User login

A routine day for most turned horrific for others

Friday, Dec. 14, was just another routine day at my office. I had a lighter schedule than usual (which always seems to happen as Christmas approaches), test reports to review, and medications to refill.

Sometime just before the first patient came in, a news bulletin crossed my computer screen about a possible gun incident at a school in Connecticut. I forwarded it on to a few friends, but didn’t think much about it at the time. Becoming numb to random gun violence is an unfortunate part of American life.

I went on with my day. I saw patients. MRI reports were dropped off. I reviewed them, made decisions, and e-mailed my nurse as to what to tell patients. People called in to report side effects, migraines, seizures, and I made changes as needed. I saw more patients.

As the hours went by, more reports came in, each more horrific than the last. At some point it became hard to focus on the patients, but you have to.

You resist the urge to text your kids to make sure they’re okay. Or go get them and take them home. You think about how horrible it must be to be a parent in these situations. You hope it never happens to you. And through it all I refilled scrips for Imitrex, Plavix, and Lamictal, looked at lab results, and went ahead with the daily business of a medical office.

At the end of the day, the final toll was in: 28 dead (including the shooter), 20 of them young children. Even in a land where shootings aren’t even news anymore, this one cracked through. An entire first-grade class wiped out. Christmas presents waiting in attics, never to be opened. A searing image of a young woman in tears, holding a cell phone.

It was 4 o’clock on a Friday afternoon. My last patient was done. My secretary and I shut down the computers, rolled the phones, and left. Both of us had to pick up our kids from school. For us, it was just a normal day. Something to be more thankful for than ever.

And at the same time, the feeling of horror and sorrow is there, for those affected. I wish that I could do something – anything – to turn back the clock and have made Dec. 14 just another boring day for parents in Connecticut, too. But there is the helplessness of knowing I can’t, and that nothing will change.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Friday, Dec. 14, was just another routine day at my office. I had a lighter schedule than usual (which always seems to happen as Christmas approaches), test reports to review, and medications to refill.

Sometime just before the first patient came in, a news bulletin crossed my computer screen about a possible gun incident at a school in Connecticut. I forwarded it on to a few friends, but didn’t think much about it at the time. Becoming numb to random gun violence is an unfortunate part of American life.

I went on with my day. I saw patients. MRI reports were dropped off. I reviewed them, made decisions, and e-mailed my nurse as to what to tell patients. People called in to report side effects, migraines, seizures, and I made changes as needed. I saw more patients.

As the hours went by, more reports came in, each more horrific than the last. At some point it became hard to focus on the patients, but you have to.

You resist the urge to text your kids to make sure they’re okay. Or go get them and take them home. You think about how horrible it must be to be a parent in these situations. You hope it never happens to you. And through it all I refilled scrips for Imitrex, Plavix, and Lamictal, looked at lab results, and went ahead with the daily business of a medical office.

At the end of the day, the final toll was in: 28 dead (including the shooter), 20 of them young children. Even in a land where shootings aren’t even news anymore, this one cracked through. An entire first-grade class wiped out. Christmas presents waiting in attics, never to be opened. A searing image of a young woman in tears, holding a cell phone.

It was 4 o’clock on a Friday afternoon. My last patient was done. My secretary and I shut down the computers, rolled the phones, and left. Both of us had to pick up our kids from school. For us, it was just a normal day. Something to be more thankful for than ever.

And at the same time, the feeling of horror and sorrow is there, for those affected. I wish that I could do something – anything – to turn back the clock and have made Dec. 14 just another boring day for parents in Connecticut, too. But there is the helplessness of knowing I can’t, and that nothing will change.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Friday, Dec. 14, was just another routine day at my office. I had a lighter schedule than usual (which always seems to happen as Christmas approaches), test reports to review, and medications to refill.

Sometime just before the first patient came in, a news bulletin crossed my computer screen about a possible gun incident at a school in Connecticut. I forwarded it on to a few friends, but didn’t think much about it at the time. Becoming numb to random gun violence is an unfortunate part of American life.

I went on with my day. I saw patients. MRI reports were dropped off. I reviewed them, made decisions, and e-mailed my nurse as to what to tell patients. People called in to report side effects, migraines, seizures, and I made changes as needed. I saw more patients.

As the hours went by, more reports came in, each more horrific than the last. At some point it became hard to focus on the patients, but you have to.

You resist the urge to text your kids to make sure they’re okay. Or go get them and take them home. You think about how horrible it must be to be a parent in these situations. You hope it never happens to you. And through it all I refilled scrips for Imitrex, Plavix, and Lamictal, looked at lab results, and went ahead with the daily business of a medical office.

At the end of the day, the final toll was in: 28 dead (including the shooter), 20 of them young children. Even in a land where shootings aren’t even news anymore, this one cracked through. An entire first-grade class wiped out. Christmas presents waiting in attics, never to be opened. A searing image of a young woman in tears, holding a cell phone.

It was 4 o’clock on a Friday afternoon. My last patient was done. My secretary and I shut down the computers, rolled the phones, and left. Both of us had to pick up our kids from school. For us, it was just a normal day. Something to be more thankful for than ever.

And at the same time, the feeling of horror and sorrow is there, for those affected. I wish that I could do something – anything – to turn back the clock and have made Dec. 14 just another boring day for parents in Connecticut, too. But there is the helplessness of knowing I can’t, and that nothing will change.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Agreeing to disagree

Recently, I encountered a physician who was surprised that other doctors hadn’t voted the same way he did in the election. He felt that one candidate had been so clearly the obvious choice for physicians that it didn’t make sense that others voted differently.

Generalizations like this are always difficult for me to understand. Perhaps the most remarkable thing about the human brain is how, in spite of it looking quite similar between humans, it produces such strikingly different individuals.

To say all doctors should agree is no different from saying everyone in a certain ethnic group, or religious background, or geographical region should agree. Obviously, if people did all agree, there would be no need for elections at all.

