User login

The Prediabetes Debate: Should the Diabetes Diagnostic Threshold Be Lowered, Allowing Clinicians to Intervene Earlier?

I believe that the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) should be broadened to match the glycemic thresholds currently used for prediabetes. This would eliminate the need for a separate category, the “prediabetes” nomenclature, and allow for earlier therapeutic intervention in patients. Current diabetes diagnostic thresholds do not reflect the latest advancements in T2DM understanding. The latest in T2DM research suggests that intervening and treating prediabetes earlier could potentially offer better clinical outcomes and enhance patients’ quality of life, as cell and tissue damage occurs early and leads to dysfunction prior to a diabetes diagnosis.1 T2DM is a highly complex disease with multifactorial causes beyond hyperglycemia that should be considered, such as hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, and autoimmune inflammatory mechanisms that lead to β-cell dysfunction or failure, which results in hyperglycemia.

Prediabetes is associated with micro- and macrovascular complications that can occur early in the progression to frank disease state.1,2 This phase of diabetes also includes insulin resistance, impaired incretin action, insulin hypersecretion, increased lipolysis, and ectopic lipid storage—all of which damage β cells. These dysfunctions are also present in the frank diabetic disease state.3,4 Furthermore, diabetic retinopathy occurs in 8% to 12% of patients with prediabetes, and retinopathy begins earlier than previously thought, with neuroinflammation occurring even before vascular damage.5,6 Unfortunately, these neuro-inflammatory lesions cannot be detected with the typical instruments used in an ophthalmologist’s office.

It is believed that, through the principle of metabolic memory, even a moderate increase or episodic spikes in blood glucose can lead to negative effects in prediabetic patients who are susceptible to T2DM.1,5 Therefore, a lower diabetes diagnostic threshold could allow for earlier, more precise, and personalized therapies based on each patient’s individual risk factors and biomarkers. With a diagnosis of T2DM at the current prediabetes threshold, patients could receive treatment covered by health insurance while in the “prediabetic” state—treatment that would not have been previously approved. Patients should be treated earlier and on an individual basis with counseling on diet and lifestyle changes and antidiabetic agents to reduce glycemic levels, preserve β cells, and reduce cardiovascular [CV] or renal risk, among other complications.6,7

Moreover, the newer agents for treating diabetes such as glucagon-like pepetide-1 receptor agonists and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, which are also associated with reduction in adverse CV and/or renal outcomes, could be beneficial if administered early in the prediabetic stage of disease.8,9

Early lifestyle and pharmacologic interventions can reduce the rate of progression from prediabetes to diabetes as well as complications and associated conditions, and even potentially result in remission or a full reversal of diabetes. These “side benefits” of lowering the diabetes diagnostic threshold (over and above glycemic control) make any cost-effectiveness calculations all the more advantageous to individual patients as well as to society.

Given the numerous benefits of earlier intervention for diabetes treatment, I believe a call to re-evaluate the current diabetes diagnostic threshold is in order, as it will do a great service for all patients who are currently at risk for developing T2DM.

Armato JP, DeFronzo RA, Abdul-Ghani M, Ruby RJ. Successful treatment of prediabetes in clinical practice using physiological assessment (STOP DIABETES). Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:781-789.

Schwartz SS, Epstein S, Corkey BE, et al. A unified pathophysiological construct of diabetes and its complications. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2017;28:645-655.

American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes – 2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(S15–S39):S111-S124.

Brannick B, Wynn A, Dagogo-Jack S. Prediabetes as a toxic environment for the initiation of microvascular and macrovascular complications. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2016;241:1323-1331.

Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1183-1197.

Sinclair SH, Schwartz SS. Diabetic retinopathy–an underdiagnosed and undertreated inflammatory, neuro-vascular complication of diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:843.

Edwards CM, Cusi K. Prediabetes: a worldwide epidemic. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2016;45:751-764.

Kanat M, DeFronzo RA, Abdul-Ghani MA. Treatment of prediabetes. World J Diabetes. 2015;6:1207-1222.

Dankner R, Roth J. The personalized approach for detecting prediabetes and diabetes. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2016;12:58-65.

I believe that the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) should be broadened to match the glycemic thresholds currently used for prediabetes. This would eliminate the need for a separate category, the “prediabetes” nomenclature, and allow for earlier therapeutic intervention in patients. Current diabetes diagnostic thresholds do not reflect the latest advancements in T2DM understanding. The latest in T2DM research suggests that intervening and treating prediabetes earlier could potentially offer better clinical outcomes and enhance patients’ quality of life, as cell and tissue damage occurs early and leads to dysfunction prior to a diabetes diagnosis.1 T2DM is a highly complex disease with multifactorial causes beyond hyperglycemia that should be considered, such as hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, and autoimmune inflammatory mechanisms that lead to β-cell dysfunction or failure, which results in hyperglycemia.

Prediabetes is associated with micro- and macrovascular complications that can occur early in the progression to frank disease state.1,2 This phase of diabetes also includes insulin resistance, impaired incretin action, insulin hypersecretion, increased lipolysis, and ectopic lipid storage—all of which damage β cells. These dysfunctions are also present in the frank diabetic disease state.3,4 Furthermore, diabetic retinopathy occurs in 8% to 12% of patients with prediabetes, and retinopathy begins earlier than previously thought, with neuroinflammation occurring even before vascular damage.5,6 Unfortunately, these neuro-inflammatory lesions cannot be detected with the typical instruments used in an ophthalmologist’s office.

It is believed that, through the principle of metabolic memory, even a moderate increase or episodic spikes in blood glucose can lead to negative effects in prediabetic patients who are susceptible to T2DM.1,5 Therefore, a lower diabetes diagnostic threshold could allow for earlier, more precise, and personalized therapies based on each patient’s individual risk factors and biomarkers. With a diagnosis of T2DM at the current prediabetes threshold, patients could receive treatment covered by health insurance while in the “prediabetic” state—treatment that would not have been previously approved. Patients should be treated earlier and on an individual basis with counseling on diet and lifestyle changes and antidiabetic agents to reduce glycemic levels, preserve β cells, and reduce cardiovascular [CV] or renal risk, among other complications.6,7

Moreover, the newer agents for treating diabetes such as glucagon-like pepetide-1 receptor agonists and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, which are also associated with reduction in adverse CV and/or renal outcomes, could be beneficial if administered early in the prediabetic stage of disease.8,9

Early lifestyle and pharmacologic interventions can reduce the rate of progression from prediabetes to diabetes as well as complications and associated conditions, and even potentially result in remission or a full reversal of diabetes. These “side benefits” of lowering the diabetes diagnostic threshold (over and above glycemic control) make any cost-effectiveness calculations all the more advantageous to individual patients as well as to society.

Given the numerous benefits of earlier intervention for diabetes treatment, I believe a call to re-evaluate the current diabetes diagnostic threshold is in order, as it will do a great service for all patients who are currently at risk for developing T2DM.

I believe that the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) should be broadened to match the glycemic thresholds currently used for prediabetes. This would eliminate the need for a separate category, the “prediabetes” nomenclature, and allow for earlier therapeutic intervention in patients. Current diabetes diagnostic thresholds do not reflect the latest advancements in T2DM understanding. The latest in T2DM research suggests that intervening and treating prediabetes earlier could potentially offer better clinical outcomes and enhance patients’ quality of life, as cell and tissue damage occurs early and leads to dysfunction prior to a diabetes diagnosis.1 T2DM is a highly complex disease with multifactorial causes beyond hyperglycemia that should be considered, such as hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, and autoimmune inflammatory mechanisms that lead to β-cell dysfunction or failure, which results in hyperglycemia.

Prediabetes is associated with micro- and macrovascular complications that can occur early in the progression to frank disease state.1,2 This phase of diabetes also includes insulin resistance, impaired incretin action, insulin hypersecretion, increased lipolysis, and ectopic lipid storage—all of which damage β cells. These dysfunctions are also present in the frank diabetic disease state.3,4 Furthermore, diabetic retinopathy occurs in 8% to 12% of patients with prediabetes, and retinopathy begins earlier than previously thought, with neuroinflammation occurring even before vascular damage.5,6 Unfortunately, these neuro-inflammatory lesions cannot be detected with the typical instruments used in an ophthalmologist’s office.

It is believed that, through the principle of metabolic memory, even a moderate increase or episodic spikes in blood glucose can lead to negative effects in prediabetic patients who are susceptible to T2DM.1,5 Therefore, a lower diabetes diagnostic threshold could allow for earlier, more precise, and personalized therapies based on each patient’s individual risk factors and biomarkers. With a diagnosis of T2DM at the current prediabetes threshold, patients could receive treatment covered by health insurance while in the “prediabetic” state—treatment that would not have been previously approved. Patients should be treated earlier and on an individual basis with counseling on diet and lifestyle changes and antidiabetic agents to reduce glycemic levels, preserve β cells, and reduce cardiovascular [CV] or renal risk, among other complications.6,7

Moreover, the newer agents for treating diabetes such as glucagon-like pepetide-1 receptor agonists and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, which are also associated with reduction in adverse CV and/or renal outcomes, could be beneficial if administered early in the prediabetic stage of disease.8,9

Early lifestyle and pharmacologic interventions can reduce the rate of progression from prediabetes to diabetes as well as complications and associated conditions, and even potentially result in remission or a full reversal of diabetes. These “side benefits” of lowering the diabetes diagnostic threshold (over and above glycemic control) make any cost-effectiveness calculations all the more advantageous to individual patients as well as to society.

Given the numerous benefits of earlier intervention for diabetes treatment, I believe a call to re-evaluate the current diabetes diagnostic threshold is in order, as it will do a great service for all patients who are currently at risk for developing T2DM.

