User login

A True Community: The Vet-to-Vet Program for Chronic Pain

A True Community: The Vet-to-Vet Program for Chronic Pain

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has continued to advance its understanding and treatment of chronic pain. The VHA National Pain Management Strategy emphasizes the significance of the social context of pain while underscoring the importance of self-management.1 This established strategy ensures that all veterans have access to the appropriate pain care in the proper setting.2 VHA has instituted a stepped care model of pain management, delineating the domains of primary care, secondary consultative services, and tertiary care.3 This directive emphasized a biopsychosocial approach to pain management to prioritize the relationship between biological, psychological, and social factors that influence how veterans experience pain and should commensurately influence how it is managed.

The VHA Office of Patient-Centered Care and Cultural Transformation implemented the Whole Health System of Care as part of the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, which included a VHA directive to expand pain management.4,5 Reorientation within this system shifts from defining veterans as passive care recipients to viewing them as active partners in their own care and health. This partnership places additional emphasis on peer-led explorations of mission, aspiration, and purpose.6

Peer-led groups, also known as mutual aid, mutual support, and mutual help groups, have historically been successful for patients undergoing treatment for substance use disorders (eg, Alcoholics Anonymous).7 Mutual help groups have 3 defining characteristics. First, they are run by participants, not professionals, though the latter may have been integral in the founding of the groups. Second, participants share a similar problem (eg, disease state, experience, disposition). Finally, there is a reciprocal exchange of information and psychological support among participants.8,9 Mutual help groups that address chronic pain are rare but becoming more common.10-12 Emerging evidence suggests a positive relationship between peer support and improved well-being, self-efficacy, pain management, and pain self-management skills (eg, activity pacing).13-15

Storytelling as a tool for healing has a long history in indigenous and Western medical traditions.16-19 This includes the treatment of chronic disease, including pain.20,21 The use of storytelling in health care overlaps with the role it plays within many mutual help groups focused on chronic disease treatment.22 Storytelling allows an individual to share their experience with a disease, and take a more active role in their health, and facilitate stronger bonds with others.22 In effect, storytelling is not only important to group cohesion—it also plays a role in an individual’s healing.

Vet-to-Vet

The VHA Office of Rural Health funds Vet-to-Vet, a peer-to-peer program to address limited access to care for rural veterans with chronic pain. Similar to the VHA National Pain Management Strategy, Vet-to-Vet is grounded in the significance of the social context of pain and underscores the importance of self-management.1 The program combines pain care, mutual help, and storytelling to support veterans living with chronic pain. While the primary focus of Vet-to-Vet is rural veterans, the program serves any veteran experiencing chronic pain who is isolated from services, including home-bound urban veterans.

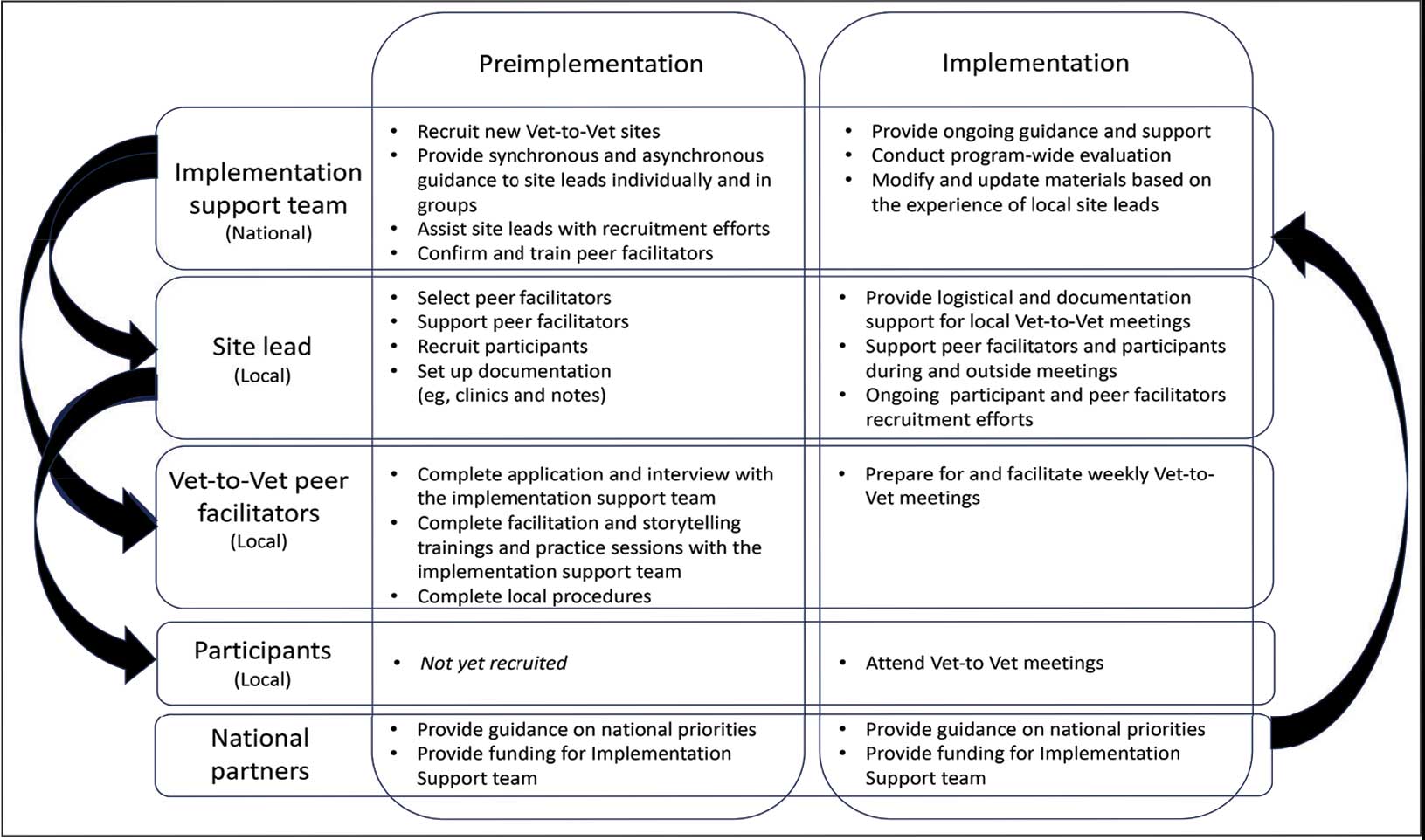

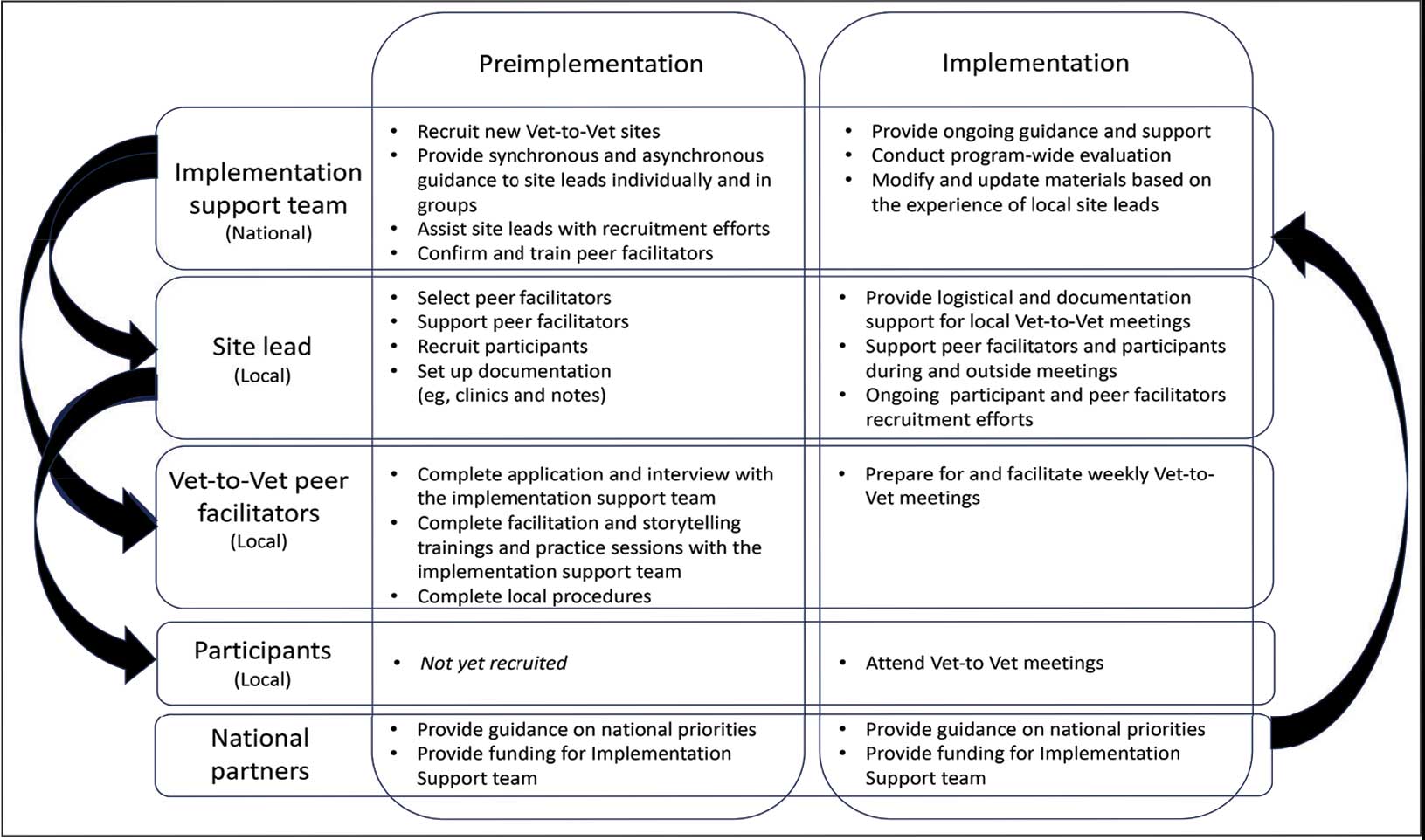

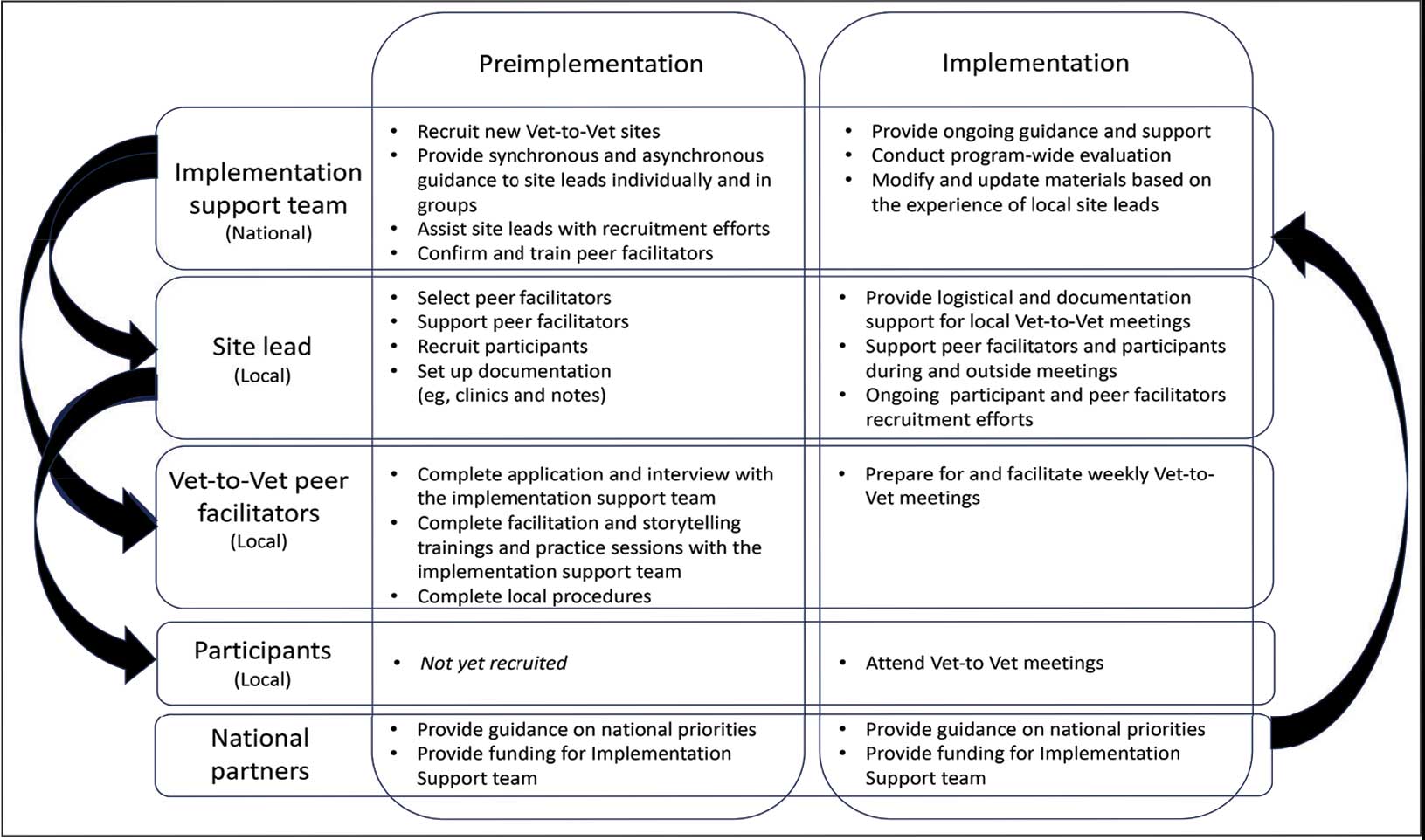

Following mutual help principles, Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators lead weekly online drop-in meetings. Meetings follow the general structure of reiterating group ground rules and sharing an individual pain story, followed by open discussions centered on well-being, chronic pain management, or any topic the group wishes to discuss. Meetings typically end with a mindfulness exercise. The organizational structure that supports Vet-to-Vet includes the implementation support team, site leads, Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators, and national partners (Figure 1).

Implementation Support Team

The implementation support team consists of a principal investigator, coinvestigator, program manager, and program support specialist. The team provides facilitator training, monthly community practice sessions for Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators and site leads, and weekly office hours for site leads. The implementation support team also recruits new Vet-to-Vet sites; potential new locations ideally have an existing whole health program, leadership support, committed site and cosite leads, and ≥ 3 peer facilitator volunteers.

Site Leads

Most site and cosite leads are based in whole health or pain management teams and are whole health coaches or peer support specialists. The site lead is responsible for standing up the program and documenting encounters, recruiting and supporting peer facilitators and participants, and overseeing the meeting. During meetings, site leads generally leave their cameras off and only speak when called into the group; the peer facilitators lead the meetings. The implementation support team recommends that site leads dedicate ≥ 4 hours per week to Vet-to-Vet; 2 hours for weekly group meetings and 2 hours for documentation (ie, entering notes into the participants’ electronic health records) and supporting peer facilitators and participants. Cosite lead responsibilities vary by location, with some sites having 2 leads that equally share duties and others having a primary lead and a colead available if the site lead is unable to attend a meeting.

Vet-to-Vet Peer Facilitators

Peer facilitators are the core of the program. They lead meetings from start to finish. Like participants, they also experience chronic pain and are volunteers. The implementation support team encourages sites to establish volunteer peer facilitators, rather than assigning peer support specialists to facilitate meetings. Veterans are eager to connect and give back to their communities, and the Vet-to-Vet peer facilitator role is an opportunity for those unable to work to connect with peers and add meaning to their lives. Even if a VHA employee is a veteran who has chronic pain, they are not eligible to serve as this could create a service provider/service recipient dynamic that is not in the spirit of mutual help.

Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators attend a virtual 3-day training held by the implementation support team prior to starting. These training sessions are available on a quarterly basis and facilitated by the Vet-to-Vet program manager and 2 current peer facilitators. Training content includes established whole health facilitator training materials and program-specific storytelling training materials. Once trained, peer facilitators attend storytelling practice sessions and collaborate with their site leads during weekly meetings.

Participants

Vet-to-Vet participants find the program through direct outreach from site leads, word of mouth, and referrals. The only criteria to join are that the individual is a veteran who experiences chronic pain and is enrolled in the VHA (site leads can assist with enrollment if needed). Participants are not required to have a diagnosis or engage in any other health care. There is no commitment and no end date. Some participants only come once; others have attended for > 3 years. This approach is intended to embrace the idea that the need for support ebbs and flows.

National Partners

The VHA Office of Rural Health provides technical support. The Center for Development and Civic Engagement onboards peer facilitators as VHA volunteers. The Office of Patient-Centered Care and Cultural Transformation provides national guidance and site-level collaboration. The VHA Pain Management, Opioid Safety, and Prescription Drug Monitoring Program supports site recruitment. In addition to the VHA partners, 4 veteran evaluation consultants who have experience with chronic pain but do not participate in Vet-to-Vet meetings provide advice on evaluation activities, such as question development and communication strategies.

