User login

The Ears Have It (and She Doesn’t Want It)

ANSWER

The correct answer is to obtain a biopsy (choice “d”), the results of which would likely dictate rational and effective treatment. The other choices are largely empirical and not based on available evidence.

DISCUSSION

In this case, the biopsy (with samples from the arm rash as well as from the ears) showed unequivocal evidence of connective tissue disease—almost certainly lupus.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) has protean manifestations because it can affect so many different organs in so many different ways. Reduced to its simplest elements, lupus is an autoimmune process that results in a form of vasculitis that can affect any perfused tissue.

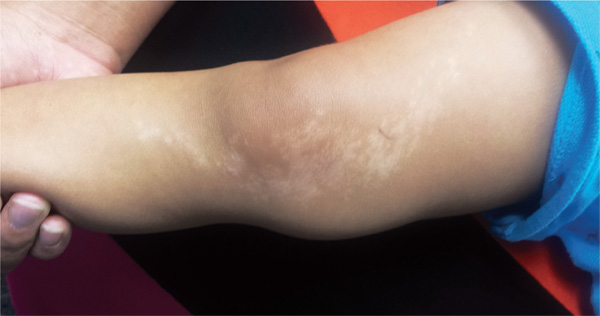

In terms of the skin, the visible manifestations of lupus are numerous and not always obvious. Sun is a known exacerbating factor, as this case demonstrated quite well: The patient’s rash was pronounced on sun-exposed skin but spared covered skin. When this was brought to her attention, the patient recalled a baby-sitting job earlier in the year (summer) that had required her to spend time outdoors. She also acknowledged that her smoking habit often took her into the backyard, where she would stand in the sun.

That being said, neither the arm rash nor the ear changes are “typical” of lupus (although the latter did include patulous follicular orifices, enlarged pores often seen focally with lupus). The effect is simply the result of the patient’s normal dark skin color; on a white person, the discoloration would have been pink or red.

Although these changes were suspicious for lupus, it was necessary to establish the diagnosis by biopsy—especially since the patient was already being treated for the disease. With that accomplished, the patient was sent back to her rheumatologist, who indicated he would probably treat her with a biologic, plus or minus methotrexate.

ANSWER

The correct answer is to obtain a biopsy (choice “d”), the results of which would likely dictate rational and effective treatment. The other choices are largely empirical and not based on available evidence.

DISCUSSION

In this case, the biopsy (with samples from the arm rash as well as from the ears) showed unequivocal evidence of connective tissue disease—almost certainly lupus.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) has protean manifestations because it can affect so many different organs in so many different ways. Reduced to its simplest elements, lupus is an autoimmune process that results in a form of vasculitis that can affect any perfused tissue.

In terms of the skin, the visible manifestations of lupus are numerous and not always obvious. Sun is a known exacerbating factor, as this case demonstrated quite well: The patient’s rash was pronounced on sun-exposed skin but spared covered skin. When this was brought to her attention, the patient recalled a baby-sitting job earlier in the year (summer) that had required her to spend time outdoors. She also acknowledged that her smoking habit often took her into the backyard, where she would stand in the sun.

That being said, neither the arm rash nor the ear changes are “typical” of lupus (although the latter did include patulous follicular orifices, enlarged pores often seen focally with lupus). The effect is simply the result of the patient’s normal dark skin color; on a white person, the discoloration would have been pink or red.

Although these changes were suspicious for lupus, it was necessary to establish the diagnosis by biopsy—especially since the patient was already being treated for the disease. With that accomplished, the patient was sent back to her rheumatologist, who indicated he would probably treat her with a biologic, plus or minus methotrexate.

ANSWER

The correct answer is to obtain a biopsy (choice “d”), the results of which would likely dictate rational and effective treatment. The other choices are largely empirical and not based on available evidence.

DISCUSSION

In this case, the biopsy (with samples from the arm rash as well as from the ears) showed unequivocal evidence of connective tissue disease—almost certainly lupus.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) has protean manifestations because it can affect so many different organs in so many different ways. Reduced to its simplest elements, lupus is an autoimmune process that results in a form of vasculitis that can affect any perfused tissue.

In terms of the skin, the visible manifestations of lupus are numerous and not always obvious. Sun is a known exacerbating factor, as this case demonstrated quite well: The patient’s rash was pronounced on sun-exposed skin but spared covered skin. When this was brought to her attention, the patient recalled a baby-sitting job earlier in the year (summer) that had required her to spend time outdoors. She also acknowledged that her smoking habit often took her into the backyard, where she would stand in the sun.

That being said, neither the arm rash nor the ear changes are “typical” of lupus (although the latter did include patulous follicular orifices, enlarged pores often seen focally with lupus). The effect is simply the result of the patient’s normal dark skin color; on a white person, the discoloration would have been pink or red.

Although these changes were suspicious for lupus, it was necessary to establish the diagnosis by biopsy—especially since the patient was already being treated for the disease. With that accomplished, the patient was sent back to her rheumatologist, who indicated he would probably treat her with a biologic, plus or minus methotrexate.

A 34-year-old black woman is sent to dermatology by her rheumatologist for evaluation of changes to her ears that began several months ago. The patient reports no symptoms, but she is quite distressed by the appearance of her ears. She has been under the care of the rheumatologist for several years for her systemic lupus erythematosus. She takes hydroxychloroquine (400 mg/d), which she says controls most of her systemic symptoms (ie, joint pain and malaise). Further history taking reveals that, within the time frame of the ear changes, the patient also developed an itchy rash on both arms. Application of triamcinolone 0.1% cream has not helped. On examination, the changes to the patient’s ears are immediately obvious: the dark brown to black discoloration contrasts sharply with her light brown skin. In addition to the color change, the surface of the ears is scaly and rough, with enlarged pores evident. There is no redness or swelling noted; palpation elicits neither increased warmth nor adenopathy around the ears or on the adjacent neck. The scaly rash on the patient’s arms is remarkably symmetrical. It affects the sun-exposed lateral portions of both arms, sparing the skin on the medial aspects and on the proximal portions normally covered by clothing.

Boy Wrestles With Scalp Problem

ANSWER

The correct answer is all of the above (choice “e”). This particular form of tinea capitis is called black dot tinea capitis (BDTC), a somewhat unusual dermatophytosis (superficial fungal infection) that mostly affects children. The causative organisms are anthropophilic—that is, acquired from human sources, such as other children, during activities that involve skin-to-skin contact (eg, sports).

The vast majority of these organisms are from the Trichophyton family, such as T tonsurans or T violaceum. They invade the hair shaft itself, leaving the hard covering (the cuticle) intact. The black dots represent the tips of broken-off hairs, themselves full of fungal elements, seen in the photomicrograph. The term endothrix is given to this kind of fungal infection, in which the organisms are contained within the hair shaft, which, as a result, becomes brittle and breaks off. This is a relatively common type of infection.

A more unusual form of tinea capitis is caused by zoophilic organisms, such as Microsporum canis (from dogs and cats), Microsporum gypseum (pigs or cows), or T equinum (horses). These infect the external surface of the hair shaft, breaking down the cuticle. This allows for identification of the infection by Wood’s lamp, which causes the affected area to turn a yellowish color. These infections also tend to provoke a more brisk inflammatory response in the victim and are more difficult to treat.

Diagnosis can be made from a combination of clinical findings, KOH prep (as in this patient), and/or fungal culture.

Treatment can entail griseofulvin or terbinafine; the case patient was treated with a two-month course of the latter (125 mg/d). Topical treatment is of limited usefulness.

ANSWER

The correct answer is all of the above (choice “e”). This particular form of tinea capitis is called black dot tinea capitis (BDTC), a somewhat unusual dermatophytosis (superficial fungal infection) that mostly affects children. The causative organisms are anthropophilic—that is, acquired from human sources, such as other children, during activities that involve skin-to-skin contact (eg, sports).

The vast majority of these organisms are from the Trichophyton family, such as T tonsurans or T violaceum. They invade the hair shaft itself, leaving the hard covering (the cuticle) intact. The black dots represent the tips of broken-off hairs, themselves full of fungal elements, seen in the photomicrograph. The term endothrix is given to this kind of fungal infection, in which the organisms are contained within the hair shaft, which, as a result, becomes brittle and breaks off. This is a relatively common type of infection.

