User login

Factors Influencing Outcomes of a Telehealth-Based Physical Activity Program in Older Veterans Postdischarge

Factors Influencing Outcomes of a Telehealth-Based Physical Activity Program in Older Veterans Postdischarge

Deconditioning among hospitalized older adults contributes to significant decline in posthospitalization functional ability, physical performance, and physical activity.1-10 Previous hospital-to-home interventions have targeted improving function and physical activity, including recent programs leveraging home telehealth as a feasible and potentially effective mode of delivering in-home exercise and rehabilitation.11-14 However, pilot interventions have shown mixed effectiveness.11,12,14 This study expands on a previously published intervention describing a pilot home telehealth program for veterans posthospital discharge that demonstrated significant 6-month improvement in physical activity as well as trends in physical function improvement, including among those with cognitive impairment.15 Factors that contribute to improved outcomes are the focus of the present study.

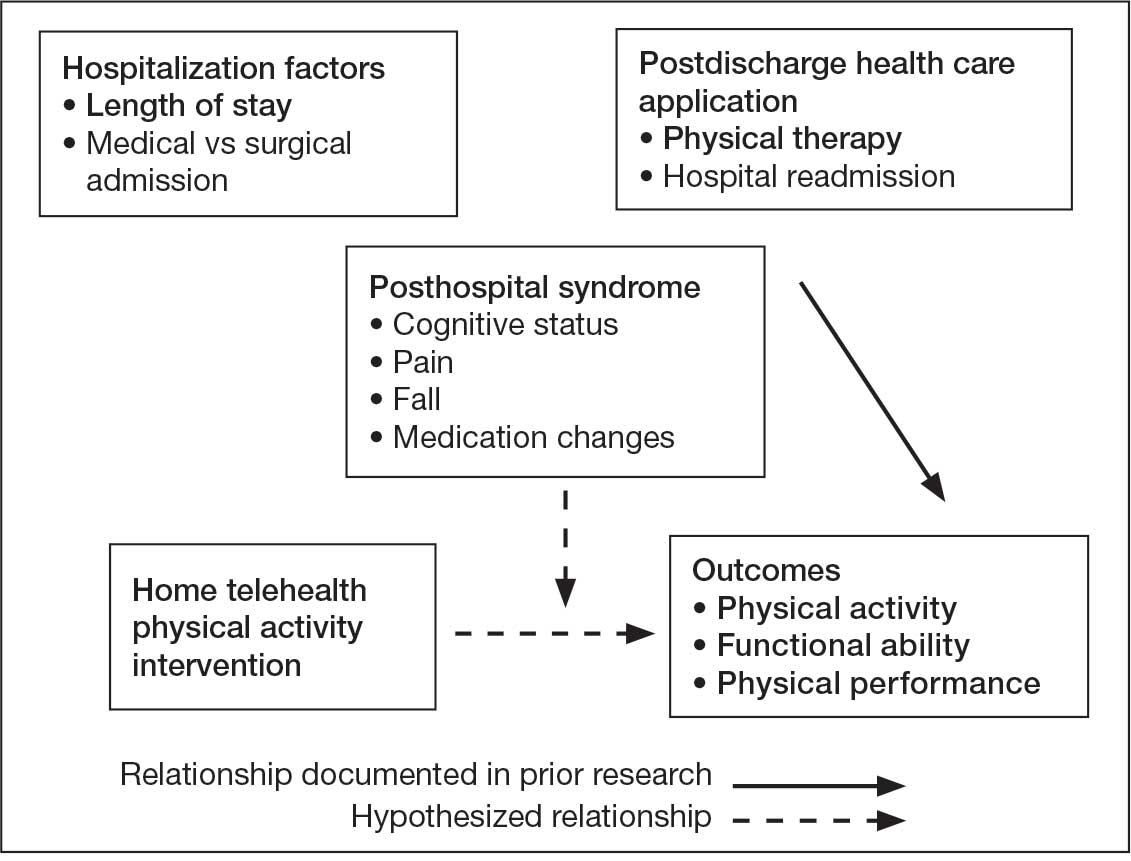

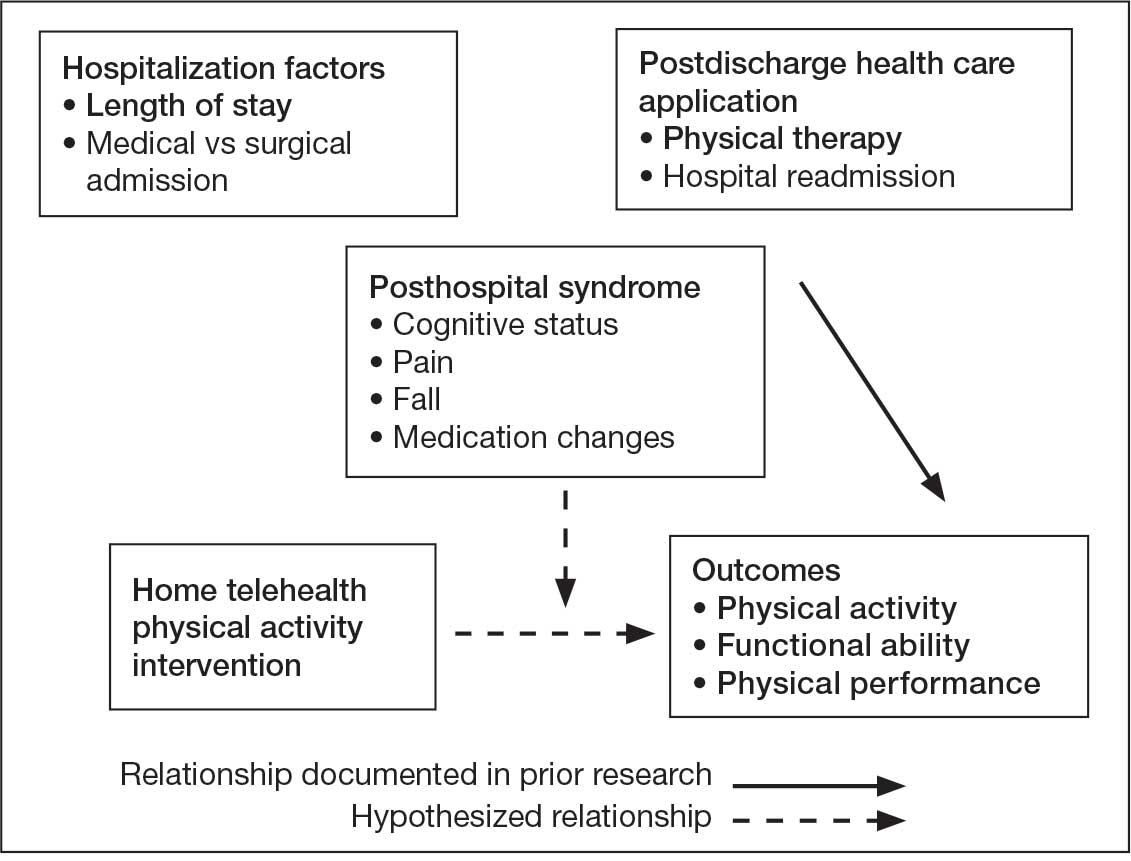

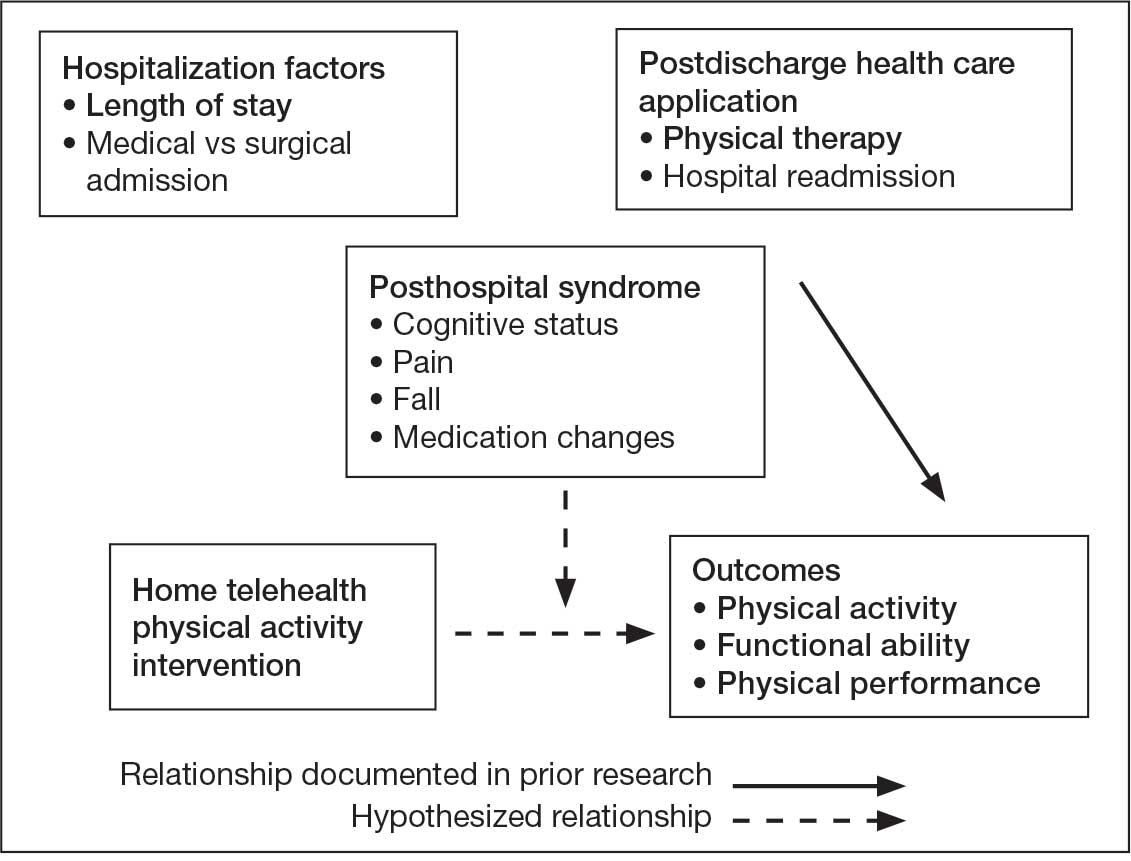

Key factors underlying the complexity of hospital-to-home transitions include hospitalization elements (ie, reason for admission and length of stay), associated posthospital syndromes (ie, postdischarge falls, medication changes, cognitive impairment, and pain), and postdischarge health care application (ie, physical therapy and hospital readmission).16-18 These factors may be associated with postdischarge functional ability, physical performance, and physical activity, but their direct influence on intervention outcomes is unclear (Figure 1).5,7,9,16-20 The objective of this study was to examine the influence of hospitalization, posthospital syndrome, and postdischarge health care application factors on outcomes of a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Video Connect (VVC) intervention to enhance function and physical activity in older adults posthospital discharge.

health care application factors on physical activity, functional ability, and

physical performance intervention outcomes.

Methods

The previous analysis reported on patient characteristics, program feasibility, and preliminary outcomes.13,15 The current study reports on relationships between hospitalization, posthospital syndrome, and postdischarge health care application factors and change in key outcomes, namely postdischarge self-reported functional ability, physical performance, and physical activity from baseline to endpoint.

Participants provided written informed consent. The protocol and consent forms were approved by the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System (VAAAHS) Research and Development Committee, and the project was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04045054).

Intervention

The pilot program targeted older adults following recent hospital discharge from VAAAHS. Participants were eligible if they were aged ≥ 50 years, had been discharged following an inpatient stay in the past 1 to 2 weeks, evaluated by physical therapy during hospitalization with stated rehabilitation goals on discharge, and followed by a VAAAHS primary care physician. Participants were either recruited during hospital admission or shortly after discharge.13

An experienced physical activity trainer (PAT) supported the progression of participants’ rehabilitation goals via a home exercise program and coached the patient and caregiver to optimize functional ability, physical performance, and physical activity. The PAT was a nonlicensed research assistant with extensive experience in applying standard physical activity enhancement protocols (eg, increased walking) to older adults with comorbidities. Participation in the program lasted about 6 months. Initiation of the PAT program was delayed if the patient was already receiving postdischarge home-based or outpatient physical therapy. The PAT contacted the patient weekly via VVC for the first 6 weeks, then monthly for a total of 6 months. Each contact included information on optimal walking form, injury prevention, program progression, and ways to incorporate sit-to-stand transitions, nonsitting behavior, and walking into daily routines. The initial VVC contact lasted about 60 minutes and subsequent sessions lasted about 30 minutes.13

Demographic characteristics were self-reported by participants and included age, sex, race, years of education, and marital status. Clinical characteristics were obtained from each participant’s electronic health record (EHR), including copay status, index hospitalization length of stay, admission diagnosis, and postsurgery status (postsurgery vs nonpostsurgery). Intervention adherence was tracked as the number of PAT sessions attended.