Evaluation

This evaluation shares preliminary results from a pilot evaluation of the Rocky Mountain Regional VA Medical Center (RMRVAMC) Vet-to-Vet group. It is intended for program improvement, was deemed nonresearch by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board, and was structured using the RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance) framework.23 This evaluation focused on capturing measures related to reach and effectiveness, while a forthcoming evaluation includes elements of adoption, implementation, and maintenance.

In 2022, 16 Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators and participants completed surveys and interviews to share their experience. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded in ATLAS.ti. A priori codes were based on interview guide questions and emergent descriptive codes were used to identify specific topics which were categorized into RE-AIM domains, barriers, facilitators, what participants learned, how participants applied what they learned to their lives, and participant reported outcomes. This article contains high-level findings from the evaluation; more detailed results will be included in the ongoing evaluation.

Results

The RMRVAMC Vet-to-Vet group has met weekly since April 2022. Four Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators and 12 individuals participated in the pilot Vet-to-Vet group and evaluation. The mean age was 62 years, most were men, and half were married. Most participants lived in rural areas with a mean distance of 125 miles to the nearest VAMC. Many experienced multiple kinds of pain, with a mean 4.5 on a 10-point scale (bothered “a lot”). All participants reported that they experienced pain daily.

Participation in Vet-to-Vet meetings was high; 3 of 4 peer facilitators and 7 of 12 participants completed the first 6 months of the program. In interviews, participants described the positive impact of the program. They emphasized the importance of connecting with other veterans and helping one another, with one noting that opportunities to connect with other veterans “just drops off a lot” (peer facilitator 3) after leaving active duty.

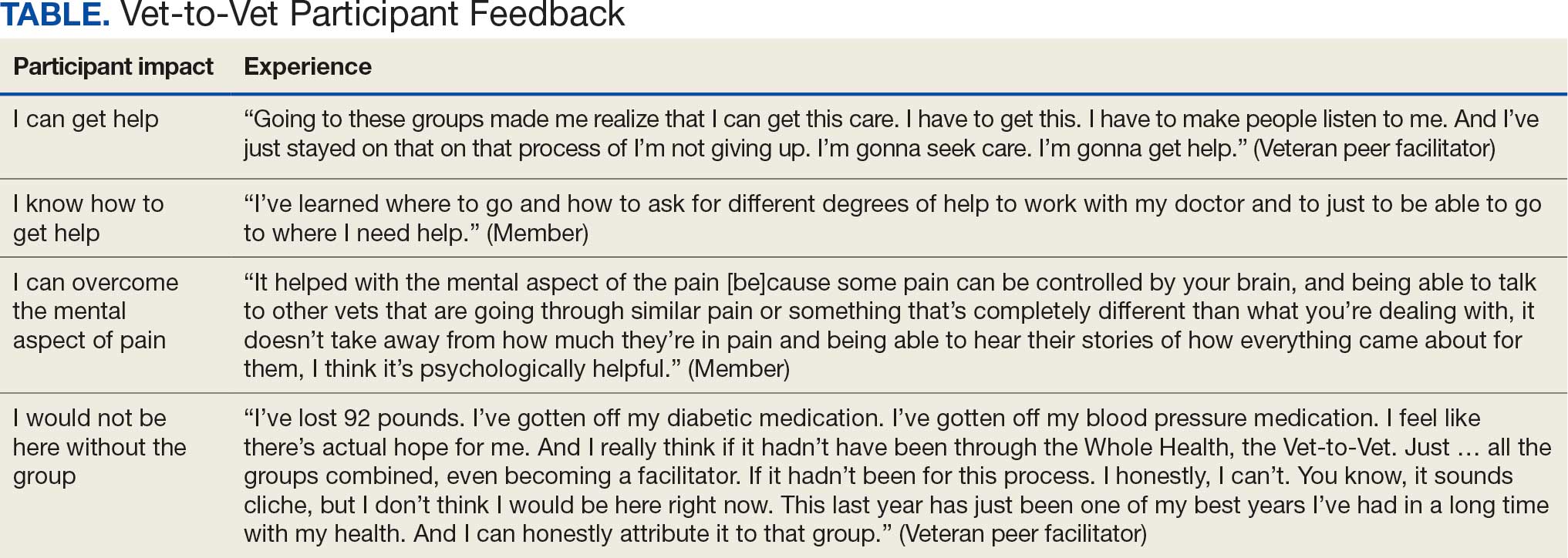

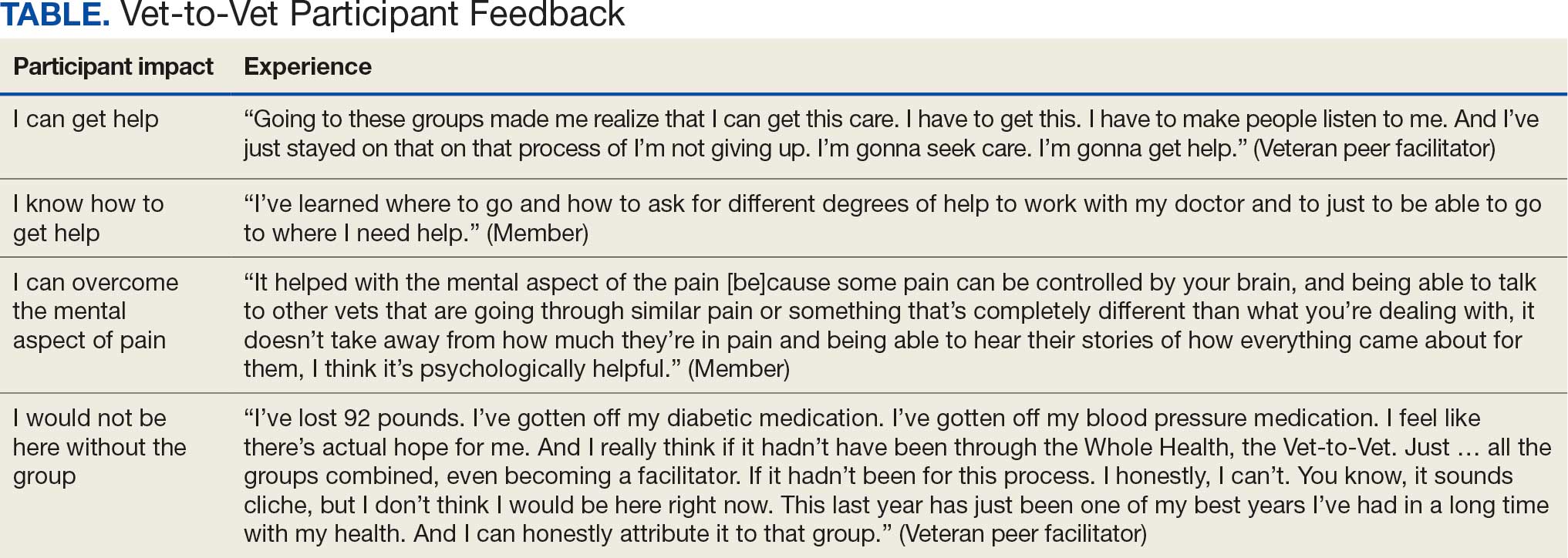

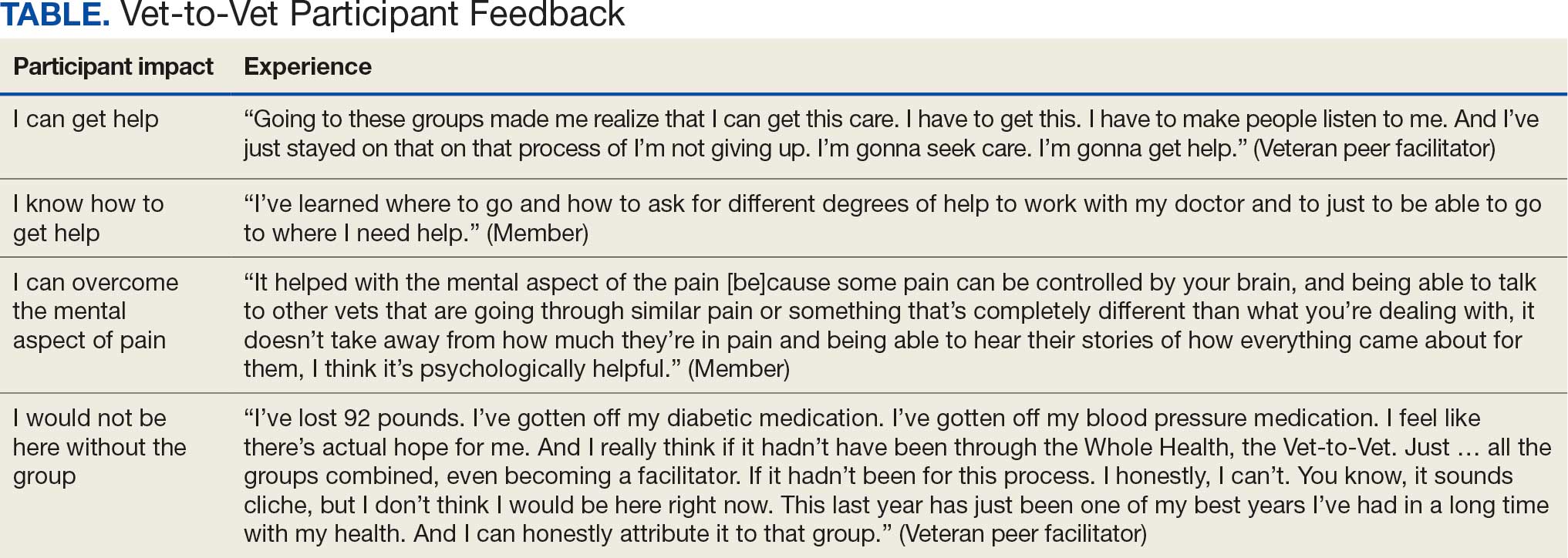

Some participants and Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators outlined the content of the sessions (eg, learning about how pain impacts the body and one’s family relationships) and shared the skills they learned (eg, goal setting, self-advocacy) (Table). Most spoke about learning from one another and the power of sharing stories with one peer facilitator sharing how they felt that witnessing another participant’s story “really shifted how I was thinking about things and how I perceived people” (peer facilitator 1).

Participants reported several ways the program impacted their lives, such as learning that they could get help, how to get help, and how to overcome the mental aspects of chronic pain. One veteran shared profound health impacts and attributed the Vet-to-Vet program to having one of the best years of their life. Even those who did not attend many meetings spoke of it positively and stated that it should continue so others could try (Table).

From January 2022 to September 2025, > 80 veterans attended ≥ 1 meeting at RMRVAMC; 29 attended ≥ 1 meeting in the last quarter. There were > 1400 Vet-to-Vet encounters at RMRVAMC, with a mean (SD) of 14.2 (19.2) and a median of 4.5 encounters per participant. Half of the veterans attend ≥ 5 meetings, and one-third attended ≥ 10 meetings.

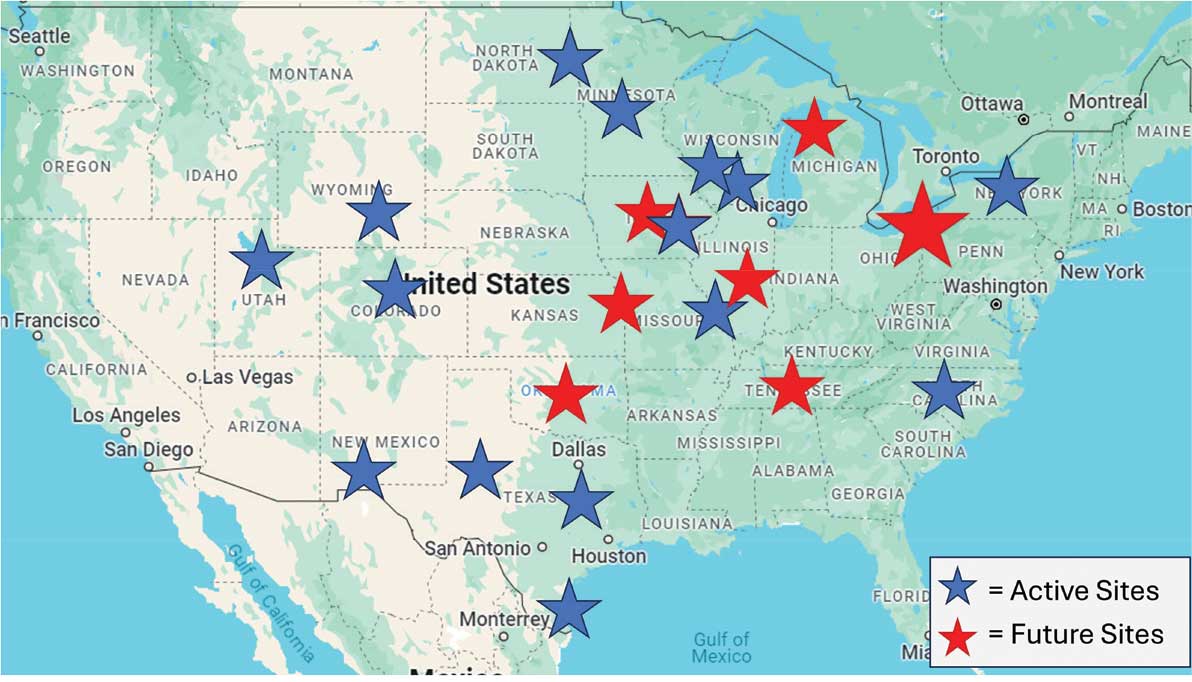

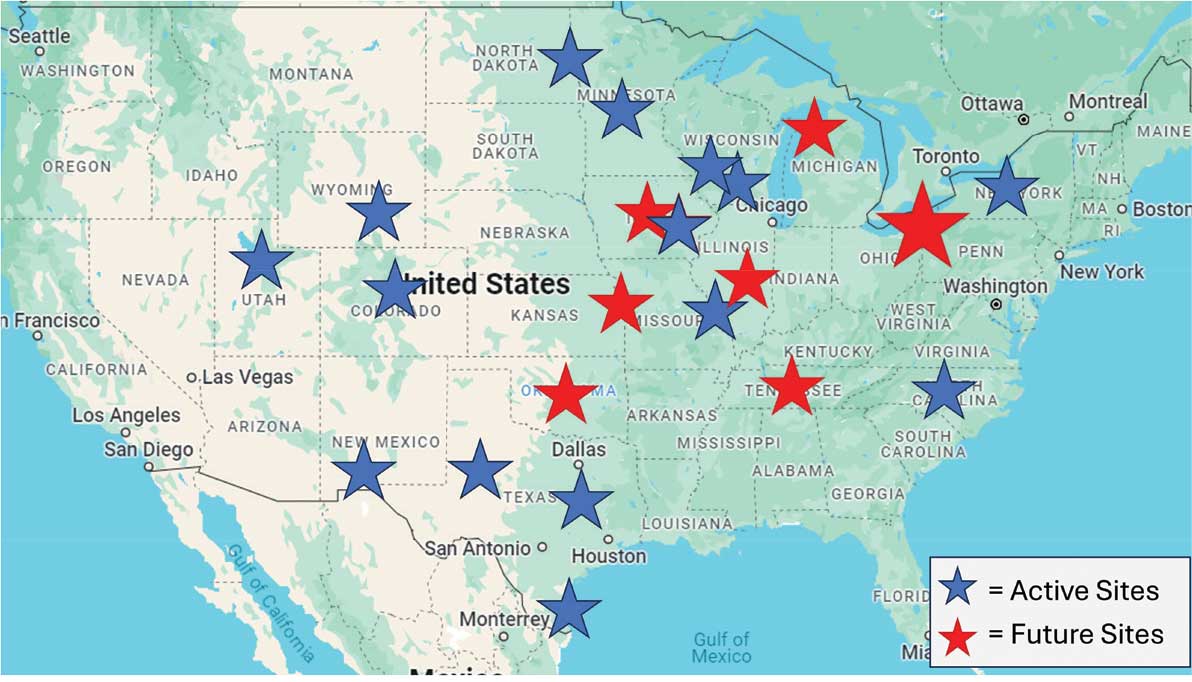

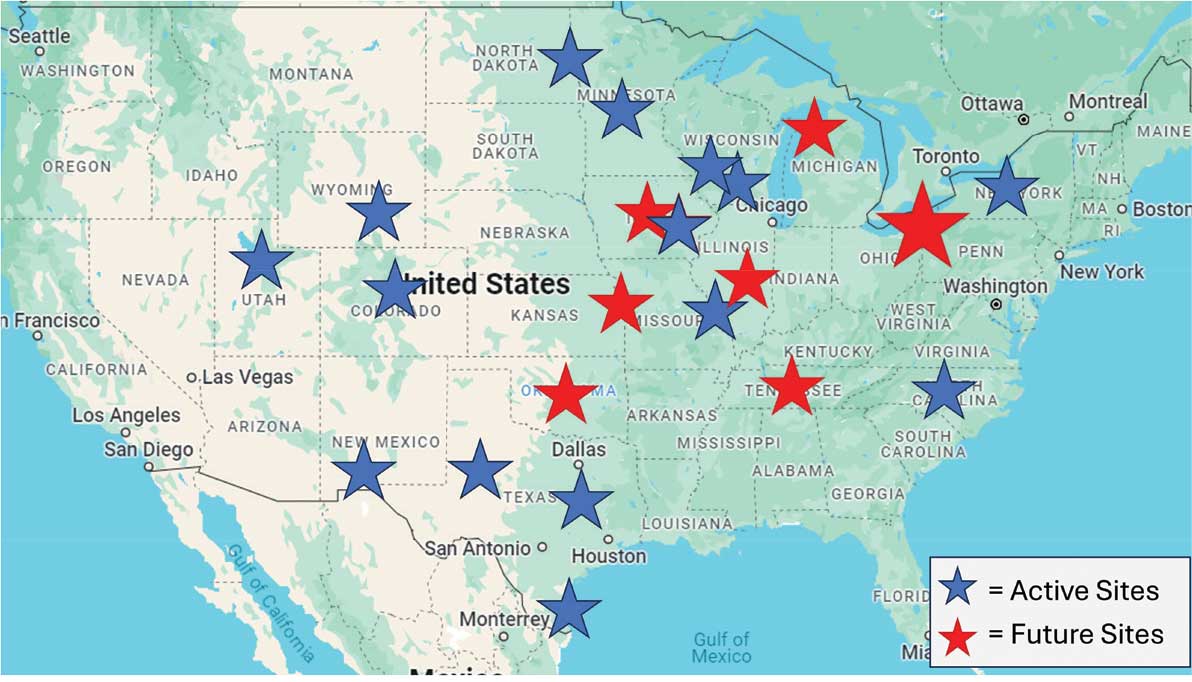

Since June 2023, 15 additional VHA facilities launched Vet-to-Vet programs. As of October 2025, > 350 veterans have participated in ≥ 1 Vet-to-Vet meeting, totaling > 4500 Vet-to-Vet encounters since the program’s inception (Figure 2).

