User login

New ACGME-Compliant Staffing Model Cuts Hospital Costs

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – July brings more restrictions on resident duty hours, but compliance with these requirements can result in reduced hospitalization costs and shorter lengths of stay, if it’s done right.

A study by hospitalists at the University of California, San Francisco’s Benioff Children’s Hospital that analyzed their attempt to cut resident work hours by enlarging care teams and eliminating cross coverage found that a new staffing model reduced hospitalization costs by about 11% and length of stay by about 18%.

Starting July 1, new resident duty-hours requirements from the ACGME (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education) will go into effect, eliminating long shifts for interns. Specifically, interns (PGY-1 residents) will no longer be able to work 30-hour shifts, but will be limited to shifts of no more than 16 hours.

In September 2008, UCSF expanded and reorganized its pediatric inpatient hospitalist service, moving from a traditional call model to a shift-based staffing model. In the process, the hospital eliminated cross-coverage of different teams in favor of dedicated night teams that were subsets of their day teams.

The goal was to increase "patient ownership" by reducing handoffs and to improve patient care by having a more consistent provider overnight, said Dr. Glenn Rosenbluth, a pediatric hospitalist at the hospital. He presented the study results at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

"The idea was that a resident working a 30-hour shift at 2 in the morning might be more focused on just urgent issues, calls from the nurses, and potentially seeing the call room when they get some down time, whereas someone working a week of dedicated night shifts might be more awake and more interested in advancing care because they’re a member of the primary team," he said.

Prior to September 2008, general pediatrics patients were covered by house-staff teams comprising two interns and one senior resident who were working shifts of up to 30 hours. The interns took call every sixth night and senior residents took call every fifth night. They provided cross-coverage of patients on multiple teams at night. Generally, this meant that one team was working each night and covering for all other teams, Dr. Rosenbluth said.

After the reorganization, they expanded the house-staff teams to four interns per team, with each intern working 3 weeks of day shift and 6 consecutive night shifts. The shifts were generally about 13 hours. The changes allowed them to eliminate cross-coverage and to have a dedicated night team. The attending coverage by hospitalists was unchanged.

To study the impact of the new staffing model, the researchers performed a retrospective, interrupted time series cohort study using concurrent controls. The target group was children who were admitted to the hospital’s general pediatric service. The concurrent control group consisted of surgical patients who were admitted to the same inpatient unit.

Using administrative billing data from the medical center, they analyzed hospitalization costs and length of stay for children who were admitted to the pediatric medical-surgical unit from Sept. 15, 2007, through Sept. 15, 2009. The researchers analyzed data on 280 patients before intervention and 274 patients after intervention. They excluded patients who had spent any time in the pediatric ICU and patients who were on specialty services not covered by either a pediatric hospitalist or a general surgeon. The researchers used multivariate models to adjust for age, sex, the season of year, the admitting diagnosis, and any clustering at the attending level.

They found that for general pediatric patients who were admitted to the medical-surgical unit there was an adjusted rate ratio of 0.82 for length of stay following the intervention. That was an 18% decrease in length of stay from before the intervention. Similarly, hospitalization costs had an adjusted rate ratio of 0.89, an 11% decrease from before the intervention. Among the surgery patients who acted as the control group, there was no statistically significant change in the length of stay and there was a small increase in the cost of hospitalization.

Although there may be incremental costs associated with making the staffing changes needed to comply with the new ACGME duty-hours requirements, Dr. Rosenbluth said the study suggests that these costs may be partially offset by improved care efficiency.

But Dr. Rosenbluth acknowledged that the study did have some limitations. The biggest issue is the limited ability to disentangle the impact of scheduling changes from other changes that were occurring on the unit at the same time. "There was a lot going on, as is the case on all of our units," he said.

The authors reported no disclosures.

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – July brings more restrictions on resident duty hours, but compliance with these requirements can result in reduced hospitalization costs and shorter lengths of stay, if it’s done right.

A study by hospitalists at the University of California, San Francisco’s Benioff Children’s Hospital that analyzed their attempt to cut resident work hours by enlarging care teams and eliminating cross coverage found that a new staffing model reduced hospitalization costs by about 11% and length of stay by about 18%.

Starting July 1, new resident duty-hours requirements from the ACGME (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education) will go into effect, eliminating long shifts for interns. Specifically, interns (PGY-1 residents) will no longer be able to work 30-hour shifts, but will be limited to shifts of no more than 16 hours.

In September 2008, UCSF expanded and reorganized its pediatric inpatient hospitalist service, moving from a traditional call model to a shift-based staffing model. In the process, the hospital eliminated cross-coverage of different teams in favor of dedicated night teams that were subsets of their day teams.

The goal was to increase "patient ownership" by reducing handoffs and to improve patient care by having a more consistent provider overnight, said Dr. Glenn Rosenbluth, a pediatric hospitalist at the hospital. He presented the study results at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

"The idea was that a resident working a 30-hour shift at 2 in the morning might be more focused on just urgent issues, calls from the nurses, and potentially seeing the call room when they get some down time, whereas someone working a week of dedicated night shifts might be more awake and more interested in advancing care because they’re a member of the primary team," he said.

Prior to September 2008, general pediatrics patients were covered by house-staff teams comprising two interns and one senior resident who were working shifts of up to 30 hours. The interns took call every sixth night and senior residents took call every fifth night. They provided cross-coverage of patients on multiple teams at night. Generally, this meant that one team was working each night and covering for all other teams, Dr. Rosenbluth said.

After the reorganization, they expanded the house-staff teams to four interns per team, with each intern working 3 weeks of day shift and 6 consecutive night shifts. The shifts were generally about 13 hours. The changes allowed them to eliminate cross-coverage and to have a dedicated night team. The attending coverage by hospitalists was unchanged.

To study the impact of the new staffing model, the researchers performed a retrospective, interrupted time series cohort study using concurrent controls. The target group was children who were admitted to the hospital’s general pediatric service. The concurrent control group consisted of surgical patients who were admitted to the same inpatient unit.

Using administrative billing data from the medical center, they analyzed hospitalization costs and length of stay for children who were admitted to the pediatric medical-surgical unit from Sept. 15, 2007, through Sept. 15, 2009. The researchers analyzed data on 280 patients before intervention and 274 patients after intervention. They excluded patients who had spent any time in the pediatric ICU and patients who were on specialty services not covered by either a pediatric hospitalist or a general surgeon. The researchers used multivariate models to adjust for age, sex, the season of year, the admitting diagnosis, and any clustering at the attending level.

They found that for general pediatric patients who were admitted to the medical-surgical unit there was an adjusted rate ratio of 0.82 for length of stay following the intervention. That was an 18% decrease in length of stay from before the intervention. Similarly, hospitalization costs had an adjusted rate ratio of 0.89, an 11% decrease from before the intervention. Among the surgery patients who acted as the control group, there was no statistically significant change in the length of stay and there was a small increase in the cost of hospitalization.

Although there may be incremental costs associated with making the staffing changes needed to comply with the new ACGME duty-hours requirements, Dr. Rosenbluth said the study suggests that these costs may be partially offset by improved care efficiency.

But Dr. Rosenbluth acknowledged that the study did have some limitations. The biggest issue is the limited ability to disentangle the impact of scheduling changes from other changes that were occurring on the unit at the same time. "There was a lot going on, as is the case on all of our units," he said.

The authors reported no disclosures.

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – July brings more restrictions on resident duty hours, but compliance with these requirements can result in reduced hospitalization costs and shorter lengths of stay, if it’s done right.

A study by hospitalists at the University of California, San Francisco’s Benioff Children’s Hospital that analyzed their attempt to cut resident work hours by enlarging care teams and eliminating cross coverage found that a new staffing model reduced hospitalization costs by about 11% and length of stay by about 18%.

