User login

Do PFAs Cause Kidney Cancer? VA to Investigate

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) will conduct a scientific assessment to find out in whether kidney cancer should be considered a presumptive service-connected condition for veterans exposed to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAs). This assessment is the first step in the VA presumptive condition investigative process, which could allow exposed veterans who were exposed to PFAs during their service to access more VA services.

A class of more than 12,000 chemicals, PFAs have been used in the military since the early 1970s in many items, including military-grade firefighting foam. Studies have already suggested links between the so-called forever chemicals and cancer, particularly kidney cancer.

The US Department of Defense (DoD) is assessing contamination at hundreds of sites, while the National Defense Authorization Act in Fiscal Year 2020 mandated that DoD stop using those foams starting in October and remove all stocks from active and former installations and equipment. That may not happen until next year, though, because the DoD has requested a waiver through October 2025 and may extend it through 2026.

When a condition is considered presumptive, eligible veterans do not need to prove their service caused their disease to receive benefits. As part of the Biden Administration’s efforts to expand benefits and services for toxin-exposed veterans and their families, the VA expedited health care and benefits eligibility under the PACT Act by several years—including extending presumptions for head cancer, neck cancer, gastrointestinal cancer, reproductive cancer, lymphoma, pancreatic cancer, kidney cancer, melanoma, and hypertension for Vietnam era veterans. The VA has also extended presumptions for > 300 new conditions, most recently for male breast cancer, urethral cancer, and cancer of the paraurethral glands.

Whether a condition is an established presumptive condition or not, the VA will consider claims on a case-by-case basis and can grant disability compensation benefits if sufficient evidence of service connection is found. “[M]ake no mistake: Veterans should not wait for the outcome of this review to apply for the benefits and care they deserve,” VA Secretary Denis McDonough said in a release. “If you’re a veteran and believe your military service has negatively impacted your health, we encourage you to apply for VA care and benefits today.”

The public has 30 days to comment on the proposed scientific assessment between PFAs exposure and kidney cancer via the Federal Register. The VA is set to host a listening session on Nov. 19, 2024, to allow individuals to share research and input. Interested individuals may register to participate. The public may also comment via either forum on other conditions that would benefit from review for potential service-connection.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) will conduct a scientific assessment to find out in whether kidney cancer should be considered a presumptive service-connected condition for veterans exposed to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAs). This assessment is the first step in the VA presumptive condition investigative process, which could allow exposed veterans who were exposed to PFAs during their service to access more VA services.

A class of more than 12,000 chemicals, PFAs have been used in the military since the early 1970s in many items, including military-grade firefighting foam. Studies have already suggested links between the so-called forever chemicals and cancer, particularly kidney cancer.

The US Department of Defense (DoD) is assessing contamination at hundreds of sites, while the National Defense Authorization Act in Fiscal Year 2020 mandated that DoD stop using those foams starting in October and remove all stocks from active and former installations and equipment. That may not happen until next year, though, because the DoD has requested a waiver through October 2025 and may extend it through 2026.

When a condition is considered presumptive, eligible veterans do not need to prove their service caused their disease to receive benefits. As part of the Biden Administration’s efforts to expand benefits and services for toxin-exposed veterans and their families, the VA expedited health care and benefits eligibility under the PACT Act by several years—including extending presumptions for head cancer, neck cancer, gastrointestinal cancer, reproductive cancer, lymphoma, pancreatic cancer, kidney cancer, melanoma, and hypertension for Vietnam era veterans. The VA has also extended presumptions for > 300 new conditions, most recently for male breast cancer, urethral cancer, and cancer of the paraurethral glands.

Whether a condition is an established presumptive condition or not, the VA will consider claims on a case-by-case basis and can grant disability compensation benefits if sufficient evidence of service connection is found. “[M]ake no mistake: Veterans should not wait for the outcome of this review to apply for the benefits and care they deserve,” VA Secretary Denis McDonough said in a release. “If you’re a veteran and believe your military service has negatively impacted your health, we encourage you to apply for VA care and benefits today.”

The public has 30 days to comment on the proposed scientific assessment between PFAs exposure and kidney cancer via the Federal Register. The VA is set to host a listening session on Nov. 19, 2024, to allow individuals to share research and input. Interested individuals may register to participate. The public may also comment via either forum on other conditions that would benefit from review for potential service-connection.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) will conduct a scientific assessment to find out in whether kidney cancer should be considered a presumptive service-connected condition for veterans exposed to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAs). This assessment is the first step in the VA presumptive condition investigative process, which could allow exposed veterans who were exposed to PFAs during their service to access more VA services.

A class of more than 12,000 chemicals, PFAs have been used in the military since the early 1970s in many items, including military-grade firefighting foam. Studies have already suggested links between the so-called forever chemicals and cancer, particularly kidney cancer.

The US Department of Defense (DoD) is assessing contamination at hundreds of sites, while the National Defense Authorization Act in Fiscal Year 2020 mandated that DoD stop using those foams starting in October and remove all stocks from active and former installations and equipment. That may not happen until next year, though, because the DoD has requested a waiver through October 2025 and may extend it through 2026.

When a condition is considered presumptive, eligible veterans do not need to prove their service caused their disease to receive benefits. As part of the Biden Administration’s efforts to expand benefits and services for toxin-exposed veterans and their families, the VA expedited health care and benefits eligibility under the PACT Act by several years—including extending presumptions for head cancer, neck cancer, gastrointestinal cancer, reproductive cancer, lymphoma, pancreatic cancer, kidney cancer, melanoma, and hypertension for Vietnam era veterans. The VA has also extended presumptions for > 300 new conditions, most recently for male breast cancer, urethral cancer, and cancer of the paraurethral glands.

Whether a condition is an established presumptive condition or not, the VA will consider claims on a case-by-case basis and can grant disability compensation benefits if sufficient evidence of service connection is found. “[M]ake no mistake: Veterans should not wait for the outcome of this review to apply for the benefits and care they deserve,” VA Secretary Denis McDonough said in a release. “If you’re a veteran and believe your military service has negatively impacted your health, we encourage you to apply for VA care and benefits today.”

The public has 30 days to comment on the proposed scientific assessment between PFAs exposure and kidney cancer via the Federal Register. The VA is set to host a listening session on Nov. 19, 2024, to allow individuals to share research and input. Interested individuals may register to participate. The public may also comment via either forum on other conditions that would benefit from review for potential service-connection.

Vancomycin AUC-Dosing Initiative at a Regional Antibiotic Stewardship Collaborative

Antimicrobial resistance is a global threat and burden to health care, with > 2.8 million antibiotic-resistant infections occurring annually in the United States.1 To combat this issue and improve patient care, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has implemented antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) across its health care systems. ASPs are multidisciplinary teams that promote evidence-based use of antimicrobials through activities supporting appropriate selection, dosing, route, and duration of antimicrobial therapy. ASP best practices are also included in the Joint Commission and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services accreditation standards.2

The foundational charge for VA facilities to develop and maintain ASPs was outlined in 2014 and updated in 2023 in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Directive 1031 on antimicrobial stewardship programs.2 This directive outlines specific requirements for all VA ASPs, including personnel, staffing levels, and the roles and responsibilities of all team members. VHA now requires that Veterans Integrated Services Networks (VISNs) establish robust ASP collaboratives. A VISN ASP collaborative consists of stewardship champions from each VA medical center in the VISN and is designed to support, develop, and enhance ASP programs across all facilities within that VISN.2 Some VISNs may lack an ASP collaborative altogether, and others with existing groups may seek ways to expand their collaboratives in line with the updated directive. Prior to VHA Directive 1031, the VA Sunshine Healthcare Network (VISN 8) established an ASP collaborative. This article describes the structure and activities of the VISN 8 ASP collaborative and highlights a recent VISN 8 quality assurance initiative related to vancomycin area under the curve (AUC) dosing that illustrates how ASP collaboratives can enhance stewardship and clinical care across broad geographic areas.

VISN 8 ASP

The VHA, the largest integrated US health care system, is divided into 18 VISNs that provide regional systems of care to enhance access and meet the local health care needs of veterans.3 VISN 8 serves > 1.5 million veterans across 165,759 km2 in Florida, South Georgia, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands.4 The network is composed of 7 health systems with 8 medical centers and > 60 outpatient clinics. These facilities provide comprehensive acute, primary, and specialty care, as well as mental health and extended care services in inpatient, outpatient, nursing home, and home care settings.4

The 2023 VHA Directive 1031 update recognizes the importance of VISN-level coordination of ASP activities to enhance the standardization of care and build partnerships in stewardship across all levels of care. The VISN 8 ASP collaborative workgroup (ASPWG) was established in 2015. Consistent with Directive 1031, the ASPWG is guided by clinician and pharmacist VISN leads. These leads serve as subject matter experts, facilitate access to resources, establish VISN-level consensus, and enhance communication among local ASP champions at medical centers within the VISN. All 7 health systems include = 1 ASP champion (clinician or pharmacist) in the ASPWG. Ad hoc members, whose routine duties are not solely focused on antimicrobial stewardship, contribute to specific stewardship projects as needed. For example, the ASPWG has included internal medicine, emergency department, community living center pharmacists, representatives from pharmacy administration, and trainees (pharmacy students and residents, and infectious diseases fellows) in antimicrobial stewardship initiatives. The inclusion of non-ASP champions is not discussed in VHA Directive 1031. However, these members have made valuable contributions to the ASPWG.

The ASPWG meets monthly. Agendas and priorities are developed by the VISN pharmacist and health care practitioner (HCP) leads. Monthly discussions may include but are not limited to a review of national formulary decisions, VISN goals and metrics, infectious diseases hot topics, pharmacoeconomic initiatives, strong practice presentations, regulatory and accreditation preparation, preparation of tracking reports, as well as the development of both patient-level and HCPlevel tools, resources, and education materials. This forum facilitates collaborative learning: members process and synthesize information, share and reframe ideas, and listen to other viewpoints to gain a complete understanding as a group.5 For example, ASPWG members have leaned on each other to prepare for Joint Commission accreditation surveys and strengthen the VISN 8 COVID-19 program through the rollout of vaccines and treatments. Other collaborative projects completed over the past few years included a penicillin allergy testing initiative and anti-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and pseudomonal medication use evaluations. This team-centric problem-solving approach is highly effective while also fostering professional and social relationships. However, collaboratives could be perceived to have drawbacks. There may be opportunity costs if ASP time is allocated for issues that have already been addressed locally or concerns that standardization might hinder rapid adoption of practices at individual sites. Therefore, participation in each distinct group initiative is optional. This allows sites to choose projects related to their high priority areas and maintain bandwidth to implement practices not yet adopted by the larger group.

The ASPWG tracks metrics related to antimicrobial use with quarterly data presented by the VISN pharmacist lead. Both inpatient and outpatient metrics are evaluated, such as days of therapy per 1000 days and outpatient antibiotic prescriptions per 1000 unique patients. Facilities are benchmarked against their own historical data and other VISN sites, as well as other VISNs across the country. When outliers are identified, facilities are encouraged to conduct local projects to identify reasons for different antimicrobial use patterns and subsequent initiatives to optimize antimicrobial use. Benchmarking against VISN facilities can be useful since VISN facilities may be more similar than facilities in different geographic regions. Each year, the ASPWG reviews the current metrics, makes adjustments to address VISN priorities, and votes for approval of the metrics that will be tracked in the coming year.

