User login

American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology (AAAAI): Annual Meeting

VIDEO: Asthma management app for teens shows promise

SAN DIEGO – A smartphone app designed for children and teenagers with asthma improved medication adherence in a 30-day pilot study of 21 patients. Dr. David Stukus talked with us at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology about the app’s design and use of evidence-based medicine, how well it worked with adolescents, and a larger prospective trial that’s in the works.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN DIEGO – A smartphone app designed for children and teenagers with asthma improved medication adherence in a 30-day pilot study of 21 patients. Dr. David Stukus talked with us at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology about the app’s design and use of evidence-based medicine, how well it worked with adolescents, and a larger prospective trial that’s in the works.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN DIEGO – A smartphone app designed for children and teenagers with asthma improved medication adherence in a 30-day pilot study of 21 patients. Dr. David Stukus talked with us at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology about the app’s design and use of evidence-based medicine, how well it worked with adolescents, and a larger prospective trial that’s in the works.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @sherryboschert

AT 2014 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

VIDEO: Allergy myths misdirect patients, physicians

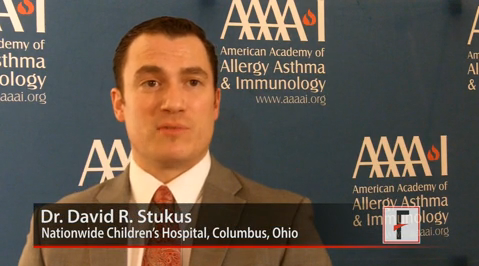

SAN DIEGO – Is there really such a thing as a hypoallergenic dog? (Bo Obama, we’re looking at you.) Can blood tests for sale on the Internet identify a child’s allergies? And must parents wait until a child is 1, 2, or 3 years of age to introduce dietary milk, eggs, or nuts?

Dr. David R. Stukus of Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, answers these questions and dispels other allergy-related misperceptions in an interview with us at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN DIEGO – Is there really such a thing as a hypoallergenic dog? (Bo Obama, we’re looking at you.) Can blood tests for sale on the Internet identify a child’s allergies? And must parents wait until a child is 1, 2, or 3 years of age to introduce dietary milk, eggs, or nuts?

Dr. David R. Stukus of Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, answers these questions and dispels other allergy-related misperceptions in an interview with us at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN DIEGO – Is there really such a thing as a hypoallergenic dog? (Bo Obama, we’re looking at you.) Can blood tests for sale on the Internet identify a child’s allergies? And must parents wait until a child is 1, 2, or 3 years of age to introduce dietary milk, eggs, or nuts?

Dr. David R. Stukus of Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, answers these questions and dispels other allergy-related misperceptions in an interview with us at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

AT 2014 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

VIDEO: Asthma meds’ safety data reassuring in pregnancy

SAN DIEGO – How safe are asthma medications during pregnancy? And how adherent are pregnant women to asthma medications? Dr. Jennifer A. Namazy of Scripps Clinic, La Jolla, Calif., summarizes the reassuring data on use of asthma medications by pregnant women, and she outlines her own approach to ensure pregnant women with asthma remain healthy and medication adherent.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN DIEGO – How safe are asthma medications during pregnancy? And how adherent are pregnant women to asthma medications? Dr. Jennifer A. Namazy of Scripps Clinic, La Jolla, Calif., summarizes the reassuring data on use of asthma medications by pregnant women, and she outlines her own approach to ensure pregnant women with asthma remain healthy and medication adherent.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN DIEGO – How safe are asthma medications during pregnancy? And how adherent are pregnant women to asthma medications? Dr. Jennifer A. Namazy of Scripps Clinic, La Jolla, Calif., summarizes the reassuring data on use of asthma medications by pregnant women, and she outlines her own approach to ensure pregnant women with asthma remain healthy and medication adherent.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

ANALYSIS FROM 2014 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

VIDEO: Eosinophilic esophagitis may follow outgrown food allergy

SAN DIEGO (FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS) – People who outgrow a food allergy may be at risk of developing eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) to the same food, Dr. Jonathan Spergel said in a press briefing at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

In a video interview, Dr. Spergel outlined the signs and symptoms that could point to EoE in a child who has outgrown a food allergy.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN DIEGO (FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS) – People who outgrow a food allergy may be at risk of developing eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) to the same food, Dr. Jonathan Spergel said in a press briefing at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

In a video interview, Dr. Spergel outlined the signs and symptoms that could point to EoE in a child who has outgrown a food allergy.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN DIEGO (FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS) – People who outgrow a food allergy may be at risk of developing eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) to the same food, Dr. Jonathan Spergel said in a press briefing at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

In a video interview, Dr. Spergel outlined the signs and symptoms that could point to EoE in a child who has outgrown a food allergy.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @sherryboschert

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM 2014 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Asthma more common in eosinophilic esophagitis than previously thought

SAN DIEGO – Asthma and airway hyperresponsiveness may be underrecognized in children with eosinophilic esophagitis, results from a controlled cross-sectional study demonstrated.

While previous studies have estimated the prevalence of asthma in children with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), to range from 24-42%, a recent analysis presented during a late-breaker abstract session at annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology found that up to 70% of children with EoE may suffer from asthma.

"Clinicians treating children with eosinophilic esophagitis should consider asking additional history questions related to asthma symptoms and may also want to consider pulmonary function testing or referral to an asthma specialist for evaluation," lead author Dr. Nadia L. Krupp said in an interview prior to the meeting. "This is the first study to formally evaluate lung function and airway hyperresponsiveness in children with EoE. Prior estimations of asthma have solely come from patient/parent report."

Dr. Krupp, director of the Riley Asthma Care Center in the section of pulmonology, allergy, and critical care medicine at Riley Hospital Children, Indianapolis, and her associates conducted a cross-sectional study of 33 children aged 6-18 years with EoE and 37 healthy controls. The researchers performed methacholine challenge (airway hyperresponsiveness defined as provocative concentration of methacholine less than 8mg/mL), and exhaled nitric oxide. They also analyzed peripheral blood for total IgE, eosinophil count, eotaxin, and serum cytokines.

Baseline spirometry did not significantly differ between EoE subjects and healthy controls. However, airway hyperresponsiveness was present in 33% of children with EoE, compared with only 10.8% of healthy controls (P = .04). In addition, 20% of the 15 EoE subjects with asthma had airway hyperresponsiveness, compared with 44% of the 18 EoE subjects without asthma. Overall, 69.7% of EoE subjects had either asthma or airway hyperresponsiveness.

The researchers found that airway hyperresponsiveness correlated strongly with serum IgE (P less than .0001) and exhaled nitric oxide (P = .0002), while epidermal growth factor (EGF) and fibroblastic growth factor–2 (FGF-2) were elevated in subjects with EoE and asthma, compared to healthy controls and those with EoE but no asthma (P less than .05). In addition, subjects with EoE and asthma who were on asthma controller medications had similar levels of EGF and FGF-2 as healthy controls, while Th2 cytokines and eotaxin did not differ significantly among any groups.

