User login

This Is No Measly Rash

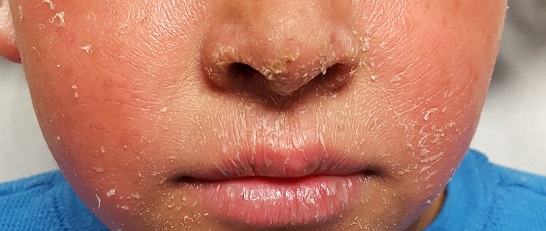

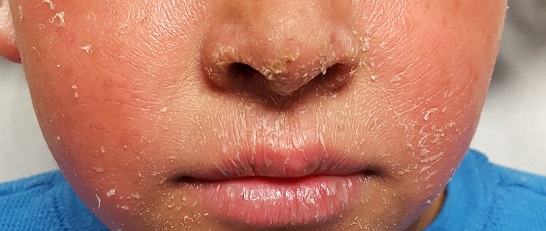

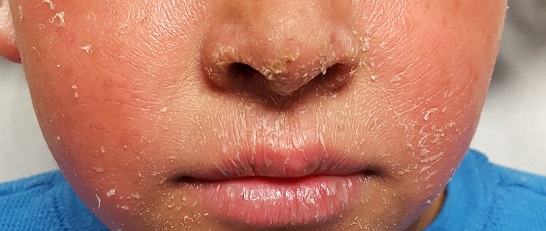

A 7-year-old girl is urgently referred to dermatology for a rash of several weeks’ duration. It is the rash itself, rather than any related symptoms, that frightens the family; the possibility of measles (raised by their primary care provider) compounded their concern. Antifungal cream (clotrimazole) has been of no help.

Physically, the child feels fine, without fever or malaise. But further questioning reveals that she was diagnosed with and treated for strep throat “about a month before” the rash developed.

The child was recently adopted by her aunt and uncle after her parents were killed in an automobile accident. This, understandably, has caused her to fall behind in school. She has no pets, no siblings, and no family history of skin disease.

EXAMINATION

Numerous discrete, round papules and plaques are distributed very evenly on the trunk. They are uniformly scaly and pink, measuring 2 to 3 cm each. In addition, several areas of thick, white, tenacious scaling are seen in the scalp.

The patient’s elbows, knees, and nails are free of any notable change.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is a typical case of guttate psoriasis, which is genetic in predisposition but triggered by strep in the susceptible patient. It’s tempting to partially attribute this case to the child’s high stress level, but this is purely speculative.

Psoriasis affects about 7 million people in the US—more than 150 million worldwide—in a variety of forms. The guttate morphology is seen primarily in children, with plaques that favor extensor surfaces of the arms, trunk, and legs. Biopsy was not needed in this case; if performed, it would have shown characteristic changes (eg, parakeratosis, fusing of rete ridges).

These changes occur because psoriasis, an autoimmune disease, targets keratinocytes—cells that regenerate over a 28-day period to replace the outer layer of skin as it flakes off. With psoriasis, this process is accelerated; keratinocytes move and slough off within a week, creating scaly, inflamed lesions.

Long-term follow-up is needed to monitor the patient’s overall health, because psoriasis increases comorbidity of conditions such as coronary vessel disease, diabetes, stroke, and cancer. In patients with any form of psoriasis, there is the potential for psoriatic arthropathy, a destructive, crippling form of arthropathy that affects up to 25% of all patients. And in a third of guttate psoriasis cases, the condition evolves into permanent plaque psoriasis. For this reason, the guttate variety must be treated aggressively with a combination of phototherapy and topical steroids, adequate treatment of any residual strep, and, in adults, the occasional addition of methotrexate.

Regarding the family’s concern, measles does not involve scaly papules and plaques and would likely cause other constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, myalgia). The other item in the differential, tinea corporis, involves lesions that are not as uniformly scaly, numerous, or evenly spaced. And with tinea, scaling typically occurs on the peripheral leading edge of the lesion.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Guttate psoriasis is more common in children than in adults and is often triggered by strep infection, though stress has also been implicated as a trigger.

- In about a third of all cases, this type evolves into permanent plaque psoriasis. All patients with psoriasis are at risk for psoriatic arthropathy (25% of patients).

- Measles does not involve scaly papules and plaques and would likely cause constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, myalgia).

- Tinea corporis lesions are not uniformly scaly, nor would they be as numerous or evenly spaced; most of the scale in tinea is seen on the peripheral leading edge of the lesion.

A 7-year-old girl is urgently referred to dermatology for a rash of several weeks’ duration. It is the rash itself, rather than any related symptoms, that frightens the family; the possibility of measles (raised by their primary care provider) compounded their concern. Antifungal cream (clotrimazole) has been of no help.

Physically, the child feels fine, without fever or malaise. But further questioning reveals that she was diagnosed with and treated for strep throat “about a month before” the rash developed.

The child was recently adopted by her aunt and uncle after her parents were killed in an automobile accident. This, understandably, has caused her to fall behind in school. She has no pets, no siblings, and no family history of skin disease.

EXAMINATION

Numerous discrete, round papules and plaques are distributed very evenly on the trunk. They are uniformly scaly and pink, measuring 2 to 3 cm each. In addition, several areas of thick, white, tenacious scaling are seen in the scalp.

The patient’s elbows, knees, and nails are free of any notable change.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is a typical case of guttate psoriasis, which is genetic in predisposition but triggered by strep in the susceptible patient. It’s tempting to partially attribute this case to the child’s high stress level, but this is purely speculative.

Psoriasis affects about 7 million people in the US—more than 150 million worldwide—in a variety of forms. The guttate morphology is seen primarily in children, with plaques that favor extensor surfaces of the arms, trunk, and legs. Biopsy was not needed in this case; if performed, it would have shown characteristic changes (eg, parakeratosis, fusing of rete ridges).

These changes occur because psoriasis, an autoimmune disease, targets keratinocytes—cells that regenerate over a 28-day period to replace the outer layer of skin as it flakes off. With psoriasis, this process is accelerated; keratinocytes move and slough off within a week, creating scaly, inflamed lesions.

Long-term follow-up is needed to monitor the patient’s overall health, because psoriasis increases comorbidity of conditions such as coronary vessel disease, diabetes, stroke, and cancer. In patients with any form of psoriasis, there is the potential for psoriatic arthropathy, a destructive, crippling form of arthropathy that affects up to 25% of all patients. And in a third of guttate psoriasis cases, the condition evolves into permanent plaque psoriasis. For this reason, the guttate variety must be treated aggressively with a combination of phototherapy and topical steroids, adequate treatment of any residual strep, and, in adults, the occasional addition of methotrexate.

Regarding the family’s concern, measles does not involve scaly papules and plaques and would likely cause other constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, myalgia). The other item in the differential, tinea corporis, involves lesions that are not as uniformly scaly, numerous, or evenly spaced. And with tinea, scaling typically occurs on the peripheral leading edge of the lesion.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Guttate psoriasis is more common in children than in adults and is often triggered by strep infection, though stress has also been implicated as a trigger.

- In about a third of all cases, this type evolves into permanent plaque psoriasis. All patients with psoriasis are at risk for psoriatic arthropathy (25% of patients).

- Measles does not involve scaly papules and plaques and would likely cause constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, myalgia).

- Tinea corporis lesions are not uniformly scaly, nor would they be as numerous or evenly spaced; most of the scale in tinea is seen on the peripheral leading edge of the lesion.

A 7-year-old girl is urgently referred to dermatology for a rash of several weeks’ duration. It is the rash itself, rather than any related symptoms, that frightens the family; the possibility of measles (raised by their primary care provider) compounded their concern. Antifungal cream (clotrimazole) has been of no help.

Physically, the child feels fine, without fever or malaise. But further questioning reveals that she was diagnosed with and treated for strep throat “about a month before” the rash developed.

The child was recently adopted by her aunt and uncle after her parents were killed in an automobile accident. This, understandably, has caused her to fall behind in school. She has no pets, no siblings, and no family history of skin disease.

