User login

ED revisits declined with follow-up on antibiotic prescribing

SAN FRANCISCO – Blood and urine culture results need to be followed up in emergency department patients discharged on empiric antibiotic therapy.

During a 4-month prospective study, pharmacists at the Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit found antibiotic-bacteria mismatches in 26% of 196 ED patients based on cross-checking of culture results and antibiotics prescribed.

When alerted to the problems, physicians called the patients to change their antibiotic regimens based on the pharmacists’ recommendations.

Compared to 124 well-matched historical controls who did not get the extra oversight, the 196 patients had a 7% combined decrease in 72-hour ED revisits and 30-day admissions (17% vs. 10%, P = .08). Among uninsured patients, ED revisits dropped more than 10% (15% vs. 2%, P = .04).

The situation isn’t unique to Henry Ford. Empiric treatment is common pending culture results, and sometimes even the best guesses are wrong, said lead investigator Lisa Dumkow, Pharm.D., a pharmacy resident at Henry Ford, at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy . ED physicians had been struggling with culture follow-up and the hospital pharmacists "were really excited to have us there to help them. It was nice for patient satisfaction, too. Some of the patients were appreciative."

Most of the patients in the study were women with urinary tract infections caused by Escherichia coli.

The majority of pharmacist interventions were for pathogen nonsusceptibility, followed by inappropriate dose, or duration of antibiotic therapy.

The conference was sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology. The researchers said they have no disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Blood and urine culture results need to be followed up in emergency department patients discharged on empiric antibiotic therapy.

During a 4-month prospective study, pharmacists at the Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit found antibiotic-bacteria mismatches in 26% of 196 ED patients based on cross-checking of culture results and antibiotics prescribed.

When alerted to the problems, physicians called the patients to change their antibiotic regimens based on the pharmacists’ recommendations.

Compared to 124 well-matched historical controls who did not get the extra oversight, the 196 patients had a 7% combined decrease in 72-hour ED revisits and 30-day admissions (17% vs. 10%, P = .08). Among uninsured patients, ED revisits dropped more than 10% (15% vs. 2%, P = .04).

The situation isn’t unique to Henry Ford. Empiric treatment is common pending culture results, and sometimes even the best guesses are wrong, said lead investigator Lisa Dumkow, Pharm.D., a pharmacy resident at Henry Ford, at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy . ED physicians had been struggling with culture follow-up and the hospital pharmacists "were really excited to have us there to help them. It was nice for patient satisfaction, too. Some of the patients were appreciative."

Most of the patients in the study were women with urinary tract infections caused by Escherichia coli.

The majority of pharmacist interventions were for pathogen nonsusceptibility, followed by inappropriate dose, or duration of antibiotic therapy.

The conference was sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology. The researchers said they have no disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Blood and urine culture results need to be followed up in emergency department patients discharged on empiric antibiotic therapy.

During a 4-month prospective study, pharmacists at the Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit found antibiotic-bacteria mismatches in 26% of 196 ED patients based on cross-checking of culture results and antibiotics prescribed.

When alerted to the problems, physicians called the patients to change their antibiotic regimens based on the pharmacists’ recommendations.

Compared to 124 well-matched historical controls who did not get the extra oversight, the 196 patients had a 7% combined decrease in 72-hour ED revisits and 30-day admissions (17% vs. 10%, P = .08). Among uninsured patients, ED revisits dropped more than 10% (15% vs. 2%, P = .04).

The situation isn’t unique to Henry Ford. Empiric treatment is common pending culture results, and sometimes even the best guesses are wrong, said lead investigator Lisa Dumkow, Pharm.D., a pharmacy resident at Henry Ford, at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy . ED physicians had been struggling with culture follow-up and the hospital pharmacists "were really excited to have us there to help them. It was nice for patient satisfaction, too. Some of the patients were appreciative."

Most of the patients in the study were women with urinary tract infections caused by Escherichia coli.

The majority of pharmacist interventions were for pathogen nonsusceptibility, followed by inappropriate dose, or duration of antibiotic therapy.

The conference was sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology. The researchers said they have no disclosures.

AT THE INTERSCIENCE CONFERENCE ON ANTIMICROBIAL AGENTS AND CHEMOTHERAPY

Major Finding: Seventy-two–hour ED revisits and 30-day hospital admissions dropped 7% when pharmacists checked culture and sensitivity reports and had empiric antibiotic therapy adjusted as needed following ED visits.

Data Source: Results were taken from a prospective study involving 320 patients.

Disclosures: The researchers said they have no disclosures.

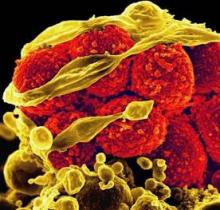

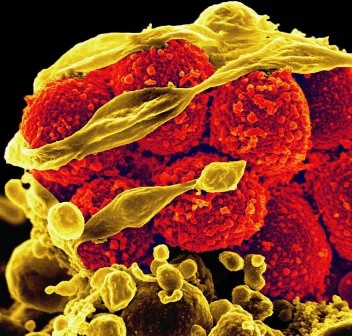

Daptomycin Best for MRSA Bacteremia With High Vancomycin MICs

SAN FRANCISCO – An early switch to daptomycin improved clinical outcomes compared with dose-adjusted vancomycin in patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and a vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration greater than 1 mcg/mL.

The findings come from the first matched comparison of daptomycin as early therapy versus dose-optimized vancomycin for this patient population.

"Continued vancomycin use is an independent predictor of clinical failure" in these patients, lead study investigator Kyle P. Murray, Pharm.D., said at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

Dr. Murray and his associates at Detroit Medical Center and the Anti-Infective Research Laboratory at Wayne State University in Detroit evaluated data from 170 inpatients who had MRSA bacteremia and a vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) greater than 1 mcg/mL and were treated with daptomycin (at least 6 mg/kg daily) or vancomycin (a target trough of 15-20 mcg/mL). The patients were matched 1:1 on the basis of age, Pittsburgh bacteremia score, and their primary site of infection. The researchers excluded patients who had pneumonia or whose primary site of infection was an intravenous catheter, daptomycin-treated patients who received more than 72 hours of initial vancomycin, and patients who required renal replacement therapy.

The primary outcome was clinical failure, defined as either microbiological failure (bacteremia persisting for 7 or more days from the initial positive blood culture) or mortality within 30 days of the initial positive culture.

Baseline characteristics were similar between the daptomycin and vancomycin groups in terms of age (a median of 57 vs. 56 years, respectively), Pittsburgh bacteremia score (2 in each group), and Charlson comorbidity index score (5 vs. 4). The median daptomycin dose was 8.4 mg/kg per day and the median initial vancomycin trough was 12.9 mcg /mL. After dose adjustment, the median vancomycin trough was 17.6 mcg /mL.

Dr. Murray reported that 48% of patients in the vancomycin group experienced clinical failure compared with 20% of those in the daptomycin group, a difference that reached statistical significance with a P value of less than .001. There were also significant differences between the vancomycin and daptomycin groups in 30-day mortality (13% vs. 3.5%, respectively; P = .047) the proportion of patients with persistent bacteremia (42% vs. 19%; P = .001), and in the duration of bacteremia (a median of 3 vs. 5 days; P = .003). There were no significant differences between the treatment groups in the proportion of patients who were readmitted after 30 days (20% vs. 25%; P = .381).

After performing multivariate logistic regression analysis and adjusting for certain clinical variables, Dr. Murray and his associates observed three significant predictors of clinical failure: ICU admission (OR 5.8; P less than .001), vancomycin treatment (OR 4.5; P less than .001), and intravenous drug use (OR 3.0; P = .004).

Dr. Murray had no financial conflicts to disclose. Other coauthors disclosed having a consultant role with, receiving grant support from, or being a member of the speakers bureau for Merck, Pfizer, Cubist Pharmaceuticals, Astellas, Forest Pharmaceuticals, and Rib-X Pharmaceuticals.

The meeting was sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology.

SAN FRANCISCO – An early switch to daptomycin improved clinical outcomes compared with dose-adjusted vancomycin in patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and a vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration greater than 1 mcg/mL.

