User login

International Society for Infectious Diseases (ISID): International Meeting on Emerging Infectious Diseases and Surveillance (IMED 2014)

Participatory surveillance gains ground in U.S., Brazil

VIENNA – Participatory surveillance has begun to enter mainstream public health.

The Brazilian Ministry of Health arranged for distribution of a participatory surveillance app for monitoring 10 symptoms in people attending or working at 2014 FIFA World Cup events. The smart phone app had 9,434 downloads, 7,155 registered users, and 4,706 active users who sent a message about their symptom status at least three times during the World Cup last June and July in Brazil, Dr. Marlo Libel said at the International Meeting on Emerging Diseases and Surveillance. “Healthy Cup 2014” became the first participatory surveillance tool ever used at a mass gathering event, he said.

“We demonstrated that direct self-reporting during a short period of time could be an excellent tool to complement other surveillance activities,” said Dr. Libel, a medical epidemiology consultant who worked with the Skoll Global Threats Fund on the Brazilian project. Officials at the Brazilian Ministry of Health were so pleased with the program that they are planning with Skoll to release similar apps for Carnival in Feb. 2015 and then for the 2016 Summer Olympics, Dr. Libel said.

Flu Near You shows U.S. growth

Longer-term participatory surveillance of U.S. residents began with the launch of the Flu Near You program in 2012, and by October 2014 it had roughly 100,000 U.S. participants, said John S. Brownstein, Ph.D., an epidemiologist at Harvard Medical School in Boston and cofounder of Flu Near You.

That level is large enough to provide meaningful information, according to Matthew Biggerstaff, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, as well as other public health officials.

“We’ve been really excited at CDC about Flu Near You because it gives us a view of influenza illness that goes beyond the medically attended cases we base our usual surveillance on,” said Matthew Biggerstaff, an epidemiologist in the CDC’s influenza division. “It adds timeliness because we usually have a 1-week lag” in reporting data from outpatient physician visits and hospitalizations. Flu Near You, which asks participants to report weekly on whether they have any of 10 symptoms gives information that goes beyond the flu-like illness tallied by standard CDC surveillance. “We do not think that it will replace our traditional health care–based surveillance, but it gives us another set of data to look at,” Mr. Biggerstaff said in an interview.

The 10 symptoms that Flu Near You prompts users to report on each week are fever, cough, sore throat, shortness of breath, chills or night sweats, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, body ache, and headache. New participants are also asked whether they received a flu shot during the prior season, Aug. 1-July 31, as well as during the current season since the most recent July 31.

Flu Near You and other participatory surveillance tools also offer epidemiologists a way to track the participating cohort over time. That allows assessment of individual attack rates of influenza-like illness and other syndromes and also vaccine efficacy, Mr. Biggerstaff noted.

“It helps give us a feel for what is happening” with influenza. “We have worked with Flu Near You in the past and we continue to think about ways to work together on digital disease surveillance. We promote it to our state and local colleagues. We think it is a good resource for states to have,” he sad. The CDC’s influenza division is also assessing and using other novel forms of surveillance data, such as influenza and flu mentions on Twitter and searches on Google as well as a statistic Google maintains as Flu Trends.

Participatory surveillance is “very exciting” but is also “new and unproven and remains an experiment,” said Dr. Lawrence C. Madoff, director of the division of epidemiology and immunization at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health in Boston. But while participatory surveillance must still prove its role, U.S. public health officials “increasingly” accept the value of data from tools like Flu Near You, Dr. Madoff said in an interview. He cited the endorsement that participatory surveillance received in recent surveillance and early-detection recommendations from the World Health Organization. The 100,000 participants in Flu Near You give it a “critical mass that will become even more robust as it continues to grow,” Dr. Madoff said.

Further growth is clearly a priority for Flu Near You. “We’re now very excited to promote Flu Near You in a big way to try to get more numbers there and see if we can have a faster system for picking up influenza,” said Dr. Mark S. Smolinski, director of global health at Skoll.

“We are still trying to think through how do we get [Flu Near You] into the general consciousness” of more Americans, said Dr. Brownstein. While participants, not all of whom are active every week, provide enough data to show good correlation with the CDC’s routine surveillance on a national scale, if Flu Near You “had enough numbers we could drill down into subpopulations,” he noted. For now, the volume of participation makes subgroups too scanty in size for meaningful analysis, Dr. Brownstein conceded.

Mass gathering surveillance in Brazil

The Brazilian surveillance program at the World Cup was modeled on Flu Near You, but Dr. Libel, Dr. Smolinski, and their collaborators produced the app in about 8 weeks after receiving very short notice of the Brazilians’ interest. The weekly, symptom surveillance questions posed by the app replicated seven symptoms from Flu Near You – fever, cough, sore throat, shortness of breath, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, and headache – and added three new symptoms to the survey: joint pain, bleeding, and red spots on body. This allowed the Health Ministry to also monitor for outbreaks of other infections including measles, cholera, dengue, and chikungunya, Dr. Libel said. The Brazilian app also asked participants each week whether they had been in contact with anyone who had any of the 10 listed symptoms, and whether they had looked for health care services. No outbreaks of any type occurred in Brazil during the World Cup, but during the period it was actively used 27% of the frequent respondents reported experiencing at least one symptom.

The first Brazilian effort “was basically a pilot program,” with little advance promotion, Dr. Smolinksi said in an interview. Officials of the Brazilian Ministry of Health were “impressed” with the data collected. They also liked the ability of the system to push out information on health care access to registered users, and the potential the app offered to send out urgent public health messages. “What the Health Ministry loved the most was that if there had been an outbreak they could have immediately reached out to fans,” Dr. Smolinski said.