Starting July 1, new resident duty-hours requirements from the ACGME (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education) will go into effect, eliminating long shifts for interns. Specifically, interns (PGY-1 residents) will no longer be able to work 30-hour shifts, but will be limited to shifts of no more than 16 hours.

In September 2008, UCSF expanded and reorganized its pediatric inpatient hospitalist service, moving from a traditional call model to a shift-based staffing model. In the process, the hospital eliminated cross-coverage of different teams in favor of dedicated night teams that were subsets of their day teams.

The goal was to increase "patient ownership" by reducing handoffs and to improve patient care by having a more consistent provider overnight, said Dr. Glenn Rosenbluth, a pediatric hospitalist at the hospital. He presented the study results at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

"The idea was that a resident working a 30-hour shift at 2 in the morning might be more focused on just urgent issues, calls from the nurses, and potentially seeing the call room when they get some down time, whereas someone working a week of dedicated night shifts might be more awake and more interested in advancing care because they’re a member of the primary team," he said.

Prior to September 2008, general pediatrics patients were covered by house-staff teams comprising two interns and one senior resident who were working shifts of up to 30 hours. The interns took call every sixth night and senior residents took call every fifth night. They provided cross-coverage of patients on multiple teams at night. Generally, this meant that one team was working each night and covering for all other teams, Dr. Rosenbluth said.

After the reorganization, they expanded the house-staff teams to four interns per team, with each intern working 3 weeks of day shift and 6 consecutive night shifts. The shifts were generally about 13 hours. The changes allowed them to eliminate cross-coverage and to have a dedicated night team. The attending coverage by hospitalists was unchanged.

To study the impact of the new staffing model, the researchers performed a retrospective, interrupted time series cohort study using concurrent controls. The target group was children who were admitted to the hospital’s general pediatric service. The concurrent control group consisted of surgical patients who were admitted to the same inpatient unit.

Using administrative billing data from the medical center, they analyzed hospitalization costs and length of stay for children who were admitted to the pediatric medical-surgical unit from Sept. 15, 2007, through Sept. 15, 2009. The researchers analyzed data on 280 patients before intervention and 274 patients after intervention. They excluded patients who had spent any time in the pediatric ICU and patients who were on specialty services not covered by either a pediatric hospitalist or a general surgeon. The researchers used multivariate models to adjust for age, sex, the season of year, the admitting diagnosis, and any clustering at the attending level.

They found that for general pediatric patients who were admitted to the medical-surgical unit there was an adjusted rate ratio of 0.82 for length of stay following the intervention. That was an 18% decrease in length of stay from before the intervention. Similarly, hospitalization costs had an adjusted rate ratio of 0.89, an 11% decrease from before the intervention. Among the surgery patients who acted as the control group, there was no statistically significant change in the length of stay and there was a small increase in the cost of hospitalization.

Although there may be incremental costs associated with making the staffing changes needed to comply with the new ACGME duty-hours requirements, Dr. Rosenbluth said the study suggests that these costs may be partially offset by improved care efficiency.

But Dr. Rosenbluth acknowledged that the study did have some limitations. The biggest issue is the limited ability to disentangle the impact of scheduling changes from other changes that were occurring on the unit at the same time. "There was a lot going on, as is the case on all of our units," he said.

The authors reported no disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOCIETY OF HOSPITAL MEDICINE

Give Infections and Antibiotics Their Due Respect

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – Respect. That is what it takes for the savvy hospitalist to pick a drug that’s safe for the patient and kills the bug.

Respect for both the pathogen and the drug that destroys it can make the difference between curing an infective illness and prescribing unnecessary treatment that can harm the patient.

Staphylococcus aureus, for example, can never be underestimated. "It never, ever ceases to amaze me in how virulent and aggressive it can be," Dr. Shanta Zimmer said at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

On the other hand, she said, physicians must remember the serious comorbidities patients can experience with multiple drug therapy, or even with a single antibiotic.

"Respect the drugs. We often do things to our patients that are harmful, giving them unnecessary therapy. We can’t commit a patient to a line of therapy that may or may not be warranted because we can’t say for sure that there is an infection," or what the infective agent is. "So, take your time. Do a repeat culture. In infectious disease, we often have time to think and get more data before we make a decision."

Dr. Zimmer, an infectious disease expert at the University of Pittsburgh, presented the following cases to illustrate her approach:

• A woman who is between chemotherapy cycles for breast cancer presents with fever and reports chills when the port is flushed. Blood cultures from both port and periphery grow Candida albicans; the port also grows coagulase-negative staphylococcus.

Decisions about her treatment depend not only on the organism, but also on the environment. "If you have a patient in a hospital area where you see a lot of Candida, consider a kinase inhibitor as the first line of therapy. If you don’t see that much in your facility, it’s okay to start with fluconazole as the first line."

A big advantage of these drugs is their high oral bioavailability. "You can give them orally and not have to send the patient home with a PICC [peripherally inserted central catheter] line."

Treatment should continue for 14 days past the first negative blood culture, but don’t rush the timeline with Candida, she warned. "This is something that can grow very slowly, so you have to wait longer than 48 hours to really determine if the culture is negative. Often I wait 3 or 4 days to make sure that culture is clear."

When possible, remove any infected line, but especially one infected with Candida. "For Candida and [S. aureus], always remove the line. Never try to leave it in for one of those [infections]," Dr. Simmer said. For other organisms, removing the line is still preferable. "I realize this is sometimes a difficult decision, but it makes your treatment regimen so much easier."

• A 62-year-old man who had a recent mitral valve repair presents with a fever, some gaze abnormalities, and altered mental status. A transthoracic echocardiogram shows a 1.6-cm vegetation on the valve, and an MRI showed a new occipital stroke. The blood culture grew Streptococcus viridans.

Alpha-hemolytic streptococcus is one of the most common causes of endocarditis. The pathogens react differently to penicillin, depending on the species and virulence factors. Although the patient needs immediate empirical therapy with a broad-spectrum antibiotic, "the key here is to check the minimum inhibitory concentration [MIC] for penicillin before you change" to something more specific, she said. "If the MIC for penicillin is low, use penicillin for 4 weeks, or penicillin plus gentamycin for 2 weeks. If the MIC is intermediate, you really need to do 4 weeks of penicillin and add gentamycin for the first 2 weeks. If it’s high, then you need an enterococcal regimen."

• A 37-year-old man who had refractory acute myeloid leukemia and was awaiting a matched, unrelated-donor transplant presents with a large purplish lesion on his fingertip, which he said began to appear during a game of baseball with his son. As an outpatient, he takes levofloxacin, fluconazole and acyclovir. A culture grows Gram-negative Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

"When you suspect a Gram-negative bacteremia in an immunocompromised patient, you can’t wait for a susceptibility test to come back," Dr. Zimmer said. "Start with whatever Gram-negative coverage is working best at your hospital." Although the literature doesn’t completely support the use of multiple drugs, "I often use double coverage because resistance is high in many hospitals, and getting it right the first time is really important. My main reason for doing this is to make sure that one of the two agents is going to be effective against this organism."

• A 39-year-old construction worker comes in with multiple injuries after an off-roading vehicle accident. On hospital day 7, he develops severe facial swelling and periorbital pain; imaging shows a periorbital abscess with extension toward the brain.

"This man had an invasive fungal zygomycosis," Dr. Zimmer said. "This often involves the nose, sinuses, and eye and can extend directly into the brain. Mortality is extremely high, around 80%."

In a case like this, start empirical therapy with a broad antifungal immediately, but the real answer for this problem is surgical debridement. "If they can’t get to the operating room, they need to go into hospice." Patients usually need multiple debridements, because the fungus can grow back on a daily basis.