The findings come from the first matched comparison of daptomycin as early therapy versus dose-optimized vancomycin for this patient population.

"Continued vancomycin use is an independent predictor of clinical failure" in these patients, lead study investigator Kyle P. Murray, Pharm.D., said at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

Dr. Murray and his associates at Detroit Medical Center and the Anti-Infective Research Laboratory at Wayne State University in Detroit evaluated data from 170 inpatients who had MRSA bacteremia and a vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) greater than 1 mcg/mL and were treated with daptomycin (at least 6 mg/kg daily) or vancomycin (a target trough of 15-20 mcg/mL). The patients were matched 1:1 on the basis of age, Pittsburgh bacteremia score, and their primary site of infection. The researchers excluded patients who had pneumonia or whose primary site of infection was an intravenous catheter, daptomycin-treated patients who received more than 72 hours of initial vancomycin, and patients who required renal replacement therapy.

The primary outcome was clinical failure, defined as either microbiological failure (bacteremia persisting for 7 or more days from the initial positive blood culture) or mortality within 30 days of the initial positive culture.

Baseline characteristics were similar between the daptomycin and vancomycin groups in terms of age (a median of 57 vs. 56 years, respectively), Pittsburgh bacteremia score (2 in each group), and Charlson comorbidity index score (5 vs. 4). The median daptomycin dose was 8.4 mg/kg per day and the median initial vancomycin trough was 12.9 mcg /mL. After dose adjustment, the median vancomycin trough was 17.6 mcg /mL.

Dr. Murray reported that 48% of patients in the vancomycin group experienced clinical failure compared with 20% of those in the daptomycin group, a difference that reached statistical significance with a P value of less than .001. There were also significant differences between the vancomycin and daptomycin groups in 30-day mortality (13% vs. 3.5%, respectively; P = .047) the proportion of patients with persistent bacteremia (42% vs. 19%; P = .001), and in the duration of bacteremia (a median of 3 vs. 5 days; P = .003). There were no significant differences between the treatment groups in the proportion of patients who were readmitted after 30 days (20% vs. 25%; P = .381).

After performing multivariate logistic regression analysis and adjusting for certain clinical variables, Dr. Murray and his associates observed three significant predictors of clinical failure: ICU admission (OR 5.8; P less than .001), vancomycin treatment (OR 4.5; P less than .001), and intravenous drug use (OR 3.0; P = .004).

Dr. Murray had no financial conflicts to disclose. Other coauthors disclosed having a consultant role with, receiving grant support from, or being a member of the speakers bureau for Merck, Pfizer, Cubist Pharmaceuticals, Astellas, Forest Pharmaceuticals, and Rib-X Pharmaceuticals.

The meeting was sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology.

SAN FRANCISCO – An early switch to daptomycin improved clinical outcomes compared with dose-adjusted vancomycin in patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and a vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration greater than 1 mcg/mL.

The findings come from the first matched comparison of daptomycin as early therapy versus dose-optimized vancomycin for this patient population.

"Continued vancomycin use is an independent predictor of clinical failure" in these patients, lead study investigator Kyle P. Murray, Pharm.D., said at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

Dr. Murray and his associates at Detroit Medical Center and the Anti-Infective Research Laboratory at Wayne State University in Detroit evaluated data from 170 inpatients who had MRSA bacteremia and a vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) greater than 1 mcg/mL and were treated with daptomycin (at least 6 mg/kg daily) or vancomycin (a target trough of 15-20 mcg/mL). The patients were matched 1:1 on the basis of age, Pittsburgh bacteremia score, and their primary site of infection. The researchers excluded patients who had pneumonia or whose primary site of infection was an intravenous catheter, daptomycin-treated patients who received more than 72 hours of initial vancomycin, and patients who required renal replacement therapy.

The primary outcome was clinical failure, defined as either microbiological failure (bacteremia persisting for 7 or more days from the initial positive blood culture) or mortality within 30 days of the initial positive culture.

Baseline characteristics were similar between the daptomycin and vancomycin groups in terms of age (a median of 57 vs. 56 years, respectively), Pittsburgh bacteremia score (2 in each group), and Charlson comorbidity index score (5 vs. 4). The median daptomycin dose was 8.4 mg/kg per day and the median initial vancomycin trough was 12.9 mcg /mL. After dose adjustment, the median vancomycin trough was 17.6 mcg /mL.

Dr. Murray reported that 48% of patients in the vancomycin group experienced clinical failure compared with 20% of those in the daptomycin group, a difference that reached statistical significance with a P value of less than .001. There were also significant differences between the vancomycin and daptomycin groups in 30-day mortality (13% vs. 3.5%, respectively; P = .047) the proportion of patients with persistent bacteremia (42% vs. 19%; P = .001), and in the duration of bacteremia (a median of 3 vs. 5 days; P = .003). There were no significant differences between the treatment groups in the proportion of patients who were readmitted after 30 days (20% vs. 25%; P = .381).

After performing multivariate logistic regression analysis and adjusting for certain clinical variables, Dr. Murray and his associates observed three significant predictors of clinical failure: ICU admission (OR 5.8; P less than .001), vancomycin treatment (OR 4.5; P less than .001), and intravenous drug use (OR 3.0; P = .004).

Dr. Murray had no financial conflicts to disclose. Other coauthors disclosed having a consultant role with, receiving grant support from, or being a member of the speakers bureau for Merck, Pfizer, Cubist Pharmaceuticals, Astellas, Forest Pharmaceuticals, and Rib-X Pharmaceuticals.

The meeting was sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology.

AT THE ANNUAL INTERSCIENCE CONFERENCE ON ANTIMICROBIAL AGENTS AND CHEMOTHERAPY

Delay Antiretroviral Therapy in HIV Patients with Cryptococcal Meningitis

SAN FRANCISCO – In treatment-naive HIV patients with cryptococcal meningitis, antiretroviral therapy should be delayed until patients’ cerebrospinal fluid proves cleared of cryptococcal infection, according to Dr. David Boulware, distinguished assistant professor of infectious diseases and international medicine at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

The meningitis "must be treated optimally first," he said at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. For most patients, antiretroviral therapy should come perhaps 3-4 weeks after the start of induction therapy, when their cerebrospinal fluid is again sterile. ART should come later, perhaps 6 weeks or longer, in patients who don’t mount a strong CSF inflammatory response, and in those with a persistent altered mental status; both will have a harder time clearing their CSF, he said.

The recommendations come from a study led by Dr. Boulware that pitted early ART against delayed ART in ART-naive HIV patients with cryptococcal meningitis in Uganda and South Africa, where cryptococcal meningitis is a leading killer of HIV patients. It has not been clear until now when it’s best to start ART in HIV patients with the condition.

The researchers randomized 87 patients to start an efavirenz and nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor ART regimen 7-11 days after starting cryptococcal meningitis induction therapy with 0.7-1.0 mg/kg per day of amphotericin and 800 mg/day of fluconazole. In 87 other patients, the ART regimen started 5 weeks or more after the start of induction, when amphotericin had been discontinued and fluconazole had been stepped down to a lower dose.

The trial was halted in April 2012 – significantly short of its enrollment target – after researchers realized that early-ART patients were 1.7 times more likely than delayed-ART patients to die within 6 months (95% confidence interval 1.03-2.87). Six-month mortality was 42.5% (37 patients) in the early arm, and 27.6% (24) in the delayed arm.

"You should not do early ART [in this group]. First, focus on the induction treatment to sterilize the CSF. There is no benefit in starting ART during cryptococcal induction therapy. It’s not going to help, and it’s likely to be harmful to a large proportion of subjects," Dr. Boulware said.

The mortality differences were driven primarily by patients who entered the trial with altered mental status – Glasgow Coma Scale scores below 15 – and by those who didn’t mount strong CSF inflammatory responses.

But even patients who were not sick showed "no benefits and no trends of benefits" with early ART, Dr. Boulware said.

Based on the results, "we aim to start ART at around 3 to 4 weeks" when "you’re confident the CSF is sterile," he said. He also stressed the importance of making sure the CSF culture is sterile before reducing the fluconazole dose.

