User login

Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents & Chemotherapy (ICAAC)

Canadian hospital’s Ebola scare exposes lack of readiness

WASHINGTON – While the U.S. waits for its first potential case of Ebola from a traveler, earlier this spring, officials at one hospital in Canada thought that they had a case and found themselves woefully unprepared.

In late March, a man who had returned from Liberia and had a fever of unknown origin, was admitted through the emergency department to the intensive care unit at St. Paul’s Hospital in Saskatoon, Sask. The clinicians suspected Ebola, but weren’t sure and late that night called the Saskatoon regional health department for a consultation.

Dr. Joseph Blondeau, interim head of pathology and laboratory medicine for the Saskatoon Health Region and the Royal University Hospital, took the call and set a process in motion that had been established for just such a moment, but later proved to have a variety of shortcomings, said Dr. Blondeau during a presentation at the Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

Initially, the ICU clinicians treated the man empirically with a third-generation cephalosporin and vancomycin. There were still not enough details to make a definitive diagnosis, but by early the next morning there was a high level of suspicion. The patient was hemorrhaging from his eye, there was blood in his nasogastric tube, some rectal bleeding, and a diffuse and nonspecific rash.

Dr. Blondeau ordered all specimens from the man to be quarantined, and he activated the emergency response system for Canada. At that time, there were 27 cases in Liberia, with a 40% mortality rate.

Alarmingly, one of the patient’s cerebrospinal fluid specimens had leaked in transit from St. Paul’s Hospital to a biocontainment lab at the Royal University hospital. A technician at the lab attempted to clean the container and was potentially exposed.

Both St. Paul and Royal University hospitals decided they needed a communication strategy to help allay fear and anxiety among the staff. Many were questioning why the patient was not elevated to a high infection threat when admitted to the ICU, and why higher-level precautions had not been put into place earlier.

On his way to an emergency meeting at St. Paul’s to discuss these issues, Dr. Blondeau received a call from the director of one of Canada’s biosafety level 4 labs, the National Microbiology Lab in Winnipeg, Man., who said that it was likely the patient had Ebola.

“At that point in time all hell broke loose,” said Dr. Blondeau.

The patient’s specimens needed to be immediately transported for confirmation to that national lab, a 9-hour drive from Saskatoon. The regular couriers weren’t interested. Dr. Blondeau volunteered, initially thinking he would drive them.

The specimens were prepared and packaged for containment, but the government made the decision to transport them by jet instead.

Even so, Dr. Blondeau had to drive the specimens to the air ambulance that was waiting at the Saskatoon airport. He wondered whether that was the right decision. There were questions as to whether law enforcement should be informed of the transport – what if he had an accident? He put a sign in the windshield stating that he was transporting a potential Ebola specimen as a means of making it look official, and so that no one would mistake him for a terrorist. No one had worked out whether he should accompany the specimens to Winnipeg to maintain a chain of control. He did not go.

Simultaneously, the health authorities began trying to track down all of the patient’s contacts, from arrival in the country, through an urgent clinic visit, a busy emergency room, and staff and family visits after ICU admission.

Meanwhile, the patient was deteriorating and was already ventilated and required cardiovascular support. Dr. Blondeau began discussions to bring a more sophisticated mobile lab to Saskatoon so that the patient could be repeatedly tested on-site.

“I can say with certainty that there were not many people in the province of Saskatchewan who fully understood what was about to happen should this patient have tested positive for Ebola,” said Dr. Blondeau. “We were learning as we went.”

The plans were changing by the moment, he said.

And, he said, he still had many concerns about how the situation would be perceived by those inside and outside the hospital. There was a potential for public panic and for a breach of the patient’s and family’s privacy.

Among the staff, “there was tremendous fear and panic,” Dr. Blondeau said. The spouse of the lab technician who had a potential exposure wanted her to quit her job. Another technician was spreading incorrect information, he said.

While staff worried about their own exposure and whether they had exposed their families, the patient was still critically ill and needed care and acute testing.

Then, just 24 hours after the patient had been admitted, it was determined that he did not have Ebola or any other viral hemorrhagic fever.

But “we still didn’t have a diagnosis,” said Dr. Blondeau.

He ordered routine microbiology testing on all the specimens. A day later, it looked like the culprit was Staphylococcus aureus. Further testing confirmed that it was indeed S. aureus and that it was a methicillin-susceptible strain.

Officials and staff went back to routine care processes.

In retrospect, there was much to be concerned about, said Dr. Blondeau. Use of personal protective equipment was inconsistent, which could have led to exposures. There was uncertainty about how to keep the environment clean, including linens and uniforms. For instance, he noted, many health care staff wear uniforms to work or wear them home. “Is this a practice we should be endorsing?” he asked.

There were potential problems with the physical space; for instance, some patient room doors did not close tightly.

On the plus side, no staff refused to care for the patient or to do what was asked, said Dr. Blondeau.

The entire 96-hour experience “was exciting but it was terrifying,” he said.

The lack of preparedness and the lack of a more tightly-knit lab system in the U.S. and Canada are warning signs, he said.

“The reality is we’re only the next landing flight away from a potential infectious disease threat,” said Dr. Blondeau.

On Aug. 1, Saskatoon health authorities received an alert that a passenger on an inbound flight from Senegal had many of the symptoms of a viral hemorrhagic fever: vomiting, diarrhea, and headache. They put their response system in place, and “were much better prepared the second time around,” he said, adding, “but we aren’t where we need to be.”

Dr. Blondeau reported having no conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @aliciaault

WASHINGTON – While the U.S. waits for its first potential case of Ebola from a traveler, earlier this spring, officials at one hospital in Canada thought that they had a case and found themselves woefully unprepared.

In late March, a man who had returned from Liberia and had a fever of unknown origin, was admitted through the emergency department to the intensive care unit at St. Paul’s Hospital in Saskatoon, Sask. The clinicians suspected Ebola, but weren’t sure and late that night called the Saskatoon regional health department for a consultation.

Dr. Joseph Blondeau, interim head of pathology and laboratory medicine for the Saskatoon Health Region and the Royal University Hospital, took the call and set a process in motion that had been established for just such a moment, but later proved to have a variety of shortcomings, said Dr. Blondeau during a presentation at the Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

Initially, the ICU clinicians treated the man empirically with a third-generation cephalosporin and vancomycin. There were still not enough details to make a definitive diagnosis, but by early the next morning there was a high level of suspicion. The patient was hemorrhaging from his eye, there was blood in his nasogastric tube, some rectal bleeding, and a diffuse and nonspecific rash.

Dr. Blondeau ordered all specimens from the man to be quarantined, and he activated the emergency response system for Canada. At that time, there were 27 cases in Liberia, with a 40% mortality rate.

Alarmingly, one of the patient’s cerebrospinal fluid specimens had leaked in transit from St. Paul’s Hospital to a biocontainment lab at the Royal University hospital. A technician at the lab attempted to clean the container and was potentially exposed.

Both St. Paul and Royal University hospitals decided they needed a communication strategy to help allay fear and anxiety among the staff. Many were questioning why the patient was not elevated to a high infection threat when admitted to the ICU, and why higher-level precautions had not been put into place earlier.

On his way to an emergency meeting at St. Paul’s to discuss these issues, Dr. Blondeau received a call from the director of one of Canada’s biosafety level 4 labs, the National Microbiology Lab in Winnipeg, Man., who said that it was likely the patient had Ebola.

“At that point in time all hell broke loose,” said Dr. Blondeau.

The patient’s specimens needed to be immediately transported for confirmation to that national lab, a 9-hour drive from Saskatoon. The regular couriers weren’t interested. Dr. Blondeau volunteered, initially thinking he would drive them.

The specimens were prepared and packaged for containment, but the government made the decision to transport them by jet instead.

