User login

Acknowledgment

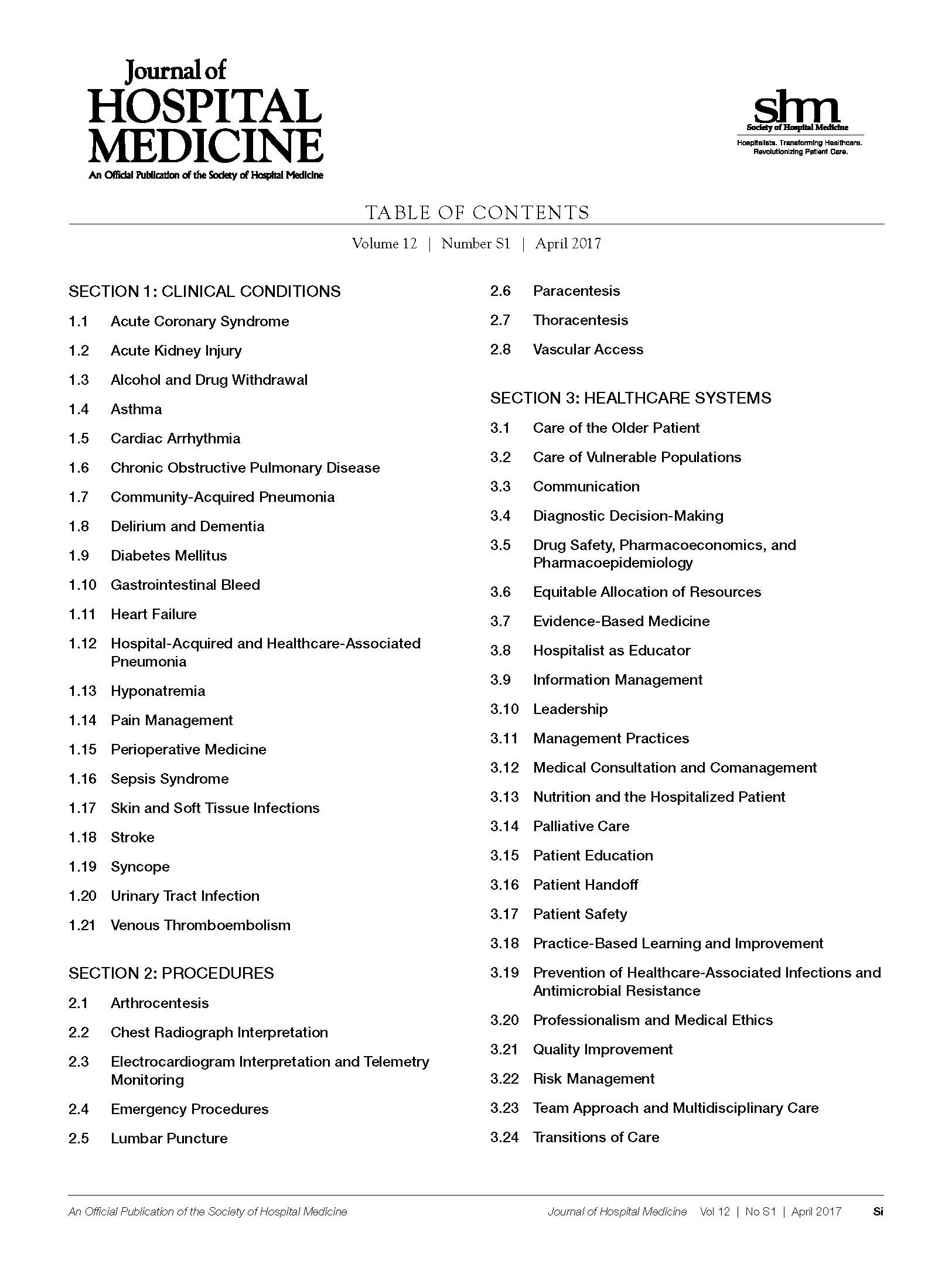

Core Competencies Table of Contents

The Revised Edition of The Core Competencies would not have been possible without the support and assistance of the Society of Hospital Medicine staff and countless practicing Hospitalists across the United States. The editors thank Nick Marzano for project coordination. Special thanks to Abbie Young for her thorough medical editing and updates to chapter introductions. The editors also thank their families for all their patience and support throughout the development process.

Society of Hospital Medicine leadership and subject matter experts who provided content, review and guidance include:

CHAPTER AUTHORS

Alberto Puig, MD, PhD, FACP, SFHM

Jeffrey Genato, MD, SFHM, UHM

Lorenzo Difrancesco, MD

Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, MACP, SFHM

Nurcan Ilksoy, MD, FHM

John David Halporn, MD

Eugene Chu, MD, FHM

Brian Donovan, MD, SFHM

Alexander Carbo, MD, SFHM

Valeria Lang, MD, FHM

David Feinbloom, MD, SFHM

Richard Rohr, MD, SFHM

Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD, SFHM

Vijay Rajput, MBBS, FACP, SFHM

Tosha Wetterneck, MD, SFHM

Michael Ruhlen, MD, FAAP, FACHE, MHSc

Gregory Seymann, MD, SFHM

Jeffrey Barsuk, MD, SFHM

David J. Likosky, MD, FACP

Bindu Sangani, MD

Scott Flanders, MD, FACP, MHM

Chad Whelan, MD, FACP, FHM

Shaun Frost, MD, SFHM

Amir Jaffer, MD, MBA, SFHM

Michael Lukela, MD, SFHM, FACP, FAAP

Jonathan Crocker, MD, FHM

CORE COMPETENCIES TASK FORCE (2012-2016)

Satyen Nichani, MD, FHM (Chair)

Nick Fitterman, MD, SFHM, FACP

Michael Lukela, MD, SFHM, FACP, FAAP

Jonathan Crocker, MD, FHM

Tarun Ghosh, MD, FRCS, SFHM

Vikas Parekh, MD, FACP, SFHM

Nick Marzano, MEd

SHM EDUCATION COMMITTEE REVIEWERS

Jessie Kimbrough-Sugick, MD, MPH

Danielle Scheurer, MD, SFHM, MSCR

Amit Pahwa, MD

Anthony Breu, MD

Nathan Houchens, MD, FACP, FHM

Jeffrey Bates, MD, FACP, FHM

Ian Jenkins, MD, SFHM

Neel Shah, MB, BCh, SFHM

Elizabeth Cerceo, MD, FACP, FHM

Jeffrey Greenwald, MD, SFHM

Haruka Torok, MD, SFHM

Bartho Caponi, MD, FHM

Leonard Feldman, MD, FACP, FAAP, SFHM

Daniel Brotman, MD, SFHM

Alfred Burger, MD, SFHM

Jocelyn Carter, MD, MPH

Vinh-Tung Nguyen, MD

Kurt Pfeifer, MD, FACP, SFHM

Alberto Puig, MD, PhD, FACP, SFHM

Richard Vestal, MD

Judy Vu, MD, FAAP

CONTENT EXPERTS

Jason Persoff, MD, SFHM

Nilam Soni, MD, FHM

Lynnea Mills, MD

Wendy Anderson, MD, MS

Jeffrey Frank, MD, FACP, MBA

Howard Epstein, MD, SFHM, CHIE

Kendall Rogers, MD, SFHM

Prateek Gandiga, MD, FACP

Jeffrey Glasheen, MD, SFHM

Melissa Mattison, MD, SFHM

Vineet Arora, MD, MPP, MHM

Peter Lindenauer, MD, MSc, FACP, MHM

Tomas Villanueva, DO, MBA, SFHM

Ethan Cumbler, MD, FACP, FHM

Vineet Chopra, MD, MSc, FHM

Core Competencies Table of Contents

The Revised Edition of The Core Competencies would not have been possible without the support and assistance of the Society of Hospital Medicine staff and countless practicing Hospitalists across the United States. The editors thank Nick Marzano for project coordination. Special thanks to Abbie Young for her thorough medical editing and updates to chapter introductions. The editors also thank their families for all their patience and support throughout the development process.