A more unusual form of tinea capitis is caused by zoophilic organisms, such as Microsporum canis (from dogs and cats), Microsporum gypseum (pigs or cows), or T equinum (horses). These infect the external surface of the hair shaft, breaking down the cuticle. This allows for identification of the infection by Wood’s lamp, which causes the affected area to turn a yellowish color. These infections also tend to provoke a more brisk inflammatory response in the victim and are more difficult to treat.

Diagnosis can be made from a combination of clinical findings, KOH prep (as in this patient), and/or fungal culture.

Treatment can entail griseofulvin or terbinafine; the case patient was treated with a two-month course of the latter (125 mg/d). Topical treatment is of limited usefulness.

ANSWER

The correct answer is all of the above (choice “e”). This particular form of tinea capitis is called black dot tinea capitis (BDTC), a somewhat unusual dermatophytosis (superficial fungal infection) that mostly affects children. The causative organisms are anthropophilic—that is, acquired from human sources, such as other children, during activities that involve skin-to-skin contact (eg, sports).

The vast majority of these organisms are from the Trichophyton family, such as T tonsurans or T violaceum. They invade the hair shaft itself, leaving the hard covering (the cuticle) intact. The black dots represent the tips of broken-off hairs, themselves full of fungal elements, seen in the photomicrograph. The term endothrix is given to this kind of fungal infection, in which the organisms are contained within the hair shaft, which, as a result, becomes brittle and breaks off. This is a relatively common type of infection.

A more unusual form of tinea capitis is caused by zoophilic organisms, such as Microsporum canis (from dogs and cats), Microsporum gypseum (pigs or cows), or T equinum (horses). These infect the external surface of the hair shaft, breaking down the cuticle. This allows for identification of the infection by Wood’s lamp, which causes the affected area to turn a yellowish color. These infections also tend to provoke a more brisk inflammatory response in the victim and are more difficult to treat.

Diagnosis can be made from a combination of clinical findings, KOH prep (as in this patient), and/or fungal culture.

Treatment can entail griseofulvin or terbinafine; the case patient was treated with a two-month course of the latter (125 mg/d). Topical treatment is of limited usefulness.

An 8-year-old boy is brought in by his mother for evaluation of a scalp condition that manifested several months ago. The first sign was hair loss in several locations, mostly on the sides, followed in a few weeks by faint scaling. As more hair came out, the scaling in the affected locations reduced, but uniformly spaced black dots began to appear. There has never been any redness. The boy was taken to a local urgent care center, where he was diagnosed with probable “ringworm” and given a prescription for topical antifungal cream (clotrimazole, bid application). This failed to help, so the family sought an appointment with dermatology. Additional history-taking reveals that the boy noticed the problem within a few weeks of starting wrestling at school. Examination of the scalp reveals several round areas of partial and uniform hair loss, averaging 3 cm in diameter. No redness or edema is seen, and only very faint scaling is observed on the surface of the skin. Distinct black dots are uniformly distributed within the lesions. A vigorous scrape of one of the areas is processed with potassium hydroxide 10% and examined under 10x magnification. The black dots are found to be broken-off hairs filled with hundreds of tiny round spheres. Several hyphae are seen adjacent to the hairs. Palpation reveals adenopathy in the adjacent nuchal scalp and neck. Wood’s lamp examination fails to highlight these areas.

Painful Lesion Hasn’t Responded to Antibiotics

ANSWER

The correct answer is erythema nodosum (EN; choice “c”), a reactive form of septal panniculitis with many potential triggers.

Erythema induratum (choice “a”) is a manifestation of lobular panniculitis, which affects the fat lobules but not the septae. It too has numerous triggers, but it tends to manifest with more discrete nodules, which eventually open and drain. It is far less common than EN.

Urticaria (choice “b”), also known as hives, presents as itchy, stingy wheals that are typically evanescent (eg, they appear suddenly, within seconds, and disappear within hours). Despite the itching and stinging, urticaria rarely hurts when it presents on the skin.

Erysipelas (choice “d”) is a superficial form of skin infection. More superficial than cellulitis, it usually is caused by a member of the Streptococcus family. It has a bright red appearance and sharply demarcated margins, with a peau d’orange (dimpled, like an orange peel) effect on its surface. It is acute in origin and responds readily to most common antibiotics.

DISCUSSION

Erythema nodosum, a reactive process involving fibrous septae that support and separate subcutaneous adipocytes, is notable for the complete lack of epidermal change (eg, scaling, broken skin, pointing, draining). The incidence is about 2 in 10,000 population, with women outnumbering men at a rate of 4:1 and the 18-to-34 age-group most affected. The anterior leg is involved in the vast majority of cases.

EN often starts with flulike symptoms, followed by the appearance of discrete, bright red nodules, measuring 2 to 4 cm, on the anterior legs; these darken and coalesce over a period of seven to 10 weeks. New lesions can continue to appear for up to six weeks. As they progress, the lesions often become ecchymotic. Idiopathic cases (at least 20%) can last months.

Notable triggers include Crohn disease flares and use of drugs such as sulfa, gold salts, and oral contraceptives. Several infections have been identified as triggers, including strep, mycoplasma, and campylobacter, as well as deep fungal infections (histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, and sporotrichosis). More unusual causes include pregnancy and diseases such as sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, Behçet disease, and leukemia/lymphoma.

The diagnostic workup for EN includes punch biopsy of deep adipose tissue and throat culture, and when indicated, ASO titer (if strep is suspected) and chest films (to rule out tuberculosis and sarcoid). In most cases, the diagnosis can be made on clinical grounds alone, although the triggering entity may be difficult to identify. The identification and elimination of the underlying trigger is nonetheless crucial for diagnosis and treatment.

That issue aside, most cases of EN resolve with minimal treatment; this can include the use of NSAIDs and elevation of the limbs when possible. In this particular case, the intense pain the patient was experiencing called for stronger therapy (ibuprofen 800 mg tid, plus a two-week taper of prednisone 40 mg). She responded quite well, and the problem was almost totally resolved at a follow-up visit several weeks later.

In the absence of findings to the contrary, it is likely that the trigger for this patient’s EN was strep, given the timing of its manifestation after a sore throat.

ANSWER

The correct answer is erythema nodosum (EN; choice “c”), a reactive form of septal panniculitis with many potential triggers.

Erythema induratum (choice “a”) is a manifestation of lobular panniculitis, which affects the fat lobules but not the septae. It too has numerous triggers, but it tends to manifest with more discrete nodules, which eventually open and drain. It is far less common than EN.

Urticaria (choice “b”), also known as hives, presents as itchy, stingy wheals that are typically evanescent (eg, they appear suddenly, within seconds, and disappear within hours). Despite the itching and stinging, urticaria rarely hurts when it presents on the skin.

Erysipelas (choice “d”) is a superficial form of skin infection. More superficial than cellulitis, it usually is caused by a member of the Streptococcus family. It has a bright red appearance and sharply demarcated margins, with a peau d’orange (dimpled, like an orange peel) effect on its surface. It is acute in origin and responds readily to most common antibiotics.

DISCUSSION

Erythema nodosum, a reactive process involving fibrous septae that support and separate subcutaneous adipocytes, is notable for the complete lack of epidermal change (eg, scaling, broken skin, pointing, draining). The incidence is about 2 in 10,000 population, with women outnumbering men at a rate of 4:1 and the 18-to-34 age-group most affected. The anterior leg is involved in the vast majority of cases.

EN often starts with flulike symptoms, followed by the appearance of discrete, bright red nodules, measuring 2 to 4 cm, on the anterior legs; these darken and coalesce over a period of seven to 10 weeks. New lesions can continue to appear for up to six weeks. As they progress, the lesions often become ecchymotic. Idiopathic cases (at least 20%) can last months.

Notable triggers include Crohn disease flares and use of drugs such as sulfa, gold salts, and oral contraceptives. Several infections have been identified as triggers, including strep, mycoplasma, and campylobacter, as well as deep fungal infections (histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, and sporotrichosis). More unusual causes include pregnancy and diseases such as sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, Behçet disease, and leukemia/lymphoma.