Participation in an ASP collaborative streamlines the rollout of ASP and quality improvement initiatives across multiple sites, allowing ASPs to impact a greater number of veterans and evaluate initiatives on a larger scale. In 2019, with the anticipation of revised vancomycin dosing and monitoring guidelines, our ASPWG began to strategize the transition to AUC-based vancomycin monitoring.6 This multisite initiative showcases the strengths of implementing and evaluating practice changes as part of an ASP collaborative.

Vancomycin Dosing

The antibiotic vancomycin is used primarily for the treatment of MRSA infections.6 The 2020 consensus guidelines for vancomycin therapeutic monitoring recommend using the AUC to minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) ratio as the pharmacodynamic target for serious MRSA infections, with an AUC/MIC goal of 400 to 600 mcg*h/mL.6 Prior guidelines recommended using vancomycin trough concentrations of 15 to 20 mcg/mL as a surrogate for this AUC target. However, subsequent studies have shown that trough-based dosing is associated with higher vancomycin exposures, supratherapeutic AUCs, and increased risk of vancomycin-associated acute kidney injury (AKI).7,8 Therefore, more direct AUC estimation is now recommended.6 The preferred approach for AUC calculations is through Bayesian modeling. Due to limited resources and software availability, many facilities use an alternative method involving 2 postdistributive serum vancomycin concentrations and first-order pharmacokinetic equations. This approach can optimize vancomycin dosing but is more mathematically and logistically challenging. Transitioning from troughto AUC-based vancomycin monitoring requires careful planning and comprehensive staff education.

In 2019, the VISN 8 ASPWG created a comprehensive vancomycin AUC toolkit to facilitate implementation. Components included a pharmacokinetic management policy and procedure, a vancomycin dosing guide, a progress note template, educational materials specific to pharmacy, nursing, laboratory, and medical services, a pharmacist competency examination, and a vancomycin AUC calculator (eAppendix). Each component was developed by a subgroup with the understanding that sites could incorporate variations based on local practices and needs.

The vancomycin AUC calculator was developed to be user-friendly and included safety validation protocols to prevent the entry of erroneous data (eg, unrealistic patient weight or laboratory values). The calculator allowed users to copy data into the electronic health record to avoid manual transcription errors and improve operational efficiency. It offered suggested volume of distribution estimates and 2 methods to estimate elimination constant (Ke ) depending on the patient’s weight.9,10 Creatinine clearance could be estimated using serum creatinine or cystatin C and considered amputation history. The default AUC goal in the calculator was 400 to 550 mcg*h/mL. This range was chosen based on consensus guidelines, data suggesting increased risk of AKI with AUCs > 515 mcg*h/mL, and the preference for conservative empiric dosing in the generally older VA population.11 The calculator suggested loading doses of about 25 mg/kg with a 2500 mg limit. VHA facilities could make limited modifications to the calculator based on local policies and procedures (eg, adjusting default infusion times or a dosing intervals).

The VISN 8 Pharmacy Pharmacokinetic Dosing Manual was developed as a comprehensive document to guide pharmacy staff with dosing vancomycin across diverse patient populations. This document included recommendations for renal function assessment, patient-specific considerations when choosing an empiric vancomycin dose, methods of ordering vancomycin peak, trough, and surveillance levels, dose determination based on 2 levels, and other clinical insights or frequently asked questions.

ASPWG members presented an accredited continuing education webinar for pharmacists, which reviewed the rationale for AUC-targeted dosing, changes to the current pharmacokinetic dosing program, case-based scenarios across various patient populations, and potential challenges associated with vancomycin AUC-based dosing. A recording of the live training was also made available. A vancomycin AUC dosing competency test was developed with 11 basic pharmacokinetic and case-based questions and comprehensive explanations provided for each answer.

VHA facilities implemented AUC dosing in a staggered manner, allowing for lessons learned at earlier adopters to be addressed proactively at later sites. The dosing calculator and education documents were updated iteratively as opportunities for improvement were discovered. ASPWG members held local office hours to address questions or concerns from staff at their facilities. Sharing standardized materials across the VISN reduced individual site workload and complications in rolling out this complex new process.

VISN-WIDE QUALITY ASSURANCE

At the time of project conception, 4 of 7 VISN 8 health systems had transitioned to AUC-based dosing. A quality assurance protocol to compare patient outcomes before and after changing to AUC dosing was developed. Each site followed local protocols for project approval and data were deidentified, collected, and aggregated for analysis.

The primary objectives were to compare the incidence of AKI and persistent bacteremia and assess rates of AUC target attainment (400-600 mcg*h/mL) in the AUC-based and trough-based dosing groups.6 Data for both groups included anthropomorphic measurements, serum creatinine, amputation status, vancomycin dosing, and infection characteristics. The X2 test was used for categorical data and the t test was used for continuous data. A 2-tailed α of 0.05 was used to determine significance. Each site sequentially reviewed all patients receiving ≥ 48 hours of intravenous vancomycin over a 3-month period and contributed up to 50 patients for each group. Due to staggered implementation, the study periods for sites spanned 2018 to 2023. A minimum 6-month washout period was observed between the trough and AUC groups at each site. Patients were excluded if pregnant, receiving renal replacement therapy, or presenting with AKI at the time of vancomycin initiation.