Challenges

The RMRVAMC site and cosite leads are part of the national implementation team and dedicate substantial time to developing the program: 40 and 10 hours per week, respectively. Site leads at new locations do not receive funding for Vet-to-Vet activities and are recommended to dedicate only 4 hours per week to the program. Formally embedding Vet-to-Vet into the site leads’ roles is critical for sustainment.

The Vet-to-Vet model has changed. The initial Vet-to-Vet cohort included the 6-week Taking Charge of My Life and Health curriculum prior to moving to the mutual help format.24 While this curriculum still informs peer facilitator training, it is not used in new groups. It has anecdotally been reported that this change was positive, but the impact of this adaptation is unknown.

This evaluation cohort was small (16 participants) and initial patient reported and administrative outcomes were inconclusive. However, most veterans who stopped participating in Vet-to-Vet spoke fondly of their experiences with the program.

CONCLUSIONS

Vet-to-Vet is a promising new initiative to support self-management and social connection in chronic pain care. The program employs a mutual help approach and storytelling to empower veterans living with chronic pain. The effectiveness of these strategies will be evaluated, which will inform its continued growth. The program's current goals focus on sustainment at existing sites and expansion to new sites to reach more rural veterans across the VA enterprise. While Vet-to-Vet is designed to serve those who experience chronic pain, a partnership with the Office of Whole Health has established goals to begin expanding this model to other chronic conditions in 2026.

- Kerns RD, Philip EJ, Lee AW, Rosenberger PH. Implementation of the Veterans Health Administration national pain management strategy. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1:635-643. doi:10.1007/s13142-011-0094-3

- Pain Management, Opioid Safety, and PDMP (PMOP). US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated August 21, 2025. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://www.va.gov/PAINMANAGEMENT/Providers/IntegratedTeambasedPainCare.asp

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA Directive 2009-053. October 28, 2009. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://www.va.gov/PAINMANAGEMENT/docs/VHA09PainDirective.pdf

- Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016, S524, 114th Cong (2015-2016). Pub L No. 114-198. July 22, 2016. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/524

- Bokhour B, Hyde J, Zeliadt, Mohr D. Whole Health System of Care Evaluation. US Department of Veterans Affairs. February 18, 2020. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/docs/EPCC_WHSevaluation_FinalReport_508.pdf

- Gaudet T, Kligler B. Whole health in the whole system of the veterans administration: how will we know we have reached this future state? J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25:S7-S11. doi:10.1089/acm.2018.29061.gau

- Kelly JF, Yeterian JD. The role of mutual-help groups in extending the framework of treatment. Alcohol Res Health. 2011;33:350-355.

- Humphreys K. Self-help/mutual aid organizations: the view from Mars. Subst Use Misuse. 1997;32:2105-2109. doi:10.3109/10826089709035622

- Chinman M, Kloos B, O’Connell M, Davidson L. Service providers’ views of psychiatric mutual support groups. J Community Psychol. 2002;30:349-366. doi:10.1002/jcop.10010

- Shue SA, McGuire AB, Matthias MS. Facilitators and barriers to implementation of a peer support intervention for patients with chronic pain: a qualitative study. Pain Med. 2019;20:1311-1320. doi:10.1093/pm/pny229

- Pester BD, Tankha H, Caño A, et al. Facing pain together: a randomized controlled trial of the effects of Facebook support groups on adults with chronic pain. J Pain. 2022;23:2121-2134. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2022.07.013

- Matthias MS, McGuire AB, Kukla M, Daggy J, Myers LJ, Bair MJ. A brief peer support intervention for veterans with chronic musculoskeletal pain: a pilot study of feasibility and effectiveness. Pain Med. 2015;16:81-87. doi:10.1111/pme.12571

- Finlay KA, Elander J. Reflecting the transition from pain management services to chronic pain support group attendance: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Br J Health Psychol. 2016;21:660-676. doi:10.1111/bjhp.12194

- Finlay KA, Peacock S, Elander J. Developing successful social support: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of mechanisms and processes in a chronic pain support group. Psychol Health. 2018;33:846-871. doi:10.1080/08870446.2017.1421188

- Farr M, Brant H, Patel R, et al. Experiences of patient-led chronic pain peer support groups after pain management programs: a qualitative study. Pain Med. 2021;22:2884-2895. doi:10.1093/pm/pnab189

- Mehl-Madrona L. Narrative Medicine: The Use of History and Story in the Healing Process. Bear & Company; 2007.

- Fioretti C, Mazzocco K, Riva S, Oliveri S, Masiero M, Pravettoni G. Research studies on patients’ illness experience using the Narrative Medicine approach: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011220. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011220

- Hall JM, Powell J. Understanding the person through narrative. Nurs Res Pract. 2011;2011:293837. doi:10.1155/2011/293837

- Ricks L, Kitchens S, Goodrich T, Hancock E. My story: the use of narrative therapy in individual and group counseling. J Creat Ment Health. 2014;9:99-110. doi:10.1080/15401383.2013.870947

- Hydén L-C. Illness and narrative. Sociol Health Illn. 1997;19:48-69. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.1997.tb00015.x

- Georgiadis E, Johnson MI. Incorporating personal narratives in positive psychology interventions to manage chronic pain. Front Pain Res (Lausanne). 2023;4:1253310. doi:10.3389/fpain.2023.1253310

- Gucciardi E, Jean-Pierre N, Karam G, Sidani S. Designing and delivering facilitated storytelling interventions for chronic disease self-management: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:249. doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1474-7

- Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1322-1327. doi:10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322

- Abadi M, Richard B, Shamblen S, et al. Achieving whole health: a preliminary study of TCMLH, a group-based program promoting self-care and empowerment among veterans. Health Educ Behav. 2022;49:347-357. doi:10.1177/10901981211011043

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has continued to advance its understanding and treatment of chronic pain. The VHA National Pain Management Strategy emphasizes the significance of the social context of pain while underscoring the importance of self-management.1 This established strategy ensures that all veterans have access to the appropriate pain care in the proper setting.2 VHA has instituted a stepped care model of pain management, delineating the domains of primary care, secondary consultative services, and tertiary care.3 This directive emphasized a biopsychosocial approach to pain management to prioritize the relationship between biological, psychological, and social factors that influence how veterans experience pain and should commensurately influence how it is managed.

The VHA Office of Patient-Centered Care and Cultural Transformation implemented the Whole Health System of Care as part of the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, which included a VHA directive to expand pain management.4,5 Reorientation within this system shifts from defining veterans as passive care recipients to viewing them as active partners in their own care and health. This partnership places additional emphasis on peer-led explorations of mission, aspiration, and purpose.6

Peer-led groups, also known as mutual aid, mutual support, and mutual help groups, have historically been successful for patients undergoing treatment for substance use disorders (eg, Alcoholics Anonymous).7 Mutual help groups have 3 defining characteristics. First, they are run by participants, not professionals, though the latter may have been integral in the founding of the groups. Second, participants share a similar problem (eg, disease state, experience, disposition). Finally, there is a reciprocal exchange of information and psychological support among participants.8,9 Mutual help groups that address chronic pain are rare but becoming more common.10-12 Emerging evidence suggests a positive relationship between peer support and improved well-being, self-efficacy, pain management, and pain self-management skills (eg, activity pacing).13-15

Storytelling as a tool for healing has a long history in indigenous and Western medical traditions.16-19 This includes the treatment of chronic disease, including pain.20,21 The use of storytelling in health care overlaps with the role it plays within many mutual help groups focused on chronic disease treatment.22 Storytelling allows an individual to share their experience with a disease, and take a more active role in their health, and facilitate stronger bonds with others.22 In effect, storytelling is not only important to group cohesion—it also plays a role in an individual’s healing.

Vet-to-Vet

The VHA Office of Rural Health funds Vet-to-Vet, a peer-to-peer program to address limited access to care for rural veterans with chronic pain. Similar to the VHA National Pain Management Strategy, Vet-to-Vet is grounded in the significance of the social context of pain and underscores the importance of self-management.1 The program combines pain care, mutual help, and storytelling to support veterans living with chronic pain. While the primary focus of Vet-to-Vet is rural veterans, the program serves any veteran experiencing chronic pain who is isolated from services, including home-bound urban veterans.

Following mutual help principles, Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators lead weekly online drop-in meetings. Meetings follow the general structure of reiterating group ground rules and sharing an individual pain story, followed by open discussions centered on well-being, chronic pain management, or any topic the group wishes to discuss. Meetings typically end with a mindfulness exercise. The organizational structure that supports Vet-to-Vet includes the implementation support team, site leads, Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators, and national partners (Figure 1).

Implementation Support Team

The implementation support team consists of a principal investigator, coinvestigator, program manager, and program support specialist. The team provides facilitator training, monthly community practice sessions for Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators and site leads, and weekly office hours for site leads. The implementation support team also recruits new Vet-to-Vet sites; potential new locations ideally have an existing whole health program, leadership support, committed site and cosite leads, and ≥ 3 peer facilitator volunteers.

Site Leads

Most site and cosite leads are based in whole health or pain management teams and are whole health coaches or peer support specialists. The site lead is responsible for standing up the program and documenting encounters, recruiting and supporting peer facilitators and participants, and overseeing the meeting. During meetings, site leads generally leave their cameras off and only speak when called into the group; the peer facilitators lead the meetings. The implementation support team recommends that site leads dedicate ≥ 4 hours per week to Vet-to-Vet; 2 hours for weekly group meetings and 2 hours for documentation (ie, entering notes into the participants’ electronic health records) and supporting peer facilitators and participants. Cosite lead responsibilities vary by location, with some sites having 2 leads that equally share duties and others having a primary lead and a colead available if the site lead is unable to attend a meeting.

Vet-to-Vet Peer Facilitators

Peer facilitators are the core of the program. They lead meetings from start to finish. Like participants, they also experience chronic pain and are volunteers. The implementation support team encourages sites to establish volunteer peer facilitators, rather than assigning peer support specialists to facilitate meetings. Veterans are eager to connect and give back to their communities, and the Vet-to-Vet peer facilitator role is an opportunity for those unable to work to connect with peers and add meaning to their lives. Even if a VHA employee is a veteran who has chronic pain, they are not eligible to serve as this could create a service provider/service recipient dynamic that is not in the spirit of mutual help.

Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators attend a virtual 3-day training held by the implementation support team prior to starting. These training sessions are available on a quarterly basis and facilitated by the Vet-to-Vet program manager and 2 current peer facilitators. Training content includes established whole health facilitator training materials and program-specific storytelling training materials. Once trained, peer facilitators attend storytelling practice sessions and collaborate with their site leads during weekly meetings.

Participants

Vet-to-Vet participants find the program through direct outreach from site leads, word of mouth, and referrals. The only criteria to join are that the individual is a veteran who experiences chronic pain and is enrolled in the VHA (site leads can assist with enrollment if needed). Participants are not required to have a diagnosis or engage in any other health care. There is no commitment and no end date. Some participants only come once; others have attended for > 3 years. This approach is intended to embrace the idea that the need for support ebbs and flows.

National Partners

The VHA Office of Rural Health provides technical support. The Center for Development and Civic Engagement onboards peer facilitators as VHA volunteers. The Office of Patient-Centered Care and Cultural Transformation provides national guidance and site-level collaboration. The VHA Pain Management, Opioid Safety, and Prescription Drug Monitoring Program supports site recruitment. In addition to the VHA partners, 4 veteran evaluation consultants who have experience with chronic pain but do not participate in Vet-to-Vet meetings provide advice on evaluation activities, such as question development and communication strategies.

Evaluation

This evaluation shares preliminary results from a pilot evaluation of the Rocky Mountain Regional VA Medical Center (RMRVAMC) Vet-to-Vet group. It is intended for program improvement, was deemed nonresearch by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board, and was structured using the RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance) framework.23 This evaluation focused on capturing measures related to reach and effectiveness, while a forthcoming evaluation includes elements of adoption, implementation, and maintenance.

In 2022, 16 Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators and participants completed surveys and interviews to share their experience. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded in ATLAS.ti. A priori codes were based on interview guide questions and emergent descriptive codes were used to identify specific topics which were categorized into RE-AIM domains, barriers, facilitators, what participants learned, how participants applied what they learned to their lives, and participant reported outcomes. This article contains high-level findings from the evaluation; more detailed results will be included in the ongoing evaluation.

Results

The RMRVAMC Vet-to-Vet group has met weekly since April 2022. Four Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators and 12 individuals participated in the pilot Vet-to-Vet group and evaluation. The mean age was 62 years, most were men, and half were married. Most participants lived in rural areas with a mean distance of 125 miles to the nearest VAMC. Many experienced multiple kinds of pain, with a mean 4.5 on a 10-point scale (bothered “a lot”). All participants reported that they experienced pain daily.

Participation in Vet-to-Vet meetings was high; 3 of 4 peer facilitators and 7 of 12 participants completed the first 6 months of the program. In interviews, participants described the positive impact of the program. They emphasized the importance of connecting with other veterans and helping one another, with one noting that opportunities to connect with other veterans “just drops off a lot” (peer facilitator 3) after leaving active duty.

Some participants and Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators outlined the content of the sessions (eg, learning about how pain impacts the body and one’s family relationships) and shared the skills they learned (eg, goal setting, self-advocacy) (Table). Most spoke about learning from one another and the power of sharing stories with one peer facilitator sharing how they felt that witnessing another participant’s story “really shifted how I was thinking about things and how I perceived people” (peer facilitator 1).

Participants reported several ways the program impacted their lives, such as learning that they could get help, how to get help, and how to overcome the mental aspects of chronic pain. One veteran shared profound health impacts and attributed the Vet-to-Vet program to having one of the best years of their life. Even those who did not attend many meetings spoke of it positively and stated that it should continue so others could try (Table).

From January 2022 to September 2025, > 80 veterans attended ≥ 1 meeting at RMRVAMC; 29 attended ≥ 1 meeting in the last quarter. There were > 1400 Vet-to-Vet encounters at RMRVAMC, with a mean (SD) of 14.2 (19.2) and a median of 4.5 encounters per participant. Half of the veterans attend ≥ 5 meetings, and one-third attended ≥ 10 meetings.

Since June 2023, 15 additional VHA facilities launched Vet-to-Vet programs. As of October 2025, > 350 veterans have participated in ≥ 1 Vet-to-Vet meeting, totaling > 4500 Vet-to-Vet encounters since the program’s inception (Figure 2).

Challenges

The RMRVAMC site and cosite leads are part of the national implementation team and dedicate substantial time to developing the program: 40 and 10 hours per week, respectively. Site leads at new locations do not receive funding for Vet-to-Vet activities and are recommended to dedicate only 4 hours per week to the program. Formally embedding Vet-to-Vet into the site leads’ roles is critical for sustainment.