Posthospital Syndrome Factors

Participant falls (categorized as those who reported a fall vs those who did not) and medication changes (number of changes reported, including new medication, discontinued medication, dose changes, medication changes, or changes in medication schedule) were reported by participants or caregivers during each VVC contact. Participants completed the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) at baseline, and were dichotomized into 2 groups: no cognitive impairment (MoCA score ≥ 26) and mild to moderate cognitive impairment (MoCA score 10-25).13,21

Participants rated how much pain interfered with their normal daily activities since the previous VVC session on a 5-point Likert scale (1, not at all; to 5, extremely).22 Similar to prior research, participants were placed into 2 groups based on their mean pain interference score (individuals with scores from 1.0 to 2.0 in 1 group, and individuals with > 2.0 in another).23-25 Participants were separated into a no or mild pain interference group and a moderate to severe pain interference group. Hospital readmissions (VA and non-VA) and postdischarge physical therapy outcomes were obtained from the participant’s EHR, including primary care visits.

Outcomes

Outcomes were collected at baseline (posthospital discharge) and 6 months postenrollment.

Self-Reported Functional Ability. This measure is provided by participants or caregivers and measured by the Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living (ADL), Lawton and Brody Instrumental ADL Scale (IADL), Nagi Disability Model, and Rosow-Breslau Scale. The Katz ADL assesses the ability to complete 6 self-care activities and awards 1 point for independence and 0 if the individual is dependent (total score range, 0-6).26 The Lawton and Brody IADL measures an individual’s independence in 8 instrumental ADLs; it awards 1 point for independence and 0 if the individual is dependent (total score range, 0-8).27 The Nagi Disability Model evaluates an individual’s difficulty performing 5 tasks (total score range, 0-5) and tallies the number of items with a response other than “no difficulty at all” (higher total score indicates greater difficulty). 28 The Rosow-Breslau Scale is a 3-item measure of mobility disability; individual responses are 0 (no help) and 1 (requires help or unable); higher total score (range, 0-3) indicates greater disability.29

Physical Performance. Measured using the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), which evaluates standing balance, sit to stand, and walking performance. Scores range from 0 to 4 on the balance, gait speed, and chair stand tests, for a total composite score between 0 and 12 (higher score indicates better performance).30

Physical Activity. Measured using actigraphy, namely a physical activity monitor adherent to the thigh (activ-PAL3TM, PAL Technologies Ltd., Glasgow, UK).31 Participants were instructed to wear the activPal for ≥ 1 week. Participants with a minimum of 5 days of wear were included in this analysis.

Data Analyses

Analyses were performed using SPSS software version 29.0.32 Continuous variables were summarized using mean (SD) or median and IQR using the weighted average method; categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages. Baseline scores on outcome variables were compared by categorical hospitalization, posthospital syndrome, and postdischarge health care application factor variables using Mann-Whitney U tests. The differences between outcome variables from baseline to endpoint were then calculated to produce change scores. Relationships between the number of PAT sessions attended and baseline outcomes and outcome change scores were estimated using Spearman correlations. Relationships between categorical factors (hospitalization, posthospital syndrome, and postdischarge health care application) and outcome variable change scores (which were normally distributed) were examined using Mann-Whitney U tests. Relationships with continuous hospitalization (length of stay) and posthospital syndrome factors (medication changes) were estimated using Spearman correlations. Effect sizes (ES) were estimated with Cohen d; small (d = 0.2), medium (d = 0.5), or large (d ≥ 0.8). Missing data were handled using pairwise deletion.33 Therefore, sample sizes were reported for each analysis. For all statistical tests, P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

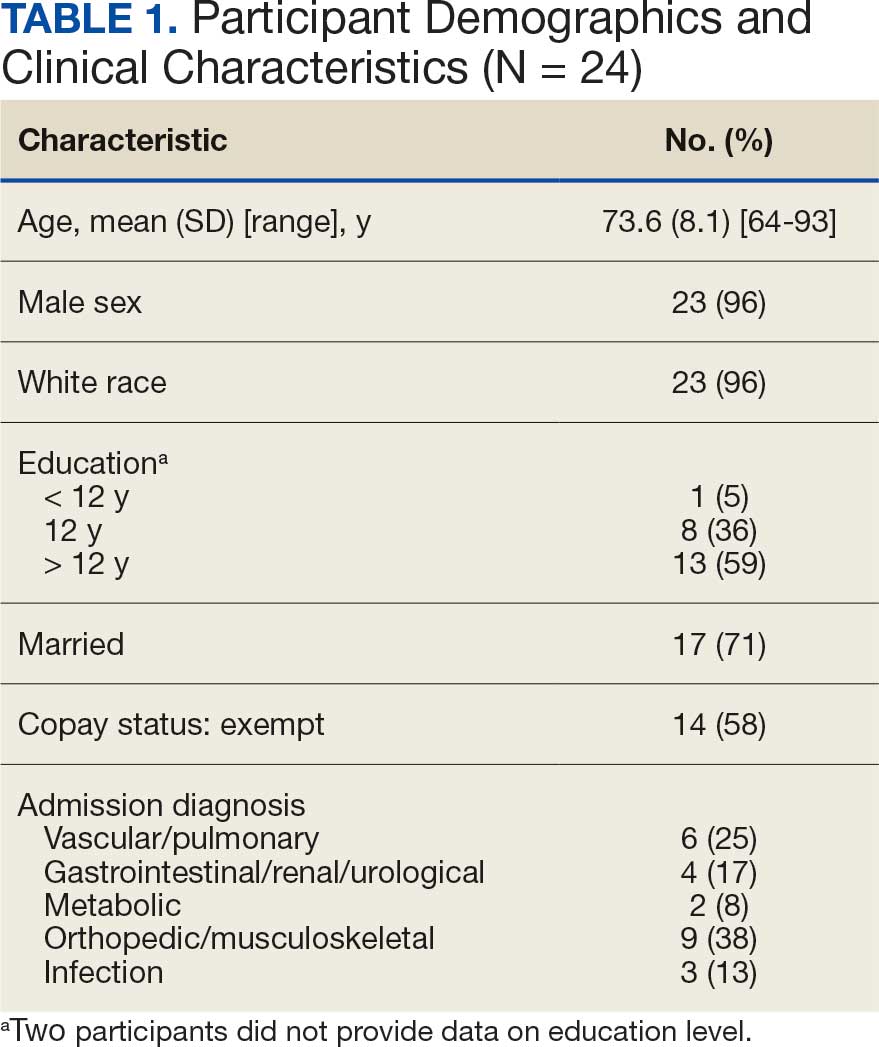

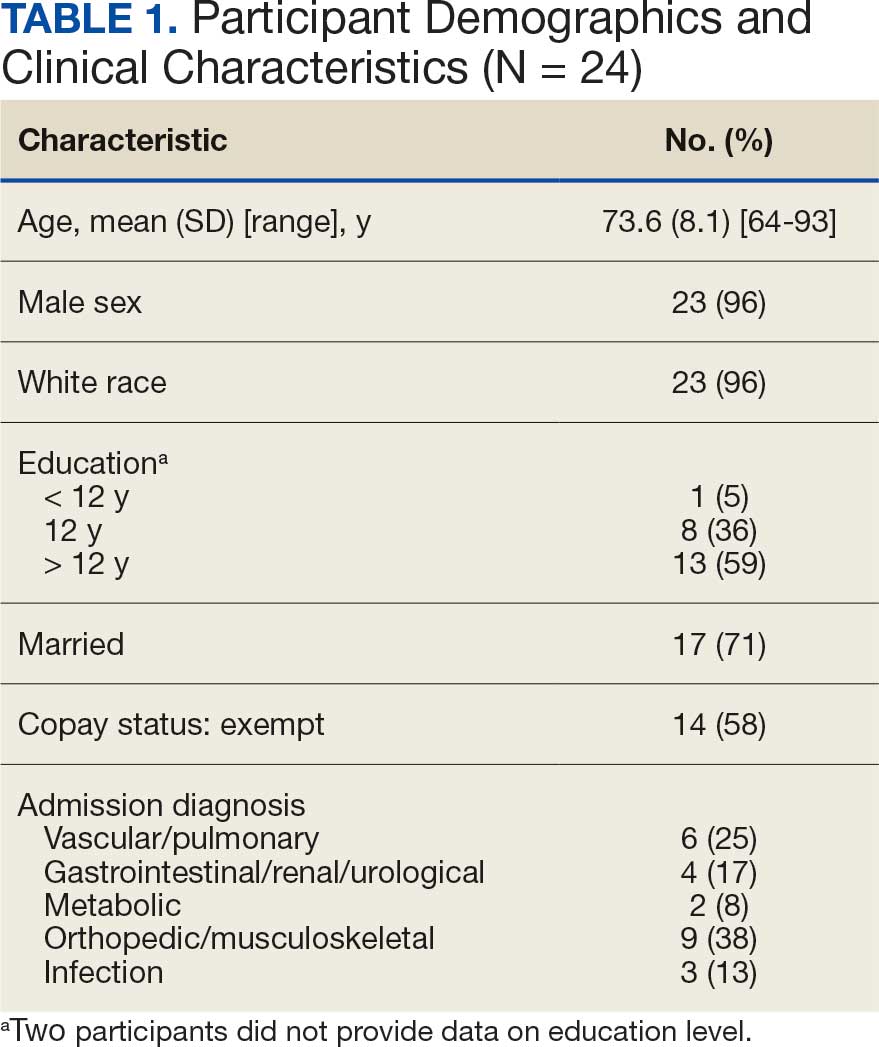

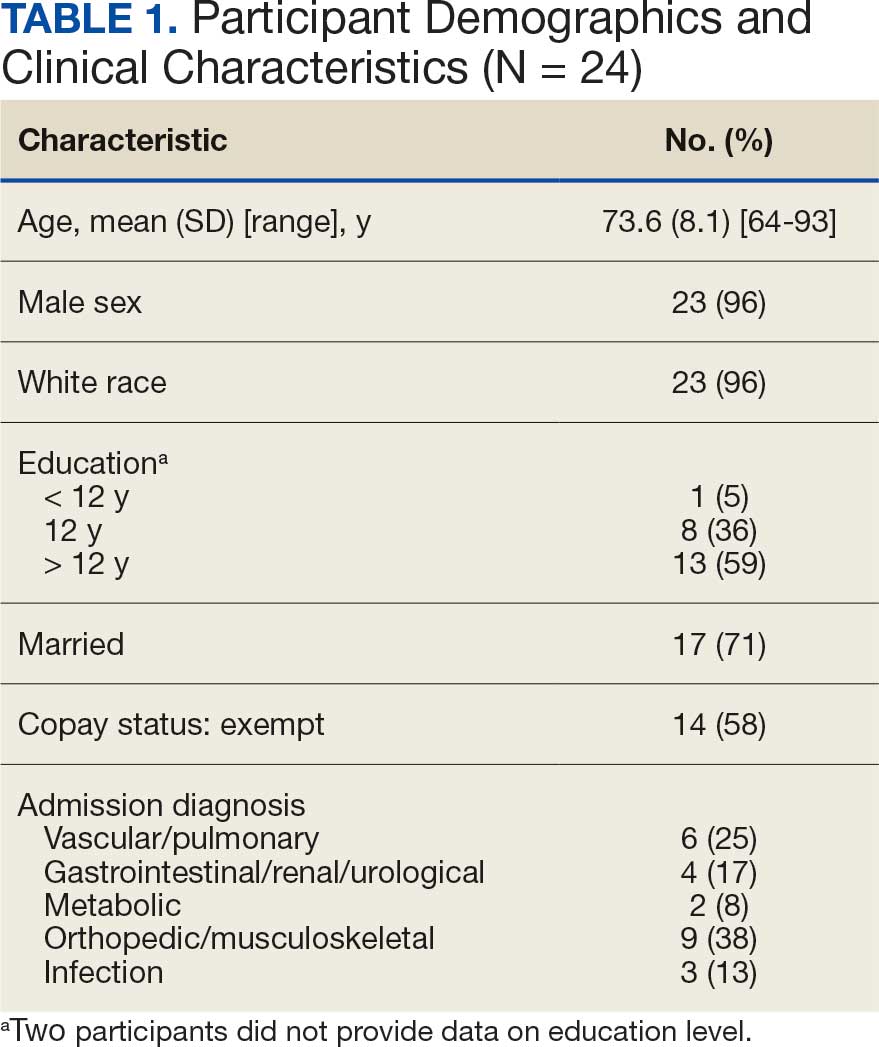

Twenty-four individuals completed the pilot intervention.15 Mean (SD) age was 73.6 (8.1) years (range, 64-93 years) and participants were predominantly White males (Table 1). Eight participants had a high school education only and 13 had more than a high school education. Diagnoses at admission included 9 patients with orthopedic/musculoskeletal conditions (6 were for joint replacement), 6 patients with vascular/pulmonary conditions, and 4 with gastrointestinal/renal/urological conditions. Of the 11 postsurgery participants, 7 were orthopedic, 4 were gastrointestinal, and 1 was peripheral vascular.

