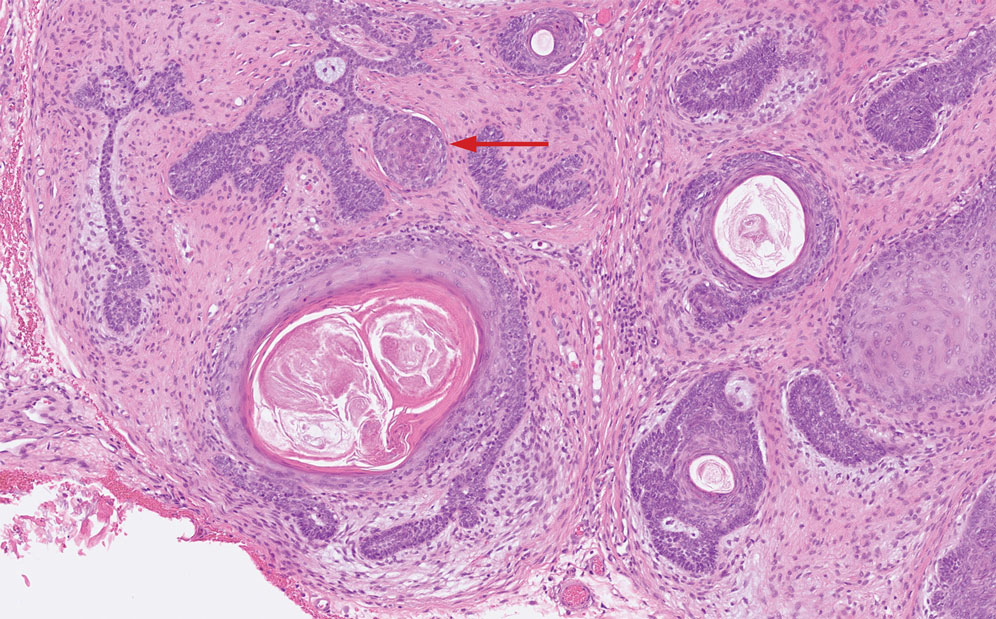

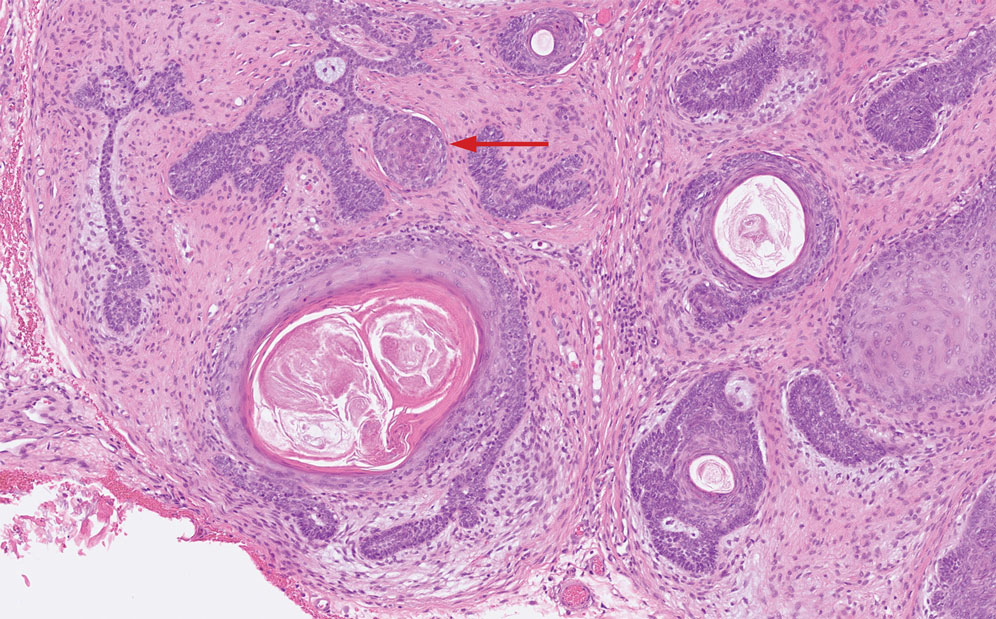

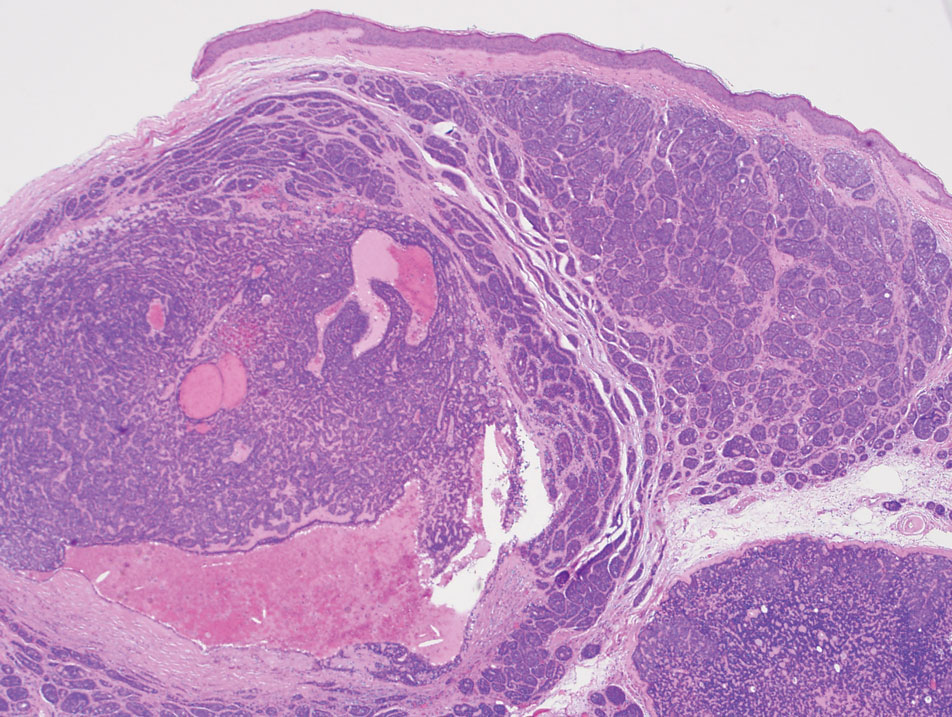

Trichoepitheliomas are benign, firm, flesh-colored papules to nodules that commonly are found on the mid face but may appear on the scalp, neck, and upper trunk.5-11 Trichoepitheliomas are closely related to spiradenomas and cylindromas; the familial form, multiple familial trichoepitheliomas, exists on a spectrum with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.3,11 Multiple familial trichoepithelioma is characterized by multiple trichoepitheliomas without accompanying spiradenomas, cylindromas, or spiradenocylindromas.3 On histopathology, trichoepitheliomas are distinguished by cribriform clusters or nests of basaloid follicular germinative cells with bulbar differentiation, known as papillary mesenchymal bodies, surrounded by an adherent stroma (eFigure 1).3,5,11 In addition to follicular bulbar differentiation, trichoepitheliomas are surrounded by an adherent cellular stroma without the retraction artifact around tumor islands seen in BCC, although artifactual clefts may occur within the stroma.11 In contrast, spiradenocylindromas do not demonstrate keratin cysts or artifactual clefts within the stroma.

