User login

Annual physical exam

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of leukemic non-nodal mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

MCL is a rare mature B-cell neoplasm characterized by t(11;14) (q13;q32) and cyclin D1 overexpression in more than 95% of cases. It accounts for approximately 5%-7% of all lymphomas, with an annual incidence of one case per 200,000 people. In North America and Europe, the incidence of MCL is like that of noncutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphomas. MCL occurs more frequently in men than in women (3:1), and the median age at diagnosis ranges from ages 60-70 years.

In recent years, MCL has been categorized into two major subgroups that have distinct clinical presentation and molecular features: nodal MCL and leukemic non-nodal MCL. Nodal MCL is a common variant with an aggressive disease course. Unmutated IGHV gene rearrangement, SOX11 overexpression, a higher degree of genomic instability (eg, ATM, CDKN2A, chromatin modifier mutations), and other oncogenic mutations and epigenetic modifications are seen in patients with this variant.

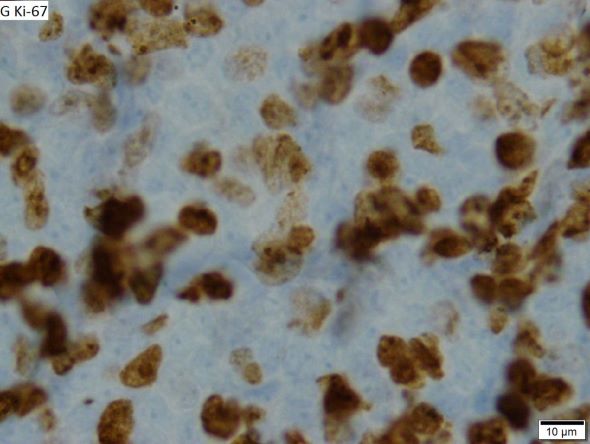

Leukemic non-nodal MCL is seen in 10%-20% of patients with MCL. Patients frequently present with lymphocytosis and splenomegaly. In most cases, it is associated with an indolent disease course and superior outcome. This subtype is largely IGHV mutated and mostly SOX11-negative, with positive expression of CD200, peripheral blood, bone marrow, and splenic involvement, low tumor burden, and a low Ki-67 index.

Recognition of the leukemic non-nodal MCL immunophenotype enables it to be differentiated from other CD5-positive B-cell cancers, particularly classical MCL and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). The overexpression of cyclin D1, the presence of the t(11;14) translocation, and the absence of chromosomal markers typically present in CLL differentiate leukemic non-nodal MCL from CLL. Moreover, CLL has high expression of CD23 and is negative for SOX11 and CD200.

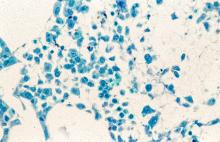

Pathologic features of MCL include small- to medium-size lymphocytes with scant cytoplasm, clumped chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and prominent nuclear clefts. Observed growth patterns include diffuse, nodular (more vague and less discrete than that found in follicular lymphomas), mantle-zone lymphoma with expansion of mantle zones, and in situ mantle-cell neoplasia [typical cells with the characteristic t(11;14) translocation, scattered in the mantle zone of otherwise normal-appearing lymph nodes]. Cytologic subtypes include classic MCL, the blastoid subtype (large cells, dispersed chromatin, and a high mitotic rate), and the pleomorphic subtype (cells of variable sizes, although many are large, with pale cytoplasm, oval irregular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli).

MCL is a challenging disease to treat. Despite treatment advances, it is largely incurable, with a median overall survival of 1.8-9.4 years, depending on whether it is aggressive or indolent MCL. The aggressiveness of the disease, the patient's performance status, age, and mantle cell international prognostic index score should all be considered when selecting treatment because there is no standard curative treatment.

According to the 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), for patients with indolent disease (eg, IGHV mutated and mostly SOX11-negative with leukemic and non-nodal presentation), observation is reasonable when patients are asymptomatic and have no indications for treatment. For patients with symptomatic disease or other indications for treatment, induction therapy with aggressive regimens is recommended when patients do not have a TP53 mutation. The optimum approach for patients with TP53 mutation is not yet known; induction therapy followed by high-dose therapy with autologous stem cell transplant or less aggressive regimens could be an option for these patients.

Treatment options for relapsed/refractory MCL include radiotherapy; traditional chemotherapy regimens, with or without rituximab; and newer targeted therapies. These include Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (ibrutinib, zanubrutinib, acalabrutinib, pirtobrutinib), lenalidomide, bortezomib, the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors temsirolimus and everolimus, the phosphatidylinositol 3–kinase inhibitors idelalisib and umbralisib, and the B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibitor venetoclax. These agents are frequently administered in combination with rituximab or another anti-CD20 antibody.

For comprehensive guidance on the treatment of MCL, consult the complete NCCN guidelines.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of leukemic non-nodal mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

MCL is a rare mature B-cell neoplasm characterized by t(11;14) (q13;q32) and cyclin D1 overexpression in more than 95% of cases. It accounts for approximately 5%-7% of all lymphomas, with an annual incidence of one case per 200,000 people. In North America and Europe, the incidence of MCL is like that of noncutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphomas. MCL occurs more frequently in men than in women (3:1), and the median age at diagnosis ranges from ages 60-70 years.

In recent years, MCL has been categorized into two major subgroups that have distinct clinical presentation and molecular features: nodal MCL and leukemic non-nodal MCL. Nodal MCL is a common variant with an aggressive disease course. Unmutated IGHV gene rearrangement, SOX11 overexpression, a higher degree of genomic instability (eg, ATM, CDKN2A, chromatin modifier mutations), and other oncogenic mutations and epigenetic modifications are seen in patients with this variant.

Leukemic non-nodal MCL is seen in 10%-20% of patients with MCL. Patients frequently present with lymphocytosis and splenomegaly. In most cases, it is associated with an indolent disease course and superior outcome. This subtype is largely IGHV mutated and mostly SOX11-negative, with positive expression of CD200, peripheral blood, bone marrow, and splenic involvement, low tumor burden, and a low Ki-67 index.

Recognition of the leukemic non-nodal MCL immunophenotype enables it to be differentiated from other CD5-positive B-cell cancers, particularly classical MCL and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). The overexpression of cyclin D1, the presence of the t(11;14) translocation, and the absence of chromosomal markers typically present in CLL differentiate leukemic non-nodal MCL from CLL. Moreover, CLL has high expression of CD23 and is negative for SOX11 and CD200.