Society of Hospital Medicine leadership and subject matter experts who provided content, review and guidance include:

CHAPTER AUTHORS

Alberto Puig, MD, PhD, FACP, SFHM

Jeffrey Genato, MD, SFHM, UHM

Lorenzo Difrancesco, MD

Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, MACP, SFHM

Nurcan Ilksoy, MD, FHM

John David Halporn, MD

Eugene Chu, MD, FHM

Brian Donovan, MD, SFHM

Alexander Carbo, MD, SFHM

Valeria Lang, MD, FHM

David Feinbloom, MD, SFHM

Richard Rohr, MD, SFHM

Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD, SFHM

Vijay Rajput, MBBS, FACP, SFHM

Tosha Wetterneck, MD, SFHM

Michael Ruhlen, MD, FAAP, FACHE, MHSc

Gregory Seymann, MD, SFHM

Jeffrey Barsuk, MD, SFHM

David J. Likosky, MD, FACP

Bindu Sangani, MD

Scott Flanders, MD, FACP, MHM

Chad Whelan, MD, FACP, FHM

Shaun Frost, MD, SFHM

Amir Jaffer, MD, MBA, SFHM

Michael Lukela, MD, SFHM, FACP, FAAP

Jonathan Crocker, MD, FHM

CORE COMPETENCIES TASK FORCE (2012-2016)

Satyen Nichani, MD, FHM (Chair)

Nick Fitterman, MD, SFHM, FACP

Michael Lukela, MD, SFHM, FACP, FAAP

Jonathan Crocker, MD, FHM

Tarun Ghosh, MD, FRCS, SFHM

Vikas Parekh, MD, FACP, SFHM

Nick Marzano, MEd

SHM EDUCATION COMMITTEE REVIEWERS

Jessie Kimbrough-Sugick, MD, MPH

Danielle Scheurer, MD, SFHM, MSCR

Amit Pahwa, MD

Anthony Breu, MD

Nathan Houchens, MD, FACP, FHM

Jeffrey Bates, MD, FACP, FHM

Ian Jenkins, MD, SFHM

Neel Shah, MB, BCh, SFHM

Elizabeth Cerceo, MD, FACP, FHM

Jeffrey Greenwald, MD, SFHM

Haruka Torok, MD, SFHM

Bartho Caponi, MD, FHM

Leonard Feldman, MD, FACP, FAAP, SFHM

Daniel Brotman, MD, SFHM

Alfred Burger, MD, SFHM

Jocelyn Carter, MD, MPH

Vinh-Tung Nguyen, MD

Kurt Pfeifer, MD, FACP, SFHM

Alberto Puig, MD, PhD, FACP, SFHM

Richard Vestal, MD

Judy Vu, MD, FAAP

CONTENT EXPERTS

Jason Persoff, MD, SFHM

Nilam Soni, MD, FHM

Lynnea Mills, MD

Wendy Anderson, MD, MS

Jeffrey Frank, MD, FACP, MBA

Howard Epstein, MD, SFHM, CHIE

Kendall Rogers, MD, SFHM

Prateek Gandiga, MD, FACP

Jeffrey Glasheen, MD, SFHM

Melissa Mattison, MD, SFHM

Vineet Arora, MD, MPP, MHM

Peter Lindenauer, MD, MSc, FACP, MHM

Tomas Villanueva, DO, MBA, SFHM

Ethan Cumbler, MD, FACP, FHM

Vineet Chopra, MD, MSc, FHM

Core Competencies Table of Contents

The Revised Edition of The Core Competencies would not have been possible without the support and assistance of the Society of Hospital Medicine staff and countless practicing Hospitalists across the United States. The editors thank Nick Marzano for project coordination. Special thanks to Abbie Young for her thorough medical editing and updates to chapter introductions. The editors also thank their families for all their patience and support throughout the development process.

Society of Hospital Medicine leadership and subject matter experts who provided content, review and guidance include:

CHAPTER AUTHORS

Alberto Puig, MD, PhD, FACP, SFHM

Jeffrey Genato, MD, SFHM, UHM

Lorenzo Difrancesco, MD

Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, MACP, SFHM

Nurcan Ilksoy, MD, FHM

John David Halporn, MD

Eugene Chu, MD, FHM

Brian Donovan, MD, SFHM

Alexander Carbo, MD, SFHM

Valeria Lang, MD, FHM

David Feinbloom, MD, SFHM

Richard Rohr, MD, SFHM

Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD, SFHM

Vijay Rajput, MBBS, FACP, SFHM

Tosha Wetterneck, MD, SFHM

Michael Ruhlen, MD, FAAP, FACHE, MHSc

Gregory Seymann, MD, SFHM

Jeffrey Barsuk, MD, SFHM

David J. Likosky, MD, FACP

Bindu Sangani, MD

Scott Flanders, MD, FACP, MHM

Chad Whelan, MD, FACP, FHM

Shaun Frost, MD, SFHM

Amir Jaffer, MD, MBA, SFHM

Michael Lukela, MD, SFHM, FACP, FAAP

Jonathan Crocker, MD, FHM

CORE COMPETENCIES TASK FORCE (2012-2016)

Satyen Nichani, MD, FHM (Chair)

Nick Fitterman, MD, SFHM, FACP

Michael Lukela, MD, SFHM, FACP, FAAP

Jonathan Crocker, MD, FHM

Tarun Ghosh, MD, FRCS, SFHM

Vikas Parekh, MD, FACP, SFHM

Nick Marzano, MEd

SHM EDUCATION COMMITTEE REVIEWERS

Jessie Kimbrough-Sugick, MD, MPH

Danielle Scheurer, MD, SFHM, MSCR

Amit Pahwa, MD

Anthony Breu, MD

Nathan Houchens, MD, FACP, FHM

Jeffrey Bates, MD, FACP, FHM

Ian Jenkins, MD, SFHM

Neel Shah, MB, BCh, SFHM

Elizabeth Cerceo, MD, FACP, FHM

Jeffrey Greenwald, MD, SFHM

Haruka Torok, MD, SFHM

Bartho Caponi, MD, FHM

Leonard Feldman, MD, FACP, FAAP, SFHM

Daniel Brotman, MD, SFHM

Alfred Burger, MD, SFHM

Jocelyn Carter, MD, MPH

Vinh-Tung Nguyen, MD

Kurt Pfeifer, MD, FACP, SFHM

Alberto Puig, MD, PhD, FACP, SFHM

Richard Vestal, MD

Judy Vu, MD, FAAP

CONTENT EXPERTS

Jason Persoff, MD, SFHM

Nilam Soni, MD, FHM

Lynnea Mills, MD

Wendy Anderson, MD, MS

Jeffrey Frank, MD, FACP, MBA

Howard Epstein, MD, SFHM, CHIE

Kendall Rogers, MD, SFHM

Prateek Gandiga, MD, FACP

Jeffrey Glasheen, MD, SFHM

Melissa Mattison, MD, SFHM

Vineet Arora, MD, MPP, MHM

Peter Lindenauer, MD, MSc, FACP, MHM

Tomas Villanueva, DO, MBA, SFHM

Ethan Cumbler, MD, FACP, FHM

Vineet Chopra, MD, MSc, FHM

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Updating the core competencies in hospital medicine—2017 revision: Introduction and methodology

In 2006, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) first published The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: A Framework for Curricular Development (henceforth described as the Core Competencies) to help define the role and expectations of hospitalists.1,2 The Core Competencies provided a framework for evaluating clinical skills and professional expertise within a rapidly developing field and highlighted opportunities for growth. Since the initial development and publication of the Core Competencies, changes in the healthcare landscape and hospitalist practice environment have prompted this revision.

Over the past decade, the field of hospital medicine has experienced exponential growth. In 2005, just over 16,000 hospitalists were practicing in the United States. By 2015, that number had increased to an estimated 44,000 hospitalists, accounting for approximately 6% of the physician workforce.3 Hospitalists have expanded the scope of hospital medicine in many ways. In their roles, hospitalists lead and participate in hospital-based care models that emphasize interprofessional collaboration and a focus on the delivery of high-quality and cost-effective care across a variety of clinical domains (eg, the Choosing Wisely initiative).4 They are also engaged in patient safety and quality initiatives that are increasingly being used as benchmarks to rate hospitals and as factors for hospital payment (eg, Hospital Inpatient Value-Based Purchasing Program).5 In fact, the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) created a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine Maintenance of Certification program in response to the growing number of internists choosing to concentrate their practice in the hospital setting. This decision by the ABIM underscores the value that hospitalists bring to improving patient care in the hospital setting. The ABIM also recognizes the Core Competencies as a curricular framework for a focused practice in hospital medicine.6

Changes within the educational environment have demanded attentive and active participation by many hospitalists. For example, in 2012, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) introduced the Milestones Project, a new outcomes-based framework designed to more effectively assess learner performance across the 6 core competencies.7 These milestones assessments create intentional opportunities to guide the development of physicians during their training, including in the inpatient environments in which hospitalists practice. Where applicable, existing Core Competencies learning objectives were compared with external sources such as the individual ACGME performance milestones for this revision.

THE CORE COMPETENCIES

The Core Competencies focus on adult hospital medicine. The Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies are published separately.8 Importantly, the Core Competencies document is not intended to define an absolute set of clinical, procedural, or system-based topics described in textbooks or used by graduate medical education training programs. It does not define or limit the scope of the practice of hospital medicine. Rather, the Core Competencies serve as measurable learning objectives that encourage teaching faculty, practicing hospitalists, and administrators to develop individual skill sets and programs to improve patient care contextualized to the needs of an individual, care setting, or institution. To permit this flexibility, individual chapter-specific objectives are intentionally general in nature. Finally, the Core Competencies document is not a set of practice guidelines, nor does it offer any representation of a “standard of care.” Readers are encouraged to explore the article by McKean et al.9 to review examples of application of the Core Competencies and suggestions for curricular development.

The purpose of this article is to describe the criteria for inclusion of new chapters in the Core Competencies and the methodology of the review and revision process. It outlines the process of initial review and editing of the existing chapters; needs assessment for new topics; new chapter production; and the process of review and revision of individual chapters to create the complete document. The revised Core Competencies document is available online at http://www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com/jhospmed/issue/134981/journal-hospital-medicine-124-suppl-1.

REVIEW AND REVISION PROCESS

In 2012, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Education Committee created a Core Competencies Task Force (CCTF) in response to the SHM Board of Directors’ charge that it review and update the initial Core Competencies document. The CCTF comprised of 5 physician SHM Education Committee members and one SHM staff representative. CCTF membership included hospitalists with an interest and familiarity with the Core Competencies document. The SHM Education Committee nominated the CCTF chair, who determined the optimal size, qualifications, and composition of the task force with approval from the Committee. The CCTF communicated through frequent conference calls and via e-mail correspondence to conduct an initial review of the existing chapters and to perform a needs assessment for new topics.

