User login

The Value of Certainty in Diagnosis

ANSWER

For a number of reasons (discussed more fully below), the correct answer is to follow up with the pathologist (choice “c”); the biopsying provider, who is the only person to have seen the lesion, is responsible for resolving any discordance between the report and the clinical presentation/appearance.

Simply accepting the report as fact and notifying the patient of the result (choice “a”) is unacceptable. Removing more tissue from the base of the site (choice “b”) is not likely to provide any useful clinical information. Watching the site for change (choice “d”) ignores the possibility that the original lesion has already spread.

DISCUSSION

Skin tags, also known as fibroepithelioma or acrochorda, are extremely common, benign lesions encountered daily by almost all medical providers. Melanoma in tag form is decidedly unusual, but far from unknown. Around 80% of melanomas are essentially flat (macular), and about 10% are nodular. The rest, from a morphologic standpoint, are all over the map. They can be red, blue, and even white. Contrary to popular misconception, they rarely itch, and you probably wouldn’t want to depend on your dog to alert you to their presence.

My point? Although we conceive of melanomas as looking a certain way (a useful and necessary view), the reality is that their morphologic presentations are astonishingly diverse. They include pedunculated tags.

This means that unless we have a very good reason to do otherwise, we should send almost every skin lesion we remove for pathologic examination. Simple, small tags, warts, and the like can be safely discarded. But anything of substance, or anything that appears to be the least bit odd, must be submitted to pathology.

Furthermore, the pathology reports must be carefully read and the results connected to the particular lesion. This case illustrates that necessity nicely. With its black tip, this lesion was more than a little worrisome. When no mention was made of the pigmentary changes, a call to the pathologist was in order.

In this case, the pathologist was more than happy to order new and deeper cuts to be made in the specimen. Within two days, he issued a new report, which showed benign nevoid changes that explained the dark pigment and failed to show any atypia. Then, and only then, were we able to give the results to the patient.

This principle can be extrapolated to results from other types of tests. They are not to be accepted blindly by the ordering provider, who is in the unique position of having seen the patient.

ANSWER

For a number of reasons (discussed more fully below), the correct answer is to follow up with the pathologist (choice “c”); the biopsying provider, who is the only person to have seen the lesion, is responsible for resolving any discordance between the report and the clinical presentation/appearance.

Simply accepting the report as fact and notifying the patient of the result (choice “a”) is unacceptable. Removing more tissue from the base of the site (choice “b”) is not likely to provide any useful clinical information. Watching the site for change (choice “d”) ignores the possibility that the original lesion has already spread.

DISCUSSION

Skin tags, also known as fibroepithelioma or acrochorda, are extremely common, benign lesions encountered daily by almost all medical providers. Melanoma in tag form is decidedly unusual, but far from unknown. Around 80% of melanomas are essentially flat (macular), and about 10% are nodular. The rest, from a morphologic standpoint, are all over the map. They can be red, blue, and even white. Contrary to popular misconception, they rarely itch, and you probably wouldn’t want to depend on your dog to alert you to their presence.

My point? Although we conceive of melanomas as looking a certain way (a useful and necessary view), the reality is that their morphologic presentations are astonishingly diverse. They include pedunculated tags.

This means that unless we have a very good reason to do otherwise, we should send almost every skin lesion we remove for pathologic examination. Simple, small tags, warts, and the like can be safely discarded. But anything of substance, or anything that appears to be the least bit odd, must be submitted to pathology.

Furthermore, the pathology reports must be carefully read and the results connected to the particular lesion. This case illustrates that necessity nicely. With its black tip, this lesion was more than a little worrisome. When no mention was made of the pigmentary changes, a call to the pathologist was in order.

In this case, the pathologist was more than happy to order new and deeper cuts to be made in the specimen. Within two days, he issued a new report, which showed benign nevoid changes that explained the dark pigment and failed to show any atypia. Then, and only then, were we able to give the results to the patient.

This principle can be extrapolated to results from other types of tests. They are not to be accepted blindly by the ordering provider, who is in the unique position of having seen the patient.

ANSWER

For a number of reasons (discussed more fully below), the correct answer is to follow up with the pathologist (choice “c”); the biopsying provider, who is the only person to have seen the lesion, is responsible for resolving any discordance between the report and the clinical presentation/appearance.

Simply accepting the report as fact and notifying the patient of the result (choice “a”) is unacceptable. Removing more tissue from the base of the site (choice “b”) is not likely to provide any useful clinical information. Watching the site for change (choice “d”) ignores the possibility that the original lesion has already spread.

DISCUSSION

Skin tags, also known as fibroepithelioma or acrochorda, are extremely common, benign lesions encountered daily by almost all medical providers. Melanoma in tag form is decidedly unusual, but far from unknown. Around 80% of melanomas are essentially flat (macular), and about 10% are nodular. The rest, from a morphologic standpoint, are all over the map. They can be red, blue, and even white. Contrary to popular misconception, they rarely itch, and you probably wouldn’t want to depend on your dog to alert you to their presence.

My point? Although we conceive of melanomas as looking a certain way (a useful and necessary view), the reality is that their morphologic presentations are astonishingly diverse. They include pedunculated tags.

This means that unless we have a very good reason to do otherwise, we should send almost every skin lesion we remove for pathologic examination. Simple, small tags, warts, and the like can be safely discarded. But anything of substance, or anything that appears to be the least bit odd, must be submitted to pathology.

Furthermore, the pathology reports must be carefully read and the results connected to the particular lesion. This case illustrates that necessity nicely. With its black tip, this lesion was more than a little worrisome. When no mention was made of the pigmentary changes, a call to the pathologist was in order.

In this case, the pathologist was more than happy to order new and deeper cuts to be made in the specimen. Within two days, he issued a new report, which showed benign nevoid changes that explained the dark pigment and failed to show any atypia. Then, and only then, were we able to give the results to the patient.

This principle can be extrapolated to results from other types of tests. They are not to be accepted blindly by the ordering provider, who is in the unique position of having seen the patient.

A 48-year-old woman self-refers to dermatology for evaluation of several relatively minor skin problems. One of them is a taglike lesion on the skin of her low back. Present for years, it has begun to bother her a bit; it rubs against her clothes and is occasionally traumatized enough to bleed. The patient isn’t worried about it but does want it removed. Her history is unremarkable, with no personal or family history of skin cancer. She is fair and tolerates the sun poorly, but for that reason she has limited her sun exposure throughout her life. The lesion is a 5 x 6–mm taglike nodule located in the midline of her low back. At first glance, it appears to be traumatized. But on closer inspection, the distal half of the lesion is simply black, with indistinct margins. On palpation, the lesion is firmer than most tags but nontender. A few drops of lidocaine with epinephrine are injected into the base of the lesion, which is then saucerized. Minor bleeding is easily controlled by electrocautery, and the lesion is submitted to pathology. The resultant report shows a simple benign tag. No explanation for the darker portion of the lesion is given.

Relatively Asymptomatic, but Still Problematic

ANSWER

The correct answer is seborrheic dermatitis (choice “d”), a common cause of penile rashes that typically manifests initially as chronic dandruff or in some other form on the head or neck.

Herpes simplex (choice “a”) is certainly common, but it likely would have presented with grouped vesicles on an erythematous base. Furthermore, each episode would have been limited to about two weeks, and the eruption would have produced noticeable symptoms and responded to the valacyclovir.

Yeast infection (choice “b”), while often diagnosed, is in reality unusual, especially in the circumcised and otherwise healthy male. Nystatin, although far from the ideal treatment, should have had some effect.

Fixed drug eruption (FDE; choice “c”) could have been a suspect, had there been a drug to blame. FDE usually presents as a brownish red, shiny round macule that appears and reappears in the same area with repeated exposure to the same drug. The penile shaft is a favorite area for it. Drugs known to trigger FDE include NSAIDs, sulfa, tetracycline, penicillin, pseudoephedrine, and aspirin.