Armato JP, DeFronzo RA, Abdul-Ghani M, Ruby RJ. Successful treatment of prediabetes in clinical practice using physiological assessment (STOP DIABETES). Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:781-789.

Schwartz SS, Epstein S, Corkey BE, et al. A unified pathophysiological construct of diabetes and its complications. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2017;28:645-655.

American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes – 2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(S15–S39):S111-S124.

Brannick B, Wynn A, Dagogo-Jack S. Prediabetes as a toxic environment for the initiation of microvascular and macrovascular complications. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2016;241:1323-1331.

Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1183-1197.

Sinclair SH, Schwartz SS. Diabetic retinopathy–an underdiagnosed and undertreated inflammatory, neuro-vascular complication of diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:843.

Edwards CM, Cusi K. Prediabetes: a worldwide epidemic. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2016;45:751-764.

Kanat M, DeFronzo RA, Abdul-Ghani MA. Treatment of prediabetes. World J Diabetes. 2015;6:1207-1222.

Dankner R, Roth J. The personalized approach for detecting prediabetes and diabetes. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2016;12:58-65.

Armato JP, DeFronzo RA, Abdul-Ghani M, Ruby RJ. Successful treatment of prediabetes in clinical practice using physiological assessment (STOP DIABETES). Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:781-789.

Schwartz SS, Epstein S, Corkey BE, et al. A unified pathophysiological construct of diabetes and its complications. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2017;28:645-655.

American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes – 2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(S15–S39):S111-S124.

Brannick B, Wynn A, Dagogo-Jack S. Prediabetes as a toxic environment for the initiation of microvascular and macrovascular complications. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2016;241:1323-1331.

Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1183-1197.

Sinclair SH, Schwartz SS. Diabetic retinopathy–an underdiagnosed and undertreated inflammatory, neuro-vascular complication of diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:843.

Edwards CM, Cusi K. Prediabetes: a worldwide epidemic. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2016;45:751-764.

Kanat M, DeFronzo RA, Abdul-Ghani MA. Treatment of prediabetes. World J Diabetes. 2015;6:1207-1222.

Dankner R, Roth J. The personalized approach for detecting prediabetes and diabetes. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2016;12:58-65.

Green Mediterranean diet may relieve aortic stiffness

A green adaptation to the traditional Mediterranean diet improves proximal aortic stiffness (PAS), a distinct marker of vascular aging and increased cardiovascular risk, according to an exploratory post hoc analysis of the DIRECT-PLUS randomized clinical trial.

The green Mediterranean diet is distinct from the traditional Mediterranean diet because of its more abundant dietary polyphenols, from green tea and a Wolffia globosa (Mankai) plant green shake, and lower intake of red or processed meat.

Independent of weight loss, the modified green Mediterranean diet regressed PAS by 15%, the traditional Mediterranean diet by 7.3%, and the healthy dietary guideline–based diet by 4.8%, the study team observed.

“The DIRECT-PLUS trial research team was the first to introduce the concept of the green-Mediterranean/high polyphenols diet,” lead researcher Iris Shai, RD, PhD, with Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Be’er-Sheva, Israel, told this news organization.

This diet promoted “dramatic proximal aortic de-stiffening” as assessed by MRI over 18 months in roughly 300 participants with abdominal obesity/dyslipidemia. “To date, no dietary strategies have been shown to impact vascular aging physiology,” Dr. Shai said.

The analysis was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Not all healthy diets are equal

Of the 294 participants, 281 had valid PAS measurements at baseline. The baseline PAS (6.1 m/s) was similar across intervention groups (P = .20). Increased PAS was associated with aging, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and visceral adiposity (P < .05).

After 18 months’ intervention (retention rate 89.8%), all diet groups showed significant PAS reductions: –0.05 m/s with the standard healthy diet (4.8%), –0.08 m/s with the traditional Mediterranean diet (7.3%) and –0.15 the green Mediterranean diet (15%).

In the multivariable model, the green Mediterranean dieters had greater PAS reduction than did the healthy-diet and Mediterranean dieters (P = .003 and P = .032, respectively).

The researchers caution that DIRECT-PLUS had multiple endpoints and this exploratory post hoc analysis might be sensitive to type I statistical error and should be considered “hypothesis-generating.”

High-quality study, believable results

Reached for comment on the study, Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, director of Mount Sinai Heart in New York, said, “There is not a lot of high-quality research on diet, and I would call this high-quality research in as much as they used randomization which most dietary studies don’t do.

“The greener Mediterranean diet seemed to be the best one on the surrogate marker of MRI-defined aortic stiffness,” Dr. Bhatt, professor of cardiovascular medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, who wasn’t involved in the study, told this news organization.

“It makes sense that a diet that has more green in it, more polyphenols, would be healthier. This has been shown in some other studies, that these plant-based polyphenols might have various cardiovascular protective aspects to them,” Dr. Bhatt said.

Overall, he said the results are “quite believable, with the caveat that it would be nice to see the results reproduced in a more diverse and larger sample.”

“There is emerging evidence that diets that are higher in fresh fruits and vegetables and whole grains and lower in overall caloric intake, in general, seem to be good diets to reduce cardiovascular risk factors and maybe even reduce actual cardiovascular risk,” Dr. Bhatt added.

The study was funded by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation), the Rosetrees Trust, Israel Ministry of Health, Israel Ministry of Science and Technology, and the California Walnuts Commission. Dr. Shai and Dr. Bhatt have no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A green adaptation to the traditional Mediterranean diet improves proximal aortic stiffness (PAS), a distinct marker of vascular aging and increased cardiovascular risk, according to an exploratory post hoc analysis of the DIRECT-PLUS randomized clinical trial.

The green Mediterranean diet is distinct from the traditional Mediterranean diet because of its more abundant dietary polyphenols, from green tea and a Wolffia globosa (Mankai) plant green shake, and lower intake of red or processed meat.

Independent of weight loss, the modified green Mediterranean diet regressed PAS by 15%, the traditional Mediterranean diet by 7.3%, and the healthy dietary guideline–based diet by 4.8%, the study team observed.

“The DIRECT-PLUS trial research team was the first to introduce the concept of the green-Mediterranean/high polyphenols diet,” lead researcher Iris Shai, RD, PhD, with Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Be’er-Sheva, Israel, told this news organization.

This diet promoted “dramatic proximal aortic de-stiffening” as assessed by MRI over 18 months in roughly 300 participants with abdominal obesity/dyslipidemia. “To date, no dietary strategies have been shown to impact vascular aging physiology,” Dr. Shai said.

The analysis was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Not all healthy diets are equal

Of the 294 participants, 281 had valid PAS measurements at baseline. The baseline PAS (6.1 m/s) was similar across intervention groups (P = .20). Increased PAS was associated with aging, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and visceral adiposity (P < .05).

After 18 months’ intervention (retention rate 89.8%), all diet groups showed significant PAS reductions: –0.05 m/s with the standard healthy diet (4.8%), –0.08 m/s with the traditional Mediterranean diet (7.3%) and –0.15 the green Mediterranean diet (15%).

In the multivariable model, the green Mediterranean dieters had greater PAS reduction than did the healthy-diet and Mediterranean dieters (P = .003 and P = .032, respectively).

The researchers caution that DIRECT-PLUS had multiple endpoints and this exploratory post hoc analysis might be sensitive to type I statistical error and should be considered “hypothesis-generating.”

High-quality study, believable results

Reached for comment on the study, Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, director of Mount Sinai Heart in New York, said, “There is not a lot of high-quality research on diet, and I would call this high-quality research in as much as they used randomization which most dietary studies don’t do.

“The greener Mediterranean diet seemed to be the best one on the surrogate marker of MRI-defined aortic stiffness,” Dr. Bhatt, professor of cardiovascular medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, who wasn’t involved in the study, told this news organization.

“It makes sense that a diet that has more green in it, more polyphenols, would be healthier. This has been shown in some other studies, that these plant-based polyphenols might have various cardiovascular protective aspects to them,” Dr. Bhatt said.

Overall, he said the results are “quite believable, with the caveat that it would be nice to see the results reproduced in a more diverse and larger sample.”

“There is emerging evidence that diets that are higher in fresh fruits and vegetables and whole grains and lower in overall caloric intake, in general, seem to be good diets to reduce cardiovascular risk factors and maybe even reduce actual cardiovascular risk,” Dr. Bhatt added.

The study was funded by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation), the Rosetrees Trust, Israel Ministry of Health, Israel Ministry of Science and Technology, and the California Walnuts Commission. Dr. Shai and Dr. Bhatt have no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A green adaptation to the traditional Mediterranean diet improves proximal aortic stiffness (PAS), a distinct marker of vascular aging and increased cardiovascular risk, according to an exploratory post hoc analysis of the DIRECT-PLUS randomized clinical trial.

The green Mediterranean diet is distinct from the traditional Mediterranean diet because of its more abundant dietary polyphenols, from green tea and a Wolffia globosa (Mankai) plant green shake, and lower intake of red or processed meat.

Independent of weight loss, the modified green Mediterranean diet regressed PAS by 15%, the traditional Mediterranean diet by 7.3%, and the healthy dietary guideline–based diet by 4.8%, the study team observed.

“The DIRECT-PLUS trial research team was the first to introduce the concept of the green-Mediterranean/high polyphenols diet,” lead researcher Iris Shai, RD, PhD, with Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Be’er-Sheva, Israel, told this news organization.

This diet promoted “dramatic proximal aortic de-stiffening” as assessed by MRI over 18 months in roughly 300 participants with abdominal obesity/dyslipidemia. “To date, no dietary strategies have been shown to impact vascular aging physiology,” Dr. Shai said.