Even so, Dr. Blondeau had to drive the specimens to the air ambulance that was waiting at the Saskatoon airport. He wondered whether that was the right decision. There were questions as to whether law enforcement should be informed of the transport – what if he had an accident? He put a sign in the windshield stating that he was transporting a potential Ebola specimen as a means of making it look official, and so that no one would mistake him for a terrorist. No one had worked out whether he should accompany the specimens to Winnipeg to maintain a chain of control. He did not go.

Simultaneously, the health authorities began trying to track down all of the patient’s contacts, from arrival in the country, through an urgent clinic visit, a busy emergency room, and staff and family visits after ICU admission.

Meanwhile, the patient was deteriorating and was already ventilated and required cardiovascular support. Dr. Blondeau began discussions to bring a more sophisticated mobile lab to Saskatoon so that the patient could be repeatedly tested on-site.

“I can say with certainty that there were not many people in the province of Saskatchewan who fully understood what was about to happen should this patient have tested positive for Ebola,” said Dr. Blondeau. “We were learning as we went.”

The plans were changing by the moment, he said.

And, he said, he still had many concerns about how the situation would be perceived by those inside and outside the hospital. There was a potential for public panic and for a breach of the patient’s and family’s privacy.

Among the staff, “there was tremendous fear and panic,” Dr. Blondeau said. The spouse of the lab technician who had a potential exposure wanted her to quit her job. Another technician was spreading incorrect information, he said.

While staff worried about their own exposure and whether they had exposed their families, the patient was still critically ill and needed care and acute testing.

Then, just 24 hours after the patient had been admitted, it was determined that he did not have Ebola or any other viral hemorrhagic fever.

But “we still didn’t have a diagnosis,” said Dr. Blondeau.

He ordered routine microbiology testing on all the specimens. A day later, it looked like the culprit was Staphylococcus aureus. Further testing confirmed that it was indeed S. aureus and that it was a methicillin-susceptible strain.

Officials and staff went back to routine care processes.

In retrospect, there was much to be concerned about, said Dr. Blondeau. Use of personal protective equipment was inconsistent, which could have led to exposures. There was uncertainty about how to keep the environment clean, including linens and uniforms. For instance, he noted, many health care staff wear uniforms to work or wear them home. “Is this a practice we should be endorsing?” he asked.

There were potential problems with the physical space; for instance, some patient room doors did not close tightly.

On the plus side, no staff refused to care for the patient or to do what was asked, said Dr. Blondeau.

The entire 96-hour experience “was exciting but it was terrifying,” he said.

The lack of preparedness and the lack of a more tightly-knit lab system in the U.S. and Canada are warning signs, he said.

“The reality is we’re only the next landing flight away from a potential infectious disease threat,” said Dr. Blondeau.

On Aug. 1, Saskatoon health authorities received an alert that a passenger on an inbound flight from Senegal had many of the symptoms of a viral hemorrhagic fever: vomiting, diarrhea, and headache. They put their response system in place, and “were much better prepared the second time around,” he said, adding, “but we aren’t where we need to be.”

Dr. Blondeau reported having no conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @aliciaault

WASHINGTON – While the U.S. waits for its first potential case of Ebola from a traveler, earlier this spring, officials at one hospital in Canada thought that they had a case and found themselves woefully unprepared.

In late March, a man who had returned from Liberia and had a fever of unknown origin, was admitted through the emergency department to the intensive care unit at St. Paul’s Hospital in Saskatoon, Sask. The clinicians suspected Ebola, but weren’t sure and late that night called the Saskatoon regional health department for a consultation.

Dr. Joseph Blondeau, interim head of pathology and laboratory medicine for the Saskatoon Health Region and the Royal University Hospital, took the call and set a process in motion that had been established for just such a moment, but later proved to have a variety of shortcomings, said Dr. Blondeau during a presentation at the Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

Initially, the ICU clinicians treated the man empirically with a third-generation cephalosporin and vancomycin. There were still not enough details to make a definitive diagnosis, but by early the next morning there was a high level of suspicion. The patient was hemorrhaging from his eye, there was blood in his nasogastric tube, some rectal bleeding, and a diffuse and nonspecific rash.

Dr. Blondeau ordered all specimens from the man to be quarantined, and he activated the emergency response system for Canada. At that time, there were 27 cases in Liberia, with a 40% mortality rate.

Alarmingly, one of the patient’s cerebrospinal fluid specimens had leaked in transit from St. Paul’s Hospital to a biocontainment lab at the Royal University hospital. A technician at the lab attempted to clean the container and was potentially exposed.

Both St. Paul and Royal University hospitals decided they needed a communication strategy to help allay fear and anxiety among the staff. Many were questioning why the patient was not elevated to a high infection threat when admitted to the ICU, and why higher-level precautions had not been put into place earlier.

On his way to an emergency meeting at St. Paul’s to discuss these issues, Dr. Blondeau received a call from the director of one of Canada’s biosafety level 4 labs, the National Microbiology Lab in Winnipeg, Man., who said that it was likely the patient had Ebola.

“At that point in time all hell broke loose,” said Dr. Blondeau.

The patient’s specimens needed to be immediately transported for confirmation to that national lab, a 9-hour drive from Saskatoon. The regular couriers weren’t interested. Dr. Blondeau volunteered, initially thinking he would drive them.

The specimens were prepared and packaged for containment, but the government made the decision to transport them by jet instead.

Even so, Dr. Blondeau had to drive the specimens to the air ambulance that was waiting at the Saskatoon airport. He wondered whether that was the right decision. There were questions as to whether law enforcement should be informed of the transport – what if he had an accident? He put a sign in the windshield stating that he was transporting a potential Ebola specimen as a means of making it look official, and so that no one would mistake him for a terrorist. No one had worked out whether he should accompany the specimens to Winnipeg to maintain a chain of control. He did not go.

Simultaneously, the health authorities began trying to track down all of the patient’s contacts, from arrival in the country, through an urgent clinic visit, a busy emergency room, and staff and family visits after ICU admission.

Meanwhile, the patient was deteriorating and was already ventilated and required cardiovascular support. Dr. Blondeau began discussions to bring a more sophisticated mobile lab to Saskatoon so that the patient could be repeatedly tested on-site.

“I can say with certainty that there were not many people in the province of Saskatchewan who fully understood what was about to happen should this patient have tested positive for Ebola,” said Dr. Blondeau. “We were learning as we went.”

The plans were changing by the moment, he said.

And, he said, he still had many concerns about how the situation would be perceived by those inside and outside the hospital. There was a potential for public panic and for a breach of the patient’s and family’s privacy.

Among the staff, “there was tremendous fear and panic,” Dr. Blondeau said. The spouse of the lab technician who had a potential exposure wanted her to quit her job. Another technician was spreading incorrect information, he said.

While staff worried about their own exposure and whether they had exposed their families, the patient was still critically ill and needed care and acute testing.

Then, just 24 hours after the patient had been admitted, it was determined that he did not have Ebola or any other viral hemorrhagic fever.

But “we still didn’t have a diagnosis,” said Dr. Blondeau.

He ordered routine microbiology testing on all the specimens. A day later, it looked like the culprit was Staphylococcus aureus. Further testing confirmed that it was indeed S. aureus and that it was a methicillin-susceptible strain.

Officials and staff went back to routine care processes.

In retrospect, there was much to be concerned about, said Dr. Blondeau. Use of personal protective equipment was inconsistent, which could have led to exposures. There was uncertainty about how to keep the environment clean, including linens and uniforms. For instance, he noted, many health care staff wear uniforms to work or wear them home. “Is this a practice we should be endorsing?” he asked.

There were potential problems with the physical space; for instance, some patient room doors did not close tightly.

On the plus side, no staff refused to care for the patient or to do what was asked, said Dr. Blondeau.

The entire 96-hour experience “was exciting but it was terrifying,” he said.

The lack of preparedness and the lack of a more tightly-knit lab system in the U.S. and Canada are warning signs, he said.