EXAMINATION

Numerous discrete, round papules and plaques are distributed very evenly on the trunk. They are uniformly scaly and pink, measuring 2 to 3 cm each. In addition, several areas of thick, white, tenacious scaling are seen in the scalp.

The patient’s elbows, knees, and nails are free of any notable change.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is a typical case of guttate psoriasis, which is genetic in predisposition but triggered by strep in the susceptible patient. It’s tempting to partially attribute this case to the child’s high stress level, but this is purely speculative.

Psoriasis affects about 7 million people in the US—more than 150 million worldwide—in a variety of forms. The guttate morphology is seen primarily in children, with plaques that favor extensor surfaces of the arms, trunk, and legs. Biopsy was not needed in this case; if performed, it would have shown characteristic changes (eg, parakeratosis, fusing of rete ridges).

These changes occur because psoriasis, an autoimmune disease, targets keratinocytes—cells that regenerate over a 28-day period to replace the outer layer of skin as it flakes off. With psoriasis, this process is accelerated; keratinocytes move and slough off within a week, creating scaly, inflamed lesions.

Long-term follow-up is needed to monitor the patient’s overall health, because psoriasis increases comorbidity of conditions such as coronary vessel disease, diabetes, stroke, and cancer. In patients with any form of psoriasis, there is the potential for psoriatic arthropathy, a destructive, crippling form of arthropathy that affects up to 25% of all patients. And in a third of guttate psoriasis cases, the condition evolves into permanent plaque psoriasis. For this reason, the guttate variety must be treated aggressively with a combination of phototherapy and topical steroids, adequate treatment of any residual strep, and, in adults, the occasional addition of methotrexate.

Regarding the family’s concern, measles does not involve scaly papules and plaques and would likely cause other constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, myalgia). The other item in the differential, tinea corporis, involves lesions that are not as uniformly scaly, numerous, or evenly spaced. And with tinea, scaling typically occurs on the peripheral leading edge of the lesion.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Guttate psoriasis is more common in children than in adults and is often triggered by strep infection, though stress has also been implicated as a trigger.

- In about a third of all cases, this type evolves into permanent plaque psoriasis. All patients with psoriasis are at risk for psoriatic arthropathy (25% of patients).

- Measles does not involve scaly papules and plaques and would likely cause constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, myalgia).

- Tinea corporis lesions are not uniformly scaly, nor would they be as numerous or evenly spaced; most of the scale in tinea is seen on the peripheral leading edge of the lesion.

Hitting a Rough Patch

Since they appeared in early childhood, the lesions on this 50-year-old woman’s arms have waxed and waned, becoming most noticeable in the winter. Although they are generally asymptomatic, the patient is bothered by their rough feel. She admits to picking at them, which causes further irritation. Moisturizers have provided some (temporary) relief.

The patient’s mother and sister have similar lesions, as well as very sensitive skin that overreacts to contactants. The entire family is markedly atopic, with seasonal allergies, asthma, and eczema.

EXAMINATION

The bumps can be seen on the deltoids, triceps, back, and anterior thighs but are particularly prominent on a small area of skin on the patient’s left triceps. The posterior third of both cheeks, which are faintly red, is mildly affected. Overall, glabrous (nonhairy) areas are completely spared.

The individual papules are hyperkeratotic, measure a millimeter or less, and are follicular. Many are faintly erythematous; when picked away, several reveal a coiled hair inside the papule.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

One of the most common dermatologic conditions encountered in medical practice, keratosis pilaris (KP) affects 30% to 50% of the population. KP is an autosomal dominant disorder; the lesions are caused by an inherited overabundance of keratin around follicular orifices, which often precludes the ability of the hair to exit the follicle. The hairs keep growing, but curl up inside the keratotic papule. Fortunately, aside from mild irritation, KP is essentially asymptomatic.

It has a broad range of presentations, from mild to severe. Some children present with a few barely palpable keratotic papules limited to the bilateral triceps, while others have thousands of papules and large patches of prominent follicles that also involve extensor surfaces of hair-bearing skin. Another version of KP, rubra faceii, is distinguished by very red cheeks with keratotic follicular papules; the unwary provider may suspect acne, but that condition presents with comedones and/or a combination of papules, pustules, or cysts confined to sebaceous (oily) areas. The differential also includes Darier disease (keratosis follicularis), but this has a completely different distribution.

KP is often seen in conjunction with atopic stigmata such as eczema, seasonal allergies, xerosis, asthma, and urticaria. It is believed by some to be a marker for atopy.

Treatment is unsatisfactory in terms of a cure, though most patients see their disease lessen over time. Emollients (heavy moisturizers) containing salicylic acid, glycolic acid, ammonium lactate, or retinoic acid can minimize the height of the papules and smooth the skin, but they do not provide a long-term solution.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Keratosis pilaris (KP) is an extremely common autosomal dominant condition that affects 30% to 50% of children.

- It manifests very early in life with tiny, hyperkeratotic, follicular papules in a characteristic distribution.

- The bilateral posterior triceps, deltoids, anterior thighs, buttocks, and face are typically affected, while glabrous skin is spared.

- Treatment is difficult; KP responds to emollients and keratolytics containing salicylic acid, glycolic acid, ammonium lactate, and retinoic acid—but any relief will be temporary.

Since they appeared in early childhood, the lesions on this 50-year-old woman’s arms have waxed and waned, becoming most noticeable in the winter. Although they are generally asymptomatic, the patient is bothered by their rough feel. She admits to picking at them, which causes further irritation. Moisturizers have provided some (temporary) relief.

The patient’s mother and sister have similar lesions, as well as very sensitive skin that overreacts to contactants. The entire family is markedly atopic, with seasonal allergies, asthma, and eczema.

EXAMINATION

The bumps can be seen on the deltoids, triceps, back, and anterior thighs but are particularly prominent on a small area of skin on the patient’s left triceps. The posterior third of both cheeks, which are faintly red, is mildly affected. Overall, glabrous (nonhairy) areas are completely spared.

The individual papules are hyperkeratotic, measure a millimeter or less, and are follicular. Many are faintly erythematous; when picked away, several reveal a coiled hair inside the papule.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

One of the most common dermatologic conditions encountered in medical practice, keratosis pilaris (KP) affects 30% to 50% of the population. KP is an autosomal dominant disorder; the lesions are caused by an inherited overabundance of keratin around follicular orifices, which often precludes the ability of the hair to exit the follicle. The hairs keep growing, but curl up inside the keratotic papule. Fortunately, aside from mild irritation, KP is essentially asymptomatic.

It has a broad range of presentations, from mild to severe. Some children present with a few barely palpable keratotic papules limited to the bilateral triceps, while others have thousands of papules and large patches of prominent follicles that also involve extensor surfaces of hair-bearing skin. Another version of KP, rubra faceii, is distinguished by very red cheeks with keratotic follicular papules; the unwary provider may suspect acne, but that condition presents with comedones and/or a combination of papules, pustules, or cysts confined to sebaceous (oily) areas. The differential also includes Darier disease (keratosis follicularis), but this has a completely different distribution.

KP is often seen in conjunction with atopic stigmata such as eczema, seasonal allergies, xerosis, asthma, and urticaria. It is believed by some to be a marker for atopy.

Treatment is unsatisfactory in terms of a cure, though most patients see their disease lessen over time. Emollients (heavy moisturizers) containing salicylic acid, glycolic acid, ammonium lactate, or retinoic acid can minimize the height of the papules and smooth the skin, but they do not provide a long-term solution.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Keratosis pilaris (KP) is an extremely common autosomal dominant condition that affects 30% to 50% of children.

- It manifests very early in life with tiny, hyperkeratotic, follicular papules in a characteristic distribution.

- The bilateral posterior triceps, deltoids, anterior thighs, buttocks, and face are typically affected, while glabrous skin is spared.

- Treatment is difficult; KP responds to emollients and keratolytics containing salicylic acid, glycolic acid, ammonium lactate, and retinoic acid—but any relief will be temporary.

