User login

A Veteran With Alcohol Use Disorder and Acute Pancreatitis

Case Presentation. A 23-year-old male U.S. Army veteran with a history of alcohol use disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) presented to the VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) West Roxbury campus emergency department (ED) with epigastric abdominal pain in the setting of consuming alcohol. The patient had served in the infantry in Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom. He consumed up to 12 alcoholic drinks per day (both beer and hard liquor) for the past 3 years and had been hospitalized 3 times previously; twice for alcohol detoxification and once for PTSD. He is a former tobacco smoker with fewer than 5 pack-years, he uses marijuana often and does not use IV drugs. In the ED, his physical examination was notable for a heart rate of 130 beats per minute and blood pressure of 161/111 mm Hg. He was alert and oriented and had a mild tremor. The patient was diaphoretic with dry mucous membranes, tenderness to palpation in the epigastrium, and abdominal guarding. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen revealed acute pancreatitis without necrosis. The patient received 1 L of normal saline and was admitted to the medical ward for presumed alcoholic pancreatitis.

► Rahul Ganatra, MD, MPH, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Dr. Weber, we care for many young people who drink more than they should and almost none of them end up with alcoholic pancreatitis. What are the relevant risk factors that make individuals like this patient more susceptible to alcoholic pancreatitis?

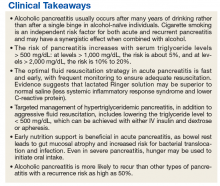

►Horst Christian Weber, MD, Gastroenterology Service, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. While we don’t have a good understanding of the precise mechanism of alcoholic pancreatitis, we do know that in the U.S., alcohol consumption is responsible for about one-third of all cases.1 Acute pancreatitis in general may present with a wide range of disease severity. It is the most common cause of gastrointestinal-related hospitalization,2 and the mortality of hospital inpatients with pancreatitis is about 5%.3,4 Therefore, acute pancreatitis represents a prevalent condition with a critical impact on morbidity and mortality. Alcoholic pancreatitis typically occurs after many years of heavy alcohol use, not after a single drinking

► Dr. Ganatra. At this point, the chemistry laboratory paged the admitting resident with the notification that the patient’s blood was grossly lipemic. Ultracentrifugation was performed to separate the lipid layer and his laboratory values result (Table). Notable abnormalities included polycythemia with a hemoglobin of 17.4 g/dL, hyponatremia with a sodium of 129 mmol/L, normal renal function, elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (AST 258 IU/L and ALT 153 IU/L, respectively), hyperbilirubinemia with a total bilirubin of 2.7 mg/dL, and a serum alcohol level of 147 mg/dL. Due to anticipated requirement for a higher level of care, the patient was transferred to the Medical Intensive Care Unit (MICU).

Dr. Breu, can you help us interpret this patient’s numerous laboratory abnormalities? Without yet having the triglyceride level available, how does the fact that the patient’s blood was lipemic affect our interpretation of his labs? What further workup is warranted?

► Anthony Breu, MD, Medical Service, VABHS, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School. First, the positive alcohol level confirms a recent ingestion. Second, he has elevated transaminases with the AST greater than the ALT, which is consistent with alcoholic liver disease. While the initial assumption is that this patient has alcohol-induced pancreatitis, the elevations in bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase may suggest gallstone pancreatitis, and the lipemic appearing serum could suggest triglyceride-mediated pancreatitis. If the patient does have elevated triglyceride levels, the sodium level may indicate pseudohyponatremia, a laboratory artifact seen if a dilution step is used. To further evaluate the patient, I would obtain a triglyceride level and a right upper quadrant ultrasound. Direct ion-selective electrode analysis of the sodium level can be done with a device used to measure blood gases to exclude pseudohyponatremia.

► Dr. Ganatra. A right upper quadrant ultrasound was obtained in the MICU, which showed hepatic steatosis and hepatomegaly to 19 cm, but no evidence of biliary obstruction by stones or sludge. The common bile duct measured 3.2 mm in diameter. A triglyceride level returned above assay at > 3,392 mg/dL. A review of the medical record revealed a triglyceride level of 105 mg/dL 16 months prior. The Gastroenterology Department was consulted.

Dr. Weber, we now have 2 etiologies for pancreatitis in this patient: alcohol and hypertriglyceridemia. How do each cause pancreatitis? Is it possible to determine in this case which one is the more likely driver?

► Dr. Weber. The mechanism for alcohol-induced pancreatitis is not fully known, but there are several hypotheses. One is that alcohol may increase the synthesis or activation of pancreatic digestive enzymes.6 Another is that metabolites of alcohol are directly toxic to the pancreas.6 Based on the epidemiologic observation that alcoholic pancreatitis usually happens in long-standing users, all we can say is that it is not very likely to be the effect of an acute insult. For hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis, we believe the injury is due to the toxic effect of free fatty acids in the pancreas liberated by lipolysis of triglycerides by pancreatic lipases. Higher triglycerides are associated with higher risk, suggesting a dose-response relationship: This risk is not greatly increased until triglycerides exceed 500 mg/dL; above 1,000 mg/dL, the risk is about 5%, and above 2,000 mg/dL, the risk is between 10% and 20%.7 In summary, we cannot really determine whether the alcohol or the triglycerides are the main cause of his pancreatitis, but given his markedly elevated triglycerides, he should be treated for hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis.

►Dr. Ganatra. Dr. Breu, regardless of the underlying etiology, this patient requires treatment. What does the literature suggest as the best course of action regarding crystalloid administration in patients with acute pancreatitis?

►Dr. Breu. There are 2 issues to discuss regarding IV fluids in acute pancreatitis: choice of crystalloid and rate of administration. For the choice of IV fluid, lactated Ringer solution (LR) may be preferred over normal saline (NS). There are both pathophysiologic and evidence-based rationales for this choice. As Dr. Weber alluded to, trypsinogen activation is an important step in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis and requires a low pH compartment. As most clinicians have experienced, NS may cause a metabolic acidosis; however, the use of LR may mitigate this. A 2011 randomized clinical trial showed that patients who received LR had less systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and lower C-reactive protein (CRP) levels at 24 hours compared with patients who received NS.8 While these are surrogate outcomes, they, along with the theoretical basis, suggest LR is preferred.

Regarding rate, the key is fast and early.9 In my experience, internists often underdose IV rehydration within the first 12 to 24 hours, fail to change the rate based on clinical response, and leave patients on high rates too long. In a patient like this, a rate of 350 cc/h is a reasonable place to start. But, one must reassess response (ie, ensure there is a decrease in hematocrit and/or blood urea nitrogen) every 6 hours and increase the rate as needed. After the first 24 to 48 hours have passed, the rate should be lowered.

►Dr. Ganatra. The patient received 2 mg of IV hydromorphone and a 2 L bolus of LR. This was followed by a continuous infusion of LR at 200 cc/h. Dr. Weber, apart from the standard therapies for pancreatitis, what are our treatment options in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis?

►Dr. Weber. In the acute setting, IV insulin with or without dextrose is the most extensively studied therapy. Insulin rapidly decreases triglyceride levels by activating lipoprotein lipase and inhibiting hormone- sensitive lipase. The net effect is reduction in serum triglycerides available to be hydrolyzed to free fatty acids in the pancreas.7 For severe cases (ie, where acute pancreatitis is accompanied by hypocalcemia, lactic acidosis or a markedly elevated lipase), apheresis with therapeutic plasma exchange to more rapidly reduce triglyceride concentration is the preferred therapy. The goal is to reduce triglycerides to levels

►Dr. Ganatra. Due to the possibility that the patient would require apheresis, which was not available at the VABHS West Roxbury campus, the patient was transferred to an affiliate hospital. The patient was started on 10% dextrose at 300 cc/h and an IV insulin infusion. His triglycerides fell to < 500 mg/dL over the subsequent 48 hours, and ultimately, apheresis was not required. Enteral nutrition by nasogastric (NG) tube was initiated on hospital day 6. The patient’s hospital course was notable for acute respiratory distress syndrome that required intubation for 7 days, hyperbilirubinemia (with a peak bilirubin of 10.5 mg/dL), acute kidney injury (with a peak creatinine 4.7 mg/dL), fever without an identified infectious source, alcohol withdrawal syndrome that required phenobarbital, and delirium. Nine days later, he was transferred back to the VABHS West Roxbury campus. His condition stabilized, and he was transferred to the medical floor. On hospital day 14, the patient’s mental status improved, and he began tolerating oral nutrition.