DISCUSSION

Seborrheic dermatitis (SD), also known as seborrhea, is an extremely common chronic papulosquamous disorder patterned on the sebum-rich areas of the scalp, face, and trunk. Although not directly caused by the highly lipophilic commensal yeast Malassezia furfur, it does appear to be related to increases in the number of those organisms, as well as to immunologic abnormalities and increased production of sebum. It can range from a mild scaly rash to whole-body erythroderma and can affect an astonishing range of areas, including the genitals.

SD almost always manifests with dandruff (or “cradle cap” in the infant), followed by faint scaling in and around the ears or on the face (eg, nasolabial folds, brows, and glabella), mid chest, axillae, periumbilical region, and genitals. Below the head and neck, SD often mystifies the nondermatology provider, who tends to call it “fungal infection” or, when it’s seen in moist intertriginous skin, “yeast infection.”

SD, especially in this case, represents the perfect example of the need to “look elsewhere” for clues when confronted with a mysterious rash. Patients can certainly have more than one dermatologic diagnosis at a time, but a single explanation is considerably more likely and should therefore be sought. In this case, corroboration for the diagnosis of SD was readily found by looking for it in its known locations.

SD can take on different looks, including a distinctly annular morphology, especially in patients with darker skin. It can occasionally be severe in patients with Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, or a history of stroke. This case mirrors my experience in that I see increased stress as a major precipitating factor in the worsening of pre-existing SD.

In addition to the items already mentioned, the differential for penile rashes includes lichen planus. However, the lesions of lichen planus tend to have a distinctly purple appearance and well-defined margins, and on the penis, they tend to spill over onto the penile corona and glans.

TREATMENT/PROGNOSIS

In this case, treatment comprised a combination of oxiconazole lotion and 2.5% hydrocortisone cream. Many other combinations have been used successfully, including pimecrolimus or tacrolimus combined with ketoconazole cream.

Whatever is used, a cure will not be forthcoming, since the condition is almost always chronic. The main value of an accurate diagnosis in such a case lies in easing the patient’s mind regarding the terrible diseases he doesn’t have.

ANSWER

The correct answer is seborrheic dermatitis (choice “d”), a common cause of penile rashes that typically manifests initially as chronic dandruff or in some other form on the head or neck.

Herpes simplex (choice “a”) is certainly common, but it likely would have presented with grouped vesicles on an erythematous base. Furthermore, each episode would have been limited to about two weeks, and the eruption would have produced noticeable symptoms and responded to the valacyclovir.

Yeast infection (choice “b”), while often diagnosed, is in reality unusual, especially in the circumcised and otherwise healthy male. Nystatin, although far from the ideal treatment, should have had some effect.

Fixed drug eruption (FDE; choice “c”) could have been a suspect, had there been a drug to blame. FDE usually presents as a brownish red, shiny round macule that appears and reappears in the same area with repeated exposure to the same drug. The penile shaft is a favorite area for it. Drugs known to trigger FDE include NSAIDs, sulfa, tetracycline, penicillin, pseudoephedrine, and aspirin.

DISCUSSION

Seborrheic dermatitis (SD), also known as seborrhea, is an extremely common chronic papulosquamous disorder patterned on the sebum-rich areas of the scalp, face, and trunk. Although not directly caused by the highly lipophilic commensal yeast Malassezia furfur, it does appear to be related to increases in the number of those organisms, as well as to immunologic abnormalities and increased production of sebum. It can range from a mild scaly rash to whole-body erythroderma and can affect an astonishing range of areas, including the genitals.

SD almost always manifests with dandruff (or “cradle cap” in the infant), followed by faint scaling in and around the ears or on the face (eg, nasolabial folds, brows, and glabella), mid chest, axillae, periumbilical region, and genitals. Below the head and neck, SD often mystifies the nondermatology provider, who tends to call it “fungal infection” or, when it’s seen in moist intertriginous skin, “yeast infection.”

SD, especially in this case, represents the perfect example of the need to “look elsewhere” for clues when confronted with a mysterious rash. Patients can certainly have more than one dermatologic diagnosis at a time, but a single explanation is considerably more likely and should therefore be sought. In this case, corroboration for the diagnosis of SD was readily found by looking for it in its known locations.

SD can take on different looks, including a distinctly annular morphology, especially in patients with darker skin. It can occasionally be severe in patients with Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, or a history of stroke. This case mirrors my experience in that I see increased stress as a major precipitating factor in the worsening of pre-existing SD.

In addition to the items already mentioned, the differential for penile rashes includes lichen planus. However, the lesions of lichen planus tend to have a distinctly purple appearance and well-defined margins, and on the penis, they tend to spill over onto the penile corona and glans.

TREATMENT/PROGNOSIS

In this case, treatment comprised a combination of oxiconazole lotion and 2.5% hydrocortisone cream. Many other combinations have been used successfully, including pimecrolimus or tacrolimus combined with ketoconazole cream.

Whatever is used, a cure will not be forthcoming, since the condition is almost always chronic. The main value of an accurate diagnosis in such a case lies in easing the patient’s mind regarding the terrible diseases he doesn’t have.

ANSWER

The correct answer is seborrheic dermatitis (choice “d”), a common cause of penile rashes that typically manifests initially as chronic dandruff or in some other form on the head or neck.

Herpes simplex (choice “a”) is certainly common, but it likely would have presented with grouped vesicles on an erythematous base. Furthermore, each episode would have been limited to about two weeks, and the eruption would have produced noticeable symptoms and responded to the valacyclovir.

Yeast infection (choice “b”), while often diagnosed, is in reality unusual, especially in the circumcised and otherwise healthy male. Nystatin, although far from the ideal treatment, should have had some effect.

Fixed drug eruption (FDE; choice “c”) could have been a suspect, had there been a drug to blame. FDE usually presents as a brownish red, shiny round macule that appears and reappears in the same area with repeated exposure to the same drug. The penile shaft is a favorite area for it. Drugs known to trigger FDE include NSAIDs, sulfa, tetracycline, penicillin, pseudoephedrine, and aspirin.

DISCUSSION

Seborrheic dermatitis (SD), also known as seborrhea, is an extremely common chronic papulosquamous disorder patterned on the sebum-rich areas of the scalp, face, and trunk. Although not directly caused by the highly lipophilic commensal yeast Malassezia furfur, it does appear to be related to increases in the number of those organisms, as well as to immunologic abnormalities and increased production of sebum. It can range from a mild scaly rash to whole-body erythroderma and can affect an astonishing range of areas, including the genitals.

SD almost always manifests with dandruff (or “cradle cap” in the infant), followed by faint scaling in and around the ears or on the face (eg, nasolabial folds, brows, and glabella), mid chest, axillae, periumbilical region, and genitals. Below the head and neck, SD often mystifies the nondermatology provider, who tends to call it “fungal infection” or, when it’s seen in moist intertriginous skin, “yeast infection.”

SD, especially in this case, represents the perfect example of the need to “look elsewhere” for clues when confronted with a mysterious rash. Patients can certainly have more than one dermatologic diagnosis at a time, but a single explanation is considerably more likely and should therefore be sought. In this case, corroboration for the diagnosis of SD was readily found by looking for it in its known locations.

SD can take on different looks, including a distinctly annular morphology, especially in patients with darker skin. It can occasionally be severe in patients with Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, or a history of stroke. This case mirrors my experience in that I see increased stress as a major precipitating factor in the worsening of pre-existing SD.

In addition to the items already mentioned, the differential for penile rashes includes lichen planus. However, the lesions of lichen planus tend to have a distinctly purple appearance and well-defined margins, and on the penis, they tend to spill over onto the penile corona and glans.

TREATMENT/PROGNOSIS

In this case, treatment comprised a combination of oxiconazole lotion and 2.5% hydrocortisone cream. Many other combinations have been used successfully, including pimecrolimus or tacrolimus combined with ketoconazole cream.

Whatever is used, a cure will not be forthcoming, since the condition is almost always chronic. The main value of an accurate diagnosis in such a case lies in easing the patient’s mind regarding the terrible diseases he doesn’t have.