Dr. Krupp said she was surprised "by the fact that airway hyperresponsiveness was more prevalent in those subjects without a history of asthma than those with a known diagnosis, and the fact that Th2-related cytokines were not significantly different between healthy controls and EoE subjects."

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its cross-sectional design and "the fact EoE subjects may have had significant variability in the current activity of their esophageal disease at the time of enrollment."

The study was partially funded by Aerocrine. Dr. Krupp said that she had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

SAN DIEGO – Asthma and airway hyperresponsiveness may be underrecognized in children with eosinophilic esophagitis, results from a controlled cross-sectional study demonstrated.

While previous studies have estimated the prevalence of asthma in children with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), to range from 24-42%, a recent analysis presented during a late-breaker abstract session at annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology found that up to 70% of children with EoE may suffer from asthma.

"Clinicians treating children with eosinophilic esophagitis should consider asking additional history questions related to asthma symptoms and may also want to consider pulmonary function testing or referral to an asthma specialist for evaluation," lead author Dr. Nadia L. Krupp said in an interview prior to the meeting. "This is the first study to formally evaluate lung function and airway hyperresponsiveness in children with EoE. Prior estimations of asthma have solely come from patient/parent report."

Dr. Krupp, director of the Riley Asthma Care Center in the section of pulmonology, allergy, and critical care medicine at Riley Hospital Children, Indianapolis, and her associates conducted a cross-sectional study of 33 children aged 6-18 years with EoE and 37 healthy controls. The researchers performed methacholine challenge (airway hyperresponsiveness defined as provocative concentration of methacholine less than 8mg/mL), and exhaled nitric oxide. They also analyzed peripheral blood for total IgE, eosinophil count, eotaxin, and serum cytokines.

Baseline spirometry did not significantly differ between EoE subjects and healthy controls. However, airway hyperresponsiveness was present in 33% of children with EoE, compared with only 10.8% of healthy controls (P = .04). In addition, 20% of the 15 EoE subjects with asthma had airway hyperresponsiveness, compared with 44% of the 18 EoE subjects without asthma. Overall, 69.7% of EoE subjects had either asthma or airway hyperresponsiveness.

The researchers found that airway hyperresponsiveness correlated strongly with serum IgE (P less than .0001) and exhaled nitric oxide (P = .0002), while epidermal growth factor (EGF) and fibroblastic growth factor–2 (FGF-2) were elevated in subjects with EoE and asthma, compared to healthy controls and those with EoE but no asthma (P less than .05). In addition, subjects with EoE and asthma who were on asthma controller medications had similar levels of EGF and FGF-2 as healthy controls, while Th2 cytokines and eotaxin did not differ significantly among any groups.

Dr. Krupp said she was surprised "by the fact that airway hyperresponsiveness was more prevalent in those subjects without a history of asthma than those with a known diagnosis, and the fact that Th2-related cytokines were not significantly different between healthy controls and EoE subjects."

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its cross-sectional design and "the fact EoE subjects may have had significant variability in the current activity of their esophageal disease at the time of enrollment."

The study was partially funded by Aerocrine. Dr. Krupp said that she had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

SAN DIEGO – Asthma and airway hyperresponsiveness may be underrecognized in children with eosinophilic esophagitis, results from a controlled cross-sectional study demonstrated.

While previous studies have estimated the prevalence of asthma in children with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), to range from 24-42%, a recent analysis presented during a late-breaker abstract session at annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology found that up to 70% of children with EoE may suffer from asthma.

"Clinicians treating children with eosinophilic esophagitis should consider asking additional history questions related to asthma symptoms and may also want to consider pulmonary function testing or referral to an asthma specialist for evaluation," lead author Dr. Nadia L. Krupp said in an interview prior to the meeting. "This is the first study to formally evaluate lung function and airway hyperresponsiveness in children with EoE. Prior estimations of asthma have solely come from patient/parent report."

Dr. Krupp, director of the Riley Asthma Care Center in the section of pulmonology, allergy, and critical care medicine at Riley Hospital Children, Indianapolis, and her associates conducted a cross-sectional study of 33 children aged 6-18 years with EoE and 37 healthy controls. The researchers performed methacholine challenge (airway hyperresponsiveness defined as provocative concentration of methacholine less than 8mg/mL), and exhaled nitric oxide. They also analyzed peripheral blood for total IgE, eosinophil count, eotaxin, and serum cytokines.

Baseline spirometry did not significantly differ between EoE subjects and healthy controls. However, airway hyperresponsiveness was present in 33% of children with EoE, compared with only 10.8% of healthy controls (P = .04). In addition, 20% of the 15 EoE subjects with asthma had airway hyperresponsiveness, compared with 44% of the 18 EoE subjects without asthma. Overall, 69.7% of EoE subjects had either asthma or airway hyperresponsiveness.

The researchers found that airway hyperresponsiveness correlated strongly with serum IgE (P less than .0001) and exhaled nitric oxide (P = .0002), while epidermal growth factor (EGF) and fibroblastic growth factor–2 (FGF-2) were elevated in subjects with EoE and asthma, compared to healthy controls and those with EoE but no asthma (P less than .05). In addition, subjects with EoE and asthma who were on asthma controller medications had similar levels of EGF and FGF-2 as healthy controls, while Th2 cytokines and eotaxin did not differ significantly among any groups.

Dr. Krupp said she was surprised "by the fact that airway hyperresponsiveness was more prevalent in those subjects without a history of asthma than those with a known diagnosis, and the fact that Th2-related cytokines were not significantly different between healthy controls and EoE subjects."

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its cross-sectional design and "the fact EoE subjects may have had significant variability in the current activity of their esophageal disease at the time of enrollment."

The study was partially funded by Aerocrine. Dr. Krupp said that she had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

AT THE 2014 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: Airway hyperresponsiveness was present in 33% of children with EoE, compared with only 10.8% of healthy controls (P= .04). In addition, 20% of the 15 EoE subjects with asthma had airway hyperresponsiveness, compared with 44% of the 18 EoE subjects without asthma.

Data source: A cross-sectional study of 33 children aged 6-18 years with EoE and 37 healthy controls.

Disclosures: The study was partially funded by Aerocrine. Dr. Krupp said that she had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Biphasic reaction risk rises with severity of initial anaphylactic attack

SAN DIEGO – The more severe an anaphylactic reaction, the more likely that a child will have a second reaction within several hours, according to data from a review of more than 400 children. The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Researchers found five independent predictors for biphasic reactions: age 6-9 years (OR, 3.60); time greater than 90 minutes from the onset of the initial anaphylactic reaction to emergency department presentation (OR, 2.58); wide pulse pressure at triage (OR, 2.92); treatment of the initial reaction with more than one dose of epinephrine (OR, 2.7); and administration of inhaled albuterol (Salbutamol) in the ED (OR, 2.39).

The "five clinical predictors could ultimately be used to identify patients who would benefit from prolonged ED or inpatient monitoring," noted Dr. Waleed D. Alqurashi of the University of Ottawa, and colleagues. "These findings may enable better utilization of ED resources and counseling of patients and families after anaphylactic reactions," they added.