The analysis was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Not all healthy diets are equal

Of the 294 participants, 281 had valid PAS measurements at baseline. The baseline PAS (6.1 m/s) was similar across intervention groups (P = .20). Increased PAS was associated with aging, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and visceral adiposity (P < .05).

After 18 months’ intervention (retention rate 89.8%), all diet groups showed significant PAS reductions: –0.05 m/s with the standard healthy diet (4.8%), –0.08 m/s with the traditional Mediterranean diet (7.3%) and –0.15 the green Mediterranean diet (15%).

In the multivariable model, the green Mediterranean dieters had greater PAS reduction than did the healthy-diet and Mediterranean dieters (P = .003 and P = .032, respectively).

The researchers caution that DIRECT-PLUS had multiple endpoints and this exploratory post hoc analysis might be sensitive to type I statistical error and should be considered “hypothesis-generating.”

High-quality study, believable results

Reached for comment on the study, Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, director of Mount Sinai Heart in New York, said, “There is not a lot of high-quality research on diet, and I would call this high-quality research in as much as they used randomization which most dietary studies don’t do.

“The greener Mediterranean diet seemed to be the best one on the surrogate marker of MRI-defined aortic stiffness,” Dr. Bhatt, professor of cardiovascular medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, who wasn’t involved in the study, told this news organization.

“It makes sense that a diet that has more green in it, more polyphenols, would be healthier. This has been shown in some other studies, that these plant-based polyphenols might have various cardiovascular protective aspects to them,” Dr. Bhatt said.

Overall, he said the results are “quite believable, with the caveat that it would be nice to see the results reproduced in a more diverse and larger sample.”

“There is emerging evidence that diets that are higher in fresh fruits and vegetables and whole grains and lower in overall caloric intake, in general, seem to be good diets to reduce cardiovascular risk factors and maybe even reduce actual cardiovascular risk,” Dr. Bhatt added.

The study was funded by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation), the Rosetrees Trust, Israel Ministry of Health, Israel Ministry of Science and Technology, and the California Walnuts Commission. Dr. Shai and Dr. Bhatt have no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mediterranean diet improves cognition in MS

due to a potential neuroprotective mechanism, according to findings of a study that was released early, ahead of presentation at the annual meting of the American Academy of Neurology.

“We were most surprised by the magnitude of the results,” said Ilana Katz Sand, MD, associate professor of neurology at the Corinne Goldsmith Dickinson Center for MS at Mount Sinai in New York. “We hypothesized a significant association between Mediterranean diet and cognition in MS, but we did not anticipate the 20% absolute difference, particularly because we rigorously controlled the demographic and health-related factors, like socioeconomic status, body mass index, and exercise habits.”

The Mediterranean diet consists of predominately vegetables, fruits, legumes, fish, and healthy fats while minimizing the consumption of dairy products, meats, and saturated acids. Previous literature has drawn an association between diet and MS symptomology, notably with regard to the Mediterranean diet. These studies indicated a connection between thalamic volume in patients with early MS as well as objectively captured MS-related disability. In this study, researchers have continued their investigation by exploring how the Mediterranean diet affects cognition.

In this cross-sectional observational study, investigators evaluated 563 people with MS ranging in age from 18 to 65 years (n = 563; 71% women; aged 44.2 ± 11.3 years). To accomplish this task, researchers conducted a retrospective chart review capturing data from patients with MS who had undergone neurobehavioral screenings. Qualifying subjects completed the Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS) to determine the extent to which they adhered to the Mediterranean diet. A 14-item questionnaire, MEDAS assess a person’s usual intake of healthful foods such as vegetables and olive oil, as well as minimization of unhealthy foods such as butter and red meat. They also completed an analogue of the CICMAS cognitive battery comprised of a composite of Symbol Digit Modalities Test, Hopkins Verbal Learning Test, Revised, and CANTAB Paired Associate Learning.

Researchers evaluated patient-reported outcomes adjusted based on demographics (i.e., age, sex, race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status) and health-related factors. These elements included body mass index, exercise, sleep disturbance, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and smoking.

The study excluded patients who had another primary neurological condition in addition to MS (n = 24), serious psychiatric illness such as schizophrenia (n = 5) or clinical relapse within 6 weeks (n = 2), or missing data (n = 13).

Based on the diet scores, investigators stratified participants into four groups. Those with the scores ranging from 0 to 4 were classified into the lowest group, while scores of 9 or greater qualified participants for the high group.

Investigators observed a significant association between a higher Mediterranean diet score and condition in the population sampled. They found a mean z-score of –0.67 (0.95). In addition, a higher MEDAS proved an independent indicator of better cognition (B = 0.08 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.05, 0.11], beta = 0.20, P < .001). In fact, a high MEDAS independently correlated to a 20% lower risk for cognitive impairment (odds ratio [OR] = .80 {95% CI, 0.73, 0.89}, P < .001). Ultimately, the study’s findings demonstrated MEDAS served as the strongest health-related indicator of z-score and cognitive impairment. Moreover, dietary modification based on effect suggested stronger associations between diet and cognition with progressive disease as opposed to relapsing disease, as noted by the relationship between the z-score and cognition.

“Further research is needed,” Dr. Katz Sand said. “But because the progressive phenotype reflects more prominent neurodegeneration, the greater observed effect size in those with progressive MS suggests a potential neuroprotective mechanism.”

This study was funded in part by an Irma T. Hirschl/Monique Weill-Caulier Research Award to Dr. Katz Sand. Dr. Katz Sand and coauthors also received funding from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

due to a potential neuroprotective mechanism, according to findings of a study that was released early, ahead of presentation at the annual meting of the American Academy of Neurology.

“We were most surprised by the magnitude of the results,” said Ilana Katz Sand, MD, associate professor of neurology at the Corinne Goldsmith Dickinson Center for MS at Mount Sinai in New York. “We hypothesized a significant association between Mediterranean diet and cognition in MS, but we did not anticipate the 20% absolute difference, particularly because we rigorously controlled the demographic and health-related factors, like socioeconomic status, body mass index, and exercise habits.”

The Mediterranean diet consists of predominately vegetables, fruits, legumes, fish, and healthy fats while minimizing the consumption of dairy products, meats, and saturated acids. Previous literature has drawn an association between diet and MS symptomology, notably with regard to the Mediterranean diet. These studies indicated a connection between thalamic volume in patients with early MS as well as objectively captured MS-related disability. In this study, researchers have continued their investigation by exploring how the Mediterranean diet affects cognition.

In this cross-sectional observational study, investigators evaluated 563 people with MS ranging in age from 18 to 65 years (n = 563; 71% women; aged 44.2 ± 11.3 years). To accomplish this task, researchers conducted a retrospective chart review capturing data from patients with MS who had undergone neurobehavioral screenings. Qualifying subjects completed the Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS) to determine the extent to which they adhered to the Mediterranean diet. A 14-item questionnaire, MEDAS assess a person’s usual intake of healthful foods such as vegetables and olive oil, as well as minimization of unhealthy foods such as butter and red meat. They also completed an analogue of the CICMAS cognitive battery comprised of a composite of Symbol Digit Modalities Test, Hopkins Verbal Learning Test, Revised, and CANTAB Paired Associate Learning.

Researchers evaluated patient-reported outcomes adjusted based on demographics (i.e., age, sex, race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status) and health-related factors. These elements included body mass index, exercise, sleep disturbance, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and smoking.

The study excluded patients who had another primary neurological condition in addition to MS (n = 24), serious psychiatric illness such as schizophrenia (n = 5) or clinical relapse within 6 weeks (n = 2), or missing data (n = 13).

Based on the diet scores, investigators stratified participants into four groups. Those with the scores ranging from 0 to 4 were classified into the lowest group, while scores of 9 or greater qualified participants for the high group.

Investigators observed a significant association between a higher Mediterranean diet score and condition in the population sampled. They found a mean z-score of –0.67 (0.95). In addition, a higher MEDAS proved an independent indicator of better cognition (B = 0.08 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.05, 0.11], beta = 0.20, P < .001). In fact, a high MEDAS independently correlated to a 20% lower risk for cognitive impairment (odds ratio [OR] = .80 {95% CI, 0.73, 0.89}, P < .001). Ultimately, the study’s findings demonstrated MEDAS served as the strongest health-related indicator of z-score and cognitive impairment. Moreover, dietary modification based on effect suggested stronger associations between diet and cognition with progressive disease as opposed to relapsing disease, as noted by the relationship between the z-score and cognition.

“Further research is needed,” Dr. Katz Sand said. “But because the progressive phenotype reflects more prominent neurodegeneration, the greater observed effect size in those with progressive MS suggests a potential neuroprotective mechanism.”

This study was funded in part by an Irma T. Hirschl/Monique Weill-Caulier Research Award to Dr. Katz Sand. Dr. Katz Sand and coauthors also received funding from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

due to a potential neuroprotective mechanism, according to findings of a study that was released early, ahead of presentation at the annual meting of the American Academy of Neurology.

“We were most surprised by the magnitude of the results,” said Ilana Katz Sand, MD, associate professor of neurology at the Corinne Goldsmith Dickinson Center for MS at Mount Sinai in New York. “We hypothesized a significant association between Mediterranean diet and cognition in MS, but we did not anticipate the 20% absolute difference, particularly because we rigorously controlled the demographic and health-related factors, like socioeconomic status, body mass index, and exercise habits.”

The Mediterranean diet consists of predominately vegetables, fruits, legumes, fish, and healthy fats while minimizing the consumption of dairy products, meats, and saturated acids. Previous literature has drawn an association between diet and MS symptomology, notably with regard to the Mediterranean diet. These studies indicated a connection between thalamic volume in patients with early MS as well as objectively captured MS-related disability. In this study, researchers have continued their investigation by exploring how the Mediterranean diet affects cognition.