The diagnostic workup for EN includes punch biopsy of deep adipose tissue and throat culture, and when indicated, ASO titer (if strep is suspected) and chest films (to rule out tuberculosis and sarcoid). In most cases, the diagnosis can be made on clinical grounds alone, although the triggering entity may be difficult to identify. The identification and elimination of the underlying trigger is nonetheless crucial for diagnosis and treatment.

That issue aside, most cases of EN resolve with minimal treatment; this can include the use of NSAIDs and elevation of the limbs when possible. In this particular case, the intense pain the patient was experiencing called for stronger therapy (ibuprofen 800 mg tid, plus a two-week taper of prednisone 40 mg). She responded quite well, and the problem was almost totally resolved at a follow-up visit several weeks later.

In the absence of findings to the contrary, it is likely that the trigger for this patient’s EN was strep, given the timing of its manifestation after a sore throat.

ANSWER

The correct answer is erythema nodosum (EN; choice “c”), a reactive form of septal panniculitis with many potential triggers.

Erythema induratum (choice “a”) is a manifestation of lobular panniculitis, which affects the fat lobules but not the septae. It too has numerous triggers, but it tends to manifest with more discrete nodules, which eventually open and drain. It is far less common than EN.

Urticaria (choice “b”), also known as hives, presents as itchy, stingy wheals that are typically evanescent (eg, they appear suddenly, within seconds, and disappear within hours). Despite the itching and stinging, urticaria rarely hurts when it presents on the skin.

Erysipelas (choice “d”) is a superficial form of skin infection. More superficial than cellulitis, it usually is caused by a member of the Streptococcus family. It has a bright red appearance and sharply demarcated margins, with a peau d’orange (dimpled, like an orange peel) effect on its surface. It is acute in origin and responds readily to most common antibiotics.

DISCUSSION

Erythema nodosum, a reactive process involving fibrous septae that support and separate subcutaneous adipocytes, is notable for the complete lack of epidermal change (eg, scaling, broken skin, pointing, draining). The incidence is about 2 in 10,000 population, with women outnumbering men at a rate of 4:1 and the 18-to-34 age-group most affected. The anterior leg is involved in the vast majority of cases.

EN often starts with flulike symptoms, followed by the appearance of discrete, bright red nodules, measuring 2 to 4 cm, on the anterior legs; these darken and coalesce over a period of seven to 10 weeks. New lesions can continue to appear for up to six weeks. As they progress, the lesions often become ecchymotic. Idiopathic cases (at least 20%) can last months.

Notable triggers include Crohn disease flares and use of drugs such as sulfa, gold salts, and oral contraceptives. Several infections have been identified as triggers, including strep, mycoplasma, and campylobacter, as well as deep fungal infections (histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, and sporotrichosis). More unusual causes include pregnancy and diseases such as sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, Behçet disease, and leukemia/lymphoma.

The diagnostic workup for EN includes punch biopsy of deep adipose tissue and throat culture, and when indicated, ASO titer (if strep is suspected) and chest films (to rule out tuberculosis and sarcoid). In most cases, the diagnosis can be made on clinical grounds alone, although the triggering entity may be difficult to identify. The identification and elimination of the underlying trigger is nonetheless crucial for diagnosis and treatment.

That issue aside, most cases of EN resolve with minimal treatment; this can include the use of NSAIDs and elevation of the limbs when possible. In this particular case, the intense pain the patient was experiencing called for stronger therapy (ibuprofen 800 mg tid, plus a two-week taper of prednisone 40 mg). She responded quite well, and the problem was almost totally resolved at a follow-up visit several weeks later.

In the absence of findings to the contrary, it is likely that the trigger for this patient’s EN was strep, given the timing of its manifestation after a sore throat.

A 57-year-old woman is referred to dermatology for “cellulitis” that has persisted despite several courses of oral antibiotics (including cephalexin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole). She denies taking any other medications and has no significant medical history. She states that the problem manifested as discrete red nodules, which eventually coalesced into a single large patch. At the time, she had just recovered from a sore throat and still felt a bit ill, although she denies cough, fever, and shortness of breath. Examination reveals a large (12 x 14 cm) red edematous plaque in the skin over her right anterior tibia. The deep intradermal and subdermal edema is exquisitely tender to touch, considerably warmer than the surrounding skin, and highly blanchable. No other changes are noted on the epidermal surface. A deep 5-mm punch biopsy is performed. Results show a dense lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the pannicular septae.

Scalp Mass Is Painful and Oozes Pus

ANSWER

The correct answer is oral terbinafine or griseofulvin, plus a two-week taper of prednisone (choice “d”); further discussion follows. Most authorities recommend the use of oral steroids with terbinafine (choice “a”) or griseofulvin (choice “b”), to dampen the acute inflammatory reaction to the fungal antigen. Some sources advise the use of itraconazole (choice “c”) but not as a single agent.

DISCUSSION

This case is a classic representation of kerion, a type of tinea capitis. This distinctive presentation results from not only active localized fungal infection with one of the dermatophytes, but also an allergic response to the fungal antigen. (This antigen can also trigger a widespread eczematous rash called an id reaction.) The resulting boggy, tender mass often oozes pus and usually provokes significant localized adenopathy.

A more common type of tinea capitis is uncomplicated dermatophytic infection of the scalp, presenting as mild localized scaling and modest hair loss, with no edema or redness to speak of. Kerion, by contrast, is far more acute and involves an impressive amount of localized redness and edema, along with modest hair loss, purulence, bloody drainage, and marked tenderness. Untreated, kerion can result in permanent scarring alopecia.

Several different dermatophytes have been isolated from kerions, including Trichophyton tonsurans, T violaceum, and various members of the Microsporum family. These zoophilic or geophilic organisms affect children far more than adults. Distinguishing the causative type is significant, because different drugs are required to effectively treat each. This is why a fungal culture is done at the outset.

When the diagnosis is in doubt, a punch biopsy may be necessary, with the sample divided for processing of default H&E stains and for fungal culture. Other information can be obtained by plucking a few hairs from the mass and examining them under 10x power to see if fungal hyphae are confined to the insides of the hair shafts (endothrix) or the outside of the shafts (ectothrix).

This is one situation in which KOH is not helpful for diagnosis: The organisms are too deep to obtain with a superficial scrape.

A number of scalp conditions can mimic a kerion, including lichen planopilaris and folliculitis decalvans. Several years ago, I had a patient who presented with a similar lesion that turned out to be squamous cell carcinoma—which eventually metastasized and led to his death.

TREATMENT

Treatment of more severe types of tinea capitis can be trying, even when the diagnosis is nailed down. The challenge becomes treating the problem long and strong enough to produce a cure.

In this case, I started the patient (who, at age 8, weighed 110 pounds) on a month-long course of terbinafine (250 mg/d) with a two-week taper of prednisone (40 mg). The expectation was that this would rapidly diminish the edema and pain while we waited for the culture results.

If the results showed the expected T tonsurans, treatment would continue as planned. If the cause turned out to be one of the Microsporum species, a switch to griseofulvin, at relatively high doses, would be considered.

ANSWER

The correct answer is oral terbinafine or griseofulvin, plus a two-week taper of prednisone (choice “d”); further discussion follows. Most authorities recommend the use of oral steroids with terbinafine (choice “a”) or griseofulvin (choice “b”), to dampen the acute inflammatory reaction to the fungal antigen. Some sources advise the use of itraconazole (choice “c”) but not as a single agent.

DISCUSSION

This case is a classic representation of kerion, a type of tinea capitis. This distinctive presentation results from not only active localized fungal infection with one of the dermatophytes, but also an allergic response to the fungal antigen. (This antigen can also trigger a widespread eczematous rash called an id reaction.) The resulting boggy, tender mass often oozes pus and usually provokes significant localized adenopathy.

A more common type of tinea capitis is uncomplicated dermatophytic infection of the scalp, presenting as mild localized scaling and modest hair loss, with no edema or redness to speak of. Kerion, by contrast, is far more acute and involves an impressive amount of localized redness and edema, along with modest hair loss, purulence, bloody drainage, and marked tenderness. Untreated, kerion can result in permanent scarring alopecia.