Pathologic features of MCL include small- to medium-size lymphocytes with scant cytoplasm, clumped chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and prominent nuclear clefts. Observed growth patterns include diffuse, nodular (more vague and less discrete than that found in follicular lymphomas), mantle-zone lymphoma with expansion of mantle zones, and in situ mantle-cell neoplasia [typical cells with the characteristic t(11;14) translocation, scattered in the mantle zone of otherwise normal-appearing lymph nodes]. Cytologic subtypes include classic MCL, the blastoid subtype (large cells, dispersed chromatin, and a high mitotic rate), and the pleomorphic subtype (cells of variable sizes, although many are large, with pale cytoplasm, oval irregular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli).

MCL is a challenging disease to treat. Despite treatment advances, it is largely incurable, with a median overall survival of 1.8-9.4 years, depending on whether it is aggressive or indolent MCL. The aggressiveness of the disease, the patient's performance status, age, and mantle cell international prognostic index score should all be considered when selecting treatment because there is no standard curative treatment.

According to the 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), for patients with indolent disease (eg, IGHV mutated and mostly SOX11-negative with leukemic and non-nodal presentation), observation is reasonable when patients are asymptomatic and have no indications for treatment. For patients with symptomatic disease or other indications for treatment, induction therapy with aggressive regimens is recommended when patients do not have a TP53 mutation. The optimum approach for patients with TP53 mutation is not yet known; induction therapy followed by high-dose therapy with autologous stem cell transplant or less aggressive regimens could be an option for these patients.

Treatment options for relapsed/refractory MCL include radiotherapy; traditional chemotherapy regimens, with or without rituximab; and newer targeted therapies. These include Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (ibrutinib, zanubrutinib, acalabrutinib, pirtobrutinib), lenalidomide, bortezomib, the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors temsirolimus and everolimus, the phosphatidylinositol 3–kinase inhibitors idelalisib and umbralisib, and the B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibitor venetoclax. These agents are frequently administered in combination with rituximab or another anti-CD20 antibody.

For comprehensive guidance on the treatment of MCL, consult the complete NCCN guidelines.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of leukemic non-nodal mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

MCL is a rare mature B-cell neoplasm characterized by t(11;14) (q13;q32) and cyclin D1 overexpression in more than 95% of cases. It accounts for approximately 5%-7% of all lymphomas, with an annual incidence of one case per 200,000 people. In North America and Europe, the incidence of MCL is like that of noncutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphomas. MCL occurs more frequently in men than in women (3:1), and the median age at diagnosis ranges from ages 60-70 years.

In recent years, MCL has been categorized into two major subgroups that have distinct clinical presentation and molecular features: nodal MCL and leukemic non-nodal MCL. Nodal MCL is a common variant with an aggressive disease course. Unmutated IGHV gene rearrangement, SOX11 overexpression, a higher degree of genomic instability (eg, ATM, CDKN2A, chromatin modifier mutations), and other oncogenic mutations and epigenetic modifications are seen in patients with this variant.

Leukemic non-nodal MCL is seen in 10%-20% of patients with MCL. Patients frequently present with lymphocytosis and splenomegaly. In most cases, it is associated with an indolent disease course and superior outcome. This subtype is largely IGHV mutated and mostly SOX11-negative, with positive expression of CD200, peripheral blood, bone marrow, and splenic involvement, low tumor burden, and a low Ki-67 index.

Recognition of the leukemic non-nodal MCL immunophenotype enables it to be differentiated from other CD5-positive B-cell cancers, particularly classical MCL and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). The overexpression of cyclin D1, the presence of the t(11;14) translocation, and the absence of chromosomal markers typically present in CLL differentiate leukemic non-nodal MCL from CLL. Moreover, CLL has high expression of CD23 and is negative for SOX11 and CD200.

Pathologic features of MCL include small- to medium-size lymphocytes with scant cytoplasm, clumped chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and prominent nuclear clefts. Observed growth patterns include diffuse, nodular (more vague and less discrete than that found in follicular lymphomas), mantle-zone lymphoma with expansion of mantle zones, and in situ mantle-cell neoplasia [typical cells with the characteristic t(11;14) translocation, scattered in the mantle zone of otherwise normal-appearing lymph nodes]. Cytologic subtypes include classic MCL, the blastoid subtype (large cells, dispersed chromatin, and a high mitotic rate), and the pleomorphic subtype (cells of variable sizes, although many are large, with pale cytoplasm, oval irregular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli).

MCL is a challenging disease to treat. Despite treatment advances, it is largely incurable, with a median overall survival of 1.8-9.4 years, depending on whether it is aggressive or indolent MCL. The aggressiveness of the disease, the patient's performance status, age, and mantle cell international prognostic index score should all be considered when selecting treatment because there is no standard curative treatment.

According to the 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), for patients with indolent disease (eg, IGHV mutated and mostly SOX11-negative with leukemic and non-nodal presentation), observation is reasonable when patients are asymptomatic and have no indications for treatment. For patients with symptomatic disease or other indications for treatment, induction therapy with aggressive regimens is recommended when patients do not have a TP53 mutation. The optimum approach for patients with TP53 mutation is not yet known; induction therapy followed by high-dose therapy with autologous stem cell transplant or less aggressive regimens could be an option for these patients.

Treatment options for relapsed/refractory MCL include radiotherapy; traditional chemotherapy regimens, with or without rituximab; and newer targeted therapies. These include Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (ibrutinib, zanubrutinib, acalabrutinib, pirtobrutinib), lenalidomide, bortezomib, the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors temsirolimus and everolimus, the phosphatidylinositol 3–kinase inhibitors idelalisib and umbralisib, and the B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibitor venetoclax. These agents are frequently administered in combination with rituximab or another anti-CD20 antibody.

For comprehensive guidance on the treatment of MCL, consult the complete NCCN guidelines.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 67-year-old White man presents for his annual physical examination. The patient is a physical therapist and reports regular exercise and adherence to a healthy diet. His previous medical history is unremarkable. There is a family history of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (paternal uncle). The patient has no complaints or concerns about his health.

Physical examination reveals non-tender abdominal distention and splenomegaly. Pertinent laboratory findings include hemoglobin = 10/g/dL; red blood cell = 3.28 M/mcL; mean corpuscular volume = 54.2 fL, hematocrit = 34%; and absolute lymphocyte count = 4820/µL.

Flow cytometry showed high positivity for CD5, no expression of SOX11, low expression of CD23 and CD200, and overexpression of cyclin D1. A bone marrow biopsy is performed and show an abnormal B-lymphoid infiltrate. Fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis revealed t(11;14)(q13;q32) and mutated IGHV. A blood smear showed abnormal mononuclear cells and atypical lymphocytes.