“The reality is we’re only the next landing flight away from a potential infectious disease threat,” said Dr. Blondeau.

On Aug. 1, Saskatoon health authorities received an alert that a passenger on an inbound flight from Senegal had many of the symptoms of a viral hemorrhagic fever: vomiting, diarrhea, and headache. They put their response system in place, and “were much better prepared the second time around,” he said, adding, “but we aren’t where we need to be.”

Dr. Blondeau reported having no conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @aliciaault

AT ICAAC 2014

VIDEO: Resistant infection risk grows by 1% for each day of hospitalization

WASHINGTON – Length of stay seemed to have the greatest impact on contracting multidrug-resistant strains of gram-negative organisms, with risk maximizing at 10 days of hospitalization. Each day of hospitalization increased the likelihood of contracting an infection with a gram-negative, multidrug-resistant organism by 1%, with risk maximizing at 10 days of hospitalization, said John A. Bosso, Pharm.D.

Researchers led by Dr. Bosso, a professor in the College of Pharmacy at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, analyzed 949 incidents of documented gram-negative infection during 1998-2014. The study is the first to quantify the potential risk of contracting a multidrug-resistant infection based on length of stay.

We caught up with Dr. Bosso, who presented his findings at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2014, and asked how health care providers and clinicians can mitigate the risks to patient health. Dr. Bosso said clinicians should be sure to identify which patients are most likely to contract a serious infection, advise patients on the risks associated with long hospital stays, and encourage patients to do their part in getting out of the hospital as quickly as possible.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

WASHINGTON – Length of stay seemed to have the greatest impact on contracting multidrug-resistant strains of gram-negative organisms, with risk maximizing at 10 days of hospitalization. Each day of hospitalization increased the likelihood of contracting an infection with a gram-negative, multidrug-resistant organism by 1%, with risk maximizing at 10 days of hospitalization, said John A. Bosso, Pharm.D.

Researchers led by Dr. Bosso, a professor in the College of Pharmacy at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, analyzed 949 incidents of documented gram-negative infection during 1998-2014. The study is the first to quantify the potential risk of contracting a multidrug-resistant infection based on length of stay.

We caught up with Dr. Bosso, who presented his findings at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2014, and asked how health care providers and clinicians can mitigate the risks to patient health. Dr. Bosso said clinicians should be sure to identify which patients are most likely to contract a serious infection, advise patients on the risks associated with long hospital stays, and encourage patients to do their part in getting out of the hospital as quickly as possible.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

WASHINGTON – Length of stay seemed to have the greatest impact on contracting multidrug-resistant strains of gram-negative organisms, with risk maximizing at 10 days of hospitalization. Each day of hospitalization increased the likelihood of contracting an infection with a gram-negative, multidrug-resistant organism by 1%, with risk maximizing at 10 days of hospitalization, said John A. Bosso, Pharm.D.

Researchers led by Dr. Bosso, a professor in the College of Pharmacy at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, analyzed 949 incidents of documented gram-negative infection during 1998-2014. The study is the first to quantify the potential risk of contracting a multidrug-resistant infection based on length of stay.

We caught up with Dr. Bosso, who presented his findings at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2014, and asked how health care providers and clinicians can mitigate the risks to patient health. Dr. Bosso said clinicians should be sure to identify which patients are most likely to contract a serious infection, advise patients on the risks associated with long hospital stays, and encourage patients to do their part in getting out of the hospital as quickly as possible.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT ICAAC 2014

VIDEO: Single-dose peramivir may simplify flu treatment

WASHINGTON – Peramivir, an investigational single-dose antiviral drug to treat influenza, could deliver multiple benefits for physicians and patients alike, Dr. Richard J. Whitley predicted.

At the 2014 Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy meeting in Washington, Dr. Whitley co-presented an analysis of phase II and phase III clinical trials that show the safety and efficacy of peramivir, which is currently under review by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Dr. Whitley is distinguished professor of pediatrics and microbiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

In a video interview, Dr. Whitley discusses what this new flu drug could mean for physicians and patients, when the drug might be approved by the FDA, and why a new flu pandemic could be coming sooner rather than later.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

WASHINGTON – Peramivir, an investigational single-dose antiviral drug to treat influenza, could deliver multiple benefits for physicians and patients alike, Dr. Richard J. Whitley predicted.

At the 2014 Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy meeting in Washington, Dr. Whitley co-presented an analysis of phase II and phase III clinical trials that show the safety and efficacy of peramivir, which is currently under review by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Dr. Whitley is distinguished professor of pediatrics and microbiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

In a video interview, Dr. Whitley discusses what this new flu drug could mean for physicians and patients, when the drug might be approved by the FDA, and why a new flu pandemic could be coming sooner rather than later.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

WASHINGTON – Peramivir, an investigational single-dose antiviral drug to treat influenza, could deliver multiple benefits for physicians and patients alike, Dr. Richard J. Whitley predicted.

At the 2014 Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy meeting in Washington, Dr. Whitley co-presented an analysis of phase II and phase III clinical trials that show the safety and efficacy of peramivir, which is currently under review by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Dr. Whitley is distinguished professor of pediatrics and microbiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

In a video interview, Dr. Whitley discusses what this new flu drug could mean for physicians and patients, when the drug might be approved by the FDA, and why a new flu pandemic could be coming sooner rather than later.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT ICAAC 2014

Maternal Tdap resulted in higher maternal cord sera IgG-PT levels

WASHINGTON – Immunizing expectant mothers with the Tdap vaccine booster shot resulted in higher cord serum levels of pertussis toxin antibodies, according to a study from Argentina.

"The results of this study [indicate] that children would be protected from pertussis until they receive the usual immunization schedule," study coauthor Dr. Aurelia Fallo, a researcher at the Hospital de Niños Dr. Ricardo Gutiérrez, Buenos Aires, said in an interview.

The Tdap vaccine for pregnant women was introduced in Argentina in 2012 to help decrease infant morbidity and mortality, according to Dr. Eduardo Lopez, director of pediatric infectious diseases at the hospital, who presented the data during the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

This was the first Latin American study to measure the effect of maternal vaccination with Tdap, he said. Argentina’s recommended schedule for maternal Tdap vaccination is during the third trimester before gestational week 38. Since 2011, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also has recommended that pregnant women receive the Tdap vaccine, after 20 weeks’ gestation.

At a single site in Buenos Aires, Dr. Fallo, Dr. Lopez, and their colleagues took serum samples and maternal cord serum samples at delivery from 88 mothers immunized with the Tdap vaccine. The investigators also took serum samples and maternal cord serum samples at delivery from 108 pairs of non–Tdap-immunized mothers. Serum samples were drawn from 69 nonpregnant women controls as well.

While all of the study participants, including controls, had received their full Tdap vaccination schedules as children, it wasn’t until 2011 that Argentina added the Tdap booster at 11 years of age to the national immunization schedule; therefore, except for the mothers who had received the maternal booster shot, no one in the study had been immunized against pertussis since the age of 6 years, Dr. Fallo said.

In the United States, the Tdap booster is recommended at age 11 years, with Td booster shots to follow every 10 years.

The mean age for all mothers was 26 years. Mothers who received their Tdap booster did so on average at gestational week 25 (standard deviation, 6 weeks).

Each mother/cord sample pair was blinded and measured for IgG-PT (pertussis toxin) antibodies using a validated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test. A measurement of 5 EU/mL was considered protective.

The mean concentration of IgG-PT in maternal cord sera taken from vaccinated mothers was 57.2 EU/mL, versus 12.3 EU/mL in unvaccinated mothers (P less than .001).

The mean concentration of IgG-PT in the vaccinated serum samples taken at delivery was 41.1 EU/mL. For the nonimmunized group, the mean IgG-PT concentration was 10.7 EU/mL (P less than .0001).

