User login

Working Out Works Well in Asthma

ORLANDO – People with asthma who engaged in a structured exercise program had sustained quality-of-life improvements, a small study has shown.

Although exercise is often anathema to people with asthma, previously sedentary people with asthma who were randomized in a small study to engage in three exercise sessions per week reported a twofold greater improvement in their symptom-related quality of life, compared with those who did not increase their routine exercise, reported Dr. Thomas Platts-Mills, professor of medicine, allergy, and clinical immunology at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

The preliminary study was designed to convince health insurers to fund structured exercise programs in commercial gyms for patients with asthma, Dr. Platts-Mills said.

"You’ve got three obstacles to overcome: one is that the patients think that it’s a problem having to do exercise, because it will make their asthma worse," he noted. "Secondly, the gym may be resistant, because they think they’ll have asthma attacks to deal with; and third, the insurance companies are resistant, period."

The investigators recruited from a local commercial health plan 13 patients with persistent asthma as defined by National Asthma Education and Prevention Program guidelines. The participants were all treated with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and leukotriene agents that were on the health plan’s formulary.

All 13 patients were identified as engaging in no or little exercise (fewer than two sessions of aerobic activity per week over the past 6 months). Patients who participated more than 3 hours per week in any kind of moderate-level physical activity were excluded, as were patients with active pulmonary infections, cardiovascular disease, musculoskeletal disease, or other conditions that might impair their ability to exercise.

The authors convinced the insurer to pay a gym to enroll plan members with asthma, and they helped gym staff establish an asthma protocol that included monitoring asthmatics for symptoms and providing access to nebulizers.

"The gyms, we hope, will want to do this, and it’s very much in the insurance company’s favor to do it," Dr. Platts-Mills said. "But it’s still very difficult to get people to do regular exercise."

The seven participants assigned to the exercise group kept an exercise log recording the duration, type, and perceived exertion of all physical activities, including the three assigned exercise sessions each week. They also kept a log of medication use, asthma symptoms, unplanned medical visits, and unplanned asthma-related absences from work or school. Participants also answered a telephone-based asthma quality of life questionnaire at the end of weeks 4, 8, 12 and 16 (the study’s end).

Six participants assigned to be controls were given educational materials on exercise, participated in the telephone survey, and kept logs recording the same information as that of the exercise group. Researchers crossed over those participants to the exercise arm at 4 months.

At week 8, scores on the symptom domain of the quality-of-life questionnaire were significantly higher among exercisers, with 78.3% of responses indicating improvement, compared with 39.5% of responses by participants in the delayed-exercise group (P = .05).

Similarly, on the activity limitations domain, 78.3% of responding exercisers said they saw improvement, compared with 37.2% of delayed exercisers (P = .036). There were trends favoring exercise, but no significant differences, in the emotional function and environmental stimuli domains of the quality-of-life questionnaire.

"We have established that you can get an insurance company to pay a gym to enroll people and establish a protocol in the gym for asthmatics," Dr. Platts-Mills said. "I think this would be far more important for children with asthma if this could be achieved."

The study was supported by Southern Health Services Inc. Dr. Platts-Mills and colleagues reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – People with asthma who engaged in a structured exercise program had sustained quality-of-life improvements, a small study has shown.

Although exercise is often anathema to people with asthma, previously sedentary people with asthma who were randomized in a small study to engage in three exercise sessions per week reported a twofold greater improvement in their symptom-related quality of life, compared with those who did not increase their routine exercise, reported Dr. Thomas Platts-Mills, professor of medicine, allergy, and clinical immunology at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

The preliminary study was designed to convince health insurers to fund structured exercise programs in commercial gyms for patients with asthma, Dr. Platts-Mills said.

"You’ve got three obstacles to overcome: one is that the patients think that it’s a problem having to do exercise, because it will make their asthma worse," he noted. "Secondly, the gym may be resistant, because they think they’ll have asthma attacks to deal with; and third, the insurance companies are resistant, period."

The investigators recruited from a local commercial health plan 13 patients with persistent asthma as defined by National Asthma Education and Prevention Program guidelines. The participants were all treated with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and leukotriene agents that were on the health plan’s formulary.

All 13 patients were identified as engaging in no or little exercise (fewer than two sessions of aerobic activity per week over the past 6 months). Patients who participated more than 3 hours per week in any kind of moderate-level physical activity were excluded, as were patients with active pulmonary infections, cardiovascular disease, musculoskeletal disease, or other conditions that might impair their ability to exercise.

The authors convinced the insurer to pay a gym to enroll plan members with asthma, and they helped gym staff establish an asthma protocol that included monitoring asthmatics for symptoms and providing access to nebulizers.

"The gyms, we hope, will want to do this, and it’s very much in the insurance company’s favor to do it," Dr. Platts-Mills said. "But it’s still very difficult to get people to do regular exercise."

The seven participants assigned to the exercise group kept an exercise log recording the duration, type, and perceived exertion of all physical activities, including the three assigned exercise sessions each week. They also kept a log of medication use, asthma symptoms, unplanned medical visits, and unplanned asthma-related absences from work or school. Participants also answered a telephone-based asthma quality of life questionnaire at the end of weeks 4, 8, 12 and 16 (the study’s end).

Six participants assigned to be controls were given educational materials on exercise, participated in the telephone survey, and kept logs recording the same information as that of the exercise group. Researchers crossed over those participants to the exercise arm at 4 months.