Since they appeared in early childhood, the lesions on this 50-year-old woman’s arms have waxed and waned, becoming most noticeable in the winter. Although they are generally asymptomatic, the patient is bothered by their rough feel. She admits to picking at them, which causes further irritation. Moisturizers have provided some (temporary) relief.

The patient’s mother and sister have similar lesions, as well as very sensitive skin that overreacts to contactants. The entire family is markedly atopic, with seasonal allergies, asthma, and eczema.

EXAMINATION

The bumps can be seen on the deltoids, triceps, back, and anterior thighs but are particularly prominent on a small area of skin on the patient’s left triceps. The posterior third of both cheeks, which are faintly red, is mildly affected. Overall, glabrous (nonhairy) areas are completely spared.

The individual papules are hyperkeratotic, measure a millimeter or less, and are follicular. Many are faintly erythematous; when picked away, several reveal a coiled hair inside the papule.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

One of the most common dermatologic conditions encountered in medical practice, keratosis pilaris (KP) affects 30% to 50% of the population. KP is an autosomal dominant disorder; the lesions are caused by an inherited overabundance of keratin around follicular orifices, which often precludes the ability of the hair to exit the follicle. The hairs keep growing, but curl up inside the keratotic papule. Fortunately, aside from mild irritation, KP is essentially asymptomatic.

It has a broad range of presentations, from mild to severe. Some children present with a few barely palpable keratotic papules limited to the bilateral triceps, while others have thousands of papules and large patches of prominent follicles that also involve extensor surfaces of hair-bearing skin. Another version of KP, rubra faceii, is distinguished by very red cheeks with keratotic follicular papules; the unwary provider may suspect acne, but that condition presents with comedones and/or a combination of papules, pustules, or cysts confined to sebaceous (oily) areas. The differential also includes Darier disease (keratosis follicularis), but this has a completely different distribution.

KP is often seen in conjunction with atopic stigmata such as eczema, seasonal allergies, xerosis, asthma, and urticaria. It is believed by some to be a marker for atopy.

Treatment is unsatisfactory in terms of a cure, though most patients see their disease lessen over time. Emollients (heavy moisturizers) containing salicylic acid, glycolic acid, ammonium lactate, or retinoic acid can minimize the height of the papules and smooth the skin, but they do not provide a long-term solution.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Keratosis pilaris (KP) is an extremely common autosomal dominant condition that affects 30% to 50% of children.

- It manifests very early in life with tiny, hyperkeratotic, follicular papules in a characteristic distribution.

- The bilateral posterior triceps, deltoids, anterior thighs, buttocks, and face are typically affected, while glabrous skin is spared.

- Treatment is difficult; KP responds to emollients and keratolytics containing salicylic acid, glycolic acid, ammonium lactate, and retinoic acid—but any relief will be temporary.

She's Losing It—Her Hair, That Is

Following the stressful divorce of her parents, this 8-year-old girl’s hair began to fall out, prompting her referral to dermatology. Along with the hair loss, she has mild itching and burning in the area.

The child has a history of several atopic phenomena, including seasonal allergies, asthma, and eczema—all of which are replete in her family’s history.

EXAMINATION

The child is in no distress and is quite willing to show the affected area—a sizeable (10 x 8 cm), roughly round area of complete hair loss involving the nuchal periphery of her scalp. Fortunately, the area is covered by longer hair that drapes down.

No epidermal changes (ie, redness, scaling, edema) are seen, and no nodes are palpable in the area. Her arms, brows, and lashes appear normal after careful examination.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Alopecia areata (AA) is quite common, especially among children, and affects both genders equally. It appears to be stress-related and can manifest in many forms. This particular type, with its distinguishing features of large size and peripheral involvement of the scalp margin, is known as ophiasis.

However, the real significance of ophiasis is its uncertain prognosis. For this patient, the extent and type of hair loss, her young age, and her atopic history all predict a poor prognosis. The hair loss is likely to be slow to resolve, if it does at all. It could progress to loss of all scalp hair (alopecia totalis) or every hair on her body (alopecia universalis).

Compounding the problem is the fact that no good treatment exists for this autoimmune disease, which affects those with genetic predisposition. Topical steroid application or intralesional steroid injections (3 to 5 mg/cc triamcinolone suspension) can promote the growth of a few hairs, but neither have an effect on the ultimate outcome. There have been reports of benefit from injectable biologics and oral antimalarials, but these medications have not been approved for use in AA.

Histopathologic studies with special stains show a lymphocytic infiltrate surrounding the hair follicle that prevents the growth of new hairs. Glucocorticoids (eg, prednisone) resolve this and allow new hair growth, but the treatment must be continued for months with unjustifiable adverse effects. Even then, full resolution must come on its own.

This patient was treated with a month-long course of topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream. But as stated above, her prognosis is somewhat guarded.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune process and a common cause of localized hair loss.

- This hair loss is usually acute, complete, and round, and is often seen in multiple patches.

- Of the many forms of AA, this one (ophiasis) has a less certain prognosis, worsened by youth, atopy, and lesion size.

- While ordinary AA resolves on its own in most cases, ophiasis can progress into total loss of scalp hair (alopecia totalis) or loss of all body hair (alopecia universalis).

Following the stressful divorce of her parents, this 8-year-old girl’s hair began to fall out, prompting her referral to dermatology. Along with the hair loss, she has mild itching and burning in the area.

The child has a history of several atopic phenomena, including seasonal allergies, asthma, and eczema—all of which are replete in her family’s history.

EXAMINATION

The child is in no distress and is quite willing to show the affected area—a sizeable (10 x 8 cm), roughly round area of complete hair loss involving the nuchal periphery of her scalp. Fortunately, the area is covered by longer hair that drapes down.

No epidermal changes (ie, redness, scaling, edema) are seen, and no nodes are palpable in the area. Her arms, brows, and lashes appear normal after careful examination.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Alopecia areata (AA) is quite common, especially among children, and affects both genders equally. It appears to be stress-related and can manifest in many forms. This particular type, with its distinguishing features of large size and peripheral involvement of the scalp margin, is known as ophiasis.

However, the real significance of ophiasis is its uncertain prognosis. For this patient, the extent and type of hair loss, her young age, and her atopic history all predict a poor prognosis. The hair loss is likely to be slow to resolve, if it does at all. It could progress to loss of all scalp hair (alopecia totalis) or every hair on her body (alopecia universalis).

Compounding the problem is the fact that no good treatment exists for this autoimmune disease, which affects those with genetic predisposition. Topical steroid application or intralesional steroid injections (3 to 5 mg/cc triamcinolone suspension) can promote the growth of a few hairs, but neither have an effect on the ultimate outcome. There have been reports of benefit from injectable biologics and oral antimalarials, but these medications have not been approved for use in AA.

Histopathologic studies with special stains show a lymphocytic infiltrate surrounding the hair follicle that prevents the growth of new hairs. Glucocorticoids (eg, prednisone) resolve this and allow new hair growth, but the treatment must be continued for months with unjustifiable adverse effects. Even then, full resolution must come on its own.

This patient was treated with a month-long course of topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream. But as stated above, her prognosis is somewhat guarded.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune process and a common cause of localized hair loss.

- This hair loss is usually acute, complete, and round, and is often seen in multiple patches.

- Of the many forms of AA, this one (ophiasis) has a less certain prognosis, worsened by youth, atopy, and lesion size.

- While ordinary AA resolves on its own in most cases, ophiasis can progress into total loss of scalp hair (alopecia totalis) or loss of all body hair (alopecia universalis).

Following the stressful divorce of her parents, this 8-year-old girl’s hair began to fall out, prompting her referral to dermatology. Along with the hair loss, she has mild itching and burning in the area.

The child has a history of several atopic phenomena, including seasonal allergies, asthma, and eczema—all of which are replete in her family’s history.

EXAMINATION

The child is in no distress and is quite willing to show the affected area—a sizeable (10 x 8 cm), roughly round area of complete hair loss involving the nuchal periphery of her scalp. Fortunately, the area is covered by longer hair that drapes down.