Physicians, like accountants, construction workers, lawyers, teachers, firemen, and nurses, are people from many walks of life. Most of us are in it to help people, but we often disagree on what the best ways are to do so. You’ll see these differences manifest at tumor boards, grand rounds, and nurses stations. So why is it a surprise that they appear in political views, too?

I tend to believe that this diversity is good (as is a polite respect for the opinions of others) because it often leads to finding the best solution using ideas from both sides. In most things, no one is absolutely right or wrong. People – doctors included – are a remarkably heterogeneous group in behaviors and opinions. One paintbrush will never cover all of them, nor should it.

That, like so many other things in our lives, is human nature. And years of medical training will (hopefully) never take that away. I think that’s a good thing.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology private practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Recently, I encountered a physician who was surprised that other doctors hadn’t voted the same way he did in the election. He felt that one candidate had been so clearly the obvious choice for physicians that it didn’t make sense that others voted differently.

Generalizations like this are always difficult for me to understand. Perhaps the most remarkable thing about the human brain is how, in spite of it looking quite similar between humans, it produces such strikingly different individuals.

To say all doctors should agree is no different from saying everyone in a certain ethnic group, or religious background, or geographical region should agree. Obviously, if people did all agree, there would be no need for elections at all.

Physicians, like accountants, construction workers, lawyers, teachers, firemen, and nurses, are people from many walks of life. Most of us are in it to help people, but we often disagree on what the best ways are to do so. You’ll see these differences manifest at tumor boards, grand rounds, and nurses stations. So why is it a surprise that they appear in political views, too?

I tend to believe that this diversity is good (as is a polite respect for the opinions of others) because it often leads to finding the best solution using ideas from both sides. In most things, no one is absolutely right or wrong. People – doctors included – are a remarkably heterogeneous group in behaviors and opinions. One paintbrush will never cover all of them, nor should it.

That, like so many other things in our lives, is human nature. And years of medical training will (hopefully) never take that away. I think that’s a good thing.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology private practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Recently, I encountered a physician who was surprised that other doctors hadn’t voted the same way he did in the election. He felt that one candidate had been so clearly the obvious choice for physicians that it didn’t make sense that others voted differently.

Generalizations like this are always difficult for me to understand. Perhaps the most remarkable thing about the human brain is how, in spite of it looking quite similar between humans, it produces such strikingly different individuals.

To say all doctors should agree is no different from saying everyone in a certain ethnic group, or religious background, or geographical region should agree. Obviously, if people did all agree, there would be no need for elections at all.

Physicians, like accountants, construction workers, lawyers, teachers, firemen, and nurses, are people from many walks of life. Most of us are in it to help people, but we often disagree on what the best ways are to do so. You’ll see these differences manifest at tumor boards, grand rounds, and nurses stations. So why is it a surprise that they appear in political views, too?

I tend to believe that this diversity is good (as is a polite respect for the opinions of others) because it often leads to finding the best solution using ideas from both sides. In most things, no one is absolutely right or wrong. People – doctors included – are a remarkably heterogeneous group in behaviors and opinions. One paintbrush will never cover all of them, nor should it.

That, like so many other things in our lives, is human nature. And years of medical training will (hopefully) never take that away. I think that’s a good thing.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology private practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Costs of the Reformulated Drug 'Alphabet'

Last week I talked about combination pills. But they aren’t the only drug company issue that irritates me.

Alphabet letters are cheap, except in pharmaceuticals. Here the most expensive combinations are XR, ER, CR, XL, SR, and a few others.

Most patients can remember to take their medications twice a day (three times a day, I admit, can be an issue). But that hasn’t stopped drug companies from trying to mine gold out of these letters.

Many drugs are twice-daily. And it’s almost a sure bet that when their patent life dwindles down to a few months, the parent company will introduce a once-daily variant with one of these letter combinations tacked on to the name. Of course, this involves a significant price-hike over the generic b.i.d. form.

Just like other "convenience pills," this quickly becomes a financial issue. I always have plenty of samples to give out, but sooner or later a real scrip has to be called in, and that’s when the guano hits the fan. The scrip gets rejected because the insurance company won’t pay for it, the patient is horrified by the cash price and won’t pay for it, and those little copay cards don’t help as much as the drug reps claim (they’re also, in my experience, thoroughly hated by pharmacists).

As with combo pills that I’ve written about previously, QD dosing is nice, but not take-out-a-second-mortgage-to-pay-for-it nice. In these cases, the patient inevitably goes with the b.i.d. generic. The samples become a gateway to try the drug, but sooner or later the real scrip will be for the generic b.i.d. form.

I’m aware that these types of pills are easier to bring to market than an all-new agent. They get marketed with all sorts of hoopla as some sort of miracle breakthrough, but anyone on the prescribing side of the business can see that they’re just repackaging an older drug to squeeze a few more dollars out if it. And, as always, I find myself wondering if the fortune blown on bringing this to market couldn’t have been better spent on something truly new and useful.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology private practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Last week I talked about combination pills. But they aren’t the only drug company issue that irritates me.

Alphabet letters are cheap, except in pharmaceuticals. Here the most expensive combinations are XR, ER, CR, XL, SR, and a few others.

Most patients can remember to take their medications twice a day (three times a day, I admit, can be an issue). But that hasn’t stopped drug companies from trying to mine gold out of these letters.

Many drugs are twice-daily. And it’s almost a sure bet that when their patent life dwindles down to a few months, the parent company will introduce a once-daily variant with one of these letter combinations tacked on to the name. Of course, this involves a significant price-hike over the generic b.i.d. form.

Just like other "convenience pills," this quickly becomes a financial issue. I always have plenty of samples to give out, but sooner or later a real scrip has to be called in, and that’s when the guano hits the fan. The scrip gets rejected because the insurance company won’t pay for it, the patient is horrified by the cash price and won’t pay for it, and those little copay cards don’t help as much as the drug reps claim (they’re also, in my experience, thoroughly hated by pharmacists).

As with combo pills that I’ve written about previously, QD dosing is nice, but not take-out-a-second-mortgage-to-pay-for-it nice. In these cases, the patient inevitably goes with the b.i.d. generic. The samples become a gateway to try the drug, but sooner or later the real scrip will be for the generic b.i.d. form.

