User login

Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM): Critical Care Congress

Palliative care shortens ICU, hospital stays, review shows

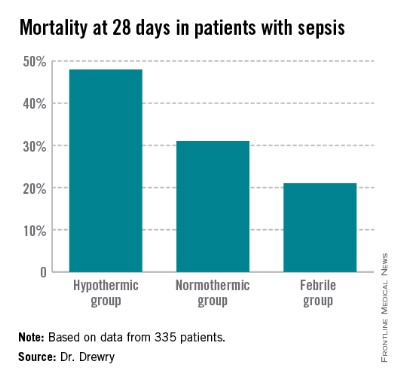

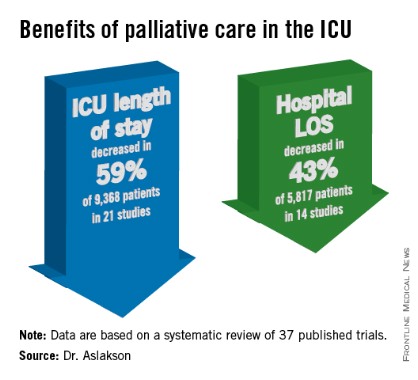

SAN FRANCISCO – Palliative care in the intensive care unit reduces the length of stay in the ICU and the hospital without changing mortality rates or family satisfaction, according to a review of the literature.

Although measurements of family satisfaction overall didn’t change much from palliative care of a loved one in the ICU, some measures of components of satisfaction increased with palliative care, such as improved communication with the physician, better consensus around the goals of care, and decreased anxiety and depression in family members, reported Dr. Rebecca A. Aslakson of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and her colleagues.

Dr. Aslakson presented the findings at the Critical Care Congress, sponsored by the Society for Critical Care Medicine.

Dr. Aslakson and her associates were unable to perform a formal meta-analysis of the 37 published trials of palliative care in the ICU because of the heterogeneity of the studies, which looked at more than 40 different outcomes.

Instead, their systematic review grouped results under four outcomes that commonly were measured, and assessed those either by the number of studies or by the number of patients studied.

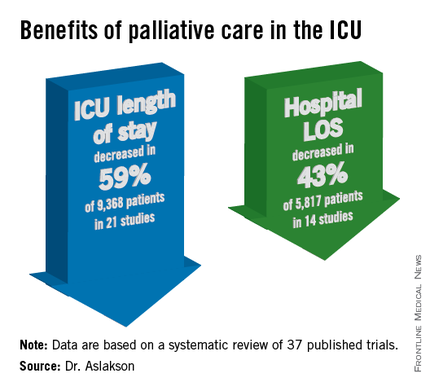

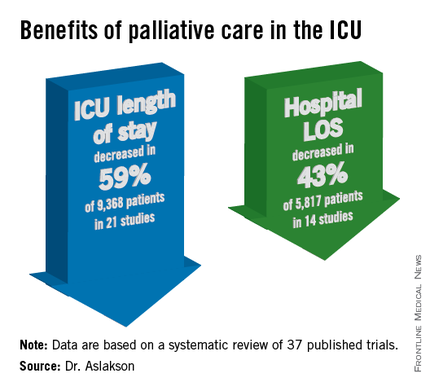

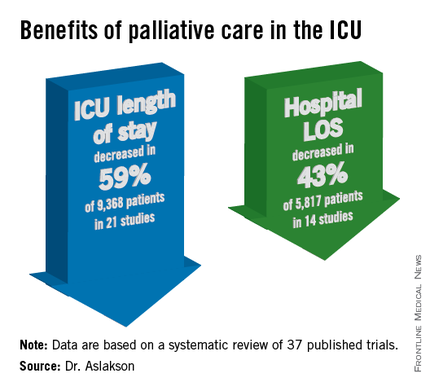

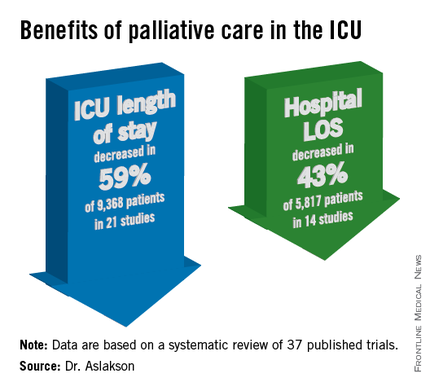

ICU length of stay decreased with palliative care in 13 of 21 studies (62%) that used this outcome and in 59% of 9,368 patients in those studies.

Hospital length of stay decreased with palliative care in 8 of 14 studies (57%) and in 43% of 5,817 patients. Family satisfaction did not decrease in any studies or families and increased in only 1 of 14 studies (7%) and in 2% of families of 4,927 patients, Dr. Aslakson and her colleagues reported (J. Palliat. Med. 2014;17:219-35).

Mortality rates did not change with palliative care in 14 of 16 studies (88%) that assessed mortality and in 57% of 5,969 patients in those studies. Mortality increased in one small study (6%) and decreased in one larger study (6%).

"Talking about big-picture issues and goals of care doesn’t lead to people dying," Dr. Aslakson said.

"No harm came in any of these studies." Some separate studies of palliative care outside of ICUs reported that this increases hope, "because people feel that they have more control over their choices and what’s happening to their loved ones," she added.

Integrative vs. consultative model

Dr. Aslakson and her associates also reviewed studies based on whether the interventions used integrative or consultative models of palliative care.

Generally, consultative models bring outsiders into the ICU to help provide palliative care, and integrative models train the ICU team to be the palliative care providers. In reality, the two models may overlap. For this review, the investigators applied mutually exclusive definitions to 36 of the studies.

In 18 studies of integrative interventions, members of the ICU team were the only caregivers in face-to-face interactions with the patient and families. In 18 studies of consultative interventions, palliative care providers included others besides the ICU team.

In the studies of integrative palliative care, ICU length of stay decreased with palliative care in four of nine studies (44%) that measured this outcome and in 52% of 6,963 patients in those studies, she reported. Hospital length of stay decreased in two of five studies (40%) and in 24% of 3,812 patients. Family satisfaction changed in none of 15 studies, and mortality decreased in 1 of 5 studies (20%) and in 34% of 3,807 patients.

In the studies of consultative care, ICU length of stay decreased with palliative care in 9 of 12 studies (75%) that measured this outcome and in 79% of 2,405 patients in those studies. Hospital length of stay decreased in six of nine studies (67%) and in 79% of 2,005 patients. Family satisfaction increased in one of four studies (25%) and in 21% of 429 patients. Mortality increased in 1 of 11 studies (9%) and in 5% of 2,162 patients.

One model isn’t necessarily better than the other, Dr. Aslakson said. Integrative palliative care may work best in a closed ICU with perhaps four or five intensivists in a relatively small unit. An integrative approach can be much more difficult in open or semiopen ICUs that have "40 different doctors floating around," she said. "We tried that in my unit, and it didn’t work that well."

Different ICUs need palliative care models that fit them. "Look at your unit, the way it works, and who the providers are, then look at the literature and see what matches that and what might work for your unit," she said.

Outcomes of better communication

A previous, separate review of the medical literature identified 21 controlled trials of 16 interventions to improve communication in ICUs between families and care providers. Overall, the interventions improved emotional outcomes for families and reduced ICU length of stay and treatment intensity (Chest 2011;139:543-54), she noted.

Yet another prior review of the literature reported that interventions to promote family meetings, use empathetic communication skills, and employ palliative care consultations improved family satisfaction and reduced ICU length of stay and the adverse effects of family bereavement (Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2009;15:569-77).

Dr. Aslakson reported having no financial disclosures.

Dr. Jennifer Cox, FCCP, comments: Dr. Aslakson and colleagues’ systematic review adds to the body of literature that demonstrates no mortality increase when palliative care measures are initiated in the ICU. Shorter lengths of stay both in the ICU and hospital were other positive outcomes noted without a significant change in patient or family satisfaction.

These findings were independent of whether an integrative or consultative approach to palliative care was undertaken. This should encourage physicians to examine their practice setting and determine which approach meets the needs of their ICU and begin to utilize palliative care earlier and more aggressively without fear of increasing mortality.

[email protected]

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN FRANCISCO – Palliative care in the intensive care unit reduces the length of stay in the ICU and the hospital without changing mortality rates or family satisfaction, according to a review of the literature.