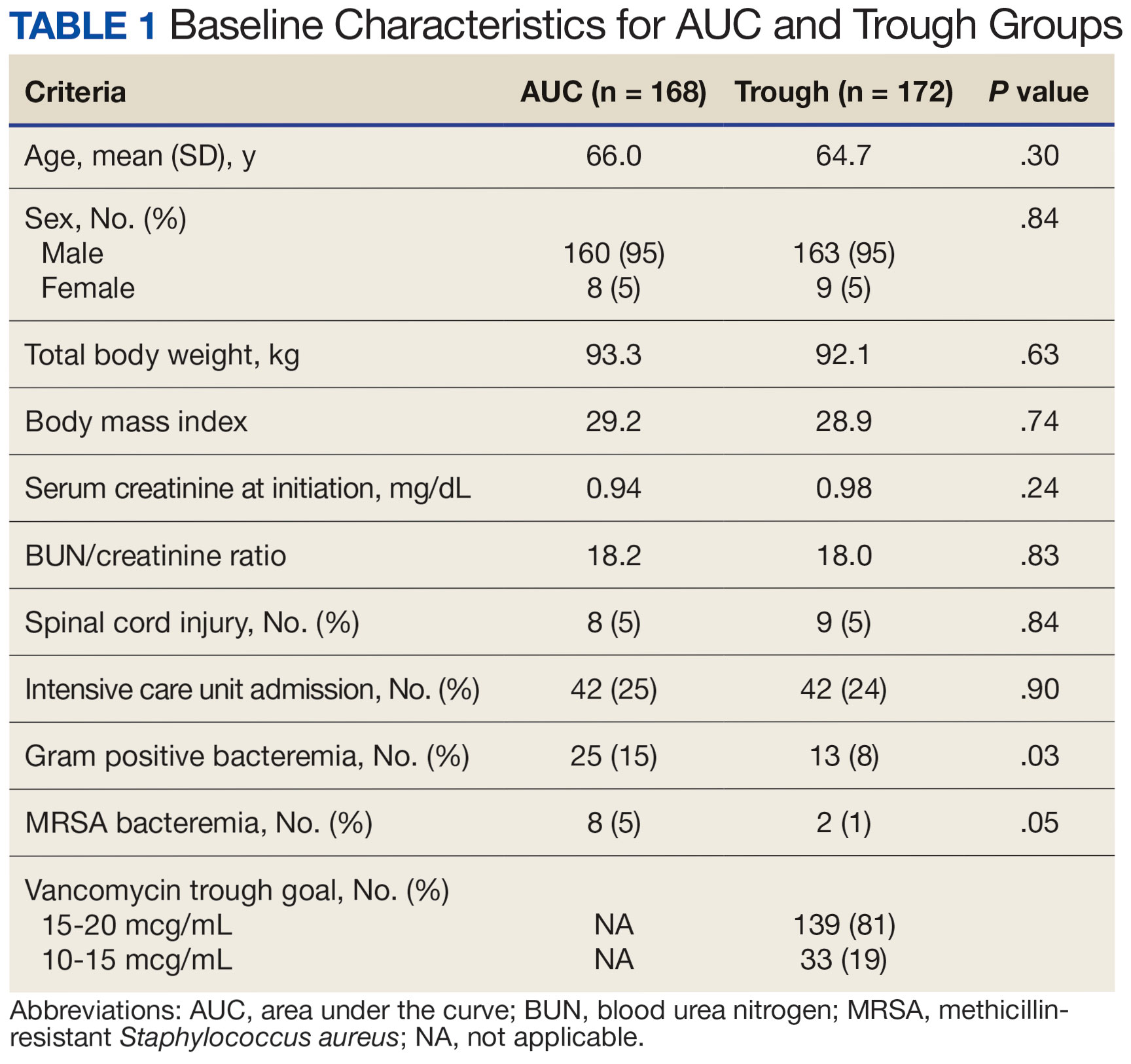

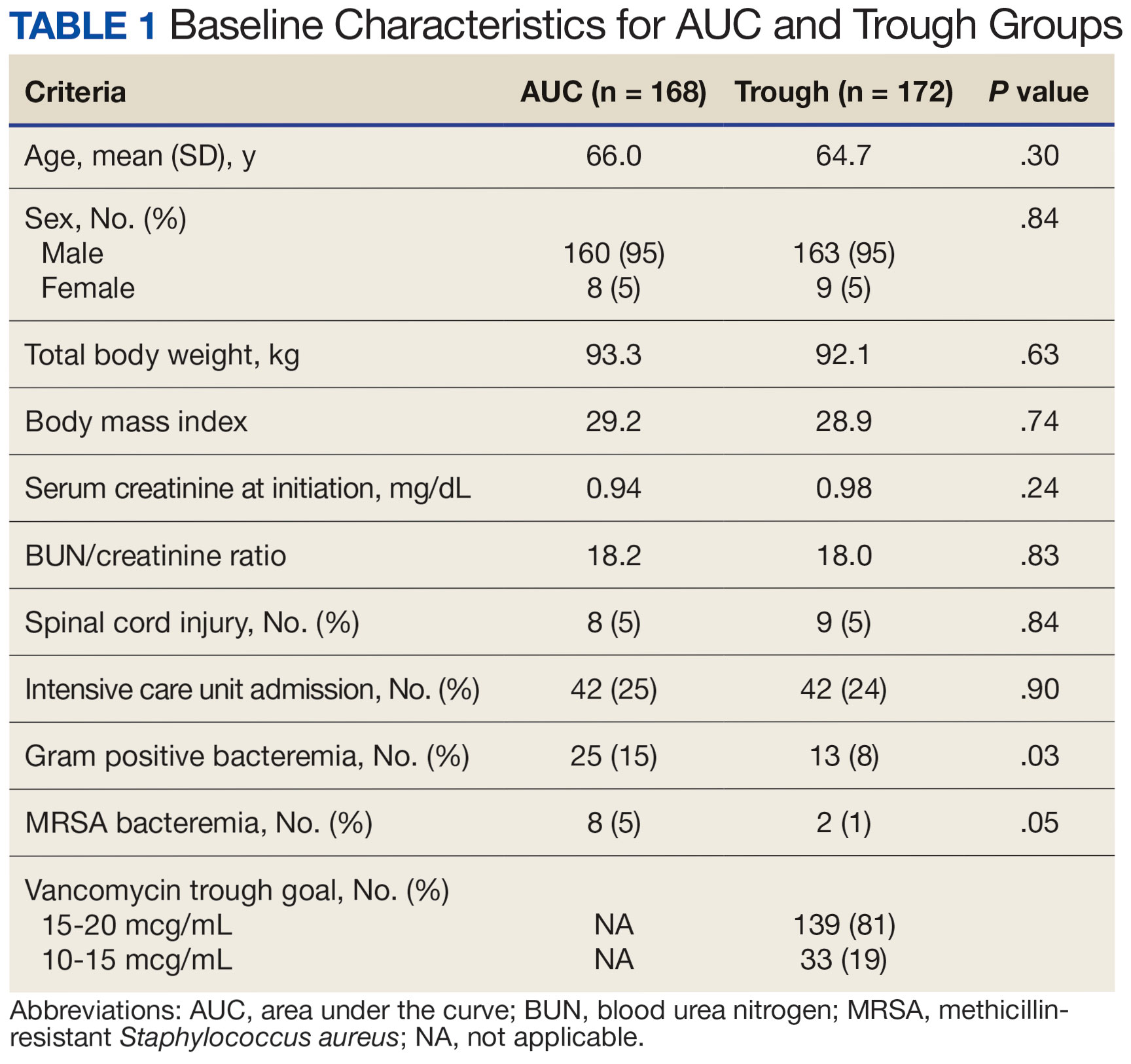

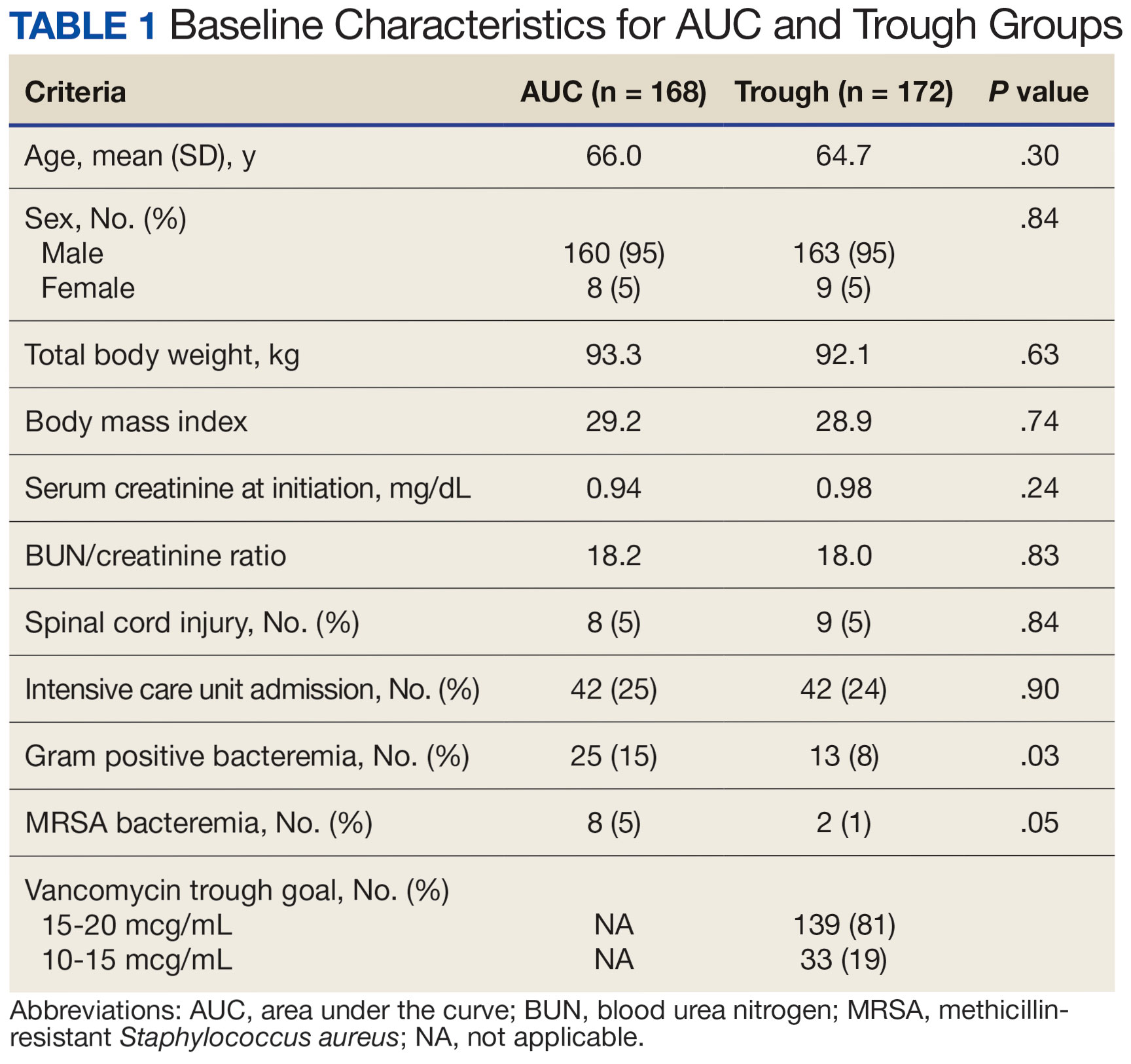

There were 168 patients in the AUC group and 172 patients in the trough group (Table 1). The rate of AUC target attainment with the initial dosing regimen varied across sites from 18% to 69% (mean, 48%). Total daily vancomycin exposure was lower in the AUC group compared with the trough group (2402 mg vs 2605 mg, respectively), with AUC-dosed patients being less likely to experience troughs level ≥ 15 or 20 mcg/mL (Table 2). There was a statistically significant lower rate of AKI in the AUC group: 2.4% in the AUC group (range, 2%-3%) vs 10.4% (range 7%-12%) in the trough group (P = .002). Rates of AKI were comparable to those observed in previous interventions.6 There was no statistical difference in length of stay, time to blood culture clearance, or rate of persistent bacteremia in the 2 groups, but these assessments were limited by sample size.

We did not anticipate such variability in initial target attainment across sites. The multisite quality assurance design allowed for qualitative evaluation of variability in dosing practices, which likely arose from sites and individual pharmacists having some flexibility in adjusting dosing tool parameters. Further analysis revealed that the facility with low initial target attainment was not routinely utilizing vancomycin loading doses. Sites routinely use robust loading doses achieved earlier and more consistent target attainment. Some sites used a narrower AUC target range in certain clinical scenarios (eg, > 500 mcg*h/mL for septic patients and < 500 mcg*h/mL for patients with less severe infections) rather than the 400 to 550 mcg*h/mL range for all patients. Sites targeting broader AUC ranges for all patients had higher rates of target attainment. Reviewing differences among sites allowed the ASPWG to identify best practices to optimize future care.

CONCLUSIONS

VHA ASPs must meet the standards outlined in VHA Directive 1031, including the new requirement for each VISN to develop an ASP collaborative. The VISN 8 ASPWG demonstrates how ASP champions can collaborate to solve common issues, complete tasks, explore new infectious diseases concepts, and impact large veteran populations. Furthermore, ASP collaboratives can harness their collective size to complete robust quality assurance evaluations that might otherwise be underpowered if completed at a single center. A limitation of the collaborative model is that a site with a robust ASP may already have specific practices in place. Expanding the ASP collaborative model further highlights the VHA role as a nationwide leader in ASP best practices.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2019. Updated December 2019. Accessed September 10, 2024. https:// www.cdc.gov/antimicrobial-resistance/media/pdfs/2019-ar-threats-report-508.pdf

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Antimicrobial stewardship programs. Updated September 22, 2023. Accessed September 13, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=11458

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veteran Health Administration. Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs). Accessed September 13, 2024. https://www.va.gov/HEALTH/visns.asp

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Health Administration, Veterans Integrated Service Networks, VISN 08. Updated September 10, 2024. Accessed September 13, 2024. https://department.va.gov/integrated-service-networks/visn-08/

- Andreev I. What is collaborative learning? Theory, examples of activities. Valamis. Updated July 10, 2024. Accessed September 10, 2024. https://www.valamis.com/hub/collaborative-learning

- Rybak MJ, Le J, Lodise TP, et al. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin for serious methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus infections: a revised consensus guideline and review by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77(11):835-864. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxaa036

- Finch NA, Zasowski EJ, Murray KP, et al. A quasi-experiment to study the impact of vancomycin area under the concentration-time curve-guided dosing on vancomycinassociated nephrotoxicity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61(12):e01293-17. doi:10.1128/AAC.01293-17

- Zasowski EJ, Murray KP, Trinh TD, et al. Identification of vancomycin exposure-toxicity thresholds in hospitalized patients receiving intravenous vancomycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;62(1):e01684-17. doi:10.1128/AAC.01684-17

- Matzke GR, Kovarik JM, Rybak MJ, Boike SC. Evaluation of the vancomycin-clearance: creatinine-clearance relationship for predicting vancomycin dosage. Clin Pharm. 1985;4(3):311-315.

- Crass RL, Dunn R, Hong J, Krop LC, Pai MP. Dosing vancomycin in the super obese: less is more. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(11):3081-3086. doi:10.1093/jac/dky310

- Lodise TP, Rosenkranz SL, Finnemeyer M, et al. The emperor’s new clothes: prospective observational evaluation of the association between initial vancomycIn exposure and failure rates among adult hospitalized patients with methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections (PROVIDE). Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70(8):1536-1545. doi:10.1093/cid/ciz460

Antimicrobial resistance is a global threat and burden to health care, with > 2.8 million antibiotic-resistant infections occurring annually in the United States.1 To combat this issue and improve patient care, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has implemented antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) across its health care systems. ASPs are multidisciplinary teams that promote evidence-based use of antimicrobials through activities supporting appropriate selection, dosing, route, and duration of antimicrobial therapy. ASP best practices are also included in the Joint Commission and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services accreditation standards.2

The foundational charge for VA facilities to develop and maintain ASPs was outlined in 2014 and updated in 2023 in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Directive 1031 on antimicrobial stewardship programs.2 This directive outlines specific requirements for all VA ASPs, including personnel, staffing levels, and the roles and responsibilities of all team members. VHA now requires that Veterans Integrated Services Networks (VISNs) establish robust ASP collaboratives. A VISN ASP collaborative consists of stewardship champions from each VA medical center in the VISN and is designed to support, develop, and enhance ASP programs across all facilities within that VISN.2 Some VISNs may lack an ASP collaborative altogether, and others with existing groups may seek ways to expand their collaboratives in line with the updated directive. Prior to VHA Directive 1031, the VA Sunshine Healthcare Network (VISN 8) established an ASP collaborative. This article describes the structure and activities of the VISN 8 ASP collaborative and highlights a recent VISN 8 quality assurance initiative related to vancomycin area under the curve (AUC) dosing that illustrates how ASP collaboratives can enhance stewardship and clinical care across broad geographic areas.