The Ministry has interest in expanded surveillance and outreach programs for Carnival and the 2016 Summer Olympics, and Dr. Smolinski and his associates are hopeful that the International Olympics Committee will be receptive to the program and aid in its promotion during 2016. They are also planning to expand beyond smart phones and include the capability to interact with users via text and voice messages.

“We hope we will have huge numbers at the Olympics,” to better document the role participatory surveillance can play at mass gatherings, Dr. Smolinski said.

Dr. Libel, Dr. Brownstein, Mr. Biggerstaff, Dr. Smolinski, and Dr. Madoff had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

VIENNA – Participatory surveillance has begun to enter mainstream public health.

The Brazilian Ministry of Health arranged for distribution of a participatory surveillance app for monitoring 10 symptoms in people attending or working at 2014 FIFA World Cup events. The smart phone app had 9,434 downloads, 7,155 registered users, and 4,706 active users who sent a message about their symptom status at least three times during the World Cup last June and July in Brazil, Dr. Marlo Libel said at the International Meeting on Emerging Diseases and Surveillance. “Healthy Cup 2014” became the first participatory surveillance tool ever used at a mass gathering event, he said.

“We demonstrated that direct self-reporting during a short period of time could be an excellent tool to complement other surveillance activities,” said Dr. Libel, a medical epidemiology consultant who worked with the Skoll Global Threats Fund on the Brazilian project. Officials at the Brazilian Ministry of Health were so pleased with the program that they are planning with Skoll to release similar apps for Carnival in Feb. 2015 and then for the 2016 Summer Olympics, Dr. Libel said.

Flu Near You shows U.S. growth

Longer-term participatory surveillance of U.S. residents began with the launch of the Flu Near You program in 2012, and by October 2014 it had roughly 100,000 U.S. participants, said John S. Brownstein, Ph.D., an epidemiologist at Harvard Medical School in Boston and cofounder of Flu Near You.

That level is large enough to provide meaningful information, according to Matthew Biggerstaff, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, as well as other public health officials.

“We’ve been really excited at CDC about Flu Near You because it gives us a view of influenza illness that goes beyond the medically attended cases we base our usual surveillance on,” said Matthew Biggerstaff, an epidemiologist in the CDC’s influenza division. “It adds timeliness because we usually have a 1-week lag” in reporting data from outpatient physician visits and hospitalizations. Flu Near You, which asks participants to report weekly on whether they have any of 10 symptoms gives information that goes beyond the flu-like illness tallied by standard CDC surveillance. “We do not think that it will replace our traditional health care–based surveillance, but it gives us another set of data to look at,” Mr. Biggerstaff said in an interview.

The 10 symptoms that Flu Near You prompts users to report on each week are fever, cough, sore throat, shortness of breath, chills or night sweats, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, body ache, and headache. New participants are also asked whether they received a flu shot during the prior season, Aug. 1-July 31, as well as during the current season since the most recent July 31.

Flu Near You and other participatory surveillance tools also offer epidemiologists a way to track the participating cohort over time. That allows assessment of individual attack rates of influenza-like illness and other syndromes and also vaccine efficacy, Mr. Biggerstaff noted.

“It helps give us a feel for what is happening” with influenza. “We have worked with Flu Near You in the past and we continue to think about ways to work together on digital disease surveillance. We promote it to our state and local colleagues. We think it is a good resource for states to have,” he sad. The CDC’s influenza division is also assessing and using other novel forms of surveillance data, such as influenza and flu mentions on Twitter and searches on Google as well as a statistic Google maintains as Flu Trends.

Participatory surveillance is “very exciting” but is also “new and unproven and remains an experiment,” said Dr. Lawrence C. Madoff, director of the division of epidemiology and immunization at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health in Boston. But while participatory surveillance must still prove its role, U.S. public health officials “increasingly” accept the value of data from tools like Flu Near You, Dr. Madoff said in an interview. He cited the endorsement that participatory surveillance received in recent surveillance and early-detection recommendations from the World Health Organization. The 100,000 participants in Flu Near You give it a “critical mass that will become even more robust as it continues to grow,” Dr. Madoff said.

Further growth is clearly a priority for Flu Near You. “We’re now very excited to promote Flu Near You in a big way to try to get more numbers there and see if we can have a faster system for picking up influenza,” said Dr. Mark S. Smolinski, director of global health at Skoll.

“We are still trying to think through how do we get [Flu Near You] into the general consciousness” of more Americans, said Dr. Brownstein. While participants, not all of whom are active every week, provide enough data to show good correlation with the CDC’s routine surveillance on a national scale, if Flu Near You “had enough numbers we could drill down into subpopulations,” he noted. For now, the volume of participation makes subgroups too scanty in size for meaningful analysis, Dr. Brownstein conceded.

Mass gathering surveillance in Brazil

The Brazilian surveillance program at the World Cup was modeled on Flu Near You, but Dr. Libel, Dr. Smolinski, and their collaborators produced the app in about 8 weeks after receiving very short notice of the Brazilians’ interest. The weekly, symptom surveillance questions posed by the app replicated seven symptoms from Flu Near You – fever, cough, sore throat, shortness of breath, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, and headache – and added three new symptoms to the survey: joint pain, bleeding, and red spots on body. This allowed the Health Ministry to also monitor for outbreaks of other infections including measles, cholera, dengue, and chikungunya, Dr. Libel said. The Brazilian app also asked participants each week whether they had been in contact with anyone who had any of the 10 listed symptoms, and whether they had looked for health care services. No outbreaks of any type occurred in Brazil during the World Cup, but during the period it was actively used 27% of the frequent respondents reported experiencing at least one symptom.

