User login

As Girl Grows, Lesions Follow Suit

ANSWER

The correct diagnosis in this case is juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG; choice “d”).

Anderson-Fabry disease (choice “a”) is a rare inherited disorder characterized by widespread red papules; these lesions, however, are much smaller and far more widespread than those of JXG.

Considered a possibility at initial presentation, molluscum contagiosum (choice “b”) was quickly ruled out upon further inspection. This patient’s condition lacked the typical features of molluscum: umbilicated, white, firm papules caused by a pox virus.

Eruptive xanthomata (choice “c”) is a collection of lipid-laden macrophages caused by hypertriglyceridemia. They present as papules and nodules under, rather than on, the skin.

DISCUSSION

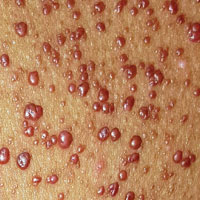

Solitary JXG lesions are fairly common, developing on the trunk, face, or extremities as smooth, reddish brown to cream papules. Typically, they cause no problems—but when multiple lesions manifest at birth, the condition can affect the eye (especially the iris, as in this case).

JXG is considered a form of histiocytosis, specifically classified as a type II non-Langerhans cell-mediated lesion. It is believed to result from a disordered macrophage response to a nonspecific tissue injury, which leads to a distinct variety of granulomatous change. These lesions are part of a spectrum of related conditions that also includes Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

No perfect treatment exists for this patient’s multitudinous skin lesions, because her darker skin could easily be permanently changed by burning, freezing, laser, or other destructive modality. Fair or not, in many cases, insurance coverage (or lack thereof) ultimately dictates what treatment is used.

Once the biopsy confirmed the diagnosis and effectively ruled out the other items in the differential, she was referred to ophthalmology for ongoing care of her eyes. Beyond that, she’ll need an annual physical with labs, because JXG is known to affect internal organs as well.

ANSWER

The correct diagnosis in this case is juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG; choice “d”).

Anderson-Fabry disease (choice “a”) is a rare inherited disorder characterized by widespread red papules; these lesions, however, are much smaller and far more widespread than those of JXG.

Considered a possibility at initial presentation, molluscum contagiosum (choice “b”) was quickly ruled out upon further inspection. This patient’s condition lacked the typical features of molluscum: umbilicated, white, firm papules caused by a pox virus.

Eruptive xanthomata (choice “c”) is a collection of lipid-laden macrophages caused by hypertriglyceridemia. They present as papules and nodules under, rather than on, the skin.

DISCUSSION

Solitary JXG lesions are fairly common, developing on the trunk, face, or extremities as smooth, reddish brown to cream papules. Typically, they cause no problems—but when multiple lesions manifest at birth, the condition can affect the eye (especially the iris, as in this case).

JXG is considered a form of histiocytosis, specifically classified as a type II non-Langerhans cell-mediated lesion. It is believed to result from a disordered macrophage response to a nonspecific tissue injury, which leads to a distinct variety of granulomatous change. These lesions are part of a spectrum of related conditions that also includes Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

No perfect treatment exists for this patient’s multitudinous skin lesions, because her darker skin could easily be permanently changed by burning, freezing, laser, or other destructive modality. Fair or not, in many cases, insurance coverage (or lack thereof) ultimately dictates what treatment is used.

Once the biopsy confirmed the diagnosis and effectively ruled out the other items in the differential, she was referred to ophthalmology for ongoing care of her eyes. Beyond that, she’ll need an annual physical with labs, because JXG is known to affect internal organs as well.

ANSWER

The correct diagnosis in this case is juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG; choice “d”).

Anderson-Fabry disease (choice “a”) is a rare inherited disorder characterized by widespread red papules; these lesions, however, are much smaller and far more widespread than those of JXG.

Considered a possibility at initial presentation, molluscum contagiosum (choice “b”) was quickly ruled out upon further inspection. This patient’s condition lacked the typical features of molluscum: umbilicated, white, firm papules caused by a pox virus.

Eruptive xanthomata (choice “c”) is a collection of lipid-laden macrophages caused by hypertriglyceridemia. They present as papules and nodules under, rather than on, the skin.

DISCUSSION

Solitary JXG lesions are fairly common, developing on the trunk, face, or extremities as smooth, reddish brown to cream papules. Typically, they cause no problems—but when multiple lesions manifest at birth, the condition can affect the eye (especially the iris, as in this case).

JXG is considered a form of histiocytosis, specifically classified as a type II non-Langerhans cell-mediated lesion. It is believed to result from a disordered macrophage response to a nonspecific tissue injury, which leads to a distinct variety of granulomatous change. These lesions are part of a spectrum of related conditions that also includes Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

No perfect treatment exists for this patient’s multitudinous skin lesions, because her darker skin could easily be permanently changed by burning, freezing, laser, or other destructive modality. Fair or not, in many cases, insurance coverage (or lack thereof) ultimately dictates what treatment is used.

Once the biopsy confirmed the diagnosis and effectively ruled out the other items in the differential, she was referred to ophthalmology for ongoing care of her eyes. Beyond that, she’ll need an annual physical with labs, because JXG is known to affect internal organs as well.

Since shortly after birth, a now 12-year-old African-American girl has had lesions on her trunk. She has never been given a diagnosis and has always been told she would “outgrow the problem.” Instead, the number and distribution of lesions continues to increase, and her pediatrician finally refers her to dermatology for evaluation.

About 150 to 200 nearly identical lesions scatter around the patient’s body, clustered mostly on the left upper back but also on the abdomen and bilateral upper thighs. The fleshy, reddish brown, mushroom-like papules range in size from 2 to 4 mm and exhibit no central umbilication. Two brown spots (each measuring 2 mm) are seen in the iris of the patient’s left eye.

There are no other apparent medical problems to report and no visual deficits. Aside from being unsightly, the lesions are asymptomatic. A shave biopsy of one of them is performed.

A Creepy Crawly Anomaly

ANSWER

The correct answer is dermatofibroma (choice “c”), based on the classic histologic picture and the lack of supportive findings for other items in the differential. These include seborrheic keratosis, granular cell tumor, basal cell carcinoma, and sweat duct cancer.

DISCUSSION

This is a perfect example of one of the most common benign tumors, seen daily in dermatology offices worldwide. Alternately referred to as superficial benign fibrous histiocytomas, dermatofibromas (DFs) typically manifest on lower extremities, are about twice as common in women as in men, and usually affect patients in their early 40s.

DFs appear most commonly as low, firm, round to ovoid, pinkish brown papules that dimple with lateral digital pressure. Though not pathognomic, the “dimple sign” is highly suggestive of this diagnosis. DF lesions can also manifest as firm, convex papules or nodules (as in this case) with the same coloring but without the dimple sign.