The retrospective multicenter study included data from 484 children who visited an ED from January 2010 through December 2010 with anaphylactic reactions requiring epinephrine. Of these, 71 (15%) went on to a second reaction, most within 6 hours of the first. The median age of the children was 4.8 years, and about 65% were male.

"If any of these predictors are there, it means they need to be observed" at least 6-8 hours, said Dr. Alqurashi, an emergency medicine research fellow. "If the initial reaction was mild and treated appropriately with epinephrine, they don’t need to stay in the department for a long period of time," he said.

Of the 71 biphasic reactions, 53 (75%) occurred in the ED a median of 4.7 hours after the initial anaphylactic reaction; 18 (25%) occurred after ED discharge at a median of 18.5 hours from the first reaction. Thirty-five (49%) of the second reactions were anaphylactic, requiring epinephrine. "The other half were milder in nature," but still sometimes required oxygen or other significant interventions, Dr. Alqurashi said.

"Nobody knows exactly how often [biphasic reactions] happen," he said, although the data suggest that reactions occur about 15% of the time. The hunch is that the second reaction isn’t really an independent event, just a continuation of the first attack, he explained. "When you treat it the first time, you mask the symptoms" and the patient presents clinically again a few hours later, after the first round of medications wears off.

There were no statistical differences between children who had uniphasic and biphasic reactions in terms of the numbers of systems involved in their reactions. The majority of children in both groups had respiratory signs.

In agreement with previous studies, systemic steroids did not prevent biphasic reactions. "They were not useful. There may be a subpopulation that benefits from them, for example, people with asthma," Dr. Alqurashi said.

The investigators did not report outside funding. Dr. Alqurashi said he has no disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The more severe an anaphylactic reaction, the more likely that a child will have a second reaction within several hours, according to data from a review of more than 400 children. The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Researchers found five independent predictors for biphasic reactions: age 6-9 years (OR, 3.60); time greater than 90 minutes from the onset of the initial anaphylactic reaction to emergency department presentation (OR, 2.58); wide pulse pressure at triage (OR, 2.92); treatment of the initial reaction with more than one dose of epinephrine (OR, 2.7); and administration of inhaled albuterol (Salbutamol) in the ED (OR, 2.39).

The "five clinical predictors could ultimately be used to identify patients who would benefit from prolonged ED or inpatient monitoring," noted Dr. Waleed D. Alqurashi of the University of Ottawa, and colleagues. "These findings may enable better utilization of ED resources and counseling of patients and families after anaphylactic reactions," they added.

The retrospective multicenter study included data from 484 children who visited an ED from January 2010 through December 2010 with anaphylactic reactions requiring epinephrine. Of these, 71 (15%) went on to a second reaction, most within 6 hours of the first. The median age of the children was 4.8 years, and about 65% were male.

"If any of these predictors are there, it means they need to be observed" at least 6-8 hours, said Dr. Alqurashi, an emergency medicine research fellow. "If the initial reaction was mild and treated appropriately with epinephrine, they don’t need to stay in the department for a long period of time," he said.

Of the 71 biphasic reactions, 53 (75%) occurred in the ED a median of 4.7 hours after the initial anaphylactic reaction; 18 (25%) occurred after ED discharge at a median of 18.5 hours from the first reaction. Thirty-five (49%) of the second reactions were anaphylactic, requiring epinephrine. "The other half were milder in nature," but still sometimes required oxygen or other significant interventions, Dr. Alqurashi said.

"Nobody knows exactly how often [biphasic reactions] happen," he said, although the data suggest that reactions occur about 15% of the time. The hunch is that the second reaction isn’t really an independent event, just a continuation of the first attack, he explained. "When you treat it the first time, you mask the symptoms" and the patient presents clinically again a few hours later, after the first round of medications wears off.

There were no statistical differences between children who had uniphasic and biphasic reactions in terms of the numbers of systems involved in their reactions. The majority of children in both groups had respiratory signs.

In agreement with previous studies, systemic steroids did not prevent biphasic reactions. "They were not useful. There may be a subpopulation that benefits from them, for example, people with asthma," Dr. Alqurashi said.

The investigators did not report outside funding. Dr. Alqurashi said he has no disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The more severe an anaphylactic reaction, the more likely that a child will have a second reaction within several hours, according to data from a review of more than 400 children. The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Researchers found five independent predictors for biphasic reactions: age 6-9 years (OR, 3.60); time greater than 90 minutes from the onset of the initial anaphylactic reaction to emergency department presentation (OR, 2.58); wide pulse pressure at triage (OR, 2.92); treatment of the initial reaction with more than one dose of epinephrine (OR, 2.7); and administration of inhaled albuterol (Salbutamol) in the ED (OR, 2.39).

The "five clinical predictors could ultimately be used to identify patients who would benefit from prolonged ED or inpatient monitoring," noted Dr. Waleed D. Alqurashi of the University of Ottawa, and colleagues. "These findings may enable better utilization of ED resources and counseling of patients and families after anaphylactic reactions," they added.

The retrospective multicenter study included data from 484 children who visited an ED from January 2010 through December 2010 with anaphylactic reactions requiring epinephrine. Of these, 71 (15%) went on to a second reaction, most within 6 hours of the first. The median age of the children was 4.8 years, and about 65% were male.

"If any of these predictors are there, it means they need to be observed" at least 6-8 hours, said Dr. Alqurashi, an emergency medicine research fellow. "If the initial reaction was mild and treated appropriately with epinephrine, they don’t need to stay in the department for a long period of time," he said.

Of the 71 biphasic reactions, 53 (75%) occurred in the ED a median of 4.7 hours after the initial anaphylactic reaction; 18 (25%) occurred after ED discharge at a median of 18.5 hours from the first reaction. Thirty-five (49%) of the second reactions were anaphylactic, requiring epinephrine. "The other half were milder in nature," but still sometimes required oxygen or other significant interventions, Dr. Alqurashi said.

"Nobody knows exactly how often [biphasic reactions] happen," he said, although the data suggest that reactions occur about 15% of the time. The hunch is that the second reaction isn’t really an independent event, just a continuation of the first attack, he explained. "When you treat it the first time, you mask the symptoms" and the patient presents clinically again a few hours later, after the first round of medications wears off.

There were no statistical differences between children who had uniphasic and biphasic reactions in terms of the numbers of systems involved in their reactions. The majority of children in both groups had respiratory signs.

In agreement with previous studies, systemic steroids did not prevent biphasic reactions. "They were not useful. There may be a subpopulation that benefits from them, for example, people with asthma," Dr. Alqurashi said.

The investigators did not report outside funding. Dr. Alqurashi said he has no disclosures.

AT THE 2014 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: The odds of biphasic reactions more than double if the first anaphylactic attack requires more than one epinephrine shot (OR, 2.92; 95% CI 1.69-5.04).

Data Source: Retrospective cohort analysis of anaphylactic reactions in 484 children.

