User login

LISTEN NOW: Ruth Ann Crystal, MD, Pursues Documentary Film "Kitchen Table Deliveries"

Excerpts of The Hospitalist's interview with Dr. Ruth Ann Crystal, who is attempting to create a website with videos of historical medical practice.

Excerpts of The Hospitalist's interview with Dr. Ruth Ann Crystal, who is attempting to create a website with videos of historical medical practice.

Excerpts of The Hospitalist's interview with Dr. Ruth Ann Crystal, who is attempting to create a website with videos of historical medical practice.

Hospitalist Hopes to Build Website Featuring Stories about Delivering Babies in the 1950s

When Ruth Ann Crystal, MD, performed her residency at Stanford University Medical Center more than 15 years ago, she often worked side by side in the operating room with one of her favorite professors, Bert Johnson, MD, a skilled surgeon and obstetrician. While performing vaginal hysterectomies, Dr. Johnson would often share stories of when he was a resident back in the 1950s at the Chicago Maternity Center (CMC) and delivered babies for poor families on Chicago’s south side.

One of the stories Dr. Johnson told was about a time when he and another medical student were called to a home to “turn a baby that was stuck,” recalls Dr. Crystal, now a hospitalist at El Camino Hospital, which supports two campuses in Mountain View, Calif., and Los Gatos, Calif. They were going to administer ether, which is highly flammable, to the young mother to relax the uterus and help turn the baby, but then realized that a wood fire was burning. As the woman writhed in pain, they doused the flames with water.

“He said it was like Dante’s Inferno as smoke filled the room,” Dr. Crystal says. “It was quite the scene.”

Stories told by Dr. Johnson and other physicians who worked at the CMC during medical school or residency in the 1950s are legendary. They reflect a time in medicine when doctors not only made house calls, but also stayed in the family’s home until the baby was delivered, getting glimpses into the life of the poor. In an effort to preserve these stories, Dr. Crystal wanted to produce a one-hour PBS documentary called Catch the Baby. But financial realities set in, and she now plans to convert the stories into short vignettes that will be posted on a website by the same name for medical humanities classes.

“I thought, ‘Wow, this is an amazing part of history that shouldn’t be lost,’” says Dr. Crystal, who also supports a private practice. “The Chicago Maternity Center was an incredible place that, for almost 80 years, taught medical students how to be self-sufficient.

They learned “to count on their own skills and [find] ways of solving problems in very real situations when being sent out to these deliveries.”

Big Plans, No Budget

During her residency, Dr. Crystal videotaped approximately seven hours of interviews with Dr. Johnson about his experiences at CMC. She planned to write a book about the 80-something-year-old doctor, who still owns a ranch, ropes cattle, and, at one time, headed the California Beef Council; however, her job, growing family, and well, life, simply got in the way.

Then, in 2009, roughly a decade later, one of her patients mentioned that she knew a film crew who produced documentaries for PBS. Dr. Crystal asked for an introduction.

Members of the film crew were excited about the project. Their first task was to create a trailer for the documentary. They spent an entire day filming Dr. Johnson at his ranch telling stories about kitchen table deliveries in the slums and doing activities around the ranch, like roping cattle with a fellow cowboy—someone he actually delivered as a baby years ago. More film was later shot at the Santa Clara Valley Medical Center of Dr. Johnson performing a C-section and vaginal delivery with a resident and medical student.

The four-minute and 20-second trailer cost $37,000, she says, explaining that the money was mostly raised through donations from Dr. Johnson’s “cowboy friends” who also owned ranches in the area. It is still posted on the original website Dr. Crystal created: www.CatchTheBaby.com.

–Dr. Crystal

Now came the hard part—fundraising.

“I found out that I would have to raise between $650,000 and $700,000 to make a one-hour film,” Dr. Crystal says. “I tried, but I’m a doctor and don’t like asking people for money. I realized that probably wasn’t going to happen.”

But she wasn’t willing to abandon the project. So she turned her attention to YouTube, which, by then, had been online for four years. At the time, shorter videos were popular. Dr. Crystal had to develop a new plan.

Her current goal is to build a website that would highlight the CMC stories, which would be part of a medical humanities course at medical schools across the country. Medical students, residents, and other doctors could learn about the history of medicine and obstetrics. She says there are many lessons to be learned that don’t involve medical procedures, such as the impact of social and cultural issues on a physician’s ability to deliver healthcare.

“We need to look back on the important lessons the medical students learned at the CMC,” she says. “Not about how to do specific procedures, but how to interact with patients who may be very different from themselves.”

There seems to be plenty of interest in the topic; Dr. Crystal has since built a Twitter following of 5,700 people who read articles she tweets about medicine’s past, present, and future (@CatchTheBaby).

Still, she needs to build the website, edit the hours of film into short films, and then post them on the website with a study guide. The cost, she says, could run anywhere between $35,000 and $65,000.

“I don’t necessarily have to work with people who are PBS documentarians,” she says, adding that over recent years she has contacted several university film professors and students who turned down the project because it was too much to tackle. “I’d like to use a crowd-funding [platform like] Kickstarter or Indiegogo to raise the money, so I could edit the film.”

Meanwhile, Dr. Johnson is getting older and would enjoy seeing this project completed. So would his friends who helped pay for the trailer and original filming, says Dr. Crystal. Besides, she believes these stories can help new doctors better balance their focus between technology and face time with patients.

“Medical school education is changing quite a bit,” she says. “Despite advances in technology, we can’t forget we’re treating a human being first.”

Carol Patton is a freelance writer in Las Vegas.

When Ruth Ann Crystal, MD, performed her residency at Stanford University Medical Center more than 15 years ago, she often worked side by side in the operating room with one of her favorite professors, Bert Johnson, MD, a skilled surgeon and obstetrician. While performing vaginal hysterectomies, Dr. Johnson would often share stories of when he was a resident back in the 1950s at the Chicago Maternity Center (CMC) and delivered babies for poor families on Chicago’s south side.

One of the stories Dr. Johnson told was about a time when he and another medical student were called to a home to “turn a baby that was stuck,” recalls Dr. Crystal, now a hospitalist at El Camino Hospital, which supports two campuses in Mountain View, Calif., and Los Gatos, Calif. They were going to administer ether, which is highly flammable, to the young mother to relax the uterus and help turn the baby, but then realized that a wood fire was burning. As the woman writhed in pain, they doused the flames with water.

“He said it was like Dante’s Inferno as smoke filled the room,” Dr. Crystal says. “It was quite the scene.”

Stories told by Dr. Johnson and other physicians who worked at the CMC during medical school or residency in the 1950s are legendary. They reflect a time in medicine when doctors not only made house calls, but also stayed in the family’s home until the baby was delivered, getting glimpses into the life of the poor. In an effort to preserve these stories, Dr. Crystal wanted to produce a one-hour PBS documentary called Catch the Baby. But financial realities set in, and she now plans to convert the stories into short vignettes that will be posted on a website by the same name for medical humanities classes.

“I thought, ‘Wow, this is an amazing part of history that shouldn’t be lost,’” says Dr. Crystal, who also supports a private practice. “The Chicago Maternity Center was an incredible place that, for almost 80 years, taught medical students how to be self-sufficient.

They learned “to count on their own skills and [find] ways of solving problems in very real situations when being sent out to these deliveries.”

Big Plans, No Budget

During her residency, Dr. Crystal videotaped approximately seven hours of interviews with Dr. Johnson about his experiences at CMC. She planned to write a book about the 80-something-year-old doctor, who still owns a ranch, ropes cattle, and, at one time, headed the California Beef Council; however, her job, growing family, and well, life, simply got in the way.

Then, in 2009, roughly a decade later, one of her patients mentioned that she knew a film crew who produced documentaries for PBS. Dr. Crystal asked for an introduction.