Several different dermatophytes have been isolated from kerions, including Trichophyton tonsurans, T violaceum, and various members of the Microsporum family. These zoophilic or geophilic organisms affect children far more than adults. Distinguishing the causative type is significant, because different drugs are required to effectively treat each. This is why a fungal culture is done at the outset.

When the diagnosis is in doubt, a punch biopsy may be necessary, with the sample divided for processing of default H&E stains and for fungal culture. Other information can be obtained by plucking a few hairs from the mass and examining them under 10x power to see if fungal hyphae are confined to the insides of the hair shafts (endothrix) or the outside of the shafts (ectothrix).

This is one situation in which KOH is not helpful for diagnosis: The organisms are too deep to obtain with a superficial scrape.

A number of scalp conditions can mimic a kerion, including lichen planopilaris and folliculitis decalvans. Several years ago, I had a patient who presented with a similar lesion that turned out to be squamous cell carcinoma—which eventually metastasized and led to his death.

TREATMENT

Treatment of more severe types of tinea capitis can be trying, even when the diagnosis is nailed down. The challenge becomes treating the problem long and strong enough to produce a cure.

In this case, I started the patient (who, at age 8, weighed 110 pounds) on a month-long course of terbinafine (250 mg/d) with a two-week taper of prednisone (40 mg). The expectation was that this would rapidly diminish the edema and pain while we waited for the culture results.

If the results showed the expected T tonsurans, treatment would continue as planned. If the cause turned out to be one of the Microsporum species, a switch to griseofulvin, at relatively high doses, would be considered.

ANSWER

The correct answer is oral terbinafine or griseofulvin, plus a two-week taper of prednisone (choice “d”); further discussion follows. Most authorities recommend the use of oral steroids with terbinafine (choice “a”) or griseofulvin (choice “b”), to dampen the acute inflammatory reaction to the fungal antigen. Some sources advise the use of itraconazole (choice “c”) but not as a single agent.

DISCUSSION

This case is a classic representation of kerion, a type of tinea capitis. This distinctive presentation results from not only active localized fungal infection with one of the dermatophytes, but also an allergic response to the fungal antigen. (This antigen can also trigger a widespread eczematous rash called an id reaction.) The resulting boggy, tender mass often oozes pus and usually provokes significant localized adenopathy.

A more common type of tinea capitis is uncomplicated dermatophytic infection of the scalp, presenting as mild localized scaling and modest hair loss, with no edema or redness to speak of. Kerion, by contrast, is far more acute and involves an impressive amount of localized redness and edema, along with modest hair loss, purulence, bloody drainage, and marked tenderness. Untreated, kerion can result in permanent scarring alopecia.

Several different dermatophytes have been isolated from kerions, including Trichophyton tonsurans, T violaceum, and various members of the Microsporum family. These zoophilic or geophilic organisms affect children far more than adults. Distinguishing the causative type is significant, because different drugs are required to effectively treat each. This is why a fungal culture is done at the outset.

When the diagnosis is in doubt, a punch biopsy may be necessary, with the sample divided for processing of default H&E stains and for fungal culture. Other information can be obtained by plucking a few hairs from the mass and examining them under 10x power to see if fungal hyphae are confined to the insides of the hair shafts (endothrix) or the outside of the shafts (ectothrix).

This is one situation in which KOH is not helpful for diagnosis: The organisms are too deep to obtain with a superficial scrape.

A number of scalp conditions can mimic a kerion, including lichen planopilaris and folliculitis decalvans. Several years ago, I had a patient who presented with a similar lesion that turned out to be squamous cell carcinoma—which eventually metastasized and led to his death.

TREATMENT

Treatment of more severe types of tinea capitis can be trying, even when the diagnosis is nailed down. The challenge becomes treating the problem long and strong enough to produce a cure.

In this case, I started the patient (who, at age 8, weighed 110 pounds) on a month-long course of terbinafine (250 mg/d) with a two-week taper of prednisone (40 mg). The expectation was that this would rapidly diminish the edema and pain while we waited for the culture results.

If the results showed the expected T tonsurans, treatment would continue as planned. If the cause turned out to be one of the Microsporum species, a switch to griseofulvin, at relatively high doses, would be considered.

Four weeks ago, an 8-year-old boy developed a lesion in his scalp that manifested rather quickly and caused pain. Treatment with both topical medications (triple-antibiotic cream and mupirocin cream) and oral antibiotics (cephalexin and trimethoprim/sulfa) has failed to resolve the problem, so his mother brings him to dermatology for evaluation. The patient is afebrile but complains of fatigue. His mother denies any other health problems for the child. There is no history of foreign travel, and the patient’s brother is healthy. The boy is in no acute distress but complains of tenderness on palpation of the lesion. The mass in his left nuchal scalp, which measures 4 cm, is impressively swollen, boggy, wet, and inflamed. Numerous red folliculocentric papules—many oozing pus—are seen on the surface. Located inferiorly to the lesion on the neck is a firm, palpable subcutaneous mass. Examination of the rest of the scalp reveals nothing of note. The clinical presentation and lack of response to oral antibiotics yield a presumptive diagnosis of kerion. A fungal culture is taken, with plans to prescribe appropriate medication.

Alarming Lesion Speaks for Itself

ANSWER

The correct answer is “all of the above” (choice “d”), for reasons discussed in the next section.

DISCUSSION

Cutaneous horn is the term given to this type of keratotic lesion, for obvious reasons. They range in size from a pinpoint to the larger lesion seen on this patient (and sometimes, even larger). The pathology report in this case confirmed the clinical impression of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC; choice “c”); sun exposure is the most likely causative factor, given the location and the patient’s history of sun damage.

The lesion might have been a wart (choice “a”) caused by a human papillomavirus, some of which can trigger the formation of a type of SCC. Evidence of HPV involvement is often noted in the pathology report.

When skin lesions transition from normal to sun-damaged to cancerous, they often go through an actinic keratosis (choice “b”) stage, usually as a tiny hyperkeratotic papule on the forehead, ears, nose, or other directly sun-exposed area. Some consider actinic keratoses to be a form of early SCC; more prevalent is the view that they are merely “precancerous” with the potential to develop into either a frank SCC or, less often, a basal cell carcinoma. Some actinic keratoses, left completely unmolested, can develop into tag-like lesions and then horny outward projections.

Even when cutaneous horns are found to represent SCC, they are termed well-differentiated, a descriptor meant to denote a relatively benign and nonaggressive prognosis. This is the opposite of a poorly differentiated SCC, which would be expected to behave in a more aggressive, less predictable manner.

For well-differentiated lesions, a deep shave biopsy is probably an adequate method of removal. As such, the case patient did not require re-excision. He was, however, scheduled for a return visit to check the site for the (albeit unlikely) possibility of recurrence.

ANSWER

The correct answer is “all of the above” (choice “d”), for reasons discussed in the next section.

DISCUSSION

Cutaneous horn is the term given to this type of keratotic lesion, for obvious reasons. They range in size from a pinpoint to the larger lesion seen on this patient (and sometimes, even larger). The pathology report in this case confirmed the clinical impression of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC; choice “c”); sun exposure is the most likely causative factor, given the location and the patient’s history of sun damage.

The lesion might have been a wart (choice “a”) caused by a human papillomavirus, some of which can trigger the formation of a type of SCC. Evidence of HPV involvement is often noted in the pathology report.

When skin lesions transition from normal to sun-damaged to cancerous, they often go through an actinic keratosis (choice “b”) stage, usually as a tiny hyperkeratotic papule on the forehead, ears, nose, or other directly sun-exposed area. Some consider actinic keratoses to be a form of early SCC; more prevalent is the view that they are merely “precancerous” with the potential to develop into either a frank SCC or, less often, a basal cell carcinoma. Some actinic keratoses, left completely unmolested, can develop into tag-like lesions and then horny outward projections.

Even when cutaneous horns are found to represent SCC, they are termed well-differentiated, a descriptor meant to denote a relatively benign and nonaggressive prognosis. This is the opposite of a poorly differentiated SCC, which would be expected to behave in a more aggressive, less predictable manner.