Disclosures: The investigators did not report outside funding. The lead author had no disclosures.

Computer program calls parents when asthma scrips run low

SAN DIEGO – A newly developed computer program mines electronic medical records to find pediatric asthma patients who are about to run out of their inhaled corticosteroid inhalers, then calls their parents to help them order new ones.

It’s not a robocall. Parents don’t push buttons to signal their response. Instead, they speak to the computer, and it understands what they say, just like the automated speech-recognition telephone systems used by credit card companies, airlines, and other industries. The software was developed by team from National Jewish Health and Kaiser Permanente Colorado, both in Denver.

At 24 months, adherence – measured by medication possession ratio – was 44.5% among 452 children randomized to the calls and 35.5% among 447 who were not, a statistically significant 25% difference.

"It takes a fair amount of work to get a system like this going, but then the computer does the rest. Most adherence interventions expect busy health care providers to do something; this doesn’t add any burden to their day. Think of it as the electronic health record picking up the phone and talking with patients," said project leader Bruce Bender, Ph.D., head of pediatric behavioral health at National Jewish Health in Denver.

The system calls parents 10 days before the child is due to run out of the inhaler. "It pulls information out of the EHR, so when it talks to the parent, it references the prescribing physician, the name of the child, and the last time the inhaled corticosteroid prescription was filled." It then gives parents options to refill the prescription or talk with an asthma nurse or pharmacist, among other things, he said.

The 25% adherence improvement was consistent throughout the investigation and in subgroups stratified by age, gender, race, body mass index, or disease-related characteristics.

ED visits and admissions did not differ between the call and control groups. "We were a little bit surprised by that, because this is a bigger bump in adherence than you typically see in adherence interventions." Maybe it was because "care is already pretty good in [our system]; we keep people out of the ED pretty effectively." In both groups, there were 0.09 ED visits per person in the year before enrollment, Dr. Bender said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

"It could also be that in asthma, you really need to change the [adherence] curve more dramatically to see a change in outcomes," he said.

Children in the study were aged 3-12 years. About 10% of parents contacted declined to participate in the program; about 90% of those who did said in subsequent surveys that they liked the calls and found them helpful. Dr. Bender and his colleagues said they hope to scale up the system for cardiovascular and adult asthma patients.

If parents did not pick up the phone, the system would leave a message and try a few more times, but "we capped it at three [callbacks]. We didn’t want people to feel harassed," he said.

Eliza Corp., a computer company outside of Boston, developed the program’s software. The efforts were funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood institute. Dr. Bender said he has no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – A newly developed computer program mines electronic medical records to find pediatric asthma patients who are about to run out of their inhaled corticosteroid inhalers, then calls their parents to help them order new ones.

It’s not a robocall. Parents don’t push buttons to signal their response. Instead, they speak to the computer, and it understands what they say, just like the automated speech-recognition telephone systems used by credit card companies, airlines, and other industries. The software was developed by team from National Jewish Health and Kaiser Permanente Colorado, both in Denver.

At 24 months, adherence – measured by medication possession ratio – was 44.5% among 452 children randomized to the calls and 35.5% among 447 who were not, a statistically significant 25% difference.

"It takes a fair amount of work to get a system like this going, but then the computer does the rest. Most adherence interventions expect busy health care providers to do something; this doesn’t add any burden to their day. Think of it as the electronic health record picking up the phone and talking with patients," said project leader Bruce Bender, Ph.D., head of pediatric behavioral health at National Jewish Health in Denver.

The system calls parents 10 days before the child is due to run out of the inhaler. "It pulls information out of the EHR, so when it talks to the parent, it references the prescribing physician, the name of the child, and the last time the inhaled corticosteroid prescription was filled." It then gives parents options to refill the prescription or talk with an asthma nurse or pharmacist, among other things, he said.

The 25% adherence improvement was consistent throughout the investigation and in subgroups stratified by age, gender, race, body mass index, or disease-related characteristics.

ED visits and admissions did not differ between the call and control groups. "We were a little bit surprised by that, because this is a bigger bump in adherence than you typically see in adherence interventions." Maybe it was because "care is already pretty good in [our system]; we keep people out of the ED pretty effectively." In both groups, there were 0.09 ED visits per person in the year before enrollment, Dr. Bender said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

"It could also be that in asthma, you really need to change the [adherence] curve more dramatically to see a change in outcomes," he said.

Children in the study were aged 3-12 years. About 10% of parents contacted declined to participate in the program; about 90% of those who did said in subsequent surveys that they liked the calls and found them helpful. Dr. Bender and his colleagues said they hope to scale up the system for cardiovascular and adult asthma patients.

If parents did not pick up the phone, the system would leave a message and try a few more times, but "we capped it at three [callbacks]. We didn’t want people to feel harassed," he said.

Eliza Corp., a computer company outside of Boston, developed the program’s software. The efforts were funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood institute. Dr. Bender said he has no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – A newly developed computer program mines electronic medical records to find pediatric asthma patients who are about to run out of their inhaled corticosteroid inhalers, then calls their parents to help them order new ones.

It’s not a robocall. Parents don’t push buttons to signal their response. Instead, they speak to the computer, and it understands what they say, just like the automated speech-recognition telephone systems used by credit card companies, airlines, and other industries. The software was developed by team from National Jewish Health and Kaiser Permanente Colorado, both in Denver.

At 24 months, adherence – measured by medication possession ratio – was 44.5% among 452 children randomized to the calls and 35.5% among 447 who were not, a statistically significant 25% difference.

"It takes a fair amount of work to get a system like this going, but then the computer does the rest. Most adherence interventions expect busy health care providers to do something; this doesn’t add any burden to their day. Think of it as the electronic health record picking up the phone and talking with patients," said project leader Bruce Bender, Ph.D., head of pediatric behavioral health at National Jewish Health in Denver.

The system calls parents 10 days before the child is due to run out of the inhaler. "It pulls information out of the EHR, so when it talks to the parent, it references the prescribing physician, the name of the child, and the last time the inhaled corticosteroid prescription was filled." It then gives parents options to refill the prescription or talk with an asthma nurse or pharmacist, among other things, he said.

The 25% adherence improvement was consistent throughout the investigation and in subgroups stratified by age, gender, race, body mass index, or disease-related characteristics.

ED visits and admissions did not differ between the call and control groups. "We were a little bit surprised by that, because this is a bigger bump in adherence than you typically see in adherence interventions." Maybe it was because "care is already pretty good in [our system]; we keep people out of the ED pretty effectively." In both groups, there were 0.09 ED visits per person in the year before enrollment, Dr. Bender said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

"It could also be that in asthma, you really need to change the [adherence] curve more dramatically to see a change in outcomes," he said.

Children in the study were aged 3-12 years. About 10% of parents contacted declined to participate in the program; about 90% of those who did said in subsequent surveys that they liked the calls and found them helpful. Dr. Bender and his colleagues said they hope to scale up the system for cardiovascular and adult asthma patients.