Individual Chapter Review

The SHM Education Committee provided critical input and approved the chapter review process designed by the CCTF (Figure). The CCTF reviewed each chapter of the Core Competencies document to assess its continuing relevance to the field of hospital medicine with a standardized tool (Appendix 1). The process required that at least 2 CCTF members reviewed each chapter. Preliminary reviewers assessed the current relevance of each chapter, determined whether individual learning objectives required additional investigation or modification, and developed new learning objectives to fill any educational gaps. All CCTF members then discussed assimilated feedback from the initial CCTF review, using consensus decision making to determine chapter changes and modifications. The CCTF found each of the existing chapters to be relevant to the field and identified none for removal.

The CCTF rewrote all chapters. It then disseminated proposed chapter changes to a panel of diverse independent reviewers to solicit suggestions and comments to ensure a multidisciplinary and balanced review process. Independent reviewers included authors of the original Core Competencies chapters, invited content experts, and members of the SHM Education Committee. When appropriate, corresponding SHM Committees reviewed individual chapters for updates and revisions. For example, the SHM Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee reviewed the chapters on patient safety and quality improvement, and the SHM Practice Management Committee reviewed the chapter on management practices. Four CCTF section editors managed an independent portfolio of chapters. Each CCTF section editor assimilated the various draft versions, corresponded with individual reviewers when necessary, and compiled the changes into a subsequent draft. This process ensured that the final version of every chapter reflected the thoughtful input from all parties involved in the review. Throughout the process, the CCTF used consensus decision making to adjudicate chapter changes and modifications. The 2006 Core Competencies Editorial team also reviewed the revision and provided critical input. The SHM Education Committee and the SHM Board of Directors reviewed and approved the final version of the Core Competencies document.

Needs Assessment and Selection of New Core Competency Chapters

The CCTF issued a call for new topics to the members of the SHM Education Committee for inclusion in the Core Competencies. Topics were also identified from the following sources: the top 100 adult medical diagnoses at hospital discharge in the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project database in 2010; topics in hospital medicine textbooks; curricula presented at the 3 most recent SHM annual meetings; and responses from SHM annual meeting surveys. Table 1 lists the topics considered for addition.

Members of the SHM Education Committee rated each of the potential topics considered for inclusion based on the following characteristics: relevance to the field of hospital medicine; intersection of the topic with medical subspecialties; and its appropriateness as a separate, stand-alone chapter. In addition, topics more frequently encountered by hospitalists, those deemed clinically important with a known risk of complications or management inconsistencies, and those with significant opportunities for quality improvement initiatives carried more weight. Syncope and hyponatremia were the only 2 clinical conditions identified that met all of the inclusion criteria. No additional topics met the criteria for new chapter development in the Procedures or Healthcare Systems sections. The SHM Education Committee identified the use of point-of-care ultrasonography as an important advancement in the field. Where appropriate, the individual procedure chapters now include a new competency-based objective highlighting its role. In addition, a separate SHM task force is working to develop a practice guideline for the use of point-of-care ultrasonography by hospitalists.

Contributors

The SHM Education Committee determined authorship for the new chapters (syncope and hyponatremia). It assigned 2 CCTF members with content expertise and familiarity with the Core Competencies to each author one chapter. Given the limited number of new chapters, it made a decision to develop the content internally rather than through an open-call for authorship nominations to practicing SHM members. The authors made an effort to maintain consistency with the educational theory used to develop the initial Core Competencies. Each of the new topics underwent rigorous review as previously described, including additional independent reviews by hospitalists with content expertise in these areas.

CHAPTER FORMAT AND CONTENT CHANGES

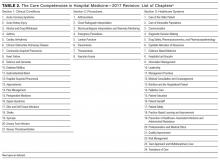

Following the same format as the earlier version, the 2017 Core Competencies revision contains 53 chapters, divided into 3 sections—Clinical Conditions, Procedures, and Healthcare Systems (Table 2) —all integral components of the practice of hospital medicine. The design allows individual chapters to stand alone. However, each chapter should be considered in the context of the entire document because a particular concept may be only briefly discussed in one chapter, but described in greater depth in another given the potential overlap across topics.

The chapters maintain the same content structure as the original version. Each chapter begins with an introductory paragraph followed by a list of competency-based objectives grouped in subsections according to the educational theory of learning domains: cognitive (knowledge), psychomotor (skills), and affective (attitudes).10 In addition, a subsection for System Organization and Improvement is included in the Clinical Conditions and Procedure chapters to emphasize the importance of interprofessional collaboration for optimal patient care. These subsections were not included in the Healthcare Systems chapters, as system organization and improvement is intrinsic to these subjects.

The introductory paragraph provides background information and describes how the chapter remains relevant to the current practice of hospital medicine. Individual competency-based objectives outline a relevant concept and expected level of proficiency as defined by Bloom’s taxonomy.10 New objectives reflect changes in the healthcare landscape over the past decade or further enhance each chapter’s concepts. Chapter authors made an effort to develop chapter and learning objective concepts that are consistent with external resources such as the ACGME Milestones Project and practice guideline objectives developed by a variety of professional organizations.

SUMMARY AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

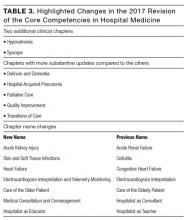

The Core Competencies document serves as a resource for hospitalists and hospital medicine programs to evaluate, develop, and improve individual and collective skills and the practice environment. The Core Competencies also provide a framework for medical school clerkship directors and residency and fellowship program directors, as well as course directors of Continuing Medical Education programs, to develop curricula to enhance educational experiences for trainees and hospital medicine providers. The updates in every chapter in this revision to the Core Competencies reflects the changes in the healthcare landscape and hospitalist practice environment over the past decade, and we encourage readers to revisit the entire compendium. Table 3 highlights some of the salient changes in this revision.

Hospital medicine continues to evolve as a specialty. The Core Competencies define hospitalists as agents of change and foster the development of a culture of safe and effective patient care within the hospital environment. Although the CCTF hopes that the Core Competencies will preserve their relevance over time, it recognizes the importance of their periodic reevaluation and adaptation. Additionally, SHM developed the Core Competencies primarily for physicians practicing as hospitalists. As the number of physician assistants and nurse practitioners engaged in the practice of hospital medicine increases, and hospital medicine expands into nontraditional specialties such as surgical comanagement, it may be necessary to consider the development of additional or separate Hospital Medicine Core Competencies tailored to the needs of these subsets of clinicians.

Acknowledgments

The authors and the CCTF are immensely grateful to Nick Marzano for project coordination and Abbie Young for her assistance with medical editing and chapter formatting. We extend our sincerest appreciation and gratitude to the index team of authors and editors whose efforts laid the foundation for this body of work. The initial development and this revision of the Core Competencies would not have been possible without the support and assistance of the SHM staff, the SHM Education Committee, and the scores of contributors and reviewers who participated in its creation (complete list of individuals is available in Appendix 2). We thank everyone for his or her invaluable input and effort.

Disclosures

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) provided administrative support for project coordination. SHM, or any of its representatives, had no role in the development of topic areas, refinement, or vetting of the topic list. No member of the Core Competencies Task Force or the SHM Education Committee received compensation for their participation in revising the Core Competencies. The authors report no conflicts of inte

1. The core competencies in hospital medicine: a framework for curriculum development by the society of hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2006;1 Suppl 1:2-95.

2. Dressler DD, Pistoria MJ, Budnitz TL, McKean SCW, Amin AN. Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(1):48-56.

3. Hospital Medicine News, Society of Hospital Medicine. http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/press. Accessed June 16, 2016.

4. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492.

5. Conway PH. Value-driven health care: implications for hospitals and hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(8):507-511.

6. American Board of Internal Medicine. Questions and Answers Regarding ABIM’s Maintenance of Certification in Internal Medicine with a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine Program. 2009. http://www.abim.org/news/focused-practice-hospital-medicine-questions-answers.aspx. Accessed November 11, 2016.

7. The Internal Medicine Milestone Project. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/portals/0/pdfs/milestones/internalmedicinemilestones.pdf. Accessed February 29, 2016.

8. Stucky ER, Ottolini MC, Maniscalco J. Pediatric hospital medicine core competencies: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):339-343.

9. McKean SC, Budnitz TL, Dressler DD, Amin AN, Pistoria MJ. How to use the core competencies in hospital medicine: a framework for curriculum development. J Hosp Med. 2006;1 Suppl 1:57-67.

10. Anderson LW, Krathwohl DR (eds). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Outcomes. Complete edition. New York, NY: Longman; 2001.

In 2006, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) first published The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: A Framework for Curricular Development (henceforth described as the Core Competencies) to help define the role and expectations of hospitalists.1,2 The Core Competencies provided a framework for evaluating clinical skills and professional expertise within a rapidly developing field and highlighted opportunities for growth. Since the initial development and publication of the Core Competencies, changes in the healthcare landscape and hospitalist practice environment have prompted this revision.