Members of the film crew were excited about the project. Their first task was to create a trailer for the documentary. They spent an entire day filming Dr. Johnson at his ranch telling stories about kitchen table deliveries in the slums and doing activities around the ranch, like roping cattle with a fellow cowboy—someone he actually delivered as a baby years ago. More film was later shot at the Santa Clara Valley Medical Center of Dr. Johnson performing a C-section and vaginal delivery with a resident and medical student.

The four-minute and 20-second trailer cost $37,000, she says, explaining that the money was mostly raised through donations from Dr. Johnson’s “cowboy friends” who also owned ranches in the area. It is still posted on the original website Dr. Crystal created: www.CatchTheBaby.com.

–Dr. Crystal

Now came the hard part—fundraising.

“I found out that I would have to raise between $650,000 and $700,000 to make a one-hour film,” Dr. Crystal says. “I tried, but I’m a doctor and don’t like asking people for money. I realized that probably wasn’t going to happen.”

But she wasn’t willing to abandon the project. So she turned her attention to YouTube, which, by then, had been online for four years. At the time, shorter videos were popular. Dr. Crystal had to develop a new plan.

Her current goal is to build a website that would highlight the CMC stories, which would be part of a medical humanities course at medical schools across the country. Medical students, residents, and other doctors could learn about the history of medicine and obstetrics. She says there are many lessons to be learned that don’t involve medical procedures, such as the impact of social and cultural issues on a physician’s ability to deliver healthcare.

“We need to look back on the important lessons the medical students learned at the CMC,” she says. “Not about how to do specific procedures, but how to interact with patients who may be very different from themselves.”

There seems to be plenty of interest in the topic; Dr. Crystal has since built a Twitter following of 5,700 people who read articles she tweets about medicine’s past, present, and future (@CatchTheBaby).

Still, she needs to build the website, edit the hours of film into short films, and then post them on the website with a study guide. The cost, she says, could run anywhere between $35,000 and $65,000.

“I don’t necessarily have to work with people who are PBS documentarians,” she says, adding that over recent years she has contacted several university film professors and students who turned down the project because it was too much to tackle. “I’d like to use a crowd-funding [platform like] Kickstarter or Indiegogo to raise the money, so I could edit the film.”

Meanwhile, Dr. Johnson is getting older and would enjoy seeing this project completed. So would his friends who helped pay for the trailer and original filming, says Dr. Crystal. Besides, she believes these stories can help new doctors better balance their focus between technology and face time with patients.

“Medical school education is changing quite a bit,” she says. “Despite advances in technology, we can’t forget we’re treating a human being first.”

Carol Patton is a freelance writer in Las Vegas.

When Ruth Ann Crystal, MD, performed her residency at Stanford University Medical Center more than 15 years ago, she often worked side by side in the operating room with one of her favorite professors, Bert Johnson, MD, a skilled surgeon and obstetrician. While performing vaginal hysterectomies, Dr. Johnson would often share stories of when he was a resident back in the 1950s at the Chicago Maternity Center (CMC) and delivered babies for poor families on Chicago’s south side.

One of the stories Dr. Johnson told was about a time when he and another medical student were called to a home to “turn a baby that was stuck,” recalls Dr. Crystal, now a hospitalist at El Camino Hospital, which supports two campuses in Mountain View, Calif., and Los Gatos, Calif. They were going to administer ether, which is highly flammable, to the young mother to relax the uterus and help turn the baby, but then realized that a wood fire was burning. As the woman writhed in pain, they doused the flames with water.

“He said it was like Dante’s Inferno as smoke filled the room,” Dr. Crystal says. “It was quite the scene.”

Stories told by Dr. Johnson and other physicians who worked at the CMC during medical school or residency in the 1950s are legendary. They reflect a time in medicine when doctors not only made house calls, but also stayed in the family’s home until the baby was delivered, getting glimpses into the life of the poor. In an effort to preserve these stories, Dr. Crystal wanted to produce a one-hour PBS documentary called Catch the Baby. But financial realities set in, and she now plans to convert the stories into short vignettes that will be posted on a website by the same name for medical humanities classes.

“I thought, ‘Wow, this is an amazing part of history that shouldn’t be lost,’” says Dr. Crystal, who also supports a private practice. “The Chicago Maternity Center was an incredible place that, for almost 80 years, taught medical students how to be self-sufficient.

They learned “to count on their own skills and [find] ways of solving problems in very real situations when being sent out to these deliveries.”

Big Plans, No Budget

During her residency, Dr. Crystal videotaped approximately seven hours of interviews with Dr. Johnson about his experiences at CMC. She planned to write a book about the 80-something-year-old doctor, who still owns a ranch, ropes cattle, and, at one time, headed the California Beef Council; however, her job, growing family, and well, life, simply got in the way.

Then, in 2009, roughly a decade later, one of her patients mentioned that she knew a film crew who produced documentaries for PBS. Dr. Crystal asked for an introduction.

Members of the film crew were excited about the project. Their first task was to create a trailer for the documentary. They spent an entire day filming Dr. Johnson at his ranch telling stories about kitchen table deliveries in the slums and doing activities around the ranch, like roping cattle with a fellow cowboy—someone he actually delivered as a baby years ago. More film was later shot at the Santa Clara Valley Medical Center of Dr. Johnson performing a C-section and vaginal delivery with a resident and medical student.

The four-minute and 20-second trailer cost $37,000, she says, explaining that the money was mostly raised through donations from Dr. Johnson’s “cowboy friends” who also owned ranches in the area. It is still posted on the original website Dr. Crystal created: www.CatchTheBaby.com.

–Dr. Crystal

Now came the hard part—fundraising.

“I found out that I would have to raise between $650,000 and $700,000 to make a one-hour film,” Dr. Crystal says. “I tried, but I’m a doctor and don’t like asking people for money. I realized that probably wasn’t going to happen.”

But she wasn’t willing to abandon the project. So she turned her attention to YouTube, which, by then, had been online for four years. At the time, shorter videos were popular. Dr. Crystal had to develop a new plan.

Her current goal is to build a website that would highlight the CMC stories, which would be part of a medical humanities course at medical schools across the country. Medical students, residents, and other doctors could learn about the history of medicine and obstetrics. She says there are many lessons to be learned that don’t involve medical procedures, such as the impact of social and cultural issues on a physician’s ability to deliver healthcare.

“We need to look back on the important lessons the medical students learned at the CMC,” she says. “Not about how to do specific procedures, but how to interact with patients who may be very different from themselves.”

There seems to be plenty of interest in the topic; Dr. Crystal has since built a Twitter following of 5,700 people who read articles she tweets about medicine’s past, present, and future (@CatchTheBaby).

Still, she needs to build the website, edit the hours of film into short films, and then post them on the website with a study guide. The cost, she says, could run anywhere between $35,000 and $65,000.

“I don’t necessarily have to work with people who are PBS documentarians,” she says, adding that over recent years she has contacted several university film professors and students who turned down the project because it was too much to tackle. “I’d like to use a crowd-funding [platform like] Kickstarter or Indiegogo to raise the money, so I could edit the film.”

Meanwhile, Dr. Johnson is getting older and would enjoy seeing this project completed. So would his friends who helped pay for the trailer and original filming, says Dr. Crystal. Besides, she believes these stories can help new doctors better balance their focus between technology and face time with patients.

“Medical school education is changing quite a bit,” she says. “Despite advances in technology, we can’t forget we’re treating a human being first.”

Carol Patton is a freelance writer in Las Vegas.

Institute of Medicine Report Prompts Debate Over Graduate Medical Education Funding, Oversight

Ever since 1997, when the federal Balanced Budget Act froze Medicare’s overall funding for graduate medical education, debates have flared regularly over whether and how the U.S. government should support medical resident training.