If parents did not pick up the phone, the system would leave a message and try a few more times, but "we capped it at three [callbacks]. We didn’t want people to feel harassed," he said.

Eliza Corp., a computer company outside of Boston, developed the program’s software. The efforts were funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood institute. Dr. Bender said he has no relevant disclosures.

AT THE 2014 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: A computer program that links electronic medical records and speech recognition software automatically calls parents when the child’s asthma inhaler is about to run out, and helps them order a new one. The program increased inhaler adherence by 25%.

Data Source: Two year trial involving 899 patients.

Disclosures: The efforts were funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood institute. The lead investigator has no relevant disclosures.

List of allergy care ‘don’ts’ expanded

SAN DIEGO – Allergists added to their list of "don’ts" in the Choosing Wisely campaign by releasing a second set of five things that physicians should stop doing, bringing their number of recommendations to 10.

The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology was part of the first wave of groups in 2012 to compile lists of tests and procedures that are overused in diagnosis and treatment, as part of the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely campaign. Academy leaders released the new list at the annual meeting.

The second round of recommendations includes admonitions related to antihistamine use, food IgE testing, radiocontrast media, vaccinations, and penicillin allergy, with supporting statements and references to the evidence behind them. The five new recommendations are:

• Don’t rely on antihistamines as first-line treatment in severe allergic reactions. Data show that antihistamines are overused as first-line treatment for anaphylaxis, and they have been associated with delay of proper treatment and death. The first-line treatment of anaphylaxis is epinephrine, the statement said.

• Don’t perform food IgE testing without a history consistent with potential IgE-mediated food allergy. From 50% to 90% of patients with presumed food allergies have food intolerance or symptoms produced by non-food-related causes, not IgE-mediated reactions. Ordering panels of food tests in those patients wastes resources and leads to misdiagnoses and unnecessary food avoidance.

• Don’t routinely order low- or iso-osmolar radiocontrast media or pretreat with corticosteroids and antihistamines for patients with a history of seafood allergy who require radiocontrast media. Some patients do react to contrast media, but the reactions aren’t related to seafood allergy, data in the medical literature show. Don’t deny imaging to patients with seafood allergies or pretreat them with antihistamines or corticosteroids, and don’t tell patients who have had an anaphylactic reaction to contrast media that they are allergic to seafood. Patients with a history of anaphylaxis to contrast media are at risk for another reaction if exposed again, and the risk of serious anaphylaxis from radiographic contrast media is increased in patients with asthma or cardiovascular disease or who are taking beta-blockers.

• Don’t routinely avoid influenza vaccination in egg-allergic patients. These patients can be given egg-free influenza vaccine or egg-based influenza vaccine if they are observed for 30 minutes afterward. Give the vaccine and observe the patient in an allergist/immunologist’s office if the patient has a history of a reaction stronger than hives from eating eggs.

• Don’t overuse non–beta-lactam antibiotics in patients with a history of penicillin allergy without an appropriate evaluation. Although 10% of people say they are allergic to penicillin, data show that only 1% truly have a penicillin allergy. That suggests that 99% of the population can take these antibiotics safely and can avoid the higher cost and greater complications associated with alternative antibiotics.

The statement emphasizes that these are not hard and fast rules, but rather words of advice that should spark conversations between patients and physicians if management choices diverge from these recommendations.

The academy’s list is preceded by the five items it released earlier in the Choosing Wisely campaign: Do not perform unproven diagnostic tests such as IgG testing or an indiscriminate battery of IgE tests in the evaluation of allergy. Do not order sinus CT or indiscriminately prescribe antibiotics for uncomplicated acute rhinosinusitis. Do not routinely do diagnostic testing in patients with chronic urticaria, or recommend replacement immunoglobulin therapy for recurrent infections unless there’s demonstration of impaired antibody responses to vaccines. And lastly, don’t diagnose or manage asthma without spirometry.

Lists created by medical groups in the Choosing Wisely campaign can be found here.

On twitter @sherryboschert

SAN DIEGO – Allergists added to their list of "don’ts" in the Choosing Wisely campaign by releasing a second set of five things that physicians should stop doing, bringing their number of recommendations to 10.

The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology was part of the first wave of groups in 2012 to compile lists of tests and procedures that are overused in diagnosis and treatment, as part of the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely campaign. Academy leaders released the new list at the annual meeting.

The second round of recommendations includes admonitions related to antihistamine use, food IgE testing, radiocontrast media, vaccinations, and penicillin allergy, with supporting statements and references to the evidence behind them. The five new recommendations are:

• Don’t rely on antihistamines as first-line treatment in severe allergic reactions. Data show that antihistamines are overused as first-line treatment for anaphylaxis, and they have been associated with delay of proper treatment and death. The first-line treatment of anaphylaxis is epinephrine, the statement said.

• Don’t perform food IgE testing without a history consistent with potential IgE-mediated food allergy. From 50% to 90% of patients with presumed food allergies have food intolerance or symptoms produced by non-food-related causes, not IgE-mediated reactions. Ordering panels of food tests in those patients wastes resources and leads to misdiagnoses and unnecessary food avoidance.

• Don’t routinely order low- or iso-osmolar radiocontrast media or pretreat with corticosteroids and antihistamines for patients with a history of seafood allergy who require radiocontrast media. Some patients do react to contrast media, but the reactions aren’t related to seafood allergy, data in the medical literature show. Don’t deny imaging to patients with seafood allergies or pretreat them with antihistamines or corticosteroids, and don’t tell patients who have had an anaphylactic reaction to contrast media that they are allergic to seafood. Patients with a history of anaphylaxis to contrast media are at risk for another reaction if exposed again, and the risk of serious anaphylaxis from radiographic contrast media is increased in patients with asthma or cardiovascular disease or who are taking beta-blockers.

• Don’t routinely avoid influenza vaccination in egg-allergic patients. These patients can be given egg-free influenza vaccine or egg-based influenza vaccine if they are observed for 30 minutes afterward. Give the vaccine and observe the patient in an allergist/immunologist’s office if the patient has a history of a reaction stronger than hives from eating eggs.

• Don’t overuse non–beta-lactam antibiotics in patients with a history of penicillin allergy without an appropriate evaluation. Although 10% of people say they are allergic to penicillin, data show that only 1% truly have a penicillin allergy. That suggests that 99% of the population can take these antibiotics safely and can avoid the higher cost and greater complications associated with alternative antibiotics.

The statement emphasizes that these are not hard and fast rules, but rather words of advice that should spark conversations between patients and physicians if management choices diverge from these recommendations.

The academy’s list is preceded by the five items it released earlier in the Choosing Wisely campaign: Do not perform unproven diagnostic tests such as IgG testing or an indiscriminate battery of IgE tests in the evaluation of allergy. Do not order sinus CT or indiscriminately prescribe antibiotics for uncomplicated acute rhinosinusitis. Do not routinely do diagnostic testing in patients with chronic urticaria, or recommend replacement immunoglobulin therapy for recurrent infections unless there’s demonstration of impaired antibody responses to vaccines. And lastly, don’t diagnose or manage asthma without spirometry.

