User login

Primary Care Clinician and Patient Knowledge, Interest, and Use of Integrative Treatment Options for Chronic Low Back Pain Management

Primary Care Clinician and Patient Knowledge, Interest, and Use of Integrative Treatment Options for Chronic Low Back Pain Management

More than 50 million US adults report experiencing chronic pain, with nearly 7% experiencing high-impact chronic pain.1-3 Chronic pain negatively affects daily function, results in lost productivity, is a leading cause of disability, and is more prevalent among veterans compared with the general population.1,2,4-6 Estimates from 2021 suggest the prevalence of chronic pain among veterans exceeds 30%; > 11% experienced high-impact chronic pain.1

Primary care practitioners (PCPs) have a prominent role in chronic pain management. Pharmacologic options for treating pain, once a mainstay of therapy, present several challenges for patients and PCPs, including drug-drug interactions and adverse effects.7 The US opioid epidemic and shift to a biopsychosocial model of chronic pain care have increased emphasis on nonpharmacologic treatment options.8,9 These include integrative modalities, which incorporate conventional approaches with an array of complementary health approaches.10-12

Integrative therapy is a prominent feature in whole person care, which may be best exemplified by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Whole Health System of care.13-14 Whole health empowers an individual to take charge of their health and well-being so they can “live their life to the fullest.”14 As implemented in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), whole health includes the use of evidence-based

METHODS

Using a cross-sectional survey design, PCPs and patients with chronic back pain affiliated with the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System were invited to participate in separate but similar surveys to assess knowledge, interest, and use of nonpharmacologic integrative modalities for the treatment of chronic pain. In May, June, and July 2023, 78 PCPs received 3 email

Both survey instruments are available upon request, were developed by the study team, and included a mix of yes/no questions, “select all that apply” items, Likert scale response items, and open-ended questions. For one question about which modalities they would like available, the respondent was instructed to select up to 5 modalities. The instruments were extensively pretested by members of the study team, which included 2 PCPs and a nonveteran with chronic back pain.

The list of integrative modalities included in the survey was derived from the tier 1 and tier 2 complementary and integrative health modalities identified in a VHA Directive on complementary and integrative health.15,16 Tier 1 approaches are considered to have sufficient evidence and must be made available to veterans either within a VA medical facility or in the community. Tier 2 approaches are generally considered safe and may be made available but do not have sufficient evidence to mandate their provision. For participant ease, the integrative modalities were divided into 5 subgroups: manual therapies, energy/biofield therapies, mental health therapies, nutrition counseling, and movement therapies. The clinician survey assessed clinicians’ training and interest, clinical and personal use, and perceived barriers to providing integrative modalities for chronic pain. Professional and personal demographic data were also collected. Similarly, the patient survey assessed use of integrative therapies, perceptions of and interest in integrative modalities, and potential barriers to use. Demographic and health-related information was also collected.

Data analysis included descriptive statistics (eg, frequency counts, means, medians) and visual graphic displays. Separate analyses were conducted for clinicians and patients in addition to a comparative analysis of the use and potential interest in integrative modalities. Analysis were conducted using R software. This study was deemed nonresearch quality improvement by the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System facility research oversight board and institutional review board approval was not solicited.

RESULTS

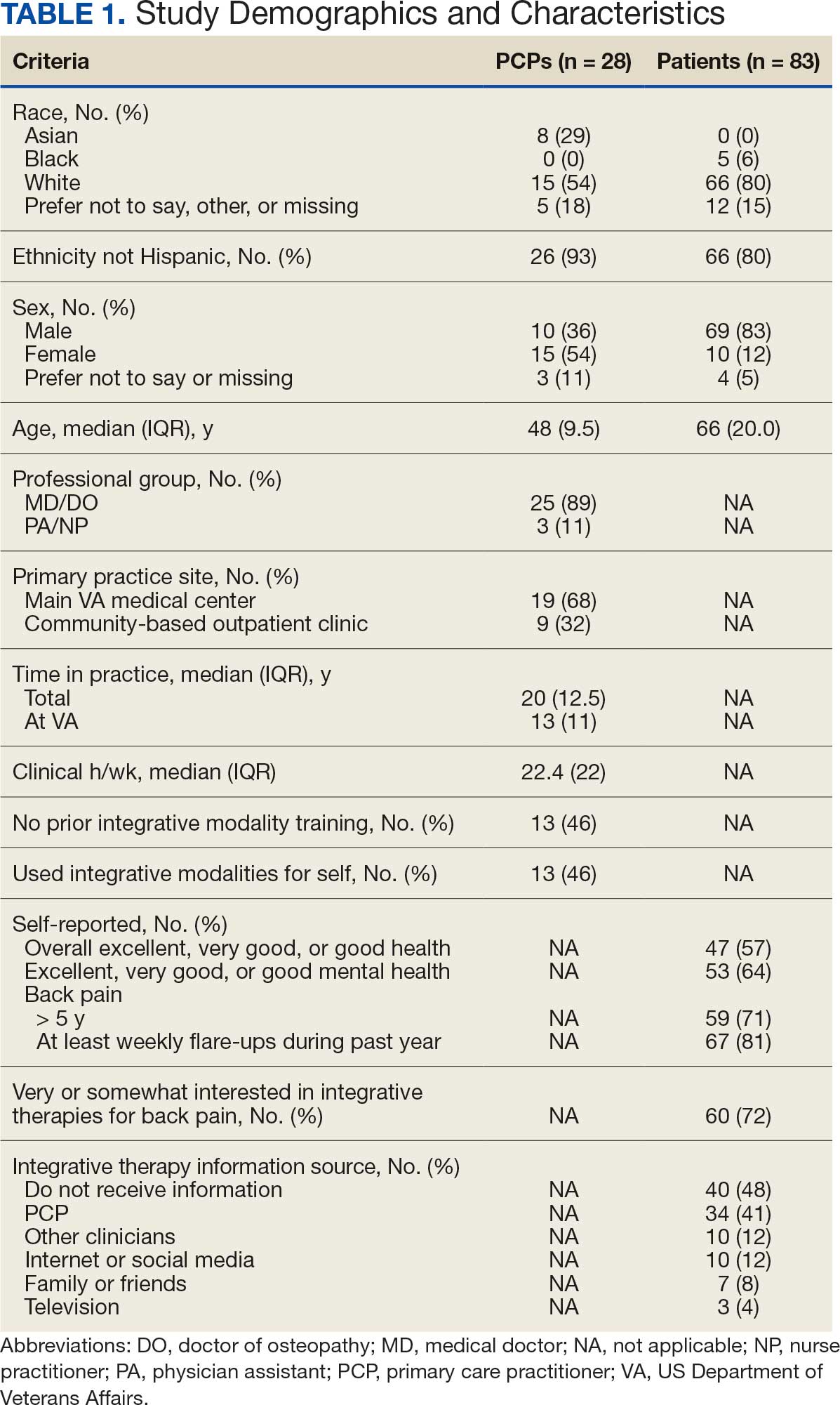

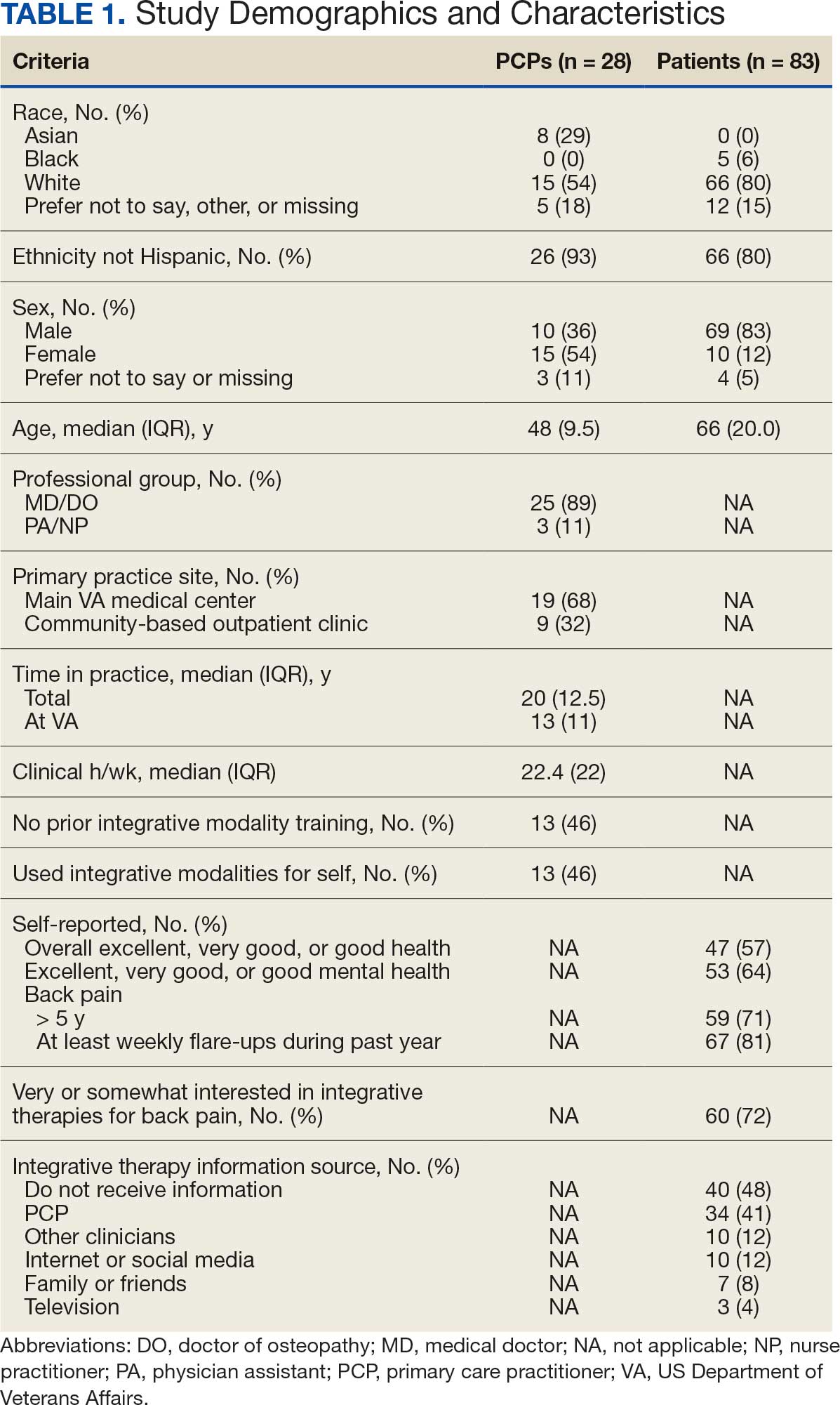

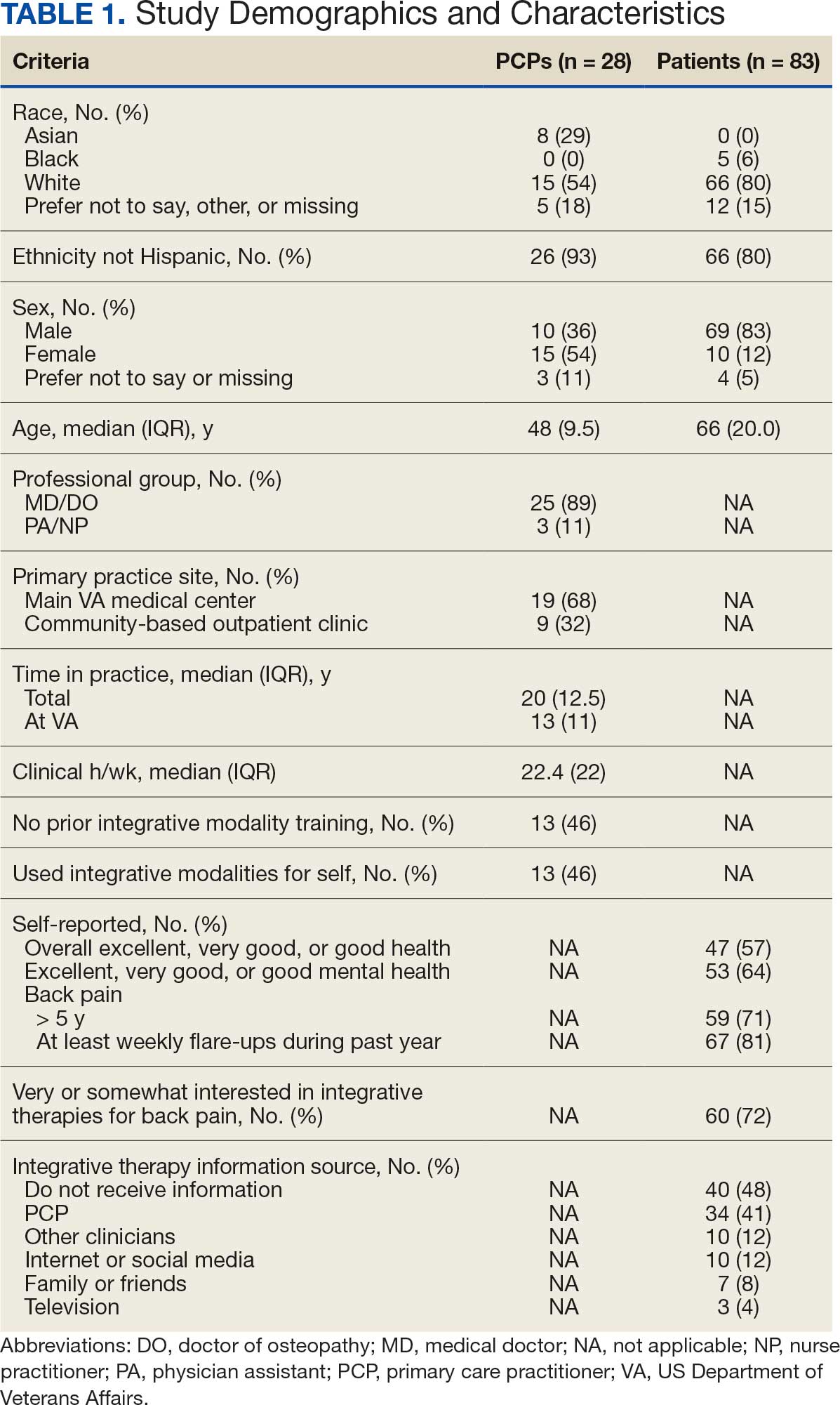

Twenty-eight clinicians completed the survey, yielding a participation rate of 36%. Participating clinicians had a median (IQR) age of 48 years (9.5), 15 self-identified as White (54%), 8 as Asian (29%), 15 as female (54%), 26 as non-Hispanic (93%), and 25 were medical doctors or doctors of osteopathy (89%). Nineteen (68%) worked at the main hospital outpatient clinic, and 9 practiced at community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). Thirteen respondents (46%) reported having no formal education or training in integrative approaches. Among those with prior training, 8 clinicians had nutrition counseling (29%) and 7 had psychologic therapy training (25%). Thirteen respondents (46%) also reported using integrative modalities for personal health needs: 8 used psychological therapies, 8 used movement therapies, 10 used integrative modalities for stress management or relaxation, and 8 used them for physical symptoms (Table 1).

Overall, 85 of 200 patients (43%) responded to the study survey. Two patients indicated they did not have chronic back pain and were excluded. Patients had a median (IQR) age of 66 (20) years, with 66 self-identifying as White (80%), 69 as male (83%), and 66 as non-Hispanic (80%). Forty-four patients (53%) received care at CBOCs. Forty-seven patients reported excellent, very good, or good overall health (57%), while 53 reported excellent, very good, or good mental health (64%). Fifty-nine patients reported back pain duration > 5 years (71%), and 67 (81%) indicated experiencing back pain flare-ups at least once per week over the previous 12 months. Sixty patients (72%) indicated they were somewhat or very interested in using integrative therapies as a back pain treatment; however, 40 patients (48%) indicated they had not received information about these therapies. Among those who indicated they had received information, the most frequently reported source was their PCP (41%). Most patients (72%) also reported feeling somewhat to very comfortable discussing integrative medicine therapies with their PCP.