VISN 8 ASP

The VHA, the largest integrated US health care system, is divided into 18 VISNs that provide regional systems of care to enhance access and meet the local health care needs of veterans.3 VISN 8 serves > 1.5 million veterans across 165,759 km2 in Florida, South Georgia, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands.4 The network is composed of 7 health systems with 8 medical centers and > 60 outpatient clinics. These facilities provide comprehensive acute, primary, and specialty care, as well as mental health and extended care services in inpatient, outpatient, nursing home, and home care settings.4

The 2023 VHA Directive 1031 update recognizes the importance of VISN-level coordination of ASP activities to enhance the standardization of care and build partnerships in stewardship across all levels of care. The VISN 8 ASP collaborative workgroup (ASPWG) was established in 2015. Consistent with Directive 1031, the ASPWG is guided by clinician and pharmacist VISN leads. These leads serve as subject matter experts, facilitate access to resources, establish VISN-level consensus, and enhance communication among local ASP champions at medical centers within the VISN. All 7 health systems include = 1 ASP champion (clinician or pharmacist) in the ASPWG. Ad hoc members, whose routine duties are not solely focused on antimicrobial stewardship, contribute to specific stewardship projects as needed. For example, the ASPWG has included internal medicine, emergency department, community living center pharmacists, representatives from pharmacy administration, and trainees (pharmacy students and residents, and infectious diseases fellows) in antimicrobial stewardship initiatives. The inclusion of non-ASP champions is not discussed in VHA Directive 1031. However, these members have made valuable contributions to the ASPWG.

The ASPWG meets monthly. Agendas and priorities are developed by the VISN pharmacist and health care practitioner (HCP) leads. Monthly discussions may include but are not limited to a review of national formulary decisions, VISN goals and metrics, infectious diseases hot topics, pharmacoeconomic initiatives, strong practice presentations, regulatory and accreditation preparation, preparation of tracking reports, as well as the development of both patient-level and HCPlevel tools, resources, and education materials. This forum facilitates collaborative learning: members process and synthesize information, share and reframe ideas, and listen to other viewpoints to gain a complete understanding as a group.5 For example, ASPWG members have leaned on each other to prepare for Joint Commission accreditation surveys and strengthen the VISN 8 COVID-19 program through the rollout of vaccines and treatments. Other collaborative projects completed over the past few years included a penicillin allergy testing initiative and anti-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and pseudomonal medication use evaluations. This team-centric problem-solving approach is highly effective while also fostering professional and social relationships. However, collaboratives could be perceived to have drawbacks. There may be opportunity costs if ASP time is allocated for issues that have already been addressed locally or concerns that standardization might hinder rapid adoption of practices at individual sites. Therefore, participation in each distinct group initiative is optional. This allows sites to choose projects related to their high priority areas and maintain bandwidth to implement practices not yet adopted by the larger group.

The ASPWG tracks metrics related to antimicrobial use with quarterly data presented by the VISN pharmacist lead. Both inpatient and outpatient metrics are evaluated, such as days of therapy per 1000 days and outpatient antibiotic prescriptions per 1000 unique patients. Facilities are benchmarked against their own historical data and other VISN sites, as well as other VISNs across the country. When outliers are identified, facilities are encouraged to conduct local projects to identify reasons for different antimicrobial use patterns and subsequent initiatives to optimize antimicrobial use. Benchmarking against VISN facilities can be useful since VISN facilities may be more similar than facilities in different geographic regions. Each year, the ASPWG reviews the current metrics, makes adjustments to address VISN priorities, and votes for approval of the metrics that will be tracked in the coming year.

Participation in an ASP collaborative streamlines the rollout of ASP and quality improvement initiatives across multiple sites, allowing ASPs to impact a greater number of veterans and evaluate initiatives on a larger scale. In 2019, with the anticipation of revised vancomycin dosing and monitoring guidelines, our ASPWG began to strategize the transition to AUC-based vancomycin monitoring.6 This multisite initiative showcases the strengths of implementing and evaluating practice changes as part of an ASP collaborative.

Vancomycin Dosing

The antibiotic vancomycin is used primarily for the treatment of MRSA infections.6 The 2020 consensus guidelines for vancomycin therapeutic monitoring recommend using the AUC to minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) ratio as the pharmacodynamic target for serious MRSA infections, with an AUC/MIC goal of 400 to 600 mcg*h/mL.6 Prior guidelines recommended using vancomycin trough concentrations of 15 to 20 mcg/mL as a surrogate for this AUC target. However, subsequent studies have shown that trough-based dosing is associated with higher vancomycin exposures, supratherapeutic AUCs, and increased risk of vancomycin-associated acute kidney injury (AKI).7,8 Therefore, more direct AUC estimation is now recommended.6 The preferred approach for AUC calculations is through Bayesian modeling. Due to limited resources and software availability, many facilities use an alternative method involving 2 postdistributive serum vancomycin concentrations and first-order pharmacokinetic equations. This approach can optimize vancomycin dosing but is more mathematically and logistically challenging. Transitioning from troughto AUC-based vancomycin monitoring requires careful planning and comprehensive staff education.

In 2019, the VISN 8 ASPWG created a comprehensive vancomycin AUC toolkit to facilitate implementation. Components included a pharmacokinetic management policy and procedure, a vancomycin dosing guide, a progress note template, educational materials specific to pharmacy, nursing, laboratory, and medical services, a pharmacist competency examination, and a vancomycin AUC calculator (eAppendix). Each component was developed by a subgroup with the understanding that sites could incorporate variations based on local practices and needs.

The vancomycin AUC calculator was developed to be user-friendly and included safety validation protocols to prevent the entry of erroneous data (eg, unrealistic patient weight or laboratory values). The calculator allowed users to copy data into the electronic health record to avoid manual transcription errors and improve operational efficiency. It offered suggested volume of distribution estimates and 2 methods to estimate elimination constant (Ke ) depending on the patient’s weight.9,10 Creatinine clearance could be estimated using serum creatinine or cystatin C and considered amputation history. The default AUC goal in the calculator was 400 to 550 mcg*h/mL. This range was chosen based on consensus guidelines, data suggesting increased risk of AKI with AUCs > 515 mcg*h/mL, and the preference for conservative empiric dosing in the generally older VA population.11 The calculator suggested loading doses of about 25 mg/kg with a 2500 mg limit. VHA facilities could make limited modifications to the calculator based on local policies and procedures (eg, adjusting default infusion times or a dosing intervals).

The VISN 8 Pharmacy Pharmacokinetic Dosing Manual was developed as a comprehensive document to guide pharmacy staff with dosing vancomycin across diverse patient populations. This document included recommendations for renal function assessment, patient-specific considerations when choosing an empiric vancomycin dose, methods of ordering vancomycin peak, trough, and surveillance levels, dose determination based on 2 levels, and other clinical insights or frequently asked questions.

ASPWG members presented an accredited continuing education webinar for pharmacists, which reviewed the rationale for AUC-targeted dosing, changes to the current pharmacokinetic dosing program, case-based scenarios across various patient populations, and potential challenges associated with vancomycin AUC-based dosing. A recording of the live training was also made available. A vancomycin AUC dosing competency test was developed with 11 basic pharmacokinetic and case-based questions and comprehensive explanations provided for each answer.

VHA facilities implemented AUC dosing in a staggered manner, allowing for lessons learned at earlier adopters to be addressed proactively at later sites. The dosing calculator and education documents were updated iteratively as opportunities for improvement were discovered. ASPWG members held local office hours to address questions or concerns from staff at their facilities. Sharing standardized materials across the VISN reduced individual site workload and complications in rolling out this complex new process.

VISN-WIDE QUALITY ASSURANCE

At the time of project conception, 4 of 7 VISN 8 health systems had transitioned to AUC-based dosing. A quality assurance protocol to compare patient outcomes before and after changing to AUC dosing was developed. Each site followed local protocols for project approval and data were deidentified, collected, and aggregated for analysis.

The primary objectives were to compare the incidence of AKI and persistent bacteremia and assess rates of AUC target attainment (400-600 mcg*h/mL) in the AUC-based and trough-based dosing groups.6 Data for both groups included anthropomorphic measurements, serum creatinine, amputation status, vancomycin dosing, and infection characteristics. The X2 test was used for categorical data and the t test was used for continuous data. A 2-tailed α of 0.05 was used to determine significance. Each site sequentially reviewed all patients receiving ≥ 48 hours of intravenous vancomycin over a 3-month period and contributed up to 50 patients for each group. Due to staggered implementation, the study periods for sites spanned 2018 to 2023. A minimum 6-month washout period was observed between the trough and AUC groups at each site. Patients were excluded if pregnant, receiving renal replacement therapy, or presenting with AKI at the time of vancomycin initiation.

There were 168 patients in the AUC group and 172 patients in the trough group (Table 1). The rate of AUC target attainment with the initial dosing regimen varied across sites from 18% to 69% (mean, 48%). Total daily vancomycin exposure was lower in the AUC group compared with the trough group (2402 mg vs 2605 mg, respectively), with AUC-dosed patients being less likely to experience troughs level ≥ 15 or 20 mcg/mL (Table 2). There was a statistically significant lower rate of AKI in the AUC group: 2.4% in the AUC group (range, 2%-3%) vs 10.4% (range 7%-12%) in the trough group (P = .002). Rates of AKI were comparable to those observed in previous interventions.6 There was no statistical difference in length of stay, time to blood culture clearance, or rate of persistent bacteremia in the 2 groups, but these assessments were limited by sample size.

We did not anticipate such variability in initial target attainment across sites. The multisite quality assurance design allowed for qualitative evaluation of variability in dosing practices, which likely arose from sites and individual pharmacists having some flexibility in adjusting dosing tool parameters. Further analysis revealed that the facility with low initial target attainment was not routinely utilizing vancomycin loading doses. Sites routinely use robust loading doses achieved earlier and more consistent target attainment. Some sites used a narrower AUC target range in certain clinical scenarios (eg, > 500 mcg*h/mL for septic patients and < 500 mcg*h/mL for patients with less severe infections) rather than the 400 to 550 mcg*h/mL range for all patients. Sites targeting broader AUC ranges for all patients had higher rates of target attainment. Reviewing differences among sites allowed the ASPWG to identify best practices to optimize future care.

CONCLUSIONS

VHA ASPs must meet the standards outlined in VHA Directive 1031, including the new requirement for each VISN to develop an ASP collaborative. The VISN 8 ASPWG demonstrates how ASP champions can collaborate to solve common issues, complete tasks, explore new infectious diseases concepts, and impact large veteran populations. Furthermore, ASP collaboratives can harness their collective size to complete robust quality assurance evaluations that might otherwise be underpowered if completed at a single center. A limitation of the collaborative model is that a site with a robust ASP may already have specific practices in place. Expanding the ASP collaborative model further highlights the VHA role as a nationwide leader in ASP best practices.