The first Brazilian effort “was basically a pilot program,” with little advance promotion, Dr. Smolinksi said in an interview. Officials of the Brazilian Ministry of Health were “impressed” with the data collected. They also liked the ability of the system to push out information on health care access to registered users, and the potential the app offered to send out urgent public health messages. “What the Health Ministry loved the most was that if there had been an outbreak they could have immediately reached out to fans,” Dr. Smolinski said.

The Ministry has interest in expanded surveillance and outreach programs for Carnival and the 2016 Summer Olympics, and Dr. Smolinski and his associates are hopeful that the International Olympics Committee will be receptive to the program and aid in its promotion during 2016. They are also planning to expand beyond smart phones and include the capability to interact with users via text and voice messages.

“We hope we will have huge numbers at the Olympics,” to better document the role participatory surveillance can play at mass gatherings, Dr. Smolinski said.

Dr. Libel, Dr. Brownstein, Mr. Biggerstaff, Dr. Smolinski, and Dr. Madoff had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

VIENNA – Participatory surveillance has begun to enter mainstream public health.

The Brazilian Ministry of Health arranged for distribution of a participatory surveillance app for monitoring 10 symptoms in people attending or working at 2014 FIFA World Cup events. The smart phone app had 9,434 downloads, 7,155 registered users, and 4,706 active users who sent a message about their symptom status at least three times during the World Cup last June and July in Brazil, Dr. Marlo Libel said at the International Meeting on Emerging Diseases and Surveillance. “Healthy Cup 2014” became the first participatory surveillance tool ever used at a mass gathering event, he said.

“We demonstrated that direct self-reporting during a short period of time could be an excellent tool to complement other surveillance activities,” said Dr. Libel, a medical epidemiology consultant who worked with the Skoll Global Threats Fund on the Brazilian project. Officials at the Brazilian Ministry of Health were so pleased with the program that they are planning with Skoll to release similar apps for Carnival in Feb. 2015 and then for the 2016 Summer Olympics, Dr. Libel said.

Flu Near You shows U.S. growth

Longer-term participatory surveillance of U.S. residents began with the launch of the Flu Near You program in 2012, and by October 2014 it had roughly 100,000 U.S. participants, said John S. Brownstein, Ph.D., an epidemiologist at Harvard Medical School in Boston and cofounder of Flu Near You.

That level is large enough to provide meaningful information, according to Matthew Biggerstaff, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, as well as other public health officials.

“We’ve been really excited at CDC about Flu Near You because it gives us a view of influenza illness that goes beyond the medically attended cases we base our usual surveillance on,” said Matthew Biggerstaff, an epidemiologist in the CDC’s influenza division. “It adds timeliness because we usually have a 1-week lag” in reporting data from outpatient physician visits and hospitalizations. Flu Near You, which asks participants to report weekly on whether they have any of 10 symptoms gives information that goes beyond the flu-like illness tallied by standard CDC surveillance. “We do not think that it will replace our traditional health care–based surveillance, but it gives us another set of data to look at,” Mr. Biggerstaff said in an interview.

The 10 symptoms that Flu Near You prompts users to report on each week are fever, cough, sore throat, shortness of breath, chills or night sweats, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, body ache, and headache. New participants are also asked whether they received a flu shot during the prior season, Aug. 1-July 31, as well as during the current season since the most recent July 31.

Flu Near You and other participatory surveillance tools also offer epidemiologists a way to track the participating cohort over time. That allows assessment of individual attack rates of influenza-like illness and other syndromes and also vaccine efficacy, Mr. Biggerstaff noted.

“It helps give us a feel for what is happening” with influenza. “We have worked with Flu Near You in the past and we continue to think about ways to work together on digital disease surveillance. We promote it to our state and local colleagues. We think it is a good resource for states to have,” he sad. The CDC’s influenza division is also assessing and using other novel forms of surveillance data, such as influenza and flu mentions on Twitter and searches on Google as well as a statistic Google maintains as Flu Trends.

Participatory surveillance is “very exciting” but is also “new and unproven and remains an experiment,” said Dr. Lawrence C. Madoff, director of the division of epidemiology and immunization at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health in Boston. But while participatory surveillance must still prove its role, U.S. public health officials “increasingly” accept the value of data from tools like Flu Near You, Dr. Madoff said in an interview. He cited the endorsement that participatory surveillance received in recent surveillance and early-detection recommendations from the World Health Organization. The 100,000 participants in Flu Near You give it a “critical mass that will become even more robust as it continues to grow,” Dr. Madoff said.

Further growth is clearly a priority for Flu Near You. “We’re now very excited to promote Flu Near You in a big way to try to get more numbers there and see if we can have a faster system for picking up influenza,” said Dr. Mark S. Smolinski, director of global health at Skoll.

“We are still trying to think through how do we get [Flu Near You] into the general consciousness” of more Americans, said Dr. Brownstein. While participants, not all of whom are active every week, provide enough data to show good correlation with the CDC’s routine surveillance on a national scale, if Flu Near You “had enough numbers we could drill down into subpopulations,” he noted. For now, the volume of participation makes subgroups too scanty in size for meaningful analysis, Dr. Brownstein conceded.