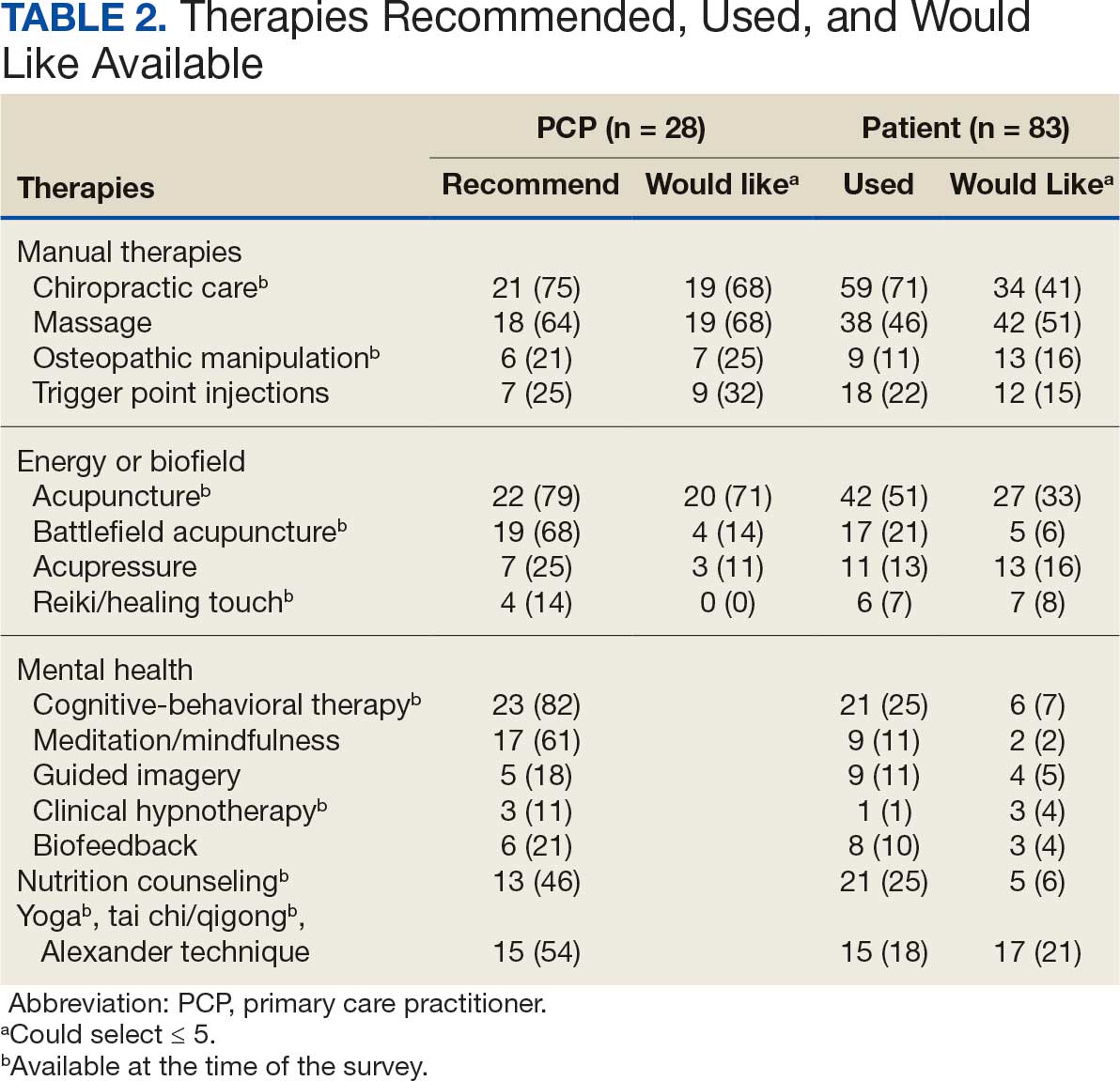

Integrative Therapy Recommendations and Use

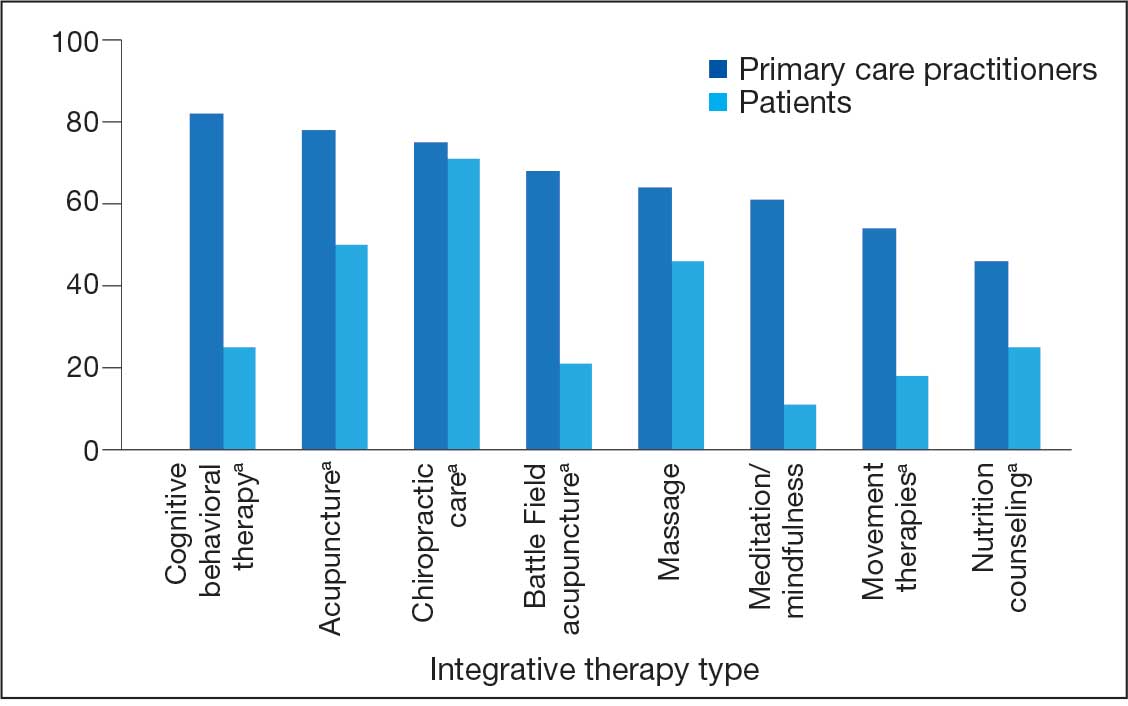

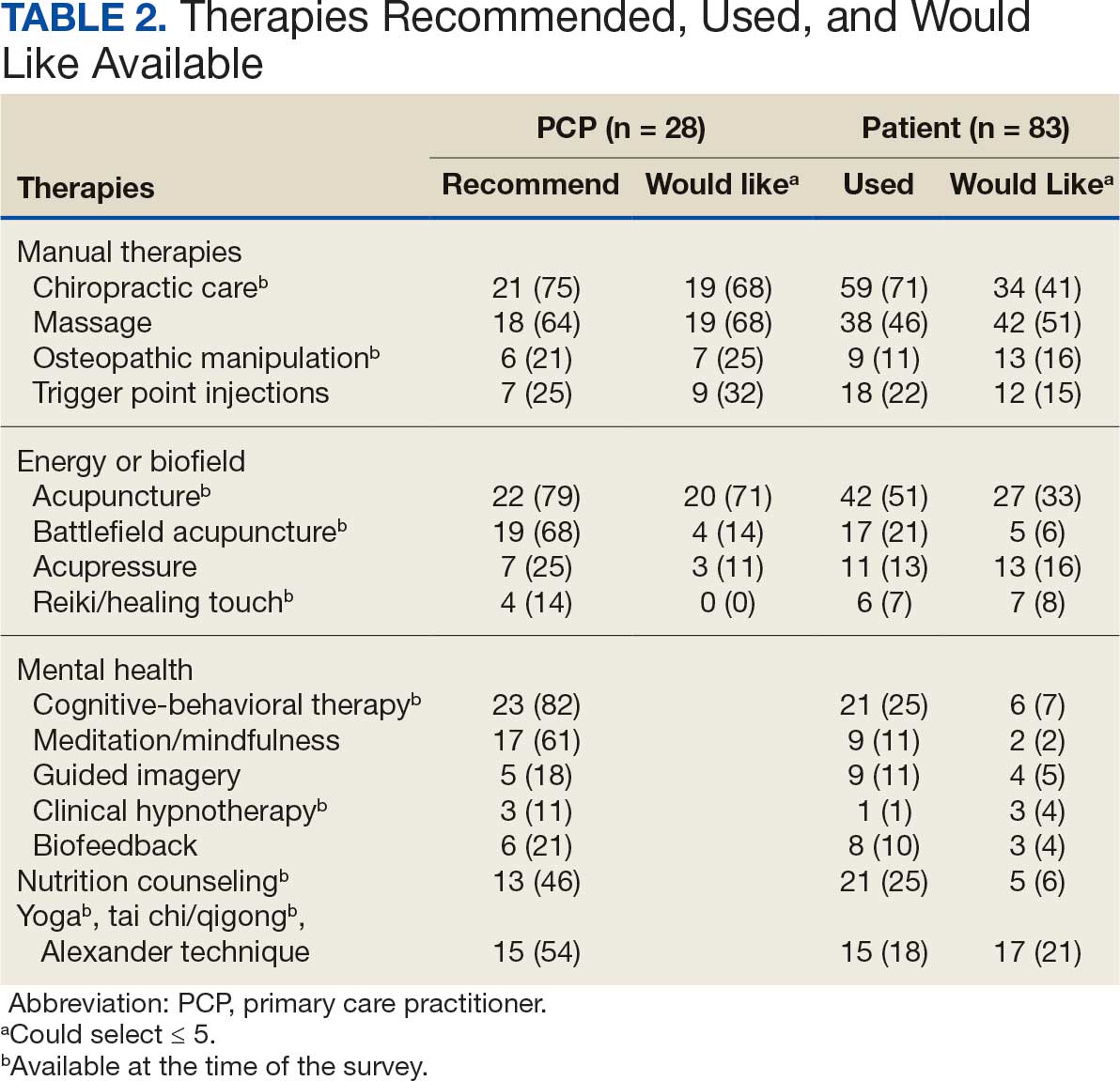

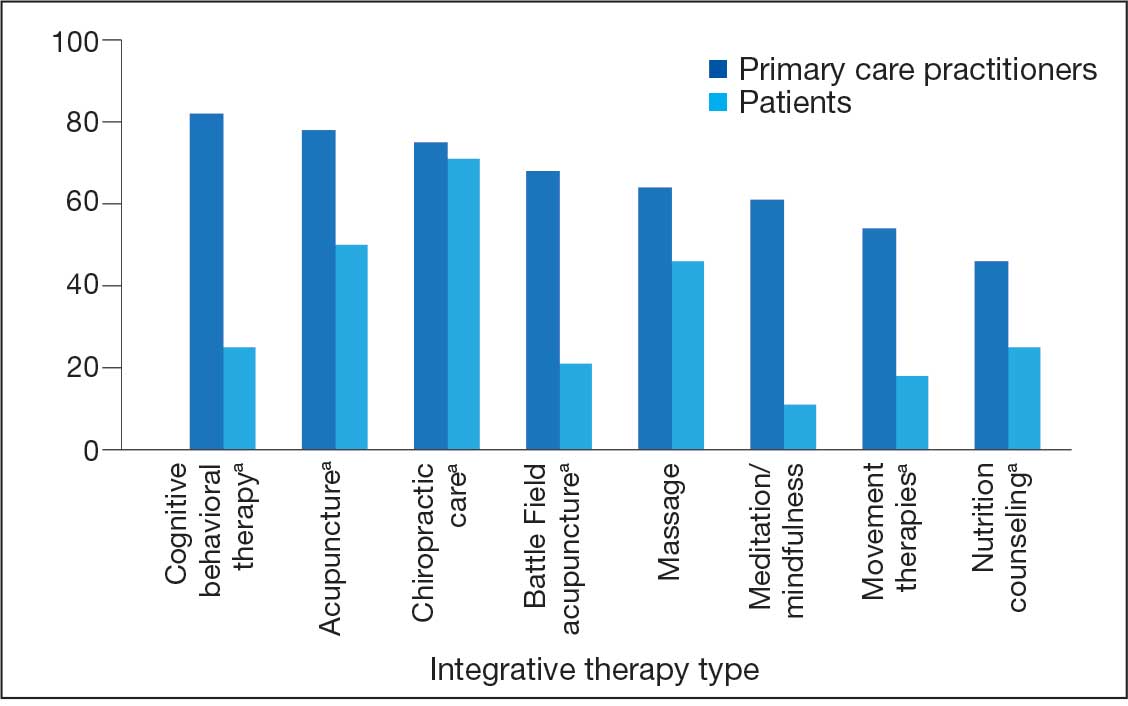

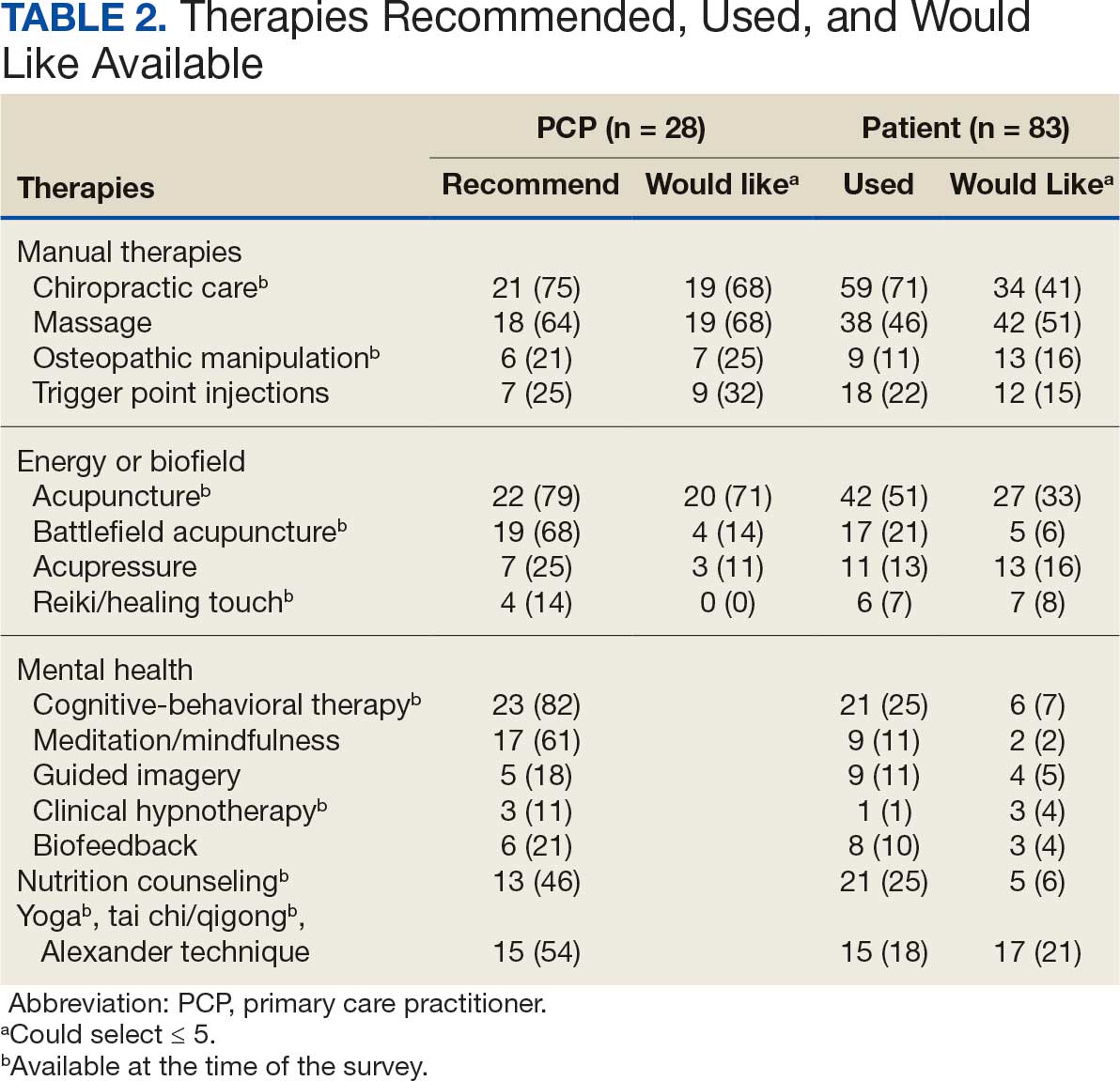

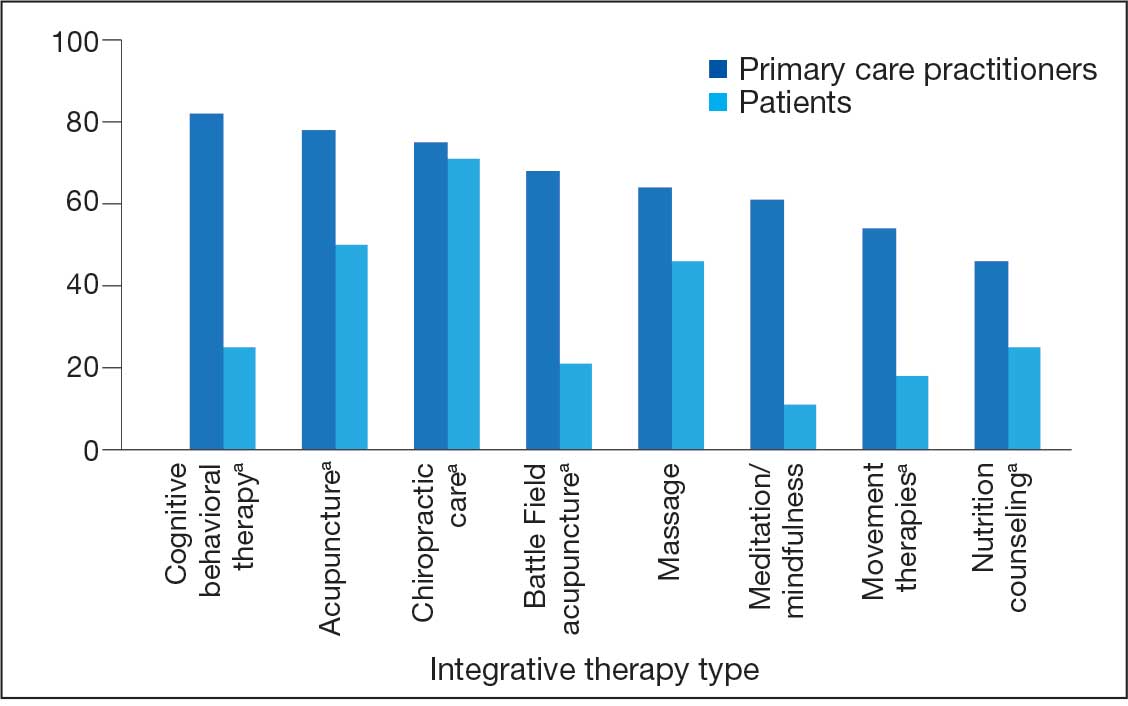

PCPs reported recommending multiple integrative modalities: 23 (82%) recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy, 22 (79%) recommended acupuncture, 21 (75%) recommended chiropractic, 19 (68%) recommended battlefield acupuncture, recommended massage 18 (64%), 17 (61%) recommended meditation or mindfulness, and 15 (54%) recommended movement therapies such as yoga or tai chi/qigong (Figure 1). The only therapies used by at least half of the patients were chiropractic used by 59 patients (71%) and acupuncture by 42 patients (51%). Thirty-eight patients (46%) reported massage use and 21 patients (25%) used cognitive-behavioral therapy (Table 2).