A 31-year-old man is referred to dermatology for evaluation of a penile rash that has repeatedly manifested and resolved over a period of months. Relatively asymptomatic, the eruption has persisted despite a two-week course of valacyclovir 500 mg bid, followed by a month-long course of topical nystatin cream tid. The patient says he has been in otherwise good health. However, he reports being under a great deal of stress, as his job and his marriage ended within the space of a few weeks. He denies any sexual exposure outside his marriage. Other than those already mentioned, the patient has taken no medications, prescription or OTC. The problem area is obvious: a bright pink papulosquamous patch on the distal right shaft of his circumcised penis. This round lesion, which measures more than 3 cm in diameter, has a shiny appearance and slightly irregular margins. No other areas of involvement are noted in the genital area. However, there is a similar scaly pink rash behind both of the patient’s ears, as well as patches of dandruff in the scalp, especially over and behind the ears. A similar rash is seen in the patient’s umbilicus and surrounding area.

These Old Lesions? She’s Had Them for Years …

ANSWER

The correct answer is disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP; choice “a”). This condition, caused by an inherited defect of the SART3 gene, is seen mostly on the sun-exposed skin of middle-aged women.

Stasis dermatitis (choice “b”) can cause a number of skin changes, but not the discrete annular lesions seen with DSAP.

Seborrheic keratoses (choice “c”) are common on the legs. However, they don’t display this same morphology.

Nummular eczema (choice “d”) presents with annular papulosquamous lesions (as opposed to the fixed lesions seen with DSAP), often on the legs and lower trunk, but without the thready circumferential scaly border.

Continue reading for Joe Monroe's discussion...

DISCUSSION

Leg skin is prey to an astonishing array of problems; many have to do with increased hydrostatic pressure (eg, venous stasis disease), with the almost complete lack of sebaceous glands (eg, nummular eczema), or with the simple fact of being “in harm’s way.” And there is no law that says a given patient can’t have more than one problem at a time, co-existing and serving to confuse the examiner. Such is the case with this patient.

Her concern about possible blood clots is misplaced but understandable. Deep vein thromboses would not present in multiples, would not be on the surface or scaly, and would almost certainly be painful.

The fixed nature of this patient’s scaly lesions is extremely significant—but only if you know about DSAP, which typically manifests in the third decade of life and slowly worsens. The lesions’ highly palpable and unique scaly border makes them hard to leave alone. This might not be a problem except for the warfarin, which makes otherwise minor trauma visible as purpuric macules. Chronic sun damage tends to accentuate them as well. The positive family history is nicely corroborative and quite common.

The brown macules on the patient’s legs are solar lentigines (sun-caused freckles), which many patients (and even younger providers) erroneously call “age spots.” When these individuals become “aged,” they’ll understand that there is no such thing as an age spot.

This patient could easily have had nummular eczema, but not for 30 years! Those lesions, treated or not, will come and go. But not DSAP, about which many questions remain: If they’re caused by sun exposure, why don’t we see them more often on the face and arms? And why don’t we see them on the sun-damaged skin of older men?

If needed, a biopsy could have been performed. It would have been confirmatory of the diagnosis and effectively would have ruled out the other items in the differential, including wart, squamous cell carcinoma, and actinic or seborrheic keratosis.

ANSWER

The correct answer is disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP; choice “a”). This condition, caused by an inherited defect of the SART3 gene, is seen mostly on the sun-exposed skin of middle-aged women.

Stasis dermatitis (choice “b”) can cause a number of skin changes, but not the discrete annular lesions seen with DSAP.

Seborrheic keratoses (choice “c”) are common on the legs. However, they don’t display this same morphology.

Nummular eczema (choice “d”) presents with annular papulosquamous lesions (as opposed to the fixed lesions seen with DSAP), often on the legs and lower trunk, but without the thready circumferential scaly border.

Continue reading for Joe Monroe's discussion...

DISCUSSION

Leg skin is prey to an astonishing array of problems; many have to do with increased hydrostatic pressure (eg, venous stasis disease), with the almost complete lack of sebaceous glands (eg, nummular eczema), or with the simple fact of being “in harm’s way.” And there is no law that says a given patient can’t have more than one problem at a time, co-existing and serving to confuse the examiner. Such is the case with this patient.

Her concern about possible blood clots is misplaced but understandable. Deep vein thromboses would not present in multiples, would not be on the surface or scaly, and would almost certainly be painful.

The fixed nature of this patient’s scaly lesions is extremely significant—but only if you know about DSAP, which typically manifests in the third decade of life and slowly worsens. The lesions’ highly palpable and unique scaly border makes them hard to leave alone. This might not be a problem except for the warfarin, which makes otherwise minor trauma visible as purpuric macules. Chronic sun damage tends to accentuate them as well. The positive family history is nicely corroborative and quite common.

The brown macules on the patient’s legs are solar lentigines (sun-caused freckles), which many patients (and even younger providers) erroneously call “age spots.” When these individuals become “aged,” they’ll understand that there is no such thing as an age spot.

This patient could easily have had nummular eczema, but not for 30 years! Those lesions, treated or not, will come and go. But not DSAP, about which many questions remain: If they’re caused by sun exposure, why don’t we see them more often on the face and arms? And why don’t we see them on the sun-damaged skin of older men?

If needed, a biopsy could have been performed. It would have been confirmatory of the diagnosis and effectively would have ruled out the other items in the differential, including wart, squamous cell carcinoma, and actinic or seborrheic keratosis.

ANSWER

The correct answer is disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP; choice “a”). This condition, caused by an inherited defect of the SART3 gene, is seen mostly on the sun-exposed skin of middle-aged women.

Stasis dermatitis (choice “b”) can cause a number of skin changes, but not the discrete annular lesions seen with DSAP.

Seborrheic keratoses (choice “c”) are common on the legs. However, they don’t display this same morphology.

Nummular eczema (choice “d”) presents with annular papulosquamous lesions (as opposed to the fixed lesions seen with DSAP), often on the legs and lower trunk, but without the thready circumferential scaly border.

Continue reading for Joe Monroe's discussion...

DISCUSSION

Leg skin is prey to an astonishing array of problems; many have to do with increased hydrostatic pressure (eg, venous stasis disease), with the almost complete lack of sebaceous glands (eg, nummular eczema), or with the simple fact of being “in harm’s way.” And there is no law that says a given patient can’t have more than one problem at a time, co-existing and serving to confuse the examiner. Such is the case with this patient.

Her concern about possible blood clots is misplaced but understandable. Deep vein thromboses would not present in multiples, would not be on the surface or scaly, and would almost certainly be painful.

The fixed nature of this patient’s scaly lesions is extremely significant—but only if you know about DSAP, which typically manifests in the third decade of life and slowly worsens. The lesions’ highly palpable and unique scaly border makes them hard to leave alone. This might not be a problem except for the warfarin, which makes otherwise minor trauma visible as purpuric macules. Chronic sun damage tends to accentuate them as well. The positive family history is nicely corroborative and quite common.

The brown macules on the patient’s legs are solar lentigines (sun-caused freckles), which many patients (and even younger providers) erroneously call “age spots.” When these individuals become “aged,” they’ll understand that there is no such thing as an age spot.

This patient could easily have had nummular eczema, but not for 30 years! Those lesions, treated or not, will come and go. But not DSAP, about which many questions remain: If they’re caused by sun exposure, why don’t we see them more often on the face and arms? And why don’t we see them on the sun-damaged skin of older men?

If needed, a biopsy could have been performed. It would have been confirmatory of the diagnosis and effectively would have ruled out the other items in the differential, including wart, squamous cell carcinoma, and actinic or seborrheic keratosis.