The Vet-to-Vet model has changed. The initial Vet-to-Vet cohort included the 6-week Taking Charge of My Life and Health curriculum prior to moving to the mutual help format.24 While this curriculum still informs peer facilitator training, it is not used in new groups. It has anecdotally been reported that this change was positive, but the impact of this adaptation is unknown.

This evaluation cohort was small (16 participants) and initial patient reported and administrative outcomes were inconclusive. However, most veterans who stopped participating in Vet-to-Vet spoke fondly of their experiences with the program.

CONCLUSIONS

Vet-to-Vet is a promising new initiative to support self-management and social connection in chronic pain care. The program employs a mutual help approach and storytelling to empower veterans living with chronic pain. The effectiveness of these strategies will be evaluated, which will inform its continued growth. The program's current goals focus on sustainment at existing sites and expansion to new sites to reach more rural veterans across the VA enterprise. While Vet-to-Vet is designed to serve those who experience chronic pain, a partnership with the Office of Whole Health has established goals to begin expanding this model to other chronic conditions in 2026.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has continued to advance its understanding and treatment of chronic pain. The VHA National Pain Management Strategy emphasizes the significance of the social context of pain while underscoring the importance of self-management.1 This established strategy ensures that all veterans have access to the appropriate pain care in the proper setting.2 VHA has instituted a stepped care model of pain management, delineating the domains of primary care, secondary consultative services, and tertiary care.3 This directive emphasized a biopsychosocial approach to pain management to prioritize the relationship between biological, psychological, and social factors that influence how veterans experience pain and should commensurately influence how it is managed.

The VHA Office of Patient-Centered Care and Cultural Transformation implemented the Whole Health System of Care as part of the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, which included a VHA directive to expand pain management.4,5 Reorientation within this system shifts from defining veterans as passive care recipients to viewing them as active partners in their own care and health. This partnership places additional emphasis on peer-led explorations of mission, aspiration, and purpose.6

Peer-led groups, also known as mutual aid, mutual support, and mutual help groups, have historically been successful for patients undergoing treatment for substance use disorders (eg, Alcoholics Anonymous).7 Mutual help groups have 3 defining characteristics. First, they are run by participants, not professionals, though the latter may have been integral in the founding of the groups. Second, participants share a similar problem (eg, disease state, experience, disposition). Finally, there is a reciprocal exchange of information and psychological support among participants.8,9 Mutual help groups that address chronic pain are rare but becoming more common.10-12 Emerging evidence suggests a positive relationship between peer support and improved well-being, self-efficacy, pain management, and pain self-management skills (eg, activity pacing).13-15

Storytelling as a tool for healing has a long history in indigenous and Western medical traditions.16-19 This includes the treatment of chronic disease, including pain.20,21 The use of storytelling in health care overlaps with the role it plays within many mutual help groups focused on chronic disease treatment.22 Storytelling allows an individual to share their experience with a disease, and take a more active role in their health, and facilitate stronger bonds with others.22 In effect, storytelling is not only important to group cohesion—it also plays a role in an individual’s healing.

Vet-to-Vet

The VHA Office of Rural Health funds Vet-to-Vet, a peer-to-peer program to address limited access to care for rural veterans with chronic pain. Similar to the VHA National Pain Management Strategy, Vet-to-Vet is grounded in the significance of the social context of pain and underscores the importance of self-management.1 The program combines pain care, mutual help, and storytelling to support veterans living with chronic pain. While the primary focus of Vet-to-Vet is rural veterans, the program serves any veteran experiencing chronic pain who is isolated from services, including home-bound urban veterans.

Following mutual help principles, Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators lead weekly online drop-in meetings. Meetings follow the general structure of reiterating group ground rules and sharing an individual pain story, followed by open discussions centered on well-being, chronic pain management, or any topic the group wishes to discuss. Meetings typically end with a mindfulness exercise. The organizational structure that supports Vet-to-Vet includes the implementation support team, site leads, Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators, and national partners (Figure 1).

Implementation Support Team

The implementation support team consists of a principal investigator, coinvestigator, program manager, and program support specialist. The team provides facilitator training, monthly community practice sessions for Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators and site leads, and weekly office hours for site leads. The implementation support team also recruits new Vet-to-Vet sites; potential new locations ideally have an existing whole health program, leadership support, committed site and cosite leads, and ≥ 3 peer facilitator volunteers.

Site Leads

Most site and cosite leads are based in whole health or pain management teams and are whole health coaches or peer support specialists. The site lead is responsible for standing up the program and documenting encounters, recruiting and supporting peer facilitators and participants, and overseeing the meeting. During meetings, site leads generally leave their cameras off and only speak when called into the group; the peer facilitators lead the meetings. The implementation support team recommends that site leads dedicate ≥ 4 hours per week to Vet-to-Vet; 2 hours for weekly group meetings and 2 hours for documentation (ie, entering notes into the participants’ electronic health records) and supporting peer facilitators and participants. Cosite lead responsibilities vary by location, with some sites having 2 leads that equally share duties and others having a primary lead and a colead available if the site lead is unable to attend a meeting.

Vet-to-Vet Peer Facilitators

Peer facilitators are the core of the program. They lead meetings from start to finish. Like participants, they also experience chronic pain and are volunteers. The implementation support team encourages sites to establish volunteer peer facilitators, rather than assigning peer support specialists to facilitate meetings. Veterans are eager to connect and give back to their communities, and the Vet-to-Vet peer facilitator role is an opportunity for those unable to work to connect with peers and add meaning to their lives. Even if a VHA employee is a veteran who has chronic pain, they are not eligible to serve as this could create a service provider/service recipient dynamic that is not in the spirit of mutual help.

Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators attend a virtual 3-day training held by the implementation support team prior to starting. These training sessions are available on a quarterly basis and facilitated by the Vet-to-Vet program manager and 2 current peer facilitators. Training content includes established whole health facilitator training materials and program-specific storytelling training materials. Once trained, peer facilitators attend storytelling practice sessions and collaborate with their site leads during weekly meetings.

Participants

Vet-to-Vet participants find the program through direct outreach from site leads, word of mouth, and referrals. The only criteria to join are that the individual is a veteran who experiences chronic pain and is enrolled in the VHA (site leads can assist with enrollment if needed). Participants are not required to have a diagnosis or engage in any other health care. There is no commitment and no end date. Some participants only come once; others have attended for > 3 years. This approach is intended to embrace the idea that the need for support ebbs and flows.

National Partners

The VHA Office of Rural Health provides technical support. The Center for Development and Civic Engagement onboards peer facilitators as VHA volunteers. The Office of Patient-Centered Care and Cultural Transformation provides national guidance and site-level collaboration. The VHA Pain Management, Opioid Safety, and Prescription Drug Monitoring Program supports site recruitment. In addition to the VHA partners, 4 veteran evaluation consultants who have experience with chronic pain but do not participate in Vet-to-Vet meetings provide advice on evaluation activities, such as question development and communication strategies.

Evaluation

This evaluation shares preliminary results from a pilot evaluation of the Rocky Mountain Regional VA Medical Center (RMRVAMC) Vet-to-Vet group. It is intended for program improvement, was deemed nonresearch by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board, and was structured using the RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance) framework.23 This evaluation focused on capturing measures related to reach and effectiveness, while a forthcoming evaluation includes elements of adoption, implementation, and maintenance.

In 2022, 16 Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators and participants completed surveys and interviews to share their experience. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded in ATLAS.ti. A priori codes were based on interview guide questions and emergent descriptive codes were used to identify specific topics which were categorized into RE-AIM domains, barriers, facilitators, what participants learned, how participants applied what they learned to their lives, and participant reported outcomes. This article contains high-level findings from the evaluation; more detailed results will be included in the ongoing evaluation.

Results

The RMRVAMC Vet-to-Vet group has met weekly since April 2022. Four Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators and 12 individuals participated in the pilot Vet-to-Vet group and evaluation. The mean age was 62 years, most were men, and half were married. Most participants lived in rural areas with a mean distance of 125 miles to the nearest VAMC. Many experienced multiple kinds of pain, with a mean 4.5 on a 10-point scale (bothered “a lot”). All participants reported that they experienced pain daily.

Participation in Vet-to-Vet meetings was high; 3 of 4 peer facilitators and 7 of 12 participants completed the first 6 months of the program. In interviews, participants described the positive impact of the program. They emphasized the importance of connecting with other veterans and helping one another, with one noting that opportunities to connect with other veterans “just drops off a lot” (peer facilitator 3) after leaving active duty.

Some participants and Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators outlined the content of the sessions (eg, learning about how pain impacts the body and one’s family relationships) and shared the skills they learned (eg, goal setting, self-advocacy) (Table). Most spoke about learning from one another and the power of sharing stories with one peer facilitator sharing how they felt that witnessing another participant’s story “really shifted how I was thinking about things and how I perceived people” (peer facilitator 1).

Participants reported several ways the program impacted their lives, such as learning that they could get help, how to get help, and how to overcome the mental aspects of chronic pain. One veteran shared profound health impacts and attributed the Vet-to-Vet program to having one of the best years of their life. Even those who did not attend many meetings spoke of it positively and stated that it should continue so others could try (Table).

From January 2022 to September 2025, > 80 veterans attended ≥ 1 meeting at RMRVAMC; 29 attended ≥ 1 meeting in the last quarter. There were > 1400 Vet-to-Vet encounters at RMRVAMC, with a mean (SD) of 14.2 (19.2) and a median of 4.5 encounters per participant. Half of the veterans attend ≥ 5 meetings, and one-third attended ≥ 10 meetings.

Since June 2023, 15 additional VHA facilities launched Vet-to-Vet programs. As of October 2025, > 350 veterans have participated in ≥ 1 Vet-to-Vet meeting, totaling > 4500 Vet-to-Vet encounters since the program’s inception (Figure 2).

Challenges

The RMRVAMC site and cosite leads are part of the national implementation team and dedicate substantial time to developing the program: 40 and 10 hours per week, respectively. Site leads at new locations do not receive funding for Vet-to-Vet activities and are recommended to dedicate only 4 hours per week to the program. Formally embedding Vet-to-Vet into the site leads’ roles is critical for sustainment.

The Vet-to-Vet model has changed. The initial Vet-to-Vet cohort included the 6-week Taking Charge of My Life and Health curriculum prior to moving to the mutual help format.24 While this curriculum still informs peer facilitator training, it is not used in new groups. It has anecdotally been reported that this change was positive, but the impact of this adaptation is unknown.

This evaluation cohort was small (16 participants) and initial patient reported and administrative outcomes were inconclusive. However, most veterans who stopped participating in Vet-to-Vet spoke fondly of their experiences with the program.

CONCLUSIONS

Vet-to-Vet is a promising new initiative to support self-management and social connection in chronic pain care. The program employs a mutual help approach and storytelling to empower veterans living with chronic pain. The effectiveness of these strategies will be evaluated, which will inform its continued growth. The program's current goals focus on sustainment at existing sites and expansion to new sites to reach more rural veterans across the VA enterprise. While Vet-to-Vet is designed to serve those who experience chronic pain, a partnership with the Office of Whole Health has established goals to begin expanding this model to other chronic conditions in 2026.

- Kerns RD, Philip EJ, Lee AW, Rosenberger PH. Implementation of the Veterans Health Administration national pain management strategy. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1:635-643. doi:10.1007/s13142-011-0094-3

- Pain Management, Opioid Safety, and PDMP (PMOP). US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated August 21, 2025. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://www.va.gov/PAINMANAGEMENT/Providers/IntegratedTeambasedPainCare.asp

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA Directive 2009-053. October 28, 2009. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://www.va.gov/PAINMANAGEMENT/docs/VHA09PainDirective.pdf

- Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016, S524, 114th Cong (2015-2016). Pub L No. 114-198. July 22, 2016. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/524

- Bokhour B, Hyde J, Zeliadt, Mohr D. Whole Health System of Care Evaluation. US Department of Veterans Affairs. February 18, 2020. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/docs/EPCC_WHSevaluation_FinalReport_508.pdf

- Gaudet T, Kligler B. Whole health in the whole system of the veterans administration: how will we know we have reached this future state? J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25:S7-S11. doi:10.1089/acm.2018.29061.gau

- Kelly JF, Yeterian JD. The role of mutual-help groups in extending the framework of treatment. Alcohol Res Health. 2011;33:350-355.

- Humphreys K. Self-help/mutual aid organizations: the view from Mars. Subst Use Misuse. 1997;32:2105-2109. doi:10.3109/10826089709035622

- Chinman M, Kloos B, O’Connell M, Davidson L. Service providers’ views of psychiatric mutual support groups. J Community Psychol. 2002;30:349-366. doi:10.1002/jcop.10010

- Shue SA, McGuire AB, Matthias MS. Facilitators and barriers to implementation of a peer support intervention for patients with chronic pain: a qualitative study. Pain Med. 2019;20:1311-1320. doi:10.1093/pm/pny229

- Pester BD, Tankha H, Caño A, et al. Facing pain together: a randomized controlled trial of the effects of Facebook support groups on adults with chronic pain. J Pain. 2022;23:2121-2134. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2022.07.013

- Matthias MS, McGuire AB, Kukla M, Daggy J, Myers LJ, Bair MJ. A brief peer support intervention for veterans with chronic musculoskeletal pain: a pilot study of feasibility and effectiveness. Pain Med. 2015;16:81-87. doi:10.1111/pme.12571

- Finlay KA, Elander J. Reflecting the transition from pain management services to chronic pain support group attendance: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Br J Health Psychol. 2016;21:660-676. doi:10.1111/bjhp.12194

- Finlay KA, Peacock S, Elander J. Developing successful social support: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of mechanisms and processes in a chronic pain support group. Psychol Health. 2018;33:846-871. doi:10.1080/08870446.2017.1421188

- Farr M, Brant H, Patel R, et al. Experiences of patient-led chronic pain peer support groups after pain management programs: a qualitative study. Pain Med. 2021;22:2884-2895. doi:10.1093/pm/pnab189

- Mehl-Madrona L. Narrative Medicine: The Use of History and Story in the Healing Process. Bear & Company; 2007.

- Fioretti C, Mazzocco K, Riva S, Oliveri S, Masiero M, Pravettoni G. Research studies on patients’ illness experience using the Narrative Medicine approach: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011220. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011220

- Hall JM, Powell J. Understanding the person through narrative. Nurs Res Pract. 2011;2011:293837. doi:10.1155/2011/293837

- Ricks L, Kitchens S, Goodrich T, Hancock E. My story: the use of narrative therapy in individual and group counseling. J Creat Ment Health. 2014;9:99-110. doi:10.1080/15401383.2013.870947

- Hydén L-C. Illness and narrative. Sociol Health Illn. 1997;19:48-69. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.1997.tb00015.x

- Georgiadis E, Johnson MI. Incorporating personal narratives in positive psychology interventions to manage chronic pain. Front Pain Res (Lausanne). 2023;4:1253310. doi:10.3389/fpain.2023.1253310

- Gucciardi E, Jean-Pierre N, Karam G, Sidani S. Designing and delivering facilitated storytelling interventions for chronic disease self-management: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:249. doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1474-7

- Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1322-1327. doi:10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322

- Abadi M, Richard B, Shamblen S, et al. Achieving whole health: a preliminary study of TCMLH, a group-based program promoting self-care and empowerment among veterans. Health Educ Behav. 2022;49:347-357. doi:10.1177/10901981211011043

- Kerns RD, Philip EJ, Lee AW, Rosenberger PH. Implementation of the Veterans Health Administration national pain management strategy. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1:635-643. doi:10.1007/s13142-011-0094-3

- Pain Management, Opioid Safety, and PDMP (PMOP). US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated August 21, 2025. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://www.va.gov/PAINMANAGEMENT/Providers/IntegratedTeambasedPainCare.asp

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA Directive 2009-053. October 28, 2009. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://www.va.gov/PAINMANAGEMENT/docs/VHA09PainDirective.pdf

- Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016, S524, 114th Cong (2015-2016). Pub L No. 114-198. July 22, 2016. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/524

- Bokhour B, Hyde J, Zeliadt, Mohr D. Whole Health System of Care Evaluation. US Department of Veterans Affairs. February 18, 2020. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/docs/EPCC_WHSevaluation_FinalReport_508.pdf

- Gaudet T, Kligler B. Whole health in the whole system of the veterans administration: how will we know we have reached this future state? J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25:S7-S11. doi:10.1089/acm.2018.29061.gau

- Kelly JF, Yeterian JD. The role of mutual-help groups in extending the framework of treatment. Alcohol Res Health. 2011;33:350-355.