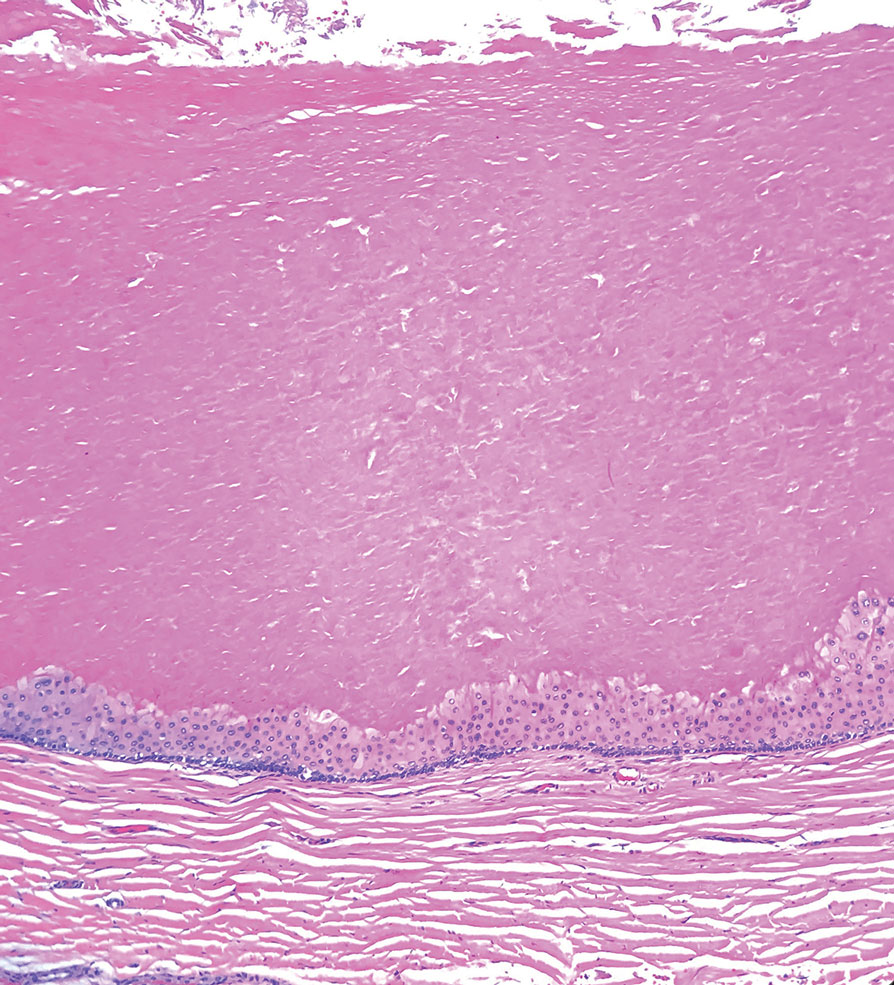

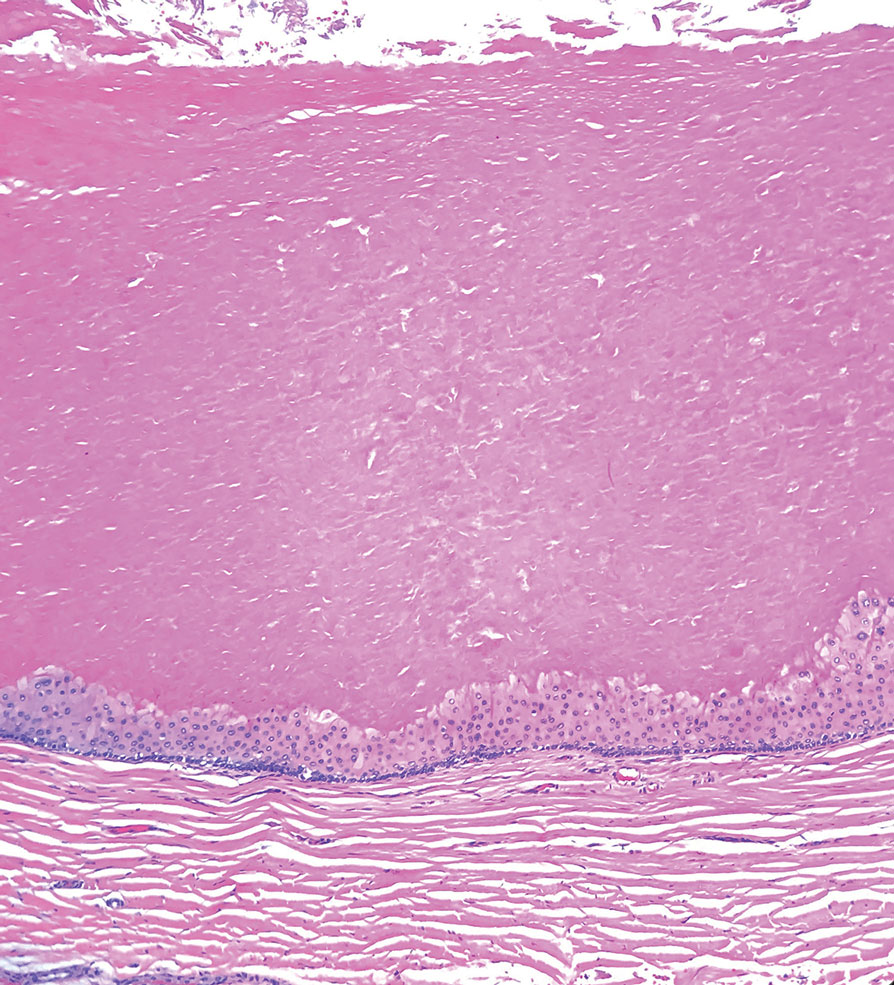

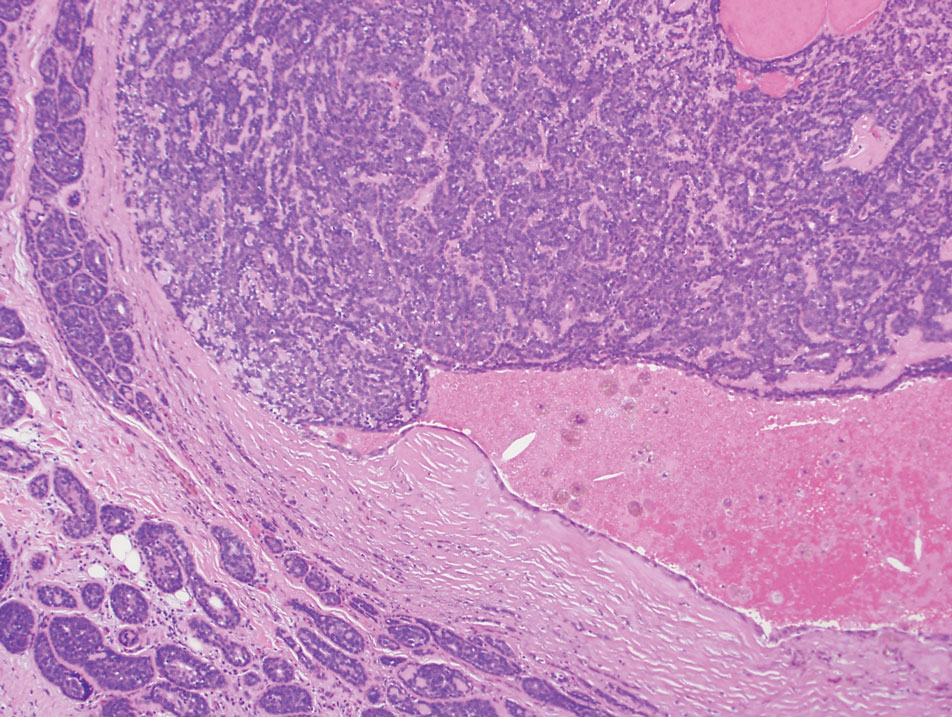

Trichilemmal cysts, or pilar cysts, are benign adnexal neoplasms derived from the outer root sheath at the isthmus.12-14 Approximately 90% of pilar cysts are found on the scalp and 2% of trichilemmal cysts may progress to a proliferating trichilemmal cyst, which is locally aggressive and contains an expanding buckled epithelium within the cyst space.12,14 Clinically, trichilemmal cysts are slow-growing, smooth, round, mobile nodules without a central punctum.12,13 On histopathology, the cyst wall contains peripherally palisading basal cells and maturing cells showing no intercellular bridging (eFigure 2). As the cells mature, they swell with pale cytoplasm and abruptly keratinize without a granular layer, a process known as trichilemmal keratinization.12-14 Additionally, cholesterol clefts are common in the keratinous lumen, and about 25% of cysts contain calcifications.13,14 The broadly basophilic spiradenocylindromas sharply contrast the abundant eosinophilic keratin of trichilemmal cysts.

Basal cell carcinoma is a slow-growing, locally destructive neoplasm that develops due to chronic sun exposure; thus, BCCs commonly arise on exposed areas of the face, head, neck, arms, and legs.15 Nodular BCC is the most common subtype and typically manifests as a shiny pearly papule or nodule with a smooth surface, rolled borders, and arborizing telangiectasias.16 On histopathology, nodular BCCs demonstrate nests or nodules of basaloid keratinocytes with peripheral palisading and retraction artifact between the tumor and stroma (eFigure 3).15,16 A lack of retraction artifact, cystic dilation of tubular structures, jigsaw molding of nests, and a distinct 2-cell population distinguish spiradenocylindroma from BCC. Of note, in rare instances BCCs also may display a thick fibrous stroma, similar to the stroma of cylindromas.15

Amelanotic melanoma is a variant of melanoma characterized by little to no pigment. Any of the 4 classic subtypes of melanoma (nodular, superficial spreading, lentigo maligna, acral lentiginous) can be amelanotic.17 Clinically, amelanotic melanomas can vary greatly, manifesting as erythematous macules, dermal plaques, or papulonodular lesions, often with scaling.18 On histopathology, findings common to all melanomas