Posaconazole has become the drug of choice over the last few years, but may be impractical for those with zygomycosis. "It can only be taken orally, and these patients often have a hard time swallowing. I usually start fluconazole and a lipid formulation of amphotericin. It takes awhile for posaconazole to reach good blood levels, and it should be administered with a fatty meal."

• A 25-year-old female student presents with a low-grade fever and bilateral facial palsy. Imaging shows inflammation of facial nerves.

"Bilateral facial palsies are very rare," Dr. Zimmer said. "There can be noninfective causes, but the most common infectious cause is Lyme disease."

In considering the differential diagnosis, the patient history, outdoor activities, and geography are all important. "If you’re looking at a young, otherwise healthy person who spends some time in the woods," where Lyme is endemic, then Lyme is a good bet, she noted.

A lumbar puncture that shows lymphocytes, in conjunction with a Western blot that is positive for Lyme "puts you in good shape" with a diagnosis. "Lyme antibody is very sensitive but not very specific."

Treatment of central nervous system Lyme "is a little bit controversial," Dr. Zimmer said. Most U.S. physicians use intravenous ceftriaxone or penicillin for 14 days. A 14-day course of oral doxycycline is also effective, but not as common in this country. "All the studies have been done in Europe, so U.S. physicians are somewhat reluctant to use this, but no studies have shown any difference between IV antibiotics and oral doxycycline."

Dr. Zimmer reported having no financial disclosures.

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – Respect. That is what it takes for the savvy hospitalist to pick a drug that’s safe for the patient and kills the bug.

Respect for both the pathogen and the drug that destroys it can make the difference between curing an infective illness and prescribing unnecessary treatment that can harm the patient.

Staphylococcus aureus, for example, can never be underestimated. "It never, ever ceases to amaze me in how virulent and aggressive it can be," Dr. Shanta Zimmer said at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

On the other hand, she said, physicians must remember the serious comorbidities patients can experience with multiple drug therapy, or even with a single antibiotic.

"Respect the drugs. We often do things to our patients that are harmful, giving them unnecessary therapy. We can’t commit a patient to a line of therapy that may or may not be warranted because we can’t say for sure that there is an infection," or what the infective agent is. "So, take your time. Do a repeat culture. In infectious disease, we often have time to think and get more data before we make a decision."

Dr. Zimmer, an infectious disease expert at the University of Pittsburgh, presented the following cases to illustrate her approach:

• A woman who is between chemotherapy cycles for breast cancer presents with fever and reports chills when the port is flushed. Blood cultures from both port and periphery grow Candida albicans; the port also grows coagulase-negative staphylococcus.

Decisions about her treatment depend not only on the organism, but also on the environment. "If you have a patient in a hospital area where you see a lot of Candida, consider a kinase inhibitor as the first line of therapy. If you don’t see that much in your facility, it’s okay to start with fluconazole as the first line."

A big advantage of these drugs is their high oral bioavailability. "You can give them orally and not have to send the patient home with a PICC [peripherally inserted central catheter] line."

Treatment should continue for 14 days past the first negative blood culture, but don’t rush the timeline with Candida, she warned. "This is something that can grow very slowly, so you have to wait longer than 48 hours to really determine if the culture is negative. Often I wait 3 or 4 days to make sure that culture is clear."

When possible, remove any infected line, but especially one infected with Candida. "For Candida and [S. aureus], always remove the line. Never try to leave it in for one of those [infections]," Dr. Simmer said. For other organisms, removing the line is still preferable. "I realize this is sometimes a difficult decision, but it makes your treatment regimen so much easier."

• A 62-year-old man who had a recent mitral valve repair presents with a fever, some gaze abnormalities, and altered mental status. A transthoracic echocardiogram shows a 1.6-cm vegetation on the valve, and an MRI showed a new occipital stroke. The blood culture grew Streptococcus viridans.

Alpha-hemolytic streptococcus is one of the most common causes of endocarditis. The pathogens react differently to penicillin, depending on the species and virulence factors. Although the patient needs immediate empirical therapy with a broad-spectrum antibiotic, "the key here is to check the minimum inhibitory concentration [MIC] for penicillin before you change" to something more specific, she said. "If the MIC for penicillin is low, use penicillin for 4 weeks, or penicillin plus gentamycin for 2 weeks. If the MIC is intermediate, you really need to do 4 weeks of penicillin and add gentamycin for the first 2 weeks. If it’s high, then you need an enterococcal regimen."

• A 37-year-old man who had refractory acute myeloid leukemia and was awaiting a matched, unrelated-donor transplant presents with a large purplish lesion on his fingertip, which he said began to appear during a game of baseball with his son. As an outpatient, he takes levofloxacin, fluconazole and acyclovir. A culture grows Gram-negative Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

"When you suspect a Gram-negative bacteremia in an immunocompromised patient, you can’t wait for a susceptibility test to come back," Dr. Zimmer said. "Start with whatever Gram-negative coverage is working best at your hospital." Although the literature doesn’t completely support the use of multiple drugs, "I often use double coverage because resistance is high in many hospitals, and getting it right the first time is really important. My main reason for doing this is to make sure that one of the two agents is going to be effective against this organism."

• A 39-year-old construction worker comes in with multiple injuries after an off-roading vehicle accident. On hospital day 7, he develops severe facial swelling and periorbital pain; imaging shows a periorbital abscess with extension toward the brain.

"This man had an invasive fungal zygomycosis," Dr. Zimmer said. "This often involves the nose, sinuses, and eye and can extend directly into the brain. Mortality is extremely high, around 80%."

In a case like this, start empirical therapy with a broad antifungal immediately, but the real answer for this problem is surgical debridement. "If they can’t get to the operating room, they need to go into hospice." Patients usually need multiple debridements, because the fungus can grow back on a daily basis.

Posaconazole has become the drug of choice over the last few years, but may be impractical for those with zygomycosis. "It can only be taken orally, and these patients often have a hard time swallowing. I usually start fluconazole and a lipid formulation of amphotericin. It takes awhile for posaconazole to reach good blood levels, and it should be administered with a fatty meal."

• A 25-year-old female student presents with a low-grade fever and bilateral facial palsy. Imaging shows inflammation of facial nerves.

"Bilateral facial palsies are very rare," Dr. Zimmer said. "There can be noninfective causes, but the most common infectious cause is Lyme disease."

In considering the differential diagnosis, the patient history, outdoor activities, and geography are all important. "If you’re looking at a young, otherwise healthy person who spends some time in the woods," where Lyme is endemic, then Lyme is a good bet, she noted.

A lumbar puncture that shows lymphocytes, in conjunction with a Western blot that is positive for Lyme "puts you in good shape" with a diagnosis. "Lyme antibody is very sensitive but not very specific."

Treatment of central nervous system Lyme "is a little bit controversial," Dr. Zimmer said. Most U.S. physicians use intravenous ceftriaxone or penicillin for 14 days. A 14-day course of oral doxycycline is also effective, but not as common in this country. "All the studies have been done in Europe, so U.S. physicians are somewhat reluctant to use this, but no studies have shown any difference between IV antibiotics and oral doxycycline."

Dr. Zimmer reported having no financial disclosures.

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – Respect. That is what it takes for the savvy hospitalist to pick a drug that’s safe for the patient and kills the bug.

Respect for both the pathogen and the drug that destroys it can make the difference between curing an infective illness and prescribing unnecessary treatment that can harm the patient.

Staphylococcus aureus, for example, can never be underestimated. "It never, ever ceases to amaze me in how virulent and aggressive it can be," Dr. Shanta Zimmer said at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

On the other hand, she said, physicians must remember the serious comorbidities patients can experience with multiple drug therapy, or even with a single antibiotic.

"Respect the drugs. We often do things to our patients that are harmful, giving them unnecessary therapy. We can’t commit a patient to a line of therapy that may or may not be warranted because we can’t say for sure that there is an infection," or what the infective agent is. "So, take your time. Do a repeat culture. In infectious disease, we often have time to think and get more data before we make a decision."