Antimicrobial resistance is a global threat and burden to health care, with > 2.8 million antibiotic-resistant infections occurring annually in the United States.1 To combat this issue and improve patient care, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has implemented antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) across its health care systems. ASPs are multidisciplinary teams that promote evidence-based use of antimicrobials through activities supporting appropriate selection, dosing, route, and duration of antimicrobial therapy. ASP best practices are also included in the Joint Commission and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services accreditation standards.2

The foundational charge for VA facilities to develop and maintain ASPs was outlined in 2014 and updated in 2023 in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Directive 1031 on antimicrobial stewardship programs.2 This directive outlines specific requirements for all VA ASPs, including personnel, staffing levels, and the roles and responsibilities of all team members. VHA now requires that Veterans Integrated Services Networks (VISNs) establish robust ASP collaboratives. A VISN ASP collaborative consists of stewardship champions from each VA medical center in the VISN and is designed to support, develop, and enhance ASP programs across all facilities within that VISN.2 Some VISNs may lack an ASP collaborative altogether, and others with existing groups may seek ways to expand their collaboratives in line with the updated directive. Prior to VHA Directive 1031, the VA Sunshine Healthcare Network (VISN 8) established an ASP collaborative. This article describes the structure and activities of the VISN 8 ASP collaborative and highlights a recent VISN 8 quality assurance initiative related to vancomycin area under the curve (AUC) dosing that illustrates how ASP collaboratives can enhance stewardship and clinical care across broad geographic areas.

VISN 8 ASP

The VHA, the largest integrated US health care system, is divided into 18 VISNs that provide regional systems of care to enhance access and meet the local health care needs of veterans.3 VISN 8 serves > 1.5 million veterans across 165,759 km2 in Florida, South Georgia, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands.4 The network is composed of 7 health systems with 8 medical centers and > 60 outpatient clinics. These facilities provide comprehensive acute, primary, and specialty care, as well as mental health and extended care services in inpatient, outpatient, nursing home, and home care settings.4

The 2023 VHA Directive 1031 update recognizes the importance of VISN-level coordination of ASP activities to enhance the standardization of care and build partnerships in stewardship across all levels of care. The VISN 8 ASP collaborative workgroup (ASPWG) was established in 2015. Consistent with Directive 1031, the ASPWG is guided by clinician and pharmacist VISN leads. These leads serve as subject matter experts, facilitate access to resources, establish VISN-level consensus, and enhance communication among local ASP champions at medical centers within the VISN. All 7 health systems include = 1 ASP champion (clinician or pharmacist) in the ASPWG. Ad hoc members, whose routine duties are not solely focused on antimicrobial stewardship, contribute to specific stewardship projects as needed. For example, the ASPWG has included internal medicine, emergency department, community living center pharmacists, representatives from pharmacy administration, and trainees (pharmacy students and residents, and infectious diseases fellows) in antimicrobial stewardship initiatives. The inclusion of non-ASP champions is not discussed in VHA Directive 1031. However, these members have made valuable contributions to the ASPWG.

The ASPWG meets monthly. Agendas and priorities are developed by the VISN pharmacist and health care practitioner (HCP) leads. Monthly discussions may include but are not limited to a review of national formulary decisions, VISN goals and metrics, infectious diseases hot topics, pharmacoeconomic initiatives, strong practice presentations, regulatory and accreditation preparation, preparation of tracking reports, as well as the development of both patient-level and HCPlevel tools, resources, and education materials. This forum facilitates collaborative learning: members process and synthesize information, share and reframe ideas, and listen to other viewpoints to gain a complete understanding as a group.5 For example, ASPWG members have leaned on each other to prepare for Joint Commission accreditation surveys and strengthen the VISN 8 COVID-19 program through the rollout of vaccines and treatments. Other collaborative projects completed over the past few years included a penicillin allergy testing initiative and anti-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and pseudomonal medication use evaluations. This team-centric problem-solving approach is highly effective while also fostering professional and social relationships. However, collaboratives could be perceived to have drawbacks. There may be opportunity costs if ASP time is allocated for issues that have already been addressed locally or concerns that standardization might hinder rapid adoption of practices at individual sites. Therefore, participation in each distinct group initiative is optional. This allows sites to choose projects related to their high priority areas and maintain bandwidth to implement practices not yet adopted by the larger group.

The ASPWG tracks metrics related to antimicrobial use with quarterly data presented by the VISN pharmacist lead. Both inpatient and outpatient metrics are evaluated, such as days of therapy per 1000 days and outpatient antibiotic prescriptions per 1000 unique patients. Facilities are benchmarked against their own historical data and other VISN sites, as well as other VISNs across the country. When outliers are identified, facilities are encouraged to conduct local projects to identify reasons for different antimicrobial use patterns and subsequent initiatives to optimize antimicrobial use. Benchmarking against VISN facilities can be useful since VISN facilities may be more similar than facilities in different geographic regions. Each year, the ASPWG reviews the current metrics, makes adjustments to address VISN priorities, and votes for approval of the metrics that will be tracked in the coming year.

Participation in an ASP collaborative streamlines the rollout of ASP and quality improvement initiatives across multiple sites, allowing ASPs to impact a greater number of veterans and evaluate initiatives on a larger scale. In 2019, with the anticipation of revised vancomycin dosing and monitoring guidelines, our ASPWG began to strategize the transition to AUC-based vancomycin monitoring.6 This multisite initiative showcases the strengths of implementing and evaluating practice changes as part of an ASP collaborative.

Vancomycin Dosing

The antibiotic vancomycin is used primarily for the treatment of MRSA infections.6 The 2020 consensus guidelines for vancomycin therapeutic monitoring recommend using the AUC to minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) ratio as the pharmacodynamic target for serious MRSA infections, with an AUC/MIC goal of 400 to 600 mcg*h/mL.6 Prior guidelines recommended using vancomycin trough concentrations of 15 to 20 mcg/mL as a surrogate for this AUC target. However, subsequent studies have shown that trough-based dosing is associated with higher vancomycin exposures, supratherapeutic AUCs, and increased risk of vancomycin-associated acute kidney injury (AKI).7,8 Therefore, more direct AUC estimation is now recommended.6 The preferred approach for AUC calculations is through Bayesian modeling. Due to limited resources and software availability, many facilities use an alternative method involving 2 postdistributive serum vancomycin concentrations and first-order pharmacokinetic equations. This approach can optimize vancomycin dosing but is more mathematically and logistically challenging. Transitioning from troughto AUC-based vancomycin monitoring requires careful planning and comprehensive staff education.

In 2019, the VISN 8 ASPWG created a comprehensive vancomycin AUC toolkit to facilitate implementation. Components included a pharmacokinetic management policy and procedure, a vancomycin dosing guide, a progress note template, educational materials specific to pharmacy, nursing, laboratory, and medical services, a pharmacist competency examination, and a vancomycin AUC calculator (eAppendix). Each component was developed by a subgroup with the understanding that sites could incorporate variations based on local practices and needs.

The vancomycin AUC calculator was developed to be user-friendly and included safety validation protocols to prevent the entry of erroneous data (eg, unrealistic patient weight or laboratory values). The calculator allowed users to copy data into the electronic health record to avoid manual transcription errors and improve operational efficiency. It offered suggested volume of distribution estimates and 2 methods to estimate elimination constant (Ke ) depending on the patient’s weight.9,10 Creatinine clearance could be estimated using serum creatinine or cystatin C and considered amputation history. The default AUC goal in the calculator was 400 to 550 mcg*h/mL. This range was chosen based on consensus guidelines, data suggesting increased risk of AKI with AUCs > 515 mcg*h/mL, and the preference for conservative empiric dosing in the generally older VA population.11 The calculator suggested loading doses of about 25 mg/kg with a 2500 mg limit. VHA facilities could make limited modifications to the calculator based on local policies and procedures (eg, adjusting default infusion times or a dosing intervals).

The VISN 8 Pharmacy Pharmacokinetic Dosing Manual was developed as a comprehensive document to guide pharmacy staff with dosing vancomycin across diverse patient populations. This document included recommendations for renal function assessment, patient-specific considerations when choosing an empiric vancomycin dose, methods of ordering vancomycin peak, trough, and surveillance levels, dose determination based on 2 levels, and other clinical insights or frequently asked questions.

ASPWG members presented an accredited continuing education webinar for pharmacists, which reviewed the rationale for AUC-targeted dosing, changes to the current pharmacokinetic dosing program, case-based scenarios across various patient populations, and potential challenges associated with vancomycin AUC-based dosing. A recording of the live training was also made available. A vancomycin AUC dosing competency test was developed with 11 basic pharmacokinetic and case-based questions and comprehensive explanations provided for each answer.

VHA facilities implemented AUC dosing in a staggered manner, allowing for lessons learned at earlier adopters to be addressed proactively at later sites. The dosing calculator and education documents were updated iteratively as opportunities for improvement were discovered. ASPWG members held local office hours to address questions or concerns from staff at their facilities. Sharing standardized materials across the VISN reduced individual site workload and complications in rolling out this complex new process.

VISN-WIDE QUALITY ASSURANCE

At the time of project conception, 4 of 7 VISN 8 health systems had transitioned to AUC-based dosing. A quality assurance protocol to compare patient outcomes before and after changing to AUC dosing was developed. Each site followed local protocols for project approval and data were deidentified, collected, and aggregated for analysis.

The primary objectives were to compare the incidence of AKI and persistent bacteremia and assess rates of AUC target attainment (400-600 mcg*h/mL) in the AUC-based and trough-based dosing groups.6 Data for both groups included anthropomorphic measurements, serum creatinine, amputation status, vancomycin dosing, and infection characteristics. The X2 test was used for categorical data and the t test was used for continuous data. A 2-tailed α of 0.05 was used to determine significance. Each site sequentially reviewed all patients receiving ≥ 48 hours of intravenous vancomycin over a 3-month period and contributed up to 50 patients for each group. Due to staggered implementation, the study periods for sites spanned 2018 to 2023. A minimum 6-month washout period was observed between the trough and AUC groups at each site. Patients were excluded if pregnant, receiving renal replacement therapy, or presenting with AKI at the time of vancomycin initiation.

There were 168 patients in the AUC group and 172 patients in the trough group (Table 1). The rate of AUC target attainment with the initial dosing regimen varied across sites from 18% to 69% (mean, 48%). Total daily vancomycin exposure was lower in the AUC group compared with the trough group (2402 mg vs 2605 mg, respectively), with AUC-dosed patients being less likely to experience troughs level ≥ 15 or 20 mcg/mL (Table 2). There was a statistically significant lower rate of AKI in the AUC group: 2.4% in the AUC group (range, 2%-3%) vs 10.4% (range 7%-12%) in the trough group (P = .002). Rates of AKI were comparable to those observed in previous interventions.6 There was no statistical difference in length of stay, time to blood culture clearance, or rate of persistent bacteremia in the 2 groups, but these assessments were limited by sample size.

We did not anticipate such variability in initial target attainment across sites. The multisite quality assurance design allowed for qualitative evaluation of variability in dosing practices, which likely arose from sites and individual pharmacists having some flexibility in adjusting dosing tool parameters. Further analysis revealed that the facility with low initial target attainment was not routinely utilizing vancomycin loading doses. Sites routinely use robust loading doses achieved earlier and more consistent target attainment. Some sites used a narrower AUC target range in certain clinical scenarios (eg, > 500 mcg*h/mL for septic patients and < 500 mcg*h/mL for patients with less severe infections) rather than the 400 to 550 mcg*h/mL range for all patients. Sites targeting broader AUC ranges for all patients had higher rates of target attainment. Reviewing differences among sites allowed the ASPWG to identify best practices to optimize future care.

