User login

Preparing for pancreatic cancer ‘tsunami’ ahead

ORLANDO – Overall cancer death rates are dropping dramatically, but pancreatic cancer mortality remains high.

“By 2020 we expect [pancreatic cancer] to be the second most common cause of cancer-related death, exceeded only by lung cancer, and if lung cancer deaths continue to fall – which we expect that they will – it will be the most common cause of cancer-related death,” Margaret A. Tempero, MD, said at the annual conference of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

Further, as the population ages there will be an increasing number of patients presenting with pancreatic cancer, said Dr. Tempero of the University of California, San Francisco.

Currently, 80% of pancreatic cancer patients are diagnosed with disease that is not amenable to resection, and 80% of those who have resection and adjuvant therapy experience relapse. The overall survival rate is only about 9%.

“This is really, really an aggressive malignancy,” Dr. Tempero said, noting that the survival among those with metastases who do not receive treatment is only about 3 months.

There are no early symptoms that direct attention to the pancreas. Additionally, some patients experience very early invasion and metastases; in fact, up to two-thirds of patients with lesions only 1 cm in size will already have lymph node metastasis, she said.

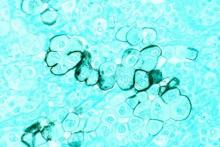

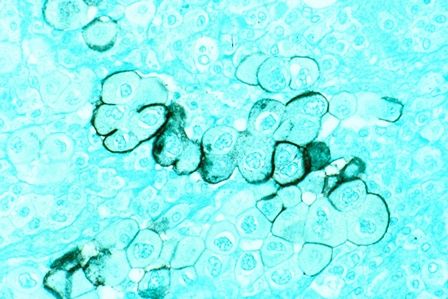

The disease tends to be chemoresistant, although this may be changing with treatment advances, but it is characterized by “a lot of desmoplastic stroma, so there’s a lot of microenvironment that’s perturbed around the malignancy,” making it difficult for drugs to permeate the stroma.

“That’s something we’re actively working on – ways that we can actually change the stroma so that we can get more drug into the cancer,” she said.

Another challenge is the disease’s “habit of elaborating a lot of cytokines that disable the person with the disease,” which can lead to frailty that makes it difficult to deliver potentially effective therapies that are well tolerated in patients with other types of cancer, she noted.

An important question is whether pancreatic cancer is diagnosed too late or metastasizes too early, and there is evidence to support both possibilities.

“Either way ... we need to work on better treatment,” she said.

Resectable/borderline resectable disease

One noteworthy recent advance for patients with resectable/borderline resectable disease is the addition of capecitabine to gemcitabine for adjuvant therapy. In the ESPAC 4 study published in March in the Lancet, the combination of gemcitabine and capecitabine showed a clear benefit over gemcitabine alone.

“So that has now entered [the NCCN] guidelines as an important option for adjuvant therapy,” said Dr. Tempero, chair of the NCCN pancreatic cancer guidelines panel.

Ongoing trials are also looking at the FOLFIRINOX (irinotecan plus 5-fluorouracil plus leucovorin plus oxaliplatin) and gemcitabine/nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel (nab-P) regimens in the adjuvant setting. These have previously shown some efficacy in the metastatic setting.

“So we really wanted to get these therapies into the adjuvant setting as soon as we could,” she said.

In the ACCORD trial, FOLFIRINOX is being compared with gemcitabine in the postoperative adjuvant setting, and the APACT trial comparing gemcitabine/nab-P to gemcitabine monotherapy completed accrual last year.

“I’m pretty sure that we’ll have enough events on the APACT study by the end of this year, and hopefully we can present that data in the spring. I’m hoping it will be a positive trial for us,” she said.

Neoadjuvant therapy – a successful strategy used in many other malignancies – is also being looked at for pancreatic cancer.

A pilot study (A021101) completed last year suggested that chemotherapy (FOLFIRINOX for 2 months) and chemoradiation (capecitabine and radiation at 50.4 Gy) followed by surgical resection and adjuvant chemotherapy (gemcitabine for 2 months) provided some benefit in patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. This trial led to another ongoing study (S1505) in which patients with borderline resectable disease will be treated with 4 months of FOLFIRINOX prior to resection, followed by chemoradiation and surgery or FOLFIRINOX and surgery, and patients with resectable disease will undergo resection followed by FOLFIRINOX and surgery or gemcitabine/nab-P and surgery.

“The goal is not to compare the two regimens; the goal is to identify the benchmarks that we get with these regimens. In other words, if you’re going to give FOLFIRINOX, what pathologic complete response rate can you expect? What will your R1 resection rate be? With gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel, the same thing, because if you want to continue to build on these regimens in the neoadjuvant setting you need to know what you’re likely to get so you can make clinical trial assumptions when you add new drugs.

“Once we have these benchmarking data we can really sail in the neoadjuvant setting. It’s a great window-of-opportunity setting for new drugs, because you’re getting serial tissue,” Dr. Tempero said, explaining that in addition to resection of tissue, there is opportunity to get biopsies ahead of time and look at the effects of the drug.

Locally advanced disease

For locally advanced disease, studies have failed to show a benefit of adding radiation after chemotherapy, but radiation oncologists who argue that, “when your therapy gets better, my therapy gets better,” have a valid point, Dr. Tempero said.

For that reason, the Radiation Therapy Oncology group launched a trial to look at gemcitabine/nab-P with and without radiation, but had difficulty with enrollment due to resistance among some physicians who are opposed to radiation in this setting .

“So I don’t know that we will ever answer this question in locally advanced disease. What I can say ... is, in my mind, in locally advanced disease, the most important component is the chemotherapy,” she said.

Metastatic disease

When it comes to trials involving pancreatic cancer patients with metastatic disease, it is important to understand – and to convey to policymakers – that the goal is not only to provide better care in these patients who are at the end of their life, but also to identify strategies that can be used in the adjuvant and neoadjuvant settings, as this is part of the “overall mission of helping patients to feel better and live longer and be cured,” Dr. Tempero said.

One regimen currently used in the metastatic setting is FOLFIRINOX, which was shown in the Prodige 4-ACCORD 11 trial to be superior to gemcitabine monotherapy for survival (hazard ratio, 0.57).

“This is the first time we ever saw a hazard ratio below 0.6 in this disease,” she said, adding that for some patients this means “they can get tremendous benefit, they can come off chemotherapy and have a chemotherapy holiday,” she said.

That said, it’s a tough regimen, she added, explaining that it has dominating toxicities of myelosuppression, diarrhea, and neuropathy that can be irreversible.

Frail patients may not be able to tolerate the regimen, but modifications to the regimen may help. For example, the 5-fluorourasil bolus is often omitted, and doses are sometimes reduced. Chemotherapy holidays can also be of benefit.

Another regimen for the metastatic setting involves the use of nab-P plus gemcitabine, which was shown in a phase III trial to improve survival (HR for death, 0.72).

The results aren’t quite as dramatic as those seen with FOLFIRINOX, but the regimen is slightly easier to manage, Dr. Tempero said, adding: “It’s still not a walk in the park.”

Myelosuppression, arthralgias, and neuropathy still occur, she explained.

Gemcitabine/capecitabine, which has been shown to improve progression-free survival, can also be used, and may be preferable in elderly patients who aren’t fit enough for the other regimens, she said.

“When I select treatment, I really sit down with the patient, and I look at their comorbidities and let them review the toxicities. They decide,” she said, explaining that she provides recommendations based on their concerns and input. “We do have a conversation and we talk about the goals of treatment, we talk about the toxicities.”

Future efforts for metastatic disease should build upon both FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine/nab-P, she said.

However, because of the difficulty with administering FOLFIRINOX, only two of the 54 open phase I-III trials ongoing in the United States for metastatic disease incorporate the regimen.

Other treatment options include gemcitabine/cisplatin, GTX (gemcitabine/docetaxel/capecitabine), and gemcitabine/erlotinib. The former remains in the NCCN guidelines, primarily for those with hereditary forms of pancreatic cancer, and in particular for those in the DNA repair pathway (BRCA patients, for example).

“We actually have trials now focusing on just BRCA-related pancreatic cancer,” she said, noting that these patients are “exquisitely sensitive to cisplatin and don’t need a harsh regimen like FOLFIRINOX to get the same benefit.