For years, DFs were believed to be a reaction to trauma (eg, bug bite). While this theory still has its adherents, more recent studies suggest these are true tumors composed of skin fibroblasts. Their ability to occur internally, even in bone, provides further evidence against their putatively reactive nature.

Histologically, the typical DF shows whorling fascicles of a fibroblastic spindle cell proliferation in the dermis. By contrast, the most dangerous item in the differential, the rare but greatly feared malignant dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, is characterized by a storiform (cartwheel-shaped) pattern of spindle cells.

DFs are often subject to trauma from shaving and therefore surgically removed. However, since this was not the case for this patient, she chose to leave her lesion in place.

ANSWER

The correct answer is dermatofibroma (choice “c”), based on the classic histologic picture and the lack of supportive findings for other items in the differential. These include seborrheic keratosis, granular cell tumor, basal cell carcinoma, and sweat duct cancer.

DISCUSSION

This is a perfect example of one of the most common benign tumors, seen daily in dermatology offices worldwide. Alternately referred to as superficial benign fibrous histiocytomas, dermatofibromas (DFs) typically manifest on lower extremities, are about twice as common in women as in men, and usually affect patients in their early 40s.

DFs appear most commonly as low, firm, round to ovoid, pinkish brown papules that dimple with lateral digital pressure. Though not pathognomic, the “dimple sign” is highly suggestive of this diagnosis. DF lesions can also manifest as firm, convex papules or nodules (as in this case) with the same coloring but without the dimple sign.

For years, DFs were believed to be a reaction to trauma (eg, bug bite). While this theory still has its adherents, more recent studies suggest these are true tumors composed of skin fibroblasts. Their ability to occur internally, even in bone, provides further evidence against their putatively reactive nature.

Histologically, the typical DF shows whorling fascicles of a fibroblastic spindle cell proliferation in the dermis. By contrast, the most dangerous item in the differential, the rare but greatly feared malignant dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, is characterized by a storiform (cartwheel-shaped) pattern of spindle cells.

DFs are often subject to trauma from shaving and therefore surgically removed. However, since this was not the case for this patient, she chose to leave her lesion in place.

ANSWER

The correct answer is dermatofibroma (choice “c”), based on the classic histologic picture and the lack of supportive findings for other items in the differential. These include seborrheic keratosis, granular cell tumor, basal cell carcinoma, and sweat duct cancer.

DISCUSSION

This is a perfect example of one of the most common benign tumors, seen daily in dermatology offices worldwide. Alternately referred to as superficial benign fibrous histiocytomas, dermatofibromas (DFs) typically manifest on lower extremities, are about twice as common in women as in men, and usually affect patients in their early 40s.

DFs appear most commonly as low, firm, round to ovoid, pinkish brown papules that dimple with lateral digital pressure. Though not pathognomic, the “dimple sign” is highly suggestive of this diagnosis. DF lesions can also manifest as firm, convex papules or nodules (as in this case) with the same coloring but without the dimple sign.

For years, DFs were believed to be a reaction to trauma (eg, bug bite). While this theory still has its adherents, more recent studies suggest these are true tumors composed of skin fibroblasts. Their ability to occur internally, even in bone, provides further evidence against their putatively reactive nature.

Histologically, the typical DF shows whorling fascicles of a fibroblastic spindle cell proliferation in the dermis. By contrast, the most dangerous item in the differential, the rare but greatly feared malignant dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, is characterized by a storiform (cartwheel-shaped) pattern of spindle cells.

DFs are often subject to trauma from shaving and therefore surgically removed. However, since this was not the case for this patient, she chose to leave her lesion in place.

A 48-year-old woman is referred to dermatology for examination of a lesion on her ankle. Although the patient is certain that it has remained unchanged for years, she takes her primary care provider’s recommendation and agrees to be seen. She says the lesion occasionally itches and has a “crawly” feeling to it, but its size remains consistent.

Located on the lateral aspect of her left ankle is a brownish red, firm, round, intradermal nodule. It measures 8.5 mm and has a faint brown macular halo around it. Biopsy shows multiple round fascicles of spindle cells proliferating in the dermis. Special stains rule out the possibility of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, the most serious item in the differential.

The patient’s medical history includes breast cancer and a significant family history of skin cancer.

An Agreeable Girl With a Stubborn Rash

ANSWER

The correct answer is impetigo (choice “a”). Impetigo is almost always secondary to another condition, such as contact or irritant dermatitis, eczema, or dry skin.

DISCUSSION

Impetigo is a superficial bacterial infection usually caused by a combination of strep and staph organisms. It requires a break in the skin to provide a point of entry for the organisms. In young children, scratching and picking at eczema, along with lip licking, exacerbate the barrier-breaching process.

The organisms that cause impetigo are typically benign, but this was not always the case. Prior to WWI, certain strains of strep were capable of triggering an immune response that resulted in kidney damage. These “nephritogenic” strains of the Streptococcus family caused acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (Bright disease), which, at that time, killed thousands each year. Fortunately, these strains are rare now.

In the pre-antibiotic days, when the average person bathed once a week, impetigo was highly contagious and serious enough that whole households were quarantined because of it.

Today, impetigo, once diagnosed, is relatively simple to manage. Mild cases can be treated with application of mupirocin ointment or cream three times a day. In this particular case, a 10-day course of an oral antibiotic (trimethoprim sulfa) was added, and the rash rapidly cleared.

ANSWER

The correct answer is impetigo (choice “a”). Impetigo is almost always secondary to another condition, such as contact or irritant dermatitis, eczema, or dry skin.

DISCUSSION

Impetigo is a superficial bacterial infection usually caused by a combination of strep and staph organisms. It requires a break in the skin to provide a point of entry for the organisms. In young children, scratching and picking at eczema, along with lip licking, exacerbate the barrier-breaching process.

The organisms that cause impetigo are typically benign, but this was not always the case. Prior to WWI, certain strains of strep were capable of triggering an immune response that resulted in kidney damage. These “nephritogenic” strains of the Streptococcus family caused acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (Bright disease), which, at that time, killed thousands each year. Fortunately, these strains are rare now.

In the pre-antibiotic days, when the average person bathed once a week, impetigo was highly contagious and serious enough that whole households were quarantined because of it.

Today, impetigo, once diagnosed, is relatively simple to manage. Mild cases can be treated with application of mupirocin ointment or cream three times a day. In this particular case, a 10-day course of an oral antibiotic (trimethoprim sulfa) was added, and the rash rapidly cleared.

ANSWER

The correct answer is impetigo (choice “a”). Impetigo is almost always secondary to another condition, such as contact or irritant dermatitis, eczema, or dry skin.

DISCUSSION

Impetigo is a superficial bacterial infection usually caused by a combination of strep and staph organisms. It requires a break in the skin to provide a point of entry for the organisms. In young children, scratching and picking at eczema, along with lip licking, exacerbate the barrier-breaching process.