include cellular atypia, mitoses, pagetoid spread, and pleomorphism (eFigure 4).18,19 Immunohistochemistry is an important method to distinguish melanoma from other melanocytic proliferations and to aid in the assessment of Breslow depth. Markers include SOX10 (sex-determining region Y-box transcription factor 10), S100, and MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1/melan-A).19,20 Expression of PRAME (preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma) often is positive but is not necessary for diagnosis.21 Histologically, the atypical pleomorphic cells of melanoma are markedly distinct from both spiradenomas and cylindromas.

The Diagnosis: Spiradenocylindroma

T he biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of spiradenocylindroma with negative margins. At 6-week follow-up, the patient had no signs of recurrence. Spiradenocylindroma is a benign hybrid neoplasm consisting of histologically intermixed areas representing the spectrum of morphology between spiradenoma and cylindromas.1,2 Both spiradenoma and cylindroma comprise 2 distinct populations of dark and pale basaloid cells.2,3 The spiradenomatous areas of the spiradenocylindroma are arranged in large, well-circumscribed collections of small, darkly staining cells with interspersed lymphocytes and a thin basement membrane surrounding spiradenocylindroma component.2,3 The spiradenocylindroma regions also may contain tubular structures dilated by hemorrhage.2 In contrast, the cylindromatous regions have a jigsaw-puzzle configuration of polygonal tumor nests containing peripherally palisading dark cells and central pale cells, surrounded by a thick basement membrane (top quiz image).2,3

Clinically, sporadic spiradenocylindromas may resemble other lesions, manifesting as a papule or nodule with coloration ranging from gray-blue to salmon pink along with arborizing telangiectasias.4,5 Although spiradenocylindromas typically are found on the head, neck, and trunk, they also have been reported in the kidney, vulva, anus, and rectum.2,6,7 Not only are spiradenocylindromas clinically indistinct from other adnexal growths, but they also share some features with basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) and amelanotic melanomas.8 Features of arborizing telangiectasias on a papule may resemble BCC, requiring histopathology for a definitive diagnosis.