At week 8, scores on the symptom domain of the quality-of-life questionnaire were significantly higher among exercisers, with 78.3% of responses indicating improvement, compared with 39.5% of responses by participants in the delayed-exercise group (P = .05).

Similarly, on the activity limitations domain, 78.3% of responding exercisers said they saw improvement, compared with 37.2% of delayed exercisers (P = .036). There were trends favoring exercise, but no significant differences, in the emotional function and environmental stimuli domains of the quality-of-life questionnaire.

"We have established that you can get an insurance company to pay a gym to enroll people and establish a protocol in the gym for asthmatics," Dr. Platts-Mills said. "I think this would be far more important for children with asthma if this could be achieved."

The study was supported by Southern Health Services Inc. Dr. Platts-Mills and colleagues reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – People with asthma who engaged in a structured exercise program had sustained quality-of-life improvements, a small study has shown.

Although exercise is often anathema to people with asthma, previously sedentary people with asthma who were randomized in a small study to engage in three exercise sessions per week reported a twofold greater improvement in their symptom-related quality of life, compared with those who did not increase their routine exercise, reported Dr. Thomas Platts-Mills, professor of medicine, allergy, and clinical immunology at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

The preliminary study was designed to convince health insurers to fund structured exercise programs in commercial gyms for patients with asthma, Dr. Platts-Mills said.

"You’ve got three obstacles to overcome: one is that the patients think that it’s a problem having to do exercise, because it will make their asthma worse," he noted. "Secondly, the gym may be resistant, because they think they’ll have asthma attacks to deal with; and third, the insurance companies are resistant, period."

The investigators recruited from a local commercial health plan 13 patients with persistent asthma as defined by National Asthma Education and Prevention Program guidelines. The participants were all treated with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and leukotriene agents that were on the health plan’s formulary.

All 13 patients were identified as engaging in no or little exercise (fewer than two sessions of aerobic activity per week over the past 6 months). Patients who participated more than 3 hours per week in any kind of moderate-level physical activity were excluded, as were patients with active pulmonary infections, cardiovascular disease, musculoskeletal disease, or other conditions that might impair their ability to exercise.

The authors convinced the insurer to pay a gym to enroll plan members with asthma, and they helped gym staff establish an asthma protocol that included monitoring asthmatics for symptoms and providing access to nebulizers.

"The gyms, we hope, will want to do this, and it’s very much in the insurance company’s favor to do it," Dr. Platts-Mills said. "But it’s still very difficult to get people to do regular exercise."

The seven participants assigned to the exercise group kept an exercise log recording the duration, type, and perceived exertion of all physical activities, including the three assigned exercise sessions each week. They also kept a log of medication use, asthma symptoms, unplanned medical visits, and unplanned asthma-related absences from work or school. Participants also answered a telephone-based asthma quality of life questionnaire at the end of weeks 4, 8, 12 and 16 (the study’s end).

Six participants assigned to be controls were given educational materials on exercise, participated in the telephone survey, and kept logs recording the same information as that of the exercise group. Researchers crossed over those participants to the exercise arm at 4 months.

At week 8, scores on the symptom domain of the quality-of-life questionnaire were significantly higher among exercisers, with 78.3% of responses indicating improvement, compared with 39.5% of responses by participants in the delayed-exercise group (P = .05).

Similarly, on the activity limitations domain, 78.3% of responding exercisers said they saw improvement, compared with 37.2% of delayed exercisers (P = .036). There were trends favoring exercise, but no significant differences, in the emotional function and environmental stimuli domains of the quality-of-life questionnaire.

"We have established that you can get an insurance company to pay a gym to enroll people and establish a protocol in the gym for asthmatics," Dr. Platts-Mills said. "I think this would be far more important for children with asthma if this could be achieved."

The study was supported by Southern Health Services Inc. Dr. Platts-Mills and colleagues reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ALLERGY, ASTHMA, AND IMMUNOLOGY

Major Finding: At week 8, scores on the symptom domain of an asthma quality-of-life questionnaire were significantly higher among exercisers, with 78.3% of responses indicating improvement, compared with 39.5% of responses by nonexercising controls (P = .05).

Data Source: This was a randomized study.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Southern Health Services Inc. Dr. Platts-Mills and colleagues reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

Schools Tackle Socioeconomic Gap in Asthma Control

ORLANDO – Adding asthma education to reading, writing, and arithmetic in public schools resulted in significant improvements in asthma control measures among at-risk children, researchers reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Children in the intervention group also had fewer urgent-care visits, suggesting better asthma control, the authors found.

In a pilot study aimed at reducing socioeconomic disparities in asthma control, at-risk children from schools assigned to implement the American Lung Association’s Open Airways for Schools (OAS) program had significantly better activity quality-of-life (QoL) scores and demonstrated significantly greater improvements in the use of metered-dose inhalers (MDI) than did their peers in schools that did not receive the intervention, reported Dr. Summer Monforte, a second-year fellow at National Jewish Health in Denver.

The study’s senior author was Dr. Stanley J. Szefler, head of pediatric clinical pharmacology at National Jewish Health.

The improvement in MDI use is an indicator that such programs can help to improve the health of children who are at risk for poor asthma outcomes, Dr. Monforte said in an interview.