- Humphreys K. Self-help/mutual aid organizations: the view from Mars. Subst Use Misuse. 1997;32:2105-2109. doi:10.3109/10826089709035622

- Chinman M, Kloos B, O’Connell M, Davidson L. Service providers’ views of psychiatric mutual support groups. J Community Psychol. 2002;30:349-366. doi:10.1002/jcop.10010

- Shue SA, McGuire AB, Matthias MS. Facilitators and barriers to implementation of a peer support intervention for patients with chronic pain: a qualitative study. Pain Med. 2019;20:1311-1320. doi:10.1093/pm/pny229

- Pester BD, Tankha H, Caño A, et al. Facing pain together: a randomized controlled trial of the effects of Facebook support groups on adults with chronic pain. J Pain. 2022;23:2121-2134. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2022.07.013

- Matthias MS, McGuire AB, Kukla M, Daggy J, Myers LJ, Bair MJ. A brief peer support intervention for veterans with chronic musculoskeletal pain: a pilot study of feasibility and effectiveness. Pain Med. 2015;16:81-87. doi:10.1111/pme.12571

- Finlay KA, Elander J. Reflecting the transition from pain management services to chronic pain support group attendance: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Br J Health Psychol. 2016;21:660-676. doi:10.1111/bjhp.12194

- Finlay KA, Peacock S, Elander J. Developing successful social support: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of mechanisms and processes in a chronic pain support group. Psychol Health. 2018;33:846-871. doi:10.1080/08870446.2017.1421188

- Farr M, Brant H, Patel R, et al. Experiences of patient-led chronic pain peer support groups after pain management programs: a qualitative study. Pain Med. 2021;22:2884-2895. doi:10.1093/pm/pnab189

- Mehl-Madrona L. Narrative Medicine: The Use of History and Story in the Healing Process. Bear & Company; 2007.

- Fioretti C, Mazzocco K, Riva S, Oliveri S, Masiero M, Pravettoni G. Research studies on patients’ illness experience using the Narrative Medicine approach: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011220. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011220

- Hall JM, Powell J. Understanding the person through narrative. Nurs Res Pract. 2011;2011:293837. doi:10.1155/2011/293837

- Ricks L, Kitchens S, Goodrich T, Hancock E. My story: the use of narrative therapy in individual and group counseling. J Creat Ment Health. 2014;9:99-110. doi:10.1080/15401383.2013.870947

- Hydén L-C. Illness and narrative. Sociol Health Illn. 1997;19:48-69. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.1997.tb00015.x

- Georgiadis E, Johnson MI. Incorporating personal narratives in positive psychology interventions to manage chronic pain. Front Pain Res (Lausanne). 2023;4:1253310. doi:10.3389/fpain.2023.1253310

- Gucciardi E, Jean-Pierre N, Karam G, Sidani S. Designing and delivering facilitated storytelling interventions for chronic disease self-management: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:249. doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1474-7

- Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1322-1327. doi:10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322

- Abadi M, Richard B, Shamblen S, et al. Achieving whole health: a preliminary study of TCMLH, a group-based program promoting self-care and empowerment among veterans. Health Educ Behav. 2022;49:347-357. doi:10.1177/10901981211011043

A True Community: The Vet-to-Vet Program for Chronic Pain

A True Community: The Vet-to-Vet Program for Chronic Pain

Satisfaction With Department of Veterans Affairs Prosthetics and Support Services as Reported by Women and Men Veterans

Satisfaction With Department of Veterans Affairs Prosthetics and Support Services as Reported by Women and Men Veterans

Limb loss is a significant and growing concern in the United States. Nearly 2 million Americans are living with limb loss, and up to 185,000 people undergo amputations annually.1-4 Of these patients, about 35% are women.5 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) provides about 10% of US amputations.6-8 Between 2015 and 2019, the number of prosthetic devices provided to female veterans increased from 3.3 million to 4.6 million.5,9,10

Previous research identified disparities in prosthetic care between men and women, both within and outside the VHA. These disparities include slower prosthesis prescription and receipt among women, in addition to differences in self-reported mobility, satisfaction, rates of prosthesis rejection, and challenges related to prosthesis appearance and fit.5,10,11 Recent studies suggest women tend to have worse outcomes following amputation, and are underrepresented in amputation research.12,13 However, these disparities are poorly described in a large, national sample. Because women represent a growing portion of patients with limb loss in the VHA, understanding their needs is critical.14

The Johnny Isakson and David P. Roe, MD Veterans Health Care and Benefits Improvement Act of 2020 was enacted, in part, to improve the care provided to women veterans.15 The law required the VHA to conduct a survey of ≥ 50,000 veterans to assess the satisfaction of women veterans with prostheses provided by the VHA. To comply with this legislation and understand how women veterans rate their prostheses and related care in the VHA, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Center for Collaborative Evaluation (VACE) conducted a large national survey of veterans with limb loss that oversampled women veterans. This article describes the survey results, including characteristics of female veterans with limb loss receiving care from the VHA, assesses their satisfaction with prostheses and prosthetic care, and highlights where their responses differ from those of male veterans.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional, mixedmode survey of eligible amputees in the VHA Support Service Capital Assets Amputee Data Cube. We identified a cohort of veterans with any major amputation (above the ankle or wrist) or partial hand or foot amputation who received VHA care between October 1, 2019, and September 30, 2020. The final cohort yielded 46,646 potentially eligible veterans. Thirty-three had invalid contact information, leaving 46,613 veterans who were asked to participate, including 1356 women.

Survey

We created a survey instrument de novo that included questions from validated instruments, including the Trinity Amputation Prosthesis and Experience Scales to assess prosthetic device satisfaction, the Prosthesis Evaluation Questionnaire to assess quality of life (QOL) satisfaction, and the Orthotics Prosthetics Users Survey to assess prosthesis-related care satisfaction. 16-18 Additional questions were incorporated from a survey of veterans with upper limb amputation to assess the importance of cosmetic considerations related to the prosthesis and comfort with prosthesis use in intimate relationships.19 Questions were also included to assess amputation type, year of amputation, if a prosthesis was currently used, reasons for ceasing use of a prosthesis, reasons for never using a prosthesis, the types of prostheses used, intensity of prosthesis use, satisfaction with time required to receive a prosthetic limb, and if the prosthesis reflected the veteran’s selfidentified gender. Veterans were asked to answer questions based on their most recent amputation.

We tested the survey using cognitive interviews with 6 veterans to refine the survey and better understand how veterans interpreted the questions. Pilot testers completed the survey and participated in individual interviews with experienced interviewers (CL and RRK) to describe how they selected their responses.20 This feedback was used to refine the survey. The online survey was programmed using Qualtrics Software and manually translated into Spanish.

Given the multimodal design, surveys were distributed by email, text message, and US Postal Service (USPS). Surveys were emailed to all veterans for whom a valid email address was available. If emails were undeliverable, veterans were contacted via text message or the USPS. Surveys were distributed by text message to all veterans without an email address but with a cellphone number. We were unable to consistently identify invalid numbers among all text message recipients. Invitations with a survey URL and QR code were sent via USPS to veterans who had no valid email address or cellphone number. Targeted efforts were made to increase the response rate for women. A random sample of 200 women who had not completed the survey 2 weeks prior to the closing date (15% of women in sample) was selected to receive personal phone calls. Another random sample of 400 women was selected to receive personalized outreach emails. The survey data were confidential, and responses could not be traced to identifying information.

Data Analyses

We conducted a descriptive analysis, including percentages and means for responses to variables focused on describing amputation characteristics, prosthesis characteristics, and QOL. All data, including missing values, were used to document the percentage of respondents for each question. Removing missing data from the denominator when calculating percentages could introduce bias to the analysis because we cannot be certain data are missing at random. Missing variables were removed to avoid underinflation of mean scores.

We compared responses across 2 groups: individuals who self-identified as men and individuals who self-identified as women. For each question, we assessed whether each of these groups differed significantly from the remaining sample. For example, we examined whether the percentage of men who answered affirmatively to a question was significantly higher or lower than that of individuals not identifying as male, and whether the percentage of women who answered affirmatively was significantly higher or lower than that of individuals not identifying as female. We utilized x2 tests to determine significant differences for percentage calculations and t tests to determine significant differences in means across gender.

Since conducting multiple comparisons within a dataset may result in inflating statistical significance (type 1 errors), we used a more conservative estimate of statistical significance (α = 0.01) and high significance (α = 0.001). This study was deemed quality improvement by the VHA Rehabilitation and Prosthetic Services (12RPS) and acknowledged by the VA Research Office at Eastern Colorado Health Care System and was not subject to institutional review board review.