In the nonimmunized group, 19% had IgG-PT serum levels of less than 5 EU/mL, compared with 2.3% of the mothers who had been immunized (P = .001). Less than 5 EU/mL of IgG-PT was found in 3% of controls (P = .004).

The placenta antibody ratio in immunized mothers was 1.39, versus 1.1 for nonimmunized mothers (P = .01).

According to Dr. Lopez, there was a significant difference for mothers vaccinated before the third trimester, when the mean concentration of IgG-PT was 25.8 EU/mL, compared with the mean 41.9 EU/mL of IgG-PT for mothers in the third trimester (P = .002).

In all, Dr. Lopez said these data indicated that the maternal Tdap vaccination program in Argentina had greatly reduced infant mortality there. "When you compare the mortality rates from 2011 to 2013 in Argentina, there is an 87% reduction," he said. The number of pertussis-related infant deaths went from 76 in 2011 to 10 in 2013, according to official Argentina Ministry of Health records.

"The key point is that maternal Tdap immunization after 20 weeks of gestation seems to be a good strategy to protect infants," Dr. Fallo said.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

WASHINGTON – Immunizing expectant mothers with the Tdap vaccine booster shot resulted in higher cord serum levels of pertussis toxin antibodies, according to a study from Argentina.

"The results of this study [indicate] that children would be protected from pertussis until they receive the usual immunization schedule," study coauthor Dr. Aurelia Fallo, a researcher at the Hospital de Niños Dr. Ricardo Gutiérrez, Buenos Aires, said in an interview.

The Tdap vaccine for pregnant women was introduced in Argentina in 2012 to help decrease infant morbidity and mortality, according to Dr. Eduardo Lopez, director of pediatric infectious diseases at the hospital, who presented the data during the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

This was the first Latin American study to measure the effect of maternal vaccination with Tdap, he said. Argentina’s recommended schedule for maternal Tdap vaccination is during the third trimester before gestational week 38. Since 2011, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also has recommended that pregnant women receive the Tdap vaccine, after 20 weeks’ gestation.

At a single site in Buenos Aires, Dr. Fallo, Dr. Lopez, and their colleagues took serum samples and maternal cord serum samples at delivery from 88 mothers immunized with the Tdap vaccine. The investigators also took serum samples and maternal cord serum samples at delivery from 108 pairs of non–Tdap-immunized mothers. Serum samples were drawn from 69 nonpregnant women controls as well.

While all of the study participants, including controls, had received their full Tdap vaccination schedules as children, it wasn’t until 2011 that Argentina added the Tdap booster at 11 years of age to the national immunization schedule; therefore, except for the mothers who had received the maternal booster shot, no one in the study had been immunized against pertussis since the age of 6 years, Dr. Fallo said.

In the United States, the Tdap booster is recommended at age 11 years, with Td booster shots to follow every 10 years.

The mean age for all mothers was 26 years. Mothers who received their Tdap booster did so on average at gestational week 25 (standard deviation, 6 weeks).

Each mother/cord sample pair was blinded and measured for IgG-PT (pertussis toxin) antibodies using a validated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test. A measurement of 5 EU/mL was considered protective.

The mean concentration of IgG-PT in maternal cord sera taken from vaccinated mothers was 57.2 EU/mL, versus 12.3 EU/mL in unvaccinated mothers (P less than .001).

The mean concentration of IgG-PT in the vaccinated serum samples taken at delivery was 41.1 EU/mL. For the nonimmunized group, the mean IgG-PT concentration was 10.7 EU/mL (P less than .0001).

In the nonimmunized group, 19% had IgG-PT serum levels of less than 5 EU/mL, compared with 2.3% of the mothers who had been immunized (P = .001). Less than 5 EU/mL of IgG-PT was found in 3% of controls (P = .004).

The placenta antibody ratio in immunized mothers was 1.39, versus 1.1 for nonimmunized mothers (P = .01).

According to Dr. Lopez, there was a significant difference for mothers vaccinated before the third trimester, when the mean concentration of IgG-PT was 25.8 EU/mL, compared with the mean 41.9 EU/mL of IgG-PT for mothers in the third trimester (P = .002).

In all, Dr. Lopez said these data indicated that the maternal Tdap vaccination program in Argentina had greatly reduced infant mortality there. "When you compare the mortality rates from 2011 to 2013 in Argentina, there is an 87% reduction," he said. The number of pertussis-related infant deaths went from 76 in 2011 to 10 in 2013, according to official Argentina Ministry of Health records.

"The key point is that maternal Tdap immunization after 20 weeks of gestation seems to be a good strategy to protect infants," Dr. Fallo said.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

WASHINGTON – Immunizing expectant mothers with the Tdap vaccine booster shot resulted in higher cord serum levels of pertussis toxin antibodies, according to a study from Argentina.

"The results of this study [indicate] that children would be protected from pertussis until they receive the usual immunization schedule," study coauthor Dr. Aurelia Fallo, a researcher at the Hospital de Niños Dr. Ricardo Gutiérrez, Buenos Aires, said in an interview.

The Tdap vaccine for pregnant women was introduced in Argentina in 2012 to help decrease infant morbidity and mortality, according to Dr. Eduardo Lopez, director of pediatric infectious diseases at the hospital, who presented the data during the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

This was the first Latin American study to measure the effect of maternal vaccination with Tdap, he said. Argentina’s recommended schedule for maternal Tdap vaccination is during the third trimester before gestational week 38. Since 2011, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also has recommended that pregnant women receive the Tdap vaccine, after 20 weeks’ gestation.

At a single site in Buenos Aires, Dr. Fallo, Dr. Lopez, and their colleagues took serum samples and maternal cord serum samples at delivery from 88 mothers immunized with the Tdap vaccine. The investigators also took serum samples and maternal cord serum samples at delivery from 108 pairs of non–Tdap-immunized mothers. Serum samples were drawn from 69 nonpregnant women controls as well.

While all of the study participants, including controls, had received their full Tdap vaccination schedules as children, it wasn’t until 2011 that Argentina added the Tdap booster at 11 years of age to the national immunization schedule; therefore, except for the mothers who had received the maternal booster shot, no one in the study had been immunized against pertussis since the age of 6 years, Dr. Fallo said.

In the United States, the Tdap booster is recommended at age 11 years, with Td booster shots to follow every 10 years.

The mean age for all mothers was 26 years. Mothers who received their Tdap booster did so on average at gestational week 25 (standard deviation, 6 weeks).

Each mother/cord sample pair was blinded and measured for IgG-PT (pertussis toxin) antibodies using a validated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test. A measurement of 5 EU/mL was considered protective.

The mean concentration of IgG-PT in maternal cord sera taken from vaccinated mothers was 57.2 EU/mL, versus 12.3 EU/mL in unvaccinated mothers (P less than .001).

The mean concentration of IgG-PT in the vaccinated serum samples taken at delivery was 41.1 EU/mL. For the nonimmunized group, the mean IgG-PT concentration was 10.7 EU/mL (P less than .0001).

In the nonimmunized group, 19% had IgG-PT serum levels of less than 5 EU/mL, compared with 2.3% of the mothers who had been immunized (P = .001). Less than 5 EU/mL of IgG-PT was found in 3% of controls (P = .004).

The placenta antibody ratio in immunized mothers was 1.39, versus 1.1 for nonimmunized mothers (P = .01).

According to Dr. Lopez, there was a significant difference for mothers vaccinated before the third trimester, when the mean concentration of IgG-PT was 25.8 EU/mL, compared with the mean 41.9 EU/mL of IgG-PT for mothers in the third trimester (P = .002).

In all, Dr. Lopez said these data indicated that the maternal Tdap vaccination program in Argentina had greatly reduced infant mortality there. "When you compare the mortality rates from 2011 to 2013 in Argentina, there is an 87% reduction," he said. The number of pertussis-related infant deaths went from 76 in 2011 to 10 in 2013, according to official Argentina Ministry of Health records.