Discussions about the possible redistribution of billions of dollars are bound to make people nervous, but the controversy reached a fever pitch in 2014 when the Institute of Medicine released a report penned by a 21-member committee that recommended significant—and contentious—changes to the existing graduate medical education (GME) financing and governance structure to “address current deficiencies and better shape the physician workforce for the future.”

Should Medicare shake up the system to redistribute existing training slots to where they’re needed most, as the report recommends? Should it instead lift its funding cap to avert a potential bottleneck in the physician pipeline, as several medical associations have requested? One year later, the report has gained little traction amid a largely unchanged status quo that few experts believe is ultimately sustainable. The continuing debate, however, has prompted fresh questions about whether the current GME structure is adequately supporting the nation’s healthcare needs and has spurred widespread agreement on the need for greater transparency, accountability, and innovation.

Deborah Powell, MD, dean emerita of the University of Minnesota Medical School and one of the report’s co-authors, says she has seen firsthand the challenges arising from a lack of physicians in multiple specialties, especially in rural areas. “We believed that simply adding new money to a system that is outdated would not solve the issues in physician education and physician workforce,” she says.

Some HM leaders and other physicians’ groups have cautiously welcomed the report’s focus on better equipping doctors for a rapidly changing reality.

“It wasn’t wrong for them to look at this,” says Darlene B. Tad-y, MD, FHM, chair of the SHM Physicians in Training Committee and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado in Denver. “And it’s probably not wrong for them to propose new ways to think about how we fund GME.”

In fact, she says, efforts to align such funding with healthcare funding in general could be timely in the face of added pressures like ensuring that new insurance beneficiaries have access to primary care.

Scott Sears, MD, FACP, MBA, chief clinical officer of Tacoma, Wash.-based hospitalist management firm Sound Physicians, says healthcare is also moving rapidly toward managing populations as part of team-based care that increases quality while lowering costs. So why not better align GME with innovative Medicare initiatives like bundled payments, he asks, and then use the savings to reward those training programs that accept the risk and achieve results?

“Shifting some of our education to match what Medicare is trying to drive out in the real world, I think, is long overdue,” Dr. Sears says.

Other groups, such as the Association of American Medical Colleges, however, contend that the report’s prescriptions are far less helpful than its diagnoses. “Politically, there’s just stuff in there for everybody to hate,” says Atul Grover, MD, PhD, FACP, FCCP, the AAMC’s chief public policy officer. “I think [the IOM report] did a decent job of pointing out some of the things that we want to improve moving forward, but I’m not sure that the answers are quite right.”

An Uneven Funding Landscape

The strong opinions engendered by the topic underscore the high stakes involved in GME. Every year, the federal government doles out about $15 billion for residency training, including about $10 billion from Medicare coffers. Medicare’s share is divided into two main funding streams that flow primarily to academic medical centers: direct graduate medical education (DGME) and indirect medical education (IME) payments. The first covers training expenses, while the second reimburses teaching hospitals that care for Medicare patients while training residents.

Some skeptics have questioned whether the government should be funding medical education at all, noting that the arrangement is utterly unique to the field. Advocates have countered that the funding concept was embedded in the original Medicare legislation and that it correctly recognized the added cost of offering GME training while providing more complex Medicare beneficiaries with specialty services.

Nearly everyone acknowledges that there are still enough residency slots for all U.S. graduates, but Dr. Grover says residency programs aren’t growing nearly fast enough to keep pace with medical school enrollment, creating a growing mismatch and a looming bottleneck in the supply chain. Compared to medical school numbers in 2002, for example, the AAMC says enrollment is on track to expand 29% by 2019, while osteopathic schools are set to expand by 162% over the same timeframe.

It wasn’t wrong for the [Institute of Medicine] to look at this. And it’s probably not wrong for them to propose new ways to think about how we fund GME.

—Darlene B. Tad-y, MD, FHM, assistant professor of medicine, University of Colorado, Denver, chair, SHM Physicians in Training Committee

Fundamentally, the idea is not a bad one, to say that programs that were more aligned with national needs and priorities in terms of how they train physicians would get more funding, and those that did not wouldn’t. I think the challenge is that the devil’s in the details of how you do that.

—Vikas Parekh, MD, FACP, SFHM, associate director, hospitalist program, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, chair, SHM Academic Hospitalist Committee

Despite the continued freeze in Medicare funding, many large medical institutions continue to add residency spots.

“We’ve been hundreds of residency positions over our cap for a very long time,” says Vikas Parekh, MD, FACP, SFHM, associate director of the hospitalist program at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. “The hospital funds them through hospital operating margin because in the net, they still view the investment as worthwhile.”

Alternatively, some non-university-based training programs have secured money from other sources to fund their residency positions, potentially creating new funding models for the future if the programs can demonstrate both quality and stability.

One key rationale for the IOM report’s proposed overhaul, however, is the longstanding and sizeable geographical disparity in Medicare’s per capita GME spending, which has skewed heavily toward the Northeast. A 2013 study, in fact, found that one-fifth of all DGME funding in 2010—an estimated $2 billion—went to New York State alone.1 Florida, which recently overtook New York as the third most populous state, received only one-eighth as much money. And Mississippi—the state with the lowest doctor-to-patient ratio—received only $22 million, or about one-ninetieth as much.

The IOM report also suggests that the long-standing GME payment plan has yielded little data on whether it actually accomplishes what it was designed to do: help establish a well-prepared medical workforce in a cost-effective way. In response, one major IOM recommendation is to maintain the overall level of Medicare support but tie some of the payments to performance to ensure oversight and accountability, and provide new incentives for innovation in the content and financing of training programs.

As with other CMS initiatives, however, getting everyone to agree on which quality metrics to use in evaluating GME training could take awhile. For example, should Medicare judge the performance of the trainees, the GME programs, or even the sponsoring institutions? Despite the proliferation of performance-based carrots and sticks elsewhere in healthcare, Dr. Tad-y says, such incentives may work less well for GME.

“One thing that’s inherent with trainees is that they’re trainees,” she says. “They’re not as efficient or as effective as someone who’s an expert, right? That’s why it’s training.”

Dr. Parekh, who also serves as chair of the SHM Academic Hospitalist Committee, agrees that finding the right outcome measures could be tough. “It gets very dicey, because how do you define who’s a good doctor?” he says. Currently, residents often are assessed via the reputation and history of the training program. “People say, ‘I know that the people coming out of that program are good because they’ve always been good, and it’s a reputable program and has a big name.’ But it’s not objective data,” he says.

Dr. Sears, of Sound Physicians, notes that it’s also often difficult to attribute patients to specific providers.

“Many times in graduate medical education, patients are going in and out of the program or in and out of the hospital, and how do you attribute?” he says. “I think it becomes very complex.”

A New Take on Transformation

Another IOM recommendation would create a single GME fund with two subsidiaries: an operational fund for ongoing support and a transformation fund. The latter fund would finance four new initiatives to:

- Develop and evaluate innovative GME programs;

- Determine and validate appropriate performance measures;

- Establish pilot projects to test out alternative payment methods; and

- Award new training positions based on priority disciplines—such as primary care—and underserved geographic areas.

A related recommendation seeks to modernize the GME payment methodology. For example, the committee urged Medicare to combine the indirect and direct funding streams into one payment based on a national per-resident amount and adjusted according to each location. In addition, the report endorsed performance-based payments based on the results of pilots launched under the transformation fund.