No epidermal changes (ie, redness, scaling, edema) are seen, and no nodes are palpable in the area. Her arms, brows, and lashes appear normal after careful examination.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Alopecia areata (AA) is quite common, especially among children, and affects both genders equally. It appears to be stress-related and can manifest in many forms. This particular type, with its distinguishing features of large size and peripheral involvement of the scalp margin, is known as ophiasis.

However, the real significance of ophiasis is its uncertain prognosis. For this patient, the extent and type of hair loss, her young age, and her atopic history all predict a poor prognosis. The hair loss is likely to be slow to resolve, if it does at all. It could progress to loss of all scalp hair (alopecia totalis) or every hair on her body (alopecia universalis).

Compounding the problem is the fact that no good treatment exists for this autoimmune disease, which affects those with genetic predisposition. Topical steroid application or intralesional steroid injections (3 to 5 mg/cc triamcinolone suspension) can promote the growth of a few hairs, but neither have an effect on the ultimate outcome. There have been reports of benefit from injectable biologics and oral antimalarials, but these medications have not been approved for use in AA.

Histopathologic studies with special stains show a lymphocytic infiltrate surrounding the hair follicle that prevents the growth of new hairs. Glucocorticoids (eg, prednisone) resolve this and allow new hair growth, but the treatment must be continued for months with unjustifiable adverse effects. Even then, full resolution must come on its own.

This patient was treated with a month-long course of topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream. But as stated above, her prognosis is somewhat guarded.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune process and a common cause of localized hair loss.

- This hair loss is usually acute, complete, and round, and is often seen in multiple patches.

- Of the many forms of AA, this one (ophiasis) has a less certain prognosis, worsened by youth, atopy, and lesion size.

- While ordinary AA resolves on its own in most cases, ophiasis can progress into total loss of scalp hair (alopecia totalis) or loss of all body hair (alopecia universalis).

"It's the Pits"

The several-week duration of this 14-year-old boy’s rash is worrisome to him and his family, despite a lack of other symptoms. Located on his right axilla, the rash was previously diagnosed as “yeast infection” but was unaffected by topical anti-yeast medications (nystatin and clotrimazole creams) and oral fluconazole.

A serious family crisis preceded the appearance of the rash: The parents lost custody of their children, who were then placed under the care of grandparents in another state. The boy lost his family and friends and had to start again in a new school.

EXAMINATION

Additional rashes are present on his face, in and behind his ears, and on focal areas of his genitals. They are all orangish red with faintly scaly surfaces. The scale on his face, ears, and genitals is coarser than that of his axilla, but it is the same salmon-pink. Focal areas of his brows and scalp are also involved.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Seborrhea, or seborrheic dermatitis, is most commonly seen on the scalp in the form of dandruff, but it can also flare in other locations. Seborrhea is an adverse inflammatory response to the consumption of sebum by commensal yeast organisms (eg, Pityrosporum) on oil-rich skin. Stress is believed to trigger flares (as exemplified in this case), presumably because it increases the production and outflow of sebum.

Non-dermatology providers often incorrectly diagnose axillary rashes as yeast infections, or seborrhea on the face as fungal infection, simply for lack of a complete differential. The truth is, yeast infections of the skin are unusual. The differential should include psoriasis or eczema, as well as sebopsoriasis (an overlap condition with signs of both seborrhea and psoriasis).

The “trick” to diagnosing seborrhea is to recognize that it is incredibly common (affecting around 30% of the Caucasian population), is often inherited, and can affect multiple sites. When it is seen in one area, corroboration can be sought by locating typical changes elsewhere.

Although there is no cure, control is obtained through use of topical anti-yeast creams (eg, ketoconazole) combined with a mild topical steroid (eg, 2.5% hydrocortisone). Using ketoconazole 2% shampoo for the scalp and other affected areas can be helpful as well. Use of nystatin, however, has long been replaced by more effective alternatives.

With a bit of luck, the patient’s stress will diminish over time, which should be a big help in resolving this problem.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Seborrhea, or seborrheic dermatitis, is extremely common among those of northern European descent and can affect not only the scalp, but also the face, ears, chest, axillae, and genitals.

- The rash is usually orangish pink and slightly scaly, unless it’s in the axillae, where moisture and friction preclude the formation of significant scale.

- Seborrhea is often misdiagnosed as yeast infection, but the latter is quite unusual on the skin.

- The differential should include psoriasis, eczema, and sebopsoriasis (an overlap condition with signs of both seborrhea and psoriasis).

The several-week duration of this 14-year-old boy’s rash is worrisome to him and his family, despite a lack of other symptoms. Located on his right axilla, the rash was previously diagnosed as “yeast infection” but was unaffected by topical anti-yeast medications (nystatin and clotrimazole creams) and oral fluconazole.

A serious family crisis preceded the appearance of the rash: The parents lost custody of their children, who were then placed under the care of grandparents in another state. The boy lost his family and friends and had to start again in a new school.

EXAMINATION

Additional rashes are present on his face, in and behind his ears, and on focal areas of his genitals. They are all orangish red with faintly scaly surfaces. The scale on his face, ears, and genitals is coarser than that of his axilla, but it is the same salmon-pink. Focal areas of his brows and scalp are also involved.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Seborrhea, or seborrheic dermatitis, is most commonly seen on the scalp in the form of dandruff, but it can also flare in other locations. Seborrhea is an adverse inflammatory response to the consumption of sebum by commensal yeast organisms (eg, Pityrosporum) on oil-rich skin. Stress is believed to trigger flares (as exemplified in this case), presumably because it increases the production and outflow of sebum.

Non-dermatology providers often incorrectly diagnose axillary rashes as yeast infections, or seborrhea on the face as fungal infection, simply for lack of a complete differential. The truth is, yeast infections of the skin are unusual. The differential should include psoriasis or eczema, as well as sebopsoriasis (an overlap condition with signs of both seborrhea and psoriasis).

The “trick” to diagnosing seborrhea is to recognize that it is incredibly common (affecting around 30% of the Caucasian population), is often inherited, and can affect multiple sites. When it is seen in one area, corroboration can be sought by locating typical changes elsewhere.

Although there is no cure, control is obtained through use of topical anti-yeast creams (eg, ketoconazole) combined with a mild topical steroid (eg, 2.5% hydrocortisone). Using ketoconazole 2% shampoo for the scalp and other affected areas can be helpful as well. Use of nystatin, however, has long been replaced by more effective alternatives.

With a bit of luck, the patient’s stress will diminish over time, which should be a big help in resolving this problem.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Seborrhea, or seborrheic dermatitis, is extremely common among those of northern European descent and can affect not only the scalp, but also the face, ears, chest, axillae, and genitals.

- The rash is usually orangish pink and slightly scaly, unless it’s in the axillae, where moisture and friction preclude the formation of significant scale.

- Seborrhea is often misdiagnosed as yeast infection, but the latter is quite unusual on the skin.

- The differential should include psoriasis, eczema, and sebopsoriasis (an overlap condition with signs of both seborrhea and psoriasis).

The several-week duration of this 14-year-old boy’s rash is worrisome to him and his family, despite a lack of other symptoms. Located on his right axilla, the rash was previously diagnosed as “yeast infection” but was unaffected by topical anti-yeast medications (nystatin and clotrimazole creams) and oral fluconazole.

A serious family crisis preceded the appearance of the rash: The parents lost custody of their children, who were then placed under the care of grandparents in another state. The boy lost his family and friends and had to start again in a new school.

EXAMINATION

Additional rashes are present on his face, in and behind his ears, and on focal areas of his genitals. They are all orangish red with faintly scaly surfaces. The scale on his face, ears, and genitals is coarser than that of his axilla, but it is the same salmon-pink. Focal areas of his brows and scalp are also involved.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Seborrhea, or seborrheic dermatitis, is most commonly seen on the scalp in the form of dandruff, but it can also flare in other locations. Seborrhea is an adverse inflammatory response to the consumption of sebum by commensal yeast organisms (eg, Pityrosporum) on oil-rich skin. Stress is believed to trigger flares (as exemplified in this case), presumably because it increases the production and outflow of sebum.