A longer delay is warranted in patients with little CSF inflammation, because early ART in patients who have not yet cleared the cryptococcal infection could kick off an immune reconstitution syndrome. A longer wait also is the way to go for patients with altered mental status. "Get them better, get them ambulating, get them moving around" before starting ART, Dr. Boulware said.

The mean age of the trial subjects was 35 years. Patients were about evenly split between male and female.

The conference was sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology. The trial was sponsored by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Dr. Boulware disclosed research support from GlaxoSmithKline.

SAN FRANCISCO – In treatment-naive HIV patients with cryptococcal meningitis, antiretroviral therapy should be delayed until patients’ cerebrospinal fluid proves cleared of cryptococcal infection, according to Dr. David Boulware, distinguished assistant professor of infectious diseases and international medicine at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

The meningitis "must be treated optimally first," he said at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. For most patients, antiretroviral therapy should come perhaps 3-4 weeks after the start of induction therapy, when their cerebrospinal fluid is again sterile. ART should come later, perhaps 6 weeks or longer, in patients who don’t mount a strong CSF inflammatory response, and in those with a persistent altered mental status; both will have a harder time clearing their CSF, he said.

The recommendations come from a study led by Dr. Boulware that pitted early ART against delayed ART in ART-naive HIV patients with cryptococcal meningitis in Uganda and South Africa, where cryptococcal meningitis is a leading killer of HIV patients. It has not been clear until now when it’s best to start ART in HIV patients with the condition.

The researchers randomized 87 patients to start an efavirenz and nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor ART regimen 7-11 days after starting cryptococcal meningitis induction therapy with 0.7-1.0 mg/kg per day of amphotericin and 800 mg/day of fluconazole. In 87 other patients, the ART regimen started 5 weeks or more after the start of induction, when amphotericin had been discontinued and fluconazole had been stepped down to a lower dose.

The trial was halted in April 2012 – significantly short of its enrollment target – after researchers realized that early-ART patients were 1.7 times more likely than delayed-ART patients to die within 6 months (95% confidence interval 1.03-2.87). Six-month mortality was 42.5% (37 patients) in the early arm, and 27.6% (24) in the delayed arm.

"You should not do early ART [in this group]. First, focus on the induction treatment to sterilize the CSF. There is no benefit in starting ART during cryptococcal induction therapy. It’s not going to help, and it’s likely to be harmful to a large proportion of subjects," Dr. Boulware said.

The mortality differences were driven primarily by patients who entered the trial with altered mental status – Glasgow Coma Scale scores below 15 – and by those who didn’t mount strong CSF inflammatory responses.

But even patients who were not sick showed "no benefits and no trends of benefits" with early ART, Dr. Boulware said.

Based on the results, "we aim to start ART at around 3 to 4 weeks" when "you’re confident the CSF is sterile," he said. He also stressed the importance of making sure the CSF culture is sterile before reducing the fluconazole dose.

A longer delay is warranted in patients with little CSF inflammation, because early ART in patients who have not yet cleared the cryptococcal infection could kick off an immune reconstitution syndrome. A longer wait also is the way to go for patients with altered mental status. "Get them better, get them ambulating, get them moving around" before starting ART, Dr. Boulware said.

The mean age of the trial subjects was 35 years. Patients were about evenly split between male and female.

The conference was sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology. The trial was sponsored by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Dr. Boulware disclosed research support from GlaxoSmithKline.

SAN FRANCISCO – In treatment-naive HIV patients with cryptococcal meningitis, antiretroviral therapy should be delayed until patients’ cerebrospinal fluid proves cleared of cryptococcal infection, according to Dr. David Boulware, distinguished assistant professor of infectious diseases and international medicine at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

The meningitis "must be treated optimally first," he said at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. For most patients, antiretroviral therapy should come perhaps 3-4 weeks after the start of induction therapy, when their cerebrospinal fluid is again sterile. ART should come later, perhaps 6 weeks or longer, in patients who don’t mount a strong CSF inflammatory response, and in those with a persistent altered mental status; both will have a harder time clearing their CSF, he said.

The recommendations come from a study led by Dr. Boulware that pitted early ART against delayed ART in ART-naive HIV patients with cryptococcal meningitis in Uganda and South Africa, where cryptococcal meningitis is a leading killer of HIV patients. It has not been clear until now when it’s best to start ART in HIV patients with the condition.

The researchers randomized 87 patients to start an efavirenz and nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor ART regimen 7-11 days after starting cryptococcal meningitis induction therapy with 0.7-1.0 mg/kg per day of amphotericin and 800 mg/day of fluconazole. In 87 other patients, the ART regimen started 5 weeks or more after the start of induction, when amphotericin had been discontinued and fluconazole had been stepped down to a lower dose.

The trial was halted in April 2012 – significantly short of its enrollment target – after researchers realized that early-ART patients were 1.7 times more likely than delayed-ART patients to die within 6 months (95% confidence interval 1.03-2.87). Six-month mortality was 42.5% (37 patients) in the early arm, and 27.6% (24) in the delayed arm.

"You should not do early ART [in this group]. First, focus on the induction treatment to sterilize the CSF. There is no benefit in starting ART during cryptococcal induction therapy. It’s not going to help, and it’s likely to be harmful to a large proportion of subjects," Dr. Boulware said.

The mortality differences were driven primarily by patients who entered the trial with altered mental status – Glasgow Coma Scale scores below 15 – and by those who didn’t mount strong CSF inflammatory responses.

But even patients who were not sick showed "no benefits and no trends of benefits" with early ART, Dr. Boulware said.

Based on the results, "we aim to start ART at around 3 to 4 weeks" when "you’re confident the CSF is sterile," he said. He also stressed the importance of making sure the CSF culture is sterile before reducing the fluconazole dose.

A longer delay is warranted in patients with little CSF inflammation, because early ART in patients who have not yet cleared the cryptococcal infection could kick off an immune reconstitution syndrome. A longer wait also is the way to go for patients with altered mental status. "Get them better, get them ambulating, get them moving around" before starting ART, Dr. Boulware said.

The mean age of the trial subjects was 35 years. Patients were about evenly split between male and female.

The conference was sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology. The trial was sponsored by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Dr. Boulware disclosed research support from GlaxoSmithKline.

AT THE ANNUAL INTERSCIENCE CONFERENCE ON ANTIMICROBIAL AGENTS AND CHEMOTHERAPY

Major Finding: HIV-infected patients with cryptococcal meningitis who started an antiviral regimen 7-11 days after starting cryptococcal meningitis induction therapy were 1.7 times as likely to die within 6 months (42.5% mortality) as patients who started an antiviral regimen after 5 or more weeks of induction therapy (27.6% mortality).

Data Source: This was a randomized study of 174 African HIV patients with cryptococcal meningitis.

Disclosures: Dr. Boulware received research funding from GlaxoSmithKline.

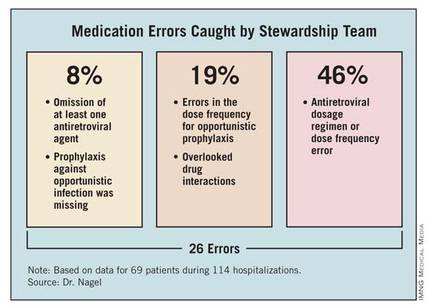

Stewardship Team Caught Drug Errors in Hospitalized HIV Patients

SAN FRANCISCO – Medication reviews by an antimicrobial stewardship team often led inpatient physicians to adjust antiretroviral regimens or opportunistic infection drugs in hospitalized patients with HIV, according to a recent study at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

The team, consisting of two physicians and three pharmacists specializing in infectious diseases, assessed medications for 69 HIV-infected patients during 114 hospitalizations from March to December 2011.

"Errors were present both at the time of admission and throughout hospitalization," Jerod L. Nagel, Pharm.D., said in a poster presentation at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

Some previous studies have suggested that prescribing errors can be reduced if clinical pharmacists review antiretroviral medications when a patient is admitted, but this may be the first study to integrate daily assessments of antiretroviral therapy and opportunistic infection prophylaxis into the work of a hospital antimicrobial stewardship team, said Dr. Nagel.