Three-month history of fever

This patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of pleomorphic mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

MCL is a rare, clinically and biologically heterogeneous B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It accounts for approximately 5%-7% of all lymphomas. In North America and Europe, its incidence is akin to that of noncutaneous, peripheral T-cell lymphomas. The typical age at diagnosis is between 60 and 70 years. Approximately 70% of all cases are seen in men.

Little is known about risk factors for the development of MCL. Factors that have been associated with the development of other lymphomas (eg, familial risk, immunosuppression, other immune disorders, chemical and occupational exposures, and infectious agents) have not been convincingly identified as predisposing factors for MCL, with the possible exception of family history.

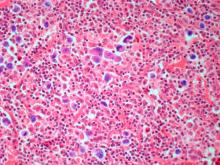

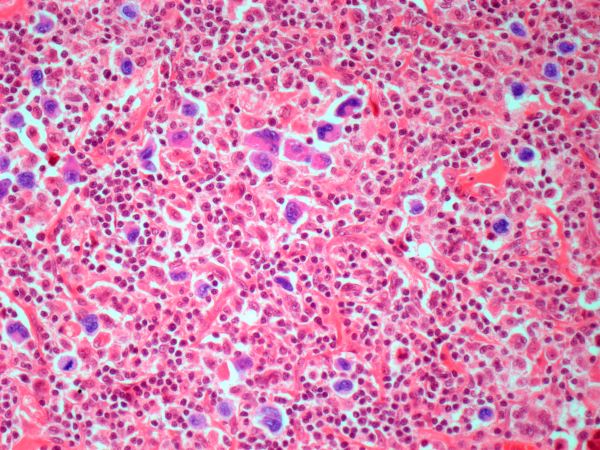

MCL is usually associated with reciprocal chromosomal translocation between chromosomes 11 and 14, t(11;14)(q13:q32), resulting in overexpression of cyclin D1, which plays a key role in tumor cell proliferation through cell-cycle dysregulation, chromosomal instability, and epigenetic regulation. Tumor cells (monoclonal B cells) express surface immunoglobulin, immunoglobulin M, or immunoglobulin D. Cells are usually CD5+ and pan B-cell antigen positive (eg, CD19, CD20, CD22) with no expression of CD10 and CD23. Histologic features include small-to-medium lymphocytes with scant cytoplasm, clumped chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and prominent nuclear clefts. Cytologic subtypes include classic MCL, the blastoid variant (large cells, dispersed chromatin, and a high mitotic rate), and the pleomorphic variant (cells of varying size, although many are large, with pale cytoplasm, oval irregular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli). Blastoid and pleomorphic MCL typically have a more aggressive natural history and are associated with inferior clinical outcomes.

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), an accurate pathologic diagnosis of the subtype is the most important initial step in the management of B-cell lymphomas, including pleomorphic MCL. The basic pathologic exam is the same for all subtypes, although additional testing may be needed in certain cases. An incisional or excisional lymph node biopsy is recommended. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy alone is typically not sufficient for the initial diagnosis of lymphoma; however, its diagnostic accuracy is significantly improved when it is used in combination with immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry. Immunohistochemistry is essential to differentiate MCL subtypes.

Essential workup procedures include a complete physical exam, with particular attention to node-bearing areas, including the Waldeyer ring, as well as the size of the liver and spleen, and assessment of performance status and B symptoms (fever, night sweats, unintentional weight loss). Laboratory studies should include complete blood count with differential, measurement of serum lactate dehydrogenase, hepatitis B virus testing, and a comprehensive metabolic panel. Required imaging studies include PET/CT (or chest/abdominal/pelvic CT with oral and intravenous contrast if PET/CT is not available) and multigated acquisition scanning or echocardiography when anthracyclines and anthracenedione-containing regimens are indicated.

A watch-and-wait approach may be appropriate for some patients with indolent MCL; however, patients with aggressive MCL, such as pleomorphic histology, require chemoimmunotherapy at diagnosis. For patients who relapse or achieve an incomplete response to first-line therapy, the NCCN guidelines recommend second-line treatment with a Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor–containing regimen. Available BTK inhibitors include acalabrutinib, ibrutinib ± rituximab, zanubrutinib, and pirtobrutinib. Chemoimmunotherapy with lenalidomide + rituximab is another second-line option and may be particularly helpful for patients in whom a BTK inhibitor is contraindicated. Anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy is a recommended option for the third line and beyond.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of pleomorphic mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

MCL is a rare, clinically and biologically heterogeneous B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It accounts for approximately 5%-7% of all lymphomas. In North America and Europe, its incidence is akin to that of noncutaneous, peripheral T-cell lymphomas. The typical age at diagnosis is between 60 and 70 years. Approximately 70% of all cases are seen in men.

Little is known about risk factors for the development of MCL. Factors that have been associated with the development of other lymphomas (eg, familial risk, immunosuppression, other immune disorders, chemical and occupational exposures, and infectious agents) have not been convincingly identified as predisposing factors for MCL, with the possible exception of family history.

MCL is usually associated with reciprocal chromosomal translocation between chromosomes 11 and 14, t(11;14)(q13:q32), resulting in overexpression of cyclin D1, which plays a key role in tumor cell proliferation through cell-cycle dysregulation, chromosomal instability, and epigenetic regulation. Tumor cells (monoclonal B cells) express surface immunoglobulin, immunoglobulin M, or immunoglobulin D. Cells are usually CD5+ and pan B-cell antigen positive (eg, CD19, CD20, CD22) with no expression of CD10 and CD23. Histologic features include small-to-medium lymphocytes with scant cytoplasm, clumped chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and prominent nuclear clefts. Cytologic subtypes include classic MCL, the blastoid variant (large cells, dispersed chromatin, and a high mitotic rate), and the pleomorphic variant (cells of varying size, although many are large, with pale cytoplasm, oval irregular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli). Blastoid and pleomorphic MCL typically have a more aggressive natural history and are associated with inferior clinical outcomes.

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), an accurate pathologic diagnosis of the subtype is the most important initial step in the management of B-cell lymphomas, including pleomorphic MCL. The basic pathologic exam is the same for all subtypes, although additional testing may be needed in certain cases. An incisional or excisional lymph node biopsy is recommended. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy alone is typically not sufficient for the initial diagnosis of lymphoma; however, its diagnostic accuracy is significantly improved when it is used in combination with immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry. Immunohistochemistry is essential to differentiate MCL subtypes.