Dr. Sears says he appreciates the report’s effort to address shortfalls in primary care providers relative to specialists. “That’s not to say that specialty medicine isn’t incredibly important, because it is,” he says. “But I think incentivizing or reallocating spots to ensure that we have adequate primary care physician coverage throughout the country will have tremendous impact on the ability to care for an aging population in the United States, at least.”

I have had physicians tell me that they do not understand why our report said that there was not a physician shortage, and I try to point out that we did NOT say that. Rather, the report [and the committee] said that we could not find compelling evidence of an impending physician shortage and that physician workforce projections had been and are quite unreliable. —Deborah Powell, MD, dean emerita, University of Minnesota Medical School, IOM committee member

Shifting some of our [medical] education to match what Medicare is trying to drive out in the real world, I think, is long overdue. —Scott Sears, MD, FACP, MBA, chief clinical officer, Sound Physicians, Tacoma, Wash.

Dr. Parekh agrees, at least in part.

“Fundamentally, the idea is not a bad one, to say that programs that were more aligned with national needs and priorities in terms of how they train physicians would get more funding, and those that did not wouldn’t,” he says. “I think the challenge is that the devil’s in the details of how you do that.”

A priority-based GME system, he continues, could potentially influence what type of physicians are trained.

“In my mind, it’s not irrational to think that if GME funding was more targeted around expanding slots in certain specialties and not expanding slots in other specialties, that there would be some ability to influence the workforce,” Dr. Parekh says. Influencing where residents go may be more difficult, though a growing mismatch between medical graduates and available residency slots might add a new wrinkle to that debate, as well.

Currently, U.S. medical graduates fill only about 60% of residency slots for specialties like internal medicine—a main conduit for hospital medicine—while foreign graduates make up the remainder.

“So who’s the first that’s going to be squeezed out? It will be foreign medical graduates,” Dr. Parekh says. Many of those graduates come to the U.S. on J-1 visas, which carry a payback requirement: practicing in underserved areas. “One worry is, will rural and underserved areas suffer from a physician shortage because U.S. grads won’t want to work there after you start squeezing out all of the foreign medical grads?” he asks.

Clear Line of Sight?

Dr. Parekh also supports efforts to establish a clearer connection between the funding’s intent and where the money actually goes. The IOM report’s proposal to do so, however, raises yet another controversy around the true purpose of IME funding. Teaching hospitals argue that the money should continue to be used to reimburse them for the added costs of providing comprehensive and specialized care like level I trauma centers to their more complex Medicare patient populations.

Number one, [the IOM] came out and said, ‘We don’t know that there’s a shortage of physicians and we’re, if anything, going to remove money from the training system rather than putting in additional resources. We found that problematic, given all the evidence we have of the growing, aging population. —Atul Grover, MD, PhD, FACP, FCCP, chief public policy officer, Association of American Medical Colleges

A big part of the problem here is that people are free agents. If you make more residency spots, but the economics are such that people decide to become cardiologists because cardiologists make twice or more what hospitalists make, then you may have increased residency spots but [added only] a very small increment in the number of hospitalists. —Daniel Brotman, MD, FACP, SFHM, chair, SHM Education Committee, director, hospitalist program, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore

Accordingly, the AAMC panned the report’s recommendation to replace separate IME funding with a single fund directed toward the GME sponsoring institution and subdivided instead into the operational and transformation funds. Dr. Grover says setting up a transformation fund with new money would make sense, but not as a carve-out from existing support.

“You’re removing those resources from the system and not replacing them, which is a challenge,” he says.

Medical schools are more inclined to want the money directed toward training goals, especially if they are to be held accountable for GME outcomes. “Right now, the hospital gets it, and it’s basically somewhere in the bottom line,” Dr. Parekh says. “No one really knows where that money goes. There’s very little accountability or clarity of purpose for that dollar.”

Amid the ongoing debate, the call for more transparency and accountability in GME seems to be gaining the most ground. “I don’t see tons of downside from it,” Dr. Parekh says. “I think it sheds light on the current funding environment and makes people have to justify a little bit more what they’re doing with that money.”

Dr. Tad-y puts it this way: “If you made your own budget at home, the first thing you’d do is try to figure out where all your money goes and what you’re spending your money on.” If Medicare is concerned that its GME money isn’t being spent wisely, then, the first step would be to do some accounting. “And that means a little bit of transparency,” she says. “I don’t think that’s a bad thing, to know exactly what we’re paying for; that makes sense. I mean, we do that for everything else.”

SHM and most other medical associations also agree on the necessary goal of increasing the nation’s primary care capacity, even if they differ on the details of how best to do so. In the long run, however, some observers say growing the workforce—whether that of primary care providers or of hospitalists—may depend less on the total number of residency spots and more on the enthusiasm of program leadership and the attractiveness of job conditions such as salary and workload.

“A big part of the problem here is that people are free agents,” says Daniel Brotman, MD, FACP, SFHM, chair of the SHM Education Committee and director of the hospitalist program at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. “If you make more residency spots, but the economics are such that people decide to become cardiologists because cardiologists make twice or more what hospitalists make, then you may have increased residency spots but [added only] a very small increment in the number of hospitalists.”

Whatever happens, Dr. Parekh says hospitalists are well positioned to be integral parts of improving quality, accountability, and innovation in residency training programs.

“I think if more GME money is targeted toward the outcomes of the GME programs, hospitalists are going to be tapped to help with that work, in terms of training and broadening their skill sets,” he says. “So I think it’s a great opportunity.”

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

References

- Mullan F, Chen C, Steinmetz E. The geography of graduate medical education: imbalances signal need for new distribution policies. Health Aff. 2013;32(11):1914-1921.

Ever since 1997, when the federal Balanced Budget Act froze Medicare’s overall funding for graduate medical education, debates have flared regularly over whether and how the U.S. government should support medical resident training.

Discussions about the possible redistribution of billions of dollars are bound to make people nervous, but the controversy reached a fever pitch in 2014 when the Institute of Medicine released a report penned by a 21-member committee that recommended significant—and contentious—changes to the existing graduate medical education (GME) financing and governance structure to “address current deficiencies and better shape the physician workforce for the future.”

Should Medicare shake up the system to redistribute existing training slots to where they’re needed most, as the report recommends? Should it instead lift its funding cap to avert a potential bottleneck in the physician pipeline, as several medical associations have requested? One year later, the report has gained little traction amid a largely unchanged status quo that few experts believe is ultimately sustainable. The continuing debate, however, has prompted fresh questions about whether the current GME structure is adequately supporting the nation’s healthcare needs and has spurred widespread agreement on the need for greater transparency, accountability, and innovation.

Deborah Powell, MD, dean emerita of the University of Minnesota Medical School and one of the report’s co-authors, says she has seen firsthand the challenges arising from a lack of physicians in multiple specialties, especially in rural areas. “We believed that simply adding new money to a system that is outdated would not solve the issues in physician education and physician workforce,” she says.

Some HM leaders and other physicians’ groups have cautiously welcomed the report’s focus on better equipping doctors for a rapidly changing reality.

“It wasn’t wrong for them to look at this,” says Darlene B. Tad-y, MD, FHM, chair of the SHM Physicians in Training Committee and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado in Denver. “And it’s probably not wrong for them to propose new ways to think about how we fund GME.”

In fact, she says, efforts to align such funding with healthcare funding in general could be timely in the face of added pressures like ensuring that new insurance beneficiaries have access to primary care.

Scott Sears, MD, FACP, MBA, chief clinical officer of Tacoma, Wash.-based hospitalist management firm Sound Physicians, says healthcare is also moving rapidly toward managing populations as part of team-based care that increases quality while lowering costs. So why not better align GME with innovative Medicare initiatives like bundled payments, he asks, and then use the savings to reward those training programs that accept the risk and achieve results?

“Shifting some of our education to match what Medicare is trying to drive out in the real world, I think, is long overdue,” Dr. Sears says.