Over the past decade, the field of hospital medicine has experienced exponential growth. In 2005, just over 16,000 hospitalists were practicing in the United States. By 2015, that number had increased to an estimated 44,000 hospitalists, accounting for approximately 6% of the physician workforce.3 Hospitalists have expanded the scope of hospital medicine in many ways. In their roles, hospitalists lead and participate in hospital-based care models that emphasize interprofessional collaboration and a focus on the delivery of high-quality and cost-effective care across a variety of clinical domains (eg, the Choosing Wisely initiative).4 They are also engaged in patient safety and quality initiatives that are increasingly being used as benchmarks to rate hospitals and as factors for hospital payment (eg, Hospital Inpatient Value-Based Purchasing Program).5 In fact, the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) created a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine Maintenance of Certification program in response to the growing number of internists choosing to concentrate their practice in the hospital setting. This decision by the ABIM underscores the value that hospitalists bring to improving patient care in the hospital setting. The ABIM also recognizes the Core Competencies as a curricular framework for a focused practice in hospital medicine.6

Changes within the educational environment have demanded attentive and active participation by many hospitalists. For example, in 2012, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) introduced the Milestones Project, a new outcomes-based framework designed to more effectively assess learner performance across the 6 core competencies.7 These milestones assessments create intentional opportunities to guide the development of physicians during their training, including in the inpatient environments in which hospitalists practice. Where applicable, existing Core Competencies learning objectives were compared with external sources such as the individual ACGME performance milestones for this revision.

THE CORE COMPETENCIES

The Core Competencies focus on adult hospital medicine. The Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies are published separately.8 Importantly, the Core Competencies document is not intended to define an absolute set of clinical, procedural, or system-based topics described in textbooks or used by graduate medical education training programs. It does not define or limit the scope of the practice of hospital medicine. Rather, the Core Competencies serve as measurable learning objectives that encourage teaching faculty, practicing hospitalists, and administrators to develop individual skill sets and programs to improve patient care contextualized to the needs of an individual, care setting, or institution. To permit this flexibility, individual chapter-specific objectives are intentionally general in nature. Finally, the Core Competencies document is not a set of practice guidelines, nor does it offer any representation of a “standard of care.” Readers are encouraged to explore the article by McKean et al.9 to review examples of application of the Core Competencies and suggestions for curricular development.

The purpose of this article is to describe the criteria for inclusion of new chapters in the Core Competencies and the methodology of the review and revision process. It outlines the process of initial review and editing of the existing chapters; needs assessment for new topics; new chapter production; and the process of review and revision of individual chapters to create the complete document. The revised Core Competencies document is available online at http://www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com/jhospmed/issue/134981/journal-hospital-medicine-124-suppl-1.

REVIEW AND REVISION PROCESS

In 2012, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Education Committee created a Core Competencies Task Force (CCTF) in response to the SHM Board of Directors’ charge that it review and update the initial Core Competencies document. The CCTF comprised of 5 physician SHM Education Committee members and one SHM staff representative. CCTF membership included hospitalists with an interest and familiarity with the Core Competencies document. The SHM Education Committee nominated the CCTF chair, who determined the optimal size, qualifications, and composition of the task force with approval from the Committee. The CCTF communicated through frequent conference calls and via e-mail correspondence to conduct an initial review of the existing chapters and to perform a needs assessment for new topics.

Individual Chapter Review

The SHM Education Committee provided critical input and approved the chapter review process designed by the CCTF (Figure). The CCTF reviewed each chapter of the Core Competencies document to assess its continuing relevance to the field of hospital medicine with a standardized tool (Appendix 1). The process required that at least 2 CCTF members reviewed each chapter. Preliminary reviewers assessed the current relevance of each chapter, determined whether individual learning objectives required additional investigation or modification, and developed new learning objectives to fill any educational gaps. All CCTF members then discussed assimilated feedback from the initial CCTF review, using consensus decision making to determine chapter changes and modifications. The CCTF found each of the existing chapters to be relevant to the field and identified none for removal.

The CCTF rewrote all chapters. It then disseminated proposed chapter changes to a panel of diverse independent reviewers to solicit suggestions and comments to ensure a multidisciplinary and balanced review process. Independent reviewers included authors of the original Core Competencies chapters, invited content experts, and members of the SHM Education Committee. When appropriate, corresponding SHM Committees reviewed individual chapters for updates and revisions. For example, the SHM Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee reviewed the chapters on patient safety and quality improvement, and the SHM Practice Management Committee reviewed the chapter on management practices. Four CCTF section editors managed an independent portfolio of chapters. Each CCTF section editor assimilated the various draft versions, corresponded with individual reviewers when necessary, and compiled the changes into a subsequent draft. This process ensured that the final version of every chapter reflected the thoughtful input from all parties involved in the review. Throughout the process, the CCTF used consensus decision making to adjudicate chapter changes and modifications. The 2006 Core Competencies Editorial team also reviewed the revision and provided critical input. The SHM Education Committee and the SHM Board of Directors reviewed and approved the final version of the Core Competencies document.

Needs Assessment and Selection of New Core Competency Chapters

The CCTF issued a call for new topics to the members of the SHM Education Committee for inclusion in the Core Competencies. Topics were also identified from the following sources: the top 100 adult medical diagnoses at hospital discharge in the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project database in 2010; topics in hospital medicine textbooks; curricula presented at the 3 most recent SHM annual meetings; and responses from SHM annual meeting surveys. Table 1 lists the topics considered for addition.

Members of the SHM Education Committee rated each of the potential topics considered for inclusion based on the following characteristics: relevance to the field of hospital medicine; intersection of the topic with medical subspecialties; and its appropriateness as a separate, stand-alone chapter. In addition, topics more frequently encountered by hospitalists, those deemed clinically important with a known risk of complications or management inconsistencies, and those with significant opportunities for quality improvement initiatives carried more weight. Syncope and hyponatremia were the only 2 clinical conditions identified that met all of the inclusion criteria. No additional topics met the criteria for new chapter development in the Procedures or Healthcare Systems sections. The SHM Education Committee identified the use of point-of-care ultrasonography as an important advancement in the field. Where appropriate, the individual procedure chapters now include a new competency-based objective highlighting its role. In addition, a separate SHM task force is working to develop a practice guideline for the use of point-of-care ultrasonography by hospitalists.

Contributors

The SHM Education Committee determined authorship for the new chapters (syncope and hyponatremia). It assigned 2 CCTF members with content expertise and familiarity with the Core Competencies to each author one chapter. Given the limited number of new chapters, it made a decision to develop the content internally rather than through an open-call for authorship nominations to practicing SHM members. The authors made an effort to maintain consistency with the educational theory used to develop the initial Core Competencies. Each of the new topics underwent rigorous review as previously described, including additional independent reviews by hospitalists with content expertise in these areas.

CHAPTER FORMAT AND CONTENT CHANGES

Following the same format as the earlier version, the 2017 Core Competencies revision contains 53 chapters, divided into 3 sections—Clinical Conditions, Procedures, and Healthcare Systems (Table 2) —all integral components of the practice of hospital medicine. The design allows individual chapters to stand alone. However, each chapter should be considered in the context of the entire document because a particular concept may be only briefly discussed in one chapter, but described in greater depth in another given the potential overlap across topics.

The chapters maintain the same content structure as the original version. Each chapter begins with an introductory paragraph followed by a list of competency-based objectives grouped in subsections according to the educational theory of learning domains: cognitive (knowledge), psychomotor (skills), and affective (attitudes).10 In addition, a subsection for System Organization and Improvement is included in the Clinical Conditions and Procedure chapters to emphasize the importance of interprofessional collaboration for optimal patient care. These subsections were not included in the Healthcare Systems chapters, as system organization and improvement is intrinsic to these subjects.

The introductory paragraph provides background information and describes how the chapter remains relevant to the current practice of hospital medicine. Individual competency-based objectives outline a relevant concept and expected level of proficiency as defined by Bloom’s taxonomy.10 New objectives reflect changes in the healthcare landscape over the past decade or further enhance each chapter’s concepts. Chapter authors made an effort to develop chapter and learning objective concepts that are consistent with external resources such as the ACGME Milestones Project and practice guideline objectives developed by a variety of professional organizations.

SUMMARY AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The Core Competencies document serves as a resource for hospitalists and hospital medicine programs to evaluate, develop, and improve individual and collective skills and the practice environment. The Core Competencies also provide a framework for medical school clerkship directors and residency and fellowship program directors, as well as course directors of Continuing Medical Education programs, to develop curricula to enhance educational experiences for trainees and hospital medicine providers. The updates in every chapter in this revision to the Core Competencies reflects the changes in the healthcare landscape and hospitalist practice environment over the past decade, and we encourage readers to revisit the entire compendium. Table 3 highlights some of the salient changes in this revision.

Hospital medicine continues to evolve as a specialty. The Core Competencies define hospitalists as agents of change and foster the development of a culture of safe and effective patient care within the hospital environment. Although the CCTF hopes that the Core Competencies will preserve their relevance over time, it recognizes the importance of their periodic reevaluation and adaptation. Additionally, SHM developed the Core Competencies primarily for physicians practicing as hospitalists. As the number of physician assistants and nurse practitioners engaged in the practice of hospital medicine increases, and hospital medicine expands into nontraditional specialties such as surgical comanagement, it may be necessary to consider the development of additional or separate Hospital Medicine Core Competencies tailored to the needs of these subsets of clinicians.

Acknowledgments

The authors and the CCTF are immensely grateful to Nick Marzano for project coordination and Abbie Young for her assistance with medical editing and chapter formatting. We extend our sincerest appreciation and gratitude to the index team of authors and editors whose efforts laid the foundation for this body of work. The initial development and this revision of the Core Competencies would not have been possible without the support and assistance of the SHM staff, the SHM Education Committee, and the scores of contributors and reviewers who participated in its creation (complete list of individuals is available in Appendix 2). We thank everyone for his or her invaluable input and effort.