GTX is a very active regimen, although it has never been compared with gemcitabine monotherapy in a randomized trial. However, because of its clear activity it remains in the NCCN guidelines as an option.

Gemcitabine/erlotinib also remains in the guidelines because of a tiny trial that showed a small benefit, but it is not a preferred combination, she said.

Future therapies

Efforts going forward are focusing on finding drugs that inactivate activated RAS, which is “a really big driver” in many cancers, as well as on addressing the microenvironment (such as the desmoplastic stroma that may help encourage invasion of metastases and/or impede drug delivery to the cancer), Dr. Tempero said.

“So there is a lot of interest right now in various forms of immunotherapy or in stromal remodeling so we can see what impact that has on the progression of this disease,” she said, noting that new agents in registration trials include ibrutinib, laparib, PEGPH20, and insulinlike growth factor 1 (IGF-1) inhibitors, and those in planning stages include chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 2 (CCR2) inhibitors and palbociclib.

“And I think we have opportunities in the maintenance setting and in the neoadjuvant setting to do window-of-opportunity trials where we can test new concepts, where we can get pharmacodynamic and biologic data to understand what these new agents are doing,” she said.

Collaborative effort to identify patients at risk

Population-level screening strategies for pancreatic cancer aren’t feasible because of the relatively low incidence of the disease, but efforts are underway to identify and screen high-risk groups.

“We actually have some tests that you could screen with, but they’re not perfect, and with a disease that occurs at the rate that [pancreatic cancer] does, you can’t screen the whole population, because you will find false positives, and you will cause unnecessary procedures more than you’ll find the cancer, Dr. Tempero said during a meeting with press at the NCCN annual conference.

Instead, it is important to identify and screen only those at high risk, she added.

Such a group might include patients with new-onset diabetes who experience weight loss.

New-onset diabetes can be caused by pancreatic cancer, and weight loss with diabetes is unexpected and should raise a red flag, Dr. Temepero explained, adding that an education gap among community physicians means these patients are sometimes cheered for the weight loss instead – and then they end up in the pancreatic disease clinic with metastatic disease 2 years later.

In an effort to better define and characterize this and other high-risk groups, the National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Cancer Institute are working together to fund a network of institutions that will develop high-risk cohorts and begin deploying screening strategies. The effort is partly in response to the Recalcitrant Cancer Act passed in 2012 to “force more attention on funding pancreatic cancer research through the branches of the NIH,” she explained.

In this particular high-risk group, the institutions will look at the character of diabetes and the clinical correlates with pancreatic cancer.

“Once we hone in on these, we can use those – what we hope are – early-detection biomarkers, and if those are positive, then we would ask the patient to have a CT scan to look for pancreatic cancer,” she said.

Dr. Tempero reported serving as a scientific advisor and/or receiving grant/research support, consulting fees, and/or honoraria from Celgene Corporation, Champion Oncology, Cornerstone Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, EMD Serono, Gilead Sciences, Halozyme Therapeutics, MCS Biotech Resources, NeoHealth, Novocure, Opsona Therapeutics, Pfizer, Portola Pharmaceuticals, and Threshold Pharmaceuticals.

ORLANDO – Overall cancer death rates are dropping dramatically, but pancreatic cancer mortality remains high.

“By 2020 we expect [pancreatic cancer] to be the second most common cause of cancer-related death, exceeded only by lung cancer, and if lung cancer deaths continue to fall – which we expect that they will – it will be the most common cause of cancer-related death,” Margaret A. Tempero, MD, said at the annual conference of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

Further, as the population ages there will be an increasing number of patients presenting with pancreatic cancer, said Dr. Tempero of the University of California, San Francisco.

Currently, 80% of pancreatic cancer patients are diagnosed with disease that is not amenable to resection, and 80% of those who have resection and adjuvant therapy experience relapse. The overall survival rate is only about 9%.

“This is really, really an aggressive malignancy,” Dr. Tempero said, noting that the survival among those with metastases who do not receive treatment is only about 3 months.

There are no early symptoms that direct attention to the pancreas. Additionally, some patients experience very early invasion and metastases; in fact, up to two-thirds of patients with lesions only 1 cm in size will already have lymph node metastasis, she said.

The disease tends to be chemoresistant, although this may be changing with treatment advances, but it is characterized by “a lot of desmoplastic stroma, so there’s a lot of microenvironment that’s perturbed around the malignancy,” making it difficult for drugs to permeate the stroma.

“That’s something we’re actively working on – ways that we can actually change the stroma so that we can get more drug into the cancer,” she said.

Another challenge is the disease’s “habit of elaborating a lot of cytokines that disable the person with the disease,” which can lead to frailty that makes it difficult to deliver potentially effective therapies that are well tolerated in patients with other types of cancer, she noted.

An important question is whether pancreatic cancer is diagnosed too late or metastasizes too early, and there is evidence to support both possibilities.

“Either way ... we need to work on better treatment,” she said.

Resectable/borderline resectable disease

One noteworthy recent advance for patients with resectable/borderline resectable disease is the addition of capecitabine to gemcitabine for adjuvant therapy. In the ESPAC 4 study published in March in the Lancet, the combination of gemcitabine and capecitabine showed a clear benefit over gemcitabine alone.

“So that has now entered [the NCCN] guidelines as an important option for adjuvant therapy,” said Dr. Tempero, chair of the NCCN pancreatic cancer guidelines panel.

Ongoing trials are also looking at the FOLFIRINOX (irinotecan plus 5-fluorouracil plus leucovorin plus oxaliplatin) and gemcitabine/nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel (nab-P) regimens in the adjuvant setting. These have previously shown some efficacy in the metastatic setting.

“So we really wanted to get these therapies into the adjuvant setting as soon as we could,” she said.

In the ACCORD trial, FOLFIRINOX is being compared with gemcitabine in the postoperative adjuvant setting, and the APACT trial comparing gemcitabine/nab-P to gemcitabine monotherapy completed accrual last year.

“I’m pretty sure that we’ll have enough events on the APACT study by the end of this year, and hopefully we can present that data in the spring. I’m hoping it will be a positive trial for us,” she said.

Neoadjuvant therapy – a successful strategy used in many other malignancies – is also being looked at for pancreatic cancer.

A pilot study (A021101) completed last year suggested that chemotherapy (FOLFIRINOX for 2 months) and chemoradiation (capecitabine and radiation at 50.4 Gy) followed by surgical resection and adjuvant chemotherapy (gemcitabine for 2 months) provided some benefit in patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. This trial led to another ongoing study (S1505) in which patients with borderline resectable disease will be treated with 4 months of FOLFIRINOX prior to resection, followed by chemoradiation and surgery or FOLFIRINOX and surgery, and patients with resectable disease will undergo resection followed by FOLFIRINOX and surgery or gemcitabine/nab-P and surgery.

“The goal is not to compare the two regimens; the goal is to identify the benchmarks that we get with these regimens. In other words, if you’re going to give FOLFIRINOX, what pathologic complete response rate can you expect? What will your R1 resection rate be? With gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel, the same thing, because if you want to continue to build on these regimens in the neoadjuvant setting you need to know what you’re likely to get so you can make clinical trial assumptions when you add new drugs.

“Once we have these benchmarking data we can really sail in the neoadjuvant setting. It’s a great window-of-opportunity setting for new drugs, because you’re getting serial tissue,” Dr. Tempero said, explaining that in addition to resection of tissue, there is opportunity to get biopsies ahead of time and look at the effects of the drug.

Locally advanced disease

For locally advanced disease, studies have failed to show a benefit of adding radiation after chemotherapy, but radiation oncologists who argue that, “when your therapy gets better, my therapy gets better,” have a valid point, Dr. Tempero said.

For that reason, the Radiation Therapy Oncology group launched a trial to look at gemcitabine/nab-P with and without radiation, but had difficulty with enrollment due to resistance among some physicians who are opposed to radiation in this setting .

“So I don’t know that we will ever answer this question in locally advanced disease. What I can say ... is, in my mind, in locally advanced disease, the most important component is the chemotherapy,” she said.