Other groups, such as the Association of American Medical Colleges, however, contend that the report’s prescriptions are far less helpful than its diagnoses. “Politically, there’s just stuff in there for everybody to hate,” says Atul Grover, MD, PhD, FACP, FCCP, the AAMC’s chief public policy officer. “I think [the IOM report] did a decent job of pointing out some of the things that we want to improve moving forward, but I’m not sure that the answers are quite right.”

An Uneven Funding Landscape

The strong opinions engendered by the topic underscore the high stakes involved in GME. Every year, the federal government doles out about $15 billion for residency training, including about $10 billion from Medicare coffers. Medicare’s share is divided into two main funding streams that flow primarily to academic medical centers: direct graduate medical education (DGME) and indirect medical education (IME) payments. The first covers training expenses, while the second reimburses teaching hospitals that care for Medicare patients while training residents.

Some skeptics have questioned whether the government should be funding medical education at all, noting that the arrangement is utterly unique to the field. Advocates have countered that the funding concept was embedded in the original Medicare legislation and that it correctly recognized the added cost of offering GME training while providing more complex Medicare beneficiaries with specialty services.

Nearly everyone acknowledges that there are still enough residency slots for all U.S. graduates, but Dr. Grover says residency programs aren’t growing nearly fast enough to keep pace with medical school enrollment, creating a growing mismatch and a looming bottleneck in the supply chain. Compared to medical school numbers in 2002, for example, the AAMC says enrollment is on track to expand 29% by 2019, while osteopathic schools are set to expand by 162% over the same timeframe.

It wasn’t wrong for the [Institute of Medicine] to look at this. And it’s probably not wrong for them to propose new ways to think about how we fund GME.

—Darlene B. Tad-y, MD, FHM, assistant professor of medicine, University of Colorado, Denver, chair, SHM Physicians in Training Committee

Fundamentally, the idea is not a bad one, to say that programs that were more aligned with national needs and priorities in terms of how they train physicians would get more funding, and those that did not wouldn’t. I think the challenge is that the devil’s in the details of how you do that.

—Vikas Parekh, MD, FACP, SFHM, associate director, hospitalist program, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, chair, SHM Academic Hospitalist Committee

Despite the continued freeze in Medicare funding, many large medical institutions continue to add residency spots.

“We’ve been hundreds of residency positions over our cap for a very long time,” says Vikas Parekh, MD, FACP, SFHM, associate director of the hospitalist program at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. “The hospital funds them through hospital operating margin because in the net, they still view the investment as worthwhile.”

Alternatively, some non-university-based training programs have secured money from other sources to fund their residency positions, potentially creating new funding models for the future if the programs can demonstrate both quality and stability.

One key rationale for the IOM report’s proposed overhaul, however, is the longstanding and sizeable geographical disparity in Medicare’s per capita GME spending, which has skewed heavily toward the Northeast. A 2013 study, in fact, found that one-fifth of all DGME funding in 2010—an estimated $2 billion—went to New York State alone.1 Florida, which recently overtook New York as the third most populous state, received only one-eighth as much money. And Mississippi—the state with the lowest doctor-to-patient ratio—received only $22 million, or about one-ninetieth as much.

The IOM report also suggests that the long-standing GME payment plan has yielded little data on whether it actually accomplishes what it was designed to do: help establish a well-prepared medical workforce in a cost-effective way. In response, one major IOM recommendation is to maintain the overall level of Medicare support but tie some of the payments to performance to ensure oversight and accountability, and provide new incentives for innovation in the content and financing of training programs.

As with other CMS initiatives, however, getting everyone to agree on which quality metrics to use in evaluating GME training could take awhile. For example, should Medicare judge the performance of the trainees, the GME programs, or even the sponsoring institutions? Despite the proliferation of performance-based carrots and sticks elsewhere in healthcare, Dr. Tad-y says, such incentives may work less well for GME.

“One thing that’s inherent with trainees is that they’re trainees,” she says. “They’re not as efficient or as effective as someone who’s an expert, right? That’s why it’s training.”

Dr. Parekh, who also serves as chair of the SHM Academic Hospitalist Committee, agrees that finding the right outcome measures could be tough. “It gets very dicey, because how do you define who’s a good doctor?” he says. Currently, residents often are assessed via the reputation and history of the training program. “People say, ‘I know that the people coming out of that program are good because they’ve always been good, and it’s a reputable program and has a big name.’ But it’s not objective data,” he says.

Dr. Sears, of Sound Physicians, notes that it’s also often difficult to attribute patients to specific providers.

“Many times in graduate medical education, patients are going in and out of the program or in and out of the hospital, and how do you attribute?” he says. “I think it becomes very complex.”

A New Take on Transformation

Another IOM recommendation would create a single GME fund with two subsidiaries: an operational fund for ongoing support and a transformation fund. The latter fund would finance four new initiatives to:

- Develop and evaluate innovative GME programs;

- Determine and validate appropriate performance measures;

- Establish pilot projects to test out alternative payment methods; and

- Award new training positions based on priority disciplines—such as primary care—and underserved geographic areas.

A related recommendation seeks to modernize the GME payment methodology. For example, the committee urged Medicare to combine the indirect and direct funding streams into one payment based on a national per-resident amount and adjusted according to each location. In addition, the report endorsed performance-based payments based on the results of pilots launched under the transformation fund.

Dr. Sears says he appreciates the report’s effort to address shortfalls in primary care providers relative to specialists. “That’s not to say that specialty medicine isn’t incredibly important, because it is,” he says. “But I think incentivizing or reallocating spots to ensure that we have adequate primary care physician coverage throughout the country will have tremendous impact on the ability to care for an aging population in the United States, at least.”

I have had physicians tell me that they do not understand why our report said that there was not a physician shortage, and I try to point out that we did NOT say that. Rather, the report [and the committee] said that we could not find compelling evidence of an impending physician shortage and that physician workforce projections had been and are quite unreliable. —Deborah Powell, MD, dean emerita, University of Minnesota Medical School, IOM committee member

Shifting some of our [medical] education to match what Medicare is trying to drive out in the real world, I think, is long overdue. —Scott Sears, MD, FACP, MBA, chief clinical officer, Sound Physicians, Tacoma, Wash.

Dr. Parekh agrees, at least in part.

“Fundamentally, the idea is not a bad one, to say that programs that were more aligned with national needs and priorities in terms of how they train physicians would get more funding, and those that did not wouldn’t,” he says. “I think the challenge is that the devil’s in the details of how you do that.”

A priority-based GME system, he continues, could potentially influence what type of physicians are trained.

“In my mind, it’s not irrational to think that if GME funding was more targeted around expanding slots in certain specialties and not expanding slots in other specialties, that there would be some ability to influence the workforce,” Dr. Parekh says. Influencing where residents go may be more difficult, though a growing mismatch between medical graduates and available residency slots might add a new wrinkle to that debate, as well.

Currently, U.S. medical graduates fill only about 60% of residency slots for specialties like internal medicine—a main conduit for hospital medicine—while foreign graduates make up the remainder.

“So who’s the first that’s going to be squeezed out? It will be foreign medical graduates,” Dr. Parekh says. Many of those graduates come to the U.S. on J-1 visas, which carry a payback requirement: practicing in underserved areas. “One worry is, will rural and underserved areas suffer from a physician shortage because U.S. grads won’t want to work there after you start squeezing out all of the foreign medical grads?” he asks.

Clear Line of Sight?

Dr. Parekh also supports efforts to establish a clearer connection between the funding’s intent and where the money actually goes. The IOM report’s proposal to do so, however, raises yet another controversy around the true purpose of IME funding. Teaching hospitals argue that the money should continue to be used to reimburse them for the added costs of providing comprehensive and specialized care like level I trauma centers to their more complex Medicare patient populations.