Disclosures

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) provided administrative support for project coordination. SHM, or any of its representatives, had no role in the development of topic areas, refinement, or vetting of the topic list. No member of the Core Competencies Task Force or the SHM Education Committee received compensation for their participation in revising the Core Competencies. The authors report no conflicts of inte

In 2006, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) first published The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: A Framework for Curricular Development (henceforth described as the Core Competencies) to help define the role and expectations of hospitalists.1,2 The Core Competencies provided a framework for evaluating clinical skills and professional expertise within a rapidly developing field and highlighted opportunities for growth. Since the initial development and publication of the Core Competencies, changes in the healthcare landscape and hospitalist practice environment have prompted this revision.

Over the past decade, the field of hospital medicine has experienced exponential growth. In 2005, just over 16,000 hospitalists were practicing in the United States. By 2015, that number had increased to an estimated 44,000 hospitalists, accounting for approximately 6% of the physician workforce.3 Hospitalists have expanded the scope of hospital medicine in many ways. In their roles, hospitalists lead and participate in hospital-based care models that emphasize interprofessional collaboration and a focus on the delivery of high-quality and cost-effective care across a variety of clinical domains (eg, the Choosing Wisely initiative).4 They are also engaged in patient safety and quality initiatives that are increasingly being used as benchmarks to rate hospitals and as factors for hospital payment (eg, Hospital Inpatient Value-Based Purchasing Program).5 In fact, the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) created a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine Maintenance of Certification program in response to the growing number of internists choosing to concentrate their practice in the hospital setting. This decision by the ABIM underscores the value that hospitalists bring to improving patient care in the hospital setting. The ABIM also recognizes the Core Competencies as a curricular framework for a focused practice in hospital medicine.6

Changes within the educational environment have demanded attentive and active participation by many hospitalists. For example, in 2012, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) introduced the Milestones Project, a new outcomes-based framework designed to more effectively assess learner performance across the 6 core competencies.7 These milestones assessments create intentional opportunities to guide the development of physicians during their training, including in the inpatient environments in which hospitalists practice. Where applicable, existing Core Competencies learning objectives were compared with external sources such as the individual ACGME performance milestones for this revision.

THE CORE COMPETENCIES

The Core Competencies focus on adult hospital medicine. The Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies are published separately.8 Importantly, the Core Competencies document is not intended to define an absolute set of clinical, procedural, or system-based topics described in textbooks or used by graduate medical education training programs. It does not define or limit the scope of the practice of hospital medicine. Rather, the Core Competencies serve as measurable learning objectives that encourage teaching faculty, practicing hospitalists, and administrators to develop individual skill sets and programs to improve patient care contextualized to the needs of an individual, care setting, or institution. To permit this flexibility, individual chapter-specific objectives are intentionally general in nature. Finally, the Core Competencies document is not a set of practice guidelines, nor does it offer any representation of a “standard of care.” Readers are encouraged to explore the article by McKean et al.9 to review examples of application of the Core Competencies and suggestions for curricular development.

The purpose of this article is to describe the criteria for inclusion of new chapters in the Core Competencies and the methodology of the review and revision process. It outlines the process of initial review and editing of the existing chapters; needs assessment for new topics; new chapter production; and the process of review and revision of individual chapters to create the complete document. The revised Core Competencies document is available online at http://www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com/jhospmed/issue/134981/journal-hospital-medicine-124-suppl-1.

REVIEW AND REVISION PROCESS

In 2012, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Education Committee created a Core Competencies Task Force (CCTF) in response to the SHM Board of Directors’ charge that it review and update the initial Core Competencies document. The CCTF comprised of 5 physician SHM Education Committee members and one SHM staff representative. CCTF membership included hospitalists with an interest and familiarity with the Core Competencies document. The SHM Education Committee nominated the CCTF chair, who determined the optimal size, qualifications, and composition of the task force with approval from the Committee. The CCTF communicated through frequent conference calls and via e-mail correspondence to conduct an initial review of the existing chapters and to perform a needs assessment for new topics.

Individual Chapter Review

The SHM Education Committee provided critical input and approved the chapter review process designed by the CCTF (Figure). The CCTF reviewed each chapter of the Core Competencies document to assess its continuing relevance to the field of hospital medicine with a standardized tool (Appendix 1). The process required that at least 2 CCTF members reviewed each chapter. Preliminary reviewers assessed the current relevance of each chapter, determined whether individual learning objectives required additional investigation or modification, and developed new learning objectives to fill any educational gaps. All CCTF members then discussed assimilated feedback from the initial CCTF review, using consensus decision making to determine chapter changes and modifications. The CCTF found each of the existing chapters to be relevant to the field and identified none for removal.

The CCTF rewrote all chapters. It then disseminated proposed chapter changes to a panel of diverse independent reviewers to solicit suggestions and comments to ensure a multidisciplinary and balanced review process. Independent reviewers included authors of the original Core Competencies chapters, invited content experts, and members of the SHM Education Committee. When appropriate, corresponding SHM Committees reviewed individual chapters for updates and revisions. For example, the SHM Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee reviewed the chapters on patient safety and quality improvement, and the SHM Practice Management Committee reviewed the chapter on management practices. Four CCTF section editors managed an independent portfolio of chapters. Each CCTF section editor assimilated the various draft versions, corresponded with individual reviewers when necessary, and compiled the changes into a subsequent draft. This process ensured that the final version of every chapter reflected the thoughtful input from all parties involved in the review. Throughout the process, the CCTF used consensus decision making to adjudicate chapter changes and modifications. The 2006 Core Competencies Editorial team also reviewed the revision and provided critical input. The SHM Education Committee and the SHM Board of Directors reviewed and approved the final version of the Core Competencies document.

Needs Assessment and Selection of New Core Competency Chapters

The CCTF issued a call for new topics to the members of the SHM Education Committee for inclusion in the Core Competencies. Topics were also identified from the following sources: the top 100 adult medical diagnoses at hospital discharge in the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project database in 2010; topics in hospital medicine textbooks; curricula presented at the 3 most recent SHM annual meetings; and responses from SHM annual meeting surveys. Table 1 lists the topics considered for addition.

Members of the SHM Education Committee rated each of the potential topics considered for inclusion based on the following characteristics: relevance to the field of hospital medicine; intersection of the topic with medical subspecialties; and its appropriateness as a separate, stand-alone chapter. In addition, topics more frequently encountered by hospitalists, those deemed clinically important with a known risk of complications or management inconsistencies, and those with significant opportunities for quality improvement initiatives carried more weight. Syncope and hyponatremia were the only 2 clinical conditions identified that met all of the inclusion criteria. No additional topics met the criteria for new chapter development in the Procedures or Healthcare Systems sections. The SHM Education Committee identified the use of point-of-care ultrasonography as an important advancement in the field. Where appropriate, the individual procedure chapters now include a new competency-based objective highlighting its role. In addition, a separate SHM task force is working to develop a practice guideline for the use of point-of-care ultrasonography by hospitalists.

Contributors

The SHM Education Committee determined authorship for the new chapters (syncope and hyponatremia). It assigned 2 CCTF members with content expertise and familiarity with the Core Competencies to each author one chapter. Given the limited number of new chapters, it made a decision to develop the content internally rather than through an open-call for authorship nominations to practicing SHM members. The authors made an effort to maintain consistency with the educational theory used to develop the initial Core Competencies. Each of the new topics underwent rigorous review as previously described, including additional independent reviews by hospitalists with content expertise in these areas.

CHAPTER FORMAT AND CONTENT CHANGES

Following the same format as the earlier version, the 2017 Core Competencies revision contains 53 chapters, divided into 3 sections—Clinical Conditions, Procedures, and Healthcare Systems (Table 2) —all integral components of the practice of hospital medicine. The design allows individual chapters to stand alone. However, each chapter should be considered in the context of the entire document because a particular concept may be only briefly discussed in one chapter, but described in greater depth in another given the potential overlap across topics.

The chapters maintain the same content structure as the original version. Each chapter begins with an introductory paragraph followed by a list of competency-based objectives grouped in subsections according to the educational theory of learning domains: cognitive (knowledge), psychomotor (skills), and affective (attitudes).10 In addition, a subsection for System Organization and Improvement is included in the Clinical Conditions and Procedure chapters to emphasize the importance of interprofessional collaboration for optimal patient care. These subsections were not included in the Healthcare Systems chapters, as system organization and improvement is intrinsic to these subjects.

The introductory paragraph provides background information and describes how the chapter remains relevant to the current practice of hospital medicine. Individual competency-based objectives outline a relevant concept and expected level of proficiency as defined by Bloom’s taxonomy.10 New objectives reflect changes in the healthcare landscape over the past decade or further enhance each chapter’s concepts. Chapter authors made an effort to develop chapter and learning objective concepts that are consistent with external resources such as the ACGME Milestones Project and practice guideline objectives developed by a variety of professional organizations.

SUMMARY AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The Core Competencies document serves as a resource for hospitalists and hospital medicine programs to evaluate, develop, and improve individual and collective skills and the practice environment. The Core Competencies also provide a framework for medical school clerkship directors and residency and fellowship program directors, as well as course directors of Continuing Medical Education programs, to develop curricula to enhance educational experiences for trainees and hospital medicine providers. The updates in every chapter in this revision to the Core Competencies reflects the changes in the healthcare landscape and hospitalist practice environment over the past decade, and we encourage readers to revisit the entire compendium. Table 3 highlights some of the salient changes in this revision.