Essential workup procedures include a complete physical exam, with particular attention to node-bearing areas, including the Waldeyer ring, as well as the size of the liver and spleen, and assessment of performance status and B symptoms (fever, night sweats, unintentional weight loss). Laboratory studies should include complete blood count with differential, measurement of serum lactate dehydrogenase, hepatitis B virus testing, and a comprehensive metabolic panel. Required imaging studies include PET/CT (or chest/abdominal/pelvic CT with oral and intravenous contrast if PET/CT is not available) and multigated acquisition scanning or echocardiography when anthracyclines and anthracenedione-containing regimens are indicated.

A watch-and-wait approach may be appropriate for some patients with indolent MCL; however, patients with aggressive MCL, such as pleomorphic histology, require chemoimmunotherapy at diagnosis. For patients who relapse or achieve an incomplete response to first-line therapy, the NCCN guidelines recommend second-line treatment with a Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor–containing regimen. Available BTK inhibitors include acalabrutinib, ibrutinib ± rituximab, zanubrutinib, and pirtobrutinib. Chemoimmunotherapy with lenalidomide + rituximab is another second-line option and may be particularly helpful for patients in whom a BTK inhibitor is contraindicated. Anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy is a recommended option for the third line and beyond.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of pleomorphic mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

MCL is a rare, clinically and biologically heterogeneous B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It accounts for approximately 5%-7% of all lymphomas. In North America and Europe, its incidence is akin to that of noncutaneous, peripheral T-cell lymphomas. The typical age at diagnosis is between 60 and 70 years. Approximately 70% of all cases are seen in men.

Little is known about risk factors for the development of MCL. Factors that have been associated with the development of other lymphomas (eg, familial risk, immunosuppression, other immune disorders, chemical and occupational exposures, and infectious agents) have not been convincingly identified as predisposing factors for MCL, with the possible exception of family history.

MCL is usually associated with reciprocal chromosomal translocation between chromosomes 11 and 14, t(11;14)(q13:q32), resulting in overexpression of cyclin D1, which plays a key role in tumor cell proliferation through cell-cycle dysregulation, chromosomal instability, and epigenetic regulation. Tumor cells (monoclonal B cells) express surface immunoglobulin, immunoglobulin M, or immunoglobulin D. Cells are usually CD5+ and pan B-cell antigen positive (eg, CD19, CD20, CD22) with no expression of CD10 and CD23. Histologic features include small-to-medium lymphocytes with scant cytoplasm, clumped chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and prominent nuclear clefts. Cytologic subtypes include classic MCL, the blastoid variant (large cells, dispersed chromatin, and a high mitotic rate), and the pleomorphic variant (cells of varying size, although many are large, with pale cytoplasm, oval irregular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli). Blastoid and pleomorphic MCL typically have a more aggressive natural history and are associated with inferior clinical outcomes.

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), an accurate pathologic diagnosis of the subtype is the most important initial step in the management of B-cell lymphomas, including pleomorphic MCL. The basic pathologic exam is the same for all subtypes, although additional testing may be needed in certain cases. An incisional or excisional lymph node biopsy is recommended. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy alone is typically not sufficient for the initial diagnosis of lymphoma; however, its diagnostic accuracy is significantly improved when it is used in combination with immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry. Immunohistochemistry is essential to differentiate MCL subtypes.

Essential workup procedures include a complete physical exam, with particular attention to node-bearing areas, including the Waldeyer ring, as well as the size of the liver and spleen, and assessment of performance status and B symptoms (fever, night sweats, unintentional weight loss). Laboratory studies should include complete blood count with differential, measurement of serum lactate dehydrogenase, hepatitis B virus testing, and a comprehensive metabolic panel. Required imaging studies include PET/CT (or chest/abdominal/pelvic CT with oral and intravenous contrast if PET/CT is not available) and multigated acquisition scanning or echocardiography when anthracyclines and anthracenedione-containing regimens are indicated.

A watch-and-wait approach may be appropriate for some patients with indolent MCL; however, patients with aggressive MCL, such as pleomorphic histology, require chemoimmunotherapy at diagnosis. For patients who relapse or achieve an incomplete response to first-line therapy, the NCCN guidelines recommend second-line treatment with a Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor–containing regimen. Available BTK inhibitors include acalabrutinib, ibrutinib ± rituximab, zanubrutinib, and pirtobrutinib. Chemoimmunotherapy with lenalidomide + rituximab is another second-line option and may be particularly helpful for patients in whom a BTK inhibitor is contraindicated. Anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy is a recommended option for the third line and beyond.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 62-year-old man with no significant past medical history presents with a 3-month history of fever, night sweats, upper abdominal pain and bloating, and unintentional weight loss. He does not currently take any medications. His height and weight are 6 ft 2 in and 171 lb (BMI 22).

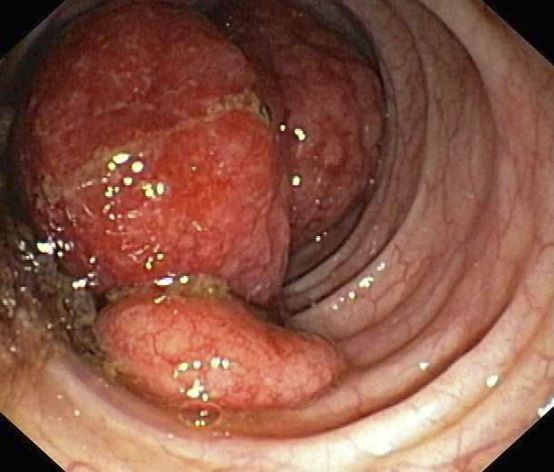

Physical examination reveals generalized lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly. Subsequently, an excisional lymph node biopsy is performed. Histologic examination of the specimen reveals sheets of mostly large cells of varying sizes, with nuclear overlap and extensive necrosis. Cytology findings include large lymphocytes with pale cytoplasm, clumped chromatin, oval irregular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. Pertinent findings from immunohistochemical staining include the presence of t(11:14), Ki67 > 30%, CD5 and CD20 positivity, and CD10 and CD23 negativity. Centroblasts are absent.

MCL Treatment

Intermittent abdominal pain

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is an aggressive form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma characterized by the proliferation of CD5-positive B cells within the mantle zone that surrounds normal germinal center follicles. MCL is a rare disease that most commonly presents in adult men (male to female ratio > 2:1) in the fifth and sixth decades of life. Individuals diagnosed with MCL typically present with constitutional symptoms, such as weight loss, night sweats, persistent fever, and fatigue. Approximately 25% of cases present with extranodal involvement with the bone marrow; peripheral blood and gastrointestinal tract are most often involved. In patients with extensive node involvement in the gastrointestinal tract, additional symptoms at presentation often include abdominal pain, abdominal fullness, and bloating. Skin involvement in MCL is rare and usually indicates widespread disease.