Dr. Breu, over the years, the standard of care regarding when to start enteral nutrition in pancreatitis has changed considerably. This patient received enteral nutrition via NG tube but also had periods of being NPO (nothing by mouth) for up to 6 days. What is the current best practice for timing of initiating enteral nutrition in acute pancreatitis?

►Dr. Breu. It is true that the standard of care has changed and continues to evolve. Many decades ago, patients with acute pancreatitis would routinely undergo NG tube suction to reduce delivery of gastric contents to the duodenum, thereby decreasing pancreas activation, allowing it to rest.11 The NG tube also allowed for decompression of any ileus that had formed. Beginning in the 1970s, several clinical trials were performed, showing that NG tube suction was no better than simply making the patient NPO.12,13 More recently, we have begun to move toward earlier feeding. Again, there is a pathophysiologic rationale (bowel rest is associated with intestinal atrophy, predisposing to bacterial translocation and resulting infectious complications) and increasing evidence supporting this practice.9 Even in severe pancreatitis, hunger may be used to initiate oral intake.14

►Dr. Ganatra. On hospital day 16, the patient developed sudden-onset right-sided back and flank pain, and his hemoglobin dropped to 6.1 mg/dL, which required transfusion of packed red blood cells. He remained afebrile and hemodynamically stable. Dr. Weber, what are the major complications of acute pancreatitis, and when should we suspect them? Should we be worried about complications of pancreatitis in this patient?

►Dr. Weber. Organ failure in the acute setting can occur due to activation of cytokine cascades and the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and is described by clinical and radiologic criteria called the Atlanta Classification.15 Apart from organ failure, the most serious complications of acute pancreatitis are necrosis of pancreatic tissue leading to walled-off pancreatic necrosis and the formation of peripancreatic fluid collections and pseudocysts, which occur in about 15% of patients with acute pancreatitis. These complications are serious because they can become infected, which portends a higher mortality and in some cases require surgical resection.

Other complications of acute pancreatitis include pseudoaneurysm formation, which is when a vessel bleeds into a pancreatic pseudocyst, and thromboses of the splenic, portal, or mesenteric veins. Thrombotic complications may occur in up to half of patients with pancreatic necrosis but are uncommon without some degree of necrosis.16 No necrosis was noted on this patient’s initial CT scan, so the probability of thrombosis is low. Also, as it takes several weeks for pseudocyst formation to occur, a bleeding pseudoaneurysm is unlikely at this early stage. Therefore, a complication of pancreatitis is unlikely in this patient, and evaluation for other causes of abdominal pain should be considered.

►Dr. Ganatra. A noncontrast CT of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained and revealed no evidence of complications or other acute pathology. His pain was managed conservatively, and hemoglobin remained stable. Over the next 5 days, the patient’s symptoms gradually resolved, his oral intake improved, and he was discharged home on gemfibrozil 600 mg twice daily 19 days after admission. He declined psychiatry follow-up for his PTSD, and after discharge he did not keep his scheduled gastroenterology (GI) follow-up appointment. Four months later, the patient presented again with epigastric abdominal pain similar to his initial presentation. The patient had resumed drinking, stating that “alcohol is the only thing that helps [with the PTSD].” He had not been taking the gemfibrozil. He was admitted with a recurrent episode of pancreatitis; however, his triglycerides on admission were 119 mg/dL.

Dr. Weber, this patient’s triglycerides declined rapidly over a period of just 4 months with questionable adherence to gemfibrozil. However, he was admitted again with another episode of pancreatitis, this time in the setting of alcohol use alone without markedly elevated triglycerides. What do we know about recurrence risk for pancreatitis? Are some etiologies of pancreatitis more likely to present with recurrent attacks than are others?

►Dr. Weber. The rate of recurrence following an episode of acute pancreatitis varies according to the cause, but in general, about 20% to 30% of patients will experience a recurrence, and 5% to 10% will go on to develop chronic pancreatitis.17 Alcoholic pancreatitis does carry a higher risk of recurrence than pancreatitis due to other causes; the risk is as high as 50%. Not surprisingly, recurrence of acute pancreatitis increases risk for development of chronic pancreatitis. As this patient is a smoker, it is worth noting that smoking potentiates pancreatic damage from alcohol and increases the risk for both recurrent and chronic pancreatitis.5

►Dr. Ganatra. The patient was treated with IV hydromorphone and IV LR at 350 cc/h. Oral nutrition was begun immediately. He manifested no organ dysfunction, and his symptoms improved over the course of 48 hours. He was discharged home with psychiatry and GI follow-up scheduled. Dr. Breu and Dr. Weber, how should we counsel this patient to reduce his risk of recurrent attacks of pancreatitis in the future, and what options do we have for pharmacotherapy to decrease his risk?

►Dr. Breu. I’ll let Dr. Weber comment on mitigating the risk of hypertriglyceride-induced pancreatitis and reserve my comments to pharmacotherapy in alcohol use disorder. This patient may be a candidate for naltrexone therapy, either in oral or intramuscular formulations. Both have been showed to reduce the risk of returning to heavy drinking and may be particularly beneficial in those with a family history.18,19 Acamprosate is also an option.

►Dr. Weber. Data on recurrence risk in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis are limited, but there are case reports suggesting that a fatty diet and alcohol use are implicated in recurrence.20 I would counsel the patient on lifestyle modifications that are known to reduce this risk. I agree with Dr. Breu that devoting our efforts to helping him reduce or eliminate his alcohol consumption is the single most important thing we can do to reduce his risk for recurrent attacks. Since the patient reports that he drinks alcohol in order to cope with his PTSD, establishing care with a mental health provider to address this is of the utmost importance. In addition, smoking cessation and promoting medication adherence with gemfibrozil will also reduce risk for future episodes, but continued alcohol use is his strongest risk factor.

►Dr. Ganatra. After discharge, the patient engaged with outpatient psychiatry and GI. He still reports feeling that alcohol is the only thing that alleviates his PTSD and anxiety symptoms. He is not currently interested in pharmacotherapy for cessation of alcohol use.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ivana Jankovic, MD, Matthew Lewis Chase, MD

1. Dufour MC, Adamson MD. The epidemiology of alcohol-induced pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2003;27(4):286-290.

2. Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(5):1179-1187.e1-e3.

3. Cavallini G, Frulloni L, Bassi C, et al; ProInf-AISP Study Group. Prospective multicentre survey on acute pancreatitis in Italy (ProInf-AISP): results on 1005 patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36(3):205-211.

4. Banks PA, Freeman ML; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(10):2379-2400.

5. Hartwig W, Werner J, Ryschich E, et al. Cigarette smoke enhances ethanol-induced pancreatic injury. Pancreas. 2000;21(3):272-278.

6. Chowdhury P, Gupta P. Pathophysiology of alcoholic pancreatitis: an overview. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(46):7421-7427.

7. Scherer J, Singh VP, Pitchumoni CS, Yadav D. Issues in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis: an update. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(3):195-203.

8. Wu BU, Hwang JQ, Gardner TH, et al. Lactated Ringer’s solution reduces systemic inflammation compared with saline in patients with acute pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(8):710-717.e1.

9. Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J, Vege SS; American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(9):1400-1415; 1416.

10. Preiss D, Tikkanen MJ, Welsh P, et al. Lipid-modifying therapies and risk of pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012;308(8):804-811.

11. Nardi GL. Pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1963;268(19):1065-1067.

12. Naeije R, Salingret E, Clumeck N, De Troyer A, Devis G. Is nasogastric suction necessary in acute pancreatitis? Br Med J. 1978;2(6138):659-660.

13. Levant JA, Secrist DM, Resin H, Sturdevant RA, Guth PH. Nasogastric suction in the treatment of alcoholic pancreatitis: a controlled study. JAMA. 1974;229(1):51-52.

14. Zhao XL, Zhu SF, Xue GJ, et al. Early oral refeeding based on hunger in moderate and severe acute pancreatitis: a prospective controlled, randomized clinical trial. Nutrition. 2015;31(1):171-175.

15. Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62(1):102-111.

16. Easler J, Muddana V, Furlan A, et al. Portosplenomesenteric venous thrombosis in patients with acute pancreatitis is associated with pancreatic necrosis and usually has a benign course. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(5):854-862.