In this cross-sectional observational study, investigators evaluated 563 people with MS ranging in age from 18 to 65 years (n = 563; 71% women; aged 44.2 ± 11.3 years). To accomplish this task, researchers conducted a retrospective chart review capturing data from patients with MS who had undergone neurobehavioral screenings. Qualifying subjects completed the Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS) to determine the extent to which they adhered to the Mediterranean diet. A 14-item questionnaire, MEDAS assess a person’s usual intake of healthful foods such as vegetables and olive oil, as well as minimization of unhealthy foods such as butter and red meat. They also completed an analogue of the CICMAS cognitive battery comprised of a composite of Symbol Digit Modalities Test, Hopkins Verbal Learning Test, Revised, and CANTAB Paired Associate Learning.

Researchers evaluated patient-reported outcomes adjusted based on demographics (i.e., age, sex, race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status) and health-related factors. These elements included body mass index, exercise, sleep disturbance, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and smoking.

The study excluded patients who had another primary neurological condition in addition to MS (n = 24), serious psychiatric illness such as schizophrenia (n = 5) or clinical relapse within 6 weeks (n = 2), or missing data (n = 13).

Based on the diet scores, investigators stratified participants into four groups. Those with the scores ranging from 0 to 4 were classified into the lowest group, while scores of 9 or greater qualified participants for the high group.

Investigators observed a significant association between a higher Mediterranean diet score and condition in the population sampled. They found a mean z-score of –0.67 (0.95). In addition, a higher MEDAS proved an independent indicator of better cognition (B = 0.08 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.05, 0.11], beta = 0.20, P < .001). In fact, a high MEDAS independently correlated to a 20% lower risk for cognitive impairment (odds ratio [OR] = .80 {95% CI, 0.73, 0.89}, P < .001). Ultimately, the study’s findings demonstrated MEDAS served as the strongest health-related indicator of z-score and cognitive impairment. Moreover, dietary modification based on effect suggested stronger associations between diet and cognition with progressive disease as opposed to relapsing disease, as noted by the relationship between the z-score and cognition.

“Further research is needed,” Dr. Katz Sand said. “But because the progressive phenotype reflects more prominent neurodegeneration, the greater observed effect size in those with progressive MS suggests a potential neuroprotective mechanism.”

This study was funded in part by an Irma T. Hirschl/Monique Weill-Caulier Research Award to Dr. Katz Sand. Dr. Katz Sand and coauthors also received funding from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

FROM AAN 2023

Rabies: How to respond to parents’ questions

When most families hear the word rabies, they envision a dog foaming at the mouth and think about receiving multiple painful, often intra-abdominal injections. However, the epidemiology of rabies has changed in the United States. Postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) may not always be indicated and for certain persons preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is available and recommended.

Rabies is a Lyssavirus that is transmitted through saliva most often from the bite or scratch of an infected animal. Sometimes it’s via direct contact with mucous membranes. Although rare, cases have been described in which an undiagnosed donor passed the virus via transplant to recipients and four cases of aerosolized transmission were documented in two spelunkers and two laboratory technicians working with the virus. Worldwide it’s estimated that rabies causes 59,000 deaths annually.

Most cases (98%) are secondary to canine rabies. Prior to 1960, dogs were the major reservoir in the United States; however, after introduction of leash laws and animal vaccination in 1947, there was a drastic decline in cases caused by the canine rabies virus variant (CRVV). By 2004, CRVV was eliminated in the United States.