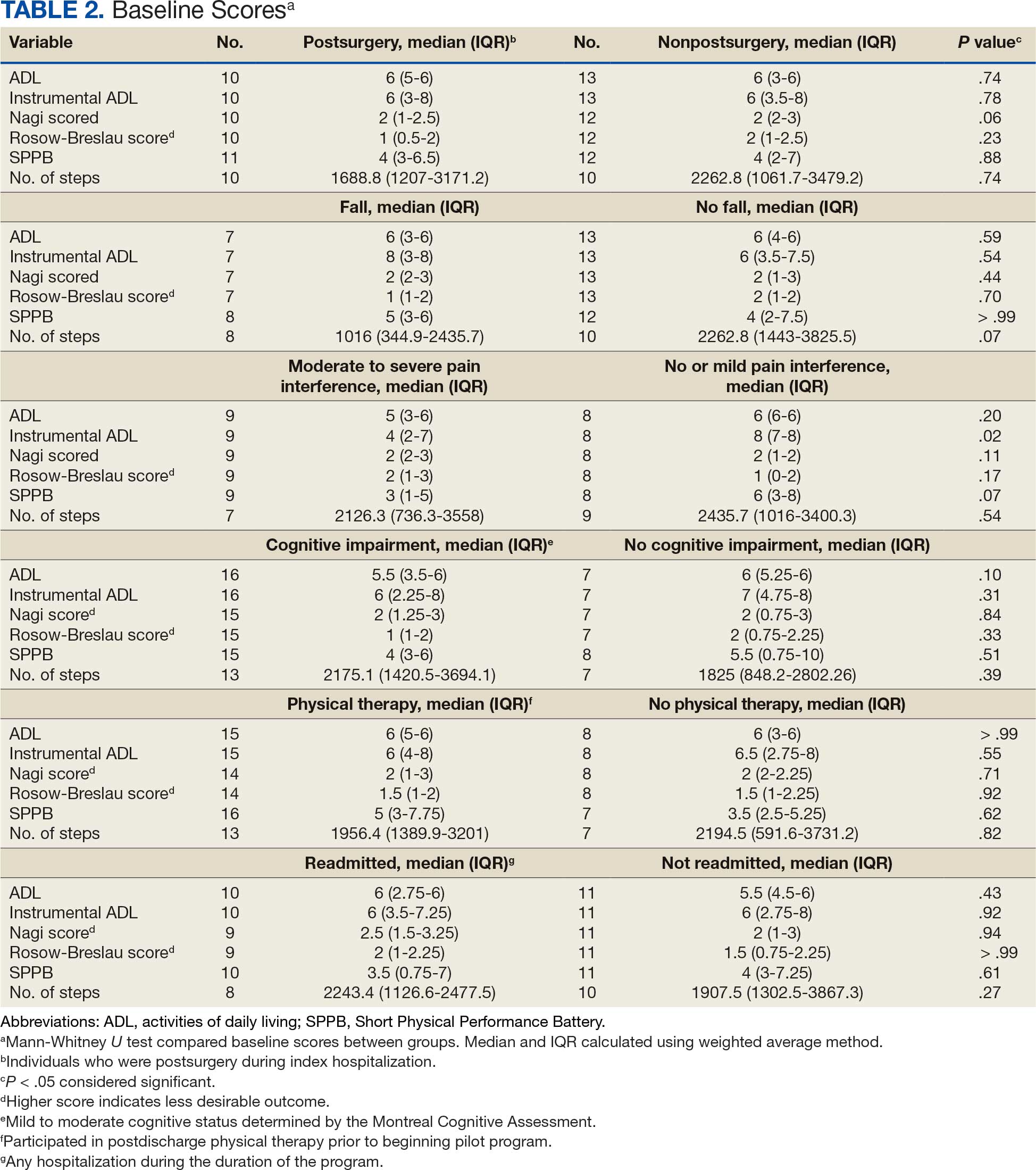

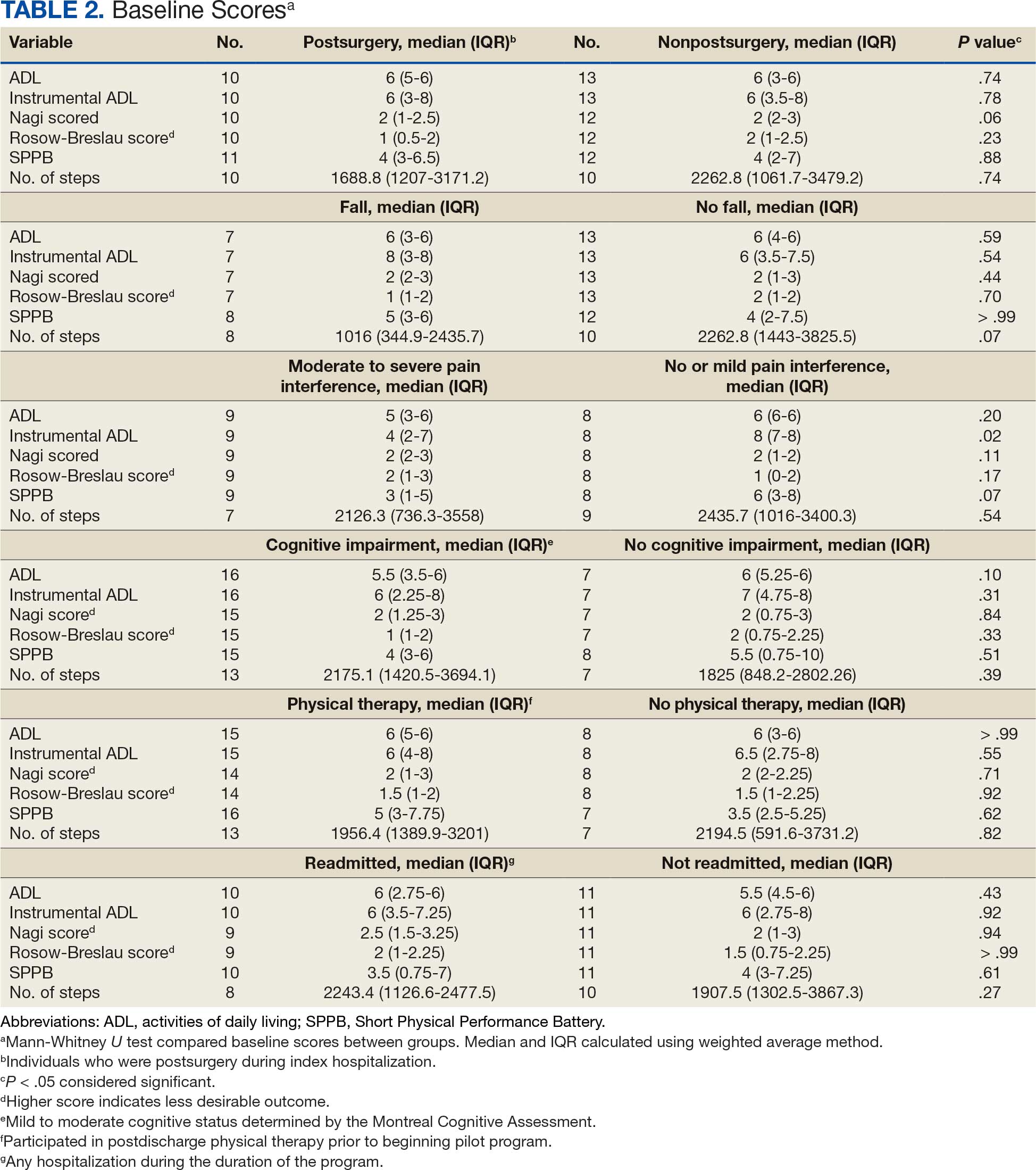

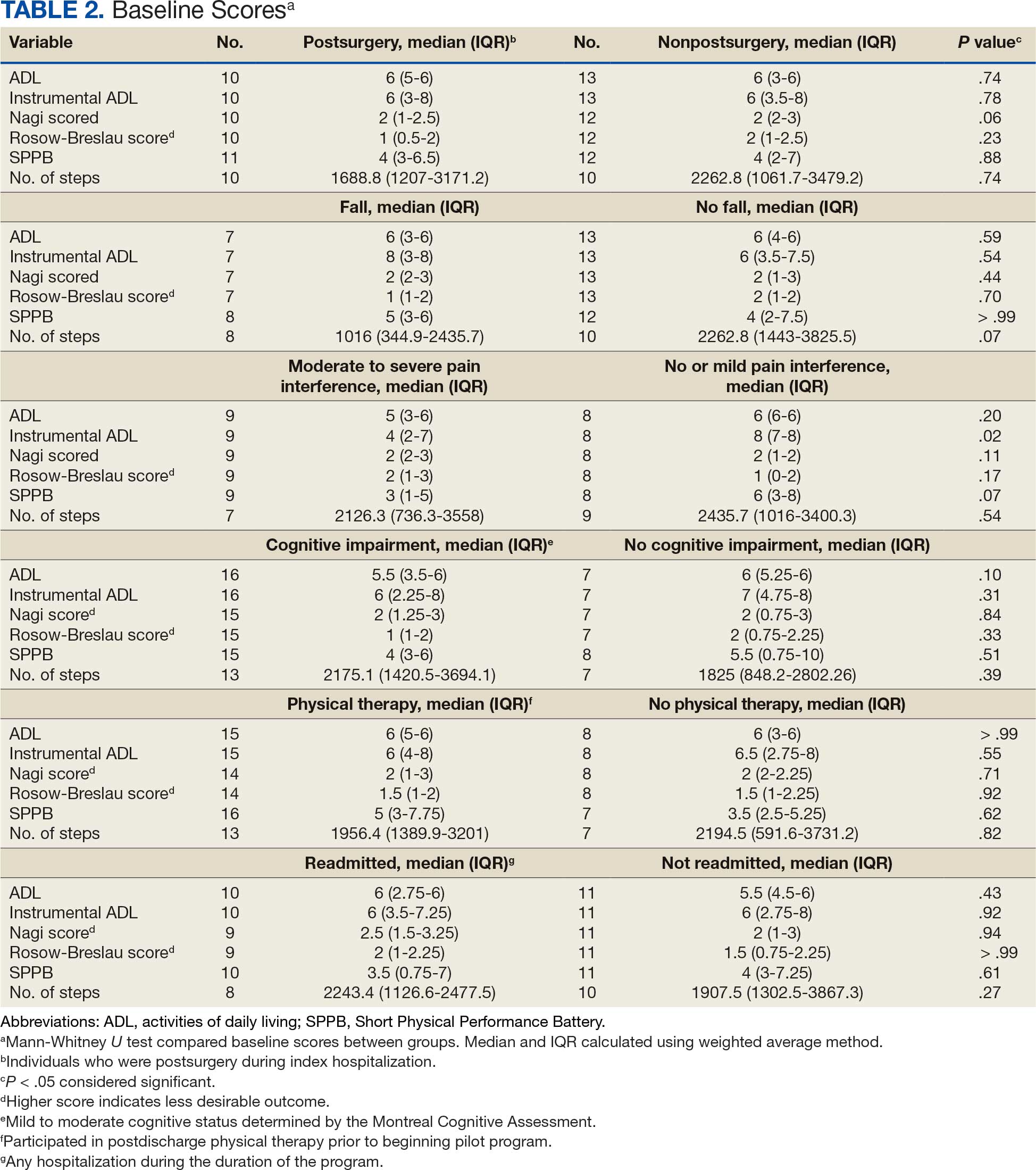

Baseline outcome scores did not differ significantly between groups, except individuals with moderate to severe pain interference reported a significantly lower IADL score (median [IQR] 4 [2-7]) than individuals with mild or moderate pain interference (median [IQR] 8 [7-8]; P = .02) (Table 2). The mean (SD) number of PAT sessions attended was 9.3 (3.7) (range, 3-19). There were no significant relationships between number of sessions attended and any baseline outcome variables or outcome change scores.