Lists created by medical groups in the Choosing Wisely campaign can be found here.

On twitter @sherryboschert

SAN DIEGO – Allergists added to their list of "don’ts" in the Choosing Wisely campaign by releasing a second set of five things that physicians should stop doing, bringing their number of recommendations to 10.

The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology was part of the first wave of groups in 2012 to compile lists of tests and procedures that are overused in diagnosis and treatment, as part of the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely campaign. Academy leaders released the new list at the annual meeting.

The second round of recommendations includes admonitions related to antihistamine use, food IgE testing, radiocontrast media, vaccinations, and penicillin allergy, with supporting statements and references to the evidence behind them. The five new recommendations are:

• Don’t rely on antihistamines as first-line treatment in severe allergic reactions. Data show that antihistamines are overused as first-line treatment for anaphylaxis, and they have been associated with delay of proper treatment and death. The first-line treatment of anaphylaxis is epinephrine, the statement said.

• Don’t perform food IgE testing without a history consistent with potential IgE-mediated food allergy. From 50% to 90% of patients with presumed food allergies have food intolerance or symptoms produced by non-food-related causes, not IgE-mediated reactions. Ordering panels of food tests in those patients wastes resources and leads to misdiagnoses and unnecessary food avoidance.

• Don’t routinely order low- or iso-osmolar radiocontrast media or pretreat with corticosteroids and antihistamines for patients with a history of seafood allergy who require radiocontrast media. Some patients do react to contrast media, but the reactions aren’t related to seafood allergy, data in the medical literature show. Don’t deny imaging to patients with seafood allergies or pretreat them with antihistamines or corticosteroids, and don’t tell patients who have had an anaphylactic reaction to contrast media that they are allergic to seafood. Patients with a history of anaphylaxis to contrast media are at risk for another reaction if exposed again, and the risk of serious anaphylaxis from radiographic contrast media is increased in patients with asthma or cardiovascular disease or who are taking beta-blockers.

• Don’t routinely avoid influenza vaccination in egg-allergic patients. These patients can be given egg-free influenza vaccine or egg-based influenza vaccine if they are observed for 30 minutes afterward. Give the vaccine and observe the patient in an allergist/immunologist’s office if the patient has a history of a reaction stronger than hives from eating eggs.

• Don’t overuse non–beta-lactam antibiotics in patients with a history of penicillin allergy without an appropriate evaluation. Although 10% of people say they are allergic to penicillin, data show that only 1% truly have a penicillin allergy. That suggests that 99% of the population can take these antibiotics safely and can avoid the higher cost and greater complications associated with alternative antibiotics.

The statement emphasizes that these are not hard and fast rules, but rather words of advice that should spark conversations between patients and physicians if management choices diverge from these recommendations.

The academy’s list is preceded by the five items it released earlier in the Choosing Wisely campaign: Do not perform unproven diagnostic tests such as IgG testing or an indiscriminate battery of IgE tests in the evaluation of allergy. Do not order sinus CT or indiscriminately prescribe antibiotics for uncomplicated acute rhinosinusitis. Do not routinely do diagnostic testing in patients with chronic urticaria, or recommend replacement immunoglobulin therapy for recurrent infections unless there’s demonstration of impaired antibody responses to vaccines. And lastly, don’t diagnose or manage asthma without spirometry.

Lists created by medical groups in the Choosing Wisely campaign can be found here.

On twitter @sherryboschert

AT 2014 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps more severe in women

SAN DIEGO – Women with chronic rhinosinusitis and co-occurring nasal polyps appear to harbor more severe disease, compared with men, results from a large retrospective study demonstrate.

"For now, these are very preliminary studies, so there is not a lot of clinical application," Kathryn E. Hulse, Ph.D., said in an interview before the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, where the work was presented. "The hope is that if we can figure out why chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps is more severe in women, we would be able to design better therapeutic strategies to treat this disease in both men and women."

Up to half of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis have comorbid asthma, and Dr. Hulse and her associates at Northwestern University, Chicago, have previously reported that a subset of chronic rhinosinusitis patients with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) have elevated autoantigen-specific antibodies within their nasal polyps (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011;128:1198-206). In what she said is the first study of its kind, Dr. Hulse of the school’s division of allergy and immunology, and her associates retrospectively reviewed a database of 1,240 patients who underwent nasal surgery or were treated for CRS at Northwestern. They evaluated the effect of gender on the prevalence of CRSwNP, aspirin sensitivity, and asthma status, and used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to compare levels of eosinophil cationic protein and anti-dsDNA antibodies in NP extracts from men and women.

Mean patient age was 41 years, and 48% were women. Although women comprised about 50% of controls and CRS patients without NP, a significantly smaller proportion of CRSwNP patients were female (35%). Women with CRSwNP were significantly more likely to have comorbid asthma, and 65% of patients with aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (CRSwNP plus asthma and aspirin sensitivity) were women. Asthmatic women with CRSwNP had the highest levels of autoantigen-specific IgG and eosinophil cationic protein, and were significantly more likely to have revision surgeries.

"We thought we would find that CRSwNP was more prevalent and severe in women, especially because these patients have asthma and some features of local autoimmunity, which can be more prevalent and severe in women," Dr. Hulse said. "Instead, we found that men were more likely to have CRSwNP than women, but women did seem to have more severe disease."

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it focused solely on patients receiving care at a tertiary care center, "so we do not know if these results would be similar if we looked at the general population of people with CRSwNP who do not seek out specialized care. Also, these data were collected for patients at only one location, so we also do not know if the results would be similar at other tertiary care centers."

During a press briefing at the meeting, Dr. Hulse characterized the findings as "an important first step in identifying a potential area of future research and providing the justification for doing larger studies to see if this holds true in a larger population [of patients] or at other sites."

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health, including the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health program. Dr. Hulse said that she had no relevant financial conflicts.

SAN DIEGO – Women with chronic rhinosinusitis and co-occurring nasal polyps appear to harbor more severe disease, compared with men, results from a large retrospective study demonstrate.

"For now, these are very preliminary studies, so there is not a lot of clinical application," Kathryn E. Hulse, Ph.D., said in an interview before the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, where the work was presented. "The hope is that if we can figure out why chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps is more severe in women, we would be able to design better therapeutic strategies to treat this disease in both men and women."

Up to half of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis have comorbid asthma, and Dr. Hulse and her associates at Northwestern University, Chicago, have previously reported that a subset of chronic rhinosinusitis patients with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) have elevated autoantigen-specific antibodies within their nasal polyps (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011;128:1198-206). In what she said is the first study of its kind, Dr. Hulse of the school’s division of allergy and immunology, and her associates retrospectively reviewed a database of 1,240 patients who underwent nasal surgery or were treated for CRS at Northwestern. They evaluated the effect of gender on the prevalence of CRSwNP, aspirin sensitivity, and asthma status, and used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to compare levels of eosinophil cationic protein and anti-dsDNA antibodies in NP extracts from men and women.