The organisms that cause impetigo are typically benign, but this was not always the case. Prior to WWI, certain strains of strep were capable of triggering an immune response that resulted in kidney damage. These “nephritogenic” strains of the Streptococcus family caused acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (Bright disease), which, at that time, killed thousands each year. Fortunately, these strains are rare now.

In the pre-antibiotic days, when the average person bathed once a week, impetigo was highly contagious and serious enough that whole households were quarantined because of it.

Today, impetigo, once diagnosed, is relatively simple to manage. Mild cases can be treated with application of mupirocin ointment or cream three times a day. In this particular case, a 10-day course of an oral antibiotic (trimethoprim sulfa) was added, and the rash rapidly cleared.

Distraught parents of a 5-year-old girl are at their wit’s end dealing with their daughter’s perioral rash, which first appeared several months ago. Although they’ve consulted three different primary care providers, who rendered several diagnoses and numerous treatments, the rash continues to worsen. The parents worry about scarring, but they are more concerned that the rash may never clear at all.

Her treatments have included oral erythromycin, oral amoxicillin, topical anti-yeast cream, and various petroleum-based and hydrocortisone-containing OTC lip balms. In a moment of desperation, the parents even applied their son’s psoriasis cream (betamethasone) and diaper cream. These, too, had no effect.

Contactants had been considered as a possible source, causing the family to switch toothpaste brands and toothbrushes and eliminate mouthwash use—again, with no change.

Family history includes an atopic brother (eczema, asthma, seasonal allergies). The parents confirm that the patient has very sensitive skin and can’t tolerate many soaps and moisturizers. Before the rash manifested, they noticed she had a tendency to compulsively lick her lips.

The patient is quite fair-skinned, with red hair and blue eyes. The rash, which covers her entire perioral area, is impressively florid, red, and scaly. Focally, several areas of honey-colored crusts can be seen. The vermillion surfaces of the lips are unaffected except for slight focal fissuring. No nodes can be felt in the head or neck. The patient is in good spirits despite all this, and certainly not in any distress.

1-800-Zap-My-Zits

ANSWERThe correct diagnosis is discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE; choice “c”). For those unfamiliar with DLE, it is often mistaken for the other items listed. Biopsy can distinguish among them.

Fungal infection (dermatophytosis; choice “a”) of the face is unusual and would have responded in some way to the antifungal cream. Likewise, the use of steroid creams would have markedly worsened a fungal infection.

Although this could have been psoriasis (choice “b”), it’s rare for that condition to be confined to the face. It almost always appears elsewhere—the scalp, elbows, knees, and/or nails.

Dermatomyositis (choice “d”), an autoimmune condition, can certainly present with a bimalar rash. However, it is usually accompanied by additional symptoms, such as progressive weakness and muscle pain.

DISCUSSION

DLE can represent a stand-alone diagnosis, or it can be a manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). When present in this bimalar form, the lesions are often mistaken for the “butterfly rash” commonly seen in SLE.

This patient was thoroughly tested for SLE, and no evidence of it was found. Biopsy did, however, show changes consistent with DLE (interface dermatitis with increased mucin formation, among others).

The treatment for DLE is rather simple: It consists of sun protection and oral hydroxychloroquine. This helps reduce inflammation, although the patient will still have residual scarring.

ANSWERThe correct diagnosis is discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE; choice “c”). For those unfamiliar with DLE, it is often mistaken for the other items listed. Biopsy can distinguish among them.

Fungal infection (dermatophytosis; choice “a”) of the face is unusual and would have responded in some way to the antifungal cream. Likewise, the use of steroid creams would have markedly worsened a fungal infection.

Although this could have been psoriasis (choice “b”), it’s rare for that condition to be confined to the face. It almost always appears elsewhere—the scalp, elbows, knees, and/or nails.

Dermatomyositis (choice “d”), an autoimmune condition, can certainly present with a bimalar rash. However, it is usually accompanied by additional symptoms, such as progressive weakness and muscle pain.

DISCUSSION

DLE can represent a stand-alone diagnosis, or it can be a manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). When present in this bimalar form, the lesions are often mistaken for the “butterfly rash” commonly seen in SLE.

This patient was thoroughly tested for SLE, and no evidence of it was found. Biopsy did, however, show changes consistent with DLE (interface dermatitis with increased mucin formation, among others).

The treatment for DLE is rather simple: It consists of sun protection and oral hydroxychloroquine. This helps reduce inflammation, although the patient will still have residual scarring.

ANSWERThe correct diagnosis is discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE; choice “c”). For those unfamiliar with DLE, it is often mistaken for the other items listed. Biopsy can distinguish among them.

Fungal infection (dermatophytosis; choice “a”) of the face is unusual and would have responded in some way to the antifungal cream. Likewise, the use of steroid creams would have markedly worsened a fungal infection.

Although this could have been psoriasis (choice “b”), it’s rare for that condition to be confined to the face. It almost always appears elsewhere—the scalp, elbows, knees, and/or nails.

Dermatomyositis (choice “d”), an autoimmune condition, can certainly present with a bimalar rash. However, it is usually accompanied by additional symptoms, such as progressive weakness and muscle pain.

DISCUSSION

DLE can represent a stand-alone diagnosis, or it can be a manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). When present in this bimalar form, the lesions are often mistaken for the “butterfly rash” commonly seen in SLE.

This patient was thoroughly tested for SLE, and no evidence of it was found. Biopsy did, however, show changes consistent with DLE (interface dermatitis with increased mucin formation, among others).

The treatment for DLE is rather simple: It consists of sun protection and oral hydroxychloroquine. This helps reduce inflammation, although the patient will still have residual scarring.

A 52-year-old man is referred to dermatology by his primary care provider for evaluation of facial lesions that first appeared almost a year ago. The patient, who works as a welder, has noticed that sun exposure tends to exacerbate the problem. He denies joint pain, fever, and malaise. He self-diagnosed the condition as acne and ordered a product from a TV ad, but this cream only made things worse. The asymptomatic lesions persist, despite application of a number of prescription products (2.5% hydrocortisone cream, adapalene gel, and antifungal creams, including tolnaftate and clotrimazole). The eruption—comprised of discrete, round, scaly lesions—covers a good portion of the bimalar areas of his face. The lesions are purplish red, and on closer inspection, you observe patulous follicular orifices. Some of the older lesions have focal atrophy. The rest of the examination is unremarkable.

If at First You Don’t Succeed … Don’t Just Treat Again

ANSWER

Punch biopsy (choice “d”) is the correct answer for one simple reason: Correct diagnosis dictates correct treatment. What we’re missing is a diagnosis we can rely on.

DISCUSSION

This case demonstrates a major difference in outlook between the generalist and the specialist. The former is more interested in treating the problem, while the latter first wants to know what the problem is, then tailors the treatment to that problem and/or reassures the patient of the problem’s benign nature.