17. Yadav D, O’Connell M, Papachristou GI. Natural history following the first attack of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(7):1096-1103.

18. Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1889-1900.

19. Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O’Malley SS, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(13):1617-1625.

20. Piolot A, Nadler F, Cavallero E, Coquard JL, Jacotot B. Prevention of recurrent acute pancreatitis in patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia: value of regular plasmapheresis. Pancreas. 1996;13(1):96-99.

Case Presentation. A 23-year-old male U.S. Army veteran with a history of alcohol use disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) presented to the VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) West Roxbury campus emergency department (ED) with epigastric abdominal pain in the setting of consuming alcohol. The patient had served in the infantry in Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom. He consumed up to 12 alcoholic drinks per day (both beer and hard liquor) for the past 3 years and had been hospitalized 3 times previously; twice for alcohol detoxification and once for PTSD. He is a former tobacco smoker with fewer than 5 pack-years, he uses marijuana often and does not use IV drugs. In the ED, his physical examination was notable for a heart rate of 130 beats per minute and blood pressure of 161/111 mm Hg. He was alert and oriented and had a mild tremor. The patient was diaphoretic with dry mucous membranes, tenderness to palpation in the epigastrium, and abdominal guarding. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen revealed acute pancreatitis without necrosis. The patient received 1 L of normal saline and was admitted to the medical ward for presumed alcoholic pancreatitis.

► Rahul Ganatra, MD, MPH, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Dr. Weber, we care for many young people who drink more than they should and almost none of them end up with alcoholic pancreatitis. What are the relevant risk factors that make individuals like this patient more susceptible to alcoholic pancreatitis?

►Horst Christian Weber, MD, Gastroenterology Service, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. While we don’t have a good understanding of the precise mechanism of alcoholic pancreatitis, we do know that in the U.S., alcohol consumption is responsible for about one-third of all cases.1 Acute pancreatitis in general may present with a wide range of disease severity. It is the most common cause of gastrointestinal-related hospitalization,2 and the mortality of hospital inpatients with pancreatitis is about 5%.3,4 Therefore, acute pancreatitis represents a prevalent condition with a critical impact on morbidity and mortality. Alcoholic pancreatitis typically occurs after many years of heavy alcohol use, not after a single drinking

► Dr. Ganatra. At this point, the chemistry laboratory paged the admitting resident with the notification that the patient’s blood was grossly lipemic. Ultracentrifugation was performed to separate the lipid layer and his laboratory values result (Table). Notable abnormalities included polycythemia with a hemoglobin of 17.4 g/dL, hyponatremia with a sodium of 129 mmol/L, normal renal function, elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (AST 258 IU/L and ALT 153 IU/L, respectively), hyperbilirubinemia with a total bilirubin of 2.7 mg/dL, and a serum alcohol level of 147 mg/dL. Due to anticipated requirement for a higher level of care, the patient was transferred to the Medical Intensive Care Unit (MICU).

Dr. Breu, can you help us interpret this patient’s numerous laboratory abnormalities? Without yet having the triglyceride level available, how does the fact that the patient’s blood was lipemic affect our interpretation of his labs? What further workup is warranted?

► Anthony Breu, MD, Medical Service, VABHS, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School. First, the positive alcohol level confirms a recent ingestion. Second, he has elevated transaminases with the AST greater than the ALT, which is consistent with alcoholic liver disease. While the initial assumption is that this patient has alcohol-induced pancreatitis, the elevations in bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase may suggest gallstone pancreatitis, and the lipemic appearing serum could suggest triglyceride-mediated pancreatitis. If the patient does have elevated triglyceride levels, the sodium level may indicate pseudohyponatremia, a laboratory artifact seen if a dilution step is used. To further evaluate the patient, I would obtain a triglyceride level and a right upper quadrant ultrasound. Direct ion-selective electrode analysis of the sodium level can be done with a device used to measure blood gases to exclude pseudohyponatremia.

► Dr. Ganatra. A right upper quadrant ultrasound was obtained in the MICU, which showed hepatic steatosis and hepatomegaly to 19 cm, but no evidence of biliary obstruction by stones or sludge. The common bile duct measured 3.2 mm in diameter. A triglyceride level returned above assay at > 3,392 mg/dL. A review of the medical record revealed a triglyceride level of 105 mg/dL 16 months prior. The Gastroenterology Department was consulted.

Dr. Weber, we now have 2 etiologies for pancreatitis in this patient: alcohol and hypertriglyceridemia. How do each cause pancreatitis? Is it possible to determine in this case which one is the more likely driver?

► Dr. Weber. The mechanism for alcohol-induced pancreatitis is not fully known, but there are several hypotheses. One is that alcohol may increase the synthesis or activation of pancreatic digestive enzymes.6 Another is that metabolites of alcohol are directly toxic to the pancreas.6 Based on the epidemiologic observation that alcoholic pancreatitis usually happens in long-standing users, all we can say is that it is not very likely to be the effect of an acute insult. For hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis, we believe the injury is due to the toxic effect of free fatty acids in the pancreas liberated by lipolysis of triglycerides by pancreatic lipases. Higher triglycerides are associated with higher risk, suggesting a dose-response relationship: This risk is not greatly increased until triglycerides exceed 500 mg/dL; above 1,000 mg/dL, the risk is about 5%, and above 2,000 mg/dL, the risk is between 10% and 20%.7 In summary, we cannot really determine whether the alcohol or the triglycerides are the main cause of his pancreatitis, but given his markedly elevated triglycerides, he should be treated for hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis.

►Dr. Ganatra. Dr. Breu, regardless of the underlying etiology, this patient requires treatment. What does the literature suggest as the best course of action regarding crystalloid administration in patients with acute pancreatitis?

►Dr. Breu. There are 2 issues to discuss regarding IV fluids in acute pancreatitis: choice of crystalloid and rate of administration. For the choice of IV fluid, lactated Ringer solution (LR) may be preferred over normal saline (NS). There are both pathophysiologic and evidence-based rationales for this choice. As Dr. Weber alluded to, trypsinogen activation is an important step in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis and requires a low pH compartment. As most clinicians have experienced, NS may cause a metabolic acidosis; however, the use of LR may mitigate this. A 2011 randomized clinical trial showed that patients who received LR had less systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and lower C-reactive protein (CRP) levels at 24 hours compared with patients who received NS.8 While these are surrogate outcomes, they, along with the theoretical basis, suggest LR is preferred.

Regarding rate, the key is fast and early.9 In my experience, internists often underdose IV rehydration within the first 12 to 24 hours, fail to change the rate based on clinical response, and leave patients on high rates too long. In a patient like this, a rate of 350 cc/h is a reasonable place to start. But, one must reassess response (ie, ensure there is a decrease in hematocrit and/or blood urea nitrogen) every 6 hours and increase the rate as needed. After the first 24 to 48 hours have passed, the rate should be lowered.

►Dr. Ganatra. The patient received 2 mg of IV hydromorphone and a 2 L bolus of LR. This was followed by a continuous infusion of LR at 200 cc/h. Dr. Weber, apart from the standard therapies for pancreatitis, what are our treatment options in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis?

►Dr. Weber. In the acute setting, IV insulin with or without dextrose is the most extensively studied therapy. Insulin rapidly decreases triglyceride levels by activating lipoprotein lipase and inhibiting hormone- sensitive lipase. The net effect is reduction in serum triglycerides available to be hydrolyzed to free fatty acids in the pancreas.7 For severe cases (ie, where acute pancreatitis is accompanied by hypocalcemia, lactic acidosis or a markedly elevated lipase), apheresis with therapeutic plasma exchange to more rapidly reduce triglyceride concentration is the preferred therapy. The goal is to reduce triglycerides to levels

►Dr. Ganatra. Due to the possibility that the patient would require apheresis, which was not available at the VABHS West Roxbury campus, the patient was transferred to an affiliate hospital. The patient was started on 10% dextrose at 300 cc/h and an IV insulin infusion. His triglycerides fell to < 500 mg/dL over the subsequent 48 hours, and ultimately, apheresis was not required. Enteral nutrition by nasogastric (NG) tube was initiated on hospital day 6. The patient’s hospital course was notable for acute respiratory distress syndrome that required intubation for 7 days, hyperbilirubinemia (with a peak bilirubin of 10.5 mg/dL), acute kidney injury (with a peak creatinine 4.7 mg/dL), fever without an identified infectious source, alcohol withdrawal syndrome that required phenobarbital, and delirium. Nine days later, he was transferred back to the VABHS West Roxbury campus. His condition stabilized, and he was transferred to the medical floor. On hospital day 14, the patient’s mental status improved, and he began tolerating oral nutrition.