A 65-year-old woman is referred to dermatology with discoloration of her legs that started several weeks ago. Her family suggested it might be “blood clots,” although she has been taking warfarin since she was diagnosed with atrial fibrillation several months ago. Her dermatologic condition is basically asymptomatic, but the patient admits to scratching her legs, saying it’s “hard to leave them alone.” On further questioning, she reveals that she has had “rough places” on her legs for at least 20 years and volunteers that her sister had the same problem, which was diagnosed years ago as “fungal infection.” Both she and her sister spent a great deal of time in the sun as children, long before sunscreen was invented. The patient is otherwise fairly healthy. She takes medication for her lipids, as well as daily vitamins. Her atrial fibrillation is under control and requires no medications other than the warfarin. A great deal of focal discoloration is seen on both legs, circumferentially distributed from well below the knees to just above the ankles. Many of the lesions are brown macules, but more are purplish-red, annular, and scaly. On closer examination, these lesions—the ones the patient says she has had for decades—have a very fine, thready, scaly border that palpation reveals to be tough and adherent. They average about 2 cm in diameter. There are no such lesions noted elsewhere on the patient’s skin. There is, however, abundant evidence of excessive sun exposure, characterized by a multitude of solar lentigines, many fine wrinkles, and extremely thin arm skin.

Man Seeks Treatment for Periodic “Eruptions”

The correct answer is benign familial pemphigus (choice “b”). Also known as Hailey-Hailey disease, this is an unusual autosomally inherited blistering disease.

Benign familial pemphigus (BFP) is often mistaken for bacterial infection, such as pyoderma (choice “a”) or impetigo (choice “c”). Although it can become secondarily infected, its origins are entirely different.

Contact dermatitis (choice “d”) in its more severe forms can present in a similar manner. However, it would have shown entirely different changes (acute inflammation and spongiosis) on biopsy.

See next page for the discussion...

DISCUSSION

In 1939, two dermatologist-brothers in Georgia saw a patient with this previously unreported condition. They uncovered the family history and worked out the histologic basis, which they then described in the literature. They named the condition benign familial pemphigus, but it is now more commonly known as Hailey-Hailey disease in their honor.

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV), a serious blistering disease, was more common and far more feared at the time of the Hailey brothers’ discovery. Nearly 100% of PV patients died from the condition in that pre-steroid, pre-antibiotic era (most from secondary bacterial infection).

Fortunately, BFP is more benign, though it shares some features with PV. Both are said to be Nikolsky-positive, meaning the initial blisters can be extended with digital pressure. But BFP, unlike PV, does not involve deposition of immunoglobulins (IgA in the case of PV), nor is it accompanied by circulating auto-antibodies. BFP patients typically have no systemic symptoms, whereas in those with PV, the oral mucosae are often affected.

Herpes simplex virus, which was the primary care provider’s initial suspected diagnosis, can cause somewhat similar outbreaks, even in this area. However, it was effectively ruled out by the lack of response to treatment and by the biopsy results.

Although BFP is an inherited condition, it demonstrates variable penetrance, as in our case. It is rare enough that diagnosis is almost invariably delayed while other diagnoses are considered and treated. The actual “lesion” of BFP is still debated, but appears to involve the quality and quantity of desmosomes (microscopic structures that act as connecting fibers between layers of tissue) breaking down, often because of heat and friction, eventuating in blistering. This theory is bolstered by considerable research and by the fact that most cases present in intertriginous areas, such as the neck, axillae, and groin. Appearing episodically, it typically begins in the third to fourth decade of life, tending to diminish with age.

Biopsy is often necessary to confirm the diagnosis of BFP, with the sample best taken from perilesional skin to avoid separation of friable sample fragments. Additional specimens can be taken for special handling (Michel’s media) to detect immunoglobulins that might be seen in other blistering diseases.

See next page for treatment...

TREATMENT

BFP can be treated empirically with application of a soothing solution of aluminum acetate, or more specifically with topical corticosteroids (class III to IV) and topical antibiotics (eg, clindamycin 2% solution), plus/minus oral minocycline, which has potent anti-inflammatory as well as antimicrobial effects.

Difficult cases should be referred to dermatology, which has a number of treatments at its disposal. This includes diaminodiphenyl sulfone (dapsone), systemic glucocorticoids, methotrexate, systemic retinoids, and even local injection of botulinum toxin to decrease local hidrosis.

This patient is responding well to a regimen of oral minocycline 100 mg bid, topical clindamycin 2% bid application, and topical tacrolimus.

The correct answer is benign familial pemphigus (choice “b”). Also known as Hailey-Hailey disease, this is an unusual autosomally inherited blistering disease.

Benign familial pemphigus (BFP) is often mistaken for bacterial infection, such as pyoderma (choice “a”) or impetigo (choice “c”). Although it can become secondarily infected, its origins are entirely different.

Contact dermatitis (choice “d”) in its more severe forms can present in a similar manner. However, it would have shown entirely different changes (acute inflammation and spongiosis) on biopsy.

See next page for the discussion...

DISCUSSION

In 1939, two dermatologist-brothers in Georgia saw a patient with this previously unreported condition. They uncovered the family history and worked out the histologic basis, which they then described in the literature. They named the condition benign familial pemphigus, but it is now more commonly known as Hailey-Hailey disease in their honor.

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV), a serious blistering disease, was more common and far more feared at the time of the Hailey brothers’ discovery. Nearly 100% of PV patients died from the condition in that pre-steroid, pre-antibiotic era (most from secondary bacterial infection).

Fortunately, BFP is more benign, though it shares some features with PV. Both are said to be Nikolsky-positive, meaning the initial blisters can be extended with digital pressure. But BFP, unlike PV, does not involve deposition of immunoglobulins (IgA in the case of PV), nor is it accompanied by circulating auto-antibodies. BFP patients typically have no systemic symptoms, whereas in those with PV, the oral mucosae are often affected.

Herpes simplex virus, which was the primary care provider’s initial suspected diagnosis, can cause somewhat similar outbreaks, even in this area. However, it was effectively ruled out by the lack of response to treatment and by the biopsy results.

Although BFP is an inherited condition, it demonstrates variable penetrance, as in our case. It is rare enough that diagnosis is almost invariably delayed while other diagnoses are considered and treated. The actual “lesion” of BFP is still debated, but appears to involve the quality and quantity of desmosomes (microscopic structures that act as connecting fibers between layers of tissue) breaking down, often because of heat and friction, eventuating in blistering. This theory is bolstered by considerable research and by the fact that most cases present in intertriginous areas, such as the neck, axillae, and groin. Appearing episodically, it typically begins in the third to fourth decade of life, tending to diminish with age.

Biopsy is often necessary to confirm the diagnosis of BFP, with the sample best taken from perilesional skin to avoid separation of friable sample fragments. Additional specimens can be taken for special handling (Michel’s media) to detect immunoglobulins that might be seen in other blistering diseases.

See next page for treatment...

TREATMENT

BFP can be treated empirically with application of a soothing solution of aluminum acetate, or more specifically with topical corticosteroids (class III to IV) and topical antibiotics (eg, clindamycin 2% solution), plus/minus oral minocycline, which has potent anti-inflammatory as well as antimicrobial effects.

Difficult cases should be referred to dermatology, which has a number of treatments at its disposal. This includes diaminodiphenyl sulfone (dapsone), systemic glucocorticoids, methotrexate, systemic retinoids, and even local injection of botulinum toxin to decrease local hidrosis.

This patient is responding well to a regimen of oral minocycline 100 mg bid, topical clindamycin 2% bid application, and topical tacrolimus.

The correct answer is benign familial pemphigus (choice “b”). Also known as Hailey-Hailey disease, this is an unusual autosomally inherited blistering disease.

Benign familial pemphigus (BFP) is often mistaken for bacterial infection, such as pyoderma (choice “a”) or impetigo (choice “c”). Although it can become secondarily infected, its origins are entirely different.

Contact dermatitis (choice “d”) in its more severe forms can present in a similar manner. However, it would have shown entirely different changes (acute inflammation and spongiosis) on biopsy.

See next page for the discussion...

DISCUSSION

In 1939, two dermatologist-brothers in Georgia saw a patient with this previously unreported condition. They uncovered the family history and worked out the histologic basis, which they then described in the literature. They named the condition benign familial pemphigus, but it is now more commonly known as Hailey-Hailey disease in their honor.

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV), a serious blistering disease, was more common and far more feared at the time of the Hailey brothers’ discovery. Nearly 100% of PV patients died from the condition in that pre-steroid, pre-antibiotic era (most from secondary bacterial infection).