Although measurements of family satisfaction overall didn’t change much from palliative care of a loved one in the ICU, some measures of components of satisfaction increased with palliative care, such as improved communication with the physician, better consensus around the goals of care, and decreased anxiety and depression in family members, reported Dr. Rebecca A. Aslakson of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and her colleagues.

Dr. Aslakson presented the findings at the Critical Care Congress, sponsored by the Society for Critical Care Medicine.

Dr. Aslakson and her associates were unable to perform a formal meta-analysis of the 37 published trials of palliative care in the ICU because of the heterogeneity of the studies, which looked at more than 40 different outcomes.

Instead, their systematic review grouped results under four outcomes that commonly were measured, and assessed those either by the number of studies or by the number of patients studied.

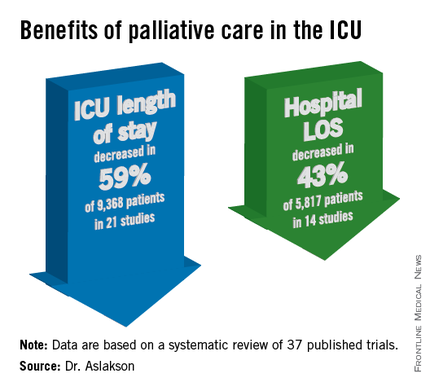

ICU length of stay decreased with palliative care in 13 of 21 studies (62%) that used this outcome and in 59% of 9,368 patients in those studies.

Hospital length of stay decreased with palliative care in 8 of 14 studies (57%) and in 43% of 5,817 patients. Family satisfaction did not decrease in any studies or families and increased in only 1 of 14 studies (7%) and in 2% of families of 4,927 patients, Dr. Aslakson and her colleagues reported (J. Palliat. Med. 2014;17:219-35).

Mortality rates did not change with palliative care in 14 of 16 studies (88%) that assessed mortality and in 57% of 5,969 patients in those studies. Mortality increased in one small study (6%) and decreased in one larger study (6%).

"Talking about big-picture issues and goals of care doesn’t lead to people dying," Dr. Aslakson said.

"No harm came in any of these studies." Some separate studies of palliative care outside of ICUs reported that this increases hope, "because people feel that they have more control over their choices and what’s happening to their loved ones," she added.

Integrative vs. consultative model

Dr. Aslakson and her associates also reviewed studies based on whether the interventions used integrative or consultative models of palliative care.

Generally, consultative models bring outsiders into the ICU to help provide palliative care, and integrative models train the ICU team to be the palliative care providers. In reality, the two models may overlap. For this review, the investigators applied mutually exclusive definitions to 36 of the studies.

In 18 studies of integrative interventions, members of the ICU team were the only caregivers in face-to-face interactions with the patient and families. In 18 studies of consultative interventions, palliative care providers included others besides the ICU team.

In the studies of integrative palliative care, ICU length of stay decreased with palliative care in four of nine studies (44%) that measured this outcome and in 52% of 6,963 patients in those studies, she reported. Hospital length of stay decreased in two of five studies (40%) and in 24% of 3,812 patients. Family satisfaction changed in none of 15 studies, and mortality decreased in 1 of 5 studies (20%) and in 34% of 3,807 patients.

In the studies of consultative care, ICU length of stay decreased with palliative care in 9 of 12 studies (75%) that measured this outcome and in 79% of 2,405 patients in those studies. Hospital length of stay decreased in six of nine studies (67%) and in 79% of 2,005 patients. Family satisfaction increased in one of four studies (25%) and in 21% of 429 patients. Mortality increased in 1 of 11 studies (9%) and in 5% of 2,162 patients.

One model isn’t necessarily better than the other, Dr. Aslakson said. Integrative palliative care may work best in a closed ICU with perhaps four or five intensivists in a relatively small unit. An integrative approach can be much more difficult in open or semiopen ICUs that have "40 different doctors floating around," she said. "We tried that in my unit, and it didn’t work that well."

Different ICUs need palliative care models that fit them. "Look at your unit, the way it works, and who the providers are, then look at the literature and see what matches that and what might work for your unit," she said.

Outcomes of better communication

A previous, separate review of the medical literature identified 21 controlled trials of 16 interventions to improve communication in ICUs between families and care providers. Overall, the interventions improved emotional outcomes for families and reduced ICU length of stay and treatment intensity (Chest 2011;139:543-54), she noted.

Yet another prior review of the literature reported that interventions to promote family meetings, use empathetic communication skills, and employ palliative care consultations improved family satisfaction and reduced ICU length of stay and the adverse effects of family bereavement (Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2009;15:569-77).

Dr. Aslakson reported having no financial disclosures.

Dr. Jennifer Cox, FCCP, comments: Dr. Aslakson and colleagues’ systematic review adds to the body of literature that demonstrates no mortality increase when palliative care measures are initiated in the ICU. Shorter lengths of stay both in the ICU and hospital were other positive outcomes noted without a significant change in patient or family satisfaction.

These findings were independent of whether an integrative or consultative approach to palliative care was undertaken. This should encourage physicians to examine their practice setting and determine which approach meets the needs of their ICU and begin to utilize palliative care earlier and more aggressively without fear of increasing mortality.

[email protected]

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN FRANCISCO – Palliative care in the intensive care unit reduces the length of stay in the ICU and the hospital without changing mortality rates or family satisfaction, according to a review of the literature.

Although measurements of family satisfaction overall didn’t change much from palliative care of a loved one in the ICU, some measures of components of satisfaction increased with palliative care, such as improved communication with the physician, better consensus around the goals of care, and decreased anxiety and depression in family members, reported Dr. Rebecca A. Aslakson of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and her colleagues.

Dr. Aslakson presented the findings at the Critical Care Congress, sponsored by the Society for Critical Care Medicine.

Dr. Aslakson and her associates were unable to perform a formal meta-analysis of the 37 published trials of palliative care in the ICU because of the heterogeneity of the studies, which looked at more than 40 different outcomes.

Instead, their systematic review grouped results under four outcomes that commonly were measured, and assessed those either by the number of studies or by the number of patients studied.

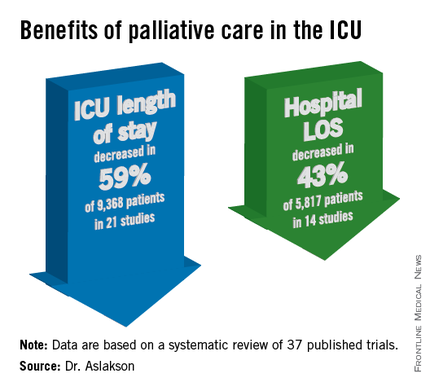

ICU length of stay decreased with palliative care in 13 of 21 studies (62%) that used this outcome and in 59% of 9,368 patients in those studies.

Hospital length of stay decreased with palliative care in 8 of 14 studies (57%) and in 43% of 5,817 patients. Family satisfaction did not decrease in any studies or families and increased in only 1 of 14 studies (7%) and in 2% of families of 4,927 patients, Dr. Aslakson and her colleagues reported (J. Palliat. Med. 2014;17:219-35).

Mortality rates did not change with palliative care in 14 of 16 studies (88%) that assessed mortality and in 57% of 5,969 patients in those studies. Mortality increased in one small study (6%) and decreased in one larger study (6%).

"Talking about big-picture issues and goals of care doesn’t lead to people dying," Dr. Aslakson said.

"No harm came in any of these studies." Some separate studies of palliative care outside of ICUs reported that this increases hope, "because people feel that they have more control over their choices and what’s happening to their loved ones," she added.

Integrative vs. consultative model

Dr. Aslakson and her associates also reviewed studies based on whether the interventions used integrative or consultative models of palliative care.

Generally, consultative models bring outsiders into the ICU to help provide palliative care, and integrative models train the ICU team to be the palliative care providers. In reality, the two models may overlap. For this review, the investigators applied mutually exclusive definitions to 36 of the studies.

In 18 studies of integrative interventions, members of the ICU team were the only caregivers in face-to-face interactions with the patient and families. In 18 studies of consultative interventions, palliative care providers included others besides the ICU team.

In the studies of integrative palliative care, ICU length of stay decreased with palliative care in four of nine studies (44%) that measured this outcome and in 52% of 6,963 patients in those studies, she reported. Hospital length of stay decreased in two of five studies (40%) and in 24% of 3,812 patients. Family satisfaction changed in none of 15 studies, and mortality decreased in 1 of 5 studies (20%) and in 34% of 3,807 patients.