Metastatic disease

When it comes to trials involving pancreatic cancer patients with metastatic disease, it is important to understand – and to convey to policymakers – that the goal is not only to provide better care in these patients who are at the end of their life, but also to identify strategies that can be used in the adjuvant and neoadjuvant settings, as this is part of the “overall mission of helping patients to feel better and live longer and be cured,” Dr. Tempero said.

One regimen currently used in the metastatic setting is FOLFIRINOX, which was shown in the Prodige 4-ACCORD 11 trial to be superior to gemcitabine monotherapy for survival (hazard ratio, 0.57).

“This is the first time we ever saw a hazard ratio below 0.6 in this disease,” she said, adding that for some patients this means “they can get tremendous benefit, they can come off chemotherapy and have a chemotherapy holiday,” she said.

That said, it’s a tough regimen, she added, explaining that it has dominating toxicities of myelosuppression, diarrhea, and neuropathy that can be irreversible.

Frail patients may not be able to tolerate the regimen, but modifications to the regimen may help. For example, the 5-fluorourasil bolus is often omitted, and doses are sometimes reduced. Chemotherapy holidays can also be of benefit.

Another regimen for the metastatic setting involves the use of nab-P plus gemcitabine, which was shown in a phase III trial to improve survival (HR for death, 0.72).

The results aren’t quite as dramatic as those seen with FOLFIRINOX, but the regimen is slightly easier to manage, Dr. Tempero said, adding: “It’s still not a walk in the park.”

Myelosuppression, arthralgias, and neuropathy still occur, she explained.

Gemcitabine/capecitabine, which has been shown to improve progression-free survival, can also be used, and may be preferable in elderly patients who aren’t fit enough for the other regimens, she said.

“When I select treatment, I really sit down with the patient, and I look at their comorbidities and let them review the toxicities. They decide,” she said, explaining that she provides recommendations based on their concerns and input. “We do have a conversation and we talk about the goals of treatment, we talk about the toxicities.”

Future efforts for metastatic disease should build upon both FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine/nab-P, she said.

However, because of the difficulty with administering FOLFIRINOX, only two of the 54 open phase I-III trials ongoing in the United States for metastatic disease incorporate the regimen.

Other treatment options include gemcitabine/cisplatin, GTX (gemcitabine/docetaxel/capecitabine), and gemcitabine/erlotinib. The former remains in the NCCN guidelines, primarily for those with hereditary forms of pancreatic cancer, and in particular for those in the DNA repair pathway (BRCA patients, for example).

“We actually have trials now focusing on just BRCA-related pancreatic cancer,” she said, noting that these patients are “exquisitely sensitive to cisplatin and don’t need a harsh regimen like FOLFIRINOX to get the same benefit.

GTX is a very active regimen, although it has never been compared with gemcitabine monotherapy in a randomized trial. However, because of its clear activity it remains in the NCCN guidelines as an option.

Gemcitabine/erlotinib also remains in the guidelines because of a tiny trial that showed a small benefit, but it is not a preferred combination, she said.

Future therapies

Efforts going forward are focusing on finding drugs that inactivate activated RAS, which is “a really big driver” in many cancers, as well as on addressing the microenvironment (such as the desmoplastic stroma that may help encourage invasion of metastases and/or impede drug delivery to the cancer), Dr. Tempero said.

“So there is a lot of interest right now in various forms of immunotherapy or in stromal remodeling so we can see what impact that has on the progression of this disease,” she said, noting that new agents in registration trials include ibrutinib, laparib, PEGPH20, and insulinlike growth factor 1 (IGF-1) inhibitors, and those in planning stages include chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 2 (CCR2) inhibitors and palbociclib.

“And I think we have opportunities in the maintenance setting and in the neoadjuvant setting to do window-of-opportunity trials where we can test new concepts, where we can get pharmacodynamic and biologic data to understand what these new agents are doing,” she said.

Collaborative effort to identify patients at risk

Population-level screening strategies for pancreatic cancer aren’t feasible because of the relatively low incidence of the disease, but efforts are underway to identify and screen high-risk groups.

“We actually have some tests that you could screen with, but they’re not perfect, and with a disease that occurs at the rate that [pancreatic cancer] does, you can’t screen the whole population, because you will find false positives, and you will cause unnecessary procedures more than you’ll find the cancer, Dr. Tempero said during a meeting with press at the NCCN annual conference.

Instead, it is important to identify and screen only those at high risk, she added.

Such a group might include patients with new-onset diabetes who experience weight loss.

New-onset diabetes can be caused by pancreatic cancer, and weight loss with diabetes is unexpected and should raise a red flag, Dr. Temepero explained, adding that an education gap among community physicians means these patients are sometimes cheered for the weight loss instead – and then they end up in the pancreatic disease clinic with metastatic disease 2 years later.

In an effort to better define and characterize this and other high-risk groups, the National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Cancer Institute are working together to fund a network of institutions that will develop high-risk cohorts and begin deploying screening strategies. The effort is partly in response to the Recalcitrant Cancer Act passed in 2012 to “force more attention on funding pancreatic cancer research through the branches of the NIH,” she explained.

In this particular high-risk group, the institutions will look at the character of diabetes and the clinical correlates with pancreatic cancer.

“Once we hone in on these, we can use those – what we hope are – early-detection biomarkers, and if those are positive, then we would ask the patient to have a CT scan to look for pancreatic cancer,” she said.

Dr. Tempero reported serving as a scientific advisor and/or receiving grant/research support, consulting fees, and/or honoraria from Celgene Corporation, Champion Oncology, Cornerstone Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, EMD Serono, Gilead Sciences, Halozyme Therapeutics, MCS Biotech Resources, NeoHealth, Novocure, Opsona Therapeutics, Pfizer, Portola Pharmaceuticals, and Threshold Pharmaceuticals.

ORLANDO – Overall cancer death rates are dropping dramatically, but pancreatic cancer mortality remains high.

“By 2020 we expect [pancreatic cancer] to be the second most common cause of cancer-related death, exceeded only by lung cancer, and if lung cancer deaths continue to fall – which we expect that they will – it will be the most common cause of cancer-related death,” Margaret A. Tempero, MD, said at the annual conference of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

Further, as the population ages there will be an increasing number of patients presenting with pancreatic cancer, said Dr. Tempero of the University of California, San Francisco.

Currently, 80% of pancreatic cancer patients are diagnosed with disease that is not amenable to resection, and 80% of those who have resection and adjuvant therapy experience relapse. The overall survival rate is only about 9%.

“This is really, really an aggressive malignancy,” Dr. Tempero said, noting that the survival among those with metastases who do not receive treatment is only about 3 months.

There are no early symptoms that direct attention to the pancreas. Additionally, some patients experience very early invasion and metastases; in fact, up to two-thirds of patients with lesions only 1 cm in size will already have lymph node metastasis, she said.

The disease tends to be chemoresistant, although this may be changing with treatment advances, but it is characterized by “a lot of desmoplastic stroma, so there’s a lot of microenvironment that’s perturbed around the malignancy,” making it difficult for drugs to permeate the stroma.

“That’s something we’re actively working on – ways that we can actually change the stroma so that we can get more drug into the cancer,” she said.

Another challenge is the disease’s “habit of elaborating a lot of cytokines that disable the person with the disease,” which can lead to frailty that makes it difficult to deliver potentially effective therapies that are well tolerated in patients with other types of cancer, she noted.

An important question is whether pancreatic cancer is diagnosed too late or metastasizes too early, and there is evidence to support both possibilities.

“Either way ... we need to work on better treatment,” she said.

Resectable/borderline resectable disease

One noteworthy recent advance for patients with resectable/borderline resectable disease is the addition of capecitabine to gemcitabine for adjuvant therapy. In the ESPAC 4 study published in March in the Lancet, the combination of gemcitabine and capecitabine showed a clear benefit over gemcitabine alone.

“So that has now entered [the NCCN] guidelines as an important option for adjuvant therapy,” said Dr. Tempero, chair of the NCCN pancreatic cancer guidelines panel.

Ongoing trials are also looking at the FOLFIRINOX (irinotecan plus 5-fluorouracil plus leucovorin plus oxaliplatin) and gemcitabine/nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel (nab-P) regimens in the adjuvant setting. These have previously shown some efficacy in the metastatic setting.