Fortunately, BFP is more benign, though it shares some features with PV. Both are said to be Nikolsky-positive, meaning the initial blisters can be extended with digital pressure. But BFP, unlike PV, does not involve deposition of immunoglobulins (IgA in the case of PV), nor is it accompanied by circulating auto-antibodies. BFP patients typically have no systemic symptoms, whereas in those with PV, the oral mucosae are often affected.

Herpes simplex virus, which was the primary care provider’s initial suspected diagnosis, can cause somewhat similar outbreaks, even in this area. However, it was effectively ruled out by the lack of response to treatment and by the biopsy results.

Although BFP is an inherited condition, it demonstrates variable penetrance, as in our case. It is rare enough that diagnosis is almost invariably delayed while other diagnoses are considered and treated. The actual “lesion” of BFP is still debated, but appears to involve the quality and quantity of desmosomes (microscopic structures that act as connecting fibers between layers of tissue) breaking down, often because of heat and friction, eventuating in blistering. This theory is bolstered by considerable research and by the fact that most cases present in intertriginous areas, such as the neck, axillae, and groin. Appearing episodically, it typically begins in the third to fourth decade of life, tending to diminish with age.

Biopsy is often necessary to confirm the diagnosis of BFP, with the sample best taken from perilesional skin to avoid separation of friable sample fragments. Additional specimens can be taken for special handling (Michel’s media) to detect immunoglobulins that might be seen in other blistering diseases.

See next page for treatment...

TREATMENT

BFP can be treated empirically with application of a soothing solution of aluminum acetate, or more specifically with topical corticosteroids (class III to IV) and topical antibiotics (eg, clindamycin 2% solution), plus/minus oral minocycline, which has potent anti-inflammatory as well as antimicrobial effects.

Difficult cases should be referred to dermatology, which has a number of treatments at its disposal. This includes diaminodiphenyl sulfone (dapsone), systemic glucocorticoids, methotrexate, systemic retinoids, and even local injection of botulinum toxin to decrease local hidrosis.

This patient is responding well to a regimen of oral minocycline 100 mg bid, topical clindamycin 2% bid application, and topical tacrolimus.

For three months, a 38-year-old man has been trying to resolve an “eruption” on his neck. The rash burns and itches, though only mildly, and produces clear fluid. His primary care provider initially prescribed acyclovir, then valacyclovir; neither helped. Subsequent courses of oral antibiotics (cephalexin 500 mg qid for three weeks, then ciprofloxacin 500 mg bid for two weeks) also had no beneficial effect. There is no family history of similar outbreaks. The patient, however, has had several of these eruptions—on the face as well as the neck—since his 20s. They typically last two to four weeks, then disappear completely for months or years. The eruptions tend to occur in the summer. He denies any history of cold sores and does not recall any premonitory symptoms prior to this eruption. He further denies any history of atopy or immunosuppression. His health is otherwise excellent, and he is taking no prescription medications. The denuded area measures about 8 x 4 cm, from his nuchal scalp down to the C6 area of the posterior neck. Discrete ruptured vesicles are seen on the periphery of the site. A layer of peeling skin, resembling wet toilet tissue, covers the partially denuded central portion, at the base of which is distinctly erythematous underlying raw tissue. There is no erythema surrounding the lesion, and no nodes are palpable in the area. A 4-mm punch biopsy is performed, with a sample taken from the periphery of the lesion and submitted for routine handling. It shows a hyperplastic epithelium, as well as intradermal and suprabasilar acantholysis extending focally into the spinous layer.

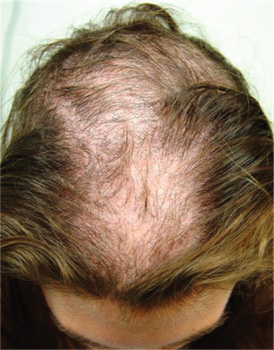

Hair Loss at a Very Young Age

ANSWER

The correct answer is trichotillomania (choice “c”). See Discussion for more information.

Alopecia mucinosa (choice “a”) is a rare cause of focal hair loss that can occur in children. However, it usually presents with papules or plaques, unlike the smooth skin surface seen here.

Alopecia areata (choice “b”), common in children, typically entails complete hair loss in a given area—or, as hair regrows, with hairs of equal length. The uneven hairs seen in trichotillomania help a great deal in distinguishing it from alopecia areata.

Traction alopecia (choice “d”) is focal hair loss caused by chronic tension related to hairstyling. Most common in African-American women, and typically affecting the frontal periphery of the scalp, it is an unlikely explanation for hair loss in a 10-year-old boy.

DISCUSSION

Trichotillomania (TT) means, literally, “hair-pulling madness.” But in reality, there’s little actual plucking of hairs in this common condition. Instead, patients habitually manipulate hair by twirling and tugging, which weakens the shafts and follicles and renders them more susceptible to everyday wear and tear. In some cases, individual hairs speed through their growth phases and others break off in mid-shaft. All of this contributes to the classic “uneven” look of TT.

Patients with TT tend to be in the 4-to-17 age range, and most have issues with unresolved anxiety that manifest in part with manipulation of the hair. Officially considered an impulse control disorder, TT in most cases belongs to the psychiatrist’s domain.

In this case, it was enormously helpful to have corroboration from the patient and his mother regarding his role in creating and perpetuating the problem. Had that not been the case—or in the event of other doubts as to the correct diagnosis—biopsy could have been performed to rule out most of the other items in the differential, particularly alopecia areata.

Interestingly enough, studies have shown that the more sharply defined the area of hair loss, the more likely the patient is to admit his/her role in its creation. However, as is often the case with scientific research, contradictory findings have also been made.

TREATMENT

Treatment of TT is problematic, since no medications have proven to be completely helpful. Psychiatrists use a combination of medication, cognitive behavioral therapy, and other behavior modifications that are designed to overcome the habitual component of the problem. Most cases of TT resolve on their own, but in severe cases that persist for years, permanent hair loss can result.

In this case, there was enough insight and motivation on the part of the patient and his family to stop the offending behavior and allow the hair to regrow.

ANSWER

The correct answer is trichotillomania (choice “c”). See Discussion for more information.

Alopecia mucinosa (choice “a”) is a rare cause of focal hair loss that can occur in children. However, it usually presents with papules or plaques, unlike the smooth skin surface seen here.

Alopecia areata (choice “b”), common in children, typically entails complete hair loss in a given area—or, as hair regrows, with hairs of equal length. The uneven hairs seen in trichotillomania help a great deal in distinguishing it from alopecia areata.

Traction alopecia (choice “d”) is focal hair loss caused by chronic tension related to hairstyling. Most common in African-American women, and typically affecting the frontal periphery of the scalp, it is an unlikely explanation for hair loss in a 10-year-old boy.

DISCUSSION

Trichotillomania (TT) means, literally, “hair-pulling madness.” But in reality, there’s little actual plucking of hairs in this common condition. Instead, patients habitually manipulate hair by twirling and tugging, which weakens the shafts and follicles and renders them more susceptible to everyday wear and tear. In some cases, individual hairs speed through their growth phases and others break off in mid-shaft. All of this contributes to the classic “uneven” look of TT.

Patients with TT tend to be in the 4-to-17 age range, and most have issues with unresolved anxiety that manifest in part with manipulation of the hair. Officially considered an impulse control disorder, TT in most cases belongs to the psychiatrist’s domain.

In this case, it was enormously helpful to have corroboration from the patient and his mother regarding his role in creating and perpetuating the problem. Had that not been the case—or in the event of other doubts as to the correct diagnosis—biopsy could have been performed to rule out most of the other items in the differential, particularly alopecia areata.

Interestingly enough, studies have shown that the more sharply defined the area of hair loss, the more likely the patient is to admit his/her role in its creation. However, as is often the case with scientific research, contradictory findings have also been made.

TREATMENT

Treatment of TT is problematic, since no medications have proven to be completely helpful. Psychiatrists use a combination of medication, cognitive behavioral therapy, and other behavior modifications that are designed to overcome the habitual component of the problem. Most cases of TT resolve on their own, but in severe cases that persist for years, permanent hair loss can result.