"Every single time a child comes in, you have to make sure that they take their inhaler correctly; so it’s nice when the medicine gets where it’s supposed to go," she said.

The overall asthma prevalence rate in Colorado is 8.5% – but in some inner-city schools, the rate is nearly three times higher (22.8%). School-based asthma-education programs can help children improve their asthma control and avoid or reduce exacerbations, but such programs are not always available in poorer urban districts, the investigators noted.

They conducted a randomized, controlled study to see whether the evidence-based OAS intervention would work in schools where children were at risk for health care disparities. At-risk schools were defined as those in which more than 75% of children qualified for free lunch programs, or those with a greater than 50% Hispanic or African American student population.

Four of the schools (with a total of 49 children with asthma, plus their parents or guardians) were randomized to receive the intervention, and four other schools (total of 43 asthmatic children) were assigned as controls. All participants had a visit at baseline and at 3 months’ follow-up.

The children in the intervention groups attended a 40-minute OAS session once weekly for 6 weeks, while controls received their usual care.

At baseline, children in both groups were evaluated with the Health Risk Assessment instrument. Children in both groups also were assessed at baseline and follow-up with the Asthma Control Test (ACT) or Childhood ACT, asthma history questionnaires, Juniper’s Pediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire and Caregiver Quality of Life tools, spirometry, and observation and assessment of inhaler technique.

At 3-month follow-up, children in the intervention group had a mean improvement of 0.8 (plus or minus .22) points on the activity subscale of the QoL scale, which is scored from 1 (worst) to 7 (best). In comparison, controls had a mean improvement of only 0.2 (plus or minus 1.7) points (P = .05).

Assessments of MDI technique showed that children in the intervention group improved by a mean of 2.3 points on a 5-point scale, compared with just 0.7 for controls (P less than .0001).

The authors noted that this was a pilot study of short duration, with limited enrollment attributable to insufficient funding.

Nonetheless, the results indicate that a proven intervention "can be implemented with minor modifications in populations, such as the Denver Public Schools, that differ from the population where it was originally developed," the researchers noted in a poster presentation at the meeting.

The Step Up asthma program, a collaboration between National Jewish Health and the Denver Public Schools, was designed based on the needs identified in the pilot study, and is currently in place. The investigators plan to evaluate its ability to improve asthma control over a 5-year period.

GlaxoSmithKline supported the study. Dr. Monforte reported that she had no relevant disclosures.

ORLANDO – Adding asthma education to reading, writing, and arithmetic in public schools resulted in significant improvements in asthma control measures among at-risk children, researchers reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Children in the intervention group also had fewer urgent-care visits, suggesting better asthma control, the authors found.

In a pilot study aimed at reducing socioeconomic disparities in asthma control, at-risk children from schools assigned to implement the American Lung Association’s Open Airways for Schools (OAS) program had significantly better activity quality-of-life (QoL) scores and demonstrated significantly greater improvements in the use of metered-dose inhalers (MDI) than did their peers in schools that did not receive the intervention, reported Dr. Summer Monforte, a second-year fellow at National Jewish Health in Denver.

The study’s senior author was Dr. Stanley J. Szefler, head of pediatric clinical pharmacology at National Jewish Health.

The improvement in MDI use is an indicator that such programs can help to improve the health of children who are at risk for poor asthma outcomes, Dr. Monforte said in an interview.

"Every single time a child comes in, you have to make sure that they take their inhaler correctly; so it’s nice when the medicine gets where it’s supposed to go," she said.

The overall asthma prevalence rate in Colorado is 8.5% – but in some inner-city schools, the rate is nearly three times higher (22.8%). School-based asthma-education programs can help children improve their asthma control and avoid or reduce exacerbations, but such programs are not always available in poorer urban districts, the investigators noted.

They conducted a randomized, controlled study to see whether the evidence-based OAS intervention would work in schools where children were at risk for health care disparities. At-risk schools were defined as those in which more than 75% of children qualified for free lunch programs, or those with a greater than 50% Hispanic or African American student population.

Four of the schools (with a total of 49 children with asthma, plus their parents or guardians) were randomized to receive the intervention, and four other schools (total of 43 asthmatic children) were assigned as controls. All participants had a visit at baseline and at 3 months’ follow-up.

The children in the intervention groups attended a 40-minute OAS session once weekly for 6 weeks, while controls received their usual care.

At baseline, children in both groups were evaluated with the Health Risk Assessment instrument. Children in both groups also were assessed at baseline and follow-up with the Asthma Control Test (ACT) or Childhood ACT, asthma history questionnaires, Juniper’s Pediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire and Caregiver Quality of Life tools, spirometry, and observation and assessment of inhaler technique.

At 3-month follow-up, children in the intervention group had a mean improvement of 0.8 (plus or minus .22) points on the activity subscale of the QoL scale, which is scored from 1 (worst) to 7 (best). In comparison, controls had a mean improvement of only 0.2 (plus or minus 1.7) points (P = .05).

Assessments of MDI technique showed that children in the intervention group improved by a mean of 2.3 points on a 5-point scale, compared with just 0.7 for controls (P less than .0001).

The authors noted that this was a pilot study of short duration, with limited enrollment attributable to insufficient funding.

Nonetheless, the results indicate that a proven intervention "can be implemented with minor modifications in populations, such as the Denver Public Schools, that differ from the population where it was originally developed," the researchers noted in a poster presentation at the meeting.