Mean patient age was 41 years, and 48% were women. Although women comprised about 50% of controls and CRS patients without NP, a significantly smaller proportion of CRSwNP patients were female (35%). Women with CRSwNP were significantly more likely to have comorbid asthma, and 65% of patients with aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (CRSwNP plus asthma and aspirin sensitivity) were women. Asthmatic women with CRSwNP had the highest levels of autoantigen-specific IgG and eosinophil cationic protein, and were significantly more likely to have revision surgeries.

"We thought we would find that CRSwNP was more prevalent and severe in women, especially because these patients have asthma and some features of local autoimmunity, which can be more prevalent and severe in women," Dr. Hulse said. "Instead, we found that men were more likely to have CRSwNP than women, but women did seem to have more severe disease."

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it focused solely on patients receiving care at a tertiary care center, "so we do not know if these results would be similar if we looked at the general population of people with CRSwNP who do not seek out specialized care. Also, these data were collected for patients at only one location, so we also do not know if the results would be similar at other tertiary care centers."

During a press briefing at the meeting, Dr. Hulse characterized the findings as "an important first step in identifying a potential area of future research and providing the justification for doing larger studies to see if this holds true in a larger population [of patients] or at other sites."

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health, including the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health program. Dr. Hulse said that she had no relevant financial conflicts.

SAN DIEGO – Women with chronic rhinosinusitis and co-occurring nasal polyps appear to harbor more severe disease, compared with men, results from a large retrospective study demonstrate.

"For now, these are very preliminary studies, so there is not a lot of clinical application," Kathryn E. Hulse, Ph.D., said in an interview before the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, where the work was presented. "The hope is that if we can figure out why chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps is more severe in women, we would be able to design better therapeutic strategies to treat this disease in both men and women."

Up to half of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis have comorbid asthma, and Dr. Hulse and her associates at Northwestern University, Chicago, have previously reported that a subset of chronic rhinosinusitis patients with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) have elevated autoantigen-specific antibodies within their nasal polyps (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011;128:1198-206). In what she said is the first study of its kind, Dr. Hulse of the school’s division of allergy and immunology, and her associates retrospectively reviewed a database of 1,240 patients who underwent nasal surgery or were treated for CRS at Northwestern. They evaluated the effect of gender on the prevalence of CRSwNP, aspirin sensitivity, and asthma status, and used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to compare levels of eosinophil cationic protein and anti-dsDNA antibodies in NP extracts from men and women.

Mean patient age was 41 years, and 48% were women. Although women comprised about 50% of controls and CRS patients without NP, a significantly smaller proportion of CRSwNP patients were female (35%). Women with CRSwNP were significantly more likely to have comorbid asthma, and 65% of patients with aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (CRSwNP plus asthma and aspirin sensitivity) were women. Asthmatic women with CRSwNP had the highest levels of autoantigen-specific IgG and eosinophil cationic protein, and were significantly more likely to have revision surgeries.

"We thought we would find that CRSwNP was more prevalent and severe in women, especially because these patients have asthma and some features of local autoimmunity, which can be more prevalent and severe in women," Dr. Hulse said. "Instead, we found that men were more likely to have CRSwNP than women, but women did seem to have more severe disease."

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it focused solely on patients receiving care at a tertiary care center, "so we do not know if these results would be similar if we looked at the general population of people with CRSwNP who do not seek out specialized care. Also, these data were collected for patients at only one location, so we also do not know if the results would be similar at other tertiary care centers."

During a press briefing at the meeting, Dr. Hulse characterized the findings as "an important first step in identifying a potential area of future research and providing the justification for doing larger studies to see if this holds true in a larger population [of patients] or at other sites."

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health, including the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health program. Dr. Hulse said that she had no relevant financial conflicts.

AT THE 2014 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: Compared with men, women with chronic rhinosinusitis and co-occurring nasal polyps (CRSwNP) were more likely to have comorbid asthma, and 65% of patients with aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (CRSwNP plus asthma and aspirin sensitivity) were women.

Data source: A retrospective review of 1,240 patients who underwent nasal surgery or were treated for chronic rhinosinusitis at Northwestern University, Chicago.

Disclosures: The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Hulse said that she had no relevant financial conflicts.

Foods can still trigger eosinophilic esophagitis after allergy outgrown

SAN DIEGO – Seventeen of 425 children who had eosinophilic esophagitis caused by a specific food developed the condition after outgrowing the allergy to that food, a retrospective study found.

People who outgrow a food allergy may be at risk of developing eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) to the same food, Dr. Jonathan Spergel said during a press briefing at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

He and his associates studied data on 1,025 children with EoE seen at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in 2000-2012 to assess the prevalence of food allergy. In 425 children (42%), a specific food was identified as the EoE culprit – reintroducing the food to the diet caused esophageal changes on biopsy or biopsy changes normalized when the food was removed from the diet.

Eighty-four children had a history of IgE-mediated food allergy. Milk, egg, wheat, and soy were the most common food triggers of EoE in the 425 children in the study and in a subset of 17 who had outgrown IgE-mediated allergy to the specific food, reported Dr. Spergel, chief of the allergy section at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Sixteen of the 17 patients had atopic disease. The most common foods causing IgE-mediated allergy were peanuts, tree nuts, eggs, and milk.

The development of EoE coincided with reintroducing the food triggers. The time between outgrowing an allergy and reintroducing the food, triggering EoE, averaged 2 years but ranged from 6 months to 5 years.

Notably, two of the children who outgrew their food allergy had a normal biopsy of the esophagus when they had the food allergy, he said.

The findings support other recent studies suggesting that the pathophysiologies of EoE and IgE-mediated food allergy are distinct from each other, and that both can occur in the same individual to the same food, Dr. Spergel said. The mechanism by which EoE develops is poorly understood.

"I think these kids probably always had EoE to the food, but they weren’t eating it" because of the allergy, he said. "From 1% to 15% on oral immunotherapy get EoE, depending on which group you look at. I don’t think we caused" EoE by giving oral immunotherapy, he added. "We uncovered it."

Although it is rare for children who outgrow a food allergy to later develop EoE to that food, it’s worth keeping in mind if a child starts vomiting often or complains of stomachaches months or years later, Dr. Spergel said. Keeping the possibility in mind may help clinicians rule out other etiologies and detect EoE faster. "You have to take it seriously and get it checked out," he said.

Of the 84 patients with IgE-mediated food allergy, the 17 who outgrew the allergy and then developed EoE to the same food were significantly older (12 years, on average), compared with 67 patients who developed EoE from a different food from the one that caused their allergy.

The lead author on the study was Dr. Solrun Melkorka Meggadottir, a fellow at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. The findings have been submitted to the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

Dr. Spergel and Dr. Meggadottir reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

|

|

Just because patients who had a food allergy now tolerate a food doesn’t mean that they’re going to be absolutely clear. One of the questions we have is whether these people really had EoE before but, because they also had IgE-mediated food allergy and weren’t eating the food, they didn’t have the demonstration of EoE.