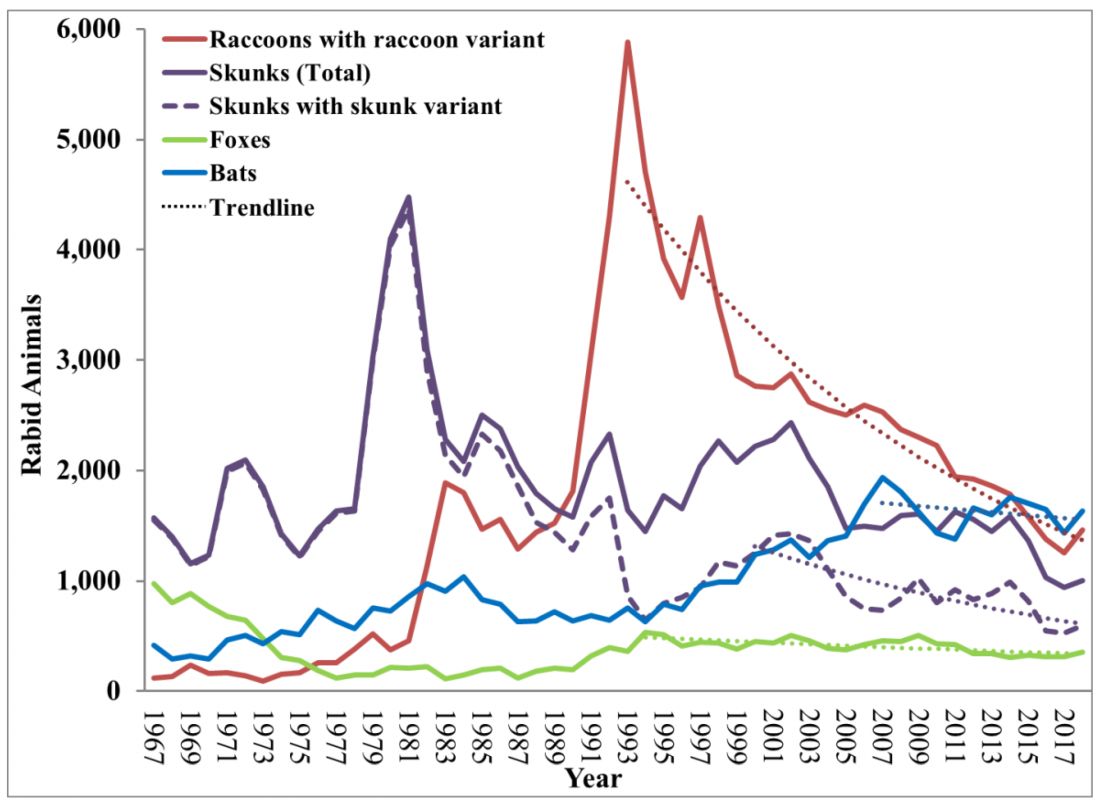

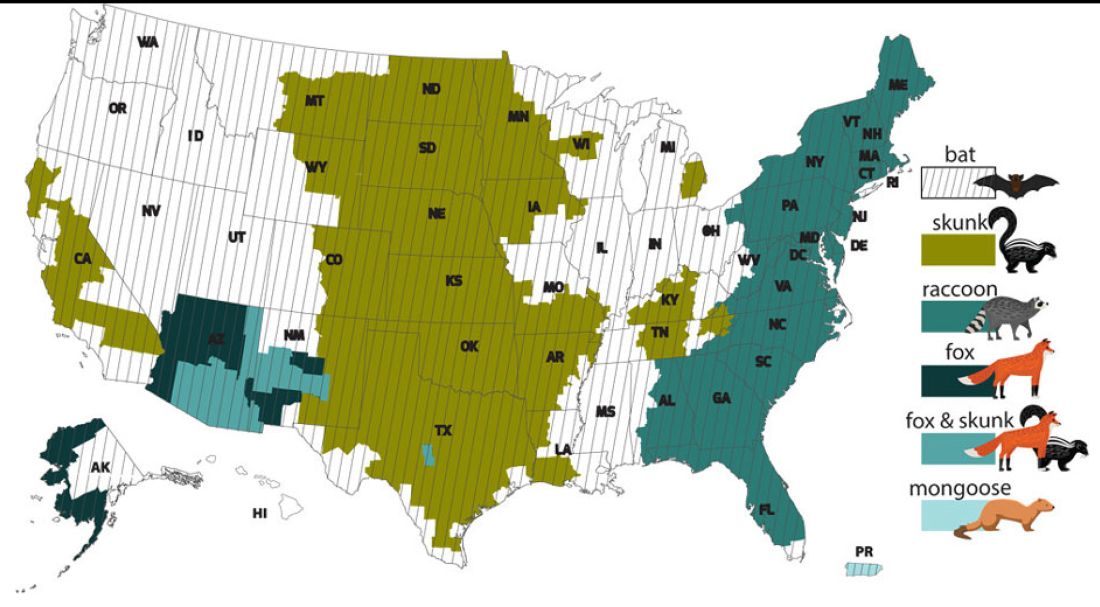

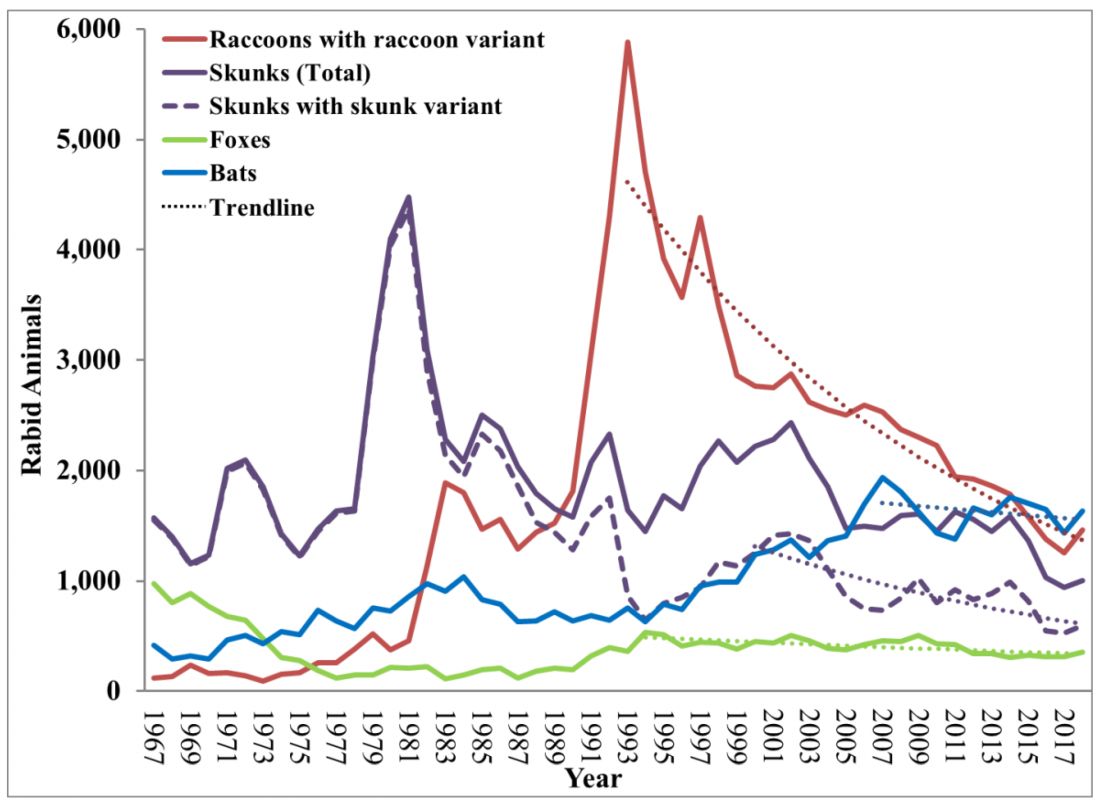

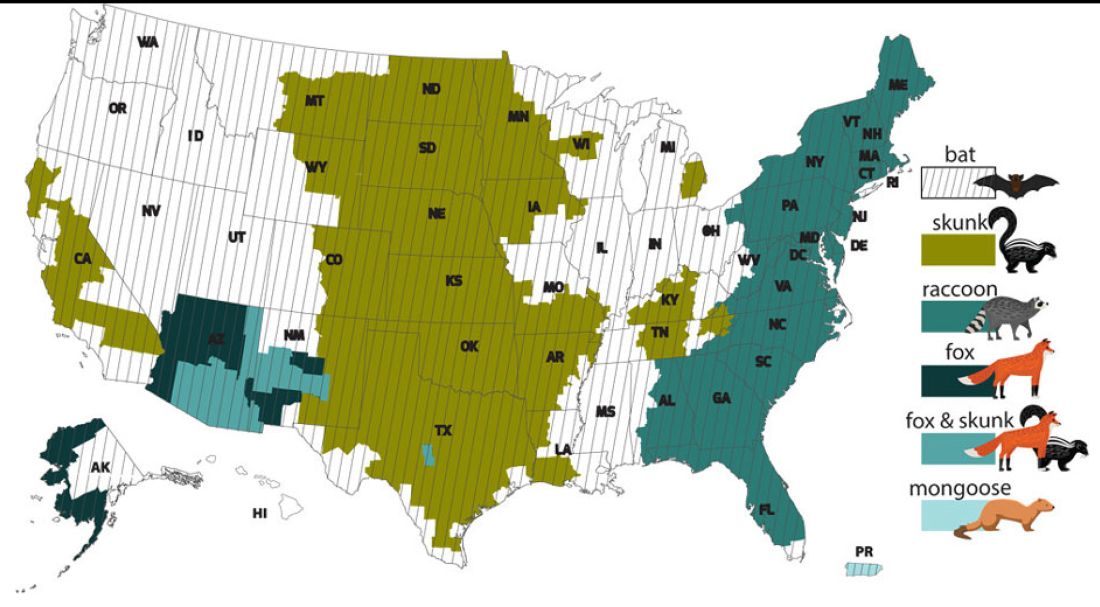

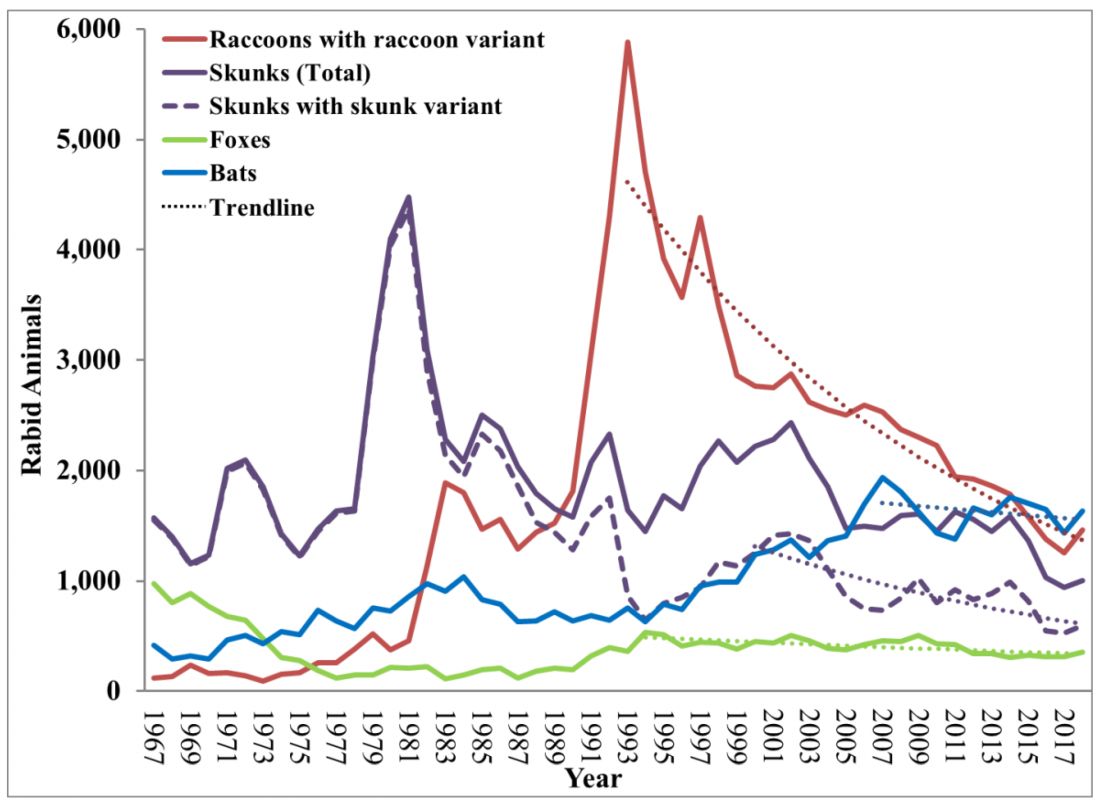

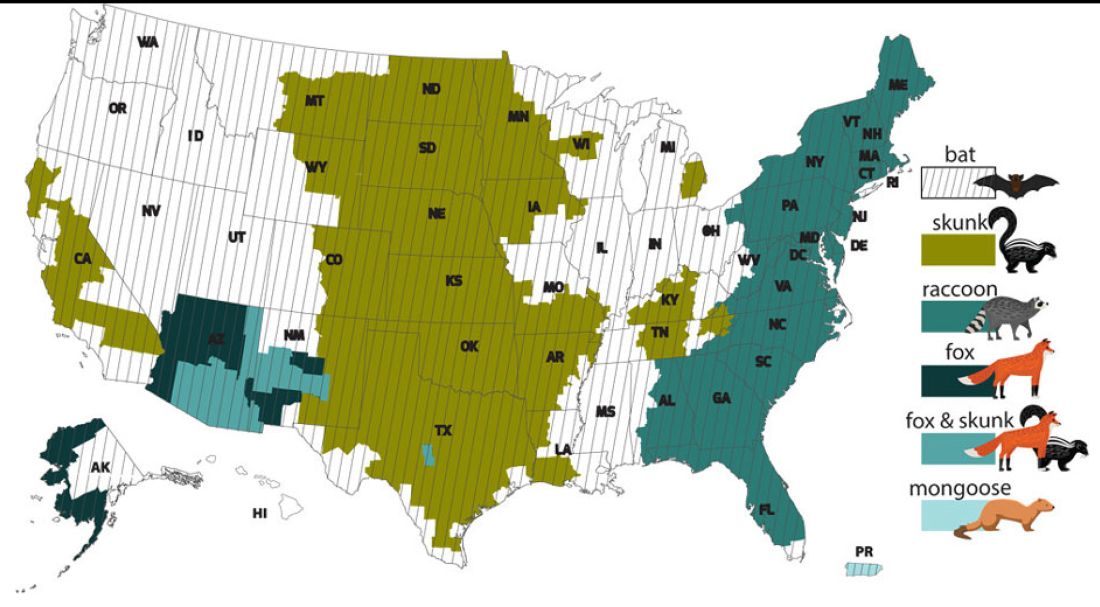

However, the proportion of strains associated with wildlife including raccoons, skunks, foxes, bats, coyotes, and mongoose now account for most of the cases in humans. Wildlife rabies is found in all states except Hawaii. Between 1960 and 2018, 89 cases were acquired in the United States and 62 (70%) were from bat exposure. Dog bites acquired during international travel were the cause of 36 cases.

Once signs and symptoms of disease develop there is no treatment. Regardless of the species variant, rabies virus infection is fatal in over 99% of cases. However, disease can be prevented with prompt initiation of PEP, which includes administration of rabies immune globulin (RIG) and rabies vaccine. Let’s look at a few different scenarios.

1. A delivery person is bitten by your neighbor’s dog while making a delivery. He was told to get rabies vaccine. What should we advise?