Hospital medicine continues to evolve as a specialty. The Core Competencies define hospitalists as agents of change and foster the development of a culture of safe and effective patient care within the hospital environment. Although the CCTF hopes that the Core Competencies will preserve their relevance over time, it recognizes the importance of their periodic reevaluation and adaptation. Additionally, SHM developed the Core Competencies primarily for physicians practicing as hospitalists. As the number of physician assistants and nurse practitioners engaged in the practice of hospital medicine increases, and hospital medicine expands into nontraditional specialties such as surgical comanagement, it may be necessary to consider the development of additional or separate Hospital Medicine Core Competencies tailored to the needs of these subsets of clinicians.

Acknowledgments

The authors and the CCTF are immensely grateful to Nick Marzano for project coordination and Abbie Young for her assistance with medical editing and chapter formatting. We extend our sincerest appreciation and gratitude to the index team of authors and editors whose efforts laid the foundation for this body of work. The initial development and this revision of the Core Competencies would not have been possible without the support and assistance of the SHM staff, the SHM Education Committee, and the scores of contributors and reviewers who participated in its creation (complete list of individuals is available in Appendix 2). We thank everyone for his or her invaluable input and effort.

Disclosures

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) provided administrative support for project coordination. SHM, or any of its representatives, had no role in the development of topic areas, refinement, or vetting of the topic list. No member of the Core Competencies Task Force or the SHM Education Committee received compensation for their participation in revising the Core Competencies. The authors report no conflicts of inte

1. The core competencies in hospital medicine: a framework for curriculum development by the society of hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2006;1 Suppl 1:2-95.

2. Dressler DD, Pistoria MJ, Budnitz TL, McKean SCW, Amin AN. Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(1):48-56.

3. Hospital Medicine News, Society of Hospital Medicine. http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/press. Accessed June 16, 2016.

4. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492.

5. Conway PH. Value-driven health care: implications for hospitals and hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(8):507-511.

6. American Board of Internal Medicine. Questions and Answers Regarding ABIM’s Maintenance of Certification in Internal Medicine with a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine Program. 2009. http://www.abim.org/news/focused-practice-hospital-medicine-questions-answers.aspx. Accessed November 11, 2016.

7. The Internal Medicine Milestone Project. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/portals/0/pdfs/milestones/internalmedicinemilestones.pdf. Accessed February 29, 2016.

8. Stucky ER, Ottolini MC, Maniscalco J. Pediatric hospital medicine core competencies: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):339-343.

9. McKean SC, Budnitz TL, Dressler DD, Amin AN, Pistoria MJ. How to use the core competencies in hospital medicine: a framework for curriculum development. J Hosp Med. 2006;1 Suppl 1:57-67.

10. Anderson LW, Krathwohl DR (eds). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Outcomes. Complete edition. New York, NY: Longman; 2001.

1. The core competencies in hospital medicine: a framework for curriculum development by the society of hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2006;1 Suppl 1:2-95.

2. Dressler DD, Pistoria MJ, Budnitz TL, McKean SCW, Amin AN. Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(1):48-56.

3. Hospital Medicine News, Society of Hospital Medicine. http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/press. Accessed June 16, 2016.

4. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492.

5. Conway PH. Value-driven health care: implications for hospitals and hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(8):507-511.

6. American Board of Internal Medicine. Questions and Answers Regarding ABIM’s Maintenance of Certification in Internal Medicine with a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine Program. 2009. http://www.abim.org/news/focused-practice-hospital-medicine-questions-answers.aspx. Accessed November 11, 2016.

7. The Internal Medicine Milestone Project. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/portals/0/pdfs/milestones/internalmedicinemilestones.pdf. Accessed February 29, 2016.

8. Stucky ER, Ottolini MC, Maniscalco J. Pediatric hospital medicine core competencies: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):339-343.

9. McKean SC, Budnitz TL, Dressler DD, Amin AN, Pistoria MJ. How to use the core competencies in hospital medicine: a framework for curriculum development. J Hosp Med. 2006;1 Suppl 1:57-67.

10. Anderson LW, Krathwohl DR (eds). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Outcomes. Complete edition. New York, NY: Longman; 2001.