Dr. Zimmer, an infectious disease expert at the University of Pittsburgh, presented the following cases to illustrate her approach:

• A woman who is between chemotherapy cycles for breast cancer presents with fever and reports chills when the port is flushed. Blood cultures from both port and periphery grow Candida albicans; the port also grows coagulase-negative staphylococcus.

Decisions about her treatment depend not only on the organism, but also on the environment. "If you have a patient in a hospital area where you see a lot of Candida, consider a kinase inhibitor as the first line of therapy. If you don’t see that much in your facility, it’s okay to start with fluconazole as the first line."

A big advantage of these drugs is their high oral bioavailability. "You can give them orally and not have to send the patient home with a PICC [peripherally inserted central catheter] line."

Treatment should continue for 14 days past the first negative blood culture, but don’t rush the timeline with Candida, she warned. "This is something that can grow very slowly, so you have to wait longer than 48 hours to really determine if the culture is negative. Often I wait 3 or 4 days to make sure that culture is clear."

When possible, remove any infected line, but especially one infected with Candida. "For Candida and [S. aureus], always remove the line. Never try to leave it in for one of those [infections]," Dr. Simmer said. For other organisms, removing the line is still preferable. "I realize this is sometimes a difficult decision, but it makes your treatment regimen so much easier."

• A 62-year-old man who had a recent mitral valve repair presents with a fever, some gaze abnormalities, and altered mental status. A transthoracic echocardiogram shows a 1.6-cm vegetation on the valve, and an MRI showed a new occipital stroke. The blood culture grew Streptococcus viridans.

Alpha-hemolytic streptococcus is one of the most common causes of endocarditis. The pathogens react differently to penicillin, depending on the species and virulence factors. Although the patient needs immediate empirical therapy with a broad-spectrum antibiotic, "the key here is to check the minimum inhibitory concentration [MIC] for penicillin before you change" to something more specific, she said. "If the MIC for penicillin is low, use penicillin for 4 weeks, or penicillin plus gentamycin for 2 weeks. If the MIC is intermediate, you really need to do 4 weeks of penicillin and add gentamycin for the first 2 weeks. If it’s high, then you need an enterococcal regimen."

• A 37-year-old man who had refractory acute myeloid leukemia and was awaiting a matched, unrelated-donor transplant presents with a large purplish lesion on his fingertip, which he said began to appear during a game of baseball with his son. As an outpatient, he takes levofloxacin, fluconazole and acyclovir. A culture grows Gram-negative Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

"When you suspect a Gram-negative bacteremia in an immunocompromised patient, you can’t wait for a susceptibility test to come back," Dr. Zimmer said. "Start with whatever Gram-negative coverage is working best at your hospital." Although the literature doesn’t completely support the use of multiple drugs, "I often use double coverage because resistance is high in many hospitals, and getting it right the first time is really important. My main reason for doing this is to make sure that one of the two agents is going to be effective against this organism."

• A 39-year-old construction worker comes in with multiple injuries after an off-roading vehicle accident. On hospital day 7, he develops severe facial swelling and periorbital pain; imaging shows a periorbital abscess with extension toward the brain.

"This man had an invasive fungal zygomycosis," Dr. Zimmer said. "This often involves the nose, sinuses, and eye and can extend directly into the brain. Mortality is extremely high, around 80%."

In a case like this, start empirical therapy with a broad antifungal immediately, but the real answer for this problem is surgical debridement. "If they can’t get to the operating room, they need to go into hospice." Patients usually need multiple debridements, because the fungus can grow back on a daily basis.

Posaconazole has become the drug of choice over the last few years, but may be impractical for those with zygomycosis. "It can only be taken orally, and these patients often have a hard time swallowing. I usually start fluconazole and a lipid formulation of amphotericin. It takes awhile for posaconazole to reach good blood levels, and it should be administered with a fatty meal."

• A 25-year-old female student presents with a low-grade fever and bilateral facial palsy. Imaging shows inflammation of facial nerves.

"Bilateral facial palsies are very rare," Dr. Zimmer said. "There can be noninfective causes, but the most common infectious cause is Lyme disease."

In considering the differential diagnosis, the patient history, outdoor activities, and geography are all important. "If you’re looking at a young, otherwise healthy person who spends some time in the woods," where Lyme is endemic, then Lyme is a good bet, she noted.

A lumbar puncture that shows lymphocytes, in conjunction with a Western blot that is positive for Lyme "puts you in good shape" with a diagnosis. "Lyme antibody is very sensitive but not very specific."

Treatment of central nervous system Lyme "is a little bit controversial," Dr. Zimmer said. Most U.S. physicians use intravenous ceftriaxone or penicillin for 14 days. A 14-day course of oral doxycycline is also effective, but not as common in this country. "All the studies have been done in Europe, so U.S. physicians are somewhat reluctant to use this, but no studies have shown any difference between IV antibiotics and oral doxycycline."

Dr. Zimmer reported having no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOCIETY OF HOSPITAL MEDICINE

Give Infections and Antibiotics Their Due Respect

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – Respect. That is what it takes for the savvy hospitalist to pick a drug that’s safe for the patient and kills the bug.

Respect for both the pathogen and the drug that destroys it can make the difference between curing an infective illness and prescribing unnecessary treatment that can harm the patient.

Staphylococcus aureus, for example, can never be underestimated. "It never, ever ceases to amaze me in how virulent and aggressive it can be," Dr. Shanta Zimmer said at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

On the other hand, she said, physicians must remember the serious comorbidities patients can experience with multiple drug therapy, or even with a single antibiotic.

"Respect the drugs. We often do things to our patients that are harmful, giving them unnecessary therapy. We can’t commit a patient to a line of therapy that may or may not be warranted because we can’t say for sure that there is an infection," or what the infective agent is. "So, take your time. Do a repeat culture. In infectious disease, we often have time to think and get more data before we make a decision."

Dr. Zimmer, an infectious disease expert at the University of Pittsburgh, presented the following cases to illustrate her approach:

• A woman who is between chemotherapy cycles for breast cancer presents with fever and reports chills when the port is flushed. Blood cultures from both port and periphery grow Candida albicans; the port also grows coagulase-negative staphylococcus.

Decisions about her treatment depend not only on the organism, but also on the environment. "If you have a patient in a hospital area where you see a lot of Candida, consider a kinase inhibitor as the first line of therapy. If you don’t see that much in your facility, it’s okay to start with fluconazole as the first line."

A big advantage of these drugs is their high oral bioavailability. "You can give them orally and not have to send the patient home with a PICC [peripherally inserted central catheter] line."

Treatment should continue for 14 days past the first negative blood culture, but don’t rush the timeline with Candida, she warned. "This is something that can grow very slowly, so you have to wait longer than 48 hours to really determine if the culture is negative. Often I wait 3 or 4 days to make sure that culture is clear."

When possible, remove any infected line, but especially one infected with Candida. "For Candida and [S. aureus], always remove the line. Never try to leave it in for one of those [infections]," Dr. Simmer said. For other organisms, removing the line is still preferable. "I realize this is sometimes a difficult decision, but it makes your treatment regimen so much easier."

• A 62-year-old man who had a recent mitral valve repair presents with a fever, some gaze abnormalities, and altered mental status. A transthoracic echocardiogram shows a 1.6-cm vegetation on the valve, and an MRI showed a new occipital stroke. The blood culture grew Streptococcus viridans.

Alpha-hemolytic streptococcus is one of the most common causes of endocarditis. The pathogens react differently to penicillin, depending on the species and virulence factors. Although the patient needs immediate empirical therapy with a broad-spectrum antibiotic, "the key here is to check the minimum inhibitory concentration [MIC] for penicillin before you change" to something more specific, she said. "If the MIC for penicillin is low, use penicillin for 4 weeks, or penicillin plus gentamycin for 2 weeks. If the MIC is intermediate, you really need to do 4 weeks of penicillin and add gentamycin for the first 2 weeks. If it’s high, then you need an enterococcal regimen."