Had these lesions been of fungal origin, terbinafine would have had a positive effect. Furthermore, fungal infections are caused by organisms that only affect the outer layer of skin and create scaling, which was notably missing in this case.

Round to oval lesions suggest a number of diagnostic possibilities, only one of which is fungal (dermatophytosis). Others include T-cell lymphoma, psoriasis (though its lesions are almost always scaly), sarcoidosis, Hansen disease, lupus, and lichen planus. In cases like this one, these options need to be sorted through—and the only sure way to do that is with biopsy.

This patient’s biopsy showed a palisaded granulomatous process consistent with granuloma annulare (GA), a very commonly diagnosed benign condition. Since there are no ideal treatments for GA, he opted to do nothing, although he agreed to present for a biannual check-up. He was happy just to rule out all the things he didn’t have and thereby reduce his worries.

ANSWER

Punch biopsy (choice “d”) is the correct answer for one simple reason: Correct diagnosis dictates correct treatment. What we’re missing is a diagnosis we can rely on.

DISCUSSION

This case demonstrates a major difference in outlook between the generalist and the specialist. The former is more interested in treating the problem, while the latter first wants to know what the problem is, then tailors the treatment to that problem and/or reassures the patient of the problem’s benign nature.

Had these lesions been of fungal origin, terbinafine would have had a positive effect. Furthermore, fungal infections are caused by organisms that only affect the outer layer of skin and create scaling, which was notably missing in this case.

Round to oval lesions suggest a number of diagnostic possibilities, only one of which is fungal (dermatophytosis). Others include T-cell lymphoma, psoriasis (though its lesions are almost always scaly), sarcoidosis, Hansen disease, lupus, and lichen planus. In cases like this one, these options need to be sorted through—and the only sure way to do that is with biopsy.

This patient’s biopsy showed a palisaded granulomatous process consistent with granuloma annulare (GA), a very commonly diagnosed benign condition. Since there are no ideal treatments for GA, he opted to do nothing, although he agreed to present for a biannual check-up. He was happy just to rule out all the things he didn’t have and thereby reduce his worries.

ANSWER

Punch biopsy (choice “d”) is the correct answer for one simple reason: Correct diagnosis dictates correct treatment. What we’re missing is a diagnosis we can rely on.

DISCUSSION

This case demonstrates a major difference in outlook between the generalist and the specialist. The former is more interested in treating the problem, while the latter first wants to know what the problem is, then tailors the treatment to that problem and/or reassures the patient of the problem’s benign nature.

Had these lesions been of fungal origin, terbinafine would have had a positive effect. Furthermore, fungal infections are caused by organisms that only affect the outer layer of skin and create scaling, which was notably missing in this case.

Round to oval lesions suggest a number of diagnostic possibilities, only one of which is fungal (dermatophytosis). Others include T-cell lymphoma, psoriasis (though its lesions are almost always scaly), sarcoidosis, Hansen disease, lupus, and lichen planus. In cases like this one, these options need to be sorted through—and the only sure way to do that is with biopsy.

This patient’s biopsy showed a palisaded granulomatous process consistent with granuloma annulare (GA), a very commonly diagnosed benign condition. Since there are no ideal treatments for GA, he opted to do nothing, although he agreed to present for a biannual check-up. He was happy just to rule out all the things he didn’t have and thereby reduce his worries.

A 39-year-old man presents with asymptomatic lesions on both arms. When they manifested about six months ago, the patient diagnosed himself with “ringworm” and began treating them with an OTC clotrimazole cream his pharmacist recommended. Twice-daily application for two weeks did not result in a change, so the patient consulted his primary care provider (PCP), who also thought the problem was fungal. The PCP prescribed oral terbinafine (250 mg/d), which the patient took for a month without improvement. He then requested a referral to dermatology. The patient denies fever, malaise, shortness of breath, or unexplained weight loss. He is not taking any prescription medications. Both medial triceps have almost identical lesions: brownish red and oval, with well-defined margins. The margins are slightly raised relative to the central portions. The lesions, which measure 8 x 10 cm, exhibit no epidermal changes (eg, scale or papularity); they are totally intradermal. The rest of the examination is unremarkable.

Moles: Their Role in Skin Cancer Diagnosis

ANSWER

The correct answer is none of the above (choice “d”). These lesions are all intradermal nevi, which have little, if any, risk for malignant transformation. Deeper nevi are considered quite safe, unless significant change has occurred. Despite the unlikelihood, however, it is risky to declare a 0% chance of skin cancer.

DISCUSSION

Slow growth and increased prominence are not the kinds of changes to look for in skin lesions. Rather, look for marked asymmetry (eg, the growth of a new, darker, macular component) or other change in color or consistency.

Hairs on these lesions are quite normal and are actually reassuring in confirming their benign nature. Skin cancers seldom support hair growth.

Most melanomas don’t come from moles. Instead, they are “de novo” lesions, literally coming from nothing, out of clear skin. It is true that the more moles someone has, the greater his or her risk for skin cancer, though not necessarily in one of the moles. When melanomas do develop from nevi (a collection of a certain type of melanocyte), this usually occurs in superficial types, such as compound or junctional nevi. From an objective standpoint, in this patient’s case, family history means nothing.

What does matter is to pay as much attention to the owner as to the lesion. The more fair-skinned and sun-damaged (freckles, blue eyes, red hair) the patient is, the more worrisome a lesion can be.

This patient had none of those traits, and she will likely have one of her lesions surgically excised to ensure she’s satisfied with the resulting scar. Of course, the tissue sample will be sent for pathologic examination, as any specimen should be.

ANSWER

The correct answer is none of the above (choice “d”). These lesions are all intradermal nevi, which have little, if any, risk for malignant transformation. Deeper nevi are considered quite safe, unless significant change has occurred. Despite the unlikelihood, however, it is risky to declare a 0% chance of skin cancer.

DISCUSSION

Slow growth and increased prominence are not the kinds of changes to look for in skin lesions. Rather, look for marked asymmetry (eg, the growth of a new, darker, macular component) or other change in color or consistency.

Hairs on these lesions are quite normal and are actually reassuring in confirming their benign nature. Skin cancers seldom support hair growth.

Most melanomas don’t come from moles. Instead, they are “de novo” lesions, literally coming from nothing, out of clear skin. It is true that the more moles someone has, the greater his or her risk for skin cancer, though not necessarily in one of the moles. When melanomas do develop from nevi (a collection of a certain type of melanocyte), this usually occurs in superficial types, such as compound or junctional nevi. From an objective standpoint, in this patient’s case, family history means nothing.

What does matter is to pay as much attention to the owner as to the lesion. The more fair-skinned and sun-damaged (freckles, blue eyes, red hair) the patient is, the more worrisome a lesion can be.

This patient had none of those traits, and she will likely have one of her lesions surgically excised to ensure she’s satisfied with the resulting scar. Of course, the tissue sample will be sent for pathologic examination, as any specimen should be.