For well-differentiated lesions, a deep shave biopsy is probably an adequate method of removal. As such, the case patient did not require re-excision. He was, however, scheduled for a return visit to check the site for the (albeit unlikely) possibility of recurrence.

ANSWER

The correct answer is “all of the above” (choice “d”), for reasons discussed in the next section.

DISCUSSION

Cutaneous horn is the term given to this type of keratotic lesion, for obvious reasons. They range in size from a pinpoint to the larger lesion seen on this patient (and sometimes, even larger). The pathology report in this case confirmed the clinical impression of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC; choice “c”); sun exposure is the most likely causative factor, given the location and the patient’s history of sun damage.

The lesion might have been a wart (choice “a”) caused by a human papillomavirus, some of which can trigger the formation of a type of SCC. Evidence of HPV involvement is often noted in the pathology report.

When skin lesions transition from normal to sun-damaged to cancerous, they often go through an actinic keratosis (choice “b”) stage, usually as a tiny hyperkeratotic papule on the forehead, ears, nose, or other directly sun-exposed area. Some consider actinic keratoses to be a form of early SCC; more prevalent is the view that they are merely “precancerous” with the potential to develop into either a frank SCC or, less often, a basal cell carcinoma. Some actinic keratoses, left completely unmolested, can develop into tag-like lesions and then horny outward projections.

Even when cutaneous horns are found to represent SCC, they are termed well-differentiated, a descriptor meant to denote a relatively benign and nonaggressive prognosis. This is the opposite of a poorly differentiated SCC, which would be expected to behave in a more aggressive, less predictable manner.

For well-differentiated lesions, a deep shave biopsy is probably an adequate method of removal. As such, the case patient did not require re-excision. He was, however, scheduled for a return visit to check the site for the (albeit unlikely) possibility of recurrence.

Two years ago, this 82-year-old man developed a lesion on his forehead that has since grown large enough to cause pain with trauma. Furthermore, he recently reunited with some estranged family members, who upon seeing the lesion for the first time expressed alarm at its appearance. As a result, he requests a referral to dermatology for evaluation. The patient’s history includes several instances of skin cancer; these began when he was in his 40s and have all occurred on his face and scalp. Examination of those areas reveals heavy chronic sun damage, including solar elastosis, solar lentigines, and multiple relatively minor actinic keratoses. The patient has type II skin. An impressive 3 x 2.8–cm hornlike keratotic lesion projects prominently from his left forehead. The distal two-thirds is horny and firm, while the proximal base is pink, fleshy, and telangiectatic. The lesion is removed by saucerization under local anesthesia and submitted to pathology.

Parents Frightened by Son’s Thigh Lesion

ANSWER

The correct answer is lichen striatus (choice “d”), a rare, self-limited condition usually seen on the extremities of children. It will be discussed further in the next section.

The differential for lichen striatus includes psoriasis (choice “a”). However, typical psoriatic lesions would not assume this configuration and would likely manifest with other corroborative areas of involvement.

Eczema (choice “b”) is certainly common in children, but it is unlikely to be relegated to one linear area. The same can be said of pityriasis rosea (choice “c”).

DISCUSSION

Lichen striatus, also known as Blaschko linear acquired skin inflammation, is an unusual self-limited condition of unknown etiology seen mostly on the extremities of children ages 3 to 10. More common on legs than on arms, it can occasionally appear on the face.

Its linear configuration is instantly diagnostic: The lesion typically follows the Blaschko lines, which represent a segmental clone of cutaneous cells deposited at an embryonic stage of development.

As seen in this case, postinflammatory hypopigmentation is common. In a minority of cases, the condition can involve the entire length of the extremity—even the digits, where it can lead to dystrophy of the affected nail. It almost always resolves within a few weeks to months, with or without treatment (which is limited to symptom relief).

Several potential causes of lichen striatus have been posited. The most convincing theory is a possible connection with human herpesviruses 6 and 7, which are also triggers for pityriasis rosea. There have been cases in which both conditions are present, producing somewhat similar microscopic changes in the skin (and both resolving without treatment). Additional items in the differential include lichen planus, lichen nitidus, and warts.

TREATMENT

For most cases of lichen striatus, treatment is supportive: topical steroids for the itching, which is seldom severe. Given the self-limited but prolonged nature of the problem, patient education is the more important component; these days, there are web-based sources to which you can direct your patients for reliable information, including the Mayo Clinic and the American Academy of Dermatology.

ANSWER

The correct answer is lichen striatus (choice “d”), a rare, self-limited condition usually seen on the extremities of children. It will be discussed further in the next section.

The differential for lichen striatus includes psoriasis (choice “a”). However, typical psoriatic lesions would not assume this configuration and would likely manifest with other corroborative areas of involvement.

Eczema (choice “b”) is certainly common in children, but it is unlikely to be relegated to one linear area. The same can be said of pityriasis rosea (choice “c”).

DISCUSSION

Lichen striatus, also known as Blaschko linear acquired skin inflammation, is an unusual self-limited condition of unknown etiology seen mostly on the extremities of children ages 3 to 10. More common on legs than on arms, it can occasionally appear on the face.

Its linear configuration is instantly diagnostic: The lesion typically follows the Blaschko lines, which represent a segmental clone of cutaneous cells deposited at an embryonic stage of development.

As seen in this case, postinflammatory hypopigmentation is common. In a minority of cases, the condition can involve the entire length of the extremity—even the digits, where it can lead to dystrophy of the affected nail. It almost always resolves within a few weeks to months, with or without treatment (which is limited to symptom relief).

Several potential causes of lichen striatus have been posited. The most convincing theory is a possible connection with human herpesviruses 6 and 7, which are also triggers for pityriasis rosea. There have been cases in which both conditions are present, producing somewhat similar microscopic changes in the skin (and both resolving without treatment). Additional items in the differential include lichen planus, lichen nitidus, and warts.

TREATMENT

For most cases of lichen striatus, treatment is supportive: topical steroids for the itching, which is seldom severe. Given the self-limited but prolonged nature of the problem, patient education is the more important component; these days, there are web-based sources to which you can direct your patients for reliable information, including the Mayo Clinic and the American Academy of Dermatology.

ANSWER

The correct answer is lichen striatus (choice “d”), a rare, self-limited condition usually seen on the extremities of children. It will be discussed further in the next section.

The differential for lichen striatus includes psoriasis (choice “a”). However, typical psoriatic lesions would not assume this configuration and would likely manifest with other corroborative areas of involvement.

Eczema (choice “b”) is certainly common in children, but it is unlikely to be relegated to one linear area. The same can be said of pityriasis rosea (choice “c”).

DISCUSSION

Lichen striatus, also known as Blaschko linear acquired skin inflammation, is an unusual self-limited condition of unknown etiology seen mostly on the extremities of children ages 3 to 10. More common on legs than on arms, it can occasionally appear on the face.

Its linear configuration is instantly diagnostic: The lesion typically follows the Blaschko lines, which represent a segmental clone of cutaneous cells deposited at an embryonic stage of development.

As seen in this case, postinflammatory hypopigmentation is common. In a minority of cases, the condition can involve the entire length of the extremity—even the digits, where it can lead to dystrophy of the affected nail. It almost always resolves within a few weeks to months, with or without treatment (which is limited to symptom relief).

Several potential causes of lichen striatus have been posited. The most convincing theory is a possible connection with human herpesviruses 6 and 7, which are also triggers for pityriasis rosea. There have been cases in which both conditions are present, producing somewhat similar microscopic changes in the skin (and both resolving without treatment). Additional items in the differential include lichen planus, lichen nitidus, and warts.

TREATMENT

For most cases of lichen striatus, treatment is supportive: topical steroids for the itching, which is seldom severe. Given the self-limited but prolonged nature of the problem, patient education is the more important component; these days, there are web-based sources to which you can direct your patients for reliable information, including the Mayo Clinic and the American Academy of Dermatology.