• A 37-year-old man who had refractory acute myeloid leukemia and was awaiting a matched, unrelated-donor transplant presents with a large purplish lesion on his fingertip, which he said began to appear during a game of baseball with his son. As an outpatient, he takes levofloxacin, fluconazole and acyclovir. A culture grows Gram-negative Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

"When you suspect a Gram-negative bacteremia in an immunocompromised patient, you can’t wait for a susceptibility test to come back," Dr. Zimmer said. "Start with whatever Gram-negative coverage is working best at your hospital." Although the literature doesn’t completely support the use of multiple drugs, "I often use double coverage because resistance is high in many hospitals, and getting it right the first time is really important. My main reason for doing this is to make sure that one of the two agents is going to be effective against this organism."

• A 39-year-old construction worker comes in with multiple injuries after an off-roading vehicle accident. On hospital day 7, he develops severe facial swelling and periorbital pain; imaging shows a periorbital abscess with extension toward the brain.

"This man had an invasive fungal zygomycosis," Dr. Zimmer said. "This often involves the nose, sinuses, and eye and can extend directly into the brain. Mortality is extremely high, around 80%."

In a case like this, start empirical therapy with a broad antifungal immediately, but the real answer for this problem is surgical debridement. "If they can’t get to the operating room, they need to go into hospice." Patients usually need multiple debridements, because the fungus can grow back on a daily basis.

Posaconazole has become the drug of choice over the last few years, but may be impractical for those with zygomycosis. "It can only be taken orally, and these patients often have a hard time swallowing. I usually start fluconazole and a lipid formulation of amphotericin. It takes awhile for posaconazole to reach good blood levels, and it should be administered with a fatty meal."

• A 25-year-old female student presents with a low-grade fever and bilateral facial palsy. Imaging shows inflammation of facial nerves.

"Bilateral facial palsies are very rare," Dr. Zimmer said. "There can be noninfective causes, but the most common infectious cause is Lyme disease."

In considering the differential diagnosis, the patient history, outdoor activities, and geography are all important. "If you’re looking at a young, otherwise healthy person who spends some time in the woods," where Lyme is endemic, then Lyme is a good bet, she noted.

A lumbar puncture that shows lymphocytes, in conjunction with a Western blot that is positive for Lyme "puts you in good shape" with a diagnosis. "Lyme antibody is very sensitive but not very specific."

Treatment of central nervous system Lyme "is a little bit controversial," Dr. Zimmer said. Most U.S. physicians use intravenous ceftriaxone or penicillin for 14 days. A 14-day course of oral doxycycline is also effective, but not as common in this country. "All the studies have been done in Europe, so U.S. physicians are somewhat reluctant to use this, but no studies have shown any difference between IV antibiotics and oral doxycycline."

Dr. Zimmer reported having no financial disclosures.

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – Respect. That is what it takes for the savvy hospitalist to pick a drug that’s safe for the patient and kills the bug.

Respect for both the pathogen and the drug that destroys it can make the difference between curing an infective illness and prescribing unnecessary treatment that can harm the patient.

Staphylococcus aureus, for example, can never be underestimated. "It never, ever ceases to amaze me in how virulent and aggressive it can be," Dr. Shanta Zimmer said at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

On the other hand, she said, physicians must remember the serious comorbidities patients can experience with multiple drug therapy, or even with a single antibiotic.

"Respect the drugs. We often do things to our patients that are harmful, giving them unnecessary therapy. We can’t commit a patient to a line of therapy that may or may not be warranted because we can’t say for sure that there is an infection," or what the infective agent is. "So, take your time. Do a repeat culture. In infectious disease, we often have time to think and get more data before we make a decision."

Dr. Zimmer, an infectious disease expert at the University of Pittsburgh, presented the following cases to illustrate her approach:

• A woman who is between chemotherapy cycles for breast cancer presents with fever and reports chills when the port is flushed. Blood cultures from both port and periphery grow Candida albicans; the port also grows coagulase-negative staphylococcus.

Decisions about her treatment depend not only on the organism, but also on the environment. "If you have a patient in a hospital area where you see a lot of Candida, consider a kinase inhibitor as the first line of therapy. If you don’t see that much in your facility, it’s okay to start with fluconazole as the first line."

A big advantage of these drugs is their high oral bioavailability. "You can give them orally and not have to send the patient home with a PICC [peripherally inserted central catheter] line."

Treatment should continue for 14 days past the first negative blood culture, but don’t rush the timeline with Candida, she warned. "This is something that can grow very slowly, so you have to wait longer than 48 hours to really determine if the culture is negative. Often I wait 3 or 4 days to make sure that culture is clear."

When possible, remove any infected line, but especially one infected with Candida. "For Candida and [S. aureus], always remove the line. Never try to leave it in for one of those [infections]," Dr. Simmer said. For other organisms, removing the line is still preferable. "I realize this is sometimes a difficult decision, but it makes your treatment regimen so much easier."

• A 62-year-old man who had a recent mitral valve repair presents with a fever, some gaze abnormalities, and altered mental status. A transthoracic echocardiogram shows a 1.6-cm vegetation on the valve, and an MRI showed a new occipital stroke. The blood culture grew Streptococcus viridans.

Alpha-hemolytic streptococcus is one of the most common causes of endocarditis. The pathogens react differently to penicillin, depending on the species and virulence factors. Although the patient needs immediate empirical therapy with a broad-spectrum antibiotic, "the key here is to check the minimum inhibitory concentration [MIC] for penicillin before you change" to something more specific, she said. "If the MIC for penicillin is low, use penicillin for 4 weeks, or penicillin plus gentamycin for 2 weeks. If the MIC is intermediate, you really need to do 4 weeks of penicillin and add gentamycin for the first 2 weeks. If it’s high, then you need an enterococcal regimen."

• A 37-year-old man who had refractory acute myeloid leukemia and was awaiting a matched, unrelated-donor transplant presents with a large purplish lesion on his fingertip, which he said began to appear during a game of baseball with his son. As an outpatient, he takes levofloxacin, fluconazole and acyclovir. A culture grows Gram-negative Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

"When you suspect a Gram-negative bacteremia in an immunocompromised patient, you can’t wait for a susceptibility test to come back," Dr. Zimmer said. "Start with whatever Gram-negative coverage is working best at your hospital." Although the literature doesn’t completely support the use of multiple drugs, "I often use double coverage because resistance is high in many hospitals, and getting it right the first time is really important. My main reason for doing this is to make sure that one of the two agents is going to be effective against this organism."

• A 39-year-old construction worker comes in with multiple injuries after an off-roading vehicle accident. On hospital day 7, he develops severe facial swelling and periorbital pain; imaging shows a periorbital abscess with extension toward the brain.

"This man had an invasive fungal zygomycosis," Dr. Zimmer said. "This often involves the nose, sinuses, and eye and can extend directly into the brain. Mortality is extremely high, around 80%."

In a case like this, start empirical therapy with a broad antifungal immediately, but the real answer for this problem is surgical debridement. "If they can’t get to the operating room, they need to go into hospice." Patients usually need multiple debridements, because the fungus can grow back on a daily basis.

Posaconazole has become the drug of choice over the last few years, but may be impractical for those with zygomycosis. "It can only be taken orally, and these patients often have a hard time swallowing. I usually start fluconazole and a lipid formulation of amphotericin. It takes awhile for posaconazole to reach good blood levels, and it should be administered with a fatty meal."

• A 25-year-old female student presents with a low-grade fever and bilateral facial palsy. Imaging shows inflammation of facial nerves.