Dr. Breu, over the years, the standard of care regarding when to start enteral nutrition in pancreatitis has changed considerably. This patient received enteral nutrition via NG tube but also had periods of being NPO (nothing by mouth) for up to 6 days. What is the current best practice for timing of initiating enteral nutrition in acute pancreatitis?

►Dr. Breu. It is true that the standard of care has changed and continues to evolve. Many decades ago, patients with acute pancreatitis would routinely undergo NG tube suction to reduce delivery of gastric contents to the duodenum, thereby decreasing pancreas activation, allowing it to rest.11 The NG tube also allowed for decompression of any ileus that had formed. Beginning in the 1970s, several clinical trials were performed, showing that NG tube suction was no better than simply making the patient NPO.12,13 More recently, we have begun to move toward earlier feeding. Again, there is a pathophysiologic rationale (bowel rest is associated with intestinal atrophy, predisposing to bacterial translocation and resulting infectious complications) and increasing evidence supporting this practice.9 Even in severe pancreatitis, hunger may be used to initiate oral intake.14

►Dr. Ganatra. On hospital day 16, the patient developed sudden-onset right-sided back and flank pain, and his hemoglobin dropped to 6.1 mg/dL, which required transfusion of packed red blood cells. He remained afebrile and hemodynamically stable. Dr. Weber, what are the major complications of acute pancreatitis, and when should we suspect them? Should we be worried about complications of pancreatitis in this patient?

►Dr. Weber. Organ failure in the acute setting can occur due to activation of cytokine cascades and the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and is described by clinical and radiologic criteria called the Atlanta Classification.15 Apart from organ failure, the most serious complications of acute pancreatitis are necrosis of pancreatic tissue leading to walled-off pancreatic necrosis and the formation of peripancreatic fluid collections and pseudocysts, which occur in about 15% of patients with acute pancreatitis. These complications are serious because they can become infected, which portends a higher mortality and in some cases require surgical resection.

Other complications of acute pancreatitis include pseudoaneurysm formation, which is when a vessel bleeds into a pancreatic pseudocyst, and thromboses of the splenic, portal, or mesenteric veins. Thrombotic complications may occur in up to half of patients with pancreatic necrosis but are uncommon without some degree of necrosis.16 No necrosis was noted on this patient’s initial CT scan, so the probability of thrombosis is low. Also, as it takes several weeks for pseudocyst formation to occur, a bleeding pseudoaneurysm is unlikely at this early stage. Therefore, a complication of pancreatitis is unlikely in this patient, and evaluation for other causes of abdominal pain should be considered.

►Dr. Ganatra. A noncontrast CT of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained and revealed no evidence of complications or other acute pathology. His pain was managed conservatively, and hemoglobin remained stable. Over the next 5 days, the patient’s symptoms gradually resolved, his oral intake improved, and he was discharged home on gemfibrozil 600 mg twice daily 19 days after admission. He declined psychiatry follow-up for his PTSD, and after discharge he did not keep his scheduled gastroenterology (GI) follow-up appointment. Four months later, the patient presented again with epigastric abdominal pain similar to his initial presentation. The patient had resumed drinking, stating that “alcohol is the only thing that helps [with the PTSD].” He had not been taking the gemfibrozil. He was admitted with a recurrent episode of pancreatitis; however, his triglycerides on admission were 119 mg/dL.

Dr. Weber, this patient’s triglycerides declined rapidly over a period of just 4 months with questionable adherence to gemfibrozil. However, he was admitted again with another episode of pancreatitis, this time in the setting of alcohol use alone without markedly elevated triglycerides. What do we know about recurrence risk for pancreatitis? Are some etiologies of pancreatitis more likely to present with recurrent attacks than are others?

►Dr. Weber. The rate of recurrence following an episode of acute pancreatitis varies according to the cause, but in general, about 20% to 30% of patients will experience a recurrence, and 5% to 10% will go on to develop chronic pancreatitis.17 Alcoholic pancreatitis does carry a higher risk of recurrence than pancreatitis due to other causes; the risk is as high as 50%. Not surprisingly, recurrence of acute pancreatitis increases risk for development of chronic pancreatitis. As this patient is a smoker, it is worth noting that smoking potentiates pancreatic damage from alcohol and increases the risk for both recurrent and chronic pancreatitis.5

►Dr. Ganatra. The patient was treated with IV hydromorphone and IV LR at 350 cc/h. Oral nutrition was begun immediately. He manifested no organ dysfunction, and his symptoms improved over the course of 48 hours. He was discharged home with psychiatry and GI follow-up scheduled. Dr. Breu and Dr. Weber, how should we counsel this patient to reduce his risk of recurrent attacks of pancreatitis in the future, and what options do we have for pharmacotherapy to decrease his risk?

►Dr. Breu. I’ll let Dr. Weber comment on mitigating the risk of hypertriglyceride-induced pancreatitis and reserve my comments to pharmacotherapy in alcohol use disorder. This patient may be a candidate for naltrexone therapy, either in oral or intramuscular formulations. Both have been showed to reduce the risk of returning to heavy drinking and may be particularly beneficial in those with a family history.18,19 Acamprosate is also an option.

►Dr. Weber. Data on recurrence risk in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis are limited, but there are case reports suggesting that a fatty diet and alcohol use are implicated in recurrence.20 I would counsel the patient on lifestyle modifications that are known to reduce this risk. I agree with Dr. Breu that devoting our efforts to helping him reduce or eliminate his alcohol consumption is the single most important thing we can do to reduce his risk for recurrent attacks. Since the patient reports that he drinks alcohol in order to cope with his PTSD, establishing care with a mental health provider to address this is of the utmost importance. In addition, smoking cessation and promoting medication adherence with gemfibrozil will also reduce risk for future episodes, but continued alcohol use is his strongest risk factor.

►Dr. Ganatra. After discharge, the patient engaged with outpatient psychiatry and GI. He still reports feeling that alcohol is the only thing that alleviates his PTSD and anxiety symptoms. He is not currently interested in pharmacotherapy for cessation of alcohol use.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ivana Jankovic, MD, Matthew Lewis Chase, MD

Case Presentation. A 23-year-old male U.S. Army veteran with a history of alcohol use disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) presented to the VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) West Roxbury campus emergency department (ED) with epigastric abdominal pain in the setting of consuming alcohol. The patient had served in the infantry in Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom. He consumed up to 12 alcoholic drinks per day (both beer and hard liquor) for the past 3 years and had been hospitalized 3 times previously; twice for alcohol detoxification and once for PTSD. He is a former tobacco smoker with fewer than 5 pack-years, he uses marijuana often and does not use IV drugs. In the ED, his physical examination was notable for a heart rate of 130 beats per minute and blood pressure of 161/111 mm Hg. He was alert and oriented and had a mild tremor. The patient was diaphoretic with dry mucous membranes, tenderness to palpation in the epigastrium, and abdominal guarding. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen revealed acute pancreatitis without necrosis. The patient received 1 L of normal saline and was admitted to the medical ward for presumed alcoholic pancreatitis.

► Rahul Ganatra, MD, MPH, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Dr. Weber, we care for many young people who drink more than they should and almost none of them end up with alcoholic pancreatitis. What are the relevant risk factors that make individuals like this patient more susceptible to alcoholic pancreatitis?

►Horst Christian Weber, MD, Gastroenterology Service, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. While we don’t have a good understanding of the precise mechanism of alcoholic pancreatitis, we do know that in the U.S., alcohol consumption is responsible for about one-third of all cases.1 Acute pancreatitis in general may present with a wide range of disease severity. It is the most common cause of gastrointestinal-related hospitalization,2 and the mortality of hospital inpatients with pancreatitis is about 5%.3,4 Therefore, acute pancreatitis represents a prevalent condition with a critical impact on morbidity and mortality. Alcoholic pancreatitis typically occurs after many years of heavy alcohol use, not after a single drinking

► Dr. Ganatra. At this point, the chemistry laboratory paged the admitting resident with the notification that the patient’s blood was grossly lipemic. Ultracentrifugation was performed to separate the lipid layer and his laboratory values result (Table). Notable abnormalities included polycythemia with a hemoglobin of 17.4 g/dL, hyponatremia with a sodium of 129 mmol/L, normal renal function, elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (AST 258 IU/L and ALT 153 IU/L, respectively), hyperbilirubinemia with a total bilirubin of 2.7 mg/dL, and a serum alcohol level of 147 mg/dL. Due to anticipated requirement for a higher level of care, the patient was transferred to the Medical Intensive Care Unit (MICU).