Hospitalization Factors

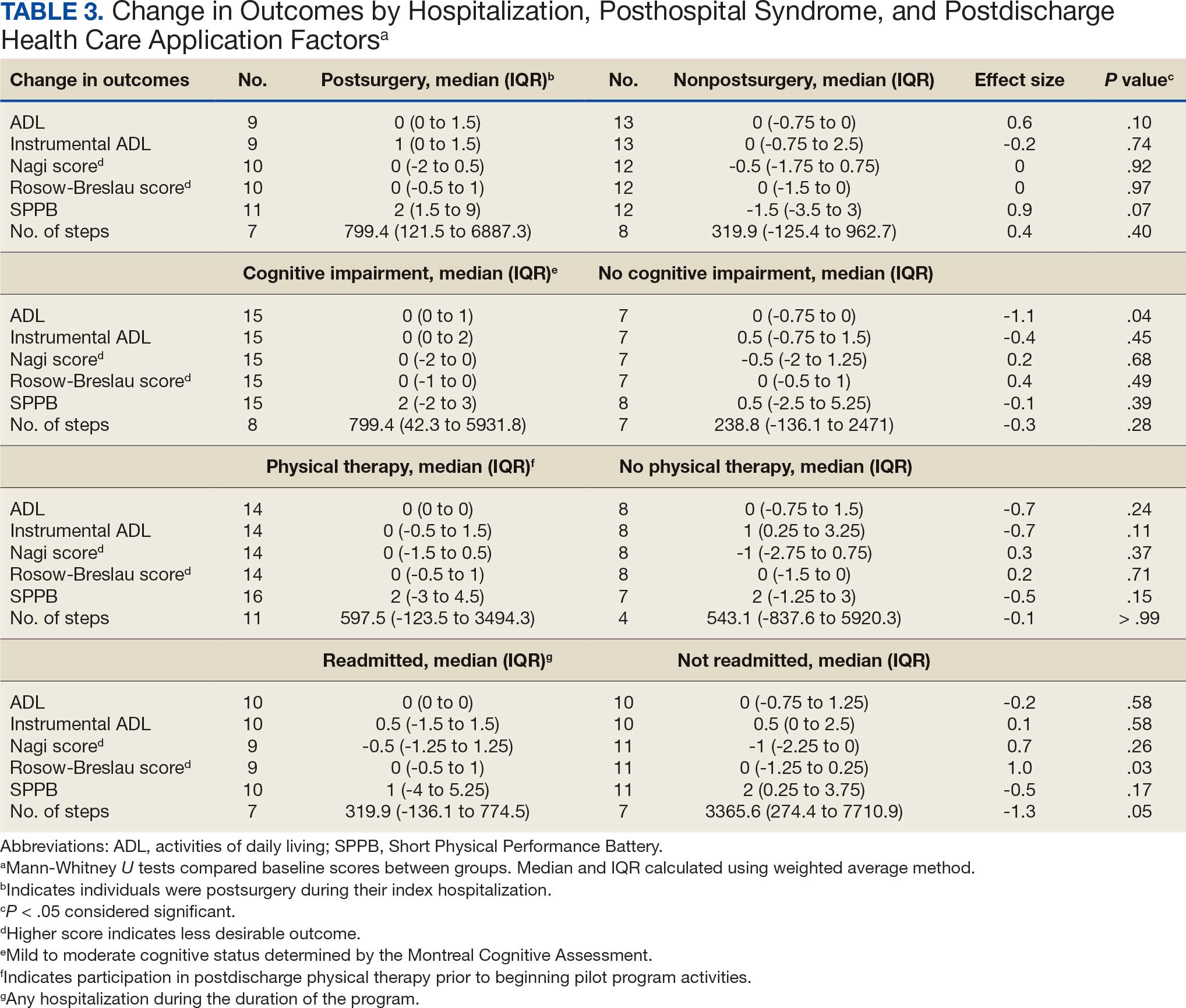

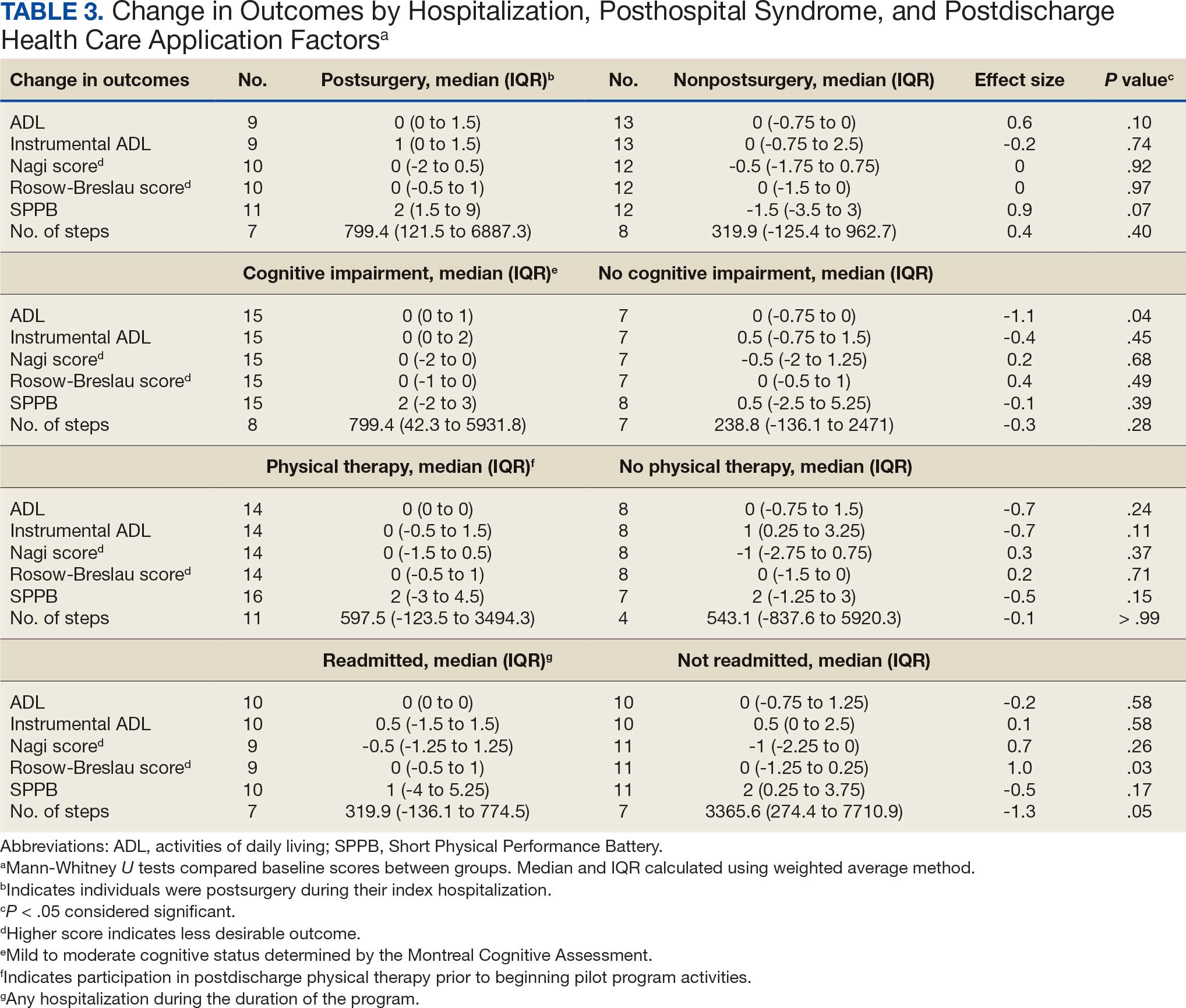

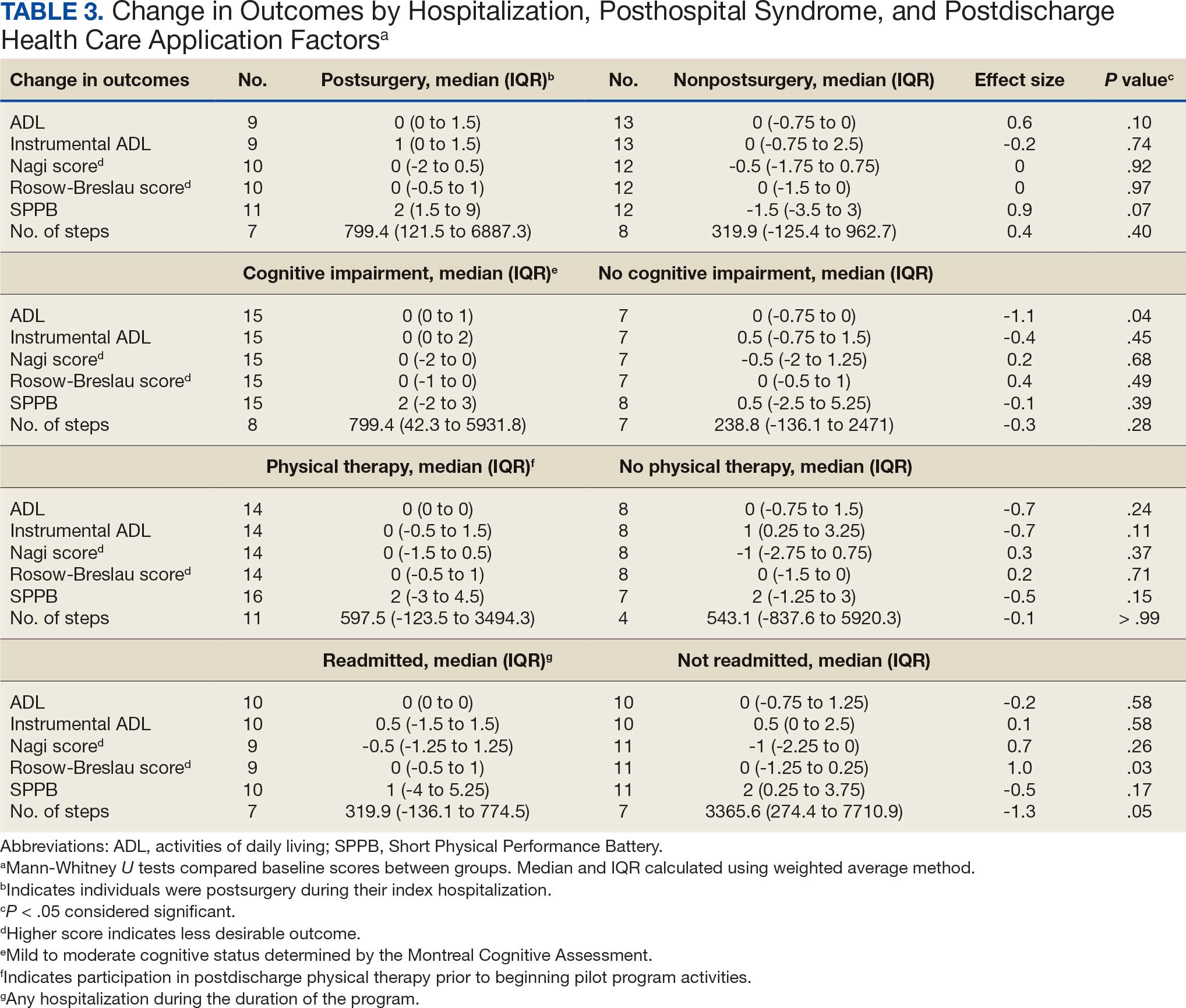

Participants who were postsurgery tended to have greater improvement than individuals who were nonpostsurgery in ADLs (median [IQR] 0 [0-1.5]; ES, 0.6; P = .10) and SPPB (median [IQR] 2 [1.5-9]; ES, 0.9; P = .07), but the improvements were not statistically significant (Table 3). Mean (SD) length of stay of the index hospitalization was 6.7 (6.1) days. Longer length of stay was significantly correlated with an increase in Nagi score (ρ, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.01-0.75). There were no other significant or trending relationships between length of stay and outcome variables.

Posthospital Syndrome Factors

The 16 participants with mild to moderate cognitive impairment had less improvement in ADLs (median [IQR] 0 [0-1]) than the 8 participants with no impairment (median [IQR] 0 [-0.75 to 0]; ES, -1.1; P = .04). Change in outcome variables from baseline to endpoint did not significantly differ between the 8 patients who reported a fall compared with the 13 who did not, nor were any trends observed. Change in outcome variables from baseline to endpoint also did not significantly differ between the 8 participants who reported no or mild pain interference compared with the 10 patients with moderate to severe pain interference, nor were any trends observed. Mean (SD) number of medication changes was 2.5 (1.6). Higher number of medication changes was significantly correlated with a decrease in Rosow-Breslau score (ρ, -0.47; 95% CI, -0.76 to -0.02). There were no other significant or trending relationships between number of medication changes and outcome variables.

Postdischarge Health Care Application Factors

The 16 participants who attended posthospital physical therapy trended towards less improvement in IADLs (median [IQR] 0 [-0.5 to 1.5]; ES, -0.7; P = .11) and SPPB (median [IQR] 2 [-3.0 to 4.5]; ES, -0.5; P = .15) than the 8 patients with no postdischarge physical therapy. Eleven participants were readmitted, while 13 had no readmissions in their medical records between baseline and endpoint. Participants with ≥ 1 readmission experienced a greater increase in Rosow-Breslau score (median [IQR] 0 [-0.5 to 1.0]) than those not readmitted (median [IQR] 0 [-1.25 to 0.25]; ES, 1.0; P = .03). Borderline greater improvement in number of steps was found in those not readmitted (median [IQR] 3365.6 [274.4-7710.9]) compared with those readmitted (median [IQR] 319.9 [-136.1 to 774.5]; ES, -1.3; P = .05). Patients who were readmitted also tended to have lower and not statistically significant improvements in SPPB (median [IQR] 1 [-4.0 to 5.3]) compared with those not readmitted (median [IQR] 2 [0.3-3.8]; ES, -0.5; P = .17) (Table 3).