“So we really wanted to get these therapies into the adjuvant setting as soon as we could,” she said.

In the ACCORD trial, FOLFIRINOX is being compared with gemcitabine in the postoperative adjuvant setting, and the APACT trial comparing gemcitabine/nab-P to gemcitabine monotherapy completed accrual last year.

“I’m pretty sure that we’ll have enough events on the APACT study by the end of this year, and hopefully we can present that data in the spring. I’m hoping it will be a positive trial for us,” she said.

Neoadjuvant therapy – a successful strategy used in many other malignancies – is also being looked at for pancreatic cancer.

A pilot study (A021101) completed last year suggested that chemotherapy (FOLFIRINOX for 2 months) and chemoradiation (capecitabine and radiation at 50.4 Gy) followed by surgical resection and adjuvant chemotherapy (gemcitabine for 2 months) provided some benefit in patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. This trial led to another ongoing study (S1505) in which patients with borderline resectable disease will be treated with 4 months of FOLFIRINOX prior to resection, followed by chemoradiation and surgery or FOLFIRINOX and surgery, and patients with resectable disease will undergo resection followed by FOLFIRINOX and surgery or gemcitabine/nab-P and surgery.

“The goal is not to compare the two regimens; the goal is to identify the benchmarks that we get with these regimens. In other words, if you’re going to give FOLFIRINOX, what pathologic complete response rate can you expect? What will your R1 resection rate be? With gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel, the same thing, because if you want to continue to build on these regimens in the neoadjuvant setting you need to know what you’re likely to get so you can make clinical trial assumptions when you add new drugs.

“Once we have these benchmarking data we can really sail in the neoadjuvant setting. It’s a great window-of-opportunity setting for new drugs, because you’re getting serial tissue,” Dr. Tempero said, explaining that in addition to resection of tissue, there is opportunity to get biopsies ahead of time and look at the effects of the drug.

Locally advanced disease

For locally advanced disease, studies have failed to show a benefit of adding radiation after chemotherapy, but radiation oncologists who argue that, “when your therapy gets better, my therapy gets better,” have a valid point, Dr. Tempero said.

For that reason, the Radiation Therapy Oncology group launched a trial to look at gemcitabine/nab-P with and without radiation, but had difficulty with enrollment due to resistance among some physicians who are opposed to radiation in this setting .

“So I don’t know that we will ever answer this question in locally advanced disease. What I can say ... is, in my mind, in locally advanced disease, the most important component is the chemotherapy,” she said.

Metastatic disease

When it comes to trials involving pancreatic cancer patients with metastatic disease, it is important to understand – and to convey to policymakers – that the goal is not only to provide better care in these patients who are at the end of their life, but also to identify strategies that can be used in the adjuvant and neoadjuvant settings, as this is part of the “overall mission of helping patients to feel better and live longer and be cured,” Dr. Tempero said.

One regimen currently used in the metastatic setting is FOLFIRINOX, which was shown in the Prodige 4-ACCORD 11 trial to be superior to gemcitabine monotherapy for survival (hazard ratio, 0.57).

“This is the first time we ever saw a hazard ratio below 0.6 in this disease,” she said, adding that for some patients this means “they can get tremendous benefit, they can come off chemotherapy and have a chemotherapy holiday,” she said.

That said, it’s a tough regimen, she added, explaining that it has dominating toxicities of myelosuppression, diarrhea, and neuropathy that can be irreversible.

Frail patients may not be able to tolerate the regimen, but modifications to the regimen may help. For example, the 5-fluorourasil bolus is often omitted, and doses are sometimes reduced. Chemotherapy holidays can also be of benefit.

Another regimen for the metastatic setting involves the use of nab-P plus gemcitabine, which was shown in a phase III trial to improve survival (HR for death, 0.72).

The results aren’t quite as dramatic as those seen with FOLFIRINOX, but the regimen is slightly easier to manage, Dr. Tempero said, adding: “It’s still not a walk in the park.”

Myelosuppression, arthralgias, and neuropathy still occur, she explained.

Gemcitabine/capecitabine, which has been shown to improve progression-free survival, can also be used, and may be preferable in elderly patients who aren’t fit enough for the other regimens, she said.

“When I select treatment, I really sit down with the patient, and I look at their comorbidities and let them review the toxicities. They decide,” she said, explaining that she provides recommendations based on their concerns and input. “We do have a conversation and we talk about the goals of treatment, we talk about the toxicities.”

Future efforts for metastatic disease should build upon both FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine/nab-P, she said.

However, because of the difficulty with administering FOLFIRINOX, only two of the 54 open phase I-III trials ongoing in the United States for metastatic disease incorporate the regimen.

Other treatment options include gemcitabine/cisplatin, GTX (gemcitabine/docetaxel/capecitabine), and gemcitabine/erlotinib. The former remains in the NCCN guidelines, primarily for those with hereditary forms of pancreatic cancer, and in particular for those in the DNA repair pathway (BRCA patients, for example).

“We actually have trials now focusing on just BRCA-related pancreatic cancer,” she said, noting that these patients are “exquisitely sensitive to cisplatin and don’t need a harsh regimen like FOLFIRINOX to get the same benefit.

GTX is a very active regimen, although it has never been compared with gemcitabine monotherapy in a randomized trial. However, because of its clear activity it remains in the NCCN guidelines as an option.

Gemcitabine/erlotinib also remains in the guidelines because of a tiny trial that showed a small benefit, but it is not a preferred combination, she said.

Future therapies

Efforts going forward are focusing on finding drugs that inactivate activated RAS, which is “a really big driver” in many cancers, as well as on addressing the microenvironment (such as the desmoplastic stroma that may help encourage invasion of metastases and/or impede drug delivery to the cancer), Dr. Tempero said.

“So there is a lot of interest right now in various forms of immunotherapy or in stromal remodeling so we can see what impact that has on the progression of this disease,” she said, noting that new agents in registration trials include ibrutinib, laparib, PEGPH20, and insulinlike growth factor 1 (IGF-1) inhibitors, and those in planning stages include chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 2 (CCR2) inhibitors and palbociclib.

“And I think we have opportunities in the maintenance setting and in the neoadjuvant setting to do window-of-opportunity trials where we can test new concepts, where we can get pharmacodynamic and biologic data to understand what these new agents are doing,” she said.

Collaborative effort to identify patients at risk

Population-level screening strategies for pancreatic cancer aren’t feasible because of the relatively low incidence of the disease, but efforts are underway to identify and screen high-risk groups.

“We actually have some tests that you could screen with, but they’re not perfect, and with a disease that occurs at the rate that [pancreatic cancer] does, you can’t screen the whole population, because you will find false positives, and you will cause unnecessary procedures more than you’ll find the cancer, Dr. Tempero said during a meeting with press at the NCCN annual conference.

Instead, it is important to identify and screen only those at high risk, she added.

Such a group might include patients with new-onset diabetes who experience weight loss.

New-onset diabetes can be caused by pancreatic cancer, and weight loss with diabetes is unexpected and should raise a red flag, Dr. Temepero explained, adding that an education gap among community physicians means these patients are sometimes cheered for the weight loss instead – and then they end up in the pancreatic disease clinic with metastatic disease 2 years later.

In an effort to better define and characterize this and other high-risk groups, the National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Cancer Institute are working together to fund a network of institutions that will develop high-risk cohorts and begin deploying screening strategies. The effort is partly in response to the Recalcitrant Cancer Act passed in 2012 to “force more attention on funding pancreatic cancer research through the branches of the NIH,” she explained.

In this particular high-risk group, the institutions will look at the character of diabetes and the clinical correlates with pancreatic cancer.

“Once we hone in on these, we can use those – what we hope are – early-detection biomarkers, and if those are positive, then we would ask the patient to have a CT scan to look for pancreatic cancer,” she said.

Dr. Tempero reported serving as a scientific advisor and/or receiving grant/research support, consulting fees, and/or honoraria from Celgene Corporation, Champion Oncology, Cornerstone Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, EMD Serono, Gilead Sciences, Halozyme Therapeutics, MCS Biotech Resources, NeoHealth, Novocure, Opsona Therapeutics, Pfizer, Portola Pharmaceuticals, and Threshold Pharmaceuticals.