"The key point is that maternal Tdap immunization after 20 weeks of gestation seems to be a good strategy to protect infants," Dr. Fallo said.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT ICAAC 2014

Key clinical point: Maternal vaccination with Tdap could help prevent infant pertussis.

Major finding: Mean maternal cord sera levels of IgG-PT in mothers vaccinated with Tdap was 57.2 EU/mL, versus 12.3 EU/mL in unvaccinated mothers (P less than .001).

Data source: Single-site study in Argentina of maternal cord sera from 88 immunized mothers and 108 mothers who were not immunized.

Disclosures: Dr. Fallo and Dr. Lopez said they had no relevant disclosures.

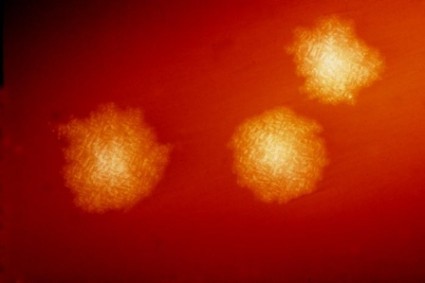

Microbiome-based Pill Holds Promise for Chronic C difficile

WASHINGTON – A rationally designed microbiome-based pill successfully eradicated recurrent Clostridium difficile infection in 29 of 30 patients in an early study presented at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

Preliminary data were presented at the 2014 James W. Freston Conference sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association in August.

The patients in the phase I/II study were divided into two separate 15-patient cohorts and were given two different dose levels of the therapy, SER-109. The drug contains spores from gram-positive bacteria that are taken from stool and then purified to kill the vegetative bacteria, said David Cook, Ph.D., executive vice president and chief scientific officer of Cambridge, Mass.–based Seres Health.

The therapy appears to work by restoring the gut flora to a normal balance after having been disrupted by antibiotic treatment.

It is not the first attempt to encapsulate a fecal transplant; Dr. Thomas Louie of the University of Calgary (Alberta), presented data on his very effective formulation against C. difficile at the ID Week annual meeting in 2013.

In the current study, the first cohort received a mean dose of 1.5 × 109 spores and the second cohort received a dose of 1 × 108 spores. In the early studies, the number of pills given to achieve that dose varied. The aim is to contain the dose in a few tablets for a commercial product, Dr. Cook said.

All doses were given on 1 or 2 days at the study’s start; there was no need for additional doses.

Patients were as young as 22 years old and as old as 88 years, and all had three or more laboratory-confirmed C. difficile infections over the previous year. They had to have a life expectancy of 3 months or longer and be able to give informed consent. They were excluded if they had any immunosuppression, a history of irritable bowel disease, total colectomy, cirrhosis, a need for antibiotics within 6 weeks of baseline, prior fecal transplant, or if they were in intensive care. There were 10 women and five men in each cohort.

After patients stopped taking antibiotics, there was a washout period after which they took SER-109. Stool was collected on day four and at 1, 2, 4, 8, and 24 weeks. Efficacy was assessed at the 8-week time point.

In the first group, 13 of the 15 patients achieved the protocol-defined endpoint: absence of C. difficile over the 8 weeks.

The two patients who failed had self-limited, transient diarrhea with a positive C. difficile test, but neither required antibiotics and both recovered within 24 hours, so they were considered to not have recurrent C. difficile, said Dr. Cook. In the second cohort, 14 of the 15 patients were free of C. difficile at 8 weeks. The patient who failed had diarrhea and a positive C. difficile test, and the diarrhea did not resolve on its own. She required antibiotics to achieve remission.

There were no serious adverse events in the study.

The company hopes to eventually conduct a phase III study and seek Food and Drug Administration approval, but it is too early to say when that might occur, said Dr. Cook.

WASHINGTON – A rationally designed microbiome-based pill successfully eradicated recurrent Clostridium difficile infection in 29 of 30 patients in an early study presented at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

Preliminary data were presented at the 2014 James W. Freston Conference sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association in August.

The patients in the phase I/II study were divided into two separate 15-patient cohorts and were given two different dose levels of the therapy, SER-109. The drug contains spores from gram-positive bacteria that are taken from stool and then purified to kill the vegetative bacteria, said David Cook, Ph.D., executive vice president and chief scientific officer of Cambridge, Mass.–based Seres Health.

The therapy appears to work by restoring the gut flora to a normal balance after having been disrupted by antibiotic treatment.

It is not the first attempt to encapsulate a fecal transplant; Dr. Thomas Louie of the University of Calgary (Alberta), presented data on his very effective formulation against C. difficile at the ID Week annual meeting in 2013.

In the current study, the first cohort received a mean dose of 1.5 × 109 spores and the second cohort received a dose of 1 × 108 spores. In the early studies, the number of pills given to achieve that dose varied. The aim is to contain the dose in a few tablets for a commercial product, Dr. Cook said.

All doses were given on 1 or 2 days at the study’s start; there was no need for additional doses.

Patients were as young as 22 years old and as old as 88 years, and all had three or more laboratory-confirmed C. difficile infections over the previous year. They had to have a life expectancy of 3 months or longer and be able to give informed consent. They were excluded if they had any immunosuppression, a history of irritable bowel disease, total colectomy, cirrhosis, a need for antibiotics within 6 weeks of baseline, prior fecal transplant, or if they were in intensive care. There were 10 women and five men in each cohort.

After patients stopped taking antibiotics, there was a washout period after which they took SER-109. Stool was collected on day four and at 1, 2, 4, 8, and 24 weeks. Efficacy was assessed at the 8-week time point.

In the first group, 13 of the 15 patients achieved the protocol-defined endpoint: absence of C. difficile over the 8 weeks.

The two patients who failed had self-limited, transient diarrhea with a positive C. difficile test, but neither required antibiotics and both recovered within 24 hours, so they were considered to not have recurrent C. difficile, said Dr. Cook. In the second cohort, 14 of the 15 patients were free of C. difficile at 8 weeks. The patient who failed had diarrhea and a positive C. difficile test, and the diarrhea did not resolve on its own. She required antibiotics to achieve remission.

There were no serious adverse events in the study.

The company hopes to eventually conduct a phase III study and seek Food and Drug Administration approval, but it is too early to say when that might occur, said Dr. Cook.

WASHINGTON – A rationally designed microbiome-based pill successfully eradicated recurrent Clostridium difficile infection in 29 of 30 patients in an early study presented at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

Preliminary data were presented at the 2014 James W. Freston Conference sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association in August.

The patients in the phase I/II study were divided into two separate 15-patient cohorts and were given two different dose levels of the therapy, SER-109. The drug contains spores from gram-positive bacteria that are taken from stool and then purified to kill the vegetative bacteria, said David Cook, Ph.D., executive vice president and chief scientific officer of Cambridge, Mass.–based Seres Health.

The therapy appears to work by restoring the gut flora to a normal balance after having been disrupted by antibiotic treatment.

It is not the first attempt to encapsulate a fecal transplant; Dr. Thomas Louie of the University of Calgary (Alberta), presented data on his very effective formulation against C. difficile at the ID Week annual meeting in 2013.

In the current study, the first cohort received a mean dose of 1.5 × 109 spores and the second cohort received a dose of 1 × 108 spores. In the early studies, the number of pills given to achieve that dose varied. The aim is to contain the dose in a few tablets for a commercial product, Dr. Cook said.

All doses were given on 1 or 2 days at the study’s start; there was no need for additional doses.

Patients were as young as 22 years old and as old as 88 years, and all had three or more laboratory-confirmed C. difficile infections over the previous year. They had to have a life expectancy of 3 months or longer and be able to give informed consent. They were excluded if they had any immunosuppression, a history of irritable bowel disease, total colectomy, cirrhosis, a need for antibiotics within 6 weeks of baseline, prior fecal transplant, or if they were in intensive care. There were 10 women and five men in each cohort.