I’m aware that these types of pills are easier to bring to market than an all-new agent. They get marketed with all sorts of hoopla as some sort of miracle breakthrough, but anyone on the prescribing side of the business can see that they’re just repackaging an older drug to squeeze a few more dollars out if it. And, as always, I find myself wondering if the fortune blown on bringing this to market couldn’t have been better spent on something truly new and useful.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology private practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Last week I talked about combination pills. But they aren’t the only drug company issue that irritates me.

Alphabet letters are cheap, except in pharmaceuticals. Here the most expensive combinations are XR, ER, CR, XL, SR, and a few others.

Most patients can remember to take their medications twice a day (three times a day, I admit, can be an issue). But that hasn’t stopped drug companies from trying to mine gold out of these letters.

Many drugs are twice-daily. And it’s almost a sure bet that when their patent life dwindles down to a few months, the parent company will introduce a once-daily variant with one of these letter combinations tacked on to the name. Of course, this involves a significant price-hike over the generic b.i.d. form.

Just like other "convenience pills," this quickly becomes a financial issue. I always have plenty of samples to give out, but sooner or later a real scrip has to be called in, and that’s when the guano hits the fan. The scrip gets rejected because the insurance company won’t pay for it, the patient is horrified by the cash price and won’t pay for it, and those little copay cards don’t help as much as the drug reps claim (they’re also, in my experience, thoroughly hated by pharmacists).

As with combo pills that I’ve written about previously, QD dosing is nice, but not take-out-a-second-mortgage-to-pay-for-it nice. In these cases, the patient inevitably goes with the b.i.d. generic. The samples become a gateway to try the drug, but sooner or later the real scrip will be for the generic b.i.d. form.

I’m aware that these types of pills are easier to bring to market than an all-new agent. They get marketed with all sorts of hoopla as some sort of miracle breakthrough, but anyone on the prescribing side of the business can see that they’re just repackaging an older drug to squeeze a few more dollars out if it. And, as always, I find myself wondering if the fortune blown on bringing this to market couldn’t have been better spent on something truly new and useful.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology private practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Convenience at What Price?

Drug companies bring all kinds of miracles to our lives, but it amazes me how many dollars are spent on things that (at least to me) seem to have no profit potential.

My personal peeve is "convenience pills." Recently, I read a news item about a company developing a combination tablet with omeprazole and aspirin – in one pill.

I’m not a marketing person, so I really don’t understand this. Both drugs are available over the counter for pennies per day, and here someone wants to put them in one pill and charge extra for it.

This isn’t the first time it’s been done. Duexis (ibuprofen plus famotidine) is one of several out there. You’d think that finding a new drug would be the goal, rather than recycling new ones. Giving us plenty of samples to start patients on (and those copay cards) doesn’t change the fact that the drug won’t be covered by insurance, and in a week we’ll tell the patient to just buy the individual components.

The people behind these often use the phrase "pill burden" referring to the apparently horrendous difficulties posed by having to take two pills instead of one. I have no idea where they get this idea. Yes, it sounds nice on the surface, but not "costs-$35-more-a-month" nice. Most of my patients are just fine with taking two pills at once, as am I.

I understand the reason they do this: It’s cheaper to reformulate and market drugs that already have been developed and have years of data behind them. This cuts down dramatically on R&D costs. But you still have to sink a fortune into clinical trials, getting Food and Drug Administration approval, and marketing. At the end of all that, I have no idea how they can make a profit when competing with already available generics.

My personality type is such that I don’t argue with the drug reps who come to my office. They didn’t bring it to market. They’re doing their job, just like I’m doing mine. I suspect they know how useless the drug is but (as I often do) remind themselves that they have a family to support.

It’s a free country, and I know you can sell whatever you want (with FDA approval). But I don’t understand what financial incentives there are for companies to do this pharmaceutical recycling. And I probably never will.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology private practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Drug companies bring all kinds of miracles to our lives, but it amazes me how many dollars are spent on things that (at least to me) seem to have no profit potential.

My personal peeve is "convenience pills." Recently, I read a news item about a company developing a combination tablet with omeprazole and aspirin – in one pill.

I’m not a marketing person, so I really don’t understand this. Both drugs are available over the counter for pennies per day, and here someone wants to put them in one pill and charge extra for it.

This isn’t the first time it’s been done. Duexis (ibuprofen plus famotidine) is one of several out there. You’d think that finding a new drug would be the goal, rather than recycling new ones. Giving us plenty of samples to start patients on (and those copay cards) doesn’t change the fact that the drug won’t be covered by insurance, and in a week we’ll tell the patient to just buy the individual components.

The people behind these often use the phrase "pill burden" referring to the apparently horrendous difficulties posed by having to take two pills instead of one. I have no idea where they get this idea. Yes, it sounds nice on the surface, but not "costs-$35-more-a-month" nice. Most of my patients are just fine with taking two pills at once, as am I.

I understand the reason they do this: It’s cheaper to reformulate and market drugs that already have been developed and have years of data behind them. This cuts down dramatically on R&D costs. But you still have to sink a fortune into clinical trials, getting Food and Drug Administration approval, and marketing. At the end of all that, I have no idea how they can make a profit when competing with already available generics.

My personality type is such that I don’t argue with the drug reps who come to my office. They didn’t bring it to market. They’re doing their job, just like I’m doing mine. I suspect they know how useless the drug is but (as I often do) remind themselves that they have a family to support.

It’s a free country, and I know you can sell whatever you want (with FDA approval). But I don’t understand what financial incentives there are for companies to do this pharmaceutical recycling. And I probably never will.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology private practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Drug companies bring all kinds of miracles to our lives, but it amazes me how many dollars are spent on things that (at least to me) seem to have no profit potential.

My personal peeve is "convenience pills." Recently, I read a news item about a company developing a combination tablet with omeprazole and aspirin – in one pill.

I’m not a marketing person, so I really don’t understand this. Both drugs are available over the counter for pennies per day, and here someone wants to put them in one pill and charge extra for it.