AT THE NCCN ANNUAL CONFERENCE

Key clinical point:

Disclosures: Dr. Tempero reported serving as a scientific advisor and/or receiving grant/research support, consulting fees, and/or honoraria from Celgene Corporation, Champion Oncology, Cornerstone Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, EMD Serono, Gilead Sciences, Halozyme Therapeutics, MCS Biotech Resources, NeoHealth, Novocure, Opsona Therapeutics, Pfizer, Portola Pharmaceuticals, and Threshold Pharmaceuticals.

Myelofibrosis therapies moving beyond ruxolitinib

ORLANDO – Ruxolitinib is currently the only drug approved for the treatment of myelofibrosis, but a number of other therapies are in clinical trials and showing promise, according to Ruben A. Mesa, MD.

“Our field ... is rapidly in evolution,” he said at the annual conference of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, adding that efforts are underway to determine where these drugs might fit in.

Among those being considered specifically for myelofibrosis are pacritinib, momelotinib, PRM-151, and imetelstat, he said.

Pacritinib

This JAK2/FT3 inhibitor reduces splenomegaly and its related symptoms, but may also help patients who have low platelet counts and a worse prognosis. Pacritinib has demonstrated safety in that population, said Dr. Mesa of Mayo Clinic Cancer Center, Phoenix, Ariz.

Concerns about increased mortality related to risk of intracranial hemorrhage and cardiovascular events led the Food and Drug Administration to place a full clinical hold on pacritinib in February 2016. That hold was lifted in January 2017 when data from the randomized, controlled, phase III PERSIST-2 study, as presented at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting in December 2016, showed the risks did not hold up among study patients.

PERSIST-2 compared pacritinib doses of 400 mg once daily and 200 mg twice daily with best alternative therapy, which was ruxolitinib in most patients, Dr. Mesa said. He noted that the study included patients who had marked thrombocytopenia and were allowed prior JAK2 inhibitor exposure.

The 200-mg twice-daily dosing was superior in achieving spleen volume reductions greater than 35%: 22% of patients in the 200-mg dosing group vs. 15% in the 400-mg once-daily dosing group, compared with 3% of those receiving best available therapy. The twice-daily dosing group also experienced greater symptom improvement: Thirty-two percent in the 200-mg twice-daily group vs. 17% in the 400-mg once-daily group achieved at least a 50% reduction in total symptom scale scores, compared with 14% of those receiving best available therapy.

Additional studies of pacritinib will begin enrolling soon, Dr. Mesa said, noting that these studies will look at lower doses in an effort to identify the minimally effective dose with the optimal balance of safety and efficacy.

Momelotinib

Momelotinib, a JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor, was evaluated in two large recently concluded phase III trials (SIMPLIFY-1 and SIMPLIFY-2). SIMPIFY-1 compared momelotinib to ruxolitinib in the front-line setting, and showed momelotinib to be noninferior for reducing splenomegaly.

“However, it was inferior for improvement in the symptom burden,” Dr. Mesa said, noting that while there seemed to be a favorable difference in terms of anemia, the study was structured in such a way that the agent needed to be noninferior for both spleen and symptoms for the anemia response to be evaluable.

SIMPLIFY-2 evaluated momelotinib in patients who had not responded to ruxolitinib. In this second-line setting, momelotinib was not superior to the best alternative therapy, but since the vast majority of the ruxolitinib failure patients remained on ruxolitinib, it is “a bit of a confounded study to assess,” he said.

The top-line data from these studies were issued in a press release from the manufacturer (Gilead) in November 2016, and the complete results are expected to be made public in the near future, at which time more will be known about the next steps for momelotinib, he said.

If approved, pacritinib and momelotinib could ultimately be positioned as a front-line and/or second-line treatment for myelofibrosis, Dr. Mesa predicted.

There has been a goal, in terms of trial design, to see if there is a niche for these drugs in the front-line setting based on blood counts.

“Those recommendations would clearly be very much dependent on the risk, the safety, and the efficacy,” he said.

PRM-151

This antifibrosing agent was shown to be active in early-phase trials – including in stage 1 of an adaptive phase II trial. PRM-151 is currently being evaluated in the fully-accrued ongoing phase II PROMOTE study to determine whether it improves splenomegaly, symptoms, and cytopenia. The primary endpoint of the study is the bone marrow response rate. Study subjects are patients with primary myelofibrosis, post–polycythemia vera myelofibrosis, or post–essential thrombocythemia myelofibrosis, and grade 2-3 fibrosis, said Dr. Mesa, who is the principal investigator for the study.

Imetelstat

This telomerase inhibitor is being evaluated in the randomized, multicenter, phase II IMbark study, designed to assess spleen volume and total symptom score as primary end points. Earlier studies have shown deep responses in patients with myelofibrosis who were treated with imetelstat, Dr. Mesa said.

The IMbark study (NCT02426086) was originally designed to evaluate two dosing regimens administered as a single agent to participants with intermediate-2 or high-risk myelofibrosis who were refractory to or relapsed after JAK inhibitor treatment. Participants received either 9.4 mg/kg or 4.7 mg/kg intravenously every 3 weeks until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or study end.

According to information from Geron, which is developing the agent, enrollment of new participants is currently suspended following a planned internal data review, but enrollment “may be resumed after a second internal data review that is planned by the end of the second quarter of 2017.” If resumed, enrollment would be only to the higher-dose treatment arm; patients initially randomized to that arm may continue treatment, and those randomized to the lower-dose arm may see their dose increased at the investigator’s discretion.

If approved, PRM-151 and imetelstat would likely be positioned as second-line treatments for myelofibrosis, Dr. Mesa said, noting that determining which patients would be most likely to benefit from treatment with these agents would require a close look at the evidence from second-line studies.

Combination therapies

In addition to these investigational treatments, nearly 20 different combination treatments involving ruxolitinib plus another agent have been looked at to try to further improve activity. Some improvements in splenomegaly have been seen with combinations including ruxolitinib and either panobinostat (a histone deacytelase inhibitor), LDE225 (a hedgehog signaling pathway inhibitor), and BKM120 (a PI3-kinase inhibitor), he noted.

“For the area of greatest interest – which was to see incremental improvements in thrombocytopenia, anemia, or fibrosis – there have been favorable data, but they have been modest. It’s not quite clear that there is a combination that is ready for prime time, nor is there yet a combination that we have recommended through the treatment guidelines to be utilized for these patients,” he said.

Dr. Mesa has received consulting fees, honoraria, and/or grant/research support from ARIAD Pharmaceuticals; Celgene Corporation, CTI BioPharma, the maker of pacritinib; Galena Biopharma; Gilead, the maker of momelotinib; Incyte, the maker of ruxolitinib; Novartis, the maker of panobinostat and BKM120; and Promedior, the maker of PRM-151.

ORLANDO – Ruxolitinib is currently the only drug approved for the treatment of myelofibrosis, but a number of other therapies are in clinical trials and showing promise, according to Ruben A. Mesa, MD.

“Our field ... is rapidly in evolution,” he said at the annual conference of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, adding that efforts are underway to determine where these drugs might fit in.

Among those being considered specifically for myelofibrosis are pacritinib, momelotinib, PRM-151, and imetelstat, he said.

Pacritinib

This JAK2/FT3 inhibitor reduces splenomegaly and its related symptoms, but may also help patients who have low platelet counts and a worse prognosis. Pacritinib has demonstrated safety in that population, said Dr. Mesa of Mayo Clinic Cancer Center, Phoenix, Ariz.

Concerns about increased mortality related to risk of intracranial hemorrhage and cardiovascular events led the Food and Drug Administration to place a full clinical hold on pacritinib in February 2016. That hold was lifted in January 2017 when data from the randomized, controlled, phase III PERSIST-2 study, as presented at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting in December 2016, showed the risks did not hold up among study patients.

PERSIST-2 compared pacritinib doses of 400 mg once daily and 200 mg twice daily with best alternative therapy, which was ruxolitinib in most patients, Dr. Mesa said. He noted that the study included patients who had marked thrombocytopenia and were allowed prior JAK2 inhibitor exposure.