Discussion

This study examined the association between hospitalization, posthospital syndrome, and postdischarge health care use in patients undergoing a VVC-based intervention following hospital discharge. Participants who had no or mild cognitive impairment, no readmissions, higher medication changes, and a shorter hospital length of stay tended to experience lower disability, including in mobility and ADLs. This suggests individuals who are less clinically complex may be more likely to benefit from this type of virtual rehabilitation program. These findings are consistent with clinical experiences; home-based programs to improve physical activity posthospital discharge can be challenging for those who were medically ill (and did not undergo a specific surgical procedure), cognitively impaired, and become acutely ill and trigger hospital readmission. 15 For example, the sample in this study had higher rates of falls, pain, and readmissions compared to previous research.2,3,34-39

The importance of posthospital syndrome in the context of recovery of function and health at home following hospitalization is well documented.16-18 The potential impact of posthospital syndrome on physical activity-focused interventions is less understood. In our analysis, participants with mild or moderate cognitive impairment tended to become more dependent in their ADLs, while those with no cognitive impairment tended to become more independent in their ADLs. This functional decline over time is perhaps expected in persons with cognitive impairment, but the significant difference with a large ES warrants further consideration on how to tailor interventions to better promote functional recovery in these individuals.40,41 While some cognitive decline may not be preventable, this finding supports the need to promote healthy cognitive aging, identify declines in cognition, and work to mitigate additional decline. Programs specifically designed to promote function and physical activity in older adults with cognitive impairment are needed, especially during care transitions.41-43

While participants reported that falls and pain interference did not have a significant impact on change in outcomes between baseline and endpoint, these areas need further investigation. Falls and pain have been associated with function and physical activity in older adults.42-46 Pain is common, yet underappreciated during older adult hospital-to-home transitions.11,12,45,46 There is a need for more comprehensive assessment of pain (including pain intensity) and qualitative research.

Hospitalization and postdischarge health care application factors may have a significant impact on home-telehealth physical activity intervention success. Individuals who were postsurgery tended to have greater improvements in ADLs and physical performance. Most postsurgery participants had joint replacement surgery. Postsurgery status may not be modifiable, but it is important to note expected differences in recovery between medical and surgical admissions and the need to tailor care based on admission diagnosis. Those with a longer length of hospital stay may be considered at higher risk of suboptimal outcomes postdischarge, which indicates an opportunity for targeting resources and support, in addition to efforts of reducing length of stay where possible.47

Readmissions were significantly related to a change in Rosow-Breslau mobility disability score. This may indicate the detrimental impact a readmission can have on increasing mobility and physical activity postdischarge, or the potential of this pilot program to impact readmissions by increasing mobility and physical activity, contrary to prior physical exercise interventions.5,7,9,48 With 5% to 79% of readmissions considered preventable, continued efforts and program dissemination and implementation to address preventable readmissions are warranted.49 Individuals with postdischarge physical therapy (prior to beginning the pilot program) tended to demonstrate less improvement in disability and physical performance. This relationship needs further investigation; the 2 groups did not appear to have significant differences at baseline, albeit with a small sample size. It is possible they experienced initial improvements with postdischarge physical therapy and plateaued or had little further reserve to improve upon entering the VVC program.

Strengths and Limitations

This pilot program provided evaluative data on the use of VVC to enhance function and physical activity in older adults posthospital discharge. It included individual (eg, fall, pain, cognitive impairment) and health service (eg, readmission, physical therapy) level factors as predictors of function and physical activity posthospitalization.5,7,9,15-19

The results of this pilot project stem from a small sample lacking diversity in terms of race, ethnicity, and sex. There was some variation in baseline and endpoints between participants, and when hospitalization, posthospital syndrome, and postdischarge health care application factors were collected. The majority of participants were recruited within a month postdischarge, and the program lasted about 6 months. Data collection was attempted at regular PAT contacts, but there was some variation in when visits occurred based on participant availability and preference. Some participants had missing data, which was handled using pairwise deletion.33 Larger studies are needed to confirm the findings of this study, particularly the trends that did not reach statistical significance. Home health services other than physical therapy (eg, nursing, occupational therapy) were not fully accounted for and should be considered in future research.

Conclusions

In patients undergoing a 6-month pilot VVC-based physical activity intervention posthospital discharge, improvements in mobility and disability were most likely in those who had no cognitive impairment and were not readmitted. Larger sample and qualitative investigations are necessary to optimize outcomes for patients who meet these clinical profiles.

- Liebzeit D, Bratzke L, Boltz M, Purvis S, King B. Getting back to normal: a grounded theory study of function in post-hospitalized older adults. Gerontologist. 2020;60:704-714. doi:10.1093/geront/gnz057

- Ponzetto M, Zanocchi M, Maero B, et al. Post-hospitalization mortality in the elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2003;36:83-91. doi:10.1016/s0167-4943(02)00061-4

- Buurman BM, Hoogerduijn JG, de Haan RJ, et al. Geriatric conditions in acutely hospitalized older patients: prevalence and one-year survival and functional decline. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26951. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026951

- Ponzetto M, Maero B, Maina P, et al. Risk factors for early and late mortality in hospitalized older patients: the continuing importance of functional status. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:1049-1054. doi:10.1093/gerona/58.11.m1049

- Huang HT, Chang CM, Liu LF, Lin HS, Chen CH. Trajectories and predictors of functional decline of hospitalised older patients. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22:1322-1331. doi:10.1111/jocn.12055

- Boyd CM, Landefeld CS, Counsell SR, et al. Recovery of activities of daily living in older adults after hospitalization for acute medical illness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:2171- 2179. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02023.x

- Helvik AS, Selbæk G, Engedal K. Functional decline in older adults one year after hospitalization. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;57:305-310. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2013.05.008

- Zaslavsky O, Zisberg A, Shadmi E. Impact of functional change before and during hospitalization on functional recovery 1 month following hospitalization. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70:381-386. doi:10.1093/gerona/glu168

- Chen CC, Wang C, Huang GH. Functional trajectory 6 months posthospitalization: a cohort study of older hospitalized patients in Taiwan. Nurs Res. 2008;57:93-100. doi:10.1097/01.NNR.0000313485.18670.e2

- Kleinpell RM, Fletcher K, Jennings BM. Reducing functional decline in hospitalized elderly. In: Hughes RG, ed. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008. Accessed September 3, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2629/

- Liebzeit D, Rutkowski R, Arbaje AI, Fields B, Werner NE. A scoping review of interventions for older adults transitioning from hospital to home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:2950-2962. doi:10.1111/jgs.17323

- Hladkowicz E, Dumitrascu F, Auais M, et al. Evaluations of postoperative transitions in care for older adults: a scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22:329. doi:10.1186/s12877-022-02989-6

- Alexander NB, Phillips K, Wagner-Felkey J, et al. Team VA Video Connect (VVC) to optimize mobility and physical activity in post-hospital discharge older veterans: baseline assessment. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21:502. doi:10.1186/s12877-021-02454-w

- Dawson R, Oliveira JS, Kwok WS, et al. Exercise interventions delivered through telehealth to improve physical functioning for older adults with frailty, cognitive, or mobility disability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Telemed J E Health. 2024;30:940-950. doi:10.1089/tmj.2023.0177

- Liebzeit D, Phillips KK, Hogikyan RV, Cigolle CT, Alexander NB. A pilot home-telehealth program to enhance functional ability, physical performance, and physical activity in older adult veterans post-hospital discharge. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2024;17:271-279. doi:10.3928/19404921-20241105-01

- Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome—an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:100-102. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1212324

- Caraballo C, Dharmarajan K, Krumholz HM. Post hospital syndrome: is the stress of hospitalization causing harm? Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2019;72:896-898. doi:10.1016/j.rec.2019.04.010

- Rawal S, Kwan JL, Razak F, et al. Association of the trauma of hospitalization with 30-day readmission or emergency department visit. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:38- 45. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5100

- Dutzi I, Schwenk M, Kirchner M, Jooss E, Bauer JM, Hauer K. Influence of cognitive impairment on rehabilitation received and its mediating effect on functional recovery. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;84:745-756. doi:10.3233/JAD-210620

- Uriz-Otano F, Uriz-Otano JI, Malafarina V. Factors associated with short-term functional recovery in elderly people with a hip fracture. Influence ofcognitiveimpairment. JAmMedDirAssoc. 2015;16:215-220. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2014.09.009

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695-699. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

- Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473-483.

- White RS, Jiang J, Hall CB, et al. Higher perceived stress scale scores are associated with higher pain intensity and pain interference levels in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:2350-2356. doi:10.1111/jgs.13135

- Blyth FM, March LM, Brnabic AJ, et al. Chronic pain in Australia: a prevalence study. Pain. 2001;89:127-134. doi:10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00355-9

- Thomas E, Peat G, Harris L, Wilkie R, Croft PR. The prevalence of pain and pain interference in a general population of older adults: cross-sectional findings from the North Staffordshire Osteoarthritis Project (NorStOP). Pain. 2004;110:361-368. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2004.04.017

- Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914-919. doi:10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016

- Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179-186.

- Alexander NB, Guire KE, Thelen DG, et al. Self-reported walking ability predicts functional mobility performance in frail older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1408-1413. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02630.x

- Rosow I, Breslau N. A Guttman health scale for the aged. J Gerontol. 1966;21:556-559. doi:10.1093/geronj/21.4.556

- Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M85-M94. doi:10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85

- Chan CS, Slaughter SE, Jones CA, Ickert C, Wagg AS. Measuring activity performance of older adults using the activPAL: a rapid review. Healthcare (Basel). 2017;5:94. doi:10.3390/healthcare5040094

- IBM SPSS software. IBM Corp; 2019. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.ibm.com/spss

- Kang H. The prevention and handling of the missing data. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2013;64:402-406. doi:10.4097/kjae.2013.64.5.402

- Epstein AM, Jha AK, Orav EJ. The relationship between hospital admission rates and rehospitalizations. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2287-2295. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1101942

- Bogaisky M, Dezieck L. Early hospital readmission of nursing home residents and community-dwelling elderly adults discharged from the geriatrics service of an urban teaching hospital: patterns and risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:548-552. doi:10.1111/jgs.13317

- Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418-1428. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa0803563

- Hoyer EH, Needham DM, Atanelov L, Knox B, Friedman M, Brotman DJ. Association of impaired functional status at hospital discharge and subsequent rehospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:277-282. doi:10.1002/jhm.2152

- Mahoney J, Sager M, Dunham NC, Johnson J. Risk of falls after hospital discharge. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:269- 274. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb01750.x

- Hoffman GJ, Liu H, Alexander NB, Tinetti M, Braun TM, Min LC. Posthospital fall injuries and 30-day readmissions in adults 65 years and older. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e194276. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.4276

- Gill DP, Hubbard RA, Koepsell TD, et al. Differences in rate of functional decline across three dementia types. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:S63-S71. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2012.10.010

- Auyeung TW, Kwok T, Lee J, Leung PC, Leung J, Woo J. Functional decline in cognitive impairment–the relationship between physical and cognitive function. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;31:167-173. doi:10.1159/000154929

- Patti A, Zangla D, Sahin FN, et al. Physical exercise and prevention of falls. Effects of a Pilates training method compared with a general physical activity program. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e25289. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000025289

- Nagarkar A, Kulkarni S. Association between daily activities and fall in older adults: an analysis of longitudinal ageing study in India (2017-18). BMC Geriatr. 2022;22:203. doi:10.1186/s12877-022-02879-x

- Ek S, Rizzuto D, Xu W, Calderón-Larrañaga A, Welmer AK. Predictors for functional decline after an injurious fall: a population-based cohort study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021;33:2183-2190. doi:10.1007/s40520-020-01747-1

- Dagnino APA, Campos MM. Chronic pain in the elderly: mechanisms and perspectives. Front Hum Neurosci. 2022;16:736688. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2022.736688

- Ritchie CS, Patel K, Boscardin J, et al. Impact of persistent pain on function, cognition, and well-being of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71:26-35. doi:10.1111/jgs.18125

- Han TS, Murray P, Robin J, et al. Evaluation of the association of length of stay in hospital and outcomes. Int J Qual Health Care. 2022;34:mzab160. doi:10.1093/intqhc/ mzab160

- Lærum-Onsager E, Molin M, Olsen CF, et al. Effect of nutritional and physical exercise intervention on hospital readmission for patients aged 65 or older: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2021;18:62. doi:10.1186/s12966-021-01123-w

- Van Walraven C, Bennett C, Jennings A, Austin PC, Forster AJ. Proportion of hospital readmissions deemed avoidable: a systematic review. CMAJ. 2011;183:E391-E402. doi:10.1503/cmaj.101860

Deconditioning among hospitalized older adults contributes to significant decline in posthospitalization functional ability, physical performance, and physical activity.1-10 Previous hospital-to-home interventions have targeted improving function and physical activity, including recent programs leveraging home telehealth as a feasible and potentially effective mode of delivering in-home exercise and rehabilitation.11-14 However, pilot interventions have shown mixed effectiveness.11,12,14 This study expands on a previously published intervention describing a pilot home telehealth program for veterans posthospital discharge that demonstrated significant 6-month improvement in physical activity as well as trends in physical function improvement, including among those with cognitive impairment.15 Factors that contribute to improved outcomes are the focus of the present study.