This isn’t the first time it’s been done. Duexis (ibuprofen plus famotidine) is one of several out there. You’d think that finding a new drug would be the goal, rather than recycling new ones. Giving us plenty of samples to start patients on (and those copay cards) doesn’t change the fact that the drug won’t be covered by insurance, and in a week we’ll tell the patient to just buy the individual components.

The people behind these often use the phrase "pill burden" referring to the apparently horrendous difficulties posed by having to take two pills instead of one. I have no idea where they get this idea. Yes, it sounds nice on the surface, but not "costs-$35-more-a-month" nice. Most of my patients are just fine with taking two pills at once, as am I.

I understand the reason they do this: It’s cheaper to reformulate and market drugs that already have been developed and have years of data behind them. This cuts down dramatically on R&D costs. But you still have to sink a fortune into clinical trials, getting Food and Drug Administration approval, and marketing. At the end of all that, I have no idea how they can make a profit when competing with already available generics.

My personality type is such that I don’t argue with the drug reps who come to my office. They didn’t bring it to market. They’re doing their job, just like I’m doing mine. I suspect they know how useless the drug is but (as I often do) remind themselves that they have a family to support.

It’s a free country, and I know you can sell whatever you want (with FDA approval). But I don’t understand what financial incentives there are for companies to do this pharmaceutical recycling. And I probably never will.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology private practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Take 'Top Doc' Ratings With a Grain of Salt

Every year, a local magazine publishes its annual "Top Doc" issue. The rankings are based on voting conducted by local physicians.

I’ve been on the list several times over the years. I’m flattered, as anyone would be. But I always worry about patients who put too much faith in these things. I know many good doctors who have never been on the list, and I know some people on the list who are adequate at best.

A handful of people each year come in solely on the magazine’s referral. Most are chronic pain patients, who don’t come back after learning that I don’t have any miracle treatments that their previous doctors didn’t have. My casual sense of fashion also puts them off, as they seem to expect me to be wearing a three-piece suit – with a cape.

Ratings are tricky. Having other doctors do them is likely more reliable than asking patients, but still misses a key point of the doctor-patient relationship: chemistry. The bottom line is that some people click very well together and others don’t. This sort of thing is often hard to predict, and no matter how good a doctor you may be, if patients don’t like you, they probably won’t be back. They also may complain to their internist about you.

I once made it onto a similar list (in a now-defunct throwaway magazine) as the second-best doctor in Scottsdale. (I think the first was a pediatrician.) The rating wasn’t even broken down by specialty, so having a neurologist so high up was unusual. It was, as best I could tell, based on random phone calls made during daytime hours to houses in zip codes surrounding my office. I can only assume it was a remarkably skewed, non-scientific sample, and that many of my patients were home that day. I don\'t remember getting any referrals from that, and the magazine folded within a year.

The only thing I’d say is truly predictable is that after the annual "Top Doc" issue comes out, people call asking for my money: companies selling plaques or statues to commemorate the achievement, financial planners wanting to discuss my portfolio, and the occasional reporter wanting me to comment on a story. I turn them all away. I don’t even hang up my own diplomas, so I have no interest in more tchotchkes. I may not be a financial planner, but in this era I am reluctant to trust others with my money. And I hide from the general media.

In any profession, rating people is never easy. There are a lot of variables, and some things simply can’t be predicted. It’s flattering to be on the lists, but just like betting guides at a sports book, they need to be taken with a grain of salt.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology private practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Every year, a local magazine publishes its annual "Top Doc" issue. The rankings are based on voting conducted by local physicians.

I’ve been on the list several times over the years. I’m flattered, as anyone would be. But I always worry about patients who put too much faith in these things. I know many good doctors who have never been on the list, and I know some people on the list who are adequate at best.

A handful of people each year come in solely on the magazine’s referral. Most are chronic pain patients, who don’t come back after learning that I don’t have any miracle treatments that their previous doctors didn’t have. My casual sense of fashion also puts them off, as they seem to expect me to be wearing a three-piece suit – with a cape.

Ratings are tricky. Having other doctors do them is likely more reliable than asking patients, but still misses a key point of the doctor-patient relationship: chemistry. The bottom line is that some people click very well together and others don’t. This sort of thing is often hard to predict, and no matter how good a doctor you may be, if patients don’t like you, they probably won’t be back. They also may complain to their internist about you.

I once made it onto a similar list (in a now-defunct throwaway magazine) as the second-best doctor in Scottsdale. (I think the first was a pediatrician.) The rating wasn’t even broken down by specialty, so having a neurologist so high up was unusual. It was, as best I could tell, based on random phone calls made during daytime hours to houses in zip codes surrounding my office. I can only assume it was a remarkably skewed, non-scientific sample, and that many of my patients were home that day. I don\'t remember getting any referrals from that, and the magazine folded within a year.

The only thing I’d say is truly predictable is that after the annual "Top Doc" issue comes out, people call asking for my money: companies selling plaques or statues to commemorate the achievement, financial planners wanting to discuss my portfolio, and the occasional reporter wanting me to comment on a story. I turn them all away. I don’t even hang up my own diplomas, so I have no interest in more tchotchkes. I may not be a financial planner, but in this era I am reluctant to trust others with my money. And I hide from the general media.

In any profession, rating people is never easy. There are a lot of variables, and some things simply can’t be predicted. It’s flattering to be on the lists, but just like betting guides at a sports book, they need to be taken with a grain of salt.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology private practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Every year, a local magazine publishes its annual "Top Doc" issue. The rankings are based on voting conducted by local physicians.

I’ve been on the list several times over the years. I’m flattered, as anyone would be. But I always worry about patients who put too much faith in these things. I know many good doctors who have never been on the list, and I know some people on the list who are adequate at best.

A handful of people each year come in solely on the magazine’s referral. Most are chronic pain patients, who don’t come back after learning that I don’t have any miracle treatments that their previous doctors didn’t have. My casual sense of fashion also puts them off, as they seem to expect me to be wearing a three-piece suit – with a cape.