Canine rabies has been eliminated in the United States. However, unvaccinated canines can acquire rabies from wildlife. In this situation, you can determine the immunization status of the dog. Contact your local/state health department to assist with enforcement and management. Bites by cats and ferrets should be managed similarly.

Healthy dog:

1. Observe for 10 days.

2. PEP is not indicated unless the animal develops signs/symptoms of rabies. Then euthanize and begin PEP.

Dog appears rabid or suspected to be rabid:

1. Begin PEP.

2. Animal should be euthanized. If immunofluorescent test is negative discontinue PEP.

Dog unavailable:

Contact local/state health department. They are more familiar with rabies surveillance data.

2. Patient relocating to Malaysia for 3-4 years. Rabies PrEP was recommended but the family wants your opinion before receiving the vaccine. What would you advise?

Canine rabies is felt to be the primary cause of rabies outside of the United States. Canines are not routinely vaccinated in many foreign destinations, and the availability of RIG and rabies vaccine is not guaranteed in developing countries. As noted above, dog bites during international travel accounted for 28% of U.S. cases between 1960 and 2018.

In May 2022 recommendations for a modified two-dose PrEP schedule was published that identifies five risk groups and includes specific timing for checking rabies titers. The third rabies dose can now be administered up until year 3 (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022 May 6;71[18]:619-27). For individuals relocating to countries where CRVV is present, I prefer the traditional three-dose PrEP schedule administered between 21 and 28 days. However, we now have options. If exposure occurs any time after completion of a three-dose PrEP series or within 3 years after completion of a two-dose PrEP series, RIG would not be required. All patients would receive two doses of rabies vaccine (days 0, 3). If exposure occurs after 3 years in a person who received two doses of PrEP who did not have documentation of a protective rabies titer (> 5 IU/mL), treatment will include RIG plus four doses of vaccine (days 0, 3, 7, 14).

For this relocating patient, supporting PrEP would be strongly recommended.

3. A mother tells you she sees bats flying around her home at night and a few have even gotten into the home. This morning she saw one in her child’s room. He was still sleeping. Is there anything she needs to do?

Bats have become the predominant source of rabies in the United States. In addition to the cases noted above, three fatal cases occurred between Sept. 28 and Nov. 10, 2021, after bat exposures in August 2021 (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022 Jan 7;71:31-2). All had recognized contact with a bat 3-7 weeks prior to onset of symptoms and died 2-3 weeks after symptom onset. One declined PEP and the other two did not realize the risk for rabies from their exposure or did not notice a scratch or bite. Bites from bats may be small and unnoticed. Exposure to a bat in a closed room while sleeping is considered an exposure. Hawaii is the only state not reporting rabid bats.

PEP is recommended for her child. She should identify potential areas bats may enter the home and seal them in addition to removal of any bat roosts.

4. A parent realizes a house guest has been feeding raccoons in the backyard. What’s your response?

While bat rabies is the predominant variant associated with disease in the United States, as illustrated in Figure 1, other species of wildlife including raccoons are a major source of rabies. The geographic spread of the raccoon variant of rabies has been limited by oral vaccination via bait. In the situation noted here, the raccoons have returned because food was being offered thus increasing the families chance of a potential rabies exposure. Wildlife including skunks, raccoons, coyotes, foxes, and mongooses are always considered rabid until proven negative by laboratory testing.

You recommend to stop feeding wildlife and never to approach them. Have them contact the local rabies control unit and/or state wildlife services to assist with removal of the raccoons. Depending on the locale, pest control may be required at the owners expense. Inform the family to seek PEP if anyone is bitten or scratched by the raccoons.

As per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 55,000 residents receive PEP annually with health-associated expenditures including diagnostics, prevention, and control estimated between $245 and $510 million annually. Rabies is one of the most fatal diseases that can be prevented by avoiding contact with wild animals, maintenance of high immunization rates in pets, and keeping people informed of potential sources including bats. One can’t determine if an animal has rabies by looking at it. Rabies remains an urgent disease that we have to remember to address with our patients and their families. For additional information go to www.CDC.gov/rabies.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She has no relevant financial disclosures.

When most families hear the word rabies, they envision a dog foaming at the mouth and think about receiving multiple painful, often intra-abdominal injections. However, the epidemiology of rabies has changed in the United States. Postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) may not always be indicated and for certain persons preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is available and recommended.

Rabies is a Lyssavirus that is transmitted through saliva most often from the bite or scratch of an infected animal. Sometimes it’s via direct contact with mucous membranes. Although rare, cases have been described in which an undiagnosed donor passed the virus via transplant to recipients and four cases of aerosolized transmission were documented in two spelunkers and two laboratory technicians working with the virus. Worldwide it’s estimated that rabies causes 59,000 deaths annually.

Most cases (98%) are secondary to canine rabies. Prior to 1960, dogs were the major reservoir in the United States; however, after introduction of leash laws and animal vaccination in 1947, there was a drastic decline in cases caused by the canine rabies virus variant (CRVV). By 2004, CRVV was eliminated in the United States.

However, the proportion of strains associated with wildlife including raccoons, skunks, foxes, bats, coyotes, and mongoose now account for most of the cases in humans. Wildlife rabies is found in all states except Hawaii. Between 1960 and 2018, 89 cases were acquired in the United States and 62 (70%) were from bat exposure. Dog bites acquired during international travel were the cause of 36 cases.

Once signs and symptoms of disease develop there is no treatment. Regardless of the species variant, rabies virus infection is fatal in over 99% of cases. However, disease can be prevented with prompt initiation of PEP, which includes administration of rabies immune globulin (RIG) and rabies vaccine. Let’s look at a few different scenarios.

1. A delivery person is bitten by your neighbor’s dog while making a delivery. He was told to get rabies vaccine. What should we advise?

Canine rabies has been eliminated in the United States. However, unvaccinated canines can acquire rabies from wildlife. In this situation, you can determine the immunization status of the dog. Contact your local/state health department to assist with enforcement and management. Bites by cats and ferrets should be managed similarly.

Healthy dog:

1. Observe for 10 days.

2. PEP is not indicated unless the animal develops signs/symptoms of rabies. Then euthanize and begin PEP.

Dog appears rabid or suspected to be rabid:

1. Begin PEP.

2. Animal should be euthanized. If immunofluorescent test is negative discontinue PEP.

Dog unavailable:

Contact local/state health department. They are more familiar with rabies surveillance data.

2. Patient relocating to Malaysia for 3-4 years. Rabies PrEP was recommended but the family wants your opinion before receiving the vaccine. What would you advise?

Canine rabies is felt to be the primary cause of rabies outside of the United States. Canines are not routinely vaccinated in many foreign destinations, and the availability of RIG and rabies vaccine is not guaranteed in developing countries. As noted above, dog bites during international travel accounted for 28% of U.S. cases between 1960 and 2018.

In May 2022 recommendations for a modified two-dose PrEP schedule was published that identifies five risk groups and includes specific timing for checking rabies titers. The third rabies dose can now be administered up until year 3 (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022 May 6;71[18]:619-27). For individuals relocating to countries where CRVV is present, I prefer the traditional three-dose PrEP schedule administered between 21 and 28 days. However, we now have options. If exposure occurs any time after completion of a three-dose PrEP series or within 3 years after completion of a two-dose PrEP series, RIG would not be required. All patients would receive two doses of rabies vaccine (days 0, 3). If exposure occurs after 3 years in a person who received two doses of PrEP who did not have documentation of a protective rabies titer (> 5 IU/mL), treatment will include RIG plus four doses of vaccine (days 0, 3, 7, 14).

For this relocating patient, supporting PrEP would be strongly recommended.

3. A mother tells you she sees bats flying around her home at night and a few have even gotten into the home. This morning she saw one in her child’s room. He was still sleeping. Is there anything she needs to do?

Bats have become the predominant source of rabies in the United States. In addition to the cases noted above, three fatal cases occurred between Sept. 28 and Nov. 10, 2021, after bat exposures in August 2021 (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022 Jan 7;71:31-2). All had recognized contact with a bat 3-7 weeks prior to onset of symptoms and died 2-3 weeks after symptom onset. One declined PEP and the other two did not realize the risk for rabies from their exposure or did not notice a scratch or bite. Bites from bats may be small and unnoticed. Exposure to a bat in a closed room while sleeping is considered an exposure. Hawaii is the only state not reporting rabid bats.

PEP is recommended for her child. She should identify potential areas bats may enter the home and seal them in addition to removal of any bat roosts.

4. A parent realizes a house guest has been feeding raccoons in the backyard. What’s your response?

While bat rabies is the predominant variant associated with disease in the United States, as illustrated in Figure 1, other species of wildlife including raccoons are a major source of rabies. The geographic spread of the raccoon variant of rabies has been limited by oral vaccination via bait. In the situation noted here, the raccoons have returned because food was being offered thus increasing the families chance of a potential rabies exposure. Wildlife including skunks, raccoons, coyotes, foxes, and mongooses are always considered rabid until proven negative by laboratory testing.

You recommend to stop feeding wildlife and never to approach them. Have them contact the local rabies control unit and/or state wildlife services to assist with removal of the raccoons. Depending on the locale, pest control may be required at the owners expense. Inform the family to seek PEP if anyone is bitten or scratched by the raccoons.

As per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 55,000 residents receive PEP annually with health-associated expenditures including diagnostics, prevention, and control estimated between $245 and $510 million annually. Rabies is one of the most fatal diseases that can be prevented by avoiding contact with wild animals, maintenance of high immunization rates in pets, and keeping people informed of potential sources including bats. One can’t determine if an animal has rabies by looking at it. Rabies remains an urgent disease that we have to remember to address with our patients and their families. For additional information go to www.CDC.gov/rabies.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She has no relevant financial disclosures.