Non-dermatology providers often incorrectly diagnose axillary rashes as yeast infections, or seborrhea on the face as fungal infection, simply for lack of a complete differential. The truth is, yeast infections of the skin are unusual. The differential should include psoriasis or eczema, as well as sebopsoriasis (an overlap condition with signs of both seborrhea and psoriasis).

The “trick” to diagnosing seborrhea is to recognize that it is incredibly common (affecting around 30% of the Caucasian population), is often inherited, and can affect multiple sites. When it is seen in one area, corroboration can be sought by locating typical changes elsewhere.

Although there is no cure, control is obtained through use of topical anti-yeast creams (eg, ketoconazole) combined with a mild topical steroid (eg, 2.5% hydrocortisone). Using ketoconazole 2% shampoo for the scalp and other affected areas can be helpful as well. Use of nystatin, however, has long been replaced by more effective alternatives.

With a bit of luck, the patient’s stress will diminish over time, which should be a big help in resolving this problem.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Seborrhea, or seborrheic dermatitis, is extremely common among those of northern European descent and can affect not only the scalp, but also the face, ears, chest, axillae, and genitals.

- The rash is usually orangish pink and slightly scaly, unless it’s in the axillae, where moisture and friction preclude the formation of significant scale.

- Seborrhea is often misdiagnosed as yeast infection, but the latter is quite unusual on the skin.

- The differential should include psoriasis, eczema, and sebopsoriasis (an overlap condition with signs of both seborrhea and psoriasis).

Sunny With a Chance of Skin Damage

A 56-year-old woman has several lesions she is worried might be cancerous. Added to that, there have been changes to her facial skin over the past several years that are increasingly obvious to her friends and family and therefore concerning to the patient.

She has an extensive history of nonmelanoma skin cancers, including basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas, which were removed from her trunk in the distant past. She has lived in the southwestern United States all her life and has been smoking cigarettes since age 14.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s skin is quite fair, with abundant evidence of sun damage. She looks considerably older than her stated age.

Fortunately, no skin cancers are found on examination, but many closed and open comedones can be seen on both of her cheeks, stippled on rough, weathered skin. Solar elastosis manifests in this area as diffuse white thickening—what some might call “chicken skin.”

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS) is a fairly common result of chronic overexposure to UV sources; it is especially prevalent among men who smoke. For reasons not fully understood, the changes associated with FRS tend to be relegated to the bilateral malar cheeks, roughly even with the eyes. Apart from the patient being female, this case is quite typical.

Chronic overexposure to UV light is known to result in dermatologic changes such as solar elastosis and the aforementioned whitish plaques—which, on microscopic exam, are simply basophilic degeneration of the dermis. This degeneration can be seen all over the face, but it is particularly evident on the forehead and cheeks; the concentration of comedones on the cheeks is unique to FRS.

Treatment options include lasers and peels, which involve considerable expenditure of time and money. While the comedones can be extracted, they are likely to recur unless more invasive methods are used.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS) is seen primarily in men with chronic overexposure to sunlight—particularly those who smoke.

- FRS is characterized by localized collections of open and closed comedones superimposed on thickened, white “chicken skin” (solar elastosis).

- These changes typically occur on the bilateral cheeks of patients in the later decades of life, though they have been seen on patients in their 20s.

- Treatment is possible by means of laser resurfacing and/or chemical peels.

A 56-year-old woman has several lesions she is worried might be cancerous. Added to that, there have been changes to her facial skin over the past several years that are increasingly obvious to her friends and family and therefore concerning to the patient.

She has an extensive history of nonmelanoma skin cancers, including basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas, which were removed from her trunk in the distant past. She has lived in the southwestern United States all her life and has been smoking cigarettes since age 14.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s skin is quite fair, with abundant evidence of sun damage. She looks considerably older than her stated age.

Fortunately, no skin cancers are found on examination, but many closed and open comedones can be seen on both of her cheeks, stippled on rough, weathered skin. Solar elastosis manifests in this area as diffuse white thickening—what some might call “chicken skin.”

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS) is a fairly common result of chronic overexposure to UV sources; it is especially prevalent among men who smoke. For reasons not fully understood, the changes associated with FRS tend to be relegated to the bilateral malar cheeks, roughly even with the eyes. Apart from the patient being female, this case is quite typical.

Chronic overexposure to UV light is known to result in dermatologic changes such as solar elastosis and the aforementioned whitish plaques—which, on microscopic exam, are simply basophilic degeneration of the dermis. This degeneration can be seen all over the face, but it is particularly evident on the forehead and cheeks; the concentration of comedones on the cheeks is unique to FRS.

Treatment options include lasers and peels, which involve considerable expenditure of time and money. While the comedones can be extracted, they are likely to recur unless more invasive methods are used.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS) is seen primarily in men with chronic overexposure to sunlight—particularly those who smoke.

- FRS is characterized by localized collections of open and closed comedones superimposed on thickened, white “chicken skin” (solar elastosis).

- These changes typically occur on the bilateral cheeks of patients in the later decades of life, though they have been seen on patients in their 20s.

- Treatment is possible by means of laser resurfacing and/or chemical peels.

A 56-year-old woman has several lesions she is worried might be cancerous. Added to that, there have been changes to her facial skin over the past several years that are increasingly obvious to her friends and family and therefore concerning to the patient.

She has an extensive history of nonmelanoma skin cancers, including basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas, which were removed from her trunk in the distant past. She has lived in the southwestern United States all her life and has been smoking cigarettes since age 14.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s skin is quite fair, with abundant evidence of sun damage. She looks considerably older than her stated age.

Fortunately, no skin cancers are found on examination, but many closed and open comedones can be seen on both of her cheeks, stippled on rough, weathered skin. Solar elastosis manifests in this area as diffuse white thickening—what some might call “chicken skin.”

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS) is a fairly common result of chronic overexposure to UV sources; it is especially prevalent among men who smoke. For reasons not fully understood, the changes associated with FRS tend to be relegated to the bilateral malar cheeks, roughly even with the eyes. Apart from the patient being female, this case is quite typical.

Chronic overexposure to UV light is known to result in dermatologic changes such as solar elastosis and the aforementioned whitish plaques—which, on microscopic exam, are simply basophilic degeneration of the dermis. This degeneration can be seen all over the face, but it is particularly evident on the forehead and cheeks; the concentration of comedones on the cheeks is unique to FRS.

Treatment options include lasers and peels, which involve considerable expenditure of time and money. While the comedones can be extracted, they are likely to recur unless more invasive methods are used.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS) is seen primarily in men with chronic overexposure to sunlight—particularly those who smoke.

- FRS is characterized by localized collections of open and closed comedones superimposed on thickened, white “chicken skin” (solar elastosis).

- These changes typically occur on the bilateral cheeks of patients in the later decades of life, though they have been seen on patients in their 20s.

- Treatment is possible by means of laser resurfacing and/or chemical peels.

Perplexingly Purple

A 55-year-old woman presents for evaluation of a widespread rash that first appeared several months ago. The rash has resisted treatment with various OTC products—antifungal cream (tolnaftate), triple-antibiotic cream, and tea tree oil—and continues to itch terribly at times.

Her primary care provider prescribed oral terbinafine (250 mg/d) for a proposed fungal etiology after viewing the rash with a Wood lamp and performing a KOH prep. A one-month course yielded no relief.

The patient claims to be in good health otherwise. She does admit to going through a stressful period involving job loss, divorce, and care of her aging parents.

EXAMINATION

Multiple papulosquamous papules, nodules, and plaques are located on the patient’s arms, legs, wrists, and sacrum. The lesions range from pinpoint to several centimeters and oval to polygonal. They have a striking purple appearance. On closer inspection, many have a shiny, whitish sheen on the surface.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is a classic case of lichen planus (LP), an unusual papulosquamous condition of unknown etiology. In addition to the mentioned areas, it can affect the mucosal surfaces, scalp, genitals, nails, and internal organs.