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

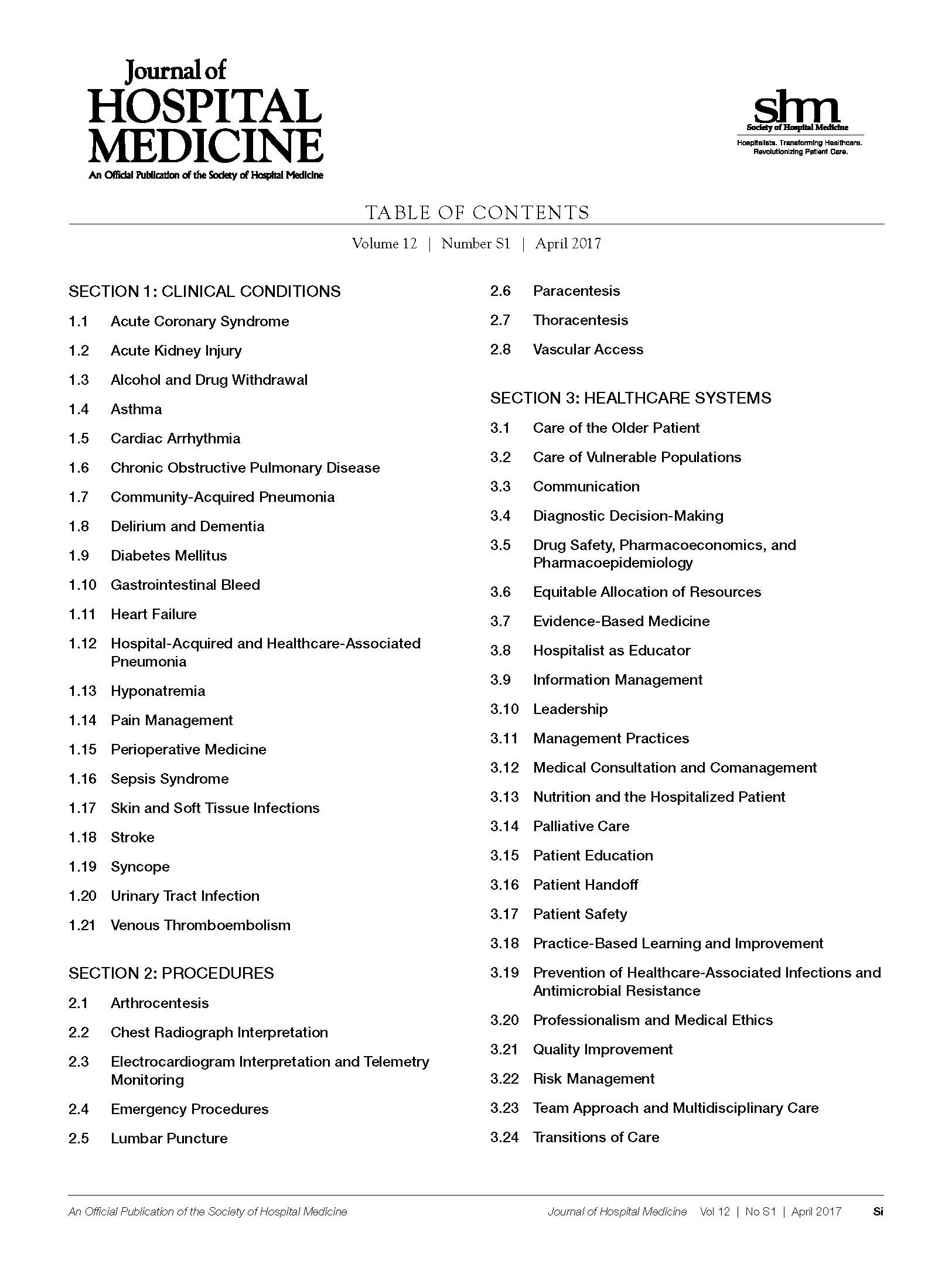

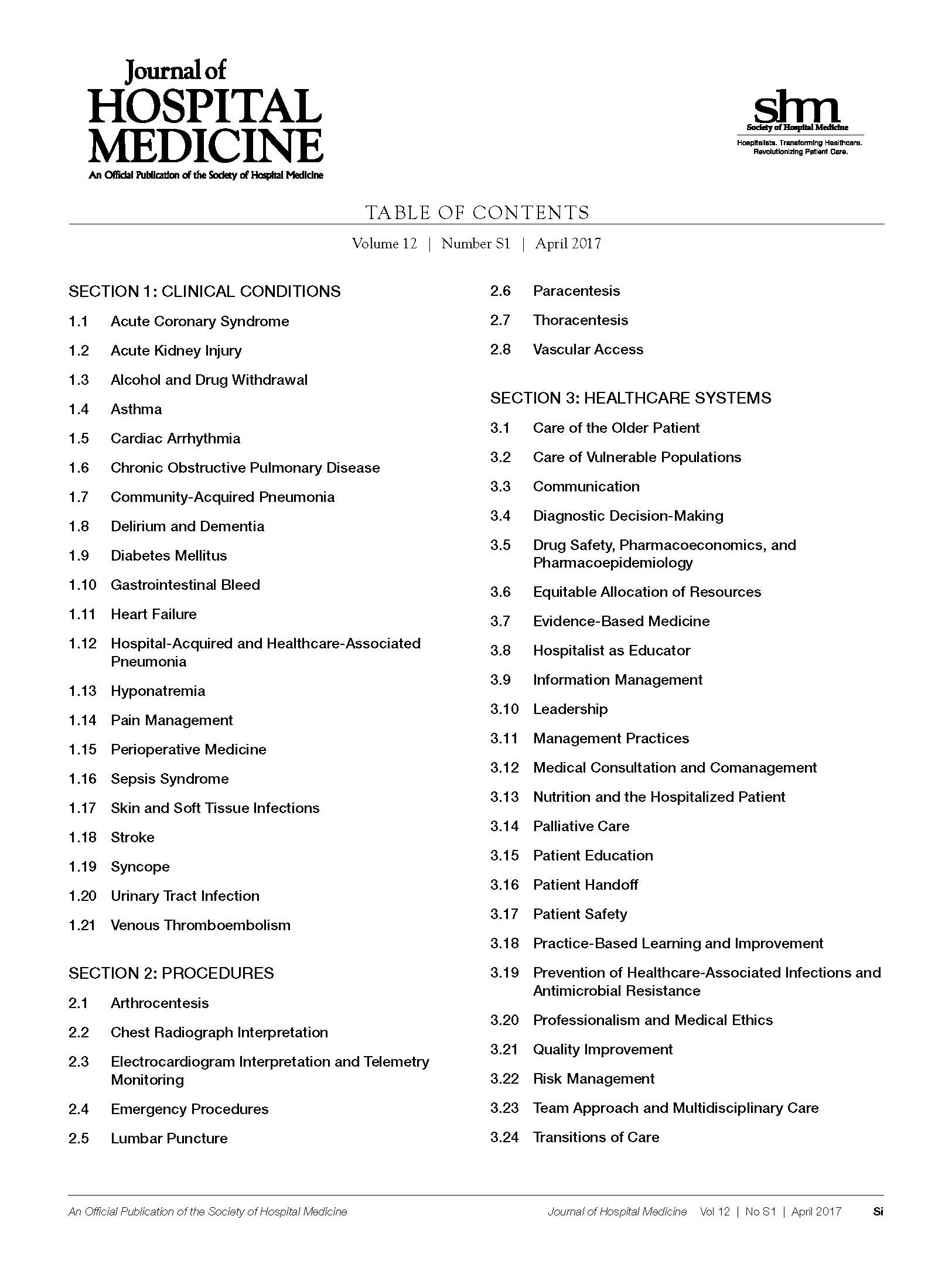

The 2017 JHM Core Competencies Table of Contents.

Want all 52 JHM Core Competency articles in an easy-to-read compendium? Order your copy now from Amazon.com.

Want all 52 JHM Core Competency articles in an easy-to-read compendium? Order your copy now from Amazon.com.

Want all 52 JHM Core Competency articles in an easy-to-read compendium? Order your copy now from Amazon.com.

Acute Kidney Injury. 2017 Hospital Medicine Revised Core Competencies

Acute kidney injury (AKI), also known as acute renal failure (ARF), is a decline in renal function over a period of hours or days that results in the accumulation of nitrogenous waste products and an impaired ability to maintain fluid/electrolyte/acid-base homeostasis. Epidemiologic studies of AKI are confounded by inconsistent definitions and underreporting. The average incidence is estimated to be 23.8 cases per 1000 hospital discharges.1Approximately 5% to 20% of critically ill patients experience AKI during the course of their illness.2 AKI may present in isolation, develop as a complication of other comorbid illness, or result as a deleterious adverse effect of treatment or diagnostic interventions. Uncomplicated AKI is associated with a mortality rate of up to 10%.3-6 Patients with AKI and multiorgan failure have mortality rates higher than 50%.3-6 AKI is associated with an increased length of hospital stay; a rise in serum creatinine of 0.5 mg/dL or greater while hospitalized confers a 3.5-day increase in length of stay.7 Hospitalists facilitate the expeditious evaluation and management of AKI to improve patient outcomes, optimize resource use, and reduce length of stay. Hospitalists can also advocate and initiate preventive strategies to reduce the incidence of secondary AKI.

KNOWLEDGE

Hospitalists should be able to:

Describe the symptoms and signs of AKI.

Describe and differentiate pathophysiologic causes of AKI including prerenal, intrinsic renal, and postrenal processes.

Differentiate among the causes of prerenal, intrinsic renal, and postrenal types of AKI.

Describe a logical sequence of indicated tests required to evaluate etiologies of AKI based on classification of AKI type.

List common potentially nephrotoxic agents that can cause or worsen AKI.

Explain the indications, contraindications, and mechanisms of action of the interventions used to treat AKI.

Explain the indications, contraindications, benefits, and risks of acute hemodialysis.

Recognize indications for specialty consultation for AKI and the role of nephrology and/or urology specialists.

Describe criteria, including specific measures of clinical stability, that must be met before discharging patients with AKI.

Explain the specific goals that should be met to ensure safe transitions of care for patients with AKI.

SKILLS

Hospitalists should be able to:

Assess patients with suspected AKI in a timely manner and manage or comanage the patient with the primary requesting service.

Elicit a thorough and relevant medical history with emphasis on factors predisposing or contributing to the development of AKI.

Review all drug use including prescription and over-the-counter medications, herbal remedies, nutritional supplements, and illicit drugs to identify common potential nephrotoxins.

Perform a physical examination to assess volume status and to identify underlying comorbid states that may predispose to the development of AKI.

Order and interpret results of indicated diagnostic studies that may include urinalysis and microscopic sediment analysis, urinary diagnostic indices, urinary protein excretion, serologic evaluation, and renal imaging.

Interpret common clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings used to evaluate and follow the severity of AKI.

Diagnose common complications, such as electrolyte abnormalities, that occur with AKI and institute corrective measures.

Calculate estimated creatinine clearance for medication dosage adjustments when indicated.

Identify patients at risk for developing AKI and institute appropriate preventive measures including avoidance of unnecessary radiographic contrast exposure and adherence to evidence-based interventions to reduce the risk of contrast-induced nephropathy.

Coordinate appropriate nutritional and metabolic interventions.

Formulate an AKI treatment plan tailored to the individual patient, which may include fluid management, pharmacologic agents, nutritional recommendations, and patient education.

Identify and treat factors that may complicate the management of AKI, including extreme blood pressure, underlying infections, and the sequelae of electrolyte abnormalities.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the cause and prognosis of AKI.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the rationale for the use of radiographic tests and procedures and the benefit and potential adverse effects of radiographic contrast agents.

Facilitate discharge planning early during hospitalization.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the goals of care, discharge instructions, and management after hospital discharge to ensure safe follow-up and transitions of care.

Document the treatment plan and provide clear discharge instructions for postdischarge clinicians.

ATTITUDES

Hospitalists should be able to:

Employ a multidisciplinary approach, which may include nursing, nutrition, and pharmacy services, in the care of patients with AKI that begins at admission and continues through all care transitions.

Follow evidence-based recommendations, protocols, and risk-stratification tools for the treatment of AKI.

SYSTEM ORGANIZATION AND IMPROVEMENT

To improve efficiency and quality within their organizations, hospitalists should:

Advocate for, establish, and support initiatives to reduce the incidence of iatrogenic AKI.

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in multidisciplinary teams (including nephrology, nursing, pharmacy, and nutrition services) to improve processes that facilitate early identification of AKI and improved patient outcomes.

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in multidisciplinary initiatives to promote patient safety and optimize management strategies for AKI.

1. Xue JL, Daniels F, Star RA, Kimmel PL, Eggers PW, Molitoris BA, et al. Incidence and mortality of acute renal failure in Medicare beneficiaries, 1992-2001. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(4):1135-1142.

2. Metnitz PG, Krenn CG, Steltzer H, Lang T, Ploder J, Lenz K, et al. Effect of acute renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy on outcome in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(9):2051-2058.

3. Cosentino F, Chaff C, Piedmonte M. Risk factors influencing survival in ICU acute renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1994;9(Suppl 4):179-182.

4. Hou SH, Bushinsky DA, Wish JB, Cohen JJ, Harrington JT. Hospital-acquired renal insufficiency: a prospective study. Am H Med. 1983;74(2):243-248.

5. Liano F, Junco E, Pascual J, Madero R, Verde E. The spectrum of acute renal failure in the intensive care unit compared with that seen in other settings. The Madrid Acute Renal Failure Study Group. Kidney Int Suppl. 1998;66:S16-S24.

6. Shusterman N, Strom BL, Murray TG, Morrison G, West SL, Maislin G. Risk factors and outcome of hospital-acquired acute renal failure. Clinical epidemiologic study. Am J Med. 1987;83(1):65-71.

7. Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, Bonventre JV, Bates DW. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(11):3365-3370.