Dr. Breu, can you help us interpret this patient’s numerous laboratory abnormalities? Without yet having the triglyceride level available, how does the fact that the patient’s blood was lipemic affect our interpretation of his labs? What further workup is warranted?

► Anthony Breu, MD, Medical Service, VABHS, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School. First, the positive alcohol level confirms a recent ingestion. Second, he has elevated transaminases with the AST greater than the ALT, which is consistent with alcoholic liver disease. While the initial assumption is that this patient has alcohol-induced pancreatitis, the elevations in bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase may suggest gallstone pancreatitis, and the lipemic appearing serum could suggest triglyceride-mediated pancreatitis. If the patient does have elevated triglyceride levels, the sodium level may indicate pseudohyponatremia, a laboratory artifact seen if a dilution step is used. To further evaluate the patient, I would obtain a triglyceride level and a right upper quadrant ultrasound. Direct ion-selective electrode analysis of the sodium level can be done with a device used to measure blood gases to exclude pseudohyponatremia.

► Dr. Ganatra. A right upper quadrant ultrasound was obtained in the MICU, which showed hepatic steatosis and hepatomegaly to 19 cm, but no evidence of biliary obstruction by stones or sludge. The common bile duct measured 3.2 mm in diameter. A triglyceride level returned above assay at > 3,392 mg/dL. A review of the medical record revealed a triglyceride level of 105 mg/dL 16 months prior. The Gastroenterology Department was consulted.

Dr. Weber, we now have 2 etiologies for pancreatitis in this patient: alcohol and hypertriglyceridemia. How do each cause pancreatitis? Is it possible to determine in this case which one is the more likely driver?

► Dr. Weber. The mechanism for alcohol-induced pancreatitis is not fully known, but there are several hypotheses. One is that alcohol may increase the synthesis or activation of pancreatic digestive enzymes.6 Another is that metabolites of alcohol are directly toxic to the pancreas.6 Based on the epidemiologic observation that alcoholic pancreatitis usually happens in long-standing users, all we can say is that it is not very likely to be the effect of an acute insult. For hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis, we believe the injury is due to the toxic effect of free fatty acids in the pancreas liberated by lipolysis of triglycerides by pancreatic lipases. Higher triglycerides are associated with higher risk, suggesting a dose-response relationship: This risk is not greatly increased until triglycerides exceed 500 mg/dL; above 1,000 mg/dL, the risk is about 5%, and above 2,000 mg/dL, the risk is between 10% and 20%.7 In summary, we cannot really determine whether the alcohol or the triglycerides are the main cause of his pancreatitis, but given his markedly elevated triglycerides, he should be treated for hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis.

►Dr. Ganatra. Dr. Breu, regardless of the underlying etiology, this patient requires treatment. What does the literature suggest as the best course of action regarding crystalloid administration in patients with acute pancreatitis?

►Dr. Breu. There are 2 issues to discuss regarding IV fluids in acute pancreatitis: choice of crystalloid and rate of administration. For the choice of IV fluid, lactated Ringer solution (LR) may be preferred over normal saline (NS). There are both pathophysiologic and evidence-based rationales for this choice. As Dr. Weber alluded to, trypsinogen activation is an important step in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis and requires a low pH compartment. As most clinicians have experienced, NS may cause a metabolic acidosis; however, the use of LR may mitigate this. A 2011 randomized clinical trial showed that patients who received LR had less systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and lower C-reactive protein (CRP) levels at 24 hours compared with patients who received NS.8 While these are surrogate outcomes, they, along with the theoretical basis, suggest LR is preferred.

Regarding rate, the key is fast and early.9 In my experience, internists often underdose IV rehydration within the first 12 to 24 hours, fail to change the rate based on clinical response, and leave patients on high rates too long. In a patient like this, a rate of 350 cc/h is a reasonable place to start. But, one must reassess response (ie, ensure there is a decrease in hematocrit and/or blood urea nitrogen) every 6 hours and increase the rate as needed. After the first 24 to 48 hours have passed, the rate should be lowered.

►Dr. Ganatra. The patient received 2 mg of IV hydromorphone and a 2 L bolus of LR. This was followed by a continuous infusion of LR at 200 cc/h. Dr. Weber, apart from the standard therapies for pancreatitis, what are our treatment options in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis?

►Dr. Weber. In the acute setting, IV insulin with or without dextrose is the most extensively studied therapy. Insulin rapidly decreases triglyceride levels by activating lipoprotein lipase and inhibiting hormone- sensitive lipase. The net effect is reduction in serum triglycerides available to be hydrolyzed to free fatty acids in the pancreas.7 For severe cases (ie, where acute pancreatitis is accompanied by hypocalcemia, lactic acidosis or a markedly elevated lipase), apheresis with therapeutic plasma exchange to more rapidly reduce triglyceride concentration is the preferred therapy. The goal is to reduce triglycerides to levels

►Dr. Ganatra. Due to the possibility that the patient would require apheresis, which was not available at the VABHS West Roxbury campus, the patient was transferred to an affiliate hospital. The patient was started on 10% dextrose at 300 cc/h and an IV insulin infusion. His triglycerides fell to < 500 mg/dL over the subsequent 48 hours, and ultimately, apheresis was not required. Enteral nutrition by nasogastric (NG) tube was initiated on hospital day 6. The patient’s hospital course was notable for acute respiratory distress syndrome that required intubation for 7 days, hyperbilirubinemia (with a peak bilirubin of 10.5 mg/dL), acute kidney injury (with a peak creatinine 4.7 mg/dL), fever without an identified infectious source, alcohol withdrawal syndrome that required phenobarbital, and delirium. Nine days later, he was transferred back to the VABHS West Roxbury campus. His condition stabilized, and he was transferred to the medical floor. On hospital day 14, the patient’s mental status improved, and he began tolerating oral nutrition.

Dr. Breu, over the years, the standard of care regarding when to start enteral nutrition in pancreatitis has changed considerably. This patient received enteral nutrition via NG tube but also had periods of being NPO (nothing by mouth) for up to 6 days. What is the current best practice for timing of initiating enteral nutrition in acute pancreatitis?

►Dr. Breu. It is true that the standard of care has changed and continues to evolve. Many decades ago, patients with acute pancreatitis would routinely undergo NG tube suction to reduce delivery of gastric contents to the duodenum, thereby decreasing pancreas activation, allowing it to rest.11 The NG tube also allowed for decompression of any ileus that had formed. Beginning in the 1970s, several clinical trials were performed, showing that NG tube suction was no better than simply making the patient NPO.12,13 More recently, we have begun to move toward earlier feeding. Again, there is a pathophysiologic rationale (bowel rest is associated with intestinal atrophy, predisposing to bacterial translocation and resulting infectious complications) and increasing evidence supporting this practice.9 Even in severe pancreatitis, hunger may be used to initiate oral intake.14

►Dr. Ganatra. On hospital day 16, the patient developed sudden-onset right-sided back and flank pain, and his hemoglobin dropped to 6.1 mg/dL, which required transfusion of packed red blood cells. He remained afebrile and hemodynamically stable. Dr. Weber, what are the major complications of acute pancreatitis, and when should we suspect them? Should we be worried about complications of pancreatitis in this patient?

►Dr. Weber. Organ failure in the acute setting can occur due to activation of cytokine cascades and the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and is described by clinical and radiologic criteria called the Atlanta Classification.15 Apart from organ failure, the most serious complications of acute pancreatitis are necrosis of pancreatic tissue leading to walled-off pancreatic necrosis and the formation of peripancreatic fluid collections and pseudocysts, which occur in about 15% of patients with acute pancreatitis. These complications are serious because they can become infected, which portends a higher mortality and in some cases require surgical resection.