Spiradenocylindromas classically are associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, a rare, autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by a germline mutation in the cylindromatosis lysine 63 deubiquitinase tumor-suppressor gene.5 Patients develop adnexal neoplasms of the folliculosebaceous-apocrine unit, including spiradenomas, cylindromas, and trichoepitheliomas.5 Rarely, malignant transformation to spiradenocylindrocarcinoma has been reported.9 Features of malignant transformation include loss of the 2-cell population, cytologic atypia, increased mitotic activity, and loss of intratumoral lymphocytes.10

Trichoepitheliomas are benign, firm, flesh-colored papules to nodules that commonly are found on the mid face but may appear on the scalp, neck, and upper trunk.5-11 Trichoepitheliomas are closely related to spiradenomas and cylindromas; the familial form, multiple familial trichoepitheliomas, exists on a spectrum with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.3,11 Multiple familial trichoepithelioma is characterized by multiple trichoepitheliomas without accompanying spiradenomas, cylindromas, or spiradenocylindromas.3 On histopathology, trichoepitheliomas are distinguished by cribriform clusters or nests of basaloid follicular germinative cells with bulbar differentiation, known as papillary mesenchymal bodies, surrounded by an adherent stroma (eFigure 1).3,5,11 In addition to follicular bulbar differentiation, trichoepitheliomas are surrounded by an adherent cellular stroma without the retraction artifact around tumor islands seen in BCC, although artifactual clefts may occur within the stroma.11 In contrast, spiradenocylindromas do not demonstrate keratin cysts or artifactual clefts within the stroma.

Trichilemmal cysts, or pilar cysts, are benign adnexal neoplasms derived from the outer root sheath at the isthmus.12-14 Approximately 90% of pilar cysts are found on the scalp and 2% of trichilemmal cysts may progress to a proliferating trichilemmal cyst, which is locally aggressive and contains an expanding buckled epithelium within the cyst space.12,14 Clinically, trichilemmal cysts are slow-growing, smooth, round, mobile nodules without a central punctum.12,13 On histopathology, the cyst wall contains peripherally palisading basal cells and maturing cells showing no intercellular bridging (eFigure 2). As the cells mature, they swell with pale cytoplasm and abruptly keratinize without a granular layer, a process known as trichilemmal keratinization.12-14 Additionally, cholesterol clefts are common in the keratinous lumen, and about 25% of cysts contain calcifications.13,14 The broadly basophilic spiradenocylindromas sharply contrast the abundant eosinophilic keratin of trichilemmal cysts.

Basal cell carcinoma is a slow-growing, locally destructive neoplasm that develops due to chronic sun exposure; thus, BCCs commonly arise on exposed areas of the face, head, neck, arms, and legs.15 Nodular BCC is the most common subtype and typically manifests as a shiny pearly papule or nodule with a smooth surface, rolled borders, and arborizing telangiectasias.16 On histopathology, nodular BCCs demonstrate nests or nodules of basaloid keratinocytes with peripheral palisading and retraction artifact between the tumor and stroma (eFigure 3).15,16 A lack of retraction artifact, cystic dilation of tubular structures, jigsaw molding of nests, and a distinct 2-cell population distinguish spiradenocylindroma from BCC. Of note, in rare instances BCCs also may display a thick fibrous stroma, similar to the stroma of cylindromas.15

Amelanotic melanoma is a variant of melanoma characterized by little to no pigment. Any of the 4 classic subtypes of melanoma (nodular, superficial spreading, lentigo maligna, acral lentiginous) can be amelanotic.17 Clinically, amelanotic melanomas can vary greatly, manifesting as erythematous macules, dermal plaques, or papulonodular lesions, often with scaling.18 On histopathology, findings common to all melanomas include cellular atypia, mitoses, pagetoid spread, and pleomorphism (eFigure 4).18,19 Immunohistochemistry is an important method to distinguish melanoma from other melanocytic proliferations and to aid in the assessment of Breslow depth. Markers include SOX10 (sex-determining region Y-box transcription factor 10), S100, and MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1/melan-A).19,20 Expression of PRAME (preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma) often is positive but is not necessary for diagnosis.21 Histologically, the atypical pleomorphic cells of melanoma are markedly distinct from both spiradenomas and cylindromas.

- Soyer HP, Kerl H, Ott A. Spiradenocylindroma—more than a coincidence? Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20:315-317.

- Michal M, Lamovec J, Mukenˇ snabl P, et al. Spiradenocylindromas of the skin: tumors with morphological features of spiradenoma and cylindroma in the same lesion: report of 12 cases. Pathol Int. 1999;49:419-425.

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-130.

- Bostan E, Boynuyogun E, Gokoz O, et al. Hybrid tumor “spiradenocylindroma” with unusual dermoscopic features. An Bras Dermatol. 2023;98:382-384.

- Pinho AC, Gouveia MJ, Gameiro AR, et al. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome—an underrecognized cause of multiple familial scalp tumors: report of a new germline mutation. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2015;9:67-70.

- Ströbel P, Zettl A, Ren Z, et al. Spiradenocylindroma of the kidney: clinical and genetic findings suggesting a role of somatic mutation of the CYLD1 gene in the oncogenesis of an unusual renal neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:119-124.

- Kacerovska D, Szepe P, Vanecek T, et al. Spiradenocylindroma-like basaloid carcinoma of the anus and rectum: case report, including HPV studies and analysis of the CYLD gene mutations. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:472-476.

- Silvestri F, Maida P, Venturi F, et al. Scalp spiradenocylindroma: a challenging dermoscopic diagnosis. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E14307.