ANSWER

The correct answer is none of the above (choice “d”). These lesions are all intradermal nevi, which have little, if any, risk for malignant transformation. Deeper nevi are considered quite safe, unless significant change has occurred. Despite the unlikelihood, however, it is risky to declare a 0% chance of skin cancer.

DISCUSSION

Slow growth and increased prominence are not the kinds of changes to look for in skin lesions. Rather, look for marked asymmetry (eg, the growth of a new, darker, macular component) or other change in color or consistency.

Hairs on these lesions are quite normal and are actually reassuring in confirming their benign nature. Skin cancers seldom support hair growth.

Most melanomas don’t come from moles. Instead, they are “de novo” lesions, literally coming from nothing, out of clear skin. It is true that the more moles someone has, the greater his or her risk for skin cancer, though not necessarily in one of the moles. When melanomas do develop from nevi (a collection of a certain type of melanocyte), this usually occurs in superficial types, such as compound or junctional nevi. From an objective standpoint, in this patient’s case, family history means nothing.

What does matter is to pay as much attention to the owner as to the lesion. The more fair-skinned and sun-damaged (freckles, blue eyes, red hair) the patient is, the more worrisome a lesion can be.

This patient had none of those traits, and she will likely have one of her lesions surgically excised to ensure she’s satisfied with the resulting scar. Of course, the tissue sample will be sent for pathologic examination, as any specimen should be.

A 39-year-old woman self-refers for evaluation of moles she’s had on her face “all her life.” They have become more prominent with age, and many now have hairs growing in them. They are often traumatized by contact with fingernails or clothing. The patient worries that they might “turn into cancer” the way her grandfather’s moles did. The patient looks her stated age, is moderately overweight, and has more than her share of moles (some of which exceed 6 mm in diameter.) For the most part, they are skin-colored, and several are hair-bearing. Further questioning reveals that her moles manifested during puberty and have not been present “all her life.” Her type II skin is otherwise unremarkable and free of sun damage.

Ear “Wart” Prompts Unkind Comments

ANSWER

The correct answer is nevus sebaceous (choice “b”), a rather common hamartomatous congenital tumor. The diagnosis was confirmed by pathologic examination of a tiny sample from the most papular portion of the lesion.

Given the lesion’s congenital nature and complete lack of response to treatment, wart (choice “a”) was quite unlikely. And although trichofolliculoma (choice “c”) and epidermal nevus (choice “d”) were possible differential items, the former usually appears much later in life and the latter is usually more dry and rough to the touch.

DISCUSSION

Nevus sebaceous (NS) of Jadassohn was first described in 1895 by a Swedish dermatologist who had seen a series of young patients with hairless plaques in the scalp or on surrounding neck or facial skin. Pathologic exam confirmed them to be organoid nevi representing an overgrowth of sebaceous glands.

Over time, it became clear that NS affects all genders and races equally. For most patients, the lesions are of cosmetic concern due to the lack of hair. But it has also been established that NS can develop in areas, including the face, ears, and neck, on which they may be cosmetically significant and difficult to remove.

Concern arose when reports began to surface that NS could undergo malignant transformation, especially in larger scalp lesions that are subject to years of excess UV exposure. This was the driving force behind the common practice of removing NS at puberty. We now know that although basal or squamous cell carcinoma, or even melanoma, can develop in longstanding NS, the frequency is probably far less than previously thought.

Most cases of NS in the scalp are easy to diagnose by their pink color, plaquish morphology, and mammillated hairless surface (coupled with congenital manifestation). But a few, such as this patient’s ear lesion, require biopsy for confirmation. As this patient ages, he may feel the need to have the rest of it surgically removed.

ANSWER

The correct answer is nevus sebaceous (choice “b”), a rather common hamartomatous congenital tumor. The diagnosis was confirmed by pathologic examination of a tiny sample from the most papular portion of the lesion.

Given the lesion’s congenital nature and complete lack of response to treatment, wart (choice “a”) was quite unlikely. And although trichofolliculoma (choice “c”) and epidermal nevus (choice “d”) were possible differential items, the former usually appears much later in life and the latter is usually more dry and rough to the touch.

DISCUSSION

Nevus sebaceous (NS) of Jadassohn was first described in 1895 by a Swedish dermatologist who had seen a series of young patients with hairless plaques in the scalp or on surrounding neck or facial skin. Pathologic exam confirmed them to be organoid nevi representing an overgrowth of sebaceous glands.

Over time, it became clear that NS affects all genders and races equally. For most patients, the lesions are of cosmetic concern due to the lack of hair. But it has also been established that NS can develop in areas, including the face, ears, and neck, on which they may be cosmetically significant and difficult to remove.

Concern arose when reports began to surface that NS could undergo malignant transformation, especially in larger scalp lesions that are subject to years of excess UV exposure. This was the driving force behind the common practice of removing NS at puberty. We now know that although basal or squamous cell carcinoma, or even melanoma, can develop in longstanding NS, the frequency is probably far less than previously thought.

Most cases of NS in the scalp are easy to diagnose by their pink color, plaquish morphology, and mammillated hairless surface (coupled with congenital manifestation). But a few, such as this patient’s ear lesion, require biopsy for confirmation. As this patient ages, he may feel the need to have the rest of it surgically removed.

ANSWER

The correct answer is nevus sebaceous (choice “b”), a rather common hamartomatous congenital tumor. The diagnosis was confirmed by pathologic examination of a tiny sample from the most papular portion of the lesion.

Given the lesion’s congenital nature and complete lack of response to treatment, wart (choice “a”) was quite unlikely. And although trichofolliculoma (choice “c”) and epidermal nevus (choice “d”) were possible differential items, the former usually appears much later in life and the latter is usually more dry and rough to the touch.

DISCUSSION

Nevus sebaceous (NS) of Jadassohn was first described in 1895 by a Swedish dermatologist who had seen a series of young patients with hairless plaques in the scalp or on surrounding neck or facial skin. Pathologic exam confirmed them to be organoid nevi representing an overgrowth of sebaceous glands.

Over time, it became clear that NS affects all genders and races equally. For most patients, the lesions are of cosmetic concern due to the lack of hair. But it has also been established that NS can develop in areas, including the face, ears, and neck, on which they may be cosmetically significant and difficult to remove.

Concern arose when reports began to surface that NS could undergo malignant transformation, especially in larger scalp lesions that are subject to years of excess UV exposure. This was the driving force behind the common practice of removing NS at puberty. We now know that although basal or squamous cell carcinoma, or even melanoma, can develop in longstanding NS, the frequency is probably far less than previously thought.

Most cases of NS in the scalp are easy to diagnose by their pink color, plaquish morphology, and mammillated hairless surface (coupled with congenital manifestation). But a few, such as this patient’s ear lesion, require biopsy for confirmation. As this patient ages, he may feel the need to have the rest of it surgically removed.