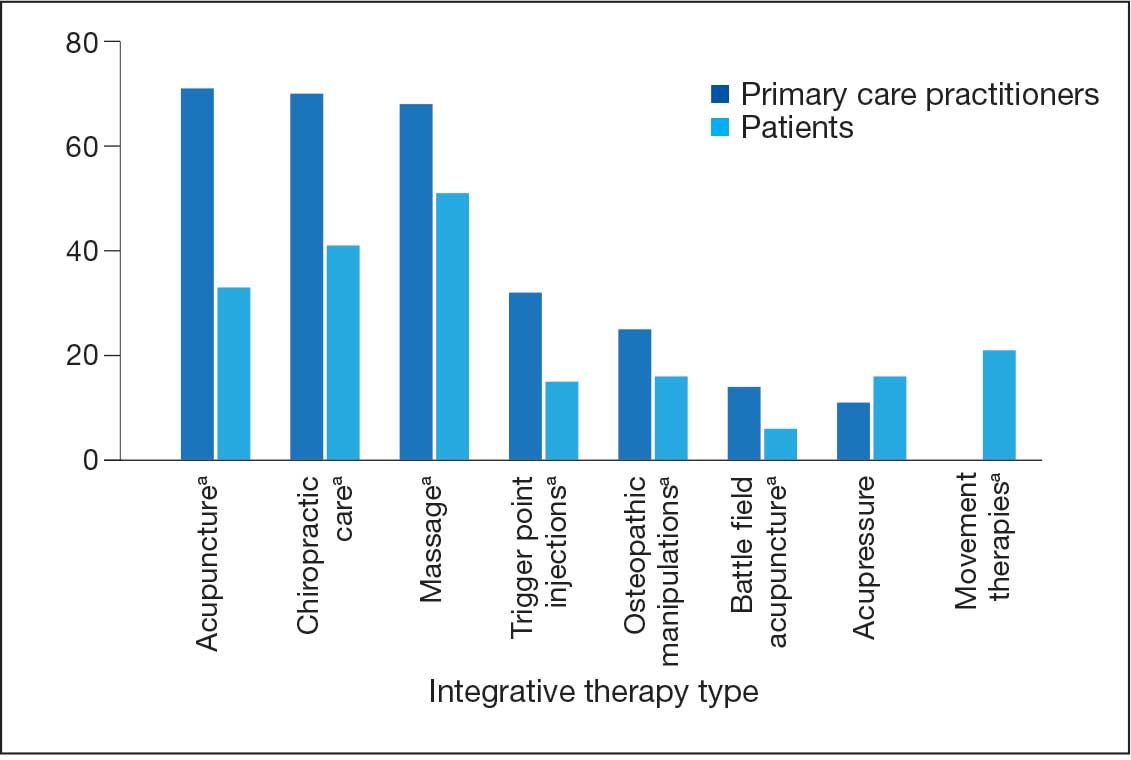

Integrative Therapies Desired

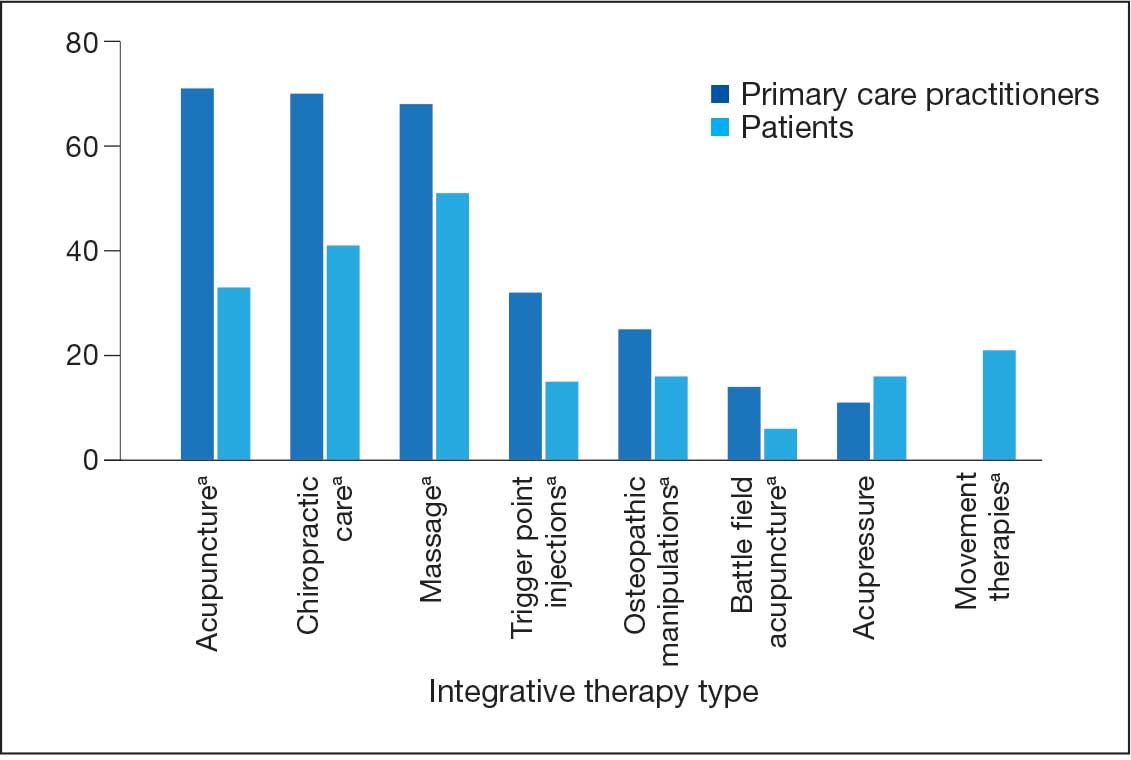

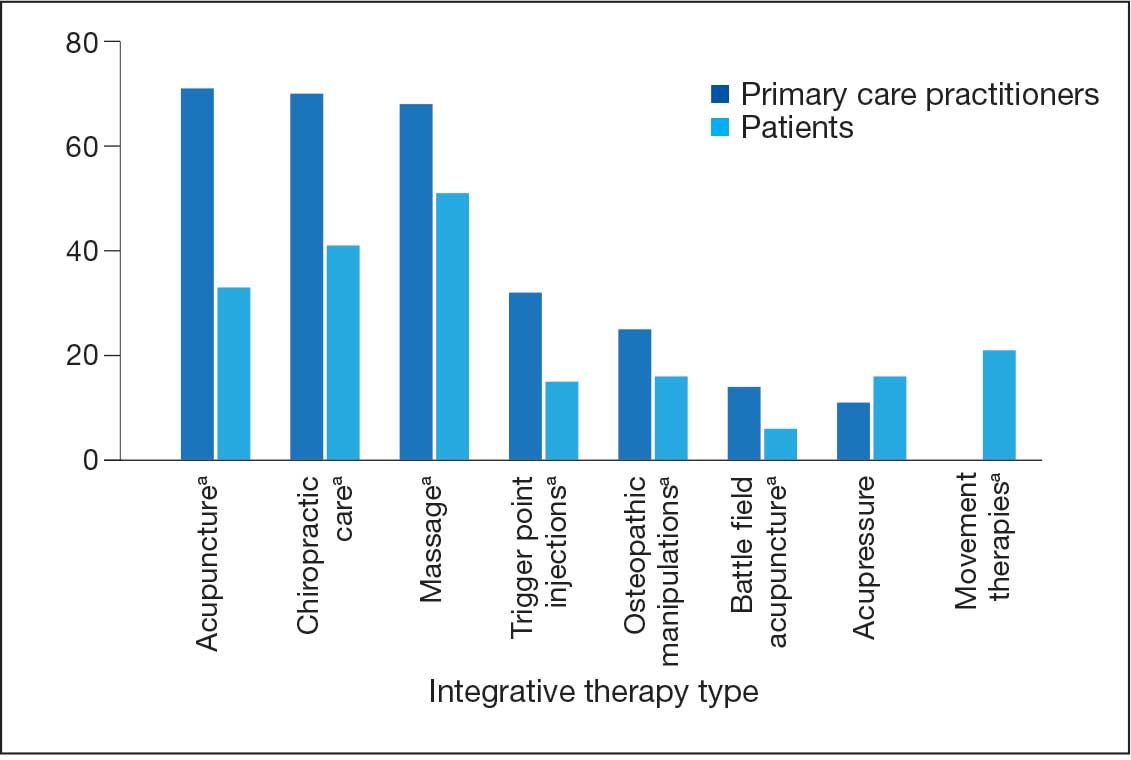

A majority of PCPs identified acupuncture (n = 20, 71%), chiropractic (n = 19, 68%), and massage (n = 19, 68%) as therapies they would most like to have available for patients with chronic pain (Figure 2). Similarly, patients identified massage (n = 42, 51%), chiropractic (n = 34, 41%), and acupuncture (n = 27, 33%) as most desired. Seventeen patients (21%) expressed interest in movement therapies.

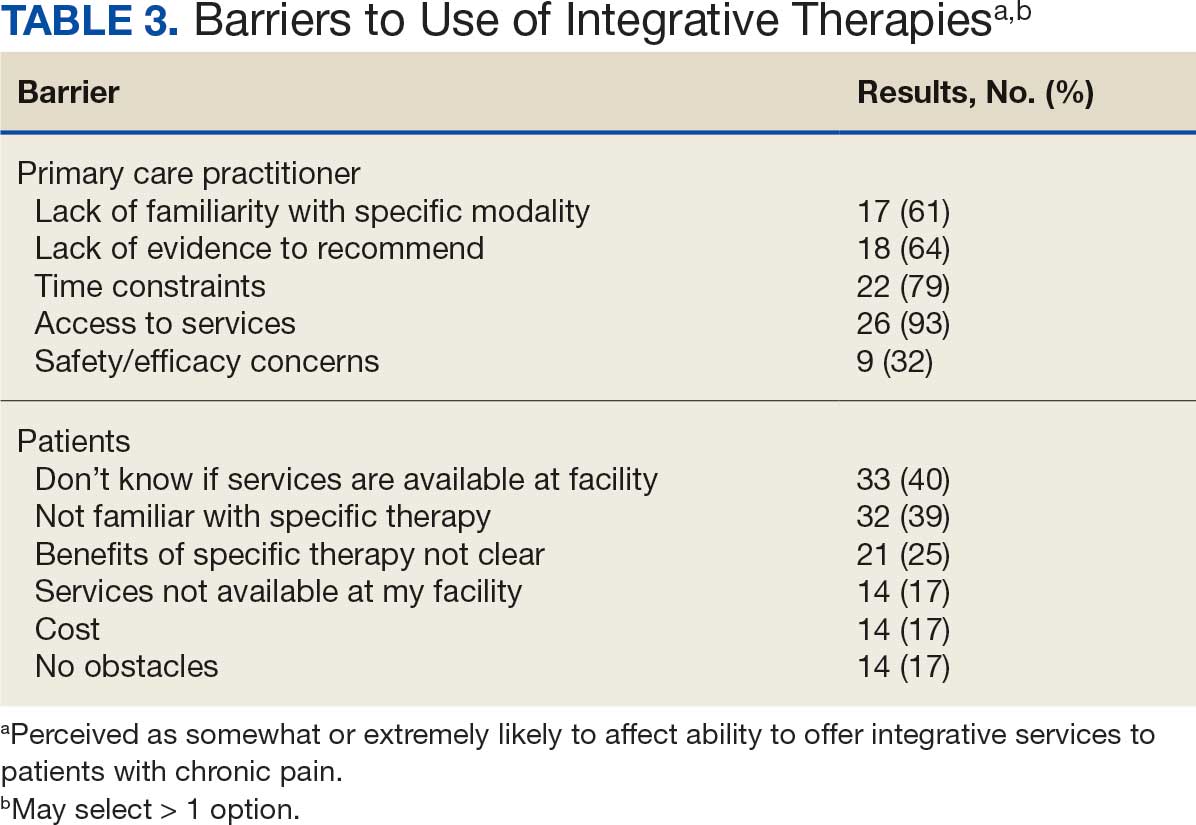

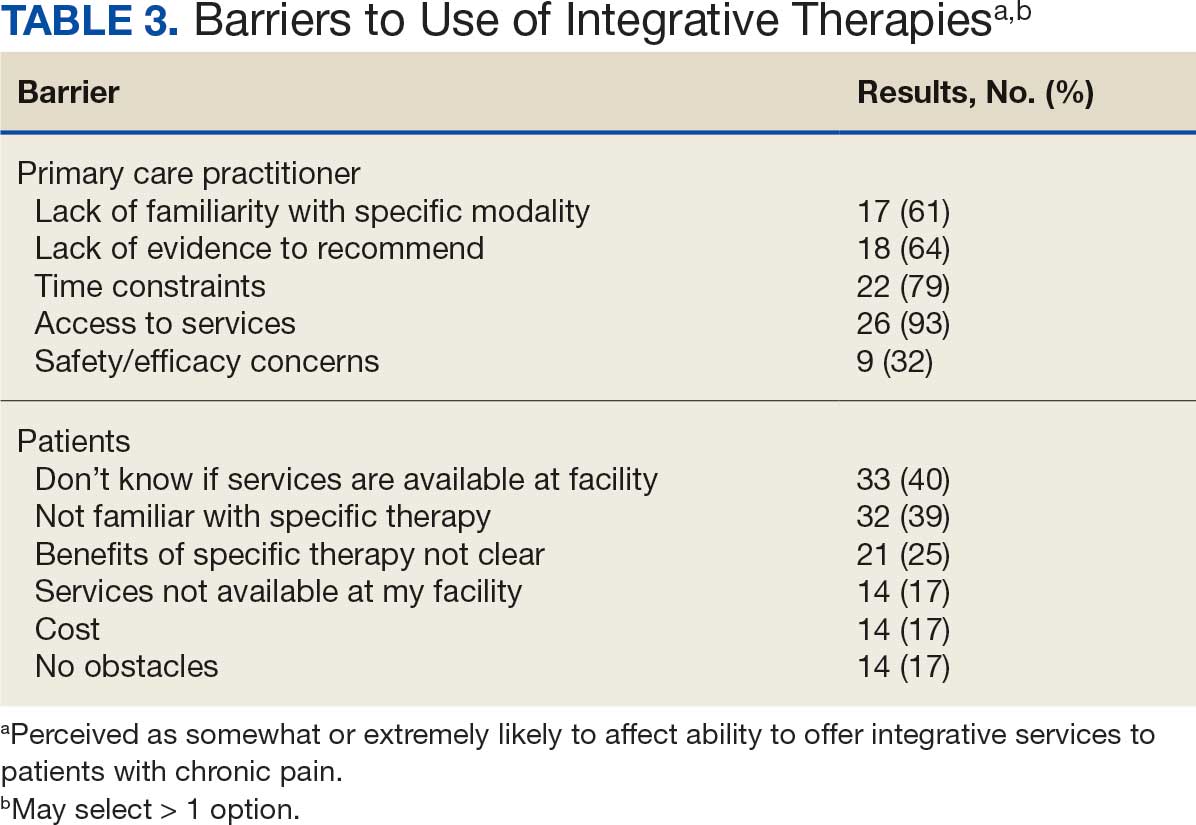

Barriers to Integrative Therapies Use

When asked about barriers to use, 26 PCPs (93%) identified access to services as a somewhat or extremely likely barrier, and 22 identified time constraints (79%) (Table 3). However, 17 PCPs (61%) noted lack of familiarity, and 18 (64%) noted a lack of scientific evidence as barriers to recommending integrative modalities. Among patients, 33 (40%) indicated not knowing what services were available at their facility as a barrier, 32 (39%) were not familiar with specific therapies, and 21 (25%) indicated a lack of clarity about the benefits of a specific therapy. Only 14 patients (17%) indicated that there were no obstacles to use.