In the studies of consultative care, ICU length of stay decreased with palliative care in 9 of 12 studies (75%) that measured this outcome and in 79% of 2,405 patients in those studies. Hospital length of stay decreased in six of nine studies (67%) and in 79% of 2,005 patients. Family satisfaction increased in one of four studies (25%) and in 21% of 429 patients. Mortality increased in 1 of 11 studies (9%) and in 5% of 2,162 patients.

One model isn’t necessarily better than the other, Dr. Aslakson said. Integrative palliative care may work best in a closed ICU with perhaps four or five intensivists in a relatively small unit. An integrative approach can be much more difficult in open or semiopen ICUs that have "40 different doctors floating around," she said. "We tried that in my unit, and it didn’t work that well."

Different ICUs need palliative care models that fit them. "Look at your unit, the way it works, and who the providers are, then look at the literature and see what matches that and what might work for your unit," she said.

Outcomes of better communication

A previous, separate review of the medical literature identified 21 controlled trials of 16 interventions to improve communication in ICUs between families and care providers. Overall, the interventions improved emotional outcomes for families and reduced ICU length of stay and treatment intensity (Chest 2011;139:543-54), she noted.

Yet another prior review of the literature reported that interventions to promote family meetings, use empathetic communication skills, and employ palliative care consultations improved family satisfaction and reduced ICU length of stay and the adverse effects of family bereavement (Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2009;15:569-77).

Dr. Aslakson reported having no financial disclosures.

Dr. Jennifer Cox, FCCP, comments: Dr. Aslakson and colleagues’ systematic review adds to the body of literature that demonstrates no mortality increase when palliative care measures are initiated in the ICU. Shorter lengths of stay both in the ICU and hospital were other positive outcomes noted without a significant change in patient or family satisfaction.

These findings were independent of whether an integrative or consultative approach to palliative care was undertaken. This should encourage physicians to examine their practice setting and determine which approach meets the needs of their ICU and begin to utilize palliative care earlier and more aggressively without fear of increasing mortality.

[email protected]

On Twitter @sherryboschert

Relatively few in ICUs get end-of-life dialogue training

SAN FRANCISCO – Despite training recommendations, half of physicians and less than a third of nurses surveyed in adult intensive care units at 56 California hospitals reported receiving formal training in talking with patients and families about the end of life.

A 2008 consensus statement by the American College of Critical Care Medicine included a recommendation for end-of-life communication skills training for clinicians to improve the care of patients dying in ICUs ((Crit. Care Med. 2008;36:953-63).

Dr. Matthew H.R. Anstey and his associates approached 149 California hospitals to gauge the extent of implementation of this recommendation. At 56 hospitals, doctors and nurses who work in adult ICUs voluntarily completed an anonymous web-based survey. Eighty-four percent of the 1,363 respondents were nurses, he reported in a poster presentation at the Critical Care Congress, sponsored by the Society for Critical Care Medicine.

Overall, 32% of the respondents said they had received formal training in communication skills. A significantly higher percentage of doctors had undergone training (50%) compared with nurses (29%), said Dr. Anstey, who is currently a lecturer in anesthesia at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Sixty-six percent of all respondents agreed that "nurses are present during the communication of end-of-life information to the family" at their institution. Nurses were significantly more likely to agree with this statement (69%) than were doctors (52%).

Both doctors and nurses were very supportive of the idea of formal communication training for ICU providers. When asked about possible strategies to reduce inappropriate care for ICU patients, 91% of respondents said communication training would have a positive effect, Dr. Anstey reported.

This could be accomplished by requiring ICU physicians to complete a communication training module for ongoing credentialing, he said in an e-mail interview. Either individual hospitals could require this as part of credentialing for privileges to work in the ICU, or state medical boards could require it, similar to the California Medical Board’s requirement that physicians obtain some continuing medical education in pain management, he suggested.

The characteristics of participating hospitals were similar to those of nonparticipating hospitals in the sizes of the hospitals and ICUs, their regional location in California, and the proportions of hospitals that are teaching facilities.

The 93 nonparticipating hospitals were significantly more likely to be for-profit hospitals (59%) compared with participating hospitals (7%), and significantly less likely to be part of a hospital system containing more than three hospitals (54%) compared with participating hospitals (75%).

Dr. Anstey reported having no financial disclosures. His research was in conjunction with a Commonwealth Fund Harkness Fellowship in Health Care Policy and Practice for which he was placed at Kaiser Permanente in California.

Dr. Paul A. Selecky, FCCP, comments: Physicians are notorious about not doing a good job of communicating with patients in general, and when you focus on a vital subject as end-of-life care, it is of even greater importance. The findings in this study are not surprising. The unanswered question is how to fix it.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN FRANCISCO – Despite training recommendations, half of physicians and less than a third of nurses surveyed in adult intensive care units at 56 California hospitals reported receiving formal training in talking with patients and families about the end of life.

A 2008 consensus statement by the American College of Critical Care Medicine included a recommendation for end-of-life communication skills training for clinicians to improve the care of patients dying in ICUs ((Crit. Care Med. 2008;36:953-63).

Dr. Matthew H.R. Anstey and his associates approached 149 California hospitals to gauge the extent of implementation of this recommendation. At 56 hospitals, doctors and nurses who work in adult ICUs voluntarily completed an anonymous web-based survey. Eighty-four percent of the 1,363 respondents were nurses, he reported in a poster presentation at the Critical Care Congress, sponsored by the Society for Critical Care Medicine.

Overall, 32% of the respondents said they had received formal training in communication skills. A significantly higher percentage of doctors had undergone training (50%) compared with nurses (29%), said Dr. Anstey, who is currently a lecturer in anesthesia at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Sixty-six percent of all respondents agreed that "nurses are present during the communication of end-of-life information to the family" at their institution. Nurses were significantly more likely to agree with this statement (69%) than were doctors (52%).

Both doctors and nurses were very supportive of the idea of formal communication training for ICU providers. When asked about possible strategies to reduce inappropriate care for ICU patients, 91% of respondents said communication training would have a positive effect, Dr. Anstey reported.

This could be accomplished by requiring ICU physicians to complete a communication training module for ongoing credentialing, he said in an e-mail interview. Either individual hospitals could require this as part of credentialing for privileges to work in the ICU, or state medical boards could require it, similar to the California Medical Board’s requirement that physicians obtain some continuing medical education in pain management, he suggested.

The characteristics of participating hospitals were similar to those of nonparticipating hospitals in the sizes of the hospitals and ICUs, their regional location in California, and the proportions of hospitals that are teaching facilities.

The 93 nonparticipating hospitals were significantly more likely to be for-profit hospitals (59%) compared with participating hospitals (7%), and significantly less likely to be part of a hospital system containing more than three hospitals (54%) compared with participating hospitals (75%).

Dr. Anstey reported having no financial disclosures. His research was in conjunction with a Commonwealth Fund Harkness Fellowship in Health Care Policy and Practice for which he was placed at Kaiser Permanente in California.

Dr. Paul A. Selecky, FCCP, comments: Physicians are notorious about not doing a good job of communicating with patients in general, and when you focus on a vital subject as end-of-life care, it is of even greater importance. The findings in this study are not surprising. The unanswered question is how to fix it.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN FRANCISCO – Despite training recommendations, half of physicians and less than a third of nurses surveyed in adult intensive care units at 56 California hospitals reported receiving formal training in talking with patients and families about the end of life.

A 2008 consensus statement by the American College of Critical Care Medicine included a recommendation for end-of-life communication skills training for clinicians to improve the care of patients dying in ICUs ((Crit. Care Med. 2008;36:953-63).

Dr. Matthew H.R. Anstey and his associates approached 149 California hospitals to gauge the extent of implementation of this recommendation. At 56 hospitals, doctors and nurses who work in adult ICUs voluntarily completed an anonymous web-based survey. Eighty-four percent of the 1,363 respondents were nurses, he reported in a poster presentation at the Critical Care Congress, sponsored by the Society for Critical Care Medicine.

Overall, 32% of the respondents said they had received formal training in communication skills. A significantly higher percentage of doctors had undergone training (50%) compared with nurses (29%), said Dr. Anstey, who is currently a lecturer in anesthesia at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Sixty-six percent of all respondents agreed that "nurses are present during the communication of end-of-life information to the family" at their institution. Nurses were significantly more likely to agree with this statement (69%) than were doctors (52%).