An 8-year-old boy is referred to dermatology for evaluation and treatment of a “wart” on the inferior rim of his left helix that has been present (and unchanged) since birth. The lesion is asymptomatic, and the boy’s biggest complaint is that it makes him the object of unkind comments from his siblings and friends. The patient’s mother claims the child is otherwise healthy; there is no history of seizure or other neurologic problems, and he does not have any medical conditions requiring treatment. The lesion has been treated, unsuccessfully, with a variety of wart remedies, including salicylic acid-based products and liquid nitrogen. Along the inferior rim of the left helix is a 5-cm linear collection of soft, skin-colored papules that range in size from pinpoint to 2.5 mm. They are so small and flesh-toned as to easily escape detection unless specifically sought. No other significant lesions are seen on the ear or elsewhere on the head or neck. The child looks his stated age and appears well developed and well nourished.

Man Is in Thick of Skin Problem

ANSWER

The correct answer is palmoplantar hyperkeratosis (PPK; choice “c”). As a category, it includes many conditions that are characterized by a heterogeneous thickening of the palms and soles, although each has distinct features.

Psoriasis (choice “a”) can present in somewhat similar fashion. However, it rarely appears so early in life and almost never involves such uniform hyperkeratosis.

Xerosis (choice “b”) merely means dry skin—a common enough problem, but one that does not involve such uniform and deep hyperkeratosis. It is almost never congenital.

Occult cancers (eg, GI, breast) can occasionally trigger a hyperkeratotic “perineoplastic” reaction (choice “d”) in the palms, soles, and other areas. However, it is acquired relatively late in life.

DISCUSSION

PPK is a relatively common problem, especially in those of northern European ancestry. The incidence in Northern Ireland, for example, is 4.4/100,000. In its more severe forms, such as this case, it can be debilitating.

Categorization of this extraordinarily diverse group of disorders is a challenge, to say the least. For purposes of this discussion, let’s start with this patient’s condition and then clarify its place in the panoply of hyperkeratotic disorders.

Our patient has one of the more common forms of diffuse PPK, generically called nonepidermolytic PPK, which presents with a waxy, uniform yellowed hyperkeratosis confined to the palms and soles. The old eponymic term for it was Unna-Thost disorder, named for the Viennese and Norwegian dermatologists who first described it late in the 19th century. A more modern term is tylosis, but many variations exist. This particular form is inherited in autosomal dominant fashion, but other forms of PPK can be transmitted by autosomal recessive or even X-linked genes.

Other types include focal (thick calluses over points of friction, especially on the feet) versions that can present in linear configuration and punctate forms with deep calluses on palms and soles that can be discrete or widespread, with lesions that range in size from pinpoint (“speculated”) to pea-sized.

New-onset PPK should prompt a search for an occult malignancy. In terms of establishing a firm diagnosis, punch biopsy can be performed for clarification when necessary.

As might be expected, treatment is difficult at best. Urea or salicylic acid–based topical preparations can help to thin it out. This patient was started on acitretin, an oral retinoid (artificial form of vitamin A) that may help; it was one of the few treatments he hadn’t already tried. A one-month course of terbinafine had already been tried, without success, just in case there was any secondary fungal involvement—a fairly common complication of PPK.

ANSWER

The correct answer is palmoplantar hyperkeratosis (PPK; choice “c”). As a category, it includes many conditions that are characterized by a heterogeneous thickening of the palms and soles, although each has distinct features.

Psoriasis (choice “a”) can present in somewhat similar fashion. However, it rarely appears so early in life and almost never involves such uniform hyperkeratosis.

Xerosis (choice “b”) merely means dry skin—a common enough problem, but one that does not involve such uniform and deep hyperkeratosis. It is almost never congenital.

Occult cancers (eg, GI, breast) can occasionally trigger a hyperkeratotic “perineoplastic” reaction (choice “d”) in the palms, soles, and other areas. However, it is acquired relatively late in life.

DISCUSSION

PPK is a relatively common problem, especially in those of northern European ancestry. The incidence in Northern Ireland, for example, is 4.4/100,000. In its more severe forms, such as this case, it can be debilitating.

Categorization of this extraordinarily diverse group of disorders is a challenge, to say the least. For purposes of this discussion, let’s start with this patient’s condition and then clarify its place in the panoply of hyperkeratotic disorders.

Our patient has one of the more common forms of diffuse PPK, generically called nonepidermolytic PPK, which presents with a waxy, uniform yellowed hyperkeratosis confined to the palms and soles. The old eponymic term for it was Unna-Thost disorder, named for the Viennese and Norwegian dermatologists who first described it late in the 19th century. A more modern term is tylosis, but many variations exist. This particular form is inherited in autosomal dominant fashion, but other forms of PPK can be transmitted by autosomal recessive or even X-linked genes.

Other types include focal (thick calluses over points of friction, especially on the feet) versions that can present in linear configuration and punctate forms with deep calluses on palms and soles that can be discrete or widespread, with lesions that range in size from pinpoint (“speculated”) to pea-sized.

New-onset PPK should prompt a search for an occult malignancy. In terms of establishing a firm diagnosis, punch biopsy can be performed for clarification when necessary.

As might be expected, treatment is difficult at best. Urea or salicylic acid–based topical preparations can help to thin it out. This patient was started on acitretin, an oral retinoid (artificial form of vitamin A) that may help; it was one of the few treatments he hadn’t already tried. A one-month course of terbinafine had already been tried, without success, just in case there was any secondary fungal involvement—a fairly common complication of PPK.

ANSWER

The correct answer is palmoplantar hyperkeratosis (PPK; choice “c”). As a category, it includes many conditions that are characterized by a heterogeneous thickening of the palms and soles, although each has distinct features.

Psoriasis (choice “a”) can present in somewhat similar fashion. However, it rarely appears so early in life and almost never involves such uniform hyperkeratosis.

Xerosis (choice “b”) merely means dry skin—a common enough problem, but one that does not involve such uniform and deep hyperkeratosis. It is almost never congenital.

Occult cancers (eg, GI, breast) can occasionally trigger a hyperkeratotic “perineoplastic” reaction (choice “d”) in the palms, soles, and other areas. However, it is acquired relatively late in life.

DISCUSSION

PPK is a relatively common problem, especially in those of northern European ancestry. The incidence in Northern Ireland, for example, is 4.4/100,000. In its more severe forms, such as this case, it can be debilitating.

Categorization of this extraordinarily diverse group of disorders is a challenge, to say the least. For purposes of this discussion, let’s start with this patient’s condition and then clarify its place in the panoply of hyperkeratotic disorders.