Results

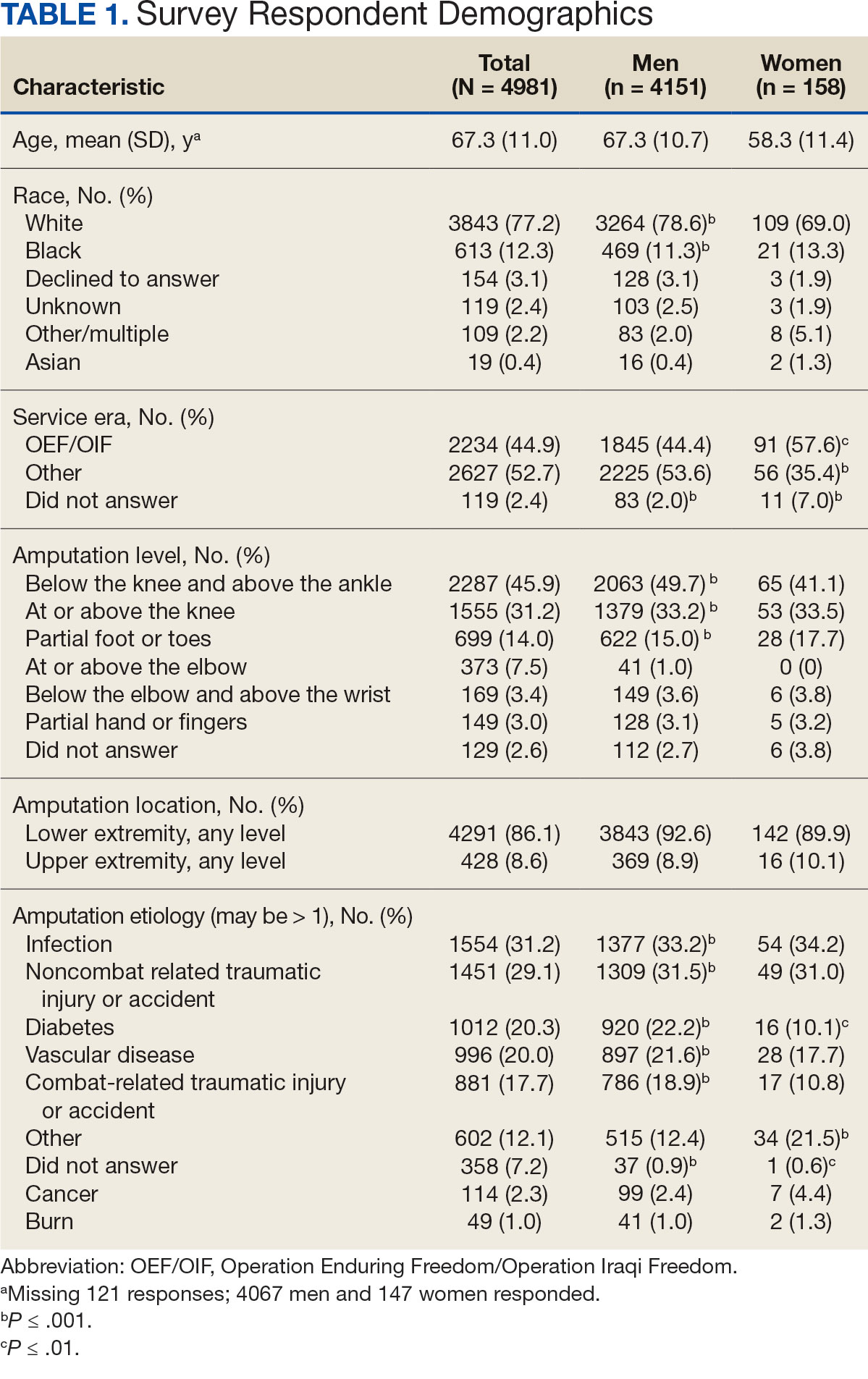

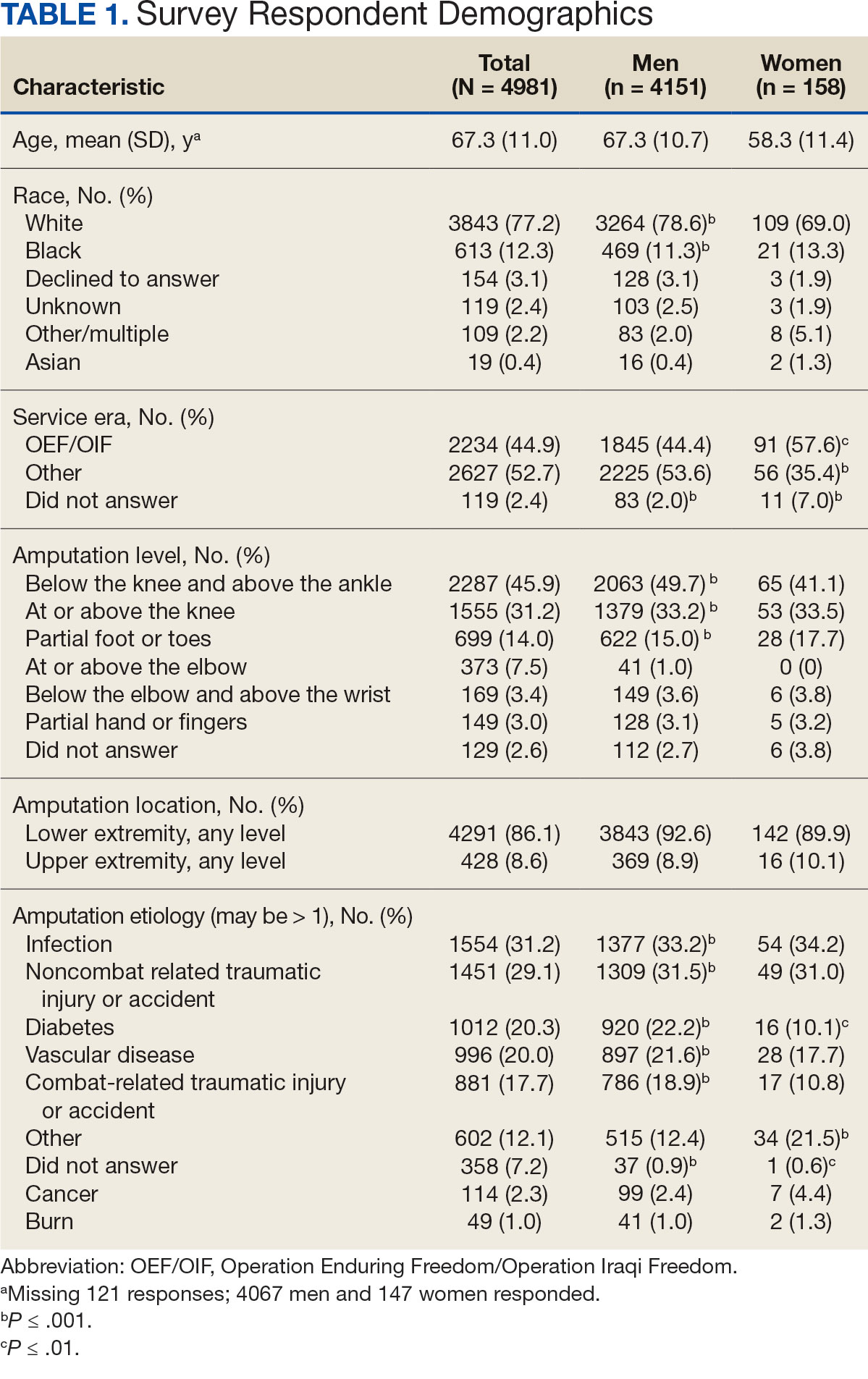

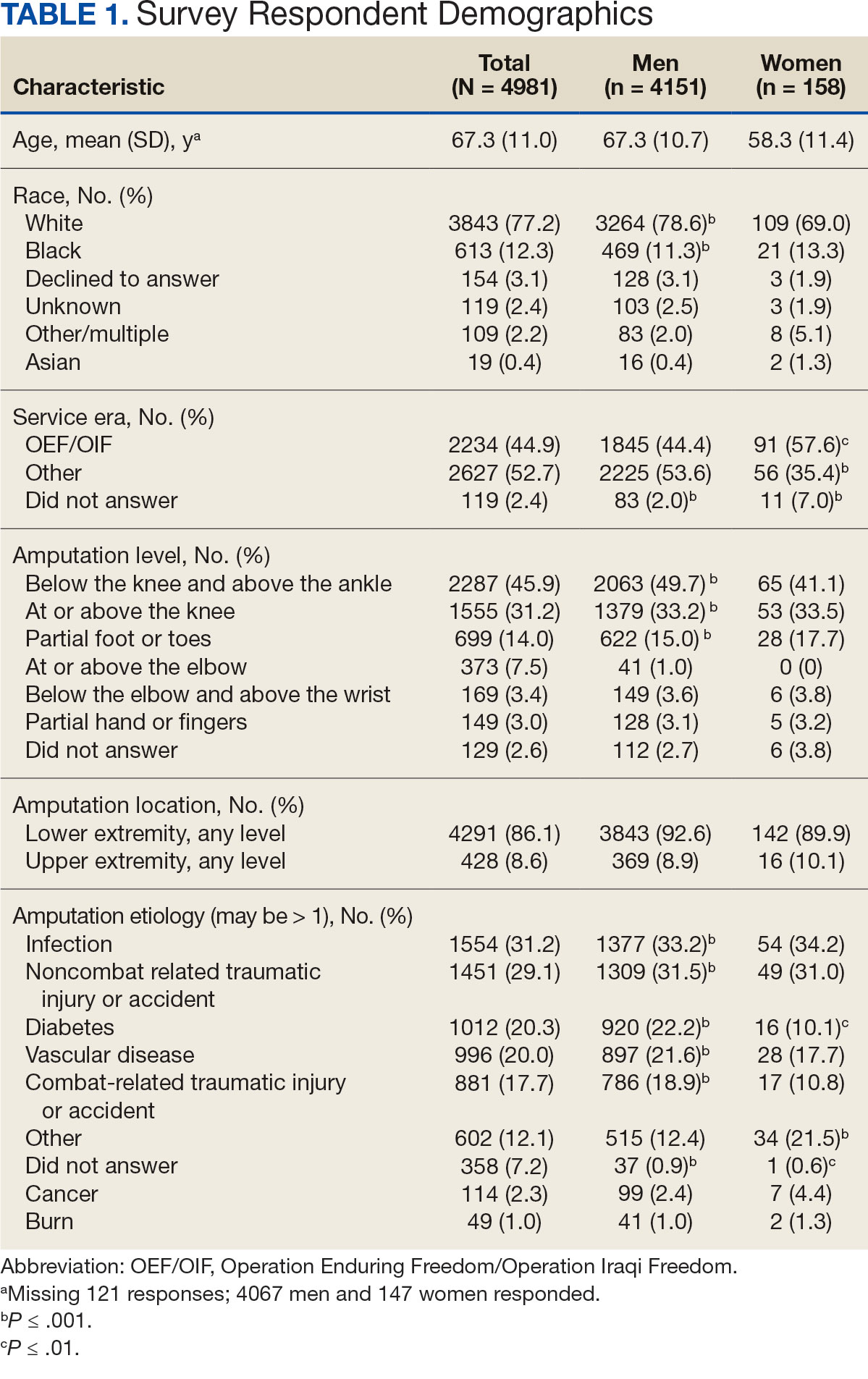

Surveys were distributed to 46,613 veterans and were completed by 4981 respondents for a 10.7% overall response rate. Survey respondents were generally similar to the eligible population invited to participate, but the proportion of women who completed the survey was higher than the proportion of women eligible to participate (2.0% of eligible population vs 16.7% of respondents), likely due to specific efforts to target women. Survey respondents were slightly younger than the general population (67.3 years vs 68.7 years), less likely to be male (97.1% vs 83.3%), showed similar representation of Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) veterans (4.4% vs 4.1%), and were less likely to have diabetes (58.0% vs 52.7% had diabetes) (Table 1).

The mean age of male respondents was 67.3 years, while the mean age of female respondents was 58.3 years. The majority of respondents were male (83.3%) and White (77.2%). Female respondents were less likely to have diabetes (35.4% of women vs 53.5% of men) and less likely to report that their most recent amputation resulted from diabetes (10.1% of women vs 22.2% of men). Women respondents were more likely to report an amputation due to other causes, such as adverse results of surgery, neurologic disease, suicide attempt, blood clots, tumors, rheumatoid arthritis, and revisions of previous amputations. Most women respondents did not serve during the OEF or OIF eras. The most common amputation site for women respondents was lower limb, either below the knee and above the ankle or above the knee.

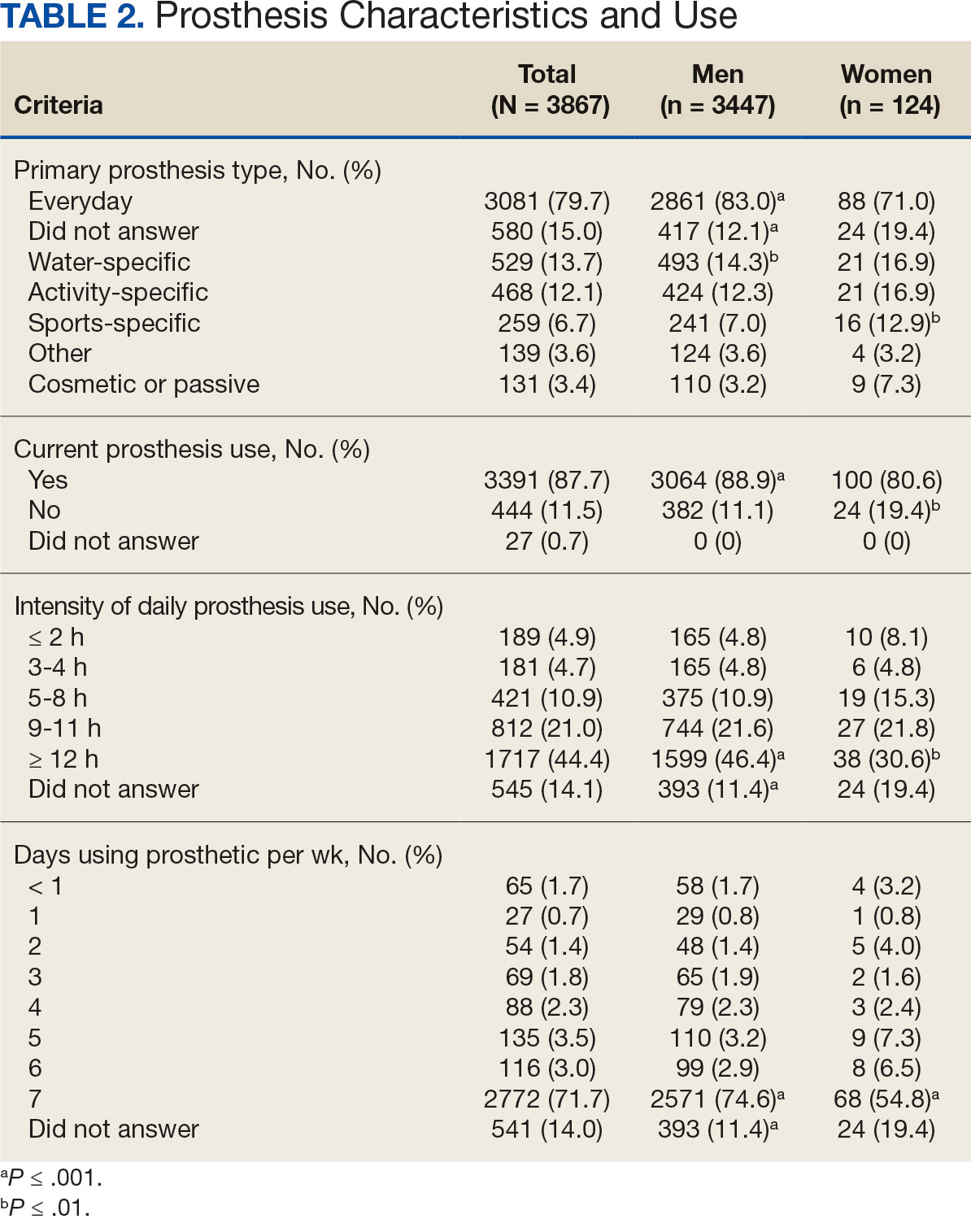

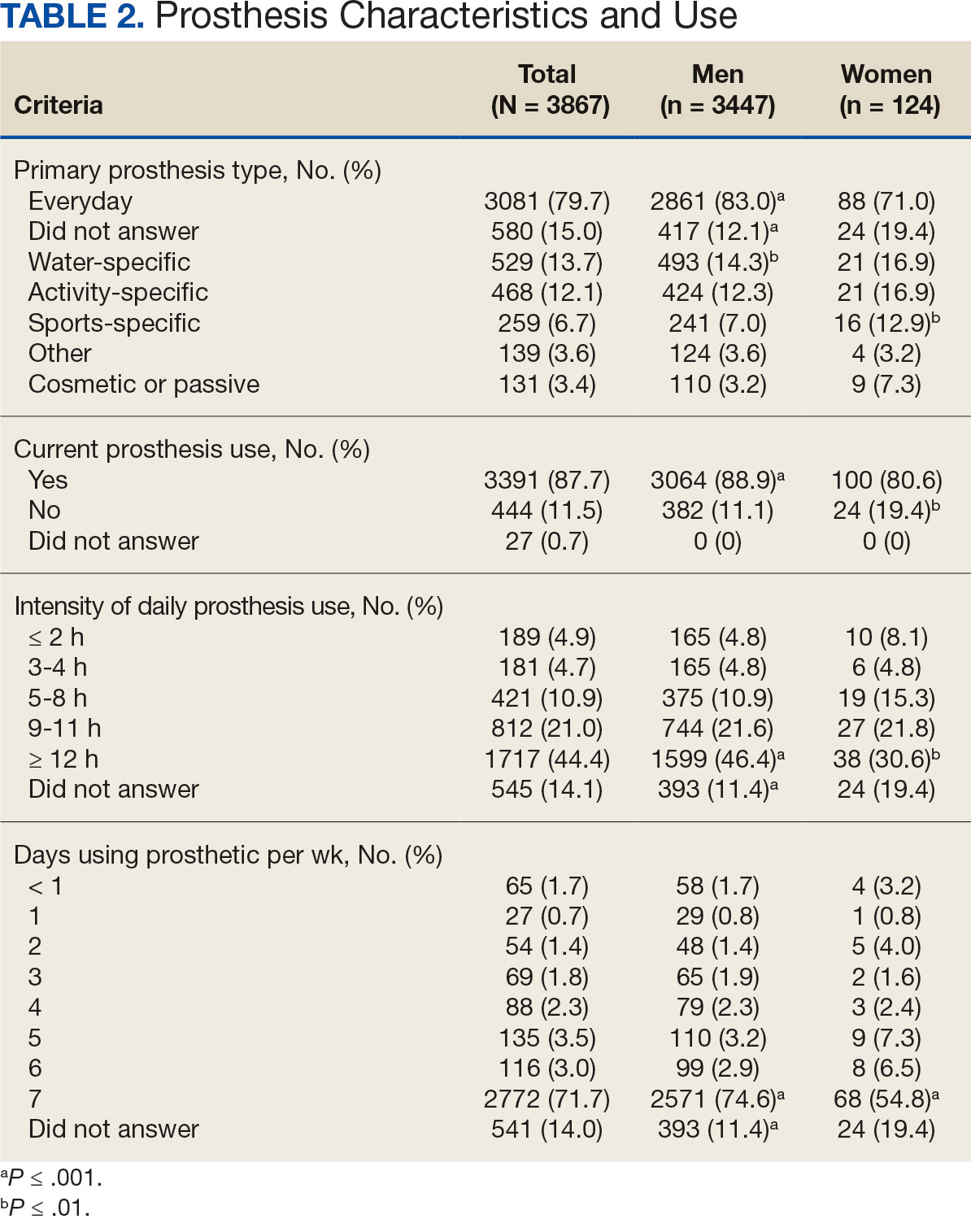

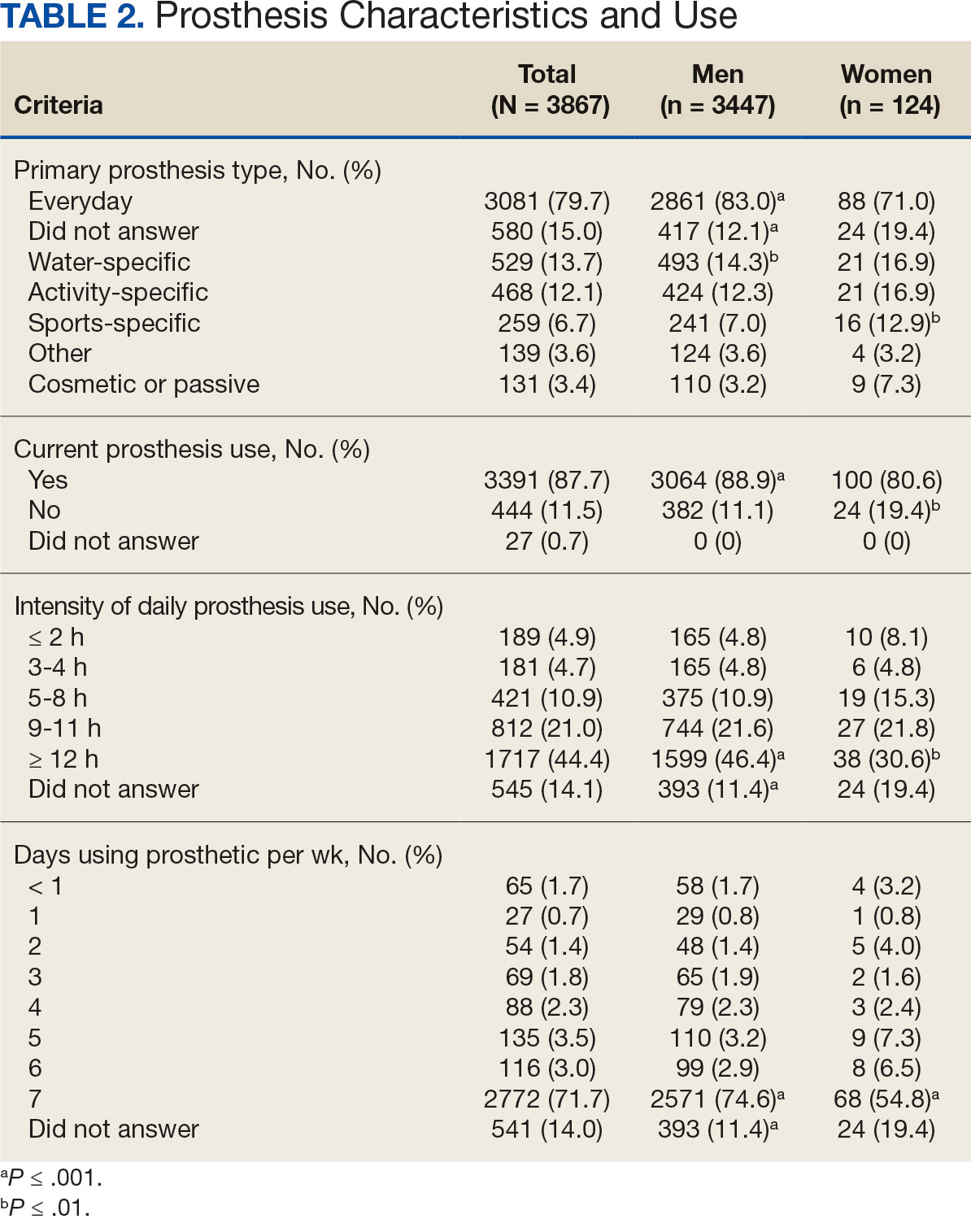

Most participants use an everyday prosthesis, but women were more likely to report using a sports-specific prosthesis (Table 2). Overall, most respondents report using a prosthesis (87.7%); however, women were more likely to report not using a prosthesis (19.4% of women vs 11.1% of men; P ≤ .01). Additionally, a lower proportion of women report using a prosthesis for < 12 hours per day (30.6% of women vs 46.4% of men; P ≤ .01) or using a prosthesis every day (54.8% of women vs 74.6% of men; P ≤ .001).