Number one, [the IOM] came out and said, ‘We don’t know that there’s a shortage of physicians and we’re, if anything, going to remove money from the training system rather than putting in additional resources. We found that problematic, given all the evidence we have of the growing, aging population. —Atul Grover, MD, PhD, FACP, FCCP, chief public policy officer, Association of American Medical Colleges

A big part of the problem here is that people are free agents. If you make more residency spots, but the economics are such that people decide to become cardiologists because cardiologists make twice or more what hospitalists make, then you may have increased residency spots but [added only] a very small increment in the number of hospitalists. —Daniel Brotman, MD, FACP, SFHM, chair, SHM Education Committee, director, hospitalist program, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore

Accordingly, the AAMC panned the report’s recommendation to replace separate IME funding with a single fund directed toward the GME sponsoring institution and subdivided instead into the operational and transformation funds. Dr. Grover says setting up a transformation fund with new money would make sense, but not as a carve-out from existing support.

“You’re removing those resources from the system and not replacing them, which is a challenge,” he says.

Medical schools are more inclined to want the money directed toward training goals, especially if they are to be held accountable for GME outcomes. “Right now, the hospital gets it, and it’s basically somewhere in the bottom line,” Dr. Parekh says. “No one really knows where that money goes. There’s very little accountability or clarity of purpose for that dollar.”

Amid the ongoing debate, the call for more transparency and accountability in GME seems to be gaining the most ground. “I don’t see tons of downside from it,” Dr. Parekh says. “I think it sheds light on the current funding environment and makes people have to justify a little bit more what they’re doing with that money.”

Dr. Tad-y puts it this way: “If you made your own budget at home, the first thing you’d do is try to figure out where all your money goes and what you’re spending your money on.” If Medicare is concerned that its GME money isn’t being spent wisely, then, the first step would be to do some accounting. “And that means a little bit of transparency,” she says. “I don’t think that’s a bad thing, to know exactly what we’re paying for; that makes sense. I mean, we do that for everything else.”

SHM and most other medical associations also agree on the necessary goal of increasing the nation’s primary care capacity, even if they differ on the details of how best to do so. In the long run, however, some observers say growing the workforce—whether that of primary care providers or of hospitalists—may depend less on the total number of residency spots and more on the enthusiasm of program leadership and the attractiveness of job conditions such as salary and workload.

“A big part of the problem here is that people are free agents,” says Daniel Brotman, MD, FACP, SFHM, chair of the SHM Education Committee and director of the hospitalist program at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. “If you make more residency spots, but the economics are such that people decide to become cardiologists because cardiologists make twice or more what hospitalists make, then you may have increased residency spots but [added only] a very small increment in the number of hospitalists.”

Whatever happens, Dr. Parekh says hospitalists are well positioned to be integral parts of improving quality, accountability, and innovation in residency training programs.

“I think if more GME money is targeted toward the outcomes of the GME programs, hospitalists are going to be tapped to help with that work, in terms of training and broadening their skill sets,” he says. “So I think it’s a great opportunity.”

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

References

- Mullan F, Chen C, Steinmetz E. The geography of graduate medical education: imbalances signal need for new distribution policies. Health Aff. 2013;32(11):1914-1921.

Ever since 1997, when the federal Balanced Budget Act froze Medicare’s overall funding for graduate medical education, debates have flared regularly over whether and how the U.S. government should support medical resident training.

Discussions about the possible redistribution of billions of dollars are bound to make people nervous, but the controversy reached a fever pitch in 2014 when the Institute of Medicine released a report penned by a 21-member committee that recommended significant—and contentious—changes to the existing graduate medical education (GME) financing and governance structure to “address current deficiencies and better shape the physician workforce for the future.”

Should Medicare shake up the system to redistribute existing training slots to where they’re needed most, as the report recommends? Should it instead lift its funding cap to avert a potential bottleneck in the physician pipeline, as several medical associations have requested? One year later, the report has gained little traction amid a largely unchanged status quo that few experts believe is ultimately sustainable. The continuing debate, however, has prompted fresh questions about whether the current GME structure is adequately supporting the nation’s healthcare needs and has spurred widespread agreement on the need for greater transparency, accountability, and innovation.

Deborah Powell, MD, dean emerita of the University of Minnesota Medical School and one of the report’s co-authors, says she has seen firsthand the challenges arising from a lack of physicians in multiple specialties, especially in rural areas. “We believed that simply adding new money to a system that is outdated would not solve the issues in physician education and physician workforce,” she says.

Some HM leaders and other physicians’ groups have cautiously welcomed the report’s focus on better equipping doctors for a rapidly changing reality.

“It wasn’t wrong for them to look at this,” says Darlene B. Tad-y, MD, FHM, chair of the SHM Physicians in Training Committee and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado in Denver. “And it’s probably not wrong for them to propose new ways to think about how we fund GME.”

In fact, she says, efforts to align such funding with healthcare funding in general could be timely in the face of added pressures like ensuring that new insurance beneficiaries have access to primary care.

Scott Sears, MD, FACP, MBA, chief clinical officer of Tacoma, Wash.-based hospitalist management firm Sound Physicians, says healthcare is also moving rapidly toward managing populations as part of team-based care that increases quality while lowering costs. So why not better align GME with innovative Medicare initiatives like bundled payments, he asks, and then use the savings to reward those training programs that accept the risk and achieve results?

“Shifting some of our education to match what Medicare is trying to drive out in the real world, I think, is long overdue,” Dr. Sears says.

Other groups, such as the Association of American Medical Colleges, however, contend that the report’s prescriptions are far less helpful than its diagnoses. “Politically, there’s just stuff in there for everybody to hate,” says Atul Grover, MD, PhD, FACP, FCCP, the AAMC’s chief public policy officer. “I think [the IOM report] did a decent job of pointing out some of the things that we want to improve moving forward, but I’m not sure that the answers are quite right.”

An Uneven Funding Landscape

The strong opinions engendered by the topic underscore the high stakes involved in GME. Every year, the federal government doles out about $15 billion for residency training, including about $10 billion from Medicare coffers. Medicare’s share is divided into two main funding streams that flow primarily to academic medical centers: direct graduate medical education (DGME) and indirect medical education (IME) payments. The first covers training expenses, while the second reimburses teaching hospitals that care for Medicare patients while training residents.

Some skeptics have questioned whether the government should be funding medical education at all, noting that the arrangement is utterly unique to the field. Advocates have countered that the funding concept was embedded in the original Medicare legislation and that it correctly recognized the added cost of offering GME training while providing more complex Medicare beneficiaries with specialty services.

Nearly everyone acknowledges that there are still enough residency slots for all U.S. graduates, but Dr. Grover says residency programs aren’t growing nearly fast enough to keep pace with medical school enrollment, creating a growing mismatch and a looming bottleneck in the supply chain. Compared to medical school numbers in 2002, for example, the AAMC says enrollment is on track to expand 29% by 2019, while osteopathic schools are set to expand by 162% over the same timeframe.

It wasn’t wrong for the [Institute of Medicine] to look at this. And it’s probably not wrong for them to propose new ways to think about how we fund GME.

—Darlene B. Tad-y, MD, FHM, assistant professor of medicine, University of Colorado, Denver, chair, SHM Physicians in Training Committee

Fundamentally, the idea is not a bad one, to say that programs that were more aligned with national needs and priorities in terms of how they train physicians would get more funding, and those that did not wouldn’t. I think the challenge is that the devil’s in the details of how you do that.

—Vikas Parekh, MD, FACP, SFHM, associate director, hospitalist program, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, chair, SHM Academic Hospitalist Committee

Despite the continued freeze in Medicare funding, many large medical institutions continue to add residency spots.