Key factors underlying the complexity of hospital-to-home transitions include hospitalization elements (ie, reason for admission and length of stay), associated posthospital syndromes (ie, postdischarge falls, medication changes, cognitive impairment, and pain), and postdischarge health care application (ie, physical therapy and hospital readmission).16-18 These factors may be associated with postdischarge functional ability, physical performance, and physical activity, but their direct influence on intervention outcomes is unclear (Figure 1).5,7,9,16-20 The objective of this study was to examine the influence of hospitalization, posthospital syndrome, and postdischarge health care application factors on outcomes of a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Video Connect (VVC) intervention to enhance function and physical activity in older adults posthospital discharge.

health care application factors on physical activity, functional ability, and

physical performance intervention outcomes.

Methods

The previous analysis reported on patient characteristics, program feasibility, and preliminary outcomes.13,15 The current study reports on relationships between hospitalization, posthospital syndrome, and postdischarge health care application factors and change in key outcomes, namely postdischarge self-reported functional ability, physical performance, and physical activity from baseline to endpoint.

Participants provided written informed consent. The protocol and consent forms were approved by the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System (VAAAHS) Research and Development Committee, and the project was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04045054).

Intervention

The pilot program targeted older adults following recent hospital discharge from VAAAHS. Participants were eligible if they were aged ≥ 50 years, had been discharged following an inpatient stay in the past 1 to 2 weeks, evaluated by physical therapy during hospitalization with stated rehabilitation goals on discharge, and followed by a VAAAHS primary care physician. Participants were either recruited during hospital admission or shortly after discharge.13

An experienced physical activity trainer (PAT) supported the progression of participants’ rehabilitation goals via a home exercise program and coached the patient and caregiver to optimize functional ability, physical performance, and physical activity. The PAT was a nonlicensed research assistant with extensive experience in applying standard physical activity enhancement protocols (eg, increased walking) to older adults with comorbidities. Participation in the program lasted about 6 months. Initiation of the PAT program was delayed if the patient was already receiving postdischarge home-based or outpatient physical therapy. The PAT contacted the patient weekly via VVC for the first 6 weeks, then monthly for a total of 6 months. Each contact included information on optimal walking form, injury prevention, program progression, and ways to incorporate sit-to-stand transitions, nonsitting behavior, and walking into daily routines. The initial VVC contact lasted about 60 minutes and subsequent sessions lasted about 30 minutes.13

Demographic characteristics were self-reported by participants and included age, sex, race, years of education, and marital status. Clinical characteristics were obtained from each participant’s electronic health record (EHR), including copay status, index hospitalization length of stay, admission diagnosis, and postsurgery status (postsurgery vs nonpostsurgery). Intervention adherence was tracked as the number of PAT sessions attended.

Posthospital Syndrome Factors

Participant falls (categorized as those who reported a fall vs those who did not) and medication changes (number of changes reported, including new medication, discontinued medication, dose changes, medication changes, or changes in medication schedule) were reported by participants or caregivers during each VVC contact. Participants completed the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) at baseline, and were dichotomized into 2 groups: no cognitive impairment (MoCA score ≥ 26) and mild to moderate cognitive impairment (MoCA score 10-25).13,21

Participants rated how much pain interfered with their normal daily activities since the previous VVC session on a 5-point Likert scale (1, not at all; to 5, extremely).22 Similar to prior research, participants were placed into 2 groups based on their mean pain interference score (individuals with scores from 1.0 to 2.0 in 1 group, and individuals with > 2.0 in another).23-25 Participants were separated into a no or mild pain interference group and a moderate to severe pain interference group. Hospital readmissions (VA and non-VA) and postdischarge physical therapy outcomes were obtained from the participant’s EHR, including primary care visits.

Outcomes

Outcomes were collected at baseline (posthospital discharge) and 6 months postenrollment.

Self-Reported Functional Ability. This measure is provided by participants or caregivers and measured by the Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living (ADL), Lawton and Brody Instrumental ADL Scale (IADL), Nagi Disability Model, and Rosow-Breslau Scale. The Katz ADL assesses the ability to complete 6 self-care activities and awards 1 point for independence and 0 if the individual is dependent (total score range, 0-6).26 The Lawton and Brody IADL measures an individual’s independence in 8 instrumental ADLs; it awards 1 point for independence and 0 if the individual is dependent (total score range, 0-8).27 The Nagi Disability Model evaluates an individual’s difficulty performing 5 tasks (total score range, 0-5) and tallies the number of items with a response other than “no difficulty at all” (higher total score indicates greater difficulty). 28 The Rosow-Breslau Scale is a 3-item measure of mobility disability; individual responses are 0 (no help) and 1 (requires help or unable); higher total score (range, 0-3) indicates greater disability.29

Physical Performance. Measured using the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), which evaluates standing balance, sit to stand, and walking performance. Scores range from 0 to 4 on the balance, gait speed, and chair stand tests, for a total composite score between 0 and 12 (higher score indicates better performance).30

Physical Activity. Measured using actigraphy, namely a physical activity monitor adherent to the thigh (activ-PAL3TM, PAL Technologies Ltd., Glasgow, UK).31 Participants were instructed to wear the activPal for ≥ 1 week. Participants with a minimum of 5 days of wear were included in this analysis.

Data Analyses

Analyses were performed using SPSS software version 29.0.32 Continuous variables were summarized using mean (SD) or median and IQR using the weighted average method; categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages. Baseline scores on outcome variables were compared by categorical hospitalization, posthospital syndrome, and postdischarge health care application factor variables using Mann-Whitney U tests. The differences between outcome variables from baseline to endpoint were then calculated to produce change scores. Relationships between the number of PAT sessions attended and baseline outcomes and outcome change scores were estimated using Spearman correlations. Relationships between categorical factors (hospitalization, posthospital syndrome, and postdischarge health care application) and outcome variable change scores (which were normally distributed) were examined using Mann-Whitney U tests. Relationships with continuous hospitalization (length of stay) and posthospital syndrome factors (medication changes) were estimated using Spearman correlations. Effect sizes (ES) were estimated with Cohen d; small (d = 0.2), medium (d = 0.5), or large (d ≥ 0.8). Missing data were handled using pairwise deletion.33 Therefore, sample sizes were reported for each analysis. For all statistical tests, P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Twenty-four individuals completed the pilot intervention.15 Mean (SD) age was 73.6 (8.1) years (range, 64-93 years) and participants were predominantly White males (Table 1). Eight participants had a high school education only and 13 had more than a high school education. Diagnoses at admission included 9 patients with orthopedic/musculoskeletal conditions (6 were for joint replacement), 6 patients with vascular/pulmonary conditions, and 4 with gastrointestinal/renal/urological conditions. Of the 11 postsurgery participants, 7 were orthopedic, 4 were gastrointestinal, and 1 was peripheral vascular.

Baseline outcome scores did not differ significantly between groups, except individuals with moderate to severe pain interference reported a significantly lower IADL score (median [IQR] 4 [2-7]) than individuals with mild or moderate pain interference (median [IQR] 8 [7-8]; P = .02) (Table 2). The mean (SD) number of PAT sessions attended was 9.3 (3.7) (range, 3-19). There were no significant relationships between number of sessions attended and any baseline outcome variables or outcome change scores.

Hospitalization Factors

Participants who were postsurgery tended to have greater improvement than individuals who were nonpostsurgery in ADLs (median [IQR] 0 [0-1.5]; ES, 0.6; P = .10) and SPPB (median [IQR] 2 [1.5-9]; ES, 0.9; P = .07), but the improvements were not statistically significant (Table 3). Mean (SD) length of stay of the index hospitalization was 6.7 (6.1) days. Longer length of stay was significantly correlated with an increase in Nagi score (ρ, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.01-0.75). There were no other significant or trending relationships between length of stay and outcome variables.

Posthospital Syndrome Factors

The 16 participants with mild to moderate cognitive impairment had less improvement in ADLs (median [IQR] 0 [0-1]) than the 8 participants with no impairment (median [IQR] 0 [-0.75 to 0]; ES, -1.1; P = .04). Change in outcome variables from baseline to endpoint did not significantly differ between the 8 patients who reported a fall compared with the 13 who did not, nor were any trends observed. Change in outcome variables from baseline to endpoint also did not significantly differ between the 8 participants who reported no or mild pain interference compared with the 10 patients with moderate to severe pain interference, nor were any trends observed. Mean (SD) number of medication changes was 2.5 (1.6). Higher number of medication changes was significantly correlated with a decrease in Rosow-Breslau score (ρ, -0.47; 95% CI, -0.76 to -0.02). There were no other significant or trending relationships between number of medication changes and outcome variables.

Postdischarge Health Care Application Factors

The 16 participants who attended posthospital physical therapy trended towards less improvement in IADLs (median [IQR] 0 [-0.5 to 1.5]; ES, -0.7; P = .11) and SPPB (median [IQR] 2 [-3.0 to 4.5]; ES, -0.5; P = .15) than the 8 patients with no postdischarge physical therapy. Eleven participants were readmitted, while 13 had no readmissions in their medical records between baseline and endpoint. Participants with ≥ 1 readmission experienced a greater increase in Rosow-Breslau score (median [IQR] 0 [-0.5 to 1.0]) than those not readmitted (median [IQR] 0 [-1.25 to 0.25]; ES, 1.0; P = .03). Borderline greater improvement in number of steps was found in those not readmitted (median [IQR] 3365.6 [274.4-7710.9]) compared with those readmitted (median [IQR] 319.9 [-136.1 to 774.5]; ES, -1.3; P = .05). Patients who were readmitted also tended to have lower and not statistically significant improvements in SPPB (median [IQR] 1 [-4.0 to 5.3]) compared with those not readmitted (median [IQR] 2 [0.3-3.8]; ES, -0.5; P = .17) (Table 3).

Discussion

This study examined the association between hospitalization, posthospital syndrome, and postdischarge health care use in patients undergoing a VVC-based intervention following hospital discharge. Participants who had no or mild cognitive impairment, no readmissions, higher medication changes, and a shorter hospital length of stay tended to experience lower disability, including in mobility and ADLs. This suggests individuals who are less clinically complex may be more likely to benefit from this type of virtual rehabilitation program. These findings are consistent with clinical experiences; home-based programs to improve physical activity posthospital discharge can be challenging for those who were medically ill (and did not undergo a specific surgical procedure), cognitively impaired, and become acutely ill and trigger hospital readmission. 15 For example, the sample in this study had higher rates of falls, pain, and readmissions compared to previous research.2,3,34-39

The importance of posthospital syndrome in the context of recovery of function and health at home following hospitalization is well documented.16-18 The potential impact of posthospital syndrome on physical activity-focused interventions is less understood. In our analysis, participants with mild or moderate cognitive impairment tended to become more dependent in their ADLs, while those with no cognitive impairment tended to become more independent in their ADLs. This functional decline over time is perhaps expected in persons with cognitive impairment, but the significant difference with a large ES warrants further consideration on how to tailor interventions to better promote functional recovery in these individuals.40,41 While some cognitive decline may not be preventable, this finding supports the need to promote healthy cognitive aging, identify declines in cognition, and work to mitigate additional decline. Programs specifically designed to promote function and physical activity in older adults with cognitive impairment are needed, especially during care transitions.41-43

While participants reported that falls and pain interference did not have a significant impact on change in outcomes between baseline and endpoint, these areas need further investigation. Falls and pain have been associated with function and physical activity in older adults.42-46 Pain is common, yet underappreciated during older adult hospital-to-home transitions.11,12,45,46 There is a need for more comprehensive assessment of pain (including pain intensity) and qualitative research.

Hospitalization and postdischarge health care application factors may have a significant impact on home-telehealth physical activity intervention success. Individuals who were postsurgery tended to have greater improvements in ADLs and physical performance. Most postsurgery participants had joint replacement surgery. Postsurgery status may not be modifiable, but it is important to note expected differences in recovery between medical and surgical admissions and the need to tailor care based on admission diagnosis. Those with a longer length of hospital stay may be considered at higher risk of suboptimal outcomes postdischarge, which indicates an opportunity for targeting resources and support, in addition to efforts of reducing length of stay where possible.47

Readmissions were significantly related to a change in Rosow-Breslau mobility disability score. This may indicate the detrimental impact a readmission can have on increasing mobility and physical activity postdischarge, or the potential of this pilot program to impact readmissions by increasing mobility and physical activity, contrary to prior physical exercise interventions.5,7,9,48 With 5% to 79% of readmissions considered preventable, continued efforts and program dissemination and implementation to address preventable readmissions are warranted.49 Individuals with postdischarge physical therapy (prior to beginning the pilot program) tended to demonstrate less improvement in disability and physical performance. This relationship needs further investigation; the 2 groups did not appear to have significant differences at baseline, albeit with a small sample size. It is possible they experienced initial improvements with postdischarge physical therapy and plateaued or had little further reserve to improve upon entering the VVC program.