Our patient has one of the more common forms of diffuse PPK, generically called nonepidermolytic PPK, which presents with a waxy, uniform yellowed hyperkeratosis confined to the palms and soles. The old eponymic term for it was Unna-Thost disorder, named for the Viennese and Norwegian dermatologists who first described it late in the 19th century. A more modern term is tylosis, but many variations exist. This particular form is inherited in autosomal dominant fashion, but other forms of PPK can be transmitted by autosomal recessive or even X-linked genes.

Other types include focal (thick calluses over points of friction, especially on the feet) versions that can present in linear configuration and punctate forms with deep calluses on palms and soles that can be discrete or widespread, with lesions that range in size from pinpoint (“speculated”) to pea-sized.

New-onset PPK should prompt a search for an occult malignancy. In terms of establishing a firm diagnosis, punch biopsy can be performed for clarification when necessary.

As might be expected, treatment is difficult at best. Urea or salicylic acid–based topical preparations can help to thin it out. This patient was started on acitretin, an oral retinoid (artificial form of vitamin A) that may help; it was one of the few treatments he hadn’t already tried. A one-month course of terbinafine had already been tried, without success, just in case there was any secondary fungal involvement—a fairly common complication of PPK.

Since birth, a now 60-year-old man has been affected by the same dermatologic condition as several members of his mother’s family. As he has aged, the problem has become more intrusive: His hands and feet are rough and painful, and he experiences loss of sensation, particularly on his soles. Over the years, he has been evaluated in multiple venues, both private practices and medical schools, by a variety of providers, including pediatricians and dermatologists. Many treatments have been tried; few have produced any good effect. Still seeking an explanation for his condition, he self-refers to dermatology. Evaluation reveals that the surfaces of both feet and hands are uniformly covered by rough and, in some focal areas, waxy hyperkeratotic skin. The nails, hair, teeth, and dorsal surfaces of the extremities are unaffected. The patient’s affect and level of intelligence appear well within normal limits.

Lesion Is Tender and Bleeds Copiously

ANSWER

The correct answer is pyogenic granuloma (choice “d”), further discussion of which follows. Bacillary angiomatosis (choice “a”) is a lesion caused by infection with a species of Bartonella—a distinctly unusual problem. While a retained foreign body (choice “b”), such as a splinter, could trigger a similar lesion, there was no relevant history to suggest this was the case here. The most concerning differential item, melanoma (choice “c”), can present as a glistening red nodule, especially in children, but this too would be quite unusual.

DISCUSSION

Pyogenic granuloma (PG) was the name originally given to these common lesions, which are neither pyogenic (pus producing) nor truly granulomatous (demonstrating a classic histologic pattern). Rather, they are the body’s frustrated attempt to lay down new blood supply in a healing but oft-traumatized lesion (eg, acne lesion, tag, nevus, or wart).

Other names for them include sclerosing hemangioma and lobular capillary hemangioma. Their appearance can vary from the classic look seen in this case to older lesions that tend to be drier and more warty.

PGs are far more common in children than in adults and greatly favor females over males. Pregnancy appears to trigger them, especially in the mouth, but they can appear on fingers, nipples, or even the scalp. Certain drugs, such as isotretinoin and certain chemotherapy agents, predispose to their formation.

PGs removed from children (by shave technique, followed by electrodesiccation and curettage) must be sent for pathologic examination to rule out nodular melanoma. That’s what was done in this case, with the pathology report confirming the expected vascular nature of the lesion.

ANSWER

The correct answer is pyogenic granuloma (choice “d”), further discussion of which follows. Bacillary angiomatosis (choice “a”) is a lesion caused by infection with a species of Bartonella—a distinctly unusual problem. While a retained foreign body (choice “b”), such as a splinter, could trigger a similar lesion, there was no relevant history to suggest this was the case here. The most concerning differential item, melanoma (choice “c”), can present as a glistening red nodule, especially in children, but this too would be quite unusual.

DISCUSSION

Pyogenic granuloma (PG) was the name originally given to these common lesions, which are neither pyogenic (pus producing) nor truly granulomatous (demonstrating a classic histologic pattern). Rather, they are the body’s frustrated attempt to lay down new blood supply in a healing but oft-traumatized lesion (eg, acne lesion, tag, nevus, or wart).

Other names for them include sclerosing hemangioma and lobular capillary hemangioma. Their appearance can vary from the classic look seen in this case to older lesions that tend to be drier and more warty.

PGs are far more common in children than in adults and greatly favor females over males. Pregnancy appears to trigger them, especially in the mouth, but they can appear on fingers, nipples, or even the scalp. Certain drugs, such as isotretinoin and certain chemotherapy agents, predispose to their formation.

PGs removed from children (by shave technique, followed by electrodesiccation and curettage) must be sent for pathologic examination to rule out nodular melanoma. That’s what was done in this case, with the pathology report confirming the expected vascular nature of the lesion.

ANSWER

The correct answer is pyogenic granuloma (choice “d”), further discussion of which follows. Bacillary angiomatosis (choice “a”) is a lesion caused by infection with a species of Bartonella—a distinctly unusual problem. While a retained foreign body (choice “b”), such as a splinter, could trigger a similar lesion, there was no relevant history to suggest this was the case here. The most concerning differential item, melanoma (choice “c”), can present as a glistening red nodule, especially in children, but this too would be quite unusual.

DISCUSSION

Pyogenic granuloma (PG) was the name originally given to these common lesions, which are neither pyogenic (pus producing) nor truly granulomatous (demonstrating a classic histologic pattern). Rather, they are the body’s frustrated attempt to lay down new blood supply in a healing but oft-traumatized lesion (eg, acne lesion, tag, nevus, or wart).

Other names for them include sclerosing hemangioma and lobular capillary hemangioma. Their appearance can vary from the classic look seen in this case to older lesions that tend to be drier and more warty.

PGs are far more common in children than in adults and greatly favor females over males. Pregnancy appears to trigger them, especially in the mouth, but they can appear on fingers, nipples, or even the scalp. Certain drugs, such as isotretinoin and certain chemotherapy agents, predispose to their formation.

PGs removed from children (by shave technique, followed by electrodesiccation and curettage) must be sent for pathologic examination to rule out nodular melanoma. That’s what was done in this case, with the pathology report confirming the expected vascular nature of the lesion.

The lesion on the face of this 16-year-old girl is slightly tender to the touch and bleeds copiously with even minor trauma. It manifested several months ago and has persisted even after a course of oral antibiotics (trimethoprim/sulfa) as well as twice-daily application of mupirocin ointment. Prior to the lesion’s appearance, the girl experienced an acne flare. Her mother, who is present, says her daughter “just couldn’t leave it alone” and was often observed picking at the problem area. The patient is otherwise healthy. The lesion in question measures about 1.6 cm. It comprises a round, flesh-colored, 1-cm nodule in the center of which is a bright red, glistening 5-mm papule. There is no erythema in or around the lesion or any palpable adenopathy. The rest of the patient’s exposed skin is unremarkable.