According to the guidelines of the World Health Organization–European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, a diagnosis of MCL is established on the basis of the morphologic examination findings and immunophenotyping.

Immunohistochemically, expression of cyclin D1 in normal lymphoid cells is very low and often undetectable; only hairy cell leukemia shows moderate expression of cyclin D1. Therefore, positive immunohistochemistry for cyclin D1 is pathognomonic for MCL. Increased expression of cyclin D1 protein leads to dysregulation of the cell cycle and stimulates uncontrolled cell proliferation. It is also indirect evidence of the chromosomal translocation (11;14)(q13;q32) on the CCND1 gene, which is detected in 95% of cases of MCL. In addition, negative expression of antigens may also help to differentiate MCL from other lymphomas. MCL does not usually express the antigens that are associated with germinal centers, such as CD10, CD23, and BCL6. Thus, these antigens can be used to distinguish MCL from B-cell lymphomas of germinal center origin, including follicular lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends chemotherapy followed by radiation for stage I or II disease. In general, patients with advanced-stage disease benefit from systemic chemotherapy. Because MCL is clinically heterogeneous, treatment may require adjustment on the basis of the patient's age, underlying comorbidities, and underlying MCL biology such as TP53 mutations. During induction therapy, prophylaxis and monitoring for tumor lysis syndrome is strongly recommended to be considered. Before treatment, hepatitis B virus testing is recommended because of an increased risk for viral reactivation with use of immunotherapy regimens for treatment.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is an aggressive form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma characterized by the proliferation of CD5-positive B cells within the mantle zone that surrounds normal germinal center follicles. MCL is a rare disease that most commonly presents in adult men (male to female ratio > 2:1) in the fifth and sixth decades of life. Individuals diagnosed with MCL typically present with constitutional symptoms, such as weight loss, night sweats, persistent fever, and fatigue. Approximately 25% of cases present with extranodal involvement with the bone marrow; peripheral blood and gastrointestinal tract are most often involved. In patients with extensive node involvement in the gastrointestinal tract, additional symptoms at presentation often include abdominal pain, abdominal fullness, and bloating. Skin involvement in MCL is rare and usually indicates widespread disease.

According to the guidelines of the World Health Organization–European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, a diagnosis of MCL is established on the basis of the morphologic examination findings and immunophenotyping.

Immunohistochemically, expression of cyclin D1 in normal lymphoid cells is very low and often undetectable; only hairy cell leukemia shows moderate expression of cyclin D1. Therefore, positive immunohistochemistry for cyclin D1 is pathognomonic for MCL. Increased expression of cyclin D1 protein leads to dysregulation of the cell cycle and stimulates uncontrolled cell proliferation. It is also indirect evidence of the chromosomal translocation (11;14)(q13;q32) on the CCND1 gene, which is detected in 95% of cases of MCL. In addition, negative expression of antigens may also help to differentiate MCL from other lymphomas. MCL does not usually express the antigens that are associated with germinal centers, such as CD10, CD23, and BCL6. Thus, these antigens can be used to distinguish MCL from B-cell lymphomas of germinal center origin, including follicular lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends chemotherapy followed by radiation for stage I or II disease. In general, patients with advanced-stage disease benefit from systemic chemotherapy. Because MCL is clinically heterogeneous, treatment may require adjustment on the basis of the patient's age, underlying comorbidities, and underlying MCL biology such as TP53 mutations. During induction therapy, prophylaxis and monitoring for tumor lysis syndrome is strongly recommended to be considered. Before treatment, hepatitis B virus testing is recommended because of an increased risk for viral reactivation with use of immunotherapy regimens for treatment.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is an aggressive form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma characterized by the proliferation of CD5-positive B cells within the mantle zone that surrounds normal germinal center follicles. MCL is a rare disease that most commonly presents in adult men (male to female ratio > 2:1) in the fifth and sixth decades of life. Individuals diagnosed with MCL typically present with constitutional symptoms, such as weight loss, night sweats, persistent fever, and fatigue. Approximately 25% of cases present with extranodal involvement with the bone marrow; peripheral blood and gastrointestinal tract are most often involved. In patients with extensive node involvement in the gastrointestinal tract, additional symptoms at presentation often include abdominal pain, abdominal fullness, and bloating. Skin involvement in MCL is rare and usually indicates widespread disease.

According to the guidelines of the World Health Organization–European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, a diagnosis of MCL is established on the basis of the morphologic examination findings and immunophenotyping.

Immunohistochemically, expression of cyclin D1 in normal lymphoid cells is very low and often undetectable; only hairy cell leukemia shows moderate expression of cyclin D1. Therefore, positive immunohistochemistry for cyclin D1 is pathognomonic for MCL. Increased expression of cyclin D1 protein leads to dysregulation of the cell cycle and stimulates uncontrolled cell proliferation. It is also indirect evidence of the chromosomal translocation (11;14)(q13;q32) on the CCND1 gene, which is detected in 95% of cases of MCL. In addition, negative expression of antigens may also help to differentiate MCL from other lymphomas. MCL does not usually express the antigens that are associated with germinal centers, such as CD10, CD23, and BCL6. Thus, these antigens can be used to distinguish MCL from B-cell lymphomas of germinal center origin, including follicular lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends chemotherapy followed by radiation for stage I or II disease. In general, patients with advanced-stage disease benefit from systemic chemotherapy. Because MCL is clinically heterogeneous, treatment may require adjustment on the basis of the patient's age, underlying comorbidities, and underlying MCL biology such as TP53 mutations. During induction therapy, prophylaxis and monitoring for tumor lysis syndrome is strongly recommended to be considered. Before treatment, hepatitis B virus testing is recommended because of an increased risk for viral reactivation with use of immunotherapy regimens for treatment.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 69-year-old man presents for an evaluation for a 3-month history of generalized intermittent abdominal pain with occasional dark blood with bowel movements. He does not report experiencing any fever, chills, diarrhea, or obstructive symptoms. However, he does note a 10-lb weight loss over the past few months. He underwent routine screening colonoscopy 5 years ago, which was unremarkable. Complete blood count reveals normocytic anemia. CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis demonstrated extensive mesenteric lymphadenopathy and bilateral axillary lymphadenopathy. Physical examination reveals an enlarged right inguinal lymph node, diffuse cutaneous erythematous plaques, and nodules with irregular borders on the upper back. Lesion diameters range from 0.5 to 1.5 cm, with the largest having a central ulceration.