In this case, there was enough insight and motivation on the part of the patient and his family to stop the offending behavior and allow the hair to regrow.

ANSWER

The correct answer is trichotillomania (choice “c”). See Discussion for more information.

Alopecia mucinosa (choice “a”) is a rare cause of focal hair loss that can occur in children. However, it usually presents with papules or plaques, unlike the smooth skin surface seen here.

Alopecia areata (choice “b”), common in children, typically entails complete hair loss in a given area—or, as hair regrows, with hairs of equal length. The uneven hairs seen in trichotillomania help a great deal in distinguishing it from alopecia areata.

Traction alopecia (choice “d”) is focal hair loss caused by chronic tension related to hairstyling. Most common in African-American women, and typically affecting the frontal periphery of the scalp, it is an unlikely explanation for hair loss in a 10-year-old boy.

DISCUSSION

Trichotillomania (TT) means, literally, “hair-pulling madness.” But in reality, there’s little actual plucking of hairs in this common condition. Instead, patients habitually manipulate hair by twirling and tugging, which weakens the shafts and follicles and renders them more susceptible to everyday wear and tear. In some cases, individual hairs speed through their growth phases and others break off in mid-shaft. All of this contributes to the classic “uneven” look of TT.

Patients with TT tend to be in the 4-to-17 age range, and most have issues with unresolved anxiety that manifest in part with manipulation of the hair. Officially considered an impulse control disorder, TT in most cases belongs to the psychiatrist’s domain.

In this case, it was enormously helpful to have corroboration from the patient and his mother regarding his role in creating and perpetuating the problem. Had that not been the case—or in the event of other doubts as to the correct diagnosis—biopsy could have been performed to rule out most of the other items in the differential, particularly alopecia areata.

Interestingly enough, studies have shown that the more sharply defined the area of hair loss, the more likely the patient is to admit his/her role in its creation. However, as is often the case with scientific research, contradictory findings have also been made.

TREATMENT

Treatment of TT is problematic, since no medications have proven to be completely helpful. Psychiatrists use a combination of medication, cognitive behavioral therapy, and other behavior modifications that are designed to overcome the habitual component of the problem. Most cases of TT resolve on their own, but in severe cases that persist for years, permanent hair loss can result.

In this case, there was enough insight and motivation on the part of the patient and his family to stop the offending behavior and allow the hair to regrow.

A 10-year-old boy is referred to dermatology with a four-month history of hair loss. The affected area of the vertex is now large enough to alarm his mother, who accompanies him to his appointment. The child’s primary care provider had diagnosed alopecia areata and prescribed triamcinolone 0.1% solution. But after a month of twice-daily application, even more hair has been lost. There is no family history of alopecia areata or other autoimmune disease. The child is otherwise healthy, although he is being treated by a psychiatrist for attention deficit disorder and chronic anxiety (with two medications whose names are unknown). The patient denies any symptoms associated with his hair loss, and his mother denies any skin changes in the affected area. However, she emphasizes that she has seen her son manipulating the area with his hand on several occasions, despite her attempts to make him stop. When pressed, the patient finally admits that throughout the day he twirls and tugs on his hair—although he denies actually pulling out any. On inspection, an 11 x 8–cm oval area of distinct and sharply demarcated hair loss is noted in the vertex scalp. Hairs of different lengths are noted in the central portion of the site; some have obviously been broken off, while others are longer, with thin, tapering ends. There is no disruption (eg, scaling, redness, edema) in the surface of the scalp, but the whole area is darker (brown) than the surrounding, uninvolved scalp. No other areas of hair loss are noted in the scalp or face. No nodes are palpable in the neck.

Growing Lesion Impedes Finger Flexion

ANSWER

The correct answer is implantation cyst (choice “b”). This type of cyst is typically caused by trauma (eg, a puncture wound), and its contents are in stark contrast to those of ganglion cysts (choice “a”), which are thick and clear.

Warts (choice “c”) are essentially an epidermal process, not subcutaneous. They almost always disrupt normal skin lines, which often curve around the wart—a finding that was missing in this case.

Acquired digital fibrokeratomas (choice “d”) are benign solid tumors frequently seen on fingers. However, they are more epidermal than intradermal and demonstrate a diagnostic feature called an epidermal collarette (missing in this case).

DISCUSSION

Sometimes called implantation dermoid cysts, these sacs have a well-defined white cyst wall and cheesy, often odoriferous contents. Although common on hands and fingers, they can occur in almost any location and as a result of many types of trauma.

This includes surgical trauma, which effectively implants surface adnexal tissue (eg, the sebaceous apparatus) where it can continue to produce and accumulate its cheesy contents over time. Patients often forget the trauma that caused the cyst, but it is still worth inquiring into.

Merely emptying the sac can confirm the diagnosis; however, this almost always results in recurrence. Fortunately, implantation cysts are usually easily removed with minimal risk to hand function.

As with almost any tissue removed from the body, the specimen needs to be sent for pathologic examination. In addition to the differential items already noted, a number of rare or unusual conditions can present in a similar fashion, including eccrine carcinoma and a variety of sarcomas.

This patient recovered from his surgery without complication. Pathologic examination confirmed the benign nature of the lesion.

ANSWER

The correct answer is implantation cyst (choice “b”). This type of cyst is typically caused by trauma (eg, a puncture wound), and its contents are in stark contrast to those of ganglion cysts (choice “a”), which are thick and clear.

Warts (choice “c”) are essentially an epidermal process, not subcutaneous. They almost always disrupt normal skin lines, which often curve around the wart—a finding that was missing in this case.

Acquired digital fibrokeratomas (choice “d”) are benign solid tumors frequently seen on fingers. However, they are more epidermal than intradermal and demonstrate a diagnostic feature called an epidermal collarette (missing in this case).

DISCUSSION

Sometimes called implantation dermoid cysts, these sacs have a well-defined white cyst wall and cheesy, often odoriferous contents. Although common on hands and fingers, they can occur in almost any location and as a result of many types of trauma.

This includes surgical trauma, which effectively implants surface adnexal tissue (eg, the sebaceous apparatus) where it can continue to produce and accumulate its cheesy contents over time. Patients often forget the trauma that caused the cyst, but it is still worth inquiring into.

Merely emptying the sac can confirm the diagnosis; however, this almost always results in recurrence. Fortunately, implantation cysts are usually easily removed with minimal risk to hand function.

As with almost any tissue removed from the body, the specimen needs to be sent for pathologic examination. In addition to the differential items already noted, a number of rare or unusual conditions can present in a similar fashion, including eccrine carcinoma and a variety of sarcomas.

This patient recovered from his surgery without complication. Pathologic examination confirmed the benign nature of the lesion.

ANSWER

The correct answer is implantation cyst (choice “b”). This type of cyst is typically caused by trauma (eg, a puncture wound), and its contents are in stark contrast to those of ganglion cysts (choice “a”), which are thick and clear.

Warts (choice “c”) are essentially an epidermal process, not subcutaneous. They almost always disrupt normal skin lines, which often curve around the wart—a finding that was missing in this case.

Acquired digital fibrokeratomas (choice “d”) are benign solid tumors frequently seen on fingers. However, they are more epidermal than intradermal and demonstrate a diagnostic feature called an epidermal collarette (missing in this case).

DISCUSSION

Sometimes called implantation dermoid cysts, these sacs have a well-defined white cyst wall and cheesy, often odoriferous contents. Although common on hands and fingers, they can occur in almost any location and as a result of many types of trauma.

This includes surgical trauma, which effectively implants surface adnexal tissue (eg, the sebaceous apparatus) where it can continue to produce and accumulate its cheesy contents over time. Patients often forget the trauma that caused the cyst, but it is still worth inquiring into.

Merely emptying the sac can confirm the diagnosis; however, this almost always results in recurrence. Fortunately, implantation cysts are usually easily removed with minimal risk to hand function.

As with almost any tissue removed from the body, the specimen needs to be sent for pathologic examination. In addition to the differential items already noted, a number of rare or unusual conditions can present in a similar fashion, including eccrine carcinoma and a variety of sarcomas.