Acute kidney injury (AKI), also known as acute renal failure (ARF), is a decline in renal function over a period of hours or days that results in the accumulation of nitrogenous waste products and an impaired ability to maintain fluid/electrolyte/acid-base homeostasis. Epidemiologic studies of AKI are confounded by inconsistent definitions and underreporting. The average incidence is estimated to be 23.8 cases per 1000 hospital discharges.1Approximately 5% to 20% of critically ill patients experience AKI during the course of their illness.2 AKI may present in isolation, develop as a complication of other comorbid illness, or result as a deleterious adverse effect of treatment or diagnostic interventions. Uncomplicated AKI is associated with a mortality rate of up to 10%.3-6 Patients with AKI and multiorgan failure have mortality rates higher than 50%.3-6 AKI is associated with an increased length of hospital stay; a rise in serum creatinine of 0.5 mg/dL or greater while hospitalized confers a 3.5-day increase in length of stay.7 Hospitalists facilitate the expeditious evaluation and management of AKI to improve patient outcomes, optimize resource use, and reduce length of stay. Hospitalists can also advocate and initiate preventive strategies to reduce the incidence of secondary AKI.

KNOWLEDGE

Hospitalists should be able to:

Describe the symptoms and signs of AKI.

Describe and differentiate pathophysiologic causes of AKI including prerenal, intrinsic renal, and postrenal processes.

Differentiate among the causes of prerenal, intrinsic renal, and postrenal types of AKI.

Describe a logical sequence of indicated tests required to evaluate etiologies of AKI based on classification of AKI type.

List common potentially nephrotoxic agents that can cause or worsen AKI.

Explain the indications, contraindications, and mechanisms of action of the interventions used to treat AKI.

Explain the indications, contraindications, benefits, and risks of acute hemodialysis.

Recognize indications for specialty consultation for AKI and the role of nephrology and/or urology specialists.

Describe criteria, including specific measures of clinical stability, that must be met before discharging patients with AKI.

Explain the specific goals that should be met to ensure safe transitions of care for patients with AKI.

SKILLS

Hospitalists should be able to:

Assess patients with suspected AKI in a timely manner and manage or comanage the patient with the primary requesting service.

Elicit a thorough and relevant medical history with emphasis on factors predisposing or contributing to the development of AKI.

Review all drug use including prescription and over-the-counter medications, herbal remedies, nutritional supplements, and illicit drugs to identify common potential nephrotoxins.

Perform a physical examination to assess volume status and to identify underlying comorbid states that may predispose to the development of AKI.

Order and interpret results of indicated diagnostic studies that may include urinalysis and microscopic sediment analysis, urinary diagnostic indices, urinary protein excretion, serologic evaluation, and renal imaging.

Interpret common clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings used to evaluate and follow the severity of AKI.

Diagnose common complications, such as electrolyte abnormalities, that occur with AKI and institute corrective measures.

Calculate estimated creatinine clearance for medication dosage adjustments when indicated.

Identify patients at risk for developing AKI and institute appropriate preventive measures including avoidance of unnecessary radiographic contrast exposure and adherence to evidence-based interventions to reduce the risk of contrast-induced nephropathy.

Coordinate appropriate nutritional and metabolic interventions.

Formulate an AKI treatment plan tailored to the individual patient, which may include fluid management, pharmacologic agents, nutritional recommendations, and patient education.

Identify and treat factors that may complicate the management of AKI, including extreme blood pressure, underlying infections, and the sequelae of electrolyte abnormalities.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the cause and prognosis of AKI.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the rationale for the use of radiographic tests and procedures and the benefit and potential adverse effects of radiographic contrast agents.

Facilitate discharge planning early during hospitalization.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the goals of care, discharge instructions, and management after hospital discharge to ensure safe follow-up and transitions of care.

Document the treatment plan and provide clear discharge instructions for postdischarge clinicians.

ATTITUDES

Hospitalists should be able to:

Employ a multidisciplinary approach, which may include nursing, nutrition, and pharmacy services, in the care of patients with AKI that begins at admission and continues through all care transitions.

Follow evidence-based recommendations, protocols, and risk-stratification tools for the treatment of AKI.

SYSTEM ORGANIZATION AND IMPROVEMENT

To improve efficiency and quality within their organizations, hospitalists should:

Advocate for, establish, and support initiatives to reduce the incidence of iatrogenic AKI.

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in multidisciplinary teams (including nephrology, nursing, pharmacy, and nutrition services) to improve processes that facilitate early identification of AKI and improved patient outcomes.

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in multidisciplinary initiatives to promote patient safety and optimize management strategies for AKI.

Acute kidney injury (AKI), also known as acute renal failure (ARF), is a decline in renal function over a period of hours or days that results in the accumulation of nitrogenous waste products and an impaired ability to maintain fluid/electrolyte/acid-base homeostasis. Epidemiologic studies of AKI are confounded by inconsistent definitions and underreporting. The average incidence is estimated to be 23.8 cases per 1000 hospital discharges.1Approximately 5% to 20% of critically ill patients experience AKI during the course of their illness.2 AKI may present in isolation, develop as a complication of other comorbid illness, or result as a deleterious adverse effect of treatment or diagnostic interventions. Uncomplicated AKI is associated with a mortality rate of up to 10%.3-6 Patients with AKI and multiorgan failure have mortality rates higher than 50%.3-6 AKI is associated with an increased length of hospital stay; a rise in serum creatinine of 0.5 mg/dL or greater while hospitalized confers a 3.5-day increase in length of stay.7 Hospitalists facilitate the expeditious evaluation and management of AKI to improve patient outcomes, optimize resource use, and reduce length of stay. Hospitalists can also advocate and initiate preventive strategies to reduce the incidence of secondary AKI.

KNOWLEDGE

Hospitalists should be able to:

Describe the symptoms and signs of AKI.

Describe and differentiate pathophysiologic causes of AKI including prerenal, intrinsic renal, and postrenal processes.

Differentiate among the causes of prerenal, intrinsic renal, and postrenal types of AKI.

Describe a logical sequence of indicated tests required to evaluate etiologies of AKI based on classification of AKI type.

List common potentially nephrotoxic agents that can cause or worsen AKI.

Explain the indications, contraindications, and mechanisms of action of the interventions used to treat AKI.

Explain the indications, contraindications, benefits, and risks of acute hemodialysis.

Recognize indications for specialty consultation for AKI and the role of nephrology and/or urology specialists.

Describe criteria, including specific measures of clinical stability, that must be met before discharging patients with AKI.

Explain the specific goals that should be met to ensure safe transitions of care for patients with AKI.

SKILLS

Hospitalists should be able to:

Assess patients with suspected AKI in a timely manner and manage or comanage the patient with the primary requesting service.

Elicit a thorough and relevant medical history with emphasis on factors predisposing or contributing to the development of AKI.

Review all drug use including prescription and over-the-counter medications, herbal remedies, nutritional supplements, and illicit drugs to identify common potential nephrotoxins.

Perform a physical examination to assess volume status and to identify underlying comorbid states that may predispose to the development of AKI.

Order and interpret results of indicated diagnostic studies that may include urinalysis and microscopic sediment analysis, urinary diagnostic indices, urinary protein excretion, serologic evaluation, and renal imaging.

Interpret common clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings used to evaluate and follow the severity of AKI.

Diagnose common complications, such as electrolyte abnormalities, that occur with AKI and institute corrective measures.

Calculate estimated creatinine clearance for medication dosage adjustments when indicated.

Identify patients at risk for developing AKI and institute appropriate preventive measures including avoidance of unnecessary radiographic contrast exposure and adherence to evidence-based interventions to reduce the risk of contrast-induced nephropathy.

Coordinate appropriate nutritional and metabolic interventions.

Formulate an AKI treatment plan tailored to the individual patient, which may include fluid management, pharmacologic agents, nutritional recommendations, and patient education.

Identify and treat factors that may complicate the management of AKI, including extreme blood pressure, underlying infections, and the sequelae of electrolyte abnormalities.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the cause and prognosis of AKI.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the rationale for the use of radiographic tests and procedures and the benefit and potential adverse effects of radiographic contrast agents.

Facilitate discharge planning early during hospitalization.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the goals of care, discharge instructions, and management after hospital discharge to ensure safe follow-up and transitions of care.

Document the treatment plan and provide clear discharge instructions for postdischarge clinicians.

ATTITUDES

Hospitalists should be able to:

Employ a multidisciplinary approach, which may include nursing, nutrition, and pharmacy services, in the care of patients with AKI that begins at admission and continues through all care transitions.

Follow evidence-based recommendations, protocols, and risk-stratification tools for the treatment of AKI.

SYSTEM ORGANIZATION AND IMPROVEMENT

To improve efficiency and quality within their organizations, hospitalists should:

Advocate for, establish, and support initiatives to reduce the incidence of iatrogenic AKI.

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in multidisciplinary teams (including nephrology, nursing, pharmacy, and nutrition services) to improve processes that facilitate early identification of AKI and improved patient outcomes.

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in multidisciplinary initiatives to promote patient safety and optimize management strategies for AKI.

1. Xue JL, Daniels F, Star RA, Kimmel PL, Eggers PW, Molitoris BA, et al. Incidence and mortality of acute renal failure in Medicare beneficiaries, 1992-2001. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(4):1135-1142.

2. Metnitz PG, Krenn CG, Steltzer H, Lang T, Ploder J, Lenz K, et al. Effect of acute renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy on outcome in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(9):2051-2058.

3. Cosentino F, Chaff C, Piedmonte M. Risk factors influencing survival in ICU acute renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1994;9(Suppl 4):179-182.

4. Hou SH, Bushinsky DA, Wish JB, Cohen JJ, Harrington JT. Hospital-acquired renal insufficiency: a prospective study. Am H Med. 1983;74(2):243-248.