The Step Up asthma program, a collaboration between National Jewish Health and the Denver Public Schools, was designed based on the needs identified in the pilot study, and is currently in place. The investigators plan to evaluate its ability to improve asthma control over a 5-year period.

GlaxoSmithKline supported the study. Dr. Monforte reported that she had no relevant disclosures.

ORLANDO – Adding asthma education to reading, writing, and arithmetic in public schools resulted in significant improvements in asthma control measures among at-risk children, researchers reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Children in the intervention group also had fewer urgent-care visits, suggesting better asthma control, the authors found.

In a pilot study aimed at reducing socioeconomic disparities in asthma control, at-risk children from schools assigned to implement the American Lung Association’s Open Airways for Schools (OAS) program had significantly better activity quality-of-life (QoL) scores and demonstrated significantly greater improvements in the use of metered-dose inhalers (MDI) than did their peers in schools that did not receive the intervention, reported Dr. Summer Monforte, a second-year fellow at National Jewish Health in Denver.

The study’s senior author was Dr. Stanley J. Szefler, head of pediatric clinical pharmacology at National Jewish Health.

The improvement in MDI use is an indicator that such programs can help to improve the health of children who are at risk for poor asthma outcomes, Dr. Monforte said in an interview.

"Every single time a child comes in, you have to make sure that they take their inhaler correctly; so it’s nice when the medicine gets where it’s supposed to go," she said.

The overall asthma prevalence rate in Colorado is 8.5% – but in some inner-city schools, the rate is nearly three times higher (22.8%). School-based asthma-education programs can help children improve their asthma control and avoid or reduce exacerbations, but such programs are not always available in poorer urban districts, the investigators noted.

They conducted a randomized, controlled study to see whether the evidence-based OAS intervention would work in schools where children were at risk for health care disparities. At-risk schools were defined as those in which more than 75% of children qualified for free lunch programs, or those with a greater than 50% Hispanic or African American student population.

Four of the schools (with a total of 49 children with asthma, plus their parents or guardians) were randomized to receive the intervention, and four other schools (total of 43 asthmatic children) were assigned as controls. All participants had a visit at baseline and at 3 months’ follow-up.

The children in the intervention groups attended a 40-minute OAS session once weekly for 6 weeks, while controls received their usual care.

At baseline, children in both groups were evaluated with the Health Risk Assessment instrument. Children in both groups also were assessed at baseline and follow-up with the Asthma Control Test (ACT) or Childhood ACT, asthma history questionnaires, Juniper’s Pediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire and Caregiver Quality of Life tools, spirometry, and observation and assessment of inhaler technique.

At 3-month follow-up, children in the intervention group had a mean improvement of 0.8 (plus or minus .22) points on the activity subscale of the QoL scale, which is scored from 1 (worst) to 7 (best). In comparison, controls had a mean improvement of only 0.2 (plus or minus 1.7) points (P = .05).

Assessments of MDI technique showed that children in the intervention group improved by a mean of 2.3 points on a 5-point scale, compared with just 0.7 for controls (P less than .0001).

The authors noted that this was a pilot study of short duration, with limited enrollment attributable to insufficient funding.

Nonetheless, the results indicate that a proven intervention "can be implemented with minor modifications in populations, such as the Denver Public Schools, that differ from the population where it was originally developed," the researchers noted in a poster presentation at the meeting.

The Step Up asthma program, a collaboration between National Jewish Health and the Denver Public Schools, was designed based on the needs identified in the pilot study, and is currently in place. The investigators plan to evaluate its ability to improve asthma control over a 5-year period.

GlaxoSmithKline supported the study. Dr. Monforte reported that she had no relevant disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ALLERGY, ASTHMA, AND IMMUNOLOGY

Major Finding: Children assigned to a school-based asthma education program had significant improvements compared with controls in activity-related quality of life scores (0.8 vs. 0.2 on a 7-point scale, P = .05), and in metered-dose inhaler use (2.3 vs. 0.7 points on a 5-point scale, P less than .0001)

Data Source: This was a randomized, controlled study of an asthma education program.

Disclosures: The study was supported by GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Monforte reported that she had no relevant disclosures.

Farm Living Linked to Low Asthma Prevalence

ORLANDO – Amish farms appear to be havens of peace and contentment, free from the insults of modern life – including, it appears, inhalant allergies and asthma, researchers reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

A study comparing asthma and allergic rhinitis prevalence among Amish children in the United States with those of Swiss children living both on and off farms shows that asthma prevalence among the Amish is low and similar to that of children living on Swiss farms, lending further support to the hygiene hypothesis of allergy and asthma, said Dr. Mark Holbreich of Allergy & Asthma Consultants in Indianapolis.

Only 8 (5%) of 157 in a sample of Amish children had ever received a diagnosis of asthma, and only 1 (0.6%) had ever been diagnosed with hay fever. Swiss farm children had similarly low prevalence levels, with 202 (6.7%) of 3,006 having ever been diagnosed with asthma, and 94 (3.1%) with allergy. In contrast, 1,218 (11.2%) of 10,912 Swiss non–farm dwelling children had been diagnosed with asthma, and 1,259 (11.6%) had a hay fever diagnosis at some point in their lives.

"This study clearly supports the effect of early farm exposures in reducing allergic sensitization," said Dr. Holbreich.