- Held L, Ruetten A, Saggini A, et al. Metaplastic spiradenocarcinoma: report of two cases with sarcomatous differentiation. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:384-389.

- Płachta I, Kleibert M, Czarnecka AM, et al. Current diagnosis and treatment options for cutaneous adnexal neoplasms with apocrine and eccrine differentiation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:5077.

- Johnson H, Robles M, Kamino H, et al. Trichoepithelioma. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:5.

- He P, Cui LG, Wang JR, et al. Trichilemmal cyst: clinical and sonographic feature. J Ultrasound Med. 2019;38:91-96.

- Liu M, Han H, Zheng Y, et al. Pilar cyst on the dorsum of hand: a case report and review of literature. Medicine (United States). 2020;99:E21519.

- Ramaswamy AS, Manjunatha HK, Sunilkumar B, et al. Morphological spectrum of pilar cysts. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:124-128.

- Stanoszek LM, Wang GY, Harms PW. Histologic mimics of basal cell carcinoma. In: Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. Vol 141. College of American Pathologists; 2017:1490-1502.

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:303-317.

- Kaizer-Salk KA, Herten RJ, Ragsdale BD, et al. Amelanotic melanoma: a unique case study and review of the literature. BMJ Case Rep. 2018:bcr2017222751.

- Silva TS, de Araujo LR, Faro GB de A, et al. Nodular amelanotic melanoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:497-498.

- Bobos M. Histopathologic classification and prognostic factors of melanoma: a 2021 update. Ital J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;156:300-321.

- Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, et al. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:433-444.

- Lezcano C, Jungbluth AA, Nehal KS, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1456-1465.

- Soyer HP, Kerl H, Ott A. Spiradenocylindroma—more than a coincidence? Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20:315-317.

- Michal M, Lamovec J, Mukenˇ snabl P, et al. Spiradenocylindromas of the skin: tumors with morphological features of spiradenoma and cylindroma in the same lesion: report of 12 cases. Pathol Int. 1999;49:419-425.

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-130.

- Bostan E, Boynuyogun E, Gokoz O, et al. Hybrid tumor “spiradenocylindroma” with unusual dermoscopic features. An Bras Dermatol. 2023;98:382-384.

- Pinho AC, Gouveia MJ, Gameiro AR, et al. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome—an underrecognized cause of multiple familial scalp tumors: report of a new germline mutation. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2015;9:67-70.

- Ströbel P, Zettl A, Ren Z, et al. Spiradenocylindroma of the kidney: clinical and genetic findings suggesting a role of somatic mutation of the CYLD1 gene in the oncogenesis of an unusual renal neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:119-124.

- Kacerovska D, Szepe P, Vanecek T, et al. Spiradenocylindroma-like basaloid carcinoma of the anus and rectum: case report, including HPV studies and analysis of the CYLD gene mutations. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:472-476.

- Silvestri F, Maida P, Venturi F, et al. Scalp spiradenocylindroma: a challenging dermoscopic diagnosis. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E14307.

- Held L, Ruetten A, Saggini A, et al. Metaplastic spiradenocarcinoma: report of two cases with sarcomatous differentiation. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:384-389.

- Płachta I, Kleibert M, Czarnecka AM, et al. Current diagnosis and treatment options for cutaneous adnexal neoplasms with apocrine and eccrine differentiation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:5077.

- Johnson H, Robles M, Kamino H, et al. Trichoepithelioma. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:5.

- He P, Cui LG, Wang JR, et al. Trichilemmal cyst: clinical and sonographic feature. J Ultrasound Med. 2019;38:91-96.

- Liu M, Han H, Zheng Y, et al. Pilar cyst on the dorsum of hand: a case report and review of literature. Medicine (United States). 2020;99:E21519.

- Ramaswamy AS, Manjunatha HK, Sunilkumar B, et al. Morphological spectrum of pilar cysts. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:124-128.

- Stanoszek LM, Wang GY, Harms PW. Histologic mimics of basal cell carcinoma. In: Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. Vol 141. College of American Pathologists; 2017:1490-1502.

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:303-317.

- Kaizer-Salk KA, Herten RJ, Ragsdale BD, et al. Amelanotic melanoma: a unique case study and review of the literature. BMJ Case Rep. 2018:bcr2017222751.

- Silva TS, de Araujo LR, Faro GB de A, et al. Nodular amelanotic melanoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:497-498.

- Bobos M. Histopathologic classification and prognostic factors of melanoma: a 2021 update. Ital J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;156:300-321.

- Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, et al. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:433-444.

- Lezcano C, Jungbluth AA, Nehal KS, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1456-1465.

Mobile Tender Papule on the Scalp

Mobile Tender Papule on the Scalp

A 73-year-old man presented to the plastic surgery department with a single, progressively enlarging nodule on the scalp of 1 year’s duration. Dermatologic examination revealed a 0.8-cm, soft, mobile, gray-blue, dome-shaped papule on the left postauricular scalp that was tender to palpation. There was no central punctum, and the patient denied any history of drainage or odor. He had no personal or family history of similar lesions. An excisional biopsy of the papule was performed.