CONCLUSIONS

VHA ASPs must meet the standards outlined in VHA Directive 1031, including the new requirement for each VISN to develop an ASP collaborative. The VISN 8 ASPWG demonstrates how ASP champions can collaborate to solve common issues, complete tasks, explore new infectious diseases concepts, and impact large veteran populations. Furthermore, ASP collaboratives can harness their collective size to complete robust quality assurance evaluations that might otherwise be underpowered if completed at a single center. A limitation of the collaborative model is that a site with a robust ASP may already have specific practices in place. Expanding the ASP collaborative model further highlights the VHA role as a nationwide leader in ASP best practices.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2019. Updated December 2019. Accessed September 10, 2024. https:// www.cdc.gov/antimicrobial-resistance/media/pdfs/2019-ar-threats-report-508.pdf

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Antimicrobial stewardship programs. Updated September 22, 2023. Accessed September 13, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=11458

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veteran Health Administration. Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs). Accessed September 13, 2024. https://www.va.gov/HEALTH/visns.asp

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Health Administration, Veterans Integrated Service Networks, VISN 08. Updated September 10, 2024. Accessed September 13, 2024. https://department.va.gov/integrated-service-networks/visn-08/

- Andreev I. What is collaborative learning? Theory, examples of activities. Valamis. Updated July 10, 2024. Accessed September 10, 2024. https://www.valamis.com/hub/collaborative-learning

- Rybak MJ, Le J, Lodise TP, et al. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin for serious methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus infections: a revised consensus guideline and review by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77(11):835-864. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxaa036

- Finch NA, Zasowski EJ, Murray KP, et al. A quasi-experiment to study the impact of vancomycin area under the concentration-time curve-guided dosing on vancomycinassociated nephrotoxicity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61(12):e01293-17. doi:10.1128/AAC.01293-17

- Zasowski EJ, Murray KP, Trinh TD, et al. Identification of vancomycin exposure-toxicity thresholds in hospitalized patients receiving intravenous vancomycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;62(1):e01684-17. doi:10.1128/AAC.01684-17

- Matzke GR, Kovarik JM, Rybak MJ, Boike SC. Evaluation of the vancomycin-clearance: creatinine-clearance relationship for predicting vancomycin dosage. Clin Pharm. 1985;4(3):311-315.

- Crass RL, Dunn R, Hong J, Krop LC, Pai MP. Dosing vancomycin in the super obese: less is more. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(11):3081-3086. doi:10.1093/jac/dky310

- Lodise TP, Rosenkranz SL, Finnemeyer M, et al. The emperor’s new clothes: prospective observational evaluation of the association between initial vancomycIn exposure and failure rates among adult hospitalized patients with methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections (PROVIDE). Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70(8):1536-1545. doi:10.1093/cid/ciz460

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2019. Updated December 2019. Accessed September 10, 2024. https:// www.cdc.gov/antimicrobial-resistance/media/pdfs/2019-ar-threats-report-508.pdf

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Antimicrobial stewardship programs. Updated September 22, 2023. Accessed September 13, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=11458

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veteran Health Administration. Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs). Accessed September 13, 2024. https://www.va.gov/HEALTH/visns.asp

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Health Administration, Veterans Integrated Service Networks, VISN 08. Updated September 10, 2024. Accessed September 13, 2024. https://department.va.gov/integrated-service-networks/visn-08/

- Andreev I. What is collaborative learning? Theory, examples of activities. Valamis. Updated July 10, 2024. Accessed September 10, 2024. https://www.valamis.com/hub/collaborative-learning

- Rybak MJ, Le J, Lodise TP, et al. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin for serious methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus infections: a revised consensus guideline and review by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77(11):835-864. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxaa036

- Finch NA, Zasowski EJ, Murray KP, et al. A quasi-experiment to study the impact of vancomycin area under the concentration-time curve-guided dosing on vancomycinassociated nephrotoxicity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61(12):e01293-17. doi:10.1128/AAC.01293-17

- Zasowski EJ, Murray KP, Trinh TD, et al. Identification of vancomycin exposure-toxicity thresholds in hospitalized patients receiving intravenous vancomycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;62(1):e01684-17. doi:10.1128/AAC.01684-17

- Matzke GR, Kovarik JM, Rybak MJ, Boike SC. Evaluation of the vancomycin-clearance: creatinine-clearance relationship for predicting vancomycin dosage. Clin Pharm. 1985;4(3):311-315.

- Crass RL, Dunn R, Hong J, Krop LC, Pai MP. Dosing vancomycin in the super obese: less is more. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(11):3081-3086. doi:10.1093/jac/dky310

- Lodise TP, Rosenkranz SL, Finnemeyer M, et al. The emperor’s new clothes: prospective observational evaluation of the association between initial vancomycIn exposure and failure rates among adult hospitalized patients with methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections (PROVIDE). Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70(8):1536-1545. doi:10.1093/cid/ciz460

Age-Friendly Health Systems Transformation: A Whole Person Approach to Support the Well-Being of Older Adults

The COVID-19 pandemic established a new normal for health care delivery, with leaders rethinking core practices to survive and thrive in a changing environment and improve the health and well-being of patients. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is embracing a shift in focus from “what is the matter” to “what really matters” to address pre- and postpandemic challenges through a whole health approach.1 Initially conceptualized by the VHA in 2011, whole health “is an approach to health care that empowers and equips people to take charge of their health and well-being so that they can live their life to the fullest.”1 Whole health integrates evidence-based complementary and integrative health (CIH) therapies to manage pain; this includes acupuncture, meditation, tai chi, yoga, massage therapy, guided imagery, biofeedback, and clinical hypnosis.1 The VHA now recognizes well-being as a core value, helping clinicians respond to emerging challenges related to the social determinants of health (eg, access to health care, physical activity, and healthy foods) and guiding health care decision making.1,2

Well-being through empowerment—elements of whole health and Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS)—encourages health care institutions to work with employees, patients, and other stakeholders to address global challenges, clinician burnout, and social issues faced by their communities. This approach focuses on life’s purpose and meaning for individuals and inspires leaders to engage with patients, staff, and communities in new, impactful ways by focusing on wellbeing and wholeness rather than illness and disease. Having a higher sense of purpose is associated with lower all-cause mortality, reduced risk of specific diseases, better health behaviors, greater use of preventive services, and fewer hospital days of care.3

This article describes how AFHS supports the well-being of older adults and aligns with the whole health model of care. It also outlines the VHA investment to transform health care to be more person-centered by documenting what matters in the electronic health record (EHR).

AGE-FRIENDLY CARE

Given that nearly half of veterans enrolled in the VHA are aged ≥ 65 years, there is an increased need to identify models of care to support this aging population.4 This is especially critical because older veterans often have multiple chronic conditions and complex care needs that benefit from a whole person approach. The AFHS movement aims to provide evidence-based care aligned with what matters to older adults and provides a mechanism for transforming care to meet the needs of older veterans. This includes addressing age-related health concerns while promoting optimal health outcomes and quality of life. AFHS follows the 4Ms framework: what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility.5 The 4Ms serve as a guide for the health care of older adults in any setting, where each “M” is assessed and acted on to support what matters.5 Since 2020, > 390 teams have developed a plan to implement the 4Ms at 156 VHA facilities, demonstrating the VHA commitment to transforming health care for veterans.6