Mass gathering surveillance in Brazil

The Brazilian surveillance program at the World Cup was modeled on Flu Near You, but Dr. Libel, Dr. Smolinski, and their collaborators produced the app in about 8 weeks after receiving very short notice of the Brazilians’ interest. The weekly, symptom surveillance questions posed by the app replicated seven symptoms from Flu Near You – fever, cough, sore throat, shortness of breath, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, and headache – and added three new symptoms to the survey: joint pain, bleeding, and red spots on body. This allowed the Health Ministry to also monitor for outbreaks of other infections including measles, cholera, dengue, and chikungunya, Dr. Libel said. The Brazilian app also asked participants each week whether they had been in contact with anyone who had any of the 10 listed symptoms, and whether they had looked for health care services. No outbreaks of any type occurred in Brazil during the World Cup, but during the period it was actively used 27% of the frequent respondents reported experiencing at least one symptom.

The first Brazilian effort “was basically a pilot program,” with little advance promotion, Dr. Smolinksi said in an interview. Officials of the Brazilian Ministry of Health were “impressed” with the data collected. They also liked the ability of the system to push out information on health care access to registered users, and the potential the app offered to send out urgent public health messages. “What the Health Ministry loved the most was that if there had been an outbreak they could have immediately reached out to fans,” Dr. Smolinski said.

The Ministry has interest in expanded surveillance and outreach programs for Carnival and the 2016 Summer Olympics, and Dr. Smolinski and his associates are hopeful that the International Olympics Committee will be receptive to the program and aid in its promotion during 2016. They are also planning to expand beyond smart phones and include the capability to interact with users via text and voice messages.

“We hope we will have huge numbers at the Olympics,” to better document the role participatory surveillance can play at mass gatherings, Dr. Smolinski said.

Dr. Libel, Dr. Brownstein, Mr. Biggerstaff, Dr. Smolinski, and Dr. Madoff had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM IMED 2014

Ebola entrenched in West Africa, recurrence inevitable

VIENNA – The world had better get used to dealing with Ebola virus outbreaks, because even if the west African outbreak comes under control others will inevitably follow until an effective vaccine becomes widely used.

On top of that, experts who gathered at the International Meeting on Emerging Disease and Surveillance said that they saw no quick end to the current west African outbreak.

“At this point, Ebola is so entrenched in west Africa that it will come back again. It is basically part of the [west African] ecology,” Dr. Adriano G. Duse said in an interview. He also painted a pessimistic picture of short-term prospects for controlling the current outbreak.

“It will be around [in west Africa] for at least the next year. There is no sign of it abating,” said Dr. Duse, professor and head of the department of clinical microbiology and infectious diseases at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, and a specialist in viral hemorrhagic fevers. “We suspect that the [Ebola] virus has been around in west Africa for a long time, and it was just a matter of time until it went into people.” He noted that the Ebola species currently circulating in west Africa closely matches the Zaire strain that was the type that first surfaced in people in 1976.

“We are now so high in numbers in west Africa that it will take months” to control the current outbreak, agreed Dr. Hilde de Clerck, a family physician who serves as a mobile implementation officer for viral hemorrhagic fevers for Médicins Sans Frontières (MSF; Doctors Without Borders), who began working last March in Guinea on patient care and infection control. “At MSF, we are planning that it will take at least 6-12 months, but that is a guess; we have no clue” how long the current outbreak will continue, Dr. de Clerck said in an interview. “At this time, we are running behind.”

On Nov. 14, the World Health Organization (WHO) pegged the number of Ebola virus infections known to have occurred in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia as of Nov. 11 at 14,383 (with a total of 14,413 total infection worldwide since the outbreak began), with 5,165 Ebola fatalities in west Africa and 5,177 worldwide. Dr. de Clerck, Dr. Duse, and others said that they believe that the WHO’s numbers greatly underestimate the true scope of the outbreak, even though the official numbers dwarf the size of all prior Ebola virus outbreaks since the virus first emerged in 1976; previous outbreaks always involved fewer than 1,000 infected people.

“The numbers we have seen show that the WHO’s numbers can’t be right,” Dr. de Clerck said.

Factors fueling Ebola’s spread

Dr. de Clerck attributed the unprecedented spread of Ebola during this outbreak to the high mobility of the people who live in the region where Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia share borders. She described people in the region who routinely travel as much as several hundred kilometers from one day to the next, and the easy flow of traffic from one country to another. She also cited as a major factor in the virus’s spread the large funerals traditionally held by the people in the region that typically involve contact with the body of the deceased.

But perhaps most important in the outbreak’s spread was a slow initial response to the first cases in the region. Dr. Duse criticized the governments of the three affected countries for their lax response to the onset of the outbreak, while he also praised Nigeria for taking a dramatically different tack.

The initial response to Ebola in Guinea and its neighboring countries was “denial” and “apathy,” and the responses also “lacked funding,” Dr. Duse said at the meeting. “It would have come to an end much sooner if the response had been mobilized quicker.” In contrast, the Nigerian response “was exceptionally swift,” and serves as a “role model for how to approach” future Ebola outbreaks.

Oyewale Tomori, D.V.M., Ph.D., president of the Nigerian Academy of Science, called the approach of many African countries to Ebola as “an ocean of apathy, denial, and unpreparedness.” In Nigeria, an Ebola management center opened 3 days after an Ebola-infected person arrived at Lagos airport from Liberia on July 20. That one case led to the infection of 20 other people, but the chain of infection stopped there, helped no doubt by a physician strike at the time which meant the index case went to a private hospital instead of a public hospital.

“We were lucky,” said Dr. Tomori. “We would have had a much bigger problem if the patient had gone to a teaching hospital.”