Rupioid Id Reaction With Peripheral Eosinophilia

Rupioid Id Reaction With Peripheral Eosinophilia

To the Editor:

In dermatology, rupioid describes dirty-appearing scale. The term is derived from the Greek word rhupos, which translates to “dirty” or “filthy.” This type of scale also is called ostraceous, owing to its resemblance to an oyster shell. Histopathologically, rupioid or ostraceous scale corresponds to epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis. Therefore, the presence of rupioid scale is believed to reflect an exuberant inflammatory response. Several dermatologic conditions have been associated with rupioid scale, including psoriasis, secondary syphilis, reactive arthritis, histoplasmosis, and Norwegian scabies.1-4 Peripheral eosinophilia has been reported in eczematous dermatoses such as atopic dermatitis and contact dermatitis,5,6 but our review of the literature did not find it described in the context of id reactions. We report the case of a patient who developed a rupioid id reaction with peripheral eosinophilia.

An otherwise healthy 40-year-old woman presented with a generalized pruritic eruption of 1 month’s duration. Prior to onset, she was bitten by a bug on the left arm and covered the site with a bandage. She subsequently noticed an erythematous papulopustular rash corresponding to the shape of the bandage adhesive. Shortly thereafter, a generalized eruption developed, prompting the patient to present for evaluation 1 month later. A review of systems was negative for fevers, chills, headaches, vision changes, and joint symptoms. She denied having a history of atopy.

Physical examination revealed numerous pink papules and plaques with rupioid scale scattered over the trunk and extremities (Figure). The palms, soles, and mucous membranes were spared. Laboratory studies revealed peripheral eosinophilia (9% eosinophils [reference range, 1%-6%] and an absolute eosinophil count of 600/µL [reference range, 0-400/µL]). A 3-mm punch biopsy of a representative lesion revealed a superficial perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils along with epidermal hyperplasia, spongiosis, and mounds of parakeratosis. Clinicopathologic correlation led to the diagnosis of a rupioid id reaction secondary to an arthropod assault and/or a reaction to the bandage adhesive.

Treatment with topical corticosteroids was avoided at the patient’s request. Instead, a ceramide-based emollient and oral antihistamines (fexofenadine 180 mg in the morning and cetirizine 10 mg in the evening) were recommended and resulted in resolution of the eruption with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation at 2-week follow-up. The patient was advised to avoid further exposure to bandage adhesives.

An id reaction, or autoeczematization, is a cutaneous immunologic response to antigen(s) released from an initial, often distant site of inflammation.7,8 Clinically, it typically manifests as a pruritic, symmetrically distributed papulovesicular eruption. Although the pathogenesis of id reactions is uncertain, overactivation of T lymphocytes responding to the initial inflammatory insult has been implicated.7 A variety of noninfectious (eg, stasis dermatitis, contact dermatitis) and infectious dermatoses (eg, fungal, bacterial, viral, parasitic) may trigger id reactions.7,9-13 In this case, we believe an arthropod assault and/or reaction to the bandage adhesive was the primary insult, and the id reaction that ensued was so exuberant that it resulted not only in rupioid scale but also in peripheral eosinophilia—similar to how more severe forms of atopic dermatitis have been associated with peripheral eosinophilia.5 As such presentations of id reactions not have been widely described in the literature, this report expands our understanding of this condition to include rupioid scale and peripheral eosinophilia.

- Chung HJ, Marley-Kemp D, Keller M. Rupioid psoriasis and other skin diseases with rupioid manifestations. Cutis. 2014;94:119-121.

- Costa JB, de Sousa VLLR, da Trindade Neto PB, et al. Norwegian scabies mimicking rupioid psoriasis. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:910-913. doi:10.1590/S0365-05962012000600016

- Ip KH-K, Cheng HS, Oliver FG. Rupioid psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:859. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0451

- Wang Y, Wen Y. An AIDS patient with recurrent multiple skin crusted ulcerations. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2021;37:1-3. doi:10.1089/aid.2020.0212

- Staumont-Sallé D, Barbarot S, Bouaziz JD, et al. Effect of abrocitinib and dupilumab on eosinophil levels in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. JEADV Clin Pract. 2023;2:518-530. doi:10.1002/jvc2.192

- Savjani P. An unusual cause of eosinophilia—hypereosinophilia due to contact dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:AB168. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.685

- Bertoli M, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Autoeczematization: a strange id reaction of the skin. Cutis. 2021;108:163-166. doi:10.12788/cutis.0342

- Ilkit M, Durdu M, Karakas¸ M. Cutaneous id reactions: a comprehensive review of clinical manifestations, epidemiology, etiology, and management. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2012;38:191-202. doi:10.3109/1040841X.2011.645520

- Brenner S, Wolf R, Landau M. Scabid: an unusual id reaction to scabies. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:128-129. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1993.tb01454.x

- Jordan L, Jackson NAM, Carter-Snell B, et al. Pustular tinea id reaction. Cutis. 2019;10:E3-E4.