Ratings are tricky. Having other doctors do them is likely more reliable than asking patients, but still misses a key point of the doctor-patient relationship: chemistry. The bottom line is that some people click very well together and others don’t. This sort of thing is often hard to predict, and no matter how good a doctor you may be, if patients don’t like you, they probably won’t be back. They also may complain to their internist about you.

I once made it onto a similar list (in a now-defunct throwaway magazine) as the second-best doctor in Scottsdale. (I think the first was a pediatrician.) The rating wasn’t even broken down by specialty, so having a neurologist so high up was unusual. It was, as best I could tell, based on random phone calls made during daytime hours to houses in zip codes surrounding my office. I can only assume it was a remarkably skewed, non-scientific sample, and that many of my patients were home that day. I don\'t remember getting any referrals from that, and the magazine folded within a year.

The only thing I’d say is truly predictable is that after the annual "Top Doc" issue comes out, people call asking for my money: companies selling plaques or statues to commemorate the achievement, financial planners wanting to discuss my portfolio, and the occasional reporter wanting me to comment on a story. I turn them all away. I don’t even hang up my own diplomas, so I have no interest in more tchotchkes. I may not be a financial planner, but in this era I am reluctant to trust others with my money. And I hide from the general media.

In any profession, rating people is never easy. There are a lot of variables, and some things simply can’t be predicted. It’s flattering to be on the lists, but just like betting guides at a sports book, they need to be taken with a grain of salt.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology private practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Time Limitations Make Saying 'No' Easier With Age

Back in residency, I needed my glasses prescription checked and went to see a family friend who was an ophthalmologist. On the opposite end of the scale from me, he was nearing retirement, and we discussed medical practice in general.

One comment he made was that the hardest thing to learn to do in medicine was saying no. He related that, when younger, he used to try and do hospital consults when needed, but as the years had gone by, he gradually faded out of them.

Over time, this has really turned out to be true in many ways. When you first start out, you want to make everyone – both patients and other doctors – happy. You need the work, too. You gladly take whatever hospital consults come your way. You fill out boatloads of forms. You do work-ins for any doctor who asks.

Years go by. As your practice grows, so do your time limitations (both personal and professional). You turn away more hospital work (although it pains you to do it). You only do work-ins for a handful of favored physicians.

Patients are always bringing in forms. I used to do a lot of them. Now, for many (at least those that require me to rate physical capabilities), I just send them back with a note saying that I can’t judge this because of the small size of my practice and to instead see someone who does.

I’ve been doing this since 1998. I’ve been an attending for longer than I was in college, medical school, and residency combined. Now, my hospital work is limited to just my established patients who show up at the hospital next door to me. Work-ins? I still do them, but I can count on both hands the number of doctors I’m willing to do them for.

Saying no – to both doctors and patients – becomes easier with time. But it still hurts a little when turning away a new patient. After all, I got into this business to help people, and it bothers me to say "no" when asked to do so. But there are only so many hours in a day, and now I’d rather give the leftover time to my family.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology private practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Back in residency, I needed my glasses prescription checked and went to see a family friend who was an ophthalmologist. On the opposite end of the scale from me, he was nearing retirement, and we discussed medical practice in general.

One comment he made was that the hardest thing to learn to do in medicine was saying no. He related that, when younger, he used to try and do hospital consults when needed, but as the years had gone by, he gradually faded out of them.

Over time, this has really turned out to be true in many ways. When you first start out, you want to make everyone – both patients and other doctors – happy. You need the work, too. You gladly take whatever hospital consults come your way. You fill out boatloads of forms. You do work-ins for any doctor who asks.

Years go by. As your practice grows, so do your time limitations (both personal and professional). You turn away more hospital work (although it pains you to do it). You only do work-ins for a handful of favored physicians.

Patients are always bringing in forms. I used to do a lot of them. Now, for many (at least those that require me to rate physical capabilities), I just send them back with a note saying that I can’t judge this because of the small size of my practice and to instead see someone who does.

I’ve been doing this since 1998. I’ve been an attending for longer than I was in college, medical school, and residency combined. Now, my hospital work is limited to just my established patients who show up at the hospital next door to me. Work-ins? I still do them, but I can count on both hands the number of doctors I’m willing to do them for.

Saying no – to both doctors and patients – becomes easier with time. But it still hurts a little when turning away a new patient. After all, I got into this business to help people, and it bothers me to say "no" when asked to do so. But there are only so many hours in a day, and now I’d rather give the leftover time to my family.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology private practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Back in residency, I needed my glasses prescription checked and went to see a family friend who was an ophthalmologist. On the opposite end of the scale from me, he was nearing retirement, and we discussed medical practice in general.

One comment he made was that the hardest thing to learn to do in medicine was saying no. He related that, when younger, he used to try and do hospital consults when needed, but as the years had gone by, he gradually faded out of them.

Over time, this has really turned out to be true in many ways. When you first start out, you want to make everyone – both patients and other doctors – happy. You need the work, too. You gladly take whatever hospital consults come your way. You fill out boatloads of forms. You do work-ins for any doctor who asks.

Years go by. As your practice grows, so do your time limitations (both personal and professional). You turn away more hospital work (although it pains you to do it). You only do work-ins for a handful of favored physicians.

Patients are always bringing in forms. I used to do a lot of them. Now, for many (at least those that require me to rate physical capabilities), I just send them back with a note saying that I can’t judge this because of the small size of my practice and to instead see someone who does.

I’ve been doing this since 1998. I’ve been an attending for longer than I was in college, medical school, and residency combined. Now, my hospital work is limited to just my established patients who show up at the hospital next door to me. Work-ins? I still do them, but I can count on both hands the number of doctors I’m willing to do them for.

Saying no – to both doctors and patients – becomes easier with time. But it still hurts a little when turning away a new patient. After all, I got into this business to help people, and it bothers me to say "no" when asked to do so. But there are only so many hours in a day, and now I’d rather give the leftover time to my family.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology private practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

No-Shows Are No Fun

No-show patients who don’t come for an appointment – leaving you with an empty time slot – are one of the most frustrating things we deal with.