"Bilateral facial palsies are very rare," Dr. Zimmer said. "There can be noninfective causes, but the most common infectious cause is Lyme disease."

In considering the differential diagnosis, the patient history, outdoor activities, and geography are all important. "If you’re looking at a young, otherwise healthy person who spends some time in the woods," where Lyme is endemic, then Lyme is a good bet, she noted.

A lumbar puncture that shows lymphocytes, in conjunction with a Western blot that is positive for Lyme "puts you in good shape" with a diagnosis. "Lyme antibody is very sensitive but not very specific."

Treatment of central nervous system Lyme "is a little bit controversial," Dr. Zimmer said. Most U.S. physicians use intravenous ceftriaxone or penicillin for 14 days. A 14-day course of oral doxycycline is also effective, but not as common in this country. "All the studies have been done in Europe, so U.S. physicians are somewhat reluctant to use this, but no studies have shown any difference between IV antibiotics and oral doxycycline."

Dr. Zimmer reported having no financial disclosures.

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – Respect. That is what it takes for the savvy hospitalist to pick a drug that’s safe for the patient and kills the bug.

Respect for both the pathogen and the drug that destroys it can make the difference between curing an infective illness and prescribing unnecessary treatment that can harm the patient.

Staphylococcus aureus, for example, can never be underestimated. "It never, ever ceases to amaze me in how virulent and aggressive it can be," Dr. Shanta Zimmer said at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

On the other hand, she said, physicians must remember the serious comorbidities patients can experience with multiple drug therapy, or even with a single antibiotic.

"Respect the drugs. We often do things to our patients that are harmful, giving them unnecessary therapy. We can’t commit a patient to a line of therapy that may or may not be warranted because we can’t say for sure that there is an infection," or what the infective agent is. "So, take your time. Do a repeat culture. In infectious disease, we often have time to think and get more data before we make a decision."

Dr. Zimmer, an infectious disease expert at the University of Pittsburgh, presented the following cases to illustrate her approach:

• A woman who is between chemotherapy cycles for breast cancer presents with fever and reports chills when the port is flushed. Blood cultures from both port and periphery grow Candida albicans; the port also grows coagulase-negative staphylococcus.

Decisions about her treatment depend not only on the organism, but also on the environment. "If you have a patient in a hospital area where you see a lot of Candida, consider a kinase inhibitor as the first line of therapy. If you don’t see that much in your facility, it’s okay to start with fluconazole as the first line."

A big advantage of these drugs is their high oral bioavailability. "You can give them orally and not have to send the patient home with a PICC [peripherally inserted central catheter] line."

Treatment should continue for 14 days past the first negative blood culture, but don’t rush the timeline with Candida, she warned. "This is something that can grow very slowly, so you have to wait longer than 48 hours to really determine if the culture is negative. Often I wait 3 or 4 days to make sure that culture is clear."

When possible, remove any infected line, but especially one infected with Candida. "For Candida and [S. aureus], always remove the line. Never try to leave it in for one of those [infections]," Dr. Simmer said. For other organisms, removing the line is still preferable. "I realize this is sometimes a difficult decision, but it makes your treatment regimen so much easier."

• A 62-year-old man who had a recent mitral valve repair presents with a fever, some gaze abnormalities, and altered mental status. A transthoracic echocardiogram shows a 1.6-cm vegetation on the valve, and an MRI showed a new occipital stroke. The blood culture grew Streptococcus viridans.

Alpha-hemolytic streptococcus is one of the most common causes of endocarditis. The pathogens react differently to penicillin, depending on the species and virulence factors. Although the patient needs immediate empirical therapy with a broad-spectrum antibiotic, "the key here is to check the minimum inhibitory concentration [MIC] for penicillin before you change" to something more specific, she said. "If the MIC for penicillin is low, use penicillin for 4 weeks, or penicillin plus gentamycin for 2 weeks. If the MIC is intermediate, you really need to do 4 weeks of penicillin and add gentamycin for the first 2 weeks. If it’s high, then you need an enterococcal regimen."

• A 37-year-old man who had refractory acute myeloid leukemia and was awaiting a matched, unrelated-donor transplant presents with a large purplish lesion on his fingertip, which he said began to appear during a game of baseball with his son. As an outpatient, he takes levofloxacin, fluconazole and acyclovir. A culture grows Gram-negative Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

"When you suspect a Gram-negative bacteremia in an immunocompromised patient, you can’t wait for a susceptibility test to come back," Dr. Zimmer said. "Start with whatever Gram-negative coverage is working best at your hospital." Although the literature doesn’t completely support the use of multiple drugs, "I often use double coverage because resistance is high in many hospitals, and getting it right the first time is really important. My main reason for doing this is to make sure that one of the two agents is going to be effective against this organism."

• A 39-year-old construction worker comes in with multiple injuries after an off-roading vehicle accident. On hospital day 7, he develops severe facial swelling and periorbital pain; imaging shows a periorbital abscess with extension toward the brain.

"This man had an invasive fungal zygomycosis," Dr. Zimmer said. "This often involves the nose, sinuses, and eye and can extend directly into the brain. Mortality is extremely high, around 80%."

In a case like this, start empirical therapy with a broad antifungal immediately, but the real answer for this problem is surgical debridement. "If they can’t get to the operating room, they need to go into hospice." Patients usually need multiple debridements, because the fungus can grow back on a daily basis.

Posaconazole has become the drug of choice over the last few years, but may be impractical for those with zygomycosis. "It can only be taken orally, and these patients often have a hard time swallowing. I usually start fluconazole and a lipid formulation of amphotericin. It takes awhile for posaconazole to reach good blood levels, and it should be administered with a fatty meal."

• A 25-year-old female student presents with a low-grade fever and bilateral facial palsy. Imaging shows inflammation of facial nerves.

"Bilateral facial palsies are very rare," Dr. Zimmer said. "There can be noninfective causes, but the most common infectious cause is Lyme disease."

In considering the differential diagnosis, the patient history, outdoor activities, and geography are all important. "If you’re looking at a young, otherwise healthy person who spends some time in the woods," where Lyme is endemic, then Lyme is a good bet, she noted.

A lumbar puncture that shows lymphocytes, in conjunction with a Western blot that is positive for Lyme "puts you in good shape" with a diagnosis. "Lyme antibody is very sensitive but not very specific."

Treatment of central nervous system Lyme "is a little bit controversial," Dr. Zimmer said. Most U.S. physicians use intravenous ceftriaxone or penicillin for 14 days. A 14-day course of oral doxycycline is also effective, but not as common in this country. "All the studies have been done in Europe, so U.S. physicians are somewhat reluctant to use this, but no studies have shown any difference between IV antibiotics and oral doxycycline."

Dr. Zimmer reported having no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOCIETY OF HOSPITAL MEDICINE

Hospitalists Perform Well on Fluid Retrieval Procedures

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – Hospitalists can safely perform fluid retrieval procedures with a high rate of success and no patient complications, according to the findings of a retrospective study.

A hospitalist procedure team had an overall success rate of 92% among 977 thoracenteses, paracenteses, and lumbar punctures that were performed over a 2-year period, Dr. Michelle Mourad reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine. The results suggest that additional training can boost hospitalists’ success rates to nearly that of the subspecialists who routinely perform these procedures.

"Unfortunately, many hospitalists lack formal training in procedure skills because training during residency is decreasing," said Dr. Mourad, a hospitalist at the University of California, San Francisco. "We are graduating hospitalists without these skills and having to refer procedures to subspecialties and interventional radiology."

Having hospitalists who are competent in procedures "is becoming more important because advanced technologies like bedside ultrasounds are rapidly becoming the standard of care."

Dr. Mourad and her colleagues examined their database over a 2-year period to determine the success rate of the three common procedures. Aside from success or failure, the outcomes took into account patient characteristics that might contribute to the lack of success and any patient outcomes that were related to unsuccessful procedures.