There is no evidence that the cause is infectious; rather, it appears to be triggered by a reaction to an unknown (possibly autoimmune) antigen. LP targets specific cells and produces a lichenoid reaction, in which the upper level of the dermis is broken down by an apoptotic process. This produces a characteristic sawtooth pattern at the dermoepidermal junction by a pathognomic lymphocytic infiltrate. The surface of the affected skin has a shiny, frosty appearance, also seen in other lichenoid conditions (eg, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus).

Other key diagnostic features are classified as “the Ps”: purple, plaquish, papular, planar (flat-topped), polygonal (multi-angular), penile, pruritic, and puzzling. The last word is key to triggering consideration of the other “Ps.”

LP that affects the scalp and mucosal surfaces can be problematic to treat. Topical steroids are the mainstay, but treatment can also include oral retinoids (acetretin, isotretinoin), methotrexate, antimalarials, and cyclosporine. Furthermore, LP can overlap with other diseases—notably lupus, for which TNF-[a] inhibitors are used with some success. For limited disease, intralesional steroid injections can be used (5 to 10 mg/cc triamcinolone).

This patient achieved good relief with a combination of topical and intralesional steroids. Fortunately, in most cases, the disease eventually resolves on its own.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Lichen planus is an unusual condition, but the look and distribution seen in this case are fairly typical.

- The classic diagnostic “Ps” include: purple, papular, pruritic, plaquish, planar, and most of all puzzling.

- Wood lamp examination is useless for the most common dermatophytoses, which will not fluoresce; however, KOH preps are useful when correctly interpreted.

- In more obscure cases, a punch or shave biopsy will confirm the diagnosis.

A 55-year-old woman presents for evaluation of a widespread rash that first appeared several months ago. The rash has resisted treatment with various OTC products—antifungal cream (tolnaftate), triple-antibiotic cream, and tea tree oil—and continues to itch terribly at times.

Her primary care provider prescribed oral terbinafine (250 mg/d) for a proposed fungal etiology after viewing the rash with a Wood lamp and performing a KOH prep. A one-month course yielded no relief.

The patient claims to be in good health otherwise. She does admit to going through a stressful period involving job loss, divorce, and care of her aging parents.

EXAMINATION

Multiple papulosquamous papules, nodules, and plaques are located on the patient’s arms, legs, wrists, and sacrum. The lesions range from pinpoint to several centimeters and oval to polygonal. They have a striking purple appearance. On closer inspection, many have a shiny, whitish sheen on the surface.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is a classic case of lichen planus (LP), an unusual papulosquamous condition of unknown etiology. In addition to the mentioned areas, it can affect the mucosal surfaces, scalp, genitals, nails, and internal organs.

There is no evidence that the cause is infectious; rather, it appears to be triggered by a reaction to an unknown (possibly autoimmune) antigen. LP targets specific cells and produces a lichenoid reaction, in which the upper level of the dermis is broken down by an apoptotic process. This produces a characteristic sawtooth pattern at the dermoepidermal junction by a pathognomic lymphocytic infiltrate. The surface of the affected skin has a shiny, frosty appearance, also seen in other lichenoid conditions (eg, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus).

Other key diagnostic features are classified as “the Ps”: purple, plaquish, papular, planar (flat-topped), polygonal (multi-angular), penile, pruritic, and puzzling. The last word is key to triggering consideration of the other “Ps.”

LP that affects the scalp and mucosal surfaces can be problematic to treat. Topical steroids are the mainstay, but treatment can also include oral retinoids (acetretin, isotretinoin), methotrexate, antimalarials, and cyclosporine. Furthermore, LP can overlap with other diseases—notably lupus, for which TNF-[a] inhibitors are used with some success. For limited disease, intralesional steroid injections can be used (5 to 10 mg/cc triamcinolone).

This patient achieved good relief with a combination of topical and intralesional steroids. Fortunately, in most cases, the disease eventually resolves on its own.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Lichen planus is an unusual condition, but the look and distribution seen in this case are fairly typical.

- The classic diagnostic “Ps” include: purple, papular, pruritic, plaquish, planar, and most of all puzzling.

- Wood lamp examination is useless for the most common dermatophytoses, which will not fluoresce; however, KOH preps are useful when correctly interpreted.

- In more obscure cases, a punch or shave biopsy will confirm the diagnosis.

A 55-year-old woman presents for evaluation of a widespread rash that first appeared several months ago. The rash has resisted treatment with various OTC products—antifungal cream (tolnaftate), triple-antibiotic cream, and tea tree oil—and continues to itch terribly at times.

Her primary care provider prescribed oral terbinafine (250 mg/d) for a proposed fungal etiology after viewing the rash with a Wood lamp and performing a KOH prep. A one-month course yielded no relief.

The patient claims to be in good health otherwise. She does admit to going through a stressful period involving job loss, divorce, and care of her aging parents.

EXAMINATION

Multiple papulosquamous papules, nodules, and plaques are located on the patient’s arms, legs, wrists, and sacrum. The lesions range from pinpoint to several centimeters and oval to polygonal. They have a striking purple appearance. On closer inspection, many have a shiny, whitish sheen on the surface.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is a classic case of lichen planus (LP), an unusual papulosquamous condition of unknown etiology. In addition to the mentioned areas, it can affect the mucosal surfaces, scalp, genitals, nails, and internal organs.

There is no evidence that the cause is infectious; rather, it appears to be triggered by a reaction to an unknown (possibly autoimmune) antigen. LP targets specific cells and produces a lichenoid reaction, in which the upper level of the dermis is broken down by an apoptotic process. This produces a characteristic sawtooth pattern at the dermoepidermal junction by a pathognomic lymphocytic infiltrate. The surface of the affected skin has a shiny, frosty appearance, also seen in other lichenoid conditions (eg, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus).

Other key diagnostic features are classified as “the Ps”: purple, plaquish, papular, planar (flat-topped), polygonal (multi-angular), penile, pruritic, and puzzling. The last word is key to triggering consideration of the other “Ps.”

LP that affects the scalp and mucosal surfaces can be problematic to treat. Topical steroids are the mainstay, but treatment can also include oral retinoids (acetretin, isotretinoin), methotrexate, antimalarials, and cyclosporine. Furthermore, LP can overlap with other diseases—notably lupus, for which TNF-[a] inhibitors are used with some success. For limited disease, intralesional steroid injections can be used (5 to 10 mg/cc triamcinolone).

This patient achieved good relief with a combination of topical and intralesional steroids. Fortunately, in most cases, the disease eventually resolves on its own.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Lichen planus is an unusual condition, but the look and distribution seen in this case are fairly typical.

- The classic diagnostic “Ps” include: purple, papular, pruritic, plaquish, planar, and most of all puzzling.

- Wood lamp examination is useless for the most common dermatophytoses, which will not fluoresce; however, KOH preps are useful when correctly interpreted.

- In more obscure cases, a punch or shave biopsy will confirm the diagnosis.

It's Not Appealing, But It Is A-Peeling

A 6-year-old boy is referred to dermatology for evaluation of his dry, thin skin. Since birth, it has frequently torn, and it burns with the application of almost any product or soap. Neither OTC nor prescription products have helped.

The boy is reportedly in good health otherwise and is not atopic. Nonetheless, two of his siblings are similarly affected, and there is a strong family history of similar dermatologic problems on his father’s side. He and his family are from Mexico and have type IV skin.

EXAMINATION

The patient is in no distress but does complain about his skin problems. His skin is quite thin and dry, and fine scaling covers his palms, face, legs, trunk, and scalp. In short, none of his skin looks normal. The skin on his legs is especially scaly and has a pronounced reticulated appearance.

His fingernails are dystrophic, with transverse ridging and a loss of connection between the cuticles and nail plates.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Ichthyosis vulgaris (IV) is one of a family of disorders that cause a breakdown of normal filamentous structures (filaggrin) that hold the layers of skin together. This breakdown can lead to excessive water loss, as well as vulnerability of skin to penetration by allergens and other noxious substances.