DISCUSSION

Use of integrative therapies, including complementary treatments, is an increasingly important part of chronic pain management. This survey study suggests VA PCPs are willing to recommend integrative therapies and patients with chronic back pain both desire and use several therapies. Moreover, both groups expressed interest in greater availability of similar therapies. The results also highlight key barriers, such as knowledge gaps, that should be addressed to increase the uptake of integrative modalities for managing chronic pain.

An increasing number of US adults are using complementary health approaches, an important component of integrative therapy.12 This trend includes an increase in use for pain management, from 42.3% in 2002 to 49.2% in 2022; chiropractic care, acupuncture, and massage were most frequently used.12 Similarly, chiropractic, acupuncture and massage were most often used by this sample of veterans with chronic back pain and were identified by the highest percentages of PCPs and patients as the therapies they would most like available.

There were areas where the opinions of patients and clinicians differed. As has been seen previously reported, clinicians largely recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy while patients showed less interest.17 Additionally, while patients expressed interest in the availability of movement therapies, such as yoga, PCPs expressed more interest in other strategies, such as trigger point injections. These differences may reflect true preference or a tendency for clinicians and patients to select therapies with which they are more familiar. Additional research is needed to better understand the acceptability and potential use of integrative health treatments across a broad array of therapeutic options.

Despite VHA policy requiring facilities to provide certain complementary and integrative health modalities, almost all PCPs identified access to services as a major obstacle.15 Based on evidence and a rigorous vetting process, services currently required on-site, via telehealth, or through community partners include acupuncture and battlefield acupuncture (battlefield auricular acupuncture), biofeedback, clinical hypnosis, guided imagery, medical massage therapy, medication, tai chi/qigong, and yoga. Optional approaches, which may be made available to veterans, include chiropractic and healing touch. Outside the VHA, some states have introduced or enacted legislation mandating insurance coverage of nonpharmacological pain treatments.18 However, these requirements and mandates do not help address challenges such as the availability of trained/qualified practitioners.19,20 Ensuring access to complementary and integrative health treatments requires a more concerted effort to ensure that supply meets demand. It is also important to acknowledge the budgetary and physical space constraints that further limit access to services. Although expansion and integration of integrative medicine services remain a priority within the VA Whole Health program, implementation is contingent on available financial and infrastructure resources.

Time was also identified by PCPs as a barrier to recommending integrative therapies to patients. Developing and implementing time-efficient communication strategies for patient education such as concise talking points and informational handouts could help address this barrier. Furthermore, leveraging existing programs and engaging the entire health care team in patient education and referral could help increase integrative and complementary therapy uptake and use.

Although access and time were identified as major barriers, these findings also suggest that PCP and patient knowledge are another target area for enhancing the use of complementary and integrative therapies. Like prior research, most clinicians identified a lack of familiarity with certain services and a lack of scientific evidence as extremely or somewhat likely to affect their ability to offer integrative services to patients with chronic pain.21 Likewise, about 40% of patients identified being unfamiliar with a specific therapy as one of the major obstacles to receiving integrative therapies, with a similar number identifying PCPs as a source of information. The lack of familiarity may be due in part to the evolving nomenclature, with terms such as alternative, complementary, and integrative used to describe approaches outside what is often considered conventional medicine.10 On the other hand, there has also been considerable expansion in the number of therapies within this domain, along with an expanding evidence base. This suggests a need for targeted educational strategies for clinicians and patients, which can be rapidly deployed and continuously adapted as new therapies and evidence emerge.

Limitations

There are some inherent limitations with a survey-based approach, including sampling, non-response, and social desirability biases. In addition, this study only included PCPs and patients affiliated with a single VA medical center. Steps to mitigate these limitations included maintaining survey anonymity and reporting information about respondent characteristics to enhance transparency about the representativeness of the study findings.

CONCLUSIONS

Expanding the use of nonpharmacological pain treatments, including integrative modalities, is essential for safe and effective chronic pain management and reducing opioid use. Our findings show that VA PCPs and patients with chronic back pain are interested in and have some experience with certain integrative therapies. However, even within the context of a health care system that supports the use of integrative therapies for chronic pain as part of whole person care, increasing uptake will require addressing access and time-related constraints as well as ongoing clinician and patient education.

- Rikard SM, Strahan AE, Schmit KM, et al. Chronic pain among adults — United States, 2018-2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:379-385. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7215a1

- Yong RJ, Mullins PM, Bhattacharyya N. Prevalence of chronic pain among adults in the United States. Pain. 2022;163:E328-E332. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002291

- Nahin RL, Feinberg T, Kapos FP, Terman GW. Estimated rates of incident and persistent chronic pain among US adults, 2019-2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2313563. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.13563

- Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, Aali A, et al. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet. 2024;403:2133-2161. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00757-8 5.

- Qureshi AR, Patel M, Neumark S, et al. Prevalence of chronic non-cancer pain among military veterans: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Mil Health. 2025;171:310-314. doi:10.1136/military-2023-002554

- Feldman DE, Nahin RL. Disability among persons with chronic severe back pain: results from a nationally representative population-based sample. J Pain. 2022;23:2144-2154. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2022.07.016

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:514-530. doi:10.7326/M16-2367

- van Erp RMA, Huijnen IPJ, Jakobs MLG, Kleijnen J, Smeets RJEM. Effectiveness of primary care interventions using a biopsychosocial approach in chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Pain Practice. 2019;19:224-241. doi:10.1111/papr.12735

- Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al. Nonpharmacologic therapies for low back pain: a systematic review for an American College of physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:493-505. doi:10.7326/M16-2459

- Complementary, alternative, or integrative health: what’s in a name? National Institutes of Health, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Updated April 2021. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/complementary-alternative-or-integrative-health-whats-in-a-name.

- Taylor SL, Elwy AR. Complementary and alternative medicine for US veterans and active duty military personnel promising steps to improve their health. Med Care. 2014;52:S1-S4. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000270.

- Nahin RL, Rhee A, Stussman B. Use of complementary health approaches overall and for pain management by US adults. JAMA. 2024;331:613-615. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.26775

- Gantt CJ, Donovan N, Khung M. Veterans Affairs’ Whole Health System of Care for transitioning service members and veterans. Mil Med. 2023;188:28-32. doi:10.1093/milmed/usad047

- Bokhour BG, Hyde J, Kligler B, et al. From patient outcomes to system change: evaluating the impact of VHA’s implementation of the Whole Health System of Care. Health Serv Res. 2022;57:53-65. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13938

- Department of Veterans Affairs VHA. VHA Policy Directive 1137: Provision of Complementary and Integrative Health. December 2022. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://www.va.gov/VHApublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=10072

- Giannitrapani KF, Holliday JR, Miake-Lye IM, Hempel S, Taylor SL. Synthesizing the strength of the evidence of complementary and integrative health therapies for pain. Pain Med. 2019;20:1831-1840. doi:10.1093/pm/pnz068

- Belitskaya-Levy I, David Clark J, Shih MC, Bair MJ. Treatment preferences for chronic low back pain: views of veterans and their providers. J Pain Res. 2021;14:161-171. doi:10.2147/JPR.S290400

- Onstott TN, Hurst S, Kronick R, Tsou AC, Groessl E, McMenamin SB. Health insurance mandates for nonpharmacological pain treatments in 7 US states. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:E245737. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.5737

- Sullivan M, Leach M, Snow J, Moonaz S. The North American yoga therapy workforce survey. Complement Ther Med. 2017;31:39-48. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2017.01.006

- Bolton R, Ritter G, Highland K, Larson MJ. The relationship between capacity and utilization of nonpharmacologic therapies in the US Military Health System. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22. doi:10.1186/s12913-022-07700-4

- Stussman BJ, Nahin RL, Barnes PM, Scott R, Feinberg T, Ward BW. Reasons office-based physicians in the United States recommend common complementary health approaches to patients: an exploratory study using a national survey. J Integr Complement Med. 2022;28:651-663. doi:10.1089/jicm.2022.0493

More than 50 million US adults report experiencing chronic pain, with nearly 7% experiencing high-impact chronic pain.1-3 Chronic pain negatively affects daily function, results in lost productivity, is a leading cause of disability, and is more prevalent among veterans compared with the general population.1,2,4-6 Estimates from 2021 suggest the prevalence of chronic pain among veterans exceeds 30%; > 11% experienced high-impact chronic pain.1

Primary care practitioners (PCPs) have a prominent role in chronic pain management. Pharmacologic options for treating pain, once a mainstay of therapy, present several challenges for patients and PCPs, including drug-drug interactions and adverse effects.7 The US opioid epidemic and shift to a biopsychosocial model of chronic pain care have increased emphasis on nonpharmacologic treatment options.8,9 These include integrative modalities, which incorporate conventional approaches with an array of complementary health approaches.10-12

Integrative therapy is a prominent feature in whole person care, which may be best exemplified by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Whole Health System of care.13-14 Whole health empowers an individual to take charge of their health and well-being so they can “live their life to the fullest.”14 As implemented in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), whole health includes the use of evidence-based

METHODS

Using a cross-sectional survey design, PCPs and patients with chronic back pain affiliated with the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System were invited to participate in separate but similar surveys to assess knowledge, interest, and use of nonpharmacologic integrative modalities for the treatment of chronic pain. In May, June, and July 2023, 78 PCPs received 3 email

Both survey instruments are available upon request, were developed by the study team, and included a mix of yes/no questions, “select all that apply” items, Likert scale response items, and open-ended questions. For one question about which modalities they would like available, the respondent was instructed to select up to 5 modalities. The instruments were extensively pretested by members of the study team, which included 2 PCPs and a nonveteran with chronic back pain.

The list of integrative modalities included in the survey was derived from the tier 1 and tier 2 complementary and integrative health modalities identified in a VHA Directive on complementary and integrative health.15,16 Tier 1 approaches are considered to have sufficient evidence and must be made available to veterans either within a VA medical facility or in the community. Tier 2 approaches are generally considered safe and may be made available but do not have sufficient evidence to mandate their provision. For participant ease, the integrative modalities were divided into 5 subgroups: manual therapies, energy/biofield therapies, mental health therapies, nutrition counseling, and movement therapies. The clinician survey assessed clinicians’ training and interest, clinical and personal use, and perceived barriers to providing integrative modalities for chronic pain. Professional and personal demographic data were also collected. Similarly, the patient survey assessed use of integrative therapies, perceptions of and interest in integrative modalities, and potential barriers to use. Demographic and health-related information was also collected.

Data analysis included descriptive statistics (eg, frequency counts, means, medians) and visual graphic displays. Separate analyses were conducted for clinicians and patients in addition to a comparative analysis of the use and potential interest in integrative modalities. Analysis were conducted using R software. This study was deemed nonresearch quality improvement by the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System facility research oversight board and institutional review board approval was not solicited.

RESULTS

Twenty-eight clinicians completed the survey, yielding a participation rate of 36%. Participating clinicians had a median (IQR) age of 48 years (9.5), 15 self-identified as White (54%), 8 as Asian (29%), 15 as female (54%), 26 as non-Hispanic (93%), and 25 were medical doctors or doctors of osteopathy (89%). Nineteen (68%) worked at the main hospital outpatient clinic, and 9 practiced at community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). Thirteen respondents (46%) reported having no formal education or training in integrative approaches. Among those with prior training, 8 clinicians had nutrition counseling (29%) and 7 had psychologic therapy training (25%). Thirteen respondents (46%) also reported using integrative modalities for personal health needs: 8 used psychological therapies, 8 used movement therapies, 10 used integrative modalities for stress management or relaxation, and 8 used them for physical symptoms (Table 1).

Overall, 85 of 200 patients (43%) responded to the study survey. Two patients indicated they did not have chronic back pain and were excluded. Patients had a median (IQR) age of 66 (20) years, with 66 self-identifying as White (80%), 69 as male (83%), and 66 as non-Hispanic (80%). Forty-four patients (53%) received care at CBOCs. Forty-seven patients reported excellent, very good, or good overall health (57%), while 53 reported excellent, very good, or good mental health (64%). Fifty-nine patients reported back pain duration > 5 years (71%), and 67 (81%) indicated experiencing back pain flare-ups at least once per week over the previous 12 months. Sixty patients (72%) indicated they were somewhat or very interested in using integrative therapies as a back pain treatment; however, 40 patients (48%) indicated they had not received information about these therapies. Among those who indicated they had received information, the most frequently reported source was their PCP (41%). Most patients (72%) also reported feeling somewhat to very comfortable discussing integrative medicine therapies with their PCP.

Integrative Therapy Recommendations and Use

PCPs reported recommending multiple integrative modalities: 23 (82%) recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy, 22 (79%) recommended acupuncture, 21 (75%) recommended chiropractic, 19 (68%) recommended battlefield acupuncture, recommended massage 18 (64%), 17 (61%) recommended meditation or mindfulness, and 15 (54%) recommended movement therapies such as yoga or tai chi/qigong (Figure 1). The only therapies used by at least half of the patients were chiropractic used by 59 patients (71%) and acupuncture by 42 patients (51%). Thirty-eight patients (46%) reported massage use and 21 patients (25%) used cognitive-behavioral therapy (Table 2).

Integrative Therapies Desired

A majority of PCPs identified acupuncture (n = 20, 71%), chiropractic (n = 19, 68%), and massage (n = 19, 68%) as therapies they would most like to have available for patients with chronic pain (Figure 2). Similarly, patients identified massage (n = 42, 51%), chiropractic (n = 34, 41%), and acupuncture (n = 27, 33%) as most desired. Seventeen patients (21%) expressed interest in movement therapies.

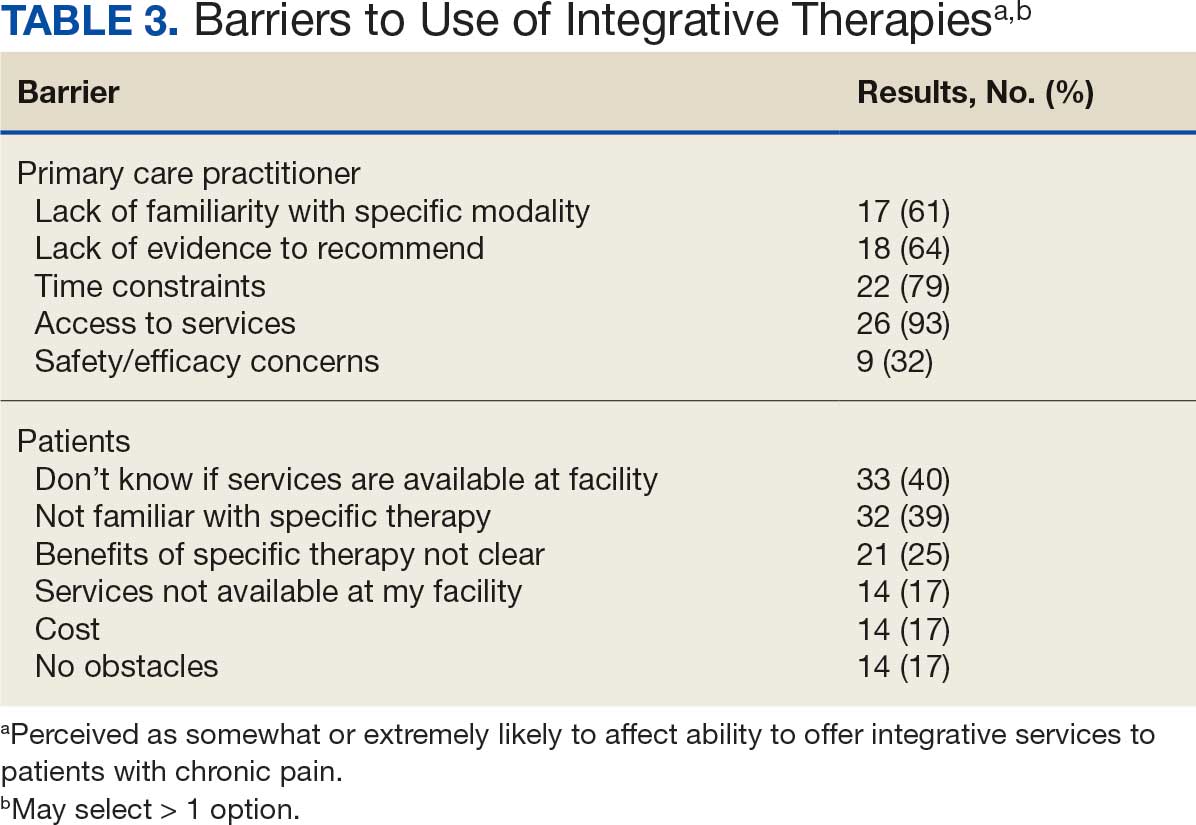

Barriers to Integrative Therapies Use

When asked about barriers to use, 26 PCPs (93%) identified access to services as a somewhat or extremely likely barrier, and 22 identified time constraints (79%) (Table 3). However, 17 PCPs (61%) noted lack of familiarity, and 18 (64%) noted a lack of scientific evidence as barriers to recommending integrative modalities. Among patients, 33 (40%) indicated not knowing what services were available at their facility as a barrier, 32 (39%) were not familiar with specific therapies, and 21 (25%) indicated a lack of clarity about the benefits of a specific therapy. Only 14 patients (17%) indicated that there were no obstacles to use.