Although the sample of Amish children was too small to determine whether specific factors were protective in farm dwellers both in the United States and Europe, multivariate analyses from other studies suggest that drinking raw, unpasteurized milk, and child and maternal exposure to large animals (especially cows) during pregnancy may confer immune tolerance on the child, Dr. Holbreich said in an interview.

The investigators chose for their comparison group Swiss children aged 6-12 years enrolled in the phase I GABRIEL study, which looked at genetic and environmental causes of asthma in Europe. A stratified sample of these children had undergone serum specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) testing to inhalant allergens, including house dust mites (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus), cat, birch, mixed trees, and grasses. The GABRIEL investigators defined atopy as any positive IgE level of 0.7 kU/L or greater.

Dr. Holbreich and his colleagues distributed to the families of Amish school children a modified GABRIEL questionnaire, and invited consenting children to a skin test session at the school. The children were tested for skin-prick response to D. pteronyssinus, D. farinae, grass mix, tree mix, ragweed, cat, horse, and Alternaria. They considered a skin prick test positive if it induced a 3-mm or greater wheal after subtraction of the negative control.

Although the testing methods were different between the groups (skin-prick testing for the Amish children, and IgE for the Swiss children), the investigators are confident that the prevalence results are valid, Dr. Holbreich said.

Dust mites were the common offenders in causing atopy among the Amish children (5.8%), with sensitivity to mixed grasses occurring in 2.9%. In contrast, 20.1% of Swiss farm dwelling children, and 39.8% of children who did not live on farms had grass sensitivity, with dust mite sensitivity coming in second (9.3% and 16.4%, respectively), and with birch being the third most common allergen (80% and 19.6%, respectively).

Asked in the question-and-response portion of his presentation whether helminth infections might play a role in allergic desensitization of the Amish children, Dr. Holbreich noted that the Amish people "live a very traditional lifestyle, but they see doctors, they get all their immunizations, and they’re cleanly, and I’m not aware of data [showing] that Amish get helminth infections, so I don’t think that is a factor."

The study was supported by the St. Vincent Foundation, AAAAI, and the European Commission. Dr. Holbreich reported having no conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – Amish farms appear to be havens of peace and contentment, free from the insults of modern life – including, it appears, inhalant allergies and asthma, researchers reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

A study comparing asthma and allergic rhinitis prevalence among Amish children in the United States with those of Swiss children living both on and off farms shows that asthma prevalence among the Amish is low and similar to that of children living on Swiss farms, lending further support to the hygiene hypothesis of allergy and asthma, said Dr. Mark Holbreich of Allergy & Asthma Consultants in Indianapolis.

Only 8 (5%) of 157 in a sample of Amish children had ever received a diagnosis of asthma, and only 1 (0.6%) had ever been diagnosed with hay fever. Swiss farm children had similarly low prevalence levels, with 202 (6.7%) of 3,006 having ever been diagnosed with asthma, and 94 (3.1%) with allergy. In contrast, 1,218 (11.2%) of 10,912 Swiss non–farm dwelling children had been diagnosed with asthma, and 1,259 (11.6%) had a hay fever diagnosis at some point in their lives.

"This study clearly supports the effect of early farm exposures in reducing allergic sensitization," said Dr. Holbreich.

Although the sample of Amish children was too small to determine whether specific factors were protective in farm dwellers both in the United States and Europe, multivariate analyses from other studies suggest that drinking raw, unpasteurized milk, and child and maternal exposure to large animals (especially cows) during pregnancy may confer immune tolerance on the child, Dr. Holbreich said in an interview.

The investigators chose for their comparison group Swiss children aged 6-12 years enrolled in the phase I GABRIEL study, which looked at genetic and environmental causes of asthma in Europe. A stratified sample of these children had undergone serum specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) testing to inhalant allergens, including house dust mites (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus), cat, birch, mixed trees, and grasses. The GABRIEL investigators defined atopy as any positive IgE level of 0.7 kU/L or greater.

Dr. Holbreich and his colleagues distributed to the families of Amish school children a modified GABRIEL questionnaire, and invited consenting children to a skin test session at the school. The children were tested for skin-prick response to D. pteronyssinus, D. farinae, grass mix, tree mix, ragweed, cat, horse, and Alternaria. They considered a skin prick test positive if it induced a 3-mm or greater wheal after subtraction of the negative control.

Although the testing methods were different between the groups (skin-prick testing for the Amish children, and IgE for the Swiss children), the investigators are confident that the prevalence results are valid, Dr. Holbreich said.

Dust mites were the common offenders in causing atopy among the Amish children (5.8%), with sensitivity to mixed grasses occurring in 2.9%. In contrast, 20.1% of Swiss farm dwelling children, and 39.8% of children who did not live on farms had grass sensitivity, with dust mite sensitivity coming in second (9.3% and 16.4%, respectively), and with birch being the third most common allergen (80% and 19.6%, respectively).

Asked in the question-and-response portion of his presentation whether helminth infections might play a role in allergic desensitization of the Amish children, Dr. Holbreich noted that the Amish people "live a very traditional lifestyle, but they see doctors, they get all their immunizations, and they’re cleanly, and I’m not aware of data [showing] that Amish get helminth infections, so I don’t think that is a factor."