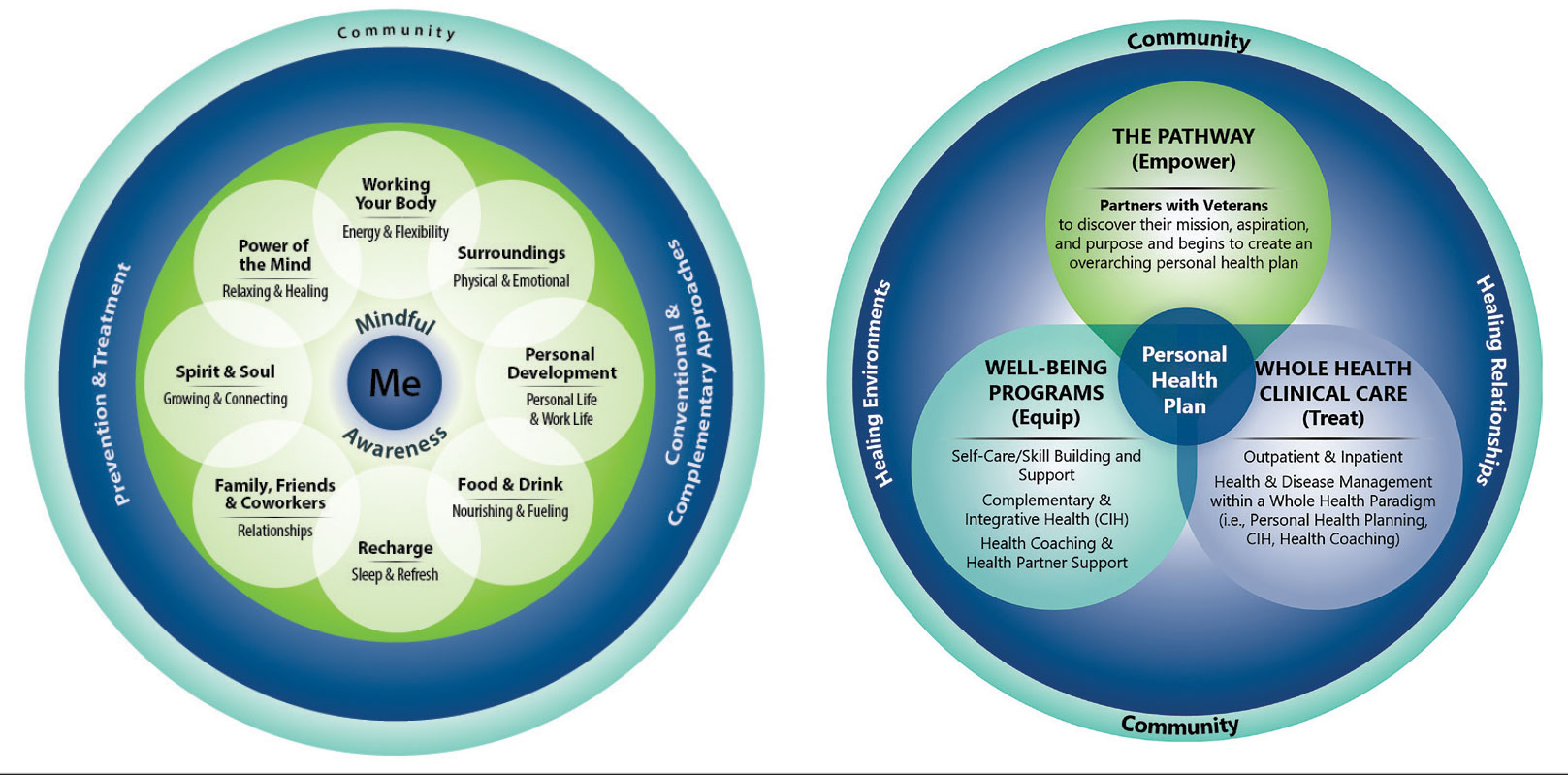

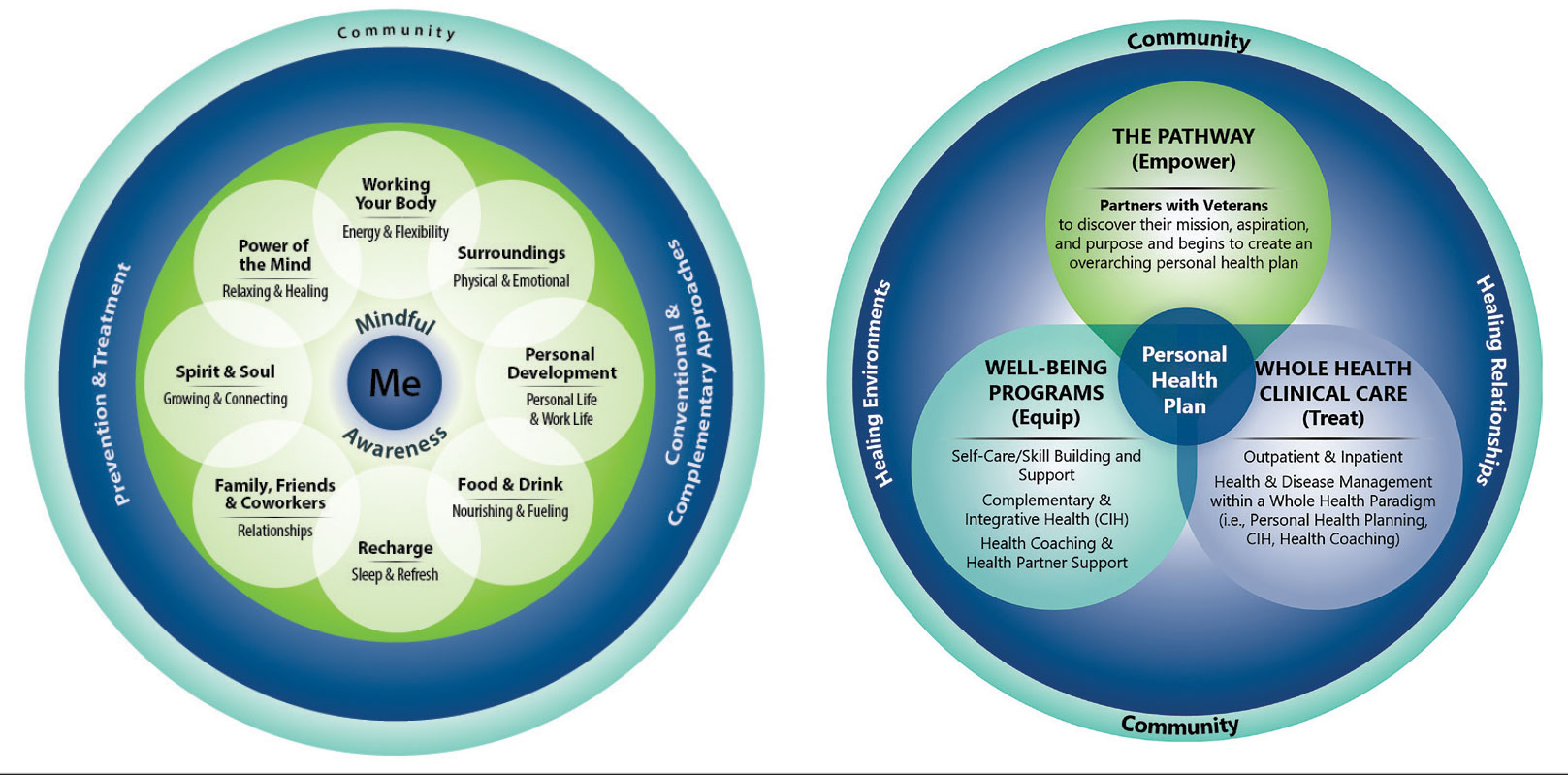

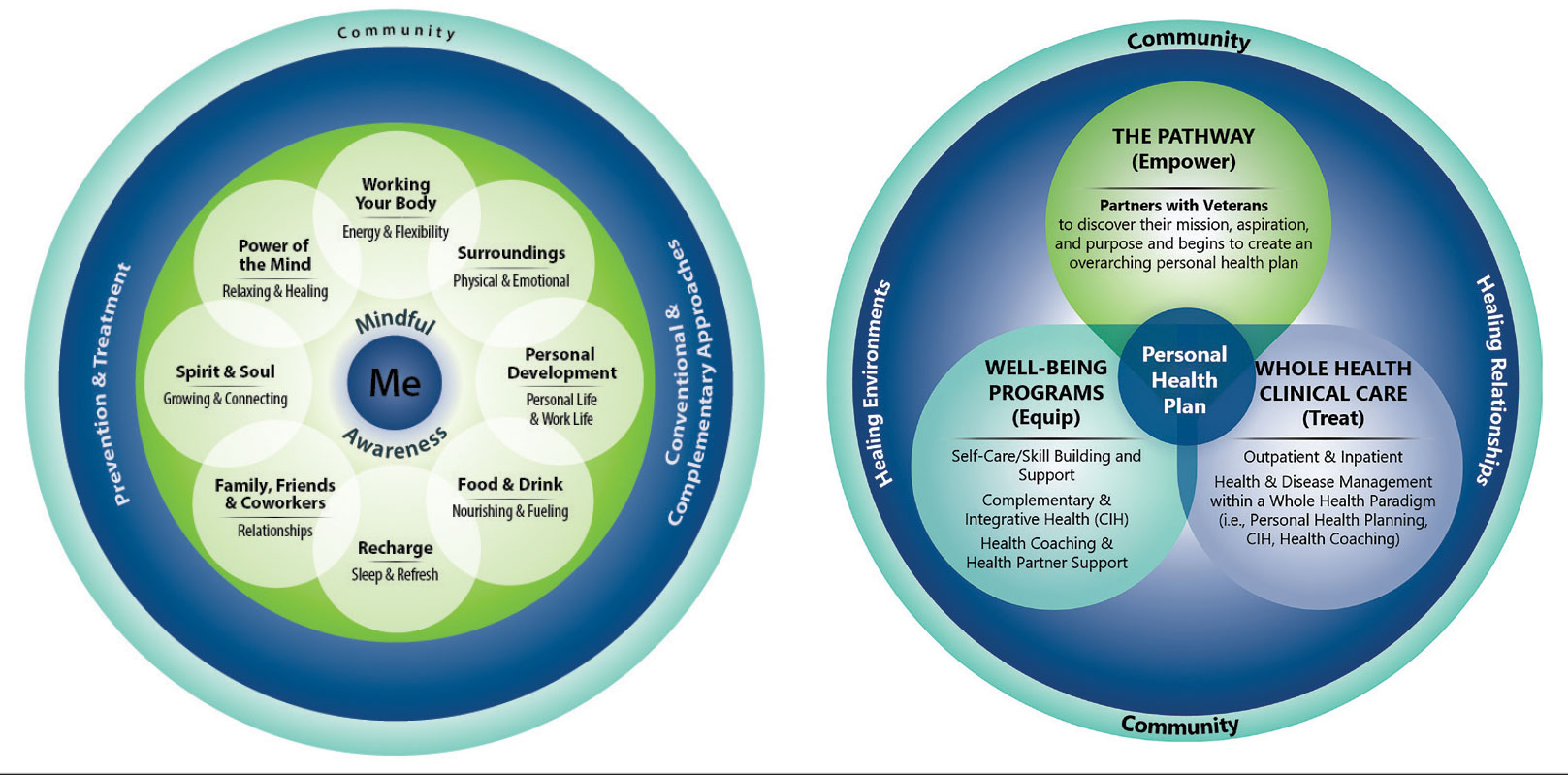

When VHA teams join the AFHS movement, they may also engage older veterans in a whole health system (WHS) (Figure). While AFHS is designed to improve care for patients aged ≥ 65 years, it also complements whole health, a person-centered approach available to all veterans enrolled in the VHA. Through the WHS and AFHS, veterans are empowered and equipped to take charge of their health and well-being through conversations about their unique goals, preferences, and health priorities.4 Clinicians are challenged to assess what matters by asking questions like, “What brings you joy?” and, “How can we help you meet your health goals?”1,5 These questions shift the conversation from disease-based treatment and enable clinicians to better understand the veteran as a person.1,5

For whole health and AFHS, conversations about what matters are anchored in the veteran’s goals and preferences, especially those facing a significant health change (ie, a new diagnosis or treatment decision).5,7 Together, the veteran’s goals and priorities serve as the foundation for developing person-centered care plans that often go beyond conventional medical treatments to address the physical, mental, emotional, and social aspects of health.

SYSTEM-WIDE DIRECTIVE

The WHS enhances AFHS discussions about what matters to veterans by adding a system-level lens for conceptualizing health care delivery by leveraging the 3 components of WHS: the “pathway,” well-being programs, and whole health clinical care.

The Pathway

Discovering what matters, or the veteran’s “mission, aspiration, and purpose,” begins with the WHS pathway. When stepping into the pathway, veterans begin completing a personal health inventory, or “walking the circle of health,” which encourages self-reflection that focuses on components of their life that can influence health and well-being.1,8 The circle of health offers a visual representation of the 4 most important aspects of health and well-being: First, “Me” at the center as an individual who is the expert on their life, values, goals, and priorities. Only the individual can know what really matters through mindful awareness and what works for their life. Second, self-care consists of 8 areas that impact health and wellbeing: working your body; surroundings; personal development; food and drink; recharge; family, friends, and coworkers; spirit and soul; and power of the mind. Third, professional care consists of prevention, conventional care, and complementary care. Finally, the community that supports the individual.

Well-Being Programs

VHA provides WHS programs that support veterans in building self-care skills and improving their quality of life, often through integrative care clinics that offer coaching and CIH therapies. For example, a veteran who prioritizes mobility when seeking care at an integrative care clinic will not only receive conventional medical treatment for their physical symptoms but may also be offered CIH therapies depending on their goals. The veteran may set a daily mobility goal with their care team that supports what matters, incorporating CIH approaches, such as yoga and tai chi into the care plan.5 These holistic approaches for moving the body can help alleviate physical symptoms, reduce stress, improve mindful awareness, and provide opportunities for self-discovery and growth, thus promote overall well-being

Whole Health Clinical Care

AFHS and the 4Ms embody the clinical care component of the WHS. Because what matters is the driver of the 4Ms, every action taken by the care team supports wellbeing and quality of life by promoting independence, connection, and support, and addressing external factors, such as social determinants of health. At a minimum, well-being includes “functioning well: the experience of positive emotions such as happiness and contentment as well as the development of one’s potential, having some control over one’s life, having a sense of purpose, and experiencing positive relationships.”9 From a system perspective, the VHA has begun to normalize focusing on what matters to veterans, using an interprofessional approach, one of the first steps to implementing AFHS.

As the programs expand, AFHS teams can learn from whole health well-being programs and increase the capacity for self-care in older veterans. Learning about the key elements included in the circle of health helps clinicians understand each veteran’s perceived strengths and weaknesses to support their self-care. From there, teams can act on the 4Ms and connect older veterans with the most appropriate programs and services at their facility, ensuring continuum of care.