Other complications of acute pancreatitis include pseudoaneurysm formation, which is when a vessel bleeds into a pancreatic pseudocyst, and thromboses of the splenic, portal, or mesenteric veins. Thrombotic complications may occur in up to half of patients with pancreatic necrosis but are uncommon without some degree of necrosis.16 No necrosis was noted on this patient’s initial CT scan, so the probability of thrombosis is low. Also, as it takes several weeks for pseudocyst formation to occur, a bleeding pseudoaneurysm is unlikely at this early stage. Therefore, a complication of pancreatitis is unlikely in this patient, and evaluation for other causes of abdominal pain should be considered.

►Dr. Ganatra. A noncontrast CT of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained and revealed no evidence of complications or other acute pathology. His pain was managed conservatively, and hemoglobin remained stable. Over the next 5 days, the patient’s symptoms gradually resolved, his oral intake improved, and he was discharged home on gemfibrozil 600 mg twice daily 19 days after admission. He declined psychiatry follow-up for his PTSD, and after discharge he did not keep his scheduled gastroenterology (GI) follow-up appointment. Four months later, the patient presented again with epigastric abdominal pain similar to his initial presentation. The patient had resumed drinking, stating that “alcohol is the only thing that helps [with the PTSD].” He had not been taking the gemfibrozil. He was admitted with a recurrent episode of pancreatitis; however, his triglycerides on admission were 119 mg/dL.

Dr. Weber, this patient’s triglycerides declined rapidly over a period of just 4 months with questionable adherence to gemfibrozil. However, he was admitted again with another episode of pancreatitis, this time in the setting of alcohol use alone without markedly elevated triglycerides. What do we know about recurrence risk for pancreatitis? Are some etiologies of pancreatitis more likely to present with recurrent attacks than are others?

►Dr. Weber. The rate of recurrence following an episode of acute pancreatitis varies according to the cause, but in general, about 20% to 30% of patients will experience a recurrence, and 5% to 10% will go on to develop chronic pancreatitis.17 Alcoholic pancreatitis does carry a higher risk of recurrence than pancreatitis due to other causes; the risk is as high as 50%. Not surprisingly, recurrence of acute pancreatitis increases risk for development of chronic pancreatitis. As this patient is a smoker, it is worth noting that smoking potentiates pancreatic damage from alcohol and increases the risk for both recurrent and chronic pancreatitis.5

►Dr. Ganatra. The patient was treated with IV hydromorphone and IV LR at 350 cc/h. Oral nutrition was begun immediately. He manifested no organ dysfunction, and his symptoms improved over the course of 48 hours. He was discharged home with psychiatry and GI follow-up scheduled. Dr. Breu and Dr. Weber, how should we counsel this patient to reduce his risk of recurrent attacks of pancreatitis in the future, and what options do we have for pharmacotherapy to decrease his risk?

►Dr. Breu. I’ll let Dr. Weber comment on mitigating the risk of hypertriglyceride-induced pancreatitis and reserve my comments to pharmacotherapy in alcohol use disorder. This patient may be a candidate for naltrexone therapy, either in oral or intramuscular formulations. Both have been showed to reduce the risk of returning to heavy drinking and may be particularly beneficial in those with a family history.18,19 Acamprosate is also an option.

►Dr. Weber. Data on recurrence risk in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis are limited, but there are case reports suggesting that a fatty diet and alcohol use are implicated in recurrence.20 I would counsel the patient on lifestyle modifications that are known to reduce this risk. I agree with Dr. Breu that devoting our efforts to helping him reduce or eliminate his alcohol consumption is the single most important thing we can do to reduce his risk for recurrent attacks. Since the patient reports that he drinks alcohol in order to cope with his PTSD, establishing care with a mental health provider to address this is of the utmost importance. In addition, smoking cessation and promoting medication adherence with gemfibrozil will also reduce risk for future episodes, but continued alcohol use is his strongest risk factor.

►Dr. Ganatra. After discharge, the patient engaged with outpatient psychiatry and GI. He still reports feeling that alcohol is the only thing that alleviates his PTSD and anxiety symptoms. He is not currently interested in pharmacotherapy for cessation of alcohol use.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ivana Jankovic, MD, Matthew Lewis Chase, MD

1. Dufour MC, Adamson MD. The epidemiology of alcohol-induced pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2003;27(4):286-290.

2. Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(5):1179-1187.e1-e3.

3. Cavallini G, Frulloni L, Bassi C, et al; ProInf-AISP Study Group. Prospective multicentre survey on acute pancreatitis in Italy (ProInf-AISP): results on 1005 patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36(3):205-211.

4. Banks PA, Freeman ML; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(10):2379-2400.

5. Hartwig W, Werner J, Ryschich E, et al. Cigarette smoke enhances ethanol-induced pancreatic injury. Pancreas. 2000;21(3):272-278.

6. Chowdhury P, Gupta P. Pathophysiology of alcoholic pancreatitis: an overview. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(46):7421-7427.

7. Scherer J, Singh VP, Pitchumoni CS, Yadav D. Issues in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis: an update. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(3):195-203.

8. Wu BU, Hwang JQ, Gardner TH, et al. Lactated Ringer’s solution reduces systemic inflammation compared with saline in patients with acute pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(8):710-717.e1.

9. Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J, Vege SS; American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(9):1400-1415; 1416.

10. Preiss D, Tikkanen MJ, Welsh P, et al. Lipid-modifying therapies and risk of pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012;308(8):804-811.

11. Nardi GL. Pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1963;268(19):1065-1067.

12. Naeije R, Salingret E, Clumeck N, De Troyer A, Devis G. Is nasogastric suction necessary in acute pancreatitis? Br Med J. 1978;2(6138):659-660.

13. Levant JA, Secrist DM, Resin H, Sturdevant RA, Guth PH. Nasogastric suction in the treatment of alcoholic pancreatitis: a controlled study. JAMA. 1974;229(1):51-52.

14. Zhao XL, Zhu SF, Xue GJ, et al. Early oral refeeding based on hunger in moderate and severe acute pancreatitis: a prospective controlled, randomized clinical trial. Nutrition. 2015;31(1):171-175.

15. Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62(1):102-111.

16. Easler J, Muddana V, Furlan A, et al. Portosplenomesenteric venous thrombosis in patients with acute pancreatitis is associated with pancreatic necrosis and usually has a benign course. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(5):854-862.

17. Yadav D, O’Connell M, Papachristou GI. Natural history following the first attack of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(7):1096-1103.

18. Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1889-1900.

19. Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O’Malley SS, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(13):1617-1625.

20. Piolot A, Nadler F, Cavallero E, Coquard JL, Jacotot B. Prevention of recurrent acute pancreatitis in patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia: value of regular plasmapheresis. Pancreas. 1996;13(1):96-99.

1. Dufour MC, Adamson MD. The epidemiology of alcohol-induced pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2003;27(4):286-290.

2. Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(5):1179-1187.e1-e3.

3. Cavallini G, Frulloni L, Bassi C, et al; ProInf-AISP Study Group. Prospective multicentre survey on acute pancreatitis in Italy (ProInf-AISP): results on 1005 patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36(3):205-211.

4. Banks PA, Freeman ML; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(10):2379-2400.

5. Hartwig W, Werner J, Ryschich E, et al. Cigarette smoke enhances ethanol-induced pancreatic injury. Pancreas. 2000;21(3):272-278.

6. Chowdhury P, Gupta P. Pathophysiology of alcoholic pancreatitis: an overview. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(46):7421-7427.

7. Scherer J, Singh VP, Pitchumoni CS, Yadav D. Issues in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis: an update. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(3):195-203.

8. Wu BU, Hwang JQ, Gardner TH, et al. Lactated Ringer’s solution reduces systemic inflammation compared with saline in patients with acute pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(8):710-717.e1.

9. Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J, Vege SS; American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(9):1400-1415; 1416.

10. Preiss D, Tikkanen MJ, Welsh P, et al. Lipid-modifying therapies and risk of pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012;308(8):804-811.

11. Nardi GL. Pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1963;268(19):1065-1067.

12. Naeije R, Salingret E, Clumeck N, De Troyer A, Devis G. Is nasogastric suction necessary in acute pancreatitis? Br Med J. 1978;2(6138):659-660.

13. Levant JA, Secrist DM, Resin H, Sturdevant RA, Guth PH. Nasogastric suction in the treatment of alcoholic pancreatitis: a controlled study. JAMA. 1974;229(1):51-52.

14. Zhao XL, Zhu SF, Xue GJ, et al. Early oral refeeding based on hunger in moderate and severe acute pancreatitis: a prospective controlled, randomized clinical trial. Nutrition. 2015;31(1):171-175.

15. Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62(1):102-111.

16. Easler J, Muddana V, Furlan A, et al. Portosplenomesenteric venous thrombosis in patients with acute pancreatitis is associated with pancreatic necrosis and usually has a benign course. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(5):854-862.

17. Yadav D, O’Connell M, Papachristou GI. Natural history following the first attack of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(7):1096-1103.

18. Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1889-1900.

19. Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O’Malley SS, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(13):1617-1625.

20. Piolot A, Nadler F, Cavallero E, Coquard JL, Jacotot B. Prevention of recurrent acute pancreatitis in patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia: value of regular plasmapheresis. Pancreas. 1996;13(1):96-99.

Boston VA Medical Forum: HIV-Positive Veteran With Progressive Visual Changes

►Lakshmana Swamy, MD, chief medical resident, VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) and Boston Medical Center. Dr. Serrao, when you hear about vision changes in a patient with HIV, what differential diagnosis is generated? What epidemiologic or historical factors can help distinguish these entities?

►Richard Serrao, MD, Infectious Disease Service, VABHS and assistant professor of medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. The differential diagnoses for vision changes in a patient with HIV is based on the overall immunosuppression of the patient: the lower the patient’s CD4 count, the higher the number of etiologies.1 The portions of the visual pathway as well as the pattern of vision loss are useful in narrowing the differential. For example, monocular visual disturbances with dermatomal vesicles within the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve strongly implicates varicella zoster retinitis or keratitis; abducens nerve palsy could suggest granulomatous basilar meningitis from cryptococcosis. Likewise, ongoing fevers in an advanced AIDS patient with concomitant colitis, hepatitis, and pneumonitis is strongly suspicious for cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis with wide dissemination.

Geographic epidemiologic factors can suggest pathogens more prevalent to certain regions of the world, such as histoplasma chorioretinitis in a resident of the central and eastern U.S. or tuberculosis in a returning traveler. Likewise, a cat owner or one who consumes steak tartare increases the likelihood for toxoplasma retinochoroiditis, or syphilis in men who have sex with men (MSM) in the U.S. given that the majority of new cases occur in this patient population. Other clues one should consider include the presence of splinter hemorrhages in the extremities in an intravenous drug user, raising the possibility of embolic endophthalmitis from bacterial or fungal endocarditis. A variety of other diagnoses can certainly occur as a result of drug treatment (uveitis from rifampin, for example), immune reconstitution from HAART, infections with other HIV-associated pathogens, such as Pneumocystis jiroveci, and many non-HIV-related ocular diseases.

►Dr. Swamy. Dr. Butler, what concerns do you have when you hear about an HIV-infected patient with vision loss from the ophthalmology perspective?

►Nicholas Butler, MD, Ophthalmology Service, Uveitis and Ocular Immunology, VABHS and assistant professor of ophthalmology, Harvard Medical School. Of course, patients with HIV suffer from common causes of vision loss—cataract, glaucoma, diabetes, macular degeneration, for instance—just like those without HIV infection. If there is no significant immunodeficiency, then the patient’s HIV status would be less relevant, and these more common causes of vision loss should be pursued. My first task would be to determine the patient’s most recent CD4 T-cell count.

Assuming an HIV-positive individual is experiencing visual symptoms related to his/her underlying HIV infection (especially in the setting of CD4 counts < 200 cells/mm3), ocular opportunistic infections (OOI) come to mind first. Despite a reduction in incidence of 75% to 80% in the HAART-era, CMV retinitis remains the most common OOI in patients with AIDS and carries the greatest risk of ocular morbidity.2 In fact, based on enrollment data for the Longitudinal Study of the Ocular Complications of AIDS (LSOCA), the prevalence of CMV retinitis among patients with AIDS is more than 20-fold higher than all other ocular complications of AIDS (OOIs and ocular neoplastic disease), including Kaposi sarcoma, lymphoma, herpes zoster ophthalmicus, ocular syphilis, ocular toxoplasma, necrotizing herpetic retinitis, cryptococcal choroiditis, and pneumocystis choroiditis.3 Beyond ocular opportunistic infections, the most common retinal finding in HIV-positive people is HIV retinopathy, nonspecific microvascular findings in the retina affecting nearly 70% of those with advanced HIV disease. Fortunately, HIV retinopathy is generally asymptomatic.4

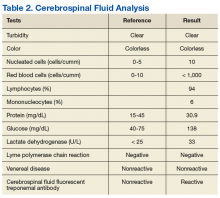

►Dr. Swamy. Thank you for those explanations. Based on Dr. Serrao’s differential, it is worth noting that this patient is MSM. He was evaluated in urgent care with the initial examination showing a temperature of 98.0° F, pulse 83 beats per minute, and blood pressure 110/70 mm Hg. The eye exam showed no injection with normal extraocular movements. Initial laboratory data were notable for a CD4 count of 730 cells/mm3 with fewer than 20 HIV viral copies/mL. Cytomegalovirus immunoglobulin G (IgG) was positive, and immunoglobulin M (IgM) was negative. A Lyme antibody was positive with negative IgM and IgG by Western blot. Additional tests can be seen in Tables 1 and 2. The patient has good immunologic and virologic control. How does this change your thinking about the case?

►Dr. Serrao. His CD4 count is well above 350, increasing the likelihood of a relatively uncomplicated course and treatment. Cytomegalovirus antibodies reflect prior infection. As CMV generally does not manifest with disease of any variety (including CMV retinitis) at this high CD4 count, one can presume he does not have CMV retinitis as a cause for his visual changes. CMV retinitis occurs mainly when substantial CD4 depletion has occurred (typically less than 50 cells/mm3). A positive Lyme antibody screen, not specific to Lyme, can be falsely positive in other treponema diseases (eg, Treponema pallidum, the etiologic organism of syphilis) as evidenced by negative confirmatory Western blot IgG and IgM. Antineutrophil cystoplasmic antibodies, lysozyme, angiotensin-converting enzyme, rapid plasma reagin (RPR), herpes simplex virus, toxoplasma are generally included in the workup for the differential of uveitis, retinitis, choroiditis, etc.

►Dr. Swamy. Based on the visual changes, the patient was referred for urgent ophthalmologic evaluation. Dr. Butler, when should a generalist consider urgent ophthalmology referral?

►Dr. Butler. In general, all patients with acute (and significant) vision loss should be referred immediately to an ophthalmologist. The challenge for the general practitioner is determining the true extent of the reported vision loss. If possible, some assessment of visual acuity should be obtained, testing each eye independently and with the correct glasses correction (ie, the patient’s distance glasses if the test object is 12 feet or more from the patient or their reading glasses if the test object is held inside arm’s length). If the general practitioner does not have access to an eye chart or near card, any assessment of vision with an appropriate description will be useful (eg, the patient can quickly count fingers at 15 feet in the unaffected eye, but the eye with reported vision loss cannot reliably count fingers outside of 2 feet). Additional ocular symptoms associated with the vision loss, such as pain, redness, photophobia, new flashes or floaters, increase the urgency of the referral. The threshold for referral for any ocular complaint is lower compared with that of the general population for those with evidence of immunodeficiency, such as for this patient with HIV. Any CD4 count < 200 cells/mm3 should raise the practitioner’s concern for an ocular opportunistic infection, with the greatest concern with CD4 counts < 50 cells/mm3.

►Dr. Swamy. The patient underwent further testing in the ophthalmology clinic. Dr. Butler, can you please interpret the funduscopic exam?

►Dr. Butler. Both eyes demonstrate findings (microaneurysms and small dot-blot hemorrhages) consistent with moderate nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (Figure 1A, white arrows). HIV-associated retinopathy could produce similar findings, but it is not generally seen with CD4 counts > 200 cells/mm3. Additionally, in the left eye, there is a diffuse patch of retinal whitening (retinitis) associated with the inferotemporal vascular arcades (Figure 1B, white arrows). The entire area involved is poorly circumscribed and the whitening is subtle in areas. Overlying some areas of deeper, ground-glass whitening there are scattered, punctate white spots (Figure 1B, green arrows). Wickremasinghe and colleagues described this pattern of retinitis and suggested that it had a high positive-predictive value in the diagnosis of ocular syphilis.5

►Dr. Swamy. The patient then underwent fluorescein angiography and optical coherence tomography (OCT). Dr. Butler, what did the fluorescein angiography show?