A biopsy of one of the skin lesions was performed. Histopathologic examination demonstrated diffuse lymphoid infiltrate composed predominately of small, mature lymphocytes. Immunohistochemistry showed expression of cyclin D1, CD5, CD20, SOX11, and BCL2. Lesions were negative for CD10, CD23, and BCL6.

MCL Workup

Abdominal pain and constipation

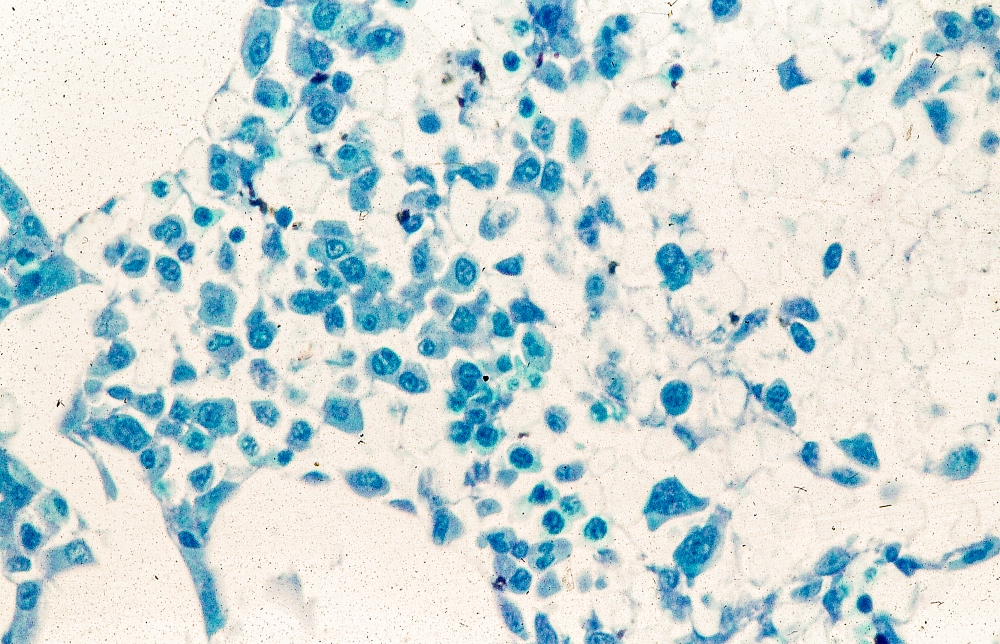

This patient's clinical presentation and endoscopy findings are consistent with a diagnosis of recurrent MCL presenting as a colonic mass.

MCL is an aggressive type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that accounts for approximately 5%-7% of all lymphomas. Nearly 80% of patients have extranodal involvement at initial presentation, occurring in sites such as the bone marrow, spleen, Waldeyer ring, and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Secondary GI involvement in MCL (involving nodal and/or other extranodal tissue) is common and may be detected at diagnosis and/or relapse. In several retrospective studies, the prevalence of secondary GI involvement in MCL ranged from 15% to 30%. However, in later studies, routine endoscopies in patients with untreated MCL showed GI involvement in up to 90% of patients, despite most patients not reporting GI symptoms.

The colon is the most commonly involved GI site; however, both the upper and lower GI tract from the stomach to the colon can be involved. Lymphomatous polyposis is the most common endoscopic presentation of MCL, but polyp, mass, or even normal-appearing mucosa may also be seen.

New and emerging treatment options are helping to improve survival in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL. According to National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, the preferred second-line and subsequent regimens are:

• Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors:

o Acalabrutinib

o Ibrutinib ± rituximab

o Zanubrutinib

• Lenalidomide + rituximab (if BTK inhibitor is contraindicated)

Other regimens that may be useful in certain circumstances are:

• Bendamustine + rituximab (if not previously given)

• Bendamustine + rituximab + cytarabine (RBAC500) (if not previously given)

• Bortezomib ± rituximab

• RDHA (rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine) + platinum (carboplatin, cisplatin, or oxaliplatin) (if not previously given)

• GemOx (gemcitabine, oxaliplatin) + rituximab

• Ibrutinib, lenalidomide, rituximab (category 2B)

• Ibrutinib + venetoclax

• Venetoclax, lenalidomide, rituximab (category 2B)

• Venetoclax ± rituximab

Brexucabtagene autoleucel is suggested as third-line therapy, after chemoimmunotherapy and treatment with a BTK inhibitor.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's clinical presentation and endoscopy findings are consistent with a diagnosis of recurrent MCL presenting as a colonic mass.

MCL is an aggressive type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that accounts for approximately 5%-7% of all lymphomas. Nearly 80% of patients have extranodal involvement at initial presentation, occurring in sites such as the bone marrow, spleen, Waldeyer ring, and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Secondary GI involvement in MCL (involving nodal and/or other extranodal tissue) is common and may be detected at diagnosis and/or relapse. In several retrospective studies, the prevalence of secondary GI involvement in MCL ranged from 15% to 30%. However, in later studies, routine endoscopies in patients with untreated MCL showed GI involvement in up to 90% of patients, despite most patients not reporting GI symptoms.

The colon is the most commonly involved GI site; however, both the upper and lower GI tract from the stomach to the colon can be involved. Lymphomatous polyposis is the most common endoscopic presentation of MCL, but polyp, mass, or even normal-appearing mucosa may also be seen.

New and emerging treatment options are helping to improve survival in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL. According to National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, the preferred second-line and subsequent regimens are:

• Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors:

o Acalabrutinib

o Ibrutinib ± rituximab

o Zanubrutinib

• Lenalidomide + rituximab (if BTK inhibitor is contraindicated)

Other regimens that may be useful in certain circumstances are:

• Bendamustine + rituximab (if not previously given)

• Bendamustine + rituximab + cytarabine (RBAC500) (if not previously given)

• Bortezomib ± rituximab

• RDHA (rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine) + platinum (carboplatin, cisplatin, or oxaliplatin) (if not previously given)

• GemOx (gemcitabine, oxaliplatin) + rituximab

• Ibrutinib, lenalidomide, rituximab (category 2B)

• Ibrutinib + venetoclax

• Venetoclax, lenalidomide, rituximab (category 2B)

• Venetoclax ± rituximab

Brexucabtagene autoleucel is suggested as third-line therapy, after chemoimmunotherapy and treatment with a BTK inhibitor.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's clinical presentation and endoscopy findings are consistent with a diagnosis of recurrent MCL presenting as a colonic mass.