Both doctors and nurses were very supportive of the idea of formal communication training for ICU providers. When asked about possible strategies to reduce inappropriate care for ICU patients, 91% of respondents said communication training would have a positive effect, Dr. Anstey reported.

This could be accomplished by requiring ICU physicians to complete a communication training module for ongoing credentialing, he said in an e-mail interview. Either individual hospitals could require this as part of credentialing for privileges to work in the ICU, or state medical boards could require it, similar to the California Medical Board’s requirement that physicians obtain some continuing medical education in pain management, he suggested.

The characteristics of participating hospitals were similar to those of nonparticipating hospitals in the sizes of the hospitals and ICUs, their regional location in California, and the proportions of hospitals that are teaching facilities.

The 93 nonparticipating hospitals were significantly more likely to be for-profit hospitals (59%) compared with participating hospitals (7%), and significantly less likely to be part of a hospital system containing more than three hospitals (54%) compared with participating hospitals (75%).

Dr. Anstey reported having no financial disclosures. His research was in conjunction with a Commonwealth Fund Harkness Fellowship in Health Care Policy and Practice for which he was placed at Kaiser Permanente in California.

Dr. Paul A. Selecky, FCCP, comments: Physicians are notorious about not doing a good job of communicating with patients in general, and when you focus on a vital subject as end-of-life care, it is of even greater importance. The findings in this study are not surprising. The unanswered question is how to fix it.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

Major finding: Half of doctors and 29% of nurses in ICUs said they had received formal training in end-of-life communications.

Data source: A voluntary web-based survey of 1,363 doctors and nurses working in adult ICUs in 56 California hospitals.

Disclosures: Dr. Anstey reported having no financial disclosures. His research was in conjunction with a Commonwealth Fund Harkness Fellowship in Health Care Policy and Practice, for which he was placed at Kaiser Permanente in California.

Palliative care is not just for the dying

SAN FRANCISCO – Palliative care is not just for the dying.

Understanding that premise is the first step to integrating palliative care into intensive care units, Dr. Zara Cooper said. Palliative care treats patient illness and can be delivered concurrently in the ICU with curative care that treats disease.

As options for curative treatment decrease, the role of palliative care may increase and does not stop at the patient’s death. "It’s important that we provide ongoing bereavement support not only to family members and survivors but also to caregivers and members of our medical team," added Dr. Cooper, an assistant professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School and a surgical intensivist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Getting intensive care colleagues to agree on a definition of palliative care is the first barrier to integrating palliative care into an ICU, Dr. Cooper said. She paraphrased the World Health Organization’s definition by saying, "Palliative care makes patients feel better." It is specialized medical care that focuses on preventing and relieving symptoms, pain, and stress associated with life-threatening illness – whatever the diagnosis – and is appropriate at any stage in a serious illness.

Typically provided by a team, palliative care may involve physicians, nurses, social workers, pharmacists, chaplains, pain experts, ethicists, rehabilitation therapists, psychiatry consultants, and bereavement counselors. The team can take a load off busy intensivists by handling the often lengthy conversations with patients and families facing life-threatening illness, she said at the Critical Care Congress, sponsored by the Society for Critical Care Medicine.

Palliative care providers can be embedded in ICUs or in a team that’s available as consultants. "I think we have to do both" models, depending on the needs of individual institutions, said Dr. Cooper.

Once a definition is agreed upon, the next steps to convincing colleagues and administrators to make better use of palliative care are to make it relevant for them and to normalize its presence in the ICU, she said. "Palliative care is just as essential as med management, antibiotics, pharmacology – it’s part of what we do well."

Predicting which patients will die, and when, is difficult. Patient preferences for care or end-of-life treatment often are unclear. The goals of treatment depend on the patient’s condition and must be dynamic. "Is it end-of-life care if we don’t know the patient is dying?" she asked.

One way to consider which ICU patients might benefit from palliative care is to ask, "Would I be surprised if this patient died within a year?" even if discharged from the ICU or the hospital, she suggested.

Four studies in the medical literature separately reported that 20% of Americans die in the hospital after an ICU admission, 80% of deaths in ICUs occur after life support is withdrawn or withheld, nearly half of dying patients receive unwanted therapy, and a majority of dying patients experience pain and suffering, Dr. Cooper said. Five other studies reported high mortality rates in patients with sepsis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, ICU stays longer than 14 days, admission to long-term acute care, or initiation of dialysis in the elderly.

A recent study of 25,558 elderly patients undergoing emergency surgery reported 30-day mortality rates of 37% in those with preexisting do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders and 22% in those without DNR orders. Major complications occurred in more than 40% in each group (Ann. Surg. 2012;256:453-61). Risk factors increase the likelihood of death, but "all of these patients are experiencing serious illness" and would benefit from palliative care, Dr. Cooper said.

One recent study of 518 patients in three ICUs found good adherence to only two of nine palliative care processes – pain assessment and management. Interdisciplinary family meetings had been held by day 5 in the ICU for less than 20% of patients, and adherence to six other palliative care practices ranged from 8% to 43% (Crit. Care Med. 2012;40:1105-12).

Normalizing palliative care in the ICU means adopting the attitude that "it’s just part of what we do, the same way that we manage our vents, etc." Dr. Cooper said.

Adopting proactive screening criteria (patient factors) that trigger palliative care consultations would reduce utilization of ICUs without increasing mortality, and would increase the availability of palliative care for patients and families, according to a recent report from the Improving Palliative Care in the ICU Project’s advisory board (Crit. Care Med. 2013;41:2318-27).

The triggers should be specific to each ICU and patient population and developed through a process with stakeholders, with outcomes evaluated. "This is not a one-size-fits-all strategy," Dr. Cooper said. "The triggers in the MICU [medical ICU] and the SICU [surgical ICU] cannot be the same. It won’t work. I’ve actually seen that in my own institution," Dr. Cooper said.

The triggers also shouldn’t focus only on the patients most obviously likely to die or they will perpetuate the misconception that palliative care is only for the dying, she added.

To integrate palliative care into an ICU, "just do it," she said. "Commit yourself" to intensive symptom management and multidisciplinary family meetings within 72 hours of ICU admission. Institute an intensive communication plan to provide emotional, educational, and decision support for patients and families. Offer pastoral and psychosocial support. Start end-of-life-care discussions sooner, and provide bereavement services when patients die.

Lastly, don’t hesitate to bill insurers for these services, Dr. Cooper said. In-person or phone meetings about treatment options when the patient lacks the capacity to decide can be billed as critical care, as can discussions about DNR codes. Also bill for treating acute pain, agitation, delirium, and other life-threatening symptoms as critical care.

Dr. Cooper reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

|

| Dr. Geoffrey P. Dunn |

This is an excellent perspective on the ongoing assimilation of palliative care principles and practices into the venue where it is most needed. Dr. Cooper, who is board certified in hospice and palliative medicine in addition to her surgical certification, is eminently qualified to speak to this topic. She represents a new generation of surgeons who see the potential for palliative care principles and practices for all seriously ill surgical patients.

She is right in suggesting we understand palliative care as a way of caring, not a prognostic indicator. As far back as 1999, intensivist and pulmonologist Judith Nelson argued in a memorable editorial in Annals of Internal Medicine that we should not try to pick and choose who needs palliative care in the ICU setting because prognosis is so hard to determine, but rather meet the comfort and quality of life needs of all ICU patients and their families.

Geoffrey P. Dunn, M.D., an ACS Fellow based in Erie, Pa., is chair of the ACS Surgical Palliative Care Task Force.

|

| Dr. Geoffrey P. Dunn |

This is an excellent perspective on the ongoing assimilation of palliative care principles and practices into the venue where it is most needed. Dr. Cooper, who is board certified in hospice and palliative medicine in addition to her surgical certification, is eminently qualified to speak to this topic. She represents a new generation of surgeons who see the potential for palliative care principles and practices for all seriously ill surgical patients.

She is right in suggesting we understand palliative care as a way of caring, not a prognostic indicator. As far back as 1999, intensivist and pulmonologist Judith Nelson argued in a memorable editorial in Annals of Internal Medicine that we should not try to pick and choose who needs palliative care in the ICU setting because prognosis is so hard to determine, but rather meet the comfort and quality of life needs of all ICU patients and their families.