This patient recovered from his surgery without complication. Pathologic examination confirmed the benign nature of the lesion.

For several years, a 45-year-old man has had an asymptomatic lesion on the volar aspect of his fourth finger. The lesion is growing and increasingly “in the way.” That, coupled with the patient’s concern about cancer or other serious disease, leads him to request referral to dermatology. There is no history of similar lesions anywhere on his body. Additional questioning reveals that several months prior to the lesion’s manifestation, the patient sustained a puncture wound to the same finger. Initially, the affected area was only a millimeter or two in size. X-rays ordered by his primary care provider did not indicate any bony abnormality, nor did they shed any light on the lesion itself. An impressive 2.6 cm in diameter, the lesion is prominent in vertical elevation as well. Motor and sensory function are found to be intact, although the bulk of the lesion prohibits full flexion of the finger. The lesion is opaque to attempted transillumination. No surface changes are apparent in the overlying skin. Skin lines are intact and parallel. The lesion is quite firm but compressible. The decision is made to excise the lesion, employing a digital block and tourniquet. A football-shaped ellipse of skin with 50° angles on the ends is removed from the surface, revealing a glistening white, smooth mass that comes out intact, with very little blunt dissection. Motor function is again assessed and found to be intact. The large angles in the ends of the ellipse allow the wound edges to be pulled together with interrupted vertical mattress sutures and no leftover redundant skin. The lesion is submitted intact for pathologic examination.

A Purplish Rash on the Instep

ANSWER

The correct answer is lichen planus (choice “d”), an inflammatory condition marked by pathognomic histologic changes such as those described. Hardly on the tip of most primary care providers’ tongues, lichen planus is nonetheless quite commonly occuring.

Tinea pedis (choice “a”) certainly belongs in the differential, but it would be unusual in a woman of this age. The biopsy effectively ruled it out, as it did psoriasis (choice “b”) and contact dermatitis (choice “c”).

DISCUSSION

Lichen planus (LP) is the prototypical lichenoid interface dermatitis; an inflammatory infiltrate erases the normally well-defined dermoepidermal junction, replacing it with a jagged “sawtooth” band of lymphocytes. In the process, the cells it kills off (keratinocytes) collect at this interface and are incorporated as necrotic keratinocytes into the papillary dermis.

Classically, the recognition of LP is taught with “The Ps.” LP is said to be:

• Papular

• Planar

• Purple

• Polygonal

• Pruritic

• Plaquish

• Penile

• Puzzling

The word “puzzling” may sound nebulous, but it is actually quite useful for dermatology providers. It comes into play whenever a condition stumps us—as in, “What in the world is this?” This puzzlement causes us to at least consider LP.

LP is often papular, and these papules often have flat (planar) tops. The purple color is more striking in lighter-skinned patients. (Almost all inflammatory conditions are more difficult to diagnose in those with darker skin.) More typically, LP lesions are multi-angular or polygonal, often plaquish, and almost invariably pruritic.

LP is common on the legs and/or trunk, favoring the sacral area. It can affect the scalp (being in the differential for hair loss), can cause nail dystrophy, and is relatively common in the mouth, where it presents as a lacy, reticular, slightly erosive process, usually affecting the buccal mucosae. It may be found on the penis, where it is usually confined to the distal shaft and proximal coronal areas.

Like many otherwise benign conditions, LP can present with bullae. In anterior tibial areas, especially on darker-skinned persons, it can be remarkably hypertrophic.

The cause is usually unknown, although certain drugs—especially the antimalarials, gold salts, and penicillamine—have been known to cause LP-like eruptions. It’s been my observation that flares of LP are prompted by stress (certainly present in this patient’s case). LP may have a connection to hepatitis, although no convincing connection has been established.

TREATMENT

This patient’s condition was treated with topical class I corticosteroid ointment (halobetasol). For her, having a certain diagnosis was almost as important as successful treatment.

ANSWER

The correct answer is lichen planus (choice “d”), an inflammatory condition marked by pathognomic histologic changes such as those described. Hardly on the tip of most primary care providers’ tongues, lichen planus is nonetheless quite commonly occuring.

Tinea pedis (choice “a”) certainly belongs in the differential, but it would be unusual in a woman of this age. The biopsy effectively ruled it out, as it did psoriasis (choice “b”) and contact dermatitis (choice “c”).

DISCUSSION

Lichen planus (LP) is the prototypical lichenoid interface dermatitis; an inflammatory infiltrate erases the normally well-defined dermoepidermal junction, replacing it with a jagged “sawtooth” band of lymphocytes. In the process, the cells it kills off (keratinocytes) collect at this interface and are incorporated as necrotic keratinocytes into the papillary dermis.

Classically, the recognition of LP is taught with “The Ps.” LP is said to be:

• Papular

• Planar

• Purple

• Polygonal

• Pruritic

• Plaquish

• Penile

• Puzzling

The word “puzzling” may sound nebulous, but it is actually quite useful for dermatology providers. It comes into play whenever a condition stumps us—as in, “What in the world is this?” This puzzlement causes us to at least consider LP.

LP is often papular, and these papules often have flat (planar) tops. The purple color is more striking in lighter-skinned patients. (Almost all inflammatory conditions are more difficult to diagnose in those with darker skin.) More typically, LP lesions are multi-angular or polygonal, often plaquish, and almost invariably pruritic.

LP is common on the legs and/or trunk, favoring the sacral area. It can affect the scalp (being in the differential for hair loss), can cause nail dystrophy, and is relatively common in the mouth, where it presents as a lacy, reticular, slightly erosive process, usually affecting the buccal mucosae. It may be found on the penis, where it is usually confined to the distal shaft and proximal coronal areas.

Like many otherwise benign conditions, LP can present with bullae. In anterior tibial areas, especially on darker-skinned persons, it can be remarkably hypertrophic.

The cause is usually unknown, although certain drugs—especially the antimalarials, gold salts, and penicillamine—have been known to cause LP-like eruptions. It’s been my observation that flares of LP are prompted by stress (certainly present in this patient’s case). LP may have a connection to hepatitis, although no convincing connection has been established.

TREATMENT

This patient’s condition was treated with topical class I corticosteroid ointment (halobetasol). For her, having a certain diagnosis was almost as important as successful treatment.

ANSWER

The correct answer is lichen planus (choice “d”), an inflammatory condition marked by pathognomic histologic changes such as those described. Hardly on the tip of most primary care providers’ tongues, lichen planus is nonetheless quite commonly occuring.

Tinea pedis (choice “a”) certainly belongs in the differential, but it would be unusual in a woman of this age. The biopsy effectively ruled it out, as it did psoriasis (choice “b”) and contact dermatitis (choice “c”).

DISCUSSION

Lichen planus (LP) is the prototypical lichenoid interface dermatitis; an inflammatory infiltrate erases the normally well-defined dermoepidermal junction, replacing it with a jagged “sawtooth” band of lymphocytes. In the process, the cells it kills off (keratinocytes) collect at this interface and are incorporated as necrotic keratinocytes into the papillary dermis.

Classically, the recognition of LP is taught with “The Ps.” LP is said to be:

• Papular

• Planar

• Purple

• Polygonal

• Pruritic

• Plaquish

• Penile

• Puzzling

The word “puzzling” may sound nebulous, but it is actually quite useful for dermatology providers. It comes into play whenever a condition stumps us—as in, “What in the world is this?” This puzzlement causes us to at least consider LP.

LP is often papular, and these papules often have flat (planar) tops. The purple color is more striking in lighter-skinned patients. (Almost all inflammatory conditions are more difficult to diagnose in those with darker skin.) More typically, LP lesions are multi-angular or polygonal, often plaquish, and almost invariably pruritic.

LP is common on the legs and/or trunk, favoring the sacral area. It can affect the scalp (being in the differential for hair loss), can cause nail dystrophy, and is relatively common in the mouth, where it presents as a lacy, reticular, slightly erosive process, usually affecting the buccal mucosae. It may be found on the penis, where it is usually confined to the distal shaft and proximal coronal areas.