There are plenty of good reasons to no-show: flat tires, illness, and last-minute things at work. I don’t mind those too much, especially when patients have the decency to call in, even at the last minute or afterward, to apologize and let me know. Those things happen to all of us. Sometimes even the fault is with our scheduling and not the patient.

But the really frustrating ones are the ones who just don’t show up, especially when they’re new patients and you’ve booked out an hour.

I can always use the time. Certainly, there’s never any shortage of stuff in a modern practice: dictations to be done, test results to review, refills to okay, and the endless forms of varying types. But it still doesn’t change the fact that it’s an hour you’re taking a financial loss on. My wife uses the phrase that "butts in seats" is what pays the bills in an office practice, and I can’t argue with that.

Predictably, I’m not very forgiving toward them. An established patient who forgets an appointment here and there I generally don’t punish, but a new one without a damn good reason gets my wrath. Most never call in, but the ones that do I usually won’t reschedule.

When I first started out I took 20 or so different insurance companies. After a few years I did an analysis, and found one insurance company accounted for nearly 50% of my no-shows. I dropped it, and this brought down the rate quite a bit. But they still happen and are unavoidable.

Even so, there are some days where a confluence of no-shows can leave you with an empty schedule, scratching your head and trying to use the extra time productively (as opposed to watching Monty Python on YouTube).

Dr. Block has a solo neurology private practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

No-show patients who don’t come for an appointment – leaving you with an empty time slot – are one of the most frustrating things we deal with.

There are plenty of good reasons to no-show: flat tires, illness, and last-minute things at work. I don’t mind those too much, especially when patients have the decency to call in, even at the last minute or afterward, to apologize and let me know. Those things happen to all of us. Sometimes even the fault is with our scheduling and not the patient.

But the really frustrating ones are the ones who just don’t show up, especially when they’re new patients and you’ve booked out an hour.

I can always use the time. Certainly, there’s never any shortage of stuff in a modern practice: dictations to be done, test results to review, refills to okay, and the endless forms of varying types. But it still doesn’t change the fact that it’s an hour you’re taking a financial loss on. My wife uses the phrase that "butts in seats" is what pays the bills in an office practice, and I can’t argue with that.

Predictably, I’m not very forgiving toward them. An established patient who forgets an appointment here and there I generally don’t punish, but a new one without a damn good reason gets my wrath. Most never call in, but the ones that do I usually won’t reschedule.

When I first started out I took 20 or so different insurance companies. After a few years I did an analysis, and found one insurance company accounted for nearly 50% of my no-shows. I dropped it, and this brought down the rate quite a bit. But they still happen and are unavoidable.

Even so, there are some days where a confluence of no-shows can leave you with an empty schedule, scratching your head and trying to use the extra time productively (as opposed to watching Monty Python on YouTube).

Dr. Block has a solo neurology private practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

No-show patients who don’t come for an appointment – leaving you with an empty time slot – are one of the most frustrating things we deal with.

There are plenty of good reasons to no-show: flat tires, illness, and last-minute things at work. I don’t mind those too much, especially when patients have the decency to call in, even at the last minute or afterward, to apologize and let me know. Those things happen to all of us. Sometimes even the fault is with our scheduling and not the patient.

But the really frustrating ones are the ones who just don’t show up, especially when they’re new patients and you’ve booked out an hour.

I can always use the time. Certainly, there’s never any shortage of stuff in a modern practice: dictations to be done, test results to review, refills to okay, and the endless forms of varying types. But it still doesn’t change the fact that it’s an hour you’re taking a financial loss on. My wife uses the phrase that "butts in seats" is what pays the bills in an office practice, and I can’t argue with that.

Predictably, I’m not very forgiving toward them. An established patient who forgets an appointment here and there I generally don’t punish, but a new one without a damn good reason gets my wrath. Most never call in, but the ones that do I usually won’t reschedule.

When I first started out I took 20 or so different insurance companies. After a few years I did an analysis, and found one insurance company accounted for nearly 50% of my no-shows. I dropped it, and this brought down the rate quite a bit. But they still happen and are unavoidable.

Even so, there are some days where a confluence of no-shows can leave you with an empty schedule, scratching your head and trying to use the extra time productively (as opposed to watching Monty Python on YouTube).

Dr. Block has a solo neurology private practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Keeping Politics Out of the Office

I try very hard not to discuss politics with patients. Politics are always flammable.

I respect everyone’s right to an opinion, and certainly don’t treat them any different, regardless of what it is. But, in my experience, it’s simply best not to know.

So when patients ask me who I’m voting for, I generally tell them I don’t discuss such issues in my practice. Some doctors will say I’m missing an opportunity to educate them about important issues, such as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, but I take the view that such isn’t my job.

I’m here to provide medical care and education about their condition. Discussions about politics, no matter how well intended, can often lead beyond polite disagreements to anger or resentment – elements that are never good things in the doctor-patient relationship.

When I was a younger doctor, once a week I’d work at a prisoner clinic. It was strictly forbidden to ask what the person was in for, on the same grounds: If it was, say, a child molester, would that alter the care you’d provide? Maybe, maybe not. We are all human, and it’s not easy to remain objective when dealing with someone who might disgust you.

Objectivity is a critical element in patient care. It’s the same reason we (generally) try not to treat family members or friends. Once you lose it, the relationship can’t be returned to its previous level. So it’s best not to start at all.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology private practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I try very hard not to discuss politics with patients. Politics are always flammable.

I respect everyone’s right to an opinion, and certainly don’t treat them any different, regardless of what it is. But, in my experience, it’s simply best not to know.

So when patients ask me who I’m voting for, I generally tell them I don’t discuss such issues in my practice. Some doctors will say I’m missing an opportunity to educate them about important issues, such as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, but I take the view that such isn’t my job.

I’m here to provide medical care and education about their condition. Discussions about politics, no matter how well intended, can often lead beyond polite disagreements to anger or resentment – elements that are never good things in the doctor-patient relationship.