DISCUSSION

Use of integrative therapies, including complementary treatments, is an increasingly important part of chronic pain management. This survey study suggests VA PCPs are willing to recommend integrative therapies and patients with chronic back pain both desire and use several therapies. Moreover, both groups expressed interest in greater availability of similar therapies. The results also highlight key barriers, such as knowledge gaps, that should be addressed to increase the uptake of integrative modalities for managing chronic pain.

An increasing number of US adults are using complementary health approaches, an important component of integrative therapy.12 This trend includes an increase in use for pain management, from 42.3% in 2002 to 49.2% in 2022; chiropractic care, acupuncture, and massage were most frequently used.12 Similarly, chiropractic, acupuncture and massage were most often used by this sample of veterans with chronic back pain and were identified by the highest percentages of PCPs and patients as the therapies they would most like available.

There were areas where the opinions of patients and clinicians differed. As has been seen previously reported, clinicians largely recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy while patients showed less interest.17 Additionally, while patients expressed interest in the availability of movement therapies, such as yoga, PCPs expressed more interest in other strategies, such as trigger point injections. These differences may reflect true preference or a tendency for clinicians and patients to select therapies with which they are more familiar. Additional research is needed to better understand the acceptability and potential use of integrative health treatments across a broad array of therapeutic options.

Despite VHA policy requiring facilities to provide certain complementary and integrative health modalities, almost all PCPs identified access to services as a major obstacle.15 Based on evidence and a rigorous vetting process, services currently required on-site, via telehealth, or through community partners include acupuncture and battlefield acupuncture (battlefield auricular acupuncture), biofeedback, clinical hypnosis, guided imagery, medical massage therapy, medication, tai chi/qigong, and yoga. Optional approaches, which may be made available to veterans, include chiropractic and healing touch. Outside the VHA, some states have introduced or enacted legislation mandating insurance coverage of nonpharmacological pain treatments.18 However, these requirements and mandates do not help address challenges such as the availability of trained/qualified practitioners.19,20 Ensuring access to complementary and integrative health treatments requires a more concerted effort to ensure that supply meets demand. It is also important to acknowledge the budgetary and physical space constraints that further limit access to services. Although expansion and integration of integrative medicine services remain a priority within the VA Whole Health program, implementation is contingent on available financial and infrastructure resources.

Time was also identified by PCPs as a barrier to recommending integrative therapies to patients. Developing and implementing time-efficient communication strategies for patient education such as concise talking points and informational handouts could help address this barrier. Furthermore, leveraging existing programs and engaging the entire health care team in patient education and referral could help increase integrative and complementary therapy uptake and use.

Although access and time were identified as major barriers, these findings also suggest that PCP and patient knowledge are another target area for enhancing the use of complementary and integrative therapies. Like prior research, most clinicians identified a lack of familiarity with certain services and a lack of scientific evidence as extremely or somewhat likely to affect their ability to offer integrative services to patients with chronic pain.21 Likewise, about 40% of patients identified being unfamiliar with a specific therapy as one of the major obstacles to receiving integrative therapies, with a similar number identifying PCPs as a source of information. The lack of familiarity may be due in part to the evolving nomenclature, with terms such as alternative, complementary, and integrative used to describe approaches outside what is often considered conventional medicine.10 On the other hand, there has also been considerable expansion in the number of therapies within this domain, along with an expanding evidence base. This suggests a need for targeted educational strategies for clinicians and patients, which can be rapidly deployed and continuously adapted as new therapies and evidence emerge.

Limitations

There are some inherent limitations with a survey-based approach, including sampling, non-response, and social desirability biases. In addition, this study only included PCPs and patients affiliated with a single VA medical center. Steps to mitigate these limitations included maintaining survey anonymity and reporting information about respondent characteristics to enhance transparency about the representativeness of the study findings.

CONCLUSIONS

Expanding the use of nonpharmacological pain treatments, including integrative modalities, is essential for safe and effective chronic pain management and reducing opioid use. Our findings show that VA PCPs and patients with chronic back pain are interested in and have some experience with certain integrative therapies. However, even within the context of a health care system that supports the use of integrative therapies for chronic pain as part of whole person care, increasing uptake will require addressing access and time-related constraints as well as ongoing clinician and patient education.

More than 50 million US adults report experiencing chronic pain, with nearly 7% experiencing high-impact chronic pain.1-3 Chronic pain negatively affects daily function, results in lost productivity, is a leading cause of disability, and is more prevalent among veterans compared with the general population.1,2,4-6 Estimates from 2021 suggest the prevalence of chronic pain among veterans exceeds 30%; > 11% experienced high-impact chronic pain.1

Primary care practitioners (PCPs) have a prominent role in chronic pain management. Pharmacologic options for treating pain, once a mainstay of therapy, present several challenges for patients and PCPs, including drug-drug interactions and adverse effects.7 The US opioid epidemic and shift to a biopsychosocial model of chronic pain care have increased emphasis on nonpharmacologic treatment options.8,9 These include integrative modalities, which incorporate conventional approaches with an array of complementary health approaches.10-12

Integrative therapy is a prominent feature in whole person care, which may be best exemplified by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Whole Health System of care.13-14 Whole health empowers an individual to take charge of their health and well-being so they can “live their life to the fullest.”14 As implemented in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), whole health includes the use of evidence-based

METHODS

Using a cross-sectional survey design, PCPs and patients with chronic back pain affiliated with the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System were invited to participate in separate but similar surveys to assess knowledge, interest, and use of nonpharmacologic integrative modalities for the treatment of chronic pain. In May, June, and July 2023, 78 PCPs received 3 email

Both survey instruments are available upon request, were developed by the study team, and included a mix of yes/no questions, “select all that apply” items, Likert scale response items, and open-ended questions. For one question about which modalities they would like available, the respondent was instructed to select up to 5 modalities. The instruments were extensively pretested by members of the study team, which included 2 PCPs and a nonveteran with chronic back pain.

The list of integrative modalities included in the survey was derived from the tier 1 and tier 2 complementary and integrative health modalities identified in a VHA Directive on complementary and integrative health.15,16 Tier 1 approaches are considered to have sufficient evidence and must be made available to veterans either within a VA medical facility or in the community. Tier 2 approaches are generally considered safe and may be made available but do not have sufficient evidence to mandate their provision. For participant ease, the integrative modalities were divided into 5 subgroups: manual therapies, energy/biofield therapies, mental health therapies, nutrition counseling, and movement therapies. The clinician survey assessed clinicians’ training and interest, clinical and personal use, and perceived barriers to providing integrative modalities for chronic pain. Professional and personal demographic data were also collected. Similarly, the patient survey assessed use of integrative therapies, perceptions of and interest in integrative modalities, and potential barriers to use. Demographic and health-related information was also collected.

Data analysis included descriptive statistics (eg, frequency counts, means, medians) and visual graphic displays. Separate analyses were conducted for clinicians and patients in addition to a comparative analysis of the use and potential interest in integrative modalities. Analysis were conducted using R software. This study was deemed nonresearch quality improvement by the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System facility research oversight board and institutional review board approval was not solicited.

RESULTS

Twenty-eight clinicians completed the survey, yielding a participation rate of 36%. Participating clinicians had a median (IQR) age of 48 years (9.5), 15 self-identified as White (54%), 8 as Asian (29%), 15 as female (54%), 26 as non-Hispanic (93%), and 25 were medical doctors or doctors of osteopathy (89%). Nineteen (68%) worked at the main hospital outpatient clinic, and 9 practiced at community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). Thirteen respondents (46%) reported having no formal education or training in integrative approaches. Among those with prior training, 8 clinicians had nutrition counseling (29%) and 7 had psychologic therapy training (25%). Thirteen respondents (46%) also reported using integrative modalities for personal health needs: 8 used psychological therapies, 8 used movement therapies, 10 used integrative modalities for stress management or relaxation, and 8 used them for physical symptoms (Table 1).

Overall, 85 of 200 patients (43%) responded to the study survey. Two patients indicated they did not have chronic back pain and were excluded. Patients had a median (IQR) age of 66 (20) years, with 66 self-identifying as White (80%), 69 as male (83%), and 66 as non-Hispanic (80%). Forty-four patients (53%) received care at CBOCs. Forty-seven patients reported excellent, very good, or good overall health (57%), while 53 reported excellent, very good, or good mental health (64%). Fifty-nine patients reported back pain duration > 5 years (71%), and 67 (81%) indicated experiencing back pain flare-ups at least once per week over the previous 12 months. Sixty patients (72%) indicated they were somewhat or very interested in using integrative therapies as a back pain treatment; however, 40 patients (48%) indicated they had not received information about these therapies. Among those who indicated they had received information, the most frequently reported source was their PCP (41%). Most patients (72%) also reported feeling somewhat to very comfortable discussing integrative medicine therapies with their PCP.

Integrative Therapy Recommendations and Use

PCPs reported recommending multiple integrative modalities: 23 (82%) recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy, 22 (79%) recommended acupuncture, 21 (75%) recommended chiropractic, 19 (68%) recommended battlefield acupuncture, recommended massage 18 (64%), 17 (61%) recommended meditation or mindfulness, and 15 (54%) recommended movement therapies such as yoga or tai chi/qigong (Figure 1). The only therapies used by at least half of the patients were chiropractic used by 59 patients (71%) and acupuncture by 42 patients (51%). Thirty-eight patients (46%) reported massage use and 21 patients (25%) used cognitive-behavioral therapy (Table 2).

Integrative Therapies Desired

A majority of PCPs identified acupuncture (n = 20, 71%), chiropractic (n = 19, 68%), and massage (n = 19, 68%) as therapies they would most like to have available for patients with chronic pain (Figure 2). Similarly, patients identified massage (n = 42, 51%), chiropractic (n = 34, 41%), and acupuncture (n = 27, 33%) as most desired. Seventeen patients (21%) expressed interest in movement therapies.

Barriers to Integrative Therapies Use

When asked about barriers to use, 26 PCPs (93%) identified access to services as a somewhat or extremely likely barrier, and 22 identified time constraints (79%) (Table 3). However, 17 PCPs (61%) noted lack of familiarity, and 18 (64%) noted a lack of scientific evidence as barriers to recommending integrative modalities. Among patients, 33 (40%) indicated not knowing what services were available at their facility as a barrier, 32 (39%) were not familiar with specific therapies, and 21 (25%) indicated a lack of clarity about the benefits of a specific therapy. Only 14 patients (17%) indicated that there were no obstacles to use.

DISCUSSION

Use of integrative therapies, including complementary treatments, is an increasingly important part of chronic pain management. This survey study suggests VA PCPs are willing to recommend integrative therapies and patients with chronic back pain both desire and use several therapies. Moreover, both groups expressed interest in greater availability of similar therapies. The results also highlight key barriers, such as knowledge gaps, that should be addressed to increase the uptake of integrative modalities for managing chronic pain.

An increasing number of US adults are using complementary health approaches, an important component of integrative therapy.12 This trend includes an increase in use for pain management, from 42.3% in 2002 to 49.2% in 2022; chiropractic care, acupuncture, and massage were most frequently used.12 Similarly, chiropractic, acupuncture and massage were most often used by this sample of veterans with chronic back pain and were identified by the highest percentages of PCPs and patients as the therapies they would most like available.

There were areas where the opinions of patients and clinicians differed. As has been seen previously reported, clinicians largely recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy while patients showed less interest.17 Additionally, while patients expressed interest in the availability of movement therapies, such as yoga, PCPs expressed more interest in other strategies, such as trigger point injections. These differences may reflect true preference or a tendency for clinicians and patients to select therapies with which they are more familiar. Additional research is needed to better understand the acceptability and potential use of integrative health treatments across a broad array of therapeutic options.

Despite VHA policy requiring facilities to provide certain complementary and integrative health modalities, almost all PCPs identified access to services as a major obstacle.15 Based on evidence and a rigorous vetting process, services currently required on-site, via telehealth, or through community partners include acupuncture and battlefield acupuncture (battlefield auricular acupuncture), biofeedback, clinical hypnosis, guided imagery, medical massage therapy, medication, tai chi/qigong, and yoga. Optional approaches, which may be made available to veterans, include chiropractic and healing touch. Outside the VHA, some states have introduced or enacted legislation mandating insurance coverage of nonpharmacological pain treatments.18 However, these requirements and mandates do not help address challenges such as the availability of trained/qualified practitioners.19,20 Ensuring access to complementary and integrative health treatments requires a more concerted effort to ensure that supply meets demand. It is also important to acknowledge the budgetary and physical space constraints that further limit access to services. Although expansion and integration of integrative medicine services remain a priority within the VA Whole Health program, implementation is contingent on available financial and infrastructure resources.

Time was also identified by PCPs as a barrier to recommending integrative therapies to patients. Developing and implementing time-efficient communication strategies for patient education such as concise talking points and informational handouts could help address this barrier. Furthermore, leveraging existing programs and engaging the entire health care team in patient education and referral could help increase integrative and complementary therapy uptake and use.

Although access and time were identified as major barriers, these findings also suggest that PCP and patient knowledge are another target area for enhancing the use of complementary and integrative therapies. Like prior research, most clinicians identified a lack of familiarity with certain services and a lack of scientific evidence as extremely or somewhat likely to affect their ability to offer integrative services to patients with chronic pain.21 Likewise, about 40% of patients identified being unfamiliar with a specific therapy as one of the major obstacles to receiving integrative therapies, with a similar number identifying PCPs as a source of information. The lack of familiarity may be due in part to the evolving nomenclature, with terms such as alternative, complementary, and integrative used to describe approaches outside what is often considered conventional medicine.10 On the other hand, there has also been considerable expansion in the number of therapies within this domain, along with an expanding evidence base. This suggests a need for targeted educational strategies for clinicians and patients, which can be rapidly deployed and continuously adapted as new therapies and evidence emerge.

Limitations

There are some inherent limitations with a survey-based approach, including sampling, non-response, and social desirability biases. In addition, this study only included PCPs and patients affiliated with a single VA medical center. Steps to mitigate these limitations included maintaining survey anonymity and reporting information about respondent characteristics to enhance transparency about the representativeness of the study findings.

CONCLUSIONS

Expanding the use of nonpharmacological pain treatments, including integrative modalities, is essential for safe and effective chronic pain management and reducing opioid use. Our findings show that VA PCPs and patients with chronic back pain are interested in and have some experience with certain integrative therapies. However, even within the context of a health care system that supports the use of integrative therapies for chronic pain as part of whole person care, increasing uptake will require addressing access and time-related constraints as well as ongoing clinician and patient education.

- Rikard SM, Strahan AE, Schmit KM, et al. Chronic pain among adults — United States, 2018-2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:379-385. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7215a1

- Yong RJ, Mullins PM, Bhattacharyya N. Prevalence of chronic pain among adults in the United States. Pain. 2022;163:E328-E332. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002291

- Nahin RL, Feinberg T, Kapos FP, Terman GW. Estimated rates of incident and persistent chronic pain among US adults, 2019-2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2313563. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.13563

- Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, Aali A, et al. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet. 2024;403:2133-2161. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00757-8 5.

- Qureshi AR, Patel M, Neumark S, et al. Prevalence of chronic non-cancer pain among military veterans: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Mil Health. 2025;171:310-314. doi:10.1136/military-2023-002554

- Feldman DE, Nahin RL. Disability among persons with chronic severe back pain: results from a nationally representative population-based sample. J Pain. 2022;23:2144-2154. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2022.07.016

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:514-530. doi:10.7326/M16-2367

- van Erp RMA, Huijnen IPJ, Jakobs MLG, Kleijnen J, Smeets RJEM. Effectiveness of primary care interventions using a biopsychosocial approach in chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Pain Practice. 2019;19:224-241. doi:10.1111/papr.12735

- Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al. Nonpharmacologic therapies for low back pain: a systematic review for an American College of physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:493-505. doi:10.7326/M16-2459

- Complementary, alternative, or integrative health: what’s in a name? National Institutes of Health, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Updated April 2021. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/complementary-alternative-or-integrative-health-whats-in-a-name.