IV is by far the most common variation, comprising at least 95% of all ichthyosiform dermatoses. It results from an inherited abnormality of epidermal differentiation or metabolism; affected patients have a higher incidence of eye problems (eg, keratitis, cataracts) in addition to their skin problems.

A total of 28 types of ichthyosis have been described, many of which are part of larger syndromes (such as keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome or Netherton syndrome). Another uncommon type, X-linked recessive ichthyosis, manifests in about 1 in 5,000 births; these patients improve dramatically in the summertime with additional sun exposure.

Ichthyosis manifests with varying degrees of severity. While this case is fairly severe, the worst cases (Harlequin and lamellar forms) begin at birth with a nearly absent stratum corneum.

This patient and his family were advised on the use of emollients and avoidance of excessive drying of skin. They were also strongly encouraged to seek genetic counseling.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Ichthyosis is a family of disorders that cause a breakdown of normal filamentous structures (filaggrin) that hold the layers of skin together.

- The resultant water loss can leave skin vulnerable to penetration by allergens and other noxious substances.

- Ichthyosis vulgaris is by far the most common member of this family of disorders, comprising more than 95% of cases.

- Heavy emollients and avoidance of drying constitute the bulk of treatment efforts.

A 6-year-old boy is referred to dermatology for evaluation of his dry, thin skin. Since birth, it has frequently torn, and it burns with the application of almost any product or soap. Neither OTC nor prescription products have helped.

The boy is reportedly in good health otherwise and is not atopic. Nonetheless, two of his siblings are similarly affected, and there is a strong family history of similar dermatologic problems on his father’s side. He and his family are from Mexico and have type IV skin.

EXAMINATION

The patient is in no distress but does complain about his skin problems. His skin is quite thin and dry, and fine scaling covers his palms, face, legs, trunk, and scalp. In short, none of his skin looks normal. The skin on his legs is especially scaly and has a pronounced reticulated appearance.

His fingernails are dystrophic, with transverse ridging and a loss of connection between the cuticles and nail plates.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Ichthyosis vulgaris (IV) is one of a family of disorders that cause a breakdown of normal filamentous structures (filaggrin) that hold the layers of skin together. This breakdown can lead to excessive water loss, as well as vulnerability of skin to penetration by allergens and other noxious substances.

IV is by far the most common variation, comprising at least 95% of all ichthyosiform dermatoses. It results from an inherited abnormality of epidermal differentiation or metabolism; affected patients have a higher incidence of eye problems (eg, keratitis, cataracts) in addition to their skin problems.

A total of 28 types of ichthyosis have been described, many of which are part of larger syndromes (such as keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome or Netherton syndrome). Another uncommon type, X-linked recessive ichthyosis, manifests in about 1 in 5,000 births; these patients improve dramatically in the summertime with additional sun exposure.

Ichthyosis manifests with varying degrees of severity. While this case is fairly severe, the worst cases (Harlequin and lamellar forms) begin at birth with a nearly absent stratum corneum.

This patient and his family were advised on the use of emollients and avoidance of excessive drying of skin. They were also strongly encouraged to seek genetic counseling.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Ichthyosis is a family of disorders that cause a breakdown of normal filamentous structures (filaggrin) that hold the layers of skin together.

- The resultant water loss can leave skin vulnerable to penetration by allergens and other noxious substances.

- Ichthyosis vulgaris is by far the most common member of this family of disorders, comprising more than 95% of cases.

- Heavy emollients and avoidance of drying constitute the bulk of treatment efforts.

A 6-year-old boy is referred to dermatology for evaluation of his dry, thin skin. Since birth, it has frequently torn, and it burns with the application of almost any product or soap. Neither OTC nor prescription products have helped.

The boy is reportedly in good health otherwise and is not atopic. Nonetheless, two of his siblings are similarly affected, and there is a strong family history of similar dermatologic problems on his father’s side. He and his family are from Mexico and have type IV skin.

EXAMINATION

The patient is in no distress but does complain about his skin problems. His skin is quite thin and dry, and fine scaling covers his palms, face, legs, trunk, and scalp. In short, none of his skin looks normal. The skin on his legs is especially scaly and has a pronounced reticulated appearance.

His fingernails are dystrophic, with transverse ridging and a loss of connection between the cuticles and nail plates.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Ichthyosis vulgaris (IV) is one of a family of disorders that cause a breakdown of normal filamentous structures (filaggrin) that hold the layers of skin together. This breakdown can lead to excessive water loss, as well as vulnerability of skin to penetration by allergens and other noxious substances.

IV is by far the most common variation, comprising at least 95% of all ichthyosiform dermatoses. It results from an inherited abnormality of epidermal differentiation or metabolism; affected patients have a higher incidence of eye problems (eg, keratitis, cataracts) in addition to their skin problems.

A total of 28 types of ichthyosis have been described, many of which are part of larger syndromes (such as keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome or Netherton syndrome). Another uncommon type, X-linked recessive ichthyosis, manifests in about 1 in 5,000 births; these patients improve dramatically in the summertime with additional sun exposure.

Ichthyosis manifests with varying degrees of severity. While this case is fairly severe, the worst cases (Harlequin and lamellar forms) begin at birth with a nearly absent stratum corneum.

This patient and his family were advised on the use of emollients and avoidance of excessive drying of skin. They were also strongly encouraged to seek genetic counseling.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Ichthyosis is a family of disorders that cause a breakdown of normal filamentous structures (filaggrin) that hold the layers of skin together.

- The resultant water loss can leave skin vulnerable to penetration by allergens and other noxious substances.

- Ichthyosis vulgaris is by far the most common member of this family of disorders, comprising more than 95% of cases.

- Heavy emollients and avoidance of drying constitute the bulk of treatment efforts.

Friends Don't Let Friends Ignore Skin Problems

This 58-year-old woman was unaware there was a problem with her neck skin until friends took a picture and showed it to her. She was surprised and distressed, thinking the changes were new and therefore representative of serious disease.

She denies having any associated symptoms but does admit to a great deal of sun exposure over the years. Her history is significant for a basal cell carcinoma, removed from her chest many years ago. She also has a history of smoking and early COPD.

EXAMINATION

A solid sheet of fine, blanchable telangiectasias spreads across the patient’s upper anterior neck, extending down onto her chest. It spares the skin directly under her chin, leaving an unaffected white oval area.

Elsewhere, the patient has a great deal of dermatoheliosis superimposed on her type II skin, including solar lentigines, weathering, and focal solar elastosis.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This particular pattern of mottled hyper- and hypopigmented skin is a result of overexposure to UV light. The name for this common problem—seen far more commonly in women than in men—is poikiloderma of Civatte (PC). This case is typical in that the changes manifested and progressed so slowly that the patient didn’t notice.

PC can manifest with combinations of red, brown, and yellow discoloration around the neck. In this case, the dominant color was red. The oval area of spared skin was created by the shade of the patient’s chin.

Similar changes can be seen with other conditions, such as poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans, a manifestation of small plaque parapsoriasis. However, this typically affects areas below the waist and does not have areas of sparing.

Treatment has been attempted with lasers and peels, yielding mixed success. Because of her condition’s benignancy, this patient did not opt for treatment.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Poikiloderma of Civatte (PC) is a permanent skin change caused by overexposure to the sun or another UV source; it is more common in women than men.

- PC manifests with mottled hyper- or hypopigmented patches of skin on the anterior neck and upper chest, which develop gradually over the course of decades. Many patients also have sheets of telangiectasias covering the affected area.

- A distinct area of sparing (usually oval) is typically seen on the upper anterior neck, due to the chin’s shading of this area.

- Laser treatment has been somewhat successful in lightening the affected skin.

This 58-year-old woman was unaware there was a problem with her neck skin until friends took a picture and showed it to her. She was surprised and distressed, thinking the changes were new and therefore representative of serious disease.

She denies having any associated symptoms but does admit to a great deal of sun exposure over the years. Her history is significant for a basal cell carcinoma, removed from her chest many years ago. She also has a history of smoking and early COPD.