The study was supported by the St. Vincent Foundation, AAAAI, and the European Commission. Dr. Holbreich reported having no conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – Amish farms appear to be havens of peace and contentment, free from the insults of modern life – including, it appears, inhalant allergies and asthma, researchers reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

A study comparing asthma and allergic rhinitis prevalence among Amish children in the United States with those of Swiss children living both on and off farms shows that asthma prevalence among the Amish is low and similar to that of children living on Swiss farms, lending further support to the hygiene hypothesis of allergy and asthma, said Dr. Mark Holbreich of Allergy & Asthma Consultants in Indianapolis.

Only 8 (5%) of 157 in a sample of Amish children had ever received a diagnosis of asthma, and only 1 (0.6%) had ever been diagnosed with hay fever. Swiss farm children had similarly low prevalence levels, with 202 (6.7%) of 3,006 having ever been diagnosed with asthma, and 94 (3.1%) with allergy. In contrast, 1,218 (11.2%) of 10,912 Swiss non–farm dwelling children had been diagnosed with asthma, and 1,259 (11.6%) had a hay fever diagnosis at some point in their lives.

"This study clearly supports the effect of early farm exposures in reducing allergic sensitization," said Dr. Holbreich.

Although the sample of Amish children was too small to determine whether specific factors were protective in farm dwellers both in the United States and Europe, multivariate analyses from other studies suggest that drinking raw, unpasteurized milk, and child and maternal exposure to large animals (especially cows) during pregnancy may confer immune tolerance on the child, Dr. Holbreich said in an interview.

The investigators chose for their comparison group Swiss children aged 6-12 years enrolled in the phase I GABRIEL study, which looked at genetic and environmental causes of asthma in Europe. A stratified sample of these children had undergone serum specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) testing to inhalant allergens, including house dust mites (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus), cat, birch, mixed trees, and grasses. The GABRIEL investigators defined atopy as any positive IgE level of 0.7 kU/L or greater.

Dr. Holbreich and his colleagues distributed to the families of Amish school children a modified GABRIEL questionnaire, and invited consenting children to a skin test session at the school. The children were tested for skin-prick response to D. pteronyssinus, D. farinae, grass mix, tree mix, ragweed, cat, horse, and Alternaria. They considered a skin prick test positive if it induced a 3-mm or greater wheal after subtraction of the negative control.

Although the testing methods were different between the groups (skin-prick testing for the Amish children, and IgE for the Swiss children), the investigators are confident that the prevalence results are valid, Dr. Holbreich said.

Dust mites were the common offenders in causing atopy among the Amish children (5.8%), with sensitivity to mixed grasses occurring in 2.9%. In contrast, 20.1% of Swiss farm dwelling children, and 39.8% of children who did not live on farms had grass sensitivity, with dust mite sensitivity coming in second (9.3% and 16.4%, respectively), and with birch being the third most common allergen (80% and 19.6%, respectively).

Asked in the question-and-response portion of his presentation whether helminth infections might play a role in allergic desensitization of the Amish children, Dr. Holbreich noted that the Amish people "live a very traditional lifestyle, but they see doctors, they get all their immunizations, and they’re cleanly, and I’m not aware of data [showing] that Amish get helminth infections, so I don’t think that is a factor."

The study was supported by the St. Vincent Foundation, AAAAI, and the European Commission. Dr. Holbreich reported having no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ALLERGY, ASTHMA, AND IMMUNOLOGY

Major Finding: Only 5.2% of a sample of Amish children had ever received a diagnosis of asthma, and only 0.6% had ever been diagnosed with hay fever. The levels were similar to those of Swiss children living on a farm (6.8% and 3.1%, respectively), and much lower than those of Swiss children not living on a farm (11.2% and 11.6%, respectively).

Data Source: This was a comparison cohort study.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the St. Vincent Foundation of Indianapolis, AAAAI, and the European Commission. Dr. Holbreich reported having no conflicts of interest.

Sublingual Pollen Pill Delivered Durable Allergy Relief

ORLANDO – Patients who underwent 3 consecutive years of desensitization to grass pollen with seasonal use of a daily, sublingual pill maintained their reduced level of grass pollen allergy during the following fourth season despite stopping pill treatment, according to results from a study of 432 patients who stayed in the study for 4 years.

The findings provide the first evidence that sublingual desensitization produces allergy disease modification similar to subcutaneous desensitization, Dr. Hans-Jørgen Malling said during a poster presentation March 4 at the meeting.

"The data show sustained clinical efficacy when you stop treatment," said Dr. Malling, professor of medicine at the University of Copenhagen and chief of the allergy clinic at Gentofte Hospital in nearby Hellerup. "That is disease modifying. If there is no efficacy after you stop treatment, then this treatment will not be viable."

Although long-term efficacy is crucial, "up to now, it seems like sublingual is equivalent to subcutaneous," he said in an interview.

But Dr. Malling also cautioned that a major test will be the ability of sublingual desensitization to maintain allergy desensitization during a second year off treatment – results that will come during the fifth and final year of the study and will be available a year from now.

Prior reports from the current study documented the ability of the sublingual grass pollen pill to produce desensitization in adult patients during each of the 3 years of active treatment (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011;128:559-66).

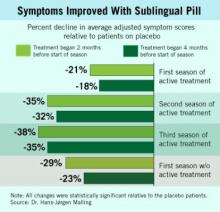

During the first 3 years, the oral desensitization regimen led to progressively higher levels of symptom reduction each year, compared with placebo, a pattern that mimicked what typically occurs with subcutaneous desensitization.