A 6-year-old boy is brought in by his mother, referred to dermatology for evaluation of a lesion on his right thigh that manifested three months ago. Although asymptomatic, the lesion has frightened the boy’s parents. They first took him to a local urgent care clinic, where a diagnosis of “probable fungal infection” was made. But twice-daily application of the prescribed ketoconazole cream did not produce results. The boy is otherwise healthy, although he does have seasonal allergies. There is no family history of skin problems. The affected site is a hypopigmented linear patch of skin from the mid-medial right thigh to the mid-medial calf area. The width of the patch varies, from 3 to 5 cm. The margins are somewhat irregular, and in several places, slightly rough, scaly sections are noted. The hypopigmentation, though partial, is evident in the context of the boy’s type IV Hispanic skin. No erythema or edema is noted. Elsewhere, the child’s skin is free of significant changes or lesions.

Foot Rash + Gnarly Toenails = Man in Need of a Diagnosis

ANSWER

The correct answer is to perform a KOH examination (choice “b”), which takes just five minutes and offers the chance to establish the fungal origin of the rash. Although the patient’s skin is quite dry, the use of a moisturizer (choice “a”) is unlikely to address the overall problem. A punch biopsy (choice “c”) would be a logical choice if the KOH failed to solve the mystery. The use of combination creams (choice “d”) that contain a steroid (triamcinolone) and an antifungal (nystatin) is essentially an admission of the lack of a definitive diagnosis. For reasons discussed below, this strategy has almost no chance of helping.

DISCUSSION

In this case, the KOH prep showed numerous hyphal elements, confirming suspicions of a fungal origin. One potential source of these organisms was the patient’s feet, where fungal infection had been present for years (“more than 30,” questioning revealed).

A common scenario is one in which the patient applies a steroid cream to a bit of dry skin just above the feet, which allows the fungi to gain a “foothold” from which to spread upward onto the leg; this progress is assisted through scratching and additional steroid application. If no firm diagnosis is ever established, definitive treatment cannot be undertaken and the problem never resolves.

In my opinion, there is never a reason to prescribe a product containing nystatin. In 1950, when it was discovered by researchers working in New York State laboratories (after which it was named), its efficacy against Candida species represented a notable advance, given the limited drug choices available for that purpose. But it has little, if any, activity against the dermatophytes causing our patient’s problems. And the steroid (triamcinolone) in this combination product, far from adding any therapeutic benefit, effectively diminishes any natural immune response.

The other reason to refrain from prescribing nystatin is that, since its discovery, at least three generations of products that treat both fungi and yeast (the azoles, such as clotrimazole, econazole, and fluconazole) have become available and have been found to be very effective.

The more important issue in this case, however, is finally having an accurate diagnosis: tinea corporis, probably caused by the most common dermatophyte, Trichophyton rubrum. The patient’s body is obviously a very happy home for this ubiquitous organism, to the extent that our chances of eliminating it are quite small. But we can at least make the patient more comfortable.

Treatment entailed ketoconazole foam (applied bid to his legs) and a two-month course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d), which cleared up most of the skin problem. For his overgrown toenails, the patient was advised to establish care with a podiatrist for regular trimming.

In terms of a differential, this patient might have had psoriasis or eczema—and may still have one or both, since there’s no law against having more than one condition in the same location. In time, we may have to reconsider our solitary diagnosis.

ANSWER

The correct answer is to perform a KOH examination (choice “b”), which takes just five minutes and offers the chance to establish the fungal origin of the rash. Although the patient’s skin is quite dry, the use of a moisturizer (choice “a”) is unlikely to address the overall problem. A punch biopsy (choice “c”) would be a logical choice if the KOH failed to solve the mystery. The use of combination creams (choice “d”) that contain a steroid (triamcinolone) and an antifungal (nystatin) is essentially an admission of the lack of a definitive diagnosis. For reasons discussed below, this strategy has almost no chance of helping.

DISCUSSION

In this case, the KOH prep showed numerous hyphal elements, confirming suspicions of a fungal origin. One potential source of these organisms was the patient’s feet, where fungal infection had been present for years (“more than 30,” questioning revealed).

A common scenario is one in which the patient applies a steroid cream to a bit of dry skin just above the feet, which allows the fungi to gain a “foothold” from which to spread upward onto the leg; this progress is assisted through scratching and additional steroid application. If no firm diagnosis is ever established, definitive treatment cannot be undertaken and the problem never resolves.

In my opinion, there is never a reason to prescribe a product containing nystatin. In 1950, when it was discovered by researchers working in New York State laboratories (after which it was named), its efficacy against Candida species represented a notable advance, given the limited drug choices available for that purpose. But it has little, if any, activity against the dermatophytes causing our patient’s problems. And the steroid (triamcinolone) in this combination product, far from adding any therapeutic benefit, effectively diminishes any natural immune response.

The other reason to refrain from prescribing nystatin is that, since its discovery, at least three generations of products that treat both fungi and yeast (the azoles, such as clotrimazole, econazole, and fluconazole) have become available and have been found to be very effective.

The more important issue in this case, however, is finally having an accurate diagnosis: tinea corporis, probably caused by the most common dermatophyte, Trichophyton rubrum. The patient’s body is obviously a very happy home for this ubiquitous organism, to the extent that our chances of eliminating it are quite small. But we can at least make the patient more comfortable.

Treatment entailed ketoconazole foam (applied bid to his legs) and a two-month course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d), which cleared up most of the skin problem. For his overgrown toenails, the patient was advised to establish care with a podiatrist for regular trimming.

In terms of a differential, this patient might have had psoriasis or eczema—and may still have one or both, since there’s no law against having more than one condition in the same location. In time, we may have to reconsider our solitary diagnosis.

ANSWER

The correct answer is to perform a KOH examination (choice “b”), which takes just five minutes and offers the chance to establish the fungal origin of the rash. Although the patient’s skin is quite dry, the use of a moisturizer (choice “a”) is unlikely to address the overall problem. A punch biopsy (choice “c”) would be a logical choice if the KOH failed to solve the mystery. The use of combination creams (choice “d”) that contain a steroid (triamcinolone) and an antifungal (nystatin) is essentially an admission of the lack of a definitive diagnosis. For reasons discussed below, this strategy has almost no chance of helping.

DISCUSSION

In this case, the KOH prep showed numerous hyphal elements, confirming suspicions of a fungal origin. One potential source of these organisms was the patient’s feet, where fungal infection had been present for years (“more than 30,” questioning revealed).

A common scenario is one in which the patient applies a steroid cream to a bit of dry skin just above the feet, which allows the fungi to gain a “foothold” from which to spread upward onto the leg; this progress is assisted through scratching and additional steroid application. If no firm diagnosis is ever established, definitive treatment cannot be undertaken and the problem never resolves.

In my opinion, there is never a reason to prescribe a product containing nystatin. In 1950, when it was discovered by researchers working in New York State laboratories (after which it was named), its efficacy against Candida species represented a notable advance, given the limited drug choices available for that purpose. But it has little, if any, activity against the dermatophytes causing our patient’s problems. And the steroid (triamcinolone) in this combination product, far from adding any therapeutic benefit, effectively diminishes any natural immune response.

The other reason to refrain from prescribing nystatin is that, since its discovery, at least three generations of products that treat both fungi and yeast (the azoles, such as clotrimazole, econazole, and fluconazole) have become available and have been found to be very effective.

The more important issue in this case, however, is finally having an accurate diagnosis: tinea corporis, probably caused by the most common dermatophyte, Trichophyton rubrum. The patient’s body is obviously a very happy home for this ubiquitous organism, to the extent that our chances of eliminating it are quite small. But we can at least make the patient more comfortable.

Treatment entailed ketoconazole foam (applied bid to his legs) and a two-month course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d), which cleared up most of the skin problem. For his overgrown toenails, the patient was advised to establish care with a podiatrist for regular trimming.

In terms of a differential, this patient might have had psoriasis or eczema—and may still have one or both, since there’s no law against having more than one condition in the same location. In time, we may have to reconsider our solitary diagnosis.