Like many otherwise benign conditions, LP can present with bullae. In anterior tibial areas, especially on darker-skinned persons, it can be remarkably hypertrophic.

The cause is usually unknown, although certain drugs—especially the antimalarials, gold salts, and penicillamine—have been known to cause LP-like eruptions. It’s been my observation that flares of LP are prompted by stress (certainly present in this patient’s case). LP may have a connection to hepatitis, although no convincing connection has been established.

TREATMENT

This patient’s condition was treated with topical class I corticosteroid ointment (halobetasol). For her, having a certain diagnosis was almost as important as successful treatment.

Several months ago, an itchy rash appeared on the foot of this 61-year-old African-American woman. She tried using a variety of OTC and prescription products, including tolnaftate cream, hydrocortisone 1% cream, and triamcinolone cream, but the rash persisted. She reports that the triamcinolone cream did relieve the itching for a few minutes after application, but the symptoms always returned. The rash has gradually grown. The patient, a retired schoolteacher, denies any other skin problems. She does have several relatively minor health problems, including hypertension (well controlled with metoprolol) and mild reactive airway disease (related to a 20-year history of smoking). The rash manifested around the time she was forced to retire in an unforeseen downsizing effort by her school district. As a result, she lost her health care coverage and could not afford private insurance for herself and her husband (neither of whom are old enough to qualify for Medicare). The rash, which covers a roughly 12 × 8–cm area, begins on her left instep and spills onto the lower ankle. It is quite dark, as would be expected in a person with type V skin, but there is a slightly purplish tinge to it. The surface of the affected area is a bit shiny and atrophic, and the margins are well defined and annular. There is almost no scaling, and the rest of the skin on her feet and legs is well within normal limits. A 4-mm punch biopsy is performed on the lesion. The pathology report shows obliteration of the dermoepidermal junction by a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis, associated with vacuolar changes and the accumulation of necrotic keratinocytes in the basal layer.

Lifelong Problem Has Caused Embarrassment

ANSWER

The correct answer is discoid lupus (choice “d”); see discussion for further details.

Sarcoidosis (choice “a”) is a worthy item in this differential, since it can be chronic, often affects the face (especially in African-Americans), and frequently defies ready diagnosis. But the biopsy was totally inconsistent with this diagnosis; in a case of sarcoidosis, it instead would have shown noncaseating granulomas, which are characteristic of the condition.

Lichen planus (choice “b”) is likewise worth consideration, since it can present in a similar fashion (although the chronicity of this patient’s lesions would have been atypical). Moreover, lichen planus is almost invariably symptomatic (itch). Biopsy would have shown obliteration of the dermoepidermal junction by an intense lymphocytic infiltrate—findings totally at odds with what was seen.

Polymorphous light eruption (PMLE; choice “c”) is the name given to a variety of photosensitivities that, true to the term polymorphous (or polymorphic), can present in numerous ways—although the lesions on any given patient tend to be monomorphic. These can take the form of vesicles, papules, and even erythema multiforme–like targetoid lesions, most commonly (as expected) on sun-exposed skin. Curiously, though, PMLE seldom affects the face or hands. It can manifest early in a patient’s life, but it would have been “seasonal,” disappearing in winter, and would have revealed a totally different picture on biopsy.

DISCUSSION

This patient suffered needlessly for more than half his life for lack of one simple thing: a correct diagnosis. Truth be known, the patient and his family probably bear some responsibility—but at some point, one of his many providers should have either obtained a punch biopsy or sent him to someone who would do so.

Instead, as is often the case, the emphasis was on treatment: trying one thing after another. The lack of success with these endeavors speaks loudly for the need for a definitive diagnosis. This could only be established one way: with a biopsy.

All the items mentioned in the above differential were legitimately considered. So was the possibility of infection, especially atypical types such as mycobacterial, deep fungal, or those involving other unusual organisms (eg, Nocardia, Actinomycetes). As in this case, tissue can be collected and submitted for culture, but the usual formalin preservative will kill any organism, necessitating prompt processing in saline.

Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) can be purely cutaneous (as seen here) or can be a manifestation of more serious systemic lupus. In any case, it is an autoimmune process, made worse by the sun, and can be chronic (though this case is exceptional in that regard).

This patient’s chance of developing systemic lupus erythematosus is slight, at most, since his antinuclear antibody test was negative. But his lifetime risk for another autoimmune disease is high.

TREATMENT

DLE is usually treated successfully with a combination of sun avoidance and a course of oral hydroxychloroquine (200 mg QD to bid, depending on the patient’s body habitus and the severity of the disease). Given the advanced state of this patient’s condition, he received the more frequent dosage, which should yield positive results. However, he will likely be on this regimen for some time.

ANSWER

The correct answer is discoid lupus (choice “d”); see discussion for further details.

Sarcoidosis (choice “a”) is a worthy item in this differential, since it can be chronic, often affects the face (especially in African-Americans), and frequently defies ready diagnosis. But the biopsy was totally inconsistent with this diagnosis; in a case of sarcoidosis, it instead would have shown noncaseating granulomas, which are characteristic of the condition.

Lichen planus (choice “b”) is likewise worth consideration, since it can present in a similar fashion (although the chronicity of this patient’s lesions would have been atypical). Moreover, lichen planus is almost invariably symptomatic (itch). Biopsy would have shown obliteration of the dermoepidermal junction by an intense lymphocytic infiltrate—findings totally at odds with what was seen.

Polymorphous light eruption (PMLE; choice “c”) is the name given to a variety of photosensitivities that, true to the term polymorphous (or polymorphic), can present in numerous ways—although the lesions on any given patient tend to be monomorphic. These can take the form of vesicles, papules, and even erythema multiforme–like targetoid lesions, most commonly (as expected) on sun-exposed skin. Curiously, though, PMLE seldom affects the face or hands. It can manifest early in a patient’s life, but it would have been “seasonal,” disappearing in winter, and would have revealed a totally different picture on biopsy.

DISCUSSION

This patient suffered needlessly for more than half his life for lack of one simple thing: a correct diagnosis. Truth be known, the patient and his family probably bear some responsibility—but at some point, one of his many providers should have either obtained a punch biopsy or sent him to someone who would do so.

Instead, as is often the case, the emphasis was on treatment: trying one thing after another. The lack of success with these endeavors speaks loudly for the need for a definitive diagnosis. This could only be established one way: with a biopsy.

All the items mentioned in the above differential were legitimately considered. So was the possibility of infection, especially atypical types such as mycobacterial, deep fungal, or those involving other unusual organisms (eg, Nocardia, Actinomycetes). As in this case, tissue can be collected and submitted for culture, but the usual formalin preservative will kill any organism, necessitating prompt processing in saline.

Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) can be purely cutaneous (as seen here) or can be a manifestation of more serious systemic lupus. In any case, it is an autoimmune process, made worse by the sun, and can be chronic (though this case is exceptional in that regard).

This patient’s chance of developing systemic lupus erythematosus is slight, at most, since his antinuclear antibody test was negative. But his lifetime risk for another autoimmune disease is high.

TREATMENT

DLE is usually treated successfully with a combination of sun avoidance and a course of oral hydroxychloroquine (200 mg QD to bid, depending on the patient’s body habitus and the severity of the disease). Given the advanced state of this patient’s condition, he received the more frequent dosage, which should yield positive results. However, he will likely be on this regimen for some time.

ANSWER

The correct answer is discoid lupus (choice “d”); see discussion for further details.

Sarcoidosis (choice “a”) is a worthy item in this differential, since it can be chronic, often affects the face (especially in African-Americans), and frequently defies ready diagnosis. But the biopsy was totally inconsistent with this diagnosis; in a case of sarcoidosis, it instead would have shown noncaseating granulomas, which are characteristic of the condition.

Lichen planus (choice “b”) is likewise worth consideration, since it can present in a similar fashion (although the chronicity of this patient’s lesions would have been atypical). Moreover, lichen planus is almost invariably symptomatic (itch). Biopsy would have shown obliteration of the dermoepidermal junction by an intense lymphocytic infiltrate—findings totally at odds with what was seen.