Hospitalizations averaged 4 days in duration. The antimicrobial stewardship team identified errors in antiretroviral therapy or opportunistic infection prophylaxis at a mean of 2 days after admission (range, 1-5 days after admission), and made recommendations to the inpatient physician in charge of the patient. All inpatient physicians accepted all of the team’s recommendations reported Dr. Nagel of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his associates.

As the management of HIV disease has shifted to a chronic-disease model that mainly utilizes outpatient care, hospital providers may be less knowledgeable about the complexities of antiretroviral regimens. The risk of medication errors also is influenced by drug-drug interactions and the need to adjust antiretroviral therapy for acute organ dysfunction that may go undetected throughout hospitalization, he said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology.

Patients in the study ranged in age from 14 to 82 years. They were admitted through the Medicine service in 63% of cases, Surgery in 16%, Hematology/Oncology in 15%, and Pediatrics in 2%; and the rest were admitted through other services.

The antimicrobial stewardship team incorporated into its work flow daily evaluations of the appropriateness of antiretroviral therapy and the dosage regimen (including renal and hepatic adjustments), the appropriateness of regimens and dosages for prophylaxis against opportunistic infections, and clinically significant drug-drug interactions. They evaluated only patients who were on antiretroviral therapy, and so could not assess potential errors in which antiretroviral therapy was omitted completely.

The team identified a total of 26 errors. Of these, 2 involved the omission of at least one antiretroviral agent (8%). Twelve errors involved the antiretroviral dosage regimen incorrectly adjusted for renal impairment or a dose frequency error independent of organ dysfunction (46%). Prophylaxis against opportunistic infection was missing in two patients (8%). The team identified errors in the dose frequency for opportunistic prophylaxis in five patients (19%). Five patients (19%) had clinically significant drug-drug interactions that were not being addressed, involving atazanavir and ranitidine, darunavir and vincristine, or phenytoin and lopinavir/ritonavir.

Enlisting an antimicrobial stewardship team to help manage hospitalized patients with HIV, who are at "a considerable risk of medication errors," might help detect the errors, shorten the duration of their effects, and improve patient care, Dr. Nagel suggested. Computerized systems to reconcile medications and assist clinical decision-making might help prevent these errors, he added.

A tradition of collaboration supports the stewardship team’s work. "We are fortunate to have an excellent working relationship between our hospitalists and clinical pharmacy staff," Dr. Nagel said. "So, implementing an initiative to improve the management of HIV patients by our antibiotic stewardship group wasn’t a major change of culture at our institution. Overall, I think physicians appreciate pharmacy input and don’t view it as ‘correcting’ errors."

The study did not include a historical control group for comparison or analyze clinical and virological outcomes associated with the team’s involvement, but the investigators may pursue these, as well as a cost analysis, in future studies, Dr. Nagel said in an interview.

In general, hospital antimicrobial stewardship teams have started to expand their roles beyond limited functions such as making sure a patient is on the right drug. "We’re trying to focus on a high-risk group and see if we can improve some outcomes," he said.

Dr. Nagel reported having no financial disclosures.

Having the antimicrobial stewardship team on hand to work with hospitalists at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, is valuable on several levels, said Dr. Jeffrey Rohde, assistant professor in the Hospital Medicine Program at the University of Michigan.

"In general, collaboration with other clinical professionals in the hospital not only contributes additional support to the increasingly difficult endeavor to care for complicated, acutely ill hospitalized patients, but it also helps to expand a sense of professional satisfaction to us hospitalists as we are able to be part of a like-minded team that is striving for a common goal, to provide the ideal inpatient care experience.

"Hence, this sort of collaboration with clinical pharmacy is very valuable to me as well as other hospitalists, as it is a natural extension of the multidisciplinary care that we provide to our patients every day."

The stewardship team’s presence also opens the door to more precise and accurate prescribing and better dialogue, Dr. Rohde said. "Optimizing medication regimens during an acute hospital stay can be challenging, especially for the wide variety of medications that are prescribed for patients with HIV. The vastly expanding list of new ART [antiretroviral therapy] medications provides both wonderful opportunities to optimize and personalize therapy, but this also presents a significant challenge to general medicine internists to accurately and effectively maintain and adjust these regimens.

"Having infectious disease pharmacy specialists also evaluating regimens and providing timely feedback and suggestions provides opportunities for better patient care. Furthermore, direct face-to-face communication allows for a discussion about different therapeutic options and a consensus to be reached, as opposed to the often unidirectional communication that is all too frequently done via paging."

Personal interaction has trumped technology in contributing to the initiative’s success, observed Dr. Rohde. "We have a strong and long-standing relationship with clinical pharmacy who round with the hospitalists daily, which serves as a wonderful foundation for such initiatives. Given the quality of the recommendations we receive from the clinical pharmacists and the antibiotic stewardship team, it is no surprise that all of their interventions were accepted and implemented. Some medication alerts have been built into our EMR [electronic medical record] and CPOE [computerized physician order entry] systems; however, these alerts all too often simply result in alert fatigue and are oftentimes only cursively evaluated.

"Having a discussion about how clinically important certain medication interactions and adjustments are is certainly more rewarding, informative, and beneficial than simply clicking on a pop-up box that is automatically generated," Dr. Rohde said.

"This pilot initiative is a great example arguing for the implementation of expanded medication reconciliation services for specialized patient populations with complex medication regimens."

Having the antimicrobial stewardship team on hand to work with hospitalists at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, is valuable on several levels, said Dr. Jeffrey Rohde, assistant professor in the Hospital Medicine Program at the University of Michigan.

"In general, collaboration with other clinical professionals in the hospital not only contributes additional support to the increasingly difficult endeavor to care for complicated, acutely ill hospitalized patients, but it also helps to expand a sense of professional satisfaction to us hospitalists as we are able to be part of a like-minded team that is striving for a common goal, to provide the ideal inpatient care experience.

"Hence, this sort of collaboration with clinical pharmacy is very valuable to me as well as other hospitalists, as it is a natural extension of the multidisciplinary care that we provide to our patients every day."

The stewardship team’s presence also opens the door to more precise and accurate prescribing and better dialogue, Dr. Rohde said. "Optimizing medication regimens during an acute hospital stay can be challenging, especially for the wide variety of medications that are prescribed for patients with HIV. The vastly expanding list of new ART [antiretroviral therapy] medications provides both wonderful opportunities to optimize and personalize therapy, but this also presents a significant challenge to general medicine internists to accurately and effectively maintain and adjust these regimens.

"Having infectious disease pharmacy specialists also evaluating regimens and providing timely feedback and suggestions provides opportunities for better patient care. Furthermore, direct face-to-face communication allows for a discussion about different therapeutic options and a consensus to be reached, as opposed to the often unidirectional communication that is all too frequently done via paging."

Personal interaction has trumped technology in contributing to the initiative’s success, observed Dr. Rohde. "We have a strong and long-standing relationship with clinical pharmacy who round with the hospitalists daily, which serves as a wonderful foundation for such initiatives. Given the quality of the recommendations we receive from the clinical pharmacists and the antibiotic stewardship team, it is no surprise that all of their interventions were accepted and implemented. Some medication alerts have been built into our EMR [electronic medical record] and CPOE [computerized physician order entry] systems; however, these alerts all too often simply result in alert fatigue and are oftentimes only cursively evaluated.

"Having a discussion about how clinically important certain medication interactions and adjustments are is certainly more rewarding, informative, and beneficial than simply clicking on a pop-up box that is automatically generated," Dr. Rohde said.

"This pilot initiative is a great example arguing for the implementation of expanded medication reconciliation services for specialized patient populations with complex medication regimens."

Having the antimicrobial stewardship team on hand to work with hospitalists at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, is valuable on several levels, said Dr. Jeffrey Rohde, assistant professor in the Hospital Medicine Program at the University of Michigan.

"In general, collaboration with other clinical professionals in the hospital not only contributes additional support to the increasingly difficult endeavor to care for complicated, acutely ill hospitalized patients, but it also helps to expand a sense of professional satisfaction to us hospitalists as we are able to be part of a like-minded team that is striving for a common goal, to provide the ideal inpatient care experience.

"Hence, this sort of collaboration with clinical pharmacy is very valuable to me as well as other hospitalists, as it is a natural extension of the multidisciplinary care that we provide to our patients every day."