“We’ve been hundreds of residency positions over our cap for a very long time,” says Vikas Parekh, MD, FACP, SFHM, associate director of the hospitalist program at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. “The hospital funds them through hospital operating margin because in the net, they still view the investment as worthwhile.”

Alternatively, some non-university-based training programs have secured money from other sources to fund their residency positions, potentially creating new funding models for the future if the programs can demonstrate both quality and stability.

One key rationale for the IOM report’s proposed overhaul, however, is the longstanding and sizeable geographical disparity in Medicare’s per capita GME spending, which has skewed heavily toward the Northeast. A 2013 study, in fact, found that one-fifth of all DGME funding in 2010—an estimated $2 billion—went to New York State alone.1 Florida, which recently overtook New York as the third most populous state, received only one-eighth as much money. And Mississippi—the state with the lowest doctor-to-patient ratio—received only $22 million, or about one-ninetieth as much.

The IOM report also suggests that the long-standing GME payment plan has yielded little data on whether it actually accomplishes what it was designed to do: help establish a well-prepared medical workforce in a cost-effective way. In response, one major IOM recommendation is to maintain the overall level of Medicare support but tie some of the payments to performance to ensure oversight and accountability, and provide new incentives for innovation in the content and financing of training programs.

As with other CMS initiatives, however, getting everyone to agree on which quality metrics to use in evaluating GME training could take awhile. For example, should Medicare judge the performance of the trainees, the GME programs, or even the sponsoring institutions? Despite the proliferation of performance-based carrots and sticks elsewhere in healthcare, Dr. Tad-y says, such incentives may work less well for GME.

“One thing that’s inherent with trainees is that they’re trainees,” she says. “They’re not as efficient or as effective as someone who’s an expert, right? That’s why it’s training.”

Dr. Parekh, who also serves as chair of the SHM Academic Hospitalist Committee, agrees that finding the right outcome measures could be tough. “It gets very dicey, because how do you define who’s a good doctor?” he says. Currently, residents often are assessed via the reputation and history of the training program. “People say, ‘I know that the people coming out of that program are good because they’ve always been good, and it’s a reputable program and has a big name.’ But it’s not objective data,” he says.

Dr. Sears, of Sound Physicians, notes that it’s also often difficult to attribute patients to specific providers.

“Many times in graduate medical education, patients are going in and out of the program or in and out of the hospital, and how do you attribute?” he says. “I think it becomes very complex.”

A New Take on Transformation

Another IOM recommendation would create a single GME fund with two subsidiaries: an operational fund for ongoing support and a transformation fund. The latter fund would finance four new initiatives to:

- Develop and evaluate innovative GME programs;

- Determine and validate appropriate performance measures;

- Establish pilot projects to test out alternative payment methods; and

- Award new training positions based on priority disciplines—such as primary care—and underserved geographic areas.

A related recommendation seeks to modernize the GME payment methodology. For example, the committee urged Medicare to combine the indirect and direct funding streams into one payment based on a national per-resident amount and adjusted according to each location. In addition, the report endorsed performance-based payments based on the results of pilots launched under the transformation fund.

Dr. Sears says he appreciates the report’s effort to address shortfalls in primary care providers relative to specialists. “That’s not to say that specialty medicine isn’t incredibly important, because it is,” he says. “But I think incentivizing or reallocating spots to ensure that we have adequate primary care physician coverage throughout the country will have tremendous impact on the ability to care for an aging population in the United States, at least.”

I have had physicians tell me that they do not understand why our report said that there was not a physician shortage, and I try to point out that we did NOT say that. Rather, the report [and the committee] said that we could not find compelling evidence of an impending physician shortage and that physician workforce projections had been and are quite unreliable. —Deborah Powell, MD, dean emerita, University of Minnesota Medical School, IOM committee member

Shifting some of our [medical] education to match what Medicare is trying to drive out in the real world, I think, is long overdue. —Scott Sears, MD, FACP, MBA, chief clinical officer, Sound Physicians, Tacoma, Wash.

Dr. Parekh agrees, at least in part.

“Fundamentally, the idea is not a bad one, to say that programs that were more aligned with national needs and priorities in terms of how they train physicians would get more funding, and those that did not wouldn’t,” he says. “I think the challenge is that the devil’s in the details of how you do that.”

A priority-based GME system, he continues, could potentially influence what type of physicians are trained.

“In my mind, it’s not irrational to think that if GME funding was more targeted around expanding slots in certain specialties and not expanding slots in other specialties, that there would be some ability to influence the workforce,” Dr. Parekh says. Influencing where residents go may be more difficult, though a growing mismatch between medical graduates and available residency slots might add a new wrinkle to that debate, as well.

Currently, U.S. medical graduates fill only about 60% of residency slots for specialties like internal medicine—a main conduit for hospital medicine—while foreign graduates make up the remainder.

“So who’s the first that’s going to be squeezed out? It will be foreign medical graduates,” Dr. Parekh says. Many of those graduates come to the U.S. on J-1 visas, which carry a payback requirement: practicing in underserved areas. “One worry is, will rural and underserved areas suffer from a physician shortage because U.S. grads won’t want to work there after you start squeezing out all of the foreign medical grads?” he asks.

Clear Line of Sight?

Dr. Parekh also supports efforts to establish a clearer connection between the funding’s intent and where the money actually goes. The IOM report’s proposal to do so, however, raises yet another controversy around the true purpose of IME funding. Teaching hospitals argue that the money should continue to be used to reimburse them for the added costs of providing comprehensive and specialized care like level I trauma centers to their more complex Medicare patient populations.

Number one, [the IOM] came out and said, ‘We don’t know that there’s a shortage of physicians and we’re, if anything, going to remove money from the training system rather than putting in additional resources. We found that problematic, given all the evidence we have of the growing, aging population. —Atul Grover, MD, PhD, FACP, FCCP, chief public policy officer, Association of American Medical Colleges

A big part of the problem here is that people are free agents. If you make more residency spots, but the economics are such that people decide to become cardiologists because cardiologists make twice or more what hospitalists make, then you may have increased residency spots but [added only] a very small increment in the number of hospitalists. —Daniel Brotman, MD, FACP, SFHM, chair, SHM Education Committee, director, hospitalist program, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore

Accordingly, the AAMC panned the report’s recommendation to replace separate IME funding with a single fund directed toward the GME sponsoring institution and subdivided instead into the operational and transformation funds. Dr. Grover says setting up a transformation fund with new money would make sense, but not as a carve-out from existing support.

“You’re removing those resources from the system and not replacing them, which is a challenge,” he says.

Medical schools are more inclined to want the money directed toward training goals, especially if they are to be held accountable for GME outcomes. “Right now, the hospital gets it, and it’s basically somewhere in the bottom line,” Dr. Parekh says. “No one really knows where that money goes. There’s very little accountability or clarity of purpose for that dollar.”

Amid the ongoing debate, the call for more transparency and accountability in GME seems to be gaining the most ground. “I don’t see tons of downside from it,” Dr. Parekh says. “I think it sheds light on the current funding environment and makes people have to justify a little bit more what they’re doing with that money.”

Dr. Tad-y puts it this way: “If you made your own budget at home, the first thing you’d do is try to figure out where all your money goes and what you’re spending your money on.” If Medicare is concerned that its GME money isn’t being spent wisely, then, the first step would be to do some accounting. “And that means a little bit of transparency,” she says. “I don’t think that’s a bad thing, to know exactly what we’re paying for; that makes sense. I mean, we do that for everything else.”