When I was a younger doctor, once a week I’d work at a prisoner clinic. It was strictly forbidden to ask what the person was in for, on the same grounds: If it was, say, a child molester, would that alter the care you’d provide? Maybe, maybe not. We are all human, and it’s not easy to remain objective when dealing with someone who might disgust you.

Objectivity is a critical element in patient care. It’s the same reason we (generally) try not to treat family members or friends. Once you lose it, the relationship can’t be returned to its previous level. So it’s best not to start at all.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology private practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I try very hard not to discuss politics with patients. Politics are always flammable.

I respect everyone’s right to an opinion, and certainly don’t treat them any different, regardless of what it is. But, in my experience, it’s simply best not to know.

So when patients ask me who I’m voting for, I generally tell them I don’t discuss such issues in my practice. Some doctors will say I’m missing an opportunity to educate them about important issues, such as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, but I take the view that such isn’t my job.

I’m here to provide medical care and education about their condition. Discussions about politics, no matter how well intended, can often lead beyond polite disagreements to anger or resentment – elements that are never good things in the doctor-patient relationship.

When I was a younger doctor, once a week I’d work at a prisoner clinic. It was strictly forbidden to ask what the person was in for, on the same grounds: If it was, say, a child molester, would that alter the care you’d provide? Maybe, maybe not. We are all human, and it’s not easy to remain objective when dealing with someone who might disgust you.

Objectivity is a critical element in patient care. It’s the same reason we (generally) try not to treat family members or friends. Once you lose it, the relationship can’t be returned to its previous level. So it’s best not to start at all.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology private practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Staying Away From Professional Organizations

I don’t belong to any organizations. Not one. I’m not saying this to brag, nor do I claim to be a rebel. It’s just the way it is.

When I was in residency, and later fellowship, my department paid for my membership. So I was in the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. I got some nice department-funded trips for meetings and a subscription to the thick green journal. I tried to keep up on the reading, but the pile eventually won and ended up in a recycling bin when I moved.

I’m not an academic and never will be. I have nothing against those who are, but it’s just not my thing. So joining various medical associations for contacts and publications doesn’t serve me in that regard. I don’t conduct research, either. And I do my own continuing medical education from various free sources.

I don’t have time to go to meetings anymore. Some will argue that they’re tax deductible, but I don’t care. If I’m going to spend money on a trip, I’d rather spend the whole time with my family and relax. In the "eat what you kill" world of solo practice, taking time off is a financial hit. So I try to limit it to important things, such as family.

Financial realities can also lead you away from organizations. Most annual memberships are several hundred dollars, which seems like a big chunk of change for a journal you don’t have time to read, annual meetings you don’t have time to go to (and which can cost a fortune when added up), and a membership card for your wallet. I’m sure others will argue that organizations serve purposes of CME and political representation, but at this point in my life I get all my own CME anyway, and I am skeptical about the latter.

So I save my time and money for things that are more important to me. Memberships in big organizations aren’t on the list.

Besides, as Groucho Marx once said, "I don’t care to belong to any club that will have me as a member."

I don’t belong to any organizations. Not one. I’m not saying this to brag, nor do I claim to be a rebel. It’s just the way it is.

When I was in residency, and later fellowship, my department paid for my membership. So I was in the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. I got some nice department-funded trips for meetings and a subscription to the thick green journal. I tried to keep up on the reading, but the pile eventually won and ended up in a recycling bin when I moved.

I’m not an academic and never will be. I have nothing against those who are, but it’s just not my thing. So joining various medical associations for contacts and publications doesn’t serve me in that regard. I don’t conduct research, either. And I do my own continuing medical education from various free sources.

I don’t have time to go to meetings anymore. Some will argue that they’re tax deductible, but I don’t care. If I’m going to spend money on a trip, I’d rather spend the whole time with my family and relax. In the "eat what you kill" world of solo practice, taking time off is a financial hit. So I try to limit it to important things, such as family.

Financial realities can also lead you away from organizations. Most annual memberships are several hundred dollars, which seems like a big chunk of change for a journal you don’t have time to read, annual meetings you don’t have time to go to (and which can cost a fortune when added up), and a membership card for your wallet. I’m sure others will argue that organizations serve purposes of CME and political representation, but at this point in my life I get all my own CME anyway, and I am skeptical about the latter.

So I save my time and money for things that are more important to me. Memberships in big organizations aren’t on the list.

Besides, as Groucho Marx once said, "I don’t care to belong to any club that will have me as a member."

I don’t belong to any organizations. Not one. I’m not saying this to brag, nor do I claim to be a rebel. It’s just the way it is.

When I was in residency, and later fellowship, my department paid for my membership. So I was in the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. I got some nice department-funded trips for meetings and a subscription to the thick green journal. I tried to keep up on the reading, but the pile eventually won and ended up in a recycling bin when I moved.

I’m not an academic and never will be. I have nothing against those who are, but it’s just not my thing. So joining various medical associations for contacts and publications doesn’t serve me in that regard. I don’t conduct research, either. And I do my own continuing medical education from various free sources.

I don’t have time to go to meetings anymore. Some will argue that they’re tax deductible, but I don’t care. If I’m going to spend money on a trip, I’d rather spend the whole time with my family and relax. In the "eat what you kill" world of solo practice, taking time off is a financial hit. So I try to limit it to important things, such as family.

Financial realities can also lead you away from organizations. Most annual memberships are several hundred dollars, which seems like a big chunk of change for a journal you don’t have time to read, annual meetings you don’t have time to go to (and which can cost a fortune when added up), and a membership card for your wallet. I’m sure others will argue that organizations serve purposes of CME and political representation, but at this point in my life I get all my own CME anyway, and I am skeptical about the latter.

So I save my time and money for things that are more important to me. Memberships in big organizations aren’t on the list.

Besides, as Groucho Marx once said, "I don’t care to belong to any club that will have me as a member."

Where Do Your Diplomas Reside?

I have a lot of stuff up on my office walls: pictures my kids drew, favorite quotes, a few cartoons, two M.C. Escher prints, a Lego Batman figure ... and absolutely no diplomas.