The stewardship team’s presence also opens the door to more precise and accurate prescribing and better dialogue, Dr. Rohde said. "Optimizing medication regimens during an acute hospital stay can be challenging, especially for the wide variety of medications that are prescribed for patients with HIV. The vastly expanding list of new ART [antiretroviral therapy] medications provides both wonderful opportunities to optimize and personalize therapy, but this also presents a significant challenge to general medicine internists to accurately and effectively maintain and adjust these regimens.

"Having infectious disease pharmacy specialists also evaluating regimens and providing timely feedback and suggestions provides opportunities for better patient care. Furthermore, direct face-to-face communication allows for a discussion about different therapeutic options and a consensus to be reached, as opposed to the often unidirectional communication that is all too frequently done via paging."

Personal interaction has trumped technology in contributing to the initiative’s success, observed Dr. Rohde. "We have a strong and long-standing relationship with clinical pharmacy who round with the hospitalists daily, which serves as a wonderful foundation for such initiatives. Given the quality of the recommendations we receive from the clinical pharmacists and the antibiotic stewardship team, it is no surprise that all of their interventions were accepted and implemented. Some medication alerts have been built into our EMR [electronic medical record] and CPOE [computerized physician order entry] systems; however, these alerts all too often simply result in alert fatigue and are oftentimes only cursively evaluated.

"Having a discussion about how clinically important certain medication interactions and adjustments are is certainly more rewarding, informative, and beneficial than simply clicking on a pop-up box that is automatically generated," Dr. Rohde said.

"This pilot initiative is a great example arguing for the implementation of expanded medication reconciliation services for specialized patient populations with complex medication regimens."

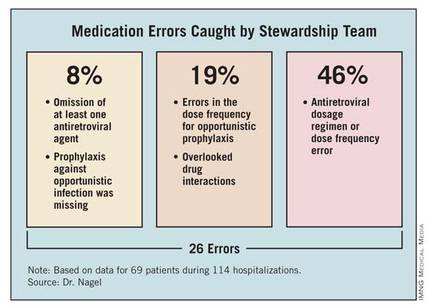

SAN FRANCISCO – Medication reviews by an antimicrobial stewardship team often led inpatient physicians to adjust antiretroviral regimens or opportunistic infection drugs in hospitalized patients with HIV, according to a recent study at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

The team, consisting of two physicians and three pharmacists specializing in infectious diseases, assessed medications for 69 HIV-infected patients during 114 hospitalizations from March to December 2011.

"Errors were present both at the time of admission and throughout hospitalization," Jerod L. Nagel, Pharm.D., said in a poster presentation at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

Some previous studies have suggested that prescribing errors can be reduced if clinical pharmacists review antiretroviral medications when a patient is admitted, but this may be the first study to integrate daily assessments of antiretroviral therapy and opportunistic infection prophylaxis into the work of a hospital antimicrobial stewardship team, said Dr. Nagel.

Hospitalizations averaged 4 days in duration. The antimicrobial stewardship team identified errors in antiretroviral therapy or opportunistic infection prophylaxis at a mean of 2 days after admission (range, 1-5 days after admission), and made recommendations to the inpatient physician in charge of the patient. All inpatient physicians accepted all of the team’s recommendations reported Dr. Nagel of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his associates.

As the management of HIV disease has shifted to a chronic-disease model that mainly utilizes outpatient care, hospital providers may be less knowledgeable about the complexities of antiretroviral regimens. The risk of medication errors also is influenced by drug-drug interactions and the need to adjust antiretroviral therapy for acute organ dysfunction that may go undetected throughout hospitalization, he said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology.

Patients in the study ranged in age from 14 to 82 years. They were admitted through the Medicine service in 63% of cases, Surgery in 16%, Hematology/Oncology in 15%, and Pediatrics in 2%; and the rest were admitted through other services.

The antimicrobial stewardship team incorporated into its work flow daily evaluations of the appropriateness of antiretroviral therapy and the dosage regimen (including renal and hepatic adjustments), the appropriateness of regimens and dosages for prophylaxis against opportunistic infections, and clinically significant drug-drug interactions. They evaluated only patients who were on antiretroviral therapy, and so could not assess potential errors in which antiretroviral therapy was omitted completely.

The team identified a total of 26 errors. Of these, 2 involved the omission of at least one antiretroviral agent (8%). Twelve errors involved the antiretroviral dosage regimen incorrectly adjusted for renal impairment or a dose frequency error independent of organ dysfunction (46%). Prophylaxis against opportunistic infection was missing in two patients (8%). The team identified errors in the dose frequency for opportunistic prophylaxis in five patients (19%). Five patients (19%) had clinically significant drug-drug interactions that were not being addressed, involving atazanavir and ranitidine, darunavir and vincristine, or phenytoin and lopinavir/ritonavir.

Enlisting an antimicrobial stewardship team to help manage hospitalized patients with HIV, who are at "a considerable risk of medication errors," might help detect the errors, shorten the duration of their effects, and improve patient care, Dr. Nagel suggested. Computerized systems to reconcile medications and assist clinical decision-making might help prevent these errors, he added.

A tradition of collaboration supports the stewardship team’s work. "We are fortunate to have an excellent working relationship between our hospitalists and clinical pharmacy staff," Dr. Nagel said. "So, implementing an initiative to improve the management of HIV patients by our antibiotic stewardship group wasn’t a major change of culture at our institution. Overall, I think physicians appreciate pharmacy input and don’t view it as ‘correcting’ errors."

The study did not include a historical control group for comparison or analyze clinical and virological outcomes associated with the team’s involvement, but the investigators may pursue these, as well as a cost analysis, in future studies, Dr. Nagel said in an interview.

In general, hospital antimicrobial stewardship teams have started to expand their roles beyond limited functions such as making sure a patient is on the right drug. "We’re trying to focus on a high-risk group and see if we can improve some outcomes," he said.

Dr. Nagel reported having no financial disclosures.

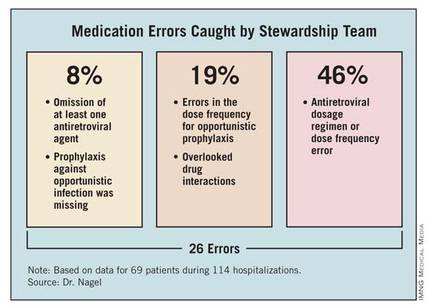

SAN FRANCISCO – Medication reviews by an antimicrobial stewardship team often led inpatient physicians to adjust antiretroviral regimens or opportunistic infection drugs in hospitalized patients with HIV, according to a recent study at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

The team, consisting of two physicians and three pharmacists specializing in infectious diseases, assessed medications for 69 HIV-infected patients during 114 hospitalizations from March to December 2011.

"Errors were present both at the time of admission and throughout hospitalization," Jerod L. Nagel, Pharm.D., said in a poster presentation at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

Some previous studies have suggested that prescribing errors can be reduced if clinical pharmacists review antiretroviral medications when a patient is admitted, but this may be the first study to integrate daily assessments of antiretroviral therapy and opportunistic infection prophylaxis into the work of a hospital antimicrobial stewardship team, said Dr. Nagel.

Hospitalizations averaged 4 days in duration. The antimicrobial stewardship team identified errors in antiretroviral therapy or opportunistic infection prophylaxis at a mean of 2 days after admission (range, 1-5 days after admission), and made recommendations to the inpatient physician in charge of the patient. All inpatient physicians accepted all of the team’s recommendations reported Dr. Nagel of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his associates.

As the management of HIV disease has shifted to a chronic-disease model that mainly utilizes outpatient care, hospital providers may be less knowledgeable about the complexities of antiretroviral regimens. The risk of medication errors also is influenced by drug-drug interactions and the need to adjust antiretroviral therapy for acute organ dysfunction that may go undetected throughout hospitalization, he said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology.

Patients in the study ranged in age from 14 to 82 years. They were admitted through the Medicine service in 63% of cases, Surgery in 16%, Hematology/Oncology in 15%, and Pediatrics in 2%; and the rest were admitted through other services.