Strengths and Limitations

This pilot program provided evaluative data on the use of VVC to enhance function and physical activity in older adults posthospital discharge. It included individual (eg, fall, pain, cognitive impairment) and health service (eg, readmission, physical therapy) level factors as predictors of function and physical activity posthospitalization.5,7,9,15-19

The results of this pilot project stem from a small sample lacking diversity in terms of race, ethnicity, and sex. There was some variation in baseline and endpoints between participants, and when hospitalization, posthospital syndrome, and postdischarge health care application factors were collected. The majority of participants were recruited within a month postdischarge, and the program lasted about 6 months. Data collection was attempted at regular PAT contacts, but there was some variation in when visits occurred based on participant availability and preference. Some participants had missing data, which was handled using pairwise deletion.33 Larger studies are needed to confirm the findings of this study, particularly the trends that did not reach statistical significance. Home health services other than physical therapy (eg, nursing, occupational therapy) were not fully accounted for and should be considered in future research.

Conclusions

In patients undergoing a 6-month pilot VVC-based physical activity intervention posthospital discharge, improvements in mobility and disability were most likely in those who had no cognitive impairment and were not readmitted. Larger sample and qualitative investigations are necessary to optimize outcomes for patients who meet these clinical profiles.

Deconditioning among hospitalized older adults contributes to significant decline in posthospitalization functional ability, physical performance, and physical activity.1-10 Previous hospital-to-home interventions have targeted improving function and physical activity, including recent programs leveraging home telehealth as a feasible and potentially effective mode of delivering in-home exercise and rehabilitation.11-14 However, pilot interventions have shown mixed effectiveness.11,12,14 This study expands on a previously published intervention describing a pilot home telehealth program for veterans posthospital discharge that demonstrated significant 6-month improvement in physical activity as well as trends in physical function improvement, including among those with cognitive impairment.15 Factors that contribute to improved outcomes are the focus of the present study.

Key factors underlying the complexity of hospital-to-home transitions include hospitalization elements (ie, reason for admission and length of stay), associated posthospital syndromes (ie, postdischarge falls, medication changes, cognitive impairment, and pain), and postdischarge health care application (ie, physical therapy and hospital readmission).16-18 These factors may be associated with postdischarge functional ability, physical performance, and physical activity, but their direct influence on intervention outcomes is unclear (Figure 1).5,7,9,16-20 The objective of this study was to examine the influence of hospitalization, posthospital syndrome, and postdischarge health care application factors on outcomes of a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Video Connect (VVC) intervention to enhance function and physical activity in older adults posthospital discharge.

health care application factors on physical activity, functional ability, and

physical performance intervention outcomes.

Methods

The previous analysis reported on patient characteristics, program feasibility, and preliminary outcomes.13,15 The current study reports on relationships between hospitalization, posthospital syndrome, and postdischarge health care application factors and change in key outcomes, namely postdischarge self-reported functional ability, physical performance, and physical activity from baseline to endpoint.

Participants provided written informed consent. The protocol and consent forms were approved by the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System (VAAAHS) Research and Development Committee, and the project was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04045054).

Intervention

The pilot program targeted older adults following recent hospital discharge from VAAAHS. Participants were eligible if they were aged ≥ 50 years, had been discharged following an inpatient stay in the past 1 to 2 weeks, evaluated by physical therapy during hospitalization with stated rehabilitation goals on discharge, and followed by a VAAAHS primary care physician. Participants were either recruited during hospital admission or shortly after discharge.13

An experienced physical activity trainer (PAT) supported the progression of participants’ rehabilitation goals via a home exercise program and coached the patient and caregiver to optimize functional ability, physical performance, and physical activity. The PAT was a nonlicensed research assistant with extensive experience in applying standard physical activity enhancement protocols (eg, increased walking) to older adults with comorbidities. Participation in the program lasted about 6 months. Initiation of the PAT program was delayed if the patient was already receiving postdischarge home-based or outpatient physical therapy. The PAT contacted the patient weekly via VVC for the first 6 weeks, then monthly for a total of 6 months. Each contact included information on optimal walking form, injury prevention, program progression, and ways to incorporate sit-to-stand transitions, nonsitting behavior, and walking into daily routines. The initial VVC contact lasted about 60 minutes and subsequent sessions lasted about 30 minutes.13

Demographic characteristics were self-reported by participants and included age, sex, race, years of education, and marital status. Clinical characteristics were obtained from each participant’s electronic health record (EHR), including copay status, index hospitalization length of stay, admission diagnosis, and postsurgery status (postsurgery vs nonpostsurgery). Intervention adherence was tracked as the number of PAT sessions attended.

Posthospital Syndrome Factors

Participant falls (categorized as those who reported a fall vs those who did not) and medication changes (number of changes reported, including new medication, discontinued medication, dose changes, medication changes, or changes in medication schedule) were reported by participants or caregivers during each VVC contact. Participants completed the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) at baseline, and were dichotomized into 2 groups: no cognitive impairment (MoCA score ≥ 26) and mild to moderate cognitive impairment (MoCA score 10-25).13,21

Participants rated how much pain interfered with their normal daily activities since the previous VVC session on a 5-point Likert scale (1, not at all; to 5, extremely).22 Similar to prior research, participants were placed into 2 groups based on their mean pain interference score (individuals with scores from 1.0 to 2.0 in 1 group, and individuals with > 2.0 in another).23-25 Participants were separated into a no or mild pain interference group and a moderate to severe pain interference group. Hospital readmissions (VA and non-VA) and postdischarge physical therapy outcomes were obtained from the participant’s EHR, including primary care visits.

Outcomes

Outcomes were collected at baseline (posthospital discharge) and 6 months postenrollment.

Self-Reported Functional Ability. This measure is provided by participants or caregivers and measured by the Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living (ADL), Lawton and Brody Instrumental ADL Scale (IADL), Nagi Disability Model, and Rosow-Breslau Scale. The Katz ADL assesses the ability to complete 6 self-care activities and awards 1 point for independence and 0 if the individual is dependent (total score range, 0-6).26 The Lawton and Brody IADL measures an individual’s independence in 8 instrumental ADLs; it awards 1 point for independence and 0 if the individual is dependent (total score range, 0-8).27 The Nagi Disability Model evaluates an individual’s difficulty performing 5 tasks (total score range, 0-5) and tallies the number of items with a response other than “no difficulty at all” (higher total score indicates greater difficulty). 28 The Rosow-Breslau Scale is a 3-item measure of mobility disability; individual responses are 0 (no help) and 1 (requires help or unable); higher total score (range, 0-3) indicates greater disability.29

Physical Performance. Measured using the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), which evaluates standing balance, sit to stand, and walking performance. Scores range from 0 to 4 on the balance, gait speed, and chair stand tests, for a total composite score between 0 and 12 (higher score indicates better performance).30

Physical Activity. Measured using actigraphy, namely a physical activity monitor adherent to the thigh (activ-PAL3TM, PAL Technologies Ltd., Glasgow, UK).31 Participants were instructed to wear the activPal for ≥ 1 week. Participants with a minimum of 5 days of wear were included in this analysis.

Data Analyses

Analyses were performed using SPSS software version 29.0.32 Continuous variables were summarized using mean (SD) or median and IQR using the weighted average method; categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages. Baseline scores on outcome variables were compared by categorical hospitalization, posthospital syndrome, and postdischarge health care application factor variables using Mann-Whitney U tests. The differences between outcome variables from baseline to endpoint were then calculated to produce change scores. Relationships between the number of PAT sessions attended and baseline outcomes and outcome change scores were estimated using Spearman correlations. Relationships between categorical factors (hospitalization, posthospital syndrome, and postdischarge health care application) and outcome variable change scores (which were normally distributed) were examined using Mann-Whitney U tests. Relationships with continuous hospitalization (length of stay) and posthospital syndrome factors (medication changes) were estimated using Spearman correlations. Effect sizes (ES) were estimated with Cohen d; small (d = 0.2), medium (d = 0.5), or large (d ≥ 0.8). Missing data were handled using pairwise deletion.33 Therefore, sample sizes were reported for each analysis. For all statistical tests, P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Twenty-four individuals completed the pilot intervention.15 Mean (SD) age was 73.6 (8.1) years (range, 64-93 years) and participants were predominantly White males (Table 1). Eight participants had a high school education only and 13 had more than a high school education. Diagnoses at admission included 9 patients with orthopedic/musculoskeletal conditions (6 were for joint replacement), 6 patients with vascular/pulmonary conditions, and 4 with gastrointestinal/renal/urological conditions. Of the 11 postsurgery participants, 7 were orthopedic, 4 were gastrointestinal, and 1 was peripheral vascular.

Baseline outcome scores did not differ significantly between groups, except individuals with moderate to severe pain interference reported a significantly lower IADL score (median [IQR] 4 [2-7]) than individuals with mild or moderate pain interference (median [IQR] 8 [7-8]; P = .02) (Table 2). The mean (SD) number of PAT sessions attended was 9.3 (3.7) (range, 3-19). There were no significant relationships between number of sessions attended and any baseline outcome variables or outcome change scores.

Hospitalization Factors

Participants who were postsurgery tended to have greater improvement than individuals who were nonpostsurgery in ADLs (median [IQR] 0 [0-1.5]; ES, 0.6; P = .10) and SPPB (median [IQR] 2 [1.5-9]; ES, 0.9; P = .07), but the improvements were not statistically significant (Table 3). Mean (SD) length of stay of the index hospitalization was 6.7 (6.1) days. Longer length of stay was significantly correlated with an increase in Nagi score (ρ, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.01-0.75). There were no other significant or trending relationships between length of stay and outcome variables.

Posthospital Syndrome Factors

The 16 participants with mild to moderate cognitive impairment had less improvement in ADLs (median [IQR] 0 [0-1]) than the 8 participants with no impairment (median [IQR] 0 [-0.75 to 0]; ES, -1.1; P = .04). Change in outcome variables from baseline to endpoint did not significantly differ between the 8 patients who reported a fall compared with the 13 who did not, nor were any trends observed. Change in outcome variables from baseline to endpoint also did not significantly differ between the 8 participants who reported no or mild pain interference compared with the 10 patients with moderate to severe pain interference, nor were any trends observed. Mean (SD) number of medication changes was 2.5 (1.6). Higher number of medication changes was significantly correlated with a decrease in Rosow-Breslau score (ρ, -0.47; 95% CI, -0.76 to -0.02). There were no other significant or trending relationships between number of medication changes and outcome variables.

Postdischarge Health Care Application Factors

The 16 participants who attended posthospital physical therapy trended towards less improvement in IADLs (median [IQR] 0 [-0.5 to 1.5]; ES, -0.7; P = .11) and SPPB (median [IQR] 2 [-3.0 to 4.5]; ES, -0.5; P = .15) than the 8 patients with no postdischarge physical therapy. Eleven participants were readmitted, while 13 had no readmissions in their medical records between baseline and endpoint. Participants with ≥ 1 readmission experienced a greater increase in Rosow-Breslau score (median [IQR] 0 [-0.5 to 1.0]) than those not readmitted (median [IQR] 0 [-1.25 to 0.25]; ES, 1.0; P = .03). Borderline greater improvement in number of steps was found in those not readmitted (median [IQR] 3365.6 [274.4-7710.9]) compared with those readmitted (median [IQR] 319.9 [-136.1 to 774.5]; ES, -1.3; P = .05). Patients who were readmitted also tended to have lower and not statistically significant improvements in SPPB (median [IQR] 1 [-4.0 to 5.3]) compared with those not readmitted (median [IQR] 2 [0.3-3.8]; ES, -0.5; P = .17) (Table 3).

Discussion

This study examined the association between hospitalization, posthospital syndrome, and postdischarge health care use in patients undergoing a VVC-based intervention following hospital discharge. Participants who had no or mild cognitive impairment, no readmissions, higher medication changes, and a shorter hospital length of stay tended to experience lower disability, including in mobility and ADLs. This suggests individuals who are less clinically complex may be more likely to benefit from this type of virtual rehabilitation program. These findings are consistent with clinical experiences; home-based programs to improve physical activity posthospital discharge can be challenging for those who were medically ill (and did not undergo a specific surgical procedure), cognitively impaired, and become acutely ill and trigger hospital readmission. 15 For example, the sample in this study had higher rates of falls, pain, and readmissions compared to previous research.2,3,34-39

The importance of posthospital syndrome in the context of recovery of function and health at home following hospitalization is well documented.16-18 The potential impact of posthospital syndrome on physical activity-focused interventions is less understood. In our analysis, participants with mild or moderate cognitive impairment tended to become more dependent in their ADLs, while those with no cognitive impairment tended to become more independent in their ADLs. This functional decline over time is perhaps expected in persons with cognitive impairment, but the significant difference with a large ES warrants further consideration on how to tailor interventions to better promote functional recovery in these individuals.40,41 While some cognitive decline may not be preventable, this finding supports the need to promote healthy cognitive aging, identify declines in cognition, and work to mitigate additional decline. Programs specifically designed to promote function and physical activity in older adults with cognitive impairment are needed, especially during care transitions.41-43

While participants reported that falls and pain interference did not have a significant impact on change in outcomes between baseline and endpoint, these areas need further investigation. Falls and pain have been associated with function and physical activity in older adults.42-46 Pain is common, yet underappreciated during older adult hospital-to-home transitions.11,12,45,46 There is a need for more comprehensive assessment of pain (including pain intensity) and qualitative research.