I have no idea when the tradition of doctors hanging up diplomas started. I assume it was quite a while ago.

Some doctors just put up a medical school diploma, but most also have them from college, residency, and fellowship. I’ve even known a few who hung up high school and grade school diplomas, with as many continuing medical education certificates as they could find. Not me.

Maybe it’s just a complete lack of ego for this sort of thing on my part. I know I went through all the training, and I don’t need to remind myself.

I also don’t see the point of hanging them up for patients. At this point in history, most of them have seen my picture online, skimmed my website, and probably read my online reviews (in spite of which, they’re coming to me). So if they still question my qualifications, I don’t think having (or not having) a diploma up is going to convince them.

My office partner has his diplomas up in the main hallway. He’s 25 years older than I am, yet that doesn’t stop my patients from looking them over, not paying attention to the name on them, and commenting about how good I look for my age. (Okay, I suppose there’s a reason they’re seeing a neurologist.) It does, however, make me wonder how much attention anyone really pays to these things.

I’m guessing a lot of doctors display their diplomas for pride. You paid a fortune and invested several years in that piece of paper, and you want the world to see it. But at this point in my life and career, the pictures my kids drew for me have a lot more meaning. And because I spend most of my waking workdays in that room, I’d rather be looking at them.

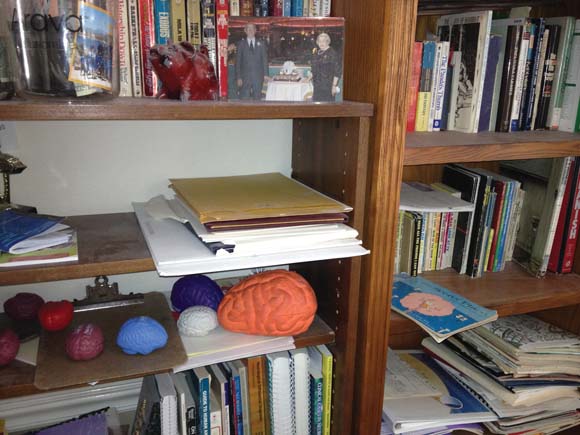

For the record, my diplomas (all unframed) are neatly stacked on a dusty bookshelf in my home office. They lie under a shelf of paperbacks, my daughter’s money jar, an old piggy bank, and a picture of my late grandparents. They are above a shelf covered with foam-rubber brains I used to collect from drug companies and next to a plastic trophy of a ship I won in a trivia contest.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology private practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I have a lot of stuff up on my office walls: pictures my kids drew, favorite quotes, a few cartoons, two M.C. Escher prints, a Lego Batman figure ... and absolutely no diplomas.

I have no idea when the tradition of doctors hanging up diplomas started. I assume it was quite a while ago.

Some doctors just put up a medical school diploma, but most also have them from college, residency, and fellowship. I’ve even known a few who hung up high school and grade school diplomas, with as many continuing medical education certificates as they could find. Not me.

Maybe it’s just a complete lack of ego for this sort of thing on my part. I know I went through all the training, and I don’t need to remind myself.

I also don’t see the point of hanging them up for patients. At this point in history, most of them have seen my picture online, skimmed my website, and probably read my online reviews (in spite of which, they’re coming to me). So if they still question my qualifications, I don’t think having (or not having) a diploma up is going to convince them.

My office partner has his diplomas up in the main hallway. He’s 25 years older than I am, yet that doesn’t stop my patients from looking them over, not paying attention to the name on them, and commenting about how good I look for my age. (Okay, I suppose there’s a reason they’re seeing a neurologist.) It does, however, make me wonder how much attention anyone really pays to these things.

I’m guessing a lot of doctors display their diplomas for pride. You paid a fortune and invested several years in that piece of paper, and you want the world to see it. But at this point in my life and career, the pictures my kids drew for me have a lot more meaning. And because I spend most of my waking workdays in that room, I’d rather be looking at them.

For the record, my diplomas (all unframed) are neatly stacked on a dusty bookshelf in my home office. They lie under a shelf of paperbacks, my daughter’s money jar, an old piggy bank, and a picture of my late grandparents. They are above a shelf covered with foam-rubber brains I used to collect from drug companies and next to a plastic trophy of a ship I won in a trivia contest.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology private practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I have a lot of stuff up on my office walls: pictures my kids drew, favorite quotes, a few cartoons, two M.C. Escher prints, a Lego Batman figure ... and absolutely no diplomas.

I have no idea when the tradition of doctors hanging up diplomas started. I assume it was quite a while ago.

Some doctors just put up a medical school diploma, but most also have them from college, residency, and fellowship. I’ve even known a few who hung up high school and grade school diplomas, with as many continuing medical education certificates as they could find. Not me.

Maybe it’s just a complete lack of ego for this sort of thing on my part. I know I went through all the training, and I don’t need to remind myself.

I also don’t see the point of hanging them up for patients. At this point in history, most of them have seen my picture online, skimmed my website, and probably read my online reviews (in spite of which, they’re coming to me). So if they still question my qualifications, I don’t think having (or not having) a diploma up is going to convince them.

My office partner has his diplomas up in the main hallway. He’s 25 years older than I am, yet that doesn’t stop my patients from looking them over, not paying attention to the name on them, and commenting about how good I look for my age. (Okay, I suppose there’s a reason they’re seeing a neurologist.) It does, however, make me wonder how much attention anyone really pays to these things.

I’m guessing a lot of doctors display their diplomas for pride. You paid a fortune and invested several years in that piece of paper, and you want the world to see it. But at this point in my life and career, the pictures my kids drew for me have a lot more meaning. And because I spend most of my waking workdays in that room, I’d rather be looking at them.

For the record, my diplomas (all unframed) are neatly stacked on a dusty bookshelf in my home office. They lie under a shelf of paperbacks, my daughter’s money jar, an old piggy bank, and a picture of my late grandparents. They are above a shelf covered with foam-rubber brains I used to collect from drug companies and next to a plastic trophy of a ship I won in a trivia contest.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology private practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.