The 200-mg twice-daily dosing was superior in achieving spleen volume reductions greater than 35%: 22% of patients in the 200-mg dosing group vs. 15% in the 400-mg once-daily dosing group, compared with 3% of those receiving best available therapy. The twice-daily dosing group also experienced greater symptom improvement: Thirty-two percent in the 200-mg twice-daily group vs. 17% in the 400-mg once-daily group achieved at least a 50% reduction in total symptom scale scores, compared with 14% of those receiving best available therapy.

Additional studies of pacritinib will begin enrolling soon, Dr. Mesa said, noting that these studies will look at lower doses in an effort to identify the minimally effective dose with the optimal balance of safety and efficacy.

Momelotinib

Momelotinib, a JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor, was evaluated in two large recently concluded phase III trials (SIMPLIFY-1 and SIMPLIFY-2). SIMPIFY-1 compared momelotinib to ruxolitinib in the front-line setting, and showed momelotinib to be noninferior for reducing splenomegaly.

“However, it was inferior for improvement in the symptom burden,” Dr. Mesa said, noting that while there seemed to be a favorable difference in terms of anemia, the study was structured in such a way that the agent needed to be noninferior for both spleen and symptoms for the anemia response to be evaluable.

SIMPLIFY-2 evaluated momelotinib in patients who had not responded to ruxolitinib. In this second-line setting, momelotinib was not superior to the best alternative therapy, but since the vast majority of the ruxolitinib failure patients remained on ruxolitinib, it is “a bit of a confounded study to assess,” he said.

The top-line data from these studies were issued in a press release from the manufacturer (Gilead) in November 2016, and the complete results are expected to be made public in the near future, at which time more will be known about the next steps for momelotinib, he said.

If approved, pacritinib and momelotinib could ultimately be positioned as a front-line and/or second-line treatment for myelofibrosis, Dr. Mesa predicted.

There has been a goal, in terms of trial design, to see if there is a niche for these drugs in the front-line setting based on blood counts.

“Those recommendations would clearly be very much dependent on the risk, the safety, and the efficacy,” he said.

PRM-151

This antifibrosing agent was shown to be active in early-phase trials – including in stage 1 of an adaptive phase II trial. PRM-151 is currently being evaluated in the fully-accrued ongoing phase II PROMOTE study to determine whether it improves splenomegaly, symptoms, and cytopenia. The primary endpoint of the study is the bone marrow response rate. Study subjects are patients with primary myelofibrosis, post–polycythemia vera myelofibrosis, or post–essential thrombocythemia myelofibrosis, and grade 2-3 fibrosis, said Dr. Mesa, who is the principal investigator for the study.

Imetelstat

This telomerase inhibitor is being evaluated in the randomized, multicenter, phase II IMbark study, designed to assess spleen volume and total symptom score as primary end points. Earlier studies have shown deep responses in patients with myelofibrosis who were treated with imetelstat, Dr. Mesa said.

The IMbark study (NCT02426086) was originally designed to evaluate two dosing regimens administered as a single agent to participants with intermediate-2 or high-risk myelofibrosis who were refractory to or relapsed after JAK inhibitor treatment. Participants received either 9.4 mg/kg or 4.7 mg/kg intravenously every 3 weeks until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or study end.

According to information from Geron, which is developing the agent, enrollment of new participants is currently suspended following a planned internal data review, but enrollment “may be resumed after a second internal data review that is planned by the end of the second quarter of 2017.” If resumed, enrollment would be only to the higher-dose treatment arm; patients initially randomized to that arm may continue treatment, and those randomized to the lower-dose arm may see their dose increased at the investigator’s discretion.

If approved, PRM-151 and imetelstat would likely be positioned as second-line treatments for myelofibrosis, Dr. Mesa said, noting that determining which patients would be most likely to benefit from treatment with these agents would require a close look at the evidence from second-line studies.

Combination therapies

In addition to these investigational treatments, nearly 20 different combination treatments involving ruxolitinib plus another agent have been looked at to try to further improve activity. Some improvements in splenomegaly have been seen with combinations including ruxolitinib and either panobinostat (a histone deacytelase inhibitor), LDE225 (a hedgehog signaling pathway inhibitor), and BKM120 (a PI3-kinase inhibitor), he noted.

“For the area of greatest interest – which was to see incremental improvements in thrombocytopenia, anemia, or fibrosis – there have been favorable data, but they have been modest. It’s not quite clear that there is a combination that is ready for prime time, nor is there yet a combination that we have recommended through the treatment guidelines to be utilized for these patients,” he said.

Dr. Mesa has received consulting fees, honoraria, and/or grant/research support from ARIAD Pharmaceuticals; Celgene Corporation, CTI BioPharma, the maker of pacritinib; Galena Biopharma; Gilead, the maker of momelotinib; Incyte, the maker of ruxolitinib; Novartis, the maker of panobinostat and BKM120; and Promedior, the maker of PRM-151.

ORLANDO – Ruxolitinib is currently the only drug approved for the treatment of myelofibrosis, but a number of other therapies are in clinical trials and showing promise, according to Ruben A. Mesa, MD.

“Our field ... is rapidly in evolution,” he said at the annual conference of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, adding that efforts are underway to determine where these drugs might fit in.

Among those being considered specifically for myelofibrosis are pacritinib, momelotinib, PRM-151, and imetelstat, he said.

Pacritinib

This JAK2/FT3 inhibitor reduces splenomegaly and its related symptoms, but may also help patients who have low platelet counts and a worse prognosis. Pacritinib has demonstrated safety in that population, said Dr. Mesa of Mayo Clinic Cancer Center, Phoenix, Ariz.

Concerns about increased mortality related to risk of intracranial hemorrhage and cardiovascular events led the Food and Drug Administration to place a full clinical hold on pacritinib in February 2016. That hold was lifted in January 2017 when data from the randomized, controlled, phase III PERSIST-2 study, as presented at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting in December 2016, showed the risks did not hold up among study patients.

PERSIST-2 compared pacritinib doses of 400 mg once daily and 200 mg twice daily with best alternative therapy, which was ruxolitinib in most patients, Dr. Mesa said. He noted that the study included patients who had marked thrombocytopenia and were allowed prior JAK2 inhibitor exposure.

The 200-mg twice-daily dosing was superior in achieving spleen volume reductions greater than 35%: 22% of patients in the 200-mg dosing group vs. 15% in the 400-mg once-daily dosing group, compared with 3% of those receiving best available therapy. The twice-daily dosing group also experienced greater symptom improvement: Thirty-two percent in the 200-mg twice-daily group vs. 17% in the 400-mg once-daily group achieved at least a 50% reduction in total symptom scale scores, compared with 14% of those receiving best available therapy.

Additional studies of pacritinib will begin enrolling soon, Dr. Mesa said, noting that these studies will look at lower doses in an effort to identify the minimally effective dose with the optimal balance of safety and efficacy.

Momelotinib

Momelotinib, a JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor, was evaluated in two large recently concluded phase III trials (SIMPLIFY-1 and SIMPLIFY-2). SIMPIFY-1 compared momelotinib to ruxolitinib in the front-line setting, and showed momelotinib to be noninferior for reducing splenomegaly.

“However, it was inferior for improvement in the symptom burden,” Dr. Mesa said, noting that while there seemed to be a favorable difference in terms of anemia, the study was structured in such a way that the agent needed to be noninferior for both spleen and symptoms for the anemia response to be evaluable.

SIMPLIFY-2 evaluated momelotinib in patients who had not responded to ruxolitinib. In this second-line setting, momelotinib was not superior to the best alternative therapy, but since the vast majority of the ruxolitinib failure patients remained on ruxolitinib, it is “a bit of a confounded study to assess,” he said.

The top-line data from these studies were issued in a press release from the manufacturer (Gilead) in November 2016, and the complete results are expected to be made public in the near future, at which time more will be known about the next steps for momelotinib, he said.

If approved, pacritinib and momelotinib could ultimately be positioned as a front-line and/or second-line treatment for myelofibrosis, Dr. Mesa predicted.

There has been a goal, in terms of trial design, to see if there is a niche for these drugs in the front-line setting based on blood counts.

“Those recommendations would clearly be very much dependent on the risk, the safety, and the efficacy,” he said.