MCL is an aggressive type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that accounts for approximately 5%-7% of all lymphomas. Nearly 80% of patients have extranodal involvement at initial presentation, occurring in sites such as the bone marrow, spleen, Waldeyer ring, and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Secondary GI involvement in MCL (involving nodal and/or other extranodal tissue) is common and may be detected at diagnosis and/or relapse. In several retrospective studies, the prevalence of secondary GI involvement in MCL ranged from 15% to 30%. However, in later studies, routine endoscopies in patients with untreated MCL showed GI involvement in up to 90% of patients, despite most patients not reporting GI symptoms.

The colon is the most commonly involved GI site; however, both the upper and lower GI tract from the stomach to the colon can be involved. Lymphomatous polyposis is the most common endoscopic presentation of MCL, but polyp, mass, or even normal-appearing mucosa may also be seen.

New and emerging treatment options are helping to improve survival in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL. According to National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, the preferred second-line and subsequent regimens are:

• Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors:

o Acalabrutinib

o Ibrutinib ± rituximab

o Zanubrutinib

• Lenalidomide + rituximab (if BTK inhibitor is contraindicated)

Other regimens that may be useful in certain circumstances are:

• Bendamustine + rituximab (if not previously given)

• Bendamustine + rituximab + cytarabine (RBAC500) (if not previously given)

• Bortezomib ± rituximab

• RDHA (rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine) + platinum (carboplatin, cisplatin, or oxaliplatin) (if not previously given)

• GemOx (gemcitabine, oxaliplatin) + rituximab

• Ibrutinib, lenalidomide, rituximab (category 2B)

• Ibrutinib + venetoclax

• Venetoclax, lenalidomide, rituximab (category 2B)

• Venetoclax ± rituximab

Brexucabtagene autoleucel is suggested as third-line therapy, after chemoimmunotherapy and treatment with a BTK inhibitor.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 55-year-old White woman presents with complaints of left-sided abdominal pain and constipation of 10-day duration. The patient's prior medical history is notable for mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) treated 2 years earlier with RDHA (rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine) + platinum (carboplatin, cisplatin, or oxaliplatin) followed by autologous stem cell transplantation. No lymphadenopathy is noted on physical examination. Abdominal examination reveals abdominal distension, normal bowel sounds, and left lower quadrant tenderness to palpation without guarding, rigidity, or hepatosplenomegaly. Laboratory test results including CBC are within normal range. Endoscopy reveals a growth in the colon, as shown in the image.

Fatigue and sporadic fever

This patient's findings are consistent with a diagnosis of malignant mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

MCL is a rare and aggressive form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that accounts for approximately 5%-7% of all lymphomas. MCL has a characteristic immunophenotype (ie, CD5+, CD10−, Bcl-2+, Bcl-6−, CD20+), with the t(11;14)(q13;q32) chromosomal translocation, and expression of cyclin D1. The median age at diagnosis is between 60 and 70 years. Approximately 70% of all cases occur in men.

The clinical presentation of MCL can vary. Patients may have asymptomatic monoclonal MCL type lymphocytosis or nonbulky nodal/extra nodal disease with minimal symptoms, or they may present with significant symptoms, progressive generalized lymphadenopathy, cytopenia, splenomegaly, and extranodal disease, including gastrointestinal involvement (lymphomatous polyposis), kidney involvement, involvement of other organs, or, rarely, central nervous system involvement. Disease involving multiple lymph nodes and other sites of the body is seen in most patients. Approximately 70% of patients present with stage IV disease requiring systemic treatment.

According to 2022 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), essential components in the workup for MCL include:

• Physical examination, with attention to node-bearing areas, including Waldeyer ring, and to size of liver and spleen

• Assessment of performance status and B symptoms (ie, fever > 100.4°F [may be sporadic], drenching night sweats, unintentional weight loss of > 10% of body weight over 6 months or less)

• CBC with differential

• Comprehensive metabolic panel

• Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level (an important prognostic marker)

• PET/CT scan (including neck)

• Hepatitis B testing if treatment with rituximab is being contemplated

• Echocardiogram or multigated acquisition (MUGA) scan if anthracycline or anthracenedione-based regimen is indicated

• Pregnancy testing in women of childbearing age (if chemotherapy or radiation therapy is planned)

Additional testing may be indicated in specific circumstances, such as colonoscopy/endoscopy.

MCL remains challenging to treat. While 50%-90% of patients with MCL respond to combination chemotherapy, only 30% achieve a complete response. Median time to treatment failure is < 18 months.

When selecting systemic treatment for patients with MCL, clinicians should consider the availability of clinical trials for subsets of patients, eligibility for stem cell transplant (SCT), high-risk status (ie, blastoid MCL, high Ki-67% > 30%, or central nervous system involvement), age, and performance status. The addition of radiation to chemotherapy may be beneficial for patients with limited-stage, nonbulky disease, although this has not been confirmed in large, randomized studies. Outside of clinical trials, the usual approach for frontline treatment of MCL is chemoimmunotherapy with/without autologous SCT and with/without maintenance therapy.

Available options for primary MCL therapy in patients who require systemic therapy include:

• Single alkylating agents

• CVP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone)

• CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin [hydroxydaunorubicin], vincristine [Oncovin], prednisone)

• Hyper-CVAD (hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone) with or without rituximab

• R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone)

• Lenalidomide plus rituximab

• Hyper-CVAD with autologous SCT

Options for relapsed or refractory MCL include:

• R-hyper-CVAD

• Hyper-CVAD with or without rituximab followed by autologous SCT

• Nucleoside analogues and combinations

• Salvage chemotherapy combinations followed by autologous SCT

• Bortezomib

• Lenalidomide

• Ibrutinib

• Radioimmunotherapy

• Rituximab

• Rituximab and thalidomide combination

• Acalabrutinib

• High-dose chemotherapy with autologous bone marrow or SCT

• Brexucabtagene autoleucel

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's findings are consistent with a diagnosis of malignant mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

MCL is a rare and aggressive form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that accounts for approximately 5%-7% of all lymphomas. MCL has a characteristic immunophenotype (ie, CD5+, CD10−, Bcl-2+, Bcl-6−, CD20+), with the t(11;14)(q13;q32) chromosomal translocation, and expression of cyclin D1. The median age at diagnosis is between 60 and 70 years. Approximately 70% of all cases occur in men.

The clinical presentation of MCL can vary. Patients may have asymptomatic monoclonal MCL type lymphocytosis or nonbulky nodal/extra nodal disease with minimal symptoms, or they may present with significant symptoms, progressive generalized lymphadenopathy, cytopenia, splenomegaly, and extranodal disease, including gastrointestinal involvement (lymphomatous polyposis), kidney involvement, involvement of other organs, or, rarely, central nervous system involvement. Disease involving multiple lymph nodes and other sites of the body is seen in most patients. Approximately 70% of patients present with stage IV disease requiring systemic treatment.