Geoffrey P. Dunn, M.D., an ACS Fellow based in Erie, Pa., is chair of the ACS Surgical Palliative Care Task Force.

|

| Dr. Geoffrey P. Dunn |

This is an excellent perspective on the ongoing assimilation of palliative care principles and practices into the venue where it is most needed. Dr. Cooper, who is board certified in hospice and palliative medicine in addition to her surgical certification, is eminently qualified to speak to this topic. She represents a new generation of surgeons who see the potential for palliative care principles and practices for all seriously ill surgical patients.

She is right in suggesting we understand palliative care as a way of caring, not a prognostic indicator. As far back as 1999, intensivist and pulmonologist Judith Nelson argued in a memorable editorial in Annals of Internal Medicine that we should not try to pick and choose who needs palliative care in the ICU setting because prognosis is so hard to determine, but rather meet the comfort and quality of life needs of all ICU patients and their families.

Geoffrey P. Dunn, M.D., an ACS Fellow based in Erie, Pa., is chair of the ACS Surgical Palliative Care Task Force.

SAN FRANCISCO – Palliative care is not just for the dying.

Understanding that premise is the first step to integrating palliative care into intensive care units, Dr. Zara Cooper said. Palliative care treats patient illness and can be delivered concurrently in the ICU with curative care that treats disease.

As options for curative treatment decrease, the role of palliative care may increase and does not stop at the patient’s death. "It’s important that we provide ongoing bereavement support not only to family members and survivors but also to caregivers and members of our medical team," added Dr. Cooper, an assistant professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School and a surgical intensivist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Getting intensive care colleagues to agree on a definition of palliative care is the first barrier to integrating palliative care into an ICU, Dr. Cooper said. She paraphrased the World Health Organization’s definition by saying, "Palliative care makes patients feel better." It is specialized medical care that focuses on preventing and relieving symptoms, pain, and stress associated with life-threatening illness – whatever the diagnosis – and is appropriate at any stage in a serious illness.

Typically provided by a team, palliative care may involve physicians, nurses, social workers, pharmacists, chaplains, pain experts, ethicists, rehabilitation therapists, psychiatry consultants, and bereavement counselors. The team can take a load off busy intensivists by handling the often lengthy conversations with patients and families facing life-threatening illness, she said at the Critical Care Congress, sponsored by the Society for Critical Care Medicine.

Palliative care providers can be embedded in ICUs or in a team that’s available as consultants. "I think we have to do both" models, depending on the needs of individual institutions, said Dr. Cooper.

Once a definition is agreed upon, the next steps to convincing colleagues and administrators to make better use of palliative care are to make it relevant for them and to normalize its presence in the ICU, she said. "Palliative care is just as essential as med management, antibiotics, pharmacology – it’s part of what we do well."

Predicting which patients will die, and when, is difficult. Patient preferences for care or end-of-life treatment often are unclear. The goals of treatment depend on the patient’s condition and must be dynamic. "Is it end-of-life care if we don’t know the patient is dying?" she asked.

One way to consider which ICU patients might benefit from palliative care is to ask, "Would I be surprised if this patient died within a year?" even if discharged from the ICU or the hospital, she suggested.

Four studies in the medical literature separately reported that 20% of Americans die in the hospital after an ICU admission, 80% of deaths in ICUs occur after life support is withdrawn or withheld, nearly half of dying patients receive unwanted therapy, and a majority of dying patients experience pain and suffering, Dr. Cooper said. Five other studies reported high mortality rates in patients with sepsis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, ICU stays longer than 14 days, admission to long-term acute care, or initiation of dialysis in the elderly.

A recent study of 25,558 elderly patients undergoing emergency surgery reported 30-day mortality rates of 37% in those with preexisting do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders and 22% in those without DNR orders. Major complications occurred in more than 40% in each group (Ann. Surg. 2012;256:453-61). Risk factors increase the likelihood of death, but "all of these patients are experiencing serious illness" and would benefit from palliative care, Dr. Cooper said.

One recent study of 518 patients in three ICUs found good adherence to only two of nine palliative care processes – pain assessment and management. Interdisciplinary family meetings had been held by day 5 in the ICU for less than 20% of patients, and adherence to six other palliative care practices ranged from 8% to 43% (Crit. Care Med. 2012;40:1105-12).

Normalizing palliative care in the ICU means adopting the attitude that "it’s just part of what we do, the same way that we manage our vents, etc." Dr. Cooper said.

Adopting proactive screening criteria (patient factors) that trigger palliative care consultations would reduce utilization of ICUs without increasing mortality, and would increase the availability of palliative care for patients and families, according to a recent report from the Improving Palliative Care in the ICU Project’s advisory board (Crit. Care Med. 2013;41:2318-27).

The triggers should be specific to each ICU and patient population and developed through a process with stakeholders, with outcomes evaluated. "This is not a one-size-fits-all strategy," Dr. Cooper said. "The triggers in the MICU [medical ICU] and the SICU [surgical ICU] cannot be the same. It won’t work. I’ve actually seen that in my own institution," Dr. Cooper said.

The triggers also shouldn’t focus only on the patients most obviously likely to die or they will perpetuate the misconception that palliative care is only for the dying, she added.

To integrate palliative care into an ICU, "just do it," she said. "Commit yourself" to intensive symptom management and multidisciplinary family meetings within 72 hours of ICU admission. Institute an intensive communication plan to provide emotional, educational, and decision support for patients and families. Offer pastoral and psychosocial support. Start end-of-life-care discussions sooner, and provide bereavement services when patients die.

Lastly, don’t hesitate to bill insurers for these services, Dr. Cooper said. In-person or phone meetings about treatment options when the patient lacks the capacity to decide can be billed as critical care, as can discussions about DNR codes. Also bill for treating acute pain, agitation, delirium, and other life-threatening symptoms as critical care.

Dr. Cooper reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN FRANCISCO – Palliative care is not just for the dying.

Understanding that premise is the first step to integrating palliative care into intensive care units, Dr. Zara Cooper said. Palliative care treats patient illness and can be delivered concurrently in the ICU with curative care that treats disease.

As options for curative treatment decrease, the role of palliative care may increase and does not stop at the patient’s death. "It’s important that we provide ongoing bereavement support not only to family members and survivors but also to caregivers and members of our medical team," added Dr. Cooper, an assistant professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School and a surgical intensivist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Getting intensive care colleagues to agree on a definition of palliative care is the first barrier to integrating palliative care into an ICU, Dr. Cooper said. She paraphrased the World Health Organization’s definition by saying, "Palliative care makes patients feel better." It is specialized medical care that focuses on preventing and relieving symptoms, pain, and stress associated with life-threatening illness – whatever the diagnosis – and is appropriate at any stage in a serious illness.

Typically provided by a team, palliative care may involve physicians, nurses, social workers, pharmacists, chaplains, pain experts, ethicists, rehabilitation therapists, psychiatry consultants, and bereavement counselors. The team can take a load off busy intensivists by handling the often lengthy conversations with patients and families facing life-threatening illness, she said at the Critical Care Congress, sponsored by the Society for Critical Care Medicine.

Palliative care providers can be embedded in ICUs or in a team that’s available as consultants. "I think we have to do both" models, depending on the needs of individual institutions, said Dr. Cooper.

Once a definition is agreed upon, the next steps to convincing colleagues and administrators to make better use of palliative care are to make it relevant for them and to normalize its presence in the ICU, she said. "Palliative care is just as essential as med management, antibiotics, pharmacology – it’s part of what we do well."

Predicting which patients will die, and when, is difficult. Patient preferences for care or end-of-life treatment often are unclear. The goals of treatment depend on the patient’s condition and must be dynamic. "Is it end-of-life care if we don’t know the patient is dying?" she asked.

One way to consider which ICU patients might benefit from palliative care is to ask, "Would I be surprised if this patient died within a year?" even if discharged from the ICU or the hospital, she suggested.

Four studies in the medical literature separately reported that 20% of Americans die in the hospital after an ICU admission, 80% of deaths in ICUs occur after life support is withdrawn or withheld, nearly half of dying patients receive unwanted therapy, and a majority of dying patients experience pain and suffering, Dr. Cooper said. Five other studies reported high mortality rates in patients with sepsis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, ICU stays longer than 14 days, admission to long-term acute care, or initiation of dialysis in the elderly.