For several years, a 66-year-old man has had an itchy rash on his right leg; recently, it has become more bothersome. In general, he has noticed that when cold weather arrives, the rash improves slightly, but it inevitably worsens again as winter progresses. Over the years, the providers he has consulted have prescribed a number of topical products—among them, antifungal and steroid creams. Each of these products seems to help for a short period, then stops; at that point, the patient switches to a different product, with similar mixed results. The patient says he doesn’t have any other skin problems. Examination reveals patches of dry skin scattered from the knee to the top of the patient’s foot. Most have a faintly erythematous surface and arciform borders. These patches blend into a similar rash that covers the sides of both feet. All 10 toenails are grossly dystrophic, yellowed, and overgrown. The skin on the patient’s other leg is somewhat dry but otherwise unaffected.

Hole in Jaw Has Drained Fluid for 20 Years

ANSWER

The correct answer is all of the above (choice “d”). The patient’s actual diagnosis, sinus tract of odontogenic origin (choice “a”), will be discussed further.

Branchial cleft cyst (choice “b”) is always in the differential for neck masses, and squamous cell carcinoma (choice “c”) should always be considered in cases of nonhealing lesions—although 20 years is an unlikely timeframe for that diagnosis! Additional differential possibilities include thyroglossal duct cyst and pyogenic granuloma.

DISCUSSION

Sinus tracts of odontogenic origin, also called dentocutaneous sinus tracts, are primarily caused by periapical abscesses. As the purulent material accumulates in the confined space around the apical area, pressure increases; this sets in motion a tunneling process that terminates in an outlet, often inside the mouth but also (often enough) on the skin.

In the latter instance, known as extraoral sinus, the opening forms along the chin or submental area. In 80% of cases, the source is the mandibular teeth.

Dermocutaneous sinuses of maxillary origin, though not unknown, are decidedly unusual. They can drain anywhere on the maxilla, including around the nose. In edentulous patients, retained tooth fragments or segments of apical abscesses can act as the nidus for this process.

When a draining sinus manifests more acutely or occurs in a patient from a high-risk area (eg, Mexico or Central America), other diagnoses must be considered. These include scrofula, in which regional nymph nodes, infected by Mycobacterium tuberculosis or atypical mycobacterial organism, break down and drain. The indolent nature and chronicity of this patient’s problem effectively ruled out this diagnosis.

Culture of the fluid draining from the abscess would reveal a number of organisms (mostly of the strep family) but would not show the actual causative bacteria, since they are typically anaerobic. Biopsy of the surrounding tissue is occasionally necessary, when squamous cell carcinoma or other neoplastic process is suspected.

TREATMENT

The patient was advised to see a dentist, who will likely obtain a panoramic radiograph of her teeth, with particular attention to the affected area.

If an abscess is identified, as expected, treatment would entail root canal or extraction. The sinus tract would then heal rather quickly.

Antibiotics would be of limited use without elimination of the pocket. However, when patients complain of discomfort or outright pain, antibiotics (eg, penicillin V potassium or amoxicillin/clavulanate) can help to reduce the inflammation and offer some relief.

ANSWER

The correct answer is all of the above (choice “d”). The patient’s actual diagnosis, sinus tract of odontogenic origin (choice “a”), will be discussed further.

Branchial cleft cyst (choice “b”) is always in the differential for neck masses, and squamous cell carcinoma (choice “c”) should always be considered in cases of nonhealing lesions—although 20 years is an unlikely timeframe for that diagnosis! Additional differential possibilities include thyroglossal duct cyst and pyogenic granuloma.

DISCUSSION

Sinus tracts of odontogenic origin, also called dentocutaneous sinus tracts, are primarily caused by periapical abscesses. As the purulent material accumulates in the confined space around the apical area, pressure increases; this sets in motion a tunneling process that terminates in an outlet, often inside the mouth but also (often enough) on the skin.

In the latter instance, known as extraoral sinus, the opening forms along the chin or submental area. In 80% of cases, the source is the mandibular teeth.

Dermocutaneous sinuses of maxillary origin, though not unknown, are decidedly unusual. They can drain anywhere on the maxilla, including around the nose. In edentulous patients, retained tooth fragments or segments of apical abscesses can act as the nidus for this process.

When a draining sinus manifests more acutely or occurs in a patient from a high-risk area (eg, Mexico or Central America), other diagnoses must be considered. These include scrofula, in which regional nymph nodes, infected by Mycobacterium tuberculosis or atypical mycobacterial organism, break down and drain. The indolent nature and chronicity of this patient’s problem effectively ruled out this diagnosis.

Culture of the fluid draining from the abscess would reveal a number of organisms (mostly of the strep family) but would not show the actual causative bacteria, since they are typically anaerobic. Biopsy of the surrounding tissue is occasionally necessary, when squamous cell carcinoma or other neoplastic process is suspected.

TREATMENT

The patient was advised to see a dentist, who will likely obtain a panoramic radiograph of her teeth, with particular attention to the affected area.

If an abscess is identified, as expected, treatment would entail root canal or extraction. The sinus tract would then heal rather quickly.

Antibiotics would be of limited use without elimination of the pocket. However, when patients complain of discomfort or outright pain, antibiotics (eg, penicillin V potassium or amoxicillin/clavulanate) can help to reduce the inflammation and offer some relief.

ANSWER

The correct answer is all of the above (choice “d”). The patient’s actual diagnosis, sinus tract of odontogenic origin (choice “a”), will be discussed further.

Branchial cleft cyst (choice “b”) is always in the differential for neck masses, and squamous cell carcinoma (choice “c”) should always be considered in cases of nonhealing lesions—although 20 years is an unlikely timeframe for that diagnosis! Additional differential possibilities include thyroglossal duct cyst and pyogenic granuloma.

DISCUSSION

Sinus tracts of odontogenic origin, also called dentocutaneous sinus tracts, are primarily caused by periapical abscesses. As the purulent material accumulates in the confined space around the apical area, pressure increases; this sets in motion a tunneling process that terminates in an outlet, often inside the mouth but also (often enough) on the skin.

In the latter instance, known as extraoral sinus, the opening forms along the chin or submental area. In 80% of cases, the source is the mandibular teeth.

Dermocutaneous sinuses of maxillary origin, though not unknown, are decidedly unusual. They can drain anywhere on the maxilla, including around the nose. In edentulous patients, retained tooth fragments or segments of apical abscesses can act as the nidus for this process.

When a draining sinus manifests more acutely or occurs in a patient from a high-risk area (eg, Mexico or Central America), other diagnoses must be considered. These include scrofula, in which regional nymph nodes, infected by Mycobacterium tuberculosis or atypical mycobacterial organism, break down and drain. The indolent nature and chronicity of this patient’s problem effectively ruled out this diagnosis.

Culture of the fluid draining from the abscess would reveal a number of organisms (mostly of the strep family) but would not show the actual causative bacteria, since they are typically anaerobic. Biopsy of the surrounding tissue is occasionally necessary, when squamous cell carcinoma or other neoplastic process is suspected.

TREATMENT

The patient was advised to see a dentist, who will likely obtain a panoramic radiograph of her teeth, with particular attention to the affected area.

If an abscess is identified, as expected, treatment would entail root canal or extraction. The sinus tract would then heal rather quickly.

Antibiotics would be of limited use without elimination of the pocket. However, when patients complain of discomfort or outright pain, antibiotics (eg, penicillin V potassium or amoxicillin/clavulanate) can help to reduce the inflammation and offer some relief.

A 74-year-old woman is referred to dermatology by the primary care provider at her nursing home. She has a small hole on her left jaw that has drained foul-smelling material for more than 20 years. Although the site has never been painful, it occasionally swells and becomes slightly sensitive before slowly returning to its usual small size over a period of weeks. The patient is in generally poor health, with early dementia, chronic congestive heart failure, and diabetes. All her teeth were removed almost 30 years ago. She is afebrile and in no acute distress. On the submental aspect of her left jaw, there is a round, 6-cm area of skin that is retracted and fixed around a centrally placed sinus opening (measuring about 2 to 3 mm). A scant amount of purulent-looking fluid can be expressed from the spot. The area is faintly pink, but there is no evidence of increased warmth or tenderness on palpation.

Child With “Distressing” Problem

ANSWER

The correct answer is nevus sebaceous (choice “a”). This benign hamartomatous lesion is derived from local tissue and grows at the same rate.