SHM and most other medical associations also agree on the necessary goal of increasing the nation’s primary care capacity, even if they differ on the details of how best to do so. In the long run, however, some observers say growing the workforce—whether that of primary care providers or of hospitalists—may depend less on the total number of residency spots and more on the enthusiasm of program leadership and the attractiveness of job conditions such as salary and workload.

“A big part of the problem here is that people are free agents,” says Daniel Brotman, MD, FACP, SFHM, chair of the SHM Education Committee and director of the hospitalist program at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. “If you make more residency spots, but the economics are such that people decide to become cardiologists because cardiologists make twice or more what hospitalists make, then you may have increased residency spots but [added only] a very small increment in the number of hospitalists.”

Whatever happens, Dr. Parekh says hospitalists are well positioned to be integral parts of improving quality, accountability, and innovation in residency training programs.

“I think if more GME money is targeted toward the outcomes of the GME programs, hospitalists are going to be tapped to help with that work, in terms of training and broadening their skill sets,” he says. “So I think it’s a great opportunity.”

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

References

- Mullan F, Chen C, Steinmetz E. The geography of graduate medical education: imbalances signal need for new distribution policies. Health Aff. 2013;32(11):1914-1921.

Specialty Hospitalists May Be Coming to Your Hospital Soon

Nearly 20 years ago, Bob Wachter, MD, coined the term “hospitalist,” defining a new specialty caring for the hospitalized medical patient. Since that time, we’ve seen rapid growth in the numbers of physicians who identify themselves as hospitalists, dominated by training in internal medicine and, to a lesser extent, family practice and pediatrics.

But, what about other specialty hospitalists, trained in the medicine or surgical specialties? How much of a presence do they have in our institutions today and in which specialties? To help us better understand this, a new question in 2014 State of Hospital Medicine survey asked whether specialty hospitalists practice in your hospital or health system.

—Carolyn Sites, DO, FHM

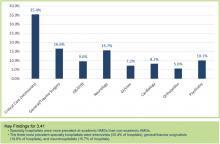

Results show the top three specialty hospitalists to be critical care, at (35.4%), followed by general surgery/trauma (16.6%) and neurology (15.7%), based on the responses of survey participants representing hospital medicine groups (HMGs) that care for adults only. Other specialties included obstetrics (OB), psychiatry, GI, cardiology, and orthopedics (see Figure 1).

Perhaps not too surprising, the greatest number of specialty hospitalists are found in university and academic settings. These are our primary training centers, offering fellowship programs and further subspecialization programs. Much like in our own field of hospital medicine, some academic centers have created one-year fellowships for those interested in specific hospital specialty fields, such as OB hospitalist.

For reasons that are less clear, the survey also shows percentages are highest in the western U.S. and lowest in the East.

Critical care hospitalists, also known as intensivists, dominate the spectrum, being present in academic and nonacademic centers, regardless of the employment model of the medical hospitalists at those facilities. This is not unexpected, given the Leapfrog Group’s endorsement of ICU physician staffing with intensivists.

What’s driving the other specialty hospitalist fields? I suspect the reasons are similar to those of our own specialty. OB and neuro hospitalists at my health system cite the challenges of managing outpatient and inpatient practices, the higher inpatient acuity and focused skill set that are required, immediate availability demands, and work-life balance as key factors. Further drivers include external quality/safety governing agencies or groups, such as the Leapfrog example above, or The Joint Commission’s requirements for certification as a Comprehensive Stroke Center with neurointensive care units.

Much like our own field’s exponential growth, we are likely to see further expansion of specialty hospitalists over the next several years. It will be interesting to watch how much and how fast this occurs, and what impact and influence these groups will bring to the care of the hospitalized patient. I’m already looking forward to next year’s SOHM report to see those results.

Dr. Sites is regional medical director of hospital medicine at Providence Health Systems in Oregon and a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee.

Nearly 20 years ago, Bob Wachter, MD, coined the term “hospitalist,” defining a new specialty caring for the hospitalized medical patient. Since that time, we’ve seen rapid growth in the numbers of physicians who identify themselves as hospitalists, dominated by training in internal medicine and, to a lesser extent, family practice and pediatrics.

But, what about other specialty hospitalists, trained in the medicine or surgical specialties? How much of a presence do they have in our institutions today and in which specialties? To help us better understand this, a new question in 2014 State of Hospital Medicine survey asked whether specialty hospitalists practice in your hospital or health system.

—Carolyn Sites, DO, FHM

Results show the top three specialty hospitalists to be critical care, at (35.4%), followed by general surgery/trauma (16.6%) and neurology (15.7%), based on the responses of survey participants representing hospital medicine groups (HMGs) that care for adults only. Other specialties included obstetrics (OB), psychiatry, GI, cardiology, and orthopedics (see Figure 1).

Perhaps not too surprising, the greatest number of specialty hospitalists are found in university and academic settings. These are our primary training centers, offering fellowship programs and further subspecialization programs. Much like in our own field of hospital medicine, some academic centers have created one-year fellowships for those interested in specific hospital specialty fields, such as OB hospitalist.

For reasons that are less clear, the survey also shows percentages are highest in the western U.S. and lowest in the East.

Critical care hospitalists, also known as intensivists, dominate the spectrum, being present in academic and nonacademic centers, regardless of the employment model of the medical hospitalists at those facilities. This is not unexpected, given the Leapfrog Group’s endorsement of ICU physician staffing with intensivists.

What’s driving the other specialty hospitalist fields? I suspect the reasons are similar to those of our own specialty. OB and neuro hospitalists at my health system cite the challenges of managing outpatient and inpatient practices, the higher inpatient acuity and focused skill set that are required, immediate availability demands, and work-life balance as key factors. Further drivers include external quality/safety governing agencies or groups, such as the Leapfrog example above, or The Joint Commission’s requirements for certification as a Comprehensive Stroke Center with neurointensive care units.

Much like our own field’s exponential growth, we are likely to see further expansion of specialty hospitalists over the next several years. It will be interesting to watch how much and how fast this occurs, and what impact and influence these groups will bring to the care of the hospitalized patient. I’m already looking forward to next year’s SOHM report to see those results.

Dr. Sites is regional medical director of hospital medicine at Providence Health Systems in Oregon and a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee.

Nearly 20 years ago, Bob Wachter, MD, coined the term “hospitalist,” defining a new specialty caring for the hospitalized medical patient. Since that time, we’ve seen rapid growth in the numbers of physicians who identify themselves as hospitalists, dominated by training in internal medicine and, to a lesser extent, family practice and pediatrics.

But, what about other specialty hospitalists, trained in the medicine or surgical specialties? How much of a presence do they have in our institutions today and in which specialties? To help us better understand this, a new question in 2014 State of Hospital Medicine survey asked whether specialty hospitalists practice in your hospital or health system.

—Carolyn Sites, DO, FHM

Results show the top three specialty hospitalists to be critical care, at (35.4%), followed by general surgery/trauma (16.6%) and neurology (15.7%), based on the responses of survey participants representing hospital medicine groups (HMGs) that care for adults only. Other specialties included obstetrics (OB), psychiatry, GI, cardiology, and orthopedics (see Figure 1).

Perhaps not too surprising, the greatest number of specialty hospitalists are found in university and academic settings. These are our primary training centers, offering fellowship programs and further subspecialization programs. Much like in our own field of hospital medicine, some academic centers have created one-year fellowships for those interested in specific hospital specialty fields, such as OB hospitalist.

For reasons that are less clear, the survey also shows percentages are highest in the western U.S. and lowest in the East.

Critical care hospitalists, also known as intensivists, dominate the spectrum, being present in academic and nonacademic centers, regardless of the employment model of the medical hospitalists at those facilities. This is not unexpected, given the Leapfrog Group’s endorsement of ICU physician staffing with intensivists.