PRM-151

This antifibrosing agent was shown to be active in early-phase trials – including in stage 1 of an adaptive phase II trial. PRM-151 is currently being evaluated in the fully-accrued ongoing phase II PROMOTE study to determine whether it improves splenomegaly, symptoms, and cytopenia. The primary endpoint of the study is the bone marrow response rate. Study subjects are patients with primary myelofibrosis, post–polycythemia vera myelofibrosis, or post–essential thrombocythemia myelofibrosis, and grade 2-3 fibrosis, said Dr. Mesa, who is the principal investigator for the study.

Imetelstat

This telomerase inhibitor is being evaluated in the randomized, multicenter, phase II IMbark study, designed to assess spleen volume and total symptom score as primary end points. Earlier studies have shown deep responses in patients with myelofibrosis who were treated with imetelstat, Dr. Mesa said.

The IMbark study (NCT02426086) was originally designed to evaluate two dosing regimens administered as a single agent to participants with intermediate-2 or high-risk myelofibrosis who were refractory to or relapsed after JAK inhibitor treatment. Participants received either 9.4 mg/kg or 4.7 mg/kg intravenously every 3 weeks until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or study end.

According to information from Geron, which is developing the agent, enrollment of new participants is currently suspended following a planned internal data review, but enrollment “may be resumed after a second internal data review that is planned by the end of the second quarter of 2017.” If resumed, enrollment would be only to the higher-dose treatment arm; patients initially randomized to that arm may continue treatment, and those randomized to the lower-dose arm may see their dose increased at the investigator’s discretion.

If approved, PRM-151 and imetelstat would likely be positioned as second-line treatments for myelofibrosis, Dr. Mesa said, noting that determining which patients would be most likely to benefit from treatment with these agents would require a close look at the evidence from second-line studies.

Combination therapies

In addition to these investigational treatments, nearly 20 different combination treatments involving ruxolitinib plus another agent have been looked at to try to further improve activity. Some improvements in splenomegaly have been seen with combinations including ruxolitinib and either panobinostat (a histone deacytelase inhibitor), LDE225 (a hedgehog signaling pathway inhibitor), and BKM120 (a PI3-kinase inhibitor), he noted.

“For the area of greatest interest – which was to see incremental improvements in thrombocytopenia, anemia, or fibrosis – there have been favorable data, but they have been modest. It’s not quite clear that there is a combination that is ready for prime time, nor is there yet a combination that we have recommended through the treatment guidelines to be utilized for these patients,” he said.

Dr. Mesa has received consulting fees, honoraria, and/or grant/research support from ARIAD Pharmaceuticals; Celgene Corporation, CTI BioPharma, the maker of pacritinib; Galena Biopharma; Gilead, the maker of momelotinib; Incyte, the maker of ruxolitinib; Novartis, the maker of panobinostat and BKM120; and Promedior, the maker of PRM-151.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT THE NCCN ANNUAL CONFERENCE

NCCN myelofibrosis guideline: Patient voice is key

ORLANDO – Referral to a specialized center with expertise in the management of myeloproliferative neoplasms is strongly recommended for all patients diagnosed with myelofibrosis, according to a new treatment guideline from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

The guideline is the first in a series addressing myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), and it focuses on the diagnostic work-up of MPNs, as well as the treatment of myelofibrosis. The guideline panel, led by panel chair Ruben A. Mesa, MD, is working next on guidelines for the other two “core classic” Philadelphia chromosome–negative MPNs: polycythemia vera, and essential thrombocythemia.

Nearly two-thirds of myelofibrosis patients have intermediate-risk 2 or high-risk disease, and treatment decisions in these patients are complex and require patient input – particularly in candidates for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, he said.

“These diseases can be a little different than other malignant diseases,” Dr. Mesa said, explaining that while there is a clear risk of progression to acute myeloid leukemia, and from polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia to myelofibrosis, and while the diseases can be fatal, the burden patients face is not solely related to mortality.

There are implications in terms of health that are independent of that, such as the risk of thrombosis and bleeding, the potential for cytopenia, and severe splenomegaly that results in significant symptoms, he said.

Further, while molecular mutations and their implications for prognosis are a “rapidly moving part of the discussion,” the care of patients with MPNs involves far more than a molecular understanding of the disease.

In fact, the role of molecular changes in these patients is speculative, he said.

While such changes can be assessed and used for patient stratification, their role in myelofibrosis – unlike in other diseases such as chronic myeloid leukemia where the level of change in a target gene is highly relevant and prognostic, is not yet clear.

Thus, a core aspect of the guideline is inclusion of the voice of the patient in individualizing care, he said, noting that many factors should be considered, including how well the patient metabolizes drugs, and the symptom profile, psychosocial circumstances, support structure, and personal beliefs.

“It’s not solely about the tumor,” he stressed.

In fact, the answer to the question of whether a patient can be symptomatic enough to require a specific treatment is “no,” because of the potential for side effects, risk, expense, and other considerations.

“So the voice of the patient is always a key part [of the decision],” he said, noting also that as with all NCCN guidelines, this guideline is a partnership with the treating physician; deciding who is a transplant candidate is a nuanced issue for which the panel provides “discussion and guidance.”

“But clearly, these guidelines are the most useful and helpful in the setting of experienced providers bringing all of their experiences to bear,” he said.

In general, however, the guidelines call for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) in those with intermediate-risk 2 or high-risk disease who are transplant candidates, and treatment based on assessment of symptom burden (using the MPN–Symptom Assessment Form Total Symptom Score–10 Items) in those who are not HCT candidates. Those with platelets at 50,000 or below should be considered for clinical trial enrollment, and those with platelets above 50,000 should be considered for a clinical trial or treatment with the oral JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitor ruxolitinib, which has been shown to have beneficial effects on both symptoms and survival and which is approved for patients with platelets above 50,000. .

Treated patients should be monitored for response and for signs and symptoms of disease progression every 3-6 months. Treatment should continue in those who respond, as well as in those who do not – as long as there is no disease progression.

Those with progressive disease include patients who are moving toward acute leukemia, and those with overt acute leukemia.

“Here is where the key decision occurs. Are they or are they not a transplant candidate? If they are a candidate, we have a potentially curative track which would include cytoreduction followed by transplant,” Dr. Mesa said.

Cytoreduction can involve hypomethylating agents if the patient doesn’t have excess blast cells or too high a burden of disease.

Acute myeloid leukemia–like induction chemotherapy followed by allogeneic HCT is also an option in these patients.

As for treatment of low-risk myelofibrosis, the guideline states that asymptomatic patients can be observed or enrolled in a clinical trial and monitored for progression every 3-6 months, and that symptomatic patients should receive ruxolitinib or interferons (which are used off label), or be enrolled in a clinical trial. Treatment is important for patients with particularly difficult symptoms, he said, noting that some patients have had pruritus so severe that they have committed suicide. Treatment should continue unless monitoring shows signs of progression to intermediate risk 1, intermediate risk 2/high-risk, or advanced stage disease.

For those with intermediate risk 1 disease, the guideline calls for observation or ruxolitinib in those who are symptomatic, or clinical trial enrollment or allogeneic HCT. Treatment should continue unless monitoring shows disease progression, in which case the appropriate algorithm should be considered.

The guideline also addresses several special circumstances, including the management of anemia in myelofibrosis patients, which can be a difficult issue, he said.

Since the guideline was first published in December, two updates have been incorporated, and Dr. Mesa said that he anticipates regular updates given the rapidly evolving understanding of MPNs and new findings with respect to potential treatment strategies.

He noted that a number of drugs are currently in clinical trials involving patients with myelofibrosis, including the JAK2/FLT3 inhibitor pacritinib, the JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor momelotinib, the active antifibrosing agent PRM-151, and the telomerase inhibitor imetelstat, as well as numerous drug combinations.

Going forward, the guideline panel will be focusing on four different areas of assessment, including new therapies and new genetic therapies, improving transplant outcomes, MPN symptom and quality of life assessment, and nonpharmacologic interventions such as yoga.

“We certainly hope to complement things over time, to look not only at pharmacologic interventions, but others that patients may be able to utilize from a toolkit of resources,” he said.