We also know from several of our oral immunotherapy trials that some of these patients, once they go on oral immunotherapy, do develop EoE as well. I think it’s something we have to be watching for.

Dr. Hugh A. Sampson is a professor of pediatrics, allergy, and immunology at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. He made these comments during a press briefing at the meeting. Dr. Sampsom disclosed relationships with Danone, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Allertein Therapeutics, Regeneron, and Novartis.

|

|

Just because patients who had a food allergy now tolerate a food doesn’t mean that they’re going to be absolutely clear. One of the questions we have is whether these people really had EoE before but, because they also had IgE-mediated food allergy and weren’t eating the food, they didn’t have the demonstration of EoE.

We also know from several of our oral immunotherapy trials that some of these patients, once they go on oral immunotherapy, do develop EoE as well. I think it’s something we have to be watching for.

Dr. Hugh A. Sampson is a professor of pediatrics, allergy, and immunology at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. He made these comments during a press briefing at the meeting. Dr. Sampsom disclosed relationships with Danone, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Allertein Therapeutics, Regeneron, and Novartis.

|

|

Just because patients who had a food allergy now tolerate a food doesn’t mean that they’re going to be absolutely clear. One of the questions we have is whether these people really had EoE before but, because they also had IgE-mediated food allergy and weren’t eating the food, they didn’t have the demonstration of EoE.

We also know from several of our oral immunotherapy trials that some of these patients, once they go on oral immunotherapy, do develop EoE as well. I think it’s something we have to be watching for.

Dr. Hugh A. Sampson is a professor of pediatrics, allergy, and immunology at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. He made these comments during a press briefing at the meeting. Dr. Sampsom disclosed relationships with Danone, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Allertein Therapeutics, Regeneron, and Novartis.

SAN DIEGO – Seventeen of 425 children who had eosinophilic esophagitis caused by a specific food developed the condition after outgrowing the allergy to that food, a retrospective study found.

People who outgrow a food allergy may be at risk of developing eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) to the same food, Dr. Jonathan Spergel said during a press briefing at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

He and his associates studied data on 1,025 children with EoE seen at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in 2000-2012 to assess the prevalence of food allergy. In 425 children (42%), a specific food was identified as the EoE culprit – reintroducing the food to the diet caused esophageal changes on biopsy or biopsy changes normalized when the food was removed from the diet.

Eighty-four children had a history of IgE-mediated food allergy. Milk, egg, wheat, and soy were the most common food triggers of EoE in the 425 children in the study and in a subset of 17 who had outgrown IgE-mediated allergy to the specific food, reported Dr. Spergel, chief of the allergy section at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Sixteen of the 17 patients had atopic disease. The most common foods causing IgE-mediated allergy were peanuts, tree nuts, eggs, and milk.

The development of EoE coincided with reintroducing the food triggers. The time between outgrowing an allergy and reintroducing the food, triggering EoE, averaged 2 years but ranged from 6 months to 5 years.

Notably, two of the children who outgrew their food allergy had a normal biopsy of the esophagus when they had the food allergy, he said.

The findings support other recent studies suggesting that the pathophysiologies of EoE and IgE-mediated food allergy are distinct from each other, and that both can occur in the same individual to the same food, Dr. Spergel said. The mechanism by which EoE develops is poorly understood.

"I think these kids probably always had EoE to the food, but they weren’t eating it" because of the allergy, he said. "From 1% to 15% on oral immunotherapy get EoE, depending on which group you look at. I don’t think we caused" EoE by giving oral immunotherapy, he added. "We uncovered it."

Although it is rare for children who outgrow a food allergy to later develop EoE to that food, it’s worth keeping in mind if a child starts vomiting often or complains of stomachaches months or years later, Dr. Spergel said. Keeping the possibility in mind may help clinicians rule out other etiologies and detect EoE faster. "You have to take it seriously and get it checked out," he said.

Of the 84 patients with IgE-mediated food allergy, the 17 who outgrew the allergy and then developed EoE to the same food were significantly older (12 years, on average), compared with 67 patients who developed EoE from a different food from the one that caused their allergy.

The lead author on the study was Dr. Solrun Melkorka Meggadottir, a fellow at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. The findings have been submitted to the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

Dr. Spergel and Dr. Meggadottir reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN DIEGO – Seventeen of 425 children who had eosinophilic esophagitis caused by a specific food developed the condition after outgrowing the allergy to that food, a retrospective study found.

People who outgrow a food allergy may be at risk of developing eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) to the same food, Dr. Jonathan Spergel said during a press briefing at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

He and his associates studied data on 1,025 children with EoE seen at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in 2000-2012 to assess the prevalence of food allergy. In 425 children (42%), a specific food was identified as the EoE culprit – reintroducing the food to the diet caused esophageal changes on biopsy or biopsy changes normalized when the food was removed from the diet.

Eighty-four children had a history of IgE-mediated food allergy. Milk, egg, wheat, and soy were the most common food triggers of EoE in the 425 children in the study and in a subset of 17 who had outgrown IgE-mediated allergy to the specific food, reported Dr. Spergel, chief of the allergy section at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Sixteen of the 17 patients had atopic disease. The most common foods causing IgE-mediated allergy were peanuts, tree nuts, eggs, and milk.

The development of EoE coincided with reintroducing the food triggers. The time between outgrowing an allergy and reintroducing the food, triggering EoE, averaged 2 years but ranged from 6 months to 5 years.

Notably, two of the children who outgrew their food allergy had a normal biopsy of the esophagus when they had the food allergy, he said.

The findings support other recent studies suggesting that the pathophysiologies of EoE and IgE-mediated food allergy are distinct from each other, and that both can occur in the same individual to the same food, Dr. Spergel said. The mechanism by which EoE develops is poorly understood.

"I think these kids probably always had EoE to the food, but they weren’t eating it" because of the allergy, he said. "From 1% to 15% on oral immunotherapy get EoE, depending on which group you look at. I don’t think we caused" EoE by giving oral immunotherapy, he added. "We uncovered it."

Although it is rare for children who outgrow a food allergy to later develop EoE to that food, it’s worth keeping in mind if a child starts vomiting often or complains of stomachaches months or years later, Dr. Spergel said. Keeping the possibility in mind may help clinicians rule out other etiologies and detect EoE faster. "You have to take it seriously and get it checked out," he said.

Of the 84 patients with IgE-mediated food allergy, the 17 who outgrew the allergy and then developed EoE to the same food were significantly older (12 years, on average), compared with 67 patients who developed EoE from a different food from the one that caused their allergy.

The lead author on the study was Dr. Solrun Melkorka Meggadottir, a fellow at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. The findings have been submitted to the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

Dr. Spergel and Dr. Meggadottir reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

AT 2014 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: Seventeen of 425 children with eosinophilic esophagitis caused by a specific food redeveloped the condition after outgrowing an allergy to the same food.

Data source: A retrospective study of data on 1,025 children seen at one institution for eosinophilic esophagitis.

Disclosures: Dr. Spergel and Dr. Meggadottir reported having no relevant financial disclosures.