After patients stopped taking antibiotics, there was a washout period after which they took SER-109. Stool was collected on day four and at 1, 2, 4, 8, and 24 weeks. Efficacy was assessed at the 8-week time point.

In the first group, 13 of the 15 patients achieved the protocol-defined endpoint: absence of C. difficile over the 8 weeks.

The two patients who failed had self-limited, transient diarrhea with a positive C. difficile test, but neither required antibiotics and both recovered within 24 hours, so they were considered to not have recurrent C. difficile, said Dr. Cook. In the second cohort, 14 of the 15 patients were free of C. difficile at 8 weeks. The patient who failed had diarrhea and a positive C. difficile test, and the diarrhea did not resolve on its own. She required antibiotics to achieve remission.

There were no serious adverse events in the study.

The company hopes to eventually conduct a phase III study and seek Food and Drug Administration approval, but it is too early to say when that might occur, said Dr. Cook.

AT ICAAC 2014

Microbiome-based pill holds promise for chronic C. difficile

WASHINGTON – A rationally designed microbiome-based pill successfully eradicated recurrent Clostridium difficile infection in 29 of 30 patients in an early study presented at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

Preliminary data were presented at the 2014 James W. Freston Conference sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association in August.

The patients in the phase I/II study were divided into two separate 15-patient cohorts and were given two different dose levels of the therapy, SER-109. The drug contains spores from gram-positive bacteria that are taken from stool and then purified to kill the vegetative bacteria, said David Cook, Ph.D., executive vice president and chief scientific officer of Cambridge, Mass.–based Seres Health.

The therapy appears to work by restoring the gut flora to a normal balance after having been disrupted by antibiotic treatment.

It is not the first attempt to encapsulate a fecal transplant; Dr. Thomas Louie of the University of Calgary (Alberta), presented data on his very effective formulation against C. difficile at the ID Week annual meeting in 2013.

In the current study, the first cohort received a mean dose of 1.5 × 109 spores and the second cohort received a dose of 1 × 108 spores. In the early studies, the number of pills given to achieve that dose varied. The aim is to contain the dose in a few tablets for a commercial product, Dr. Cook said.

All doses were given on 1 or 2 days at the study’s start; there was no need for additional doses.

Patients were as young as 22 years old and as old as 88 years, and all had three or more laboratory-confirmed C. difficile infections over the previous year. They had to have a life expectancy of 3 months or longer and be able to give informed consent. They were excluded if they had any immunosuppression, a history of irritable bowel disease, total colectomy, cirrhosis, a need for antibiotics within 6 weeks of baseline, prior fecal transplant, or if they were in intensive care. There were 10 women and five men in each cohort.

After patients stopped taking antibiotics, there was a washout period after which they took SER-109. Stool was collected on day four and at 1, 2, 4, 8, and 24 weeks. Efficacy was assessed at the 8-week time point.

In the first group, 13 of the 15 patients achieved the protocol-defined endpoint: absence of C. difficile over the 8 weeks.

The two patients who failed had self-limited, transient diarrhea with a positive C. difficile test, but neither required antibiotics and both recovered within 24 hours, so they were considered to not have recurrent C. difficile, said Dr. Cook. In the second cohort, 14 of the 15 patients were free of C. difficile at 8 weeks. The patient who failed had diarrhea and a positive C. difficile test, and the diarrhea did not resolve on its own. She required antibiotics to achieve remission.

There were no serious adverse events in the study.

The company hopes to eventually conduct a phase III study and seek Food and Drug Administration approval, but it is too early to say when that might occur, said Dr. Cook.

On Twitter @aliciaault

This story was updated on October 14.

The AGA hosted the annual James W. Freston conference in Chicago this August, and this year's topic was therapeutic innovations in microbiome research and technology, with a focus on fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). There were more than 140 participants from 16 countries present to discuss evolving research and clinical approaches to FMT.

The 2-day meeting opened with lectures highlighting evolving knowledge about the human microbiome, and how quickly its composition can change with environmental exposures such as travel or diet. These were followed by additional presentations about FMT as a treatment for Clostridium difficile and inflammatory bowel disease, and intriguing work on the role of the gut microbiome in the metabolic syndrome. There were many productive discussions among the FMT enthusiasts, some of which are summarized in this issue of GI & Hepatology News. The final session of the meeting featured presentations about institutional review board regulation of trials involving FMT, and updates from the Food and Drug Administration.

It is clear that FMT is an effective treatment for recurrent C. diff., and may even be positioned as an earlier treatment option for some patients. The short-term safety of FMT in existing trials is reassuring, but there was general consensus at the meeting that we need further study of long-term outcomes of recipients. In the United States, the FDA has relaxed its stance on FMT for recurrent C. diff., but an investigational new drug application must be filed with the FDA for its use for any other purposes. Studies of FMT for inflammatory bowel diseases, irritable bowel syndrome, and other conditions are quite limited at this time, and it is clear that additional research is needed before we will understand the associations and potential causality related to the microbiome. In addition, there is a desperate need for further understanding of the complex ecology of the gut microbiome as well as what additional viruses, phages, and proteins may be transferred from a donor to recipient.

Patients have eagerly embraced FMT as a potential treatment for a variety of illnesses, but the evidence for safety and efficacy for any conditions beyond C. diff. is lacking. Therefore, many attendees at the conference emphasized the need for better education about the potential risks and the need for more study.

The Freston conference was a great success, and highlighted some of the important progress that has been made in understanding the human microbiome and its therapeutic potential, but also underscored the near-term research priorities and safety concerns.

Dr. David T. Rubin is Joseph B. Kirsner Professor of Medicine, section chief of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition, and codirector of the Digestive Diseases Center, University of Chicago. He was co-course director of the Freston conference with Dr. Stacy Kahn.

The AGA hosted the annual James W. Freston conference in Chicago this August, and this year's topic was therapeutic innovations in microbiome research and technology, with a focus on fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). There were more than 140 participants from 16 countries present to discuss evolving research and clinical approaches to FMT.

The 2-day meeting opened with lectures highlighting evolving knowledge about the human microbiome, and how quickly its composition can change with environmental exposures such as travel or diet. These were followed by additional presentations about FMT as a treatment for Clostridium difficile and inflammatory bowel disease, and intriguing work on the role of the gut microbiome in the metabolic syndrome. There were many productive discussions among the FMT enthusiasts, some of which are summarized in this issue of GI & Hepatology News. The final session of the meeting featured presentations about institutional review board regulation of trials involving FMT, and updates from the Food and Drug Administration.

It is clear that FMT is an effective treatment for recurrent C. diff., and may even be positioned as an earlier treatment option for some patients. The short-term safety of FMT in existing trials is reassuring, but there was general consensus at the meeting that we need further study of long-term outcomes of recipients. In the United States, the FDA has relaxed its stance on FMT for recurrent C. diff., but an investigational new drug application must be filed with the FDA for its use for any other purposes. Studies of FMT for inflammatory bowel diseases, irritable bowel syndrome, and other conditions are quite limited at this time, and it is clear that additional research is needed before we will understand the associations and potential causality related to the microbiome. In addition, there is a desperate need for further understanding of the complex ecology of the gut microbiome as well as what additional viruses, phages, and proteins may be transferred from a donor to recipient.

Patients have eagerly embraced FMT as a potential treatment for a variety of illnesses, but the evidence for safety and efficacy for any conditions beyond C. diff. is lacking. Therefore, many attendees at the conference emphasized the need for better education about the potential risks and the need for more study.

The Freston conference was a great success, and highlighted some of the important progress that has been made in understanding the human microbiome and its therapeutic potential, but also underscored the near-term research priorities and safety concerns.

Dr. David T. Rubin is Joseph B. Kirsner Professor of Medicine, section chief of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition, and codirector of the Digestive Diseases Center, University of Chicago. He was co-course director of the Freston conference with Dr. Stacy Kahn.