The antimicrobial stewardship team incorporated into its work flow daily evaluations of the appropriateness of antiretroviral therapy and the dosage regimen (including renal and hepatic adjustments), the appropriateness of regimens and dosages for prophylaxis against opportunistic infections, and clinically significant drug-drug interactions. They evaluated only patients who were on antiretroviral therapy, and so could not assess potential errors in which antiretroviral therapy was omitted completely.

The team identified a total of 26 errors. Of these, 2 involved the omission of at least one antiretroviral agent (8%). Twelve errors involved the antiretroviral dosage regimen incorrectly adjusted for renal impairment or a dose frequency error independent of organ dysfunction (46%). Prophylaxis against opportunistic infection was missing in two patients (8%). The team identified errors in the dose frequency for opportunistic prophylaxis in five patients (19%). Five patients (19%) had clinically significant drug-drug interactions that were not being addressed, involving atazanavir and ranitidine, darunavir and vincristine, or phenytoin and lopinavir/ritonavir.

Enlisting an antimicrobial stewardship team to help manage hospitalized patients with HIV, who are at "a considerable risk of medication errors," might help detect the errors, shorten the duration of their effects, and improve patient care, Dr. Nagel suggested. Computerized systems to reconcile medications and assist clinical decision-making might help prevent these errors, he added.

A tradition of collaboration supports the stewardship team’s work. "We are fortunate to have an excellent working relationship between our hospitalists and clinical pharmacy staff," Dr. Nagel said. "So, implementing an initiative to improve the management of HIV patients by our antibiotic stewardship group wasn’t a major change of culture at our institution. Overall, I think physicians appreciate pharmacy input and don’t view it as ‘correcting’ errors."

The study did not include a historical control group for comparison or analyze clinical and virological outcomes associated with the team’s involvement, but the investigators may pursue these, as well as a cost analysis, in future studies, Dr. Nagel said in an interview.

In general, hospital antimicrobial stewardship teams have started to expand their roles beyond limited functions such as making sure a patient is on the right drug. "We’re trying to focus on a high-risk group and see if we can improve some outcomes," he said.

Dr. Nagel reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE ANNUAL INTERSCIENCE CONFERENCE ON ANTIMICROBIAL AGENTS AND CHEMOTHERAPY

Major Finding: An antimicrobial stewardship team identified 26 errors associated with HIV-associated medications in 69 hospitalized patients with HIV over a 9-month period.

Data Source: This was a prospective study using a team for daily evaluation of drug regimens in HIV-infected patients at one institution from March to December 2011.

Disclosures: Dr. Nagel reported having no financial disclosures.

IGRA Tests Top Skin Pricks for TB Screening of Transplant Candidates

SAN FRANCISCO – Interferon-gamma release assay tests appear to be better than tuberculin skin tests for picking up latent TB in solid organ transplant candidates, according to Dr. Shimon Kusne.

It’s not just because of IGRA’s well-known benefits—as a blood test, results are known after one visit so patients don’t need to return for skin spots to be read, and there are no false positives in patients vaccinated against TB or exposed to environmental strains of mycobacterium.

Instead, IGRA tests simply seem to be better at picking up latent TB, Dr. Kusne, professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at the Mayo Clinic Hospital in Phoenix, said at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

He and his colleagues gave 179 kidney, liver, or heart transplant candidates TB skin prick tests and two IGRA tests, the QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube test (QFT-GIT) and the T-Spot test.

QFT-GIT was 2.74 times more likely to be positive than tuberculin purified protein derivative skin tests and T-Spots were 3.10 times more likely to be positive. The findings were statistically significant.

"It may be that IGRA is better in these immune-suppressed hosts. Time will tell," said Dr. Kusne, because these tests are relatively new.

IGRA tests appear to be a fine-toothed comb; positive tests might turn negative the second time around in a small minority of patients. What that means, exactly, still needs to be worked out (Chest 2012;142:55-62). For now, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is okay with hospitals checking for latent TB with either IGRA or skin tests in most cases, he said.

Even so, the Mayo Clinic has moved away from skin tests in transplant candidates. "I think mainly it’s because CDC has said it’s okay to use either and because many [patients] come to get their [skin test] and then disappear," Dr. Kusne said.

"But cost is always a consideration, too. It’s very cheap" to do a skin test, he said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology.

Dr. Kusne said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Interferon-gamma release assay tests appear to be better than tuberculin skin tests for picking up latent TB in solid organ transplant candidates, according to Dr. Shimon Kusne.

It’s not just because of IGRA’s well-known benefits—as a blood test, results are known after one visit so patients don’t need to return for skin spots to be read, and there are no false positives in patients vaccinated against TB or exposed to environmental strains of mycobacterium.

Instead, IGRA tests simply seem to be better at picking up latent TB, Dr. Kusne, professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at the Mayo Clinic Hospital in Phoenix, said at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

He and his colleagues gave 179 kidney, liver, or heart transplant candidates TB skin prick tests and two IGRA tests, the QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube test (QFT-GIT) and the T-Spot test.

QFT-GIT was 2.74 times more likely to be positive than tuberculin purified protein derivative skin tests and T-Spots were 3.10 times more likely to be positive. The findings were statistically significant.

"It may be that IGRA is better in these immune-suppressed hosts. Time will tell," said Dr. Kusne, because these tests are relatively new.

IGRA tests appear to be a fine-toothed comb; positive tests might turn negative the second time around in a small minority of patients. What that means, exactly, still needs to be worked out (Chest 2012;142:55-62). For now, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is okay with hospitals checking for latent TB with either IGRA or skin tests in most cases, he said.

Even so, the Mayo Clinic has moved away from skin tests in transplant candidates. "I think mainly it’s because CDC has said it’s okay to use either and because many [patients] come to get their [skin test] and then disappear," Dr. Kusne said.

"But cost is always a consideration, too. It’s very cheap" to do a skin test, he said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology.

Dr. Kusne said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Interferon-gamma release assay tests appear to be better than tuberculin skin tests for picking up latent TB in solid organ transplant candidates, according to Dr. Shimon Kusne.

It’s not just because of IGRA’s well-known benefits—as a blood test, results are known after one visit so patients don’t need to return for skin spots to be read, and there are no false positives in patients vaccinated against TB or exposed to environmental strains of mycobacterium.

Instead, IGRA tests simply seem to be better at picking up latent TB, Dr. Kusne, professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at the Mayo Clinic Hospital in Phoenix, said at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

He and his colleagues gave 179 kidney, liver, or heart transplant candidates TB skin prick tests and two IGRA tests, the QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube test (QFT-GIT) and the T-Spot test.

QFT-GIT was 2.74 times more likely to be positive than tuberculin purified protein derivative skin tests and T-Spots were 3.10 times more likely to be positive. The findings were statistically significant.

"It may be that IGRA is better in these immune-suppressed hosts. Time will tell," said Dr. Kusne, because these tests are relatively new.

IGRA tests appear to be a fine-toothed comb; positive tests might turn negative the second time around in a small minority of patients. What that means, exactly, still needs to be worked out (Chest 2012;142:55-62). For now, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is okay with hospitals checking for latent TB with either IGRA or skin tests in most cases, he said.

Even so, the Mayo Clinic has moved away from skin tests in transplant candidates. "I think mainly it’s because CDC has said it’s okay to use either and because many [patients] come to get their [skin test] and then disappear," Dr. Kusne said.

"But cost is always a consideration, too. It’s very cheap" to do a skin test, he said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology.

Dr. Kusne said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE ANNUAL INTERSCIENCE CONFERENCE ON ANTIMICROBIAL AGENTS AND CHEMOTHERAPY

Major Finding: Interferon-gamma release assay tests were about three times more likely than skin prick tests to be positive for latent TB.

Data Source: Data are from a prospective study of 179 kidney, liver, or heart transplant candidates.

Disclosures: The lead investigator said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

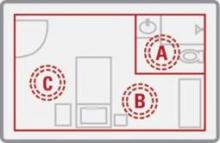

UV Light Beat Bleach for C. difficile Decontamination

SAN FRANCISCO – The M.D. Anderson Cancer Center is abandoning bleach for cleaning hospital rooms exposed to Clostridium difficile in favor of a new machine that kills the organism using ultraviolet light.