On Oct. 20, the WHO declared Nigeria Ebola free.

Ebola also spread this year in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) starting in August, an outbreak documented as unrelated to the one in west Africa and resulting from a DRC resident eating Ebola-carrying bushmeat. In the DRC, a quick and thorough response contained the spread and appears to have brought the outbreak to an end. On Nov. 15, the DRC’s minister of health said that the outbreak was over.

The experience this year in both Nigeria and the DRC shows that “Ebola is completely preventable if you educate people on how to avoid it,” said William Karesh, D.V.M., executive vice president for health and policy at the EcoHealth Alliance in New York.

Prospects for the west African outbreak

Given Ebola’s spread now in west Africa, “it is incredibly daunting to isolate all the cases,” said Dr. Lawrence C. Madoff, a professor of medicine at the University of Massachusetts in Worcester and director of epidemiology and immunization at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health in Boston. “The infrastructure [in the affected west African countries] is missing, challenged, or stretched way too thin, and it’s been incredibly difficult,” but he added that eventually he expects the epidemic curve of Ebola to peak and fall.

“As a rule, outbreaks end, and I don’t see any reason why this outbreak won’t also end. Sometimes, like in the great plagues of the Middle Ages, they can go on for a long time and involve many people, but eventually they do end.”

Dr. Duse agreed, and cited Ebola’s high mortality rate as a factor that limits the duration of outbreaks. “There has never been an Ebola outbreak that was sustained,” he noted.

“Humans are not Ebola carriers; they either die or recover, and stop shedding virus and are immune,” noted Dr. Karesh. But even when the current outbreak in west Africa ends, the threat remains of new introductions of Ebola into people from the reservoirs of virus that exist in bats and primates. “By the time the west African outbreak is controlled, there could be other spillover events” from animals to people, he cautioned.

Dr. Duse, Dr. de Clerck, Dr. Tomori, Dr. Karesh, and Dr. Madoff had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

VIENNA – The world had better get used to dealing with Ebola virus outbreaks, because even if the west African outbreak comes under control others will inevitably follow until an effective vaccine becomes widely used.

On top of that, experts who gathered at the International Meeting on Emerging Disease and Surveillance said that they saw no quick end to the current west African outbreak.

“At this point, Ebola is so entrenched in west Africa that it will come back again. It is basically part of the [west African] ecology,” Dr. Adriano G. Duse said in an interview. He also painted a pessimistic picture of short-term prospects for controlling the current outbreak.

“It will be around [in west Africa] for at least the next year. There is no sign of it abating,” said Dr. Duse, professor and head of the department of clinical microbiology and infectious diseases at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, and a specialist in viral hemorrhagic fevers. “We suspect that the [Ebola] virus has been around in west Africa for a long time, and it was just a matter of time until it went into people.” He noted that the Ebola species currently circulating in west Africa closely matches the Zaire strain that was the type that first surfaced in people in 1976.

“We are now so high in numbers in west Africa that it will take months” to control the current outbreak, agreed Dr. Hilde de Clerck, a family physician who serves as a mobile implementation officer for viral hemorrhagic fevers for Médicins Sans Frontières (MSF; Doctors Without Borders), who began working last March in Guinea on patient care and infection control. “At MSF, we are planning that it will take at least 6-12 months, but that is a guess; we have no clue” how long the current outbreak will continue, Dr. de Clerck said in an interview. “At this time, we are running behind.”

On Nov. 14, the World Health Organization (WHO) pegged the number of Ebola virus infections known to have occurred in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia as of Nov. 11 at 14,383 (with a total of 14,413 total infection worldwide since the outbreak began), with 5,165 Ebola fatalities in west Africa and 5,177 worldwide. Dr. de Clerck, Dr. Duse, and others said that they believe that the WHO’s numbers greatly underestimate the true scope of the outbreak, even though the official numbers dwarf the size of all prior Ebola virus outbreaks since the virus first emerged in 1976; previous outbreaks always involved fewer than 1,000 infected people.

“The numbers we have seen show that the WHO’s numbers can’t be right,” Dr. de Clerck said.

Factors fueling Ebola’s spread

Dr. de Clerck attributed the unprecedented spread of Ebola during this outbreak to the high mobility of the people who live in the region where Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia share borders. She described people in the region who routinely travel as much as several hundred kilometers from one day to the next, and the easy flow of traffic from one country to another. She also cited as a major factor in the virus’s spread the large funerals traditionally held by the people in the region that typically involve contact with the body of the deceased.

But perhaps most important in the outbreak’s spread was a slow initial response to the first cases in the region. Dr. Duse criticized the governments of the three affected countries for their lax response to the onset of the outbreak, while he also praised Nigeria for taking a dramatically different tack.

The initial response to Ebola in Guinea and its neighboring countries was “denial” and “apathy,” and the responses also “lacked funding,” Dr. Duse said at the meeting. “It would have come to an end much sooner if the response had been mobilized quicker.” In contrast, the Nigerian response “was exceptionally swift,” and serves as a “role model for how to approach” future Ebola outbreaks.

Oyewale Tomori, D.V.M., Ph.D., president of the Nigerian Academy of Science, called the approach of many African countries to Ebola as “an ocean of apathy, denial, and unpreparedness.” In Nigeria, an Ebola management center opened 3 days after an Ebola-infected person arrived at Lagos airport from Liberia on July 20. That one case led to the infection of 20 other people, but the chain of infection stopped there, helped no doubt by a physician strike at the time which meant the index case went to a private hospital instead of a public hospital.