The new results showed that during patients’ first year off active treatment, symptom relief showed a trend toward a small dip in efficacy (see box), compared with placebo, although patients also self reported a maintained, positive effect on their total quality of life scores.

During the first year off treatment, the average adjusted symptom score (the study’s primary end point) was 29% below the placebo level among 136 patients who both took the pill starting 2 months before the start of their allergy season and remained in the study. The symptom score was 23% below placebo among the 142 patients who took the pill starting 4 months before the start of their allergy season and remained in the study.

The study initially randomized 633 adult patients with grass pollen allergy at several European centers. Patients began receiving either the active desensitization tablet or placebo at 2 months or 4 months before the onset of their local grass pollen season, and continued daily treatment through the end of the local pollen season. They then resumed the same treatment schedule during the subsequent 2 years. By the end of the fourth year of the study, roughly two-thirds of the initially enrolled patients remained in the study.

The most common adverse effect during treatment was mouth pruritus, followed by throat irritation. All of the adverse effects were mild or moderate, and their incidence and severity steadily declined during the 3 years of active treatment.

No patients in the study had an anaphylactic reaction, unlike what occurs with subcutaneous injections, which are know to cause anaphylaxis occasionally. The entire worldwide experience with the sublingual grass pollen tablet has so far resulted in six episodes of "doubtful" anaphylaxis, an experience that led Dr. Malling to declare that the sublingual tablet "is safer" than subcutaneous injections.

"For some patients, [sublingual] is probably optimal, while for others subcutaneous will be better," Dr. Malling said. Having both options available gives patients a choice of disease-modifying therapy. One advantage of the sublingual tablet is that it precludes the need for patients to travel to a physician’s office for regular injections, he noted, although being on a schedule of regular injections helps ensure compliance.

Stallergenes developed the sublingual tablet, and has marketed it as Oralair in Europe since 2009. The tablet contains pollen extracts from five grass types that are common throughout Europe.

A pivotal trial of the formulation is in progress in the United States, but has not yet progressed to the stage where patients have stopped active, seasonal treatment. Other companies are also conducting clinical trials to test the efficacy and safety of sublingual desensitization tablets for grass pollen and for other allergens. The new results reported by Dr. Malling and his associates are the first to report what happens once patients stop active, annual treatment.

The study was sponsored by Stallergenes, the company that markets the sublingual grass pollen tablet as Oralair. Dr. Malling said that he is a consultant to and has received research support from Stallergenes and from several other drug companies.

ORLANDO – Patients who underwent 3 consecutive years of desensitization to grass pollen with seasonal use of a daily, sublingual pill maintained their reduced level of grass pollen allergy during the following fourth season despite stopping pill treatment, according to results from a study of 432 patients who stayed in the study for 4 years.

The findings provide the first evidence that sublingual desensitization produces allergy disease modification similar to subcutaneous desensitization, Dr. Hans-Jørgen Malling said during a poster presentation March 4 at the meeting.

"The data show sustained clinical efficacy when you stop treatment," said Dr. Malling, professor of medicine at the University of Copenhagen and chief of the allergy clinic at Gentofte Hospital in nearby Hellerup. "That is disease modifying. If there is no efficacy after you stop treatment, then this treatment will not be viable."

Although long-term efficacy is crucial, "up to now, it seems like sublingual is equivalent to subcutaneous," he said in an interview.

But Dr. Malling also cautioned that a major test will be the ability of sublingual desensitization to maintain allergy desensitization during a second year off treatment – results that will come during the fifth and final year of the study and will be available a year from now.

Prior reports from the current study documented the ability of the sublingual grass pollen pill to produce desensitization in adult patients during each of the 3 years of active treatment (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011;128:559-66).

During the first 3 years, the oral desensitization regimen led to progressively higher levels of symptom reduction each year, compared with placebo, a pattern that mimicked what typically occurs with subcutaneous desensitization.

The new results showed that during patients’ first year off active treatment, symptom relief showed a trend toward a small dip in efficacy (see box), compared with placebo, although patients also self reported a maintained, positive effect on their total quality of life scores.

During the first year off treatment, the average adjusted symptom score (the study’s primary end point) was 29% below the placebo level among 136 patients who both took the pill starting 2 months before the start of their allergy season and remained in the study. The symptom score was 23% below placebo among the 142 patients who took the pill starting 4 months before the start of their allergy season and remained in the study.

The study initially randomized 633 adult patients with grass pollen allergy at several European centers. Patients began receiving either the active desensitization tablet or placebo at 2 months or 4 months before the onset of their local grass pollen season, and continued daily treatment through the end of the local pollen season. They then resumed the same treatment schedule during the subsequent 2 years. By the end of the fourth year of the study, roughly two-thirds of the initially enrolled patients remained in the study.

The most common adverse effect during treatment was mouth pruritus, followed by throat irritation. All of the adverse effects were mild or moderate, and their incidence and severity steadily declined during the 3 years of active treatment.

No patients in the study had an anaphylactic reaction, unlike what occurs with subcutaneous injections, which are know to cause anaphylaxis occasionally. The entire worldwide experience with the sublingual grass pollen tablet has so far resulted in six episodes of "doubtful" anaphylaxis, an experience that led Dr. Malling to declare that the sublingual tablet "is safer" than subcutaneous injections.