The machine reduced C. difficile counts as much as, or more than, bleach cleaning in a preliminary prospective trial in 30 hospital rooms previously occupied by patients infected with C. difficile. The machine is a bit more expensive than bleach at a cost of approximately $82,000 (or $3,000-$4,000 per month to lease), but it avoids damage to materials and the toxic environment for workers caused by the use of bleach or other corrosive chemicals, Dr. Shashank S. Ghantoji said in an interview at a poster presentation at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

Bleach treatment reduced the average number of colony-forming units of C. difficile from 2.39 before cleaning to 0.71, a 70% reduction in the contamination level. Treatment with the Pulsed Xenon UV machine (PX-UV) reduced the average number of colony-forming units from 22.97 to 1.10, a 95% reduction.

The postcleaning contamination levels were not statistically different between the bleach and PX-UV rooms, Dr. Ghantoji and his associates found. However, PX-UV decontamination is faster than using bleach, Dr. Ghantoji said. "It takes at least 45 minutes to clean a room with bleach, and it’s not good for the patients or the health care professionals," plus admissions staff usually are clamoring for the room to be ready as soon as possible, he said. Cleaning a room using the PX-UV method takes perhaps 15 minutes.

The PX-UV machine has been available for some time, but its adoption depends on how proactive hospital infection control teams are, he added. He said he is aware of at least two medical centers beyond M.D. Anderson that are also using the machine.

In the study, 298 samples were taken before and after cleaning from high-touch surfaces – the bathroom handrail, the bed control panel, the bed rail, the top of the bedside table, and the IV pole control panel or other equipment control panel – and analyzed for C. difficile endospores. Fifteen rooms were cleaned by the conventional method using a 1:10 solution of sodium hypochlorite (bleach), and 15 underwent a visual, nonbleach cleaning of surfaces followed by 15 minutes of treatment with the PX-UV.

With the PX-UV method, housekeeping workers clean the bathroom and place the remote-operated PX-UV in the bathroom with the door shut while they finish cleaning the rest of the room. Then the machine is placed on each side of the bed for 4 minutes of operation with workers gone. Sensors stop the machine if any movement is detected.

It works by emitting ultraviolet C light, which kills C. difficile. And here’s a bonus – it also kills vancomycin-resistant enterococci and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Dr. Ghantoji of M.D. Anderson, Houston, said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology.

"The PX-UV method may be a promising alternative to the current standard of decontamination, bleach," he said. Future studies should look at whether the PX-UV method decreases not just endospore counts but transmission of C. difficile, he added.

C. difficile causes more than 300,000 health care–associated infections each year in the United States, incurring $2,500-$3,500 in costs per infection aside from any surgical costs, he estimated. Current guidelines recommend that rooms previously occupied by patients infected with C. difficile be cleaned with a disinfectant registered with the Environmental Protection Agency as effective against the organism.

Xenex Healthcare Services, which markets the PX-UV machine, funded the study, and two of the investigators are employees of the company. Dr. Ghantoji reported having no other relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – The M.D. Anderson Cancer Center is abandoning bleach for cleaning hospital rooms exposed to Clostridium difficile in favor of a new machine that kills the organism using ultraviolet light.

The machine reduced C. difficile counts as much as, or more than, bleach cleaning in a preliminary prospective trial in 30 hospital rooms previously occupied by patients infected with C. difficile. The machine is a bit more expensive than bleach at a cost of approximately $82,000 (or $3,000-$4,000 per month to lease), but it avoids damage to materials and the toxic environment for workers caused by the use of bleach or other corrosive chemicals, Dr. Shashank S. Ghantoji said in an interview at a poster presentation at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

Bleach treatment reduced the average number of colony-forming units of C. difficile from 2.39 before cleaning to 0.71, a 70% reduction in the contamination level. Treatment with the Pulsed Xenon UV machine (PX-UV) reduced the average number of colony-forming units from 22.97 to 1.10, a 95% reduction.

The postcleaning contamination levels were not statistically different between the bleach and PX-UV rooms, Dr. Ghantoji and his associates found. However, PX-UV decontamination is faster than using bleach, Dr. Ghantoji said. "It takes at least 45 minutes to clean a room with bleach, and it’s not good for the patients or the health care professionals," plus admissions staff usually are clamoring for the room to be ready as soon as possible, he said. Cleaning a room using the PX-UV method takes perhaps 15 minutes.

The PX-UV machine has been available for some time, but its adoption depends on how proactive hospital infection control teams are, he added. He said he is aware of at least two medical centers beyond M.D. Anderson that are also using the machine.

In the study, 298 samples were taken before and after cleaning from high-touch surfaces – the bathroom handrail, the bed control panel, the bed rail, the top of the bedside table, and the IV pole control panel or other equipment control panel – and analyzed for C. difficile endospores. Fifteen rooms were cleaned by the conventional method using a 1:10 solution of sodium hypochlorite (bleach), and 15 underwent a visual, nonbleach cleaning of surfaces followed by 15 minutes of treatment with the PX-UV.

With the PX-UV method, housekeeping workers clean the bathroom and place the remote-operated PX-UV in the bathroom with the door shut while they finish cleaning the rest of the room. Then the machine is placed on each side of the bed for 4 minutes of operation with workers gone. Sensors stop the machine if any movement is detected.

It works by emitting ultraviolet C light, which kills C. difficile. And here’s a bonus – it also kills vancomycin-resistant enterococci and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Dr. Ghantoji of M.D. Anderson, Houston, said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology.

"The PX-UV method may be a promising alternative to the current standard of decontamination, bleach," he said. Future studies should look at whether the PX-UV method decreases not just endospore counts but transmission of C. difficile, he added.

C. difficile causes more than 300,000 health care–associated infections each year in the United States, incurring $2,500-$3,500 in costs per infection aside from any surgical costs, he estimated. Current guidelines recommend that rooms previously occupied by patients infected with C. difficile be cleaned with a disinfectant registered with the Environmental Protection Agency as effective against the organism.

Xenex Healthcare Services, which markets the PX-UV machine, funded the study, and two of the investigators are employees of the company. Dr. Ghantoji reported having no other relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – The M.D. Anderson Cancer Center is abandoning bleach for cleaning hospital rooms exposed to Clostridium difficile in favor of a new machine that kills the organism using ultraviolet light.

The machine reduced C. difficile counts as much as, or more than, bleach cleaning in a preliminary prospective trial in 30 hospital rooms previously occupied by patients infected with C. difficile. The machine is a bit more expensive than bleach at a cost of approximately $82,000 (or $3,000-$4,000 per month to lease), but it avoids damage to materials and the toxic environment for workers caused by the use of bleach or other corrosive chemicals, Dr. Shashank S. Ghantoji said in an interview at a poster presentation at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

Bleach treatment reduced the average number of colony-forming units of C. difficile from 2.39 before cleaning to 0.71, a 70% reduction in the contamination level. Treatment with the Pulsed Xenon UV machine (PX-UV) reduced the average number of colony-forming units from 22.97 to 1.10, a 95% reduction.

The postcleaning contamination levels were not statistically different between the bleach and PX-UV rooms, Dr. Ghantoji and his associates found. However, PX-UV decontamination is faster than using bleach, Dr. Ghantoji said. "It takes at least 45 minutes to clean a room with bleach, and it’s not good for the patients or the health care professionals," plus admissions staff usually are clamoring for the room to be ready as soon as possible, he said. Cleaning a room using the PX-UV method takes perhaps 15 minutes.

The PX-UV machine has been available for some time, but its adoption depends on how proactive hospital infection control teams are, he added. He said he is aware of at least two medical centers beyond M.D. Anderson that are also using the machine.

In the study, 298 samples were taken before and after cleaning from high-touch surfaces – the bathroom handrail, the bed control panel, the bed rail, the top of the bedside table, and the IV pole control panel or other equipment control panel – and analyzed for C. difficile endospores. Fifteen rooms were cleaned by the conventional method using a 1:10 solution of sodium hypochlorite (bleach), and 15 underwent a visual, nonbleach cleaning of surfaces followed by 15 minutes of treatment with the PX-UV.