Finding Spot-on Treatment for Acne

ANSWER

The correct answer is food (choice “a”), which for many generations has been blamed for worsening acne (along with other nonfactors, such as makeup). All the others are demonstrably involved in the genesis and perpetuation of acne.

DISCUSSION

Teenagers have a hard enough time dealing with acne and other vicissitudes of puberty, and then they get blamed for eating the wrong kinds of food …. Would that it could be that simple! I think it’s important for us as providers to set the record straight by making sure parents and patients know what matters and what doesn’t.

When we’ve done that, the patient (or occasionally a parent) might say, “Well, every time I eat (insert item here), my acne flares.” To which we of course reply, “Well then, don’t do that!” After all, we certainly wouldn’t object to the patient consuming a better diet.

Once the unimportance of pizza, makeup, and soft drinks has been established, there remains the opportunity to enlighten the patient (and family) about the factors that do play a significant role—all but one of which can be addressed. (The exception, of course, is heredity; still, I believe it’s important to recognize its role in acne.) We can reduce the amount of sebum through use of retinoids and cut down on bacteria by using oral or topical antibiotics (though erythromycin is not especially effective). Hormonal therapy can be accomplished with oral contraceptives or oral spironolactone, though neither is perfect.

Treatment

This particular patient was prescribed a six-month course of isotretinoin (40 mg/d), after which her acne was completely and permanently gone. This is the result in about 70% of cases when this medicine is used correctly.

Proper procedure, including pregnancy tests and blood work, was followed before the patient was placed on the medication. The decision to use it was made after a careful discussion of other options, most of which she had already exhausted, and of the risks versus benefits of all available choices.

The biggest obstacle to starting the patient on isotretinoin was the perception that the drug is dangerous. It certainly must be used with caution, in carefully selected patients, and after a full disclosure of the associated risks. But when used appropriately, it is an effective treatment for acne that has failed to respond to other medications.

Summary

Acne is an extremely common complaint and happens to be exceedingly well studied. There are numerous treatment options, although none is perfect. Our job is to guide patients and families through the maze of information to plan a course of action acceptable to all.

ANSWER

The correct answer is food (choice “a”), which for many generations has been blamed for worsening acne (along with other nonfactors, such as makeup). All the others are demonstrably involved in the genesis and perpetuation of acne.

DISCUSSION

Teenagers have a hard enough time dealing with acne and other vicissitudes of puberty, and then they get blamed for eating the wrong kinds of food …. Would that it could be that simple! I think it’s important for us as providers to set the record straight by making sure parents and patients know what matters and what doesn’t.

When we’ve done that, the patient (or occasionally a parent) might say, “Well, every time I eat (insert item here), my acne flares.” To which we of course reply, “Well then, don’t do that!” After all, we certainly wouldn’t object to the patient consuming a better diet.

Once the unimportance of pizza, makeup, and soft drinks has been established, there remains the opportunity to enlighten the patient (and family) about the factors that do play a significant role—all but one of which can be addressed. (The exception, of course, is heredity; still, I believe it’s important to recognize its role in acne.) We can reduce the amount of sebum through use of retinoids and cut down on bacteria by using oral or topical antibiotics (though erythromycin is not especially effective). Hormonal therapy can be accomplished with oral contraceptives or oral spironolactone, though neither is perfect.

Treatment

This particular patient was prescribed a six-month course of isotretinoin (40 mg/d), after which her acne was completely and permanently gone. This is the result in about 70% of cases when this medicine is used correctly.

Proper procedure, including pregnancy tests and blood work, was followed before the patient was placed on the medication. The decision to use it was made after a careful discussion of other options, most of which she had already exhausted, and of the risks versus benefits of all available choices.

The biggest obstacle to starting the patient on isotretinoin was the perception that the drug is dangerous. It certainly must be used with caution, in carefully selected patients, and after a full disclosure of the associated risks. But when used appropriately, it is an effective treatment for acne that has failed to respond to other medications.

Summary

Acne is an extremely common complaint and happens to be exceedingly well studied. There are numerous treatment options, although none is perfect. Our job is to guide patients and families through the maze of information to plan a course of action acceptable to all.

ANSWER

The correct answer is food (choice “a”), which for many generations has been blamed for worsening acne (along with other nonfactors, such as makeup). All the others are demonstrably involved in the genesis and perpetuation of acne.

DISCUSSION

Teenagers have a hard enough time dealing with acne and other vicissitudes of puberty, and then they get blamed for eating the wrong kinds of food …. Would that it could be that simple! I think it’s important for us as providers to set the record straight by making sure parents and patients know what matters and what doesn’t.

When we’ve done that, the patient (or occasionally a parent) might say, “Well, every time I eat (insert item here), my acne flares.” To which we of course reply, “Well then, don’t do that!” After all, we certainly wouldn’t object to the patient consuming a better diet.

Once the unimportance of pizza, makeup, and soft drinks has been established, there remains the opportunity to enlighten the patient (and family) about the factors that do play a significant role—all but one of which can be addressed. (The exception, of course, is heredity; still, I believe it’s important to recognize its role in acne.) We can reduce the amount of sebum through use of retinoids and cut down on bacteria by using oral or topical antibiotics (though erythromycin is not especially effective). Hormonal therapy can be accomplished with oral contraceptives or oral spironolactone, though neither is perfect.

Treatment

This particular patient was prescribed a six-month course of isotretinoin (40 mg/d), after which her acne was completely and permanently gone. This is the result in about 70% of cases when this medicine is used correctly.

Proper procedure, including pregnancy tests and blood work, was followed before the patient was placed on the medication. The decision to use it was made after a careful discussion of other options, most of which she had already exhausted, and of the risks versus benefits of all available choices.

The biggest obstacle to starting the patient on isotretinoin was the perception that the drug is dangerous. It certainly must be used with caution, in carefully selected patients, and after a full disclosure of the associated risks. But when used appropriately, it is an effective treatment for acne that has failed to respond to other medications.

Summary

Acne is an extremely common complaint and happens to be exceedingly well studied. There are numerous treatment options, although none is perfect. Our job is to guide patients and families through the maze of information to plan a course of action acceptable to all.

An 18-year-old woman is brought in by her mother for evaluation of longstanding acne. Although she is otherwise healthy, the patient has a significant family history of acne and recounts an extensive personal history of treatment attempts with both OTC and prescription products. Among these are several different benzoyl peroxide–based formulations (including one she bought after seeing an ad on TV) and devices including an electric scrub brush. None has had a significant impact. Tretinoin gel and oral erythromycin—prescribed by the patient’s primary care provider—haven’t helped much, either. The patient’s periods are regular and normal. She claims to be sexually abstinent. Examination reveals moderately severe acne confined to the patient’s face. Numerous open and closed comedones can be seen, as well as several pus-filled pimples. Scarring is minimal but present, especially on the sides of the face.