"For some patients, [sublingual] is probably optimal, while for others subcutaneous will be better," Dr. Malling said. Having both options available gives patients a choice of disease-modifying therapy. One advantage of the sublingual tablet is that it precludes the need for patients to travel to a physician’s office for regular injections, he noted, although being on a schedule of regular injections helps ensure compliance.

Stallergenes developed the sublingual tablet, and has marketed it as Oralair in Europe since 2009. The tablet contains pollen extracts from five grass types that are common throughout Europe.

A pivotal trial of the formulation is in progress in the United States, but has not yet progressed to the stage where patients have stopped active, seasonal treatment. Other companies are also conducting clinical trials to test the efficacy and safety of sublingual desensitization tablets for grass pollen and for other allergens. The new results reported by Dr. Malling and his associates are the first to report what happens once patients stop active, annual treatment.

The study was sponsored by Stallergenes, the company that markets the sublingual grass pollen tablet as Oralair. Dr. Malling said that he is a consultant to and has received research support from Stallergenes and from several other drug companies.

ORLANDO – Patients who underwent 3 consecutive years of desensitization to grass pollen with seasonal use of a daily, sublingual pill maintained their reduced level of grass pollen allergy during the following fourth season despite stopping pill treatment, according to results from a study of 432 patients who stayed in the study for 4 years.

The findings provide the first evidence that sublingual desensitization produces allergy disease modification similar to subcutaneous desensitization, Dr. Hans-Jørgen Malling said during a poster presentation March 4 at the meeting.

"The data show sustained clinical efficacy when you stop treatment," said Dr. Malling, professor of medicine at the University of Copenhagen and chief of the allergy clinic at Gentofte Hospital in nearby Hellerup. "That is disease modifying. If there is no efficacy after you stop treatment, then this treatment will not be viable."

Although long-term efficacy is crucial, "up to now, it seems like sublingual is equivalent to subcutaneous," he said in an interview.

But Dr. Malling also cautioned that a major test will be the ability of sublingual desensitization to maintain allergy desensitization during a second year off treatment – results that will come during the fifth and final year of the study and will be available a year from now.

Prior reports from the current study documented the ability of the sublingual grass pollen pill to produce desensitization in adult patients during each of the 3 years of active treatment (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011;128:559-66).

During the first 3 years, the oral desensitization regimen led to progressively higher levels of symptom reduction each year, compared with placebo, a pattern that mimicked what typically occurs with subcutaneous desensitization.

The new results showed that during patients’ first year off active treatment, symptom relief showed a trend toward a small dip in efficacy (see box), compared with placebo, although patients also self reported a maintained, positive effect on their total quality of life scores.

During the first year off treatment, the average adjusted symptom score (the study’s primary end point) was 29% below the placebo level among 136 patients who both took the pill starting 2 months before the start of their allergy season and remained in the study. The symptom score was 23% below placebo among the 142 patients who took the pill starting 4 months before the start of their allergy season and remained in the study.

The study initially randomized 633 adult patients with grass pollen allergy at several European centers. Patients began receiving either the active desensitization tablet or placebo at 2 months or 4 months before the onset of their local grass pollen season, and continued daily treatment through the end of the local pollen season. They then resumed the same treatment schedule during the subsequent 2 years. By the end of the fourth year of the study, roughly two-thirds of the initially enrolled patients remained in the study.

The most common adverse effect during treatment was mouth pruritus, followed by throat irritation. All of the adverse effects were mild or moderate, and their incidence and severity steadily declined during the 3 years of active treatment.

No patients in the study had an anaphylactic reaction, unlike what occurs with subcutaneous injections, which are know to cause anaphylaxis occasionally. The entire worldwide experience with the sublingual grass pollen tablet has so far resulted in six episodes of "doubtful" anaphylaxis, an experience that led Dr. Malling to declare that the sublingual tablet "is safer" than subcutaneous injections.

"For some patients, [sublingual] is probably optimal, while for others subcutaneous will be better," Dr. Malling said. Having both options available gives patients a choice of disease-modifying therapy. One advantage of the sublingual tablet is that it precludes the need for patients to travel to a physician’s office for regular injections, he noted, although being on a schedule of regular injections helps ensure compliance.

Stallergenes developed the sublingual tablet, and has marketed it as Oralair in Europe since 2009. The tablet contains pollen extracts from five grass types that are common throughout Europe.

A pivotal trial of the formulation is in progress in the United States, but has not yet progressed to the stage where patients have stopped active, seasonal treatment. Other companies are also conducting clinical trials to test the efficacy and safety of sublingual desensitization tablets for grass pollen and for other allergens. The new results reported by Dr. Malling and his associates are the first to report what happens once patients stop active, annual treatment.

The study was sponsored by Stallergenes, the company that markets the sublingual grass pollen tablet as Oralair. Dr. Malling said that he is a consultant to and has received research support from Stallergenes and from several other drug companies.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ALLERGY, ASTHMA, AND IMMUNOLOGY

Major Finding: Grass-allergy patients with 3 years of desensitization with a sublingual tablet maintained desensitization in their first season without treatment.

Data Source: A multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled study that initially enrolled 633 adult patients with grass pollen allergy.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Stallergenes, the company that markets the sublingual grass pollen tablet as Oralair. Dr. Malling said that he is a consultant to and has received research support from Stallergenes and from several other drug companies.