With the PX-UV method, housekeeping workers clean the bathroom and place the remote-operated PX-UV in the bathroom with the door shut while they finish cleaning the rest of the room. Then the machine is placed on each side of the bed for 4 minutes of operation with workers gone. Sensors stop the machine if any movement is detected.

It works by emitting ultraviolet C light, which kills C. difficile. And here’s a bonus – it also kills vancomycin-resistant enterococci and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Dr. Ghantoji of M.D. Anderson, Houston, said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology.

"The PX-UV method may be a promising alternative to the current standard of decontamination, bleach," he said. Future studies should look at whether the PX-UV method decreases not just endospore counts but transmission of C. difficile, he added.

C. difficile causes more than 300,000 health care–associated infections each year in the United States, incurring $2,500-$3,500 in costs per infection aside from any surgical costs, he estimated. Current guidelines recommend that rooms previously occupied by patients infected with C. difficile be cleaned with a disinfectant registered with the Environmental Protection Agency as effective against the organism.

Xenex Healthcare Services, which markets the PX-UV machine, funded the study, and two of the investigators are employees of the company. Dr. Ghantoji reported having no other relevant financial disclosures.

Major Finding: Bleach killed 70% of C. difficile spores in hospital rooms compared with 95% decontamination using nonbleach cleaning plus UV light treatment. The difference between groups was not statistically significant.

Data Source: A prospective comparison was performed of the two cleaning methods in 30 rooms after discharge of patients infected with C. difficile.

Disclosures: Xenex Healthcare Services, which markets the PX-UV machine, funded the study, and two of the investigators are employees of the company. Dr. Ghantoji reported having no other relevant financial disclosures.

E-tests Pick Up Vancomycin Resistance Automated Systems Miss

SAN FRANCISCO – Vancomycin and glycopeptide resistance detection e-tests are better than the automated microbiology systems used in many hospitals when it comes to detecting vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections, according to researcher Meghan Jeffres, Pharm.D

An associate professor of pharmacy practice at Roseman University of Health Sciences in Henderson, Nev., Dr. Jeffres reached her conclusion after testing 63 blood, 115 respiratory, and 29 cystic fibrosis sputum S. aureus isolates for vancomycin susceptibility using all three methods.

She reported that a GRD (glycopeptide resistance detection) e-test vancomycin MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration) of 8 mcg/mL or more, in conjunction with a vancomycin e-test MIC of 4 mcg/mL or less, is diagnostic of heteroresistant vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (hVISA). By itself, a vancomycin e-test MIC of 1.5 mcg/mL or greater is associated with poor outcomes, and suggests the need for an alternative antibiotic, Dr. Jeffres said at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The combined GRD and vancomycin e-tests found 10 hVISA isolates, all respiratory.

Ninety-three (45%) of the isolates, however, had vancomycin e-test MICs of 1.5 mcg/mL or more. Of those 93 isolates that vancomycin e-testing suggested needed a vancomycin alternative, the hospital’s BD Phoenix Automated Microbiology System identified only one as being resistant to vancomycin, with an MIC of 2 mcg/mL; it reported the rest as having vancomycin MICs of 0.5 or 1 mcg/mL, suggesting susceptibility to vancomycin.

"Our automated system accurately identified one out of 93 isolates" as needing something other than vancomycin, she said. "As a clinician, when your isolates are 1 and 0.5, you treat it as a susceptible isolate." Ultimately, if those results come from automated testing, "it’s a false sense of security. None of the [automated testing systems] are very good at reporting vancomycin MICs," Dr. Jeffres said.

Because of that, many larger academic institutions have moved to e-testing, but other hospitals – such as the large community hospital in Las Vegas where Dr. Jeffres did her research – still rely heavily on automated vancomycin resistance testing.

That can have serious consequences. Dr. Jeffres’ e-test results were not reported in patients’ medical records, so clinicians at the hospital used the automated results to help make treatment decisions. All 10 of the hVISA isolates reported out of automated testing had vancomycin MICs of 0.5 or 1 mcg/mL, indicating vancomycin susceptibility.

Three of those patients were treated with vancomycin; they died. The rest were treated with linezolid – a vancomycin alternative – probably based on clinical hunches. Those patients lived, and were able to be sent home or to rehab.

"There is no statistical analysis" here, "but you can’t help but to at least pause," given the results. Had even the [vancomycin] e-test alone been done by clinicians, "there’s no way" the three patients would have gotten vancomycin, Dr. Jeffres said.

E-testing adds a bit to the cost of assessing vancomycin resistance; the GRD e-test costs about $5.39, the vancomycin e-test about $2.90, and the necessary blood agar about 79 cents. Alternative antibiotics are more expensive than vancomycin, as well.

"However, dead people cost way more, from both economic and humanistic points of view," she said. E-testing will increase a hospital’s pharmacy budget, especially if it leads to alternative antibiotics, but overall, the hospital budget should stay the same if not decrease, Dr. Jeffres said.

The conference was sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology. Dr. Jeffres disclosed research funding from Pfizer, the maker of linezolid.

SAN FRANCISCO – Vancomycin and glycopeptide resistance detection e-tests are better than the automated microbiology systems used in many hospitals when it comes to detecting vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections, according to researcher Meghan Jeffres, Pharm.D

An associate professor of pharmacy practice at Roseman University of Health Sciences in Henderson, Nev., Dr. Jeffres reached her conclusion after testing 63 blood, 115 respiratory, and 29 cystic fibrosis sputum S. aureus isolates for vancomycin susceptibility using all three methods.

She reported that a GRD (glycopeptide resistance detection) e-test vancomycin MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration) of 8 mcg/mL or more, in conjunction with a vancomycin e-test MIC of 4 mcg/mL or less, is diagnostic of heteroresistant vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (hVISA). By itself, a vancomycin e-test MIC of 1.5 mcg/mL or greater is associated with poor outcomes, and suggests the need for an alternative antibiotic, Dr. Jeffres said at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The combined GRD and vancomycin e-tests found 10 hVISA isolates, all respiratory.

Ninety-three (45%) of the isolates, however, had vancomycin e-test MICs of 1.5 mcg/mL or more. Of those 93 isolates that vancomycin e-testing suggested needed a vancomycin alternative, the hospital’s BD Phoenix Automated Microbiology System identified only one as being resistant to vancomycin, with an MIC of 2 mcg/mL; it reported the rest as having vancomycin MICs of 0.5 or 1 mcg/mL, suggesting susceptibility to vancomycin.

"Our automated system accurately identified one out of 93 isolates" as needing something other than vancomycin, she said. "As a clinician, when your isolates are 1 and 0.5, you treat it as a susceptible isolate." Ultimately, if those results come from automated testing, "it’s a false sense of security. None of the [automated testing systems] are very good at reporting vancomycin MICs," Dr. Jeffres said.

Because of that, many larger academic institutions have moved to e-testing, but other hospitals – such as the large community hospital in Las Vegas where Dr. Jeffres did her research – still rely heavily on automated vancomycin resistance testing.

That can have serious consequences. Dr. Jeffres’ e-test results were not reported in patients’ medical records, so clinicians at the hospital used the automated results to help make treatment decisions. All 10 of the hVISA isolates reported out of automated testing had vancomycin MICs of 0.5 or 1 mcg/mL, indicating vancomycin susceptibility.

Three of those patients were treated with vancomycin; they died. The rest were treated with linezolid – a vancomycin alternative – probably based on clinical hunches. Those patients lived, and were able to be sent home or to rehab.

"There is no statistical analysis" here, "but you can’t help but to at least pause," given the results. Had even the [vancomycin] e-test alone been done by clinicians, "there’s no way" the three patients would have gotten vancomycin, Dr. Jeffres said.

E-testing adds a bit to the cost of assessing vancomycin resistance; the GRD e-test costs about $5.39, the vancomycin e-test about $2.90, and the necessary blood agar about 79 cents. Alternative antibiotics are more expensive than vancomycin, as well.

"However, dead people cost way more, from both economic and humanistic points of view," she said. E-testing will increase a hospital’s pharmacy budget, especially if it leads to alternative antibiotics, but overall, the hospital budget should stay the same if not decrease, Dr. Jeffres said.

The conference was sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology. Dr. Jeffres disclosed research funding from Pfizer, the maker of linezolid.