“We were lucky,” said Dr. Tomori. “We would have had a much bigger problem if the patient had gone to a teaching hospital.”

On Oct. 20, the WHO declared Nigeria Ebola free.

Ebola also spread this year in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) starting in August, an outbreak documented as unrelated to the one in west Africa and resulting from a DRC resident eating Ebola-carrying bushmeat. In the DRC, a quick and thorough response contained the spread and appears to have brought the outbreak to an end. On Nov. 15, the DRC’s minister of health said that the outbreak was over.

The experience this year in both Nigeria and the DRC shows that “Ebola is completely preventable if you educate people on how to avoid it,” said William Karesh, D.V.M., executive vice president for health and policy at the EcoHealth Alliance in New York.

Prospects for the west African outbreak

Given Ebola’s spread now in west Africa, “it is incredibly daunting to isolate all the cases,” said Dr. Lawrence C. Madoff, a professor of medicine at the University of Massachusetts in Worcester and director of epidemiology and immunization at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health in Boston. “The infrastructure [in the affected west African countries] is missing, challenged, or stretched way too thin, and it’s been incredibly difficult,” but he added that eventually he expects the epidemic curve of Ebola to peak and fall.

“As a rule, outbreaks end, and I don’t see any reason why this outbreak won’t also end. Sometimes, like in the great plagues of the Middle Ages, they can go on for a long time and involve many people, but eventually they do end.”

Dr. Duse agreed, and cited Ebola’s high mortality rate as a factor that limits the duration of outbreaks. “There has never been an Ebola outbreak that was sustained,” he noted.

“Humans are not Ebola carriers; they either die or recover, and stop shedding virus and are immune,” noted Dr. Karesh. But even when the current outbreak in west Africa ends, the threat remains of new introductions of Ebola into people from the reservoirs of virus that exist in bats and primates. “By the time the west African outbreak is controlled, there could be other spillover events” from animals to people, he cautioned.

Dr. Duse, Dr. de Clerck, Dr. Tomori, Dr. Karesh, and Dr. Madoff had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

VIENNA – The world had better get used to dealing with Ebola virus outbreaks, because even if the west African outbreak comes under control others will inevitably follow until an effective vaccine becomes widely used.

On top of that, experts who gathered at the International Meeting on Emerging Disease and Surveillance said that they saw no quick end to the current west African outbreak.

“At this point, Ebola is so entrenched in west Africa that it will come back again. It is basically part of the [west African] ecology,” Dr. Adriano G. Duse said in an interview. He also painted a pessimistic picture of short-term prospects for controlling the current outbreak.

“It will be around [in west Africa] for at least the next year. There is no sign of it abating,” said Dr. Duse, professor and head of the department of clinical microbiology and infectious diseases at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, and a specialist in viral hemorrhagic fevers. “We suspect that the [Ebola] virus has been around in west Africa for a long time, and it was just a matter of time until it went into people.” He noted that the Ebola species currently circulating in west Africa closely matches the Zaire strain that was the type that first surfaced in people in 1976.

“We are now so high in numbers in west Africa that it will take months” to control the current outbreak, agreed Dr. Hilde de Clerck, a family physician who serves as a mobile implementation officer for viral hemorrhagic fevers for Médicins Sans Frontières (MSF; Doctors Without Borders), who began working last March in Guinea on patient care and infection control. “At MSF, we are planning that it will take at least 6-12 months, but that is a guess; we have no clue” how long the current outbreak will continue, Dr. de Clerck said in an interview. “At this time, we are running behind.”

On Nov. 14, the World Health Organization (WHO) pegged the number of Ebola virus infections known to have occurred in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia as of Nov. 11 at 14,383 (with a total of 14,413 total infection worldwide since the outbreak began), with 5,165 Ebola fatalities in west Africa and 5,177 worldwide. Dr. de Clerck, Dr. Duse, and others said that they believe that the WHO’s numbers greatly underestimate the true scope of the outbreak, even though the official numbers dwarf the size of all prior Ebola virus outbreaks since the virus first emerged in 1976; previous outbreaks always involved fewer than 1,000 infected people.

“The numbers we have seen show that the WHO’s numbers can’t be right,” Dr. de Clerck said.

Factors fueling Ebola’s spread

Dr. de Clerck attributed the unprecedented spread of Ebola during this outbreak to the high mobility of the people who live in the region where Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia share borders. She described people in the region who routinely travel as much as several hundred kilometers from one day to the next, and the easy flow of traffic from one country to another. She also cited as a major factor in the virus’s spread the large funerals traditionally held by the people in the region that typically involve contact with the body of the deceased.

But perhaps most important in the outbreak’s spread was a slow initial response to the first cases in the region. Dr. Duse criticized the governments of the three affected countries for their lax response to the onset of the outbreak, while he also praised Nigeria for taking a dramatically different tack.

The initial response to Ebola in Guinea and its neighboring countries was “denial” and “apathy,” and the responses also “lacked funding,” Dr. Duse said at the meeting. “It would have come to an end much sooner if the response had been mobilized quicker.” In contrast, the Nigerian response “was exceptionally swift,” and serves as a “role model for how to approach” future Ebola outbreaks.

Oyewale Tomori, D.V.M., Ph.D., president of the Nigerian Academy of Science, called the approach of many African countries to Ebola as “an ocean of apathy, denial, and unpreparedness.” In Nigeria, an Ebola management center opened 3 days after an Ebola-infected person arrived at Lagos airport from Liberia on July 20. That one case led to the infection of 20 other people, but the chain of infection stopped there, helped no doubt by a physician strike at the time which meant the index case went to a private hospital instead of a public hospital.