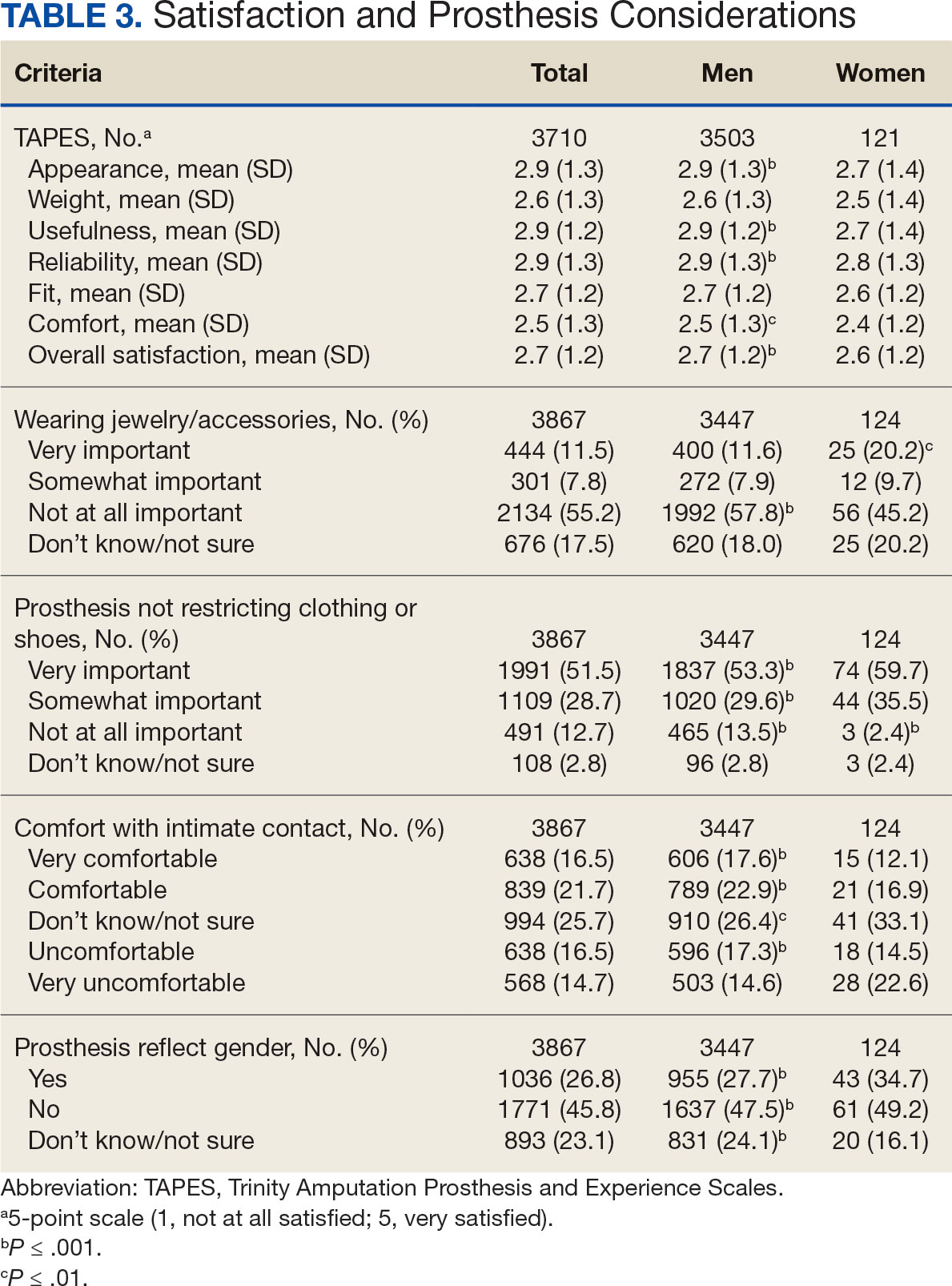

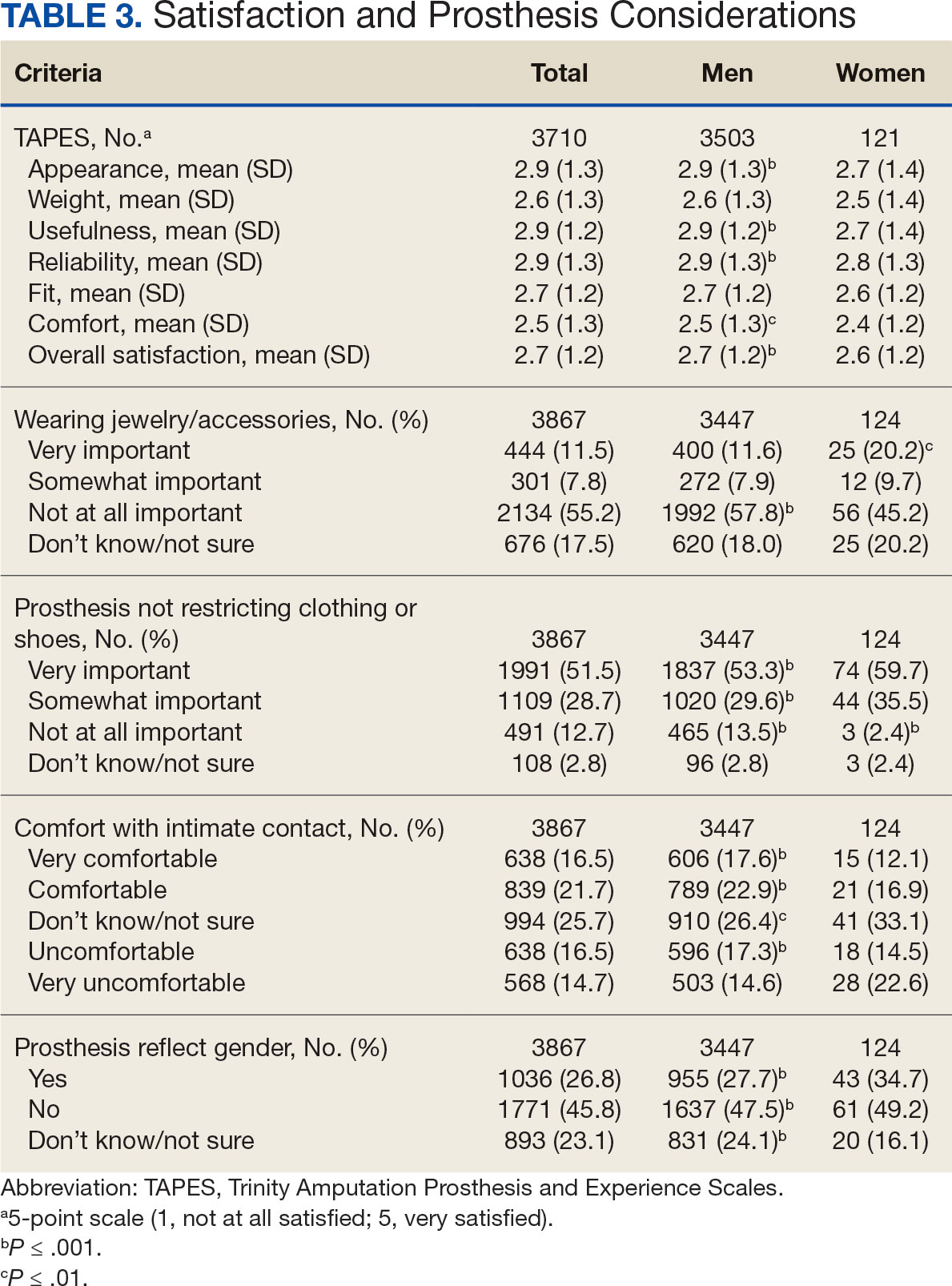

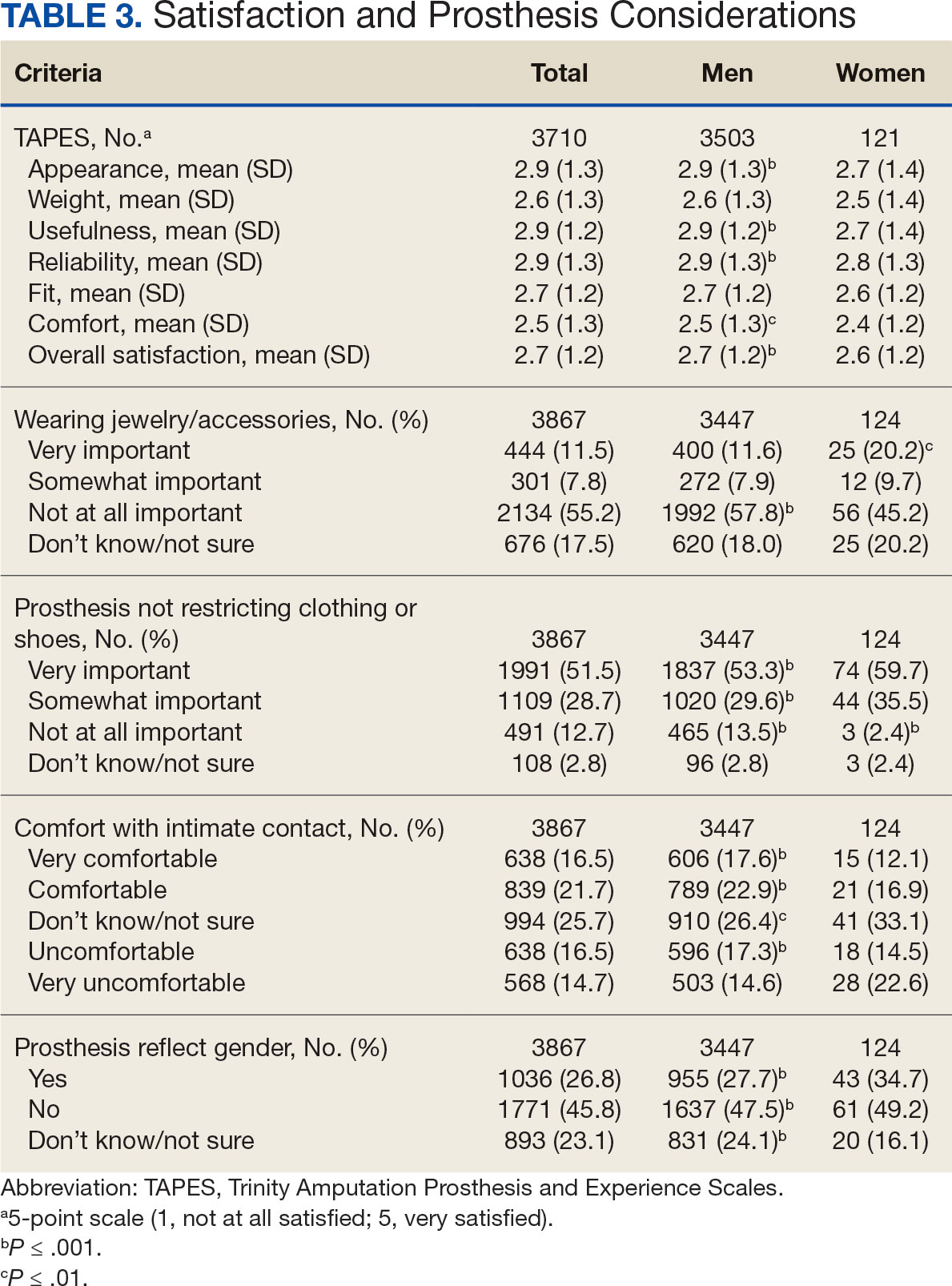

In the overall sample, the mean satisfaction score with a prosthesis was 2.7 on a 5-point scale, and women had slightly lower overall satisfaction scores (2.6 for women vs 2.7 for men; P ≤ .001) (Table 3). Women also had lower satisfaction scores related to appearance, usefulness, reliability, and comfort. Women were more likely to indicate that it was very important to be able to wear jewelry and accessories (20.2% of women vs 11.6% of men; P ≤ .01), while men were less likely to indicate that it was somewhat or very important that the prosthesis not restrict clothing or shoes (95.2% of women vs 82.9% of men; P ≤ .001). Men were more likely than women to report being comfortable or very comfortable using their prosthesis in intimate contact: 40.5% vs 29.0%, respectively (P ≤ .001).