- Taylor SL, Elwy AR. Complementary and alternative medicine for US veterans and active duty military personnel promising steps to improve their health. Med Care. 2014;52:S1-S4. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000270.

- Nahin RL, Rhee A, Stussman B. Use of complementary health approaches overall and for pain management by US adults. JAMA. 2024;331:613-615. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.26775

- Gantt CJ, Donovan N, Khung M. Veterans Affairs’ Whole Health System of Care for transitioning service members and veterans. Mil Med. 2023;188:28-32. doi:10.1093/milmed/usad047

- Bokhour BG, Hyde J, Kligler B, et al. From patient outcomes to system change: evaluating the impact of VHA’s implementation of the Whole Health System of Care. Health Serv Res. 2022;57:53-65. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13938

- Department of Veterans Affairs VHA. VHA Policy Directive 1137: Provision of Complementary and Integrative Health. December 2022. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://www.va.gov/VHApublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=10072

- Giannitrapani KF, Holliday JR, Miake-Lye IM, Hempel S, Taylor SL. Synthesizing the strength of the evidence of complementary and integrative health therapies for pain. Pain Med. 2019;20:1831-1840. doi:10.1093/pm/pnz068

- Belitskaya-Levy I, David Clark J, Shih MC, Bair MJ. Treatment preferences for chronic low back pain: views of veterans and their providers. J Pain Res. 2021;14:161-171. doi:10.2147/JPR.S290400

- Onstott TN, Hurst S, Kronick R, Tsou AC, Groessl E, McMenamin SB. Health insurance mandates for nonpharmacological pain treatments in 7 US states. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:E245737. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.5737

- Sullivan M, Leach M, Snow J, Moonaz S. The North American yoga therapy workforce survey. Complement Ther Med. 2017;31:39-48. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2017.01.006

- Bolton R, Ritter G, Highland K, Larson MJ. The relationship between capacity and utilization of nonpharmacologic therapies in the US Military Health System. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22. doi:10.1186/s12913-022-07700-4

- Stussman BJ, Nahin RL, Barnes PM, Scott R, Feinberg T, Ward BW. Reasons office-based physicians in the United States recommend common complementary health approaches to patients: an exploratory study using a national survey. J Integr Complement Med. 2022;28:651-663. doi:10.1089/jicm.2022.0493

- Rikard SM, Strahan AE, Schmit KM, et al. Chronic pain among adults — United States, 2018-2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:379-385. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7215a1

- Yong RJ, Mullins PM, Bhattacharyya N. Prevalence of chronic pain among adults in the United States. Pain. 2022;163:E328-E332. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002291

- Nahin RL, Feinberg T, Kapos FP, Terman GW. Estimated rates of incident and persistent chronic pain among US adults, 2019-2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2313563. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.13563

- Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, Aali A, et al. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet. 2024;403:2133-2161. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00757-8 5.

- Qureshi AR, Patel M, Neumark S, et al. Prevalence of chronic non-cancer pain among military veterans: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Mil Health. 2025;171:310-314. doi:10.1136/military-2023-002554

- Feldman DE, Nahin RL. Disability among persons with chronic severe back pain: results from a nationally representative population-based sample. J Pain. 2022;23:2144-2154. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2022.07.016

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:514-530. doi:10.7326/M16-2367

- van Erp RMA, Huijnen IPJ, Jakobs MLG, Kleijnen J, Smeets RJEM. Effectiveness of primary care interventions using a biopsychosocial approach in chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Pain Practice. 2019;19:224-241. doi:10.1111/papr.12735

- Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al. Nonpharmacologic therapies for low back pain: a systematic review for an American College of physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:493-505. doi:10.7326/M16-2459

- Complementary, alternative, or integrative health: what’s in a name? National Institutes of Health, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Updated April 2021. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/complementary-alternative-or-integrative-health-whats-in-a-name.

- Taylor SL, Elwy AR. Complementary and alternative medicine for US veterans and active duty military personnel promising steps to improve their health. Med Care. 2014;52:S1-S4. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000270.

- Nahin RL, Rhee A, Stussman B. Use of complementary health approaches overall and for pain management by US adults. JAMA. 2024;331:613-615. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.26775

- Gantt CJ, Donovan N, Khung M. Veterans Affairs’ Whole Health System of Care for transitioning service members and veterans. Mil Med. 2023;188:28-32. doi:10.1093/milmed/usad047

- Bokhour BG, Hyde J, Kligler B, et al. From patient outcomes to system change: evaluating the impact of VHA’s implementation of the Whole Health System of Care. Health Serv Res. 2022;57:53-65. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13938

- Department of Veterans Affairs VHA. VHA Policy Directive 1137: Provision of Complementary and Integrative Health. December 2022. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://www.va.gov/VHApublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=10072

- Giannitrapani KF, Holliday JR, Miake-Lye IM, Hempel S, Taylor SL. Synthesizing the strength of the evidence of complementary and integrative health therapies for pain. Pain Med. 2019;20:1831-1840. doi:10.1093/pm/pnz068

- Belitskaya-Levy I, David Clark J, Shih MC, Bair MJ. Treatment preferences for chronic low back pain: views of veterans and their providers. J Pain Res. 2021;14:161-171. doi:10.2147/JPR.S290400

- Onstott TN, Hurst S, Kronick R, Tsou AC, Groessl E, McMenamin SB. Health insurance mandates for nonpharmacological pain treatments in 7 US states. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:E245737. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.5737

- Sullivan M, Leach M, Snow J, Moonaz S. The North American yoga therapy workforce survey. Complement Ther Med. 2017;31:39-48. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2017.01.006

- Bolton R, Ritter G, Highland K, Larson MJ. The relationship between capacity and utilization of nonpharmacologic therapies in the US Military Health System. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22. doi:10.1186/s12913-022-07700-4

- Stussman BJ, Nahin RL, Barnes PM, Scott R, Feinberg T, Ward BW. Reasons office-based physicians in the United States recommend common complementary health approaches to patients: an exploratory study using a national survey. J Integr Complement Med. 2022;28:651-663. doi:10.1089/jicm.2022.0493

Primary Care Clinician and Patient Knowledge, Interest, and Use of Integrative Treatment Options for Chronic Low Back Pain Management

Primary Care Clinician and Patient Knowledge, Interest, and Use of Integrative Treatment Options for Chronic Low Back Pain Management

Rural Cancer Survivors Are More Likely to Have Chronic Pain

TOPLINE:

Rural cancer survivors experience significantly higher rates of chronic pain at 43.0% than those among urban survivors at 33.5%. Even after controlling for demographics and health conditions, rural residents showed 21% higher odds of experiencing chronic pain.

METHODOLOGY:

- Chronic pain prevalence among cancer survivors is twice that of the general US population and is associated with numerous negative outcomes. Rural residence is frequently linked to debilitating long-term survivorship effects, and current data lack information on whether chronic pain disparity exists specifically for rural cancer survivors.

- Researchers pooled data from the 2019–2021 and 2023 National Health Interview Survey, a cross–sectional survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics.

- Analysis included 5542 adult cancer survivors diagnosed within the previous 5 years, with 51.6% female participants and 48.4% male participants.

- Chronic pain was defined as pain experienced on most or all days over the past 3 months, following National Center for Health Statistics conventions.

- Rural residence classification was based on noncore or nonmetropolitan counties using the modified National Center for Health Statistics Urban–Rural Classification Scheme for Counties.

TAKEAWAY:

- Rural cancer survivors showed significantly higher odds of experiencing chronic pain compared with urban survivors (odds ratio [OR], 1.21; 95% CI, 1.01-1.45).

- Rural survivors were more likely to be non–Hispanic White, have less than a 4-year college degree, have an income below 200% of the federal poverty level, and have slightly more chronic health conditions.

- Having an income below 100% of the federal poverty level was associated with doubled odds of chronic pain (OR, 2.07; 95% CI, 1.54-2.77) compared with having an income at least four times the federal poverty level.

- Each additional health condition increased the odds of experiencing chronic pain by 32% (OR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.26-1.39).

IN PRACTICE:

“Policymakers and health systems should work to close this gap by increasing the availability of pain management resources for rural cancer survivors. Approaches could include innovative payment models for integrative medicine in rural areas or supporting rural clinician access to pain specialists,” the authors of the study wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Hyojin Choi, PhD, Department of Family Medicine, The Robert Larner MD College of Medicine, University of Vermont in Burlington, Vermont. It was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors note that the cross–sectional design of the study and limited information on individual respondents’ use of multimodal pain treatment options constrain the interpretation of findings.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors did not report any relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Rural cancer survivors experience significantly higher rates of chronic pain at 43.0% than those among urban survivors at 33.5%. Even after controlling for demographics and health conditions, rural residents showed 21% higher odds of experiencing chronic pain.

METHODOLOGY:

- Chronic pain prevalence among cancer survivors is twice that of the general US population and is associated with numerous negative outcomes. Rural residence is frequently linked to debilitating long-term survivorship effects, and current data lack information on whether chronic pain disparity exists specifically for rural cancer survivors.

- Researchers pooled data from the 2019–2021 and 2023 National Health Interview Survey, a cross–sectional survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics.

- Analysis included 5542 adult cancer survivors diagnosed within the previous 5 years, with 51.6% female participants and 48.4% male participants.

- Chronic pain was defined as pain experienced on most or all days over the past 3 months, following National Center for Health Statistics conventions.

- Rural residence classification was based on noncore or nonmetropolitan counties using the modified National Center for Health Statistics Urban–Rural Classification Scheme for Counties.

TAKEAWAY:

- Rural cancer survivors showed significantly higher odds of experiencing chronic pain compared with urban survivors (odds ratio [OR], 1.21; 95% CI, 1.01-1.45).

- Rural survivors were more likely to be non–Hispanic White, have less than a 4-year college degree, have an income below 200% of the federal poverty level, and have slightly more chronic health conditions.

- Having an income below 100% of the federal poverty level was associated with doubled odds of chronic pain (OR, 2.07; 95% CI, 1.54-2.77) compared with having an income at least four times the federal poverty level.

- Each additional health condition increased the odds of experiencing chronic pain by 32% (OR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.26-1.39).

IN PRACTICE:

“Policymakers and health systems should work to close this gap by increasing the availability of pain management resources for rural cancer survivors. Approaches could include innovative payment models for integrative medicine in rural areas or supporting rural clinician access to pain specialists,” the authors of the study wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Hyojin Choi, PhD, Department of Family Medicine, The Robert Larner MD College of Medicine, University of Vermont in Burlington, Vermont. It was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors note that the cross–sectional design of the study and limited information on individual respondents’ use of multimodal pain treatment options constrain the interpretation of findings.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors did not report any relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Rural cancer survivors experience significantly higher rates of chronic pain at 43.0% than those among urban survivors at 33.5%. Even after controlling for demographics and health conditions, rural residents showed 21% higher odds of experiencing chronic pain.

METHODOLOGY:

- Chronic pain prevalence among cancer survivors is twice that of the general US population and is associated with numerous negative outcomes. Rural residence is frequently linked to debilitating long-term survivorship effects, and current data lack information on whether chronic pain disparity exists specifically for rural cancer survivors.

- Researchers pooled data from the 2019–2021 and 2023 National Health Interview Survey, a cross–sectional survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics.

- Analysis included 5542 adult cancer survivors diagnosed within the previous 5 years, with 51.6% female participants and 48.4% male participants.

- Chronic pain was defined as pain experienced on most or all days over the past 3 months, following National Center for Health Statistics conventions.

- Rural residence classification was based on noncore or nonmetropolitan counties using the modified National Center for Health Statistics Urban–Rural Classification Scheme for Counties.

TAKEAWAY:

- Rural cancer survivors showed significantly higher odds of experiencing chronic pain compared with urban survivors (odds ratio [OR], 1.21; 95% CI, 1.01-1.45).

- Rural survivors were more likely to be non–Hispanic White, have less than a 4-year college degree, have an income below 200% of the federal poverty level, and have slightly more chronic health conditions.

- Having an income below 100% of the federal poverty level was associated with doubled odds of chronic pain (OR, 2.07; 95% CI, 1.54-2.77) compared with having an income at least four times the federal poverty level.

- Each additional health condition increased the odds of experiencing chronic pain by 32% (OR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.26-1.39).

IN PRACTICE:

“Policymakers and health systems should work to close this gap by increasing the availability of pain management resources for rural cancer survivors. Approaches could include innovative payment models for integrative medicine in rural areas or supporting rural clinician access to pain specialists,” the authors of the study wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Hyojin Choi, PhD, Department of Family Medicine, The Robert Larner MD College of Medicine, University of Vermont in Burlington, Vermont. It was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors note that the cross–sectional design of the study and limited information on individual respondents’ use of multimodal pain treatment options constrain the interpretation of findings.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors did not report any relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A True Community: The Vet-to-Vet Program for Chronic Pain

A True Community: The Vet-to-Vet Program for Chronic Pain

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has continued to advance its understanding and treatment of chronic pain. The VHA National Pain Management Strategy emphasizes the significance of the social context of pain while underscoring the importance of self-management.1 This established strategy ensures that all veterans have access to the appropriate pain care in the proper setting.2 VHA has instituted a stepped care model of pain management, delineating the domains of primary care, secondary consultative services, and tertiary care.3 This directive emphasized a biopsychosocial approach to pain management to prioritize the relationship between biological, psychological, and social factors that influence how veterans experience pain and should commensurately influence how it is managed.

The VHA Office of Patient-Centered Care and Cultural Transformation implemented the Whole Health System of Care as part of the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, which included a VHA directive to expand pain management.4,5 Reorientation within this system shifts from defining veterans as passive care recipients to viewing them as active partners in their own care and health. This partnership places additional emphasis on peer-led explorations of mission, aspiration, and purpose.6

Peer-led groups, also known as mutual aid, mutual support, and mutual help groups, have historically been successful for patients undergoing treatment for substance use disorders (eg, Alcoholics Anonymous).7 Mutual help groups have 3 defining characteristics. First, they are run by participants, not professionals, though the latter may have been integral in the founding of the groups. Second, participants share a similar problem (eg, disease state, experience, disposition). Finally, there is a reciprocal exchange of information and psychological support among participants.8,9 Mutual help groups that address chronic pain are rare but becoming more common.10-12 Emerging evidence suggests a positive relationship between peer support and improved well-being, self-efficacy, pain management, and pain self-management skills (eg, activity pacing).13-15

Storytelling as a tool for healing has a long history in indigenous and Western medical traditions.16-19 This includes the treatment of chronic disease, including pain.20,21 The use of storytelling in health care overlaps with the role it plays within many mutual help groups focused on chronic disease treatment.22 Storytelling allows an individual to share their experience with a disease, and take a more active role in their health, and facilitate stronger bonds with others.22 In effect, storytelling is not only important to group cohesion—it also plays a role in an individual’s healing.

Vet-to-Vet

The VHA Office of Rural Health funds Vet-to-Vet, a peer-to-peer program to address limited access to care for rural veterans with chronic pain. Similar to the VHA National Pain Management Strategy, Vet-to-Vet is grounded in the significance of the social context of pain and underscores the importance of self-management.1 The program combines pain care, mutual help, and storytelling to support veterans living with chronic pain. While the primary focus of Vet-to-Vet is rural veterans, the program serves any veteran experiencing chronic pain who is isolated from services, including home-bound urban veterans.