A recent study of 25,558 elderly patients undergoing emergency surgery reported 30-day mortality rates of 37% in those with preexisting do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders and 22% in those without DNR orders. Major complications occurred in more than 40% in each group (Ann. Surg. 2012;256:453-61). Risk factors increase the likelihood of death, but "all of these patients are experiencing serious illness" and would benefit from palliative care, Dr. Cooper said.

One recent study of 518 patients in three ICUs found good adherence to only two of nine palliative care processes – pain assessment and management. Interdisciplinary family meetings had been held by day 5 in the ICU for less than 20% of patients, and adherence to six other palliative care practices ranged from 8% to 43% (Crit. Care Med. 2012;40:1105-12).

Normalizing palliative care in the ICU means adopting the attitude that "it’s just part of what we do, the same way that we manage our vents, etc." Dr. Cooper said.

Adopting proactive screening criteria (patient factors) that trigger palliative care consultations would reduce utilization of ICUs without increasing mortality, and would increase the availability of palliative care for patients and families, according to a recent report from the Improving Palliative Care in the ICU Project’s advisory board (Crit. Care Med. 2013;41:2318-27).

The triggers should be specific to each ICU and patient population and developed through a process with stakeholders, with outcomes evaluated. "This is not a one-size-fits-all strategy," Dr. Cooper said. "The triggers in the MICU [medical ICU] and the SICU [surgical ICU] cannot be the same. It won’t work. I’ve actually seen that in my own institution," Dr. Cooper said.

The triggers also shouldn’t focus only on the patients most obviously likely to die or they will perpetuate the misconception that palliative care is only for the dying, she added.

To integrate palliative care into an ICU, "just do it," she said. "Commit yourself" to intensive symptom management and multidisciplinary family meetings within 72 hours of ICU admission. Institute an intensive communication plan to provide emotional, educational, and decision support for patients and families. Offer pastoral and psychosocial support. Start end-of-life-care discussions sooner, and provide bereavement services when patients die.

Lastly, don’t hesitate to bill insurers for these services, Dr. Cooper said. In-person or phone meetings about treatment options when the patient lacks the capacity to decide can be billed as critical care, as can discussions about DNR codes. Also bill for treating acute pain, agitation, delirium, and other life-threatening symptoms as critical care.

Dr. Cooper reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CRITICAL CARE CONGRESS

Palliative care is not just for the dying

SAN FRANCISCO – Palliative care is not just for the dying.

Understanding that premise is the first step to integrating palliative care into intensive care units, Dr. Zara Cooper said. Palliative care treats patient illness and can be delivered concurrently in the ICU with curative care that treats disease.

As options for curative treatment decrease, the role of palliative care may increase and does not stop at the patient’s death. "It’s important that we provide ongoing bereavement support not only to family members and survivors but also to caregivers and members of our medical team," added Dr. Cooper, an assistant professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School and a surgical intensivist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Getting intensive care colleagues to agree on a definition of palliative care is the first barrier to integrating palliative care into an ICU, Dr. Cooper said. She paraphrased the World Health Organization’s definition by saying, "Palliative care makes patients feel better." It is specialized medical care that focuses on preventing and relieving symptoms, pain, and stress associated with life-threatening illness – whatever the diagnosis – and is appropriate at any stage in a serious illness.

Typically provided by a team, palliative care may involve physicians, nurses, social workers, pharmacists, chaplains, pain experts, ethicists, rehabilitation therapists, psychiatry consultants, and bereavement counselors. The team can take a load off busy intensivists by handling the often lengthy conversations with patients and families facing life-threatening illness, she said at the Critical Care Congress, sponsored by the Society for Critical Care Medicine.

Palliative care providers can be embedded in ICUs or in a team that’s available as consultants. "I think we have to do both" models, depending on the needs of individual institutions, said Dr. Cooper.

Once a definition is agreed upon, the next steps to convincing colleagues and administrators to make better use of palliative care are to make it relevant for them and to normalize its presence in the ICU, she said. "Palliative care is just as essential as med management, antibiotics, pharmacology – it’s part of what we do well."

Predicting which patients will die, and when, is difficult. Patient preferences for care or end-of-life treatment often are unclear. The goals of treatment depend on the patient’s condition and must be dynamic. "Is it end-of-life care if we don’t know the patient is dying?" she asked.

One way to consider which ICU patients might benefit from palliative care is to ask, "Would I be surprised if this patient died within a year?" even if discharged from the ICU or the hospital, she suggested.

Four studies in the medical literature separately reported that 20% of Americans die in the hospital after an ICU admission, 80% of deaths in ICUs occur after life support is withdrawn or withheld, nearly half of dying patients receive unwanted therapy, and a majority of dying patients experience pain and suffering, Dr. Cooper said. Five other studies reported high mortality rates in patients with sepsis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, ICU stays longer than 14 days, admission to long-term acute care, or initiation of dialysis in the elderly.

A recent study of 25,558 elderly patients undergoing emergency surgery reported 30-day mortality rates of 37% in those with preexisting do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders and 22% in those without DNR orders. Major complications occurred in more than 40% in each group (Ann. Surg. 2012;256:453-61). Risk factors increase the likelihood of death, but "all of these patients are experiencing serious illness" and would benefit from palliative care, Dr. Cooper said.

One recent study of 518 patients in three ICUs found good adherence to only two of nine palliative care processes – pain assessment and management. Interdisciplinary family meetings had been held by day 5 in the ICU for less than 20% of patients, and adherence to six other palliative care practices ranged from 8% to 43% (Crit. Care Med. 2012;40:1105-12).

Normalizing palliative care in the ICU means adopting the attitude that "it’s just part of what we do, the same way that we manage our vents, etc." Dr. Cooper said.

Adopting proactive screening criteria (patient factors) that trigger palliative care consultations would reduce utilization of ICUs without increasing mortality, and would increase the availability of palliative care for patients and families, according to a recent report from the Improving Palliative Care in the ICU Project’s advisory board (Crit. Care Med. 2013;41:2318-27).

The triggers should be specific to each ICU and patient population and developed through a process with stakeholders, with outcomes evaluated. "This is not a one-size-fits-all strategy," Dr. Cooper said. "The triggers in the MICU [medical ICU] and the SICU [surgical ICU] cannot be the same. It won’t work. I’ve actually seen that in my own institution," Dr. Cooper said.

The triggers also shouldn’t focus only on the patients most obviously likely to die or they will perpetuate the misconception that palliative care is only for the dying, she added.

To integrate palliative care into an ICU, "just do it," she said. "Commit yourself" to intensive symptom management and multidisciplinary family meetings within 72 hours of ICU admission. Institute an intensive communication plan to provide emotional, educational, and decision support for patients and families. Offer pastoral and psychosocial support. Start end-of-life-care discussions sooner, and provide bereavement services when patients die.

Lastly, don’t hesitate to bill insurers for these services, Dr. Cooper said. In-person or phone meetings about treatment options when the patient lacks the capacity to decide can be billed as critical care, as can discussions about DNR codes. Also bill for treating acute pain, agitation, delirium, and other life-threatening symptoms as critical care.

Dr. Cooper reported having no financial disclosures.

If you’re interested in more about these topics, you can join a discussion on this topic within the Critical Care e-Community. Simply log in to ecommunity.chestnet.org and find the Critical Care group. If you’re not part of the Critical Care NetWork, log in to chestnet.org and add the Critical Care NetWork to your profile.

Questions? Contact [email protected].

On Twitter @sherryboschert

|

| Dr. Geoffrey P. Dunn |

This is an excellent perspective on the ongoing assimilation of palliative care principles and practices into the venue where it is most needed. Dr. Cooper, who is board certified in hospice and palliative medicine in addition to her surgical certification, is eminently qualified to speak to this topic. She represents a new generation of surgeons who see the potential for palliative care principles and practices for all seriously ill surgical patients.

She is right in suggesting we understand palliative care as a way of caring, not a prognostic indicator. As far back as 1999, intensivist and pulmonologist Judith Nelson argued in a memorable editorial in Annals of Internal Medicine that we should not try to pick and choose who needs palliative care in the ICU setting because prognosis is so hard to determine, but rather meet the comfort and quality of life needs of all ICU patients and their families.