►Dr. Butler. The fluorescein angiogram in both eyes revealed leakage of dye consistent with diabetic retinopathy, with the right eye (OD) worse than the left (OS). Additionally, the areas of active retinitis in the left eye displayed gradual staining with leopard-spot changes, along with late leakage of fluorescein dye, indicating vasculopathy in the infected area (Figure 2, arrows). The patient also underwent OCT in the left eye (images not displayed) demonstrating vitreous cells (vitritis), patches of inner retinal thickening with hyperreflectivity, and hyperreflective nodules at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium with overlying photoreceptor disruption. These OCT findings are fairly stereotypic for syphilitic chorioretinitis.6

►Dr. Swamy. Based on the ophthalmic findings, a diagnosis of ocular syphilis was made. Dr. Serrao, what should internists consider as they evaluate and manage a patient with ocular syphilis?

►Dr. Serrao. Although isolated ocular involvement from syphilis is possible, the majority of patients (up to 85%) with HIV can present with concomitant central nervous system infection and about 30% present with symptomatic neurosyphilis (a typical late manifestation of this disease) that reflects the aggressiveness, accelerated course and propensity for wide dissemination of syphilis in this patient population.7

The presence of concomitant cutaneous rashes should prompt universal precautions, because transmission can occur via skin to skin contact. Clinicians should watch for the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction during treatment, a syndrome of fever, myalgias, and headache, which results from circulating cytokines produced because of rapidly dying spirochetes that could mimic a penicillin drug reaction, yet is treated supportively.

As syphilis is sexually acquired, clinicians should test for coexistent sexually transmitted infections, vaccinate for those that are preventable (eg, hepatitis B), notify sexual partners via assistance from local departments of public health, and assess for coexistent drug use and offer counseling in order to optimize risk reduction. Special attention should be paid to virologic control of HIV since some studies have shown an increase in the propensity for breakthrough HIV viremia while on effective ART.9 This should warrant counseling for ongoing optimal ART adherence and close monitoring in the follow-up visits with a provider specialized in the treatment of syphilis and HIV.

►Dr. Swamy. A lumbar puncture is performed with the results listed in Table 2. Dr. Serrao, is the CSF consistent with neurosyphilis? What would you do next?

►Dr. Serrao. The lumbar puncture is inflammatory with a lymphocytic predominance, consistent with active ocular/neurosyphilis. The CSF Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test is specific but not sensitive so a negative value does not rule out the presence of central nervous system infection.10 The CSF fluorescent treponemal antibody (CSF FTA-ABS) is sensitive but not specific. In this case, the ocular findings, positive serum RPR, CSF lymphocytic predominance, and CSF FTA ABS strongly supports the diagnosis of ocular/early neurosyphilis in a patient with HIV infection in whom early aggressive treatment is warranted to prevent rapid progression/potential loss of vision.11

►Dr. Swamy. Dr. Butler, how does syphilis behave in the eye as compared to other infectious or inflammatory diseases? Do visual symptoms respond well to treatment?

►Dr. Butler. As opposed to the dramatic reduction in rates and severity of CMV retinitis, HAART has had a negligible effect on ocular syphilis in the setting of HIV coinfection; in fact, rates of syphilis, including ocular syphilis, are currently surging world-wide, and HIV coinfection portends a worse prognosis.12 This is especially true among gay men. More so, there appears to be no correlation between CD4 count and incidence of developing ocular syphilis, as opposed to CMV retinitis, which occurs far more frequently in those with CD4 counts < 50 cells/mm3. In keeping with its epithet as one of the “Great Imitators,” syphilis can affect virtually every tissue of the eye—conjunctiva, sclera, cornea, iris, lens, vitreous, retina, choroid, optic nerve—unlike other OOI, such as CMV or toxoplasma, which generally hone to the retina. Nonetheless, various findings and patterns on clinical exam and ancillary testing, such as the more recently described punctate inner retinitis (as seen in our patient) and the more classic acute syphilitic posterior placoid chorioretinitis, carry high specificity for ocular syphilis.13

Patients with ocular syphilis should be treated according to neurosyphilis treatment protocols. In general, these patients respond very well to treatment with resolution of the ocular findings and recovery of complete, or nearly so, visual function, as long as an excessive delay between diagnosis and proper treatment does not occur.14

►Dr. Swamy. Following this testing, the patient completed 14 days of IV penicillin with resolution of symptoms. He had no further vision complaints. He was started on Triumeq (abacavir, dolutegravir, and lamivudine) with good adherence to therapy. Dr. Serrao, in 2016 the CDC released a clinical advisory about ocular syphilis. Can you tell us about why this is an important diagnosis to be aware of today?

►Dr. Serrao. As with any disease, the epidemiologic characteristics of an infection like syphilis allow the clinician to more carefully entertain such a diagnosis in any one individual by improving the index of suspicion for a particular disease. Awareness of an increase in ocular syphilis in HIV positive MSM allows for a more timely assessment and subsequent treatment with the goal of preventing loss of vision.15

1. Cunningham ET Jr, Margolis TP. Ocular manifestations of HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(4):236-244.

2. Holtzer CD, Jacobson MA, Hadley WK, et al. Decline in the rate of specific opportunistic infections at San Francisco General Hospital, 1994-1997. AIDS. 1998;12(14):1931-1933.

3. Gangaputra S, Drye L, Vaidya V, Thorne JE, Jabs DA, Lyon AT. Non-cytomegalovirus ocular opportunistic infections in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;155(2):206-212.e205.

4. Jabs DA, Van Natta ML, Holbrook JT, et al. Longitudinal study of the ocular complications of AIDS: 1. Ocular diagnoses at enrollment. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(4):780-786.

5. Wickremasinghe S, Ling C, Stawell R, Yeoh J, Hall A, Zamir E. Syphilitic punctate inner retinitis in immunocompetent gay men. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(6):1195-1200.

6. Burkholder BM, Leung TG, Ostheimer TA, Butler NJ, Thorne JE, Dunn JP. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography findings in acute syphilitic posterior placoid chorioretinitis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2014;4(1):2.

7. Musher DM, Hamill RJ, Baughn RE. Effect of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection on the course of syphilis and on the response to treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(11):872-881.

8. Lukehart SA, Hook EW 3rd, Baker-Zander SA, Collier AC, Critchlow CW, Handsfield HH. Invasion of the central nervous system by Treponema pallidum: implications for diagnosis and treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109(11):855-862.

9. Golden MR, Marra CM, Holmes KK. Update on syphilis: resurgence of an old problem. JAMA. 2003;290(11):1510-1514.

10. Marra CM, Tantalo LC, Maxwell CL, Ho EL, Sahi SK, Jones T. The rapid plasma reagin test cannot replace the venereal disease research laboratory test for neurosyphilis diagnosis. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39(6):453-457.

11. Harding AS, Ghanem KG. The performance of cerebrospinal fluid treponemal-specific antibody tests in neurosyphilis: a systematic review. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39(4):291-297.

12. Butler NJ, Thorne JE. Current status of HIV infection and ocular disease. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012;23(6):517-522.

13. Gass JD, Braunstein RA, Chenoweth RG. Acute syphilitic posterior placoid chorioretinitis. Ophthalmology. 1990;97(10):1288-1297.

14. Davis JL. Ocular syphilis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2014;25(6):513-518.

15. Clinical Advisory: Ocular Syphilis in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/clinicaladvisoryos2015.htm. Accessed September 11, 2017.

►Lakshmana Swamy, MD, chief medical resident, VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) and Boston Medical Center. Dr. Serrao, when you hear about vision changes in a patient with HIV, what differential diagnosis is generated? What epidemiologic or historical factors can help distinguish these entities?

►Richard Serrao, MD, Infectious Disease Service, VABHS and assistant professor of medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. The differential diagnoses for vision changes in a patient with HIV is based on the overall immunosuppression of the patient: the lower the patient’s CD4 count, the higher the number of etiologies.1 The portions of the visual pathway as well as the pattern of vision loss are useful in narrowing the differential. For example, monocular visual disturbances with dermatomal vesicles within the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve strongly implicates varicella zoster retinitis or keratitis; abducens nerve palsy could suggest granulomatous basilar meningitis from cryptococcosis. Likewise, ongoing fevers in an advanced AIDS patient with concomitant colitis, hepatitis, and pneumonitis is strongly suspicious for cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis with wide dissemination.