“We were lucky,” said Dr. Tomori. “We would have had a much bigger problem if the patient had gone to a teaching hospital.”

On Oct. 20, the WHO declared Nigeria Ebola free.

Ebola also spread this year in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) starting in August, an outbreak documented as unrelated to the one in west Africa and resulting from a DRC resident eating Ebola-carrying bushmeat. In the DRC, a quick and thorough response contained the spread and appears to have brought the outbreak to an end. On Nov. 15, the DRC’s minister of health said that the outbreak was over.

The experience this year in both Nigeria and the DRC shows that “Ebola is completely preventable if you educate people on how to avoid it,” said William Karesh, D.V.M., executive vice president for health and policy at the EcoHealth Alliance in New York.

Prospects for the west African outbreak

Given Ebola’s spread now in west Africa, “it is incredibly daunting to isolate all the cases,” said Dr. Lawrence C. Madoff, a professor of medicine at the University of Massachusetts in Worcester and director of epidemiology and immunization at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health in Boston. “The infrastructure [in the affected west African countries] is missing, challenged, or stretched way too thin, and it’s been incredibly difficult,” but he added that eventually he expects the epidemic curve of Ebola to peak and fall.

“As a rule, outbreaks end, and I don’t see any reason why this outbreak won’t also end. Sometimes, like in the great plagues of the Middle Ages, they can go on for a long time and involve many people, but eventually they do end.”

Dr. Duse agreed, and cited Ebola’s high mortality rate as a factor that limits the duration of outbreaks. “There has never been an Ebola outbreak that was sustained,” he noted.

“Humans are not Ebola carriers; they either die or recover, and stop shedding virus and are immune,” noted Dr. Karesh. But even when the current outbreak in west Africa ends, the threat remains of new introductions of Ebola into people from the reservoirs of virus that exist in bats and primates. “By the time the west African outbreak is controlled, there could be other spillover events” from animals to people, he cautioned.

Dr. Duse, Dr. de Clerck, Dr. Tomori, Dr. Karesh, and Dr. Madoff had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM IMED 2014

VIDEO: West African Ebola scope makes control uncertain

VIENNA – The huge scope of the West African Ebola outbreak makes bringing it under control an unprecedented challenge with an uncertain outcome, Dr. Hilde de Clerck said in an interview during the International Meeting on Emerging Diseases and Surveillance.

The large number of people who have been infected with Ebola in the West African countries of Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia – close to 14,000 identified cases by the end of October – has forced clinicians on the scene, such as those working with Médicins Sans Frontières (MSF; Doctors Without Borders), to try new approaches in their attempt to rein in further spread of the infection, said Dr. de Clerk, an epidemiologist and family physician who serves as a field coordinator for MSF specializing in viral hemorrhagic fevers. Right now, it is hard to predict when the outbreak will be brought under control, she said. To watch an interview in which she discusses containment strategies, click here.

Dr. de Cleck had no disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

VIENNA – The huge scope of the West African Ebola outbreak makes bringing it under control an unprecedented challenge with an uncertain outcome, Dr. Hilde de Clerck said in an interview during the International Meeting on Emerging Diseases and Surveillance.

The large number of people who have been infected with Ebola in the West African countries of Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia – close to 14,000 identified cases by the end of October – has forced clinicians on the scene, such as those working with Médicins Sans Frontières (MSF; Doctors Without Borders), to try new approaches in their attempt to rein in further spread of the infection, said Dr. de Clerk, an epidemiologist and family physician who serves as a field coordinator for MSF specializing in viral hemorrhagic fevers. Right now, it is hard to predict when the outbreak will be brought under control, she said. To watch an interview in which she discusses containment strategies, click here.

Dr. de Cleck had no disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

VIENNA – The huge scope of the West African Ebola outbreak makes bringing it under control an unprecedented challenge with an uncertain outcome, Dr. Hilde de Clerck said in an interview during the International Meeting on Emerging Diseases and Surveillance.

The large number of people who have been infected with Ebola in the West African countries of Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia – close to 14,000 identified cases by the end of October – has forced clinicians on the scene, such as those working with Médicins Sans Frontières (MSF; Doctors Without Borders), to try new approaches in their attempt to rein in further spread of the infection, said Dr. de Clerk, an epidemiologist and family physician who serves as a field coordinator for MSF specializing in viral hemorrhagic fevers. Right now, it is hard to predict when the outbreak will be brought under control, she said. To watch an interview in which she discusses containment strategies, click here.

Dr. de Cleck had no disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT IMED 2014

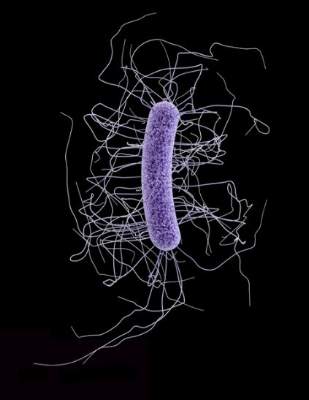

U.S. C. difficile mortality jumped sevenfold 1999-2008

VIENNA – U.S. deaths from Clostridium difficile infection jumped roughly sevenfold from 1999 to 2008, but in the ensuing years (2009-2012), remained stable at about the level first reached in 2008, according to analysis of cause-of-death data from the National Center for Health Statistics.