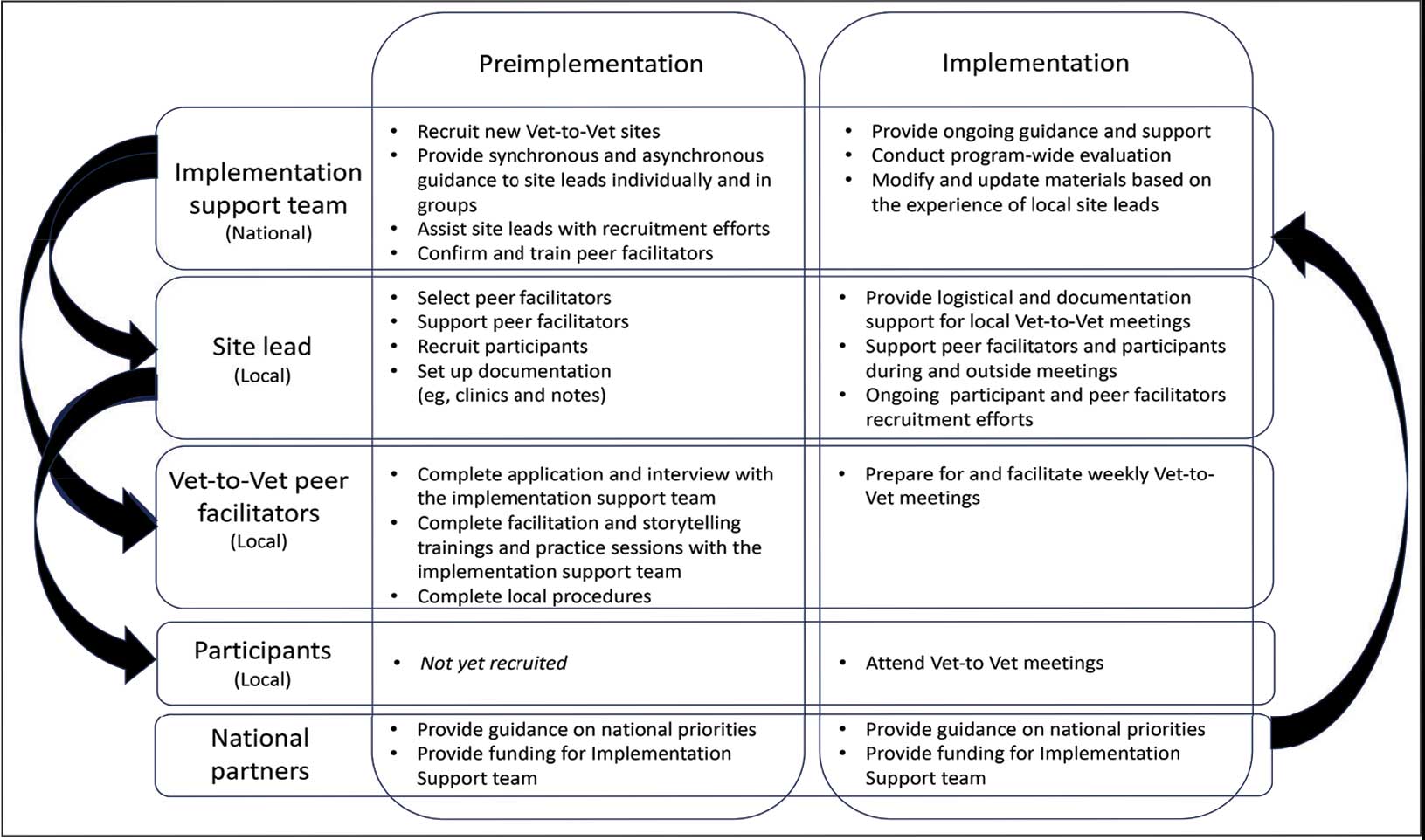

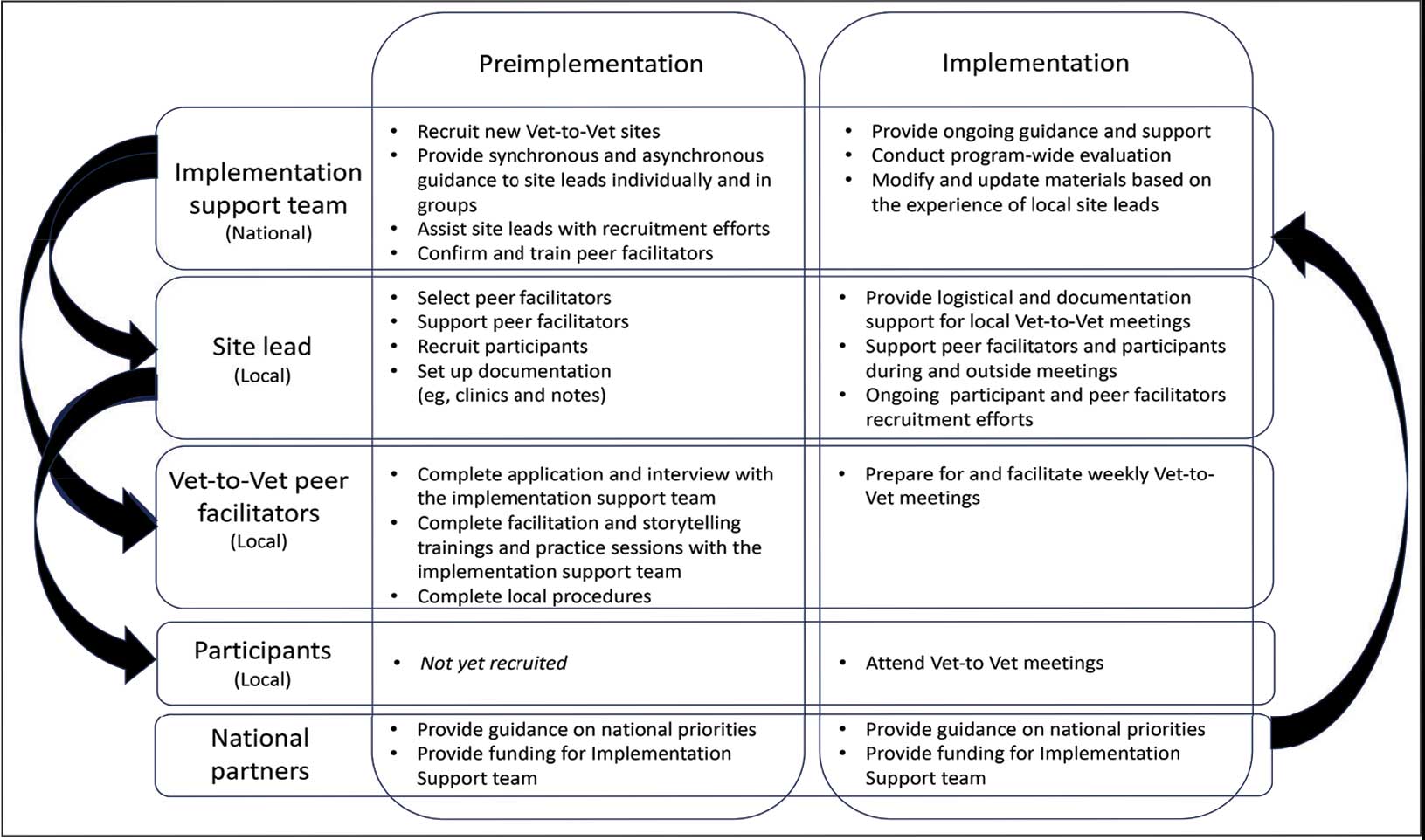

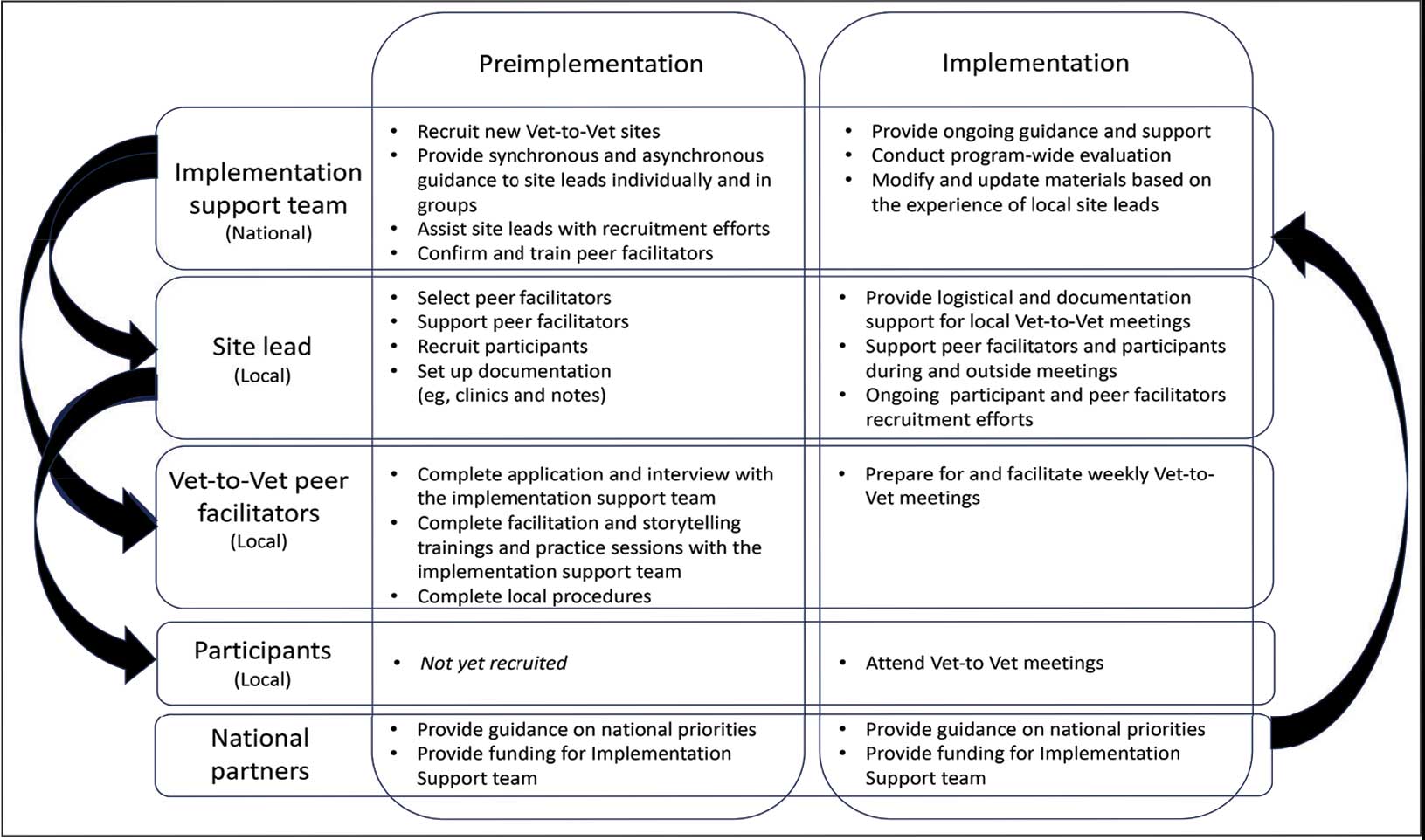

Following mutual help principles, Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators lead weekly online drop-in meetings. Meetings follow the general structure of reiterating group ground rules and sharing an individual pain story, followed by open discussions centered on well-being, chronic pain management, or any topic the group wishes to discuss. Meetings typically end with a mindfulness exercise. The organizational structure that supports Vet-to-Vet includes the implementation support team, site leads, Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators, and national partners (Figure 1).

Implementation Support Team

The implementation support team consists of a principal investigator, coinvestigator, program manager, and program support specialist. The team provides facilitator training, monthly community practice sessions for Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators and site leads, and weekly office hours for site leads. The implementation support team also recruits new Vet-to-Vet sites; potential new locations ideally have an existing whole health program, leadership support, committed site and cosite leads, and ≥ 3 peer facilitator volunteers.

Site Leads

Most site and cosite leads are based in whole health or pain management teams and are whole health coaches or peer support specialists. The site lead is responsible for standing up the program and documenting encounters, recruiting and supporting peer facilitators and participants, and overseeing the meeting. During meetings, site leads generally leave their cameras off and only speak when called into the group; the peer facilitators lead the meetings. The implementation support team recommends that site leads dedicate ≥ 4 hours per week to Vet-to-Vet; 2 hours for weekly group meetings and 2 hours for documentation (ie, entering notes into the participants’ electronic health records) and supporting peer facilitators and participants. Cosite lead responsibilities vary by location, with some sites having 2 leads that equally share duties and others having a primary lead and a colead available if the site lead is unable to attend a meeting.

Vet-to-Vet Peer Facilitators

Peer facilitators are the core of the program. They lead meetings from start to finish. Like participants, they also experience chronic pain and are volunteers. The implementation support team encourages sites to establish volunteer peer facilitators, rather than assigning peer support specialists to facilitate meetings. Veterans are eager to connect and give back to their communities, and the Vet-to-Vet peer facilitator role is an opportunity for those unable to work to connect with peers and add meaning to their lives. Even if a VHA employee is a veteran who has chronic pain, they are not eligible to serve as this could create a service provider/service recipient dynamic that is not in the spirit of mutual help.

Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators attend a virtual 3-day training held by the implementation support team prior to starting. These training sessions are available on a quarterly basis and facilitated by the Vet-to-Vet program manager and 2 current peer facilitators. Training content includes established whole health facilitator training materials and program-specific storytelling training materials. Once trained, peer facilitators attend storytelling practice sessions and collaborate with their site leads during weekly meetings.

Participants

Vet-to-Vet participants find the program through direct outreach from site leads, word of mouth, and referrals. The only criteria to join are that the individual is a veteran who experiences chronic pain and is enrolled in the VHA (site leads can assist with enrollment if needed). Participants are not required to have a diagnosis or engage in any other health care. There is no commitment and no end date. Some participants only come once; others have attended for > 3 years. This approach is intended to embrace the idea that the need for support ebbs and flows.

National Partners

The VHA Office of Rural Health provides technical support. The Center for Development and Civic Engagement onboards peer facilitators as VHA volunteers. The Office of Patient-Centered Care and Cultural Transformation provides national guidance and site-level collaboration. The VHA Pain Management, Opioid Safety, and Prescription Drug Monitoring Program supports site recruitment. In addition to the VHA partners, 4 veteran evaluation consultants who have experience with chronic pain but do not participate in Vet-to-Vet meetings provide advice on evaluation activities, such as question development and communication strategies.

Evaluation

This evaluation shares preliminary results from a pilot evaluation of the Rocky Mountain Regional VA Medical Center (RMRVAMC) Vet-to-Vet group. It is intended for program improvement, was deemed nonresearch by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board, and was structured using the RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance) framework.23 This evaluation focused on capturing measures related to reach and effectiveness, while a forthcoming evaluation includes elements of adoption, implementation, and maintenance.

In 2022, 16 Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators and participants completed surveys and interviews to share their experience. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded in ATLAS.ti. A priori codes were based on interview guide questions and emergent descriptive codes were used to identify specific topics which were categorized into RE-AIM domains, barriers, facilitators, what participants learned, how participants applied what they learned to their lives, and participant reported outcomes. This article contains high-level findings from the evaluation; more detailed results will be included in the ongoing evaluation.

Results

The RMRVAMC Vet-to-Vet group has met weekly since April 2022. Four Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators and 12 individuals participated in the pilot Vet-to-Vet group and evaluation. The mean age was 62 years, most were men, and half were married. Most participants lived in rural areas with a mean distance of 125 miles to the nearest VAMC. Many experienced multiple kinds of pain, with a mean 4.5 on a 10-point scale (bothered “a lot”). All participants reported that they experienced pain daily.

Participation in Vet-to-Vet meetings was high; 3 of 4 peer facilitators and 7 of 12 participants completed the first 6 months of the program. In interviews, participants described the positive impact of the program. They emphasized the importance of connecting with other veterans and helping one another, with one noting that opportunities to connect with other veterans “just drops off a lot” (peer facilitator 3) after leaving active duty.