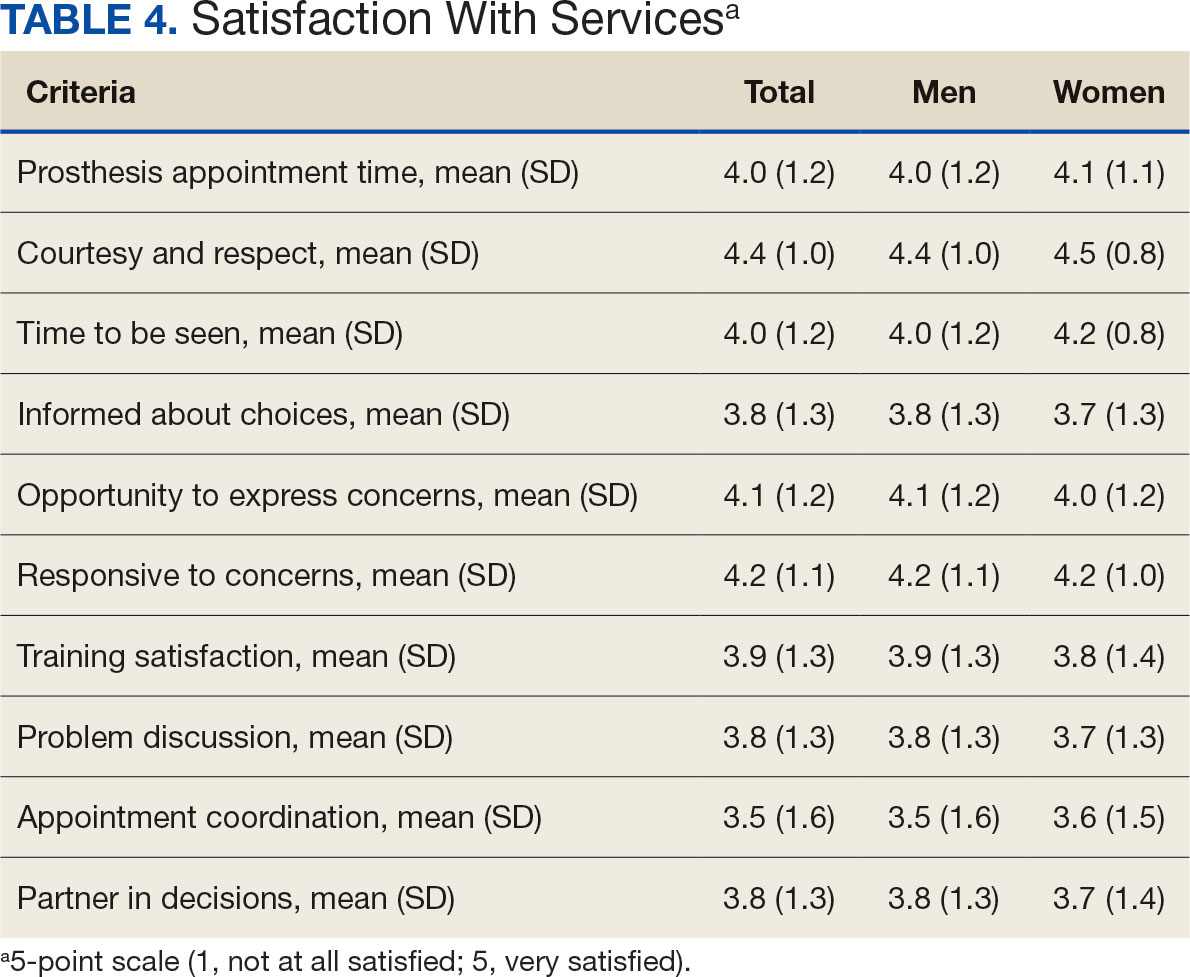

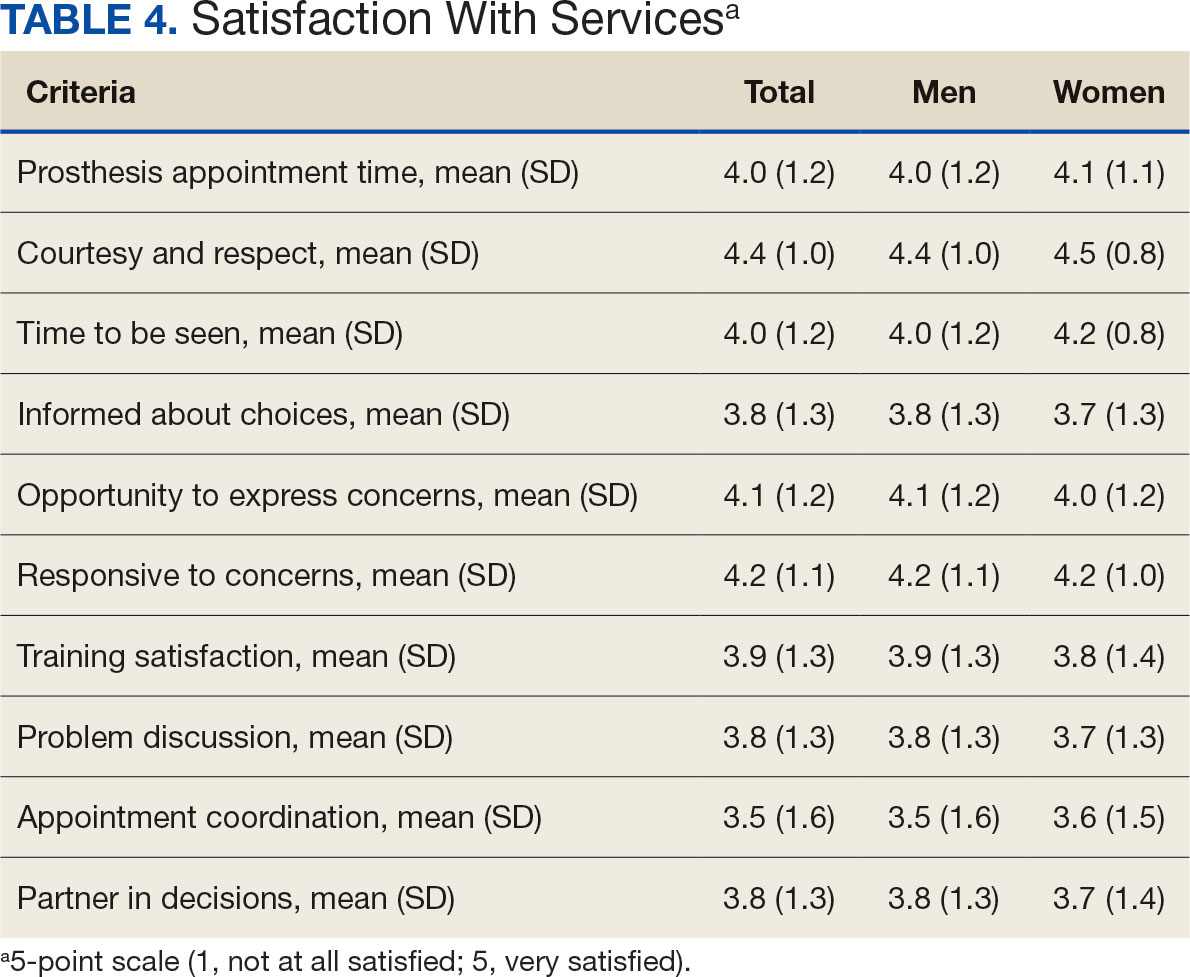

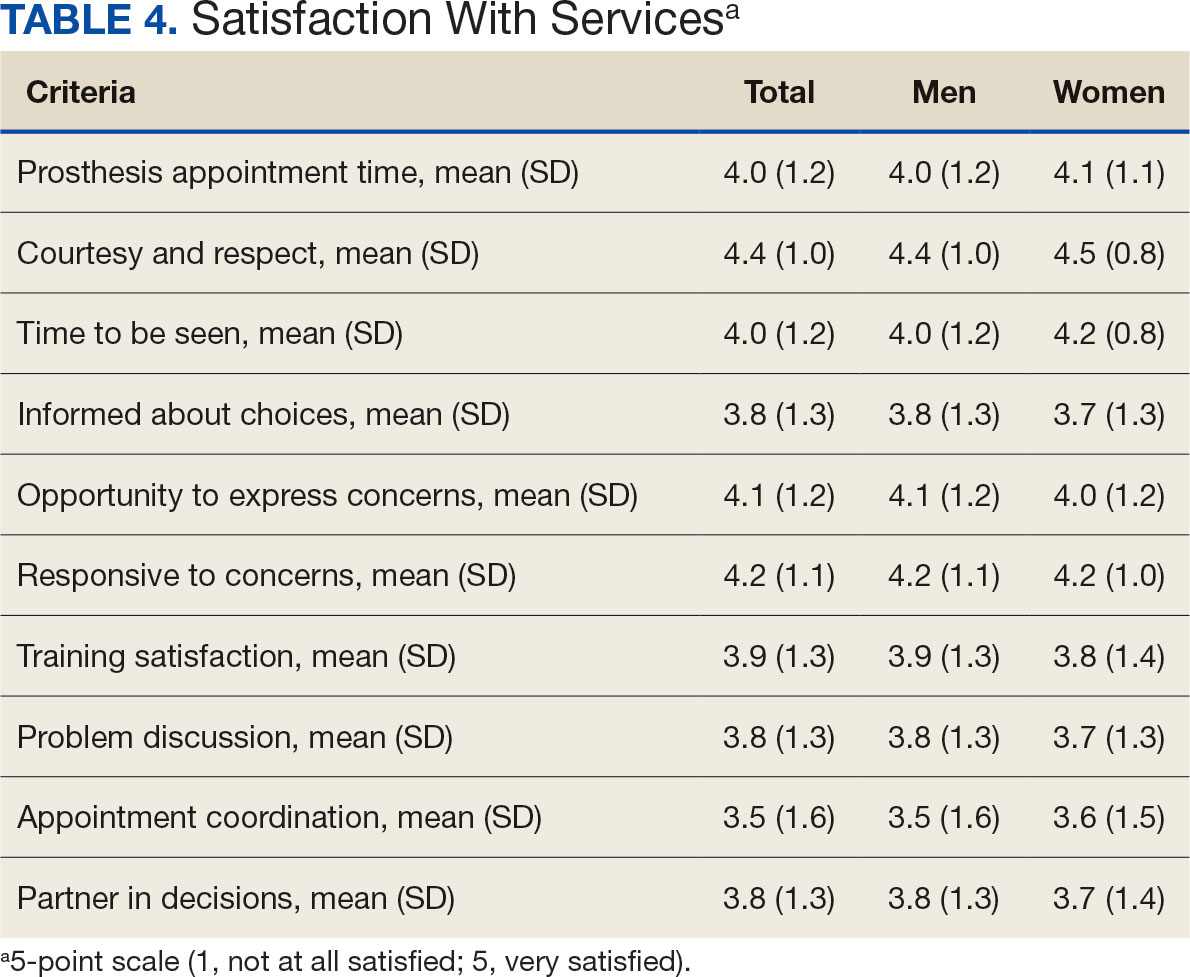

Overall, participants reported high satisfaction with appointment times, wait times, courteous treatment, opportunities to express concerns, and staff responsiveness. Men were slightly more likely than women to be satisfied with training (P ≤ 0.001) and problem discussion (P ≤ 0.01) (Table 4). There were no statistically significant differences in satisfaction or QOL ratings between women and men. The overall sample rated both QOL and satisfaction with QOL 6.7 on a 10-point scale.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to characterize the experience of veterans with limb loss receiving care in the VHA and assess their satisfaction with prostheses and prosthetic care. We received responses from nearly 5000 veterans, 158 of whom were women. Women veteran respondents were slightly younger and less likely to have an amputation due to diabetes. We did not observe significant differences in amputation level between men and women but women were less likely to use a prosthesis, reported lower intensity of prosthesis use, and were less satisfied with certain aspects of their prostheses. Women may also be less satisfied with prosthesis training and problem discussion. However, we found no differences in QOL ratings between men and women.

Findings indicating women were more likely to report not using a prosthesis and that a lower proportion of women report using a prosthesis for > 12 hours a day or every day are consistent with previous research. 21,22 Interestingly, women were more likely to report using a sports-specific prosthesis. This is notable because prior research suggests that individuals with amputations may avoid participating in sports and exercise, and a lack of access to sports-specific prostheses may inhibit physical activity.23,24 Women in this sample were slightly less satisfied with their prostheses overall and reported lower satisfaction scores regarding appearance, usefulness, reliability, and comfort, consistent with previous findings.25

A lower percentage of women in this sample reported being comfortable or very comfortable using their prosthesis during intimate contact. Previous research on prosthesis satisfaction suggests individuals who rate prosthesis satisfaction lower also report lower body image across genders. 26 While women in this sample did not rate their prosthesis satisfaction lower than men, they did report lower intensity of prosthesis use, suggesting potential issues with their prostheses this survey did not evaluate. Women indicated the importance of prostheses not restricting jewelry, accessories, clothing, or shoes. These results have significant clinical and social implications. A recent qualitative study emphasizes that women veterans feel prostheses are primarily designed for men and may not work well with their physiological needs.9 Research focused on limbs better suited to women’s bodies could result in better fitting sockets, lightweight limbs, or less bulky designs. Additional research has also explored the difficulties in accommodating a range of footwear for patients with lower limb amputation. One study found that varying footwear heights affect the function of adjustable prosthetic feet in ways that may not be optimal.27

Ratings of satisfaction with prosthesisrelated services between men and women in this sample are consistent with a recent study showing that women veterans do not have significant differences in satisfaction with prosthesis-related services.28 However, this study focused specifically on lower limb amputations, while the respondents of this study include those with both upper and lower limb amputations. Importantly, our findings that women are less likely to be satisfied with prosthesis training and problem discussions support recent qualitative findings in which women expressed a desire to work with prosthetists who listen to them, take their concerns seriously, and seek solutions that fit their needs. We did not observe a difference in QOL ratings between men and women in the sample despite lower satisfaction among women with some elements of prosthesis-related services. Previous research suggests many factors impact QOL after amputation, most notably time since amputation.16,29

Limitations

This survey was deployed in a short timeline that did not allow for careful sample selection or implementing strategies to increase response rate. Additionally, the study was conducted among veterans receiving care in the VHA, and findings may not be generalizable to limb loss in other settings. Finally, the discrepancy in number of respondents who identified as men vs women made it difficult to compare differences between the 2 groups.

Conclusions

This is the largest sample of survey respondents of veterans with limb loss to date. While the findings suggest veterans are generally satisfied with prosthetic-related services overall, they also highlight several areas for improvement with services or prostheses. Given that most veterans with limb loss are men, there is a significant discrepancy between the number of women and men respondents. Additional studies with more comparable numbers of men and women have found similar ratings of satisfaction with prostheses and services.28 Further research specifically focused on improving the experiences of women should focus on better characterizing their experiences and identifying how they differ from those of male veterans. For example, understanding how to engage female veterans with limb loss in prosthesis training and problem discussions may improve their experience with their care teams and improve their use of prostheses. Understanding experiences and needs that are specific to women could lead to the development of processes, resources, or devices that are tailored to the unique requirements of women with limb loss.

- Ziegler-Graham K, MacKenzie EJ, Ephraim PL, Travison TG, Brookmeyer R. Estimating the prevalence of limb loss in the United States: 2005 to 2050. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(3):422-429. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2007.11.005

- Dillingham TR, Pezzin LE, MacKenzie EJ. Limb amputation and limb deficiency: epidemiology and recent trends in the united states. South Med J. 2002;95(8):875-883. doi:10.1097/00007611-200208000-00018

- Dillingham TR, Pezzin LE, Shore AD. Reamputation, mortality, and health care costs among persons with dysvascular lower-limb amputations. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(3):480-486. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2004.06.072

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ambulatory and inpatient procedures in the United States. Accessed September 30, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/98facts/ambulat.htm

- Ljung J, Iacangelo A. Identifying and acknowledging a sex gap in lower-limb prosthetics. JPO. 2024;36(1):e18-e24. doi:10.1097/JPO.0000000000000470

- Feinglass J, Brown JL, LoSasso A, et al. Rates of lower-extremity amputation and arterial reconstruction in the united states, 1979 to 1996. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(8):1222- 1227. doi:10.2105/ajph.89.8.1222

- Mayfield JA, Reiber GE, Maynard C, Czerniecki JM, Caps MT, Sangeorzan BJ. Trends in lower limb amputation in the Veterans Health Administration, 1989-1998. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2000;37(1):23-30.

- Feinglass J, Pearce WH, Martin GJ, et al. Postoperative and late survival outcomes after major amputation: findings from the department of veterans affairs national surgical quality improvement program. Surgery. 2001;130(1):21-29. doi:10.1067/msy.2001.115359

- Lehavot K, Young JP, Thomas RM, et al. Voices of women veterans with lower limb prostheses: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(3):799-805. doi:10.1007/s11606-022-07572-8

- US Government Accountability Office. COVID-19: Opportunities to improve federal response. GAO-21-60. Published November 12, 2020. Accessed September 30, 2024. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-60

- Littman AJ, Peterson AC, Korpak A, et al. Differences in prosthetic prescription between men and women veterans after transtibial or transfemoral lowerextremity amputation: a longitudinal cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2023;104(8)1274-1281. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2023.02.011

- Cimino SR, Vijayakumar A, MacKay C, Mayo AL, Hitzig SL, Guilcher SJT. Sex and gender differences in quality of life and related domains for individuals with adult acquired lower-limb amputation: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. 2022 Oct 23;44(22):6899-6925. doi:10.1080/09638288.2021.1974106

- DadeMatthews OO, Roper JA, Vazquez A, Shannon DM, Sefton JM. Prosthetic device and service satisfaction, quality of life, and functional performance in lower limb prosthesis clients. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2024;48(4):422-430. doi:10.1097/PXR.0000000000000285

- Hamilton AB, Schwarz EB, Thomas HN, Goldstein KM. Moving women veterans’ health research forward: a special supplement. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(Suppl3):665– 667. doi:10.1007/s11606-022-07606-1

- US Congress. Public Law 116-315: An Act to Improve the Lives of Veterans, S 5108 (2) (F). 116th Congress; 2021. Accessed September 30, 2024. https://www.congress.gov/116/plaws/publ315/PLAW-116publ315.pdf

- Gallagher P, MacLachlan M. The Trinity amputation and prosthesis experience scales and quality of life in people with lower-limb amputation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(5):730-736. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2003.07.009

- Legro MW, Reiber GD, Smith DG, del Aguila M, Larsen J, Boone D. Prosthesis evaluation questionnaire for persons with lower limb amputations: assessing prosthesis-related quality of life. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79(8):931-938. doi:10.1016/s0003-9993(98)90090-9

- Legro MW, Reiber GD, Smith DG, del Aguila M, Larsen J, Boone D. Prosthesis evaluation questionnaire for persons with lower limb amputations: assessing prosthesis-related quality of life. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79(8):931-938. doi:10.1016/s0003-9993(98)90090-9

- Heinemann AW, Bode RK, O’Reilly C. Development and measurement properties of the orthotics and prosthetics users’ survey (OPUS): a comprehensive set of clinical outcome instruments. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2003;27(3):191-206. doi:10.1080/03093640308726682

- Resnik LJ, Borgia ML, Clark MA. A national survey of prosthesis use in veterans with major upper limb amputation: comparisons by gender. PM R. 2020;12(11):1086-1098. doi:10.1002/pmrj.12351

- Collins D. Pretesting survey instruments: an overview of cognitive methods. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(3):229-238. doi:10.1023/a:1023254226592

- Østlie K, Lesjø IM, Franklin RJ, Garfelt B, Skjeldal OH, Magnus P. Prosthesis rejection in acquired major upper-limb amputees: a population-based survey. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2012;7(4):294-303. doi:10.3109/17483107.2011.635405

- Pezzin LE, Dillingham TR, MacKenzie EJ, Ephraim P, Rossbach P. Use and satisfaction with prosthetic limb devices and related services. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(5):723-729. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2003.06.002

- Deans S, Burns D, McGarry A, Murray K, Mutrie N. Motivations and barriers to prosthesis users participation in physical activity, exercise and sport: a review of the literature. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2012;36(3):260-269. doi:10.1177/0309364612437905

- McDonald CL, Kahn A, Hafner BJ, Morgan SJ. Prevalence of secondary prosthesis use in lower limb prosthesis users. Disabil Rehabil. 2023;46(5):1016-1022. doi:10.1080/09638288.2023.2182919

- Baars EC, Schrier E, Dijkstra PU, Geertzen JHB. Prosthesis satisfaction in lower limb amputees: a systematic review of associated factors and questionnaires. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(39):e12296. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000012296

- Murray CD, Fox J. Body image and prosthesis satisfaction in the lower limb amputee. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24(17):925–931. doi:10.1080/09638280210150014

- Major MJ, Quinlan J, Hansen AH, Esposito ER. Effects of women’s footwear on the mechanical function of heel-height accommodating prosthetic feet. PLoS One. 2022;17(1). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0262910.

- Kuo PB, Lehavot K, Thomas RM, et al. Gender differences in prosthesis-related outcomes among veterans: results of a national survey of U.S. veterans. PM R. 2024;16(3):239- 249. doi:10.1002/pmrj.13028

- Asano M, Rushton P, Miller WC, Deathe BA. Predictors of quality of life among individuals who have a lower limb amputation. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2008;32(2):231-243. doi:10.1080/03093640802024955

Limb loss is a significant and growing concern in the United States. Nearly 2 million Americans are living with limb loss, and up to 185,000 people undergo amputations annually.1-4 Of these patients, about 35% are women.5 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) provides about 10% of US amputations.6-8 Between 2015 and 2019, the number of prosthetic devices provided to female veterans increased from 3.3 million to 4.6 million.5,9,10

Previous research identified disparities in prosthetic care between men and women, both within and outside the VHA. These disparities include slower prosthesis prescription and receipt among women, in addition to differences in self-reported mobility, satisfaction, rates of prosthesis rejection, and challenges related to prosthesis appearance and fit.5,10,11 Recent studies suggest women tend to have worse outcomes following amputation, and are underrepresented in amputation research.12,13 However, these disparities are poorly described in a large, national sample. Because women represent a growing portion of patients with limb loss in the VHA, understanding their needs is critical.14

The Johnny Isakson and David P. Roe, MD Veterans Health Care and Benefits Improvement Act of 2020 was enacted, in part, to improve the care provided to women veterans.15 The law required the VHA to conduct a survey of ≥ 50,000 veterans to assess the satisfaction of women veterans with prostheses provided by the VHA. To comply with this legislation and understand how women veterans rate their prostheses and related care in the VHA, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Center for Collaborative Evaluation (VACE) conducted a large national survey of veterans with limb loss that oversampled women veterans. This article describes the survey results, including characteristics of female veterans with limb loss receiving care from the VHA, assesses their satisfaction with prostheses and prosthetic care, and highlights where their responses differ from those of male veterans.

Methods