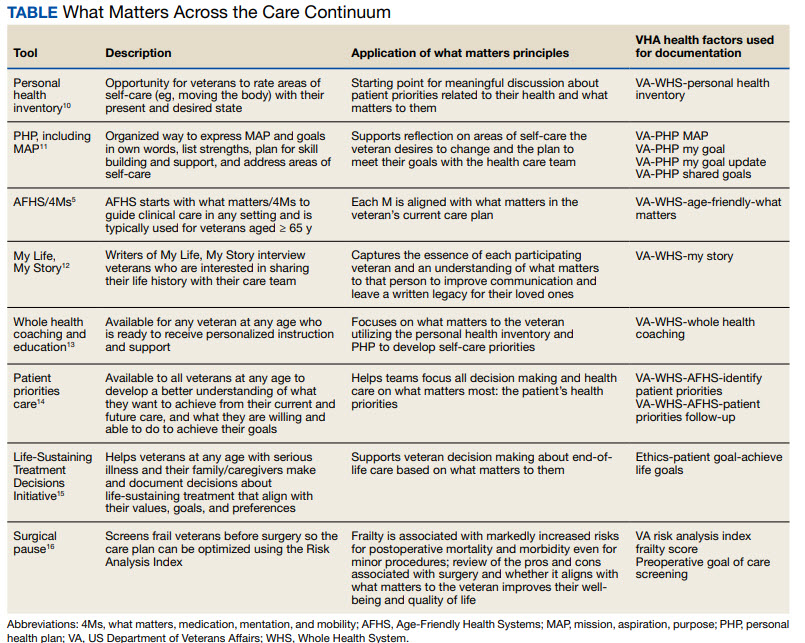

DOCUMENTATION

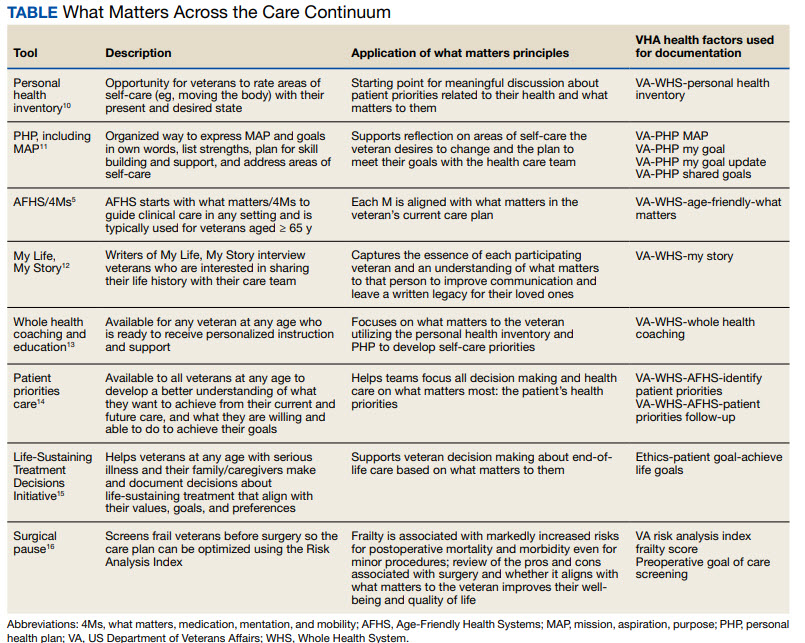

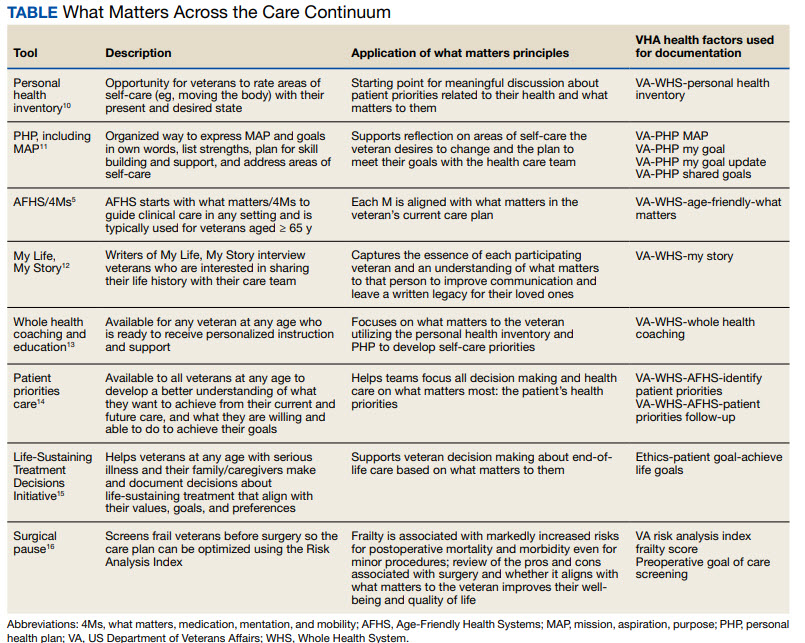

The VHA leverages several tools and evidence-based practices to assess and act on what matters for veterans of all ages (Table).5,10-16 The VHA EHR and associated dashboards contain a wealth of information about whole health and AFHS implementation, scale up, and spread. A national AFHS 4Ms note template contains standardized data elements called health factors, which provide a mechanism for monitoring 4Ms care via its related dashboard. This template was developed by an interprofessional workgroup of VHA staff and underwent a thorough human factors engineering review and testing process prior to its release. Although teams continue to personalize care based on what matters to the veteran, data from the standardized 4Ms note template and dashboard provide a way to establish consistent, equitable care across multiple care settings.17

Between January 2022 and December 2023, > 612,000 participants aged ≥ 65 years identified what matters to them through 1.35 million assessments. During that period, > 36,000 veterans aged ≥ 65 years participated in AFHS and had what matters conversations documented. A personalized health plan was completed by 585,270 veterans for a total of 1.1 million assessments.11 Whole health coaching has been documented for > 57,000 veterans with > 200,000 assessments completed.13 In fiscal year 2023, a total of 1,802,131 veterans participated in whole health.

When teams share information about what matters to the veteran in a clinicianfacing format in the EHR, this helps ensure that the VHA honors veteran preferences throughout transitions of care and across all phases of health care. Although the EHR captures data on what matters, measurement of the overall impact on veteran and health system outcomes is essential. Further evaluation and ongoing education are needed to ensure clinicians are accurately and efficiently capturing the care provided by completing the appropriate EHR. Additional challenges include identifying ways to balance the documentation burden, while ensuring notes include valuable patient-centered information to guide care. EHR tools and templates have helped to unlock important insights on health care delivery in the VHA; however, health systems must consider how these clinical practices support the overall well-being of patients. How leaders empower frontline clinicians in any care setting to use these data to drive meaningful change is also important.

TRANSFORMING VHA CARE DELIVERY

In Achieving Whole Health: A New Approach for Veterans and the Nation, the National Academy of Science proposes a framework for the transformation of health care institutions to provide better whole health to veterans.3 Transformation requires change in entire systems and leaders who mobilize people “for participation in the process of change, encouraging a sense of collective identity and collective efficacy, which in turn brings stronger feelings of self-worth and self-efficacy,” and an enhanced sense of meaningfulness in their work and lives.18

Shifting health care approaches to equipping and empowering veterans and employees with whole health and AFHS resources is transformational and requires radically different assumptions and approaches that cannot be realized through traditional approaches. This change requires robust and multifaceted cultural transformation spanning all levels of the organization. Whole health and AFHS are facilitating this transformation by supporting documentation and data needs, tracking outcomes across settings, and accelerating spread to new facilities and care settings nationwide to support older veterans in improving their health and well-being.

Whole health and AFHS are complementary approaches to care that can work to empower veterans (as well as caregivers and clinicians) to align services with what matters most to veterans. Lessons such as standardizing person-centered assessments of what matters, creating supportive structures to better align care with veterans’ priorities, and identifying meaningful veteran and system-level outcomes to help sustain transformational change can be applied from whole health to AFHS. Together these programs have the potential to enhance overall health outcomes and quality of life for veterans.

- Kligler B, Hyde J, Gantt C, Bokhour B. The Whole Health transformation at the Veterans Health Administration: moving from “what’s the matter with you?” to “what matters to you?” Med Care. 2022;60(5):387-391. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001706

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Social determinants of health (SDOH) at CDC. January 17, 2024. Accessed September 12, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/public-health-gateway/php/about/social-determinants-of-health.html

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Achieving Whole Health: A New Approach for Veterans and the Nation. The National Academies Press; 2023. Accessed September 9, 2024. doi:10.17226/26854

- Church K, Munro S, Shaughnessy M, Clancy C. Age-friendly health systems: improving care for older adults in the Veterans Health Administration. Health Serv Res. 2023;58 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):5-8. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14110

- Laderman M, Jackson C, Little K, Duong T, Pelton L. “What Matters” to older adults? A toolkit for health systems to design better care with older adults. Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2019. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Documents/IHI_Age_Friendly_What_Matters_to_Older_Adults_Toolkit.pdf

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Age-Friendly Health Systems. Updated September 4, 2024. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://marketplace.va.gov/innovations/age-friendly-health-systems

- Brown TT, Hurley VB, Rodriguez HP, et al. Shared dec i s i o n - m a k i n g l o w e r s m e d i c a l e x p e n d i t u re s a n d the effect is amplified in racially-ethnically concordant relationships. Med Care. 2023;61(8):528-535. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001881

- Kligler B. Whole Health in the Veterans Health Administration. Glob Adv Health Med. 2022;11:2164957X221077214.

- Ruggeri K, Garcia-Garzon E, Maguire Á, Matz S, Huppert FA. Well-being is more than happiness and life satisfaction: a multidimensional analysis of 21 countries. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):192. doi:10.1186/s12955-020-01423-y

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Personal Health Inventory. Updated May 2022. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/docs/PHI-long-May22-fillable-508.pdf doi:10.1177/2164957X221077214

- Veterans Health Administration. Personal Health Plan. Updated March 2019. Accessed September 9, 2024. https:// www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/docs/PersonalHealthPlan_508_03-2019.pdf

- Veterans Health Administration. Whole Health: My Life, My Story. Updated March 20, 2024. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/mylifemystory/index.asp

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Whole Health Library: Whole Health for Skill Building. Updated April 17, 2024. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTHLIBRARY/courses/whole-health-skill-building.asp

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Making Decisions: Current Care Planning. Updated May 21, 2024. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.va.gov/geriatrics/pages/making_decisions.asp

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Initiative (LSTDI). Updated March 2024. Accessed September 12, 2024. https://marketplace.va.gov/innovations/life-sustaining-treatment-decisions-initiative

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion: Surgical Pause Saving Veterans Lives. Updated September 22, 2021. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.cherp.research.va.gov/features/Surgical_Pause_Saving_Veterans_Lives.asp

- Munro S, Church K, Berner C, et al. Implementation of an agefriendly template in the Veterans Health Administration electronic health record. J Inform Nurs. 2023;8(3):6-11.

- Burns JM. Transforming Leadership: A New Pursuit of Happiness. Grove Press; 2003.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. Whole Health: Circle of Health Overview. Updated May 20, 2024. Accessed September 12, 2024. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/circle-of-health/index.asp