It differs considerably from the other items in the differential, including aplasia cutis congenita (choice “b”). In this condition, a focal area of epidermis simply fails to develop, leaving a permanent hairless scar that contrasts sharply with the raised, mammillated plaque of nevus sebaceous.

Epidermal nevus (choice “c”) is usually a collection of tan to brown superficial nevoid papules that can be linear, agminated, or plaque-like. These lesions lack the color and mammillated surface of those seen in nevus sebaceous.

Neonatal lupus (choice “d”) can present at birth with hairless, cicatricial inflamed lesions. However, these tend to resolve quickly, often leaving focal scarring alopecia but no plaque formation.

DISCUSSION

Nevus sebaceous (NS), first described by Jadassohn in 1895, has long been recognized as an unusual but by no means rare congenital lesion. Occurring equally in both sexes and comprising sebaceous glands in a nevoid morphologic context, NS is considered a variant of sebaceous nevi and verrucous epidermal nevi in some circles. All three are derived from overgrowth of local, normal tissues that typically grow at the same rate as surrounding structures.

The vast majority of NS lesions are found in the scalp, although they can also develop on the ear or neck and, rarely, elsewhere on the body. This patient’s plaque—with its uniform surface; tiny, smooth, shiny papules; and (perhaps most important) total lack of hair—is typical. Other classic features are congenital onset and permanent nature, which distinguish them from the rest of the differential.

Focal malignant transformation of NS lesions has been reported—in fact, this author has seen two such cases in 30 years. Both were small basal cell carcinomas, although cases of melanoma and other malignancies have been reported.

Such changes are rare enough that most experts consider prophylactic removal to be unwarranted. Watching the lesions for change over the years is certainly reasonable, as is protecting them from sun exposure.

Surgical removal—usually performed by a plastic surgeon—is occasionally necessary for cosmetic reasons. This is particularly so when NS covers a portion of the face, or when the cosmetic implications of having a hairless plaque in the scalp are sufficiently distressing.

This patient and her parents were educated about the nature of the diagnosis and apprised of their options.

Editor's note: For a similar presentation with a very different diagnosis, see the March 2015 DermaDiagnosis case (http://bit.ly/1ye69Ym).

ANSWER

The correct answer is nevus sebaceous (choice “a”). This benign hamartomatous lesion is derived from local tissue and grows at the same rate.

It differs considerably from the other items in the differential, including aplasia cutis congenita (choice “b”). In this condition, a focal area of epidermis simply fails to develop, leaving a permanent hairless scar that contrasts sharply with the raised, mammillated plaque of nevus sebaceous.

Epidermal nevus (choice “c”) is usually a collection of tan to brown superficial nevoid papules that can be linear, agminated, or plaque-like. These lesions lack the color and mammillated surface of those seen in nevus sebaceous.

Neonatal lupus (choice “d”) can present at birth with hairless, cicatricial inflamed lesions. However, these tend to resolve quickly, often leaving focal scarring alopecia but no plaque formation.

DISCUSSION

Nevus sebaceous (NS), first described by Jadassohn in 1895, has long been recognized as an unusual but by no means rare congenital lesion. Occurring equally in both sexes and comprising sebaceous glands in a nevoid morphologic context, NS is considered a variant of sebaceous nevi and verrucous epidermal nevi in some circles. All three are derived from overgrowth of local, normal tissues that typically grow at the same rate as surrounding structures.

The vast majority of NS lesions are found in the scalp, although they can also develop on the ear or neck and, rarely, elsewhere on the body. This patient’s plaque—with its uniform surface; tiny, smooth, shiny papules; and (perhaps most important) total lack of hair—is typical. Other classic features are congenital onset and permanent nature, which distinguish them from the rest of the differential.

Focal malignant transformation of NS lesions has been reported—in fact, this author has seen two such cases in 30 years. Both were small basal cell carcinomas, although cases of melanoma and other malignancies have been reported.

Such changes are rare enough that most experts consider prophylactic removal to be unwarranted. Watching the lesions for change over the years is certainly reasonable, as is protecting them from sun exposure.

Surgical removal—usually performed by a plastic surgeon—is occasionally necessary for cosmetic reasons. This is particularly so when NS covers a portion of the face, or when the cosmetic implications of having a hairless plaque in the scalp are sufficiently distressing.

This patient and her parents were educated about the nature of the diagnosis and apprised of their options.

Editor's note: For a similar presentation with a very different diagnosis, see the March 2015 DermaDiagnosis case (http://bit.ly/1ye69Ym).

ANSWER

The correct answer is nevus sebaceous (choice “a”). This benign hamartomatous lesion is derived from local tissue and grows at the same rate.

It differs considerably from the other items in the differential, including aplasia cutis congenita (choice “b”). In this condition, a focal area of epidermis simply fails to develop, leaving a permanent hairless scar that contrasts sharply with the raised, mammillated plaque of nevus sebaceous.

Epidermal nevus (choice “c”) is usually a collection of tan to brown superficial nevoid papules that can be linear, agminated, or plaque-like. These lesions lack the color and mammillated surface of those seen in nevus sebaceous.

Neonatal lupus (choice “d”) can present at birth with hairless, cicatricial inflamed lesions. However, these tend to resolve quickly, often leaving focal scarring alopecia but no plaque formation.

DISCUSSION

Nevus sebaceous (NS), first described by Jadassohn in 1895, has long been recognized as an unusual but by no means rare congenital lesion. Occurring equally in both sexes and comprising sebaceous glands in a nevoid morphologic context, NS is considered a variant of sebaceous nevi and verrucous epidermal nevi in some circles. All three are derived from overgrowth of local, normal tissues that typically grow at the same rate as surrounding structures.

The vast majority of NS lesions are found in the scalp, although they can also develop on the ear or neck and, rarely, elsewhere on the body. This patient’s plaque—with its uniform surface; tiny, smooth, shiny papules; and (perhaps most important) total lack of hair—is typical. Other classic features are congenital onset and permanent nature, which distinguish them from the rest of the differential.

Focal malignant transformation of NS lesions has been reported—in fact, this author has seen two such cases in 30 years. Both were small basal cell carcinomas, although cases of melanoma and other malignancies have been reported.

Such changes are rare enough that most experts consider prophylactic removal to be unwarranted. Watching the lesions for change over the years is certainly reasonable, as is protecting them from sun exposure.

Surgical removal—usually performed by a plastic surgeon—is occasionally necessary for cosmetic reasons. This is particularly so when NS covers a portion of the face, or when the cosmetic implications of having a hairless plaque in the scalp are sufficiently distressing.

This patient and her parents were educated about the nature of the diagnosis and apprised of their options.

Editor's note: For a similar presentation with a very different diagnosis, see the March 2015 DermaDiagnosis case (http://bit.ly/1ye69Ym).

A “bald spot” is the chief complaint of a 12-year-old girl brought for evaluation by her mother. The lesion in her left parietal scalp has been there since birth, slowly growing but producing no symptoms. Although the child’s primary care provider has reassured the family that the “birthmark” is benign, they remain concerned. Furthermore, the patient has become increasingly distressed by the hairlessness. The child is otherwise healthy. There is no history of excessive sun exposure. The lesion is a roughly oval, uniformly pink, hairless 3.6-cm plaque with a faintly mammillated surface and well-defined margins. It is only visible when the surrounding hair is parted sufficiently to reveal it. Examination of the rest of the patient’s skin is unremarkable.

As Problem Spreads, Man Seeks Help

ANSWER

The correct answer is Schamberg disease (choice “b”), a benign form of capillaritis; see Discussion for more information.

Scurvy patients can present with ecchymosis (among other findings that were missing in this case). But scurvy (choice “a”) is rare, and by the time the disease is evident, the patient is typically quite ill.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (choice “c”) can manifest as purpuric annular lesions. However, these would be unlikely to take the distributive pattern seen in this case, and they usually have an atrophic surface.

Thrombocytopenia (choice “d”) and other coagulopathies, although rightly considered, would probably manifest in other ways as well (ie, not just cutaneously).

Continue for the discussion >>

DISCUSSION