COMFORT-1 update: ruxolitinib responses durable in myelofibrosis

To date, ruxolitinib is the only Food and Drug Administration–approved drug for the treatment of myelofibrosis.

The randomized controlled phase III COMFORT I and II trials conducted in the United States and Europe, respectively, demonstrated that the oral JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor has a rapid, beneficial impact on both survival and disease-associated enlargement of the spleen and improvement in related symptoms, Dr. Mesa said.

A 5-year update on data from 309 patients in the COMFORT-1 trial, as reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology in 2016, confirmed the durability of treatment responses to ruxolitinib in patients initially randomized to receive the drug, he said.

“We were able to demonstrate a continued survival advantage for those individuals receiving ruxolitinib,” he added.

At weeks 24 and 264, the mean spleen volume reduction was 31.6% and 37.6%, respectively, in those originally randomized to ruxolitinib. The median duration of at least 35% spleen volume reduction was 168.3 weeks.

Overall survival favored ruxolitinib (hazard ratio, 0.69). Median overall survival in the ruxolitinib group had not yet been reached.

“But we realize our work is not done. The survival curve does not plateau; we are not curing these patients. We’re having meaningful impact, but we have room to continue to improve,” he said.

Also, there is an initial drop in platelet counts that tends to stabilize, but not improve, and there is worsening of anemia (new onset grade 3 or 4 anemia was 25.2% with ruxolitinib, and 26.1% in 111 of 154 patients who crossed over from the placebo group), and although this tends to improve, these are among areas of unmet need, he added.

Further, long-term risks of treatment include cutaneous malignancies (basal cell carcinoma occurred in 7.7% and 9.0% of treatment and crossover patients, respectively), which are difficult to separate from baseline hydroxyurea use, and increased risk of herpes zoster (which occurred in 10.3% and 13.5% of treated and crossover patients).

However, there appears to be no increased risk – and there may be a slight decreased risk – of progression to acute leukemia, Dr. Mesa said.

Dr. Mesa disclosed that he has received consulting fees, honoraria, and/or grant/research support from ARIAD Pharmaceuticals, Celgene, CTI BioPharma, Galena Biopharma, Gilead Sciences, Incyte, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, and Promedior.

A step toward harmonizing treatment

Myelofibrosis is a rare chronic leukemia with a complex biology. Disease heterogeneity poses several challenges in the appropriate selection and timing of treatments in this disorder. The NCCN Practice Guidelines in Myelofibrosis is an important step towards harmonizing clinical practice for treating this disease and improving the care of patients.

Vikas Gupta, MD, FRCP, FRCPath, is Director of The Elizabeth and Tony Comper MPN Program at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto and a member of the editorial advisory board of Hematology News.

A step toward harmonizing treatment

Myelofibrosis is a rare chronic leukemia with a complex biology. Disease heterogeneity poses several challenges in the appropriate selection and timing of treatments in this disorder. The NCCN Practice Guidelines in Myelofibrosis is an important step towards harmonizing clinical practice for treating this disease and improving the care of patients.

Vikas Gupta, MD, FRCP, FRCPath, is Director of The Elizabeth and Tony Comper MPN Program at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto and a member of the editorial advisory board of Hematology News.

A step toward harmonizing treatment

Myelofibrosis is a rare chronic leukemia with a complex biology. Disease heterogeneity poses several challenges in the appropriate selection and timing of treatments in this disorder. The NCCN Practice Guidelines in Myelofibrosis is an important step towards harmonizing clinical practice for treating this disease and improving the care of patients.

Vikas Gupta, MD, FRCP, FRCPath, is Director of The Elizabeth and Tony Comper MPN Program at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto and a member of the editorial advisory board of Hematology News.

ORLANDO – Referral to a specialized center with expertise in the management of myeloproliferative neoplasms is strongly recommended for all patients diagnosed with myelofibrosis, according to a new treatment guideline from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

The guideline is the first in a series addressing myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), and it focuses on the diagnostic work-up of MPNs, as well as the treatment of myelofibrosis. The guideline panel, led by panel chair Ruben A. Mesa, MD, is working next on guidelines for the other two “core classic” Philadelphia chromosome–negative MPNs: polycythemia vera, and essential thrombocythemia.

Nearly two-thirds of myelofibrosis patients have intermediate-risk 2 or high-risk disease, and treatment decisions in these patients are complex and require patient input – particularly in candidates for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, he said.

“These diseases can be a little different than other malignant diseases,” Dr. Mesa said, explaining that while there is a clear risk of progression to acute myeloid leukemia, and from polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia to myelofibrosis, and while the diseases can be fatal, the burden patients face is not solely related to mortality.

There are implications in terms of health that are independent of that, such as the risk of thrombosis and bleeding, the potential for cytopenia, and severe splenomegaly that results in significant symptoms, he said.

Further, while molecular mutations and their implications for prognosis are a “rapidly moving part of the discussion,” the care of patients with MPNs involves far more than a molecular understanding of the disease.

In fact, the role of molecular changes in these patients is speculative, he said.

While such changes can be assessed and used for patient stratification, their role in myelofibrosis – unlike in other diseases such as chronic myeloid leukemia where the level of change in a target gene is highly relevant and prognostic, is not yet clear.

Thus, a core aspect of the guideline is inclusion of the voice of the patient in individualizing care, he said, noting that many factors should be considered, including how well the patient metabolizes drugs, and the symptom profile, psychosocial circumstances, support structure, and personal beliefs.

“It’s not solely about the tumor,” he stressed.

In fact, the answer to the question of whether a patient can be symptomatic enough to require a specific treatment is “no,” because of the potential for side effects, risk, expense, and other considerations.

“So the voice of the patient is always a key part [of the decision],” he said, noting also that as with all NCCN guidelines, this guideline is a partnership with the treating physician; deciding who is a transplant candidate is a nuanced issue for which the panel provides “discussion and guidance.”

“But clearly, these guidelines are the most useful and helpful in the setting of experienced providers bringing all of their experiences to bear,” he said.

In general, however, the guidelines call for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) in those with intermediate-risk 2 or high-risk disease who are transplant candidates, and treatment based on assessment of symptom burden (using the MPN–Symptom Assessment Form Total Symptom Score–10 Items) in those who are not HCT candidates. Those with platelets at 50,000 or below should be considered for clinical trial enrollment, and those with platelets above 50,000 should be considered for a clinical trial or treatment with the oral JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitor ruxolitinib, which has been shown to have beneficial effects on both symptoms and survival and which is approved for patients with platelets above 50,000. .

Treated patients should be monitored for response and for signs and symptoms of disease progression every 3-6 months. Treatment should continue in those who respond, as well as in those who do not – as long as there is no disease progression.

Those with progressive disease include patients who are moving toward acute leukemia, and those with overt acute leukemia.

“Here is where the key decision occurs. Are they or are they not a transplant candidate? If they are a candidate, we have a potentially curative track which would include cytoreduction followed by transplant,” Dr. Mesa said.

Cytoreduction can involve hypomethylating agents if the patient doesn’t have excess blast cells or too high a burden of disease.

Acute myeloid leukemia–like induction chemotherapy followed by allogeneic HCT is also an option in these patients.

As for treatment of low-risk myelofibrosis, the guideline states that asymptomatic patients can be observed or enrolled in a clinical trial and monitored for progression every 3-6 months, and that symptomatic patients should receive ruxolitinib or interferons (which are used off label), or be enrolled in a clinical trial. Treatment is important for patients with particularly difficult symptoms, he said, noting that some patients have had pruritus so severe that they have committed suicide. Treatment should continue unless monitoring shows signs of progression to intermediate risk 1, intermediate risk 2/high-risk, or advanced stage disease.

For those with intermediate risk 1 disease, the guideline calls for observation or ruxolitinib in those who are symptomatic, or clinical trial enrollment or allogeneic HCT. Treatment should continue unless monitoring shows disease progression, in which case the appropriate algorithm should be considered.

The guideline also addresses several special circumstances, including the management of anemia in myelofibrosis patients, which can be a difficult issue, he said.

Since the guideline was first published in December, two updates have been incorporated, and Dr. Mesa said that he anticipates regular updates given the rapidly evolving understanding of MPNs and new findings with respect to potential treatment strategies.