Geoffrey P. Dunn, M.D., an ACS Fellow based in Erie, Pa., is chair of the ACS Surgical Palliative Care Task Force.

|

| Dr. Geoffrey P. Dunn |

This is an excellent perspective on the ongoing assimilation of palliative care principles and practices into the venue where it is most needed. Dr. Cooper, who is board certified in hospice and palliative medicine in addition to her surgical certification, is eminently qualified to speak to this topic. She represents a new generation of surgeons who see the potential for palliative care principles and practices for all seriously ill surgical patients.

She is right in suggesting we understand palliative care as a way of caring, not a prognostic indicator. As far back as 1999, intensivist and pulmonologist Judith Nelson argued in a memorable editorial in Annals of Internal Medicine that we should not try to pick and choose who needs palliative care in the ICU setting because prognosis is so hard to determine, but rather meet the comfort and quality of life needs of all ICU patients and their families.

Geoffrey P. Dunn, M.D., an ACS Fellow based in Erie, Pa., is chair of the ACS Surgical Palliative Care Task Force.

|

| Dr. Geoffrey P. Dunn |

This is an excellent perspective on the ongoing assimilation of palliative care principles and practices into the venue where it is most needed. Dr. Cooper, who is board certified in hospice and palliative medicine in addition to her surgical certification, is eminently qualified to speak to this topic. She represents a new generation of surgeons who see the potential for palliative care principles and practices for all seriously ill surgical patients.

She is right in suggesting we understand palliative care as a way of caring, not a prognostic indicator. As far back as 1999, intensivist and pulmonologist Judith Nelson argued in a memorable editorial in Annals of Internal Medicine that we should not try to pick and choose who needs palliative care in the ICU setting because prognosis is so hard to determine, but rather meet the comfort and quality of life needs of all ICU patients and their families.

Geoffrey P. Dunn, M.D., an ACS Fellow based in Erie, Pa., is chair of the ACS Surgical Palliative Care Task Force.

SAN FRANCISCO – Palliative care is not just for the dying.

Understanding that premise is the first step to integrating palliative care into intensive care units, Dr. Zara Cooper said. Palliative care treats patient illness and can be delivered concurrently in the ICU with curative care that treats disease.

As options for curative treatment decrease, the role of palliative care may increase and does not stop at the patient’s death. "It’s important that we provide ongoing bereavement support not only to family members and survivors but also to caregivers and members of our medical team," added Dr. Cooper, an assistant professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School and a surgical intensivist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Getting intensive care colleagues to agree on a definition of palliative care is the first barrier to integrating palliative care into an ICU, Dr. Cooper said. She paraphrased the World Health Organization’s definition by saying, "Palliative care makes patients feel better." It is specialized medical care that focuses on preventing and relieving symptoms, pain, and stress associated with life-threatening illness – whatever the diagnosis – and is appropriate at any stage in a serious illness.

Typically provided by a team, palliative care may involve physicians, nurses, social workers, pharmacists, chaplains, pain experts, ethicists, rehabilitation therapists, psychiatry consultants, and bereavement counselors. The team can take a load off busy intensivists by handling the often lengthy conversations with patients and families facing life-threatening illness, she said at the Critical Care Congress, sponsored by the Society for Critical Care Medicine.

Palliative care providers can be embedded in ICUs or in a team that’s available as consultants. "I think we have to do both" models, depending on the needs of individual institutions, said Dr. Cooper.

Once a definition is agreed upon, the next steps to convincing colleagues and administrators to make better use of palliative care are to make it relevant for them and to normalize its presence in the ICU, she said. "Palliative care is just as essential as med management, antibiotics, pharmacology – it’s part of what we do well."

Predicting which patients will die, and when, is difficult. Patient preferences for care or end-of-life treatment often are unclear. The goals of treatment depend on the patient’s condition and must be dynamic. "Is it end-of-life care if we don’t know the patient is dying?" she asked.

One way to consider which ICU patients might benefit from palliative care is to ask, "Would I be surprised if this patient died within a year?" even if discharged from the ICU or the hospital, she suggested.

Four studies in the medical literature separately reported that 20% of Americans die in the hospital after an ICU admission, 80% of deaths in ICUs occur after life support is withdrawn or withheld, nearly half of dying patients receive unwanted therapy, and a majority of dying patients experience pain and suffering, Dr. Cooper said. Five other studies reported high mortality rates in patients with sepsis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, ICU stays longer than 14 days, admission to long-term acute care, or initiation of dialysis in the elderly.

A recent study of 25,558 elderly patients undergoing emergency surgery reported 30-day mortality rates of 37% in those with preexisting do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders and 22% in those without DNR orders. Major complications occurred in more than 40% in each group (Ann. Surg. 2012;256:453-61). Risk factors increase the likelihood of death, but "all of these patients are experiencing serious illness" and would benefit from palliative care, Dr. Cooper said.

One recent study of 518 patients in three ICUs found good adherence to only two of nine palliative care processes – pain assessment and management. Interdisciplinary family meetings had been held by day 5 in the ICU for less than 20% of patients, and adherence to six other palliative care practices ranged from 8% to 43% (Crit. Care Med. 2012;40:1105-12).

Normalizing palliative care in the ICU means adopting the attitude that "it’s just part of what we do, the same way that we manage our vents, etc." Dr. Cooper said.

Adopting proactive screening criteria (patient factors) that trigger palliative care consultations would reduce utilization of ICUs without increasing mortality, and would increase the availability of palliative care for patients and families, according to a recent report from the Improving Palliative Care in the ICU Project’s advisory board (Crit. Care Med. 2013;41:2318-27).

The triggers should be specific to each ICU and patient population and developed through a process with stakeholders, with outcomes evaluated. "This is not a one-size-fits-all strategy," Dr. Cooper said. "The triggers in the MICU [medical ICU] and the SICU [surgical ICU] cannot be the same. It won’t work. I’ve actually seen that in my own institution," Dr. Cooper said.

The triggers also shouldn’t focus only on the patients most obviously likely to die or they will perpetuate the misconception that palliative care is only for the dying, she added.

To integrate palliative care into an ICU, "just do it," she said. "Commit yourself" to intensive symptom management and multidisciplinary family meetings within 72 hours of ICU admission. Institute an intensive communication plan to provide emotional, educational, and decision support for patients and families. Offer pastoral and psychosocial support. Start end-of-life-care discussions sooner, and provide bereavement services when patients die.

Lastly, don’t hesitate to bill insurers for these services, Dr. Cooper said. In-person or phone meetings about treatment options when the patient lacks the capacity to decide can be billed as critical care, as can discussions about DNR codes. Also bill for treating acute pain, agitation, delirium, and other life-threatening symptoms as critical care.

Dr. Cooper reported having no financial disclosures.

If you’re interested in more about these topics, you can join a discussion on this topic within the Critical Care e-Community. Simply log in to ecommunity.chestnet.org and find the Critical Care group. If you’re not part of the Critical Care NetWork, log in to chestnet.org and add the Critical Care NetWork to your profile.

Questions? Contact [email protected].

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN FRANCISCO – Palliative care is not just for the dying.

Understanding that premise is the first step to integrating palliative care into intensive care units, Dr. Zara Cooper said. Palliative care treats patient illness and can be delivered concurrently in the ICU with curative care that treats disease.

As options for curative treatment decrease, the role of palliative care may increase and does not stop at the patient’s death. "It’s important that we provide ongoing bereavement support not only to family members and survivors but also to caregivers and members of our medical team," added Dr. Cooper, an assistant professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School and a surgical intensivist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Getting intensive care colleagues to agree on a definition of palliative care is the first barrier to integrating palliative care into an ICU, Dr. Cooper said. She paraphrased the World Health Organization’s definition by saying, "Palliative care makes patients feel better." It is specialized medical care that focuses on preventing and relieving symptoms, pain, and stress associated with life-threatening illness – whatever the diagnosis – and is appropriate at any stage in a serious illness.

Typically provided by a team, palliative care may involve physicians, nurses, social workers, pharmacists, chaplains, pain experts, ethicists, rehabilitation therapists, psychiatry consultants, and bereavement counselors. The team can take a load off busy intensivists by handling the often lengthy conversations with patients and families facing life-threatening illness, she said at the Critical Care Congress, sponsored by the Society for Critical Care Medicine.

Palliative care providers can be embedded in ICUs or in a team that’s available as consultants. "I think we have to do both" models, depending on the needs of individual institutions, said Dr. Cooper.