The AGA hosted the annual James W. Freston conference in Chicago this August, and this year's topic was therapeutic innovations in microbiome research and technology, with a focus on fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). There were more than 140 participants from 16 countries present to discuss evolving research and clinical approaches to FMT.

The 2-day meeting opened with lectures highlighting evolving knowledge about the human microbiome, and how quickly its composition can change with environmental exposures such as travel or diet. These were followed by additional presentations about FMT as a treatment for Clostridium difficile and inflammatory bowel disease, and intriguing work on the role of the gut microbiome in the metabolic syndrome. There were many productive discussions among the FMT enthusiasts, some of which are summarized in this issue of GI & Hepatology News. The final session of the meeting featured presentations about institutional review board regulation of trials involving FMT, and updates from the Food and Drug Administration.

It is clear that FMT is an effective treatment for recurrent C. diff., and may even be positioned as an earlier treatment option for some patients. The short-term safety of FMT in existing trials is reassuring, but there was general consensus at the meeting that we need further study of long-term outcomes of recipients. In the United States, the FDA has relaxed its stance on FMT for recurrent C. diff., but an investigational new drug application must be filed with the FDA for its use for any other purposes. Studies of FMT for inflammatory bowel diseases, irritable bowel syndrome, and other conditions are quite limited at this time, and it is clear that additional research is needed before we will understand the associations and potential causality related to the microbiome. In addition, there is a desperate need for further understanding of the complex ecology of the gut microbiome as well as what additional viruses, phages, and proteins may be transferred from a donor to recipient.

Patients have eagerly embraced FMT as a potential treatment for a variety of illnesses, but the evidence for safety and efficacy for any conditions beyond C. diff. is lacking. Therefore, many attendees at the conference emphasized the need for better education about the potential risks and the need for more study.

The Freston conference was a great success, and highlighted some of the important progress that has been made in understanding the human microbiome and its therapeutic potential, but also underscored the near-term research priorities and safety concerns.

Dr. David T. Rubin is Joseph B. Kirsner Professor of Medicine, section chief of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition, and codirector of the Digestive Diseases Center, University of Chicago. He was co-course director of the Freston conference with Dr. Stacy Kahn.

WASHINGTON – A rationally designed microbiome-based pill successfully eradicated recurrent Clostridium difficile infection in 29 of 30 patients in an early study presented at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

Preliminary data were presented at the 2014 James W. Freston Conference sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association in August.

The patients in the phase I/II study were divided into two separate 15-patient cohorts and were given two different dose levels of the therapy, SER-109. The drug contains spores from gram-positive bacteria that are taken from stool and then purified to kill the vegetative bacteria, said David Cook, Ph.D., executive vice president and chief scientific officer of Cambridge, Mass.–based Seres Health.

The therapy appears to work by restoring the gut flora to a normal balance after having been disrupted by antibiotic treatment.

It is not the first attempt to encapsulate a fecal transplant; Dr. Thomas Louie of the University of Calgary (Alberta), presented data on his very effective formulation against C. difficile at the ID Week annual meeting in 2013.

In the current study, the first cohort received a mean dose of 1.5 × 109 spores and the second cohort received a dose of 1 × 108 spores. In the early studies, the number of pills given to achieve that dose varied. The aim is to contain the dose in a few tablets for a commercial product, Dr. Cook said.

All doses were given on 1 or 2 days at the study’s start; there was no need for additional doses.

Patients were as young as 22 years old and as old as 88 years, and all had three or more laboratory-confirmed C. difficile infections over the previous year. They had to have a life expectancy of 3 months or longer and be able to give informed consent. They were excluded if they had any immunosuppression, a history of irritable bowel disease, total colectomy, cirrhosis, a need for antibiotics within 6 weeks of baseline, prior fecal transplant, or if they were in intensive care. There were 10 women and five men in each cohort.

After patients stopped taking antibiotics, there was a washout period after which they took SER-109. Stool was collected on day four and at 1, 2, 4, 8, and 24 weeks. Efficacy was assessed at the 8-week time point.

In the first group, 13 of the 15 patients achieved the protocol-defined endpoint: absence of C. difficile over the 8 weeks.

The two patients who failed had self-limited, transient diarrhea with a positive C. difficile test, but neither required antibiotics and both recovered within 24 hours, so they were considered to not have recurrent C. difficile, said Dr. Cook. In the second cohort, 14 of the 15 patients were free of C. difficile at 8 weeks. The patient who failed had diarrhea and a positive C. difficile test, and the diarrhea did not resolve on its own. She required antibiotics to achieve remission.

There were no serious adverse events in the study.

The company hopes to eventually conduct a phase III study and seek Food and Drug Administration approval, but it is too early to say when that might occur, said Dr. Cook.

On Twitter @aliciaault

This story was updated on October 14.

WASHINGTON – A rationally designed microbiome-based pill successfully eradicated recurrent Clostridium difficile infection in 29 of 30 patients in an early study presented at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

Preliminary data were presented at the 2014 James W. Freston Conference sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association in August.

The patients in the phase I/II study were divided into two separate 15-patient cohorts and were given two different dose levels of the therapy, SER-109. The drug contains spores from gram-positive bacteria that are taken from stool and then purified to kill the vegetative bacteria, said David Cook, Ph.D., executive vice president and chief scientific officer of Cambridge, Mass.–based Seres Health.

The therapy appears to work by restoring the gut flora to a normal balance after having been disrupted by antibiotic treatment.

It is not the first attempt to encapsulate a fecal transplant; Dr. Thomas Louie of the University of Calgary (Alberta), presented data on his very effective formulation against C. difficile at the ID Week annual meeting in 2013.

In the current study, the first cohort received a mean dose of 1.5 × 109 spores and the second cohort received a dose of 1 × 108 spores. In the early studies, the number of pills given to achieve that dose varied. The aim is to contain the dose in a few tablets for a commercial product, Dr. Cook said.

All doses were given on 1 or 2 days at the study’s start; there was no need for additional doses.

Patients were as young as 22 years old and as old as 88 years, and all had three or more laboratory-confirmed C. difficile infections over the previous year. They had to have a life expectancy of 3 months or longer and be able to give informed consent. They were excluded if they had any immunosuppression, a history of irritable bowel disease, total colectomy, cirrhosis, a need for antibiotics within 6 weeks of baseline, prior fecal transplant, or if they were in intensive care. There were 10 women and five men in each cohort.

After patients stopped taking antibiotics, there was a washout period after which they took SER-109. Stool was collected on day four and at 1, 2, 4, 8, and 24 weeks. Efficacy was assessed at the 8-week time point.

In the first group, 13 of the 15 patients achieved the protocol-defined endpoint: absence of C. difficile over the 8 weeks.

The two patients who failed had self-limited, transient diarrhea with a positive C. difficile test, but neither required antibiotics and both recovered within 24 hours, so they were considered to not have recurrent C. difficile, said Dr. Cook. In the second cohort, 14 of the 15 patients were free of C. difficile at 8 weeks. The patient who failed had diarrhea and a positive C. difficile test, and the diarrhea did not resolve on its own. She required antibiotics to achieve remission.

There were no serious adverse events in the study.

The company hopes to eventually conduct a phase III study and seek Food and Drug Administration approval, but it is too early to say when that might occur, said Dr. Cook.

On Twitter @aliciaault

This story was updated on October 14.

AT ICAAC 2014

Key clinical point: A new oral medication might eventually replace fecal transplants.

Major finding: Recurrent Clostridium difficile infection was eradicated in 29 of 30 patients.

Data source: Open-label prospective study that assessed absence of C. difficile at 8 weeks post therapy.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Seres Health. Dr. Cook is a Seres employee.

Emory’s Ebola experience held logistical surprises

WASHINGTON – When two Ebola-infected patients were airlifted to Emory University Hospital in Atlanta in early August, dedicated staffers were prepared to care for the patients. But those staffers had to act quickly to deal with unanticipated challenges that came from regulators and some of the hospital’s contractors, who initially refused to dispose of the mountains of medical waste generated by the patients and the clinicians who cared for them, according to Dr. Aneesh Mehta.