The hospitalist procedure service at Dr. Mourad’s institution began in 2008 and includes five physicians who obtained additional procedure skills from emergency physicians and interventional radiologists.

Over the 2-year period, the team performed 977 of these procedures (408 paracenteses, 279 thoracenteses, and 290 lumbar punctures). Nonsuccess was defined as the failure to obtain adequate fluid despite several needle passes.

The failure rate among paracenteses was 1%. All four of the unsuccessful procedures had ultrasound corroboration of fluid. "All of these patients also had an abdominal wall greater than 5 cm," Dr. Mourad said. "None sustained any complications," nor were any of these patients referred to another provider. All were treated empirically for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

Among the thoracenteses, 6% were unsuccessful. A CT scan corroborated the presence of more than 2 cm of fluid in each of the 16 cases. In all, 10 of the 16 patients had malignant effusions and 50% had pleural thickening. "We suspect that the pleural thickening" may have caused the procedures to be prematurely aborted "because the fluid was deeper than anticipated," Dr. Mourad said.

Nine patients were referred to interventional radiology and, although all radiologists agreed that the procedure was possible, they were unable to obtain fluid in three patients. "Of the six that were completed, three were more complicated than initially thought. Interventional radiology had to use CT guidance to complete the procedure." None of the failures resulted in any patient complications.

The largest failure rate occurred among the lumbar punctures, in which 19% (56) were unsuccessful. Most of the patients with unsuccessful procedures were overweight or obese, Dr. Mourad said; 53% had a body mass index of more than 25 kg/m2 and 36% had a BMI of more than 30. "We need to compare this to our total population of procedures to determine if BMI is a true risk factor or not," she said.

Of the unsuccessful procedures, 28 were referred to neuroradiology, where they were all successfully completed, although some required CT guidance. There were no complications among any of the patients with a failed procedure.

The findings have prompted some changes in the way procedures are managed, Dr. Mourad said. "For instance, for paracentesis we now routinely measure the abdominal wall thickness, and we have [a larger] range of needles available because we know that the problems of not getting fluid are often a problem of needle length."

Dr. Mourad reported having no conflicts of interest.

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – Hospitalists can safely perform fluid retrieval procedures with a high rate of success and no patient complications, according to the findings of a retrospective study.

A hospitalist procedure team had an overall success rate of 92% among 977 thoracenteses, paracenteses, and lumbar punctures that were performed over a 2-year period, Dr. Michelle Mourad reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine. The results suggest that additional training can boost hospitalists’ success rates to nearly that of the subspecialists who routinely perform these procedures.

"Unfortunately, many hospitalists lack formal training in procedure skills because training during residency is decreasing," said Dr. Mourad, a hospitalist at the University of California, San Francisco. "We are graduating hospitalists without these skills and having to refer procedures to subspecialties and interventional radiology."

Having hospitalists who are competent in procedures "is becoming more important because advanced technologies like bedside ultrasounds are rapidly becoming the standard of care."

Dr. Mourad and her colleagues examined their database over a 2-year period to determine the success rate of the three common procedures. Aside from success or failure, the outcomes took into account patient characteristics that might contribute to the lack of success and any patient outcomes that were related to unsuccessful procedures.

The hospitalist procedure service at Dr. Mourad’s institution began in 2008 and includes five physicians who obtained additional procedure skills from emergency physicians and interventional radiologists.

Over the 2-year period, the team performed 977 of these procedures (408 paracenteses, 279 thoracenteses, and 290 lumbar punctures). Nonsuccess was defined as the failure to obtain adequate fluid despite several needle passes.

The failure rate among paracenteses was 1%. All four of the unsuccessful procedures had ultrasound corroboration of fluid. "All of these patients also had an abdominal wall greater than 5 cm," Dr. Mourad said. "None sustained any complications," nor were any of these patients referred to another provider. All were treated empirically for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

Among the thoracenteses, 6% were unsuccessful. A CT scan corroborated the presence of more than 2 cm of fluid in each of the 16 cases. In all, 10 of the 16 patients had malignant effusions and 50% had pleural thickening. "We suspect that the pleural thickening" may have caused the procedures to be prematurely aborted "because the fluid was deeper than anticipated," Dr. Mourad said.

Nine patients were referred to interventional radiology and, although all radiologists agreed that the procedure was possible, they were unable to obtain fluid in three patients. "Of the six that were completed, three were more complicated than initially thought. Interventional radiology had to use CT guidance to complete the procedure." None of the failures resulted in any patient complications.

The largest failure rate occurred among the lumbar punctures, in which 19% (56) were unsuccessful. Most of the patients with unsuccessful procedures were overweight or obese, Dr. Mourad said; 53% had a body mass index of more than 25 kg/m2 and 36% had a BMI of more than 30. "We need to compare this to our total population of procedures to determine if BMI is a true risk factor or not," she said.

Of the unsuccessful procedures, 28 were referred to neuroradiology, where they were all successfully completed, although some required CT guidance. There were no complications among any of the patients with a failed procedure.

The findings have prompted some changes in the way procedures are managed, Dr. Mourad said. "For instance, for paracentesis we now routinely measure the abdominal wall thickness, and we have [a larger] range of needles available because we know that the problems of not getting fluid are often a problem of needle length."

Dr. Mourad reported having no conflicts of interest.

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – Hospitalists can safely perform fluid retrieval procedures with a high rate of success and no patient complications, according to the findings of a retrospective study.

A hospitalist procedure team had an overall success rate of 92% among 977 thoracenteses, paracenteses, and lumbar punctures that were performed over a 2-year period, Dr. Michelle Mourad reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine. The results suggest that additional training can boost hospitalists’ success rates to nearly that of the subspecialists who routinely perform these procedures.

"Unfortunately, many hospitalists lack formal training in procedure skills because training during residency is decreasing," said Dr. Mourad, a hospitalist at the University of California, San Francisco. "We are graduating hospitalists without these skills and having to refer procedures to subspecialties and interventional radiology."

Having hospitalists who are competent in procedures "is becoming more important because advanced technologies like bedside ultrasounds are rapidly becoming the standard of care."

Dr. Mourad and her colleagues examined their database over a 2-year period to determine the success rate of the three common procedures. Aside from success or failure, the outcomes took into account patient characteristics that might contribute to the lack of success and any patient outcomes that were related to unsuccessful procedures.

The hospitalist procedure service at Dr. Mourad’s institution began in 2008 and includes five physicians who obtained additional procedure skills from emergency physicians and interventional radiologists.

Over the 2-year period, the team performed 977 of these procedures (408 paracenteses, 279 thoracenteses, and 290 lumbar punctures). Nonsuccess was defined as the failure to obtain adequate fluid despite several needle passes.

The failure rate among paracenteses was 1%. All four of the unsuccessful procedures had ultrasound corroboration of fluid. "All of these patients also had an abdominal wall greater than 5 cm," Dr. Mourad said. "None sustained any complications," nor were any of these patients referred to another provider. All were treated empirically for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

Among the thoracenteses, 6% were unsuccessful. A CT scan corroborated the presence of more than 2 cm of fluid in each of the 16 cases. In all, 10 of the 16 patients had malignant effusions and 50% had pleural thickening. "We suspect that the pleural thickening" may have caused the procedures to be prematurely aborted "because the fluid was deeper than anticipated," Dr. Mourad said.

Nine patients were referred to interventional radiology and, although all radiologists agreed that the procedure was possible, they were unable to obtain fluid in three patients. "Of the six that were completed, three were more complicated than initially thought. Interventional radiology had to use CT guidance to complete the procedure." None of the failures resulted in any patient complications.