When most families hear the word rabies, they envision a dog foaming at the mouth and think about receiving multiple painful, often intra-abdominal injections. However, the epidemiology of rabies has changed in the United States. Postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) may not always be indicated and for certain persons preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is available and recommended.

Rabies is a Lyssavirus that is transmitted through saliva most often from the bite or scratch of an infected animal. Sometimes it’s via direct contact with mucous membranes. Although rare, cases have been described in which an undiagnosed donor passed the virus via transplant to recipients and four cases of aerosolized transmission were documented in two spelunkers and two laboratory technicians working with the virus. Worldwide it’s estimated that rabies causes 59,000 deaths annually.

Most cases (98%) are secondary to canine rabies. Prior to 1960, dogs were the major reservoir in the United States; however, after introduction of leash laws and animal vaccination in 1947, there was a drastic decline in cases caused by the canine rabies virus variant (CRVV). By 2004, CRVV was eliminated in the United States.

However, the proportion of strains associated with wildlife including raccoons, skunks, foxes, bats, coyotes, and mongoose now account for most of the cases in humans. Wildlife rabies is found in all states except Hawaii. Between 1960 and 2018, 89 cases were acquired in the United States and 62 (70%) were from bat exposure. Dog bites acquired during international travel were the cause of 36 cases.

Once signs and symptoms of disease develop there is no treatment. Regardless of the species variant, rabies virus infection is fatal in over 99% of cases. However, disease can be prevented with prompt initiation of PEP, which includes administration of rabies immune globulin (RIG) and rabies vaccine. Let’s look at a few different scenarios.

1. A delivery person is bitten by your neighbor’s dog while making a delivery. He was told to get rabies vaccine. What should we advise?

Canine rabies has been eliminated in the United States. However, unvaccinated canines can acquire rabies from wildlife. In this situation, you can determine the immunization status of the dog. Contact your local/state health department to assist with enforcement and management. Bites by cats and ferrets should be managed similarly.

Healthy dog:

1. Observe for 10 days.

2. PEP is not indicated unless the animal develops signs/symptoms of rabies. Then euthanize and begin PEP.

Dog appears rabid or suspected to be rabid:

1. Begin PEP.

2. Animal should be euthanized. If immunofluorescent test is negative discontinue PEP.

Dog unavailable:

Contact local/state health department. They are more familiar with rabies surveillance data.

2. Patient relocating to Malaysia for 3-4 years. Rabies PrEP was recommended but the family wants your opinion before receiving the vaccine. What would you advise?

Canine rabies is felt to be the primary cause of rabies outside of the United States. Canines are not routinely vaccinated in many foreign destinations, and the availability of RIG and rabies vaccine is not guaranteed in developing countries. As noted above, dog bites during international travel accounted for 28% of U.S. cases between 1960 and 2018.

In May 2022 recommendations for a modified two-dose PrEP schedule was published that identifies five risk groups and includes specific timing for checking rabies titers. The third rabies dose can now be administered up until year 3 (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022 May 6;71[18]:619-27). For individuals relocating to countries where CRVV is present, I prefer the traditional three-dose PrEP schedule administered between 21 and 28 days. However, we now have options. If exposure occurs any time after completion of a three-dose PrEP series or within 3 years after completion of a two-dose PrEP series, RIG would not be required. All patients would receive two doses of rabies vaccine (days 0, 3). If exposure occurs after 3 years in a person who received two doses of PrEP who did not have documentation of a protective rabies titer (> 5 IU/mL), treatment will include RIG plus four doses of vaccine (days 0, 3, 7, 14).

For this relocating patient, supporting PrEP would be strongly recommended.

3. A mother tells you she sees bats flying around her home at night and a few have even gotten into the home. This morning she saw one in her child’s room. He was still sleeping. Is there anything she needs to do?

Bats have become the predominant source of rabies in the United States. In addition to the cases noted above, three fatal cases occurred between Sept. 28 and Nov. 10, 2021, after bat exposures in August 2021 (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022 Jan 7;71:31-2). All had recognized contact with a bat 3-7 weeks prior to onset of symptoms and died 2-3 weeks after symptom onset. One declined PEP and the other two did not realize the risk for rabies from their exposure or did not notice a scratch or bite. Bites from bats may be small and unnoticed. Exposure to a bat in a closed room while sleeping is considered an exposure. Hawaii is the only state not reporting rabid bats.

PEP is recommended for her child. She should identify potential areas bats may enter the home and seal them in addition to removal of any bat roosts.

4. A parent realizes a house guest has been feeding raccoons in the backyard. What’s your response?

While bat rabies is the predominant variant associated with disease in the United States, as illustrated in Figure 1, other species of wildlife including raccoons are a major source of rabies. The geographic spread of the raccoon variant of rabies has been limited by oral vaccination via bait. In the situation noted here, the raccoons have returned because food was being offered thus increasing the families chance of a potential rabies exposure. Wildlife including skunks, raccoons, coyotes, foxes, and mongooses are always considered rabid until proven negative by laboratory testing.

You recommend to stop feeding wildlife and never to approach them. Have them contact the local rabies control unit and/or state wildlife services to assist with removal of the raccoons. Depending on the locale, pest control may be required at the owners expense. Inform the family to seek PEP if anyone is bitten or scratched by the raccoons.

As per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 55,000 residents receive PEP annually with health-associated expenditures including diagnostics, prevention, and control estimated between $245 and $510 million annually. Rabies is one of the most fatal diseases that can be prevented by avoiding contact with wild animals, maintenance of high immunization rates in pets, and keeping people informed of potential sources including bats. One can’t determine if an animal has rabies by looking at it. Rabies remains an urgent disease that we have to remember to address with our patients and their families. For additional information go to www.CDC.gov/rabies.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She has no relevant financial disclosures.

PsA Pathophysiology and Etiology

Obstructive sleep apnea linked to early cognitive decline

In a pilot study out of King’s College London, participants with severe OSA experienced worse executive functioning as well as social and emotional recognition versus healthy controls.

Major risk factors for OSA include obesity, high blood pressure, smoking, high cholesterol, and being middle-aged or older. Because some researchers have hypothesized that cognitive deficits could be driven by such comorbidities, the study investigators recruited middle-aged men with no medical comorbidities.

“Traditionally, we were more concerned with sleep apnea’s metabolic and cardiovascular comorbidities, and indeed, when cognitive deficits were demonstrated, most were attributed to them, and yet, our patients and their partners/families commonly tell us differently,” lead investigator Ivana Rosenzweig, MD, PhD, of King’s College London, who is also a consultant in sleep medicine and neuropsychiatry at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital, London, said in an interview.

“Our findings provide a very important first step towards challenging the long-standing dogma that sleep apnea has little to do with the brain – apart from causing sleepiness – and that it is a predominantly nonneuro/psychiatric illness,” added Dr. Rosenzweig.

The findings were published online in Frontiers in Sleep.

Brain changes

The researchers wanted to understand how OSA may be linked to cognitive decline in the absence of cardiovascular and metabolic conditions.

To accomplish this, the investigators studied 27 men between the ages of 35 and 70 with a new diagnosis of mild to severe OSA without any comorbidities (16 with mild OSA and 11 with severe OSA). They also studied a control group of seven men matched for age, body mass index, and education level.

The team tested participants’ cognitive performance using the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery and found that the most significant deficits for the OSA group, compared with controls, were in areas of visual matching ability (P < .0001), short-term visual recognition memory, nonverbal patterns, executive functioning and attentional set-shifting (P < .001), psychomotor functioning, and social cognition and emotional recognition (P < .05).

On the latter two tests, impaired participants were less likely to accurately identify the emotion on computer-generated faces. Those with mild OSA performed better than those with severe OSA on these tasks, but rarely worse than controls.

Dr. Rosenzweig noted that the findings were one-of-a-kind because of the recruitment of patients with OSA who were otherwise healthy and nonobese, “something one rarely sees in the sleep clinic, where we commonly encounter patients with already developed comorbidities.

“In order to truly revolutionize the treatment for our patients, it is important to understand how much the accompanying comorbidities, such as systemic hypertension, obesity, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and other various serious cardiovascular and metabolic diseases and how much the illness itself may shape the demonstrated cognitive deficits,” she said.

She also said that “it is widely agreed that medical problems in middle age may predispose to increased prevalence of dementia in later years.

Moreover, the very link between sleep apnea and Alzheimer’s, vascular and mixed dementia is increasingly demonstrated,” said Dr. Rosenzweig.

Although women typically have a lower prevalence of OSA than men, Dr. Rosenzweig said women were not included in the study “because we are too complex. As a lifelong feminist it pains me to say this, but to get any authoritative answer on our physiology, we need decent funding in place so that we can take into account all the intricacies of the changes of our sleep, physiology, and metabolism.

“While there is always lots of noise about how important it is to answer these questions, there are only very limited funds available for the sleep research,” she added.

Dr. Rosenzweig’s future research will focus on the potential link between OSA and neuroinflammation.

In a comment, Liza Ashbrook, MD, associate professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, said the findings “add to the growing list of negative health consequences associated with sleep apnea.”

She said that, if the cognitive changes found in the study are, in fact, caused by OSA, it is unclear whether they are the beginning of long-term cognitive changes or a symptom of fragmented sleep that may be reversible.

Dr. Ashbrook said she would be interested in seeing research on understanding the effect of OSA treatment on the affected cognitive domains.

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust. No relevant financial relationships were reported.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In a pilot study out of King’s College London, participants with severe OSA experienced worse executive functioning as well as social and emotional recognition versus healthy controls.

Major risk factors for OSA include obesity, high blood pressure, smoking, high cholesterol, and being middle-aged or older. Because some researchers have hypothesized that cognitive deficits could be driven by such comorbidities, the study investigators recruited middle-aged men with no medical comorbidities.