Dr. Mehta, associate chief of Emory’s infectious disease service, was one of the primary attending physicians for Nancy Writebol and Dr. Kent Brantly, who recovered from their Ebola infections and were discharged from Emory’s isolation unit on Aug. 19 and Aug. 21.

The lessons learned from caring for these initial patients are now being applied to Emory’s latest Ebola-infected patient, who arrived at the facility from West Africa on Sept. 9, said Dr. Mehta, who spoke on the logistics, successes, and challenges of caring for Ebola-infected patients at Emory at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The local civil authorities asked that the Emory unit not introduce any untreated patient waste into the municipal waste stream. The staff disinfected with bleach or detergents all of the patients’ liquid wastes for more than 5 minutes before flushing them down the toilet.

And there was plenty of other potentially hazardous and infectious material that had to be addressed. At the peak of the patients’ illness, up to 40 bags a day of medical waste were being produced, said Dr. Mehta.

Initially, the hospital’s waste management contractor refused to pick up the medical waste for several days. To manage the situation temporarily, the Emory staff "went to Home Depot and bought up every large trash can and sealed canister that we could get," said Dr. Mehta. The filled cans were kept in a containment room until the hospital completed negotiations with the contractor to pick up the waste.

Even the commercial courier company that the hospital had always used to transport infectious and potentially lethal samples to the labs at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention "suddenly said ‘no,’ " Dr. Mehta said. "If the label said ‘CDC’ on it, they refused to touch it."

Even some Emory staffers who had previously handled and packed dangerous samples for shipping refused to come to the isolation unit’s lab, said Dr. Mehta. The hospital’s safety officers had to train some of the dedicated Ebola staff to pack samples appropriately for shipping.

But even as the hospital dealt with these issues and the growing media circus, the Ebola staff stayed focused, Dr. Mehta said. "It was very chaotic outside, but very calm in the hospital and with our team."

The hospital spent a lot of time on communications – with the public, with staff, and with other patients in the hospital and their families. Emory held twice-daily town halls with staff to give information and answer questions, and also sent regular e-mail updates about the Ebola patients. Every inpatient and new admission was given a letter explaining why Emory had taken the patients, and physician and administrative leaders rounded throughout the hospital to answer questions.

Emory already had a "serious communicable diseases" unit, which it created in 2002 as a place to receive any CDC workers who might be exposed to pathogens on the job. The six-room unit has a patient room on each end, with a private bathroom in each, a staff dressing area, and an anteroom that was used as a staging area for nurses.

After the decision to accept the Ebola-infected patients, a new point-of-care lab facility was built in less than 72 hours in an adjoining office space, said Dr. Mehta. Having this kind of dedicated unit was not absolutely necessary, but it allowed the staff to more conveniently perform chemistry, hematology, blood gas, urinalysis, coagulation, and malaria tests and get immediate results. Having a dedicated lab space also limited the exposure fears of staff elsewhere in the hospital.

To prevent transmission of the virus, the unit followed the CDC’s recommendations, which included keeping a detailed log of anyone who entered and exited a patient room, using disposable equipment whenever possible, and using personal protective equipment that included gloves, fluid-resistant or impermeable gowns, and goggles or face shields. Initially, the Emory caregivers had leg and foot coverings because the patients had vomited blood before arriving, and one of the patients had fulminant diarrhea, up to four liters per day, said Dr. Mehta.

Because the disease can be transmitted from protective gear, all staff had a refresher course on appropriate use of the gear, everyone was observed by another team member when putting on or taking off the gear, and reminders about appropriate use of the gear were placed on the walls of the unit and in the changing area.

The clinical care team met every day to review plans and protocols and to answer staff questions. Twice daily, all personnel had to enter into an online registry their body temperatures and any symptoms. Dr. Mehta told the ICAAC audience that he had just completed his 21-day observation period.

The patient care itself was far from clear cut, as there is no proven treatment and Emory officials initially were not clear on the availability of any experimental therapy, said Dr. Mehta. The CDC helped to monitor the patients’ viral load, and both patients had marked electrolyte imbalances, including hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, and hyponatremia, as well as severe nutritional deficiencies. Both required significant potassium replacement.

Both patients received a three-dose course of Zmapp, which consists of three monoclonal antibodies and is under development by Mapp Biopharmaceutical. While in Africa, Dr. Brantly also had received a transfusion of plasma from a patient who was recovering from the Ebola virus.

High-level, one-on-one nursing care also was noted as a significant factor in patient recovery, said Dr. Mehta.

"It’s hard to derive a lot of meaningful data from the care of those two patients," Dr. Mehta said. It’s not clear yet which of these factors – Zmapp, the transfusion, the supportive care, or the combination – was responsible for the patients’ recovery.

Emory will publish its experiences in Ebola care, but "the real front line is in West Africa," Dr. Mehta added.

On Twitter @aliciaault

WASHINGTON – When two Ebola-infected patients were airlifted to Emory University Hospital in Atlanta in early August, dedicated staffers were prepared to care for the patients. But those staffers had to act quickly to deal with unanticipated challenges that came from regulators and some of the hospital’s contractors, who initially refused to dispose of the mountains of medical waste generated by the patients and the clinicians who cared for them, according to Dr. Aneesh Mehta.

Dr. Mehta, associate chief of Emory’s infectious disease service, was one of the primary attending physicians for Nancy Writebol and Dr. Kent Brantly, who recovered from their Ebola infections and were discharged from Emory’s isolation unit on Aug. 19 and Aug. 21.

The lessons learned from caring for these initial patients are now being applied to Emory’s latest Ebola-infected patient, who arrived at the facility from West Africa on Sept. 9, said Dr. Mehta, who spoke on the logistics, successes, and challenges of caring for Ebola-infected patients at Emory at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The local civil authorities asked that the Emory unit not introduce any untreated patient waste into the municipal waste stream. The staff disinfected with bleach or detergents all of the patients’ liquid wastes for more than 5 minutes before flushing them down the toilet.

And there was plenty of other potentially hazardous and infectious material that had to be addressed. At the peak of the patients’ illness, up to 40 bags a day of medical waste were being produced, said Dr. Mehta.

Initially, the hospital’s waste management contractor refused to pick up the medical waste for several days. To manage the situation temporarily, the Emory staff "went to Home Depot and bought up every large trash can and sealed canister that we could get," said Dr. Mehta. The filled cans were kept in a containment room until the hospital completed negotiations with the contractor to pick up the waste.

Even the commercial courier company that the hospital had always used to transport infectious and potentially lethal samples to the labs at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention "suddenly said ‘no,’ " Dr. Mehta said. "If the label said ‘CDC’ on it, they refused to touch it."

Even some Emory staffers who had previously handled and packed dangerous samples for shipping refused to come to the isolation unit’s lab, said Dr. Mehta. The hospital’s safety officers had to train some of the dedicated Ebola staff to pack samples appropriately for shipping.

But even as the hospital dealt with these issues and the growing media circus, the Ebola staff stayed focused, Dr. Mehta said. "It was very chaotic outside, but very calm in the hospital and with our team."

The hospital spent a lot of time on communications – with the public, with staff, and with other patients in the hospital and their families. Emory held twice-daily town halls with staff to give information and answer questions, and also sent regular e-mail updates about the Ebola patients. Every inpatient and new admission was given a letter explaining why Emory had taken the patients, and physician and administrative leaders rounded throughout the hospital to answer questions.

Emory already had a "serious communicable diseases" unit, which it created in 2002 as a place to receive any CDC workers who might be exposed to pathogens on the job. The six-room unit has a patient room on each end, with a private bathroom in each, a staff dressing area, and an anteroom that was used as a staging area for nurses.