The largest failure rate occurred among the lumbar punctures, in which 19% (56) were unsuccessful. Most of the patients with unsuccessful procedures were overweight or obese, Dr. Mourad said; 53% had a body mass index of more than 25 kg/m2 and 36% had a BMI of more than 30. "We need to compare this to our total population of procedures to determine if BMI is a true risk factor or not," she said.

Of the unsuccessful procedures, 28 were referred to neuroradiology, where they were all successfully completed, although some required CT guidance. There were no complications among any of the patients with a failed procedure.

The findings have prompted some changes in the way procedures are managed, Dr. Mourad said. "For instance, for paracentesis we now routinely measure the abdominal wall thickness, and we have [a larger] range of needles available because we know that the problems of not getting fluid are often a problem of needle length."

Dr. Mourad reported having no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOCIETY OF HOSPITAL MEDICINE

Study: Seeing Price Tag on Lab Tests Affects Ordering

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – Policy makers are scrambling for ways to bring down health care spending, but what if it were as simple as telling physicians how much things cost?

A new study by investigators at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, which looks at the impact of displaying cost data on laboratory tests, shows that physicians' behavior is affected by seeing the price of the tests they order.

To see how having cost data at the time of order entry would affect behavior, researchers at Johns Hopkins compiled a list of both the most frequently ordered and the most expensive laboratory tests in their hospital, based on 2007 data.

Costly tests were only included in the study if they were ordered at least 50 times during the year. The researchers then randomized the tests to be either active tests or concurrent controls. For active tests, the researchers displayed the price, based on 2008 Medicare allowable cost figures, on the hospital's computerized provider order entry (CPOE) system. For example, a blood gas was listed at $28.25 and a heme-8 lab was $9.37.

Results

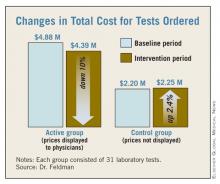

During the 6-month intervention period from November 2009 to May 2010, there was a mean decrease of about $15,692 per test for the lab tests in which cost data was displayed in the CPOE, compared with a baseline period exactly 1 year earlier.

For all 31 of the active tests, there was a combined decrease of about $486,000, resulting in a 10% reduction among tests in which the costs were displayed. The active test costs dropped from $4,877,439 to $4,390,979. Among the group of 31 control tests, in which cost information was not listed on the CPOE, there was a mean increase of $1,718 per test. Overall, costs for the control group went up about $53,000 for all 31 tests.

The total number of tests ordered in the active group fell from 458,518 during the baseline period to 417,078 during the intervention. But in the control group, the number of tests rose from 142,196 to 149,455 during the study period.

Investigator Doesn't Find Results Surprising

Dr. Leonard Feldman, one of the study investigators and who is in the department of medicine at Johns Hopkins, said the results did not come as a surprise.

"I think many of us do recognize that a lot of these tests and imaging studies that are done are unnecessary," Dr. Feldman said during the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Physicians order unnecessary tests for a number of reasons, he said, ranging from defensive medicine to patient expectations. But another reason is a lack of awareness of how much the tests cost, he said. "We, as doctors, have a limited understanding of diagnostic and nondrug therapeutic costs," Dr. Feldman said. "We just have no idea, mostly, how much things cost when we go to order them."

Study Limitations

While the study appears to show a relatively simple and inexpensive way to reduce the ordering of tests, Dr. Feldman acknowledged that the study had some limitations. For example, the study looked at only costs and did not include data on how the change in orders might have affected patient outcomes. And the intervention period was only 6 months.

Dr. Feldman said more time would be needed to show whether physicians would begin to ignore the costs over time. Similarly, costs were only displayed for 31 tests during the study. It's unclear if displaying all laboratory test costs would have the same effect on behavior, Dr. Feldman said.

The authors reported no financial disclosures.

In invited commentary, Dr. Franklin A. Michota said

that “Dr. Leonard Feldman and his colleagues at Johns Hopkins

Hospital have recently

demonstrated that cost visibility for health care providers can decrease

resource utilization. They are cautious to limit their findings to several

specific laboratory tests; however, this simple approach has widespread

applicability beyond laboratory testing and has the potential for great cost

savings across the U.S.

health care system. But before we start putting visible price tags on all of

our hospital order sheets, products, and medications, we should review what we

really know about cost visibility and the risk for adverse consequences”

according to Dr. Michota, director of academic affairs in the department of

hospital medicine at the Cleveland Clinic.

“Dr. Feldman readily

admits that patient outcomes were not reviewed in their preliminary study. It

certainly seems plausible that cost visibility reduced the ordering of

redundant and unnecessary laboratory tests. It is also plausible that necessary

and appropriate testing was omitted because of concerns over cost. We cannot

and should not look at a reduction in resource utilization with a smile on our

face without confirming at least a neutral effect on patient outcome” said Dr.

Michota.

“To that end, we must

also consider the spectrum of patient outcome and how we as individual

providers factor cost into medical decision making. There are many outcomes in

patient care, including patient satisfaction and comfort. Which outcomes should

matter the most? From which perspective do we apply our cost thresholds?

“I have often said

that I have yet to meet an American who isn’t willing to have an infinite

amount of money spent on them for the smallest improvement in outcome. How

should physicians weigh the various outcomes in balance with the visible cost?

One particular danger is the effect of physician experience on the benefit/cost

equation. Cost visibility puts the cost data right in front of the physician in

real time, yet there is no ‘equal display’ regarding the benefits. It stands to

reason that if the physician is unaware of the benefits due to lack of

experience, the medical decision making will be inappropriately weighted toward

the cost,” Dr. Michota said.

“Finally, there is

also an inherent injustice to applying cost-based decisions at the individual

patient level which is the basis of the cost-visibility approach. Most patients

are randomly assigned to hospitalists. Despite identical presentations, one

patient could receive less ‘care’ (such as testing, therapies, resources) because

his or her physician weighted the visible cost of care differently than did the

physician caring for the patient in the next bed. To avoid this conflict,

bioethicists recommend that cost-based decisions be made at the population, not

the individual level. Hospital formularies are a good example of this

technique. Cost visibility applied to individual patients without standardized

approaches on how to use the information consistently across all patients could

otherwise be considered unethical,” he said.

“Ultimately,

hospitalists should strive for value (quality/cost) in health care. As patient

advocates, we need to make sure that the quality is just as visible as the

cost,” according to Dr. Michota.

Dr. Franklin A. Michota, director of academic affairs in the department of

hospital medicine at the Cleveland Clinic. He declared no relevant financial disclosures.

In invited commentary, Dr. Franklin A. Michota said

that “Dr. Leonard Feldman and his colleagues at Johns Hopkins

Hospital have recently

demonstrated that cost visibility for health care providers can decrease

resource utilization. They are cautious to limit their findings to several

specific laboratory tests; however, this simple approach has widespread

applicability beyond laboratory testing and has the potential for great cost

savings across the U.S.

health care system. But before we start putting visible price tags on all of

our hospital order sheets, products, and medications, we should review what we

really know about cost visibility and the risk for adverse consequences”

according to Dr. Michota, director of academic affairs in the department of

hospital medicine at the Cleveland Clinic.

“Dr. Feldman readily

admits that patient outcomes were not reviewed in their preliminary study. It

certainly seems plausible that cost visibility reduced the ordering of

redundant and unnecessary laboratory tests. It is also plausible that necessary

and appropriate testing was omitted because of concerns over cost. We cannot

and should not look at a reduction in resource utilization with a smile on our

face without confirming at least a neutral effect on patient outcome” said Dr.

Michota.

“To that end, we must

also consider the spectrum of patient outcome and how we as individual

providers factor cost into medical decision making. There are many outcomes in

patient care, including patient satisfaction and comfort. Which outcomes should

matter the most? From which perspective do we apply our cost thresholds?

“I have often said

that I have yet to meet an American who isn’t willing to have an infinite

amount of money spent on them for the smallest improvement in outcome. How