Hospitalization and postdischarge health care application factors may have a significant impact on home-telehealth physical activity intervention success. Individuals who were postsurgery tended to have greater improvements in ADLs and physical performance. Most postsurgery participants had joint replacement surgery. Postsurgery status may not be modifiable, but it is important to note expected differences in recovery between medical and surgical admissions and the need to tailor care based on admission diagnosis. Those with a longer length of hospital stay may be considered at higher risk of suboptimal outcomes postdischarge, which indicates an opportunity for targeting resources and support, in addition to efforts of reducing length of stay where possible.47

Readmissions were significantly related to a change in Rosow-Breslau mobility disability score. This may indicate the detrimental impact a readmission can have on increasing mobility and physical activity postdischarge, or the potential of this pilot program to impact readmissions by increasing mobility and physical activity, contrary to prior physical exercise interventions.5,7,9,48 With 5% to 79% of readmissions considered preventable, continued efforts and program dissemination and implementation to address preventable readmissions are warranted.49 Individuals with postdischarge physical therapy (prior to beginning the pilot program) tended to demonstrate less improvement in disability and physical performance. This relationship needs further investigation; the 2 groups did not appear to have significant differences at baseline, albeit with a small sample size. It is possible they experienced initial improvements with postdischarge physical therapy and plateaued or had little further reserve to improve upon entering the VVC program.

Strengths and Limitations

This pilot program provided evaluative data on the use of VVC to enhance function and physical activity in older adults posthospital discharge. It included individual (eg, fall, pain, cognitive impairment) and health service (eg, readmission, physical therapy) level factors as predictors of function and physical activity posthospitalization.5,7,9,15-19

The results of this pilot project stem from a small sample lacking diversity in terms of race, ethnicity, and sex. There was some variation in baseline and endpoints between participants, and when hospitalization, posthospital syndrome, and postdischarge health care application factors were collected. The majority of participants were recruited within a month postdischarge, and the program lasted about 6 months. Data collection was attempted at regular PAT contacts, but there was some variation in when visits occurred based on participant availability and preference. Some participants had missing data, which was handled using pairwise deletion.33 Larger studies are needed to confirm the findings of this study, particularly the trends that did not reach statistical significance. Home health services other than physical therapy (eg, nursing, occupational therapy) were not fully accounted for and should be considered in future research.

Conclusions

In patients undergoing a 6-month pilot VVC-based physical activity intervention posthospital discharge, improvements in mobility and disability were most likely in those who had no cognitive impairment and were not readmitted. Larger sample and qualitative investigations are necessary to optimize outcomes for patients who meet these clinical profiles.

- Liebzeit D, Bratzke L, Boltz M, Purvis S, King B. Getting back to normal: a grounded theory study of function in post-hospitalized older adults. Gerontologist. 2020;60:704-714. doi:10.1093/geront/gnz057

- Ponzetto M, Zanocchi M, Maero B, et al. Post-hospitalization mortality in the elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2003;36:83-91. doi:10.1016/s0167-4943(02)00061-4

- Buurman BM, Hoogerduijn JG, de Haan RJ, et al. Geriatric conditions in acutely hospitalized older patients: prevalence and one-year survival and functional decline. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26951. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026951

- Ponzetto M, Maero B, Maina P, et al. Risk factors for early and late mortality in hospitalized older patients: the continuing importance of functional status. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:1049-1054. doi:10.1093/gerona/58.11.m1049

- Huang HT, Chang CM, Liu LF, Lin HS, Chen CH. Trajectories and predictors of functional decline of hospitalised older patients. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22:1322-1331. doi:10.1111/jocn.12055

- Boyd CM, Landefeld CS, Counsell SR, et al. Recovery of activities of daily living in older adults after hospitalization for acute medical illness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:2171- 2179. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02023.x

- Helvik AS, Selbæk G, Engedal K. Functional decline in older adults one year after hospitalization. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;57:305-310. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2013.05.008

- Zaslavsky O, Zisberg A, Shadmi E. Impact of functional change before and during hospitalization on functional recovery 1 month following hospitalization. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70:381-386. doi:10.1093/gerona/glu168

- Chen CC, Wang C, Huang GH. Functional trajectory 6 months posthospitalization: a cohort study of older hospitalized patients in Taiwan. Nurs Res. 2008;57:93-100. doi:10.1097/01.NNR.0000313485.18670.e2

- Kleinpell RM, Fletcher K, Jennings BM. Reducing functional decline in hospitalized elderly. In: Hughes RG, ed. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008. Accessed September 3, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2629/

- Liebzeit D, Rutkowski R, Arbaje AI, Fields B, Werner NE. A scoping review of interventions for older adults transitioning from hospital to home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:2950-2962. doi:10.1111/jgs.17323

- Hladkowicz E, Dumitrascu F, Auais M, et al. Evaluations of postoperative transitions in care for older adults: a scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22:329. doi:10.1186/s12877-022-02989-6

- Alexander NB, Phillips K, Wagner-Felkey J, et al. Team VA Video Connect (VVC) to optimize mobility and physical activity in post-hospital discharge older veterans: baseline assessment. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21:502. doi:10.1186/s12877-021-02454-w

- Dawson R, Oliveira JS, Kwok WS, et al. Exercise interventions delivered through telehealth to improve physical functioning for older adults with frailty, cognitive, or mobility disability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Telemed J E Health. 2024;30:940-950. doi:10.1089/tmj.2023.0177

- Liebzeit D, Phillips KK, Hogikyan RV, Cigolle CT, Alexander NB. A pilot home-telehealth program to enhance functional ability, physical performance, and physical activity in older adult veterans post-hospital discharge. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2024;17:271-279. doi:10.3928/19404921-20241105-01

- Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome—an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:100-102. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1212324

- Caraballo C, Dharmarajan K, Krumholz HM. Post hospital syndrome: is the stress of hospitalization causing harm? Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2019;72:896-898. doi:10.1016/j.rec.2019.04.010

- Rawal S, Kwan JL, Razak F, et al. Association of the trauma of hospitalization with 30-day readmission or emergency department visit. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:38- 45. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5100

- Dutzi I, Schwenk M, Kirchner M, Jooss E, Bauer JM, Hauer K. Influence of cognitive impairment on rehabilitation received and its mediating effect on functional recovery. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;84:745-756. doi:10.3233/JAD-210620

- Uriz-Otano F, Uriz-Otano JI, Malafarina V. Factors associated with short-term functional recovery in elderly people with a hip fracture. Influence ofcognitiveimpairment. JAmMedDirAssoc. 2015;16:215-220. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2014.09.009

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695-699. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

- Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473-483.

- White RS, Jiang J, Hall CB, et al. Higher perceived stress scale scores are associated with higher pain intensity and pain interference levels in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:2350-2356. doi:10.1111/jgs.13135

- Blyth FM, March LM, Brnabic AJ, et al. Chronic pain in Australia: a prevalence study. Pain. 2001;89:127-134. doi:10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00355-9

- Thomas E, Peat G, Harris L, Wilkie R, Croft PR. The prevalence of pain and pain interference in a general population of older adults: cross-sectional findings from the North Staffordshire Osteoarthritis Project (NorStOP). Pain. 2004;110:361-368. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2004.04.017

- Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914-919. doi:10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016

- Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179-186.

- Alexander NB, Guire KE, Thelen DG, et al. Self-reported walking ability predicts functional mobility performance in frail older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1408-1413. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02630.x

- Rosow I, Breslau N. A Guttman health scale for the aged. J Gerontol. 1966;21:556-559. doi:10.1093/geronj/21.4.556

- Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M85-M94. doi:10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85

- Chan CS, Slaughter SE, Jones CA, Ickert C, Wagg AS. Measuring activity performance of older adults using the activPAL: a rapid review. Healthcare (Basel). 2017;5:94. doi:10.3390/healthcare5040094

- IBM SPSS software. IBM Corp; 2019. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://www.ibm.com/spss

- Kang H. The prevention and handling of the missing data. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2013;64:402-406. doi:10.4097/kjae.2013.64.5.402

- Epstein AM, Jha AK, Orav EJ. The relationship between hospital admission rates and rehospitalizations. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2287-2295. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1101942

- Bogaisky M, Dezieck L. Early hospital readmission of nursing home residents and community-dwelling elderly adults discharged from the geriatrics service of an urban teaching hospital: patterns and risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:548-552. doi:10.1111/jgs.13317

- Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418-1428. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa0803563

- Hoyer EH, Needham DM, Atanelov L, Knox B, Friedman M, Brotman DJ. Association of impaired functional status at hospital discharge and subsequent rehospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:277-282. doi:10.1002/jhm.2152

- Mahoney J, Sager M, Dunham NC, Johnson J. Risk of falls after hospital discharge. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:269- 274. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb01750.x

- Hoffman GJ, Liu H, Alexander NB, Tinetti M, Braun TM, Min LC. Posthospital fall injuries and 30-day readmissions in adults 65 years and older. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e194276. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.4276

- Gill DP, Hubbard RA, Koepsell TD, et al. Differences in rate of functional decline across three dementia types. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:S63-S71. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2012.10.010

- Auyeung TW, Kwok T, Lee J, Leung PC, Leung J, Woo J. Functional decline in cognitive impairment–the relationship between physical and cognitive function. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;31:167-173. doi:10.1159/000154929

- Patti A, Zangla D, Sahin FN, et al. Physical exercise and prevention of falls. Effects of a Pilates training method compared with a general physical activity program. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e25289. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000025289

- Nagarkar A, Kulkarni S. Association between daily activities and fall in older adults: an analysis of longitudinal ageing study in India (2017-18). BMC Geriatr. 2022;22:203. doi:10.1186/s12877-022-02879-x

- Ek S, Rizzuto D, Xu W, Calderón-Larrañaga A, Welmer AK. Predictors for functional decline after an injurious fall: a population-based cohort study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021;33:2183-2190. doi:10.1007/s40520-020-01747-1

- Dagnino APA, Campos MM. Chronic pain in the elderly: mechanisms and perspectives. Front Hum Neurosci. 2022;16:736688. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2022.736688

- Ritchie CS, Patel K, Boscardin J, et al. Impact of persistent pain on function, cognition, and well-being of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71:26-35. doi:10.1111/jgs.18125

- Han TS, Murray P, Robin J, et al. Evaluation of the association of length of stay in hospital and outcomes. Int J Qual Health Care. 2022;34:mzab160. doi:10.1093/intqhc/ mzab160

- Lærum-Onsager E, Molin M, Olsen CF, et al. Effect of nutritional and physical exercise intervention on hospital readmission for patients aged 65 or older: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2021;18:62. doi:10.1186/s12966-021-01123-w

- Van Walraven C, Bennett C, Jennings A, Austin PC, Forster AJ. Proportion of hospital readmissions deemed avoidable: a systematic review. CMAJ. 2011;183:E391-E402. doi:10.1503/cmaj.101860

- Liebzeit D, Bratzke L, Boltz M, Purvis S, King B. Getting back to normal: a grounded theory study of function in post-hospitalized older adults. Gerontologist. 2020;60:704-714. doi:10.1093/geront/gnz057

- Ponzetto M, Zanocchi M, Maero B, et al. Post-hospitalization mortality in the elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2003;36:83-91. doi:10.1016/s0167-4943(02)00061-4

- Buurman BM, Hoogerduijn JG, de Haan RJ, et al. Geriatric conditions in acutely hospitalized older patients: prevalence and one-year survival and functional decline. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26951. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026951

- Ponzetto M, Maero B, Maina P, et al. Risk factors for early and late mortality in hospitalized older patients: the continuing importance of functional status. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:1049-1054. doi:10.1093/gerona/58.11.m1049

- Huang HT, Chang CM, Liu LF, Lin HS, Chen CH. Trajectories and predictors of functional decline of hospitalised older patients. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22:1322-1331. doi:10.1111/jocn.12055

- Boyd CM, Landefeld CS, Counsell SR, et al. Recovery of activities of daily living in older adults after hospitalization for acute medical illness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:2171- 2179. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02023.x

- Helvik AS, Selbæk G, Engedal K. Functional decline in older adults one year after hospitalization. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;57:305-310. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2013.05.008

- Zaslavsky O, Zisberg A, Shadmi E. Impact of functional change before and during hospitalization on functional recovery 1 month following hospitalization. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70:381-386. doi:10.1093/gerona/glu168

- Chen CC, Wang C, Huang GH. Functional trajectory 6 months posthospitalization: a cohort study of older hospitalized patients in Taiwan. Nurs Res. 2008;57:93-100. doi:10.1097/01.NNR.0000313485.18670.e2