- Crum N, Hardaway C, Graham B. Development of an idlike reaction during treatment for acute pulmonary histoplasmosis: a new cutaneous manifestation in histoplasmosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(2 suppl):S5-S6. doi:10.1067/mjd.2003.110

- Netchiporouk E, Cohen BA. Recognizing and managing eczematous id reactions to molluscum contagiosum virus in children. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e1072-e1075. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-1054

- Choudhri SH, Magro CM, Crowson AN, et al. An id reaction to Mycobacterium leprae: first documented case. Cutis. 1994;54:282-286.

To the Editor:

In dermatology, rupioid describes dirty-appearing scale. The term is derived from the Greek word rhupos, which translates to “dirty” or “filthy.” This type of scale also is called ostraceous, owing to its resemblance to an oyster shell. Histopathologically, rupioid or ostraceous scale corresponds to epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis. Therefore, the presence of rupioid scale is believed to reflect an exuberant inflammatory response. Several dermatologic conditions have been associated with rupioid scale, including psoriasis, secondary syphilis, reactive arthritis, histoplasmosis, and Norwegian scabies.1-4 Peripheral eosinophilia has been reported in eczematous dermatoses such as atopic dermatitis and contact dermatitis,5,6 but our review of the literature did not find it described in the context of id reactions. We report the case of a patient who developed a rupioid id reaction with peripheral eosinophilia.

An otherwise healthy 40-year-old woman presented with a generalized pruritic eruption of 1 month’s duration. Prior to onset, she was bitten by a bug on the left arm and covered the site with a bandage. She subsequently noticed an erythematous papulopustular rash corresponding to the shape of the bandage adhesive. Shortly thereafter, a generalized eruption developed, prompting the patient to present for evaluation 1 month later. A review of systems was negative for fevers, chills, headaches, vision changes, and joint symptoms. She denied having a history of atopy.

Physical examination revealed numerous pink papules and plaques with rupioid scale scattered over the trunk and extremities (Figure). The palms, soles, and mucous membranes were spared. Laboratory studies revealed peripheral eosinophilia (9% eosinophils [reference range, 1%-6%] and an absolute eosinophil count of 600/µL [reference range, 0-400/µL]). A 3-mm punch biopsy of a representative lesion revealed a superficial perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils along with epidermal hyperplasia, spongiosis, and mounds of parakeratosis. Clinicopathologic correlation led to the diagnosis of a rupioid id reaction secondary to an arthropod assault and/or a reaction to the bandage adhesive.

Treatment with topical corticosteroids was avoided at the patient’s request. Instead, a ceramide-based emollient and oral antihistamines (fexofenadine 180 mg in the morning and cetirizine 10 mg in the evening) were recommended and resulted in resolution of the eruption with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation at 2-week follow-up. The patient was advised to avoid further exposure to bandage adhesives.

An id reaction, or autoeczematization, is a cutaneous immunologic response to antigen(s) released from an initial, often distant site of inflammation.7,8 Clinically, it typically manifests as a pruritic, symmetrically distributed papulovesicular eruption. Although the pathogenesis of id reactions is uncertain, overactivation of T lymphocytes responding to the initial inflammatory insult has been implicated.7 A variety of noninfectious (eg, stasis dermatitis, contact dermatitis) and infectious dermatoses (eg, fungal, bacterial, viral, parasitic) may trigger id reactions.7,9-13 In this case, we believe an arthropod assault and/or reaction to the bandage adhesive was the primary insult, and the id reaction that ensued was so exuberant that it resulted not only in rupioid scale but also in peripheral eosinophilia—similar to how more severe forms of atopic dermatitis have been associated with peripheral eosinophilia.5 As such presentations of id reactions not have been widely described in the literature, this report expands our understanding of this condition to include rupioid scale and peripheral eosinophilia.

To the Editor:

In dermatology, rupioid describes dirty-appearing scale. The term is derived from the Greek word rhupos, which translates to “dirty” or “filthy.” This type of scale also is called ostraceous, owing to its resemblance to an oyster shell. Histopathologically, rupioid or ostraceous scale corresponds to epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis. Therefore, the presence of rupioid scale is believed to reflect an exuberant inflammatory response. Several dermatologic conditions have been associated with rupioid scale, including psoriasis, secondary syphilis, reactive arthritis, histoplasmosis, and Norwegian scabies.1-4 Peripheral eosinophilia has been reported in eczematous dermatoses such as atopic dermatitis and contact dermatitis,5,6 but our review of the literature did not find it described in the context of id reactions. We report the case of a patient who developed a rupioid id reaction with peripheral eosinophilia.

An otherwise healthy 40-year-old woman presented with a generalized pruritic eruption of 1 month’s duration. Prior to onset, she was bitten by a bug on the left arm and covered the site with a bandage. She subsequently noticed an erythematous papulopustular rash corresponding to the shape of the bandage adhesive. Shortly thereafter, a generalized eruption developed, prompting the patient to present for evaluation 1 month later. A review of systems was negative for fevers, chills, headaches, vision changes, and joint symptoms. She denied having a history of atopy.