EXAMINATION

A solid sheet of fine, blanchable telangiectasias spreads across the patient’s upper anterior neck, extending down onto her chest. It spares the skin directly under her chin, leaving an unaffected white oval area.

Elsewhere, the patient has a great deal of dermatoheliosis superimposed on her type II skin, including solar lentigines, weathering, and focal solar elastosis.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This particular pattern of mottled hyper- and hypopigmented skin is a result of overexposure to UV light. The name for this common problem—seen far more commonly in women than in men—is poikiloderma of Civatte (PC). This case is typical in that the changes manifested and progressed so slowly that the patient didn’t notice.

PC can manifest with combinations of red, brown, and yellow discoloration around the neck. In this case, the dominant color was red. The oval area of spared skin was created by the shade of the patient’s chin.

Similar changes can be seen with other conditions, such as poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans, a manifestation of small plaque parapsoriasis. However, this typically affects areas below the waist and does not have areas of sparing.

Treatment has been attempted with lasers and peels, yielding mixed success. Because of her condition’s benignancy, this patient did not opt for treatment.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Poikiloderma of Civatte (PC) is a permanent skin change caused by overexposure to the sun or another UV source; it is more common in women than men.

- PC manifests with mottled hyper- or hypopigmented patches of skin on the anterior neck and upper chest, which develop gradually over the course of decades. Many patients also have sheets of telangiectasias covering the affected area.

- A distinct area of sparing (usually oval) is typically seen on the upper anterior neck, due to the chin’s shading of this area.

- Laser treatment has been somewhat successful in lightening the affected skin.

This 58-year-old woman was unaware there was a problem with her neck skin until friends took a picture and showed it to her. She was surprised and distressed, thinking the changes were new and therefore representative of serious disease.

She denies having any associated symptoms but does admit to a great deal of sun exposure over the years. Her history is significant for a basal cell carcinoma, removed from her chest many years ago. She also has a history of smoking and early COPD.

EXAMINATION

A solid sheet of fine, blanchable telangiectasias spreads across the patient’s upper anterior neck, extending down onto her chest. It spares the skin directly under her chin, leaving an unaffected white oval area.

Elsewhere, the patient has a great deal of dermatoheliosis superimposed on her type II skin, including solar lentigines, weathering, and focal solar elastosis.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This particular pattern of mottled hyper- and hypopigmented skin is a result of overexposure to UV light. The name for this common problem—seen far more commonly in women than in men—is poikiloderma of Civatte (PC). This case is typical in that the changes manifested and progressed so slowly that the patient didn’t notice.

PC can manifest with combinations of red, brown, and yellow discoloration around the neck. In this case, the dominant color was red. The oval area of spared skin was created by the shade of the patient’s chin.

Similar changes can be seen with other conditions, such as poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans, a manifestation of small plaque parapsoriasis. However, this typically affects areas below the waist and does not have areas of sparing.

Treatment has been attempted with lasers and peels, yielding mixed success. Because of her condition’s benignancy, this patient did not opt for treatment.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Poikiloderma of Civatte (PC) is a permanent skin change caused by overexposure to the sun or another UV source; it is more common in women than men.

- PC manifests with mottled hyper- or hypopigmented patches of skin on the anterior neck and upper chest, which develop gradually over the course of decades. Many patients also have sheets of telangiectasias covering the affected area.

- A distinct area of sparing (usually oval) is typically seen on the upper anterior neck, due to the chin’s shading of this area.

- Laser treatment has been somewhat successful in lightening the affected skin.

The Princess and the Pea-sized Nodule

For years, this 33-year-old woman has had a firm, pea-sized nodule on her left upper back. It was never a problem until recently, when it suddenly enlarged and became red, swollen, and tender.

She was prescribed antibiotics (trimethoprim and sulfa) by a provider at her local urgent care center. Dubious of the diagnosis—carbuncle—she sought referral to dermatology.

The patient claims to be in otherwise excellent health, with no history of similar problems. She denies manual manipulation of the lesion.

EXAMINATION

The patient is afebrile and in no distress. On her upper left back is a round, cystic lesion measuring 3.5 cm. It appears swollen and red. The erythema, though impressive, is confined to

the area immediately around the margins. Palpation reveals increased warmth and modest tenderness. A central punctum can be seen in the center of the fluctuant lesion.

After a brief discussion of options, the lesion is incised and drained under sterile conditions with lidocaine and epinephrine. Cheesy, odoriferous material is expressed, effectively flattening the lesion.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Epidermal cysts are utterly common, especially in oil-rich areas such as the upper back. They are often mistakenly called sebaceous cysts; however, true sebaceous cysts are quite rare and contain only pure, clear oil.

When ruptured by trauma, epidermal cysts become inflamed and cheesy material leaks into deep tissues. This activates an immune response in which the body sends out white cells to clean up the leakage—what we call inflammation.

There are many types of cysts (eg, acne cysts, ganglion cysts, Bartholin gland cysts) but none resemble epidermal cysts. Providers often mistake epidermal cysts for carbuncles or boils and may prescribe oral or systemic antibiotics, or incise the cysts and pack the space. The truth is that inflamed epidermal cysts do not represent infection—hence the limited area of redness. By contrast, cellulitis or carbuncle would manifest with tenderness and blush of erythema over the entire area.

The fact that this lesion arose from a longstanding antecedent nodule is consistent with the diagnosis, as are the cheesy, odoriferous contents liberated by incision and drainage. Liberating the contents merely buys the patient relief from the pressure and pain, since the cyst wall is still present and will almost certainly fill up again. The ultimate solution is excision after the emptied cyst has had time to shrink back to its original size, which will minimize the scarring. There is no need to pack such cysts after incision and drainage, though they will continue to drain for a few days.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Epidermal cysts are common, especially in oil-rich areas such as the face, back, chest, and neck.

- Epidermal cysts are often mistakenly called sebaceous cysts, but these are actually quite rare, containing clear sebum (oil) and no cheesy material.

- Even though such inflamed cysts are often mistaken for boils, carbuncles, and abscesses, they have nothing to do with bacteria or infection and therefore do not require antibiotics or packing after incision and drainage.

- For recurrent inflamed cysts, the treatment of choice is complete excision, done only after the cyst has shrunk to its smallest size.

For years, this 33-year-old woman has had a firm, pea-sized nodule on her left upper back. It was never a problem until recently, when it suddenly enlarged and became red, swollen, and tender.

She was prescribed antibiotics (trimethoprim and sulfa) by a provider at her local urgent care center. Dubious of the diagnosis—carbuncle—she sought referral to dermatology.

The patient claims to be in otherwise excellent health, with no history of similar problems. She denies manual manipulation of the lesion.

EXAMINATION

The patient is afebrile and in no distress. On her upper left back is a round, cystic lesion measuring 3.5 cm. It appears swollen and red. The erythema, though impressive, is confined to

the area immediately around the margins. Palpation reveals increased warmth and modest tenderness. A central punctum can be seen in the center of the fluctuant lesion.

After a brief discussion of options, the lesion is incised and drained under sterile conditions with lidocaine and epinephrine. Cheesy, odoriferous material is expressed, effectively flattening the lesion.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Epidermal cysts are utterly common, especially in oil-rich areas such as the upper back. They are often mistakenly called sebaceous cysts; however, true sebaceous cysts are quite rare and contain only pure, clear oil.

When ruptured by trauma, epidermal cysts become inflamed and cheesy material leaks into deep tissues. This activates an immune response in which the body sends out white cells to clean up the leakage—what we call inflammation.

There are many types of cysts (eg, acne cysts, ganglion cysts, Bartholin gland cysts) but none resemble epidermal cysts. Providers often mistake epidermal cysts for carbuncles or boils and may prescribe oral or systemic antibiotics, or incise the cysts and pack the space. The truth is that inflamed epidermal cysts do not represent infection—hence the limited area of redness. By contrast, cellulitis or carbuncle would manifest with tenderness and blush of erythema over the entire area.