The increase occurred uniformly across all age groups older than 40 years; among patients 40 years or younger mortality from C. difficile infection remained low, at a rate at or below one death per one million people, Andrew Noymer, Ph.D., reported in a poster at the International Meeting on Emerging Diseases and Surveillance.

Among those patients aged 80 years or older, the mortality rate in recent years with C. difficile infection listed as the primary cause exceeded one death per 5,000 people, reported Dr. Noymer, a researcher in population health and disease prevention at the University of California, Irvine.

The mortality data provided no direct insight into the factors contributing to the rise in C. difficile deaths during 1999-2008, but previous reports documented an increased prevalence starting in 2000 of a “hypervirulent” strain of C. difficile circulating in North America and elsewhere (Critical Care 2008;12:203-10).

C. difficile infection as the underlying cause of death rose from less than one age-adjusted occurrence for every 200,000 people in 1999 to about 2.4 age-adjusted deaths per 100,000 in 2008, and then remained at about that level through 2012. Rates were similar in women and men.

When analyzed as any mention of C. difficile infection with another factor cited as the primary cause of death occurrences also rose roughly sevenfold from 1999 to 2008, from about one death for every 200,000 people to about 3.5 deaths per 100,000.

When C. difficile has been a contributing factor, the wide spectrum of causes of death that it can accompany “reads like a who’s who of conditions requiring inpatient clinical care,” Dr. Noymer said. “Given the nosocomial nature of C. difficile this is not surprising.”

The top three lethal conditions with C. difficile complication were atherosclerotic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and septicemia.

Dr. Noymer had no disclosures.

VIENNA – U.S. deaths from Clostridium difficile infection jumped roughly sevenfold from 1999 to 2008, but in the ensuing years (2009-2012), remained stable at about the level first reached in 2008, according to analysis of cause-of-death data from the National Center for Health Statistics.

The increase occurred uniformly across all age groups older than 40 years; among patients 40 years or younger mortality from C. difficile infection remained low, at a rate at or below one death per one million people, Andrew Noymer, Ph.D., reported in a poster at the International Meeting on Emerging Diseases and Surveillance.

Among those patients aged 80 years or older, the mortality rate in recent years with C. difficile infection listed as the primary cause exceeded one death per 5,000 people, reported Dr. Noymer, a researcher in population health and disease prevention at the University of California, Irvine.

The mortality data provided no direct insight into the factors contributing to the rise in C. difficile deaths during 1999-2008, but previous reports documented an increased prevalence starting in 2000 of a “hypervirulent” strain of C. difficile circulating in North America and elsewhere (Critical Care 2008;12:203-10).

C. difficile infection as the underlying cause of death rose from less than one age-adjusted occurrence for every 200,000 people in 1999 to about 2.4 age-adjusted deaths per 100,000 in 2008, and then remained at about that level through 2012. Rates were similar in women and men.

When analyzed as any mention of C. difficile infection with another factor cited as the primary cause of death occurrences also rose roughly sevenfold from 1999 to 2008, from about one death for every 200,000 people to about 3.5 deaths per 100,000.

When C. difficile has been a contributing factor, the wide spectrum of causes of death that it can accompany “reads like a who’s who of conditions requiring inpatient clinical care,” Dr. Noymer said. “Given the nosocomial nature of C. difficile this is not surprising.”

The top three lethal conditions with C. difficile complication were atherosclerotic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and septicemia.

Dr. Noymer had no disclosures.

VIENNA – U.S. deaths from Clostridium difficile infection jumped roughly sevenfold from 1999 to 2008, but in the ensuing years (2009-2012), remained stable at about the level first reached in 2008, according to analysis of cause-of-death data from the National Center for Health Statistics.

The increase occurred uniformly across all age groups older than 40 years; among patients 40 years or younger mortality from C. difficile infection remained low, at a rate at or below one death per one million people, Andrew Noymer, Ph.D., reported in a poster at the International Meeting on Emerging Diseases and Surveillance.

Among those patients aged 80 years or older, the mortality rate in recent years with C. difficile infection listed as the primary cause exceeded one death per 5,000 people, reported Dr. Noymer, a researcher in population health and disease prevention at the University of California, Irvine.

The mortality data provided no direct insight into the factors contributing to the rise in C. difficile deaths during 1999-2008, but previous reports documented an increased prevalence starting in 2000 of a “hypervirulent” strain of C. difficile circulating in North America and elsewhere (Critical Care 2008;12:203-10).

C. difficile infection as the underlying cause of death rose from less than one age-adjusted occurrence for every 200,000 people in 1999 to about 2.4 age-adjusted deaths per 100,000 in 2008, and then remained at about that level through 2012. Rates were similar in women and men.

When analyzed as any mention of C. difficile infection with another factor cited as the primary cause of death occurrences also rose roughly sevenfold from 1999 to 2008, from about one death for every 200,000 people to about 3.5 deaths per 100,000.

When C. difficile has been a contributing factor, the wide spectrum of causes of death that it can accompany “reads like a who’s who of conditions requiring inpatient clinical care,” Dr. Noymer said. “Given the nosocomial nature of C. difficile this is not surprising.”

The top three lethal conditions with C. difficile complication were atherosclerotic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and septicemia.

Dr. Noymer had no disclosures.

AT IMED 2014

Key clinical point: During 1999-2008, U.S. deaths attributable to Clostridium difficile infection rose about sevenfold, and then plateaued at that high level through 2012.

Major finding: Age-adjusted C. difficile mortality was less than 1/200,000 in 1999 and about 2.4/100,000 in 2008.

Data source: Review of national mortality data collected by the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics.

Disclosures: Dr. Noymer had no disclosures.