According to 2022 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), essential components in the workup for MCL include:

• Physical examination, with attention to node-bearing areas, including Waldeyer ring, and to size of liver and spleen

• Assessment of performance status and B symptoms (ie, fever > 100.4°F [may be sporadic], drenching night sweats, unintentional weight loss of > 10% of body weight over 6 months or less)

• CBC with differential

• Comprehensive metabolic panel

• Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level (an important prognostic marker)

• PET/CT scan (including neck)

• Hepatitis B testing if treatment with rituximab is being contemplated

• Echocardiogram or multigated acquisition (MUGA) scan if anthracycline or anthracenedione-based regimen is indicated

• Pregnancy testing in women of childbearing age (if chemotherapy or radiation therapy is planned)

Additional testing may be indicated in specific circumstances, such as colonoscopy/endoscopy.

MCL remains challenging to treat. While 50%-90% of patients with MCL respond to combination chemotherapy, only 30% achieve a complete response. Median time to treatment failure is < 18 months.

When selecting systemic treatment for patients with MCL, clinicians should consider the availability of clinical trials for subsets of patients, eligibility for stem cell transplant (SCT), high-risk status (ie, blastoid MCL, high Ki-67% > 30%, or central nervous system involvement), age, and performance status. The addition of radiation to chemotherapy may be beneficial for patients with limited-stage, nonbulky disease, although this has not been confirmed in large, randomized studies. Outside of clinical trials, the usual approach for frontline treatment of MCL is chemoimmunotherapy with/without autologous SCT and with/without maintenance therapy.

Available options for primary MCL therapy in patients who require systemic therapy include:

• Single alkylating agents

• CVP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone)

• CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin [hydroxydaunorubicin], vincristine [Oncovin], prednisone)

• Hyper-CVAD (hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone) with or without rituximab

• R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone)

• Lenalidomide plus rituximab

• Hyper-CVAD with autologous SCT

Options for relapsed or refractory MCL include:

• R-hyper-CVAD

• Hyper-CVAD with or without rituximab followed by autologous SCT

• Nucleoside analogues and combinations

• Salvage chemotherapy combinations followed by autologous SCT

• Bortezomib

• Lenalidomide

• Ibrutinib

• Radioimmunotherapy

• Rituximab

• Rituximab and thalidomide combination

• Acalabrutinib

• High-dose chemotherapy with autologous bone marrow or SCT

• Brexucabtagene autoleucel

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's findings are consistent with a diagnosis of malignant mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

MCL is a rare and aggressive form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that accounts for approximately 5%-7% of all lymphomas. MCL has a characteristic immunophenotype (ie, CD5+, CD10−, Bcl-2+, Bcl-6−, CD20+), with the t(11;14)(q13;q32) chromosomal translocation, and expression of cyclin D1. The median age at diagnosis is between 60 and 70 years. Approximately 70% of all cases occur in men.

The clinical presentation of MCL can vary. Patients may have asymptomatic monoclonal MCL type lymphocytosis or nonbulky nodal/extra nodal disease with minimal symptoms, or they may present with significant symptoms, progressive generalized lymphadenopathy, cytopenia, splenomegaly, and extranodal disease, including gastrointestinal involvement (lymphomatous polyposis), kidney involvement, involvement of other organs, or, rarely, central nervous system involvement. Disease involving multiple lymph nodes and other sites of the body is seen in most patients. Approximately 70% of patients present with stage IV disease requiring systemic treatment.

According to 2022 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), essential components in the workup for MCL include:

• Physical examination, with attention to node-bearing areas, including Waldeyer ring, and to size of liver and spleen

• Assessment of performance status and B symptoms (ie, fever > 100.4°F [may be sporadic], drenching night sweats, unintentional weight loss of > 10% of body weight over 6 months or less)

• CBC with differential

• Comprehensive metabolic panel

• Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level (an important prognostic marker)

• PET/CT scan (including neck)

• Hepatitis B testing if treatment with rituximab is being contemplated

• Echocardiogram or multigated acquisition (MUGA) scan if anthracycline or anthracenedione-based regimen is indicated

• Pregnancy testing in women of childbearing age (if chemotherapy or radiation therapy is planned)

Additional testing may be indicated in specific circumstances, such as colonoscopy/endoscopy.

MCL remains challenging to treat. While 50%-90% of patients with MCL respond to combination chemotherapy, only 30% achieve a complete response. Median time to treatment failure is < 18 months.

When selecting systemic treatment for patients with MCL, clinicians should consider the availability of clinical trials for subsets of patients, eligibility for stem cell transplant (SCT), high-risk status (ie, blastoid MCL, high Ki-67% > 30%, or central nervous system involvement), age, and performance status. The addition of radiation to chemotherapy may be beneficial for patients with limited-stage, nonbulky disease, although this has not been confirmed in large, randomized studies. Outside of clinical trials, the usual approach for frontline treatment of MCL is chemoimmunotherapy with/without autologous SCT and with/without maintenance therapy.

Available options for primary MCL therapy in patients who require systemic therapy include:

• Single alkylating agents

• CVP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone)

• CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin [hydroxydaunorubicin], vincristine [Oncovin], prednisone)

• Hyper-CVAD (hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone) with or without rituximab

• R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone)

• Lenalidomide plus rituximab

• Hyper-CVAD with autologous SCT

Options for relapsed or refractory MCL include:

• R-hyper-CVAD

• Hyper-CVAD with or without rituximab followed by autologous SCT

• Nucleoside analogues and combinations

• Salvage chemotherapy combinations followed by autologous SCT

• Bortezomib

• Lenalidomide

• Ibrutinib

• Radioimmunotherapy

• Rituximab

• Rituximab and thalidomide combination

• Acalabrutinib

• High-dose chemotherapy with autologous bone marrow or SCT

• Brexucabtagene autoleucel

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 64-year-old Black man with a history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia presents with complaints of fatigue, sporadic fever > 100.4° F, and mild abdominal pain. The patient has lost 12 lb since he was last seen 9 months earlier. When questioned, he states that he simply doesn't have the appetite he once had. Physical examination reveals pallor; abdominal distension; lymphadenopathy in the anterior cervical, inguinal, and axillary regions; and palpable spleen and liver. CBC findings include RBC 4.4 x 106/µL; WBC 2400/μL; PLT 148,000/dL; MCV 57.8 fL; hematocrit 38%; and ALC 4200/µL. Immunophenotyping by flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry was positive for CD5 and CD19, with no expression of CD10 or CD23. Cyclin D1 was overexpressed.