“Traditionally, we were more concerned with sleep apnea’s metabolic and cardiovascular comorbidities, and indeed, when cognitive deficits were demonstrated, most were attributed to them, and yet, our patients and their partners/families commonly tell us differently,” lead investigator Ivana Rosenzweig, MD, PhD, of King’s College London, who is also a consultant in sleep medicine and neuropsychiatry at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital, London, said in an interview.

“Our findings provide a very important first step towards challenging the long-standing dogma that sleep apnea has little to do with the brain – apart from causing sleepiness – and that it is a predominantly nonneuro/psychiatric illness,” added Dr. Rosenzweig.

The findings were published online in Frontiers in Sleep.

Brain changes

The researchers wanted to understand how OSA may be linked to cognitive decline in the absence of cardiovascular and metabolic conditions.

To accomplish this, the investigators studied 27 men between the ages of 35 and 70 with a new diagnosis of mild to severe OSA without any comorbidities (16 with mild OSA and 11 with severe OSA). They also studied a control group of seven men matched for age, body mass index, and education level.

The team tested participants’ cognitive performance using the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery and found that the most significant deficits for the OSA group, compared with controls, were in areas of visual matching ability (P < .0001), short-term visual recognition memory, nonverbal patterns, executive functioning and attentional set-shifting (P < .001), psychomotor functioning, and social cognition and emotional recognition (P < .05).

On the latter two tests, impaired participants were less likely to accurately identify the emotion on computer-generated faces. Those with mild OSA performed better than those with severe OSA on these tasks, but rarely worse than controls.

Dr. Rosenzweig noted that the findings were one-of-a-kind because of the recruitment of patients with OSA who were otherwise healthy and nonobese, “something one rarely sees in the sleep clinic, where we commonly encounter patients with already developed comorbidities.

“In order to truly revolutionize the treatment for our patients, it is important to understand how much the accompanying comorbidities, such as systemic hypertension, obesity, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and other various serious cardiovascular and metabolic diseases and how much the illness itself may shape the demonstrated cognitive deficits,” she said.

She also said that “it is widely agreed that medical problems in middle age may predispose to increased prevalence of dementia in later years.

Moreover, the very link between sleep apnea and Alzheimer’s, vascular and mixed dementia is increasingly demonstrated,” said Dr. Rosenzweig.

Although women typically have a lower prevalence of OSA than men, Dr. Rosenzweig said women were not included in the study “because we are too complex. As a lifelong feminist it pains me to say this, but to get any authoritative answer on our physiology, we need decent funding in place so that we can take into account all the intricacies of the changes of our sleep, physiology, and metabolism.

“While there is always lots of noise about how important it is to answer these questions, there are only very limited funds available for the sleep research,” she added.

Dr. Rosenzweig’s future research will focus on the potential link between OSA and neuroinflammation.

In a comment, Liza Ashbrook, MD, associate professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, said the findings “add to the growing list of negative health consequences associated with sleep apnea.”

She said that, if the cognitive changes found in the study are, in fact, caused by OSA, it is unclear whether they are the beginning of long-term cognitive changes or a symptom of fragmented sleep that may be reversible.

Dr. Ashbrook said she would be interested in seeing research on understanding the effect of OSA treatment on the affected cognitive domains.

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust. No relevant financial relationships were reported.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In a pilot study out of King’s College London, participants with severe OSA experienced worse executive functioning as well as social and emotional recognition versus healthy controls.

Major risk factors for OSA include obesity, high blood pressure, smoking, high cholesterol, and being middle-aged or older. Because some researchers have hypothesized that cognitive deficits could be driven by such comorbidities, the study investigators recruited middle-aged men with no medical comorbidities.

“Traditionally, we were more concerned with sleep apnea’s metabolic and cardiovascular comorbidities, and indeed, when cognitive deficits were demonstrated, most were attributed to them, and yet, our patients and their partners/families commonly tell us differently,” lead investigator Ivana Rosenzweig, MD, PhD, of King’s College London, who is also a consultant in sleep medicine and neuropsychiatry at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital, London, said in an interview.

“Our findings provide a very important first step towards challenging the long-standing dogma that sleep apnea has little to do with the brain – apart from causing sleepiness – and that it is a predominantly nonneuro/psychiatric illness,” added Dr. Rosenzweig.

The findings were published online in Frontiers in Sleep.

Brain changes

The researchers wanted to understand how OSA may be linked to cognitive decline in the absence of cardiovascular and metabolic conditions.

To accomplish this, the investigators studied 27 men between the ages of 35 and 70 with a new diagnosis of mild to severe OSA without any comorbidities (16 with mild OSA and 11 with severe OSA). They also studied a control group of seven men matched for age, body mass index, and education level.

The team tested participants’ cognitive performance using the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery and found that the most significant deficits for the OSA group, compared with controls, were in areas of visual matching ability (P < .0001), short-term visual recognition memory, nonverbal patterns, executive functioning and attentional set-shifting (P < .001), psychomotor functioning, and social cognition and emotional recognition (P < .05).

On the latter two tests, impaired participants were less likely to accurately identify the emotion on computer-generated faces. Those with mild OSA performed better than those with severe OSA on these tasks, but rarely worse than controls.

Dr. Rosenzweig noted that the findings were one-of-a-kind because of the recruitment of patients with OSA who were otherwise healthy and nonobese, “something one rarely sees in the sleep clinic, where we commonly encounter patients with already developed comorbidities.

“In order to truly revolutionize the treatment for our patients, it is important to understand how much the accompanying comorbidities, such as systemic hypertension, obesity, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and other various serious cardiovascular and metabolic diseases and how much the illness itself may shape the demonstrated cognitive deficits,” she said.

She also said that “it is widely agreed that medical problems in middle age may predispose to increased prevalence of dementia in later years.

Moreover, the very link between sleep apnea and Alzheimer’s, vascular and mixed dementia is increasingly demonstrated,” said Dr. Rosenzweig.

Although women typically have a lower prevalence of OSA than men, Dr. Rosenzweig said women were not included in the study “because we are too complex. As a lifelong feminist it pains me to say this, but to get any authoritative answer on our physiology, we need decent funding in place so that we can take into account all the intricacies of the changes of our sleep, physiology, and metabolism.

“While there is always lots of noise about how important it is to answer these questions, there are only very limited funds available for the sleep research,” she added.

Dr. Rosenzweig’s future research will focus on the potential link between OSA and neuroinflammation.

In a comment, Liza Ashbrook, MD, associate professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, said the findings “add to the growing list of negative health consequences associated with sleep apnea.”

She said that, if the cognitive changes found in the study are, in fact, caused by OSA, it is unclear whether they are the beginning of long-term cognitive changes or a symptom of fragmented sleep that may be reversible.

Dr. Ashbrook said she would be interested in seeing research on understanding the effect of OSA treatment on the affected cognitive domains.

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust. No relevant financial relationships were reported.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM FRONTIERS IN SLEEP

Obesity Treatment

MCL Treatment

Optimal time period for weight loss drugs: Debate continues

After bariatric surgery in 2014, Kristal Hartman still struggled to manage her weight long term. It took her over a year to lose 100 pounds, a loss she initially maintained, but then gradually her body mass index (BMI) started creeping up again.

“The body kind of has a set point, and you have to constantly trick it because it is going to start to gain weight again,” Ms. Hartman, who is on the national board of directors for the Obesity Action Coalition, said in an interview.

So, 2.5 years after her surgery, Ms. Hartman began weekly subcutaneous injections of the glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) agonist semaglutide, a medication that is now almost infamous because of its popularity among celebrities and social media influencers.

Branded as Ozempic for type 2 diabetes and Wegovy for obesity, both contain semaglutide but in slightly different doses. The popularity of the medication has led to shortages for those living with type 2 diabetes and/or obesity. And other medications are waiting in the wings that work on GLP-1 and other hormones that regulate appetite, such as the twincretin tirzepatide (Mounjaro), another weekly injection, approved by the Food and Drug Administration in May 2022 for type 2 diabetes and awaiting approval for obesity.

Ms. Hartman said taking semaglutide helped her not only lose weight but also “curb [her] obsessive thoughts over food.” To maintain a BMI within the healthy range, as well as taking the GLP-1 agonist, Ms. Hartman relies on other strategies, including exercise, and mental health support.

“Physicians really need to be open to these FDA-approved medications as one of many tools in the toolbox for patients with obesity. It’s just like any other chronic disease state, when they are thinking of using these, they need to think about long-term use ... in patients who have obesity, not just [among those people] who just want to lose 5-10 pounds. That’s not what these drugs are designed for. They are for people who are actually living with the chronic disease of obesity every day of their lives,” she emphasized.

On average, patients lose 25%-40% of their total body weight following bariatric surgery, said Teresa LeMasters, MD, president of the American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. However, there typically is a “small” weight regain after surgery.

“For most patients, it is a small 5-10 pounds, but for some others, it can be significant,” said Dr. LeMasters, a bariatric surgeon at UnityPoint Clinic, Des Moines, Iowa.

“We do still see some patients– anywhere from 10% to 30% – who will have some [significant] weight regain, and so then we will look at that,” she noted. In those cases, the disease of obesity “is definitely still present.”

Medications can counter weight regain after surgery

For patients who don’t reach their weight loss goals after bariatric surgery, Dr. LeMasters said it’s appropriate to consider adding an anti-obesity medication. The newer GLP-1 agonists can lead to a loss of around 15% of body weight in some patients.

or even just to optimize their initial response to surgery if they are starting at a very, very severe point of disease,” she explained.

She noted, however, that some patients shouldn’t be prescribed GLP-1 agonists, including those with a history of thyroid cancer or pancreatitis.