Once a definition is agreed upon, the next steps to convincing colleagues and administrators to make better use of palliative care are to make it relevant for them and to normalize its presence in the ICU, she said. "Palliative care is just as essential as med management, antibiotics, pharmacology – it’s part of what we do well."

Predicting which patients will die, and when, is difficult. Patient preferences for care or end-of-life treatment often are unclear. The goals of treatment depend on the patient’s condition and must be dynamic. "Is it end-of-life care if we don’t know the patient is dying?" she asked.

One way to consider which ICU patients might benefit from palliative care is to ask, "Would I be surprised if this patient died within a year?" even if discharged from the ICU or the hospital, she suggested.

Four studies in the medical literature separately reported that 20% of Americans die in the hospital after an ICU admission, 80% of deaths in ICUs occur after life support is withdrawn or withheld, nearly half of dying patients receive unwanted therapy, and a majority of dying patients experience pain and suffering, Dr. Cooper said. Five other studies reported high mortality rates in patients with sepsis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, ICU stays longer than 14 days, admission to long-term acute care, or initiation of dialysis in the elderly.

A recent study of 25,558 elderly patients undergoing emergency surgery reported 30-day mortality rates of 37% in those with preexisting do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders and 22% in those without DNR orders. Major complications occurred in more than 40% in each group (Ann. Surg. 2012;256:453-61). Risk factors increase the likelihood of death, but "all of these patients are experiencing serious illness" and would benefit from palliative care, Dr. Cooper said.

One recent study of 518 patients in three ICUs found good adherence to only two of nine palliative care processes – pain assessment and management. Interdisciplinary family meetings had been held by day 5 in the ICU for less than 20% of patients, and adherence to six other palliative care practices ranged from 8% to 43% (Crit. Care Med. 2012;40:1105-12).

Normalizing palliative care in the ICU means adopting the attitude that "it’s just part of what we do, the same way that we manage our vents, etc." Dr. Cooper said.

Adopting proactive screening criteria (patient factors) that trigger palliative care consultations would reduce utilization of ICUs without increasing mortality, and would increase the availability of palliative care for patients and families, according to a recent report from the Improving Palliative Care in the ICU Project’s advisory board (Crit. Care Med. 2013;41:2318-27).

The triggers should be specific to each ICU and patient population and developed through a process with stakeholders, with outcomes evaluated. "This is not a one-size-fits-all strategy," Dr. Cooper said. "The triggers in the MICU [medical ICU] and the SICU [surgical ICU] cannot be the same. It won’t work. I’ve actually seen that in my own institution," Dr. Cooper said.

The triggers also shouldn’t focus only on the patients most obviously likely to die or they will perpetuate the misconception that palliative care is only for the dying, she added.

To integrate palliative care into an ICU, "just do it," she said. "Commit yourself" to intensive symptom management and multidisciplinary family meetings within 72 hours of ICU admission. Institute an intensive communication plan to provide emotional, educational, and decision support for patients and families. Offer pastoral and psychosocial support. Start end-of-life-care discussions sooner, and provide bereavement services when patients die.

Lastly, don’t hesitate to bill insurers for these services, Dr. Cooper said. In-person or phone meetings about treatment options when the patient lacks the capacity to decide can be billed as critical care, as can discussions about DNR codes. Also bill for treating acute pain, agitation, delirium, and other life-threatening symptoms as critical care.

Dr. Cooper reported having no financial disclosures.

If you’re interested in more about these topics, you can join a discussion on this topic within the Critical Care e-Community. Simply log in to ecommunity.chestnet.org and find the Critical Care group. If you’re not part of the Critical Care NetWork, log in to chestnet.org and add the Critical Care NetWork to your profile.

Questions? Contact [email protected].

On Twitter @sherryboschert

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CRITICAL CARE CONGRESS

Hypothermia associated with persistent lymphopenia in sepsis

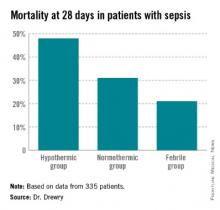

SAN FRANCISCO – Patients with sepsis had significantly higher rates of persistent lymphopenia, 28-day mortality, and 1-year mortality if they were hypothermic, compared with normothermic patients in a small retrospective study.

In the study, 32 of 58 septic patients who were hypothermic within 24 hours of their blood cultures developed persistent lymphopenia (55%), compared with 43% of 183 normothermic patients and 48% of 204 febrile patients.

Dr. Anne Drewry reported that hypothermia was associated with a nearly tripled risk for persistent lymphopenia (odds ratio, 2.7) compared with normothermic patients in a multivariate logistic regression analysis to account for confounding variables. The likelihood of persistent lymphopenia in febrile patients was not significantly different from that of normothermic patients.

The significantly higher risk of persistent lymphopenia in patients with hypothermia compared with normothermia was accompanied by significantly higher risk for some secondary adverse outcomes in the observational cohort study, she reported at the Critical Care Congress, sponsored by the Society for Critical Care Medicine.

Thirty-nine hypothermic patients developed septic shock (67%), compared with 55% of normothermic patients and 47% of febrile patients.

Mortality rates at 28 days were 48% in the hypothermic group (28 patients), 31% in the normothermic group, and 21% in the febrile group (which was significantly lower compared with the normothermic patients). At 1 year, 35 hypothermic patients had died (60%) compared with 45% of normothermic patients and 39% of febrile patients, she said.

"Hypothermic patients may be candidates for early treatment with agents that reverse sepsis-induced lymphopenia in future clinical trials," said Dr. Drewry of Washington University, St. Louis.

She and her associates studied data on 455 patients hospitalized between January 2010 and July 2012 and diagnosed with sepsis, and whose blood cultures were positive for bacterial or fungal organisms within 5 days of admission. They considered patients to be hypothermic if their most extreme temperature values within the first 24 hours of blood cultures were less than 36° C and to be febrile if the temperature values were 38.3° C or higher.

Data on 335 patients were analyzed for the primary outcome of persistent lymphopenia, not counting 110 patients who died or were discharged prior to day 4 after sepsis diagnosis or who had no blood counts drawn on day 4.

Mean APACHE II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II) scores at baseline were 22 in the hypothermic group, significantly higher than the mean score of 16 in normothermic patients and 17 in febrile patients. Higher APACHE II scores were the only variable besides hypothermia to be significantly associated with increased risk of persistent lymphopenia; higher scores conferred a 7% increase in risk.

Hypothermic patients were significantly more likely to be infected with gram-negative organisms (50%) than were normothermic patients (36%) or febrile patients (34%).

The three groups did not differ significantly in rates of acute kidney injury, secondary infection, or need for mechanical ventilation, among secondary outcomes in a univariate analysis. Factors that were not significantly associated with persistent lymphopenia risk in the multivariable analysis included the presence of comorbidity and the type of organism (gram-positive, gram-negative, fungal, or polymicrobial).

Hypothermia occurs in 10%-25% of critically ill patients with sepsis, Dr. Drewry said. A prior study by other investigators suggested that severely septic patients with hypothermia are older, have more severe disease, and are at higher risk of death than normothermic or febrile patients (Crit. Care 2013;17:R271).

"Previous data from our group suggests that persistent lymphopenia predicts mortality and secondary infection in septic patients and may be a marker for sepsis-induced immunosuppression" even after accounting for possible confounders, Dr. Drewry said.

It’s unclear why some patients don’t mount a fever in response to infection and why these patients have worse outcomes, she added. "Our overarching hypothesis is that hypothermia in response to infection is a sign of an underlying predisposition to sepsis-induced immunosuppression."

The study excluded patients diagnosed with hematological or immunological disease and patients treated with chemotherapy or corticosteroids while hospitalized or within 6 months before admission.

Dr. Drewry reported having no financial disclosures.

[email protected] On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN FRANCISCO – Patients with sepsis had significantly higher rates of persistent lymphopenia, 28-day mortality, and 1-year mortality if they were hypothermic, compared with normothermic patients in a small retrospective study.

In the study, 32 of 58 septic patients who were hypothermic within 24 hours of their blood cultures developed persistent lymphopenia (55%), compared with 43% of 183 normothermic patients and 48% of 204 febrile patients.

Dr. Anne Drewry reported that hypothermia was associated with a nearly tripled risk for persistent lymphopenia (odds ratio, 2.7) compared with normothermic patients in a multivariate logistic regression analysis to account for confounding variables. The likelihood of persistent lymphopenia in febrile patients was not significantly different from that of normothermic patients.