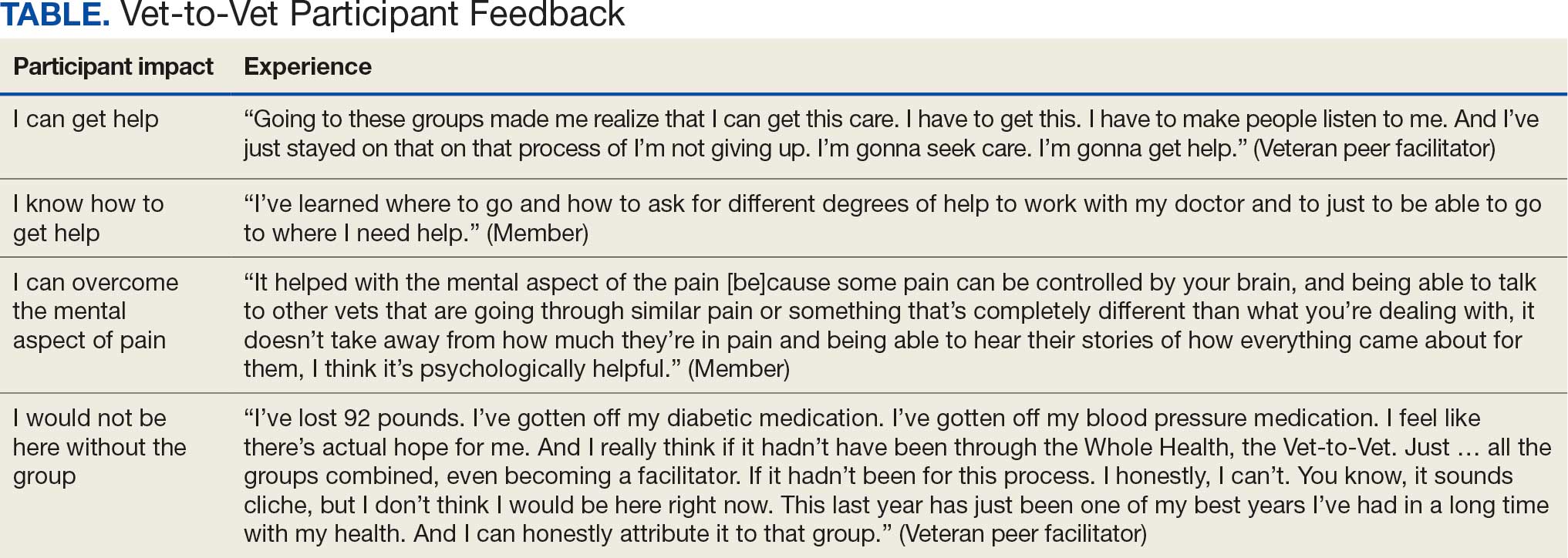

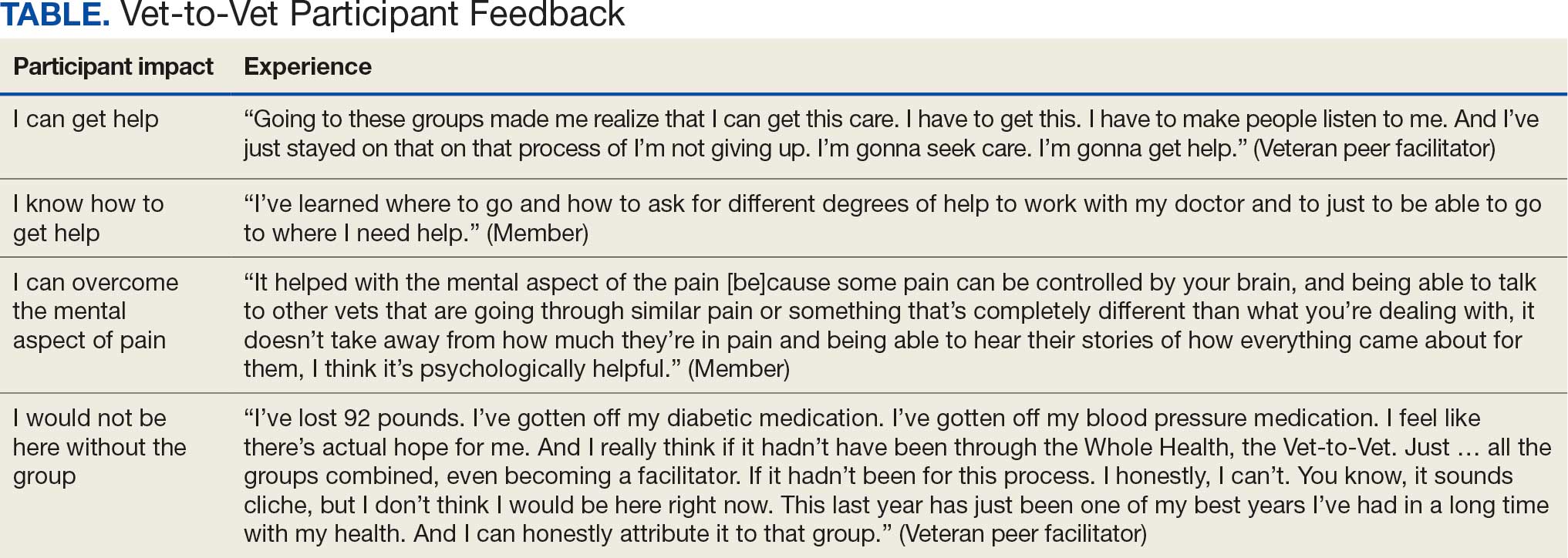

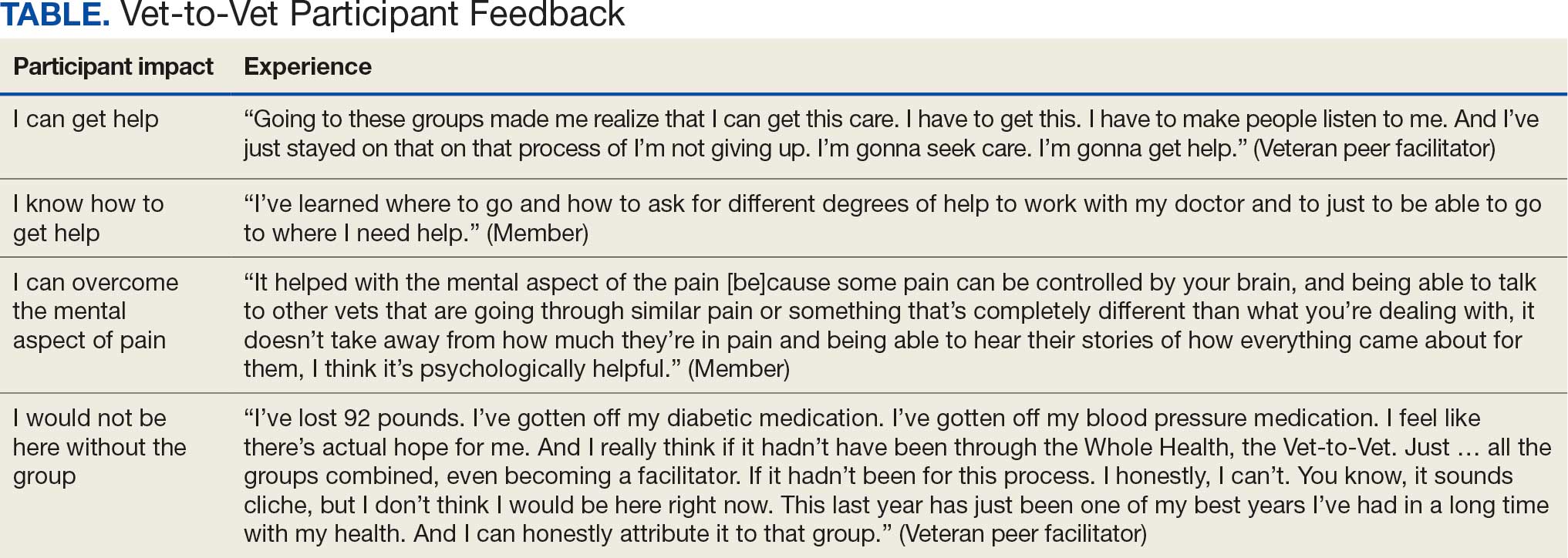

Some participants and Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators outlined the content of the sessions (eg, learning about how pain impacts the body and one’s family relationships) and shared the skills they learned (eg, goal setting, self-advocacy) (Table). Most spoke about learning from one another and the power of sharing stories with one peer facilitator sharing how they felt that witnessing another participant’s story “really shifted how I was thinking about things and how I perceived people” (peer facilitator 1).

Participants reported several ways the program impacted their lives, such as learning that they could get help, how to get help, and how to overcome the mental aspects of chronic pain. One veteran shared profound health impacts and attributed the Vet-to-Vet program to having one of the best years of their life. Even those who did not attend many meetings spoke of it positively and stated that it should continue so others could try (Table).

From January 2022 to September 2025, > 80 veterans attended ≥ 1 meeting at RMRVAMC; 29 attended ≥ 1 meeting in the last quarter. There were > 1400 Vet-to-Vet encounters at RMRVAMC, with a mean (SD) of 14.2 (19.2) and a median of 4.5 encounters per participant. Half of the veterans attend ≥ 5 meetings, and one-third attended ≥ 10 meetings.

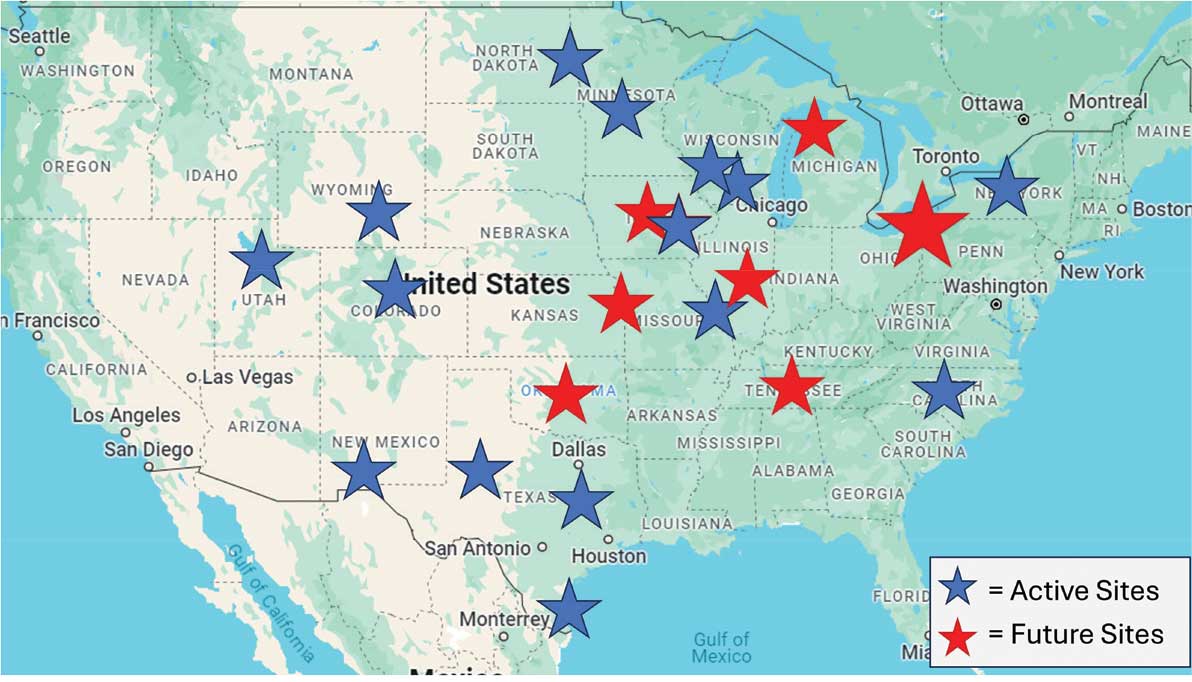

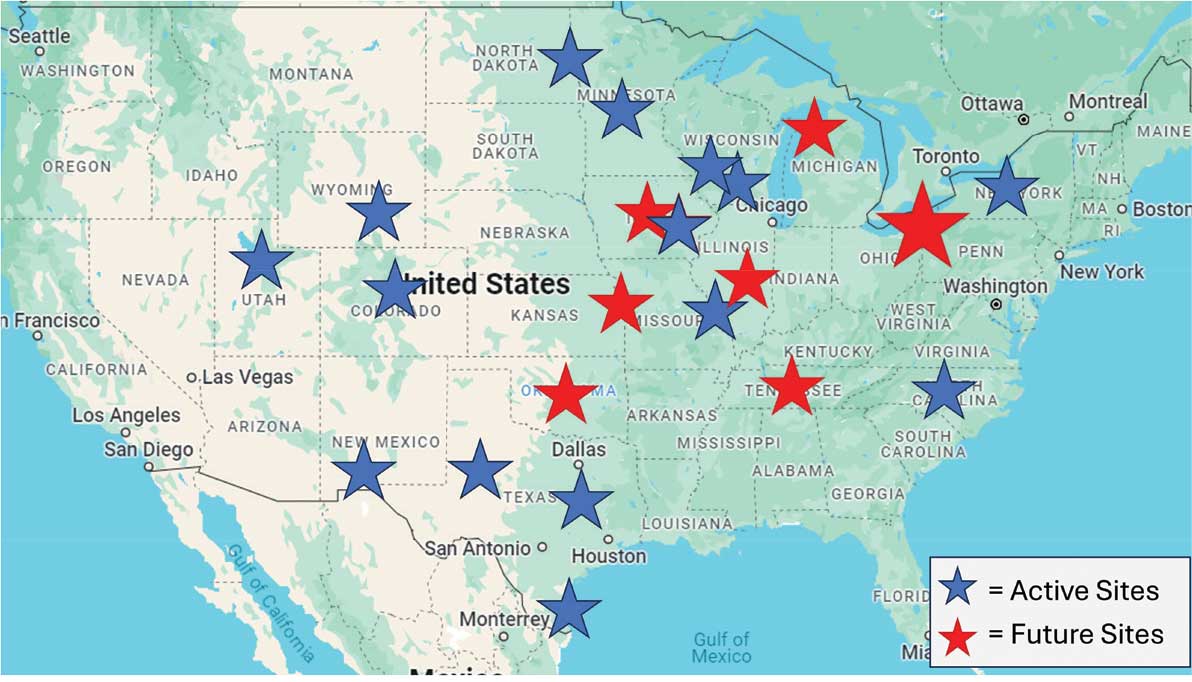

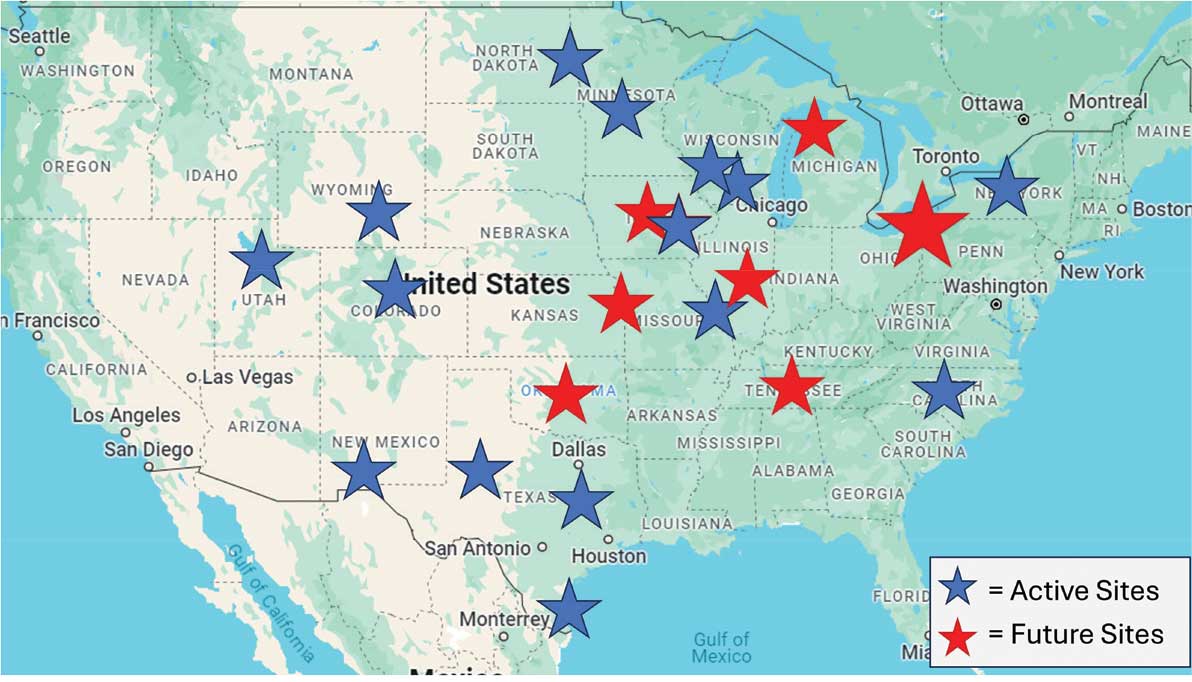

Since June 2023, 15 additional VHA facilities launched Vet-to-Vet programs. As of October 2025, > 350 veterans have participated in ≥ 1 Vet-to-Vet meeting, totaling > 4500 Vet-to-Vet encounters since the program’s inception (Figure 2).

Challenges

The RMRVAMC site and cosite leads are part of the national implementation team and dedicate substantial time to developing the program: 40 and 10 hours per week, respectively. Site leads at new locations do not receive funding for Vet-to-Vet activities and are recommended to dedicate only 4 hours per week to the program. Formally embedding Vet-to-Vet into the site leads’ roles is critical for sustainment.

The Vet-to-Vet model has changed. The initial Vet-to-Vet cohort included the 6-week Taking Charge of My Life and Health curriculum prior to moving to the mutual help format.24 While this curriculum still informs peer facilitator training, it is not used in new groups. It has anecdotally been reported that this change was positive, but the impact of this adaptation is unknown.

This evaluation cohort was small (16 participants) and initial patient reported and administrative outcomes were inconclusive. However, most veterans who stopped participating in Vet-to-Vet spoke fondly of their experiences with the program.

CONCLUSIONS

Vet-to-Vet is a promising new initiative to support self-management and social connection in chronic pain care. The program employs a mutual help approach and storytelling to empower veterans living with chronic pain. The effectiveness of these strategies will be evaluated, which will inform its continued growth. The program's current goals focus on sustainment at existing sites and expansion to new sites to reach more rural veterans across the VA enterprise. While Vet-to-Vet is designed to serve those who experience chronic pain, a partnership with the Office of Whole Health has established goals to begin expanding this model to other chronic conditions in 2026.